NEBRASKAland

October 1976

NEBRASKAland

VOL. 54 / NO. 10 / OCTOBER 1976 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Sixty cents per copy. Subscription rates $5 for one year, $9 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKMand, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. commission Chairman: Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 Vice Chairman: Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-Central District, (308) 745-1694 2nd Vice Chairman: Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 William C. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-Central District, (308) 452-3800 H. B. "Tod" Kuntzelman, North Platte Southwest District, (308) 532-2982 Richard W. Nisley, Roca Southeast District, (402) 782-6850 Director: Eugene T. Mahoney Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, Jr. Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: Jon Farrar, Ken Bouc, 3ill McClurg Contributing Editors: Bob Grier, Faye Musil, Tim Hergenrader, Roland Hoffman, Bill Janssen, Butch Isom, Ben Schole Art Director: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Came and Parks Commission 1976. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska OCTOBER 1976 Contents FEATURES VIEWPOINTS OF A WATERFOWL HUNTER 10 PUZZLED OVER STRIPERS 12 CIRCLES AND CORNERS 14 NANCY AND THE U.S. MAIL 16 WILDLIFE HABITAT A Special 16-page section explaining the new concept in land acquisition and development 18 THE PHEASANT AND THE LAND 35 WASTE NOT, WANT NOT 36 ADVENTURES WITH WHISKERS The Color of Fall 42 DEPARTMENTS SPEAKUP 4 TRADING POST 49 BOOK SHELF 50 COVER: One of Autumn's most glorious and fascinating transitions is the change in color of foliage. While some leaves merely dry and fall, others, such as this grape leaf, exhibit their most impressive appearance. To see why leaves change, refer to "Whiskers" on page 42. Photo by Jon Farrar. OPPOSITE: One of nature's most perfectly designed creatures, the deer again thrives in Nebraska, these being mule deer from the western part of the state. Photo by Greg Beaumont. 3

Speak Up

Following is a poem sent to us by Vern Livingston of Nebraska City, with artwork done by his son. (Editor) The Homesteader's ShantySir / I want to thank you for sending me my first issue of NEBRASKAland last month. It was the July issue and I really enjoyed it. It has got to be the best magazine I have ever read.

What I liked about it was that all the features were enjoyable to read, not just one or two. I'm only 13, but I am the biggest outdoorsman in our family. Though I don't live in Nebraska, I live very close to the state line. With your magazine, I get a local view and plenty of good reading. Rick Kuckelman Seneca, Kansas

Thank you for your letter Rick. It's a pleasure hearing from a happy reader, and we hope our content continues to please you. I am sure you will be a sportsman of the very best type. (Editor) * * * Using the WindSir / Enclosed are a couple photos I thought you might be interested in. One is an old Windcharger which still stands about nine miles west of Imperial. Roy Hedges built a sevice station after World War I and repaired storage batteries. He built the tower from old car frames and wheels. The other is an odd shaped mill about 15 miles northwest of Imperial, with irrigation pipe used for the tower. L.P. Kramer Imperial, Nebraska

Sir / In reviewing your February issue, I was interested in the section dealing with farm ponds. I feel that this will be a valuable reference for all persons who own or manage a pond.

I would like to call your attention to the fact that CIBA-GEIGY Corporation has recently received a label from the EPA for Aquazine, an algicide. This is a selective chemical that controls nuisance algae and submerged weeds in ponds without harming the pond environment. Tests have shown that full-season control can be expected with only one or two applications. Aquazine is easily applied by the pond owner. Jack Lemon, sales rep. Roca, Nebraska

At the time that 'Ponds for Nebraskans' was written, the label for Aquazine had not been approved. Therefore, it was not listed in the section on vegetation control. Aquazine will be an asset to the pond owner in managing his private pond. Darrell Feit, Farm Pond Biologist * * * A Thought for FallSir / Here is a poem that might be of interest to some of your readers.

How beautiful a scene can be, a looking from above. With mountairis packed-in tight with snow, with trees and rocks and love. It covers all the littering, of cans and trash and things. But when the snow is gone, it will all be back next spring. God gave us this department, to use it as we wish, To hunt the game that grew on it, to trap and walk and fish. But he said "Don't take too many, but you can take a few Because the guy in back of you, he wants a couple, too. But men have gotten greedy, in the hunting and the fun, by Taking more than he can use, and that hurts everyone. But to sit and watch a bobber, a floating in the lake, God said, "You don't have to account for the time that that will take". So when we sportsmen are heading out to grab a fish or pheasant on the wing. Let us all remember one first law-let's not take everything. So as your boots get thinner, and your walk is getting slow, You hope that you can hitch a ride, or even get a tow. And as you hang your shotgun up, you can say within your mind, "I'm glad I left a few out there, for the guy who comes behind".Erwin Grabenstein Omaha, Nebr.

NEBRASKAlandHave We Got a Summer Planned for You This Winter!

there's hardly a place under the sun, come next winter, to which AAA World Wide Travel will not be escorting a group of fun—seeking Nebraskans. From Mexico to the South Pacific, from Hawaii to South America, the AAA banner of exciting tours will be carried. AAA travelers will be fishing in South America, ooohing and aaahing over the world's most spectacular train trip in Mexico, astounded by the mysteries of Mayan empires in Central America, awed by the lost civilizations that created Machu Picchu and the markings of the Plains of Nazca in Peru, lulled by the beauties of Hawaiian beaches or the luxury living of a cruise ship. You 've known AAA as a planner of the finest vacations by auto . . .nowtry us for your trips by air, sea and rail. You'll discover that we're the premier tour operators of Nebraska and the world, too. Fishing With Pete Czura— Your tour leader is Pete Czura, nationally acclaimed sportsman whose articles appear regularly in all the top fishing and hunting magazines. The tour is to El Dorado Lodge in Colombia. Pete acclaims this as one of the top fishing spots in the world. Late January departure. Wives welcome, too. Mayan Golden Triangle— a return of a very popular tour that includes Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula and its Mayan ruins, the new resort area of Cancun, and spectacular Guatemala, Febr. 2-16. Trans-Canal Cruise— The Panama Canal is one of the world's marvels. You 'II see how it operates on this luxury cruise aboard the world's finest ship, the Royal Viking Star, cruising from Los Angeles to Miami. Febr. 25-March 15. Easter Islands/Rio/Machu Picchu-A super tour escorted by NEBRASKA LIVING Editor Bare Wade in February. Includes an optional sidetrip to Macho Picchu. A fabulous itinerary. Windjammer Sailing Cruise— Another February departure with the lure of cruising the Caribbean on a real schooner. Disney World— Dec. 26-Jan. 2, a post-Christmas holiday for the family group to America's No. 1 attraction. This is a great one for parents and grandparents to treat the young ones (and yourself.) Malahini Hawaii— Our annual deluxe tour that is so popular it is nearly always a sell-out. 4 islands. Febr. 17-March 2. Mexico's Copper Canyon Rail Tour— imagine a 400-mile rail trip through one of the world's most spectacular canyons—burrowing through 87 tunnels, over 37 bridges. This is just one of the thrills of this tour, which includes visits to Guanajuato, San Miguel Allende, Guadalajara, Mazatlan, Chihuahua and Juarez-part by air, part by bedroom rail car, part by motorcoach. A real thriller. Febr. 12-28. Bill Christian's Hawaii Tour— Weii-known and popular Norfolk photographer Bill Christian leads an annual tour to Hawaii with the big emphasis on photography. Jan. 17-29. PLEASE SEND FOLDERS CHECKED BELOW: Fishing with Pete Czura Windjammer Cruise Mayan Golden Triangle DisneyWorld Trans-Canal Cruise Malahini Hawaii Mexico's Copper Canyon Rail Trip Easter Islands/Rio/Machu Picchu Bill Christian's Hawaii Tour

The Commonwealth now pays even higher interest rates!

6.25% Passbook Savings | 6.54% Annual Yield Comp. Daily 6.75% 1 yr. Cert. | 7.08% Annual Yield Comp. Daily 7.00% 2 Yr. Cert. | 7.35% Annual Yield Comp. Daily 7.25% 3 YR. Cert | 7.62% Annual Yield Comp. Daily 8.00% 4 Yr. Cert.8.45% Annual Yield Comp. Daily A substantial interest penalty, as required by law, will be imposed for early withdrawal.Pick of the NEBRASKA gift list...

