NEBRASKAland

special southlands issue

DECEMBER 1977 60 Cents

NEBRASKAland

"Tis the Season to be Jolly HOLIDAY SEASON is a special time of year, but every month is special if you subscribe to NEBRASKAIand Magazine. That's because every month you receive this gorgeous full-color magazine. Inside are beautiful color photos of Nebraska's wildlife, scenic places, people, outdoor recreation, plus historical yarns, how-to information, hunting and fishing stories and dozens of other features. As the holidays make us think of family and friends, think also of us. What better gift for those special people than subscriptions to NEBRASKAIand? Each issue will make that gift all the more memorable. And, in addition to the magagazine, subscribers receive the monthly newspaper of the Game and Parks Commission, keeping them updated on the outdoor scene. Order now. You'll be jolly that you did! Subscriptions just $5 per year; $9 two years; $12.50 three years. Send name, full address and proper amount for all subscriptions to. NEBRASKAIand, Nebraska Game and Parks Commission; Box 30370, Lincoln, NE 68503. Published by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission VOL 55 / NO. 12 / DECEMBER 1977 commission Chairman: Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District (402) 371-1473 Vice Chairman: William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District (308) 432-3755 2nd Vice Chairman: Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-central District (308) 452-3800 H.B. (Tod) Kuntzelman, North Platte Southwest District (308) 532-2982 Richard W. Nisley, Roca Southeast District (402) 782-6850 Robert G. Cunningham, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District (402) 553-5514 Shirley L Meckel, Burwell North-central District (308) 346-4015 Director: Eugene T. Mahoney Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, Jr. Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree staff Chief, Information & Education: W. Rex Amack Editor: Lowell Johnson Senior Editor: Jon Farrar Editorial Assistants: Ken Bouc, Bill McClurg Field Editors: Bob Grier, Faye Musil, Rocky Hoffmann, Butch Isom Art Director: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita StefkovichCopyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1977. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska

Contents FEATURES NEBRASKA'S HEARTLAND THE SOUTHLANDS AND ITS PEOPLE PRISONERS OF TIME 8 16 CANYON COUNTRY 18 WETLANDS . . . VICTIMS OF PROGRESS 24 A STREAM OF LIFE ... THE PLATTE 30 SOUTHLANDS AND WATER: RECIPE FOR FUN 36 SETTLEMENT AND GROWING PAINS 40 DEPARTMENTS TRADING POST 49 COVER: Regardless of backgrounds and beliefs, few things in America are as traditional as the Christmas season, and few holidays are more enjoyable. And, what can better represent the observance than a calm and scenic winter landscape. This tranquil view is part of Stuhr Museum at Grand Island. May the peaceful and beautiful mood of this setting pervade all human endeavors.Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAIand, P.O. Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Rates: 60 cents per copy; $5 per year; $9 for two years; $12.50 for three years.

DECEMBER 1977 3

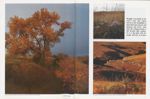

NEBRASKA'S HEARTLAND

The Nebraska Southlands is a region °f large irrigation and flood-control reservoirs. But, it's also an area of rainwater basins, and the meandering Platte and other rivers, and migratory bird oasis, and farming country. This is the fourth and final issue in this series depicting specific geographic regions of the state and their people, the wildlife, vegetation, a bit of history and other data. Come visit with us.

Roughly one-fourth of the state's area, this region known as the Southlands is farm land and canyons and plateaus and rivers. And, since the coming of man, it has become lake country. It is a big land with few people and lots of scenery

THE SOUTHLANDS AND ITS PEOPLE

by Faye Musil Throughout the ages, people have tried to alter the land. Often, they succeeded. But, usually the land changed them. It altered their faces, their posture, but more importantly it affected their philosophies as only the land, and time, can

THE FIRST TO COME and go in Nebraska probably did so quietly, perhaps a little desperately. There is no record of the first man on the plains, but it is said among the Cheyenne that their ancestors, fleeing now-forgotten enemies, crossed salt water in the frozen regions far to the north before reaching the plains.

Archaeological evidence points to the existence of prehistoric cultures in community with such early creatures as the mammoth, mastodon, sabertoothed cat, and a buffalo with seven or eight-foot horn spread. Vegetation was lush then, and the huge creatures thrived. Man, making fine, fluted points now known as Folsom, existed with them.

These men learned to live along streams like the Lime and Medicine creeks in Frontier County; streams that have probably existed since the first glaciers.

A long drought then struck the plains, drying up lakes and streams and killing the vegetation that the great creatures needed to survive, and the Folsom and another, Yuma, peoples disappeared. A new kind of animal took their places. These new creatures were attuned or adapted to the different conditions, and seasonal changes thus formed their life patterns. Each year these animals climbed up and down a ladder of streams across the plains as they fled from winter and followed spring.

Great masses of ducks and geese and cranes that once crossed the Platte and Republican still stop to rest and feed along the rivers. Their numbers are greatly reduced from the times when they came in great clouds that darkened the sky, however.

Vast herds of shaggy buffalo, too, ambled back and forth, following grass, while other animals adapted their bodies in order to stay home and survive the icy winds of Nebraska winters.

Sometime between 400 and 600 A.D., a Woodland culture found Nebraska to its liking. Still hunters, they may have cultivated some crops. By about 1200, though, they too had disappeared or merged into an Upper Republican people who spread in large, earthen villages from the Republican Valley to Loup country.

These people were apparently more dependent on agriculture than their predecessors, and as new influences and new people pushed up from the south they developed more artistic abilities, forming high-grade pottery, and stone, bone, horn and shell ornaments.

Hunting skills developed into community skills, and entire villages would be involved in "collecting" the winter meat. Without the white man's horses, the solitary Indian could perhaps kill a lagging buffalo bull, or a cow heavy with calf, but he couldn't provide the large amounts of meat needed to feed his family through the

winter. So, cooperative hunts were organized, driving

whole herds over convenient bluffs.

winter. So, cooperative hunts were organized, driving

whole herds over convenient bluffs.

No one knows for sure what happened to the Upper Republican people. Some believe they were the ancestors of the historic Pawnee. Their villages have been found under a heavy mantle of dust almost devoid of pollen. Perhaps the silent land betrayed them in a second long drought that reduced them to mere subsistence, as it was to betray the white man centuries later.

Perhaps it was the Upper Republicans who built the prehistoric sump ditch in evidence near Cozad, stretching from the creek waters of the Loup River to the Platte Valley. Perhaps desperation prompted the gigantic undertaking to bring precious water to drying fields in the rich soil of the Platte. No one really knows the origins of the ditch.

When time again brought rain, it also brought the Pawnee Indian with his corn and his pottery. The Pawnee, also centered in the Republican, Loup and Platte Valleys, cultivated corn and squeezed two buffalo hunts a year between planting and hoeing and harvesting.

Then came the white man, and as the dust settled from his trampings across Nebraska, he found the state to his liking, and many of them settled in the Southlands. He found, though, that the land could betray him in the form of hordes of crop-eating grasshoppers, or more persistent drought.

Willa Cather, growing up in the south-central community of Red Cloud, gathered impressions of the hardy, compassionate, often lonely people who struggled with the land, and wrote about them—their laughter and their tears, their triumphs and their mistakes. Many of the places she visited in her youth are preserved as landmarks now in the area known as Catherland.

George Norris, too, grew up in Nebraska, and McCook still pulses somehow with the results of his presence. He decided that something could be done about the uncertainties of Nebraska rain. With the Tennessee Valley Authority

From his and other efforts, Enders, Swanson, Red Willow and Medicine Creek reservoirs, irrigation and flood-control impoundments, have changed the character of the land surrounding them, as does giant Lake McConaughy on the North Platte River, and Harlan County Reservoir on the Republican.

