NEBRASKAland

special deer hunting section

NOVEMBER 1977 60 Cents

NEBRASKAland

Published by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission

VOL 55 / NO. 11 / NOVEMBER 1977

commission Chairman: Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District (402) 371-1473 Vice Chairman: William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District (308) 432-3755 2nd Vice Chairman: Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-central District (308) 452-3800 H.B. (Tod) Kuntzelman, North Platte Southwest District (308) 532-2982 Richard W. Nisley, Roca Southeast District (402) 782-6850 Robert G. Cunningham, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District (402) 553-5514 Shirley L Meckel, Burwell North-central District (308) 346-4015 Director: Eugene T. Mahoney Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, Jr. Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree staff Chief, Information and Education: W. Rex Amack Editor: Lowell Johnson Senior Editor: Jon Farrar Editorial Assistants: Ken Bouc, Bill McClurg Field Editors: Bob Grier, Faye Musil, Roland Hoffmann, Butch Isom Art Director: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita StefkovichCopyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1977. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska

Contents FEATURES SKI TOURING NEBRASKA 8 SURVEYS FOR SURVIVAL16 A COMMISSIONER LOOKS AT CONSERVATION 18 DETOUR FOR DUCKS 20 SPECIAL DEER-HUNTING SECTION 22 BLACK-POWDER WHITETAILS 24 A RETURN TO DESOTO BEND 30 BACK-COUNTRY BUCK 31 LOOK TO THE HILLS 32 A DEER EXPERIMENT ENDS 34 A JERKY FOR ALL SEASONS 36 ADVENTURES WITH WHISKERS/Badger Meadow Gang DEPARTMENTS TRADING POST 49COVER: This fine mule buck would be ample reward for a hunter who had trailed htm through rough country on snowshoes in the finest tradition of the classic old hunt. Photo by Jon Cates. OPPOSITE: A duck hunter silhouetted in low light is also a segment in the vast scheme of outdoor recreation, and harkens up nostalgic memories that only hunters can appreciate. Photo by Bill McClurg. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, P.O. Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Rates: 60 cents per copy; $5 per year; $9 for two years; $12.50 for three years.

NOVEMBER 1977 3

Speak Up

Where Does Money Go?Sir / I am a hunter and fisherman and do not understand why part of our license fees go to maintain our park system. We always thought the Game Commission should be just that and all fees used for this department. Why not let the people who use the parks pay their own way, mostly tourist, same as our outstate hunters and fishermen.

Now that the habitat stamp is in effect, I hope the proceeds are used for our game and fish only.

I would appreciate a reply.

Wallace T. McKinney Beatrice, Nebraska

Hunt and fish funds don't go to maintain or build parks. Those monies come from general tax revenues. (Editor)

Bad DealingsSir / In Speak Up, I would like to add to the letter headed "Death Dealer". I've seen acid from batteries dumped into the sink at an automotive service station. I've also seen discarded anti-freeze dumped into the floor drain. I believe that 95% of all filling stations are guilty of the aforementioned practices. Anti-freeze and sulphuric acid used in batteries are deadly poisons, perhaps even worse than salt. When will this practice be prohibited? It certainly isn't good for our dwindling fish population.

Tom Hennessey Octavia, Nebraska Old, Cold TimesSir / I am writing to you as I was also (and my brother) born in a sod house in Antelope County 31/2 miles west of Elgin, Nebraska. I was born in 1898 when there were prairie chickens most everywhere. Also, the wild geese flew back and forth spring and fall. We drove to the town which had just a few stores, as the elevator and lumber yard run by Bill Lehr. He also sold coal. Our county seat was Neligh, and the old sheriff's name was Bennett. He used to carry a .44 in his holster and a 30/ 30 beside him near his feet. There weren't many holdups then. One winter it was cold, that was in 1906, and a man named John Sole was going home one day and it was snowing and cold. He made a big hole in a haystack and crawled in to keep warm, and his 2 ponies were there to eat hay. The next morning the sheriff was looking for him and found him in the hay stack frozen to death. The temperature went down to 30 below zero. They found his ponies and rig some distance off. Probably looking for water on that dry hay. Many days we had drifts clear over the kitchen door. Had to tunnel out to do chores. My daddy tied a long rope from the house to the door of the barn so he could find the barn door. He opened the corral gate to let the cattle to the hay stacks. The pigs would burrow through the drifts to get to the creek to get water. We oldsters never will forget those days. I live now in Denver where they all want water and get very little snow, yet east 40 to 50 miles there's 10-foot drifts that must be plowed out. My wife passed away and left me a lonely man. Still able to go to the Rockies to "find that gold." I am a veteran of World War I and was wounded in France in 1918. I would like to have someone write to me. My one school teacher was a daughter of Sheriff Staple of Neligh. Her name was Nelly Staple and her sister, Flora Staple.

Paul B. Pinnt 744 South Knox Court. Denver, Colorado 80219 Like to FishSir / We went down to Kansas for the weekend and the Ranger came to check us out. People 65 years of age do not have to pay in a state park. And, if I lived in Kansas I wouldn't have to buy a fishing permit, either. Same way in Iowa. In South Dakota they buy permits every three years for their boats, same way in Kansas. We have to be 70 years of age in Nebraska before we don't have to have a fishing permit. We older people like to fish too. But who cares about us? Why can't Nebraska think of those who have worked and paid taxes until they retired. I have lived in Nebraska all of my life.

Mrs. Roy O. Heath Lincoln, Nebraska Unfortunately, our agency doesn't operate entirely from tax revenue, and free permits for some puts a heavier load on others. There are a lot of inequities which perhaps will be worked out some day, but for now, bear with us. (Editor) Unhappy AnglerSir / After receiving my February issue of NEBRASKAIand I came to one conclusion after seeing the increase in nonresident fishing fees go from $15 to $30 and 5-day permits go from $5 to $15. I am sure I will no longer be coming to Nebraska as in the past. I am now a retired police officer and after 23 years of service I am on a limited income, and will be unable to pay such fees plus park permits, etc. I have been coming to Nebraska from 1 to 3 times a year since 1947 to fish, boat and camp. I understand what the Commission's Habitat plan is for and I know it will take a lot of money to accomplish this goal, but I wonder how many nonresidents Nebraska will lose by this increase in fishing fees.

Victor Sterkling Quinter, Kansas Words From A FriendSir / Please find enclosed my check for two-year subscription to NEBRASKAIand. I was born on the banks of the Platte River near Silver Creek in 1905. People like to recall the "good old days," but if the hunting had been as good then as it is there now, I probably wouldn't have left. Kidding aside, I think you have the nicest outdoor magazine I have ever read and I wouldn't be without it.

Floyd W. Wisely, Enterprise, Oregon What A ChangeSir / The 4th of July we drove to Ogallala to spend the day at Lake Mac. What a change! Houses and cabins cluttering the beautiful hills. I was disappointed when I first saw Johnson Lake. It looks more like a town than a lake with its wall to wall houses. So will Lake Mac in a few years. I saw where sewage from several business places was running into the lake. Soon it will be just another polluted mess. It's hard to find a clean uncluttered beach there anymore. Why is this allowed? Before long there will be no natural spots to enjoy. Recently we visited Red Rocks Park near Denver. Houses are being built there too. I think it is terrible. Its beauty is being destroyed.

Mrs. Eloise Burk Atkinson, Nebraska Don't Hound Us!Sir / I admire your magazine very much and I was very disappointed that you would print such a story as "Following the Hounds" in the February issue. I can see no justification for coon hunting-it provides no food but is cruel and senseless slaughter merely for the pleasure of killing. This was aptly demonstrated by the article, but I found it very objectionable and contrary to the standards of sportsmanship and conservation which you normally uphold.

Cynthia Jacobsen Peru, Nebraska 4 NEBRASKAland

World SURPLUS CENTER Famous

THERMOS Stainless Steel Unbreakable Vacuum Bottle1978 NEBRASKAIand Calendar

SKI TOURING NEBRASKA

Cross-country or "skinny" sticks make sense with areas offering terrain for beginners and pros. Snowfall is only uncertainty

SKI TOURING is an exhilarating sport that captures the spirits of winter buffs throughout the snowbelt states. Invigorating to body and soul, cross-country skiing invites one to take the time to see where the deer tracks in the snow lead, and to contemplate how life really was many years ago. The sport affords a place for everyone, and at chosen speed.

