NEBRASKAland

September 1976

NEBRASKAland

VOL 54 / NO. 9 / SEPTEMBER 1976 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Sixty cents per copy. Subscription rates $5 for one year, $9 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. commission Chairman: Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 Vice Chairman: Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-Central District, (308) 745-1694 2nd Vice Chairman: Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-central District, (308) 452-3800 H. B. "Tod" Kuntzelman, North Platte Southwest District, (308) 532-2982 Richard W. Nisley, Roca Southeast District, (402) 782-6850 Director: Eugene T. Mahoney Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, Jr. Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: Jon Farrar Ken Bouc, Bill McClurg Contributing Editors: Bob Grier Faye Musil, Tim Hergenrader, Roland Hoffmann, Bill Janssen, Butch Isom, Ben Schole Art Director: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Came and Parks Commision 1976. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska SEPTEMBER 1976 Contents FEATURES THE WALLEYE WAY 8 GROUSE OUTLOOK 12 WRAITH OF THE VALLEY 16 THE DOVE IS BACK 18 PAWNEE PRAIRIE 20 HERITAGE IN CANVAS 32 BOW HUNTING BASICS 34 BUILDING A STAND 36 LADY IN ORANGE 33 ADVENTURES WITH WHISKERS 40 DEPARTMENTS SPEAKUP 4 TRADING POST 49 COVER: Pronghorn bucks will again be in demand come the September 25 opening of the 1976 Nerbraska antelope season. For a story on one woman's hunt, see page 38 of this issue. Photo by Jon Cates. OPPOSITE: A Missouri River sunrise near historic Indian Cave State Park in southeast Nebraska. Photo by Jon Farrar. 3

Speak Up

Where Is It?Sir / I write as a native-born Nebraskan, a 25-year resident and longtime subscriber, to complain about a pet peeve. My complaint is that in many of your articles you refer to historical sites or dams, creeks, etc. by name but never seem to place them for us by name of city, town or furnishing a brief map.

I, like many hundreds of your readers, have been away from Nebraska for many years and many of the places you write about have come into being since we left. But if you could locate them for us by saying "near Crofton" or "east of Beaver Crossing", etc., our mind's eye would place them.

I worked in more than 200 cities and towns in Nebraska as a telegrapher for several railroads from 1921 to 1940 and so know most of the towns and all the cities. Arthur Kellogg (mayor) Huntington Park, Calif.

We realize the problem exists, and will try to do better. It is a problem in many things we do, and in news releases we locate any places where there is a question. It is just more difficult in the magazine, as space is more critical. (Editor) * * * Following is a letter sent to the Corps of Engineers with a copy to the Game and Parks Commission. Dirty WaterSir / This letter is in answer to the application of the city of Lexington's permit to discharge effluent waste water into the Platte River.

You have taken into consideration public interest, conservation, the economics, aesthetics, environmental concerns, historic values, fish and wildlife, flood, water quality, navigation; the list goes on. You have considered many factors; but you have missed one very important one- mine.

The engineering firm made the environmental assessment of the proposed activity— 4 I'm sure they approved it and received a substantial fee. I do not believe their concern is for the environmental protection of the Platte River.

To give you a good idea of why I'm concerned, let me enlighten you on my position.

About 4 years ago we bought about 300 acres of river ground. We wanted country life and privacy. We built our home on this ground and became very close to nature. Now we are being invaded—infringed upon—our land character will be changed and the river that runs 11A miles through our land will be subject to future spoiling.

All our forefathers have used and benefitted from this river; our parents, ourselves and our children. We have really enjoyed the beauty and serene life it affords. We have spent many hours along this river of ours, astounded by the fury of the flood waters, wading during low water, winter ice skating on a side pond, swimming, fishing, canoeing. My list is endless too.

But, what will my grandchildren, great grandchildren and all the future generations to come, what will they do? They will never know and enjoy the river as we have.

Now I know the city engineers say the waste water will be "pure". Of course it might at first, but as the city grows and more industries develop, it will become less so. They concede that on overload days it will be quite visible and still less pure. Then there are days when the disposal plant breaks down. The result you know, I know, our city fathers know, but who cares? Only I will see it, smell it, and have to live with it, for as long as I live on my land.

I think our great nation and states had better now afford a better way to dispose of our waste, in a more beneficial way. Better now, as we all know cost will continue to spiral. Now, as when a job is not done right the cost is double to clean up and replace it.