Today, sufficient water for crops is assured to much of the region. Farmers and ranchers mix peaceably now without the bloodshed familiar to the range wars. Industry has even managed to mix with agri-business. For numerous reasons, man continues to change the land. Perhaps we're going too far. There are center pivot systems and land-leveling projects, pastures turning into wheat ground, and shelterbelts being bulldozed out. Skeptics dread the water table dropping and even the tenacious prairie vegetation dying. With the shelterbelts all gone, could the land begin to blow again?

There are those who ask such questions and those who stifle all concern in their eagerness for "progress." So people argue about it. Will the pheasants all be gone f without fencerows and shelterbelts? Argument seems at home in the Southlands. There is a silent strength to the people of this big country, a character that sometimes breeds argument—even downright battle.

Yet, many little towns still provide benches along the store fronts on main street. Those benches are gathering and profering places for some of the best "backwoods" wisdom in the country.

Maybe it has something to do with farming and ranching. Out there on the land, a man has the chance to express his own individuality, his tastes and prejudices. If he doesn't like sunflowers, he can try to cut them all down. If he likes to hear bobwhite quail in the morning, well, he just might leave the old shelterbelt and the tangle of bushes next to it.

No other occupation offers more opportunities for a person to express himself. Everything he does is likely to be an extension of his philosophy—even the land itself seems an extension of self.

The little towns, too, have character of their own. Some are thriving—progressive and growing.

The Southlands is full of little towns, most of them along some river or stream.

It's generally a friendly, rural-oriented people youll find there. It's also generally an honest people. They're willing to call a spade a spade, and to dig with it if occasion arises. If they disagree with your considered opinion, they're likely to say so.

If you've got the time, though, they're likely to spend some of it telling you about the land and the towns and the folks down the road. And it's likely to be all true. Of course, a few of those Southlanders have been known to spin their tales as they go along, just to see if you can keep your own counsel, but they are not from meanness, you see. All in fun.

PRISONERS OF TIME

by Faye Musil Just a heartbeat ago, man came to the Southlands and demanded a part in the drama formed by millions of years and elemental upheavalSOMEWHERE, SOMETIME in the mists and star clusters in this old universe, a new solar system appeared, and the dusts of that solar system gradually evolved into planets—including one called Earth.

Hurtling through time and space, Earth became a tiny stage for a play called Eife, and through the millions of years of its existence, Earth has seen the comings and goings of billions of actors of many shapes, sizes and forms.

Looking at southwestern Nebraska, it's nearly impossible to relate the farms and factories and oil wells now, to the shapeless, bubbling mass that may once have been its surface. The time of empty, lifeless formation of life seems inconceivable.

No record exists of the first living thing-probably a single cell, but scientists estimate that at least 4,400 milion years passed before that single-celled organism developed into the first known fossilized life—the trilobite.

Under all the modern-day soils and plants and animals, under ancient sediments formed during millions of years, lies a layer of granite; a silent mass that hides the record of life's beginning.

Sometime during the storms of earth's past came rains, the violent combination and recombination of elements that resulted in water. And, water figured most importantly in the formation of Nebraska's Southlands, for it covered the area throughout nearly 600 million years. Layer after layer of sediment was deposited at the bottom of this sea, a sea of varying depth and shoreline.

As land masses were thrust above the seas, impurities washed into the waters, forming layers of shales and sandstone, gypsum and anhydrite between layers of more pure limestone. Trapped in those layers of sediment are the fossils of ancient marine life, which were gradually evolving into more and more complex forms from trilobite to corals, to "sea monsters" of gigantic size and appetite. There were huge marine lizards, plesiosaurs (like the Loch Ness Monster is reputed to be), huge sharks, abundant fishes of all kinds including one much like the Elorida tarpon.

And while these sea creatures were evolving, the variety of individual plants and animals were dying and decaying and combining with minerals to become part of the sediments on the ocean floor. Among these sediments are the oil and gas so vital to today's economy. The sight of donkey pumps, which help to tap these mineral resources, is not uncommon to the Southlands.

Finally, the lifting and shuffling of land masses resulted in drainage of the inland sea to form what was to become the continent's Great Plains.

With the sea drained, layers of sediment continued to build throughout the Southlands. Those layers were deposited by streams that drained through the region, by winds, and by the spewing out of volcanic ash from the violent upheavals to the west.

Mammals were beginning to show up by then. During that dryland period before the Ice Age, mammal species were appearing and disappearing. Pig-like oreodonts, many kinds of camels, horses, and rhinos came and went. What was to become the Plains was teeming with life.

Tremendous climatic upheaval led to disruptions in plant and animal life as organisms evolved to take advantage of certain conditions, then disappeared as those conditions changed. Hundreds of species marched from 16 NEBRASKAIand

And, at last, came the Ice Age. As the glaciers ground in from the north, across eastern Nebraska, the climate continued to change also in the country farther to the west. Apparently, there were periods of cold, dry weather that supported the plants and animals characteristic of the age. There may have been tundra-like vegetation in the Southlands during that period. There were certainly large, "big-game" mammals. And, that was the opening scene for man, who then entered the drama. He was supplied with big game in the form of mastodons, mammoths, and huge bison with 7 to 8-foot horn spreads.

There were also plenty of competing predators like the predecessors of modern-day wolves and coyotes, maybe a few sabre-toothed cats, and a North American lion was probably somewhat larger than the modern African lion-and more adapted for running.

Animals seem to have been bigger then than their progeny of recent times. Bison and wolves have become much smaller throughout the ages. Sabre-toothed cats have disappeared altogether.

But, man came on the scene with an abundance of game only if he could invent the tools to help him take advantage of the huge meat animals that could supply his wants.

Even after man's arrival, the uncertainties of climate continued to plague the many species of plants and animals that alternately established themselves in the region, then disappeared. There were surely periods of drought when the soils of the region were arranged and rearranged by shifting winds, and plant and animal life all but disappeared.

There also seem to have been periods of plenty when water was abundant and so were plants and animals. Perhaps during the Ice Age, maybe between advances of the glaciers, maybe during the presence of great sheets of ice in eastern Nebraska, there were many more trees in the region than modern white man saw when he reached the Plains. Perhaps there were extensive forests of conifers spread throughout the territory.

Fossil evidence along the stream courses indicates the presence not only of grazing animals, but also of browsers—the ancestors of modern deer, for example. There must have been trees and shrubs along with the grasses to support their existence.

As the ice receded for the final time, it left behind a rich plant and animal life which has continued to evolve in modern times. When the white man reached the plains, a mere heartbeat ago in geologic time, he found a rich array of mixed-grass prairie and the many animals it supported. The most spectacular of these was probably the buffalo (Bison bison). Without its ancestors to compare it with, white man found the buffalo an impressive animal—and to the Indian it was indeed a fountain of life.

Throughout his occupancy, man has tried to change the face of the land to suit his purposes. Yet all his changes taken together are only puny efforts when compared to the violence and extent of change wrought by natural forces at work over the billions of years of the earth's past. Man, like all other life forms before him, is still, after all, but another feature of the natural world, and he, too, will pass.

DECEMBER 1977 17

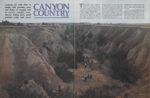

CANYON COUNTRY

by Faye Musil Canyons are trail rides in spring with greening grass and hopes of enough rain to survive another year. Horses belong here, amid gnarled cedar and yuccaTHESE HILLS, these wonderful, beautiful hills. They've been my love as a child loves a mother who teaches peace and serenity and courage and acceptance. I feel a poignancy of isolation leaving them.

