NEBRASKAland

A dove special: outlook-hunting-recipes. Also, a look at Missouri riverboats

September 1977 60 Cents

NEBRASKAland

VOL 55 / NO. 9 / SEPTEMBER 1977

Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Sixty cents per copy. Subscription rates $5 for one year, $9 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAIand, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. commission Chairman: Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-Central District, (308) 745-1694 Vice Chairman: Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 2nd Vice Chairman: William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-Central District, (308) 452-3800 H. B. "Tod" Kuntzelman, North Platte Southwest District, (308) 532-2982 Richard W. Nisley, Roca Southeast District, (402) 782-6850 Robert G. Cunningham, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-5514 Director: Eugene T. Mahoney Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, Jr. Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree staff Chief, Information and Education: W. Rex Amack Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: Jon Farrar, Ken Bouc, Bill McClurg Contributing Editors: Bob Grier, Faye Musil, Roland Hoffmann, Butch Isom Art Director: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1977. An rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliyerable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska Contents A DAY LATE AND A DOVE SHORT 8 SEPTEMBER SEASONS . . . ANTELOPE 12 SEPTEMBER SEASONS . . . GROUSE 16 SEPTEMBER SEASONS . . . DOVES 20 BOATS ON THE FRONTIER 22 WHEN IT'S HUNTIN' TIME 24 EXCHANGE HUNTERS 24 NEBRASKAIand's HUNTING ALMANAC 30 ADVENTURES WITH WHISKERS/OWLS 34 DOVE DELICACIES 40 NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA/WHITE-FRONTED GOOSE 50 DEPARTMENTS SPEAKUP 4 TRADING POST 49 COVER: One of the pleasures of fall is the arrival of hunting seasons, and Mr. and Mrs. Lauren Drees of Lincoln fully enjoyed the final weekend of mourning dove season in October 1976. They are shown here on her parents' farm near Avoca. Photo by Ken Bouc. OPPOSITE: Another pleasure of fall is the arrival of autumn color, and this view of Indian Cave State Park partly captures the beauty of that area, rich in hardwoods and "changeable" foliage. Photo by Jon Farrar. SEPTEMBER 1977 3

World Surplus Center Famous

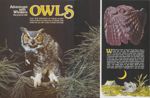

3 to 9X Zoom Riflescope Shpg. wt. 1 '/a lbs. Reg.$31.50Sir / This is a note to tell you how much we really enjoy NEBRASKAIand. I want to especially comment on "Adventures of Whiskers". My daughter is 8 and can't wait to read this section of the magazine every time it comes. She especially liked the killdeer. We have many of them here in S.E. Wyoming.

Have you ever considered publishing these stories in booklet form as a special edition for Christmas? It would not need to be hard back. As a school teacher I can see that they are very adaptable for the class room. I like the clear pictures. Keep up the good work!

Mrs. Lee Scheel Pine Bluff, Wyoming

Possibly the "Whiskers" section will be gathered up for use by teachers eventually, but nothing is in the mill yet. We are delighted that children find them entertaining, and hope they are also learning from the column. (Editor)

Far From HomeSir / We enjoy NEBRASKAIand Magazine very much! The nature photography and short stories are truly superb. I am a native Nebraskan born in Columbus and lived in Lincoln until I was 23. So NEBRASKAIand helps us keep in touch with home though we are half way around the world. Thank you for sending it to us.

Arden Bausch Nes Ammim, Israel

The Real TruthSir / I was more than amused at the answer you gave Mr. Ernst from Duncan Nebraska. He is so right about a shorter season. The people in the Game Commission are always avoiding the real problem like too long a season, not enough men to enforce the law, and a dove season that gives the slobs such a good chance to kill most of the pheasants before the season opens. My land is closed to all hunters until we get this hunting back on a gentleman basis.

L. W. Ockinga Glenvil, Nebraska

Kind WordsSir / For one who lives in another country and another latitude, your excellent magazine has provided many delightful hours of reading and information since my good friend Capt. Steve Davis of Plattsmouth (an ex-wartime colleague) arranged for its transmission to me here in Scotland.

In particular I congratulate you on the special supplement issued to mark Bicentennial Year U.S.A. This was a most graphic and fascinating view of the Cornhusker State.

NEBRASKAIand is very much appreciated by me on three counts. . . Firstly it recalls memories of a visit to Plattsmouth in 1970 and, in particular, to Arbor Lodge just outside Nebraska City; surely one of the most spectacular gardens my wife and I have ever seen (we were there in the fail of 1970).

Secondly your magazine limns the Nebraskan locale of a most interesting book sent to us by Mrs. Mary Lou Davis entitled "Them Was The Days", a saga of the Hawthorne family in their pioneering journey across the state. Thirdly, and this was the primary reason for Steven Davis so kindly arranging for our copies of NEBRASKAIand: your magazine has greatly helped in my senior pupils' projects this year on AMERICA 1776-1976 to mark the bicentennial year of your great country. (Since the War I have become headmaster of a primary school).

Congratulations on the text and illustrations of your magazine and best wishes for continued success through 1977 arid many more years ahead.

J.A. Gillies Glenrothes, Fife Scotland

Bright OutlookSir / In sending in my subscription to NEBRASKAIand magazine I might add that if this coyote hunting isn't stopped there isn't going to be any game to write about. We're about in that spot now. Also, the habitat acres will be worthless.

Homer Houdersheldt Seward, Nebraska

Whenever a practice becomes dangerous or threatening to another, regulations are changed to alleviate the problem. Some coyote hunting practices may be harmful to other resources, but gradually the regulations are being adapted to lessen the impact. Hopefully, your opinion of the habitat plan is in error, for it has become a basic belief that wildlife depends primarily upon adequate habitat. We are merely trying the provide more habitat for them and reduce the impact of society on all wildlife populations. (Editor)

Buggy PoemSir / McClurg and Westerholt teamed up to produce a fine article, "Waste Not, Want Not", in the October 76 issue. It confirmed my belief in these scavenger creatures. The mortician beetle caught my fancy—even inspired in me the following foolish lines:

The Undertakers With beetled brow They dig and plow The earth from 'neath dead mouse. They push it around Into a mound To form a storage house. This way they stash Their treasured cache For future family need. Thus, aged carcass In putrid mass Becomes their babies' feed. So, mouse, beware And do take care— You'll be their next possession. As it proceeds A beadle* leads Your funeral procession! *an official who leads processions. Wanda Benda Shelby, Nebr.

* * *

Cover BoosterSir / I read your article "A Case for Cover" in the January issue. I agree that we need more cover for all wildlife. But, this should be a state-wide project. Landowners simply cannot afford to leave land idle at their own expense.

With the present high prices for pelts, it will be just a short time before our furbearing animals will be on the endangered species list. I think bobcats should be completely protected and restrictions placed on other fur-bearing animals.

I believe the hunting season on pheasants, grouse, and prairie chicken should be closed for one or more years.

Jerome Corbin Arnold, Nebr.

Many efforts are being made to figure out a workable and equitable system for establishing and retaining wildlife habitat, including a cooperative effort with the Natural Resources Districts. It is unrealistic to ask landowners to set aside high-quality land, but often even unused land is burned or bared for no reason. Often, landowners even burn road ditches to prevent snow drifting, when the cover would be better left for wildlike cover. Studies show, by the way, that hunting seasons do not destroy wildlife—it is strictly a matter of having adequate cover to sustain the critters over winter and to hide them from predators. (Editor)

SEPTEMBER 1977 5

See 16 Big Stars and everything under the sun...

Murphy Brothers Mile Long Midway / Sprint Car Racing / Tractor Pulling / Heritage Village / Free Open Air Variety Shows / and More!The Tradiition of Hunting

KEEPING YOUR 4-WHEELER FOUR-WHEELING

A Day Late and A Dove Short

by Ken BoucPlans for an outing on the last

day of the 1976 dove season had

been optimistically hatched a short

time,before in the balmy days of.a lingering warm spell. But, by the time that

Friday had arrived, a high-balling cold

front had about flattened any prospects

for good hunting.

