NEBRASKAland

special sandhills issue

August 1977 60 Cents

NEBRASKAland

VOL 55 / NO. 8 / AUGUST 1977Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Sixty cents per copy. Subscription rates $5 for one year, $9 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503.

commissionChairman: Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-Central District, (308) 745-1694

Vice Chairman: Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473

2nd Vice Chairman: William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-Central District, (308) 452-3800 H. B. "Tod" Kuntzelman, North Platte Southwest District, (308) 532-2982 Richard W. Nisley, Roca Southeast District, (402) 782-6850 Robert G. Cunningham, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-5514 Director: Eugene T. Mahoney Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, Jr. Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree

staffChief, Information and Education: W. Rex Amack Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: Jon Farrar, Ken Bouc, Bill McClurg Contributing Editors: Bob Grier, Faye Musil, Roland Hoffmann, Butch Isom Art Director: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich

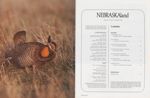

Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1977. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska Contents FEATURES A WINDBORNE LAND A Geologic History of Nebraska's Sandhills. . . . .4 THE SANDHILLS "A Great Place for Cattle and Men". . . . . . . . .10 A SEA OF GRASS/THE UPLANDS Life in the Sandhills Grasslands . . . . . . . . .18 THE WETLANDS/ISLANDS IN THE SAND Lake Country Wildlife........ . . . . . . . .. . .24 THE OUTDOORSMAN'S RETREAT A Summary of Sandhills Recreation . . . . . . . . 32 THE HOSTILE HILLS The Life and Times of Sandhills Indians. . . . . .38 LONESOME LAND A History of the Settlement of the Sandhills. . . 40 DEPARTMENTS TRADING POST. . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . .. . 49 COVER: Each August, Burwell hosts Nebraska's largest rodeo, drawing contestants from all over the country and spectators from far corners of the state. OPPOSITE: Male prairie chickens strut and show their stuff for two months each spring, all for the favors of demure little hens that may only visit the display grounds a few times before laying their clutch of eggs. Photos by Jon Farrar. AUGUST 1977 3

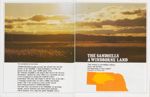

THE SANDHILLS A WINDBORNE LAND

THE EARTH WAS already incredibly ancient when incessant rains swelled a vast inland sea that spilled over the continent's interior. The land rose and fell and rose again. For 130 million years, the age of reptiles was upon Nebraska. Forty-foot aquatic Plesiosaurs, giant half-ton fish, turtles nearly twice as long as a man, sea serpents and monstrous lizards reigned in the sea, over what would someday be cattle ranches and cornfields. Hundreds of feet of limestone, shale and sandstone were accumulating on the sea floor; the bedrock upon which the Sandhills' final features would be fashioned more than 60 million years in the future.

At the close of the "middle ages" of geologic time, great earth

forces thrust the Rocky Mountains above the plain that blanketed most of

the western continent. For millions of years the traumatic rearing

of the Rockies would continue, tugging up close-lying tableland

to the east. Rivers sprang from the mountains, carving

great valleys and depositing a vast alluvial apron of coarse gravel, sand

and silt of a depth and breadth never equaled. The once great inland sea

became a dumping ground of waste from the Rockies. Deep deposits

7

Only two million years ago the Rocky Mountains were again thrust up. Rain-laden clouds from the Pacific were spent on the rising peaks, creating a rain shadow over the Great Plains, robbing them of moisture. Volcanoes disgorged ash in thick beds hundreds of miles

8to the east. Erosion ground down the tableland's high crust and filled its depressions until the mid continent from Texas to the Dakotas was nearly flat, dotted with isolated lakes.

For more than half a million years the climate was unsettled, alternating between cool and warm, moist and dry. In four major advances, glaciers ground down from the north only to wither back in the face of a warming world. Once abundant herds of horses, camels and rhinoceroses withdrew south with the tropical climate, crossed the Bering Strait land bridge to Asia or simply vanished forever from the North American plains. Succeeding them were the ice age mammals from Asia—the mammoths, giant bison with horns spreading 10 feet, musk oxen, the giant stag-moose, caribou and mountain sheep, wildcats and smaller deer—some to endure and evolve into historic species.

This was the Pleistocene; a violent epoch; a time of volcanism, mountain uplift and wholesale alteration of the landscape by glaciers, wind and water. The ponderous ice sheets rasped away at the land, shoving and gouging, piling ground rock and boulders a hundred feet deep before them. Glacial streams spewed heavy loads of silt and sand to the south. Existing rivers and streams were blocked; the Missouri turned from its northward course to the southeast, tracing the glacier's edge. Glaciers never reached north-central Nebraska, but, just as the vacillating climate controlled the comings and goings of the ice sheets, it shaped the Sandhills into the form we know today.

Compared to the continent's other land forms, the Sandhills are a mere child, conceived of the more ancient riverwashed rubble, (Continued on page 43)

9

THE SANDHILLS "A Great Place for Cattle and Men"

The lack of human associates together with the monotony of the landscape and the slow routine of the lonesome day, the parching winds of summer, the call of the range, and the crimping blasts of winter, has left a telling imprint upon the homesteader and has made him a grizzled, fearless man. Raymond J. Pool 1912HAVE YOU GOT a few more minutes? Have another cup of coffee and let me tell you what I know of these hills and their people. No, I'm not a sandhiller; didn't even move here as a boy. But I wish I had. I'm just passing through, like you, but I've passed through here before and I know something of these people.

Just for the record, let me set a couple of things straight. They don't all wear those wide-brimmed hats and polished, pointy-toed boots. Their legs don't bow and a tobacco-packed lower lip isn't some ailment peculiar to the region. They don't wear spurs, to town anyway, or brawl on Saturday nights, no more than most places, anyway. They're about like you and me; a bit more friendly maybe, more likely to stop if someone's got a flat or has run out of gas.

Here, look out the window while the waitress fills our cups. See those boys? The ones in the pickup, just out of school, passing the Red Man and roping the hydrants? It's a game for them now, part of the mystique of growing up in a land so close to its roots. Tomorrow it will be for real.

And those girls, with their long, sunbleached hair and fancy shirts with pearl buttons. They're no different than the girls we knew in our youth. Probably a rodeo queen or two among them. Perhaps they will be lured away from this land by the glittery, make-believe world of Revlon and Virginia Slims to fly the friendly skies of United or sample the chic life of San Francisco.

But these are just fleeting glimpses of impressionable youth. Sure, they're playing roles, just like kids everywhere. Let me tell you about the real people. They're not so conspicuous; don't work 40-hour weeks like us city people. You can know something of them by just looking around.

See that store across the street, the one with the sign written in rope- Western Wear? Mostly, that's for tourists like us. So are the clothes on the shelves by the door. But look in the back, on the corner shelves; that's where you'll find the not-so-pretty overall jackets with blanket linings and work shoes without the pointed toes.

Ranches are hub of Sandhills

life. Small towns supply them,

recreation nearly always means

rodeo; Levis, western hats and

boots are the perennial style

11

And back behind the hand-stamped saddles

with the roses; that's where the plain stock

saddles are. Now don't get me wrong. I'm not

saying that the tourists are buying all the

fancy saddles and down coats and 10-gallon

"Hoss" hats. All I'm trying to tell you is that

those things are mostly for the young people

out here or for those special dress-up occasions.

And back behind the hand-stamped saddles

with the roses; that's where the plain stock

saddles are. Now don't get me wrong. I'm not

saying that the tourists are buying all the

fancy saddles and down coats and 10-gallon

"Hoss" hats. All I'm trying to tell you is that

those things are mostly for the young people

out here or for those special dress-up occasions.

And here! Look at the flyers on the board by the door. "Twenty registered Hereford bulls for sale." "Cattle auction every Friday at Burwell." And over here, "1977 State High School Rodeo Finals, June 22-26." That's what these people do. Not many "garage sales," "babysitting wanted," or "Rock Concerts coming to Pine Wood Bowl" out in this country.

And look over there in front of the IGA. Six pickups and two cars. They've got a lot to carry out here. Not black or orange pickups, with pin striping, short boxes or carpet on the floors like back east. These are working pickups, with barbed wire scratches on the side, handcut ash or cresote posts in the back and more than likely a Handyman jack buried somewhere under the fencing tools. The paving doesn't always go from here to there in this country. A lot of four-wheel drives, not so you can be the only one to make it to work after the big snow that comes once every five years, but so you can mend fence, feed cattle and sure, once in a while hunt deer along the willows in the wet meadow west of the house. When you leave here, look at the county numbers on the license plates. That will tell you something about how it is to live out here-77, 93, 86-lonesome at times.