What fools we are to take the short cuts to progress and give it precedence over nature's irreplaceable beauty. Our loss in appreciation and beauty of any river is so great; the future generation of tears will flood the minds of towns, states and even nations. I am only one but I want to fight for the tomorrows. Please reconsider this proposal. Mrs. Gordon Rimpley Lexington, Nebraska

* * *Yeah Snakes!

Sir / I applaud the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission for the recent article in the March NEBRASKAland on Venomous Snakes by John Lynch. The approach taken toward the subject of snakes is indeed novel. John Lynch pointed out brilliantly that snakes are as much a part of Nebraska's wildlife heritage as game species. The Nebraska Game and Parks Commission deserves congratulations for viewing non-game species as a natural resource rather than promoting the elimination of non-game species by activities such as rattlesnake hunts. Sportsmen can only gain by leaving the "bloodthirsty image" in our past. Thomas Hupf Lincoln, Nebraska

There are many sides to almost any issue, and certainly accepting all wild creatures equally is valid. We have since run a rattlesnake hunting story (August NEBRASKAland) but it is a hunt with a purpose. Snakes are far more useful than destructive, but rattlers do have a bad reputation, and it was not lightly earned. It is natural for them—it is just that no one likes being bitten and poisoned. If rattlers only struck their "meals" they would be much more readily accepted. (Editor) * * * Looking AheadSir / Presently I am in prison but will be out in a year or less. A couple weeks ago I ran across a number of copies of NEBRASKAland and it made me homesick for Lincoln. I'm a Jayhawker by birth and southern Californian by location, but I've always remembered the year we lived in Lincoln 12 years ago. I hated to leave and am seriously considering coming back.

Here, people want to live too fast, and after I finish my 5 years I want to slow down; to live where people are friendly and don't stare if you say good morning to strangers.

Maybe some people will think less of me because I'll be an ex-con. Well, I want to stay EX and live like other citizens. I believe that I can be a responsible citizen and be a credit to my community.

The reason I'm writing is because I'd like you to print this and to ask that any people living in Lincoln who are familiar with Civil Service jobs and such, or possibly private industry, and who could give me an idea of what to expect, possibly could become a "pen pal".

I have a lot of job experience and by the time I parole will be licensed as a waste water treatment plant operator (that's a euphimism for sewer plant operator), and have already passed the state civil service exam for stationary engineer I. If anyone familiar with these fields couid give me any information, I would appreciate it. Thanks. Dennis Datin B-45480 Box 600 Tracy, California 95376

NEBRASKAland Magazine invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to Speak Up. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters. — Editor. NEBRASKAlandThe Hornady Handbook... a ballistics gold mine

only $5.95

The Commonwealth now pays even higher interest rates!

6.25% Passbook Savings 6.54% Annual Yield Comp. Daily 6.75% 1 Yr. Cert. 7.08% Annual Yield Comp. Daily 7.00% 2 Yr. Cert. 7.35% Annual Yield Comp. Daily 7.25% 3 Yr. Cert. 7.62% Annual Yield Comp. Daily 8.00% 4 Yr. Cert. 8.45% Annual Yield Comp. Daily A substantial interest penalty, as required by law, will be imposed for e

TEN SPECTACULAR NIGHTS AT THE FAIR

SURPLUS CENTER

~ Nationally Known ~ World Famous ~

WOOLRICH Alaskan Shirt

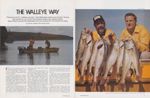

THE WALLEYE WAY

Fishing pro from "walleye country" tries Nebraska waters and scores. During spring trek to six of the Cornhusker state's top walleye lakes, Gary Roach proves that Nebraska fish are suckers for his trolled live bait

EACH YEAR a summer caravan of Nebraska fishermen heads to the "Land of 10,000 Lakes"-Minnesota-- to fish for the prize of freshwater table fare, the walleye.

Minnesota is noted for its walleye fishing. The state promotes it heavily, helping to make tourism in the northwoods state a $1 billion business. But, Nebraskans don't have to pack up their fishing gear to go walleye fishing in Minnesota, according to one Minnesotan who knows.

Gary Roach, pro fishing guide in the Brainerd, Minn., area for the past 12 years, believes that Nebraska has some tremendous walleye fishing right in its own backyard. The trouble is, most 8 Nebraskans don't know how to take advantage of it.

