NEBRASKland

February 1977 60 Cents

NEBRASKAland

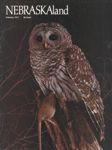

VOL 55 / NO. 2 / FEBRUARY 1977 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Sixty cents per copy. Subscription rates $5 for one year, $9 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. commission Chairman: Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 Vice Chairman: Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-Central District, (308) 745-1694 2nd Vice Chairman: Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-Central District, (308) 452-3800 H. B. "Tod" Kuntzelman, North Platte Southwest District, (308) 532-2982 Richard W. Nisley, Roca Southeast District, (402) 782-6850 Director: Eugene T. Mahoney Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, Jr. Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: Jon Farrar, Ken Bouc, Bill McClurg Contributing Editors: Bob Grier, Faye Musil, Tim Hergenrader, Roland Hoffman, Butch Isom, Ben Schole Art Director: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1977. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska Contents FEATURES THE GREAT CHICKEN VALLEY 8 GRETNA TO SCHRAMM...A HATCHERY CHANGES ROLES 10 THE SOUND OF WHISTLING WINGS 16 FOLLOWING THE HOUNDS 18 REFUGE FOR A JINX 20 GIFTS OF LAND 22 THE WATER'S EDGE 24 FISHING THE HABITAT PLAN 30 THE TIME AT THE CABIN 32 STILL THE GOOD OLD DAYS 34 ADVENTURES WITH WHISKERS WHO EATS WHO 38 DEPARTMENTS SPEAK UP 4 TRADING POST 49 COVER: A resident of Nebraska only on a limited scale, the barred owl restricts itself to the deciduous woods of the eastern part of the state. Although no sightings have been made in winter, they are known to live and nest here during the other three seasons. Photo by Greg Beaumont. OPPOSITE: Often, shapes taken for granted or ignored at other seasons become outstanding in the sharp cold of winter. Photo by Lou Ell.Speak Up

Snug on IceSir / With all the ice fishing in Nebraska, someone might appreciate my idea for a foot and hand warmer (at least if over age 70).

Cut off a 15-gallon oil drum to a height of 15 inches. Drill two holes somewhat off to the edge, 10 inches from the bottom. Insert a steel rod through these holes, which will support yourYeet. Place a gallon pail with charcoal in the bottom to furnish heat. You will be surprised how quickly one can warm both hands and feet. A perforated pail allows faster burn ing of the charcoal. And, a 5-gallon metal pail may be used in place of the drum, but it is not large enough to serve as a foot warmer.

Donald Fox Kearney, Nebr.Some of us might even leave the drum whole so that we could sort of stand in it and fish through a hole in the side. Thanks for the idea. (Editor)

Death DealerSir / Here's something that should be talked about. It's killing our fishing in the river. Damage from road salt is nearly $3 billion a year when it is spread on roads to melt snow. The total damage would be even higher if the potential health hazards were included, researchers say. A study shows the destruction caused by salt is nearly 15 times greater than the cost of applying it, and 6 times the entire national budget for snow and ice removal. The cost of actual damage to vehicles, highways, utilities and vegetation is immense. Most of the damage was rust on cars and trucks; then to water supplies, trees, and utilities. Heavy salt use also upsets the natural ecological balance, causing more damage, and adding the risk of increased hypertension from the heightened levels of sodium in water supplies.

I have been saying that salt does dam age for years. Last year I fished five rivers in Iowa and did not even loose my bait.

Glen Pool Omaha, Nebr. From Down UnderSir / Congratulations on your magnificent production, "Portrait of the Plains", to commemorate your country's 200th birth day. I receive NEBRASKAland regularly through the courtesy of Mr. and Mrs. For rest Jaeger of Nebraska, and it is read with appreciation by myself, my family and friends.

We are in the season of winter (June let ter) but I live on the east coast and am able to surf regularly at Bondi Beach. It was on Bondi that we first met young Dan Jaeger, who was then serving with the Navy.

Through NEBRASKAland I have come to appreciate the beauty of your state. And, the articles and photos are most informative.

Bill Jenkings Sydney, NSW, AustraliaYour seasons may be backward, but you're our kind of people. Thanks for the letter and kind words. (Editor)

Memory RaiserSir / I receive NEBRASKAland as a gift, in cluding your book, "Portrait of the Plains", and find it beautiful. I was born and raised and lived near Bellwood until 1937 when I came to California to live. Even living away from Nebraska all those years, Nebraska is still my home. The book brings back so many memories which I cherish and I am enjoying it more than I can say. I want to say thanks again for such lovely and delightful reading and the pictures are gorgeous.

Mrs. Hayek Los Angeles, Calif.You are certainly welcome, and I hope we can continue to bring back memories for many more years. (Editor)

Issue TakerSir / I must take issue with the Wildlife Habitat Law LB 861 passed by the Legislature. The law provides for wildlife habitat and maintaining hunting areas open to the public. The increase in hunting, fishing and habitat fees could be of no value to wildlife as hunting pressure would leave little left to propogate.

I believe the answer would be to shorten the season enough so that wildlife could have a reasonable chance to multiply.

Reinhold Ernst Duncan, Nebr.Wildlife, just like people, will take care of multiplying if all conditions for survival are right. Normally, wildlife needs only adequate habitat to easily maintain itself, es pecially with modern, managed hunting harvests. Hunting pressure becomes a problem only when the amount of land open becomes scarce—then you concentrate hunters on less area. If all land was open, there would be no problem, except for near large population centers. Anything we can do to improve habitat helps all the way around, and the habitat plan is only one of many efforts which must be under taken. (Editor)

Dam ProjectsSir / I always read with great interest your magazine from cover to cover and feel it is a great asset to our state. I would like to comment on several things in a recent is sue (June 1976). First of all, I couldn't help but notice the letters from readers who mention things which could be done in our state from producing energy by our wind to planting trees for wildlife cover; saving the shelter-belts being destroyed by center-pivots and improving habitat for our wildlife. I heartily agree with all of this and believe if you ever paid a visit to northern Rock County you will note many ranchers planting trees and trying to improve habitat as a practice of their own with no thought of compensation.

I also followed with interest the habitat bill passed by the Legislature to improve wildlife habitat, and feel it is a great step forward.

I must say I found it ironic and disturb ing, however, to read in the newspaper the headline "Two Projects Given Game Dad's OK" and to see they are sanctioning the construction of the O'Neill project and the North Loup project. If you had really looked over the entire area of those two projects with a thought of saving habitat, wildlife, trees and grasslands, I cannot see how you could OK such projects.

The O'Neill project will destroy many, many acres of cedar, pine, oak, cottonwood, wild plum and hundreds of kinds of other trees and shrubs, and cover for birds as well as destroy some prime trout streams and drain much-needed water from the area to irrigate and destroy many acres of habitat farther east. Conservation of soil in this very sandy area is of great importance to all of the residents of northern Cherry, Brown, Rock and Holt counties who have spent years trying to hold the soil and improve these areas. Building canals and having heavy equipment move into this area will be exceptionally hard on this type of soil and its habitat.

I would certainly like to know how the Game and Parks Commission can live with themselves knowing they are backing projects which are spending taxpayers' money. To me this is biting the hand that feeds you. Who is going to take care of you when the taxpayers run out of money? I hope all of you at the Game and Parks Commission will give this more thought and reconsider before it is positively too late.

Gettie Sandall Red Cedar Ranch Bassett, Nebr.

OBSERVATIONS on the shooting sports

HOW TO MAKE A SPORTSMAN OF YOUR SON

Plain old woodchucks played a big part in my son Steve's becoming a sportsman. He was 9 when I took him on his first 'chuck hunt. Previously he'd learned to shoot various air guns at targets, then a .22 rifle and quite recently, a .222. Steve wanted to become a hunter in the worst way.

After he'd shot his first wood chuck and had admired and exam ined it thoroughly, I toted the animal to a nearby brook and skinned it, then dressed the carcass. Steve wanted the hide, but I had other plans for the meat.

"We're going to have woodchuck stew," I told him. "If you shoot a creature, you ought to eat it if you possibly can."

This was the beginning of a campaign to instill in Steve a regard for wildlife.