Like I said, you can tell a lot about how people make a living by just looking around. Can't tell much about the people themselves, though, by just glancing curiously at the three cowboys smoking and drinking coffee two stools down. Here, let me buy this round; I'll tell you about some of the people I've met.

You're going west, say, down highway 20. Well, when you get about 45 miles down the road you'll see a sign that says "Eli 2 Miles." Not much of a town anymore, but you can get an ice cream bar there when it's hot. The population may have changed since I was there. Seems like it was six last spring. Varies a lot with how big a family the minister in the town church has. Only a handful of houses left, but a store where you can gas up your car, buy groceries, pick up the mail and buy some basic veterinary or hardware supplies to

hold you over until you get into Merriman or Cody, Gordon or Valentine. Lois Gaskin has run the store for about 11 years now. In fact she grew up in the store. You see, Guy and LaVerle Belsky were her parents and they had the store for 32 years. Lois and her husband were living in Oklahoma when her parents decided it was time to retire. She couldn't stand to see the store close, so they moved back and kept Belsky's store at Eli on the map.

If you've got time you should stop by. It's at that uncomfortable stage between the old and the new—old wooden candy and display cases sit- ting next to a shelf of Pampers. Don't bother trying to buy any of the old cases or cowboy calendars, though. Lois said her mother sold a knife case a few years back but nothing else was for sale. "It wouldn't be the store in Eli without them," she said. And then, with a teasing glimmer, she told me about a newspaper story a few years back, when the country was wringing its hands over the energy shortage. It said that the modern supermarket with its open-faced freezers may have to give way to the old general store.

You know, there are a lot of places like the Eli store worth stopping at out here. They're sort of unofficial tourist sites, and the way I see it, those are the best kind. Once they're recognized for what they are, and put on the map, they're not the same anymore. Let me tell you what I mean.

Take old District No. 49 rural school on Willow Lake south of Johnstown for example. The outside is a concrete stucco that looks like it was made with local sand. There's a public notice for the 1968 election on the wall so I guess that was about the time it last heard the laughter of ranch children. Pigeons roost in the empty belfry now, swallows have found a way inside and built their nests on the west wall, and the unmistakable scent of skunk wafts from the foundation. The wooden shingles are old, and weathered, and splitting. The wooden door on the south has an ornate knob with a lock button in the center. The keyhole is inverted and above the knob, so I guess the whole mechanism is upsidedown.

If you look in the window, you can see tumbling stacks of Nebraska History

Elements of Algebra and English for Beginners. The little globe is still in place on the table, as is the picture of George Washington floating in the clouds. A small framed photo of the American flag hangs on the north wall with the Pledge of Allegiance printed at the bottom. You can almost close your eyes and see the children behind their initial-carved desks, hands over hearts, reciting it from habit. The blackboards wrap around the room; one only a couple of feet off the floor for the youngest students. The erasers are on the floor now, and not buzzing across the room, carefully aimed for the back of someone's head. The last kids to visit the school left their names scrawled across the blackboards, and a roll of toilet paper trails across the floor near the door. I wonder who made the last run to the little shack out back with it?

Let me tell you about another place you might visit if you're inclined to roam cemeteries on quiet Sunday mornings. There's a lot of history written between the lines on those tomb- stones. The Kilgore cemetery is right on your way. It occupies an appropriate, mournful hill overlooking Minnechaduza Creek to the north, and sandhills running south to meet the Niobrara River.

Sharp-eyed golden eagles and redtailed hawks soar overhead, and in the winter, grouse come here to hide from the storms in the thick cedar boughs. Over the graves are tussocks of sand bluestem and spindly stands of

If you stop, read the names. They'll tell you of the European origins of these Sandhills people. "Stanley Rothleuthner, September 12,1889-February 24,1969. Makin Wray, July 7,1827-February 19,1913 and his wife Sarah, October 14, 1832-January 8, 1912." Some of these people were contemporaries of Old Jules; endured the same hardships and struggles of a new and difficult land. Their stories, though, have passed untold. "Nathaniel Elliott, July 10, 1831-March 30, 1916." A Homesteader probably. Lived to see the rush of Kinkaiders come to the Sandhills and leave again. When you walk among the stones, pay attention to the number that died in December, January, February and March. The winters were more than they could endure. Off to one side you'll notice a quart jar resting on a bed of dried cedar needles, enclosed by the seed heads of wheatgrass. Inside, on a piece of paper, is written the epitaph of a baby girl who died at birth during the depression years of the 1930's. Those were tough years. And nearby, "Floyd Z., son of Susannah and Hugh Coleman, September 15, 1915-December 15, 1915. Gone to be an Angel."

But enough of this. Let me finish the point. I was trying to make.

I may be wrong, but it seems to me that you kind of ease into Sandhill life. There's a long transition from the "big" cities like Valentine to the ranches. Little towns like Eli are the first step. From there you go to the rural people who live on the fringe of the Sandhills or along the river valleys. Take Kenny Sprague for example. He lives down on the Niobrara bottoms south of Kilgore. I like to think of him as the Old Jules type; a hardlander; the kind that can't get away from the river and still feel comfortable. He's got a couple of big gardens, fruit trees, hunts deer and grouse and traps enough to satisfy that itch.

Kenny was born on the Niobrara

over in Holt County and the river got

in his blood. Ever since then he's just

been kind of moving upstream. He

lived on the Niobrara east of Valentine

for a while, and finally settled on

about 500 acres strung out along two

miles of river just south of the old Anderson bridge. Now let me tell you,

out here 500 acres isn't much. You can

run a few cattle but you've got to do a

little scratching and looking around to

make it over the short times.

about 500 acres strung out along two

miles of river just south of the old Anderson bridge. Now let me tell you,

out here 500 acres isn't much. You can

run a few cattle but you've got to do a

little scratching and looking around to

make it over the short times.

The last time I stopped to see Kenny and Anna Mae was early one Sunday morning. Well, we didn't quite get done talking by noon. Kenny says that the way he was raised, if you had company and it was getting on to meal time, you invited them in. It would have been rude for me not to stay, and anyway, who would turn down a home cooked meal of backyard venison neatly canned and stored in the ample root cellar along with about 1,400 quarts and pints of canned beans, beans with bacon, apricots, apples and apple sauce, wild cherry jam, wild cherry jelly, canned beef, squash, beets and pickled beets, and four bins holding about 55 bushels of potatoes, some over two pounds. So I stayed.

Kenny is one of those guys who spends a lot of time looking down. And, he's got more to show for it than most people. Like a yard full of mammoth and mastodon thigh bones, chunks of petrified wood that four mules couldn't move but that he dragged up out of the river, and if you show enough interest, he'll bring a candy box or cigar box out of the house with arrowheads and a musket flint wrapped in paper napkins. After he warms you up on the usual run-of-the-mill blowout points, he'll bring out the thinnest, most delicately chipped point you could imagine. When you hold that three-inch point up to the sun the caramel-colored flint shows light all the way across. "Bet it wasn't the first one he ever made," Kenny laughs. "A collector in Valentine told me he'd buy me supper for that point. Told him I couldn't eat that much."

You're getting in a hurry, aren't you? I'll try to finish up what I was saying about people easing into Sandhill life. It'll only take a couple more minutes.

Once you leave the river bottoms or the hardpan along them, there's no turning back. After you've bought into those grassy dunes, there's no chance to pad out your sagging income with an odd job in town. Either you make it or you don't.

It can even be a chore getting out to some of the ranches in the interior. The one-lane paving only goes as far as the county funds and sometimes that's not nearly far enough. Sooner or later the rutted blacktop with the sloughing edges gives way to two tire tracks with Hereford pasture in between. In the summer they are soft and drifting in with sand; in the winter ranchers feed their cattle hay on the trails to hold the sand. That works out pretty well until it freezes and the rock-hard cow piles and hoof-pocked ground turns the road into a Chinese checker board. The worst thing about being an easterner (that's anyone from the other side of Burwell and Broken Bow), is that you keep thinking you're on a regular road. For every quart thermos of coffee you try to drink while driving, you spill at least a pint in your lap. By the time you leave the Sandhills you have either learned to stop and drink your coffee or your upper thighs look like a steamed lobster's back.