SURPLUS CENTER

World Famous

Down Insulated Coat

CHRISTMAS CARDS of the Outdoor West

Fine Art 5"x7" Cards of Extraordinary Beauty

Christmas is that special time, once a year, to renew old friendships and share the season's joys. Our customers tell us there really is no substitute for Leanin' Tree Christmas cards. Warm and friendly greetings are perfectly matched to the full-color western scenes.

VIEWPOINTS OF A WATERFOWL HUNTER

EVERY SPORTSMAN has his preferences in the game he hunts. Mine, as many of my cohorts know, is waterfowl. I started hunting ducks and geese when I was only 12, and from that time on, I was hooked and waterfowl hunting became a part of my life. The first goose I shot was in 1938 when I was 16 years of age. I was hunting in north-central Nebraska near Cody when a small flock of snows and blues came over. I was alone at the time. I shot twice, and to my amazement, a goose fell out of the flock. It was not until 1946 that I again shot another one of those majestic birds. This time it was on the Missouri River, and from that time on, goose hunting had a No. 1 priority in my life.

Looking back, I realize that I've had some fine hunts and many unforgettable experiences. Probably the most memorable was on November 30, 1948. On that day, between 3,000 and 4,000 geese came downriver onto the very sandbar we were on. Geese were everywhere. The sound of those geese honking and beating their wings was something I'll never forget. Everyone shot geese that trip, but the thing that stood out most was the sight and sound of those majestic birds.

Another experience that I remember clearly was my first encounter with a white (albino) mallard back in November 1962. That experience happened on the Missouri River north of Bristow. The wind was blowing hard hitting somewhere between 40 and 50 miles per hour. Sand was blowing from the sandbars into our faces, making the day extremely miserable. Flights of ducks were constantly moving down river and occasionally decoying to our spread. One flight of approximately 60 mallards had a white bird in among them. I first thought the bird was a snow goose, but observing the flock closer, it was easily identified as a white mallard. The wind gusts drifted the flock to the right, but the birds flared back toward the decoys. When they crossed in front of the decoys, I connected. I was out of the blind in seconds and to my trophy.

Later, I found an article written in a newspaper by Bud Leavitt which indicated that biologists estimate the chances of a waterfowler bagging a white mallard as one in 20 million. Genetically, it is very unusual for a white mallard to be hatched. This past year, however, not only me but three other people were again fortunate enough to see an albino bird, a Canada goose, (Continued on page 47)

PUZZLED OVER STRIPERS

A relatively new fish in Nebraska promised to confound us. Our plan to follow locals to the action didn't quite work

I HAD PLANNED to fish Lake McConaughy for stripers for some time and was just waiting for the news to leak out that they were making their fall run, generally in October and November. When the news came, via the Lincoln Sunday paper, suddenly Les Spath and I were on our way west to invade Big Mac, the home of most of Nebraska's stripers. The 300-mile trip gave Les and me plenty of time to relive fishing trips of the past, and to plan our tactics for our upcoming encounter with the stripers that we knew nothing about. I have done quite well chasing other fish over the past 40 or more years, but striped bass were something new.

We had heard all kinds of stories about these fish; how they could rip 200 yards of line off your reel and snap 20-pound-test line with ease. Some fishermen even replace the standard hooks on their lures with extra heavy hooks to hold these monsters. The miles rolled by and we talked of these tales and made plans for catching this relatively new fish to Nebraska waters. I mentioned to Les that the wind could be a factor in locating stripers, as I had used it on many occasions to fish walleye and trout in the past, and it could be that stripers might follow the same patterns. But we agreed that "when in Rome do as the Romans", and so we would keep an eye on what the locals did. Yes, many questions would be answered this trip.

Our first information was bad, which was that the stripers hadn't been hitting the past week, but that before that they had really gone wild in the North Shore Lodge area and at Arthur Bay and Thies Bay 4 or 5 miles east of North Shore Lodge, where we decided to stay. When we arrived at North Shore, a couple of fishermen were weighing 3 stripers; an 11, 12 and a 14-pounder, and our hopes skyrocketed as we launched my 16-foot bass boat. Two o'clock that same day found us drifting among a convoy of 14 other boats off North Shore, convinced that at any moment a mighty striper would strike and the puzzle we had would start to be answered. But, after a couple of hours and no fish, we decided to make a run to Arthur and Thies bays. They were far from deserted, for we found 19 more boats. But, we joined the party and saw a 6-pound striper landed in the next hour and a half, and decided to go back to North Shore and finish the day. Things were just as we left them; lots of boats but no fish. We had heard that at times they would turn on just before dark, but not that evening, so at dark we called it a day. The next morning found us on the lake before sunrise. We were greeted with gray skies, mist, cold, and already the wind was kicking up a fuss, and we both knew our day's fishing would be cut short. Again, boats started to gather in front of North Shore, but still no one was catching any fish. The convoy grew to 15 or more boats and one lucky fisherman landed a 10-pound-plus striper before the wind kicked up the lake to a point where we were dipping water over our transom. Only three boats remained, so we gave it up around noon. The next morning was much more to our liking with clear skies and nearly calm seas. Things seemed ideal as other boats started arriving from all parts of the lake, but by 10 a.m. only one small striper and one small northern was the total score for these Romans, and I started to think maybe, just maybe, these Romans were from Spain. We decided that if a striper was caught in this bunch of boats our chance of being the lucky one was nearly nil, and that we would be better off looking for fish elsewhere, so we headed east. After motoring a half mile or so, we came to a small point that the wind was blowing straight into. "Old buddy," I said, "this might be the place. I've caught plenty of walleye and trout off just such points with this type wind. You know what I said about the wind being the best fish locater Mother Nature ever manufactured; well, she's telling me this place is worth a try."

I headed our rig into the wind and watched the depth finder until it reached the 50-foot mark, then cut the motor to start a drift back along this underwater point. The depth finder had just reached the 38-foot mark when something bombed my Big Jim lure, but I missed him and figured I had just blown my only chance of hooking and landing a striper and finding the answers to the many questions I had concerning this fish. Again I headed the boat into the wind for another drift down the point, and started to repeat the pattern that had given us our only ray of hope. As the depth finder neared the 35-foot reading, Les and I had our rods on the ready, and at 32 feet again it happened-a couple of hard, sharp hits and the 17-pound line was fast dissappearing from my reei and some of our questions were being answered. Yes, by golly, I had a striper on. "I don't know how big he is Les, but one thing's for sure, he's powerful."

As it turned cut, the striper was 16 pounds. We continued this same pattern for the next hour and a half and caught our limits in the 14 to 16-pound class, after having 3 lines broken and missing several other hits. This seemed to be a concentration of large fish, so later we guided a party of four people from the Lincoln area to our lonely hole, and their success was even better than ours; 8 stripers over 12 pounds, including an 18 and a 20-pounder in less than 2 hours after having been blanked for the two previous days. We came to the conclusion that a newcomer to Big Mac after stripers might like to know that when in Rome, do as the Romans do only as long as it pays off, then if it doesn't, make a change; any change will be better than to keep fishing an unproductive method. Try using the wind to find stripers, as they seem to build up on points or out from bays where the wind is moving the water. About 200 yards of a good grade 17 to 20-pound-test line will fill the bill for these battlers if you have your drag set properly. A good 4/0 hook for bait, and the standard hooks on most lures, will hold these fish if the fisherman will only take the time to completely play his fish and stay calm and not rush any part of landing this king of Nebraska's scrappers. One other reason many of these fish are lost due to broken lines is the angler's failure to cut his hook or lure off and retie it after each landed fish. Stripers will really put a strain on monofilament and the next good fish might cause it to break. The stripers seem to school according to NEBRASKAland size, and once a concentration of large fish is found, your chances are good of catching only adult fish. Many baits or lures will catch these fish: 6 to 10-inch chubs, Bajou Boogies, Bomber Slabs, and the Big Jim and Deep Jim are my choices. All baits and lures should be weighted to keep them near the bottom. But as in all fishing, keep an open mind and be ready to make changes. In some states they even catch stripers on top-water lures over 100 feet of water. October and early November have been the most productive months for taking stripers in the past. But, these fish must and do feed the year around and are OCTOBER 1976 catchable nearly all year if the pieces of the striper puzzle are all put together properly. As a table fish, I can't rate them with walleye or bass, but they are excellent smoked and baked if you cut all the red meat away from their sides. The Nebrska striper record held at 15V2 pounds until July of 1975 and was broken regularly until that October when the present record, a 25-pound, 1-ouncer was caught. But as they say, records are made to be broken, so if you're looking for a real tussle, try Big Mac; I know that what you're looking for is there, and maybe you'll meet. It happened to me, and it was great. Ω

13

CIRCLES AND CORNERS

Unwatered areas missed by center pivots can be boon to many species

Center-pivot irrigation systems have virtually sprung up across the state, not only replacing former equipment, but expanding the total acreage under irrigation in Nebraska to a phenomenal extent.