The next logical step was to teach him not to take too much, and wood chuck stews helped—no one would want to make a career of eating these. And there was an aspect he hadn't thought of: "If we take every 'chuck in this field, there'll be none next year, or the year after."

It was the same with trout one day. We'd got into a terrific spot on a secluded stream and for once filled out our limits.

"May I catch just one more?"

"Sure, if you turn it loose."

Presently he caught the best fish of the day, and I knew that, if I let him keep it, my plans for him were done. "Put him back for next time," I said. Act the renegade, and so will your son.

Manners were something I worked on hard. I explained that, if someone was fishing a pool or hunting a cover when you got there, you shouldn't go charging in and spoil it for all. A perfect example occurred on a public stream we like in lower New York —someone was fishing our favorite meadow pool (just big enough for one person) when we arrived.

We stood watching, well back from the bank so as not to spook nearby fish. Soon Steve nudged me. He'd seen a trout rise behind a bush at the lower end of the pool. "Couldn't I try for that one?" Steve asked in a low voice.

It was tempting. But where does a little encroachment stop. I per suaded Steve to bypass the pool and try later. "Twenty minutes after that guy quits, they'll all be hitting again," I heard myself saying. This happens in remote areas, but I wasn't so sure about hard-fished Titicus Outlet.

An hour later we were back, empty-handed. But we had the pool to ourselves now. While I enjoyed a fresh pipe on the bank, Steve caught the trout by the bush and another, so I was a prophet with honor that day.

Steve is 24 now and an accomplished rifleman, considerate of game animals (he won't fire unless he can make a sure shot) and people as well. I've noticed that, when we take one of his friends fishing, Steve makes an effort to put our guest in the best spots.

We don't eat woodchuck stew at our house any more, though we still hunt the critters occasionally. Steve proposed another way to show re gard for our quarry—we'd keep the tails and use their long hairs on fish ing lures, dressing up the treble hooks of certain spinners.

I've kept for the last the tough est part of becoming a sportsman: losing gracefully. And believe me, this is a difficult achievement to put across to kids when grownups are so much more experienced and composed than they. You can set a good example yourself, and preach a little, but is it catching?

Anyhow, what gave me hope that Steve was learning to lose occurred on the last day of our vacation on Florida's west coast. Steve had wanted to shoot a crow on the beach with his .22 rifle, but I'd not let him because of the danger to others from ricochets.

This morning we were there early, and the beach empty. Steve was going on 10 and, since he'd become obsessed with swearing, we were trying to break him of the habit by fining him 104 a swearword. I drove the car slowly. Then Steve yelled for me to stop—there was a crow on a dead fish about 100 yards away.

He got out, slipping his arm into the sling as he scuttled ahead bent over, then sat on the sand and stead ied the rifle. At this precise moment, a sports car hurtled from behind us and flashed down the beach. The crow flew off.

Steve came back. When he reached my door, I could see he was fighting back tears, and fighting mad besides. "The damned bastard!" he said, "Here's twenty cents!"

Provided as a public service by The National Shooting Sports Foundation

THE GREAT CHICKEN VALLEY

It was like olden times, when skies were dark with bodies of these exciting birds

I HAD THREE doves to go and probably not enough shells to get them, if the last three were to take the same shell-per-bird average as the first seven did.

Sunlight was also in short supply, as only about a quarter of sol's orange globe remained visible above the first sandhill to the west of us. Most of our wind mill had already fallen into the shadows, which, like clockwork, precedes every clear nightfall on the prairie. Yet, in the distance, the tall prairie grass seemed to illuminate the shadowed valley with the final reflection of a day soon to be history forever.

There is always a final flourish of activity in the waning hours, whether it be wildlife preparing to wait out their destiny in the night, or the sudden appear ance of mule deer preparing to take up life anew in the shelter of darkness.

One final shot at a fast winging dove that had not yet decided to roost seemed to destroy an indescribable solitude, leaving me almost embarrassed for pull ing the trigger. Guilt feelings vanished immediately, however, as what resulted from that explosive interruption of twilight's tranquility, led to some of my finest hours afield.

Not more than 100 yards to the south, 10 to 15 grouse suddenly reliinquished their tall-grass domain, and with intermittent wing beats, soared to a more distant roost. A quick scan of the valley below revealed similar acvtivity by several more bunches of grouse roughly disturbed by my futile last attempt at a dove.

Clifford McMichael, known to just about everybody as Tad, was making his way along the thick shelterbelt which he had been hunting. We had planned to meet at the well to pick and dress our doves. He, too, had seen a few grouse, but the excitement was not as apparent as mine. Maybe (Continued on page 45)

GRETNA TO SCHRAMM A HATCHERY CHANGES ROLES

IN THE MID 1800's the nation's fur industry was in full swing. In those days, it was common practice for trappers loaded with furs from the Rocky Mountain region to ride the high spring waters, "the June rise," of the Platte River east to the Missouri River and then to St. Louis to trade for supplies. John Jacob Astor was one such trapper. He started out one year and had the misfortune of running out of water as the Platte dropped, leaving him stranded near a large Pawnee Indian village. Astor was running low on supplies and was forced to trade his valuable furs to the Indians for horses and other necessities to continue his journey. The site of the Pawnee village and Astor's costiy experience was just west of present-day South Bend, Nebraska.

Across the Platte River from South Bend is another site whose visitors, since 1882, learn something each time they stop.

Schramm State Recreation Area (S.R.A.) is a 331-acre park devoted to the enhancement of the outdoor-education experience of the people of Nebraska.

10The Schramm area was formerly the Gretna State Fish Hatchery, and signs on nearby highways still bear that title. Located on County Road 31 in Sarpy County, the park is situated in the bluffs along the Platte River Valley and is deeply entrenched in the history of Nebraska and of the Game and Parks Commission.

In 1879 the Santee Hatchery, as it was then called, was in operation, owned by two private citizens named Romine and Decker. That year the Nebraska Board of Fish Commissioners (forerunner of the Game and Parks Commission) contracted with the owners to hatch and raise trout and California salmon.

According to reports, the fish were then stocked by the Commission in rivers and streams throughout the state to serve as a food source.

In 1882, the Commissioners purchased the then 54 acre hatchery, grounds and buildings for $1,200 and it be came the first state-owned recreational facility in Nebraska.

Trout and salmon were the primary species raised in the early years, and the high volume of 58-degree water from the natural spring on the area made hatchery conditions excellent for these fish. The salmon were later replaced by catfish, bluegill and crappie, as studies indicated that the salmon were not "taking" to Nebraska waters.

Fish raised at the hatchery were transported, between

1890 and 1905, in the "Antelope", a railroad car especially

constructed to hold ice on which fish tanks were placed

to maintain a cool water temperature during the trip

west. The ice used in the Antelope was stored in a cave

on the area, which still exists. In 1900 the Antelope was

turned over from the Board of Fish Commissioners to the

newly established Nebraska Game and Fish Commission.

The car, badly in need or repair, was taken to the Union

Pacific shops in Omaha during the winter of 1900 and reconditioned at a cost of $61.97. During the early years of

the hatchery, the "fish car" was always on the move.

Over an 18-month period in 1901 and 1902, the car traveled the tracks a total of 9,279 miles stocking streams and

lakes in the most remote portions of the state. It should

be noted that the fish car and employees were pulled

throughout Nebraska as a courtesy by the railroad companies;

FEBRUARY 1977

13

In 1914 the original hatchery building was replaced by the present building, which was in operation until 1974. The "new" building was built on the same foundation as the old, and some people speculate that the first floor of the original building also remained the same. The rock walkways and other structures made of Dakota sand stone and native limestone were completed by the Work Projects Administration (W.P.A.) in the 1930's.

As the Came and Parks Commission acquired more acres of land and water throughout the state, the Gretna Hatchery worked to supply trout and catfish for anglers. Between 1960 and 1970 there was very little production at the hatchery and it served primarily as a holding site for trout, raised at the Commission's Rock Creek Hatchery and stocked in the trout lake at Two Rivers S.R.A.