That's about the way the road ends up over west of Kenny's place. It starts off like a super highway through the forest service land, then narrows to a good one-lane oil road by Schoolhouse and Twomile lakes. Even around Dead Man's Curve the road is still pretty good. "Slow up today, show up tomorrow" a sign reads. Then you come to the fork in the road and are forced to make a choice-take the forbidding sand trail to the left or the forbidding sand trail to the right. Hoping luck was with me, I made the right turn, past a sign that promised that the McMurtry Ranch was seven miles down the trail and the Kime Ranch two miles beyond. Just doing some crude calculations I extrapolated that to mean about 35 minutes to McMurtry's and 45 to Kime's. I rated that stretch as about a "one-half pint consumed per quart of coffee attempted" road.

Well, you don't go far before you hit Hub McMurtry's ranch; the edge of his 40,000 some acres. He was one of the Kinkaiders that settled here during the first decade of the 1900's and grew beyond the original one section of land that broke so many from his time. Every dollar he made went back into the ranch and he just kept growing. He's about 87 now, but he still drives 50 miles of pasture most days checking windmills and stock.

I kept on going until the road ended. The only sure way to tell if your road has ended out here is when you come up against a fence without a gate, a creek without a bridge or a lake with water in it. This time it was a cluster of houses and barn at the Kime ranch. If you spend any time in the Sandhills at all you'll bump into that name on a regular basis. Two or three generations back, a Kime moved to Cherry County, had five boys that all started ranching, who in turn raised families of ranchers until there were Kime ranches all over the northern Sandhills.

By my watch it was about a two hour drive from Valentine. Not the kind of place where you run to town for trivial wants or minor needs. It's about half-way between Whitman and Cody, or, as Lenard told me: "Put your finger on the map where you're the farthest from any town in Nebraska and you're on our place." Last winter, Lenard didn't go to town for seven weeks, and during the blizzard of 1949, no one could leave the ranch from New Year's Day until February 22. As a matter of course, they keep a two-month supply of food on the ranch.

Lenard and his brother Buzz moved out there with their father from a smaller ranch 20 miles north of Whitman in 1943. From that 6,000-acre beginning, the brothers have nearly tripled the size of their ranch until now it runs about six miles east and west, five miles north and south. In the Sandhills, that's a "good" sized ranch. The way I see it, that's about 27 sections of land, a couple thousand head of cattle and a lot of miles of fence to worry about. I'd say it must be a good life on a Sandhills ranch, but a hard one. I'm yet to see my first overweight rancher. Days begin out here when the sun rises out of the grass and ends when the work is done. A drought or killer blizzard can set a ranch back several years, not just wilt the tomatoes or freeze the peonies.

I could tell you a lot more about these Sandhills and its people but I can see you're getting itchy to go. You're heading west, huh? Well, have a good trip and take a minute to look this country over. You might grow to like it. Say, by the way, where did you say you're from? Fifteen miles north of Hyannis? Oh!

17

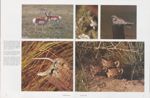

A SEA OF GRASS THE UPLANDS

The chophills lay like dun waves of a storm-tossed sea, caught and held forever in naked, wind-pocked knobs. Green yuccas crowded towards the higher hills like dark sheep running before a storm, and in the hollows were tight, tub-sized nests of bull-tongue cactus Mari Sandoz 1935

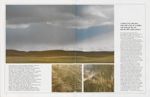

THESE ARE THE uplands; the essence of the Sandhills—where sand puppies skate over searing quartz, and yuccas wart the ridges. A place of grasses and yellow flowers; silvery sharptails and foul-tempered bullsnakes; chokecherries and snowberries and waxy plums. A scorching, frigid place, where kangaroo rats plug up their burrows at dawn in the summer and hide away in grass-lined nests below the frostline in winter. Survival here is a day-to-day affair. Heat burns, drought withers, and wind gnaws at any hint of weakness. A primitive place where the native life is as unyielding as its environment.

The uplands begin where the wet land leaves off; it is the dry valleys, side slopes and ridges above the lakes, marshes, wet meadows and river bottoms. The soil here is a Spartan's medium of fine-grained sand with only a pittance of organic material. The sting of hot summer winds is deceptively violent. Available moisture near the surface is minimal and temperatures can climb to 140° on the sand. At the turn of the century, a botantist reported that: ". . . one may cross over areas two hundred yards or more in width and count all of the plants in his path on his fingers." The control of prairie fires has tipped the scales in favor of the plants since that observation, and though vegetation is still sparse, it would be a peculiar individual that could perform the same feat today as hundreds of fingers might be required. There is little doubt that the uplands have changed markedly since the days when depressing accounts of the area littered the diaries of early explorers.

Grasses, especially the bunch grasses, are the most prominent constituents of the uplands. It is the domination by these multi-stemmed grasses that, according to early botantists, afforded the region its "great monotony". Little bluestem, which gives the hills their first hint of green in the spring and last blush of reddish-purple in the fall, is the measure by which others are judged. Growing with it is sand bluestem, sandreed and needle-and-thread. As tenacious as the bunch grasses is the yucca; soapweed or dagger weed to the locals. Its rosette of bristling leaves and elegant, milky flowers are the Sandhill's hallmark, defying cattle and wind, often thriving in mid-air, its support blown away. In the shelter of the bunch grasses and yuccas, less hardy grasses and herbs thrive—switchgrass, wheatgrass, lovegrass, bluejoint, wild rye and the gramas; spiderwort, blazing star, thistles, prickly poppy, milkweeds, primrose, puccoon, ragworts and bush morning glory.

Next to the grass-hidden ridges, blowouts are the upland's most prominent feature. Once, drought, fire and buffalo were the vectors of the blowout. Today, drought and fire still cut open wounds that are festered by the winds' fury but so do cattle at windmills or salt blocks, power poles and wheel ruts. Northwest winds scoop out the ridges, spilling sand over the top and down the south slopes. In time the crater blows so deep, and the waste piles so high, that the wind can eat into the ridge no more. The tough, spreading roots of blowout grass are the first to pioneer the sterile sand; its thin stand providing some measure of relief from the wind. New species—sandhill muhly, sandreed, psoralea, tooth-leaved primrose, and spiderwort—wander over the rim of the blowout. Finally, more enduring plants move in and the blowout becomes a grassy dish, a mid-day loafing place for grouse.

Woody shrubs like New jersey tea, sandcherry, plum and rose are here on the uplands—browse and beds for mule deer, thorny nest sites for butcher birds. Occasionally, small stands of hackberry take hold of south slopes, some to become isolated rookeries for great blue herons, and few will escape the bulky stick nests of the magpie. A hostile environment these uplands? Strange, that so much life endures it.

AUGUST 1977 21

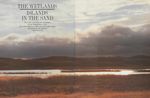

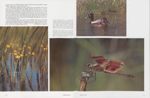

THE WETLANDS ISLANDS IN THE SAND

The lakes west from the headwater of the Dismal River were alive with wildfowl; swans, sand hill cranes, geese and ducks by the millions Luther North 1878

CLAPPER, BLUE CRANE, SWAN, Duck, Rat, Snipe, Pelican and Goose. The very names of Nebraska's sandhill lakes are a history and description. Carp spawn along their edges, in the Rush. Perhaps a Skunk or Jack Rabbit comes down out of the hills to drink, or a Coyote, or a Red Deer in its summer coat. Watch your step, there may be a Leach in the shallows or a Rattlesnake escaping the mid-day sun in the shade of a Sunflower, Willow, Hackberry or Cottonwood.

Some sandhill lakes are Clear as a Crystal and sparkle like a Diamond in the early morning light. Others are thick as Bean Soup, Sand Pudding or a Dipping Vat. Some smell like a Sewer or taste like Soda, others are Alkali, and some are the dumping ground for this generation's emblem, the Tin Can.

But what kind of people would hang such titles on these watery gems? Why, the British of course: Eaton, Collins, Haythorne, Jones, Robinson, Adams, Bristol and Bullfinch. And the Germans: Braunsweiger, Bornemann, Lotspeich, Wolfenberger, Brunner, Schick, Krause and Von Krosign. Scotsmen left their names on the sandhill lakes too: McNamara, McKeel, McCarty and McAlister. An O'Brien, Murphy or Kincaid might have indulged in a wee drop of the spirits while fishing one Sunday afternoon. Some lakes are in Camp Valley, others

in Lightning Valley, some Long, some shaped like a Punch Bowl and even one arched back on itself like a Claw Hammer. What more is there to say?

