NEBRASKAland

December 1976 60 Cents

NEBRASKAland

VOL. 54 / NO. 12 / DECEMBER 1976 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Sixty cents per copy. Subscription rates $5 for one year, $9 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKMand, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. commission Chairman: Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 Vice Chairman: Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-Central District, (308) 745-1694 2nd Vice Chairman: Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-Central District, (308) 452-3800 H. B. "Tod" Kuntzelman, North Platte Southwest District, (308) 532-2982 Richard W. Nisley, Roca Southeast District, (402) 782-6850 Director: Eugene T. Mahoney Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, Jr. Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: Jon Farrar, Ken Bouc, Bill McClurg Contributing Editors: Bob Grier, Faye Musil, Tim Hergenrader, Roland Hoffman, Bill Janssen, Butch Isom, Ben Schole Art Director: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1976. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska DECEMBER 1976 Contents FEATURES TACKLING A DUCK HUNT 8 A WAITING TIME 10 BIG GAME AND ITS BIG FOLLOWING 18 SMELL OF SUCCESS 20 BIG GAME! 22 'PLAIN" TROPHY 32 A RIDE INTO HISTORY 34 ADVENTURES WITH WHISKERS/Feeding Winter Birds 40 NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA/Green-winged Teal 50 DEPARTMENTS Trading Post 49 COVER: Both white-tailed and mule deer gather in bands during winter, and it is not uncommon to find from 25 to possibly a hundred or more at a time. These mule deer were surprised by the photographer in the open hills of western Nebraska. OPPOSITE: Perhaps the only time that a pine tree is more beautiful than in the summer, is during the winter. Then, they truly become focal points for nature's artistry, collecting snow and frost in a most becoming fashion. Photos by Bob Grier. 3

STUHR MUSEUM of the Prairie Pioneer

U.S. 281-34 Junction Grand Island, Nebraska 68801GUNSMITHING!

T. W. MENCK, GUNSMITH 5703 So. 77, RALSTON, NB Call 592-5810 AnytimeDEER PROCESSING

WE MAKE DEER SUMMER SAUSAGE JOHNSON LOCKERS 466-2777 Lincoln, NebraskaSears

WHERE AMERICA SHOPS

Good hunting ahead withThe Commonwealth now pays even higher interest rates!

6.25% Passbook Savings 6.54% Annual Yield Comp. Daily> 6.75% 1 Yr. Cert. 7.08% Annual Yield Comp. Daily 7.00% 2 Yr. Cert. 7.35% Annual Yield Comp. Daily 7.25% 3 Yr. Cert. 7.62% Annual Yield Comp. Daily 8.00% 4 Yr. Cert. 8.45% Annual Yield Comp. Daily A substantial interest penalty, as required by law, will be imposed for early withdrawal.CHRISTMAS GIFT SPECIAL FROM NEBRASKAland

For those special someones. . . NEBRASKAland and Portrait of the Plains

Name Address City State Zip One-year ($5) With "Portrait" ($7.50*) Two-year ($9) With "Portrait" ($11.50*) New "Portrait" only ($5 plus tax) Renewal Hard-cover "Portrait" ($7.50 plus tax) Sign gift card with: *Plus sales tax on the $2.50 for "Portrait of the Plains" Name Address City State Zip One-year ($5) With "Portrait" ($7.50*) Two-year ($9) With "Portrait" ($11.50*) New "Portrait" only ($5 plus tax) Renewal Hard-cover "Portrait" ($7.50 plus tax) Sign gift card with: *Plus sales tax on the $2.50 for "Portrait of the Plains" Name Address City State Zip One-year ($5) With "Portrait" ($7.50*) Two-year ($9) With "Portrait" ($11.50*) New "Portrait" only ($5 plus tax) Renewal Hard-cover "Portrait" ($7.50 plus tax) Sign gift card with: *Plus sales tax on the $2.50 for "Portrait of the Plains" Name Address City State Zip One-year ($5) With "Portrait" ($7.50*) Two-year ($9) With "Portrait" ($11.50*) New "Portrait" only ($5 plus tax) Renewal Hard-cover "Portrait" ($7.50 plus tax) Sign gift card with: *Plus sales tax on the $2.50 for "Portrait of the Plains"

TACKLING A DUCK HUNT

When a Missouri River blind contains two Big Red football stars, the feathers and stories fly. Both defense and offense score on birds and fun

WATERFOWL HUNTERS love many noises. The sound of the wind as it whistles through the wings of a brace of mallards or the noble honk of a white-cheeked Canada generates excitement in the hearts of most shotgunners. The sharp crack of breaking ice as men open water for themselves and their decoys, and the metallic clank of a locking action combine to create memories not soon forgotten.

As much as I love these noises, it was the sound of a friend's sports car that I most wanted to hear as I sat in front of the Peru Post Office on a foggy morning one November morning in 1975. It was the morning I was to meet Tony Davis and John O'Leary, the University of Nebraska Big Red running back combination, for a duck hunt. We were to be the guests of Ramon Henry, a Peru native better known as "Dutch," and the members of his club for a day of waterfowl hunting near the Missouri River.

Earlier in the season I was invited to hunt with Dutch and we spent the entire day talking about 8 our favorite subjects: waterfowl and football. Dutch, like most Nebraskans, is an avid fan of Big Red football and especially enjoys the skills of Coach Mike Corgan's hard-nosed running backs. When asked if I thought Davis and O'Leary would enjoy hunting with Dutch, there was no doubt in my mind and it took only one phone call to set it up.

Every organized hunting club has a set of rules that all members must follow to insure the safety of the hunters and the continued enjoyment of the sport. These rules are habit-forming, and one such conditioned behavior of Dutch and his members is to meet on the main street of Peru 30 minutes before shooting time. This allows for traveling time to the blinds and any other duties that must be performed before the action starts.

If there's anything a duck hunter can't stand it's a late partner, so at 29 minutes before shooting time I was already apologizing for my friends' tardiness. After being assured that they didn't mind waiting, I felt a (Continued on page 47)

NEBRASKAland

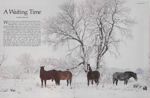

A Waiting Time

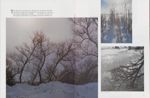

We may have years in Nebraska that are almost without a spring or a fall, but our winters never fail us. Although they sometimes drag in very reluctantly and then abruptly give way to spring, once here, their intensity more than makes up for their occasional tardiness.

The initial excitement we feel in December, as we adjust to the season's rhythm of short, bright days and long, cold nights, soon fades. Then winter becomes only a time of waiting. By February we have grown impatient, tired of the cold monotony. The snow has aged and turned to ice, and everything seems stripped and reduced by the elements. The trees stand like skeletons casting long shadows on the white ground. Only the sky lends color to the land. But Nebraska's winters have a harsh clean beauty. Perhaps you have to be born here and grow up on the Great Plains, to fully see and appreciate it.

The days are very short now. But the sun dominates the horizon just as it did in the summer. It's a mocking sun, flooding the winter landscape with light ... its oblique rays glare on the surface of the snow as it pushes across the southern sky.

Nebraska is so vulnerable in winter. There are no mountain ranges to slow the movement of large air masses as they sweep across the state. When they clash, terrible, marauding blizzards are born. And then, that always nagging wind suddenly becomes violent. Sleet and snow follow. Temperatures plummet.

Severe winter storms are a part of life in Nebraska. The cold wind has always blown unimpeded over the flat, nearly treeless plains. Life here has accepted this, adapted, and grown hardy. The rabbit and coyote can dig through deep snow to find nourishment, while the deer and pheasant are able to glean old corn and milo fields for food. And, if they must, most animals can go for weeks living only on their fall fat reserves. But, none can survive a blizzard without shelter. Without a protective thicket or brushy fencerow, animals can suffocate or freeze as the wind-beaten snow lodges under their fur or feathers, and there turns to lethal ice. Others, weakened by the lack of shelter, fall to disease.

In the dead of winter, Nebraska might appear empty and lifeless. Sometimes only the wind seems vital as it blows scratchy snow into drifts and collides with creaking tree branches. But life is everywhere ... just waiting. It is deep underground in the grass's roots and it is dormant in the tree buds. You must look for it, but it's there. It's peering out from under snow-covered bushes. It's hibernating under logs. It's with the frogs buried safely in the mud, waiting for spring.

