NEBRASKAland

November 1976 60 Cents

NEBRASKAland

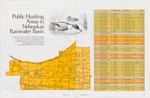

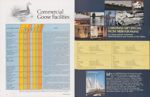

VOL. 54 / NO. 11 / NOVEMBER 1976 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Sixty cents per copy. Subscription rates $5 for one year, $9 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. commission Chairman: Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 Wee Chairman: Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-Central District, (308) 745-1694 2nd Vice Chairman: Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-Central District, (308) 452-3800 H. B. "Tod" Kuntzelman, North Platte Southwest District, (308) 532-2982 Richard W. Nisley, Roca Southeast District, (402) 782-6850 Director: Eugene T. Mahoney Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, Jr. Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: Jon Farrar, Ken Bouc, Bill McClurg Contributing Editors: Bob Grier, Faye Musil, Tim Hergenrader, Roland Hoffman, Bill Janssen, Butch Isom, Ben Schole Art Director: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1976. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska NOVEMBER 1976 Contents FEATURES THE WATERFOWL DILEMMA: DROUGHT, DISEASE AND DRAINAGE 5 SEASONS PAST: A History of Sandhills Waterfowling 8 HARBINGERS OF WINTER: Story of the Snow Goose 12 WATERFOWL CONTROVERSY: SETTING GOOSE SEASONS 20 WATERFOWL CONTROVERSY: SETTING DUCK SEASONS 22 DABBLERS AND DIVERS: NEBRASKA'S DUCKS 24 WATERFOWL MORTALITY: HOW THEY DIE 34 RETURN TO THE PLATTE: Spring Migration of Canadas and Whitefronts 36 HONKER HOMECOMING: Restoration of Canada Geese 42 PUBLIC HUNTING AREAS IN NEBRASKA'S RAINWATER BASIN 44 PUBLIC WATERFOWL HUNTING AREAS IN NEBRASKA 46 COMMERCIAL GOOSE HUNTING FACILITIES 48 COVER: Coloration of the "blue phase" of the snow goose is distinctive. The white cheeks are often stained a rust color from feeding in iron-rich soils. OPPOSITE: The end of a day's duck hunting on the Missouri River near Niobrara. Photo by Greg Beaumont. INSIDE BACK COVER: Hunter retrieving a runaway decoy on Loup River near Monroe. BACK COVER: Some of the 160,000 snow geese that fed in the cornfields of Plattsmouth Waterfowl Refuge last fall. 3

A CENTURY AGO waterfowl was exceedingly abundant Their decline paralleled that of other native wildlife but for a while they were less affected by man's encroachment of the land. Until recently, many of their nesting and wintering areas were isolated and generally undesirable for human use. During the early decades of this century, unregulated harvest by market hunters was their only real limiter. That has changed, of course, and now a more ominous threat, loss of habitat, is contributing to the continued decline of waterfowl populations.

There are exceptions. Protective regulations, restoration programs and habitat preservation and improvement programs by private groups and governmental agencies are bright spots on a generally gloomy horizon. It is popular to talk of "turning points." For our waterfowl resource, each year for the last 40, this year, and each year in the future has been or will be a turning point. To date, they have all been turns for the worse. The need to retain what precious little wetland habitat remains is acute. Drainage, in the prairie-pothole country of the United States and Canada and to a lesser extent in Nebraska, has been the grim reaper of wetlands. The pressure to push every possible acre into agricultural production shows no signs of letting up; it accelerates every year. Traditionally, the expansion of human populations and demands on the land have been at the expense of North America's wildlife. Waterfowl has been the most recent loser as wetlands, once considered "wastelands," are converted into production of food and fiber.

Solutions are seldom simple or universally accepted. The current controversy over the establishment of a Platte River refuge is a close-to-home example. Wildlife and human populations are on an ecological seesaw and only one can be up at a time. Ultimately the destiny of our waterfowl resource will be resolved by social, moral and economic considerations.

So important is this waterfowl dilemma we have devoted an entire issue to Nebraska's waterfowl. We offer no solutions and have strived only to provide a glimpse of what is at stake. The Nebraska Game and Parks Commission represents only one point of view. We hope that a balance between man's interests and waterfowl needs can be achieved. In the final analysis it will be the people that decide the fate of our waterfowl resource and the quality of life for generations yet unborn.

Special Issue Coordinator, Jon Farrar Photographs, unless otherwise credited, by jon Farrar Photographs for "Dabblers and Divers—Nebraska's Ducks" made possible through the cooperation of William Lemberg, Cairo, Nebraska Migration maps adapted from Ducks, Geese & Swans of North America, 1976 4 NEBRASKAlandThe Waterfowl Dilemma... Drought, Disease and Drainage

IT HAS BEEN estimated that North America's duck and goose populations numbered 500 million before the white man arrived. In stark contrast, fall flights in recent years have ranged as low as 30 million to as high as 120 million birds.

Why the decline in numbers? Under the pristine conditions that existed before the white man's arrival, population fluctuations were the result of natural acts such as periodic droughts. With the expansion of the original colonies NOVEMBER 1976 westward into the prairies in the 1800's, agricultural drainage and market hunting were added to natural factors as controls on the waterfowl population.

The destructiveness of wetland drainage during the past 100 years is staggering. Where there once existed approximately 127 million acres of wetlands in the United States, a 1968 study revealed that only 74.5 million acres remained. Of those remaining, only 9 million were rated as highly suitable for waterfowl. The Prairie Pothole Region of the United States, including the Dakotas, Minnesota, northwestern Iowa and eastern Montana, once totalled 74 million acres and produced about 15 million ducks each year. Drainage has reduced these wetlands to 36 million acres with an annual production of only 3 million ducks. The all-important prairie and parklands of western Canada, which in good years produce over 70 percent of the fall duck population migrating through Nebraska and the rest of the United States, escaped the early drainage frenzy. This area, known as the Prairie Pothole Region of Canada, suffered only minor losses prior to the mid 1960's. Wetlands there have since disappeared at a rate similar to that of the United States, however.

5 The Waterfowl Dilemma...

The history of North America's waterfowl resource has

been one of exploitation. Its future depends on how quickly

we move to arrest the loss of critical wetland habitat

The Waterfowl Dilemma...

The history of North America's waterfowl resource has

been one of exploitation. Its future depends on how quickly

we move to arrest the loss of critical wetland habitat

The last 50 years of the 19th century were the heyday of market hunting. The professional hunters, free from the limitations of hunting seasons and bag limits and utilizing such deadly devices as the punt gun and battery box, 6 were responsible for sending incredible numbers of waterfowl to the eastern markets. Initially, most of the harvested fowl were used as food. Later, accompanying sophistication of women's fashions, more and more of the birds were shot only for their plumage.

By the turn of the century, waterfowl numbers had declined to approximately one-third of the original 500 million. People became alarmed and demanded that something be done. Congress responded. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act, passed in 1918, gave the federal government the power to set seasons and limits for controlling migratory bird hunting. The act also did away with market hunting and the sale of migratory birds. The Migratory Bird Conservation Act of 1929 laid the groundwork for the present-day national wildlife refuge system by authorizing appropriations for land acquisition and habitat development. NEBRASKAland Legislation alone, however, was not enough to halt the downward trend in the continental waterfowl population. The depression and drought of the early 1930's left no money and very little water available for waterfowl use. The fall flights that once "darkened the skies" were reduced to 30 million birds.

The prairie nesting ducks have a breeding biology well attuned to the ever-changing conditions of the prairie. Most are sexually mature at one year of age, clutch sizes are normally large, most are persistent renesters, and all are relatively long-lived. These characteristics enable a population to remain stable during a prolonged dry-spell, and to virtually "explode" during the following wet years. Restricted hunting seasons imposed during the drought years of the 1930's insured an adequate breeding stock on which to base the population's recovery.