These rugged canyons; IVe seen them in the gentleness of morning mist when the cedars that nestle in their fingers and palms are caressed with early morning glow. IVe seen them in the blaze of sunset when they are gilded bronze, shadows deepening into mysterious blue and purple. I've seen them in blistering summer heat when even breathing seems a struggle. And in winter when a thin crust of snow blazes and glistens, and wind whips scrub cedars into grotesqueries of twisted survival wherever they venture above the canyon rim.

There is the moment of silent isolation, gazing at a tumbleweed pinioned on barbed wire; a lonely, static corpse that has been rolled and tossed with the wind.

There is the joyous surprise of a tiny

yellow flower, wonderful in its mere

existence on the seemingly monotonous tableland. And in the protection

of the canyon, often perching just below the rim, the tangle of white

chokecherry plumes and tiny yellow

There is the majesty of topping a rise and looking miles across a valley at the rough slope on the other side, softened by a blue mist. There is the immensity of sky and the threat of a coming storm building on the horizon many miles away, silently coming closer and filling that sky.

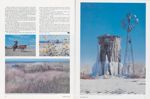

And windmills; distant and near windmills, tall and short windmills, even dead windmills—skeletons of someone's hopeful quest for water, and the need then forgotten.

Here and there, in the protection of a canyon pocket, are the ruins of a house, a place where children may have lived and grown and learned the hardship of living.

I know somewhere along the Medicine in Frontier County are the remains of cave dwellings of the Folsom people; people who lived and disappeared without leaving any written record of their laughter and tears or their dreams-if they ever laughed and cried and dreamed—or of their fears, perhaps, of the saber-toothed cat and the woolly mammoth that trod the canyons with them.

I know that the Republican River Valley was a vast cradle for the plains Pawnee who cultivated crops and hunted buffalo twice a year, and loved and died, leaving only bits of their lives behind for those of us who came later to cherish before we, too, die, leaving different, but still only bits of our stories for others to wonder about.

There were the true tall tales of men like Wild Bill and Buffalo Bill who cavorted in this country, hunting buffalo and sometimes men. And later the great showman Buffalo Bill, who created a show of shows for his guest the Duke; a show complete with wild Indians and buffalo.

I have walked the canyon rims with regret that I cannot see the great grazing herds of buffalo; regret that I cannot smell the smoke rising from the peaceful earthen lodges of the Pawnee; that I cannot hear the chatter of their children; that I cannot taste the waters of the Red Willow when they flowed clear and cool.

Where there were buffalo and elk, now mule deer and prairie dogs and badgers and rattlesnakes remain. There is the red-tailed hawk, scanning the grassland for food, and the turkey vulture riding the thermals.

22

The canyons are a kind of music; a melody that recurs time after time; a reminder of forgotten friends; a quiet moment; times past but not dead

And there is the grass, perennial as tomorrow, a promise of life even if man deserts the canyons and forgets the wonder of their spring green and summer khaki; the pleasant, sometimes ruthless texture of the hills.

Even here man has made his mark; a mark signifying grandiose plans. When he stopped dreaming that rain would follow his plowing and planting, he dreamed of harnessing the springtime torrent of water that rushed out of the mountains, that thundered out of the clouds in rare but awesome deluges. And he built dams from canyon wall to canyon wall and shaped the character of the land if only a little.

He backed up the water for miles and miles, forming lakes that would give life to his fragile crops that are, after all, not as thrifty as the prairie. And, he made the land bear fruit of a new kind, and seeks ever better crops.

Those lakes, though, are shaped by the wild land that cradles them. They twist and bend into fingers of canyons; they fork even as the canyons fork and divide; they shimmer in the midst of rocky rises, made by the rivulets that carried the little run-off that flowed. For in the days before the farmer and the dams, very little precious rain escaped the grass and flowers, which held it and stored it for more desperate times.

Man brought his cows with him to fatten on the grasses of the plateaus and shelter in the canyons. And, he thinks the land is his.

Mine has been the mingled pain and joy of concern. What of the center pivot systems on the tables? Will they pillage the silent reservoirs of water beneath them? What will happen as the sod is torn to make level spaces for them? Will the land blow away, destroying the beautiful, natural balance of prairie and wildflowers, of sheer canyon walls and cedars?

But, mostly, I've looked and listened to the canyons. Tve waded in the Medicine and imagined the lives of people 50 and 100 years ago at Champion where the mill, once the center of a small, isolated community, still stands beside the Frenchman.

And, it's been a music in my life. The kind of melody that recurs years later—like a tune that brings a silent, joyous melancholy.

Is the canyon country really like that? Only if you can gaze at it with your mind and hear it with your soul, without fear of something that is bigger than yourself.

23

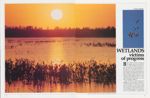

WETLANDS

victims of progress by Rocky HoffmannBACK WHEN TRAINS scheduled no regular stops, but would roll to a halt wherever and whenever any patron of the rail desired to get off, the old smoke-belching locomotives out of Kansas City, St. Jo and Omaha could be found pulled up near Grafton. The attraction there was the smartweed marsh country of Nebraska, a fairly popular retreat for the venturesome outdoorsman in a time when one didn't have to go very far to leave civilization behind.

Only the time of year dictated the

luggage of the transient recreationists. During the late spring and warm

summer months, it was more likely

they would be packing fishing poles

and frying pans, but as the days shortened and skies grayed, you could be

sure of encountering a ruddy-faced,

25

Trains no longer ramble across the countryside dropping passengers off at will. Economics have brought about a drastic change to the basins; a country in the heart of modern agriculture where corn now grows where muskrats and teal once swam. The rainwater basin region, once capable of producing rafts of ducks and providing hunting opportunities to many thousands, has lost a considerable portion of it's former values. Approximately 82 percent of the original 3,907 wetlands that saturated 17 south-central counties have been destroyed. Most of the remaining 695 basins have been adversely affected by ditch and tile drains, leveling, concentration dugouts and siltation.

Bounded irregularly on the east by Butler, Seward and Saline counties, and on the west by Gosper County, the terrain of the basin marshland is depressingly flat to the casual observer. Low spots, like sink basins, peen the surface of this land collecting rainwater, snow melt and irrigation run-off, filling the depressions in good years to an absolute level. Perched on a clay hardpan, the water remains, as the basin floors are nearly impervious to seepage. Gradual siltation provided root support for bulrush, spike rush, smartweed and cattails.

Though mostly ankle deep to a frog-catching youngster, the basins once stilled fairly deep pools. In the days of the natural prairie, buffalo would wallow in the cooling mud for salvation from the heat and flies. So numerous were the bison that the effect of each animal, fur encrusted with basin gumbo when leaving the wetlands, acted like a dredge, deepening the marshes. Their wallow would have secondary affects on the churned and loosened mud. When a dry year followed, the well-tilled marsh bottom would blow deep from the winds.

Siltation buildup in areas of good grass in the early prairie days was a slow and almost negligible process. Then the plow and horse broke the prairie sod and the dust bowl of the 1930's followed, depositing windblown soil in buffalo-dredged marshes, shallowing the basins to what they are today.

Hastings silt loam is the basic soil composition of these loess plains, making the land ideally suited for agriculture. 26 Deeply deposited, erosion has not yet reached a different, less productive soil composition. Leveling the high knobs into drained basins has expanded agricultural wealth, but has created a wetlands poverty-a life's need to migrant and resident waterfowl. The popular view that a natural marsh constitutes some horrible swamp hazard, and therefore is a menace to humans, helped place the marsh in low regard.