Not only has the influx put a tremendous strain on the groundwater reserves, but the amount of land change has brought concern from environmentalists and others that wildlife was going to be even more stressed by loss of habitat.

As with any innovation, there are advantages and drawbacks, but an optimist must always look to the good. Developing plantings in the corners of fields not included in the circuit of the pivoting sprinklers is certainly commendable.

Actually, if they go to weeds or are planted to more permanent cover, corners can be of tremendous value to wildlife. More habitat would be available than if there were no center-pivot system. Here, then, is an example of planting done on one extensive irrigation project in northeast Nebraska. Much of the impetus for this planting, which was done on a farm managed by Alfred Straka, was provided by Bob Hill, O'Neill Soil Conservation office.

34SWISH . . . SWISH . . . SWISH. . . . The long monster rolls over the land in a continuous circle, forming two-foot-wide trenches through the corn fields; on and on it goes . . . spraying out man-devised moisture to thirsty crops.

Almost daily, a center pivot irrigation system is established in Nebraska. And the only areas not receiving computerized water from the system are the corners. As the land, once idle or under dryland farming, is converted to' sprinkler irrigation the questions abound:

'What to do with the corners?" "Does the farmer put in alfalfa, wheat or grass?" "What about establishing livestock-protection tree plantings?"

State Biologist Robert O. Koerner, with the U.S. Soil Conservation Service (SCS), suggests: 'Why not put them (the corners) to good use and in the meantime realize secondary wildlife benefits?"

Each center pivot system corner has approximately 6.3 acres, equaling 24 to 28 acres per quarter or 96 to 112 acres per section.

Latest reports from the University of Nebraska's Conservation and Survey Division places the total number of quarter systems in the state near 9,000. This equates out to over 216,000 potential acres, and possibly half this amount might be devoted to a dual purpose of livestock protection and wildlife habitat development.

Wildlife populations need food, cover and water in the proper proportions for maximum reproduction and survival. An increase in wildlife habitat will also increase the carrying capacity.

Center pivot corners could provide all of these needed ingredients.

Koerner relates that a farmer once told him, when he first started working for the Soil Conservation Service over 20 years ago,*"I like wildlife. If you can tell me how to make a good living from the land and still have a place for wildlife I would be all for it."

In these times of dwindling wildlife habitat, it becomes more challenging all the time to do this, according to the SCS state biologist.

"Some of the best pheasant hunting in Nebraska could be provided in irrigated areas if nesting and winter food and cover could be developed," he believes.

The whole idea of using center pivot corners really rests with the local landowner. They are the ones who have to make the commitment, Koerner maintains.

Alfred Straka of O'Neill is one individual who started down this road in 1967 on his 20 quarters of center pivot irrigated land. His conservation goals include a long-range effort to plant trees in almost every corner. "The trees serve a multiple use for our livestock, feedlots and buildings, besides food and cover for wildlife," Straka said.

Adding, "I can certainly recommend this practice to others, and feel its a shame we didn't get something going 20 years ago." Since 1967 he has planted about 72,000 trees, using an SCS windbreak-wildlife conservation plan.

"Even though the weather was quite bad last year, since 1967 we have noticed an increase in pheasants and quail with a few more deer coming into the area.

"Prior to that, this land, which consists mostly of prairie, had only prairie chickens and grouse," he said.

Land use management in the Sandhills tries to achieve a workable balance between economics and conservation of natural resources in- cluding wildlife. Straka pointed out: "It's a way of life here, and I find it disappointing that we don't have as much wildlife as we did when I was growing up."

Selected areas, such as Straka's, can be improved for wildlife habitat enlargement by planting a nesting crop, i.e. alfalfa, clovers and/or a mixture of grasses and legumes.

In Nebraska, mowing should be delayed or controlled until July 15 to provide nesting cover. The areas can also be planted to wildlife shrubs and /or low-growing trees such as redcedar, Autumn olive or Russian olive for food and escape cover, in addition to taller trees for windbreak protection.

Game and Parks Commission and SCS biologists also recommend for corners adjoining road intersections, that plantings be placed at least 50 feet diagonally from the centerline where the two roads cross. This will avoid creating blind corners for motorists. One alternative would be establishing grass and legumes on these sites.

Diversity in cover types is the preference of wildlife. Landowners are advised to stick to low-growing shrubs such as Amur honeysuckle, American plum, skunkbush sumac, etc; intermediate trees such as chokecherry, Autumn olive; or go all redcedar.

"Tree and shrub plantings will usually be planted in rows. For either grass-herbaceous cover or woody plantings, your local Soil Conservation Service office can assist you with design, layout and adapted seed mixtures and species of woody plants that are best adapted to the respective locality," Koerner said.

The concept used on Fountain Farm has been termed "Farming with Wildlife," and apparently works as a covey of Hungarian partridge voluntarily moved into one of the windbreaks last year. Certainly a good sign. Ω

15

Nancy and the US. Mail

She knew the land, and the people, from many years of calling in dry or mud, heat and cold

SHE WORE OUT 11 cars and could find her way, blindfolded, over a hundred miles of twisting, rolling countryside, but when she applied for her operator's license renewal one spring, she was politely but firmly restricted to driving within the city limits of Broken Bow, Nebraska.

"Imagine that!" said petite, twinkly-eyed Nancy Buckner. What, she questioned, were 20-20 vision and instant reflex action compared to 90 years of learning the country by heart? She could tell those over-protective young whipper snappers of the State Department of Motor Vehicles, (and women's lib for that matter) a thing or two.

Nancy was a rural mail carrier out of Oconto, south of Broken Bow in central Nebraska, at the close of World War I, when female postal carriers were a rarity. In the beginning she hauled mail over a dirt road on a roller-coaster route that the devil himself must have laid out.

Any midwestemer can tell you that Nebraska in the spring, when redbud trees and wild plum take your breath away, and mourning dove and meadowlark are in good voice, is a little bit of heaven.

Nancy can tell you that a mail route across cattle grazing country, such as she traveled for 30 rugged years, can be a whole lot of hell.

"It was mighty slow, rough going on those steep hills," Nancy recalled. "In bad weather, the Model "T" would slide off the road and I'd have to call on one of the ranchers to get me back again. When the road was slippery or 16 icy it was doubly difficult with a team of horses."

From 1918 to 1948, neither snow, nor rain, nor heat nor gloom of night stayed this tiny, delicate 98-pound courier from her appointed ups and downs.

When Nancy started her postal career, her route consisted of a mere 28.8 miles. A few years later, when part of two routes was paved and one of the "mail" chauvinists chickened out, Nancy took over his route. She continued with this 51-mile run until she retired at 63 and moved into a neat white cottage in Broken Bow in Custer County.

In those early times, there was no such thing as ending a mail route at noon. It took skill and determination to traverse those hills, gullies and winding curves with team and buggy or Model "T". It took ingenuity and fortitude learning to change flat tires, patch inner tubes and pump up tires.

It also required time and patience to share neighborly news and gossip with lonely, isolated ranch wives eagerly awaiting her arrival.

Nancy traversed, changed tires, and communicated with a smile as she served from 150 to 175 patrons.

During sleet or snowstorms, she seldom reached home before 9 p.m. to take over where that phenomenon of a bygone day, the hired girl, left off.

When Nancy's husband died in 1940, she was really on her own. But she had learned the discipline of service; honest labor wore a familiar face, and roaming her beloved countryside had become a sacred calling.

If Nancy, a dugout and sod house baby, frontier child and pioneer mail person was, in her own words, "skimped" on cultural advantages, she was an avid self-taught student of the poetry, motion and music of Nebraska's wildlife. And she found it memorable and sweet.

She would, if pressed, be unable to articulate anything resembling Willa Cather's graceful, polished prose: "Nothing in the world, not snow mountains or blue seas, is so beautiful in moonlight as soft, dry summer roads in farming country, roads where white dust falls back from slow wagon wheels."

But she would nod her head in fervent agreement and understanding.