The demand for fish continued to increase, but by 1974 the high cost of maintenance and repair of cracked and aging waterlines and other hatchery facilities made it unfeasible to continue operation.

In 1967, E. F. Schramm, a geology professor at the University of Nebraska, willed 277 adjoining acres to the Game and Parks Commission in memory of his parents. As stipulated in the will, the area would be used strictly as a public park and for field study.

Since the grant was made, the Commission and Roger Stine, park superintendent, have been actively devel oping the area into a multi-use, outdoor education com plex. A nature trail, VA miles long, winds through the park and is scheduled for completion this year. Visitors to the trail will enjoy the scenic views of the river, various wild ife species which inhabit the area, a meditation shelter, and plant identification signs along the trail marking ev erything from oak to poison ivy.

A new educational building is on the drawing board and will include an aquarium containing native fish, an audio-visual room for programs and slide presentations, and a natural-history room explaining the past of the area and the Platte Valley.

The future looks bright for the recreation area, as it enters another phase of its colorful history. Five sheltered picnic areas with modern restroom facilities and play ground equipment offer a beautiful setting for a family outing. One large group shelter is also available for three or four-family picnics.

The old hatchery ponds provide easy-access, armchair fishing. The ponds are stocked four times each summer with 3,000 pounds of carp each time. A tree planting op eration scheduled this spring will eventually provide shade trees for mid-day fishermen.

The area also includes land along the Platte River and provides good access for both fishermen and canoeists.

No overnight camping is allowed on the area at present, but Adirondack shelters are scheduled for con struction to allow back-pack camping in the near future. Due to the lack of vandalism and proper use by consid erate people, the front gates of the area are left open for early morning fishermen and late evening sunset watch ers.

Schramm State Recreation Area has something for ev eryone. Nature lovers, geologists, historians, sportsmen and countless others who visit the park will find scenery and quiet enjoyment, and will doubtless benefit from the outdoor experience.

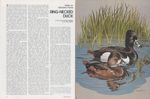

The Sound of Whistling Wings

THE SANDHILLS are no doubt the ultimate place to hunt for a person who cares to see the sights that go with hunting. I suppose it's the best place to get what you're after, too.

The Sandhills have adventure to go along with the hunt, as finding the way to a lake you want to hunt is half the fun. In an area where there are a lot of lakes, it is tough remembering them all, and we don't often hunt a lake twice in a row. Of course there are exceptions, like the one that my best hunting partner Mike Liberski and I have. It's a place we can always depend on for some good shooting; sort of a "sure place" to hunt.

One thing about the Sandhills are the terrific fringe benefits that come with it. Some of the places I've been were unbelievable, mainly because of the birds. In the morning, the ducks are moving from one lake to another, like on the first day of duck season this year (1975). The ducks were really buzzing into the lake we were going to hunt that day, coming in from other lakes. They weren't missing the tops of the hills by more than a few feet—we couldn't believe how low they were flying.

It was still dark when we got there, and we could really hear wings whistling. They were literally right on top of us before we could see them silhouetted against the graying sky. By dawn the lake was full of ducks, dabbling in the moss beds and weaving in and out of the rushes. The teal seemed so restless compared to the other ducks on the lake. The mallards would come in and sit down and not move, and an old hen sat and squawked all morning until she had called in more ducks than she knew what to do with.

Just before sunrise, Mike and I went out to toss out some decoys, and the mallards were strung along the rushes. As we paddled along in the canoe, flocks of about a half dozen would jump up. And, at 7 o'clock in the morning, six mallards can make more noise than you can imagine. The hens would quack so loud and the drakes had their wings a whistling. It's sure a waker upper.

Setting out decoys is a highlight-arguing over the way they should go out and stuff like that is a good time. I guess Mike and I do more ar guing than anything, but when we go into the sandhills we know we'll get birds every time. When Mike isn't there we usually don't do this, but when he is, we make it a habit to carry our guns with us, because if you don't, there are always those smart aleck teal that buzz what decoys you have out and almost take your hat off. That's when you'd give anything to have your gun to take a pass shot at them. But, I guess that's part of it. That early in the morning and as fast as they were going, you know darn well you wouldn't have done any good on them anyway. At least we could scare them so they wouldn't do that any more.

It's the best feeling in the world to clip one of those little devils and watch him fold up like a snowball and hit the water. Then comes my best friend, Duke, my dog, in for the retrieve.

After getting in the canoe and getting all set up is a good part of the hunt, too. It isn't very long and the early fliers are cruising around looking for trouble. You've got to be on the ball then, too. They come out of nowhere and are right on top of you and then are gone. The first morning we set up like everybody should, and all looked different directions and kept a sharp eye out. We no more than got our guns loaded and a mallard hen sailed in and she was really squawking. We let her slide because we don't usually shoot hens, or "suzies" as we call them.

One thing led to another and we were get ting gadwalls, wigeons and teal in all the time. Since it was the first day, we weren't much for sharp-shooting. As much as I hate to say it, it usually takes me five or six shots to even scratch the first duck. The first day I didn't get one until after nine shots.

About 8:30 or 9 a.m. they quit buzzing around and were all hiding in the rushes on the other end of the lake. This is the part where Elyria kids come in. You might say we have a patent for sneaking on them. Paul Rysavy and I were the two Elyria kids there the first morning so we took off in the canoe.

Hunting like this is mostly what I do. It doesn't take too long and you'll see a bunch or jump a flock out of the rushes. You've got to be on your toes when you're jump shooting, if you don't know the ducks are there. Where we nor mally find the ducks is near a little point of rushes when there is a little bay on the other side. They always seem to like to sit in bays like that, out of the wind and out of sight.

The point system has to be about the best system for ducks we've had. Each duck is about at the right value, and it is the best way in the world to keep hunters from bagging too many of the less plentiful ducks. And, yet, they can get a lot of shooting on the ducks that are plentiful. It's not hard to tell that the guys who complain about the point system are those who can't identify ducks. They'll get out to the blind in the morning and a flock of redheads will fly over and they don't know redheads from teal and they'll blast one. Then they'll re trieve it and find its a redhead and complain because they are done hunting for the day. I think if everybody learned to identify ducks, ev eryone would appreciate the point system and would enjoy duck hunt ing more.

In the evening the ducks fly around again. We usually just sit in the rushes and pass shoot. As far as I know this is the best way. Sundown is a big part of hunting the Sandhills, too. The sun drops over the rushes and the top of the lake turns orange. All the ducks are flying around looking for a place to roost. It is surely a beautiful sight. I would suggest to everybody who likes the outdoors to spend a day on a sandhill lake. You won't regret it.

FOLLOWING THE HOUNDS

WHILE WE WAITED for that first frost of winter, the leaves just stayed in the trees and kept them cloaked in a mantle that made it easier for Mr. Coon to hide. When snow and cold came, it was with a vengence and with wind. Some record lows were set for early December,-and the wind ripped the protecting garb from the trees. During this time we were chomping at the bit, waiting for that "ideal" night to hunt raccoons. We had some nice days; warm, the ground thawing a little, and no wind to speak of. Old man weather had it in for us though. He'd let us get our plans, coffee and sandwiches made, and our minds set on enjoying the hunt, then he'd start the wind ripping and drop the temperature down with a thump.

Such nights serve a purpose, though. Keeper cages can be made, odd jobs around the house done, and there is time for that rare fellowship that only real devotees of the art of coonery can enjoy—exchanging expe riences over hot coffee; reminiscing of fine dogs, long dead but who still live in the minds of the men who hunted with them in years gone by; telling of really tough coons that had given the dogs all they could handle; field-trial dogs that were great. You learn some hunting secrets at these times too how to break dogs off deer and rabbit, how to develop tree dogs, how to make the dogs come in after a hunt. You file a lot of useful knowledge away on nights you can't go hunting, and you say to yourself, "someday my son will follow the hounds and I'll im part to him the things I've learned from my own and others' experiences." A dog will never steer a boy wrong, and I don't think most of the members of old ringtail's fraternity would be bad company in which to bring up a boy.