Nevertheless, Lauren Drees and his

wife, Rosann, stepped from their car at

her parents' farm near Avoca fully confident of a pleasant day. Even if the nippy weather had pushed most of the

doves out of the area, there were

prospects of good times between

grandparents and the kids, and a guarantee of a good farm-style meal.

An institutional research analyst for

the University of Nebraska, Lauren

had plenty of experience in the outdoors. He had done a lot of pheasant

hunting and some fishing during his

boyhood near Daykin, and later took

up archery, skeet shooting, SCUBA

diving and some other sports.

prospects of good times between

grandparents and the kids, and a guarantee of a good farm-style meal.

An institutional research analyst for

the University of Nebraska, Lauren

had plenty of experience in the outdoors. He had done a lot of pheasant

hunting and some fishing during his

boyhood near Daykin, and later took

up archery, skeet shooting, SCUBA

diving and some other sports.

In their 10 years of marriage, Rosann had acquired some of his taste for the outdoors. She had just returned from her first big game hunt a few weeks before, where each of them had bagged buck antelope. In fact, the buck she had bagged topped the one hubby brought down, and was good enough to be awaiting the services of a taxidermist.

She had also hunted pheasants and other upland game for a number of years. But, like a lot of Nebraskans, dove hunting was fairly new to her, and she had experienced only a few outings in the two dove seasons Nebraska had offered in recent years.

The weather that day was merely cool by human standards, but to the thin-skinned doves, it must have been the equivalent of a howling blizzard. The sky was empty around the old windmill east of the farmstead, where a week before it had been filled with the gray blur of heavy dove traffic.

Only an occasional dove topped the block of timber beyond the windmill or skirted its edge, and just a handful of birds had been in evidence on the drive to the farm, where hundreds had been just a week before. The birds had apparently been pushed into Kansas, Oklahoma or Texas by the weather front.

The day was perfectly suited to the easy-going nature of dove-hunting. The sun shone brilliantly from a high, clear-blue sky, setting off the brandnew gold of the many locust trees nearby. The northwest breeze had a chill to it in the hilltop farmstead, but the warmth of the sun took over as soon as the hunters moved to the leeward slopes to the south and east. It was the kind of autumn day in which it seems almost a sacrilege to worry or hurry about anything, even something as pleasant as a dove hunt.

Thus, Lauren and Rosann were not too disturbed when the first hour produced little action and nothing for the game bag. Birds were definitely scarce, and any that happened along made it a point to fly high and fast and to be the toughest possible target.

In the long and frequent lulls between birds, it was easy to remember another time on that very spot, just two short weeks previous. I was along on that outing, which had actually begun as a fishing trip to some farm ponds in the area.

Lauren, his father-in-law Harry Jacobson, and I had hung up our fishing rods less than an hour before sunset. Harry volunteered to process the fish, thus allowing Lauren and me to grab our scatterguns and head for the old windmill.

That draw was apparently a dove thoroughfare between feeding and roosting areas. The traffic that evening was almost nonstop, with some birds coming in high, some low, some singly and others in small bunches, some coming from the south or southeast and others from the west.

Lauren had the choice spot, at the edge of the trees near the windmill, while I hunkered under a small tree along a fence. Many of the shots netted nothing more than a little triggerfinger exercise, or perhaps a few fragments of locust bark and leaves. But about every fourth effort brought another dove to the bag.

With perhaps 20 minutes of shooting time remaining, we began to hear a third shotgun join our chorus. It was

10 NEBRASKAland Sudden chill shooed birds away from one-time dove hunting hotspot. But, hunting was good, even without gameRosann and her 20-gauge up on the hill near the farm. From the house, she had seen all the action we were getting and couldn't resist joining us.

Doves continued coming right up until sundown. Lauren specialized in tough snap shooting, picking darting birds from among the treetops as they flew over the timber. Rosann and I got mostly high flyers. When shooting time had ended, the three of us had 21 birds to show for our efforts.

But, all that was a couple of weeks back, and dove hunting fortunes can change dramatically in much less time than that. That same area now held only a smattering of the birds it had treated us to on that earlier outing.

As time passed, Lauren noticed that a bird or two would occasionally show itself above the trees far to the southeast, and one would fly over the southern end of the draw now and then. With eyes turned skyward to search for passing doves, the pair moved slowly down the draw, Rosann covering the edge of the trees and Lauren watching the clearings in the timber.

One dove made the mistake of showing itself in one of the openings, and Lauren's over/under 12-gauge brought the first bird to the bag.

Except for that one bird bagged en route, the move to the south end of the draw was unfruitful. After a 30- minute vigil there produced no more birds, Lauren and Rosann decided to check out another area to the west.

The way over led across an open field which was exposed just a bit to the breeze. That made Rosann's 20- gauge a bit cool to the touch, so she slipped on some light cloth gloves.

That move was to cost her the best chance of the day. About halfway across the field, Lauren spotted about eight doves approaching from the north. But, before they got into range, the birds settled into a little pocket of weeds and grass at the upper end of a waterway.

Rosann was nearest, so she crossed the fence to flush them. "She should have plenty of time to get off the three shots her pumpgun carried, and that should add a dove or two to the take," thought Lauren. But when the birds came up, there was only one shot, a miss, followed by a lot of animated fumbling with the gun.

A bit miffed at herself, Rosann offered an alibi for the blown opportu- nity. The first shot was simply a miss. Everyone misses now and then, particularly on doves.

And, the gloves were to blame for her failure to fire the second and third shots. She couldn't get a good grip on the smooth forend of the pumpgun with the cloth gloves, and all that resulted from her efforts to operate the action was a brisk polishing of its finish.

The third area proved as unproductive as the other two, so, as sundown approached, Lauren decided to move back to where shooting had been so good on earlier hunts—the old windmill.

But it was soon apparent that there was to be no rerun of that earlier hunt. A bird or two crossed the draw far to the south and another slipped by behind the hunters. Then, nothing.

Nothing except a fiery orange sun framing the familiar farmstead a few hundred yards away. Nothing but lacy yellow leaves and wicked thorns of locusts contrasted against the deep blue sky. Nothing but clean cool air and the noise of the countryside preparing for nightfall.

There were no more doves; just memories of another hunt at another time in that spot. The game bag hung limp at day's end, but it didn't seem to matter. It had been the kind of day when hunting was good, even if there was no game.

SEPTEMBER 1977 11

SEPTEMBER SEASONS

What does this year hold? Where are the concentrations and trophy bucks?

ANTELOPETHE TOUGHEST PART of taking a good pronghorn buck in Nebraska is drawing a permit. After that it's all down hill. This year, for example, there were 1,311 applications for the 600 authorized permits in the North Sioux Management Unit. Not all the units were that oversubscribed, of course, and for the first time in years one unit didn't fill on the first go-around. An excess of applications continued to pour in, though, despite regulations excluding hunters who held an antelope permit within the previous three seasons. It is simply a matter of more hunters than Nebraska has pronghorn—a situation that is not likely to improve significantly according to Karl Menzel, big game specialist for the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission.

"I would not look for a significant increase in the number of antelope," Menzel said. "We are at the level that landowners with depredation problems will tolerate. Right now that is the factor limiting further increases. Perhaps some of the large federal areas, like the Oglala National Grasslands, could support more antelope if they didn't spill over onto neighboring private cropland."

During the summer of 1976, just after the fawning season, an aerial survey estimated that Nebraska had about 7,273 antelope in the major Panhandle range. According to Menzel, that is about 10 percent higher than the previous five-year average and about 11 percent below the peak number that Nebraska has had in recent times. This year, 1,715 firearm antelope permits were authorized. Since the first season was held in 1953, 27,359 hunters have harvested 21,997 antelope. Nebraska antelope hunters traditionally enjoy a high success rate, averaging around 80 percent. Last fall the overall success dropped to 73 percent, the lowest in the state's 23 seasons. Adverse weather on opening weekend (when about 80 percent of the successful hunters fill their permits most years), and the prolonged drought over western and north-central Nebraska, have been blamed for the relatively poor success. According to Menzel, an abnormally low harvest in one unit accounted for the low overall kill percentage.