BIG GAME AND ITS BIG FOLLOWING

IN THE EARLY 1900s fewer than 100 deer were present in Nebraska. Then, by 1940 the deer had increased to a few thousand, and by 1945 there was a sufficient population to support a limited hunting season. By 1949, annual deer seasons could be held.

According to historical records, antelope numbers were at a very low level at the turn of the century, and only in recent years has our pronghorn population attained high enough density to warrant open seasons. The 1953 season was the first legal hunt for antelope in nearly 50 years, and 150 permits were issued that year.

Present-day estimates in Nebraska are 100,000 deer, which are hunted in all 93 counties; and 9,000 antelope, with hunting allowed mainly in the Sandhills and Panhandle. The Nebraska Game and Parks Commission is responsible for management of the deer and antelope herds, and annually administers the issuance of approximately 38,000 deer and antelope permits. In the past few years, demand for permits has exceeded the number available. Thus, the Commission has devised an allocation system designed to make issuance of permits as fair as possible.

There are 17 deer units in Nebraska in which a hunter can apply for a firearm permit. These units are set up for the purpose of deer management through control of harvest, with units having a varying number of either-sex permits alloted. A high number of either-sex permits in a unit is geared for deer herd reduction or stabilization, and a low number of either-sex permits is intended to increase the herd with some utilization of surplus does.

From 1959 to 1968, permits were issued on a first-come, first-served basis. Demand for permits became high, and opportunity for eastern Nebraska residents to obtain permits was greater than for those farther west because of mail delivery. A drawing system was started in 1969 when 2 of the 17 management units (Elkhorn and Wahoo) were over subscribed. The following three years, drawings were necessary DECEMBER 1976 in the same units plus the Blue, which also had more applications than permits. In 1973 six units filled—the three previous high-demand units plus the Buffalo, Keya Paha and Pine Ridge. Regulations were changed in 1974 so that persons who held a Blue, Wahoo or Elkhorn permit in 1973 were not eligible to apply during the first application period. With this change in regulations, all six units that filled the past year, plus four additional units, were over subscribed.

Regulations changed again in 1975 to obtain a more equitable distribution of permits; the two application period system was initiated. Individuals who held a firearm permit the previous year were not eligible to apply during the first application period. This system gave individuals who did not obtain a permit the past year, first chance for permits. This system is currently being used, and this year three units filled during the first application period and all but two units filled on the second application period with first and second unit choices. (Table 2).

The unit choice on application allows the hunter to name a preference of area where he or she would like to hunt. If there are more applications than permits available, and an individual is not successful in obtaining his first choice in the drawing, then his second choice is considered if that unit is not filled by first choice applicants. Thus, there is no point in using Blue, Elkhorn or Wahoo units as second choices since they all fill with first choices.

If a person wants to hunt only in the Blue, Elkhorn or Wahoo units, it is best to leave the second choice blank, as an unsuccessful applicant will be eligible for the first application period for these units next year. He would not be eligible if he put in a second choice unit and received a permit.

Regulations on obtaining firearm antelope permits are even more restrictive than deer, as individuals who have an antelope permit in either of the past two years were not eligible to apply during the first application period. In the past few years, no permits have been available after the first application period, and if current trends in antelope hunting interest continue, it is doubtful that a second application period will be held in the future. Using 1976 statistics, an individual's chance of receiving a permit is approximately 51%. (Table 3).

Total number of deer and antelope archery permits are unlimited except that an individual may obtain only one of each type per year.

Characteristics of Nebraska big game hunters have been studied by the Commission and results indicate that the average age of firearm hunters is 35, while the average age of archery hunters was 6 years younger—29. Modern big game archery hunting is a relatively new sport which could possibly explain the interest by the younger hunter. (Table 1)

A few years ago, a change in the law allowed 14 and 15-year-olds to hunt big game, and at that time, many older hunters expressed concern that these younger hunters would take many of the permits. Statistics indicate that their fears were unfounded, since only 2% of the permits are held by this age group.

Although number of female big game hunters has been increasing over the past few years, males still comprise 90 + % of the deer and antelope hunters.

Another interesting statistic is that a local hunter, one who resides in a county which is included in the management unit, is 40% more successful than non-locals. This could possibly be attributed to a local hunter's more thorough knowledge of the area and/ or more time spent hunting.

One fact that the Game Commission is well aware of is that whether young or old, male or female, new hunter or seasoned veteran, if a hunter doesn't get a permit, he is unhappy. But, the present system is considered most fair, giving more people a chance to enjoy big game hunting in their home state.

19

Smell of Success

ONE DAY WHEN ART, my father's 17-year-old "hired man", was handy and trapping was on my mind, I asked if he had ever trapped skunks. "Yeah, lots of 'em", Art replied. "How do you do it?", I eagerly continued.

"Ya' just find a den hole and set a trap in it". After a moment Art went on: "Skunks are dumb critters. Now, a mink or a coyote is smart. He can smell that ol' trap and will step over it, or paw dirt over it. But a skunk—he ain't suspicious of the man smell and just goes blundering along. All you gotta do is dig out a little place for the trap and sprinkle some dirt over it. Don't have the trap stick up in his way or he'll try to walk around it".

As a 10-year-old farm boy in southwest Nebraska in the years before World War I, I had become aware that older bovs—and some of their fathers, too—often made a little money during the winter months by trapping skunks, muskrats and other furbearers. Money for me was hard to come by, so the idea of trapping had strong appeal. My parents' ideas on the rearing of children did not include cash allowances, and I was reaching an age when I

We had a couple of rusty old No. 1 steel traps among the farm clutter, and somehow I scrounged enough money to buy two or three more at the local hardware. With these I started my trapping career.

Eventually an unfortunate skunk stepped into one of my traps. Then came the real sticky business—dispatching the animal without getting badly "stunk up".. I learned that a skunk in a trap seldom if ever dispenses its odiferous spray until molested by a person or by a dog, but that after a lethal blow to the head, or a rifle bullet, it invariably will emit some of its smelly fluid. Since I had no rifle at that time, I had to dispatch my skunks with a club. By acting cautiously, I was able to do this without disastrous consequences.

The next step was to skin the animal. Art gave me a few pointers on how to do the job, cautioning me to cut carefully around the "stink bag" near the anal opening. He also showed me how to shape a board for stretching and drying the pelt. I learned that the skinning always imparted a trace of skunk aroma to my hands and clothes—an aroma highly resistant to soap and water. And, it was often a basis for snide remarks by some of my peers at school.

I caught perhaps three or four skunks during that first trapping season. Meanwhile, from talk and from reading the enticing catalogs and price quotations put out by the fur buying concerns in St. Louis and elsewhere, I learned about the variations in the white markings of these distinctive animals. Four classes ordinarily were recognized: broad-stripe, narrow-stripe, short-stripe, and black. Black pelts were the most valuable, broad-stripe the least. Most skunks in our area were classed as narrow-stripe. I have never seen a totally black one. There also were spotted skunks, a much smaller and less valuable species, but equally smelly. These often were erroneously called civet cats.

Finally came the time when the pelts were dry enough to send to market. After removal from the stretch boards, they were packaged, a shipping tag affixed, and the package started on its way from the Railway Express office. Then the impatient, eager wait for the return from the fur dealer in St. Louis. Eventually, an envelope returned in the mail containing an invoice listing the pelts by size, grade, stripe category and price. And a check, convertible into real money at the bank! Who, except a formerly impecunious boy, can appreciate the tremendous thrill of that first check!

Skunks are gentle, non-aggressive creatures, but unlike practically all the other locally native mammals such as rabbits, squirrels, coyotes and such, which are flighty, skunks display little tendency to run from possible enemies. They seem to feel secure, and expect other animals to make way for them. Many young dogs, and perhaps other predators, learn about a skunk's defenses the hard way; usually one encounter is enough, and thereafter their meetings with skunks are "full of sound and fury" but generally devoid of close contact.

I can cite two personal experiences that confirm the skunk's gentle, nonaggressive nature. The first occurred a year or two after I started trapping. A man near our town with some ill-starred notions of engaging in fur farming, was offering five dollars apiece for live skunks delivered to his "farm". That sounded to me like a good deal, so with my next catch I proposed to take the animal live for sale to the fur farmer. My father, upon learning of my plans, had visions of a smelly disaster and decided he had better take over. Obsetving him, I was impressed by the demonstration that "gently does it" when dealing with a skunk.

We carried a burlap bag in which a hole had been cut in the bottom, and a piece of heavy wire about four feet long with one end bent into a hook. We approached the trapped skunk slowly, making no quick movements that might alarm him. He behaved as skunks in traps usually do, facing us and backing into the burrow as far as the trap chain would permit.