Friend Ed Wright called about 5 p.m. to say we'd leave about 6:30. I then called John Buss, who had asked about going with us, and invited my eight-year-old son, John, who had wanted to go every time we'd headed out ever since I could remember. He's a hunter's idea of what a son should be. He put on two pair of socks, thermal underwear, heavy jeans, a sweat shirt, with a hood, boots and a jacket. He ate with all of it on to make sure we didn't start without him. When Ed arrived he had Baby Blue and two black and tans, Flash and Darkie Boy. John Buss followed a few minutes later and we were off, headed for the Talmadge, area.

I have been asked why I never talk about my dogs when I tell about a hunt. It's because I don't own a coon dog. How do you begin a story? I had a redbone female, and Rose was a good looking dog. She would, at one time, fight a lead coon and sometimes follow the pack on a drag. I have my own pet coons at home, but I had it in mind that never the twain shall met. I also have a 14-year-old daughter who used to hunt with us. She understood about the live coons and how they were used for restocking, breeding and lead coons. Until one day last year, she had been a watcher on the hunts. She'd carry equipment and never complain. Then, one night we had shot one coon and were on the last chase of the night. Verna and Cecil Pine got to the coon before we did. He was in a little tree just out of reach of the dogs. Verna shook him out and the dogs killed him. It was a slow death and that coon suffered for quite some time. She felt responsible be cause she shook him out, and she has never been hunting with us since.

But now back to Rose. She lost in terest in the lead coons and wouldn't offer to fight them. She would go to the tree with me and watch the other dogs tree, but she would not tree her self. It was as if she actually had affection for those coon. I kept her and tried to make a hunter out of her, and she was good company on a night hunt. She would stay with me even after all the other dogs had left us to hunt.

I got home from work early one day and found Verna playing with Rose and one of the pet coons in the yard. In a reasonable voice, after I calmed down, I asked her what she was doing. She told me that she never wanted Rose to have anything to do with kill ing a coon and decided to try and get Rose and the coons to make friends. Over the course of time she had succeeded, and Rose loved coons. I gave Rose away the next week. I still have pet coons, but until Verna gets married, I'll have to follow someone else's dogs.

Ed had called Herman Wilkin before we left Lincoln. Herman said he had seen sign the day before, so he and his redbone Queenie, joined us and we headed south to try the first mile along Spring Run.

We turned the dogs out where Spring Run crossed a field of winter wheat. The going was easy and every one was in good spirits. The dogs and the hunters were eager, the coons should be feeding, and the ground was perfect for tracking. Darkie Boy opened ahead of us. Flash joined him and the chase was on. Blue and Queenie hopped into the run to join the chorus. After a very short chase we heard Queenie's high soprano tree bark sounding, complimented by Blue's deep bass. Herman opined that they were treed in a brush pile and that we could scratch that coon off the list. As we got closer, the barks changed to the chop, which a dog uses when he looks old ringtail right in the eye. In a minute we heard one of the pups yelp in pain. At first we thought there might be a fight at the tree. When we got there we saw that Blue had the frontquarters and Flash and Darkie Boy were sharing the hindquarters, all pulling in different directions. The dogs had pulled him out of the brush and were playing tug-of-war back and forth across the run. Herman climbed down the bank and peeled the dogs off the coon. He was one of this year's cubs and weighed maybe 9 or 10 pounds.

We stopped to chat while the dogs got started again. Queenie took off up a branch to the right while the other dogs stuck to the main channel of the run. In just a few minutes Blue sounded that, "I'm getting hot," call of his. Then he started barking tree. He was in the run bottom, and the two pups were circling a big Cottonwood growing; on the bank. We finally picked up fur in the lights. The coon was up about 70 feet with only a little patch of hide visible. Climbing that old tree was out of the question. I squeezed off a shot at what I thought was a coon rump, but it was the left shoulder, and he was dead as he came out of the tree. It was another small coon.

Two strikes and two coons in about a half-hour would please most hunters, but we had a bucket with us and were hoping to get a few live coons before the night was over.

We heard Queenie's high pitched cry and moved in her general direc tion. The moon was up now and we could see Ed's car up on the road. When we got close he said that Queenie had passed near him and she had treed up ahead. By this time all four dogs were excitedly barking tree in four different spots of the biggest pile of brush and timber I had ever seen. Someone had cleared a fairly large tract and piled all the timber on the bank of the run. We knew that this was a dead end so we loaded up the dogs and had a cup of coffee.

The night was still young, so we headed for an old, deserted house about two miles away. Everything that could suggest a haunted house was present. It looked dark and dreary, with windows broken out. The rusty wind mill in the yard turned with a spooky creak. The dogs went right to the house and we were in hopes that they might find something there, but we soon found that someone had beaten us to it and had gotten a coon or two. The dogs headed north and we decided to wait before resuming the chase. After about 20 minutes and no sound from the dogs, we figured a long chase on a cold track. Ed and I drove around the section to where the hunt started, and listened. We heard Blue and he was treeing. He had evidently treed where a coon had tapped and then, recognizing his error, had picked up the scent again and trailed it to a den tree. We couldn't do anything with the tree, an old Cottonwood snag that hung out over a small creek, so we left to return to the car. As we got close to the farmyard we heard Blue pick up a hot one on the other side of roadr. The rest of the dogs joined him, so we followed after. I had the bucket with me and hoped that this, the last chase of the night, would reward us with a live coon in the bucket. The four dogs really let us know they had something. We got to the creek bank and played the lights on a rather large brush pile. All four dogs were pulling at dead limbs and slashing small branches as they tried to get under and at the coon. Herman, John and Ed went across the creek to help the dogs pull away branches. I sat down on the bucket and told them to call when they needed it. Little John sat with me and we enjoyed the show. When the dogs weren't snapping twigs they were barking. The three men pulled branches, yelled at each other, and tried to help the dogs. Blue finally got to where the coon was because he started to howl in pain. Ed got a light on him and saw a big, old coon with Blue's foot in his mouth. At this point, Queenie came in from the side and the coon let go of Blue and turned to her. Blue turned the tables then and got a leg, the pups charged in, and coon, dogs and Ed hit the creek. Ed got overbalanced and fell in, and be fore they could get all the dogs collared, the coon was too badly hurt to save. He weighed in at 31 pounds.

Our hunt was over for the night, but it was interesting and profitable. Our primary purpose, to chase and locate coon, had been fulfilled. We give the dogs a chance to do battle with a coon, and it was the first in a long time. My son, John, made me very proud of him. He had walked all the way with the rest of us. He hadn't complained once and I know that I'll always have a hunting buddy at home to share the talk of the hunts that were and those that are to come.

NEBRASKAland proudly presents the stories of its readers. Here is the opportunity so many have requested —a chance to tell their own out door tales. Hunting trips, the "big fish that got away", unforgettable characters, outdoor im pressions—all have a place here.

If you have a story to tell, jot it down and send it to Editor, NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebr. 68503. Send photographs, black and white or color, too, if any are available.

Refuge for a Jinx

A DeSoto Bend fishing trip cost us all our lures, and I knew my partner was strictly bad luck

IN ONE WAY or another, all sportsmen are a little superstitious. Most have a favorite hunting cap or a spe cial lure or some other "magic" object that, when left behind, is the cause for any and all bad luck.

How many times have you heard: "If I only had that little pink one with the white legs, I'm sure I'd catch fish?" When it's not something you left behind, it's something you carried along just to try out.

An empty stringer can easily be accounted for. "This new pole just hasn't got the action of my old one." Or, "I don't care what that guy at the sport ing goods store said, this new lure doesn't work worth a darn!"

Guns and ammunition always fall subject to verbal onslaughts, especially when they're new, borrowed or cheap. What do you hear when a shot is missed or a trigger pulled on a spent shell or an empty chamber?

"This gun shoots a lot different than my old double-barrel." Or, "I'm not used to this automatic. It doesn't feel right and besides that it loads funny."

Most sportsmen hear the true classic at least once a season when a rooster is cleanly missed and from amidst the gunners someone hollers, "cheap shells!"

When all your usual gear is present and accounted for, the next most obvious scapegoat is the weather. If the ducks aren't flying it's the weather's fault. The clouds are too high! The clouds are too low! It's too cloudy; or of course, it can always be too clear.