However, she would not find herself at a loss for words to describe her passionate dislike for rattlesnakes, some eight feet in length, that frequently threatened her on her stop-and-go countryside journeys.

Or her equally passionate admiration for Nebraska's most popular, gaudy, exotic immigrant game bird, the male ring-necked pheasant.

She can tick off some of many species of Nebraska's birds that have NEBRASKAland

Her favorites though, are the Western meadowlark, Nebraska's official songmaster, and the mourning dove.

"They're so different," says Nancy. "The little lark is so joyful, ringing that bell-song you never forget. The doves," she adds, "break your heart with sad sounds but they're clever ham actors. If anyone comes too close to their flimsy, sloppily built nests with two pure white eggs inside, the parents put on a performance you wouldn't believe! They flop to the ground, flounce around like crazy and carry on as if their wings were broken. So the enemy chases them and forgets all about the babies."

If Nancy was "shorted" on formal education, as she insists, she made the most of her "time of the singing of birds when the voice of the turtle (dove) was heard in the land".

Is there a better way than Nancy's of "learning the country" and getting to OCTOBER 1976 know the neighbors?

Nancy's prairie-land education began the day she was born, March 21, 1885, in a primitive dugout 5 miles south of Oconto, to parents who came from West Virginia.

Until she married, she had never lived in a frame house. She and her sister grew up in their family-built sod house. "I know how to build a sod house," she said. And you believe her, as she adds, "And I could today-if I had to."

Sod houses, like arrowheads and buffalo chips, aren't exactly cluttering up the environment these days.

But Nancy's former sod home is still standing intact, its outside earth structure cemented over; its interior walls camouflaged with plastic paper; furnished with electricity, hot and cold water, even bathroom.

Nancy's old delivery cart, anything but chic and weighted with regional history instead of local mail, rests from its labors in the House of Yesterday at Hastings. But not Nancy.

If her eyes sparkled with indignation when the Motor Vehicles Department tried to take all the adventurous spirit from the golden years of a veteran rural mail carrier, they crinkle with delight and anticipation when her children and grandchildren come to visit.

They don't get away until they drive her over her old hell-on-wheels mail route for instant replay and memory refreshment.

She listens, smiling, to the awe and respect in the voice of her daughter, Mrs. Lucy Schomers of Omaha: "Mom! How did you ever survive the blizzards and muddy ruts on these steep, winding roads before they were paved!"

She likes to check on former patrons and get acquainted with new ranch families that have moved into the territory.

Nancy is snug and content in the confines of her comfortable little town house when Mother Nature throws her winter temper tantrums. Retirement years then seem endurable.

But let soft rains fall and new grass appear on the earth. Let redbud and plum blossom burst. Let birdsong be heard in the land and she must get back to the country she learned so well. Ω

17

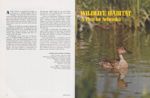

Wildlife Habitat

A Plan for Nebraska

A LONG CHAIN of events has brought us to this point—A Wildlife Habitat Plan for Nebraska. The Game and Parks Commissioners and their staff have been well aware for some time that favored wildlife species have been diminishing in numbers. What could be done? What factors caused the decline? IPs always easier to ask the questions than provide answers.

Reasons for declining wildlife populations are generally recognized. No single factor can really be blamed. It is also improbable that the Commission could do much to reverse the massive and complex changes that have occurred across the state.

Nonetheless, on a cold day in February 1975, a Wildlife Habitat Conference was assembled. From this broad-based group came recommendations to the Commission on ways to deal with the situation. From those recommendations evolved a proposed Wildlife Habitat Plan, which contained not only method but means. This plan resulted in introduction of LB861 in the 1976 Legislature by Senator Donald 18 Dworak. LB861 made its way successfully through the 1976 Legislature and was signed into law by Governor J. J. Exon.

What is accomplished through the Wildlife Habitat Plan will not be measured immediately, although achievements under various phases of the plan will become obvious soon. On the other hand, impact of some stated objectives of the plan will require at least a decade and may best be measured at the turn of the century.

The plan is achievable! The greater variables, which cannot be accurately forecasted, are what will happen in the coming years to the state and national economy in particular, and society in general.

Thus, the Commission, the director, and the staff of the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission invite the citizens of Nebraska to become a part of the considerable effort needed to bring meaning and benefit from this plan. This generation and those to come must have hope that wildlife resources of Nebraska will have a place in the sun and in their futures.

Nebraska Game and Parks Commission Arthur D. Brown, chairman, Omaha Kenneth W. Zimmerman, vice-chairman, Loup City Don O. Bridge, 2nd vice-chairman, Norfolk William G. Lindeken, Chadron Gerald R. Campbell, Ravenna H.B. Kuntzelman, North Platte Richard W. Nisley, Roca Eugene T. Mahoney, director William J. Bailey, Jr., assistant director Dale R. Bree, assistant director NEBRASKAland IT TAKES MONEY

IT TAKES MONEY

Wildlife is in trouble. Anyone who has hunted in Nebraska for any period of time has become increasingly aware of the obvious downward trend in wildlife populations. And, wildlife populations reflect the real problem—a serious decline in habitat. It's easy to spot the problem. The solutions are much more difficult.

In Nebraska, wildlife belongs to all the people, but the land that wild creatures need to survive is 97% in private ownership. What the farmer or rancher does with this land, as well as the caprices of Nature, have a tremendous effect on wildlife. During the peak of the Soil Bank, when 876,000 acres were retired, Nebraska experienced some of its highest wildlife populations. Conversely, with today's stress on farming every tillable inch, wildlife populations are declining.

No state program will be able to do what the Soil Bank did, but something must be done and soon. LB 861, passed by the 1976 Unicameral, will help. Through increases in permit fees and creation of a "Habitat Stamp," the bill provides new funding for a variety of programs designed to alleviate the critical habitat situation . . . things like retirement of marginal lands, acquisition, easements, and others. The plan, developed under provisions of the bill, is outlined in the following pages.

Under LB 861, those most vitally concerned with wildlife—the hunter and fisherman—have the opportunity to provide added support for creatures of the wild through their permit dollars. Some of the increases may seem high, but through the years, sportsmen of this nation have willingly shouldered the costs of wildlife management. They are again being called upon to support wildlife in these critical times.

Adequate habitat is essential to wildlife, and any program to restore habitat is expensive. The plan presented here is based on the additional $21/2 million that is estimated will be generated by the Habitat Stamp and the fee increases. LB 861 is only a start, but it IS a start. As the old proverb goes— the longest journey begins with but a single step. Nebraskans concerned about wildlife are facing a long journey, but they have also taken that first step. We have begun.

NEBRASKA'S PERMIT AND STAMP FEES (Effective January 1, 1977) HUNTING/TRAPPING RESIDENT NONRESIDENT Habitat Stamp $ 7.50 $7.50 Small Game* $ 6.50 $30.00 Deer* $15.00 $50.00 Antelope* $15.00 $50.00 Wild Turkey* $15.00 $35.00 Trapping* $7.00 $200.00** * Habitat Stamp required. **for first 7,000 furs, plus $10 for each additional 100 furs or part thereof. FISHING RESIDENT NONRESIDENT Statewide Annual $7.50 $30.00 Statewide 5-Day $15.00 Missouri River Annual $15.00 Missouri River 5-Day $5.00 Combination Fish-Hunt* $13.50 * Habitat Stamp requirecJ for hunting Where the Money Will GoAn estimated $21/2 million will be generated by the Habitat Stamp and increased fees authorized by LB861, projected on 1975 permit sales figures. Expenditures are based on recommendations evolved at the Nebraska Habitat Conference in February of 1975. Succeeding pages provide details on the various categories. Figures show the portion derived from the "Habitat Fund" or Habitat Stamp sales as well as other new income.

34% . . . $862,000 is earmarked for private land habitat development through the Natural Resource Districts on a cost-share basis. $500,000 will come from the Habitat Fund.

31% . . . $776,000 will go to acquisition of wildlife lands on a willing-seller basis. $500,000 will come from the Habitat Fund.

21%. . . $517,000 is allotted for management and development of Game and Parks Commission wildlife lands, as well as public lands controlled by other agencies. No Habitat Fund monies are allocated to this category.

14% . . . $345,000 is designated for wildlife habitat improvement through easements to preserve such things as streams and wetlands, farm pond habitat, trout stream check dams, and the like.

