NEBRASKAland

March 1977 60 Cents

NEBRASKAland

VOL. 55 / NO. 3 / MARCH 1977 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Sixty cents per copy. Subscription rates $5 for one year, $9 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. commission Chairman: Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 Vice Chairman: Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-Central District, (308) 745-1694 2nd Vice Chairman: Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-Central District, (308) 452-3800 H. B. "Tod" Kuntzelman, North Platte Southwest District, (308) 532-2982 Richard W. Nisley, Roca Southeast District, (402) 782-6850 Director: Eugene T. Mahoney Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, jr. Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: Jon Farrar, Ken Bouc, Bill McClurg Contributing Editors: Bob Grier, Faye Musil, Tim Hergenrader, Roland Hoffman, Butch Isom, Ben Schole Art Director: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1977. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska Contents FEATURES FIRST TIME FOR TURKEY 6 FONTENELLE FOREST A GROWING DREAM 8 VISION ON THE WATER 16 CANOEING NEBRASKA WATERS 18 Missouri 22 Elkhorn 24 Cedar 25 Calamus 26 Big Blue 27 Niobrara 28 Republican 30 Platte 31 Dismal 32 AN IMPULSE 35 THE HIGH COUNTRY 36 ADVENTURES WITH WHISKERS A Fun House 42 DEPARTMENTS SPEAK UP TRADING POST 4 49 COVER: Backlit by the fading rays of a late afternoon, August sun, avid canoeists Dennis and Margie Bahr of Hastings enjoy a leisurely float on the Republican River near Franklin. Photo by Bill McClurg. OPPOSITE: Most Sandhill cranes leave their shallow-water roosts on the Platte River early, usually before sunrise, and don't return until sundown. The graceful sweep of the crane's outsized feather leaves little guesswork as to where they have been, however. Photo by Jon Farrar.

Speak Up

Ducks GaloreSir / The November issue of NEBRASKA land is outstanding for its coverage of waterfowl. Every person who even looks at this issue should be moved by it, and understand the absolute necessity to save our remaining wetlands across the North American continent. I especially like the individual pictures of ducks. NEBRASKA land is a better magazine than Sports Afield, Outdoor Life and Field and Stream. I would like to buy 20 to 30 issues.

Douglas R. La Fleur Onalaska, Wise. Early Days RecalledSir / I am writing because I like your magazine. I was born in a sod house in 1893. I saw many changes in the game population and in game laws.

I remember when prairie chickens were hunted for the market. I remember when they had spring shooting for ducks. I am enclosing a picture which was taken in 1904. Second from the left is Gunter Smith, and the two on the right are Jim Weaverling and Bert Woods.

I also remember when Goose Lake was full of pickerel, and on Sunday it was always exciting to see some of the fish ermen pull in their 300-foot nets. I was perhaps one of the first to help distribute pheasants in northern Nebraska. I had an uncle who raised them from 1912 to 1918.I also saw when the pheasants were so plentiful that they would dig out the seed corn as fast as you planted it, and the Game Commission gave farmers per mission to shoot them, but you had to leave them lay.

I disagree with the Game Commission that the raccoon needs protection. My grandchildren had a pet raccoon at differ ent times, and it did not take long for them to know what it meant when they heard a hen cackle. And when they got full grown, they would not wait for a hen to lay an egg—they started to eat the hens. I can name dozens of people who had their brooder houses raided in daytime by raccoons.

I think farmers or ranchers should have the right to go out at night with a spotlight on his own land and hunt them to protect his chickens.

I think the Game Commission should urge all hunters not to use the jack rabbit for target practice. They are almost extinct. When we had plenty of jack rabbits, we had a lot of pheasants. They always produced food for the coyote.

Fred Schindler Neligh, Nebr.Raccoons were not actually placed on the game animal list in order to protect them needlessly. We just feel that all wild animals need some degree of management. Landowners may still take them, regardless of seasons, etc., on their own land if they are causing damage. This is true of any predator, and is designed to give recourse for troublesome animals. Raccoons are strange creatures, and they can become more than nuisances. As the market value is up on their pelts, perhaps their numbers will be cut down somewhat. They doubt less destroy numerous pheasant nests in the spring, along with chickens. Still, it is best to harvest them when the pelts are useful, rather than merely destroying them. (Editor)

Save the PlumsSir / In your beautiful July issue, "Wild about Berries" was very interesting. I have the same ideas about planting things that our wildlife can live on, and humans also can use. It is too bad that things growing along roads and highways are either cut down or dozed out.

Have you ever seen the huge web bunches that contain hundreds of large worms, in our wild plum bushes? They have destroyed all leaves and fruit, every year for many years now. Does anyone know what to do about them? It would seem that eventually they will kill the plum bushes.

Wild plums make the best jelly and our wildlife would have more food.

Mrs. Ben Mlady Verdigre, Nebr.I hope that we can continue to encourage other people to believe as we do. As for those web worms-they can be a serious problem. Although also hard on the bushes, a small fire applied to the bag of worms is quite effective, especially if done before the worms slip out to start eating. Chemicals are tricky to apply, as the worms are protected by the bag. You might check with the local county extension office for other suggestions. And, thanks for your interest and keep after other folks to push for planting of wild fruits and berries. (Editor)

Following is a poem done by N.E. "Dode" Crawford in 7960 shortly after completion of Burchard Lake, which tells of his appre ciation. Mr. Crawford is now 90 years of age, and a sportsman still. (Editor) An Ode Ours is no secret organization Our aim is for the good of all We meet in the spring and the sum mer, As well as the winter and fall. Our creed is Woods, Water and Wild life, Aid and help in the restoration of soil, We want to fish and hunt in accor- dance with law, And for the safeguards of health we would toil. With regard to the property of others Our pledge is especially clear The God-given natural resources Are all to us very dear. In the early days of our organization, Three sportsmen, Louis Findeis, Sam Parks and Earl Cooke Took a stroll over our great prairies And gave them a demonstrative look. Their dreams have been amply re- warded Twas very hard to conceive Their visions and dreams so far-fetched, So very hard to believe. Seven and one-half miles west of Pawnee City And three and one-half miles to your right, Visions of theirs and the Sportsman's Club members, Gloriously come to your sight. It is an embankment high and wide And covered with Nature's blest sod, It stretches far from hill to hill And impounds great waters—thank God. It is yours and ours for recreation, A place of relaxation and rest, The beautiful hills and valleys, Blend in splendor to the west. The Pawnee County Sportsman's Club welcomes you, In all that we undertake, And we thank you one and all 1000 times, For the beautiful Burchard Lake.NEBRASKAland Magazine invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to Speak Up. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters. — Editor.

Four lawmen decide to try spring gobbler hunting in the Pine Ridge. "This is a real learning experience", said one between gasps after climbing one of many ridges nearly memorized during trip

A First Time for Turkey

AMONG SPORTS FANS, there is always speculation as to what play ers discuss when they confer at the pitching mound or along the sidelines. And, there is probably similar speculation as to what law enforcement people talk about when they get to gether for a confab.

At least part of the time, sporting activities are on the agenda. A couple of months prior to the 1976 spring turkey hunt, at least, several officers from the York area were socializing and the subject of turkeys came up.

Included in the discussion were Ken Adkisson, a conservation officer with the Game and Parks Commission, Dean Heiden, chief deputy in the York County sheriffs office, John Adler and Joe Kuzelka, state patrolmen from York, and Dale Radcliff, a patrolman from Aurora. And, whenever hunting and fishing are concerned, their plans usually include Roman Liekhus, a patrolman stationed at Lincoln.

Initial plans at that session were for the officers to form a spring turkey hunt in the O'Neill area, since Adkisson was formerly stationed there. But, he found that he was unable to take part, so the other five officers sent per mit applications in for the Crawford area, since another officer from Grand Island had access to land on his father's ranch.

Of the five applications, only one was not filled. Dale Radcliff, a brother in-law to Dean Heiden, was pulled out in the drawing. But, he decided to accompany the hunters and fill the time fishing for trout.

Work schedules for officers being somewhat staggered, it was not until 1 a.m. on Monday, the second week of the season, that they could depart, and it was shortly before noon Crawford time that they arrived and began arranging for a scouting foray.