The majority of the remaining wetlands remain in private ownership with only 7,583 acres of natural rainwater marshes belonging to the public under state or federal wildlife agencies. Sacramento and its satellites in Phelps and Harlan counties, make up all but 80 acres of the Game and Parks-managed wet basins and associated

During wet years, basins provide excellent production of primarily bluewing teal and mallards, while shovelers, pintails, redheads, greenwing teal, and ruddies are occasional housekeepers. But the gold that glitters in the south-central rainwater marshes is not the production input on the Central Flyway's waterfowl populations. Primarily it's the staging capability the area holds for ducks and geese enroute to the production grounds of the prairie pothole country of the Dakotas and Saskatchewan.

Each spring the wet basins host millions of waterfowl on their northerly migrational paths; natural seed grains of smartweed and pig weed, coupled with corn and milo from adjoining croplands, add layers of fat for the next leg of their journey and the hardships of parenthood soon to be encountered. Mates are often selected in the rain basins, prior to wildlife's most critical life phase. An abundance of territory is essential or the hardships are too severe. Crowding can be devastating, stressing migrating waterfowl.

Watch as an all-terrain vehicle breaks the pliable spring ice of Funk Lagoon, for instance; mud rolls over the rubber tracks, hydrogen sulfide gas fills the air, and another pile of dead white-fronted geese is dumped off the trackster to be burned. Waterfowl can't spread out; there's no place to go. Just a few infected birds, when crowded, and an avian cholera epidemic grips the migration. What has happened to the basins? Can man find no better treatment for land and birds and marsh than to destrov them? Can't we try to get along with nature, rather than tamper? A marsh is a marvelous place, and the more natural, the better. They must be retained.

29

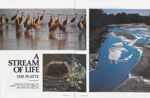

A STREAM OF LIFE

THE PLATTE

by Rocky Hoffmann A migration route long before the pioneers, river hosts many millions of birds bound for nesting sites

Silently at first, then in a great roar they come to the valley, like countless grains of sand

THEY COME IN THE SPRING by the millions; keenly scanning the plains from aloft in search of the ribbons of water flowing silently around wiliowed islands and sandbars. As silent as the river, they come from as far as South America to rest, to court, to pass on again, renewed with life from the blood of the Platte. They will soon continue their northerly travels. Some will venture as far as northern Siberia.

Their sustained silence, however, is lost to clamour as they approach the valley from the south. Excitement pre vails, and at times, their combined furor is nearly deafening, as more and more pour into the Platte Valley from a seemingly inexhaustible source. By late March, more waterfowl will be along the big bend area of the Platte River than can be found at any one time anywhere else in the Central Fly way.

It has been accurately described as an hourglass migration, with the Platte being the constricted portion through which all migrators, like grains of sand, must pass before spreading out once again in the north.

The river is alive with activity . . . confusion prevails. Some fowl have arrived on the river for the first time; for others it is a familiar, semi-annual haunt. It is not just the Platte that more than 1,000,000 ducks and geese, and at times up to 99% of the world's migratory sandhill crane population, seek each spring, but also the adjoining sub-irrigated wet meadows and croplands.

White-fronted geese, Canadas, and a few snows intermix, yet remain markedly separate in fields of last year's missed grain. Mallards and pintails are among the geese greedily bidding for golden kernels, yet cautiously avoiding the long necks of the Canadas that sometimes viciously lash out to protect scratched-up grain.

Like a variety store, the Platte shelves the inventory of spring's wildlife. Wigeon, gadwall, shoveler, mallard, pintail, teal, merganser ... no longer drab in winter's plumage, but now almost gaudy with color to attract their own and intimidate the rest.

Like refracted light from fuel spilled on the water's surface, a veritable prism of colored feathers swims from behind an abandoned beaver lodge. The wood duck, once nearly extinct, is becoming a common visitor and nester along the Platte; a barometer of change that signals a more riparian habitat than that seen by the buffalo ... in fact, one generation of man has easily noticed that change.

From Lexington to North Platte, cottonwoods have encroached upon and in some instances engulfed the valley of the Platte. With the trees came the mammals more common to the Missouri and eastern forests. White-tailed deer, once as scarce as the wood duck in this region, now browse in numbers beneath the vines and limbs of the river habitat.

Beavers have gnawed deeply into

the older trees, and have severed

sapplings, carrying away fresh twigs for

winter's food bank, when ice will incarcerate them in their lodge, and a

brittle freeze will separate them from

DECEMBER 1977

33

Raccoon and 'possum prowl by night disrupting life to sustain their own. Coyotes and possibly a few bobcats find sanctum among the trees.

The earth is sand, spilled from the hills to the north and carried by river to the east. Cottonwood leaves pile upon the sand, fall after fall. Fluorescent leaves wither and rot, and the sand turns black. In the spring, after the waterfowl pass on, morels break through like dry-land coral reefs. Most go unnoticed and dry like the earth. Others fill grocery bags, to be simmered in butter or to garnish steaks. The tops of many are nipped away. What creatures of the Platte do this?

It must be the spring doe. Her tracks are everywhere along the river, and a squirrel chatters overhead. He enjoys the farmer's grain, but in the spring, ears of golden harvest are not as readily available. Nearby a destroyed turkey nest is scattered among the leaves . . . eggs broken and licked clean of their protein. Could it be that the same creature was responsible?

As summer's heat becomes more apparent, the river is quiet. The hords have left for the north leaving behind the obnoxious buzz of deer flies and a sweltering humidity. The wood ducks have stayed, but their presence goes unnoticed for this is nature's time for seclusion, set aside for the production of young.

A summer blizzard of cotton hits the Platte, projected from hundred-foot trees. The river is calmer now, the currents slow and sometimes stop. Crops are now depending on the Platte, and the river's bed blows while it's water runs between corn rows miles from the channel.

The river is best looking in the fall. Even the long, narrow leaves of the willow turn red. The brown cigar- shaped cattails have exploded like torn pillows, their gaping ruptures spread faded fuzz among the willows. The nights are cool now.

Some waterfowl have begun to return in family groups. They have replenished their numbers. There are many times more, but there appears to be fewer because it is only in the spring that so many gather at once along the Platte. Bald eagles, like hooded coroners of the wild, perch on leafless trees, ignoring the strong and waiting for the weak to falter. Sandhill cranes give the river a passing chortle.

Slush ice will soon begin to choke the river. The raccoon will be found denned-up more often as temperatures dip below zero, and the winds drive snow from the north, quilting the sides of everything with white lace.

In late February, a blizzard rages mercilessly for the second straight day. Heavy snow blasts skyward with each gust of wind. The Platte is totally obscured as the storm torments the night. Sometime before dawn the winds relent, and a brilliant eastern glow signals clear skies. Like phantoms of the storm, gray sillouettes stand motionless on an ice-encrusted sandbar. Without vision, a scouting group of sandhill cranes has come to the pinch of the hourglass. The Platte will soon come alive.

34 NEBRASKAIandWith the millions come a few, like whoopers; seeking a river that may be lost

HERE FLOWS THE LIFE BLOOD of the Southlands for both man and animal, and thus the inevitable conflict . . . man against nature, man against beast, and finally, man against man, to conquer and control the daily passage of water from the thaw in the Rocky Mountains to the Platte's uneventful merger with the Missouri.

The Platte's ecosystem is rugged, unlike the delicate ecosystem of the altitudinous mountain tundra from which its headwaters are formed. For man, the river has provided a freightway for furs, a guide to the gold mines, a trail for the Mormons, sand for Interstate 80, water for crops and cattle, force for electricity, scenery for river homes, recreation for the hard working multitudes, and life itself for those who depend on its presence.