"Last year the Box Butte Unit dropped to a 62 percent harvest,"

Menzel said. "The previous year it had been 79 percent, a more typical figure. About one-fourth of the permits issued in the state are in the Box Butte Unit, so a poor season there has a depressing effect on the overall success. If you excluded Box Butte from the computations, overall success would be only slightly below the average.

"There has been some pronghorn mortality from blue tongue, just 30 or 40 miles across the state line in Wyoming," Menzel continued. "We did not have any losses reported in Nebraska, but it is reasonable to expect that we did, and this could have had some effect on the below average year in the Box Butte unit."

The interstate movement of pronghorn just prior or during the Nebraska season is another factor that can affect hunter success in border units like North Sioux, Box Butte, Banner and Cheyenne. Colorado's season generally coincides with Nebraska's so migration may be nil in that situation. South Dakota's season generally opens after Nebraska's, however, so any movement of antelope is probably out of Nebraska. Opening dates of Wyoming's seasons vary from unit to unit so it is possible that some movement of non-resident pronghorn into Nebraska does occur where their season precedes ours. Range condition is probably a more important factor influencing interstate traffic in antelope, though.

"Normally, Nebraska has slightly better range conditions than the states bordering us on the north and west," Menzel continued, "largely because on the average we receive more rainfall and we have more cropland. With the drought conditions that prevailed here in recent years, it is not unreasonable to suspect that we did not have as many antelope moving into Nebraska from Colorado, Wyoming and South Dakota as might normally be the case. That could have affected hunter success in border units.

Traditionally the North Sioux Management Unit in the northwest corner of the state has the greatest pronghorn density, the most permits and the best hunter success. In 1975, 89 percent of the hunters killed antelope in that unit. Last year, 82 percent filled. One reason that North Sioux hunters enjoy such good success, year in and year out, is the terrain. Antelope are more visible and consequently more vulnerable on the tableland of northwest Nebraska than in the rolling, choppy sandhill country. Antelope density is another factor that makes the North Sioux Unit tops in the state. Box Butte and North Sioux units have roughly the same number of pronghorn, but they are spread over a much larger area in the former. Public land in the North Sioux Unit also improves hunter access and success. The 94,000 acres of prime pronghorn range on the Oglala National Grasslands makes this unit a favorite with hunters.

All of Nebraska's large federal areas are in antelope range. Some are better than others, but the Oglala Grasslands are at the top of the list. Both national forest tracts in the Sandhills are open to antelope hunting, with the McKelvie Forest land south of Nenzel being slightly better than the Bessey Division near Halsey. Game surveys indicate that McKelvie has moderate pronghorn numbers, somewhere between one and two per square mile. The Bessey Division is rated as having a low antelope density, one or less per square mile. Off-the-road travel is permitted on Forest Service land unless otherwise indicated, but hunters would do well to remember that the pursuit of antelope in a motor vehicle is not only a distasteful way to hunt, but an illegal one as well.

Limited antelope hunting is available on the Crescent Lake National Wildlife Refuge between Alliance and Oshkosh. There are not many pronghorn on its 45,000 acres but hunting pressure is low, too. No off-the-road travel is permitted on wildlife refuges. Most antelope hunting necessarily takes place on private land and in general, access is good, especially if advance arrangements are made with a landowner. The chances of turning up a big or trophy buck are better on private land than on the heavily hunted public areas. Few bucks live long enough on the federal areas to sport horns of 14 inches or longer.

According to check station surveys, a higher percentage of older pronghorns come from the Sandhills units. That could be interpreted to mean that the trophy hunter has a better chance of finding taxidermist material in a private-land unit like Garden or Box Butte. According to Game Commission biologists, units like North Sioux, Banner and Cheyenne are cropped too consistently to produce many big bucks. The current state record pronghorn was taken by an archer in Scotts Bluff County. The state firearm record came from Sioux County. That might mean a hunter would have his best chance for a trophy on private land in one of the northwest counties, the state's top antelope range.

A tight permit situation is not a problem for archery antelope hunters. The number of bow permits is unlimited for both residents and non-residents, and a hunter can hold a permit each year. The season is long, generally running some 60 days, and hunters are not restricted to one management unit. But, that is where the archer's advantage ends. It's easy to get a bow permit but darn tough to get an antelope. Last year, 146 bow hunters killed 14 antelope for a 10 percent success. Half of those taken were adult bucks. During the 12 years that an archery season has been held, the bowmen's success has ranged from a low 4 percent to a high of 26 percent. Pronghorns are visible animals, unlike deer, and locating a legal animal is only a short step on the long stalk to a 14 NEBRASKAIand cancelled permit. Long shots are common, though not always necessary for the rifle hunter. The real test of a hunter's skill should be how close he can stalk to his prey before shooting. Shots over 400 yards indicate a lack of respect for the animal, and flock shooting into a herd of running antelope is the reaction of fools.

Making use of hills, draws and cuts in the terrain is the key to narrowing the distance between hunter and game. This is especially true for the bow hunter, who has to cut the range to 60 yards and preferably less. Time and again, the archery hunter is faced with a fine, tantalizing buck standing only 100 yards out with nothing but flat land in between. Some successful bowmen take up stands on alfalfa fields or near water, especially stock dams. Slides under fences can also indicate regular use by a local herd. But more often than not, hunting pronghorn with a bow means one challenging and frustrating stalk after another. Most pronghorn taken by arrow come from the North Sioux Unit where an eroded landscape allows for an out- of-sight approach. Stalking within bow range in the rolling Sandhills is more difficult. Of the 14 antelope taken by archers last year, 12 came from the North Sioux Unit. In 1975, all 7 killed in the state were from North Sioux.

What is the outlook for this year? Aerial surveys were not completed at the time of this writing, but the results probably would not tell hunters anything they didn't already know. There will be a good supply of pronghorn on hand for the opener, and about 80 percent of rifle hunters and 11 percent of bow hunters will cancel their permits. Only a few trophy animals will be reported and probably they will be taken by hunters in Box Butte, Garden or one of the Sandhills management units. More than likely, they'll fall to hunters who knew in advance that there was a big buck in the neighborhood. More than likely, there will be some days hot enough to work up a sweat and, unfortunately, too many well-planned stalks will end prematurely when some inconsiderate four-wheel-drive jockey comes roaring over the hill. The antelope will be there and you can bet that most hunters lucky enough to draw one of these precious permits will be on hand to match wits with one of Nebraska's most sought-after game animal.

SEPTEMBER SEASONS

GROUSENEBRASKA CONTINUES to offer hunting for two species of prairie grouse—sharptaiI and prairie chicken- but the die may already be cast that will eventually change that picture, casting more gloom over bird and hunter.

For a while, the picture may not ap- pear all bad, and some areas may actually be enhanced for the birds. In the long run, however, both these hardy, interesting creatures are going to have additional suffering and hardship heaped upon them.

The 1977 fall season on both species opens September 17, and hunter success may vary widely depending upon summer weather, food and other factors. In most cases, winter was relatively mild and spring fair. A severe hail storm, approximately five miles wide and stretching from Ainsworth to York, is estimated to have done extensive damage to grouse in that huge strip. Hunters are advised to avoid this area. Locally heavy rains could also have had an impact in some regions.

Although press time was too early to take advantage of any of the annual surveys, we did talk with some of the people who know most about grouse to get their opinions.

"I have much admiration for the grouse," said Ken Johnson, chief of the Terrestrial Wildlife Division of the Game and Parks Commission; "probably more than for any other animal or bird. And most of it is because of his ability to survive in his environment. Even when it's 30 degrees below zero, you may find him standing out on an open hillside in apparent ease, or snuggled in a snowbank. They are really tough and resilient birds".

Perhaps no other wildlife has selected, or been pushed to, as demand- ing an existence as the grouse. It is impossible for humans to appreciate the difficulties faced by any wildlife, and especially this feathered hero.

Their existence is marginal even under the best conditions, let alone during extremes such as droughts, heavy rains or the always rigorous winters. Living in the Sandhills where protective cover is at a premium, any extra hardship must certainly be felt by the grouse. Changes in food availability exact a toll; land use changes take a toll; any increase in human population and traffic affect them. Yet, their plight is not taken into account when environmental changes are contemplated, and it is unfortunate.