It is unexpected to discover such a profusion of small natural lakes spattered over a sand dune region. Rather, for those perverse individuals who have chosen to be on friendly terms with the Sandhills, it is unexpected to travel far without encountering one of these plums among the thorn bush. They are as indigenous to the area as the yucca and box turtle.

Nebraska's sandhills are often compared to an enormous sponge, soaking up every drop of rainfall and snow melt, allowing virtually none to run off. Absorption is immediate and moisture percolates through the porous sand to be trapped in the great depths of a sandstone reservoir below. The water table is high and surfaces in the deepest valleys as freshwater lakes, their level flucuating with the underground supply. Their drainage is subsurface, feeding the interior rivers with a near constant supply and charging the Platte and Niobrara.

Other lakes, especially those of Sheridan, Garden and Morrill counties in the

western Sandhills, receive water from the High Plains Tableland, their bottoms

plugged with clay. These are closed basin lakes, fed by runoff, and have no

connection to the water table. Salts are concentrated by repeated evaporation

AUGUST 1977

29

until the lakes are strongly alkaline. About 94 percent of the Sandhills' strongly

alkaline lakes occur in this closed basin.

until the lakes are strongly alkaline. About 94 percent of the Sandhills' strongly

alkaline lakes occur in this closed basin.

Over 1,600 lakes, ranging from 10 to 2,300 acres, are reported in the Sandhills. Even the fresh-water lakes are slightly alkaline, but some are so concentrated that only a handful of saline-loving plants and animals survive in them. Over 2,000 intermittent lakes, or playas, iess than one acre in size occur in the sandhill's. These are shallow, temporary waters that dry up most summers, leaving a sun-baked floor of mineralized salt. Some playas are fresh, though, and represent temporary high water tables during the spring rainy season. Many retain adequate water to see waterfowl and shorebirds through the critical nesting and brooding season.

Several thousand years ago, many of the Sandhills' lakes were connected, forming large irregular lakes that extended for many miles through the lowlying valleys, joining with lakes of neighboring valleys, fingering off in all directions. Sand from eroding ridges and the (Continued on page 42)

The Outdoorsman's Retreat

NOBODY IS INDIFFERENT toward the Sandhills. Either they like them or they don't. The same attitude probably applies to Sandhills recreation, as well. If your aristocratic old pointer doesn't work well with a paw full of prickly pear, he probably won't find the bird hunting much to his liking. If you're fond of hunting whitetails from some river-bottom stand, you'll find your selection of trees, with just the right crotch, limited out here. And, if you're accustomed to consuming a couple of two-dollar novels while waiting to get onto the boat ramp, your reading is going to fall off.

If, on the other hand, you have a low tolerance for crowds on opening day, but like one-to-one action on pike in shallow lakes, native brown trout that sulk in deep pools, ducks that hang over the decoys long enough to put your coffee down, grouse that sometimes let you get within range, old mule deer, or an evening flight of doves to a windmill pond, well, you just might like the Sandhills.

Of all the places in Nebraska, the Sandhills comes closest to being just about like it always was, and that is what most outdoorsmen are looking for. Sure, there's a man-made lake on the Snake River and trout are stocked in Long Pine Creek, but in general, things out here are about the way they have always been. Like most of Nebraska, over 97 percent of the Sandhills is privately owned. About 358,000 acres are open to public recreation. What makes the difference is that the Sandhills is cattle range and good habitat for a herd of Herefords is about the same as good habitat for wildlife.

Take prairie grouse for example. In Nebraska, grouse are Sandhills birds. With a few exceptions, you don't find one without the other. Sharptails range over all of the Sandhills, while prairie chickens are restricted to the eastern counties, especially Brown, Rock, Holt, Wheeler, Garfield and Loup. This is one of the few places left in the country where a hunter can double up on two species of grouse. Hunt the wet meadows and hay fields and you'll be shooting mostly bar-bellied chickens; move up on the dry ridges and more than likely you'll flush sharptails.

There are five public areas in the Sandhills open to grouse hunting: about 46,000 acres on Crescent Lake National Wildlife Refuge between Oshkosh and Alliance; over 115,000 acres on the McKelvie Division of the Nebraska National Forest south of Nenzel; the portion of the Valentine National Wildlife Refuge west of state highway 83; several thousand acres surrounding Merritt Reservoir; and 90,000 acres on the Bessey Division of the Nebraska National Forest near Halsey. Hunting pressure can be heavy on some of these areas on the opening weekend, but all have more than enough grouse to go around.

Grouse are the Sandhills' No. 1 upland

33

Nebraska's newest game bird, the mourning dove, begins gathering in immense flocks for migration in late summer, feeding on wild seed crops along roadsides and streams. Small, natural potholes and windmill overflows provide morning and evening pass shooting. Dove hunting is allowed on the two national forests and on designated state areas.

During years of normal rainfall, the Sandhills' duck hunting is unequalled. Native teal and mallards are on hand when the season opens, and their numbers are swelled by early migrants from the prairie provinces of Canada. Many of the best duck hunting lakes are on public areas. The bays and points of Merritt Reservoir offer pass shooting and hunting over decoys for diving ducks. The backwaters on the upper arms and the potholes between are the best puddle duck waters. South Twin Lake and Long Lake southwest of Johnstown; Rat and Beaver Lakes, Ballards Marsh and Big Alkali Lake south of Valentine; Goose Lake south of O'Neill; and Smith Lake south of Rushville are top state areas for duck hunting in the Sandhills. Sandhills waterfowl hunting ends abruptly with the first hard freeze.

All of Nebraska's big game species—white-tailed and mule deer, pronghorn, and Merriams turkey—are represented in the Sandhills. The Niobrara River from south of Cody to north of Newport is the prime turkey range. Merriams are being restocked at the National Forest near Halsey to rebuild that population to a level that can again be hunted.

Traditionally, the Sandhills was the exclusive range of mule deer. But, the more elusive and productive whitetail has supplanted the mule deer over much of their range, especially along streams and in the lake country. The large federal land tracts offer the best public hunting but also the most hunting pressure.

34 NEBRASKAland

Pronghorn are spread sparsely over the Sandhills, and hunters must cover more ground in search of their prey. Northern Cherry County, Grant, Arthur, Hooker, Thomas and Rock counties, have slightly higher densities of pronghorn. Their remoteness often accounts for trophy bucks.

Most hunting in the region is on private land. Access to grouse, deer and pronghorn is generally good except along rivers. Finding a place to hunt turkey can be downright difficult, but not impossible. A scouting and 'land hunting" trip several weeks before the season will generally bring a hunter and landowner together. Respect for property and courtesy are the keys that unlock gates to private land.

Hardly anyone will argue that the Sandhills offers the most pristine fishing in the state. Merritt Reservoir is the only impoundment, and fishing there is so removed from hurlyburly urban fishing that no one cares how it came to be. Crappie and perch are the staples, but the action on walleye, white bass and largemouths is also good.

Two of the state's top trout streams—the Snake River and Long Pine Creek—flow through the northern Sandhills. Fee fishing is available on the Snake below Merritt. Long Pine State Recreation Area and Pine Glen Special Use Area provide public access to Long Pine Creek. Plum, Fairfield and Grade creeks round out the trout streams.

Throughout the year, though, the Sandhills' natural lakes draw most of the attention from fishermen. Several of the wildlife refuge lakes have been recently renovated to remove rough fish and to re-establish game fish populations. Duck, Dewey, Clear and Pelican lakes on the Valentine Refuge, and Island and Crane on the Crescent Lake Refuge, are the top lakes now but a couple of these are scheduled for renovation in the future. Largemouth bass, bluegill, crappie, northern pike and yellow perch are the Sandhills' primary fish and each lake seems to specialize in one species or another. Aquatic vegetation and dense stands of emergent vegetation make the use of boats, chest waders or "donut" float rings desirable.

The opportunity for outdoor recreation other than hunting and fishing in the Sandhills is nearly untapped and unlimited. Three canoe trails have been officially outlined and others will doubtless follow. The Niobrara is considered the standard by which other rivers in the state are measured. The Dismal is a bit more testy, with numerous natural and unnatural obstacles for the more experienced canoeist. The Calamus offers a slower, more relaxed pace. A series of soon-to-be-announced backpacking trails will only be frosting on an already tasty cake of recreational opportunities in the Nebraska Sandhills.