But what can you say when the birds are there but you missed your shot, or when you have fish on repeat edly but can't seem to land one?

The simplest and most logical explanation is that your parnter is a jinx.

Mick Bresley is a conservation offi cer with the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission and lives in Bellevue. In addition to being a very effective officer in the field, Mick gives me a great deal of help throughout the year. In the Nebraska Hunter Safety Program and other educational efforts in the Omaha area, he has proved in valuable. His willing-to-help attitude, combined with a vast knowledge of the outdoors, contributes significantly to every program we do. When our free time coincides, Mick and I enjoy heading for the country and trying a hand at the sports we talk about and work with every day.

Now, from what I understand, Mick's a fairly proficient sportsman. Proficient in that he bags birds or catches fish nearly every trip out.

I also consider myself an effective food gatherer. My wife and family enjoy meals of fish and fowl throughout the year.

Separately we do very well in the field, but any combination of the two is a boon for wildlife. Of course the only explanation for our combined misfortune afield and afloat is that Mick is the world's biggest jinx.

Early last September we decided to head north to the De Soto National Wildlife Refuge east of Blair, and match our fishing skill against De Soto Lake's wily crappie population. The lake itself is only part of the 7,800-acre refuge located between Blair, Nebraska and Missouri Valley, Iowa. The refuge was established in 1959 and in cludes land on both sides of the river. The Missouri River of yesterday was much like the Platte River of today. Each spring the water would flood the lowlands in the valley and cut new channels for the river to follow. The river continued to have a free rein until 1960, when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers completed construction of a new channel, thus harnessing the river and straightening its path. This new channel cut off a seven-mile bend of the river forming what is known today as De Soto Bend Lake. The refuge is probably best known for the vast numbers of waterfowl that use the lake as a rest area during their annual migration from the prairies of Canada to the Texas coast. During peak peri ods, over 400,000 geese and nearly 1 million ducks make use of this old oxbow of the Missouri.

With water recreation very limited in eastern Nebraska, De Soto Lake provides a large body of water, open to the public, and easily accessible from the metropolitan Omaha area. The lake has a very good largemouth bass population and equally good crappie.

Dave Heffernan, assistant refuge manager, and Reta Bekaert, the refuge secretary, had promised to point us in the right direction. Their encouraging words, combined with the local fish ing report, which had 12-inch crappie sinking your boat, heightened our hopes of a two-family fish fry.

We stopped at the local bait shop for minnows and asked for a couple dozen. A conservative estimate of what the minnow-man guessed was two dozen would be in the neighbor hood of six dozen. This had to be a good omen, we decided, as we pushed off from the dock and headed up the lake.

The cool air and warm water combined in a beautiful way as a light, steanly mist drifted over the bow of the boat. Beams of sunlight began to cut through the dense cottonwood forests and shone through the steam like tiny lasers.

The lake surface was calm except for our wake as we neared a series of wooden pilings. Mick killed the motor and let us drift into a promising look ing pocket. Once anchored, we each rigged one pole for crappie with two No. 6 hooks, a split shot and a small bobber. The other poles we decided would be used for spin casting.

I watched as the first two minnows made a gradual wiggling descent and the weight of the split shot pulled the line taught on the bobber. As Mick's bait splashed noisily to the surface I wondered how much fish could hear. Soon we were casting spinner baits and swapping fishing stories as we watched the bobbers out of the corners of our eyes.

Usually when stili fishing, you can expect a short waiting period after your line hits the water before any action begins. If nothing else it gives the fisherman that moment of anticipation. But 40 minutes of anticipation when you're crappie fishing is about all I can stand.

Lifting anchor, we decided to drift a little as a light breeze had come up out of the south. The breeze brought with it an osprey which sailed slowly across the lake searching for fish.

I had started cranking in the lure when the bobber on my other line began sinking beneath the surface. I quickly exchanged poles and pulled back to set the hook. Apparently I had done a great job of setting it, as there was no way it would then break lose from a submerged piling. The snag was deeper than an arm could reach, so only the bobber made it back to the boat.

I had a sneaking suspicion that my partner, the jinx, had a role in this misfortune, but I decided to give him a break and not accuse him yet.

While rebaiting new hooks, I no ticed that the boat was moving slowly but steadily into the wind. I had to laugh when I looked up to see Mick battling a 300-pound piling.

"What's the size limit on creosote poles?" I asked. "I've heard they're pretty good eating but that they're awfully hard to fillet."

Mick just frowned at my verbal jabs.

"You think this is funny," he said; "try to get your lure off the bottom."

in all the commotion of snapping lines and piling fighting, I had completely forgotten about my second poie. I grabbed it and lifted as I reeled only to be stopped dead by another demon of the deep. The crisp snap of monofilament line echoed across the lake as both lines broke, yielding to the stationary strengths of the bottom.

We decided to fish the pilings a ittle longer. (Continued on page 42)

Gifts of Land

More than 4,500 acres have been donated to the Game and Parks

ACQUIRING land for public use can be an involved and expensive proposition, and can be fraught with difficulty and opposition. Yet, nothing can have such long-time value than recreation areas devoted to the public's use.

Each year land prices increase and money available for their purchase is harder to come by. And, Nebraska's status among the states, particularly those to the west, is very low when comparing the amount of land in the public domain.

In fact, the Game and Parks Commission has for years stressed the impor tance of good hunter-landowner relations because only about 3 percent of the state's land is in public ownership. And, much of that is federal land, rather than state.

And yet, there are a few occasions when some benefactor, a person who appreciates the need for public land and who can do something about it, makes a gift of land to the Commission. They believed that land for public use is perhaps the highest value that can be obtained from it.

Over the years, those precious acres will become even more valuable, and will accomplish more with each passing year. With utilization of such areas in creasing steadily and the cost of land ever rising, gifts of land take on ever greater importance.

Donations of land to the Game and Parks Commission started back in 1923 when the decendents of J. Sterling Morton, and officials of Nebraska City, do nated 65 acres of land including the beautiful home of the Mortons, to the Commission. This became the state's first historical park, Arbor Lodge, which has been visited by millions of people since that time. It has enabled the Parks Division of the Commission to preserve some historical treasures within the mansion, and to maintain the arbore tum started by J. Sterling Morton, founder of Arbor Day. Total value of this property would be extremely difficult to evaluate today, as much of the collection housed in the lodge is irreplaceable and thus invaluable.

Commission for public use Since the donation of Arbor Lodge, the Commission has gained title to 14 other parcels of land ranging in size from just over 15 acres to over 1,500 acres. Average size of the land donations is over 300 acres, and the total is around 4,500 acres. Even using conservative estimates, this places the present value of the land alone at one million dollars, and possibly three times that.

Often, in addition to outright gifts, lands are also sold to the Commission at reduced cost, sometimes consid erably below market value. In the case of the most recent acquisition, the Gifford Tract just south of Omaha, 576 acres were donated by Dr. Harold Gifford Jr., and another 721 acres adjoining it were sold below market value by the Gifford Foundation.

Between 1923 and 1976, the following donations were made to the Commission, with many of the areas now used as public parks. Land at Fort Kearny, for example, was given by the Fort Kearny Memorial Association in June of 1929, comprising just over 38 acres, and which is now a popular reconstructed pioneer military outpost.

In 1930, two sizeable parcels of land were given over to the Commission the first in March when Henry E. Pressey donated and willed the 1,524 acres which is now the Pressey State Special Use Area. The other, which became Niobrara State Park, was over 408 acres donated by the Board of Trustees of the City of Niobrara in April.

It was 1947 when the next piece of land was donated—this being the land and water known as Smith Lake. Made up of just over 640 acres, the property was a partial gift from James Smith. Another sizeable contribution was from Ford Wanamaker, who gave 160 acres near Imperial in 1951. This area is used as a waterfowl sanctuary and up land game bird refuge.

The Pawnee County Sportsman's Club made a cash donation which was used toward acquisition of 560 acres which became Burchard Lake State Special Use Area. The donation was made in August of 1957.