Private Lands...$862,000 (Habitat Fund...$500,000)

Private Lands...$862,000 (Habitat Fund...$500,000)

The private lands habitat program, as implemented through the Natural Resources Districts, will establish new habitat and improve existing wildlife habitat. This program focuses on production of habitat, rather than achieving access. The decision to allow hunting or not still rests with the landowner. An optional payment of $2.50 per acre for hunting access may be made, as an add-on to the practices described later, since it is not the purpose of this program to establish refuges or game reserves. Improved game production through improved wildlife habitat is the goal.

The Inter-Local Cooperation Act allows the Game and Parks Commission to participate with the NRD's. Under the Habitat Plan, base agreements will be made between the Commission and each NRD that wishes to be a part of this program. Then, a wildlife habitat plan for the district will be drawn up cooperatively between the Commission and each participating NRD. The NRD, in turn, will make agreements with individual landowners for habitat improvements. These improvements will be based on the established practices.

Cost-sharing for the private lands program will generally be 75% Commission and 25% NRD for habitat improvement practices. However, other percentages may be used where deemed practical. Assuming that funds from both sources would be fully available, $862,000 of Commission funds (75%) would match $287,000 of NRD funds (25%) for a total of $1,149,333 annually for wildlife habitat improvement on private lands.

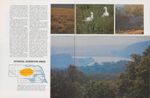

Half of the state funds ($431,000) will be allocated equally to all participating NRD's. The other half will be distributed on the basis of the habitat potential of each participating district, as well as the need. Existing habitat, as well as potential of various areas, has been calculated from inventories done for the Nebraska Fish and Wildlife Plan. Habitat is classed as high, moderate, low and scarce in determining evaluations. Funds not used by the districts may be re-allocated to other NRD's or for state projects.

Private Lands -- The Practices

Private Lands -- The Practices

Four habitat improvement practices will be eligible for cost-sharing under the private lands portion of the Habitat Plan. Specifically these include: (1) permanent cover on marginal lands, (2) enhancement of habitat on wetlands and odd areas, (3) rotation practices for wildlife habitat (sweet clover-oats), and (4) special practices, which allows for those items not common to all NRD's, such as grass-legume seeding on selected areas along country roads where of particular value.

Since federal programs follow the "practice-oriented" framework, this concept was adopted for the private lands portion of the Habitat Plan, as a readily understood approach to implementation.

Terms of each practice will be spelled out to include minimum and maximum on acreages, years of agreement, payment rate, cover type and seeding rates, and limitations. Depending on the practice, acreages may range from a minimum of 3 acres to a maximum of 80 acres per farm per year. Depending on the practice and land type, payments may range from $5 to $30 per acre a year. Contracts may vary from 3 to 10 years, again based on the type of practices.

Several things have occurred and continue to occur in land use and management in the states that are anything but favorable to wildlife habitat and thus wildlife. Among them are clearing of forest and riparian woodlands for crops, housing, and other uses; removal of hedgerows and shelterbelts, primarily for agricultural purposes; the drainage or filling of wetlands for agricultural purposes; and the movement of marginal lands into crop production. All these actions remove habitat and have reduced wildlife populations. Unfortunately, the trend continues unabated. Therefore, it is essential that certain key land and water tracts be acquired for preservation and management as wildlife areas.

Although primary public use would be for fishing and/ or hunting, numerous other desirable public uses can and do occur. Hiking, bird watching, outdoor education, and just "wandering" have special value, especially to the urban dweller.

Two major reasons for opposition to the acquisiton of private lands for these wildlife purposes were eliminated by LB 861. All private land acquired for wildlife management purposes by the Commission after January 1, 1977, will require a payment in lieu of taxes annually to the appropriate taxing entity. Secondly, LB 861 explicitly prohibits the use of eminent domain or condemnation powers in acquiring any land and water areas with funds derived from the bill. All land must be acquired on a willing-seller basis.

The Commission has placed its highest priority for acquisition on the rainwater basins of south-central Nebraska. Certainly wetlands located throughout the state need to be preserved also, since migratory waterfowl find these areas vital to their annual migrations. Disease problems related to the ever-diminishing wetlands have been severe in Nebraska the last two years. Total disappearence of central Nebraska wetlands would pose a threat to waterfowl populations that is not pleasant to contemplate.

Other land and water types of high priority are riparian land and water areas (rivers and streams and their associated woody habitat). These types of areas will also serve to provide fishing access to the many miles of rivers and streams in the state. Also of high priority would be lands that have potential as excellent upland game habitat.

The acquisition program would focus on Classes IV through VIII land types, thus leaving Classes I through III for their highest and best use, namely croplands.

Any meaningful measure of the impact of an action program such as that conceived in the Habitat Plan must consider at least 10 years of expected accomplishment.

The acquisition portion of this program would involve approximately 1,700 acres per year or 17,000 acres of land and water over 10 years. Costs are averaged at $450 per acre. The focus will be on Class IV through VIM land types, which are on the lower end of the pricing spectrum.

Nebraska encompasses approximately 50,000,000 acres. Since additional land cannot be "created," it may well be that land for wildlife may not be affordable by the turn of the century. Therefore, what we do in the next 23 years could be of incalculable value not only to current Nebraskans, but for generations upon generations to come.

Acquisitions will lean heavily to land and water areas that fall into a "complex" or unit-management system. It is best to have land and water tracts located in reasonable proximity to each other to use Commission personnel and resources efficiently and to better serve the hunting and fishing public.

Thus, wetlands acquired in the Holdrege-Hastings-Clay Center area, when added to existing wetlands already owned in this general vicinity, can be efficiently managed by a single crew.

Another benefit of the management unit concept is the potential for multiple use. A broad range of public use opportunities exists in the Nemaha and Blue River basins of southeast Nebraska if a good mix of river access sites, small lakes/land areas, and upland game sites can be acquired and added to the Commission's holdings. Where public pressures are great, as they are in southeast Nebraska, it is best to plan for dispersal of use over a number of areas. The only other feasible means of satisfying these users would be with one large land and water area, which seems highly unlikely to be developed.

To establish a wildlife acquisition plan of meaning and value, many factors must be incorporated. For example, it is obvious that the population is heavily concentrated in eastern Nebraska. It follows, then, that fish and wildlife resource users are also concentrated in eastern Nebraska. This plan attempts to deal with the need thus created, at least in part. At the same time, it is essential to serve all Nebraskans and areas of need, even though they are low in population density.

In overview, however, fishing and hunting are games of opportunity. When and where good fishing and hunting opportunity can be established, the users will find their way to it.

Unfortunately, costs do not cease once lands are acquired, but expenditures are relatively low to meet the needs on wildlife lands. The greatest single benefit is achieved at acquisition—the land and water is withdrawn from the market. It is held for public use in perpetuity. Beyond this high purpose are the more ordinary needs—fencing to define the boundaries and keep out livestock, a modest access road or trail to allow public entry, provisions for parking, in some instances sanitary facilities, habitat development and improvement, and last, but not always least, control of noxious weeds (primarily musk and Canada thistle).

Public Lands - Management...$517,000 (Habitat Fund.......$0)

Public Lands - Management...$517,000 (Habitat Fund.......$0)

For purposes of this plan and for current and future budgeting, public lands are divided into two general categories—Nebraska Game and Parks Commission wildlife lands and other public lands.

On Commission owned or controlled lands and on those to be acquired, the range of wildlife habitat management options is greater than on other public lands. On Commission lands, habitat management will be intensified to be more productive of fish and wildlife. Although the ingredients may be different, intensified habitat management and intensified agricultural management are similar in many aspects. Certainly, increased yields are expected from each.

Interspersion is a basic concept of wildlife habitat management, and means diversity or variety of plants. A good balance of highly productive wildlife habitat (for most upland game, small game and deer) will have permanent woody cover of various sizes, a good mix of durable grasses and legumes, with small amounts of crop plants such as milo or corn. Some newly acquired areas may be nearly devoid of any plants. Other lands may be suffering from "mono" or single-plant type growth or cover.

Needed items become obvious-seed (clover, other legumes, grasses, crops); trees and shrubs; selected chemicals; equipment; vehicles; contracts; and a modest level of capital development for access roads, trails and parking.

On other public lands, habitat development options are not as wide ranging. All public land is dedicated or held in reserve for some primary purpose. Only after the primary purpose is served and other requirements met, is it possible to achieve improved habitat for wildlife.

Habitat improvement and protection activities that can be attained on these other public lands, without damage to primary and selected purposes, include: (1) fencing out of woody draws and shrub and tree sites; (2) protection of riparian habitat by fencing, while still allowing for grazing and stock water needs; and (3) wildlife water-source development or improvement.