THE HOSTILE HILLS

"The Great Desert is frequented by roving bands of Indians who have no fixed places of residence but roam from place to place in quest of game" Stephen Long 1819THE STORY OF MAN in Nebraska's Sandhills may have had its beginning some 25,000 years ago 5,000 miles to the northwest where the Bering Sea now separates the Soviet Union from the coast of Alaska. Perhaps early man's arrival was during the time of the last great glaciers grinding their way southward across the North American continent. With so much of the planet's moisture locked in the enormous ice sheets, the oceans fell 400 feet, exposing .a land bridge between Asia and North America over which many kinds of animals passed freely for a few hundred thousand years. Among, and hunting these animals, was man.

Moving southward through the ice-free corridor >etween the Rocky Mountains and the Wisconsin ice sheet to the east, they followed the herds of grazing animals and lived well off their frequent kills. This was the Pleistocene period; a time of abundant and varied mammals: the mammoth, ground sloth, giant beaver, the prehistoric horse and bison. We know little about these people; probably they were gatherers of wild food and nomadic hunters, using stone weapons that they fashioned with great skill. Perhaps the numerous streams flowing eastward from the Rockies diverted some people onto the Great Plains. As the last sheet of ice shrank back north and the climate became warmer and drier, the lush vegetation of the south changed, many of the large grazing animals vanished, and early hunters of the mammoth moved northward to the Great Plains with the remaining herds. Then, some 10,000 years ago the mammoth vanished. Perhaps the early hunters disappeared with them, perhaps they turned their attention to the large prehistoric bison and became Folsom man. This was a time of heavier precipitation than the present and pine forests probably covered Nebraska. Some say that Folsom man num- bered only 10,000 people in all, and hunted in hundreds of small bands. Other groups of big game hunters, descendants of Folsom man or perhaps newer emigrants across the land bridge, followed the roving herds over much of the Great Plains including the Sandhills of north-central Nebraska. It is likely that those hunters stayed close to water courses, not only to gather abundant wild foods but to ambush grazing animals that frequented them. Even today, the relentless Sandhills winds uncover the delicately chipped hunting points of those people, most often along the rivers and feeder streams that cut away at the fragile dunes.

What happened to the paleo-Indian people is a matter of frequent conjecture. As the glaciers retreated, the climate changed on the Great Plains and even the Folsom bison disappeared or evolved into more modern form. Fakes, marshes and streams were drying up, vegetation was by no means as lush, and many animal forms disappeared. Some have suggested that, man's persistent hunting of prehistoric mammals, or man's use .of fire to drive the herds, may have contributed to their extinction. More than likely, a changing environment precluded the survival of such large grazing animals. Did the early big game hunters disappear with their quarry, or did they survive to become the ancestors of our (Continued on page 43)

Lonesome Land

"A vast and worthless area... a region of savages and wild beasts, of deserts... cactus and prairie dogs... to what use could we hope to put these great deserts?" Daniel Webster, circa 1850 Photos courtesy of Nebraska State Historical SocietyTHE FREE NOMADIC life of the Great Plains Indians ended abruptly with the passing of the buffalo. In 1875, the Sandhills were empty, waiting passively for a new wave of people. But the land, described by Scotsman James Mackay in 17% as "a great desert of drifting sand without trees, soil, rocks, water or animals of any kind except some little vari-colored turtles of which there are vast numbers", repulsed the flood of settlement, tolerated the farmer and rancher only in trickles and turned back far more than it accepted. "It's great country for cattle and men, but hell on horses and women", one Grant County woman said of the Sandhills, a fact to be discovered by accident at the price of great hardship.

Exploration and exploitation of what would one day be Nebraska was sporadic during the early decades of the 1800's. Lewis and Clark ascended the Missouri River in 1804; Zebulon Pike was sent by the Governor of Loui- siana to find the headwaters of the Red and Arkansas rivers and to escort some Osage and Pawnee to their homeland on the Republican River in the summer of 1806; and a scientific party under the command of Major Stephen H. Long moved along the Platte River in 1820 giving birth to the unfavorable impression of Nebraska as a "Great Desert".

By the 1840's and 1850's, the Platte Valley became the road to the rich, unsettled lands of the west and a flood of emigrants poured across Nebraska. As early as 1843, a thousand settlers snaked along the Oregon Trail, their numbers swelling each year through the 1850's. In 1847 the Mormons broke a new trail through the Platte Valley, along the north side, a stone's throw from the southern edge of the sandhills. But, no one looked north. Two years later, a wave of 20,000 "forty-niners", their eyes riveted on the gold fields of California, poured across the state. Over 55,000 settlers and would-be panners swept by the fringes of that "great desert of moving sand". Gold and rich farmland in Oregon goaded them on. In 1854 Nebraska Territory was established but no one seemed to notice. Until that time, the land west of the Missouri River was Indian Territory, (Continued on page 45)

THE WETLANDS

(Continued from page 30)encroachment of water plants severed and isolated the webwork lakes until they were clusters of smaller lakes connected by marshes and wet meadows. Each year tons of organic matter were crushed to the bottom of the remaining lakes by snow and ice. Rushes, reeds and pondweeds advanced farther into the lakes, shrinking them in size until they were marshes with small areas of open water. Older lakes have completely filled to become wet meadows. Today, lakes and former lakes at all stages of succession can be found, often within a few miles of each other.

Young fresh-water lakes are the Sandhill's womb; a teeming assemblage of jewel-like algae and zooplankton, mats of pondweed, muskgrass, coontail and water milfoil; choked shorelines of rush and reed; carpets of sedges that girdle the edge. Lime-and-black salamanders, sleek bodied pike and slab-sided bluegill patrol the sun-washed shallows; jaunty ruddy ducks, canvasbacks, teal and mallards squabble in the backwaters and trail their downy young along lake margins to feed. Herons, pelicans, and bitterns stalk fathead minnows or yellow perch.

Peat-bottomed marshes cap the ends of sandhill lakes or have crept in to claim the open waters, cinching them in stands of bulrush, piercing them with phalanxes of plume-headed common reed broken by small stands of cattail. Their control is absolute; sunlight seldom penetrates to the water level. Here the marsh birds gather. Nests of yellow-headed blackbirds with their naked squalling young, more territorial redwings, furtive marsh wrens and ground-nesting marsh hawks. By summer the choked stands of fruiting emergents become a refuge for deer—a fawn's mottled coat melting into the play of sun and shadow—and in the fall the bane of hunters. Pheasants wait out winter storms under their crushed canopy.

The wet meadows—old lake beds piled with putrid, decaying vegetation, transformed by time into sweet-smelling basins of rich loam, crowded with grasses and forbs—are luxuriant pasture for wild and domestic mammals. Slough grass, switch grass, Indian grass and bluestem. Bluejoint, redtop, timothy and slender wheatgrass. The most agressive among them climbing six feet above the water impregnated soil. In July these wet meadows become hay meadows, but not until they've given birth to dozens, sometimes hundreds, of broods of mallards, blue-winged teal, gadwall, avocets, phalaropes and meadowlarks; or their clovers have filled the crops of prairie chicken and sharptails. This is lake country, where water, grass and sky come together; a gathering place; a growing, pulsating place; the germ of sandhill life, a merciful pause before the I next ridge and dry valley.

42 NEBRASKAlandWINDBORNE LAND

(Continued from page 9)but born of a modern wind. If the 4.6 billion years of the earth's history were condensed into one hour, the Sandhills would have begun to form only one-half second ago. They are newcomers, arriving before the end of the last great glacier some 10,000 years ago.

During three cold, arid periods, the vegetation lost its grip on the land. Attacking north winds carried the fine-grained silt to the south and east and washed great waves of sand into east-west ridges, some 10 miles long, a mile wide and 100 to 300 feet high. For thousands of years the thick sheets of sediments, deposited in Nebraska epochs before, were sorted and shaped by the dry winds. The climate moderated, turned moist, and vegetation bound the rambling sands. Erosion rounded the steeper slopes, shallow soils began to form, and drainage systems conformed to the new landscape.