I had staked the trap with some sort of rod that extended two feet or so above ground; the ring of the trap chain had simply been slipped over the stake and could easily be lifted off.

My second experience attesting to the skunk's gentle nature occurred during World War II years in a state far removed from Nebraska. I had a large "Victory" garden, including a plot of sweet corn that the local raccoons found much to their liking. In an attempt to discourage the 'coons, I set several steel traps. This bothered the coons not at all, but a day or two later there was a skunk in one of the traps! What to do? I was in a real quandary. If I killed the skunk—by whatever means—he would stink up the vicinity, perhaps (Continued on page 46)

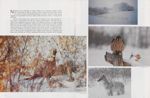

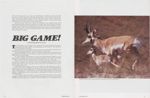

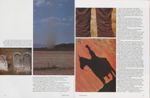

BIG GAME!

BIG GAME IS big business. Last year over 38,500 hunters in Nebraska spent at least $15 each for a permit to hunt deer and antelope with either a rifle or a bow. Why do they hunt? Ask a hundred different people and you'll likely get as many answers. A chance at a trophy, food for the table or maybe just a chance to get out-of-doors, are just a few reasons why hunters go out every fall in search of big game. Those who don't often find it difficult to understand how anybody could shoot such beautiful animals as deer and antelope. Most hunters also share feelings for the game they hunt, but they know that nature provides a surplus. Think of these animals as a harvestable resource, with hunters cropping the surplus animals much as a farmer or rancher does with his livestock, so that the remaining animals have sufficient food and habitat to survive through the winter.THE ANTELOPE is a truly unique critter. Equipped with built-in 8-power vision and a long, streamlined body capable of running speeds up to 60 mph for short distances, he is the master of the plains.

His powerful vision is his greatest asset, and what he sees, he doesn't necessarily fear because he is fleet and nothing in his natural habitat can catch him.

To beat the antelope at his own game, the hunter should be able to stalk within a few hundred yards of the beast. This isn't really very difficult. Archers have to get within 50 yards before they are close enough.

Too many antelope hunters spend too much time driving around, looking for a nice buck and then "stalking" him with a four-wheel-drive vehicle. It's not much of a challenge to chase an animal for miles and then jump out and blast away at it with a rifle.

Hunters who do this are missing the point; and excitement and the challenge. An antelope buck in his domain is no match for a man in an automobile. Against a man on foot, he has the edge, but his curiosity can get the best of him. This is his weakness, and a smart hunter uses it against him.

One thing is certain, though. Unless you are careful, be it 100 yards away or a mile, if the animal can be seen, he probably can see you. However, he may not be alarmed. This is where patience and careful stalking pay off. Taking advantage of a draw, washout, hill or even a small depression, a smart hunter kneels or crawls, using whatever cover the terrain affords. A scrubby bush or tree, a clump of grass or anything can be used by a hunter to approach his quarry.

If the hunter is lucky, the animal is just over the hill and he may get a shot. Often, though, he is still too far away and more sneaking is necessary to get closer. An archer feels fortunate to get one shot a day. Whether he scores depends on his shooting skill and 22 NEBRASKAland

An antelope watching the archery hunter will often jump at the twang of the bow string, causing the arrow to miss. A rifle hunter has no such problem, and unless he gets buck fever, his chances for a clean, one-shot kill are high.

Successful archers have a way of using the animal's innate curiosity to good advantage. They say that a white flag waving in the breeze will arouse the suspicions and curiosity of most any antelope within a mile. If the hunter remains out of sight, the animal will often stare at the flag for a while. Then, curiosity overcomes good sense and it will often come on a dead run until it gets close enough to identify the foreign object. Archers claim to have had animals come within 20 yards of them by using this trick.

DECEMBER 1976 25

Some hunters use a technique that works when the rut is on. The stronger buck gathers a harem of does and chases off any smaller bucks that try to infringe on his harem. A wise hunter will position himself in an area close to where the group has recently passed, and can often get a shot at any smaller bucks trailing the group.

Other hunters spend the early morning hours on a high vantage point glassing the prairies. If competition isn't too great from other hunters, they wait until the animal beds down and then they check the surrounding terrain, trying to find a way to stalk the animal.

Whatever the motivation for hunting them, or the methods used, the walking hunter will appreciate the qualities that make the antelope a fine trophy, and will derive a far greater sense of satisfaction from the hunt than those who hunt from a vehicle.

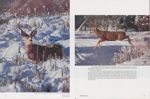

26 NEBRASKAlandTHERE IS SOMETHING special about opening day of deer season. Early to bed, you toss and turn, trying to get the rest you'll need to make it through tomorrow, finally dropping off to a deep sleep. You're ready to bust the biggest buck of all time, when the alarm brings you back to reality, several hours before dawn.

Whether it's for mule deer in the Pine Ridge or whitetails in a cornfield, the excitement is the same. You've waited all year for a chance at the big one you didn't get last year.

Deer are smart. Whitetails have the reputation of being more so than mulies but it probably is more of a reflection of the area they live in rather than the animal's intelligence. Whitetails are secretive and seldom seen in the daytime, and a hunter who just goes out expecting to find one, easily may be in for a big surprise.

DECEMBER 1976 27

A knowledge of the animal's habits and hangouts is helpful, as the differences between the two species are varied. Also important is the time of the year, whether the rut is on, and local weather conditions.

Mule deer prefer open country, while the whitetail prefers concealment, often in the thickest cover he can find. In general, their needs are basically the same. Simply, they need food and a place to hide out during the day. A smart hunter acts accordingly, hunting near cornfields, alfalfa fields and green wheat, early and late in the day. The balance of the time, he tramps the heavy cover for whitetails or ridges for mulies. He tries to pick his spot prior to opening day, using binoculars to glass the prime areas early in the morning and late in the afternoon.

DECEMBER 1976 29

Deer are endowed with keen hearing, good eyesight, a sense of smell that would put a shorthair to shame and a coat that blends in perfectly with most fall backgrounds. They seem to have the advantage, but they are creatures of habit and if there is one single thing that puts the venison on the table, this is it. By knowing in advance where the deer feed and the route they take, it is rpuch easier to bag one.

Best places to find whitetails are often along creeks, rivers and other timbered areas. Find the travel lanes, then get a suitable perch in a nearby tree or haystack and wait. Deer, like other game species, seldom look up, so try to get above their line of sight. Chances are good that sooner or later a nice whitetail will come along. Try to get to your area well before sunrise and again in the afternoon at least 2 to 3 hours before sundown.

During the day, you might try still-hunting. The good hunter doesn't just blunder through the woods. Anything moving fast means potential danger for the whitetail and he will usually slip away unseen. Instead, try taking a few quiet steps at a time, stop for a minute or so and look around. As long as the deer don't see or smell you, they probably won't be alarmed.

In many areas where corn is standing, deer, and especially whitetails, will often spend the entire day in the cornfields, moving back to water at dusk or even afterwards. These deer can be especially tough to find, and the best way perhaps is to walk the edges, checking down every corn row with binoculars. They blend in almost perfectly and are almost impossible to see unless silhouetted.

Mule deer present a new set of problems. You can often easily find them in the early morning and evening when they feed in corn, wheat and hayfields. Approaching within gun range may be difficult, however, because they prefer open country. If you can see them easily, they can also see you. Perhaps the best way to hunt these areas is to find a haystack or some other perch and then wait for them.

In the daytime, walk the canyons, keeping the wind in your face if possible. Mulies prefer to lie near the upper end of the canyon with the wind at their back and in a position where they can see ahead.

If there is any "easy" time to get a big buck, it is probably during the rut or breeding season. Usually the hunting season coincides with a portion of the rutting season in Nebraska and if a buck ever loses any caution, it would have to be during this time. Watch the doe that passes your stand. If she continually checks her back trail, watch out, the buck may be right behind.

Too often, mule deer hunters, like antelope hunters, spend a lot of time driving around, doing most of their hunting from the comfort of their vehicle. This is a mistake; they are denying themselves the opportunity and enjoyment of matching wits with the animals on their own terms.

Hunted from a vehicle, almost anyone can score on Nebraska's big game species, but given a sporting chance, these animals can't help but gain the respect of the hunter. Anything worth having seldom comes easy. This is what hunting is all about.