Legislation designed to acquire habitat and safeguard against future crises included passage of the Migratory Bird Hunting License (Duck Stamp) Act in 1934. This act insured a yearly supply of funds for wetland acquisition projects. The Pittman-Robertson Act of 1937 levied a tax on the sportsman's purchases of guns and ammunition. Revenue from this tax is then returned to the states on a percentage basis for use in wildlife conservation. Financed by this program, state wildlife agencies have acquired and developed, through 1974, about 1.5 million acres of waterfowl habitat. The Wetlands Loan Act (Accelerated Wetlands Acquisition Program) passed in 1961, authorized a loan from the federal treasury to speed up wetland acquisition. Originally a 7-year program, it has recently been extended to the 1980's because Congress failed at times to appropriate the required funds. Through 1974, 348,000 acres of waterfowl production areas were purchased under this program, primarily in the Dakotas, Minnesota and Montana.

A private program that has been highly beneficial to waterfowl began in the aftermath of the early 1930's. Ducks Unlimited has raised over $35 NOVEMBER 1976 million for the development and restoration of waterfowl breeding habitat in Canada since its inception in 1937. D.U.'s accomplishments: 2 million acres under reservation, 1.8 million acres under habitat management, 11,000 miles of shoreline essential to nesting waterfowl, and over 1,200 projects throughout Canada.

By 1976, the continental waterfowl population had made some promising comebacks. The fact that ducks and geese are still around in sufficient numbers to be enjoyed is reason enough to be thankful. The recovery of the wood duck from near extinction in the early 1900's has to be one of the most spectacular stories of wildlife conservation. Canada geese are more numerous now than in a long time. The combined goose populations of the Atlantic, Mississippi and Central flyways increased during the period from 1955 to 74 by 138.6 percent, 169.5 percent, and 70.6 percent, respectively. The Giant Canada goose, once thought to be extinct, was rediscovered in 1962 and has responded so well to state and federal restoration programs that limited hunting seasons are now enjoyed. The canvasback and redhead ducks have made significant recovery strides the past two years through a combination of good nesting conditions on the Canadian prairie and continued restricted hunting regulations.

Population-wise, all other species of ducks and geese are in reasonably good shape with the possible exception of the hooded merganser. In the past, research was conducted mainly on the more popular species— the mallard, Canada goose, blue-winged teal and wood duck. Recently, this practice was altered and most species are subjects of research studies. The result of this effort should be a better understanding of the population dynamics of each species, which in turn should lead to better management programs.

The continental waterfowl picture is not without its negative side, though. The central problem continues to be the decline in available habitat. Although progress has been made in saving the wetlands in the United States and Canada, such things as agricultural drainage, urban expansion and highway construction continue to off-set these gains. Furthermore, the acquisition and management programs are beginning to run into difficulties. The North Dakota Stockmen's Association went on record this past summer as opposing future land acquisition for wildlife purposes within the state. Canadian farmers, irate at the insufficient payments made to compensate for waterfowl depredations on their grain fields, are becoming increasingly anti-wildlife. In addition to draining their own wetlands, they oppose management programs on adjacent lands that would in the long run result in more losses to them.

From a continent-wide standpoint, land acquisition has recently become confined to the nesting grounds in the United States and Canada. Acquisition and the accompanying protection of vital migration stopping points and wintering areas has lagged, and is now beginning to prove detrimental to the waterfowl resource. Nebraska's Rainwater Basin is a prime example. Drainage, development, channelization and flood control projects have turned traditional wintering areas into duckless and gooseless expanses.

Disease outbreaks, once limited almost entirely to periodic epizootics of botulism, are becoming increasingly common. Avian cholera alone was responsible for 60,0(30 known waterfowl deaths in the United States in 1975. This list, by no means complete, illustrates the fact that waterfowl conservation is again approaching a crisis.

The future of North America's waterfowl resource depends on how quickly and successfully these negative factors are corrected. Without such things as an incentive program for landowners to preserve wetlands; without the continued support of waterfowl management programs; without pollution control and cleanup; without continued research on population dynamics, disease control and prevention; and without a balanced acquisition program covering the nesting grounds as well as migration and wintering areas, the future holds very little promise. Ω

7

Seasons Past

For a century, sandhill marshes have drawn hunters from all across the country

8WHEN THE NORTH wind begins its fall music through the scattered bullrush and cattails, and the sky over Nebraska's endless Sandhills shows a thin wedge of red through a line of scudding gray, long strings of moving waterfowl tell that another hunting season has begun.

For many hunters, warm recollections of seasons past have their origin in the hundreds of potholes, nameless marshes and lakes scattered over this rolling landscape of grass and marsh. For most hunters, times have changed. The countless strings of canvasback and redhead moving to the rich feeding areas of the Sandhills will never again appear. There will not be another generation of hunters that can warmly recall days of superb gunning.

Those halcyon days of duck hunting are gone now, but mute testimony of the spectacular shooting afforded by the rich Sandhills lake country can still be found—the long-rotted remains of blinds, a crumbling skeleton that once was a duck boat, a stray decoy anchor and an occasional decoy remnant.

A shallow notch on the east end of Big Alkali Lake is a natural flyway between lakes. As you walk through the blowouts there, it becomes evident that an early hunter recognized and took advantage of this pass. The bare sand behind NEBRASKAland

As a research biologist for the Game and Parks Commission, my studies and travels have taken me through many parts of the Sandhills over the past 16 years. Waterfowl and their early hunting in this region have always intrigued me, but never have I been able to take a detailed look into the past as it related to hunting. All the incidental bits of hearsay, stories, and observation of oddities that had occurred over the years seemed to beg for setting down as a story.

A real clue to past conditions turned up in the form of the U.S.D.A. Bulletin

numbered 794 and entitled Waterfowl and their food Plants in the Sandhill region of Nebraska. Written in 1920, this work documented much about hunting

and the area during 1915 when an early biological survey was made. While most

of the work was directed at evaluating waterfowl foods on the many lakes, portions of this early study looked at laws, people and waterfowl of the area, and

NOVEMBER 1976

9

offered insight into waterfowl and hunting in the Sandhills.

offered insight into waterfowl and hunting in the Sandhills.

While the tales of "classic" duck hunting are most often associated with the Eastern Shore and Chesapeake Bay country, the upper Mississippi or the Arkansas oak bottoms, few realize that a number of lakes in the Sandhills were also a mecca for thousands of hunters during the early 1900's. It wasn't uncommon to see residents of San Francisco or New York cascading off the train at Wood Lake in the north, or at Mullen or Hyannis in the south, in order to partake of some of the finest waterfowl hunting the continent had to offer. The lakes of eastern Cherry County and those of Garden and Morrill counties were usually their destination.

As in many areas of the country prior to enactment of Federal migratory bird laws in 1913, spring hunting of waterfowl was very common in the Sandhills. A number of clubhouses owned mostly by hunters from outside the region attested to the fact that spring shooting occurred regularly. Federal regulations prohibiting spring shooting were fairly well accepted, though, particularly by people who lived in the region, since they regarded the ducks as undesirable and unfit for food at that time of year. By the mid 1900's it was evident, even in Nebraska, that waterfowl numbers were declining. The Sandhills remained, however, a stronghold for both breeding and migrating birds. Land use changes were just getting underway in other parts of the state. Wetland drainage, that would eventually see the demise of the majority of high-quality waterfowl marshes of the state, didn't take the productive marshes and lakes of the Sandhills. This was grassland never meant for the plow; native grasses were the key to holding the rolling hills in place. The needs for breeding and nesting were ideally met by the vast number of lakes and marshes scattered over the region. Coupled with the ranching economy that was necessarily geared to grassland management, the Sandhills was destined to be the principal waterfowl production area of the state, as well as being a highly attractive migration stop.