Although participation in this country is relatively recent, it is by far the oldest form of skiing in the world. Resourceful Scandinavians are credited

8Indian Cave State Park

Newest park offers historical and scenic highlights to enthrall the skiers using 38 miles of trails

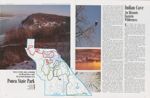

Ponca State Park

Variety of trails, many overlooking the Missouri River, make this an ideal all-purpose areawith creating the ski at least 4,000 years ago; a natural development for the long and harsh winters in their land. Their primitive skids have since evolved into modern skis which fit the needs of any cross-country enthusiast. Additional information on the history, equipment and techniques of Nordic skiing can be found in the "Ski Nebraska" article of the February, 1976 NEBRASKAIand. For those desiring more information before clicking the bindings shut for the first time, numerous books are available on the subject at most libraries.

Ski touring is breaking trail this winter with the Game and Parks Commission as a practical activity for Nebraskans during a time when outdoor recreation usually slows to a trickle. The Commission operates 92 areas regularly used during three seasons of the year, but the potential exists for extending use on them to the fourth, winter season.

Usage of state areas has always been substantial, and last summer, many areas showed a marked increase over previous years. Nebraskans are looking for places closer to home for their recreational vacations; not surprising with the "energy grinch" dipping his oily hands into everyone's pocket. The Commission desires to accommodate this need, and the canoe pilot projects are a prime example of this desire attained. Skiing is also a sport that Nebraska can accommodate Nebraskans with, and in a relatively inexpensive manner.

The price of an average snowmobile would buy at least 10 sets of Nordic gear. Cross-country skis, boots and poles can be purchased for the cost of an average pair of Alpine boots alone! Another cost-saving aspect of crosscountry skiing is its flexibility. Much of the practical Alpine ski equipment can be used for both types of skiing, and certain regular winter wear can be used as well. Many items used for backpacking can also be used for tourpacking. There are even bindings and skis that will fit to a hiking boot.

The potential for ski touring Nebraska is largely untapped, existing in the shadows of Nebraska's mountainous neighbors. But there are adventuresome spirits who have blazed tracks already. Make no bones about it—Nebraska isn't normally blessed with the continual snow cover of its northern (Continued on page 46)

Indian Cave

An Historic Eastern Wilderness

THE NEWEST state park encompasses 3,000 acres of largely virgin land, hugging the Missouri River with densely wooded bluffs for some three miles. The park is extremely rich in history. Skiers can glide through the remnants of St. Deroin, a riverfront settlement whose roots trace back to the 1850's.

Most of the present-day park roads follow the old Star Route, a road which connected many small settlements used as stopping points by trading and supply boats plying the Missouri. On the southern end, petroglyphs from prehistoric Indians still remain on the cave walls.

The one tent campsite available in the winter is very close to the original St. Deroin townsite. Settled by a halfbreed, temperamental Otoe chief named Joseph Deroin, the "Saint" was added to the town name after his death in hopes of attracting more settlers with the fancier title.

From this base camp, there are numerous beginner and intermediate tours.

A historically interesting side trip from the tent camp area is to the HalfBreed Cemetery. Many white trappers and traders took Indian wives in the early days, producing the half-breeds that eventually would be buried in the cemetery. However, the town's namesake was a half-breed, and Deroin is believed buried astride his horse in the St. Deroin Cemetery, on higher ground. His exact resting place remains a mystery.

The central section of the park is for more advanced skiers. On Rock Bluff Trail, there are three new and spacious Adirondac shelters. Ideal for the over- night skier, the shelters are enclosed on three sides as well as the roof. Es- tablishing base camp at this centrally located site can enable skiers to plan their excursions to any portion of the park and back in a long day.

11

The south trails, particularly the road, are good for beginning and intermediate skiers. The most difficult part is the first road after the winter gate. It is steep and curving, and with a southern exposure, the tendency for ice buildup is great. If it is icy, work safely down it and the rest of the trip to the cave is scenic and relatively simple.

All in all there are 20 miles of hiking trails, 10 miles of horse trails and 8.5 miles of vehicle roads at Indian Cave. Eagles also visit the area in the winter: a welcome sight anytime.

Ponca Day Skiers Delight

PONCA STATE PARK'S 836 acres are poised atop scenic bluffs over-looking the powerful waters of the Missouri River. Established in 1934, it is an increasingly popular summertime retreat. Its 15 to 17 miles of horse and foot trails are readily adaptable to Nordic skiing.

Ski-backpackers can camp in the day-use area north of the cabins. Like Chadron, all areas are accessible from the campsite, it being an excellent day-ski area as well.

The Lewis and Clark Trail Tour begins just north of the pool and parallels the Missouri River atop the wooded bluffs for over a mile. The scenery is beautiful; a nature photographer's delight. When the stone shelterhouse is reached, a curving down and uphill road tour to the southernmost portion of the park is a challenging intermediate skier trip. The

12 NEBRASKAlandother option at the shelterhouse is to continue across the road on the trail. Negotiating a steep curve downhill brings one to the main road into the park. The Woodbine Trail picks up there and winds through the dense trees either back to the pool or into the middle of the park where additional trails may be taken.

For the advanced skier, the northern section of the park is the place to be. A new trail broken this summer begins off the service road at the west end of the camping area. The trail is narrow and follows the contour along steep hillsides much of the way. It opens up on a hill overlooking the Missouri and nearly all of the park grounds. It's probably the best view in the park, and it takes a skilled skier to get there.

The unplowed roads at Ponca will make excellent ski tours for intermediate and advanced skiers. The roads around the cabins and into the closed camping area are constantly rising, dropping and curving.

Bald and golden eagles are known to winter roost at Ponca. Other wildlife to look for includes deer, turkey, pheasants and quail.

Chadron A Family Retreat

THIS AREA was Nebraska's first state park, established in 1921. Its 840 acres are remarkably well suited for cross-country tours. Overnighters are restricted to the camping area behind park headquarters, but all areas of the park are within a day's tour of the site. Lodging is available in the town of

NOVEMBER 1977 13

Fort Robinson State Park

Chadron, 10 miles north of the park.

Chadron Park is excellent for a dayuse ski touring area. The whole family, skiers or not, could enjoy the stay. A good sledding hill is located near the pool, and the park lagoon provides ice skating and fishing.

Road tours around the camping and cabin areas are perfect beginner tracks. Trail tours for intermediate skiers wind through the cedars, never retracing a track. Be sure to start on the southernmost trail at the trail head near the multi-use facility. Switchbacks along the way can be handled going up, but are rather hazardous going downhill.

For the advanced skier, the northwest day-use area is the challenge. Fire swept through Dead Horse Canyon in the park in July of 1973, destroying 3,100 acres. The steep hills and deep canyons, the burnt trees and the unharmed forest, all combine to make the area one of striking contrasts. Exploratory tours in this area are for ad- vanced skiers only.

A Western Adventure Fort Robinson and Soldiers Creek Management Unit

NEBRASKA'S largest state park affords unlimited skiing for persons of all abilities. Including the adjacent, federally controlled Soldiers Creek Management Unit (commonly known as the Wood Reserve), there's approximately 40,000 acres to stride into.

The Fort played an important role as a frontier outpost in the post-Civil War days, perhaps best known as the place of Crazy Horse's demise. The 10,000-acre James Ranch, obtained by the state in 1973, filled the gap between the Fort and the Wood Reserve.

The fort has long been a popular summertime retreat for vacationers. The deciduous woodlands along Soldiers Creek blend gently into grasslands that climb to the Ponderosa Pine buttes that dominate Fort Robinson's horizons. The timeless setting teases the mind back into the wild west era of a century ago.

Three well situated base camps are advised for skiers, although one of the joys of packing gear in on skis is being able to set camp wherever the heart desires. Most accessible to highway 20 is the campsite just south of the Troop Lodge. The most central location is at Carter D. Johnson Lake. Located just east of the James Ranch turnoff, this spot would be ideal for those planning on spending more than one night in the area. A third campsite just off the road before the Wood Reserve boundary serves the exploratory tourist best.