A true sportsman measures the success of a trip by the total experience, the knowledge gained and the satisfaction of having met the animal on it's home grounds. To a sportsman, animals bagged are of secondary importance. He knows that he is helping wildlife through his dollars, which help fund wildlife programs, and his hunting, which takes surplus animals from the population. Wildlife is a renewable resource. Ω

DECEMBER 1976 31

PLAIN TROPHY

Dreaming of gigantic deer with monstrous racks need not be of faraway places—try near home

AVID DEER HUNTERS, regardless of i how much they profess to be in the field primarily to supply the freezer with venison for the coming winter, still cannot deny that they often envision a monster buck stepping out of cover and surveying his domain with satisfied eyes.

He may be a gray-sided mule deer surrounded by ponderosa pine or a reddish-brown whitetail backed by-wild grape vines along a river, but certainly the dream-vision has attached gigantic antlers and regal demeaner.

While the big buck is known to be super secretive, equipped with honed senses and reflexes, backed by a brain capable of suspecting almost anything, all that is easy to overlook by the hunter's enthusiasm—after aii, it's his dream and he can do whatever he wants.

In reality, however, most Nebraska deer hunters would probably start naming off several states or Canadian provinces if he were given the chance to partake of a trophy deer hunt without the rather cumbersome financial considerations being taken into account. Big game hunting elsewhere than in the good old home state has in recent years taken on the proportions of a safari in Africa.

32 NEBRASKAland After Butch Isom, a Game and Parks Commission representative in Omaha, talked with Darrell and pondered upon some of the facets of the hunt, he formulated the following poem (with a noticeable Christmas flavor) in commemoration. The Dream Twas the night before season And my mind was a blur, To sleep was a challenge But did finally occur Visions of grandeur All blended with luck Formed a misty illusion Of a big monstrous buck On through the evening The sight would appear Of crosshairs in focus On a buck that was near From fantasy to reality The transition did jump Surrounded by nature I was perched on a stump Sunrise and fragrances Of beauty untold And the joys of a deer hunt Began to unfold. But sneaking and tracking Were left to the bold As the weather turned nasty Wet damp, and cold Four days of frustration Sunrise til sunset Tired sore muscles My clothes were all wet. But the hum of an alarm clock All too soon did say Up and at em sportsman This is season's last day. In the late of the morning What did appear Up high on a ridge Twas the rump of a deer Rifle to shoulder, And my dreams all came back Through the scope I did see A monstrous big rack Shaking and trembling, Buck fever's no fun. Lo and behold' He started to run A squeeze of the trigger And in disbelief I sped to the buck And sighed with relief A dream of a lifetime Had finally come true Those dreams that happen To only a few.Most states have been forced or coerced into raising non resident hunting permits beyond the reach of all but the most affluent or most avid-those either capable or willing to pay the price. Most big game hunters when shopping around for a hunt, are like students looking for a college to attend. Most must consider cost rather than the prestige.

What, then, would be the choice of a typical Nebraska deer hunter determined to seek a true trophy animal? Probably up for consideration would be the rugged western states, maybe Canada, perhaps even Alaska would be best. There might be visions of pack horses and a snow-capped tent in a snow-capped mountain setting. Maybe even a snowshoe-clan hunter with frosted breath can be seen amid northern pines, stalking a deer trail through trees as a rustic cabin is nestled somewhere in the distance.

Reality, however, is a persistent task-master, DECEMBER 1976 and has a way of interrupting even the most glorious dreams. Yet, plans needn't necessarily be ripped up for a lesser goal. In fact, Nebraska deer hunters can well envision just about anything they want to without fear of disillusionment.

For, it turns out, Nebraska has more than one claim to fame when it comes to big game hunting. Not only is the hunter success figure at the top of the statistics columns, but a recent trophy deer survey turns out with Nebraska also at the top of that list. Of the 100 largest racks scored in North America, 13 came from the hills and dales of Nebraska, putting the Cornhusker state into the top-ranking spot among all states (and Canadian provinces) across the continent. This makes dreaming about monster bucks and making those dreams come true, much easier.

Taking a trophy deer can occasionally be simple, but more often it is a combination of knowledge of the animal and its environment, know-how of hunting techniques, willingness to work long and hard during the hunt, and appreciation or awareness of the deer's strengths, weaknesses and habits.

Among Nebraska hunters who have accomplished these many factors is Darrell Doescher of Wayne. Not only has he cashed in on trophy deer, but he has brought home venison every hunt for the past 12 years.

Darrell is an appliance salesman in Wayne and has built up as good a reputation as a refrigeration technician as he has a hunter. Now 35 years of age, Darrell has an understanding wife and two aspiring hunters in sons David, 14, and Doug, 10.

Some hunters would be happy to have even one substantial rack to hang on a wall somewhere around the house, but for Darrell there is little question about having antlers to fill the bill.

With Nebraska's deer herds in good shape and with management efforts aimed at providing even more trophy animals in the future, perhaps the dreams of many more hunters will become reality in the future. Good hunting, and good dreams. Ω

33

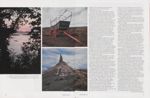

A Ride into History

Seven people and eight horses set out on a 2,200-mile Bicentennial journey, retracing the route taken by thousands of original Oregon Trail travelers

SMALL GROUPS OF PEOPLE were closely huddled on the old courthouse square in Independence, Missouri so that their conversation would not be totally lost in the repeated loud crashes of thunder. Shoulders were humped and a few heads were cocked slightly in order to glance up at the charcoal gray colored clouds each time the thunder was exphasized by a threatening streak of lightning. Eight slender Arabian horses, unimpressive in size, appeared uninterested in the commotion created by the people and weather. The first splatters of rain signaled the crowds to head for the protective awning that hung over the sidewalks on the four sides of historic Independence Square.

The storm increased in intensity. A cold wind whipped wave-like patterns of rain across the brick courthouse yard while people pressed closer together under the shelter. A wet and weathered American flag and Missouri state flag, making a feeble attempt to respond to the forces of the wind, were joined by a new Bicentennial flag. The frail looking middle-aged woman who approached the microphone grasped the metal stand determined to have her words heard above the steady pounding of rain.

34 NEBRASKAland

She began, "We are here to wish Godspeed and protection to pioneers who are leaving Independence for Oregon today. June 16,1975, will be remembered by the people of Independence, Missouri, as the day when we were able, for a few precious minutes, to return to the days when our settlement was the head of the overland route to the legendary Pacific Northwest—"

An assortment of dignitaries took their turns addressing the crowd. Dressed in wet buckskins, we cradled rifles in our arms, wearing sixguns and holding wet leather pouches of maps.

Trail boss Allan Maybee, from Lincoln, Nebraska, knew well what rigors such an expedition would require. In laying the groundwork, his job required insight, planning and patience. In Maybee's saddlebags were kept the maps of the course of the original pioneers.

36 NEBRASKAlandOnce a total commitment was made by Maybee in December, 1974 to ride the entire Oregon Trail, a recruitment began for riders. The first was Chuck Maybee, Allan's 13-year-old son, who would represent the young people who made the original odyssey across America on the Oregon Trail.

Twenty-four-year-old school teacher Cher Hummel was captivated by the challenge of the ride because of her awareness and love of the outdoors. Helping with the initial groundwork, she assisted in the preparation a year prior to the journey. Cher shared the days on the trail by acting as journalist, writing a weekly chronicle for several newspapers.

As an expert horsetrainer, rider and breeder, Alyce Carter from Lakeside joined the contemporary pioneers in the spring of 1975. With the horses' welfare always foremost in her mind, Alyce carried all of their concerns for 2,200 miles, teaching us all. On occasion throughout the summer, Alyce interpreted our trail story through her sometimes humorous, sometimes serious, poetry.

Jean Jeary, a high school senior from Hyannis, rode the historic trail on her gelding, "Flame." Her experiences on her father's cattle and horse ranch were valuable to the ride. With a can of "Red Man" and a harmonica in her shirt pocket, the miles would pass slowly but steadily. An attempt as playing a melody on her untuned harmonica always gave rise to arguments among the riders, trying to guess what she was attempting to play.

The artist, Remington, could not have created a more picturesque 21-year-old cowboy than Jim Quinn of Lodgepole. As a ranch hand in the endless reaches of the Nebraska sandhills, Jim often spoke of having to put sand in his pockets in order to keep the brisk winds from carrying him off to Kansas. His practical knowledge of western horsemanship and special skills as a farrier added more dimension to the expedition. With the jingle of his spurs and cowboy drawl, Jim helped tell the story of America.