As none of the five had ever hunted turkeys, they went out with their rancher "contact" to look over the land and get some tips on stalking the wily gobbler. They even worked the turkey call, but got no responses. Much wildlife was in evidence, in cluding antelope where even the rancher had not seen them before, deer, coyotes, and a turkey vulture.

"Boy, when we came around a bend and saw that vulture, we thought we had hit pay dirt. It was a big black bird with an ugly head, and that seemed like a turkey".

But, things weren't going to be that easy. In fact, hunting until quitting time produced no sign of turkeys nor any more look-alikes.

As the officers had been told to contact the local conservation officer, Cecil Avey, that was their next step. And, Avey offered to point them in the right direction if they were willing to be up and afield early enough.

Agreeing to his conditions before realizing what that meant, the hunters found themselves mulling over coffee about 4 a.m. the next morning. Shortly after, they were en route to the top of a butte still in pitch blackness.

"Cecil explained what we should do," Joe said, then told us to head out, always going downhill so that we wouldn't get lost. Just for fun, he gave a couple scratches on his turkey call.

"It was calm that morning, not a breath of air moving, and as soon as he quit scratching, there were calls from all over. Talk about excitement we went from sleepy to anxious right now," said Joe Kuzelka.

"I don't know how many there were, but they came from every where", added John. "We decided we would pair off, Dean and I going one direction and Joe and Roman another. Dale was up there with us, but he was going to go back down with Cecil and go fishing. Cecil told us it was all downhill, but quite a ways to where Dale would pick us up later. I suppose it was about six miles."

"The plan of attack," Joe offered, "was to go into the trees a ways, pick out a good spot and call. The turkeys were supposed to come to us and we would shoot 'em.

"Cecil said the turkeys would probably be in the trees yet, but about sunup they would come out. Roman and I started sneaking along, we didn't even call any more because we wanted to find a place to hide first. We didn't want those turkeys to come in when we were standing out in the open.

"We no more than got into the trees-we must have walked right under the trees they were roosting in when all of a sudden there were turkeys all over us. The wings flapping and noise-l just stood there gawking not knowing what to do. It was too early to hunt and still too dark to see much. I guess being the hunters we are, we just went right to the game. It was a learning experience, I'll tell you".

While Joe and Roman went almost straight east, Dean and John went south. They decided only one should call, so Dean handled the noise box. They got an answer to a call only about 50 yards from where they started, and tried to pinpoint it. "Dean started to call and one answered, and we thought it was pretty close, but pretty soon another answered, appar ently a lot closer. We figured the turkey was probably about 100 yards or so, and what we did was get down behind one of the ridges and were as quiet as possible. We did pretty good—we weren't making any noise at all except for the heavy breathing. Boy, going up and down those hills is tough.

"Anyway, we thought this one gobbler was probably about 100 yards yet, so we thought we would go on. We'd circle around, crawling back down the ridge, away from the turkey, and go around the whole ridge. We didn't want to go over the top, thinking he might be right over. Well, we did this for three or four ridges, probably about a quarter of a mile, all the time thinking that gobbler had to be be hind each one. Finally we got to this one and it was a real good spot. There was brush and stuff, right at the top, so we decided this had to be the spot. We got down out of sight, and all the time Dean was calling about every 15 minutes or so, and the torn kept right on answering every time.

"This whole thing took about a half hour and it was just about shooting time. Well, we got all ready and Dean hit that squawker and geez, you know those birds are so loud, we thought it must only be about 20 feet away. We really didn't know what to do at that point-whether to jump him or let him come on in.

"We didn't know it at the time but he must have been up in one of those dead pine trees. He must have been way at the top, and then decided to check on that hen. Well, when he went down to the ground, instead of being almost level with us, he dropped down into the canyon, and the sound of his call was altogether different. It sounded like we must have spooked him and he was going away. He just sounded a lot farther away." (Continued on page 45)

Fontenelle Forest

A Growing Dream

FONTENELLE FOREST Nature Center in Bellevue is an assembling point for many thousands of nature-loving Nebraskans and lowans. In 1912, far-sighted individuals from the Omaha metropolitan area began the gradual process of purchasing land which has now culminated in a 1,300-acre wildlife sanctuary and environmental education area. The Forest, although now nearly completely surrounded by suburbia, is kept in its natural state, thus preserving a unique area for the benefit of future genera tions. The entire growth of the Forest and development of its nature center has been supported exclusively by private funding. The Fontenelle Forest (Continued on page 15)

(Continued from page 8) Association, a non-profit corporation composed of business and professional people from the region, generates revenue through an annual fund drive, admission fees, and a modest endowment.

Six full-time and 7 part-time staff combine forces with more than 100 volunteers to offer one of the broadest nature center programs in the nation. These programs in clude approximately five outdoor education leadership training workshops each year for teachers and camping leaders, a naturalist trainee program with regional universities, natural science and ecology camping sessions for youngsters, youth natural science clubs, youth conservation work projects, short courses for adults, ranging from organic gardening to nature photography, field trips, lectures, guided hikes, and an environmental education program that serves 20,000 youngsters in more than 7 school districts.

More than 17 miles of marked hiking trails are open to the public 362 days each year. To the botanist and ornithologist, as well as artists and photographers, the Forest is a veritable paradise. Nearly 200 species of birds can be seen at various times of the year, along with 40 kinds of trees. These are located on ridges, slopes and valleys which are sheltered from the drying prairie winds. Seeping springs at the base of each ridge pour into a number of slow-flow ing streams, which jn turn contribute to one of the last re maining springfed marshes in the region.

The unique site, on flat, floodplain forest land, and the extensive programs offered at the center, have brought Fontenelle Forest designation as a National Natural Area by the Society of American Foresters; a National Natural History Landmark by the U.S. Department of the Interior; and a National Recreational Trail by the U.S. Bureau of Outdoor Education.

Leaders of the Fontenelle Forest Association, strongly preservation-minded, plan no management projects other MARCH 1977 than to offset the effects of use by visitors. In its efforts to preserve natural lands, the system's private enterprise with community participation has provided a feasible alternative to public ownership, and demonstrated that wilder ness areas are still treasured by many, and also that they can exist even irT the midst of urban areas.

Kept in its natural state, the Forest provides a place where one can recapture the perspective of man's relationship to nature. Time here is counted in eons, rather than in frantic minutes. It is a place for relaxation, quiet contemplation, and of inspiration.

Although there are many virgin tracts within Fontenelle Forest, the stream is an artifact of man. It was created by a dredge to serve as a Boy Scout canoe canal from old Camp Gifford, the remains of which have long since been reclaimed by nature. Jack-in-the-pulpit, bittersweet and jewelwood intersperse themselves along each side of this classic example of wilderness lost—regained.

Named for Logan Fontenelle, the Forest actually contains his last mortal remains, as he was buried within the confines of the Forest by the Omaha Indian tribe before the Civil War. The elder Fontenelle, Logan's father, operated a trading post, one of the first in this part of the fron tier, which is also believed to be located in the Forest. Many are the ties with history, as the walking trails pass sites of Indian earth lodges, which are still evident as depressions in the crests of ridges.

An interpretive center and offices are the focal points for all Nature Center activities, with live exhibits of plants and animals plus geological, geographical and historical displays. It is stressed that all formal activities at the Center have ecological emphasis showing the interrelationships between sunlight, water, air, soil, plants and animals. Perhaps this overview, or perspective, is the most important facet of the center, enabling even the most casual visitor to earn while enjoying the sights of nature.

A routine tenting trip to the Sandhills for research turns out to have eerie overtones when spirits of the past explain lake life

VISION ON THE WATER

CAMPING, FOR SCOTT LIVINGSTON, had always been an extremely satisfying experience; until now. But, it seemed like the only thing this trip to the Sandhills would bring him was frustration. He looked across the lake to the west. The day had run its course fruitlessly, and the sun was coming ever nearer the endless green horizon of rolling hills. He judged, maybe 15 or 20 minutes of good light left. With a sigh of defeat he tossed his notebook and pencil aside and strode over to the tent where his specimens and samples lay in disarray on the sleeping bag. He was nearly ready to concede that he might never get his paper finished.