Red Cloud Agency AreaPicnic and road tours combine for a tour catering to the novice skier and wildlife buff. The gentle terrain provides a great opportunity to get into the graceful rhythm of the sport. The route goes by the winter pasture of the park's buffalo and long-horned cattle herds. Deer, antelope, coyotes, pheasants, owls, raccoons, skunks, porcupines and bobcats are among wildlife to watch for.

The tour goes by the Red Cloud Agency site, the white man's first official outpost in the area. Continuing down the hill from the agency site is a memorable, sheltered picnic area.

Red Cloud BluffsAccess to the bluffs is across from the first "Fee Fishing Area" sign on the road to the Wood Reserve. The fence encloses a tantalizing variety of terrain for skiers of all abilities. Advanced skiers will want to follow the fire lane up into the heart of the historic bluffs. Saddle Rock Butte, Lover's Leap, Giant's Coffin—the very names reflect their spirit.

Tours are largely exploratory in the grasslands below the bluffs for novice skiers. In the cedar-clumped high bluffs, horse trails and fire roads are handy if a trail tour is sought by the advanced skier.

Carter D. Johnson Lake to Smiley Canyon Road TourThe effort expended to reach the top of the road from the lake will be well worth it. Depending on where the road is met, there's a 4 to 6-mile twisting, turning, downhill run in store. From there it's an easy stretch through the hills back to the lake or to the lower campground and lodging area. A good full day's grip and glide for an advanced skier is involved in this tour.

The James RanchThe James family established their ranch during homesteading days, and it is a scenic, rugged spread. Later members of the family started the jeep trail ride and the group cookout which are now an integral part of the park's summertime fun.

Driving to the ranch will be possible, but obtain permission at headquarters before parking. Evergreens cover the hills north of the ranch, which are ideal for exploratory touring by confident intermediate and advanced skiers. There are some horse trails and fire roads to follow, and keep a sharp eye out for wildlife.

Wood ReserveThe Wood Reserve accommodates skiers of all abilities. A road tour for novices follows the old Hat Creek to Fort Robinson military road. The intermediate could stray off the road up into the lesser hills for some short downhill practice. The advanced skier seeking a challenging and scenic exploratory tour will love Trooper Trail. The trail head is just beyond the high fence that is about one-half mile into Reserve land, and the trail winds into the bluffs above.

With the vast and secluded land in this area, it is essential that park personnel know the plans of skiers. A little time at the beginning of the trip could mean much-needed help before it is over.

Cross-country skiing is a physically demanding and mentally rewarding experience, one that the Game and Parks Commission believes everyone physically able can learn to enjoy and cherish. Whether it's a three-day expedition or a three-hour tour, it leads toward the same goal. Mind and body seem to work in blissful harmony, and gliding along, the awesome elements of nature evoke a sense of freedom and serenity, a feeling of peace with the ways of the world that is very gratifying.

NOVEMBER 1977 15

Surveys for Survival

WE HAVE LEARNED that game, to be successfully conserved, must be positively produced rather than negatively protected. . . . We have learned that game is a crop, which Nature will grow and grow abundantly, provided only that we furnish the seed and a suitable environment."

With those few words of Aldo Leopold in 1925 dawned a unique new era of wildlife management . . . an era brought on by the sudden and awesome crash of the richest game populations ever recorded in history.

Just three years later, Leopold, a forester from New Mexico, was appointed chairman of the 1928 American Game Conference to lead a com- mittee of conservation greats to a solution of America's wildlife problems.

In December of 1930, a revolutionary report, which was to change the entire scope of game management, was finished. The conclusions in that report were so far-sighted that they still provide the basis for modern game management nearly 50 years later.

The new American Game Policy, established in 1930, recognized the urgent need for scientific facts concerning game species, and set seven vital goals that must be met in order to slow or reverse the downward population trend of wild creatures. One of the most important requirements demanded in the seven-point thesis was the training of men for skillful game administration, and who would make game management a profession.

Game management has become more than a mere profession for the majority of our state's wildlife biologists. It has become a way of life and an obsession for fact-finding to insure the propagation of abundant yet tolerable levels of wildlife.

Game surveys are the biological basis for nearly every game management decision imposed in modernday conservation. In Nebraska alone, more than 30 individual surveys are conducted annually; however, special surveys may be initiated if a need so dictates.

Special survey data, for instance, was collected over a 10-year period and was then discontinued due to lack of statistical variance. The survey started as a result of concern among deer hunters that Nebraska's liberal deer season was resulting in a shortage of male deer. The fear that not enough does were becoming pregnant, due to the harvest ratio, prompted the Game and Parks Commission to develop a deer productivity study. Over the survey years, every available highway- killed doe, both white-tailed and mule deer, was inspected for fetus development. Results of that survey proved that hunter concern was unfounded. The higher buck deer harvest ratio was not in the slightest way lessening the doe pregnancy rate, as survey results verified that virtually 100 percent of all adult (21/2 years and older) white-tailed and mule deer does were carrying fawns. Surprisingly, 95 percent of all yearling whitetails and 83 percent of all yearling mule deer does were also pregnant, and the survey further revealed that 62 percent of all fawn whitetails studied had fetuses. Even more encouraging was the finding that the average number of fetuses per doe whitetail was 1.83 . . . more than making up for any slight void of pregnancies.

Annual game survey projects enhance the fact-finding efforts of modern game management and provide yearly inventory and maintenance data on our huntable species.

Hunting is a tool of game management and an acceptable practice under the definition of conservation, which is the wise use of our wildlife resources. But, hunting must be regulated, seasons must be set, limits imposed, and the land managed. Surveys provide the basis for such regulation and related management practices.

That wildlife replenishes itself and makes a surplus is a fact. What that surplus will amount to would be an unknown factor without survey data. Studies that determine the number of young produced by a certain wildlife species are known as production surveys. Production surveys are conducted annually on all of Nebraska's game species, using a variety of techniques and allowing actual observance of young with parent.

A typical example of a production survey includes those conducted throughout the wild turkey range in the northern Panhandle and along the Niobrara River. Data is collected during peak feeding activity in the early morning and late evening. Hens and young are recorded, which gives a final figure on percentage of hens successful in raising a brood, average number of young per brood, and perhaps an indication whether a normal hatch has occurred. An annual average is thus established governing management decisions on the particular species surveyed. If the surplus of young turkeys produced for a given year is minimal, that decline will be reflected in the biologist's recommendations for the following season.

Equally important is the number of breeders that have survived the winter and the previous fall hunting season. Annual breeder surveys are conducted to obtain this information prior to production. The most sophisticated breeding population studies are the morning dove surveys, which are set up by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and carried out by state and fed- eral personnel. Twenty-mile survey routes are picked at random, which eliminates bias in choosing only high population areas. Routes are just as likely to be run through sparce sagebrush pastures as through treecrowded valleys and streamcourses where breeding populations would be expected to be high.

Such additional data as wind velocity, cloud cover and temperature are entered at the beginning and end of each route. The observer must begin at the first segment of the 20-stop route precisely 30 minutes before sunrise. The survey relies on both visual and auditory documentation. "Coo" calls and (Continued on page 46)

16 NEBRASKAIand

A COMMISSIONER LOOKS AT CONSERVATION

William G. Lindeken of Chadron was appointed to fill out a vacancy, and is now near final year of his own 5-year term

I BELIEVE THAT our state parks have a lot of potential, and the continuing upgrading of our recreational areas has been one of my concerns since going on the Game and Parks Commission about seven years ago. We have come quite a ways, but I hope we can go much further. Visitation at our two state parks in the Panhandle has jumped tremendously in the last few years, and the energy crisis will make our park areas even more important in years to come as people will just not be able to travel as far as previously.

Fort Robinson and Chadron State Park are good examples. We are trying to develop good family recreation areas with almost every kind of recreation—something for everybody.

We have been following the Wilcox plan for the development of Fort Robinson. Right now we have picnicking and camping, horseback trails, and jeep rides into butte country. People can play tennis and visit the historic museums and areas of historical interest. One of the most important additions will be the construction of a swimming pool at Fort Robinson. The pool at Chadron State Park is extremely popular with park visitors, and a pool is needed at Fort Robinson to provide something for the younger family members.