Then followed several years in a row in which important parcels of land came into public ownership. In August 1960, Dr. Glen Auble of Ord deeded just over 15 acres of land containing the remains of Fort Hartsuff to the Game and Parks Commission. This fort, established to protect settlers in the Loup Valley, still had existing buildings as they were constructed of a concrete like grout rather than logs or dirt. Much restoration work has been done at the fort since.

The next year, in July of 1961, the Village of Brownville donated nearly 23 acres of land for the Brownville State Recreation Area. And, in 1962, 80 acres near Curtis became the Hansen Memo rial area through a donation from Anna Marie Jamison. And, in 1963 two gifts were received. The first was in April when Nebraska City made a partial do nation for acquisition of 37 acres for use as the Riverview State Recreation Area. Then, in July the Fort Atkinson Founda tion donated half the 147 plus acres containing the original Fort Atkinson, and which is now undergoing restoration and research to locate the original structures.

In October of 1965, the American Game Association donated over 160 acres near Johnstown which became known as the American Game Marsh, and which offers hunting for grouse, waterfowl and other species to a lesser extent. Of that total, 120 acres is water.

A beautiful 277-acre piece of land adjoining Gretna Fish Hatchery (see story on page 10 of this issue) was willed to the Commission by E. F. Schramm, a former geology professor at the University of Nebraska, in 1967. The donation was in memory of his parents, George and Mary Schramm.

And, the most recent gift of land is known as Gifford Point, with an official name yet to be decided. Donated by Harold Gifford Jr., M.D., the land adjoins Fontenelle Forest south of Omaha, and includes 576 timbered acres. In addition, 721 acres of adjoining land was sold to the Commission below market value by the Gifford Foundation, Inc. This gift was finalized in December 1976, and estimated value of the donated land exceeds $600,000.

In addition to the above, other gifts are pending or land acquisition is not yet complete. Included is a $1,500 donation by Mrs. Donald Whitney as a memorial for her husband who was in terested in wildlife. With federal match ing funds, this money can acquire $6,000 in land, which will be in the Beatrice area.

Some of the lands dedicated to public use were a family farm or a special tract. Some gifts came with rigid stipulations, which may be difficult legally and morally to carry out. Others, however, come with no strings attached. Actually, some gifts have been returned to do nors simply because the Commission did not have sufficient funds to develop the lands as requested. Occasionally, the developments are not compatible with the land type or location.

Basically, however, gifts of land have been a tremendous boon to the present and future recreation picture in Nebraska, and each donor deserves the highest accolades for the generosity to the public.

The Water's Edge

Beachcombers are rewarded finding the unexpected. Hurly-burly world is left behind

AFTER ICE-OUT, but before winter is forced north, lakes cleanse themselves. Aquatic life too fragile for the extremes of Great Plains weather is washed ashore. Relics of man's presence are revealed by drought-stricken, retreating lakes or exposed in winter-crushed vegetation. Shorelines of natural waters, expecially of isolated Sandhill lakes, tell tales of life and death, of man's comings and goings. Combing the beaches can give a fleeting glimpse of the life that inhabits the edge where sky, earth and water meet, where man is only a passerby; his mark on the beach swept away by the timeless wash at water's edge.

Sandy beaches are not Nebraska's hallmark. And, all too often, those sweeps of shoreline that we have are marred by litter, the leavings of livestock or the pug marks of the ubiquitous off-the-road vehicle. Big Alkali Lake south of Valentine has none of these detractions and meets all the requisites of the purist beachcomber. Big Alkali is a natural lake fringed by a wide sandy beach; it is isolated, and you can walk free of the roar of power boats, and its beaches are a tabloid of lakeside life and of man's transient affairs there. Washed ashore are the flotsam of waterflowers and anglers from decades past, weathered skulls of behemoth pike and feathers of molting bluebills.

As with any avocation, beachcombing should be embraced with a certain obsession to protocol. By tradition, early morning is the time for walking shorelines. The caress of a gentle breeze is a desirable amenity, one that is seldom wanting in Nebraska. Isolation from the rest of humanity is an essential requirement, one that sandhill lakes and early morning hours largely insure. Bare feet, an abundance of sunshine, a silent companion, gulls overhead and a shoreline enriched by a recent storm enhance the day.

Two species of beachcombers are indigenous to lakeside-the "keeper" and the "turner". Keepers haul most everything home. They're recognizable by their driftwood centerpieces, collection of turn-of-the-century medicine bottles and custom of carrying burlap sacks wherever they go. For keepers, almost anything weathered at the water's edge has a practical use and is carted off.

Turners are adept at prying objects from waterlogged sand with their toes. Occasionally a turner will pick something up and examine it, but they always return it to its former resting place. One species of beachcomber is not preferred over the other, and, occasionally the two species hybridize.

Fishing permits will cost anglers more cash, but the investment should give them something in return. The Habitat Plan aims for river access, new lakes, better management

FISHING...THE HABITAT PLAN

IN CASE YOU haven't noticed, prices continue to rise on just about everything, including, alas, our 1977 fish ing permits. But, while most prices are hiked with no attempt to give the consumer something additional in return, that will not be the case for the fisherman.

Our permit fees will go up to help fund fish and wildlife improvements under the Game and Parks Commission's Habitat Plan. Resident fishing fees have gone from $4 to $7.50, the nonresident annual fee jumped from $15 to $30, the 5-^day nonresident fee went from $5 to $15, and the new nonresident permit for the Missouri River only, is $15.

The difference between this in crease and most of the other price hikes we face daily is that this will buy the consumer, in this case the fish erman, some benefits that would otherwise not be his. However, the benefits will come some years down the road, so anglers can look upon their new fees as an investment in their future.

The additional money generated by fishing permits will be combined with hunting and trapping fee increases to help fund the Habitat Plan. A stated objective of this plan is "To perpetuate and enhance the fish and wildlife resources of Nebraska for recreational ... use by Nebraskans and their visitors." In plain language, the Habitat Plan aims to improve fishing opportunity, among other things.

One of the most important things for the fisherman is a place to wet a line. All the gear in the world is not worth a hoot if there is no place to go. And, an abundance of rivers and lakes is of little value to the average angler if he has no access to them.

Additional access to existing fishing waters, primarily our rivers, will be one of the most visible fishing benefits of the Habitat Plan. Purchase of river frontage and woodlands for public hunting and fishing is one of the prior ities of the Plan. Nebraska's rivers are an important fishery resource, but in the past the fishing in these waters has been of limited value to the general public in many cases because private land owners control most of the access.

Purchase of newly created waters will be another feature of the Habitat Plan that should delight anglers. State and federal programs are backing construction of reservoirs for purposes other than recreation, primarily erosion and flood control. These are small to medium sized waters, ranging from an acre or two up to several dozen acres. They provide excellent potential for fishing opportunity in some instances provided they can be placed in public ownership by the Game and Parks Commission for public recreation.

A few reservoirs of this type have already been purchased by the Game and Parks Commission. However, the Habitat Plan will make more such transactions possible. Once new waters are obtained for Nebraska fishermen they need to be managed for them. This will include costs of removal of undesirable fish populations, stocking game fish, and perhaps the introduction of under water rock or brush piles for fish habitat.

A fourth benefit to fishermen will be the overall improvement of the land and water environment. Consider, for example, the fencing of selected trout streams in western and northern Nebraska. By excluding cattle from most of the narrow strip of land immediately adjacent to the stream, we get both game habitat on the land and a trout stream in which the fish can reproduce. Of course this would require an agreement with willing landowners. The cover on the land keeps the banks from eroding and covering trout eggs with smothering layers of silt and sand. Cattle can still drink at strategically located gaps in the fence.

The Habitat Plan is a blend of activities related to both fish and game, and it will be funded by both hunting and fishing permit money. A few projects and practices might be devoted mainly to fishing. More will be heavily weighted toward hunter benefits, however, since hunters will supply the lion's share of the funds.

But it is very likely that there will also be many land purchases and management programs designed for both fish and game benefits. For example, lands which fishermen look upon as great access points for river fishing might also provide a stand for deer hunters, a place for a scattergun ner to roust a covey of quail, or a spot for a waterfowler to throw up a quick blind and put out a few decoys.