Outrider and wagon boss Ron Carter, also from Lakeside, joined the band of pioneer as a result of his persuasive wife Alyce. Always looking ahead for evening camp sites, keeping an inventory of supplies, conducting trail business and as a public relations man, Ron's experiences were unique among the group of seven.

Bo, Jim's Australian blue shepard, assumed the responsibilities of the safety and protection of the eight Arabian horses and riders. His miles were filled with warding off attacks from farm dogs, scouting out the area, making friends with people and keeping the group together.

A lull in the downpour and the words of the little woman speaking at the microphone ". . . and so, the people of Independence wish you all the best of luck . . ." signaled us to turn our attention to the immediate task of riding the untried ranch horses 25 miles through metropolitan Kansas City.

37

The ceremony ended with applause, and the well-wishers and curious followed us across the courtyard to the suddenly impatient horses. Jerry Page, Jackson County Public Works Director, had volunteered to ride his horse "Sally" for the next two days with us in order to help locate the Oregon Trail, which bore little resemblance to the trail 125 years ago, through a maze of winding streets, busy intersections and interstate highways. The potential confrontation between horse and city machines kept us in a state of tension. On the second day, the trail unbelieveably cut through the eighth and ninth hoies of a golf course. A group of paunchy, bermuda-clad, middle aged women watched with disbelieving, sunglass-covered eyes as buckskinned pioneers appeared suddenly from the trees, crossed the golf course and disappeared as suddenly into the timber on the far side of the fairway.

Our small contingent forded the first river near the historic Red Bridge crossing. The first night's camp was set up with the enthusiasm of the beginning of the trip. Advancing black clouds, stiffening winds and heavy air signaled the beginning of round two of the storm that had displayed it's indifference to the historic program earlier that morning. Tents were hurriedly pitched, a supper of rice and soup was coaxed over the campfire, and the horses were bedded down for the night. The storm broke suddenly with all the fury it could muster, and the pioneers scrambled for the protection of tents.

Unusual on the following nights of the 2,200-mile journey, voices could be heard in the tents; voices that reflected the excitement of the first day. We fell asleep to the rhythmic rain.

Early in the ride, the point was made that there would be no distinction of roles between male and female. That is, everyone took care of his own needs, helped others when necessary and shared all facets of duties required on the trail.

We learned early to take one day at a time. In the beginning that was difficult, as was adjusting to the slow pace of the horses after having just left the bustling work-day world. We had left our watches at home; our timepiece was the sun, We knew after one week of the new routine that the very hardest thing after the ride would be to re-enter a world ruled by the clock.

The day began around 6 a.m. after a night's sleep that never seemed long enough. Before sunrise, horses were groomed, breakfast cooked, camp broken and horses saddled. We were on the trail in time to have the sun rise over our shoulders, and enjoyed the coolness and promises of a new day. By 9 a.m. our skin felt the penetrating heat of the sun and by noon it was necessary to halt DECEMBER 1976 travel. The horses suffered from the heat and humidity of Missouri and Kansas. Finding water for the horses, we unsaddled and passed the heat of the day under a shade tree if we were lucky enough to find one. By 3 p.m. we were back on the trail traveling late into the evening until we found a suitable campsite.

Time seldom seemed to drag; each day held new sights and experiences. When we were weary of riding in the heat and humidity of Missouri and Kansas, a sudden afternoon thunderstorm would offer us a change.

Following the story of the trail kept us alert to the rich heritage of the land we were traversing. Oregon Trail markers at intervals assured our way, but also the many reminders of the tragedies on the trail bridged the gap of time and gave us insight to the story of America's people. Many grave sites still are evident.

The trail led us past the site of Susan Hail's grave, a young wife westward bound with her husband. As a result of bad water, she died. Her newly wed husband, grief stricken, immediately returned to St. Joseph to get a stone marker for his wife's grave. He pushed the stone over 250 miles in a creaky wheelbarrow to where his beloved Susan's wooden grave marker stood in lone defiance of the stark plains. We also found many stones with the person identified as "wife of ______" with no identification of her own, which antagonized the women riding the trail in the 20th Century. It is a true paradox that the Oregon Trail, the lifeline to the promised land, is plagued with so many reminders of tragedy and death. There is an estimated 1 grave for every 50 yards of the 2,200-mile-long trail.

Day by day, our love and respect for nature grew. Learning to live with the heat and cold, mosquitoes and horseflies, snakes and wind; we found our place amongst them. We were caught up in the beauty which enveloped us. In Kansas we traversed rolling green wooded hills and rich farmlands, wheat waiting to be harvested and corn reaching skyward. Crossing into Nebraska, the changes of the land were evident as the hilis became less rolling, the land more arid. Guiding us was the Platte River with its colonies of cottonwood trees. We rode down nameless country lanes which followed the natural road of the Oregon Trail, passing fields of soybeans, beets, corn and close enough to the Platte River that its sweet, pungent aroma stayed with us.

Traveling Nebraska trails, we became acquainted with small-town nostalgia. In southeast Nebraska, the trail led us through such unfamiliar places as Alexandria, Oak, Deweese, Spring Ranch and Angus. All small dots on the map, but large on western hospitality. These communities are all very proud of their Oregon Trail heritage and the people keep its spirit alive. The riders were able to follow the trail almost (Continued on page 44)

39

Adventures with Whiskers the prairie vole

HI! SORRY I missed you last month. Those people with NEBRASKAland Magazine had the nerve to say there wasn't room for me in their November issue. Imagine me, Whiskers, a prairie vole, being replaced by a duck.

Don't get me wrong. I don't have anything against birds, even ugly ducklings. In fact, some of my best friends wear feathers. A couple of years ago I got to know a bunch of birds from Canada and we've been real close ever since. Our meeting was kind of unusual. It was one of those early blizzards that Nebraska gets every now and then.

I guess I had a hunch that something was going to happen that day. I was out later than usual gathering food. I'd found this big gooseberry bush loaded with dried fruit. I had already made two trips, stashing berries along my runway in the grass, and was on my third trip when the wind came up. I scurried out from under the bush, but before I could get into the grass, snow started pelting me in the face. I couldn't make any headway into the storm so I decided to sit it out under the gooseberry bush. I hadn't been there long before big gobs of snow started falling on me. I looked up and there were six Harris' sparrows above me. Boy, were they beat. Now I wasn't real hot on spending the night with a bunch of birds, but I figured I would make the best of it. I called up to them to come down out of the wind. We knew we might freeze if we went to sleep, so we decided to talk and keep each other awake.

I learned a lot about Nebraska's winter birds that night. Take my friends, the Harris' sparrows for example. They nest way up on the Arctic tundra. They're not very big birds. With their feathers on they're about the same size as me. Each fall they fly south. A lot of them go all the way to Texas but some stop in eastern Nebraska and spend the winter. Most of the time you'll find them loafing around in weedy roadsides, in fencerows or on the edge of woodlands eating weed seeds.

My friends, though, are sort of gourmet Harris' sparrows. Most of the year they work hard for their food but in the winter they set up housekeeping in the suburbs of Omaha. They've found some people there that put out millet and have plenty of shrubs in their backyards for roosting. That kind of surprised me. In all my years of traveling over Nebraska, I'm yet to find any humans who will put out food for us little prairie voles.

From what the Harris' sparrows told me, it wasn't always so good for them. A few years back there weren't many bushes around the new houses in Omaha and only a few people fed the birds. Worse yet, nobody worried about drinking water for the birds. That's almost as important as food in the winter. According to the sparrows, spending winter in Nebraska can be like a vacation in the Hilton if you shop around for just the right place.

Almost all of the smaller birds like millet, especially tree sparrows and juncos. Cardinals, chickadees and jays prefer sunflower seeds. Suet is available from supermarkets and locker plants for just a few cents a pound and will attract chickadees, blue jays, cardinals, nuthatches and woodpeckers. The Harris' sparrows told me that it is best to put different types of food in different places so that all birds can feed at the same time. If seed is mixed, big birds, like blue jays, hog the feeders.

I wonder if there are any humans around who would thrill to the sight of a wild and woolly prairie vole munching millet on their window sill? If you're interested, drop me a line and I'll be right over. If you'd rather have birds, though, I won't get mad. Maybe you'll even see my friends the Harris' sparrows. Keep the feeders full. See you next month.