We also hope to add a visitor center at the Fort. Of course, the roads need work and we are in need of a modern campground. It all takes time, effort, and more importantly, money.

The Fort Robinson complex is over 11,000 acres, with the adjacent James Ranch holding another 10,000. The James Ranch and Peterson tract provide more of a wildlife area, with backpacking and horseback riding. They are a valuable part of the overall recreational opportunity that the public can find at Fort Robinson.

Chadron is the oldest state park in the state. This land was deeded in the early 1930's, but the park began even before that. Activities at Chadron include picnicking, camping, swimming, non-power boating, fishing and horseback riding. Again, something for just about everyone. Group camps and cabins are also available. Visitation at Chadron State Park was around a quarter of a million people last year.

I think a great number of people will use our state parks as a base camp for short trips into the nearby Black Hills in South Dakota, as well as hunting and fishing in the Pine Ridge and elsewhere. They may go to the Black Hills, for example, then come back and stay at one of our state parks. We expect to build a few more cabins at Chadron State Park, as well as provide an up-to-date campground facility. More and more people are using both Fort Robinson and Chadron state parks, and some of the costs for the improvements should come from their pockets.

We have some pretty good fishing at both Fort Robinson and Chadron, with the area offering both stream trout fishing and several small reservoirs, including Box Butte and Walgren.

Walgren gets a lot of use, and is well known as a bullhead lake. We installed a pump there two years ago, and it has been pumping fresh water into the lake in an effort to get both the water quality and level up. Walgren once had a flowing inlet, but that seems to be gone with the drought and lowered water table.

It seems like everything is interrelated. I know that around home our dams are dry, and our water table has dropped. Our habitat and land use have changed over the past 20 years, affecting the wildlife.

I try to travel through my district often, and thus have the opportunity to visit with people. Perhaps the biggest concern I hear from Panhandle residents is the drop in the pheasant population, and our spring blizzards the past few years haven't helped that. Again, things work hand in hand: our habitat has changed, and both the weather and predators can find more birds when they have no place to hide.

The new habitat bill will work out real well. We know it will not take care of all our problems, but we are trying to do something to help hunters and fishermen help themselves.

I am concerned about the deer situation, also. We've had quite a drop in our deer population in the Pine Ridge due to disease and other natural causes, and have lowered permit numbers, but I'm not sure that the cutback was enough. Ordinarily, we winter between 75 and 100 deer on our ranch, but this year I have seen three. We have to reduce harvest to provide growth for the herd, and I hope that the limited permits is a step in the right direction.

Big game is an important part of the Panhandle, with antelope, deer and turkey hunters traveling here from all over the state.

Our antelope and turkey populations appear in good shape. The antelope is probably the most difficult species to set seasons for. We find that our antelope move around,

18 NEBRASKAIandmaking it difficult to prevent winter depredation in some areas.

I believe that our turkey flock is also in good shape. It is quite something to see about 100 turkeys crossing a field, picking up bugs and scratching for seeds. A funny thing is that you are likely to see turkey almost anywhere in the spring. They move around considerably. We have had them visit our patio, and even walk around the house. Turkey hunting is a great sport, especially in the spring.

I run about 200 cows, and farm about 1,400 acres, primarily wheat. Everything seems to come at once, and I can't find time to do as much fishing or hunting as I would like. I sometimes get out for an hour or two at a time. Several years ago I killed a spring gobbler while I was out fixing fence, but it seems like every season that the weather cooperates, there is always something else that has to be done.

Oliver Reservoir down (Continued on page 45)*

DETOUR FOR DUCKS

When our goose hunt was scrapped in favor of duck shooting, we hadn't figured on the ice. However, once we cleared a small hunting patch on the Loup River, mallards were ours for the taking

LITTLE GRUNTS and quacks of duck conversation and the sound of 80 pairs of wings i just a few feet overhead were the first clues we had that any ducks were near. It was a sound that has quidcened the pulses of generations of waterfowlers; a sensation that we now shared with them.

We had driven 100 pre-dawn miles to hear those sounds. We had even passed up space in a prime goose blind for a chance like this. We had kicked through three-inch river ice and frozen our tailfeathers in the drafty, damp plywood and burlap blind for this. And after all of that, we had blown it.

Our shotguns were way back in the blind, where they belonged, but Marty Sterkel and I were on the outside, fiddling with the decoys or involved in some other foolishness.

We flattened ourselves in the cattails at the first sign of the ducks, hoping that our companions still inr the blind would get a shot. But they were silent, too; at first from sheer surprise, and after a few seconds, out of concern for Marty's and my whereabouts. After a couple of passes, low enough so that we could actually see their eyes dancing, the greenheads

20 NEBRASKAlandturned upriver without a shot being fired.

That's the kind of incident that makes duck hunting a great sport. Foolish mistakes or bad luck make great stories when the season's over. But immediately after some such misfortune strikes, waterfowlers are entitled to be upset, and we were, even though there was no one to blame but ourselves.

When those mallards surprised us, we were on the Loup River in central Nebraska, several hours from where plans of a couple of days previous would have put us. We had really figured on doing a little snow goose hunting along the Missouri River before we had been detoured west for ducks.

It would have been a perfect November day for goose hunting. We were all on short vacations for deer hunting or other equally good cause, and we had a blind waiting for us at the Plattsmouth Waterfowl Management Area.

It was perfect, except that goose hunting at Plattsmouth had run into a snag. The migration of snows and blues was unusually late, and the birds already using the area were wise to the ways of hunters by that late in the season. Only a handful of (Continued on page 42)

NOVEMBER 1977 21

SPECIAL! 16-PAGE DEER HUNTING SECTION

AT THE TURN of the century, it was estimated that only 50 deer existed in Nebraska. With complete protection, the state's deer herd climbed to some 2,000 or 3,000 animals by 1940. The first limited hunting season was held in 1945 and annual seasons have been "the" hunt for many of the state's sportsmen every year since 1949. Today, hunters enjoy some of the nation's top deer hunting. Last year over 35,000 sportsmen took to the field with rifle and bow. Over 14,000 rifle hunters and 1,183 archers returned with their winter's venison. Despite declining habitat and a bout with disease, Nebraska's deer hunting outlook remains promising.

NOVEMBER 1977 23

BLACK-POWDER WHITETAILS

PROBABLY NO GROUP of Nebraska deer hunters had better odds of taking trophy whitetails. It was Saturday, December 18,1976 and the opening of the state's first deer season restricted to hunters using muzzle-loading rifles of .40 caliber or larger. The hunt was on the DeSoto Refuge just across the Missouri River from Blair in some 1,700 acres of dense, river-bottom woodland interspersed with cropland. It was the first deer hunt held on the refuge since 1969, and expectations of taking a trophy were on the minds of most of the hunters who waited in the pre-dawn darkness to be checked in at the headquarters.

By 7 o'clock in the morning, hunters were dispersed over the refuge and were moving into the floodplain forest to their stands. Many knew the refuge well and headed directly to their selected spots; others were looking for signs of deer as dawn spread over the eastern sky. Wherever they chose to take their stand, the hunters' odds of seeing deer were high. The previous night, I had driven through the refuge. I finally stopped counting does when I reached 46, and in just over one hour, I had seen 17 different bucks, four or five of which would have easily qualified for state citations. It was obvious why biologists had recommended the season in order to crop the deer herd.

Now, only minutes into the season, isolated shots drifted down the river valley. For a veteran hunter accustomed to hearing volleys of two to four shots, it would have seemed like a relatively serene opener.

By 9 a.m., Don Sundell, an 18-year-old hunter from Blair, was out of the timber with his buck. His hunting savvy exceeded his relatively few years.

"I figured that the other hunters would be moving the deer around," he said, "so I took a stand at the narrowest part of a big band of timber. Any deer moving through those trees had to pass within range. Before light there were deer moving within 50 to 80 yards of me. A little before eight o'clock I saw a buck and three does walking toward me, looking back like hunters were moving them. At 80 yards I dropped the buck with a shoulder shot. He never got up. About 15 minutes later a group of hunters came from the same direction."