In 1915, some 9 duck hunting clubs were scattered over the good lakes of eastern Cherry County. Dewey, Red Deer, Marsh, Hackberry and Molly Marsh lakes were the primary areas of club development, but other clubs undoubtedly existed. One of these, the Red Deer Hunting Club, was started in 1904. Some 72 years later, this club is still active with a membership of 32; 7 more than the original 25 members who founded it.

To help recall some of the early days of gunning in the Sandhills, I was fortunate to be assisted by Reg Woodruff of Lincoln.

Red Deer Lake first hosted Reg Woodruff in 1918. Upon talking with this soft-spoken gentleman, it was evident that his interest in waterfowl has waned little over almost six decades. The paintings of waterfowl, a wooden decoy, and the general character of his office bespoke an appreciation for a natural resource that has seen many changes over the years. With a twinkle in his eye, his voice brought back those feelings that every duck hunter, regardless of age, has indelibly etched in his mind-the physical hardship of cold-stiffened fingers, toes that have lost feeling, and the trauma of an unexpected dunking in frigid water; these are the rigors of waterfowling that every duckhunter knows. But then the twinkle misted, the voice changed pitch ever so slightly, and his spoken words began to form a verbal picture that hunters of today will never be fortunate enough to see. . . .

"Redheads and canvasback were the best ducks in those early years. They came in by droves. Wild rice and sago pondweed were abundant then, and must have been a feeding paradise to those birds. . . .

". . . We usually picked our spot on the lake the night before. In the gray pre-dawn we would head down to the beach, ready to pile in our "tippy kidney" boat and head to the blind. At first our blinds were partially submerged tanks, but these often shipped a lot of water and were hard to stabilize. The lake bottom was goulash for about 15 feet. Later we went to platform blinds. Our earlier decoys were cans and redheads—mostly Masons. Later we went to mallards, when the diver numbers began to drop. . . .

30". . . Mallards have pretty much been our mainstay over the years, and there have been some memorable mallard hunts. Ballards Marsh was a great shooting spot—particularly for mallards. We headed out from our south landing one morning for the "lily pond" and the greenheads cooperated in every way. My partner that day could shoot either right or left-handed—and it was a good thing because it spread the hurt of the many recoils of fast shooting. We had a shoot that morning that I'll never forget. . . .

". . . But hunting wasn't the only thing that made Sandhills shooting memorable. Getting to the lakes in those early days wasn't exactly easy. The roads were only sand trails, and getting lost wasn't hard. We took off from Brewster one time in our Model "T' headed for Red Deer. Before long, it was obvious that we were a great ways from nowhere. Ending up at a lone cabin and seeing a ph^one wire, we cranked up the phone. After ringing and ringing, I gave up, started to back out, and the phone rang. Answering it, I asked the voice if they knew where we were. An answer came back, "Sure, do you know where I am?" I sure didn't, and shortly the voice said 'You're on the east part of our Ranch 54—if you follow the trail east of the house you'll come up to the main ranch house'. Well, it was hot and we set out and before long drove up to a ranch house and corral. A bunch of cowboys were sitting around, and it didn't take long to ask if anyone would be willing to take us on to Red Deer Hunting Lodge. One fellow volunteered and we began following him across the prairie. Finally, he stopped and told us that we could follow a trail on and eventually get to Red Deer. Based on our previous pathfinding ability, we weren't about to set off on our own again. With some additional bribing he consented to take us right to Red Deer. We were happy as could be when the lights of the lodge finally appeared—we would have been out there all night otherwise. As it turned out, we were on the old trail from Brewster to Wood Lake where it normally took a team of eight horses to pull through. . . .

". .. Wood Lake was quite a town in those days, as the train stopped there. The Lakeland Hotel was our usual meeting place. The team and wagon that came to meet us had long seats on each side and was often fitted out to supply a picnic as we headed across the 18 miles of sand trail to Red Deer. The many sand dunes didn't make the going real easy, and on at least one occasion we managed to tip the wagon over, losing our lunches, keg of beer and everything. ..."

The once common sounds of hundreds of whistling wings has diminished. Even the seemingly inviolate lakes and marshes of the Sandhills have changed. As is often the case, man has been the principal agent. Whereas the land itself has seen little change, the introduction of carp into many of the Sandhills lakes has brought about pronounced changes—mostly to the detriment of waterfowl. Where lush stands of submerged and semi-submerged aquatics such as reeds, rushes, pond, smart and duck weeds once formed the highly sought-after waterfowl food sources, only turbid, muddied waters now exist. As a rooter and bottom feeder, the ubiquitous carp brought about significant changes on many of the lakes. Devoid of what was once a sumptuous spread of highly prized foods, the lakes are now bypassed by migrating birds. Man, in his never-ending tampering, has brought about one more change-a change that along with other inroads on this fragile region has acted to eliminate the once productive nature of the land.

But ducks weren't the only thing that Reg Woodruff recalled. Working on the clubhouse at Red Deer in the spring, the Sandhills were abloom with the spectacular display of color that is familiar only to those who know this land . . ." the spring colors were unbelievable-just like the Painted Desert—it was a carpet of wildflowers".

And so, as with any dyed-in-the-wool duck hunter, ducks were not the only prizes stored away among life's rewarding experiences. The ice-covered lake, an unstable boat, the lost trails, sunrises, and even wildflowers are just a fraction of the puzzle pieces that have a way of fitting into place to make hunting worthwhile. For Reg Woodruff, his life has been enriched remarkably through a lifetime association with waterfowl—an association in which waterfowl have in some immeasurable way been the catalyst to a greater appreciation of a unique area during a unique time. Ω

11

Harbingers of Winter

THE SIGHT is incredible. It is beyond comprehension or description; somehow primeval. It overwhelms the senses, stirs the emotions. The morning's heavy air is charged with a din of calls. Before me are 160,000 snow geese; they cover a small lake, finger up the dike walls and climb into the sky. The sun burns through the low-lying fog over a fringe of cottonwoods along the Missouri.

13

It is mid November and the snow goose population has peaked.

More than a month before, the first flights had snaked their way along the Missouri to Nebraska's floodplain grainfields and wet meadows. Others followed as Dakota's open waters were locked in winter's grip. During a mild year they would string south for three months, idling their way to wintering grounds in western Louisiana and east Texas. In all, over half a million snow geese would pass down the Missouri River; more than one fourth of the continental population.

The fall journey of the snow goose is long, covering some 2,000 miles, but they advance at leisurely pace, stopping often to feed and rest. Thirty years ago, these geese probably flew direct from their staging grounds on Hudson and James bays to their wintering grounds on the Gulf Coast. Many still do, but others have changed their traditional migration pattern, stopping more frequently as waterfowl refuges and grain fields cropped up along their route.

During late September these snow geese leave their nesting grounds along the west shore of Hudson Bay, flying southwesterly across Ontario and central Manitoba to Sand Lake National Wildlife Refuge on South Dakota's northern border. Here, they feed and rest, building back fat reserves depleted during the arduous days on the breeding grounds.

By mid November, winter has moved into South Dakota's prairie and the snow geese at Sand Lake are forced south. In a direct flight, they knife across northeast Nebraska. Many stop at DeSoto Bend National Wildlife Refuge near Blair, others continue south to the Plattsmouth Waterfowl Refuge or even to northwest Missouri and the Squaw Creek Wildlife Refuge. Some may move back and forth between refuges if winter temporarily relents.

As with Sand Lake, the concentration of migrating snow geese at De Soto Bend is a recent phenomenon. Its 700-acre horseshoe lake and surrounding floodplain did not become a federal refuge until 1959. By the late 1960's and early 70's, 300,000 snow geese were stopping there during fall migration. The Plattsmouth Refuge followed a similar pattern, increasing from 500 snow geese using the area during the fall of 1959, to 80,000 in 1969 and 160,000 in 1975.

Migration flights of snow geese are staggering. They are probably the most numerous geese in the world with winter populations estimated at around two million. Commonly, they move in flocks of 100 to 1,000 birds, but when weather conditions prompt major movements, they may string together into passages of 5,000 or more. Their flocks are less organized than the precision "V's" of Canada geese, more often taking the form of irregular lines or sweeps. Their undulating flight habit has earned them the colloquial name "wavie".