Trying to take his mind off the problem, he busied himself by putting away his finds for the day. The biology specimens and the plants went into the small jars of alcohol, while the rocks and soil samples belonged in the proper size plastic bags. A dual major in geology and wildlife management at the University, Scott had thought that a paper on the diversified flora and fauna of the Sandhills lakes would be just what he needed to clinch an "A" in honors class. But he had not selected an easy topic.

After the jars and the bags were stored securely in their surplus Army cases, Scott crawled to the back of the tent to get his copy of an official report that he had uncovered in his preliminary research. He brought it out into the light and read it again:

Subject: Survey of Animal and Plant Life In digenous to the Sandhills Region.

Findings: After a thorough examination of the life in many of the lakes and ponds all over the region, it was found that the many species and subspecies of plants and animals were not only uniform, but almost identical in the different lakes throughout the broad sandhills area. In all cases care was taken to insure that the lakes surveyed were in their natural state and free from the influence of man who settled in the area. Since there are only a very few lakes that are linked to one another by rivers or streams, and there is definitive geologic evidence to show that most of these lakes had never been connected by surface water of any kind; it makes the odds astronomical that the variety and the individual species of fish, protozoa, and water plants could have evolved to be nearly identical in each of these many hundreds of fresh water lakes.

The report was quite brief, but it stated the problem adequately. In all of his research, Scott could find no reason as to the undue uniformity of aquatic life in the area. He had hoped that he might venture a theory in his paper, but it seemed to be a mystery of nature that might very well remain so.

He held the report in his hands and contemplated his situation for a moment. Then the sounds of the crickets and the frogs reminded him that it was time to retire, and he decided to postpone his problems until morning. Since the clouds told of fair weather, and he needed to do some clear thinking, he decided to sleep in the open.

After he had readied camp for the night, Scott was finally able to crawl into the snug warmth of the sleeping bag and place the worries of his day behind him. The sun was now completely eclipsed by the grass-covered hill on the far side of the lake. He watched sleepily as the last of its ever waning red rays danced softly on the gentle swell of the water, until even they made off for the other side of the world. As bright as the day had been, it seemed to get dark all too suddenly at the start of an other night in the Sandhills. And, even though it was 16 NEBRASKAland nearly the last day of June, it would still get quite cool before the morning light.

Zipping down and freeing one arm from the cramped yet warm sleeping bag, he rolled over on his side and laid a large chunk of wood on the glowing embers of the campfire. The darting blue points of flame lept hungrily at the sun-dried log, and soon their hue had reddened as they grew ever larger in their satiety. Scott rolled clear over to a prone position. He always slept better that way. Before he closed his eyes he saw that the red glow of the fire reflected off the flat stones that he was using to keep the flames contained, and lit up the camp with the light of the dying sun.

He said softly to himself the prayer—the psalm he had learned to say as a child—'The Lord is my shepherd! I shall not want. . ." He slept.

. . . The stars were bright. The night was warm. Scott felt as if he were floating. It was exhilarating. He seemed to know things—things he had never known before. He was at another camp. It was an Indian camp. There were people, men and women and children, and they were wearing skins. Their faces were painted. They were all circled around a fire. They were waiting. A tall man with long dark hair and a full beard was standing by the fire. He was the chief. He spoke:

"I am called 'the brave one/ the killer of the great buffalo with only a rock and a sling of deer's hide. I am your leader. I speak to the great spirit of the waters. You are my people. We are all the people of the great spirit." He paused to give some food, that looked like bread, to several of the children in the circle. They ate raven ously.

"My people are hungry. My people are hungry because the waters are hungry. The great spirit has told me that we must feed the waters. Then the waters will bring forth life and the people will be hungry no more."

Then the leader signaled to some men who carried two big animal skin bags into the circle. One bag was full of water, and many little fish were swimming about in it. The other bag was smaller and held grasses and roots.

The people came forward to peer into the animal skin bags. Many were afraid, for this was big medicine. The brave one led them down to the water. He instructed the men to dump the fish into the lake, and the old men among the people chanted in the background. Then he scattered the grasses into the wind and threw the roots into the placid water. In the moonlight the people could see the fish as they swam about the shore and then out into deep water. The people were hungry. Many of them had wanted to eat the fish, but they dared not say so.

Then a coal was brought from the fire at the camp, and the brave one had a fire made by the edge of the water. He took up the flat stones he had brought from the white cliff and carved on them with a bone knife. He etched out fishes and turtles and flowers and grasses. When he was finished he said it was good, and he told the people to put the stones on the shore by the water. And then he spoke to the people.

We are the people chosen by the great spirit. We are the people who must feed the waters. This is good, but we must feed all the waters in the land as we fed the waters under this moon. The waters are many. And the people are many, but when the waters are fed, then shall the people be not hungry."

Then the leader made the people put out the fire, and told them to be quiet while he spoke words to the great spirit. He stretched out his hands above the waters. He spoke:

"The great spirit is my leader. I will be not hungry. He makes the green grasses grow soft beneath my feet. He takes me to where the gentle waters flow. He makes my spirit sing. He makes me do what is good for the great waters. Even when I am in places that are not of the people, I will see no bad spirits, because the great spirit is in the waters. And the waters are good for me. He feeds me even when the waters are not alive. He gives me many new skins. I have all that is good. Always will the great spirit be with me in my days by the waters. And always will I live by the waters of the great spirit. . . ."

When the morning light came, Scott woke to the sound of a curlew calling in the new day from his perch on a log by the shore. Out on the lake the mist was shrinking under the increasing glare of the early sun. Its warm rays were also clearing the fog of sleep from Scott's head, as he slipped out of the bag and stretched luxuriously. He felt great—and hungry.

In a few minutes the fresh morning air carried the savory scent of coffee, powdered eggs and bacon across the dew-washed plains. As Scott knelt by the campfire, he noted with growing interest that the stones he had gathered to restrain it were a rarity in this geographic area. And he practically jumped with the unrestrained joy of recognition when he turned one over and saw the faint outline of a fish on its grayish shale surface. There were drawings on many of the stones. In a gesture of some import that no one was present to see, he wadded up his copy of the report and tossed it lightly into the flames. Breakfast mattered little now. This will certainly be a productive day, he thought, as he headed off to find his discarded notebook.

CANOEING NEBRASKA WATERS

EACH YEAR THE pressures of our chaotic society mount. Our lifestyles become increas ingly complex, confining and dependent upon the comforts of a civilization more removed from the basic elements of life than any that preceded it.

The desire to escape has paralleled the spiraling pressures, and the opportunity has become more available as leisure time increases. For many, escape from the treadmill is found in the quiet hush of water against the side of a canoe, in the sweet labor of coursing a stream that has escaped the attention of all but a hunting bittern or whitetail doe leading her fawn through shoulder-high cordgrass for its first taste of water. Here, the imagination can feed a hungry soul. Indeed, who among us can resist the temptation to relive the days of early trappers and traders who traversed these same streams, or to contemplate the sight of a hundred thousand bison pouring down the banks of the Republican River and pounding across the parched plains for as far as the eye can see. For some, these ever-so-brief excursions are the food that sustains us through the stifling realities of a society in sensitive to the gentler side of life.

In the last decade, Americans suddenly realized that their lives had changed. With the clamor that accompanied the rise of an environmental conscience came a massive flow of urbanites to those few wild places that remained. When the fadish ness of the ecology movement passed, most returned to their cities and took up life as usual. But, many had tasted the delicate flavor of spring water, the aroma of a morning fire and felt the excite ment of venturing into untampered lands. A whole new generation of outdoorsmen was born. For most, public areas existed, but canoeists faced special problems. Where could they canoe in Nebraska? Access to the publicly owned rivers was largely locked up in private ownership. Camping areas simply did not exist along most of the state's streams. The following publication hopes to an swer that and other questions. It is by no means the final word on canoeing. Plans for the devel opment of several canoe trails, complete with public camp sites, are on the drawing boards. The success of these pilot projects, and addition of others, will ultimately be determined by the conduct of those among us that stand to benefit the most-Nebraska's canoeists.