Nebraska is one of the few states that still has hunting for prairie chicken, said Johnson, and now pivot irrigation systems are proliferating at an astonishing rate, primarily in prairie chicken territory. It is difficult to guess what will happen for certain, but in the long run, the birds have got to suffer.

If agricultural development is scattered, with prairie grass left between plowed fields, the birds would be benefited as they capitalize on such changes; they "follow the plow," an old saying goes. When development exceeds a certain amount, however, their tolerance is overloaded and they are erased from that area.

Ken Robertson, game biologist at Bassett, mentioned the big hail storm as a factor in grouse production. "I never saw the range torn up so badly as by that Memorial Day hail storm," he said. "It just took everything—cattle were taken out of those pastures the next day because nothing was left. It was really tough on waterfowl and birds.

"Other than that," Robertson observed, "range conditions look good- better than for several years."

He pointed out, however, that it will be at least next year before an improvement in nesting cover is reflected in an increased grouse population. Residual cover was sparse this year but spring rains and early warm temperatures were very favorable for good brood and rearing cover. The rains came at about the right time, at least in many areas of the northern Sandhills, and the grasslands improved well into June.

Robertson added that the eastern Sandhills area has lost a lot of grassland to cropland as irrigation in- creases. "In Holt County, for instance," he said, "there is nothing left for birds. Cover has been in such bad shape- down for several years—and now irrigation may be the death knell. Things are better in some areas because of range conditions, but there has been a drastic change over the past 10 years. Some areas, such as around O'Neill and Ewing, went from all grass to all corn on at least half of the 20-mile routes we run every year."

He explained that each year, surveys are run over the same 20-mile routes, and that every five years the routes are "mapped" as to amount of cover, type of vegetation and other data.

The areas which appear to offer the highest densities of prairie chicken this year, with good and bad areas within, include Rock, Garfield, Wheeler, and portions of Holt and Loup counties, plus some sections of Blaine and Brown counties.

For sharptails, the best looking areas are Cherry, Thomas, Blaine, and Hooker counties. Basically, regions for both species remain much the same year after year, with fluctuations depending upon weather and agricultural influences.

As the sharptail is basically a grassland bird, seldom utilizing grain even when available, they have benefited more from this year's weather than have the chickens. Range improvement in the grasslands has been most pronounced, and if another mild winter comes this year, and providing no other factors interfere, there should be an increase in the sharptail population next season. Mild winters and nesting cover are the keys.

To many, the early sacrifice of the bird for the sustenance of the pioneer, the greed of the market hunters and the gluttony of eastern gourmets was a disgraceful display of human contempt. With sensible harvest and concerned agricultural development, the birds could probably have been increased rather than virtually eliminated. Yet, these same human characteristics are still much in evidence today.

As all vegetation but cash crops are ripped out and sprinkler pipes clank together in a seemingly endless network, the grouse stands as a small, helpless shadow in the maze. It is easy to condemn a faceless corporation and accuse it of having no conscience.

GROUSE POPULATION

In April, rural mail carriers make note of prairie grouse along their routes. At the same time, biologists conduct display ground surveys. When compared with data from other years, a population trend is revealed that shows where Nebraska's grouse are, relative to where they've been. Annual fluctuations resulting from the vagaries of weather are to be expected. The effect of a three to four-year drought since 1974, and "good years" of the late 1960's are evident on the graph. The gravest concern is the long-term decline in Nebraska's prairie grouse. Land-use changes-the incursion of intensive agriculture and the more efficient utilization of the range by cattle—is probably the most significant factor contributing to skidding grouse numbers. 18 NEBRASKAlandWhat of the many individual faces that are busily ripping the grouse's very existence away from him? Habitat, including native vegetation and shelterbelts planted at great expense and difficulty by earlier residents, all is being removed for the great provider irrigation. There is little doubt how the grouse will fare, yet most of us are helpless to even slow his eradication. The grouse is lost; at best to be pushed farther north. He is again being literally "plowed under" by man's expansion.

During recent times, grouse hunter harvest has averaged about one bird per man per day. It is estimated that as much as 60 percent of their population going into winter could be harvested without hampering the next year's crop. In Nebraska, it is estimated that no more than 5 percent are harvested by hunters—about 50,000 birds.

Grouse hunting is no easy sport. Considerable walking in rugged terrain is what is usually needed. But, grouse hunting is a challenging and rewarding type of hunting, especially when done the way it should be. The hunter learns a lot during those long hours afield, and comes to appreciate the nature and quality of this admirable adversary.

Overall, the season should end on a pleasanter note than in 1976. Last year the hunter harvest was down in all categories from the year before, so that the 1977 season should look good by comparison.

Perhaps the most likely areas to hunt are the large expanses of federal lands, including the open portion of the Valentine National Wildlife Refuge, the U.S. Forest Service areas at Nenzel and Halsey, and the Crescent Lake National Wildlife Refuge. These areas will offer virtually all sharptails. Most chicken hunting will be on private land, and landowners or friends who offer hunting for prairie chickens on their land should be coveted and treated warmly.

SEPTEMBER SEASONS

DOVETHE MOURNING DOVE is the nation's No. 1 game bird by actual harvest figures, and Nebraska ranks third in total dove population. Until recently, however, Nebraska hunters couldn't enjoy the sporting qualities of this tasty, short-lived, but prolific bird.

This fall, dove hunters will take to the field for the third time in as many years, and early indications are good for production of Nebraska-raised birds at the time of this writing (mid-June).

However, Joe Hyland, the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission's migratory game bird specialist, warns it may be too soon to predict the status of the fall dove population.

It's a little tough to predict what the September population of doves will be this early, as most of the birds haven't been hatched yet," says Hyland. "But, because doves have such a tremendous reproductive capacity, it's probably safe to say that Nebraska populations will be good, barring some unforseen calamity, since they are normally good, year after year.

"We will know a little bit more about populations by the July Central Flyway meeting," he continues. "At that time, representatives of all the states in the flyway and Canada, plus

biologists of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, gather to decide what the status of the populations are and make recommendations to the Central Flyway Council. The Council in turn makes the decisions on the framework of season length and bag limits to be offered to the states."

The mourning dove seems to be one of the few creatures that have adapted well to pressures of civilization. In fact, rather than decreasing in population, they are perhaps as numerous as any time in recent years. The same losses in habitat that have so greatly affected other species of wildlife have not hurt the highly adaptable dove.

The recent drouth was a factor that affected many species of birds. The dove, however, doesn't seem to be affected too much by dry weather, according to Hyland.

"Doves, unlike other upland species of birds, are able to fly some distance to water, and they are highly adaptable when it comes to nesting," he says. "They will nest equally well in the grasslands of the Sandhills, the treetops along the Missouri River, and most places in between."

In nesting, a pair of mourning doves will normally produce a total of three broods per year, with two young per brood. If the nest is broken up by weather or predators, the adults will renest almost immediately.

Mourning doves are short-lived, with over half the year's production being lost to natural causes such as disease and predation. By harvesting a surplus, man may decrease the chance of occurrence of a highly communicable dove disease, trichomoniasis (lesions of the throat). This disease occurs mostly during periods of high concentrations of doves, and is one of nature's methods of taking care of surpluses.

Last year was a good year for both doves and dove hunters in Nebraska, according to Hyland. Production was up from the previous year and the Nebraska harvest was also up slightly from the year before. Again, barring disease or early cold weather, Nebraska hunters can look forward to an excellent dove season.

Doves offer everything that is good about early season hunting. Game is plentiful, weather is agreeable, and the traditional techniques require a minimum investment in time, equipment and physical exertion. About all you need is a place to hunt and some kind of shotgun.

You won't need to use a lot of a farmer's land to hunt doves, something they appreciate at a time when crops are still standing in the field. There's no need to stomp through fields and cover like pheasant hunters do, since the best dove shooting is had by stationary hunters who let the birds come to them.

Three things rule dove activity in any given area—food, water, and a roost. Hunters should keep these in mind when selecting their hunting spot. The birds spend most of the day feeding wherever there are plants that provide the small seeds they favor. Hemp seed is a favorite wild food source for doves, particularly in the east. They also like corn and milo fields that have been cut early for silage, disced wheat stubble, and miscellaneous weed patches.