Roach is the field representative for Lindy/Little Joe Tackle Company. He and fellow fishing guides Al Lindner, Ron Lindner, Ted Capra and Rod Romine were among the original famous Lindy Tackle team, the guys who would come into a new area, spread out on a strange lake and find walleye seemingly under every rock and bush. They developed what is now commonly known as the Lindy method for catching walleyes; lots of walleyes.

Roach is now the lone member of the original fishing team, as the others have gone their separate ways. But the 38-year-old angler is still pulling his 15- foot boat all over the country, fishing new lakes and telling people how to catch more walleye at various times of the year.

One such tour of national lakes brought Roach to Nebraska earlier this year. He fished such lakes as Branched Oak near Malcolm, Republican City's Harlan County Reservoir, North Platte's Lake Maloney, McCook's Red Willow, Lake McConaughy near Ogallala and Merritt Reservoir south of Valentine.

NEBRASKAland

Unfortunately, Roach and the weatherman didn't coordinate their plans. Cold fronts moved through the state almost daily during his 10-day April trip. Still, the Minnesotan was able to get on the lakes, feel out Nebraska's walleye waters and determine tricks of the trade which would produce walleye for "Big Red" fishermen.

"Nebraska has a lot of good walleye water," Roach said. "The trouble is with the fishing technique most walleye fishermen use in this state. They think that the best, maybe the only way, to catch walleye is by dragging around Rapalas, Thin Fins or other trolled baits until you run over a fish. That's not the way to do it. Oh, sure, it'll catch fish some of the time, but consistent catches of fish can be had and live bait is the way to do it."

Roach and the Lindy method are firm advocates of the live-bait philosophy. Walleyes are bottom-feeding fish, so the place to fish for them is on or very near the bottom of the lake.

"All of the lakes I've been on in Nebraska have good underwater structure," he said. "By that I mean old road beds, rocky points, hard bottoms in otherwise soft bottom areas, dropoffs, brush, creek channels, anything that'll hold fish. What Nebraskans need to learn is how to locate such pieces of SEPTEMBER 1976 structure and they'll generally locate fish."

Boats are essential for the avid walleye fisherman, according to Roach, since most walleye fishing will be in or around deep water, which isn't often close enough to the bank.

A fish locator is also an important part of better walleye fishing.

"A locator, and knowing how to use it, will help improve your fish catching by 60 per cent, at least," said Roach. "It's your eyes to the bottom. It can tell you what kind of bottom you have, if it's soft or hard. It will tell you if there is a good dropoff or if the lake is flat. It can even tell you if there are bait fish under you, and when you find bait fish, you can bet walleye, northern or bass are close by."

The Lindy method can be boiled down to three basics: backtrolling much of the time; use of live bait; and versatility of fishing approach.

Backtrolling is just what the word implies—trolling backwards. "We've been accused of doing everything backwards," said Roach of the Lindy team. "But really, the backtrolling method allows for maximum boat control. Your motor is the boat's pivot point. Generally, your locator transducer is also mounted on the back of your boat. By trolling backwards, you are able to follow your underwater breaklines better, troll your boat slower (wave action hitting the back of the boat slows it down and the slower one trolls, the better, as it keeps the bait in front of fish longer), and it allows you to fish three people out of your boat without having to worry about lines becoming tangled in the motor or with each other."

The favorite of the live-bait rigs is the nightcrawler. A special rig is a leader of eight-pound monofilament, slip sinker and swivel. The nightcrawler is hooked in the top of its two bands, then injected with a needle and given a puff of air under its second band. In this manner, the crawler will float six inches or so off the bottom when trolled slowly or drift fished.

During the spring, minnows (slightly larger than crappie minnows) are used, hooked (Continued on page 44)

11

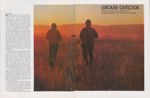

GROUSE OUTLOOK

Far from a peak year, 1976 lull can be blamed mostly on extremely dry weather

NEBRASKA'S GROUSE SEASON opens September 18 this year. Depending on where you hunt, expect a poor to average season. Several years of below-average rainfall has knocked grouse numbers down over most of their Nebraska range. And, overgrazing followed on the heels of the dry spell over much of the sandhills, resulting in loss of nesting cover. Even with frequent rainfall through the summer, it would have been too late to increase grouse numbers for this fall's season.