State and federal public lands with the most potential for habitat development are those administered by the U.S. Corps of Engineers, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, U.S. Forest Service, and some lands owned by the State.

Considerable potential for fish and wildlife habitat development exists on land and water areas that might result from future water-development projects. Nebraska already has numerous water-development projects, large and small, that serve their primary purpose (flood control, irrigation, etc.) yet are of tremendous value to fish and wildlife interests as secondary beneficiaries.

Aside from the controversy that tends to surround any large water-development project today, once the public, through the appropriate legislative and judicial processes, decides to acquire land and develop water-retention reservoirs, it behooves the Commission to be involved in the planning process. The Commission then should perhaps even develop and manage the resulting land and water resource for fish and wildlife.

While wildlife is the prime beneficiary of all of these management efforts, the ultimate purpose benefits man in a variety of ways. Obviously, hunters and fishermen will gain, but so will other users such as hikers, boaters, bird watchers and others who simply enjoy communing with Nature.

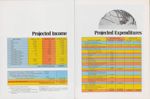

Projected Income

Type of Permit Number in 1975 Increased in Rate Increased Income

Hunt 89,942* 2.00 $ 179,884

Hunt & Fish 59,981 * 5.50 329,896

Fish 167,017 2.50 417,542

Turkey 3,886* 10.00 38,860

Trap 6,331* 3.50 22,158

Furbuyer 128 40.00 5,120

Nonresident Trap est. 10* 100.00 1,000

Nonresident Furbuyer 13 200.00 2,600

Nonresident Deer 426* 15.00 6,390

Nonresident Antelope 0*

Nonresident Fish

Nonresident Annual 10,882 15.00 163,230

Nonresident 5-day 24,522 10 00 245,220

Nonresident Turkey 0*

Nonresident Hunt 14,934* 5.00 74,670

Total for Permit Fee Increases $1,486,570

Total permits that require a Habitat Stamp 175,510

Adjusted for stamp holders with more than one permit** 153,664

Add Habitat Stamps for Resident Deer and Antelope hunter who have no other permit*** 3,829

Total number of Habitat Stamps157,493 @ $7.50 | $1,181,1981

Sub Total | $2,667,768

Less $1 for 1975 Upland Stamps - 150,757

Total generated new funds | $2,517,011tt

* Those that require Habitat Stamps + The Habitat Fund

** Includes all resident hunt, hunt and fish; ++ The budget request for 1977-78 is presently scheduling

1/2 of resident turkey and nonresident turkey,deer $2,500,000.00 for expansion above the continuation

and antelope; 1A of resident trapper level of habitat improvement activities.

*** Estimated at 1 /10th of all resident deer and antelope permittees

Projected Expenditures

Type and area of expenditure Total LB 861 new funds Habitat Fund Only

Avg. Annual 10 yr. total Avg. Annual 10 yr. total

I Private Lands Habitat (NRD) Using practices described in plan $862,000 $8,620,000 $500,000 $5,000,000

II Wildlife Land Acquisition $776,000 $7,760,000 $500,000 $5,000,000 $5,000,000

III Wildlife Management on Public Lands

A. Commission Wildlife Lands

1. Seed—sweet clover, other legumes, crop seed, grasses $40,000

Trees & shrubs 40,000

Chemicals 3,000

2. Travel 9,000

3. Equipment 40,000

4. Operating cost 45,000

5. Personnel (new) 117,000

6. Payment in lieu of taxes on wildlife land acquired after Jan. 1,1977 19,000

7. Fencing, minimum access roads, and parking 36,000

Sub Total $349,000 $3,490,000

B. Other Public Lands

1. State school lands contracts with interested lessees to fence, plant & maintain habitat $18,000

2. Other state lands contracts to plant and fence habitat as feasible 40,000

3. Federal lands: Forest Service, Corps of Engineers, etc. Fence, plant & care for habitat 110,000

Sub Total $168,000 $1,680,000

IV Habitat Management Easement to preserve streams & wetland habitat, $345,000 $3,450,000

farm pond habitat & trout stream check dams.

TOTALS $2,500,000 $25,000,000 $1,000,000 $10,000,000

Projected Income

Type of Permit Number in 1975 Increased in Rate Increased Income

Hunt 89,942* 2.00 $ 179,884

Hunt & Fish 59,981 * 5.50 329,896

Fish 167,017 2.50 417,542

Turkey 3,886* 10.00 38,860

Trap 6,331* 3.50 22,158

Furbuyer 128 40.00 5,120

Nonresident Trap est. 10* 100.00 1,000

Nonresident Furbuyer 13 200.00 2,600

Nonresident Deer 426* 15.00 6,390

Nonresident Antelope 0*

Nonresident Fish

Nonresident Annual 10,882 15.00 163,230

Nonresident 5-day 24,522 10 00 245,220

Nonresident Turkey 0*

Nonresident Hunt 14,934* 5.00 74,670

Total for Permit Fee Increases $1,486,570

Total permits that require a Habitat Stamp 175,510

Adjusted for stamp holders with more than one permit** 153,664

Add Habitat Stamps for Resident Deer and Antelope hunter who have no other permit*** 3,829

Total number of Habitat Stamps157,493 @ $7.50 | $1,181,1981

Sub Total | $2,667,768

Less $1 for 1975 Upland Stamps - 150,757

Total generated new funds | $2,517,011tt

* Those that require Habitat Stamps + The Habitat Fund

** Includes all resident hunt, hunt and fish; ++ The budget request for 1977-78 is presently scheduling

1/2 of resident turkey and nonresident turkey,deer $2,500,000.00 for expansion above the continuation

and antelope; 1A of resident trapper level of habitat improvement activities.

*** Estimated at 1 /10th of all resident deer and antelope permittees

Projected Expenditures

Type and area of expenditure Total LB 861 new funds Habitat Fund Only

Avg. Annual 10 yr. total Avg. Annual 10 yr. total

I Private Lands Habitat (NRD) Using practices described in plan $862,000 $8,620,000 $500,000 $5,000,000

II Wildlife Land Acquisition $776,000 $7,760,000 $500,000 $5,000,000 $5,000,000

III Wildlife Management on Public Lands

A. Commission Wildlife Lands

1. Seed—sweet clover, other legumes, crop seed, grasses $40,000

Trees & shrubs 40,000

Chemicals 3,000

2. Travel 9,000

3. Equipment 40,000

4. Operating cost 45,000

5. Personnel (new) 117,000

6. Payment in lieu of taxes on wildlife land acquired after Jan. 1,1977 19,000

7. Fencing, minimum access roads, and parking 36,000

Sub Total $349,000 $3,490,000

B. Other Public Lands

1. State school lands contracts with interested lessees to fence, plant & maintain habitat $18,000

2. Other state lands contracts to plant and fence habitat as feasible 40,000

3. Federal lands: Forest Service, Corps of Engineers, etc. Fence, plant & care for habitat 110,000

Sub Total $168,000 $1,680,000

IV Habitat Management Easement to preserve streams & wetland habitat, $345,000 $3,450,000

farm pond habitat & trout stream check dams.

TOTALS $2,500,000 $25,000,000 $1,000,000 $10,000,000

The Pheasant and the Land

Ringnecks have had their ups and downs over the years, as land use changed. Over long run, however, trend is ever downward as intensive farming pushes them out

NEBRASKA'S most popular game bird, the ring-necked pheasant, is a relative newcomer here. Descended from immigrants just as are many of the state's human residents, pheasants are currently found everywhere in the state where suitable habitat exists.

Nebraska is typical of the midwestern states, which are the heart of the country's prime pheasant range. First occurrences of pheasants here were recorded from 1900 to 1904 when individual birds were reported shot at various points along the Kansas line in southeast Nebraska. These were probably stragglers from some early private importations.

Earliest stocking attempts by the state were made around 1915 with several dozen birds. During the next 10 years, small shipments were released by the game agency each fall. To some extent, state releases were supplemented by private individuals, particularly in central Nebraska. Thus, the high pheasant populations of the mid-40's and the Soil Bank era, as well as today's population of approximately 3 million birds, were derived from the introduction of less than 500 pairs.

Primarily a mixture of Chinese, Mongolian and bleckneck strains of the ring-necked pheasant, the birds' rapid increases demonstrated their tremendous potential to thrive where there is adequate habitat. The birds' adaptation to Nebraska's changeable climate and to the habitat associated with the grain culture of the plains was nearly perfect-almost too perfect, in fact. By the early 1920% corn damage from pheasants was being reported in central Nebraska.