The birds generally go to water in the morning and again toward eve- ning. That makes a farm pond a good bet in the eastern croplands, and windmills a good choice in ranch country, particularly the first two hours in the morning and the last two before sundown.

Doves generally travel from roost to water to food and back again along rather loosely defined flyways. Usually, 10 minutes of careful observation will indicate where these dove thoroughfares are, and once that is determined, it's just a matter of selecting a good ambush point.

Find a place that offers a good view of dove traffic. You don't need to hide yourself like a deer hunter might, but it's a good idea to be reasonably inconspicuous. Usually, a hunter in drab clothing and sitting against a tree or bush to break his outline is hidden well enough to satisfy doves.

Don't get hunkered down in some kind of thicket or other such blind that will keep you from swinging your shotgun freely when the right time comes. Before game comes along, shoulder your gun and find out just where you can comfortably shoot.

The most important items of the dove hunter's gear are his scattergun and ammunition (many, many shells). Just about any shotgun will do for doves, except for some of the heavy, tightly choked magnums used by some waterfowlers.

A 20-gauge is probably ideal, but a .410 will do the job and a 12-gauge shooting light loads also works nicely. For the 20 and 12, a modified choke is plenty tight, and an improved cylinder boring is probably preferable. Other than a reasonable selection of gauge and choke, the only real important thing about a dove-shootin' iron is that the shooter be comfortable with it and have plenty of confidence in it, for the speedy doves will test that confidence severely.

Ammunition doesn't have to be very potent for doves. Few circumstances would call for anything heavier than No. 7Vi shot, and smaller pellets are usually the norm. Shooters of 12-gauges in particular go to trap loads and other ammunition a little less powerful than what they would shoot at pheasants or ducks.

Nebraskans with a yen to hunt doves should do as much of it as they can as early in the season as possible. Doves are real sissies when it comes to cool weather, and an early fall cold front can run every one of the critters out of the state overnight. But, hunters caught up in the action of Nebraska's excellent dove hunting will greatly enjoy the birds for as long as the weather cooperates.

SEPTEMBER 1977 21

BOATS ON THE FRONTIER

River steamers that stayed afloat made their owners rich

THERE IS RECORDED in Nebraska's antiquity a thrilling steamboat history which, as it captures the imagination, takes its place alongside the riverboat stories of the Hudson, Ohio and Mississippi River valleys. True, the Mississippi handled the biggest share of inland shipping, but upon examination, one discovers Missouri River traffic which is surprising.

James Watt had invented a loud, unwieldly contraption called a steam engine in England in 1769. The British first used it to power looms and "iron horses," and barely thought of using it to power a boat.

But, in 1807, a painter-inventor named Robert Fulton designed and successfully demonstrated the first paddle wheeler for America. He named it the "Clermont". Boat builders soon adopted the idea and built ships propelled by the new steam engine. By 1819, Fulton's own threemasted sidewheeier, the "Savannah," was sturdy enough to cross the Atlantic in 29 days.

The designers also looked to the West. The interior of America was wild, unknown, challenging and gigantic. Intrepid businessmen and explorers soon realized that the best way into this vast wilderness was by water. Shippers didn't have much trouble sending a boat from New Orleans to St. Louis, but when they branched northwest, up the Missouri, they ran into many discouraging problems.

The Missouri was a liquid-mud river "too thick to drink and too thin to plow." The average mud-flow past what is now Omaha was 270,000 tons of silt per day. Its rise and fall were unpredictable and could vary between 13,000 and 800,000 cubic feet per second, depending on wet or dry years.

The valley varied from one to 15 miles wide, was over twice as long as the Mississippi, and dropped 8,000 feet during its first 700 miles. The average depth was only seven to nine feet (Omaha to St. Louis) and the lower valley was extremely flat.

Mud banks were always building up and the channel

22 NEBRASKAlandwas always changing. Snags were ever present. If Indians weren't waiting for you at some bend of the river, there was always danger of fire, especially on the lumber boats. Whisky sank a third of them, and carelessness another third. Even a tornado could be a threat.

There were over 500 recorded Mississippi-Missouri sinkings during the 19th century. Night travel became restricted above St. Joseph except in bright moonlight.

The first steamer to land on Nebraska soil arrived at Manuel Lisa's trading post (near present Hummel Park) seven miles north of present Omaha. That arrival occurred on September 19,1819, nearly 160 years ago, and a mere 12 years after Fulton launched his first steamboat.

The smoke-belching, serpent-like, steam-driven riverboat, the "Western Engineer," carried the 20-member expedition party of Maj. S. H. Long, who later explored the Rockies. It was built in Pittsburgh, sailed down the Ohio River to St. Louis, and finally up the swirling, muddy Missouri. That steamboat was the first ship to land a white man on the west shores of the Missouri.

The second part of the same expedition was that of Gen. Henry Atkinson's Sixth Infantry. The force left Plattsburgh, N.Y., in 1819 boarded three steamers, the "Jefferson," the "Expedition", and the "Johnson" at St. Louis and began a luckless passage up the Missouri. None of the three ships completed the trip.

The first one steamed 150 miles, the second one 350 miles, and the last one came up river 450 miles. Baggage was transferred to smaller boats and the troops strenuously paddled upstream another 250 miles and arrived at Council Bluffs about October 1, 1821.

The third steamboat attempt on the Missouri came in 1831, and it attained great distance. Nebraskans may be surprised to know that 145 years ago, a 144-ton paddle- wheeler named the "Yellowstone" passed all of Nebraska's river towns. The vessel not only traveled 441 miles of Nebraska's shoreline, but also sailed beyond Yankton and Pierre, S.D.

In fact, the "Yellowstone" went clear to Fort Union in Mandan Indian country, 50 miles beyond what is now Bismarck, N.D.! The "Yellowstone" crew explored some 1,200 miles of the Missouri Valley, carrying a load of provisions and returning with a load of furs.

The 2,305-mile journey from St. Louis to Fort Benton was accomplished by the "Chippiwa" in 1860. Four years later the "Luella" left Fort Benton with $1,250,000 worth of gold and 230 passengers. Three years later, 39 gold boats departed Fort Benton.

After 1832, when the river was proved navigable, and especially after the Mormons arrived at Florence in 1846, the steamboat was to have an exciting and lively history.

Riverboat designers continued to build boats especially adapted to the shallow Missouri. They built hundreds of them of all types; some were cheaply built cargo boats while others were floating palaces. The hulls, averaging three to five feet deep, were built long and wide. The engines lay horizontally instead of upright.

The boats used high-pressure engines which were sometimes exposed on deck because of the heat generated. The smoke stacks were very tall so that the sparks would not cause a fire. In spite of their shallow hulls, many of the boats struck Missouri mud bars and mired for days.

More than one boat was abandoned when spring high water deposited them far from the center channel. Because of the rough treatment, average life of a river boat was only about four seasons.

Eventually, river commerce fell into two categories. The first was the "packet lines." They were the short-haul transports which took their time and carried almost anything from race horses to whisky. They carried few passengers since they traveled slow and made many stops.

In 1858 there were 60 regular packets and 30 to 40 "tramps" on the Missouri. Above Omaha, all packets were called mountain boats. They brought back furs and buffalo hides.

Freight rates varied with distance, location, and the time of year. In 1849, 100 pounds of cargo could be carried 1,750 miles to the Yellowstone River for $8. In 1855, 100 pounds could be sent from St. Louis to Omaha, 600 miles away, for $3.

The second category of river commerce, the "transient lines," carried mostly human transport. These boats followed a regular schedule because the passengers were in a hurry to go somewhere. The Missouri was closed above Omaha from November to March.

A non-cabin passenger, sleeping on deck, could go up river for one cent a mile. Thousands of troops on the way to the frontier took the Missouri road to the West.

During the California, Colorado, and Montana gold rushes of 1849, 1959 and 1864, steamboats carried thousands of passengers to Nebraska river towns. Pioneers then took various stages and trails up the Platte Valley from such towns as Nebraska City, Plattsmouth, Omaha and Florence. Others took the California trail from Independence, Mo., to the valley of the Blue River and on to the Platte.