Toward the end of the continent's last glacier, the climate again turned dry. The parched vegetation yielded and the wind renewed its attack, reworking the old formations. A second generation of dunes was cast diagonally across the old ridges by the prevailing northwest wind. These were smaller dunes, no more than two miles long and 300 to 600 feet wide, oriented in a northwest-southeast fashion. A short interval of stabilization followed before the third and final period of dune building began. This last episode of wind action was comparatively minor, pocking the larger dunes with small but closely spaced blowouts.

Nebraska's Sandhills have changed little since. Fires set by lightning or Indian hunters to drive buffalo herds have periodically stripped away the dunes' fragile covering of vegetation and set them in motion. Wind erosion opens new wounds and festers old ones. But, the effect pales in comparison to the disfigurement of earlier periods. Today, the mammoth east-west ridges, smaller diagonal dunes and the ancient blowouts are still the landscape's prominent features.

Bordered on the north by the Niobrara River and on the south by the Platte Valley, the sandhills roll eastward until they mingle with the fine loessial soils near Broken Bow and O'Neill and westward to the High Plains tableland at Alliance. Here, in north-central Nebraska, the dunes occupy a rough diamond-shaped area 260 miles east to west and 130 miles north to south; over one quarter of the state, 19,300 square miles, the largest dune area in the Western Hemisphere.

It can be a hostile land with unbroken winds heaping misery on winters that plunge to 40° below or summers with scorching temperatures climbing to 110° above. Precipitation is adequate, when it comes, to sustain the native grasses; 24 inches annually in the east, 16 inches in the west, some 80 percent of it during the spring and summer growing season. But the scant rainfall and sometimes sparse vegetation belie the generous reserve of water stored only a few feet under the sweltering sand.

Thick beds of sandstone, some 700 to 800 feet deep, form a natural reservoir that stores 350 to 400 times the water of Lake McConaughy, sealed by the impervious shales and clays of the ancient sea bed. Fed by this underground supply, the North and Middle Loups, the Dismal and Calamus rivers maintain near uniform flows.

Alternating with the stabilized dunes are broad, dry valleys and wet meadows bejeweled with lakes. Over much of the Sandhills the surface of these freshwater lakes is the water table, fluctuating with underground supply. On the western edge, in Garden and Sheridan counties, many of the lakes are above the water table, their bottoms sealed by clays and their waters alkaline.

Man in the Sandhills has largely accepted his environment for what it is: the continent's finest pasture, a fragile grassland unkind to those who abuse it. Those who endure come to terms with the hills and crop its natural abundance, those who plunder its riches are repulsed. A crude sign scrawled on the side of a Kinkaider's shack near the edge of a healing blowout put it succinctly: "God placed this soil upright. Don't turn it over."

HOSTILE HILLS

(Continued from page 39)our modern North American Indians that thousands of years later expanded to fill the continent? One thing is fairly certain: for two thousand years, perhaps longer, from about 4,500 B.C. to 2,500 B.C., an enduring drought struck the Great Plains. Archaeological evidence suggests that western and north-central Nebraska were without human occupants. At the end of the drought, a people that hunted and gathered food moved back onto the plains, relying less on the bison and more on smaller animals, wild fruits and roots.

SPEAKING SPECIFICALLY of the Sandhills region, Waldo Wedel in his text, Prehistoric Man On The Great Plains, says: "We may suppose that this has always been primarily a hunting ground, with native human occupancy centered along the valieys of such perennial streams as the Loup, Calamus, and Dismal rivers, and about the shores of the innumerable small lakes of the western and northern portions."

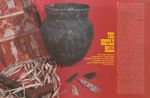

By 400 A.D., though, a more modern man appeared on the Great Plains; still hunters, but less nomadic, perhaps, these Plains Woodland people migrated from a culture in the forested regions of the East, most likely the Ohio Valley, and occupied virtually all parts of Nebraska. In small thatch or hide covered huts with central fireplaces, they formed villages along the smaller streams. Though still food-gatherers and hunters, they may have cultivated corn, squash and beans. For the first time, pottery appeared in Nebraska.

For perhaps as long as 3,000 years the Plains Woodland Indians hunted and harvested before giving way, or merging with an even more sedentary people, the prehistoric Pawnee, who lived in large unfortified villages along the Republican River, in the Loup valleys and in Missouri River country. Those early farm people practiced intensive corn and bean culture and perhaps even added sunflower and tobacco to their crops. They appear to have at least occupied seasonal hunting camps in the Sandhills. For 500 years, from about 1000 A.D. to 1500 A.D., they lived a peaceful existence producing a high quality pottery before being pushed south, either by more aggressive people or by a prolonged drought with fantastic dust storms during the latter part of the 15th Century.

BY THE MID 16th Century, the lower Loups were again occupied by Pawnee, possibly the grandchildren or great grandchildren of the earlier culture. For two centuries, through the earliest of the white man's contacts with the native peoples of the Great Plains, these tribes occupied or controlled most of eastern and central Nebraska, including the more rolling eastern Sandhills.

During that same period, from about 1600 A.D. to 1700 A.D., other small villages similar to those of the Loup Pawnee, occupied the headwaters of the Elkhorn on the Sandhills' eastern fringe. Engaged in big game hunting as well as agriculture, those tribes, probably ancestral Ponca, as well as those of the Loup rivers, coursed the streams that led deep into the Sandhills, especially along the Niobrara River. Being primarily agriculturalists,, it is doubtful that they established permanent camps much beyond the edges of sandhill country while more fertile, broad valleys lay in the loess hills to the south and east.

It seems most likely that the first white man to view the vast, grass-covered dune country of Nebraska's Sandhills was a French trader or trapper in the early 18th Century. Reportedly, the French established a trading post at a fork of the Snake River on the northern edge of the Sandhills, a neutral ground where Poncas, Sioux, Cheyenne and even Pawnee traded without conflict. For 100 years, rugged, back-country Frenchmen were the only whites known to the Indians. Their influence and effect on the Indian tribes of the Great Plains is immeasurable, and it has been suggested that in part they led to the demise of the Sandhills' only tribe of resident Indians, the Padoucas or Plains Apache. (Continued)

AUGUST 1977 43

WHERE THEY CAME from is speculation. It has been suggested that the Plains Apache broke off from a movement of Apachean people that trickled south from the MacKenzie River Basin in Canada, along the eastern face of the Rockies during the early 14th Century; some continuing southwest to settle in eastern Colorado, northeastern and southern New Mexico, northern Mexico, west Texas and eventually Arizona.

Wherever they came from, the Apache that occupied the western and northern Sandhills during the last quarter of the 17th Century and the first quarter of the 18th Century were not destined to endure.

This Dismal River culture of Indians, so labeled because they were first recognized as a distinct group through archeological work done at the fork of the Dismal River in Hooker County, were principally hunters with only a secondary interest in the cultivation of crops. Scrapers, chopping tools, drills and an abundance of small, rather crude hunting points found at their campsites, are the artifacts of a people that lived by hunting, butchering and working skins. Bone hoes and stones for grinding corn are limited. The absence of cache pits is further evidence that they were not thriving agriculturalists, a condition to be expected of people inhabiting the loose soils of the Sandhills. It seems probable that they relied upon seasonal fruits and root crops. Their pottery was crude; more utilitarian than that of the Pawnee, and occasional finds of rare metals and turquoise indicate that they traded freely with tribes of the southwest.

During their early years in the Sandhills, the Plains Apache probably enjoyed a peaceful existence if not a luxuriant one. Occupying the stream terraces of the Dismal and Loup rivers, and the shores of sandhill lakes in what is now Cherry County, they weathered periods of food shortages and harsh storms in circular or pentagonal huts covered with skins or grass thatching.

But, a peaceful existence was not the fate of these Dismal River people—Comanches from the south and west were extending their raids farther onto the Plains, and the Pawnees to the east were in possession of horses and French guns.

IN HIS BOOK, The Plains Apache, author John Upton Terrell describes the fierceness of the Comanche-Apache confrontations: "The economic conflict that raged through the first four decades of the 18th Century between the Comanche and Plains Apache cannot be compared in destructiveness and in constancy with any other confrontation in Indian history ... it created pressures that the Plains Apache could not withstand". The Comanches were well supplied with horses and guns from French traders and easily overpowered the small villages of Apache.