Sundell was probably one of few hunters who had previously taken deer with a muzzle-loader. In 1975 he had killed a small buck during the regular firearm season, and

For five days last December, trophy deer at DeSoto National Wildlife Refuge east of Blair were fair game for 100 hunters using muzzle-loading rifles. No season had been held on the refuge since 1969 and as expected, there were many hat-rack bucks 24 NEBRASKAIand

over the years he has taken three deer, all does, with bow and arrow. Both forms of hunting require close shots—a skill few center-fire hunters develop.

By noon, five or six bucks were checked in at the headquarters and about as many does. All hunters reported seeing good numbers of deer. For many, the real test was in convincing their temperamental weapons to fire when they pulled the trigger. Misfires seemed to be a common malady of the muzzle-loaders. For other hunters, the test was in passing up small bucks or does in favor of one of the big bucks that everyone knew were on the refuge. Dennis Carton of Fairbury was one hunter who did.

"I sat on the edge of the timber where I had a good view of an open area for the first couple of hours/' he told me. "I probably saw a dozen does and one buck. I took a shot at the buck but missed. By then I figured the deer had moved back into heavy timber, so I picked a place that offered clear shots in several directions and got comfortable. A doe and yearling fawn came within 15 yards of me, walked out another 10 yards and actually bedded down, looking back along their trail occasionally. I was hoping a buck would foliow, but I knew they could just be watching out for a hunter who might have moved them."

"Six does then came by on the other side of me, and the doe and yearling got up and followed. It seemed like the deer were moving on both sides of me. I thought I might be too far from either trail for a clear shot, so

I moved half the distance to the one that had the heaviest use. Only minutes later I caught a glimpse of horns moving toward me through the heavy timber. By the time I cocked the ears back on my Hawken .50 caliber, he stepped out from behind a tree. I shot. It was about 50 yards, and he veered off his route and ran out of sight, not showing any sign of being hit. I reloaded and started to trail him. In less than 30 yards I found him with my slug in the shoulder/'

The toughest part of Garton's hunt was dragging the heavy-bodied whitetail the 250 yards through tangled timber, and another 350 yards across a disked field.

The sun had hardly burned its way through the river bottom mist Sunday morning before a fast-moving front engulfed the refuge. Saturday had been unseasonable, with temperatures in the 50's and a clear, windless sky. Thirty-five of the 88 hunters who had showed up on opening day had already filled their permits. Forty-five muzzle-loaders checked in to hunt on Sunday. By the end of that wind-whipped day, only 14 hunters had taken deer. The weather remainded cold and overcast on Monday and Tuesday, but 22 hunters returned. Only two whitetails were checked in each day. On the final day of the season, 19 hunters killed three deer.

In all, 91 licensed hunters took 56 deer for a 62 percent success. Many hunters had passed up does and small bucks or the percentage would undoubtedly have been higher. Of the 33 bucks checked in, 22 were 2 1/2 years or older, and several tipped the scales over 200 pounds field-dressed. Contrary to what might have been expected, the crippling loss with the short-ranged, lowpowered muzzle-loaders was significantly less than during a previous high-powered rifle season.

A second special muzzle-loader season is slated for this December to further bring the deer herd in balance with the area's habitat. Because of the small area and the controlled hunting conditions, it was an unusual opportunity for state and federal biologists to study the use of hunting as a wildlife management tool. In addition to providing a chance for hunters to turn back the clock and stalk the woods as their predecessors had some 200 years ago, the special season proved an efficient and desirable means of maintaining a wild game population at a level in balance with its environment, and below a level where crowding weakens and renders it vulnerable to disease die-offs.

A RETURN TO DESOTO BEND

After 13 years I return to federal area in quest of deer—via percussion

IT WAS EERIE. During many years of hunting, I have never ceased to marvel at the wonders of dawn crawling over an unspoiled country. To me it has always been a most special time of the day, as the diurnal creatures awaken and those that are active during the dark hours move back into cover, retreating from the light and the dangers that it can bring.

It was December 18,1976. Unlike the cold, snowy and dreary days customary for that time of the year, the morning had temperatures in the 20's and the forecast was for a cloudless, windless day in the mid 60's. Only a trace of snow remained in sheltered areas.

As the first light began filtering through the dense canopy overhead, vaguely familiar landmarks materialized. It was as if I had been here at an earlier time. Indeed I had; 13 years earlier, when I had hunted the identical spot with my brother, father-in-law and a neighbor; a hunt I described in an article called "Gentlemen's Agreement" for the October, 1964 issue of NEBRASKAIand.

But this hunt was to be entirely different. Instead of the trim, scope-sighted rifle which usually accompanies me on big-game hunts, I had an iron-sighted muzzle-loader, a Hawken in .50 caliber. The rifle was the end product of a replica kit I had assembled during many evenings over the previous months. Loaded with a 370-grain conical lead slug propelled by Pyrodex powder, the traveling time up to about 100 yards was similar to that of a .22 long rifle cartridge. Hardly a long-range weapon.

The hunt was a special five-day deer season being held on the 3,200-acre DeSoto National Wildlife Refuge, located about 25 miles north of Omaha. A total of 100 either-sex permits had been issued, the object being to crop back the deer herd. This was to be a quality hunt, with all hunters restricted to muzzle-loaders. The last hunt on the DeSoto Bend area was in 1969, so chances of taking a big, trophy buck were good. My companions and I were in accord that none of us were in a hurry to fill our coveted permits with anything other than a trophy.

With me were my son Bill, 19, a student at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, and his frequent hunting companion, Jack Santee, 18, also of Omaha, jack works in Omaha as a warehouseman. I'm 43 and live in Omaha where I work as a mortgage lending officer. I was born and grew up in Missouri Valley, Iowa, located just five miles east of where we would be hunting at DeSoto Bend. I have been an enthusiastic hunter since I was a boy, and have taken deer, elk, antelope, bear and small game in several western states and British Columbia. I consider myself fortunate to have four listings—three pronghorns and a whitetail—in Nebraska's record book.

We had left Omaha that morning in two vehicles; a bit of good fortune as things turned out. Halfway to the Bend my station wagon suffered a ruptured radiator hose. We abandoned that ship and proceeded in Jack's pickup. I hoped that the car trouble was not an omen.

Our delay was only short, and we joined the other hunters for a well-prepared and thorough orientation and permit check by refuge personnel. Then, from one of the designated parking areas we set out on foot, guided by flashlights for an area I recalled from my hunt there over a dozen years before.

Members of our party had agreed to still-hunt until mid morning, figuring other hunters would keep the deer moving. The sweeping beams of our flashlights revealed numerous deer tracks etched in the remaining skifs of snow. We tried to select our stations about 200 yards apart overlooking likely crossing areas.

My fascination with the eerie, pre-dawn woods was cut short by the unmistakable sounds of deer moving through underbrush. Only minutes before I had waited impatiently as the second hand on my watch crawled around the dial until at long last, the legal shooting time of 7:17 a.m. had arrived. I slowly pivoted around to face the noise and waited. A sleek coyote trotted to the edge of the clearing before me. Coyotes turned out to be overly abundant on the refuge, but deer were the only legal game. The coyote must have sensed something amiss, as he changed direction and trotted off into the rather dense undergrowth.

The first distant reports of the black-powder weaponry did not shatter the calm until about 10 minutes after the season's opening. Even (Continued on page 45)

30 NEBRASKAlandBACK-COUNTRY BUCK

First-time hunt in Nebraska and first time in Sandhills, a conservationist finds success, wild beauty

THERE WAS A TIME when only a brazen fool would attempt to stroll around in Nebraska's Sandhills without a line tied to something familiar that could be followed back out. Fortunately, that time has passed, and it is now relatively safe for most folks to wander the hills. Even if lost now, a day or two of walking should turn up a highway or ranch house.

Much the same aura still hangs over the hills now, though. Depending upon the season and the weather, the hills can be mysterious, lonely, desolate, gruelling or exhilarating. One's attitude will usually depend upon the nature of the visit and the nature of the person.

During the 1976 firearm deer season, as in several previous seasons, I was wandering around the Nebraska Sandhills. I was hunting with Neal Jennings, a Nebraska State Forester with the University of Nebraska. One doesn't hurry when deer hunting, and a leisurely pace makes it much more pleasant to traverse the hills. You don't have to feel guilty about stopping often to rest; you justify the stops as being on the lookout for deer, but it is also to admire the rolling hills ahead. When deer are spotted, they are usually, a half-mile off or so, but occasionally some are jumped just yards away. Those are special events, as being close to deer and watching their reactions and movements is exciting and fun.