Every type of personality (Continued on page 45)

SEPTEMBER 1977 23

WHEN IT'S HUNTIN TIME

It's a special time, made up of all memories jammed togetherHUNTING IS a quiet dampness on a frosty morning. Hunting is the ease of good companion- ship. Hunting is the familiarity of a good dog. Hunting is a cold walk.

Hunting is something different to every hunter, for each remembers his own experiences when the subject comes up. It's many things, of course; memories from all experiences sort of crammed together.

It's early spring practice for the spring turkey season. It's that feeling you get when that person who taught you, your father or uncle or big brother, finally has the confidence in you to let you hunt alone. And, you walk to the top of a hill or a ridge, in country where you could get lost, but you know you won't. You're alone, and you wonder if that wild turkey will come to the call; if you'll know a gobbler from a hen after all; if you can even hit what you shoot at. Then you start walking the ridge, and it doesn't matter; it will take care of itself in the end.

It's the mistake you made when you followed a ridge that didn't go where you expected and you wound up in a cold, wet, brush-choked bottom where the only way out was fighting the brush and getting wet up to the knees.

But you know where you are, and you know the bottom leads back to camp. And you really don't care anyway because there's all kinds of time. Morning isn't even over yet, and you have jerky and sunflower seeds and other snacks in your pockets. If it takes a week to get back, you'll still get there.

Besides, there are water bugs in the pools, and a vulture soaring over the ridge. Maybe you'll zigzag up and down the canyon wall so you won't miss anything. But then, maybe you won't. You start seeing (Continued on page 28)

EXCHANGE HUNTERS

Many years of hosting each other has firmed a relationship that started as hunt but ended as friends

I LIKED DONALD DUCK when I was a kid," said Dick Himbarger, "and I started by imitating him." From Donald Duck, Dick graduated to wild waterfowl, which he calls with skill that is seldom equaled. Using only his own vocal apparatus, he can turn a fly-by flock into a stop-and-see bunch without any mechanical device whatsoever.

According to hunting companions Ben Meckel and Ed Wence, Himbarger calls in even unreachable ducks. "I can't do Donald anymore, though," Dick confesses. A California state trooper and Tule Lake fishing guide, Himbarger doubles (or triples) as a pilot, as well. His 1976 Nebraska visit took him into the airport at Burwell with Hawaiians Ed G. Wence and his son, Ed W., on a Sunday evening in November.

Wence is a Nebraska pheasant hunting veteran of many seasons. Why hunt Nebraska? 'That big-footed galoot over there," Ed answers briefly, grinning and nodding at Meckel, his host.

The exchange of hospitality between the two hunters seems to be the real reason for yearly hunts, especially since the "Shanghai roosters" weren't being fully cooperative that season. If birds in the bag were the real reason for the visit, it could only be considered a loss. By Tuesday afternoon, only three roosters had succumbed to the six hunters' two-day efforts.

On the other hand, it seemed that all hands had given up worrying about birds in the competition to out-host each other. Meckel, for example, had placed fancy fruit baskets in each of his guests' rooms.

"But that's only in return for the orchids my wife and I found on our pillows when we visited Hawaii," Meckel said.

A game dinner Monday evening was dominated by Hawaiian mountain sheep.

'That's a well-traveled sheep," Wence pointed out. "Ben shot it in Hawaii, then had it shipped back to Burwell. So, I had to come all the way from Hawaii to sample it."

The two-day hunt had been planned as a mixed-bagger with pheasants and ducks as primary targets. A duck blind on a small pond near the North Loup River was the scene for early morning and late afternoon action, while nearby cornfields and marshes provided hunting later in the morning and into the afternoon.

Monday morning started before dawn with Meckel, Bill Manasil, a Burwell businessman, Himbarger, Ken Zimmerman of Loup City, the Game and Parks Commission chairman, and the two Wences in the blind. Himbarger's calling brought in a total of one mallard drake,

which Meckel downed. Himbarger passed up a 70-point hen.

The lack of waterfowl left time, though, for getting reacquainted and exchanging new yarns. It also left time for watching the sunrise touch frosty weed clumps with sparkles of light. Ice crystals formed prisms that touched what would become a mundane noontime landscape with pinpoints of exotic dancing color.

As the little pond picked up the morning's rosy, golden glow, it became a vast mirror, reflecting in sharp detail the scattered decoy set-up in crisp, vibrant color backed by sky blue.

Manasil's young Lab, Nemo, shattered that mirror calm with an impatient attempt to retrieve the decoys. "After all," he seemed to say quizzically when reprimanded, "retrieving's my job, and I haven't done a day's work yet."

By 10 a.m. the crew was ready to give up on waterfowl hunting, with so few birds moving, and turn their attention

instead to pheasant. Several roosters had been crowing invitingly in a nearby cornfield.

Ray Goehring, the landowner from whom Meckel leases hunting land, joined the crew while Manasil slipped off into Burwell to attend to some business. While still forming up for a pass through the corn, the elder Wence was startled by a covey of quail.

Not a shot was fired, much to Himbarger and Zimmerman's amusement. The only detectable reply to their jibes, though, was some disgusted muttering about new shotguns and weird safeties.

A pass through the corn produced no roosters; only the harvest-time scent of dry grain and damp earth, and a chance to warm up from the chill of the blind by walking.

"I think we're evolving a new breed of pheasant," Zimmerman volunteered sagely. "The roosters that have survived hunting from all Nebraska's past seasons have been the sit-tight and double-back kind of birds. They're the ones that breed the following spring and thus they perpetuate their own characteristics."

"Those roosters," he concluded, "are all behind us."

A short conference resulted in the group splitting, with half working north and the others working south between the corn and the river.

There, the men bagged a pair of quail; Himbarger credited with one and the younger Wence dropping the other. The dogs had gone with the other party, so locating the birds proved to be a difficult task, but one that was finally accomplished.

"We put a dollar in the kitty for taking hens," Zimmerman quipped when the two groups of hunters met back at the blind, and everyone looked at Himbarger, whose quail had been a female.

Himbarger and both Wences decided to walk the trees along the river one more time to pick up any singles they might locate. That stroll produced two more quail before lunch, and a comment from Ed W. about ice patterns on the river making beautiful black-and-white photo material.

A leisurely noon break was followed by some hunting on the south side of the North Loup River. There, the party followed the cornpicker. Pheasants were plentiful but flushing wild—or doubling back as Zimmerman had previously noted. Nemo, hunting his first season, was ranging too far ahead of the party while Max, Meckel's veteran Lab, was performing steadily.

A pass through river marshes produced some excitement as young Wence broke through the ice. When the NEBRASKAIand photographer broke through, as well, there were gallery complaints that there's no justice in snapping photos of one person's misfortune while refusing to give up the camera when the situation is reversed.

Though the hunters bagged no birds in the afternoon, the dogs accounted for two. A pair of wounded mallard hens had taken refuge on a little pool of still-open water in the marsh. The Labs located and retrieved them, but only after several minutes of splashing and struggling.

"It's too bad the hunters who wounded those birds didn't have dogs," Zimmerman remarked. 'They sure prevent leaving a lot of cripples in the field."

The party was divided in late afternoon between blind and marsh, but there was no action except one hen mallard that over-flew the marsh without losing even a

single tailfeather.

The second day's hunting began at six with coffee and rolls. Again the party was split between blind and marsh. A lone mallard hen came into the decoys. Meckel's shot wounded her, and produced a problem for the dogs as she submerged in the little pond and hid under a log. Some 15-minutes' search, however, brought her hide-out to light.

Apparently embarrassed by the long search, Nemo again began retrieving decoys.

In the uproar that followed, Dr. Murray Markley of Ord, who had joined the hunt that morning, made a grinning remark to Wence as they both waited in the blind. "You know," he said, "Ben Meckel might just come late for surgery, but I don't expect him to ever be late to go hunting." Before starting again on pheasants, the men gathered for a hearty second breakfast of coffee, hamburgers, apples and rolls. The blind was pressed into

service as kitchen, and the foot-warming catalytic heater as stove.