Mass movements are only part of the aura surrounding snow goose migration. Their call is distinctive. They are perhaps the most vociferous of all waterfowl, calling constantly during migration, when feeding, resting and even during the night. The clamor of thousands of snows overhead or greeting new flocks to the security of a refuge is the purest expression of wildness.

The snow and blue goose are actually

different color phases of same species

The snow and blue goose are actually

different color phases of same species

During their stay on the Missouri River refuges, snow geese become even more gregarious, concentrating in numbers unknown to either the nesting or wintering grounds. Their behavior becomes more social, their daily habits more attuned to those of man.

At night they crowd together on the lake for safety. As ice closes in on the open water, some birds are forced to overnight on the banks, but early in the season the lake is like a living river of birds. Their numbers are incomprehensible at night. The human mind cannot grasp the meaning of so many birds illuminated on a moon-streaked lake. And, incredibly, only two thirds of the geese are visible to the eye. Interspersed among the snow geese are nearly as many blues, lost in night's shadows.

It seems as if the lake could hold no more, yet when night-flying migrants come from the north, thousands at a time, they are absorbed into the flock without noticeably swelling it. On clear nights, the calls of thousands of geese and plummeting, shadowy forms fill the sky. A confusion of noise announces that all is well; silence is often a sign of disturbance—a roving coyote along the shoreline, a low-flying jet or the buffeting of an autumn storm.

Before the dawn, a contagious excitement sweeps through the resting geese. Their calls become more frequent and intense, each feather is oiled and arranged in preparation for the day. Small groups take wing, circle overhead, calling nervously before drifting out of sight. Some birds leave for the wheatfields or corn to feed, but if the day promises to be warm, the geese may stay on the lake until mid morning. Most often there is a mass departure to feed, but early in the season, when food is near at hand, birds sometimes pour over a dike and into the fields like a marching band of outsized army ants.

Tender shoots of wheat and patches of native plants are cropped by the first arrivals in October. As winter presses down upon them and choice succulent greens are stripped, the snow geese turn to carbohydrate-rich waste grain. They are reluctant to enter unpicked fields where they are vulnerable to attack by predators, but roll over picked corn, a huge living machine of birds where individuals seemingly lose all identity.

If undisturbed, the geese sometimes spend the day in fields feeding on grain, loafing and picking at cool-season greenery. Sometime during the day they return in small flocks or family groups to the lake to drink. Occasionally, thousands wili leave the fields for water. Even before you carfkee the low-flying geese you hear their silence, the second or two before a roar of wings puts them into the sky. They barely clear the lake's dike; they fill the northern sky. Their shadows run down the bank and disappear at the water's edge like legions of lemmings marching to the sea.

Ten thousand snow geese, maybe more, splash haphazardly to the water at mid lake. Stuffy-hailed behaviorists can say what they will, these geese rejoice in the 16

Some birds may stay on the lake and its shores, selecting the side that affords shelter from the wind. Midday is an idle time for snow geese during good weather. They stand, first on one leg then the other, looking about, occasionally preening, more out of habit than necessity. Some fold their stubby legs up under the body and rest on the frozen ground, their head thrust neatly between the folded wings. They seem unconcerned, but among the thousands, hundreds are alert.

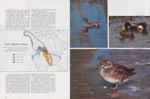

Whether on the wing, in the water or poised neatly on one leg in a wheat field, the snow goose is a distinctive bird. Until the early 1960's the "blue" and the "snow" goose were considered similar but separate species. From observations on their breeding grounds and in captivity, it has since been established that they are actually different color phases of the same species. The two color phases interbreed freely but prefer mates of their own type. Crosses of the two color phases produce young of either one type or the other and only occasionally birds of intermediate color.

The mature blue-phase snow goose has a white head, commonly stained rusty brown from feeding in iron-rich bottom soils. The feet and legs are rosy red and the bill, pink. The body is a slate-gray. The immature "blue" is drably garbed in brownish gray with a white chin patch. Its legs, feet and bill are a grayish brown. The sexes are superficially indistinguishable.

The mature snow-phase snow goose is completely

It appears that the two color phases of the snow goose have resulted from environmental selection; different weather conditions favoring each color on the nesting grounds. During short, cool summers, when nesting must take place with some snow cover, the snow-phase blends better with the land and is more successful at escaping the attention of predators. Consequently, more "snows" are hatched and return to nest the following year. Conversely, with warm summers and snowless terrain, the blue phase has the advantage and is the more successful nester. An additional factor is that the snow phase initiates nesting earlier, and during short summers is more apt to rear their young to the flight stage before winter forces migration.

Fifty years ago the blue phase was uncommon. Then, the mean temperature increased over North America and the blue phase began to increase. In 1955 it was estimated that 62 percent of all snow geese were of the blue phase. Since 1950, though, mean temperatures have been declining and the snow phase has been on the increase. By 1974 it was estimated that about 50 percent of the snow geese were of the white phase. The ratio of snow to blue goose varies from nesting colony to nesting colony. On the west shore of Hudson Bay the snow phase predominates and hence most snow geese taken by Nebraska hunters are white birds.

Probably there is little environment selection for one color phase or the other away from the nesting grounds. Hunters seem to prefer the adult snows when they have the choice, but it is the inexperienced birds that are most vulnerable to the gun. In a large flock on the wing, it is the mature snow that draws attention, but at close range, the adult blue with its distinctive markings demands most notice.

Young geese are almost always in the forefront of a feeding flock. They are more brash, less cautious than the other birds. Without caution they trickle down corn rows like water running over dry land, following the less laborious course until something catches their eye. Behind them come the adults and less adventurous young. For all their courage, though, the immature birds are often robbed of their choicest finds by more aggressive adults. Squabbles over the ownership of an ear of corn errupt, with vigorous pecking and dislodged feathers from the weaker goose's back-side the usual outcome.

In just two or three minutes, a full ear is raked clean by serrated bills. Corn hanging on the stalk is stripped with amazing efficiency, only a handful or kernels falling to the ground. During cold weather, the flocks feed frantically in the grain. The back birds constantly fly to the lead of the flock. At sunset, geese begin stringing from NEBRASKAland

Eventually, winter closes in on the Missouri River refuges, sometimes in late November, but in mild years there may be thousands of snow geese along Nebraska's eastern border until Christmas or later. Eventually they are all forced south where they fan out over the wetlands of the Gulf Coast. In the marshes, the cutting edges of the mandibles that so efficiently stripped corn from the cob in Nebraska, will tear rootstocks of aquatic plants from the shallow water.

In late February or early March the snow geese will renew their cycle, impatiently following winter's retreat up the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. Their numbers swelled by birds from the Mississippi flyway, one million snow geese will leave the Missouri River below Sioux City and fly to Sand Lake National Wildlife Refuge and then to the Devil's Lake in North Dakota and on into Manitoba. Here the snow geese wait before departing en masse for western Hudson Bay and points north. Another population of about 25,000 that winter in north-central Mexico and south-central New Mexico, will migrate to northwest Saskatchewan to nest. About 10,000 to 15,000 of those geese stop over north of Alliance in western Nebraska each spring.

Again, the snow geese are gone from Nebraska, but their passage is etched in the minds of those that watch such things. The calls of those first migrating flocks in the fall bring with them the promise of winter and stir the hidden yearnings of man. They are the harbingers of winter; our symbol of wildness lost. Ω

19

Waterfowl Controversy

Setting Goose Seasons

IN 1969 THE Nebraska goose season opened October 1 and ran without interruption through December 25. The entire state was open to goose hunting and the daily bag limit was five geese, not to include more than one whitefront and one Canada, or two Canada geese. Last year there was a split season running from Oct. 4 to December 21 with 7 days closed at the end of October. One Canada or one whitefront goose was allowed in the daily bag of five geese. A goodly portion of the Sandhills was closed to the hunting of dark geese. Designated areas in western and north-central Nebraska either opened later or closed earlier than the remainder of the state.