Having hunted several areas of the Sandhills over the years, my opinions about the hills have changed. While people's "first impressions" are important, they are almost certain to be wrong about the hills. They are not barren, or desolate, or devoid of life. Actually, the wildlife is varied and much more numerous than one would suspect.

Grouse are associated with the hills, but there are pockets of good pheasant hunting, as well. Even deer are becoming mixed, as whitetails are found in greater numbers in nearly all areas, supplanting the mulie to some extent even in territory that would seem hostile to them. Hunters have grown to associate trees with whitetails, and it seems incongruous to find them running even in totally treeless expanses of sand dunes.

There are meadows and woods in some areas, too. Wherever water appears at the surface, vegetation is sure to be there, and wildlife will also find it.

And, if there are deer hanging around the cover, hunters will find it, too. There are few kinds of hunting more gruelling than walking deer out of tall marsh growth, though. It may be a mixture of reeds and weeds, but if the ground and water are not frozen, it is tough going. The deer won't come out unless stepped on, and a hunter can't step on them without walking it.

Before Neal and I got desperate enough to stomp through the tall, dense brush around the lake, we elected to have a go at the hills first. We had made three or four undulating strolls, at no time being in any danger of becoming lost, when we ran into a couple of people in the valley who were also between hunts. They, however, had been pushing out the dense lake cover, and were barely able to carry on a conversation in their somewhat breathless condition. After we had drawn close to them, we discovered that one of the hardy hunters was Connie Bowen, well known to us because of her position as executive director of the Nebraska chapter of the National Wildlife Federation. (Continued on page 48)

NOVEMBER 1977 31

LOOK TO THE HILLS

EVERY BIG GAME hunter has dreamed of that big buck. A trophy that is larger than any he has seen before. And in those dreams he always knows just what to do—the right moment to move and the exact location for the perfect shot. It's happened so many times in your dreams, there's no way it could happen differently. Well, if you believe that, you really are a dreamer!

In 1975, my brother Wayne and I decided to change our usual tactics and take a full week to trophy hunt. When we were students at the University, we had never been able to spare more than a couple of days, and then it was over a weekend. In the back of our minds we knew that a full week in the Sandhills would not only give us more time to enjoy the hunt and the country, but just might give us a chance for the trophy bucks that had eluded us in years past. But, neither of us realized just how memorable a deer season it would be.

The first Saturday of the season was calm and overcast. We were on familiar terrain, hunting the same canyon country east of Valentine that we have hunted for the past several years. As dawn spread over the eastern sky, only the barking of a pack of coyotes broke the silence.

By the time we reached our stands, it was light enough to see across the canyon. Nothing was moving. The chatter of magpies picked up where the coyotes left off. In past years we had seen several does or even a buck moving along the canyon floor by that time. But today there was nothing—not even a squirrel in the trees or a brief glimpse of a deer moving stealthily through the oak and cedar trees.

The temptation to get down and move around increased each minute, but we stuck it out on the stands until almost 9 a.m. It was not a typical opening morning for us. Neither of us had seen a deer. We were discouraged but knew we had plenty of time to hunt this year. Back at camp we laid new strategy for the remainder of the day.

During a candy bar and drink of water, we decided to still hunt the north rim of the canyon. If the deer wouldn't come to us, we would go to them. Our previous hunts had taught us that deer are usually where you least expect them. The books tell you to look for whitetails in the brush and wooded areas no more than a mile from where they were born. But we've found them

32 NEBRASKAlandin an area where the tallest thing within five miles was a soapweed. Just because they weren't where we expected them to be didn't mean they weren't nearby.

Wayne worked his way quietly along the edge of the canyon while I walked the hills parallel to him. About a mile down the canyon, Wayne had just come to a flat area about 20 yards from the edge of the rim when 100 yards ahead a huge muley buck and doe walked out into the open. Wayne froze. The deer loped to the top of a small knoll and then the buck, with his rack silouhetted against the gray sky, looked back, just as we had both imagined in our dreams. He seemed completely unaware that we were near, and instead seemed interested in the doe that accompanied him. As slowly as his adrenalin-charged body allowed, Wayne eased his rifle to his shoulder and squeezed off one round from his .308. The buck crumbled. That muley was the largest buck Wayne had ever taken and would be a trophy in anyone's book.

Wayne's permit was filled, but he insisted on going out with me the next three days, retiring his rifle to a comfortable corner in camp. We kept seeing deer, including some nice bucks, but I had set my mind on a trophy and was determined to wait. Someone had told me once that the only place to take a real trophy mule deer buck was in Wyoming. Well, I knew Nebraska had more than a few left. I knew they were here. It was just a matter of finding them.

On Tuesday afternoon, Joe Kreycik, an old hunting partner and friend, mentioned that he had seen several large bucks farther out in the hills, away from the river. Usually we hunt the timbered cuts that finger off the Niobrara. The open sandhills seemed like too much to take on walking, but we decided to give it a try.

By the time we reached the area it was late afternoon. I started working to the east, perhaps subconsciously to place the sun at my advantage. The wind was blowing hard. It was cold and looked as if a snowstorm were on the way. It just wasn't the kind of day I had pictured in my dreams to kill a trophy deer. I knew no self-respecting buck would be out of cover on such a day; it just wasn't supposed to be that way. But, just as I crested a hill, there he was.

The buck and five does stood on an isolated knoll about 500 yards ahead of us. He was easy to spot in the group, appearing twice as large as the does. His rack was high, well beyond his ear tips, and the black brow patch was prominent. The scene was almost eerie.

It was odd that he had chosen to stand on a knob so isolated, with no visible cover in any direction. It seemed as if he had no route of escape unless the earth could somehow swallow him up. But the day was getting short and I had to get closer in the 20 minutes of daylight that remained.

The buck seemed to sense that Wayne and I were there. He stood like a sentry, watching for danger as his does browsed. As if by command, the does began walking slowly but purposefully around the hill. With his head erect, the buck followed, pausing several times to look over his shoulder in our direction.

After he passed behind the hill I ran as fast as I could, keeping the ridge between us. I knew that when I eased over the top he would be standing just on the other side. At his slow pace he could not be farther than 200 yards away; an easy shot, even for a hunter breathing hard. But he wasn't there. I could see for almost a mile in any direction, but he just wasn't there. Indeed, it was as if the earth had swallowed them up.

It was nearly the end of shooting time. As difficult as it was to leave, we decided our best chance was to backtrack and return in the morning. Somehow, I had a feeling I would see that buck again.

Morning dawned cloudy and windy after a nearly sleepless night. This morning would be different than the ones before it—today I was not hunting for just any deer, but "the" buck. Now, each time I circled a hill it was with great expectation rather than merely cautious observation. It was as if this were the first day of the season and all those other days had never existed. Somehow I drew on new strength and a reserve of hope.

Joe suggested that we start the hunt about two miles east of the knob where we had seen the buck the night before. He said that in his experience, a muley would cut country for about two miles after being disturbed. There was still a hard wind when we started. We only saw the sun for short periods when it burned through the overcast skies. The same (Continued on page 47)

33 NOVEMBER 1977

A DEER EXPERIMENT ENDS

Whitetails seemed to be driving mulies out, and special seasons were tried But, they now seem stabilizedNEBRASKANS ARE fortunate in having two species of native deer to hunt—the white-tailed and the mule deer. Currently, on a general area basis, whitetails are the predominant species roughly east of the Cherry- Keya Paha county line on the north, to the Furnas-Harlan line on the south. However, even in far northwest Sioux County, whitetails are the major species on parts of some stream courses.

Deer were nearly eliminated in Nebraska by the turn of the 20th Century, and hunting them was prohibited from 1907 through 1944. Following a population buildup, seasons were then held on an annual basis since 1949, and the open area was gradually extended from west to east until the entire state was open by 1961.