The new fishing reservoir will do double duty, too, with duck hunters at the water's edge and pheasant, quail, rabbit, squirrel, deer or turkey hunters on surrounding land.

The money to pay for these new fishing benefits will come from that extra $3.50 added to your 1977 permit. It's a small price to pay, if you put it into perspective. That $3.50 will add up to no more than the cost of a couple of new lures, or a new load of quality line on a pair of reels. But, combined with similar investments of the thousands of other Nebraska fish ermen, look at what it will buy.

Not knowing what to do next, I just kept staring at the dead bird

The Time at the Cabin

THE GATE was tall—too tall for me to reach—so my brother slid the latch while I watched, my chin on the edge of the front seat.

It was still dark and I could barely make him out once he left the headlights' beam. I stared at the circling mist and soon he reappeared, signaling us to drive through. Once through, we stopped and waited for Terry to reclose the gate.

That was important, my father said; to keep the gate closed. Grandpa and the farmer have a contract. It says we've got to close the gate and we can't hurt the land. That's okay with me, I thought, I'm ready to agree with anything, long as I get to the cabin.

Terry ran up and jumped in the front seat. Dad put the car in gear and driving slowly, we followed the muddy tracks. I didn't know how far the cabin was, so I stood on the edge of the back seat and gazed out the front window, full of questions but too scared to ask. I would have asked them, but dad was mad because he hadn't wanted to take me along. Mom had argued for me, so here I was on the way to the cabin. The only problem was that I would be with my father, not mother.

When we got to the cabin, dad pulled the car right up next to grandpa's truck and parked. We all got out and I just stood there staring at the building. It was all white with home-made stairs that didn't quite reach up to the front door.

On the drive down dad had said there was no electric ity and the bathroom would be outside. This was because grandpa wouldn't allow progress or women, two things he seemed to be always fighting. I couldn't argue with that reasoning. I was tired of city life, and the girls, well, I didn't really like them myself.

My father carried me on his shoulders and I had to duck when we walked through the doorway into the only room.

32 NEBRASKAlandEverything got quiet when we came in. I looked at all my cousins and they didn't say anything; just stared.

The silence was broken by my grandfather's laughter as he walked over and lifted me from father's shoulders. He looked deeply into my eyes and then carried me back to the table, setting me on his lap. From there even my father looked little. I watched him pour a cup of coffee and sit down across the table, silent. I looked around for my brother but couldn't seem to find him. My search was interrupted when my grandfather started chuckling. He looked straight at my father and safd aloud, "Junior, why'd you bring the boy ... he aint hardly big enough yet." Dad didn't answer. He just kept drinking his coffee, and stared at grandpa.

"Okay, by God; he is big enough. Here Danny," he said, pushing his cup toward me and filling it with coffee. "It's going to be a long day and you'll need to keep warm."

I sniffed and the smell hurt my nose. Grandpa stirred the coffee cool and I drank it quickly, not wanting to look at my father.

I guess the big moment was over, because everybody started talking about fishing, freeing my eyes to wander. The light wasn't bright; a kind of hazy yellow filled the air and mixed with the smell of coffee. The light, I found out later, was made by kerosene lanterns, the coffee by my grandfather. I saw the old cots and noticed the rough concrete floor. In the center of the room stood a wood burning stove, and sitting on top was a gray enamel cof fee pot. I stared at everything, but my eyes never got tired because it was all so new. I guess seeing is a whole lot better than hearing.

When it started to get light all my cousins began to pull on their sweatshirts and lace their boots. The room was filled with a thumping sound as they set their feet solidly.

On the drive down my father had said that morning was chore time and that I would be expected to help. The young kids usually gathered firewood and carried water from the well. The older, more experienced boys had the important job of seining bait for the evening's fishing. I expected to carry water and firewood, but was surprised by my grandfather, who took me aside and whispered: "Now Danny, I'm going to send you out with Butch to seine bait. . . it's a hard job, so watch carefully. Don't tear the nets and do what your cousin tells you. Those old crawdads got pincers and probably won't like being disturbed this early, so watch out." With that he pinched me on the rear and pushed me out the door where I saw Butch. He was dragging some nets and seemed to be sorting them.

Butch wasn't my favorite cousin. He was the oldest and always teased me, but this time I wasn't going to let him scare me.

When I got close enough to touch, he threw the nets at me and walked ahead, a pellet rifle on his shoulder. We hadn't gone very far before I realized that it would be impossible to keep up with him. The nets and my pants cuffs kept getting snagged on the tree branches, so I slowed down when he was out of sight. I could still hear him firing the rifle, but it was hard to tell where the sound was coming from, so I finally just sat down to wait.

I don't know how long I waited, but I must have been daydreaming because Butch sure surprised me when he tapped my shoulder.

"What in the hell are you doing, just sitting here? I got work to do. Here, give me the nets, you hold the rifle. I don't need a little kid to help me. Just wait here and try not to shoot yourself or get lost. I'll be back later to pick you up."

He was pretty mad, so I didn't argue; just waited until he came to pick me up.

When we got back to the cabin my cousins had finished their chores and were getting ready to go horse back riding. I wanted to go riding but dad said I had to sleep all afternoon if I was going out fishing that night.

It got pretty quiet after everyone had left, so I just walked around the cabin and looked at grandpa's gun collection. I must have dozed off because the next thing I remember is someone shaking me. It was my father.

"Danny . . . Danny, wake up, grandpa is outside and wants to talk with you about something important." When I walked out the door I saw my grandfather and another man talking.

"Danny, this here is Ben Goodwin. He's the man that owns all this land. He'd like to talk with you."

"Hi Danny, I believe this is the first time we've met." He held out his hand and I grabbed it, but not for very long because it was so bumpy and hard. "Yea, well, you might not understand all this Danny, but I'll try to explain it. This is my land and I love it very much. Every living part of it is a part of me, so I get pretty upset if I think that someone is abusing it." I didn't know what he was talk ing about; I couldn't remember doing anything wrong.

"Do you know anything about this?" He held up a dead bird that was all black, except it had a red head. I just shook my head no. "Well, Danny, it was shot with a pellet rifle, and Butch told me that he didn't do it. You were the only other person that handled that rifle today, so one of you must be lying." I didn't say anything, just kept staring at the bird, wondering what to do next.

No one said anything more and I just stood there watching my grandfather. He turned and started to walk up the road with Mr. Goodwin, my father walking be hind.

Later grandpa came in and told me that I couldn't go fishing that night and that I couldn't sleep in the cabin. He said they would make a bed for me in one of the cars.

I didn't get to go fishing that night and the next day being Sunday, we had to go home. When we were pack ing up the car grandpa just stood around watching and never said a word to me. But before we left he walked over and picked me up. He carried me around behind the cabin and held up a stringer with the night's catch on it. Holding one end of it himself, he handed me the other and my father took a picture of just us two.

I never got to go back to the cabin because the next year my grandfather died and the land reverted back to the farmer, but I do have a photograph. It shows two people, one obviously old and the other young. My youth was revealed by the fish; they were bigger.

STILL THE GOOD OLD DAYS

AGRICULTURE has been the basic industry of all but the most nomadic hunting societies, and enabled people to settle down and work toward civilization. Yet, individual pursuits, problems and commitments prompt most people to overlook the fundamental need for the agricultural specialist, the farmer.

Nowhere in the world has agriculture reached the high state of productivity and technology as in America, and it makes a comparison with the "good old days" more stark because of the many changes. Youngsters, perhaps, grow tired of comparisons with the way things used to be, but that is because they cannot appreciate how vast those changes have been.

In the early days, before the tractor, plowing and other field work was done slowly and tediously by horse and simple machine, or possibly totally by hand. Now, it is difficult to imagine having to go outside to get water for drinking and bathing, and having to heat it on a rudimentary stove. There was not even a cold water faucet, let alone one that magically produced hot water. And, instead of lolling around watching a fantastically colorful television show, how about reading a book or periodical under the meager light of a kerosene lamp?