"It's not shaping up to be a good season overall," Ken Robertson, game biologist at Bassett said after tabulating the spring breeding-ground survey. "We've got two kinds of grass in the Sandhills this summer—short and brown. Our survey showed the number of grouse on the display grounds 24 percent below the 5-year average. There was a greater decline in the number of sharptails than in the number of prairie chickens. The 1964 year was our best grouse season in recent times, and compared to then, sharptails are down 78 percent and prairie chickens down 54 percent. Hunters who remember how it was in 1964 have not been satisfied since."

Robertson said that grouse breeding habitat is in worse shape now than he has seen it during his 11 years in the Bassett area. He explained that when a drought period strikes, many ranchers continue to pasture their range with the same number of cattle. The result is a further decine in the grass cover needed by grouse to successfully bring off a clutch of birds. Winter cover declines, too, and fewer birds come through those months of stress. There is no doubt that grouse populations fluctuate naturally, but several years of dry weather in a row has further depressed their numbers.

"I would not expect some of the public areas, such as the Valentine National Wildlife Refuge, to have as severe a decine in grouse as on private land," Robertson continued. "The national forests and wildlife refuges are managed with wildlife needs in mind and consequently are not pastured as heavy. By and large you have better range management programs on these areas."

Alvin Zimmerman, conservation officer out of Valentine, probably covers as much grouse country as anyone in north-central Nebraska. He said that this was the fourth consecutive year of below-normal rainfall in his area and the status of grouse has gotten progressively worse as conditions became drier. "I've been up here since 1965," Zimmerman 12

Zimmerman said that when grouse numbers are up there is no shortage of good public land to hunt in north-central Nebraska. Over half of the Valentine National Wildlife Refuge's 71,515 acres are open to grouse hunting. Refuge land east of highway 83 is closed but most land west of the highway is open. The McKelvie Division of the Nebraska National Forest, located southwest of Valentine, has 116,000 acres of sharptail range, most of which is open to grouse hunting. The number of access roads is more limited on McKelvie and four-wheel-drive vehicles are useful but not necessary. Public camping is not allowed on the Valentine refuge but nearby Ballard's Marsh Special Use Area offers campsites, water and half-moon facilities.

NEBRASKAlandThere are several thousand acres of public grouse hunting land surrounding Merritt Reservoir. The grassland around Merritt is not pastured and generally offers hunters plenty of shooting opportunities. The public land encircling Merritt is one quarter mile or more in width and the boundary with private land is easily identified by a well maintained fenceline. Camping facilities are available near the dam.

No area in Nebraska receives as heavy grouse hunting pressure as the Bessey Division of the Nebraska National Forest near Halsey on Highway 2. The Bessey Division is the closest public land to Nebraska's population centers and offers the best camping accommodations. The southern Sandhills area has received more rain in the last two years and consequently has better cover and probably better grouse populations than public lands in the Valentine area.

The Nebaska Game and Parks Commission conducted extensive grouse research on the Bessey Division from 1962 to 1973. Grouse and grouse hunter habits are probably better understood for this area than any other in the state.

SEPTEMBER 1976In a recent research publication, biologist Leonard Sisson writes that "because of access, the most heavily hunted part of the Forest was west of a line running north and south along the eastern edge of the plantations. Within that area, most hunting occurred within one mile of a major road. An average of 52 percent of the (hunting) effort and 51 percent of the reported harvest occurred during the first week of the season." Over 70 percent of the hunting pressure on the Bessey Division was during the first two weeks of the season. Nearly 80 percent of the hunting was done on weekends. From those statistics it is clear that if you want to avoid the crowd, pass up the early part of the season and weekends. This probably applies to all public as well as private land in the Sandhills.

From 1971 through 1974 about 15,000 acres of the Bessey Division were closed to vehicles in response to numerous complaints from walking hunters. Trail bikes and four-wheel-drive vehicles had become an annoyance for the majority of the area's grouse hunters. During a subsequent survey, over 87 percent of the grouse hunters on the Bessey Division indicated that they preferred hunting areas closed to vehicles. Most of those hunters had traveled over 100 miles to hunt grouse and sought an enjoyable, extended hunt. Most used dogs and preferred to walk for their birds. In short, restricting the use of vehicles improved the quality of their hunt. In 1975 the vehicle ban was lifted because of federal regulations requiring evidence of environmental destruction or adverse effects on wildlife before such restrictions could be imposed. Such evidence has been submitted by Game Commission biologists and it is possible that vehicles could be restricted for the 1976 season. Check at the headquarters building for rules and directions before leaving the road at the Bessey Division.