By 1926, pheasants were so plentiful in Howard County that some 15,000 were winter-trapped and distributed in 49 other counties. A year later, about 30,000 birds were trapped in Howard, Sherman and Valley counties for distribution in 76 counties. That pheasants were abundant in the this area is borne out by the fact that the 1926 trapping removed an average of 27 birds per section in Howard County.

OCTOBER 1976The late 1930's and early 40's saw some of the most tremendous pheasant numbers that Nebraskans will ever know. The population trend from the mid 40's was generally downward, with some marked drops associated with the blizzards of 1948 and 1949. There was a brief resurgence in the first 3 years of the 50's. During the next 5 years the pheasent population declined in response to farming itensification and dropped to its lowest point in 1957.,Nebraska hunters felt the effects of the decline and harvested only about half a million cocks that year.

Pheasants didn't suffer alone in 1957. Agricultural crop prices were depressed, and millions of federal dollars were spent for grain storage. The solution to the problem—the Soil Bank—proved a boon to Nebraska pheasants.

The birds responded to this land retirement by more than doubling their population the first year of Soil Bank. Hunter success also improved in 1958, and sportsmen harvested approximately VA million birds. The Soil Bank program in Nebraska peaked in the early 60's with 876,000 acres out of crop production, less than 2 percent of the state's total land area. The pheasant population remained high during the early 1960's, when the program provided maximum cover. As retirement contracts expired and land was brought back into production, pheasant numbers responded to the habitat loss and began to decline.

The Cropland Adjustment Program (CAP) of 1966 was designed to replace the Soil Bank. However, this program was not of the same magnitude and didn't have as much impact on pheasant numbers. However, it did slow the decline during the 1960's and 70's.

Current trends in agriculture are toward maximum production and larger, more efficient equipment. The world market for crops is favorable, and exports are needed to offset the balance of trade. Agricultural technology has evolved rapidly. Ever larger fields are worked with mammoth, high-speed equipment. Grasslands are being converted to row crops. Fencerows, wetlands and other permanent cover are being removed. Fall plowing is being practiced.

In response to man's changes in the use of the land, pheasant numbers have declined each year. Since the destiny of the pheasant, as with so many other species of wildlife, is and has been inextricably tied to man's behavior, especially his use of the land, any realistic forecast for the next few years would have to call for even further declines.

No game bird in the state is as adaptable as the pheasant, nor does any other game species have the reproductive capability of the ringneck. Yet, this capability to exist under the changeable and often harsh climate of Nebraska cannot ever be fully realized without the ecological requisites for survival. The pheasant, like any other living creature, is completely dependent on suitable habitat. The pheasant's relatively short history in Nebraska has illustrated that even a small percentage of permanent cover means a great deal. Soil Bank booms have come and gone, and the pheasant has fluctuated with these increases and decreases in permanent cover. Pheasant numbers have dropped wherever intensive irrigated farming has removed fencerows, drained and leveled rainwater basins, and narrowed roadsides.

From a game manager's perspective, every unit of land has a given "carrying capacity" or numbers of wildlife it will support. Where essentials like nesting and winter cover or winter foods are lacking, this capacity is diminished. Interspersion, or diversity of cover types, is a key to estimating productive capability of pheasent range.

At this juncture, the future of the ringneck in its former prime midwest range is not the brightest. But, optimism remains high for its future through management and the Habitat Program. Everyone must work together, though, to insure that our valuable wildlife heritage will be here for enjoyment by generations to come. Ω

35

Waste Not, Want Not

NOTHING lives forever. All living creatures eventually fall prey to stresses of disease, old age or injury. The whitetail buck dies, as all living creatures must, and its decaying flesh provides food for a myriad of organisms. Held in low esteem by many, these creatures occupy an extremely important role in life, for these are nature's refuse collectors and recyclers, the scavengers. Feeding on carrion, they take what they need until nothing is left but bone. In nature's scheme, nothing is wasted. Even bone will one day return its elements to the soil to be reused by plants and animals, and the cycle goes on.

Often maligned as a killer of wildlife and domestic stock, the coyote will eat almost anything, but its primary food consists of small animals such as rabbits and mice. Carrion makes up a large portion of the remainder of the diet which includes birds, insects, fish and some vegetation. An opportunist, the coyote will take advantage of an easy meal when he can get it. A road-killed deer is a prime potential food source for a hungry coyote and he won't turn up his nose. In fact, most deer and young livestock that coyotes are blamed for killing, die as a result of starvation or exposure. The scavenger coyote fulfills a major role as one of nature's recyclers.

36 NEBRASKAland

Unlike the coyote, which is omnivorous, the turkey vulture feeds almost exclusively on carrion. In areas where they are found, these large birds rely on keen eyesight and a sense of smell to locate their food. A highly efficient garbage disposal system, vultures will devour all remains of a dead animal, leaving only the skeleton. There is little they won't eat, as long as it is dead. Although many will often gather to feed at carcasses of large animals, they are not known to be gregarious birds and usually fly singly or in pairs. When carrion is sighted, though, they gather in flocks and wheel about until one alights, then others follow. On the ground, the turkey vulture is an ugly and clumsy creature. Hopping about, it can make little progress. In the air, this bird is transformed into a highly efficient flying machine. Long and wide wings allow the bird to remain aloft for hours, gliding effortlessly, riding the thermals.

Black-billed magpies, members of the crow family, are as diverse in their feeding habits as the coyote and perhaps even more so. These mischievous, noisy rascals prefer animal food, primarily insects when available. Magpies also eat carrion and are frequently seen along roadways feeding on road-killed animals, especially in the winter when they are reduced to eating vegetable matter such as plant seeds. During summer, they often appear to be feeding on carrion while in reality they are taking fly larvae from carcasses of dead animals to feed their young. In some areas of the west, they have been known to pick on open sores on the backs of livestock and also eat the exposed flesh, which occasionally leads to death of the animal.

OCTOBER 1976 39

A seldom seen scavenger, the mortician or burying beetle is a creature whose work is no less important in the decomposition process. Burying beetles are attracted by the odor of a dead animal, which must not be too large or small. While the beetles mainly utilize small rodent-sized animals, they also feed on scraps left by other scavengers. Usually several beetles will begin work on the carcass and will undermine the remains until it is completely below the surface of the ground. When the work is completed, the strongest female will normally drive off the other beetles. She continues to work on the remains until it is pushed into a circular-shaped mass of flesh. Then she lays her eggs near the remains to feed the half-dozen young, which hatch after five days.

40 NEBRASKAlandThe white-footed mouse is one of the most common mammals on the North American continent. This little rodent is omnivorous like the coyote and magpie. Although it prefers seeds and berries, it will eat many different insects as well as carcasses of small birds and animals. These and other rodents, spurred by some body deficiency, will periodically feed upon antlers and bone of dead animals. Biologists believe this is to offset a calcium and phosphorous deficiency prior to breeding. When bones aren't available, rodents turn to plant roots and stems which also have a high concentration of these nutrients. In time, the rest of the skeletal remains are again absorbed by the earth. In nature, it's waste not, want not.

Adventures With Whiskers the prairie vole

BOY, AFTER THAT episode with the bulldozer last month, I didn't know if I'd be here to meet you or not. It's just not safe for a little vole anymore with all those big machines rumbling and bumping around. I packed up what belongings I could find, loaded them in a coffee can some fisherman had left along the river, and floated downstream. It was quite an adventure. I felt like an old trapper taking my winter's catch of furs to St. Louis. It took me about three weeks just to get to Louisville— that's pretty close to where the Platte River runs into the Missouri River. It's pretty in the fall, the oak trees turn red and gold.

Leaves are pretty fascinating. But, even we voles get to taking them for granted. They come in just about every size and shape you can imagine. All the trees of one kind have pretty much the same shape. If you've seen one cottonwood leaf you've just about seen them all. Oops! There I go again, taking those amazing leaves for granted.

You know, they're actually like little factories. Each leaf captures sunlight, mixes it up with water and nutrients that the roots draw from the soil, and makes food for the tree. That's how they grow. Deciduous trees, those that drop their leaves each fall, have to make enough food during the summer to last through the winter. Trees sort of hibernate. A lot of mammals hibernate through the winter. They eat like mad all summer and accumulate thick layers of fat. Then, over the cold months they curl up in some warm, cozy place and sleep, living off their summer fat.