In the past, the Platte was characterized by the lack of traditional river habitat ... it was a true prairie river with broad, open stretches of shallow water, exposed and scoured sandbars and bounded on both sides by sub-irrigated wet meadows. Water levels, governed only by rainfall and snow melt, swept clean the islands of sand, discouraging and removing heavy woody cover. Thus a Utopia was created for migrating wildfowl, providing a place to rest and mate for millions of ducks, geese, cranes and shorebirds. The stop-over along many miles of the Platte is not simply a convenience, but a life necessity in the scheme of species reproduction.

With the millions come the few— the whooping crane; desperately grasping for a renewed foothold in the natural world. Survival of the remaining few is day to day, with an absolute dependency on even the smallest detail of their life requirements. The river plays an equally important role to more than 90% of the world's migratory sandhill crane population, and three-fourths of the midcontinent population of white-fronted geese. The Utopia has been damaged by lack of knowledge. High waters come less often, as man instead of melt governs the river's flow. The hourglass pattern of waterfowl migration is ever narrowing, restricted by the encroachment of man and his developments to an ever shorter stretch of open sandbars. The threat of drastically diminishing the Central Flyway's waterfowl population through unwise management of the Platte is very real. And, those management decisions are made by a very few, directly benefitting, persons.

How important is the spring cry of the wild goose to the Saskatchewan farmer, as he shuts down the pounding noise of his tractor's engine to gaze skyward and listen for the assurance that winter has passed, or to the Oklahoma school boy, tardy because he sat under a lone tree to watch and listen to their passage, or to the masses in the big city when late at night the daily clatter of activity yields to the night fliers who voice their awareness of the lights below? The Platte provides this spring spectacle for those willing to listen and watch and understand, and to wait and hope for its recurrence in springs to come.

DECEMBER 1977 35

SOUTHLANDS AND WATER: Recipe for Fun

by Rocky HoffmannATER MAKES THE difference for recreation whether it's for hunting, fishing, camping, boating, or simply lying back and listening to le waves of a lake or the swirling eddy of a river, and if there's one thing Nebraska's Southlands is not short on, it's water.

Swanson, Enders, Red Willow, Medicine Creek, and Harlan County reservoirs provide 24,000 surface acres of water near the state's southern border.

More than 9,000 more acres are impounded in the Tri-County Reservoirs of Lake Ogallala, Sutherland, Maloney, Jeffrey Canyon, Johnson, Elwood and others. Sherman Reservoir reaches into the central portion of the state and provides 3,000 surface acres of enjoyment in the Loup City area.

Small lakes like Rock Creek, Wellfleet, Arnold, Ravenna, and Hayes Center provide another 200 acres.

Nearly 250 miles of Platte River swing through the southlands, forming the famous "big bend." The Republican, South Loup, Loup, Frenchman, Calamus, Cedar, and Little Blue rivers combine for an extra 800 river miles.

Tri-County canals, linking a system of reservoirs for power and irrigation, represent about 200 miles of diverted Platte River water.

The rain basin in the extreme south-central counties puddles up 32,529 acres of run-off water and wetlands in a good year for wildlife and people who enjoy it.

In all, nearly 70,000 surface acres of water and 1,250 miles of rivers and canals are at man's disposal to satisfy his quest for rest and relaxation. Rivers have always attracted man. They have provided for his survival and they have provided his recreation. Rivers can be calm and peaceful or wild and thunderous. Riverbottoms always seem 10 degrees colder than anywhere else to the waterfowler even though he depends totally on his curly coated retriever to fetch fat drakes from the ice-choked current. And, rivers always seem 10 degrees hotter to the fly-swatting catfisherman making his way through the entanglement of wild grape, poison ivy and dogwood. Oftentimes, the waterfowler and catfisherman are the same person, and becoming addicted to the river knows no seasons. Despite minor hardship, once it takes hold of you, you'll return again and again ... a river rat for life. (continued on page 43)

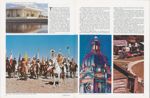

Settlement and Growing Pains

After centuries of relative tranquility, influx of whites was tumultuous, steadily bringing region to boil. Gradually, agriculture replaced unrest 40 NEBRASKAIand by Faye MusilWHEN CORONADO visited the central plains in 1541, seeking the Seven Cities of Gold, he was singularly unimpressed with the earthen dwellings he found in the Republican Valley. Yet the people he found were rich in the way of the plains, quietly growing crops and hunting buffalo to keep their population well-fed and healthy.

But the white man left behind the beginnings of an entire culture's degeneration, with his big-dogs, or horses, his diseases, his material goods, and his desire for more goods.

Like migrating waterfowl, a handful of Spanish expeditions climbed northward on the "ladder of streams" that crosses the plains, to extend Spanish influence in the New World.

The French, on the other hand, made their comings and goings along the rivers. In small groups, or even singly, they came quietly to trap, to trade, and to marry into Indian tribes.

The Spanish, jealous and suspicious of what they considered Trench encroachment, sent out an expedition in 1720. Villasur, with some 45 soldiers, a number of settlers, traders and a priest, reached the Platte in August, either at the forks or the mouth of the Loup. Stories of his confrontation with the Pawnee are confused, but only 13 of the original party returned to Santa Fe to tell about it.

Still, it wasn't until the great white migrations of the 1800's that the Indian was really hard-pressed. As late as 1835, a population of some 5,000 Grand Pawnee was estimated in one village along the Republican.

The trappers and gold-seekers were followed, however, by a motley crew of other whites using the Platte Valley as a corridor.

Following a lust for land, for gold, and for adventure, thousands of people crossed the continent by way of the Platte River Valley. They left many of their number dead along the road, victims of cholera, bad river crossings, stress, battles and firearm accident. They also left many of their treasured belongings, as the loads often proved too heavy.

While gold seekers and land seekers stampeded across the plains south of the Platte on the California and Oregon Trails, many weary Mormons plodded the river's north bank, pushing hand carts—the only conveyances available to them—seeking a place where they could live in peace.

The Pawnee were already near the end of their rope as a people. The whites had changed their life-style, bringing the horse and firearms and the easy accessibility to meat that went with them. Yet, the Sioux had taken over the hunting grounds, keeping the Pawnee out.

Time brought freight lines like Russell, Majors and Waddeli, and stagecoach lines, and the Pony Express, and names like Buffalo Bill Cody, Wild Bill Hickok, and Calamity jane. Along the Platte today, just off modern 1-80, are forts Kearny and McPherson, and Cody's ranch at North Platte. It is but an hour north to Fort Hartsuff near the Loup.

Fort Kearny was established in 1848 to protect settlers from Indians, although the Indians at that time were generally keeping the peace. Initially, Fort Kearny served as a station where wagon trains stopped for a day or two to rest, repair wagons, and secure additional supplies if any were available. The post wasn't always that peaceful, however, and as the Indian Wars followed the Civil War, troops from Fort Kearny were mobilized to protect freighting trains and stagecoaches.

just south and east of present-day North Platte, at the rim of a high plateau, is Sioux Lookout, a promontory from which the nomadic Sioux could observe straggling lines of adventurers that diverted their buffalo and halved their hunting grounds.

Yankee success at Gettysburg took some pressure off the Union, and in 1863, fearing a Confederate-organized Indian uprising, eight companies of Union Cavalry rode onto the plains. Stationed at Cottonwood Springs, just under Sioux Lookout, the soldiers were expected to cut off a major north-south Indian crossing. The post at Cottonwood Springs was later named Fort McPherson, and is now a national cemetery. Further fortified by galvanized Yankees, forts Kearny and McPherson withstood the first of many uprisings that were part of the Indians' final effort to drive the white man out of their hunting lands.

On August 7, 1864, the Indian had had enough. Sioux and Cheyenne warriors struck from Julesburg along the length of the Platte, and even down into the valley of the Little Blue. All along the way they picked up guns, ammunition, horses, mules, coffee, sugar, and sometimes a little whiskey. The Kansas-Nebraska frontier was thrown into a panic, and the few troops along the trail mostly shut themselves up in the forts. No one dared move without a large force riding on all sides.