The last large public grouse hunting area in Nebraska is the Crescent Lake National Wildlife Refuge located between Alliance and Oshkosh. Nearly 41,000 acres of this refuge are open to grouse hunters. Maps designating open areas and trails are available at the refuge headquarters. There are no camping facilities at Crescent Lake or in the immediate area.

"Hunting pressure is very heavy the first weekend," Ron Perry, refuge manager, reported. "We generally have a few hunters that stay through the first week. During the second weekend we will still have moderate numbers of hunters, and after that only scattered activity. (continued on page 48)

15

Wraith of the Valley

NO GHOSTS in full daylight? Think again. Better yet, just follow the route I took recently. On a gray, misty day, with my wife as passenger, I drove leisurely a few miles on a main thoroughfare leading out of the Valley County town of Ord. We had no particular destination in mind.

Thinking to add to the variety of our outing, I turned left upon a gravel road. A quarter-mile farther, upon a sudden impulse, I turned in at an old, abandoned farm-house. Perhaps I made the turn because my wife, the former Bess Mason, had known the owners of the farm in her days as a child and later as a country school teacher, now more than a half-century before.

I drove into the farmyard upon a narrow dirt road edged with dried stalks of sunflowers and thistles. At one side was the abandoned farmhouse with its weed-grown front yard and a tottering old clothesline. On the other side were a tumbledown comcrib, a rickety, weather-beaten 16 old barn and the rusty remains of a long-abandoned tractor.

Abruptly, only a few feet ahead of us, the "thing" appeared. Without warning, there loomed a ghastly form, clad in a strange, misty shroud, beckoning me on, daring me, as it pointed the way along the ragged road which appearedi to turn sharply behind the dilapidated wreckage of what had once been a granary.

It was then that I realized that we were about to be trapped against a barbed-wire fence which surrounded a crumbling pit silo. Quickly I turned the car away, from the misty figure which continued to motion me on, shifted the gears into reverse and started backing out on the narrow trail by which I had entered. At several points, the rear wheels of the car ran off the narrow road, and in my haste I was obliged to maneuver dangerously back into the track.

Once we were safely back upon the gravel road, I NEBRASKAland looked back and saw again my pallid guide, this time standing statuesquely in the front yard, leering at us and suddenly accompanied by what appeared in hazy outline to be several families of human beings—stern-faced men, work-worn women and unsmiling children, all in dismal, gray garb, and with the typical family dog lying nearby.

Silently, motionless, patiently they watched us, without apparent hostility but as though sadly without hope—those weird images intuitively recognizable as ghosts of days long gone. Over the entire group hung a cloud of bluish vapor, a symbol of their faded dreams and shattered hopes, of great ambitions not achieved—all hedged by poverty, misfortune and misery.

About them lay the material evidence of their ruined years: the bronzed lawn area smothered beneath a mat of weeds; leaning fence posts and sagging wire fences; a collapsed windmill tower; rotting boards and strips of SEPTEMBER 1976 roofing from buildings which had been their pride—rubbish and ruin on every side. Mutely our hosts stood brooding, despairing. Worst of all, there was silence everywhere-a depressing, deathlike silence.

Suddenly, from the rear of the group, emerged a leering, shadowy figure, the one who had tried to trap us at the decaying silo pit. As it neared, one hand was raised commandingly, as though indicating that we must not move.

Quickly I stepped upon the accelerator. The car leaped forward, striking a previously unnoticed "No Trespassing" sign and toppling it into the roadside ditch as we sped for the highway. There I turned my car resolutely toward home, meanwhile looking back for a last view of the scene of our adventure. The mist over the old farmstead had cleared; the sun was shining through the clouds. In the distance, against a background of freshly plowed fields and greening hills, the first rays of a rainbow appeared. Ω

17

THE DOVE IS BACK

Jerry Lambert's tree is our focal point during state's first season in 23 years

A TREAT THAT'S BEEN denied for a long time is sweet when finally sampled, but it's doubly rewarding when you've invested a lot of time and effort in winning it. That's what Cal Christline and I felt that fine September afternoon in 1975.