43

RIDE INTO HISTORY

(Continued from page 39)exactly, following sets of ruts worn into the rolling hills. Some of the fondest memories of the summer's experience lie here because of the people we met.

The weather remained hot as we pressed on to our next landmark, Fort Kearny and the legendary Valley of the Platte.

We traveled through torturous heat and arrived at the fort in time to lay over for Independence Day. Our horses experimented with their independence on the 4th by finding a way out of the corral and taking an early morning walk out of the park. At 1 a.m. we were alerted of their wanderings by a fellow camper. We hustled out of our tents and rounded up our horses in sleepy confusion, returning them safely to camp six miles away.

It was also on the 4th that our first accident occurred. While in the makeshift corral cleaning the feet of the horses, Ron was mistaken by one of the horses as an aggressor. In an act of defending his feed pan, the horse kicked Ron on the side of the head, instantly knocking him unconscious. Ron was taken to a local hospital, and while not seriously injured, his travels were stopped for several days as he recuperated from a very sore jaw and several chipped teeth.

The trail from Fort Kearny to Buffalo Bill's Ranch, at North Platte, a distance of 100 miles, was easily followed by moving upstream on the south side of the Platte.

We entered western Nebraska and experienced an exhilerating feeling of freedom. For the first time on the trail, atop the rolling hills, no town or farm buildings could be seen. Our measure of distance was shrouded in an endless sea of prairie grasses.

The grasses turned into camouflage for the rattlesnake, and we began to meet a number of those noisy bearers of ill will. Our horses showed no great concern at their presence, which relieved some of our fears.

Maybee was fascinated by these snakes and carried his curiosity to an extreme not far from Ash Hollow when he attempted to pick one up. His plan was simple enough. It was to quickly but gently step on the snake near its head, then just pick it up. He circled the snake 7 or 8 times explaining to the skeptical onlookers that he was "uncoiling the big fellow." Suddenly he moved forward, fended off an attempted strike by the snake with the sole of his boot, and when the snake was extended, he indeed placed his foot in back of the snake's head.

In furious retaliation for being molested, the snake suddenly contracted and pulled free of the boot and struck again. The fangs hit near the ankle but the heavy leather absorbed the hit. Unfortunately, the snake ricocheted up the pant leg. 44 Maybee then rendered his version of the prairie stomp, jumping up and down on one leg and flailing his other leg perpendicular to the plain, he slapped at the wrything critter with his hat. With somewhat less grace than a ballet dancer, he pirouetted his way into a swirling frenzy. The snake backed out of the dark, shaking quarters and retreated. Maybee declined unanimous requests to demonstrate again how to pick up a rattler.

Then, near Bridgeport, Jim was attacked by a wood tick which promptly bit him on the side. Blood poisoning resulted and we were reduced to six for several days while Jim recuperated in a hospital.

As we rode through the valley toward Scottsbluff, the historic landmarks of Courthouse, Jailhouse, Chimney and Castle rocks lifted off the horizon to meet us. After endless miles of flat, rolling land, their unique forms did appear grandiose, and for the first time, the riders understood their importance to pioneers.

Our spirits ran high as we continued into Gering amid the festivities of the annual Oregon Trail Days. Five miles west of Gering we rode through Mitchell Pass and were welcomed by area dignitaries. An invitation to ride in the grand Oregon Trail Days parade was gratefully accepted.

For a week our group rode northwest with Laramie Peak looming on the horizon. The peak appeared as a hazy mirage, cloud-like in appearance. For more than 40 miles it was a beacon to us. The hot afternoons were usually cooled with a rainstorm which originated over the peak sending cooling breezes with dark clouds canopying the ride from the hot July sun.

Wyoming held us in constant awe. It was an ever-changing panorama as we continued climbing westward, and the land was full of stories of the past.

We stirred many herds of antelope grazing securely in the back country. Both horses and riders drank from many small, winding streams which are oases on the western prairie. Riding through the hills, we wondered at the tepee circles on high plateaus and saw old wagon hubs half buried in the ravines. More graves marked the trail as the land grew rougher and more demanding. Wyoming is full of remnants of the past to re-awaken interest in history, and bursting with wonder of nature to demand respect.

It was on a blistering hot afternoon after passing through Guernsey, Wyoming, that we experienced our third serious and almost tragic accident, which caused us to question the importance of our journey. We were riding on a deserted tract of land requiring four or five hours to cover. Horses and riders were showing signs of fatigue. After a short late-afternoon stop at an abandoned stage station, we remounted and ascended a series of hills. Cher was riding slightly behind the main group when a commotion caused us to spin our horses around.

Cher's gray gelding had bolted out of control as she rode past the sun-bleached skeleton of an old range steer. The 96-pound rider went head first onto the rocky ground. Cher was unconscious, her breathing was shallow and she began bleeding from nose and mouth. We were in a very desolate and desperate situation. Ron and Chuck were dispatched to find help as the remainder of the riders stayed to help their fallen companion. Cher remained unconscious for 30 minutes. Ron was able to locate an old truck at the stage station which he coaxed into starting. The injured girl was carefully loaded into the truck and rushed to the Douglas, Wyoming hospital 50 miles away.

Injuries were not serious; a slight concussion, cracked ribs, torn cartilage and bruises demanded an R and R for Cher, but within days she was back on the trail.

Approaching Idaho, our fifth state, we were urged on as peoples' comments were no longer "you have a long way to go" but "you are almost there." We traveled southwest through Smoot and entered Idaho near Montpelier. Soda Springs, a few miles north, marked 1,400 miles and two-thirds of the way. Cutting over Lund Pass to save 17 miles, we traveled through Hot Lava Springs, a steamy oasis nestled at the base of a huge rolling mountain.

We entered Oregon late in August and continued our steady northwest pace. At Farewell Bend we began to anticipate the conclusion of the ride when the beautiful Blue Mountains came into view. Traveling across eastern Oregon, we looked forward to the promise of the Northwest Territory. Filled with the excitement of approaching the destination of a 2,200-mile journey, the mood of the trail had a subtle change. The seven riders shared an unspoken but intense anxiety.

It was easier to laugh at incidents which had seemed serious, but with the successful end near and time serving as a cushion, the mood changed. We became more forgiving and more tolerant.

The journey was definitely ending in the land of "milk and honey." Riding down the road which led us through many orchards in the Hood River Valley, pear and apple trees bowed their laden branches down, offering their delicious fruits. The horses joined the riders in disposing of fruit which hung within easy reach.

The last several days spent in the shadow of Mount Hood stretched on like one long day as time had little meaning with our destination so close. The last day found us up early, spirits high. On the 80th day-Saturday, September 6-we broke camp for the last time and took up the challenge of the final 15 miles. We concluded the trail ride on the outskirts of Oregon City at the marker which commemorates the completion of the Oregon Trail which brought so many thousands of pioneers westward in the loWs. For us, the marker had a very special meaning. Ω

NEBRASKAland1977 NEBRASKAland Calendar

SMELL OF SUCCESS

(Continued from page 21)render some of the corn unusable, and imperil my standing with the neighbors. Then I remembered my boyhood experience of bagging a live skunk for sale to the fur farmer. So, I decided to try to release this creature from the trap and avoid a stunk-up garden. Actually, the job turned out to be quite simple and uneventful.

I got a large burlap bag which I attached to the end of a garden rake so it would hang there like a curtain. Holding this in front of me, I slowly approached the skunk. True to form, he backed away, facing me, but allowed the burlap curtain to approach without becoming unduly alarmed. When I had the curtain up close, i eased it down over the animal and held it in place with the rake. At this point, I quickly stepped up and released his leg from the trap, then let go of the rake and stepped back. The skunk, soon realizing that he was no longer restrained, emerged from under the bag and ambled off. He dispensed no smell.

However, there are some indignities that a skunk will not put up with, as I found out in one very unpleasant, smelly encounter a year or so after I started trapping. It came about in this way: The idea was bandied about in our community that a skunk had to hunch up his body in order to eject his defensive fluid and therefore, if held up by the tail, would be unable to perform effectively because the essential hunching up would be impossible. Knowledgeable adults did not believe this, I'm sure, but some pretended to, presumably to perpetrate a hoax on gullible lads.

I was somewhat skeptical of the idea, but was too naive to know just what to believe. I decided to find out, and the moment of decision came with my next catch. As usual, the trapped animal had emitted no smell and allowed me to approach without reacting in any aggressive way. There I was, with the unfortunate animal within reach at my feet. After a moment of hestitation, I decided it was now or never, so I reached down, grabbed his tail and lifted him off the ground.