Many versions are told of the January 1865 prairie fire, the greatest in all plains history. General Mitchell, hoping to stop the southern warriors in their northward march to join the fighting Sioux, organized a fire-setting crew from Fort Kearny along the Platte, deep into Colorado. That fire swept through southwest Nebraska, west Kansas and eastern Colorado before it died. The Indians were already | far north when the fire started.

It was in 1865, too, that a train was wrecked at Plum Creek ... present-day 5 Lexington. With rawhide ropes, the Cheyennes pulled out a culvert, then watched as the train hurtled out over empty space and crashed into the hole. The Indians then attacked, leaving five men on the ground, and broke into boxes of groceries and dry goods.

With the railroad and the telegraph | came even further indignities for the watching Indian, as buffalo slaughter was intensified. Eastern "gentlemen" and even foreign nobility like Duke Alexis of Russia came to kill the life-giving buffalo for sport, with cattleman, Indian scout and showman Buf- falo Bill Cody as guide. Tens of thousands of rotting carcasses lay on the plains—some with only the tongue utilized.

Warfare between Indian and white continued throughout the 1860's and 70s, and an 1873 skirmish at Sioux Creek in Loup County resulted in establishment of Fort Hartsuff the following year. Built to protect friendly Pawnee as much as settlers, Hartsuff was abandoned in 1881 with the Loup | Valleys largely settled, the Pawnee | moved to Indian Territory, and the power of the Sioux broken. With the Indian and the buffalo | gone, the plains were open to white settlement, and as the Indian was pushed farther and farther west and north, more settlers came to replace him. (Continued on page 50)

DECEMBER 1977 41

The South Platte area is a beautiful, peaceful, unspoiled family vacationland. We invite you to talk with us and meet our families as you pass through our towns. Visit our historical landmarks, museums and memorials, enjoy our lakes, rivers, parks and recreation areas, and spend a leisurely stay in our favorite part of Nebraska.

Seven major reservoirs and a number of smaller ones dot this region, so water sport is plentiful. While visiting in South Platte territory, your family is never more than an hour's drive from "lakeside". You might want to write for a brochure for more details. At any rate, come visit us—you'll be glad you did.

FORTY-ONE MEMBER COMMUNITIES Alma Elwood Holdrege Arapahoe Eustis Indianola Aurora Farnam Juniata Axtell Franklin Kenesaw Beaver City Guide Rock Lawrence Bertrand Harvard Lincoln Blue Hill Hastings Loomis Cambridge Hayes Center McCook Campbell Hildreth Minden Clay Center Holbrook Nelson Curtis Orleans Oxford Palisade Red Cloud Roseland Stamford Stratton Superior Trenton WilcoxDerived from the rivers and streams of the Southlands are 12 major reservoirs hosting hundreds of thousands of visitors annually to swim, fish, picnic and ski, to camp and ski again, to hunt, or to do nothing at all. Camping facilities are on all of these reservoirs. Some are modern with camper pads, showers, hookups, grills, recreational equipment . . . the works. Others have nothing, except maybe a place to pitch a tent to absorb a world of beauty and peace.

Developed primarily for irrigation, low water in late summer at Enders, Swanson and Medicine Creek often leaves boat ramps great distances from the lake, although fishing holds up throughout the year.

If you play the odds, your best bet on taking bigger fish more often is cranking a lure through the waters of just about any southwest reservoir. Master Angler and state records attest to that, and records continue to be broken there. Sherman, for example, conquered the long-time Lake McConaughy northern pike trophy by producing 29 pounds and 3 ounces of toothy fury. Red Willow has the smallmouth record, while reservoirs like Harlan, Medicine Creek and Maloney consistently yield walleyes pushing and exceeding the 10-pound mark.

Striped bass in Harlan, Johnson and Maloney are starting to come into their own. Though not lunker sized yet, these saltwa- ter transplants, capable of disemboweling good reels, should fare well in Harlan County with it's long growing season.

Bobwhites are one of 38 species of game hunted in the Southlands of Nebraska. The Republican drainage offers excellent quail habitat, and stream beds like the Frenchman, Medicine, Brushy and Red Willow offer good woody cover, as do the canyons in these watersheds. Farther north, the willowed bottoms of the Platte amplify spring whistle calls of the bird that says its own name, but the river challenges any hunter as coveys play leap-frog with the channels. The eastern section of the Southlands, south of the Little Blue River, provides the state's best bobwhite hunting.

Excellent habitat development on most of the lands at the southwest reservoirs has resulted in down-to-earth quality hunting; no-permission-necessary type hunting; where ringnecks, quail and deer appreciate that kind of development. One of the few remaining strongholds for this avian Mongolian ambassador, the ringnecked pheasant fits well in the Southlands.

Not only are the wildlife lands of the big reservoirs excellent pheasant range, but so, too, is the rain-basin country farther east. Ducks and pheasants live side by side in those marsh areas, as the vegetation of the wet basins adjacent to surrounding croplands provides fringe area and diversity. Permanent cover can be found on the 40 federally owned basins and 5 state-owned marshes. Paramount in basin hunting is an area known to many as Sac, abbreviated for Sacramento Game Management Area, operated by the Game and Parks Commission for the benefit of the resources and for those who use them.

Although not managed for crops, they are incorporated intricately in the scheme, but cover is the name of the game and bird production is the fruit of the harvest. Rooster crowing resounds on the area for the first three months of warmth; then a month and a half of silence is followed by large broods of chicks chasing grasshoppers under the close scrutiny of mother hens.

Hunters come from as far as New York to hunt Sacramento, but hand in hand with good cover on wide expanses, goes tough hunting. Thick cover also means good carry-over so that the cocks will crow again come spring.

Waterfowl tops the hunting roster in the Southlands, and the rain basin holds an edge over most other areas. Space a few decoys along the bordering bulrushes, add a makeshift blind and a tough black dog, and hold onto your camouflage. Teal passing low over the yellowing rushes are more often than not sitting right in the middle of your spread before you even know they're in the county. And listen closely for the high cracking throats of the speckles that migrate early through the central basins . . . one of the only areas of the state where hunters have the occasional opportunity to get a crack at the Cadillac of geese.

But, enough of the little stuff. You say you're a big-game hunter. Although the game is no longer the same as in Cody's day, Nebraska's big three, whitetails, mulies and pronghorns, can all be found in the Southland.

More than 7,000 deer permits a year are offered in the region's six management units, which tailor the harvest to fit the area's population. The canyons are almost all mule deer, but you shouldn't be surprised if you jump a flag-waving buck out of a deep ravine.

Over in the corner of Nebraska's corner, the Dundy Unit supports scattered herds of bristle-rumped antelope . . . enough so that a season has been held in Chase and Dundy counties for the past 4 years. Only 10 permits were issued, but success is nearly 100%. North of the Platte, up in Custer County, pronghoms play the slopes to favor the wind; eyes scanning the horizon to self protect the limited numbers they have attained through the transplant efforts of man.

The antelope and prairie chicken of the south reflect the past of Nebraska: a plains country proud of it's rich heritage and colorful heroes.

Buffalo Bill Cody is probably the most colorful of all; an entertainer of the highest caliber. . . showman deluxe. Preserved from memorabilia of the past, Buffalo Bill's Scout's Rest Ranch in North Platte hosts more visitors than any of our State Historical Parks.

In those early days, fears of settlers were well founded when they involved the plains Indians as evidenced by the prairie outposts—huge fortresses such as Fort Kearny and Fort Hartsuff. Fort Kearny, forged from raw timber and sod along the Oregon Trail, provided protection for gold and land seekers of the 1840's. Reconstructed in detail, the fort stands again to host thousands of modern travelers seeking a taste of the past while traveling near the Oregon Trail on a strip of concrete.