When I was younger, I always used to wonder why leaves turned such bright colors in the fall. Finally I asked my uncle Thaddeus. He's a professor at our university. They all call him Professor Thaddeus B. Vole.

He told me that what makes leaves green is something called chlorophyll. You find chlorophyll in whatever part of the plant is making food. That's generally the leaves. In the fall, when it gets too cold for leaves, they lose their green chlorophyll and turn whatever color is left behind. Red is left behind in a lot of trees, such as pin oak or red oak. Cottonwoods turn bright golden yellow, and bur oaks turn brown. Some trees, like the red maple and sugar maple, have both red and yellow colors left. They turn a mixture of red and yellow—orange. Sometimes they will even have a leaf with both red and yellow on it.

Uncle Thaddeus knows a whole lot about Dlants and animals. He said that you get the Dest fall colors around the time of the first frost. Down here at Louisville, that's about October 10. Up at Chadron, in Nebraska's northwest, its as early as the middle of September.

Maybe in January or February when I go on vacation, Uncle Thaddeus will meet you here. He's a little stuffy at first, but you'll get to like him. See you around. Ω

Get out ot this world. Less than $12.00

Ithacagun Whisper- Pak® ear protectors let you shoot in a comfortably silent world of your own. Where you can concentrate on your own shooting without the distracting noise of other shooters Whisper-Pak filters out the startling sharp high-frequency sounds and intense sound pressures created by gun-shots, reducing to 1/200th the potential harm to unprotected ears. Ear cups rotate 360°, pivot on vertical axis and swivel horizontally to conform comfortably in ail head positions. Whisper-Pak. At any Ithaca Gun direct dealer."Ringnecks"

Guaranteed Limited Edition Prints Now Available

Here is a full color reproduction offered in a guaranteed limited quantity of 1,000 by Neal R. Anderson, commissioned wildlife artist for NEBRASKAland magazine. Each print is 16 x 20", signed & numbered, with ample margins for matting and framing. $20.00 each. Excellent color reproduction and added realism is achieved by the canvas-embossed paper on which it is printed. All prints are shipped extremely well protected, postage paid. You must be totally satisfied or a full refund will be made. 40% dealer discount upon request. Please send me: Print(s) of "Ringnecks" @ $20.00 each. Nebraska residents add $.50 sales tax. Lincoln, Bellevue & Omaha, Ne. residents add $.70 sales tax. Name Address City State Zip Mail to: Neal R. Anderson 5420 Oldham Lincoln, Ne. 68506 STUHR MUSEUM of the Prairie Pioneer U.S. 281-34 Junction Grand Island, Nebraska 68801 44 NEBRASKAlandGrand Island, Nebraska 68801

U.S. 281-34 JunctionHUNTERS

Eat and/or stay overnight $15.75 per person per dayGUN BLUEING

T. W. MENCK, GUNSMITH 5703 So. 77, RALSTON, NB 5-8 Mon.-Fri., 9-1 Sat.Tullers Medicine Creek Lodge

Cafe • Air Conditioned Cabins • Boats • Motors • Gas • Oil • Bait • Fishing and Hunting Supplies • Fishing and Hunting Permits • Guide Service.YOU PAY

You pay 24c to send a 2-ounce letter. You pay no more than 20c plus tax to dial direct for the first minute outside Nebraska between 11:00 p.m. & 8:00 a.m. Sometimes it's cheaper to tell it than to write it. THE LINCOLN TELEPHONE CO.DEER PROCESSING

WE MAKE DEER SUMMER SAUSAGE JOHNSON LOCKERS 466-2777 Lincoln, NebraskaBICENTENNIAL MINT SET

THE HOTTEST MINT SET IN MINT HISTORY !

1977 NEBRASKAland Calendar

Browning

Our EXCLUSIVE DISCOUNT PLAN on all BROWNING products will save you up to 20%. This includes guns, ammunition, archery, clothing, boots, tents, gun cases, rifle scopes and fishing equipment. Inquire ... it will save you $$$. Big discounts on other sporting goods. OPEN 7 DAYS A WEEKHarlan County Reservoir HANK & AGG'S CABINS

Road No. 3 South of Dam Housekeeping and Sleeping Units Republican City, Nebraska Phone 308-799-2675 Fishermen and Hunters Welcome! Weekly and Daily RatesAUTHORS WANTED BY NEW YORK PUBLISHER

Leading book publisher seeks manuscripts of all types: fiction, non-fiction, poetry, scholarly and juvenile works, etc. New authors welcomed. For complete information, send for free booklet R-70. Vantage Press, 516 W. 34 St., New York 10001MUTCHIE'S Johson Lake RESORT

Upstairs Anchor Room Lounge Cold Beer-On/Off Sale Lakefront cabins with swimming beach Fishing tackle Boats & motors Free boat ramp Fishing Swimming Cafe and ice Boating & skiing Gas and oil 9-hole golf course just around the corner Live and frozen bait Pontoon, boat & motor rentals. WRITE FOR FREE BROCHURE or phone reservations 785-2298 Elwood, NebraskaGUN DOG TRAINING

All Sporting Breeds

VIEWPOINTS OF A WATERFOWL HUNTER

(Continued from page 11)along the Missouri River.

The Missouri River area has changed drastically since I began hunting back in 1946. At that time the river meandered at will, creating sandbars, shallow areas and new stream channels annually. The untamed river produced excellent resting and feeding areas for waterfowl, large numbers of spawning and feeding areas for fish, and a diversity of habitat types for deer and sharp-tailed grouse, ring-necked pheasants and cottontails.

The Missouri River today no longer is free to fluctuate as rainfall and snowfall dictate. It is now controlled through a series of dams constructed by the Corps of Engineers for navigation, water storage and flood protection.

The dams, although beneficial in some respects, have had adverse effects on wildlife numbers. Since the rivers no longer fluctuate, man has encroached onto the flood plain, clearing trees for farming purposes. This has resulted in a great deal of wildlife habitat being destroyed.

As the River flows were more centralized, the large sandbars were also lost. Some of these sandbars were up to three miles in length, providing excellent resting areas for all types of wildlife, but especially for waterfowl.

We used to lay our shotguns down during mid-day and just walk those bars and observe the wildlife present.

Gone also are the many feeding and spawning areas which were present back in the 1940's. As a result, commercial fishing and sport fishing have deteriorated. Individuals just aren't getting the fish they used to.

Reduced numbers of fish and wildlife are not the only factors causing discontent among sportsmen. Hunting conditions have also worsened. This fall the water rose as much as seven to eight feet from the time we began hunting in the morning until we finished hunting in the afternoon. This seven to eight-foot rise in water level resulted in a much greater change in the distance our blind sits from the water. The large increase in water flows is the result of Fort Randall opening its gates for greater electrical output during peak periods. As you can see, what may be good for Mom and the kids back home isn't necessarily good for Dad in the goose blind.

The sportsman can possibly live with his frustrations; waterfowl, however, may not be so tolerant. An example is the present fluctuation of the Missouri River below Fort Randall.

Sometime during the night the dam at Fort Randall is completely shut down. The result is that the whole river below the dam freezes over, making the area of little value to wintering and migrating waterfowl. By simply allowing more water to be released, the area below the dam could easily be kept open for waterfowl.

Economic and social factors have been the primary considerations of water resource developments in the Missouri River. Fish and wildlife have received little consideration. Hopefully, through citizen and sportsman concerns, wildlife values will receive greater emphasis in the future on the Missouri River.

Waterfowl is a renewable natural resource to this country. They presently produced production surplus that the hunter can harvest. Every state must realize that they have a moral and ethical responsibility to properly manage waterfowl, including the harvest, in the best interests of the waterfowl population itself and the people.

No man, after hunting for a few years, can help but develop some concern toward what is happening to wildlife habitat. Unfortunately, like many other types of wildlife, waterfowl numbers are declining due to loss of habitat. Waterfowl production areas in the form of wetlands are being lost at a rate of five percent per year in North Dakota and the prairie pothole region. Migration and wintering areas are also constantly being altered or destroyed by man's progress.

There is considerable effort being made by state conservation departments, the Fish and Wildlife Service, and sportsmen's organizations like Ducks Unlimited, to solve these problems.

One project being conducted in Nebraska is the establishment of local breeding populations of the Greater Canada goose in its former breeding range. When the pioneers first crossed western Nebraska, the Greater Canada goose was nesting in this area.