Proportionate species harvest can best be judged by considering only bucks, since regulations for the taking of antlerless deer have varied considerably over the years. In 1961, the buck harvest consisted of 27 percent whitetails. By 1971, whitetail harvest ex- ceeded that of mule deer, and by 1976 whitetails comprised 55 percent of the total deer kill. Actually, over 12,000 square miles of Nebraska (16 percent of the state area) shifted from predominantly mule deer to predominantly whitetails between 1961 and 1968. On a county-wide basis, there has been very little shift in the predominate species since that time. During the quite remarkable shift in populations, hunters and game managers became concerned about the ultimate fate of the state's mule deer.

The primary reasons for the changes in species composition are differential productivity and vulnerability to hunting. The majority of whitetails breed as fawns, whereas mule deer seldom do. Yearling whitetails are also considerably more productive than mule deer of the same age, while in older deer there is only a minor difference between species in the number of fawns produced. For all age groups combined, however, whitetail does produce an average of about 40 percent more young than an equal number of mule deer.

Nearly everyone who has hunted both species can attest to the differences in behavior and habitat which make mule deer easier to bag. When moved by hunters, whitetails usually provide only a fleeting glimpse, whereas mule deer often stop for a second look at their back trail. In studies conducted in the Sandhills, the number of mule deer bagged the first year after being tagged was three times greater than for whitetails. This seems to indicate that they are less wary. Probably the difference in vulnerability to hunting is not as great in areas with better cover, but there is still a difference.

In 1971, in an attempt to increase harvest of whitetails and slow the decline of mule deer, an experimental species hunt was initiated in the Keya Paha Unit. This continued through 1976. During the first three years, from 30 to 50 percent of deer hunters in that unit could take any whitetail, or a mule deer buck, while the rest of the hunters were restricted to antlered deer only. From 1974 through 1976, all hunters could take any whitetail, or mule deer bucks. With the killing of mule deer does thus prohibited by regulation, an increase in mule deer should have occurred, and whitetails should have decreased or stabilized in number. And, if the species regulations were effective, the proportion of mule bucks in the harvest of antlered deer should have increased. This just did not happen.

In 1970, prior to the first species regulation, mule deer comprised 37 percent of the buck harvest. They decreased to 29 percent in 1972; and during the past four years they have been nearly stable at 32 or 33 percent. Obviously, herd composition has not changed in the direction intended, and the selective season was not successful.

It could be argued that without the restriction, mule deer may have been reduced even further. But, data from adjoining units indicates otherwise. In the Calamus Unit, for example (or combined Calamus East-Calamus West from 1974-76), mule deer comprised 35 percent of the buck harvest in 1970, and 37 percent in 1976. Comparable figures in the Sandhills Unit were 62 and 63 percent for 1970 and 1976 respectively. It appears that we are approaching a near balance in species composition, and in these areas, at least, changes in the near future should be relatively minor.

There can be little doubt that the species-regulation hunting in the Keya Paha Unit was not effective. Why not? One explanation is an illegal kill of mule does—resulting because a sufficient number of hunters did not take the necessary time to identify, or were unable to identify, the species they shot at. For those who brought illegal mule does to check stations, this was obvious. During the first season in 1971, based on hunter reporting of dead deer that they found abandoned or lost, the number of mule does killed was as great as would have occurred without the species regulation. In several later years, the number of deer reported dropped off dramatically—so much that credibility was lost and reports served no value. It is doubtful that crippling loss could have declined so drastically—only the reports declined.

Because of the inablity to show nay benefit form species hunt, this feature was elimated from the Keya Paha Unit for 1977. There is no reason to expect that it willl be used elsewhere in Nebraska.

It now appearsthat the mule deer is not destined to be eliminated from vast sections of Nebraska. Quite probably whitetails will increase in some areas, particularly in the Pine Ridge, but mule deer will certainly remain an important species for both observer and hunter in the western half of Nebraska.

NOVEMBER 1977 35

A JERKY FOR ALL SEASONS

AMONG ALL THE OTHER clutter, a glass jar stands on my desk in the offices of NEBRASKAIand Magazine. Sometimes the jar is full to the brim of little strips of dark, almost black material. But, not for long. Let me be absent for a while-like maybe fifteen minutes—and on my return the material in the jar has diminished appreciably. The terrible untrackable Jerky Raider has struck again!

Now, jerky is nothing more than raw, red, lean meat with its moisture content removed by one method or another. The fact that the meat is still raw is disguised by its appearance, which resembles a strip cut from an old, workstained boot which has been watersoaked and dried out repeatedly. Masticating a piece of it only reinforces this resemblance. It takes good teeth to chew jerky. Yet, the taste of jerky has created countless addicts, and the Jerky Raider is one of the worst. In order to rescue him from a life of crime in the satisfying of his craving, and at the same time alleviate my reactive symptoms when I reach for the jar and find it empty, I'm willing to pass along my methods of creating this delectable tidbit

Deer, elk, bison, antelope or the domestic cow all contribute the basic flesh from which jerky can be created, and it matters little what part of the animal is used, as long as it is raw and red. If you butcher one of the animals with the sole purpose of making jerky from it, the bundles of muscles should be pulled apart one by one, using the knife only to help separate the more stubborn tissues. These bundles are then skinned of any tough tissues, and all fat should be removed.

Most likely, wild meat may not be available, and of course it's best to experiment with smaller quantities anyway. I make small batches of jerky from domestic beef obtained frorh the supermarket. My favorite cut is the brisket, since it is long grained and makes up into an excellent "chewable". But supermarket butchers have the habit of displaying only the lean side of this cut, and the blind side is always a thick layer of fat—sometimes as much as a third of the weight of the total package. All that fat must be trimmed off and discarded. While a speck of fat here and there contributes to the flavor of jerky, the oils soon become rancid unless the jerky is constantly refrigerated. So, if you also decide

36to use a brisket, have the butcher give it a close trim before you carry it home. Though more expensive than brisket, a large, lean rump roast or thick round can be substituted.

Throw the dissected game animal or beef chunk into the freezer compartment until it begins to "firm up". With a very sharp knife, slice the meat into strips a quarter of an inch thick, always cutting with the grain of the meat, and not across it as you would if you were converting it into a steak or a roast This cutting up is the most tedious part of the entire process of converting plain meat into jerky.

Seasoning the jerky has been an ongoing argument as varied as the jerky makers themselves. Some say salt it Others say salt is an abomination. In the old days, using no salt made sense since salt attracts atmospheric moisture and mold could form. Personally, I prefer to flavor my jerky nowadays with a thick dusting of Lawry's Seasoned Salt on both sides of the strips, then fortifying them with a light dusting of Lawry's Seasoned Pepper on one side only. Instead of these prepared mixes, you can make up one of your own from scratch. Here is one that I have used:

1 1-lb, 10-oz box table salt 1 tablespoon onion powder (not salt) 1 tablespoon celery powder 1 teaspoon garlic powder 2 tablespoons paprika 4 tablespoons black pepper 2 tablespoons white pepper 2 tablespoons powdered dill weed 3 tablespoons monosodium glutamate 4 tablespoons white sugarMix the ingredients well and let sit for several days to blend. Use a kitchen shaker to apply it to the meat

Two other seasoning treatments work well, too. Dissolve three heaping tablespoons of Morton's Tender Quick in a quart of water. Soak the meat strips in this mixture for an hour. Drain, pat the excess moisture off them, and dust them with a normal amount of black pepper. Using Tender Quick, the meat will retain a reddish color when dried, rather than the darker color of more conventional seasoning processes. The second alternative is:

Dissolve 4 tablespoons of Morton's Sugar Cure, Smoke Flavor, in a quart of water, and use as above. Follow the dusting of pepper with garlic or onion powder.

You can create other seasonings of your own, tailoring them to what appeals to your taster, or chewer.

The meat is now ready for the "jerking" or drying process. As they did in the old days, you could merely hang the strips outdoors on warm, dry, windy days. If you have access to a vegetable or fruit dehydrator with a forced draft, it can be used to dry out the meat. Most likely, though, as I do, you will use the oven of your kitchen range, at least for the first few batches. Coat the oven racks with a little cooking oil, then lay the strips on them, pushing the meat well together but not overlapping. When the racks are loaded is the best time to apply the dry seasonings.