By afternoon, Nemo was back in the kennel with a bit of experience under his belt, and Max had reinforcements in Stoney, Meckel's younger Lab. The pair worked well together as the afternoon's bag attested. Wence and his safety were apparently getting along better, too, as he bagged one of the three roosters taken that day. Zimmerman scored on a second, but no one could remember for sure who got the third.

That evening, with more waterfowl moving than on the previous day, the men harvested two more ducks; one gadwall and one mallard; both drakes.

"In Hawaii, we have a superstition," said Wence that evening. "We consider it bad luck to give somebody something without getting something in return."

That superstition could keep Meckel and Wence returning to each other's territory year after year to partake of one another's hospitality.

Hunting is decoys on a pond, a squirrel chattering, even a farmer talking about crops, rain and habitat

(Continued from page 24)things you hadn't noticed before. Simple things like the long profile of a pintail; shreds of brush where a deer polished itching antlers; a bared spot where quail dusted themselves.

There's the way some decoys and the clouds are reflected in the frozen mirror of a thin ice film when it's already too late for good hunting, but you'll wait awhile anyway just in case the ducks can't tell time. And that silly pup that got bored with waiting and plunged into the pond to retrieve the decoys.

There's the squeaky call of the whitefront and the lower-pitched honk of Canadas. There's the whistle of a goldeneye's wings.

The way the snow glitters on the curved stems of last year's dried grasses when the sun's just coming up, and there's no way on earth you'd drag yourself out of a warm bed at this ungodly hour-but you're glad you did, even if there isn't a duck flying.

It's hunting ducks for the first time and being too excited to fire a shot into the big flock of mallards that passed right by the blind. It's watching a friend who has hunted many seasons and didn't fire either, but mumbled something about a faulty safety-although it worked perfectly later in the day.

It's knowing that you died and went to heaven when you return to a warm house and dry socks. It's watching a seasoned hunter who said he's going to show the young'uns how to sneak a duck, then gets his coat caught on a door handle and rolls under the van. Good thing he was smart enough to leave his shotgun in the back.

It's watching a friend disappear into a brushpile that he was "rearranging" to help the rabbits find their way out.

Hunting is sitting out a high wind in the lee of an old barn, exchanging stories. "Why, it used to get so windy out here, we were afraid to tie up our horses when we went into the saloon. Wind would blow the dirt right out from under 'em and they'd be hung to death by the time we'd finished our beer."

Hunting is a squirrel, peering around a limb about four feet away, then jerking his tail and chattering at you before he scurries off, leaping from limb to limb with blurring speed.

Hunting is a farmer talking about the crops, and the price of wheat, and wonderin' if it'll ever rain; and you wonder, too, for the land's gettin' dry and people are havin' a hard time, not to mention the animals. It's discussing that brushy old draw that used to hold a couple coveys of quail, but seems like they're scarcer'n hen's teeth now.

Hunting is a good dog, zigzagging ahead of you, nose all business, but coming back to check on you every now and again just to make sure everything's still O.K.

It's the flash of iridescent reds and golds and bronzes when that old rooster that's been running you ragged finally gets up. It's the snap shot that downed him, and feeling proud of a clean kill but a little sad that he isn't goin' to fly anymore. But you know there will be more, if they just have a place to live.

It's hunting pheasants along the edge of a cornfield only to have a covey of quail explode right at your feet, and trying to pick out one of the little brown-and-white whirlwinds to shoot at.

It's sitting around on the back porch, plucking the day's brace of ducks or skinning those pheasants, and hashing over the hunt. "You know, it's gettin' harder and harder to find any quail anymore, and the pheasants seems to have moved back to China. Gettin' harder all the time to find a place to hunt, too. I know all these guys in four counties, but they haven't got anything growing anymore for birds to hide in."

It's the slow realization that you're talking more and more about the good old days and wonderin' about tomorrow.

"Why, when I was a kid, growing up on the farm, we used to walk right outside the house in the spring and listen to bobwhites calling back and forth. We got so we could imitate them pretty good.

"Don't know what happened to that covey of quail. Trees are still there. Bigger, of course. All black in there, even in the daytime. No little brushy seedlings. No edge anymore, just trees and farmyard. That's probably it: need some bushes at the edge of the trees.

"Used to have a little game preserve in the middle pasture. Game Commission helped us plant it. Wild plum and cedar and I don't remember what else. Fence got old, though, and the cattle broke it up pretty bad. No time for replacing fence."

You realize that all the old neighbors used to have shelterbelts, and maybe a few trees along the creek bottoms, and "dirty" fencerows. But there aren't so many neighbors now. Man can't make it on a section of land like he used to—not if he wants his family to have all the latest things. Some of 'em just moved away, or the old folks died and their kids sold out or leased the land. The old houses just fall down, bit by bit, until they're torn down. No more kids to run in and out, slamming doors. Nobody to talk to about hunting the north 40 or the price of wheat. No hunting on the north 40 anyway; no cover.

Shelterbelts make way for wheat or corn. Fencerows come down as fields get bigger. Can't spare the ground for waterways any more. Just let the silt, the topsoil, run down the hills and off into the creeks—those that have any water.

Makes you feel a little sad inside thinkin' what happened to the kids that used to poke around in the trees that dad or granddad labored so hard over, looking for bird nests and squirrel nests, and baby rabbits. But then, whatever happened to those trees?

Nope, things shore aren't like they used to be. You get your shotgun out and shine it up nice, and go out to the old place you used to hunt. Not a tree around anymore.

You go talk to the farmer and you find him in the closed cab of his tractor. He has no idea where the game might be. Doesn't notice it much in his air-conditioned cab. Shakes his head a little sadly. Shore misses the pheasants, but doesn't miss the dust and grit in his eyes and teeth, and the melting down into the tractor seat, and the sore, aching (Continued on page 48)

SEPTEMBER 1977 29

NEBRASKAland's HUNTING ALMANAC

Build a Portable BlindWaterfowl blinds can be as simple or as elaborate as you care to make them; it really doesn't make much difference as long as the blind blends in with the surroundings. A good portable blind can be made with a section of snow fence and a couple of metal rods. Cover the fence with can-vas and chicken wire, or use as is, weaving natural grass, willows or cattails between the wire openings for camouflage. Arrange the fence in a circle around posts and push or drive them into the ground.

Don't Stand in the MudWood pallets make good floors in blinds situated in muddy areas. If the first one sinks into the mud, put another on top. Mud tracked onto the boards can be scraped off into the cracks of the pallet. Used pallets can often be picked up for less than a dollar at lumber yards and warehouses.

Carry Your Seat with YouA handy seat to carry into the blind is a five-gallon drywall bucket with lid, which doubles as a carrying case for shells, lunch, binoculars, raincoat, etc. A good seat cushion that also works as a fanny warmer is one of the commercially made "hot seats" that reflect body heat.

Keep Decoys from TanglingLots of things are used for decoy anchors, but most of them are less than perfect. Those that simply hang loose tend to unwind and tangle up with each other. To remedy this, cut an old bicycle tube into rubber hands about a half-inch wide, and tie onto the cord near the anchor. Then, wind the cord around the decoy's neck and slip the rubber band over the head.

Decoy AnchorsYou can make your own lead anchors that slip over the decoy's head if you have access to a router and a gas stove. Other things you need are an iron kettle, ladle, scrap lead and a hardwood board. Rout out several molds in the board, making sure the loop formed is big enough to go around the decoy head. Then, simply melt lead in the kettle, pour into the mold with the dipper, let cool until lead hardens, remove the anchors, and repeat process. If you do this indoors, have plenty of ventilation as lead fumes are toxic.

Keep Records for Future UseSome hunters keep a record of duck hunting days afield including species bagged, type of day it was, temperature, numbers seen, etc. Most peak waterfowl migrations will occur within the same one or two-week period, year after year, and good records help determine patterns of migrations in your area.

DECOY BAGSMake your own carrying bags for decoys out of big burlap bags. Use two bags and tie them together with a piece of rope. Throw the rope over your shoulder and carry them with one bag in front and one in back, leaving both hands free to carry other things.