In six years, goose hunting got complicated. Regionally, goose hunters would like to see regulations better tailored to the migration patterns of birds passing through their area. In response, game managers have attempted to localize regulations. To further complicate the setting of goose seasons, restoration Canada geese are now wintering along the North Platte River. The result is a head-scratching problem of coming up with a goose season that is acceptable to the Missouri River snow goose hunter, the North Platte Canada goose hunter, state game biologists, Central Flyway members and federal wildlife agencies. Three of those diverse views follow.

WE'RE NOT AS concerned with the Canada geese as we are the snows and blues. We just don't get that many coming through. Our best snow goose hunting can come as early as September 25 and is generally good through the first week in December.

Anything would be better than a split season. A split season is a disaster as far as the Missouri River hunters are concerned. Three or four years ago the season was split on the last two days of October and the first day of November. During that time the whole push of lesser Canadas came through Nebraska along the upper Missouri. Our snows and blues and the push of big Canadas generally comes through about the 25th of October. If the seasons happens to be closed then, we can completely miss the Canada flights or the peak days of snow goose migration in our area.

We lost two weeks of our best goose hunting last year when the opening was about a week later than usual and the split was the last week of October. I know the Game Commission has a tough job setting a season to satisfy all the hunters. Short of an 85-day season like we used to have, probably nothing would cover all the migration times in Nebraska.

Ideally, we would have a season that opened on about the 25th of September and ran through the first week of October. Generally a lot of the snows and blues pass through before our season even opens. It isn't that we don't want the Canada goose hunters in the west to have good seasons, and I'm sure they think the same thing. About the only solution is separate seasons for the east and west.

THE SNOWS AND blues arrive pretty early on the Missouri River and I don't blame those people one bit for wanting an early goose season. But the Canada goose hunters in western Nebraska have to live with that same season. The first 45 days of the seasons we've had the past few years are no good to us whatsoever.

What we want is a two-goose season that could start as late as the first of November and run through to the first of the year. Or, we would be satisfied with a two-bird season whenever the state wanted to open it, and then cut back to a one-bird limit after Thanksgiving. Give or take a few days, our big geese come in around the 15th of November. If it takes a cutback to one-bird limits late in the season to keep the population in good shape, we'll live with it. We're just as concerned about those geese as the state is.

The geese on the refuge aren't really molested that much up until the time that the lake and river freeze over. That chases them off the reserve and that is when we start getting some decent hunting. This is about the same time we start getting Canadas from the north. In recent years the season has closed prior to that time. It doesn't make any sense to us to cut back on the harvest when the population is reportedly increasing.

FOR MANY YEARS the setting of goose season dates has been the most controversial issue facing biologists with the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Problems develop because of the different migration patterns and times for the snow goose along the Missouri River and the Canada goose in the Panhandle.

Snow geese begin their migration along the Missouri River in late September, and hunting there would be best as early as the federal framework allows. However, at the time snow geese are moving down the eastern border, the Canada geese that ultimately arrive at the upper end of Lake McConaughy are not even beginning their movement south. These Canadas do not begin appearing in any significant numbers until mid to late November.

The problem develops because the regulation framework for the goose season, as established by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, does not allow for enough days to span both migration periods. In recent years we've had a 72-day goose season. This has been further complicated by a terminal date of about the 7th or 8th of December for Canada goose hunting. In 1975 this terminal date was changed to allow Canada goose hunting throughout most of the state until December 21. With the earliest possible opening of October 4, and a terminal date of December 21, the 72-day season was not able to span both periods without requiring a split. Regardless of when the split comes, it is going to have an adverse effect on some hunters in the state.

We feel a solution to this problem has been found and offered this year by the Fish and Wildlife Service. The solution to the east-versus-west goose hunting controversy is separating the snow goose season from the Canada— whitefront season. This will allow an early snow goose season during their primary migration period, and a later opening on Canada geese allowing hunters in the west an opportunity to hunt the December period when those birds are most common.

Canada goose hunting in the western part of the state has been complicated, though, by new terminal dates imposed by the Fish and Wildlife Service to protect restoration geese. The restoration program involves the reintroduction of large Canada geese into areas where they occurred prior to the settlement of the Dakotas and Nebraska. The establishment of large Canadas has created considerable controversy within the Flyway. Nebraska feels that these birds have a good chance of becoming established even with a late terminal date during the third weekend in December.

There are many biological considerations involved in separating snow and blue goose regulations from Canada and whitefront regulations. The separation of seasons will have little or no impact upon the overall harvest or the overall population status of snow geese. They are arctic nesters and their populations are doing very well. The potential threat of overharvest occurs on Canada geese, which normally arrive in the state about Thanksgiving and winter in south-central and western Nebraska. These populations have been growing slowly over the years and a watchful eye must be kept so that the harvest does not reduce wintering populations. The number of Canada geese wintering in the state numbers about 18,000. This is far more Canadas than wintered here only 10 years ago. Therefore, it will be to the Canada goose hunter's benefit not to force the issue of a later season. As the number of Canada geese wintering in Nebraska increases, so will hunting opportunity. If we overharvest our goose population, we will be the ones to suffer in the future with reduced hunting opportunity. The overall objective of goose seasons is to provide maximum hunting opportunity within the tolerance of the resource.

Waterfowl Controversy

Setting Duck Seasons

TEN YEARS AGO duck season opened on October 15, closed on December 13 and hunters were allowed to shoot three ducks daily as long as they didn't have more than two wood ducks, mallards or canvas-backs. Last year there were duck hunters in the field as early as October 4 and as late as January 1. If the hunter watched what he was shooting he could come home with ten pintails, gadwall or teal. In one decade, season length has increased and bag limits have become more liberal, resulting in more complicated regulations such as special late season hunts, point system bag limits and split season. In general these special regulations have improved the duck hunter's situation during a time of declining waterfowl habitat At the same time, they have made it better for some hunters than others, depending on where they hunt and when they get their movements of ducks. Two examples and a game biologist's point of view follow.

I FEEL THAT the boundry line for High Plains, late season duck hunt, is too far west. Our flight in this area is definitely as late as at North Platte. The first three weeks of the duck seasons in recent years haven't been any good for us at all. We just don't have the ducks on the river early in the season. Our duck shooting doesn't really start until the last week or so of October.

Our best hunting last year was the last two weeks of the season and we still could have had good shooting three weeks after the season closed. Most years we could hunt mallards on the river right up to Christmas if the season ran that long and there's enough open water to hold ducks.

I don't think that the split in the son hurts our hunting. I think the split season probably gives the puddle duck hunters on the lagoons a little more shooting. The only thing that I feel is that the last half of the season doesn't run long enough. A lot of river hunters are paying good prices for river front leases and the season is just too short to justify it.

Now I'm not looking at the total picture, but right here we get our ducks and our best duck shooting late in the year. I know it's real tough Si ting seasons that are going to satis hunters in every area of the state.

DEPENDING ON THE year, when the first blast of cold weather comes, the break in the season can hurt our mallard shooting in the basin. We always have ducks around during the season break, mostly teal and other puddlers. But usually you have only three or four days of good shooting on the big mallard before the basins freeze up. If that comes during the break we're out of business.

One of the best duck hunting situations we've had in the rainwater basin was the early teal season. This was beautiful for us because we get good numbers of early teal. It's too bad we had a few hunters that shot at everything that flew.

I suppose if I had my choice I'd just as soon have the season open early and go straight on through to freeze up. I really don't have any complaints, though; I go when I can and enjoy it. The early October opening is generally acceptable; things are starting to get pretty and it's cooling off a little bit. Mosquitoes aren't such an annoyance.