Lay aluminum foil in the bottom of the oven to catch the drips that form as the meat warms. Set the oven temperature at 120 to 130 degrees, no more. As ovens are ventilated anyway, the door need not be left slightly ajar, although this is sometimes recommended to help draw off the moist air. In my oven, it takes about 18 hours to dry the meat. Midway, turn the slices.

At this point, it is not at all out of order to sample one. In fact, if the Jerky Raider could get at it about then, without doubt the end quantity would be considerably reduced. As it is, you might think the cat got into your oven, as you'll be shocked at the amount of shrinkage that takes place. However, meat has a high percentage of moisture, and when that moisture is removed, you will end up with one pound of jerky from each five pounds of fresh meat

When the jerky is almost finished, the strips will be dark, nearly black. If a strip, when broken, displays very little interior moisture, the drying is complete. Cut the chunks into small or desired size pieces with kitchen shears, and pack into jars or plastic bags.

As a snack with your favorite beverage, jerky is unexcelled. Half a dozen strips carried in your shirt pocket while hunting, fishing or hiking, is a nutritious lunch. Broken into small pieces, it will garnish a salad or add zing to dry soup mixes.

Few people need to acquire a taste for jerky, as they're hooked after the first well-chewed bite. I'm thinking of calling a dental inspection in the NEBRASKAIand offices-the Jerky Raider will have the soundest set of teeth in the place.

37 NOVEMBER 1977

Adventures with Whiskers the prairie vole

The Badger Meadow Gang

Ho hum, fiddle-de-dee there's no other place for me. than the grassy shoes of Looking Glass Creek Wild hay to build my woven nest, and seds galore on the downy chess. All my friends are here and about; Old Badger, Bufo, and the Prairie Scout. Oh! Hello up there!SOMETIMES you humans loom so big overhead I completely overlook you. Lie down on your belly in the bluegrass awhile and enjoy this grand November sun. Won't be long and the wind will be howling through the foxtail and bringing snow from the north. I'm prepared, though. Been laying up my stores for the winter. Plenty of time now to enjoy these last warm days of Autumn.

If you'll pardon my saying so, that's a fault peculiar to you humans. You never take the time to sit back and enjoy all the fine things around you. Always in a hurry. Tsk tsk! Hurry here, hurry there. Sometimes

38 NEBRASKAlandI think you're afraid to have any lazy time. Sure, voles work hard too. But when the work is all done we don't go looking for more. Say, how about going for a walk with me? I see you so seldom and you're always in such a hurry, we never get a chance to talk about frivolous things. Why, you don't even know most of my friends!

Careful! You almost stepped on my sunflower seeds. I'm letting them cure out here in the sun a bit before storing them in a safe place underground for the Thanksgiving holiday. That's part of our feast, you know. Something of a tradition with us Nebraska voles. Roasted sunflower seeds, wheatgrass porridge, plums stuffed with wild sage dressing and for dessert, chokecherry pudding. Makes your mouth water, doesn't it?

Step lightly there! I don't want to be cross, but you're going to have to be more careful if you're coming with me. There are a lot of little creatures living down here in the grass. Good, now you're getting on to it. Think of it this way. Your shoe is just about big enough to squash 4,338 baby garden spiders.

Let's walk over to the sandbar. Bufo should be home this time of the year. Once it starts cooling off he doesn't wander far. Who's Bufo! Why, he's my friend the Great Plains Toad. He's quite an amiable old gent. Doesn't have much to say most of the year but I think you'll like him. He lives down here on the creek bend under the willow tree.

NOVEMBER 1977 39

He's a little hard of hearing. Grew up under a river bridge with big cattle trucks roaring overhead all the time. He's a bit on the finicky side, too. That's why he plugs up his doorway when he's home. Has to have the temperature and humidity just so. He doesn't like dry winds, hot days or cold winters. Helloooooo. Are you down there, Bufo? Listen to this. I know how we can get him out. Buzzzzzzzzzzz. Buzzzzz, Buzzzzzzz

Doggone you Whiskers! You play that fly-buzzing-at-my-doorstep game one more time and I'll slip some locoweed into your wheatgrass porridge. Who's your friend with the funny socks? Oh, one of those kids who listens to you chatter in NEBRASKAIand every month, huh? I'd think they would have better things to do than that. Glad to meet you in any case. My name is Bufo, the Great Plains Toad. My great, great, great grandfather, Benjamin Franklin Toad, proposed that we Great Plains toads be your national emblem way back in 1776, you know. One of your silly forefathers thought the bald eagle would be better. How absurd. Just imagine how tasteful a Great Plains Toad like myself, all decked out in my best warts, would have looked on the half dollar. Brrr. It's chilly today. I just hate this time of the year. It's so cold that even the flies aren't buzzing, except for this bewhiskered imposter here. Well, you two be on your way. I'm going underground where any self-respecting, civilized animal should be in November. Nice to make your acquaintance.

I told you Bufo was a bit on the finicky side. Maybe we can visit him again some warm, humid summer evening when he's in a better mood. Let's cross the meadow to the cottonwood grove and see if Prairie Scout is back from lunch. I thought I heard him a minute ago. He's a right jovial fellow; something of a prankster. Talkative, too. Sometimes you think he'll never shut up. There, I see him now. Sounds like he's giving a great horned owl the dickens again.

That a boy, Scouter! Chew him out! Tell that owl to stop flying low over my territory every night. That old Scout, he's a rowdy one. He and all the other crows get together and run every owl out of the country that they can. Sometimes great horned owls take young crows out of the nest at night, so the grown-up crows try to even the score during the day. They just don't know when to stop though; they give those owls the devil year around, even when they aren't bothering the nests. Ohhhh, look at that! They got the owl running now. They're dipping down and hitting him right on the back. Let's hurry over by that fence post; Scouter is coming back and he'll want a place to sit and talk awhile. Hi, Prairie Scout. Meet my friend.

41What a fine day for chasing owls. Hi, Whiskers. Hi, friend. Boy oh boy, did we give that owl a going away party. Oooeee! More fun than raiding a sweet corn patch. And what's new with you two? Doesn't matter. Doesn't matter. Probably the same old stuff. Gather seeds. Eat seeds. Gather seeds. Eat seeds. Gather, eat, gather, eat. What a bore. Let me tell you what has been happening around here. They don't call me the Prairie Scout for nothing.

Well, first they, meaning the friends of your friend there, cut down a whole row of my favorite cottonwoods over in the Old Badger's meadow. My friends from North Dakota are not going to be happy about that. Those trees were their winter roost, not to mention being the homes for 13 squirrels, 28 quail, 6 pheasants, 39 rabbits, 2 brown thrashers, 2 deer, 11 shrews, 9,858,677 lady bugs and thousands and thousands of other little animals that I just don't have time to tell you about. It's not a total loss, though. Just think of the 869 million cornborers and 16,243 cockleburs that will call it home next year. Oh my, oh my. Doesn't matter, doesn't matter. Nothing to be done. Numbers, numbers, numbers. Dollars and cents. Say, what do you think 79 crows are worth? You know what they say: a day without crows is like a day without sunshine. Gotta go, gotta go. Things to be done. Places to see. Here it is halfway through the day and I haven't even flown over the river. Might be owls there. See you guys.

I told you old Scout was a talker. Not much of a conversationalist, though. A bit on the flighty side, you say? Cute. Well, we better go, too. I've got to turn my sunflower seeds. I don't want them to get moldy. Thought we would have time for you to meet Old Badger, but it's too late now. Tell you what: if you want, meet me back here in January and we'll visit his meadow. OK? Well, goodbye for now.

NOVEMBER 1977 41

"Ringnecks"

Limited Edition Prints Available

Here is a full color reproduction offered in a guaranteed limited quantity of 1,000 by Neal R. Anderson, commissioned wildlife artist for NEBRASKAland magazine. Each print is 16 x 20", signed and numbered, with ample mar- gins for matting and framing. $20.00 each. Excellent color reproduction and added realism is achieved by the canvas-embossed paper on which it is printed. All prints are shipped well protected, postage paid. You must be totally satisfied or a full refund will be made. 40% dealer discount upon request.DETOUR FOR DUCKS

(Continued from page 21)geese had been taken by many times that number of hunters in the past few days. With odds like that, it wasn't hard to pass up Plattsmouth when the opportunity for a little river duck hunting came along.