CANOEING NEBRASKA WATERS

PART OF THE THRILL of canoeing is the adventure of traversing an unfamiliar stream. Nebraska is rich in waterways, with some 23,000 miles of streams and canals, most of which are navigable by canoe. The possibilities are endless, from short half day trips to the challenge of 500 miles of Platte River channels. Canoeists can select the stream tailored to their style: white water excitement of the Niobrara River or the more leisurely pace of the Republican and Elkhorn. Sandhills rolling endlessly to the horizon, pine-cloaked bluffs or riparian woodlands rich in bird and plant life are only three of many settings available to Nebraska canoeing enthusiasts.

Canoe trips on nine different rivers are detailed in this publication, but other segments and other rivers will lure the adventuresome bent on traveling new waters. Most streams in Nebraska are considered public domain, at least for non-consumptive uses such as canoeing. Stream beds and banks are almost entirely private land, though, and it is the responsibility of the canoeist to gain trespass rights before stopping to camp or picnic. Access to most streams is available at public road crossings, especially in the more devel oped portions of the state.

Lakes and reservoirs should not be over looked, especially by those interested in taking advantage of the state's best fishing opportunities. Most lakes are on public land, eliminating the necessity of locating landowners. Exploring small coves, head waters and tail waters via canoe can offer a new dimension to a familiar lake. Camp sites are generally close at hand. Special care should be taken when canoeing large lakes, with a keen eye kept on the horizon for approaching storms.

Canoeists desiring more detailed maps or maps of streams not illustrated in this publication can turn to several other state agencies for help.

General highway maps of each county are available from the Nebraska Department of Roads in one-half or one-quarter inch to the mile scale. Most Nebraska rivers are shown on these maps. Currently these maps cost 40 cents per county for the one-half-inch scale on 18 x 36-inch sheets, and 5 cents per county for one quarter-inch scale on 9 x 14-inch sheets. Maps may be ordered from the Nebraska Department of Roads, Information Section, post office box 94759, Lincoln, Ne braska 68509.

More detailed maps are available from the Conservation and Survey Division. These topographic maps show land relief, rivers, intermittent streams, buildings, wooded areas, roads and powerlines. Most of the state is available on approximately 18 x 22-inch sheets, each covering an area approximately 6 by 8 miles. Other portions of the state are available on 18 x 18-inch sheets that cover an area approximately 12 by 17 miles. The current cost for either map is $1.25 per copy. Maps may be or dered from the Conservation and Survey Division, University of Nebraska 68588. Orders should be accompanied either by the exact name of the map or the exact description of the map coverage desired.

Additional copies of this special "Canoeing Nebraska's Waters" are available from the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503.

When schedules are forgotten and one becomes immersed in ancient rhythms, one begins to live. Good canoeing!

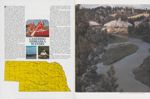

THE MISSOURI

THE MISSOURI RIVER is in contact with Nebraska for some 380 miles and is navigable by either power boat or canoe. Two segments, both unchannelized, are discussed below. Both can be quite challenging on days when southerly winds are high.

The first segment begins at Fort Randall Dam a few miles into South Dakota and ends at Niobrara, some 40 miles below. Public access to this reach of river is available only from either extreme: the upper end is accessible from a ramp some six miles into South Dakota immediately below Fort Randall Dam, and the lower end from the ramp at Bazille Creek near Niobrara.

The river in this area is wide and incredibly clear, having dropped its sediment load behind the dam, and contains many sandbars and small islands. Land conditions adjoining the river range from flat, farmed bottoms to high, vertical or rolling bluffs with drainages at 200 to 300-yard intervals. The larger islands and unfarmed riparian lands are generally heavily timbered and brushy. The Karl E. Mundt National Wildlife (eagle) Refuge is on the west side of the river on both sides of the state line, extending some three miles to the north and Va mile into Nebraska. Occasional cabins have been constructed in this reach, in addition to a larger development northeast of Verdel.

The second canoeing segment of approximately 50 miles extends from the Meridian Bridge (the only bi-level bridge spanning the Missouri) at Yankton, to Ponca State Park. Access is available from the Yankton bridge, Cedar County Park north of St. Helena and from a marina near Obert. This river has several large islands and many sandbars and is nearly as clear as the upper section below Ft. Randall Dam. Rush Island, just below Yankton, is about two miles long and is heavily wooded, and Goat Island near Wynot is somewhat larger and more densely vegetated. Numerous cabins are being constructed on this reach, most spotted individually where road access allows.

Topography adjoining this stretch is predominately flat but there are occasional vertical bluffs such as Rattlesnake and Volcano hills. The river bed is wider in this lower reach and the canoer can choose to pass through areas of marsh and emergent vegetation by taking the side opposite the main channel, or the slack water between an island and its nearest bank. Several such areas are in the vicinity of St. Helena and Audubon bends, and the mouths of the larger tributaries.

This lower segment is currently under consideration for possible inclusion in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers system as a National Recreation River. Identifying features and distances between each are as follows: Fort Randal! to Niobrara Segment:

Ramp below Ft. Randall Dam Karl E. Mundt NWR 2 m/7es; Nebraska State line 3 m/7es; ©Greenwood, SD. 8 miles; Chateau Creek, S.D. 75 m/7es; Ponca Creek, Nebraska 2 m/7es; Niobrara River 5 m/7es; Niobrara Ferry Landing SRA 3 m/7es. Meridian Bridge to Ponca State Park Segment: Rush Island 7 mile; James River, S.D. 3 m/7es; Cedar County Park, Nebr. (ramp) ... 2 m/7es; St. Helena Bend 4 m/7es; Audubon Bend, Bow Creek, Nebr. 5 m/7es; Coat Island, Marina-Nebr. side 7 m/7e; North Alabama Bend 3 miles; Vermillion River 6 miles; Volcano & Rattlesnake Hills, Nebr. 3 m/7es; 0Elk Point Bend 10 miles; Ponca State Park 4 m/7es.

THE ELKHORN

THE ELKHORN RIVER extends from near Bassett to its confluence with the Platte west of Gretna. Two segments are discussed below-one from West Point to Dead Timber State Recreation Area; the other from Highway 36 to Q Street about a mile north of the Douglas/Sarpy County line. The entire length of the river is subject to a wide range of flow variation caused primarily by snow melt, rainfall and irrigation demands in the upper reach. The greatest flows usually occur during the March through June or July period, and there is often adequate water in September and October. During low flow periods, even the channel lacks enough water to adequately float a canoe.

The segment from West Point to Dead Timber SRA is a distance of approximately 10 miles. The banks in this reach are lined primarily with wilow and cottonwood but occasional areas are cleared to the bank for cropland. Car bodies, intended to provide bank stabilization, are a common sight throughout this reach. The lower half generally has a greater flow due to additional water brought in by several small tributaries. Many reaches above and below this segment are equally canoeable.

The segment from Highway 36, near the Washington/Douglas County line, to Q Street is close to home for a great many Nebraskans and covers a distance of 15 miles. The upper two-thirds of this reach is characterized by flat topography and a willow-cottonwood succession of plant growth, while the lower third often runs between tall, steep bluffs containing cedar trees and hardwoods. Immediately below Highway 92 is an area of exposed sandstone bluffs. Below Highways 6 and 30A the canoer will frequently see development ranging from cabins to exclusive

THE CEDAR

THIS RIVER has its beginning in Garfield County north of Burwell and ends near Fullerton, where it joins forces with the Loup River. The segment of river considered here runs from the Highway 70 bridge west of Ericson, to Highway 281. Above Highway 91, very few public roads cross the river and access is difficult.

The two-mile segment between Highway 70, which offers easy access, and Lake Ericson provides a leisurely and scenic float. Banks are almost entirely tree-lined, with stands of cottonwood growing back from the river and heavy grass and smaller plants lining the shore. There is a diversity of wildlife to be seen, and the canoer feels rather remote even though close to a small town. Pools and backwaters make popular waterfowl habitat, and wood ducks and mallards may be observed, at least during spring and fall migrations. This beginning segment ends when the canoer encounters the northwest corner of 100-acre Lake Ericson.

From Lake Ericson, the water regains its river form when it leaves the lake near the southeast corner, where the charred remains of a small power generating plant can be seen.