That day, the land looked rich, laden with man's ripening crops and splashed with nature's artistry. The monotonous green of the summer landscape was already breaking, with hints of scarlet in the sumac and a few leaves of the cottonwoods and ash turning gold. And, though it had been a dry summer, the corn ears and milo heads hung as heavy as any reasonable man would expect.

A persistent sun had burned through some dark clouds as if to heighten our perception of the scene, as Cal and I strolled down a draw behind his father's farmhouse east of Sterling. Though glad to see that the drought had left a crop, we were looking for another kind of harvest. Cal and I were after mourning doves, which had just been added to Nebraska's list of game birds that year.

Cal and I were accompanied by former Sterling resident Jerry Lambert. Jerry was living in Omaha, where he headquartered his efforts as a regional representative for Winchester-Western. He and Cal also collaborated on a small gunshop in Sterling.

Neither Cal nor I had hunted doves before the 1975 Nebraska season. And, when the curtain rang down on the sport in 1953, I was small enough to have been knocked flat by the kick of any shotgun, provided I could have mustered the strength to shoulder one.

We had listened to dove hunting yarns, both from "oldtimers" who had been around prior to the 1953 closure, and from the fortunate few who could afford the time and expense of an out-of-state hunt. And, we had read about dove hunting in other states. Like a lot of Nebraska sportsmen, we couldn't understand the logic behind a Nebraska law that prohibited a dove season even though the Cornhusker State boasted the third largest dove population in North America. Especially when doves were hunted in over 30 other states.

The answer was, of course, that there was no logic behind that old law; only emotion and half-truths. It took Nebraska's sportsmen many years of patiently explaining the facts to their friends, community groups, lawmakers and other sportsmen. But finally, sound biological data was heeded. The first Nebraska dove season in more than 20 years opened on September 1, 1975. And, like a lot of other sportsmen, the hunters in our party that day appreciated the sport all the more because of the work they had invested in reopening the dove season.

That first 30-day season was about two-thirds gone when our party got together. I had had varying results with my 17-year-old trusty, rusty, department-store scattergun. So, Jerry outfitted me with a shiny new pump gun, vented rib barrel and all. He screwed a tiny contraption into the business end that he said was a removable choke, this one bored modified.

That little shootin' iron proved to be the sweetest-handling scattergun I had shouldered for many moons. I 18 was to down nine doves that day with about 20 shots, far better than I had done on any previous hunt. But, alas, a heartless Jerry reclaimed the little jewel at the end of the day, telling me that I could find it's twin at reasonable terms in most any gun shop.

I got my first chance to try it shortly after we started down that draw. Jerry headed for the bleached skeleton of a dead cottonwood where the draw, a pasture and a cornfield came together.

On the way, he boosted several doves from the weeds. Jerry dropped one and Cal dusted another. All I got for my trouble was a little trigger-finger exercise.

But I did better on my next opportunity, dropping a double from a little bunch flushed from the weeds along a corn field, while Cal blasted modified and improved- cylinder holes in the air. Though I had made a mental note of where each bird fell, it took considerable combing of the corn before I retrieved both doves. The heavy September foliage and the bird's drab gray color made them hard to spot on the ground.

We were not trying to walk the doves up like a pheasant or quail hunter would, but we had about five birds between us when Cal and I arrived at our first stakeout, a pond flanked by milo and plowed wheat stubble. According to everything written about dove hunting, that pond should have been a real hotspot. But, 45 uneventful minutes sent us in search of another location.

A chorus of shotgun music from Jerry's dead cottonwood was hint enough. We marched off in his direction and took up stands a respectful distance from his perch beneath the old tree.

At that point, Cal produced a few dove decoys in hopes of stimulating a little more action. A fence offered about the only logical dove perch around, though it was tough to balance them on the barbed wire in a natural position.

It appeared as if we were on an established fly way, with little bunches of doves working their way along a nearby creek and out over the pasture behind the dead tree. We all got a few shots, and Cal and I collected another couple of birds apiece.

Jerry, however, was doing considerably better, accumulating a half-dozen birds in short order. He was shooting a new model auto-loader his company had developed, and it seemed to suit him perfectly. He began to leave the easy incoming shots for us, taking only the tougher crossing shots at long distance.

Of course, Jerry would probably have done well with a single-shot .410. His work with Winchester had taken him to other parts of the country that offered dove seasons, giving him ample opportunity to brush up on his wing shooting. He also conducted many shooting exhibitions while promoting his company's wares.