PICKING DUCKSIf you pick your ducks, it is much easier done when they are still warm. Take along a plastic trash bag and dry pick them. This makes the cleaning chore a lot easier than when you get home, and helps pass the time while waiting for another flight of birds. Don't forget to leave the head and one wing on the birds for identification as required by law.

Build a Blind for UtilityDon't overlook a few basic items that may make the hunt more enjoyable, when building a semi-permanent duck blind. Some kind of shelf in front is a handy place to put extra shells and other things to keep them dry. A rack for guns keeps them from falling over, getting scratched in the process, and is an added safety factor. A few strategically placed nails can be used to hang calls, binoculars and extra clothing.

When hunting diving ducks around lakes and reservoirs, watch their patterns of feeding and flight, then set up accordingly. Once you find a feeding 30 NEBRASKAIand area, you can chase them off and they will often come back. Divers tend to fly along shorelines, often within gun range.

MAKE CHEAP DIVER DECOYSDivers aren't as spooky about decoys as puddle ducks, and often you can get by with flat-black-painted decoys or plastic jugs strung out in a line. Divers usually come into your decoys the first pass or go on by, as they rarely circle. Duck identification is important here, as you have to take them the first time and seldom get a second chance.

In hunting divers, and even puddle ducks, you often don't need a blind if you can keep still. The secret is to blend in with the surroundings and not move. The slightest movement of a hand, gun barrel or upturned face is often enough to send a flock into orbit. Always wear a cap with a bill on it and keep your face covered. Watch the birds out of the corner of your eye.

If you are having trouble retrieving ducks that fall in deep water or on weak ice, and you don't have a boat or dog, take along a fishing outfit and a heavy lure next time, and try to snag it. You might find out whether your casting ability is as good as you think it is.

When hunting mallards from a sandbar, try a dozen or so field mallard decoys on the bar close to your floating set. These are usually bigger than floaters and are much easier to see from a distance. In setting out decoys, try to leave an opening, large enough for a big flock to land, directly in front of the blind. Ducks like company, but they don't like to land close to other birds and will leave or land outside the decoys if there isn't enough room inside.

Take Along Some Extra ClothesAn extra set of hunting clothes left in your car might just save the day if you happen to step in a hole and "take water" in your waders. A large plastic trash bag could help you stay dry if you get out to the blind and find that you have a leak in one of your waders. Take the boot off and slip your foot into the bag, then put the boot back on.

Pick-up Your TrashIf ducks are interested but flare off too soon, check the area around your blind. Anything that looks out of place can spook waterfowl. It's a good idea to periodically gather up empty shell cases and any paper or other trash, and when you leave the blind, take it with you.

When you are hunting early season game such as squirrel, dove and grouse, take along a cooler with ice and field dress game as soon as possible. A plastic jug of water and some rags come in handy to clean up with afterwards. If you prefer to hunt the lazy man's way and sit and wait for either squirrels or doves, then take along a five- gallon bucket to use as a seat and game cooler. Just stick a styrofoam minnow bucket inside, add some ice, and you can cool your game immediately.

If you drop a bird in heavy cover, immediately walk to where you think it fell. If it isn't there, place a hankerchief or your hat or something at the spot, then search the area around the marker in an ever-widening circle. Look for loose feathers, then search up-wind from them. Generally, wounded grouse, doves and quail will try to hide rather than run, while pheasants will usually do the opposite. If you have a dog, let him check the area out before you move in and confuse him with your scent.

If you don't have a dog, quail can sometimes be hard to find. Generally, you'll find them along the edges of corn or milo, and fairly close to plum thickets or stands of dense timber.

SEPTEMBER 1977 31

The time of day is often important, and you'll generally have an easier time finding them during the mid- day hours after they feed. If you scat- ter a covey and lose sight of the sin- gles, wait several minutes and listen for them to start calling as they regroup.

Bug RepellentSeptember weather can get pretty warm and gnats can drive you batty if you forget to bring bug dope. If you can't find any in the local stores, try some vanilla extract, available at any grocery store. It works.

If you are going to do a lot of walk- ing early in the season, don't wear wa- terproof hunting boots as your feet will perspire heavily and blisters could re- sult. It's also a good idea to take along an extra pair of dry socks and change them at lunch time.

Cactus RemedyTake along a pair of long-nose pliers next time you take your dog afield in grouse country. A nose or paw full of cactus spines can turn the best dog into a limping liability and the pliers will prove useful in pulling out the spines.

DOVE HUNT EARLY FOR DOVEDoves are early migrants out of the state, often leaving in late August and early September. Plan your dove hunts accordingly, as a cold front will often push most birds out of an area. Look for more birds to follow, however, as those from the north come through.

Check Crops for FoodIf you are having a hard time finding doves but you know there are some around, then check the bird's crop when you finally get one. With a little practice you 11 be able to find out where and on what they are feeding. Common foods used are hemp, wheat, corn, and foxtail

Pass Shooting DovesOne of the more productive and sporting methods of hunting doves is by pass shooting them as they go from feeding and watering areas to the roost. Try not to hunt too close to the roost, however, as you might drive the birds out of the area. For the same reason, don't hunt one area exclusively. Try an area for a few days, then give it a rest and hunt another to allow new birds to cpme in and establish patterns of feeding and roosting.

Decoys can be productive for doves at certain times of the day, provided you know a little bit about the bird's habits and hunt in the right areas. With a little ingenuity you can make your own out of paper mache' or wood, or you can buy commercial decoys. A half dozen will be plenty. Place them where they are silhouetted against the sky either in a dead tree or on a fence, and find yourself a nice shady spot nearby. You can build a blind, but it really isn't necessary.

HOW TO DRY WET BOOTSOne of the slickest ways to dry a pair of boots in a hurry is with a portable hair dryer or vacuum cleaner with the hose on the exhaust. The most important thing is to get warm air down into the toes. If you are drying rubber boots with a hair dryer, watch them closely so they don't get too hot, as heat can ruin them in a hurry.

Next time you wear out a pair of waders or hip boots, don't just toss them in the garbage. Cut the feet off and save the rest for hunting in rain or heavy morning dew when you have to walk through wet grass.

In an area where beggar's lice, stick-tites and other nuisance weeds stick to your clothing, don an old pair of corduroy pants. They are one of the few types of clothing that seem to be impervious to the little "beggars".

HOW TO AGE A SQUIRRELThe age of a squirrel can make a big difference in how you cook it, and the easiest way to tell age is by the shape of the tail. If the tail is narrow and pointed, as opposed to round and bushy, then it is probably a young squirrel. Older ones should be parboiled before frying or stewing, to make them tender.

If you hunt pheasants alone and they tend to run out ahead in weedy draws and shelterbelts, take along a transistor radio next time. Set it at one end of the area and circle around and hunt toward it. The sound of the radio might just be enough to make the birds hunker down in the weeds instead of running out the end.

32 NEBRASKAland GIVE QUAIL A BREAKLater on in the season when it's cold, plan on ending your quail hunting at least an hour before sunset. The reason is to allow broken coveys to get back together and into good roosting cover before dark so that they have a better chance of survival. It's also a good idea not to shoot into coveys with fewer than 8 to 10 birds, as fewer birds may not survive.

On the other hand, too large coveys going into the winter often have smaller birds, which can also decrease the survival rate.

How to Skin a SquirrelSkinning squirrels can be a snap, once you try it a few times. Some hunters make a circular cut through the skin completely around the midsection, then pull the two halves apart, but it often takes a strong man to get the job done. Another way that is a little easier involves cutting a v- shaped notch down the back of the hindquarters to the tail. Then cut through the tail bone, leaving the tail attached to the skin. Step on the tail, and while grasping the hind legs, pull upwards, stripping most of the skin off in the process. The rest comes off easily.

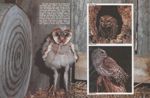

Finding SquirrelLook for squirrels in their feeding areas early and late in the day. Best areas are near oak, hickory and walnut trees in forested areas. Look for gnawed shells near the base of the trees. The edge of a cornfield adjacent to a windbreak is also a good place to find bushytails, as are osage orange or "hedge" rows in some areas.