After a short portage around the power plant, the canoer has 10 miles to enjoy before reaching Highway 281. The upper end of this segment may contain a logjam or two, and several fences will be encountered in addition to two bridges with adequate clearance, before reaching the highway. The upper end is quite heavily wooded with cottonwood, cedar and Russian olive while the lower portion has mainly grass and short vegetation. Banks wili range from high, nearly vertical cliffs to very flat and only slightly lower than the surrounding terrain.

It is in these areas of flat banks where one may come upon a cattle crossing and, if occupied, it is best to wait at a distance that will not panic the cattle. Two or three such crossings will be seen in this reach.

After passing through the first few miles of heavily timbered bank, the scene changes to a pastoral one, and farm buildings are almost constantly in sight as the river takes a typical crooked course. Trees in this lower reach are in spotted groves and the scenery, both close and in the distance, consists of rolling grassland. Identifying features and distance between each are as listed above.

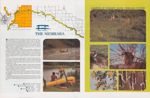

CALAMUS

THE CALAMUS begins its flow from Moon Lake in Brown County, and loses its name to the North Loup River where the two join near Burwell. The portion of the Calamus discussed here is the 16-mile segment upstream from the Highway 183 crossing.

River access points above Highway 183 are infrequent since there are few public road crossings. The closest public access to this particular reach is from a bridge over the river on the Rock/Loup county line. From this bridge the distance is approximately 24 miles to Highway 183. Another option, allowing a 7V2-mile float to Highway 183, begins at a ranch access bridge (public) located some 16 miles north of Taylor on Highway 183. Access to the river from private ranch roads requires permission from the landowner.

The river in the upper end of this segment is about 40 feet wide, clear, and generally treeless but lined with false indigo. The entire bank area is covered with vegetation ranging from small floating flowers to grasses and larger woody plants. Occasional breaks in this vegetation allow one to see rolling sandhills and grassland, the predominate land form, in the distance.

In this 16-mile segment the river flows adjacent to two ranchsteads and under three ranch access bridges. The first bridge provides support for a barbed wire which is probably high enough to be carefully floated under, but personal safety and respect for the landowner's property should be the primary considerations in judging when to portage. At least five other fences will be encountered before reaching Highway 183. A small power line crosses the river near the first bridge.

Toward the lower end of the segment, trees and tall grasses become more frequent. The river course is bounded by low rolling sandhills which are usually blocked from view by the heavy bank vegetation. Highway 183 traffic is occasionally visible and audible in this lower reach. Identifying features and dis tance between each are as follows:

Rock/Loup county line road Confluence with Bloody Creek ... 7 m/7es; Q Ranch access road (bridge) . . . 0.5 miles; 0 Ranch access road (bridge) & powerline ... 5 m/7es; Ranch access road (bridge) . . . 3.5 miles; Ranch access road (bridge) . . . 2.5 miles; 0 Highway 183 ... 5 m/7es.THE BIG BLUE

A 24-MILE portion of the Big Blue River discussed here extends from a bridge south of Crete on Main Street to a bridge east of DeWitt. The Blue, as all rivers in this part of the state, is subject to a wide range of flow variation depending primar ily upon rainfall and irrigation demands. During July and August the canoer will likely see and hear many pumps, mostly the portable variety, drawing water from the river.

A considerable amount of dead timber is found along this river. During the spring high water, these trees are often washed downstream until they meet an obstruction or become entangled with other trees. Most of these larger logjams are in the stretch above Crete, but several smaller ones are in the area below. There is nor mally room for a well-aimed canoe to pass through as rarely does the jam block the entire channel.

Vegetation along the Blue consists primarily of maple, oak and cottonwood in dense stands that limit visibility. The river is somewhat entrenched in its bed, and bank slopes are fairly steep, further limit ing visibility. Occasional areas of cleared cropland can be seen above the river. The banks and stream bottom change from soft mud in the upper end of the segment to sand, gravel and larger rocks toward the lower end. The entire length carries a high sediment load.

The Blue River is conveniently situated to provide close-to-home canoeing to residents of the state's second largest city. Although without the pristine nature of some of Nebraska's more remote rivers, the Big Blue allows a pleasant warm-up trip for the veteran canoer or a relaxing and scenic voyage for those wanting to try a new experience or sharpen rusty skills. Identifying features and distances be- tween each are as follows:

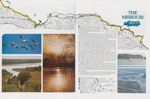

NIOBRARA

THE NIOBRARA RIVER has long been considered Nebraska's finest. A 120-mile portion of it, from western Cherry County to the headwaters of the proposed Norden Reservoir, has been under consideration for inclusion in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. The 22-mile segment discussed below includes the lower reach of that portion and ex tends beyond it to a point called Rocky Ford or Mill Dam. This segment begins northeast of Valentine where a bridge allows access to the Fort Niobrara National Wildlife Refuge.

Access to this segment is possible from four bridges, although roads leading up to three of them are unsurfaced trails. The entire segment can be canoed hurriedly in about six hours or leisurely over a two-day period. This variation in float time reduces the need to seek other access points to fit time schedules. The most frequently used put-in is from the upstream bridge which is on a gravel road within a quarter-mile of Highway 12.

The view from the river is spectacular as it winds through steep bluffs and canyons. Nearly all land within sight is wooded with both deciduous and evergreen varieties, except for the vertical cliffs which have been eroded away over the years. The bottom is hard, often rocky, and banks are generally of sand.

Smith Falls, Nebraska's highest waterfall, is about half-way between the Fort Bridge and Rocky Ford, and only a few hundred yards from the river. The Falls are on private property but a sign is usually posted by a very good-hearted landowner showing the location. A small, private cable car crosses the river at this point.

Flows in the Niobrara are not subject to extreme variation but are usually somewhat lower in late summer. During this time the river is generally navigable by canoe, but contact with large rocks under the surface is a possibility.

Lands along the river are in private ownership and permission to enter is required to avoid trespassing. Several commercial campsites exist along this stretch. Identifying features and distances between each are as follows:

GLIMPSES OF WILDLIFE ALONG NEBRASKA WATERS

THE GAME AND PARKS Commission is currently working with certain land owners on three rivers in an effort to provide public canoe-camping facilities of a primitive nature. A leased piece of land of approximately five acres, a simple sanitary facility and a picnic table, will hopefully be available at travel intervals of one day on the Platte River from Fremont to it's mouth; the Dismal River from Highway 97 to Dunning; and the Republican River from Harlan County Dam to the Guide Rock Diversion. It is anticipated at this time that some 170 miles of the 3 rivers will be opened to canoe-camping on a one-year trial basis by the spring of 1977.

Budgetary constraints limit the method of access to leases, and landowner apprehensions generally require an initial term not to exceed one year. This is a trial effort in the truest sense—if the arrangement proves favorable to both the canoer and landowner, the latter may elect to continue the agreement for an additional term; but if abuses of the arrangement be come common the landowner may terminate the lease. Responsibility for the success of this effort rests with those who will be canoeing the streams and camping on the sites provided. Adherence to posted regulations regarding fire, litter and trespass will be essential to maintaining favor able canoer-landowner relationships.

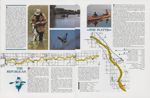

THE REPUBLICAN

DISCUSSED HERE is that segment of the Republican River extending from Harlan County Dam to the Guide Rock Diversion Dam, a distance of some 55 miles. Six county highway bridges allow convenient access to this reach, allowing for canoe trips ranging in length from three miles to the entire distance.

Adequate canoeing water can be expected only from late June or early July until late August or early September, in most years. During the remaining months, water is generally being stored in Harlan County Reservoir and upstream reservoirs for the next irrigation season. When irrigation water is needed, the Republican River channel is used to convey water the 55 miles to the Guide Rock Diversion Dam which feeds both the Superior and Courtland canals. Before and after irrigation season, flows in the river are reduced to a trickle unless exces sive rainfall or snow melt prematurely fill the reservoirs. Releases from Harlan County Dam must be in the vicinity of 250 to 300 cubic feet per second to adequately float a canoe. Current reports of water volume may be obtained by phoning the Corps of Engineers office in Republican City—area code 308, 799-2105.