Whew! Did I get a quick demonstration of the fallacy of the notion that skunks can't perform if held up by the tail! Practically instantaneously, perhaps even before I had him clear of the ground, he pulled the trigger on his formidable defense mechanism. My hand and arm were drenched with the yellow, smelly fluid; spatters of it struck me in the face and on the rest of my body. I dropped the skunk and beat a hasty retreat.

No amount of soap and water would remove the smell from my hand and arm. Even after removing my outer clothing, I was terribly smelly. Why my parents didn't banish me to the barn I'll never know. If there is a moral to this story, it is this: Folk tales to the contrary, always treat NEBRASKAland skunks with respect, and they will give no offense to man or other animals.

Skunks and an occasional muskrat served me well during my boyhood years. Their pelts provided that much wanted .22-caliber rifle, ammunition for it and for the shotgun that came later, a good pocket watch, and "spending money" for various little luxuries that otherwise would not have been available to me.

Far fewer boys seem now to engage in skunk trapping than during my boyhood in the pre-1920 years. I suspect there are at least two reasons for this, including the quirks of the fur market, also the affluence and sophistication of many of today's youth. Whereas a great many rural and small-town boys and young men 50 or 60 years ago would accept the unpleasant, smelly business of handling skunks because they needed money, which was hard to come by, today's "rich kids", many with allowances, spurn skunk trapping as a degrading way to "make a buck".

So, beset by few natural enemies and by few boys with traps, skunks multiply largely unmolested and either live out their life spans to die of natural causes, or meet untimely ends on the highways where their formidable natural defenses are of no avail. Ω

TACKLING A DUCK HUNT

(Continued from page 8)little better. Soon, above the noise of the talkative group, the whining of a small engine was audible and I breathed a sigh of relief. Out of the mist a car came speeding down the hill.

"Sorry we're late," was the first thing John said as the two men stepped from the car. His dark hair and large frame looked even rougher with a sparce, scraggly beard. The facial hair was a remnant of a winning-streak superstition and would have been shaved off after the Oklahoma loss the week before if John had gotten around to it.

I recognized John immediately. The other large occupant of the rather small car was a friend also, but not the one I had expected. Jerry Wied, a senior defensive tackle, had come in Tony Davis's place after something had come up and the blond fullback couldn't make it. This substitution was heartily acceptable as the majority of the group liked the defense better anyway. After a series of rapid introductions, we headed for Dutch's pond.

As we rode, I told John and Jerry what I knew about Dutch Henry and his waterfowl-hunting background. You don't have to be with him very long to realize that he knows a great deal about ducks and geese. As a boy he began hunting waterfowl on the bars and backwaters of the Missouri River. With the onset of channelization in the 1960's, however, he was forced to move his hunting efforts to more permanent quarters in a flooded field nearby.

This set-up has been improved upon over the years and at present is a duck hunter's dream. Four sunken blinds surround or intersect a 14-acre slough which has an average depth of about 10 inches. The slough is centered in a 50-acre field less than a mile from the river. The blinds are immaculate, and picture-perfect decoys, which Dutch makes at home, dot the surface and shore of the pond, adding the finishing touches.

By amassing the knowledge he has gained from over 40 years of waterfowl hunting and applying it to future seasons, Dutch has built a good reputation for himself and a successful club for his members. Many who know him jokingly comment that he can tell you the species, age and sex of a duck and also whether it's eaten on the morning when it flies over.

Upon arriving, we unloaded our gear and began crossing the frozen ground to the blinds. A small flock of mallards jumped from the patch of open water and headed southeast into the orange light of the morning. The fog had lifted and the clear sky held promise for a nice day.

The group divided at the corner of the slough with five men going to the island blind in the middle, and John, Jerry, Dutch and I taking a blind on the west shore.

While Dutch began breaking ice and freeing frozen decoys, I took John and Jerry into the blind. Descending the stairs of a pit blind through fingers of broom straw for the first time can be a strange experience. After I entered, I turned and watched Jerry come down the steps, and laughed as his foot came down with a hard thud in expectation of another step. John came next, poking his head through the straw and allowing his eyes to get accustomed to the dark before entering completely. Jerry made some comment about offensive players letting the defense lead the way, but John just smiled.

Once we were situated I began telling them some of the blind rules and tips on this type of duck hunting.

"Everyone must stand and shoot at the same time, so one person will call the shots. When a flock comes in, pick out a drake and try to hit him." I said.

I knew we were in trouble when Jerry asked, "What's a drake?" I had hunted pheasants with him before but didn't realize he had never hunted ducks.

After getting O'Feary to stop laughing, we had a crash course on duck identification, after which Jerry felt reasonably sure he knew what we were after. I felt a little better also. John had hunted ducks before and seemed right at home in the blind, so when Dutch took his seat we were ready. I hoped!

The first flock of about 25 mallards came in almost immediately and circled the slough. As they whistled by overhead you could see every color on the drakes and the brown tones of the hens, much to Jerry's enjoyments.

"That's a drake and that's a hen. There's another drake and there's another hen," the bright-eyed tackle muttered as the flock made another pass.

The birds stayed just out of range for several minutes before flaring to the east and back toward the river. I was glad Jerry had the opportunity to see some birds before any shots were fired.

Suddenly, the boom of a 12-gauge sounded from the middle blind and Dutch peered out.

"Get ready." he said. "Straight ahead and a little to the right."

There was less than a second between the time John and Jerry saw the three drakes and when Dutch said 'Take 'em!", but it was all they needed. In one fluid movement they stood up, seperated the broom straw, and with one shot each neatly folded all three drakes. Wied began cheering and O'Leary flashed one of those press conference smiles as our host retrieved the birds. After congratulating the happy pair we began discussing the history of the birds we were seeing, jerry and John were full of questions and Dutch answered them all, completely and accurately.

Peru is located within the boundaries of both the Central and the Mississippi Flyway and draws ducks and geese from each. The majority of the birds moving through eastern Nebraska begin their lives in the natural sloughs and other prime waterfowl nesting habitat of the prairie provinces of Canada. The status of the waterfowl populations in the United States each year is dependent entirely upon the spring water conditions of those regions.

The smaller ducks such as scaup, ringneck, gad well and tea! leave Canada with the first cool weather and head south. Many of these ducks move through Nebraska before the season opens and others provide good hunting the first few weeks after it starts. These ducks winter primarily on the Gulf Coast in the marshes and backwaters of Texas and Louisiana.

As the first winter storm pushes through Canada, the large flocks of mallards begin their annual journey.

Mallards, unlike most other ducks, can withstand severe weather conditions if food and open water remain available. If either of these factors is limited, however, the ducks will continue south. Changes in the weather have the greatest single affect on bird movement, and a successful hunt can usually be attributed to a northern neighbor having nasty weather earlier in the week.

As nesting conditions vary from year to year, waterfowl numbers respond accordingly. The bag and possession limits established for hunters in the United States are the result of the efforts of state and federal management personnel. Through population checks and other management techniques, the status of a certain species can be determined. If a harvestable surplus does exist, guidelines are set up for each state to insure the continued well-being of that species and to allow equal hunting opportunity for all.

47 ...a Big I Bicentennial Travelgram

Historic Plum

Creek Cemetery

...a Big I Bicentennial Travelgram

Historic Plum

Creek Cemetery

The loud quack of a hen mallard interrupted our discussion and brought us back to the main purpose for being there.

The remainder of the morning was like a series of instant replays. Flocks of mallards came in from every direction and both blinds were getting shots as birds circled the slough almost continuously.

With some of the larger flocks moving in range, John and Jerry would knock a duck down and afterwards argue about who had shot it. Finally Dutch spotted a lone hen swimming in the decoys and decided to settle the dispute. He told John to stand up slowly and take her after she flew. O'Leary didn't want to shoot a hen so Jerry decided he'd give it a try. John agreed to witness the shot and back Wied up if necessary.

As the two stood up the hen kicked from the water. Jerry leaned into his 12-gauge pump and pulled but nothing happened. John, noticing his friend's technical difficulties, released the safety on his over and under and took aim. Meanwhile Jerry had ejected the spent shell in the chamber of his pump, cussed a bit and was now ready to shoot. Both guns went off at exactly the same time and the hen dropped.

"Nice shot Jerry," Dutch said as the hen hit the water.

"Jerry? I shot it," John said, turning toward Dutch with a surprised look.