Though short-lived in the late 1800's, Fort Hartsuff will live forever as a State Historical Park on the banks of the North Loup River near Ord. Not only did the fort protect white settlers from Indians, but it protected Indians from Indians. The Sioux Nation threatened all, including the friendly Pawnee, but Hartsuff and 100 soldiers intervened for seven years. Many of the original buildings, abandoned in 1881, are still standing, and repairs are underway.

Where these forts stand, rivers once carried Indian canoes and trappers' bullboats. The trend now is to return to the rivers . . . this time with modern canoes of glass and aluminum. A pilot canoe route has been established on the Republican,River and one is being worked up for the Tri-County Canal system. Other routes are slated for rivers of the southlands; a land of recreational benefits second to none, opportunities of the past and present, and with dreams of a future.

PHOTO CREDITS

Cover-Richard Voges; 4, 5, 6, 7—Jon Farrar; 8-Lou Ell; 9 top-Lon Slepicka; 9 bottom—Rocky Hoffmann; 10 top- Lou Ell; 10 bottom—Greg Beaumont; 11-Lou Ell; 12-Jon Larrar; 13 left-Jon Larrar; 13 top right-Rocky Hoffmann; 13 center right-Bill McClurg; 13 bot- tom right-Rocky Hoffmann; 14 top left-Lave Musil; 14 top right and bot- tom-Jack Curran; 15-Lou Ell; 16, 17- Jon Larrar; 18, 19-Lou Ell; 20-Bob Grier; 21 top-Lave Musil; 21 bottom- Bill McClurg; 22 top left and bottom right—Laye Musil; 22 bottom left—Greg Beaumont; 22 top right—Jon Larrar; 23—Greg Beaumont; 24—Bob Grier; 25 right—Jon Larrar; 26—Jim Hurt; 27— Rocky Hoffmann; 28, 29-Bob Grier; 30 top—Jon Larrar; 30 bottom—Rocky Hoffmann; 31—Jon Larrar; 32—Lou Ell; 33—Jon Larrar; 34—Greg Beaumont; 35 left—Lou Ell; 35 right—Butch Isom; 36— Faye Musil; 36 left-Jeff McCullough; 37 top—Jack Curran; 37 bottom—Rocky Hoffmann; 38—Rocky Hoffmann; 39 top left—Greg Beaumont; 39 top right-Lou Ell; 39 bottom-Rocky Hoff- mann; 40—Lou Ell.

Trading Post

Acceptance of advertising implies no endorsement of products or services.

Classified Ads: 20 cents a word, minimum order $4.00. February 1978 closing date, December 8. Send classified ads to: Trading Post, NEBRASKAIand, P.O. Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503.

DOGSQUALITY trained and partially trained hunting dogs ready for the 1977 hunting season. Limited number of English setters, pointers, and Brittanies. Darrell Yentes, 1118 McMillan St. Holdrege, NE 68949. Phone (308) 995-8570 after 5:30 p.m.

BEAGLES GALORE. Puppy love for sale. Our kennel runs over and we have the perfect family companion or hunting partner for you. Champion dams and/or sire. Tux Beagles, Route 1, Box 152, Raymond, NE 68428 (402) 435-1407.

ENGLISH SETTER PUPPIES. Excellent pups from known bloodlines and good hunting stock. $125 each. Stevens Creek Setters, Ken Hake, Route 2, Lincoln, NE 68505 (402) 488-0792.

IRISH SETTERS, German Shorthairs, Labradors (black or yellow) AKC $40.00, FOB Atkinson. We do not ship. Roland Everett, Atkinson, Nebr. 68713.

MISCELLANEOUSWANTED FOR 1978 .... additional locations for Wilson Outfitters Canoe Rental liveries. Prefer landowners with choice riverfront property 10 to 15 miles downstream from prime put-in points. Others considered. Wilson Outfitters provides canoes, paddles, jackets, canoe trailers, advertising, referrals, and know how. We have the track record! Opportunities for campground and car shuttle income, too! Locations wanted on Republican, Blues. Platte, Elkhorn, Frenchman, and Snake rivers. Write Wilson Out- fitters, 6211 Sunrise Road, Lincoln, Nebraska 68510.

DUCK HUNTERS: learn how, make quality, solid plastic, waterfowl decoys. We're originators of famous system. Send $.50, colorful catalog. Decoys Unlimited, Clinton, Iowa 52732.

GUNS-Browning, Winchester, Remington, others, Hipowers, shotguns, new, used, antiques. Want Pre-1964 Winchesters. Buy-Sell-Trade. Ph. (402) 729-6112. Bedlan's Sporting Goods, Fairbury, NE 68352.

HAND-REARED wild ducks: Wood ducks, Mandarins, European Wigeons and Red-crested Pochards. Mrs. R. W. Hansen, 3315 Avenue L, Kearney, Nebraska 68847.

WANTED FOR 1978. . . . additional locations for Wilson Outfitters Canoe Rental liveries. Prefer landowners with choice riverfront property 10 to 15 miles downstream from prime put-in points. Others considered. Wilson Outfitters provides canoes, paddles, jackets, canoe trailers, advertising, referrals, and know how. We have the track record! Opportunities for campground and car shuttle income, too! Locations wanted on Republican, Blues, Loups, Calamus, Dismal, Missouri, Platte, Elkhorn, Frenchman, and Snake rivers. Write Wilson Outfitters, 6211 Sunrise Road, Lincoln, Nebraska 68510.

METAL DETECTORS, Treasure books, prospecting supplies. Free catalog of our equipment. Exanimo Establishment, 335 North William, Fremont, NE 68025.

WANTED-Older Winchester pump, double, and lever shotguns in working condition, any gauge. Write Winchester, Box 30004, Lincoln, NE 68503.

WAX WORMS, 500-$8, 1000-$14, Postpaid, Add 31/2% sales tax. No. CO.D. Harold Malicky, Burwell, Nebraska 68823.

TAXIDERMYBIG Bear Taxidermy, Rt. 2, Mitchell, Nebraska 69357. We specialize in all big game from Alaska to Nebraska, also birds and fish. Hair on and hair off tanning. 4% miles west of Scottsbluff on Highway 26. Phone (308) 635-3013.

KARL SCHWARZ Master Taxidermists. Mounting of game heads-birds-fish-animals-fur rugs-robes-tanning buckskin. Since 1910. 424 South 13th Street, Dept. A, Omaha, Nebraska 68102.

TANNING-all kinds including beaver, coyote, raccoon, deer and elk. Many years experience in making fur skins into garments. Complete fur restyling, repair, cleaning and storage service. Haeker's Furriers, Alma Tanning Company, Alma, Nebr. 68920.

THE HOUSE OF BIRDS-Licensed taxidermist, 10 years experience in the art of all taxidermy. Larry Nave, 1323 North 10th, Beatrice, NE 68310. Phone (402) 228-3959.

FISH MOUNTING Service. Specialize in all fresh-water fish. Visitors welcome. Wally Allison, 2709 Birchwood North Platte, NE 69101, (308) 534-2324.

GREAT PLAINS TAXIDERMY, Creative and realistic mounts of Fish, Birds, Game heads, full mounts, and novelty. Pat Garvey, 3015 NW 52nd, Lincoln, Nebraska 68524. Phone 470-2280, Lincoln; 571-5630, Omaha.

KINSMAN TAXIDERMY, Ed Kinsman, Owner. Game heads, fish, rugs, tanning, and bird mounts. 10 years experience. (308) 995-8891, Holdrege, NE 68949.