This segment contains some relatively large and very scenic islands. Most of its 55 mile length is heavily wooded on both banks, primarily with willows and cotton wood, but many other varieties can also be seen in addition to a diversity of wildlife. Occasionally, areas of cropland can be seen from the river.

Bridges at Naponee, Bloomington, Frank lin, Riverton, Inavale and Red Cloud provide access to the river, in addition to a site immediately below the dam on the north side of the channel. This access allows the ca noer a wide range in trip lengths requiring float times of from two hours to four days. Lands along the Republican are for the most part privately owned and anyone consider ing a float where camping is involved should include asking permission of the landowner as part of his pre-trip planning. Identifying features and distances be tween each are as follows:

Access site below Harlan County Dam Naponee Bridge ... 5 m/7es; Bloomington Bridge ... 7 m/7es; Franklin Bridge ... 5 miles; Riverton Bridge . . . 72 m/7es; Inavale Bridge ... 6 miles; Red Cloud Bridge ...11 miles; Guide Rock Diversion Dam . . . 10 miles

THE PLATTE

THE PORTION OF THE Lower Platte from Fremont to the river's mouth at Plattsmouth offers good canoeing during the spring and fall. Flows in the June-through-September period are generally about 25 to 50 percent of what they are during the remaining months, necessitating some walking and dragging in addition to the more enjoyable floating.

Access to this 55-mile segment is available from 5 highway bridges and 3 state-owned areas. Highways 77 at Fremont, 64 near Leshara, 30-A near Yutan, 6 near Ashland and 50 at Louisville, plus the Two Rivers State Recreation Area, the Schramm/Gretna complex and Louisville State Recreation Area, are situated where they can be used to provide a wide variety of put-in and take-out points and overnight camping sites. Camping fees are charged at Two Rivers and Louisville.

This portion of the Platte flows through a variety of land uses and this diversity is evident in almost every segment throughout the 55-mile reach. The canoer will traverse some areas that appear very remote, being heavily wooded on both sides with no cabins or other developments in sight. Other areas will be primarily in cropland. Still others will show cabin development to one degree or another, some singly and some in clusters. The canoer should be aware of the Nebraska National Guard Camp between the Platte/Elkhorn confluence and Highway 6, where the firing range is used periodically thoughout the year. An earthern structure provides a range backstop, plus safety measures require that red flags be visible from the river whenever the range is in use.

The islands in this stretch are a noteworthy feature. Most are covered with vegetation and some contain willows and large trees. Deer tracks are a common sight on the larger islands, and the ob- servant canoer will no doubt see trails going down to the water, as the deer move easily between islands and the mainland. Beaver and muskrat and their signs can also be seen here, and a fall trip is sure to offer the sight of waterfowl.

THE DISMAL

THE DISMAL RIVER is a scenic Sandhills stream with a flow that is nearly constant throughout the year. The north and south forks of the Dismal join immediately east of Highway 97, south of Mullen. The segment discussed below consists of the 58 miles from Highway 97 to Dunning; requiring three or four days to float.

Before the confluence, each fork of the river is approximately 10 feet wide; after joining the width is somewhat greater and the channel is deeper. The upper extremes contain cold water which supports a trout fishery, while the lower reaches are warm water and harbor catfish. Banks are of a sandy soil for the most part, and range from gently sloping, offering vistas of distant, hilly grass land, to steep, vertical bluffs wooded with cedars. The predominant land use seen from the river is agricultural; that of range feeding of cattle.

Access to this 58-mile stretch is limited. Only two paved highways, Highway 97 south of Mullen and Highway 83 south of Thedford, provide the canoer a place to launch his craft. A county road some 13 miles south of Seneca also crosses the river, but only after a difficult and bumpy ride on a one-lane road that is only partially surfaced. One other access in the southeast corner of the Bessey Division of the Nebraska National Forest (Halsey) may be used to get on the last 11 miles.

The upper reach of the Dismal is confined between rugged hills and bluffs, making the water swift and of enough depth to easily float a canoe. As the river moves toward the east side of the forest, however, the surrounding topography allows it to become wider and slower and the channel here often becomes somewhat difficult to navigate.

The canoer will encounter numerous fences on the Dismal, required to keep neighbors' cattle separated and to allow them a place to water. Some of the fences have been marked with white flags, but a watchful eye and an awareness of this hazard, and its necessity to the ranch ing business, should be kept in mind. Good judgment will tell the canoer when he can pass under and when he should portage. Respect for the landowner's property should be a primary consideration. A damaged fence may mean a refusal the next time permission to camp is requested.

Lands adjacent to the Dismal River, as with all rivers in the state, are private property and permission is required to use them. A trip to the respective county courthouse to study plat maps and locate landowners is part of ca noe trip planning when trespass rights will be needed. Identifying features and distances between each are:

CANOEING ETHICS

CANOER-LANDOWNER relationships in Nebraska range from harmonious to explosive; and there is usually a reason for people feeling the way they do. Efforts by each group to understand the other, or to place themselves momentarily in the position of the other, would go a long way toward easing some of the discord that may exist. The motives of the canoer and the landowner for being in the same geographical location at a given moment are usually quite different, but an underlying common ground does exist-that of appreciation and respect for the physical re source. Both are basically protective of the resource, but the canoer is frequently a temporary visitor, perhaps spending a day or two away from more developed aspects of society, while the landowner has a vested interest in the land since he derives his livelihood from it.

Just as the local filling station operator is in business primarily to sell gas, so the agricultural landowner is in business to sell food. Both require certain facilities and equipment to carry on their business. Both want to protect their investment of money and time. And, neither can be expected to allow anyone to jeopardize that invest ment. The following discussion touches upon several factors that have an effect on the resource and the relationships of the people involved.

Canoe Trip PlanningOnce the canoer has decided which river he wants to experience, several other questions arise, such as time available for the trip, whether nights out will be neces sary or desired, whether to camp out or stay in a motel, and, if camping on the river, where to camp and how to go about getting permission. Good planning is essential to a successful outing, especially the arrangements made to secure permission to camp. Although this task may take considerable time and effort, and maybe a long distance call or two, it can be enjoyable.

If personal contacts in the county are not available, plat or ownership maps are a good source. These can usually be reviewed in the office of the county clerk of the county where landowner contact is needed. The landowner can then be contacted ahead by letter or phone to request permission or to arrange a personal visit.

The other option is to contact the land owner personally, allowing part or all of the day before the float for this activity. Some landowners may want to see a per son before granting permission; some may do this by letter or phone, and some may not grant permission at all. Whatever the result, respect his decision and select a new site if necessary.

Keep in mind that in Nebraska, contrary to some of our neighboring states, most stream beds and banks are privately owned. Requesting permission to enter someone else's property may take a little time and advance planning, but it's a mat ter of courtesy and a legal requirement that is often essential to an enjoyable trip.

Commercial outfitters will book trips for the canoer who desires such services, re lieving most of the worries of equipment and arrangements.

FencesNebraska landowners commonly fence across rivers to control cattle and allow them a place to drink, and to avoid having to fence parallel to the stream for great distances. In many parts of the state, especially the Sandhills, a broken fence may mean that a landowner and his neighbor will have to spend considerable time sort ing cattle. Some fences are high enough to be carefully floated under in a canoe, without damaging the fence or creating a personal safety hazard. Others may necessitate a short portage, but this can offer a welcome stretch from a period of canoe sitting. Nebraska law contains a provision allowing transport of nonpowered vessels around any fence or obstruction in a stream or river. The canoer is responsible for any damages to the fence or property.

FiresMany campers and canoers today use small backpacking stoves for their cooking. These have several obvious advantages over an open wood fire. One is that stoves reduce the threat of an uncontrolled fire feared by landowners in all parts of the state, especially during recent extremely dry years. Stoves burn their own fuel and don't require the user to forage and chop wood, the evidence of which becomes quite obvious after several users have camped at the same site. The stoves are easy to pack and carry, and some models involve only a small expense.

If a fire site is provided or a fire is necessary, it should be kept to a minimum size and be drowned completely (ashes cold to the touch) before being abandoned.