Generally we freeze up around Thanksgiving in the basin. Last year we never did get into the mallard shooting real good. The water froze up early and the mallards didn't come down until late. By the time they hit our area we didn't have any water left. Most years we get our mallards in the middle of November so the split in the season doesn't affect our mallard shooting.

All things considered, we're probably better off with a little longer season and losing three or four days in the middle of October during the split. Sometimes it'll put us out of business but then that is the way it goes.

DUCK POPULATIONS have shown a marked recovery from their lows of the early 1960's. However, more and more hunting pressure is being placed on the birds throughout all the flyways. Because of this it has becorhe necessary to maintain existing season lengths in spite of the increase in the waterfowl populations.

The opportunity to hunt ducks exists in Nebraska from the beginning of September through January. The season framework, as established by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, normally allows for seasons to run from October 1 through the second weekend in January. However Nebraska is limited to selecting a season of no more than 60 days which may be split into two portions. The problem that arises is attempting to satisfy the early season duck hunters, mid season duck hunters and late season duck hunters, all within a 60-day period.

The marsh hunting that exists in south-central Nebraska and in the sandhills is best in early October and diminishes as the season progresses. Duck hunting is also at its best early in the fall on farmponds, primarily in the eastern third of the state.

Conversely, the best hunting on most of the Platte River and many other river systems in the state is probably during the early part of November. It is during this time that the mallard migration peaks. November mallard hunting can also be important to farmpond and marsh hunters if their water has not frozen up. Duck hunting becomes more restricted as November progresses but improves in areas with large concentrations of wintering mallards.

The establishment of the high plains mallard management unit in western Nebraska provided some additional late season hunting. From banding returns it was clear that mallards moving through Nebraska west of the 100th meridian were subject to less hunting pressure and lower mortality than those migrating through to the east. Because of this we have had an extended season in western Nebraska in recent years.

The higher mortality on mallards in the eastern portions of the Central Flyway results from high population centers, more hunters and consequently more pressure on migrating ducks. Also, ducks migrating down the eastern portion of the Central Flyway commonly drift east into the Mississippi Flyway and are subjected to more intense hunting pressure. Mallards west of the 100th meridian take a more direct flight to wintering areas, remain in a less populated portion of the flyway and escape the heavy hunting pressure.

Mallards wintering between Grand Island and Cozad on the Platte, and the flock at Harlan County Reservoir, exhibit characteristics similar to both the high plains and the low plains populations but are more like the eastern flocks. Consequently they are not included in the more liberal season.

For several years early season hunters had the opportunity to participate in an experimental teal season that ran for nine days in September. At the end of the experimental stage it was determined that states like Nebraska that had significant waterfowl production had too high an incidence of illegal kill of ducks other than teal. Because of that, the early teal hunt was not offered to Nebraska on a permanent basis. It appears unlikely that Nebraska will ever have such a season again.

It is the intent of the Game Commission to allow equal hunting opportunity for all segments of the waterfowl hunting fraternity across the state. When the number of days allowed in the season is limited by federal agencies, it is often impossible to achieve this objective.

vers maintain their balance out of the water with great difficulty, limiting their feeding opportunities and ultimately their numbers. Divers infrequently visit grain fields; the size of their populations closely parallels the supply of high quality wetiand habitat.

Puddle ducks leap vertically into flight while divers characteristically "walk" or run across the water before lifting into the air. On the water, divers ride lower than puddlers. The diver's short tail offers a good clue to identification in flight and, in many cases, their feet are visible. The wing patch on puddlers is usually iridescent and bright.

Most duck populations, but especially the canvasback and redhead, have not fared well during this century. Because of their superior table qualities, market hunters relentlessly shot the "can" and redhead until special protective regulations were imposed in the mid 1930's. Loss of nesting habitat, however, continued to contribute to their decline. Drainage of wetlands in the prairie pothole country was stepped up following World War II and the number of canvasbacks and redheads plummeted still lower. The continental canvasback population declined by 53 percent during a 20-year period from the mid 1950's to the mid 1970's in spite of being afforded complete or partial protection.

In recent years, with even more restrictive hunting regulations, both canvasbacks and redheads have made significant comebacks. In 1976, redhead populations were estimated to be up 36 percent and canvasback populations up 21 percent from the previous 20-year average. But neither species is abundant; in fact, the canvasback is the least abundant of the common ducks in North America; their population estimated at 560,000.

Four other diving ducks, the lesser scaup, ring-necked duck, common goldeneye and bufflehead, occur in Nebraska. They are most frequently encountered on large, deep lakes or reservoirs and along major rivers.

Two other tribes of ducks are represented in Nebraska by three species of mergansers and ruddy duck. The clownish little ruddy is the sole member of its subfamily in North America. Its group is commonly called the "stiff-tailed" ducks because of their habit of holding the spriggy tail at a jaunty, 45-degree angle to the water. Hunters probably know the ruddy by the colloquial name of "butterball", in reference to its fat, juicy oven quality and compact body conformation.

Three species of mergansers migrate through Nebraska: the rare, red-breasted merganser, the occasional and distinctive hooded merganser, and the frequently encountered common merganser. Better known as "fish ducks", the mergansers are large streamlined birds. It is estimated that some 235,000 mergansers are in North America, of which about two-thirds are common mergansers and less than 10 percent, hooded mergansers. Some 10,000 common mergansers overwinter on Nebraska's open reservoirs and rivers. During the late 1940's, as many as 50,000 were reported on Lake McConaughy.

Several other species of ducks are known to overwinter in Nebraska. Occasional green-winged 28 teal are sighted, and some American goldeneye, at times as many as 10,000, have been reported on Lewis and Clark Lake and Lake McConaughy. The primary species of duck encountered in Nebraska during the winter months, though, is the mallard. Since 1954 an average of 230,000 have stayed along the Platte River and at some major reservoirs. A record high of 561,000 was reported in 1958.

Water, the type and amount of it, is the key to overwintering duck populations, migration patterns and waterfowl production. A survey in the late 1960's revealed that Nebraska had more than 523,000 acres of quality wetlands and other permanent water that could be utilized by waterfowl. NEBRASKAland

The Rainwater Basin covers some 4,200 square miles of flat to gently rolling loess plains. Over thousands of years, fine clay leached into low-lying areas, forming an impermeable "pan" that slowed water from seeping into the subsoil. The resulting wetlands and aquatic plant communities attracted ducks and other waterbirds long before white men knew of North America.

When the Rainwater Basin was initially surveyed, nearly 4,000 permanent wetlands were recorded. NOVEMBER 1976 By the late 1960's, only 18 percent remained, and of those, most had been adversely altered by drainage or siltation. Additional, unmeasured wetland destruction has occurred since 1970.

In 1960, a year of good water, when the first aerial survey of breeding ducks was made in the Rainwater Basin, over 38,000 birds were reported. During the spring of 1975, 14,385 birds were estimated when flying the same routes. Admittedly, only a part of the decline in breeding ducks can be attributed to loss of wetland habitat. However, less nesting habitat means lower duck prodution in wet years as well as dry.

29

Less obvious than the loss of potential breeding adults is the loss of production. While the number of breeders may remain about the same, their success in nesting and rearing broods declines as more birds are forced into less habitat. Crowding leads to nest abandonment, higher brood mortality, more predation losses and an increased incidence of disease.

In just the last decade, the composition of ducks nesting in the Rainwater Basin has changed. Redheads, scaup and pintails require large marshes for successful reproduction. Eighty to 90 percent of the broods produced in the basin are blue-winged teal, mallards, shovelers and gadwall. In 1975, fewer than one percent of the breeding ducks counted were redheads, and there were not enough diving ducks of other species to be calculated.

NEBRASKAlandThe Sandhills region is Nebraska's second major wetland area. Even though it encompasses some 20,000 square miles, lakes and potholes are clustered, and much of the Sandhills is devoid of waterfowl habitat. Over 13,000 wetlands, ranging from permanent lakes to seasonally flooded meadows, occur in low valleys of the grass-covered dunes. Most Sandhills wetlands are small, often under 10 acres.