During the same period it was reported that the Skidi Pawnee of the lower Loup were conducting an immense trade in captive Plains Apache with the French. In the fall of 1724, the chiefs of the Podouca, Kansa, Pawnee, Oto and Iowa agreed to a peace proposed by the Frenchman Bourgmond, a move initiated by the French government to expand their territory to the southwest and to discourage Spanish influence. The Padoucas were offered gifts of guns and the slave traffic stopped—probably for less than two years. It has been suggested that enterprising French traders opposed ending the lucrative trade in captives, and since the Padouca were not good suppliers of furs, the traders had little concern for friendly relations.

The fate of Dismal River Apaches, hemmed in between Pawnees on the east and raiding Comanches on the west, both armed by the French and with good supplies of horses, was sealed. Some historians say that the Padouca were destroyed as a people by 1727. Perhaps the isolated Sandhills tribes held out longer. But, by the third decade of the 18th Century, the Padouca Apache were heard of no more. Some reportedly moved north, south of the Black Hills, eventually to be pushed out by the rising tide of Dakota Sioux. Most, it has been theorized, withdrew to the south. The short and tragic history of what was perhaps the Sandhills' only resident people up to that time, had ended. From 1750 to the time of settlement by the white man, the Nebraska Sandhills would be only a buffer, occasionally a retreat and hunting ground, for waring, horse- mounted tribes.

LONESOME LAND

(Continued from page 40)outside of the United States, but now it was smack dab in the center.

The first real exploration of the Sandhills was carried out in 1855 by Lieutenant G. K. Warren of the U.S. Topographical Engineers. The earlier impressions of Mackay were reinforced. Traveling from Ft. Pierre on the Missouri to Ft. Kearny on the Platte, Warren noted in his journal that: "The sand is nearly white, or lightish yellow, and is about three-fourths covered with coarse grass and other plants, their roots penetrating so deep that it is almost impossible to pull them out. The sand is formed into limited basins, over the rims of which you are constantly passing up one side and down the other, the feet of the animals frequently sinking so as to make the progress exceedingly laborious."

On a second trip across the Sandhills two years later, Warren administered his coup de grace. "The Sandhills area has been covered with barren sand which, blown by the wind into high hills, renders this section not only barren, but in a measure impracticable for travel. About the sources of the Loup Fork, many of the lakes of water we found are impregnated with salts and unfit to drink, and our sufferings in exploring them will always hold a prominent place in our memories." He concluded his report by saying: "An irreclaimable desert of two hundred to four hundred miles in width separates the points capable of settlement in the east from those on the mountains in the west." Into this inhospitable land came the ranchers and settlers, not a swelling throng to be sure, and quite by accident in the beginning.

IN 1867, NEBRASKA and its 50,000 residents were admitted to the Union as the 27th state. The establishment of the Bozeman Trail to the gold fields of Montana, and heavy emigrant traffic along the Platte Valley trails, proded the Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapahoe into bloody raids. The U.S. Government was quick to remedy the situation with the Fort Laramie Treaty of April 29, 1868, affirming the Sioux's right to all of Nebraska lying north of the North Platte River, "so long as the buffalo may range thereon in sufficient numbers to justify the chase". All but the easternmost Sandhills were included, worthless land in any case, it seemed at the time.

The rights of Indians proved to be only a pebble on the road to settlement. By the 1870's, cattle ranches were moving up the river valleys of the Loups, into the Sandhills and Indian territory, and ranging north of Ogallala, then a dying railhead at the end of the long Texas cattle drives.

The first cattle to use the Sandhills overflowed from the ranches on the eastern fringe. Each year the herds pastured deeper into the hills' luxuriant grasses. As early as 1872 they had moved along the South Loup Valley near today's town of Arnold. Ranches in Custer County moved up the Middle Loup and to the Dismal River.

During the winter of 1874-75, one of the first large cattlemen moved into the Sandhills from the south. John Bratt, an established rancher running stock between the Platte and Republican rivers, capitalized on an otherwise disastrous event. During the fall of 1874, a wind-driven prairie fire stripped the range in most of Nebraska's southwest. After shipping what stock he could to Chicago, Bratt explored the Sioux land north of the Platte for winter range. More concerned with his impending financial collapse than violation of an Indian treaty, he ordered his men to gather up the Platte River stock, move across the river and up the valley of Birdwood Creek northwest of North Platte. There they built a sod stable and a shelter for themselves. Later he moved to the headwaters of the Dismal and claimed range that extended 24 miles east and west and 75 miles north and south.

Bent on settlement of its outlands, the U.S. government neatly disposed of the Indian lands north of the Platte. In the spring of 1875, the Sioux relinquished all claim to lands between the North Platte and Nio- brara rivers for a cash payment of $25,000. In the fall of 1877, the Sioux signed another treaty giving up all of their Nebraska land and moved to reservations in South Dakota. The Sandhills waited.

In the spring of 1877, Colonel "Buffalo Bill" Cody, Major Frank North and Captain Luther North established the Cody-North Ranch at the headwaters of the south fork of the Dismal River. They built a log house, sod barn and cedar pole corrals. Their nearest neighbor was John Bratt on the Birdwood, 50 miles to the south.

In his published recollections, Luther North described the Dismal River Ranch: "The country was full of game: elk, whitetail and mule deer, antelope, and many prairie chickens, and the lakes west from the head of the Dismal River were alive with wild fowl: swans, sandhill cranes, geese and ducks by the millions." Trumpeter swans ate bread from North's hand and he raised and trained a sandhill crane to kill mice in the house. North was one of the last men to see free-ranging buffalo in the Nebraska Sandhills.

"Soon after the roundup of 1881 ... I came across a trail that I took to be cow and calf tracks, and followed to see whose they were, and when I came in sight of them I almost fell off my horse with astonishment, to find it was a herd of buffalo. There were twenty-eight grown ones and five calves in the herd. That country had been ridden over for four years by cowboys and hunters by the hundred, and no one ever dreamed of seeing any buffalo there." The last band of buffalo ever seen on the north side of the Platte River in Nebraska met a fitting end, being killed by Sioux from the Spotted Trail Agency shortly thereafter.

Familiarity bred confidence. The new ranchers probed deeper into the Sandhills, often driving their herds for miles through choppies and lake country. In 1876, James H. Cook had driven 2,500 steers from Texas to the Platte River east of Ogallala, to Birdwood Creek, and on to the headwaters of the Dismal River, across the Middle Loup, Snake and Niobrara rivers to an Indian agency on the White River in South Dakota.

Frank North, no doubt knowing of the Cook drive, decided to move his herd across 60 or 70 miles of little known hills in the spring of 1879 and cut several days from the longer southern route. Leaving the annual spring roundup at Blue Creek north of present day Oshkosh, North and his drivers pushed their stock east through the rugged choppies. At the end of the first day they camped at a small lake with cattle trails gathering to it like spokes to a hub. The next morning they rode out to see who was running stock on that range. Several days later they had rounded up 700 head of "cattle wild as deer, even some three-year-olds that had never seen a man." About half wore the brand of a Middle Loup ranch, but the remainder were wild cattle and were claimed by North. While North's main herd were thin, these maverick cattle where sleek and ready to ship.

The following year, 1879, an almost identical discovery on the northern edge of the Sandhills threw open the Sandhills secret. E. S. Newman had established the Niobrara Cattle Company at the mouth of Antelope Creek in northwestern Cherry County. The larger part of Newman's range was to the north of the Niobrara but some extended onto the hardland south of the river before it gave way to sandhills. To keep his herd from drifting into the inhospitable hills, he maintained line camps on the southern rim of the Niobrara. The March blizzard of 1879 hit, line riders were forced to seek shelter, and when the storm had passed, 8,000 head of cattle were gone, wandered off into the sandhills. Only the fear of bankruptcy convinced Newman to send 12 of his best men in after them. Nellie Snyder Yost in Call of the Range, says that the wagon had: ". . . provisions enough for a trip to the Gulf of Mexico. The outfit had barely reached the true Sandhills, the edge of the fearsome country of lost men and cattle, when another blizzard struck. . . . The storm lasted three days, the horse herd got away, and they had no fuel except the little dab of wood they brought along, tied under the wagon. When the storm was over they gathered their saddle horses and made another start. The scouts sent out ahead of the wagon soon began to strike cattle, perfectly contented amidst the splendid grass and water of the Valleys." (Continued)

AUGUST 1977 45

BY THE END of the 1870s the heart of the Sandhills was surrounded by ranches, their herds wintering deep into lush rangeland. Only a handful of cattlemen headquartered in the hills, though. Grangers were rushing into the fringes of the hills along the river and creek bottoms; throwing up soddies in a day or two, stringing fences and breaking the fragile sod that ranchers believed was meant only for cattle. The stage was set for sporadic conflict between settlers and ranchers. The Sandhills stood at the brink of settlement and conflict.