LitterLandowners and most outdoor enthusiasts share a common attitude toward lit tering. An awareness of the problem and its consequences will keep the canoer from being a contributor, and should cause him to make up for the thoughtless acts of the unconscious tew. Take along a leaf bag or two for your own refuse, and whenever possible retrieve that cigarette pack or candy wrapper that's been left by someone else. Unless you encounter a designated trash receptacle, take the bag home for proper disposal. The bag and its contents will take up very little room in a canoe. Smoking should be done only in camp and at rest stops, not while traveling. Cigarette filters should be handled as other litter.

Burying garbage is rarely a suitable practice. The scent of food residue may cause animals to unearth the pit. The disruption of digging a garbage pit could later cause a sizeable blowout, especially in the Sand hills where grass cover is essential to hold ing loose soil.

CourtesyConsideration for other canoeists and the landowner will result in a more pleas ant experience for all. Radios are best left at home, as your fellow camper 50 yards away may be trying to escape just such noises. Other unnecessary noise may spoil a trip for someone else.

CANOEING TIPS

Here are a few suggestions to help make your canoe trip a success:

1. Be familiar with your equipment and possess some knowledge of canoeing.

2. Pre-departure planning can be fun and may save many pounds of unnecessary gear, and will ensure having everything necessary for safety and comfort.

3. Know, understand and practice the spirit of the law. Get permission before you camp on private property and be sure your canoe is properly equipped with life jackets. Nebraska law requires a life preserver for each occupant of the canoe.

4. Respect the rights of others and main tain high standards of thoughtfulness and courtesy. Leave the campsite clean and the owner's property undamaged. Do not leave a trail, but rather an example for others to follow.

5. Be careful with fire. Use only small fires made from dead, dry wood. Use fire places when available, or utilize bare earth or sandbars instead of killing grass or other vegetation. Make certain all fires are "drowned out" before leaving them.

6. If traveling with a group, organize. One of the objectives of canoeing is to provide an enjoyable experience. Be sure each individual knows his responsibilities.

7. Don't try to rough it. The knowledge able canoeist takes and uses whatever he needs to keep himself comfortable.

AN IMPULSE

IT WAS ONE of those hot, humid days that are so common in the sum mer along the river. I was sitting on the porch of our cabin just watching the smoke lie like a blanket waiting for a breath of air so it could surge upward. It was peaceful though, and I was en joying the solitude.

I don't know how long I had sat there, as time seems always quickly to sneak away, but I do know that the sun was losing itself behind the trees. I looked up to see Jake walking down the crooked path. No one really knew very much about him. He was a tall lean man with a seasoned look of his 70 summers. He did not talk a great deal, but I liked his company. He had lived along the river those many years and feared nothing except the snakes that also inhabit the river. How lucky he was to have mastered the art of thoroughly enjoying life every day.

By now, he was about 50 yards from the cabin, carrying with him a stick which he continually poked along in the grass and occasionally used as an extra support, and as usual he was shouldering his shotgun. He was a true sportsman in the sense that he did not shoot anything for the sheer sport of showing his ability as a perfect marksman, but his livelihood de pended heavily on the wild game which roamed freely in the area. Across his head he wore a flashlight strapped in miner's fashion-so I knew right off that he was planning to gig frogs or maybe a lazy carp as soon as the sun had faded away.

I kept a wooden, flat-bottomed boat several hundred yards down stream which he used for fishing. Knowing this man and what his in tentions were. I grabbed my hat and soon was striding along with him, his long steps making it difficult for me to keep up with him.

By now it was almost dark. We pushed the boat into the water and before long were silently rowing along the edge of the river. He had already gigged several frogs and I knew he was planning on having frog legs for one of his meals. It was thrilling to watch him, with complete control of his gig at all times and rarely missing anything at which he aimed. How accurately he would use his light to spot his target, and with lightning speed make his aim good!

It was getting late as we rowed along the edge, hearing nothing but the rhythm of the oars as they splashed the water. Even that had a serene sound! I was almost dozing when Jake suddenly flashed his light around again-this time letting the beam fall directly in the boat. There, in the bot tom, lay a coiled water snake. Without hesitation, Jake picked up his shotgun and fired at the thing that frightened him most! I grabbed for my fishing rod, which I kept in the skiff, but the only thing that I can truly remember is a hole the size of a water bucket in the bottom of the boat, and both of us slipping down into the water, holding onto what was left of a fast-sinking boat!

It is said that no one should stifle an impulse . . But there are times!

THE HIGH COUNTRY

FOR SOME TIME I had wanted to return to northwest Nebraska and photograph the Toadstool Park and Pine Ridge areas. Last summer my wife and I were able to take some time off from our drug store in Fayette, Missouri and spend a short time in Crawford, Nebraska as guests of my mother-in-law, Mrs. Harold King.

Some years ago we had lived in Harrison, Nebraska where we owned a drug store. My wife, Maureen, is a native of Crawford, and we both loved that part of the state and were anxious and excited about returning and visiting with old friends. And, it gave me a chance to record on film the feelings I have for the area.

Toadstool Park is always a mystery to me. Each time I return I find an area that either I have previously overlooked or that nature has carved anew from the sandstone. I never know which it is. The quietness is overwhelming, as the only sound is that of the wind. The feeling of loneliness is everywhere.

As I climb the buttes and walk between the trees of the Pine Ridge, I have always been able to achieve a feeling of inner peace. There is always a sense of anticipation of what you might find over the next ridge. I love to hear the wind whistling through the pine needles and stopping to watch birds in flight or viewing a delicate wildflower which somehow seems out of place in this area of tall trees and towering buttes.

Later, after I have processed the film and made prints, I can look at them, and with a little imagination, can put myself back to the spot and feel and hear the things I felt when I was there. This, to me, is the meaning of my work.

36 NEBRASKAland MARCH 1977 37

Adventures with Whiskers

the prairie vole

WELCOME! WELCOME! Come one, come all to wild and wooly Whiskers fun house. Cast off your cares and push those stuffy books aside, we're here for the serious business of having fun. Helping the doe find her fawn shouldn't be too hard but wait until you try my crossword puzzle. It's a zinger. If you've got a riddle or just want to write and tell me a story about a plant or animal you know, send it to Whiskers, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebr. 68503. See you again in May.

HELP THE DOE FIND HER FAWNQ. What kind of fish would you catch in Lake McConaughy? A. Wet ones!

Q. What did the daisy say to the persistent honey bee? A. Buzz off!

Q. Why is an avocet like the letter R? A. It lives on the edge of water.

Q. What is 100 feet long and can hide under an oak leaf? A. A centipede.

Q. What is black, white and brown, and was billed twice for lunch? A. Two magpies eating a fudgesickle.

CLUSE ACROSS1. This rodent digs tunnels underground and rarely sees daylight

4. Rodents use their teeth for

5. A marsh rodent that swims

8. Whiskers is a prairie----------

9. A meadow vole is sometimes called a meadow----------

11. A rodent's coat

12. Most rodents are called------- because they come out at night

13. The family of rodents to which Whiskers belongs

15. A rodent that cuts down trees

19. A mouse that got its name from gathering grain

20. A grasshopper mouse eats

CLUES DOWN2. Often called a dog, this rodent lives in a town

3. A vole's tunnel in the grass is called a______

6. A mouse named after Nebraska's largest wild animal

7. This rodent has sharp quills and eats tree bark

10. A beaver eats it, a prairie dog says it

11. The______squirrel glides from tree to tree

14. All rodents have gnawing

16. An undesirable rodent brought here from Europe

17. Many rodents eat----------seeds

18. What Whiskers might do if he ate too many grass seeds

TEST YOUR R.Q. (RODENT QUOTIENT)Starter word: The name of whisker's family is Cricetid (Answers to puzzle on page 47)

FIRST TIME FOR TURKEY

(Continued from page 7)started sounding closer again, and closer yet. Dean wasn't even calling anymore we were just sitting there, and pretty soon we could hear him coming, gobbling al most all the time. We looked at each other, not knowing what to do, and finally Dean said to get ready. We were lying down and I had my gun ready, but he didn't come right at us, he was off to the right."

"He was right behind a fence," Dean added.