Because the Sandhills is ranching country, its wetlands have been tampered with less than those of the Rainwater Basin. Over 80 percent of those originally surveyed still remain, but their destiny is far from secure. A falling water table has followed the proliferation of center-pivot irrigation systems. To date, the effect of declining ground water has been minimal but the writing is on the wall if current trends in agriculture continue. Drawdown of a marsh can NOVEMBER 1976 have as detrimental an effect as total drainage. Desirable duck nesting and brooding habitat is lost when the fringe of aquatic vegetation surrounding a marsh is separated from the water by a ring of mudflat.

Spring surveys indicate a decline in the number of breeding ducks in the Sandhills, too. During the late 1950's and early 1960's, estimates ranged between 99,000 and 176,000 annually. Since 1972, estimates have fallen between 62,000 and 91,000. As in the Rainwater Basin, many factors, in addition to habitat loss, are at work. The last three years have been drought years for the Sandhills; water and breeding ducks have understandably been in short supply. But even in the wet years of 1972 and 1973, fewer ducks were present during May than during the driest years in the late 1950's.

As in the Rainwater Basin, blue-winged teal, mallards, gadwall and shovelers are the most common nesters. The Sandhills' deep-water lakes still support some nesting divers. Redhead and canvasback are the primary species, accounting for something less than 5 percent of the annual production. Some years, ruddy ducks occur in significant numbers, occasionally making up as much as 12 percent of the spring "breeding duck" count.

Water availability is just as critical to migrating ducks as it is to nesting ducks. Rainwater Basin hunters know all too well that marshes covered with cracked mud do not attract or hold ducks in the fall. The success of a duck season can hinge on the amount of snow cover the preceding winter and rainfall during spring and summer. Ice-up time can also determine if Basin and Sandhill hunters have any shooting when the big flights of mallards come.

Strangely enough, the success that Nebraska duck hunters have in the fall has very little to do with nesting success in the state's marshes the preceding spring. An insignificant percentage of ducks taken by Nebraska hunters are produced locally. Most Nebraska-reared ducks are shot by hunters to the south. Even more surprising is band return information, indicating that most Nebraska bluewings shot during hunting season are taken in southwest Minnesota and southeastern South Dakota. Apparently, most local bluewings fly northeast once they reach flight stage, and later migrate south with the approach of winter.

Even though most Nebraska-grown ducks are shot elsewhere, our harvest is made up of largely the same species. Mallard and blue-winged teal are most frequently taken. Greenwings, gadwalls, pintails and wigeons account for most of the remaining duck harvest. To a large extent, the composition of the harvest is a reflection of species abundance in the Central Flyway. The number of diving ducks shot by Nebraskans is generally small and localized around reservoirs and along the Missouri River.

To a certain extent, duck harvest corresponds to migration patterns, or build-up in the case of over-wintering

birds. Duck migration has two peaks in Nebraska, one in

October and the other in November. Traditionally, hunters

have their best success the opening two weekends, well

into the first migration period under most season's regulations. Hunter interest wanes after that and the

31

As a rule, hunters in the Sandhills and Rainwater Basin have their best success during early to mid October. The push of November ducks, mostly mallards, is enjoyed by a smaller number of river hunters. Late season mallard shooting along the Platte River is often outstanding but is utilized by a small percentage of the state's waterfowl hunters, primarily due to limited access. During any given year, hunting success depends on weather patterns that trigger migration and affect its progression, and on the availability of open water.

But waterfowl in general and ducks, in particular are more than "breeding index" figures, harvest records or subjects for taxonomic classification. They are capable of arousing man's deepest emotions, be he a hunter waiting to decoy mallards in the fall or an observer behind a pair of binoculars. Unfortunately, emotions do not lend themselves to statistical summaries or computer readouts, and cannot compete with economics for analysis. Ironically, this may be waterfowls' undoing; tor when the value of a marsh is weighed against a cornfield or hay meadow, they always lose. Ω

32 NEBRASKAland

Waterfowl -Mortality- How They Die

EACH DAY DUCKS and geese die of diseases and from accidents. Unless mass die-offs occur, most waterfowl mortality goes unnoticed by man. Sick birds separate from the flock and seek concealment. As they become weaker, they crawl out of the water and hide in dense aquatic cover along the shoreline. The toll of disease is usually not visible because predators pick off the weak birds before they die, and scavengers quickly erase any sign of a dead bird within a few hours or days. When disease reaches epidemic proportions, birds die faster than predators and scavengers can clean them up. This is the point when we become aware and concerned.

Many natural and unnatural agents lead to waterfowl mortality. Predators have little effect on a healthy waterfowl population. Some eggs and young birds are lost to predators, but under normal conditions it is insignificant. A few accidents occur, such as hitting power lines, becoming entangled in fishing line or plastic six-pack holders, or swallowing pop-top tabs. Oil spills also account for the loss of some birds each year, but disease is by far the most important non-hunting mortality.

Band recovery data indicates that about 50 percent of all ducks die each year. During the past 20 years, the continental breeding population of ducks has averaged about 40 million. Assuming these 40 million ducks produce 40 million young, we should go into the fall hunting season with about 80 million birds. The average yearly kill in the United States is about 10.7 million ducks. An additional 3.5 million are taken in Canada. Crippling loss is about 20 percent. Hunters therefore remove some 20 million ducks, which is about 50 percent of the number that die during the year. The other half, or 20 million, die from disease, predation and accidents.

Usually, diseases in wildlife are self limiting due to relatively small, widely scattered populations that have previously established natural immunity. It is when animals or birds are crowded and when other stress is involved that the chances of an outbreak are the greatest. Diseases of waterfowl that frequently reach epidemic proportions and kill thousands of birds are fowl cholera, lead poisoning, botulism and duck virus enteritis (DVE). In Nebraska we have had considerable 34

It is virtually impossible to eradicate wildlife diseases; the best we can hope to do is control them and minimize losses. A significant contributing factor in recent fowl cholera outbreaks in Nebraska has been stress from overcrowding, a situation resulting from the reduction of wetlands along traditional spring migration routes.

Lead poisoning is considered the greatest non-hunting source of mortality in North American waterfowl. Lead poisoning occurs when the birds swallow lead pellets while feeding on the bottoms of lakes and marshes. As the shot pellet comes to rest in the gizzard of the bird, the surface of the pellet is eroded and dissolved away through grinding action of the gizzard and chemical action of the digestive juices. The lead then undergoes further chemical change as it moves through the intestine. Some of the lead compounds are then absorbed by the bloodstream through the intestinal walls, and apparently damage the liver and kidneys. The lead also appears to have a direct harmful effect on the muscles of the digestive tract. Usually, ducks dying from lead poisoning are very thin and have a green-stained vent. A bird may weigh only one-half of its normal amount before it dies.

The number of birds using an area, the amount of shot present, the availability of shot to feeding birds, the characteristic feeding habits of the birds and the type and amount of feed available are all factors that influence the occurrence of lead poisoning outbreaks.

Experiments have clearly shown that lead is highly toxic to waterfowl. A single ingested shot pellet is likely to have a harmful effect on a bird and may cause its death. It has also been demonstrated that as the number of shot pellets ingested increases, so does the mortality rate.

In one recent study, 36,145 waterfowl gizzards from numerous areas in the United States were inspected. The gizzards were taken from birds shot during the open season. Lead shot was NEBRASKAland found in 6.7 percent of all duck gizzards; 6.8 percent in mallards and a somewhat higher percentage in bay diving ducks. It was also found that 65 percent of those containing shot held one pellet, 15 percent two pellets, and only 7 percent had more than six pellets. On the basis of this study, it was conservatively concluded that 2 to 3 percent of the fall and winter waterfowl population, or 1.5 to 2.5 million birds, die from lead poisoning each year.