The Pre-emption Act of 1841 allowed settlers to buy land for $1.25 per acre. American soldiers, chiefly veterans of the Mexican War, were also allowed to file on public land. Then, in the spring of 1862, the Homestead Law was enacted, permitting families to file on a quarter section for $10, providing they lived on the land for five years and made improvements. The Timber Culture Act, added to the list of land settlement laws in 1873, offered ownership to yet another quarter section if trees were planted on 40 of those acres. Later, that requirement was reduced to 10 acres. Settlers filing under the Pre-emption, Homestead and Timber Culture acts, could claim a total of 480 acres. The lure of cheap land brought strings of oxdrawn covered wagons and ambitious eastern farmers.

The dry years of the 1870's were followed by years of above average rainfall. Crops of corn and potatoes were encouraging. Dr. Samuel Aughey, Professor of Natural Sciences at the University of Nebraska, published a paper that popularized the theory that "rainfall follows the plow". He believed, and gathered many eager followers, that broken prairie increased the absorption and retention of rainfall, increased evaporation and resulted in increased moisture and rainfall.

Never-to-be-forgotten blizzards of the 1880's were only one Sandhills hardship to greet homesteaders. The October blizzard of 1880 started with a sleet that sealed the land. Then came a foot of snow and more freezing drizzle. The wind-whipped cold was insufferable. Established ranchers suffered the most, for homesteaders had little to lose. Thousands of cattle drifted southeasterly, away from the storm, breaking through crusted snow and leaving bloody trails from lacerated feet, then piling into fences or stream bottoms to die. The storms continued throughout the winter and into spring.

Ranchers overstocked their ranges, eager to recoup their losses. Cattle were in poor condition when the blizzards of 1882-83 came, and losses were even heavier than the previous winter. The abnormal blizzards during the winters of 1885-86 and 1886-87, coupled with a tightening of federal laws prohibiting fencing of public lands for pasture, was more adversity than most cattlemen could endure. Markets fell and steers selling for $30 to $35 in 1885 brought $5 to $10. Many large ranches folded. As for the settlers, the snow was just so much additional moisture for crops.

While the rainfall was generous and crops better than expected, the homesteader's life was far from easy. From the beginning, a shortage of traditional materials for fuel and shelter tested their ingenuity and tenacity. It is not difficult to imagine that the homesteader's solutions to these necessities of life were merely a refinement of the Indian's. In the beginning, buffalo chips were plentiful and provided adequate fuel for cooking and tak- ing the edge off frigid winter nights. With cattle on the range, a fuel later known as "Hereford Coal" soon replaced the buffalo's donations, and was collected for several weeks each fall and stacked in tidy ricks.

The absence of building material was overcome by undistinguished housing known as the dugout and the economical, if not always water-proof, sod house. In its most primitive form, the dugout was simply a hole in the side of a hill covered with canvas, a layer of brush and soil. The front wall was generally built of sod bricks with one window and a door. The price was right, though. According to one early writer from Ord, the itemized cost being: one window, $1.25; 18 feet of lumber for the door, $0.54; one latch and a pair of hinges, $0.50; one joint pipe to go through the roof, $0.30; and 3 pounds of nails, $0.19. The total cost for a standard 14 x 14-foot dugout was about $3.00. At that price the owner of the dugout had little right to complain when rains drove them from their home, or when a wagon or rider traveling at night fell through the roof.

Often, dugouts were only temporary housing until a more habitable sod house could be carved from the prairie. Suitable sod in the Sandhills was largely confined to river bottoms and wet meadows, sites where most homesteaders chose to establish anyway. The sod was generally cut by plow and sectioned off into pieces 3 inches deep, 12 inches wide and 3 feet long. A common building plan was a single room 16 x 20 feet, but soddies of several rooms and even two-stories were known. Most often the roof was constructed of sod over wood poles, but some affluent settlers managed shingled roofs. Fence posts from a neighboring ranch occasionally ended up on the roof of a sod house, leading to hard feelings if not repossession by the rightful owner.

The 1880's were the decade of the homesteader, but it tried and broke many of them. Living conditions and climate were not as hospitable as many of the eastern emigrants had anticipated. It was a hard, lonely life. Bachelors dreamt of mailorder brides or bided their time until a neighbor's daughter grew old enough to court. The life of a homesteader's wife was difficult if not unbearable. In Old Jules, Mari Sandoz describes the suffering:

"Early in January George Klein pushed 46 NEBRASKAland his team through the snow to Pine Ridge for wood. When he came home he found his house dark, the fire out, and his wife and three children dead-gopher poison and an old case knife worn to a point. The woman had been plodding and silent for a long time, but her husband had hoped for better crops, better times, when he could buy shoes for the children, curtains for the window, maybe a new dress for his wife and little luxuries like sugar now and then. If she could a had even a geranium. . , a neighbor woman said sorrowfully as she helped make white lawn dresses for the three children, something nice for their funeral. There'll be more killing themselves before long unless they get back to God's country, was the prediction. And it was true. One of two young Swedes who got lost in the sandhills came out completely crazy. His brother hung himself from a manger."

Without the railroads, the great boom of the 80/s might not have come. On the south, the Union Pacific provided a shipping point for cattle as early as the late 1860's. The Chicago and Northwestern Railroad pushed through the northern sandhills, crossed a high bridge over the Niobrara River and rolled into Valentine in the spring of 1883. According to Yost, a newcomer climbing down from that first train would have seen. . . "Three tents, five saloons, two general stores, a hotel and restaurant, the land office and a dozen shacks ... and when a flock of cowboys rode yelling and shooting down the street he would have bought a ticket right out again-except that he'd already spent every cent he had to get there. . . ."

Cattle ranches on the Loups and Dismal were still hundreds of miles from a shipping point in the mid 1880's. Finally, spurred by the likelihood that the Union Pacific might slice through the heart of the Sandhills, the Burlington started laying track northwest out of Grand Island. By 1886 they were at Broken Bow, by December at Anselmo, to Whitman in 1887 and by the end of January, 1888: "The Burlington burst through the Sandhills, brushed the sand from its locomotive headlight, combed the cactus from its cow-catcher, drove Grand Lake and Bronco Lake from the map and founded Alliance-city of the high plains."

THE 1880'S HAD BEEN far kinder to the homesteaders than ranchers. Many old cattle barons were forced out of business by the harsh winters; others, worn by the seemingly hopeless battle against the plow and the fence, simply pulled up stakes and moved to open range in Montana and Wyoming. Ranchers that survived were a new breed, running cattle on fenced range with winter feeding.

Spirits were high among homesteaders at the turn of the decade. Better stock was coming into the hills, frame houses and ample barns were going up, mostly by the good will of banks. Then the drought began in the spring and summer of 1890 and continued, unabated, through 1894. It crushed the dreamers. 'The drouth exceeded all probability," Sandoz wrote. "Corn did not sprout. On the hard-land fringe the buffalo grass was started and browned before the first of May. Even lighter soil south of the (Niobrara) river produced nothing. The sandhills greened only in strips where the water-logged sand cropped out. The lake beds whitened and cracked in rhythmical patterns. Grouse were scarce and dark-fleshed. Rabbits grew thin and wild and coyotes emboldened. Covered wagons like gaunt-ribbed, gray animals, moved eastward, the occupants often becoming public charges along the way." The strain was more than most homesteaders could endure. Soddies fell into ruin and sunflowers reclaimed the small patches of corn and potatoes.

With the settlers gone, the ranches grew; eastern and English money behind many of them. The price of cattle climbed in the late 1890/s and 40's, 80's and quarter sections could be bought up cheap from the fleeing homesteaders. Bartlett Richards moved back into the Sandhills with thousands of cattle, built the town of Ellsworth and ran cattle on government land, his range 60 miles long and 40 miles wide. The Standard Cattle Company, the famous 101 Ranch, moved onto the North Loup with 25,000 cattle and hundreds of miles of fence. The third big outfit, the UBI, managed by an Episcopal clergyman with British backing, moved into Hooker County with its range extending from the Dismal River on the south to the Middle Loup on the north. By 1900 the Sandhills was again in the hands of cattlemen, most of it illegally fenced public land. (Continued)