"I guess Dean and I saw him at the Dean started yelling 'Shoot, shoot', and there he was, 20 feet away. He was looking right at us, standing up as tall as he could, and his head was so ugly.

"When Dean yelled to shoot, those things are so quick, when I looked back he had gone from looking right at us to turn ing and boogying on down that hill. But, that bird was in the bag. I knocked him down, and Dean went right over that fence like it wasn't there."

"It took you two shots to get him, though", reminded Joe.

"I shot twice, but didn't have to—it was just to make sure," quipped John. "And it was a big turkey, 17 or 18 pounds. They get bigger than that, but for us that was big. Especially when we got it near where we started hunting and had to carry it all the way back down to the road. We took turns doing that."

"We could hear all the commotion over there," recalled Joe, "whooping and hol lering. I remember telling Roman that if there were any more turkeys around be fore, they would be gone now with all the fuss."

Since they figured any activity was over, Joe and Roman hurried over to meet with the other two hunters and to investigate their apparent success. After recounting details of the hunt, the quartet set off to rendezvous with Dale. More turkeys were seen on the way back, but always at such a distance that they seemed to offer little chance for a sneak. And, after about an hour or so, gobblers didn't respond to the call anymore.

A trip to town for supplies followed, then during midday a fishing expedition took their minds off hill climbing. That evening, however, it was back into the trees to the clearing where they had seen the big bunch that morning. Staying until sundown was only a courtesy, however, as they never saw nor heard a turkey.

Wednesday morning it was up again long before dawn for another go at the big birds from the top of the butte. As on the previous day, they were the only turkey hunters in evidence, so it seemed like a private hunting preserve. But, although they heard plenty of gobbler talk, they were never able to get close. The birds always seemed to be moving off as if spooky of something. Not long after hunt ing time, fog and drizzle blanketed the countryside, making it tough and uncomfortable to hunt. During the day it steadily got worse, so a motor trip north to the Black Hills was discussed and agreed upon. Hunters are tourists, too, it seems. But, it was even too foggy to see the scenery, and considerable ribbing was aimed at the originator of the idea to go sight seeing.

Bad weather continued to plague the group on Thursday, and it was suggested that they return home. Card playing seemed the order of the whole day, but Joe wanted to have another go at the birds, so John agreed to accompany him that afternoon despite unpleasant conditions. There was frost on the ground and it was cold when they reached higher elevation, but the birds seemed somewhat more responsive. They would at least an swer when spoken to.

Exercise seemed to be the most important ingredient, as the birds were moving but somewhat slowly.

"We sort of kept after them, although we wondered why," said Joe. "It was pretty much a losing battle as we never

Pre-Season Special

White Stag "Skyliner" Tent

sm5?; Special $179.95

• ( ION-037-SST ) - - WHITE STAG #20028

"Skyliner". Family tent. Cut floor size

12' x 9'. Sleeps 5-person with ease. Flame

retardant 8 oz. Destiny Cougar Cloth tent

canvas. Excellent cross-ventilation.

• Outside frame gives pole-free, 100%

usable interior. Sewed-in floor, four large

windows with screens and Zipper storm flaps.

Zipper, screened, Dutch type door. Reflecto

roof helps keep interior cool. Center height

8', height at outer walls 5'. (60 lbs. )

*This price good only thru March 31, 1977.

Electric Trolling Motor

Tte Pathfinder

Develops

15 lbs. Thrust

36" Shaft

Heavy Duty,

Chromed

Operates On

12-Volts,

5 ft. Cable

360 Degree

Rotation

Foot Operated

ON/OFF Switch

Rugged Bow Mount

With Patented "C"

Hold-Down Bracket

Regular Sale

$199.98

$179.95

3-Speed

Remote Control

BRAND NEW

1976 Model

MAIL ORDER CUSTOMERS - PLEASE READ

• Be sure to include enough money for

postage and insurance to avoid collection

fees. This saves you at least $1.35. We

refund any excess immediately. If you request

C.O.D. shipment you must remit at least 30%

of the total cost of your order. NEBRASKA

CUSTOMERS must include the NEBRASKA SALES

TAXI Also include the CITY TAX if you live in

Lincoln.

• To expedite your mail order be sure to

include the item number of each item ordered.

When you visit Lincoln, You'll find our retail

store at 1000 West "0" St. ( Phone

435-4366 ). Store hours 8:00AM to 5:30PM,

till 9:00PM, Thursdays.

SPECIAL SALE! Fishing Boat and Motor

Buy Them Both and

Get FREE Car Top

Carry Kit

• The LOWE "Little V" 12-foot, all-aluminum

boat is ideal for small and sheltered lake

fishing. Semi-V bow with welded and riveted

hull. Easily car topped too. Has 3 seats,

styrafoam flotation, 3 bottom keels. Weighs

only 83 lbs., will carry 430 lbs. Max. H.P.

rating 7 %.

List Price $254.50 $199.00

( ITEM #ON-037-AOM )

• The AERO air-cooled 4 horsepower

outboard is an ideal power mate for the

"Little V". Can be slow trolled. Very

economical operation. 1-cylinder, 2-cycle,

13:21 gear ratio. Weighs only 37 lbs.

List Price $279.00 $199.00

• You can purchase the boat or motor

separately at the sale prices shown. Buy the

combination and get a set of snap-on car top

carriers FREE. ( ITEM #ON-037-BMC )

WORTH Anchormate II

m

$27.99

( 8 lbs. )

• ( #ON-037-WAM ) - - Drop or haul in your

fishing boat anchor with one hand while you

are fishing. Ends the mess of tangled anchor

ropes in your boat, lets you drop anchor

instantly with just the turn of a button. Reel

stops when the anchor hits bottom.

• The new Anchormate II has added line

capacity, horizontal stowed anchor position

that keeps it from banging against the boat

and puts less strain on the bracket. Reduced

rope tension, non-slip action, heavy duty

brake and clutch springs. Very easy to mount.

LOWRANCE

Fish LO-K-TORS

Model

LFP-150

Complete

With

Trans-

ducer

$88.95

• ( ION-037-FL-B ) - - Portable unit

operates on two 6-volt lantern batteries ( not

furnished ). Folds into light weight carry case.

0 to 100 ft. depth scale. Automatic suppres-

sion system. Non-corrosive housing. ( 8 lbs. )

Model

LFP300-D

The

Improved

"Green Box"

Complete With

Transducer

$149.95

• ( ION-037-FL-A ) - - Latest model with

new 0-60 ft. and 0-100 ft. dual scale.

Completely portable. Operates on two 6-volt

lantern batteries ( not furnished ). Tempera-

ture compensated for ice fishing. ( 8 lbs. )

BY MAIL

OR IN OUR STORE

Use Your Mastercharge Or

Your BonkAmericard

• Your authorization signature on your order

plus your BAC or MC account number and

"Good Thru" date and your address is all we

need for mail orders. Be sure your information

is complete.

PENN Fishing Reels

• World famed, precision built PENN fishing

reels at lowest prices. Shpg. wt. 1 lb. each.

• ( ION-037-PR-A )

PENN Mod. 109-MS

$17.88

• ( #ON-037-PR-B )

PENN Mod. 9-MF

$18.99

• ( #ON-037-PR-C )

PENN Mod. 209-MS

$20.98

• ( ION-037-PR-D )

PENN Mod. 309-M

$24.95

• ( #ON-037-PR-E )

PENN Mod. 920

$29.99

PENN Reels Have 1-Year

"Limited" Guarantee

UMBB7

ZEBCO "Cardinal"

Open Face Spinning Reels

• Superbly smooth operating open face

spinning reels. Equipped with stainless steel

ballbearings. Shpg. wt. 12 oz. each.

• ( #ON-037-ZC3 )

ZEBCO CARDINAL 3

Ultra Light Freshwater

$29.88

• ( #ON-037-ZC4 )

ZEBCO CARDINAL 4

All-Purpose Freshwater

$25.99

• ( #ON-037-ZC6 )

ZEBCO CARDINAL 6

Heavy Freshwater

Light Saltwater

$29.88

• ( ION-037-ZC7 )

ZEBCO CARDINAL 7

Heavy Freshwater

Medium Saltwater