WHITETAIL TAXIDERMY. Specialists in fur and feather. Latest methods. Beautiful mounts. 3264 16th Avenue East Columbus, NE 68601 (402) 564-6885.

COMMERCIAL tanning, rugs, true-to-life mounting of all trophies. We are also in the business to help you go hunting and fishing; we book hunts world-wide. Send self-addressed envelope for price list and brochure. DINGES TAXIDERMY STUDIO, 2760 S. 12th Street, Vi block N. I-80, Omaha, Nebraska 68108 (402) 342-3718.

JOHNSON'S TAXIDERMY, Route 1, Lamar, NE 69035. Quality mounting of birds, fish and big game from North America to Africa. Also rugs and tanning of any kind (308)882-5555.

ATTENTION Game-Bird Hunters! Keep Those Special Birds. Call John Rogers in York-Licensed Taxidermist- Phone York 362-3476, 362-4046.

AUTHORS WANTED BY NEW YORK PUBLISHER Leading book publisher seeks manuscripts of all types: fiction, non-fiction, poetry, scholarly and juvenile works, etc. New authors welcomed. For complete information, send for free booklet Ft-70. Vantage Press, 516 W. 34 St., New York 10001 House of Birds Price list for 1977 First 50 deer—$48.50; Pheasants—$28.50; Quail—$8.50 each or $15 pair; Ducks—$28.50; Bobcat—$65; Largemouth bass—$35. Price low but quality high 1323 N. 10th, Beatrice, NE 68310 Phone (402) 228-3959 TEACH ANY DOG IN MINUTES Complete system, book and device All you need to raise and train puppies, dogs of all ages. Never fails! Uses dog's keenest learning sense. CORRECTS • HOUSESOILINC •DIGGING • JUMPING • GUN SHY • CHEWING • BREAKING POINT • BARKING "OVER RANGING • BITING • BUSTING BIRDS SIMPLE EASY TO USE NOT ELECTRONIC TEACHES • COME - at all times • SIT • GO • HEEL • SELF CONTROL • STAY • GUARD DROP • FETCH Lasting, even in your absence WORKS with YOU —NOT off for himse'f ON TV with: Art Linkletter, Johnny Carson, Dick Cavett, Mike Douglas, Merv Griffin, "The Pet Set," "Friends of Man." ARTICLES: TIME magazine, NEW TIMES, HUNTING DOG & other worldwide publications. A scientific engineering marvel. This psychological dog-sound maker is used from the palm of the hand. Gives amazing control at a distance. "Works like magic.'' No leash needed. "Tunes dogs in." Makes dogs seem to "read your mind." Novices become experts. Teaches direct to the dog's mind via a new subliminal sound learning stimulus. Safe, faster, kinder, more effective. Renders all slower pain-train ing obsolete. Same instrument and system (utilizing the Dr. Miller patents) dispensed by veterinarians for dog behavior. Now hundreds and thousands of satisfied users, breeders, trainers, U.S.A. & foreign lands FREE illustrated dog psychology book-brochure. DOG-MASTER SYSTEMS Dept Nil 7 710 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 318, Santa Monica. Calif. 90401 A division of Environmental Research Labs. Copyright 1977 LIVE-CATCH ALL-PURPOSE TRAPS Wrltotor FREE CATALOG Low as $4.95 Traps without injury squirrels, chipmunks, rabbits, mink, fox, raccoons, stray animals, pests, etc. Sizes for every need. Also traps for snakes, sparrows, pigeons, crabs, turtles, quail, etc. Save on our low factory prices. Send no money. Free catalog and trapping secrets. MUSTANG MFG. CO., Dept. N-34, Box 108S0. Houston, Tex. 77018 "A Friendly City Full of Friendly People" Welcome to AURORA NEBRASKA Aurora, the county seat of Hamilton County, is the "Deepwell Irrigation Center of the Nation." Aurora has three parks, with tennis courts, a swimming pool, and fine camping facilities for your enjoyment. All services available. The Plainsman Museum is located 3 miles north of the Aurora I-80 exchange on Highway 14, or is 1 mile south of Highway 34 and 14 junction, on Highway 14. HOURS: April 1-October 31 9:00 A.M.-12:00 P.M. and 1:00 P.M.- 5:00 P.M. Monday thru Saturday; and 1:00 P.M.-5:00 P.M. Sunday. OPEN YEAR ROUND November 1-March 31 1:00 P.M.-5:00 P.M. Daily. Closed: Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year's Day. For Information Contact: Aurora Chamber of Commerce 402-694-6911 Aurora, Nebraska DECEMBER 1977 49

SETTLEMENT AND GROWING PAINS

(Continued from page 41)With the Indian and the buffalo gone, the plains were open to white settlement, and as the Indian was pushed farther and farther west and north, more settlers came to replace him.

Land law, railroads and railroad colonization were major forces behind the mass movement onto the plains. The Homestead Act of 1862 gave settlers 160 acres of land for the price of filing and living on or cultivating that land for five years. That cost, however, was often more than the hopeful settler could pay, and more than half returned to eastern homes "busted".

Those who stayed grew with the harsh land they had set out to conquer, facing dust, drought, blizzard and 'hoppers that killed livestock, crops, people and often, human spirit.

The railroad colonies may have fared just slightly better if only because there's safety in numbers. The railroads were given 20 sections of public land for every mile of track laid. With an eye to profit, of course, they wanted to sell that land. But, they had an interest in the settlers' success, as well, for there must be goods to ship if the venture was to pay. Only the settlers could provide the produce.

Over the years, Union Pacific and Burlington sold some seven million acres of land. Through intensified advertising in the east and overseas, the railroads sought to dispel the rumors that Nebraska was the great American desert. "Rainfall follows the plow," became a catch-phrase of that campaign.

And the people came, in colonies held together by common national heritage or perhaps common religion, or both.

Business ventures built up around the colonizing, and the Rankin Colony, formed in Omaha, was the first to attempt settlement in the Republican Valley. They arrived at Guide Rock in 1869 and began to build the first house, but an Indian scare drove them out.

The first permanent settlement in the valley was begun at Red Cloud in the summer of 1870. Silas Garber opened one of the most important movements of that time with his first settlement.

While farmers were colonizing the river valleys, cattlemen were also laying claim to the ranges.

The first cattlemen had come to Nebraska much earlier. The mixed-grass prairie between the Platte and Republican and in the South Loup Vailey became the base for cattlemen as they still viewed the Sandhills as a desert. Frontier County was organized in 1872 to establish the cow, and the name of the county seat, Stockville, was appropriate.

When settlement along the Republican receded with the drought and the 'hoppers, cattlemen moved into Furnas, Red Willow, and Dundy counties.

Then as settlement and range began to meet, range wars broke out in a series of skirmishes that cost some iives and resulted in Nebraska being dubbed the "man-burner state".

The best-known incident of the wars was the conflict between Print Olive and Ami Ketchum. A typical skirmish near Plum Creek resulted in the shooting death of Bob Olive, Print's brother. Print hunted down the men responsible, Ketchum and his neighbor Luther Mitchell, hanged them, and burned the bodies.

As the echoes died on Indian wars and range wars, Nebraska farmers and ranchers were left to the silence of the plains, the slice of the plow, the moan of the wind in the tall prairie grasses. They had persecuted the buffalo and an entire race of people who had depended on it. They had left behind their own dead, their own homes in another country or another place, and their own way of life. And, they shaped themselves to the endless, rolling country they had adopted, meanwhile trying to shape that country to themselves.

They grew up an independent, skeptical, hard-working, long-lived group of often-cantankerous people whose own history continues to ebb and flow with the rising and falling of the winds and the water table.