Do we have a lead poisoning problem in Nebraska? The answer to this is yes and no. Some of the basins, marshes and smaller ponds are real "hot spots" for lead poisoning, but such areas as the Platte River with its shifting, sandy bottom are not a problem. It has been estimated that as much as 1,000 pounds of shot is deposited by hunters on an opening day in one public waterfowl-hunting marsh in South-central Nebraska. The availability of shot for birds to ingest in such an area would be quite high.

We can expect the restriction of lead shot on some of these areas in the near future. The use of steel shot will be required in the fall of 1978 in some problem areas.

Botulism is another major mortality factor among waterfowl in North America. The greatest mortality from this disease occurs in the western states and Canadian provinces. Nebraska has experienced periodic waterfowl mortality due to botulism, but losses are usually not high due to small concentrations of birds during the summer when the disease occurs. Botulism is a bacterial poisoning resulting from the ingestion of a potent toxin that is produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum. It is a toxic, not an infectious, process since the bacterium doesn't invade the living tissues of the victim.

Duck virus enteritis (DVE) is an acute, contagious disease of ducks, geese and swans. DVE is caused by a virus that belongs to the same group of viruses responsible for herpes or cold sores, in man. The first major outbreak of the disease in a wild population occurred at Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge in South Dakota in January of 1973. Total mortality was estimated at over 40,000 ducks. As of yet, DVE has not been recorded in Nebraska. The virus is now present in the wild waterfowl population, and under the "right" conditions will probably NOVEMBER 1976 show up again.

The natural elements, such as unusual weather, can also result in significant waterfowl mortality. A severe late winter storm in Nebraska's south-central basins accounted for over 2,500 waterfowl deaths in 1976. On the night of March 11, the temperature dropped to near zero with winds of over 60 miles per hour. Ducks and geese caught on very shallow water were actually frozen in place before they had*a chance to escape. Many died on the spot, frozen in the ice. Those less fortunate were left alive but frozen in the shallow water. In an attempt to free themselves, many beat their wings on the ice until they bled. Mother nature is not always kind.

Most waterfowl mortality, especially diseases, can be directly traced to lack of habitat. As more and more habitat is destroyed, birds are forced to crowd into smaller areas. Crowding causes stress, and birds become more susceptible to diseases that formerly were of little significance. Once disease is introduced into a crowded, stressed flock, it sweeps through the population, claiming thousands.

In recent years, many of Nebraska's wetlands have been drained or destroyed. Where once there were hundreds of basins for nesting and migrating waterfowl, today, only a handful remain. When habitat declines, the number of animals depending on it must also decline. Disease is one of the vectors that crops waterfowl populations. It is nature's way of restoring a balance between wildlife and their habitat. In the final analysis, tomorrow's waterfowl are determined by the wetlands we preserve today. Ω

Return to the Platte

Each spring Canada geese and whitefronts push the season north, arriving on the Platte River in central Nebraska as early as mid February

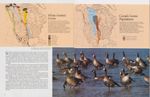

SANDHILL CRANES usher spring into the Platte Valley, but it is Canada and white-fronted geese that advance into winter's retreat. As early as mid February, small groups of Canadas have pushed their northward migration into Nebraska. Pioneering flocks of whitefronts are only a few days behind and by March, dark geese are common on the "big bend" of the Platte River and open-water marshes of the Rainwater Basin. Late-season blizzards may temporarily force them south, but when they peak during the third week of March, 120,000 to 160,000 whitefronts and twice as many Canada geese will be in south-central Nebraska.

Over 150 miles of frozen, shallow-water lakes between the Platte River and the Missouri River of South Dakota acts as a seasonal barrier to migrating geese, holding them back until spring has crept north of Nebraska's border. In the fall, we hardly see these whitefronts and only a few of the Canadas as they usually stopover in the Dakotas and then hop to wintering grounds on the Gulf Coast of Louisiana and east Texas, and into the interior of Mexico.

The Canada geese that gather in south-central Nebraska each spring are almost entirely of the "tall grass prairie populations," one of six populations that pass through our state. Each population has distinct nesting grounds, wintering areas, staging areas and migration patterns. Richardson's and giant Canada geese occur in this population but most are five to six-pound "lessers."

Traditionally, tall grass Canada geese overwintered on the Gulf Coast, but substantial numbers have been terminating their fall migration farther north in recent years. From two waterfowl refuges in Oklahoma, they advanced into southern Kansas, then northern Kansas and two years ago 5,000 to 18,000 remained on the Missouri River in South Dakota through the first week of January. Whitefronts seem to be following a similar trend, delaying their southward migration each year. Two years ago a small number stayed on the Platte into December.

38

During their stay in Nebraska, most geese concentrate in a triangle formed by Johnson Reservoir on the west, Holdrege on the south and Kearney on the east. Each year more Canadas and whitefronts are reported in Hall, Hamilton and Buffalo counties, indicating an eastward shift. Marshes in the Rainwater Basin, primarily those in Clay and Fillmore counties, draw thousands of birds after ice-out, especially during wet years.

Though greatly outnumbering the ubiquitous sandhill cranes that hop about grainfields in their courtship dance, or mill on thermal updrafts over the river, the geese are far less conspicuous. Like the cranes, whitefronts and Canadas pack into sandbar and shallow-water roosts on the Platte River each night after sundown. Shallow necks and mud flats provide roost sites on the rainwater basins.

As with the sandhill cranes, geese are fastidious when it comes to the choice of roosts. They require a broad channel with infrequent vegetation on the sandbars and channels. Even though they are more exposed to the season's rigors in open locations, they are less vulnerable to attack by predators or hunters in the fall.

Sections of the Platte River utilized by geese seem to have one common feature-relatively little alteration by man. Periodic high water is needed to scour the channels free of trees and willows. Reduction of water flow on the Platte River, due to irrigation drawdown or impoundment, could make it unsuitable for geese as well as other waterfowl.

Every day is different for the geese; weather changes, food sources are depleted, water levels vary and the birds' temperament changes as the season stirs them to continue migration. In general, though, the geese leave their night roost early, often before dawn, when just a hint of light is on the horizon. Some 40 birds are more eager to feed than others and string out to the grainfields before the mass of geese lifts above the haze of cotton woods that fringe the river. Until mid morning they'll pick through the snow-crushed corn and milo for fallen grain and emerging greenery.

Geese on the rainwater basins seem to move in more stable flocks than the river birds that trickle in irregular and loosely organized groups between the fields and water. During the late morning and into the afternoon, geese return to the Platte, most to loaf and preen, but some only to drink before returning to the fields. High winds, driving rain or snow may keep geese on the river later, in the fields longer or move them back to their roosts earlier.

By the fourth week in March, some geese begin to leave the Platte River and the Rainwater Basin. Just as they were first to arrive, Canada geese are the first to move north. Some whitefronts will also move early with the NEBRASKAland Canadas but they have a greater tendency to depart en masse. Often, half of the whitefronts will leave in one day and perhaps all except a few stragglers will follow them the next morning.

The mass movement of geese is impressive. Experienced observers say the geese are especially noisy, gabbling constantly the day before. They may go through their feed routine, but only out of habit. By evening, during the night or early the next morning, they will be gone. Occasionally they'll swing south as if going to feed, suddenly swing north, cross the Platte and chase spring into South Dakota and finally Canada.

Their stay in Nebraska was brief by most measures and caused little comment. Only a few noted the seasonal change that came with their passage. They're world travelers, and only tary awhile. Were they of our own kind, we would strain to hear the stories they tell, and greet them on their return to the Platte.

NOVEMBER 1976

Honker Homecoming

FEW sights touch the soul of the outdoor minded more than a grey Nebraska sky filled with fall flights of waterfowl. And, of all the kinds of birds in the air, none stirs more interest and excitement than the giant Canada goose.