'You didn't even shoot. I shot it," Jerry blurted out.

When they realized what had happened, their surprised looks turned to smiles and laughter resounded across the slough. This happy sound repeated itself when the hunters in the island blind heard the tale.

The day continued all too fast as friendships formed. Stories of football and the men who play it were told and retold as the two Huskers reminisced about former battles and opponents who hit extra hard.

Dutch told of days when ducks filled the sky and others when none were seen. Tales of the river as it once was filled our ears and brought a twinkle to his eye as the Peru "river rat" relived old times.

As we unfolded the canvas and covered the blind, evening was on its way. Men carrying gear and game crossed the field to their cars with a hint of regret in their eyes. The fellowship and fun of the day would never be repeated in exactly the same way no matter how many promises anyone made to get together again.

Thanking our host was a difficult task and words seemed rather small in exchange for a day full of life-long memories. After shaking hands and saying goodbye to John and Jerry, Dutch and I listened as the little engine of their sports car strained up the hill and out of sight. As the sound faded away, Dutch turned and asked me if I thought they had enjoyed themselves.

All I could say was, "you bet!" Ω

NEBRASKAlandTrading Post

Acceptance of advertising implies no endorsement of products or services. Classified Ads: 20 cents a word, minimum order $4.00. November 1976 closing date, September 8. Send classified ads to: Trading Post, NEBRASKAland, 2200 N. 33rd St., Lincoln, Nebraska 68503, P.O. Box 30370. DOGS HUNTING BRITTANIES-Championship stock, contact Dan Ahrens, 3228 So. 128th Ave., Omaha, NE 68144 or phone (402) 333-9060. VIZSLA POINTERS, all ages. Wcalso board and train hunting dogs. Rozanek Kennels, Rt 2 Schuyler, NE or phone (402) 352-5357. AKC Yellow Labrador-3 years old-has had one litter of eleven-professionally trained-serious inquiries only. Kent at (308) 237-9688. IRISH SETTERS, German Shorthairs, Labradors (black or yellow) AKC $40.00, FOB Atkinson. We do not ship. Roland Everett, Atkinson, Nebr. 68713. MISCELLANEOUS SUEDE LEATHER drycleaned. Write for mailing instructions Fur & Leather Cleaning, P.O. Box 427, Bloomfield, Nebr. 68718. FOR SALE: Canyon Country, Recreation Country, Hunting Country! This is the ideal land. Located in western Keya Paha County in Northern Nebraska. Some areas can be split off into 40-acre tracts. See Bob Gass Agency, Valentine, NE (308) 376-3760. GUNS-Browning, Winchester, Remington, others, Hipowers, shotguns, new, used, antiques. Want Pre-1964 Winchesters. Buy-Sell-Trade. Ph. (402) 729-2888. Bedland's Sporting Goods, Fairbury, NE 68352. OBWHITE AND CHUKARS: Adult birds available-Taking orders Now for hatching eggs and chicks for Spring of '77. Frank Roy, 517 E 16th St., Grand Island, NE 68801. Ph. (308) 384-9845. FOR SALE-Hunters Paradise and Retreat-160 acres improved on the Niobrara River where wild turkey and white tail deer are in abundance. 1/2-mile river frontage, modern Tstory insulated home, electric heat, contemporary fireplace. All offered on land contract with low down payment, low interest rates and easy payments. 160 acres improved on Elkhorn River, modern 2-bedroom home, being sold to settle estate. THOR AGENCY REALTORS, 107 East Omaha Avenue, Norfolk, Nebraska 68701. Telephone: 371-1314. CENTRAL Ontario-Choice 640 acre sportsmen's paradise still available-$20.00 plus $6.50 taxes yearly. Maps, pictures, $2.00 (refundable). Information Bureau, Norval 70, Ontario, Canada. APPRAISE AND/OR BUY U.S. coins, bills, and collections. Contact Profs' Coin Appraisals, P.O. Box 126, Wayne, NE 68787. DECEMBER 1976 FOR SALE: Harlan County Dam Lakefront Lot. Close to dock, airstrip, shore and good road. Great hunting and fishing, Don Haeker, (308) 928-2804. HAND-REARED Wild ducks; wood ducks, Mandarins, redcrested pockards, European wigeons, and others. Mrs. R. W. Hansen, 3315 Ave L, Kearney, Nebr. 68847. WAX WORMS; 500-$8.00; 1CXX)-$14.00, post paid, add 3% sales tax. No. C.O.D.'s. Malicky Bros., Burwell, Nebr. 68823. A NATURAL GIFT-Natural sheepskin rug by Layne. $30 each; call for your order or write Fur Things by Layne, 3325 E. Pershing Rd, Lincoln, Nebr. 68516, (402) 423-1989. HARLAN COUNTY Reservoir Lake lot. Deeded lot with tested well. Phone (308) 928-2804. METAL DETECTORS-$49.95 and up. Most brands available. Free catalog on treasure hunting tips. Spartan Shop, 335 No. William, Fremont, NE 68025 or phone (402) 721-9438. DUCK HUNTERS: Learn how, make quality, solid plastic, waterfowl decoys. We're originators of famous system. Send $.50, colorful catalog. Decoys Unlimited, Clinton, Iowa 52732. TAXIDERMY BIG Bear Taxidermy, Rt. 2, Mitchell, Nebraska 69357. We specialize in all big game from Alaska to Nebraska, also birds and fish. Hair on and hair off tanning. AVi miles west of Scottsbluff on Highway 26. Phone (308) 635-3013. CREATIVE Taxidermy. Modern methods and lifelike workmanship on all fish and game since 1935, also tanning, rugs, and deerskin products. Joe Voges, Naturecrafts and Gift Shop, 925 4th Corso, Nebraska City, Nebraska 68410. Phone (402) 873-5491. TAXIDERMY work-big game heads, fish-and-bird mounting; rug making, hide tanning, 36 years experience. Visitors welcome. Floyd Houser, Sutherland, Nebraska 69165. Phone (308) 386-4780. KARL Schwarz Master Taxidermists. Mounting of game heads—birds—fish—animals—fur rugs—robes—tanning buckskin. Since 1910. 424 South 13th Street, Dept. A., Omaha, Nebraska 68102. FISH Mounting Service. Specialize in all freshwater fish. Visitors welcome. Wally Allison, 2709 Birchwood North Platte, NE 69101, (308) 534-2324. GREAT PLAINS TAXIDERMY. True to life mounting of fish, birds, game heads, and animals. Graduate and experienced taxidermist. Pat Garvey, 5215 Ida Street, Omaha, NE 68152. Phone (402) 571-5630. WHITETAIL TAXIDERMY, Columbus, Nebr. 326416th Ave. East, Phone (402) 564-6885. Specialist in big game heads and game bird mounts. KINSMAN—Game heads, birds, mammal mounts full size, rugs and small game tanning. 10 years experience. (308) 995-6057, Holdrege, Nebr. 68949.AUTHORS WANTED BY NEW YORK PUBLISHER

Leading book publisher seeks manuscripts of all types: fiction, non-fiction, poetry, scholarly and juvenile works, etc. New authors welcomed. For complete information, send for free booklet R- 70. Vantage Press, 516 W. 34 St., New York 10001THE LINCOLN TELEPHONE CO.

SAVE 35% When you dial direct without operator assistance between 5 p.m. & 11 p.m. you save 35% on long distance day rates. Dial the distance yourself and SAVE.Browning

Our EXCLUSIVE DISCOUNT PLAN on all BROWNING products will save you up to 20%. This includes guns, ammunition, archery, clothing, boots, tents, gun cases, rifle scopes and fishing equipment. Inquire ... it will save you $$$. Big discounts on other sporting goods. OPEN 7 DAYS A WEEK Weekdays and Saturdays- 9:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Sunday - 1:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m.RISHLING'S GOOSE LORE

Notes on Nebraska Fauna...

GREEN-WINGED TEAL

NEBRASKA'S SMALLEST duck, most commonly found throughout the state in fall and early winter, is the green-winged teal. Some do stay through the summer to bring off a brood of ducklings. The scientific name is Anas carolinensis, but there are several local names such as butterball, lake teal, mud teal and redhead teal. Though smaller, the greenwing may be confused with other small ducks such as the blue-winged teal, cinnamon teal and bufflehead. The white or light buffy breast and green wing patch sets him off from the other teal, while the black-and-white tones of the bufflehead should exclude a mistaken identification.