My grandfather, Frank Hemberger, is one of those farmers who survived only by hard work. He and my grandmother began farming back in the early 1920's when hard work was a fact of life and the only way to get by. Born in 1900, he has lived through the horse and buggy era and into the space age. He was there when the horseless carriage first made its appearance, but he has also seen man exploring outer space.

In those good old days, farmers didn't have fancy machines. Grain had to be moved from wagons into grainaries with a scoop shovel, instead of augers or elevators, and often was put into the wagons after being harvested by hand. Farmers had to suffer through the drouth and depression, had to struggle through hard winters without modern furnaces, through killing blizzards which even today strand people for days.

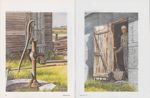

Yet, life hasn't changed all that much since those early days on the Hemberger farm. Many machines have replaced old farming methods, but plenty of hard work still remains. And, reminders of the past are everywhere, from the old cistern that still pumps water to the old grainary which still houses fruit of the growing season. The chickens still roam the yard and the old barn is still in use. Even horse-drawn farm machines remain in evidence—partly for sentimental reasons. The old cave which was used for storage is still there to protect the family from storms. The old house, built be fore the turn of the century, still stands virtually unchanged except for a few "necessary" improve ments.

Life on the farm, however, is in many ways rewarding. My parents were both raised on a farm, and I have listened to their many stories and feel that kids who are brought up in the city are missing out on a lot of things. The peacefulness and clean air of the country are something that many city people have never experienced. There is just an atmosphere of freedom which cannot be felt many other places.

We in Nebraska are very fortunate to still have clean air and beautiful countrysides, and most of us realize that farmers are still a very important part of our lives.

34 NEBRASKAland FEBRUARY 1977 35

Adventures with Whiskers the prairie vole

Who Eats Who!

How do you do. I am Professor Thaddeus B. Vole. You may address me as Professor Vole. I am chairman of the zoology department here at the Midwest Institute for Cricetid Equality, MICE for short. My nephew Melvin, you know him as Whiskers I believe, asked me to meet you here and talk about the food chains of nature. I never could understand that boy, using a primitive nickname when my sister bestowed such a refined Christian appellation on the little fellow. He always was some thing of a rebel. Ah well, makes no difference, we must not dawdle; time is short.

As I said, our lesson for today is food chains. It is important to understand that all life begins with the sun. The sun supplies energy used to grow plants. Directly or indirectly, all animals feed on this energy stored in the leaves, stems, fruit and roots of plants.

Animals that eat plants are called herbivores. Herbivores come in all sizes. A 2,000-pound buffalo eats only plants. If you looked at a drop of pond water under a microscope, you would see tiny herbivores eating even smaller plants. Prairie voles are herbivores, too, so you can see that it is an honorable category.

But being an herbivore is not just "a walk through the daisies" as my nephew might say. Hardly anyone bothers a large herbivore like a buffalo or a deer, but it is quite another story for most of us. Herbivores are easy meals for animals called carnivores, which eat meat. Hawks, owls, garter snakes, foxes and even dragonflies are carnivores. Some carnivores even eat other carnivores. A red-tailed hawk may eat a weasel that just ate a field mouse. This all sounds very cruel, but it is a healthy thing. If carnivores didn't stop herb ivores like us voles from overpopulating, we would soon eat all our food or die off from disease. Eat and be eaten—this is nature's way. Class dismissed.

In a pond, microscopic plants make food from the sun. Small animals eat these tiny plants and are in turn eaten by larger animals like the dragonfly nymph. The dragonfly may end up being a meal for a leapoard frog, and a snake may eat the drog. If the snake isn't real careful he may be a late-day snack for a hungry bittern that just ahppened to be walking by. This is just one of thousands of food chains that can be found in nature.

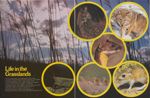

Life in the Grasslands

REFUGE FOR A JINX

(Continued from page 21)so we rerigged our lines and cast out. We should have learned from our mistakes and quit while we were only a little be hind. When we finally lifted anchor an hour and a half later, the pilings must have looked like submerged Christmas trees, as the only pieces of our equipment that weren't adorning them were our tackle boxes. The bright sunlight revealed the reds and golds of shiny spinner baits glistening in the depths. Silver hooks sparkled along a moss-green cable far beneath the surface, much like wet tinsel.

Our total catch up until then was one 4 inch crappie which made it back to the water, 12 pilings, and 2 rusty cables. With a record like that we couldn't just quit. We still had plenty of minnows and a few hooks left, so we headed around the lake for the beaver lodges; another crappie hot spot.

Outside of the activity and excitement caused by a doe and her fawn spooking from the water's edge as we approached, this spot proved worse than the first. We tried every lure we had left, which wasn't many, and drifted minnows all over the place without a single strike.

It was nearing 2 p.m. when we called it a day and headed for the boat dock. By then there was no doubt in my mind that "the jinx" had cast his evil spell over the entire outing.

As we turned south on Interstate 29 to ward home, I explained my jinx theory to Mick and just how he fit into it.

At the end of my lengthy explanation, Mick turned and stared at me with one of those "I don't believe it," looks that the of ficers are famous for.

"Today's fishing," he said," is a scientific sport and there's no room for superstition. Next time you can stay home. Besides, you bring me bad luck!"

42 Announcing

The 8th Annual

Comhusker Invitational Trap Shoot

YOU, TOO, CAN JOIN THE SPORT SHOOTING FRATERNITY AT THE NATION'S

LARGEST COMBINED HIGH SCHOOL AND COLLEGE TRAP SHOOT

Three days of non-registered competition are on tap,

APRIL 22, 23 and 24. Held at Doniphan, home of

Nebraska's registered State Tournament.

High School competition on April 22 and 23 will

feature 100, 16-yard targets the first day, 100 handicap

targets on the second day.

College gunners will compete in a 200-target program on April 24.

Wore than 50 trophies will be awarded during the 3-day event

including the 3rd Annual Comhusker Cup presented by the Game

and Parks Commission to the top Nebraska high school shooter.

COMPETE AS A TEAM OR AS AN INDIVIDUAL

FOR YOUR HIGH SCHOOL OR COLLEGE

For information and programs, direct correspondence to:

SHOOT DIRECTOR

Dave Wells, Comhusker Invitational Trap Shoot

1210 Nebraska Ave.

Norfolk, Nebraska 68701

Phone 402-371-1648

Announcing

The 8th Annual

Comhusker Invitational Trap Shoot

YOU, TOO, CAN JOIN THE SPORT SHOOTING FRATERNITY AT THE NATION'S

LARGEST COMBINED HIGH SCHOOL AND COLLEGE TRAP SHOOT

Three days of non-registered competition are on tap,

APRIL 22, 23 and 24. Held at Doniphan, home of

Nebraska's registered State Tournament.

High School competition on April 22 and 23 will

feature 100, 16-yard targets the first day, 100 handicap

targets on the second day.

College gunners will compete in a 200-target program on April 24.

Wore than 50 trophies will be awarded during the 3-day event

including the 3rd Annual Comhusker Cup presented by the Game

and Parks Commission to the top Nebraska high school shooter.

COMPETE AS A TEAM OR AS AN INDIVIDUAL

FOR YOUR HIGH SCHOOL OR COLLEGE

For information and programs, direct correspondence to:

SHOOT DIRECTOR

Dave Wells, Comhusker Invitational Trap Shoot

1210 Nebraska Ave.

Norfolk, Nebraska 68701

Phone 402-371-1648

THE GREAT CHICKEN VALLEY

(Continued from page 9)this was due to the fact that he had 30 more years of experience under his belt than I had, and it took a heck of a lot more than a few grouse fluttering around to extract as much jubilance as I was showing. Then again, maybe the fact that he knew that this particular section was loaded with grouse lessened the impact of their presence that evening.

Tad was born in the hills north of North Platte in 1916. He lived there, grazed cattle, milked a few cows, and even helped row-crop this land which was never intended for such use. He remembers the drought of the 1930% and the sand drifting like snow as it was swept away from the roots of the cane and corn plants that intruded on an area mistakenly broken by the plow.