Action at the cottonwood was sporadic, with several groups of three or four birds passing through within minutes followed by 20 minutes of empty skies.

I scratched one bird from just such a group and marked him down in the weeds along the fence separating the pasture and cornfield. Making sure no more NEBRASKAland doves were approaching. I strolled out across the open pasture after him.

Although the fence separating the fields was low enough to straddle with ease,! decided to practice what I preach in Hunter Safety courses. I unloaded the gun and laid it under the bottom wire on the other side. Then, I began to cross.

For some reason, I looked up just as I straddled the fence and noticed a nice bunch of about a dozen birds coming our way. Cal and Jerry had spotted them, too, and were eyeing me anxiously, hoping that I would hot spook them off. I got their message and hunkered as low as I could over the barbed wire, ready to sit this one out and just watch.

The results were predictable. Four or five shots were fired and two or three doves fell. I just happened to be looking at one of the birds as the last shot rang out. I noticed him flinch a bit and saw him lose a few feathers, but he didn't fold easily like most doves. Instead, he kept on flying and came right along the fence toward me.

I knew the bird's chances of surviving with a wound were slim. My shotgun lay at my feet, open and ready for a shell, and the shot would be an easy one, I told myself. With just a split-second's consideration, I decided to try for the bird. I got the gun off the (Continued on page 48)

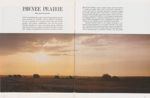

PAWNEE PRAIRIE

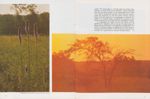

Only a hundred years ago, luxuriant grassland spread from horizon to horizon across eastern Nebraska. In just a quarter of a century, that rich mix of tall grasses and prairie wildflowers was all but gone. Spindly threads of native grassland along railroads and out-of-the-way patches escaped the plow's sharp bite. Today, only guarded remnants of prairie remain

"PAWNEE PRAIRIE is just a stone's throw from the Kansas border and eight miles south of Burchard, Nebraska. A small creek with its attendant deciduous woodland angles across the northeast corner of the area's 1,120 acres. Most of Pawnee Prairie, though, is just that-prairie-with a full complement of grassland wildlife. It is the largest remaining tract of tall-grass prairie in southeast Nebraska. Best of all, it is a State Wildlife Management Area, maintained for public recreation by the Nebraska Game and f^arks Commission.

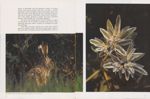

Because Pawnee Prairie is an isolated remnant of Nebraska's native grassland, it is of special interest to the naturalist. During the late summer and early autumn, the prairie is

ripe with fruit and seed. Compass-plant, which provided a resinous chewing gum for pioneer children, the tall purple

21

spikes of gayfeather and the generous sweeps of Queen

Anne's lace are the prairie's last show of color. A natural

blending of forbs and grasses utilize all available water, sunlight and space in the dark prairie sod. The patient observer

may see an occasional male prairie chicken return optimistically to the display grounds of spring, and tawny grassland

sparrows dart through the waist-high vegetation.

spikes of gayfeather and the generous sweeps of Queen

Anne's lace are the prairie's last show of color. A natural

blending of forbs and grasses utilize all available water, sunlight and space in the dark prairie sod. The patient observer

may see an occasional male prairie chicken return optimistically to the display grounds of spring, and tawny grassland

sparrows dart through the waist-high vegetation.

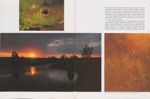

But more than anything else, Pawnee Prairie is a place for recreation; for the Sunday morning quail hunter, pond fisherman after bass, hikers, campers or a neighbor boy gigging bullfrogs.

More than 20 ponds capture the runoff that formerly flowed to Johnson Creek. The pond's grass-filtered water is blue and deep, inviting swimmers and fishermen. Three of

The primary justification for the purchase of Pawnee Prairie was to sustain southeast Nebraska's shrinking population of prairie chickens. As more and more grassland was turned under for row crop production, the once abundant grouse declined in numbers. Today, Burchard Lake and Pawnee Prairie are bastions for the prairie chicken in southeast

Nebraska. On Pawnee Prairie, their numbers have stabilized at about 85 birds.

Nebraska. On Pawnee Prairie, their numbers have stabilized at about 85 birds.

To enhance prairie chicken habitat, most of Pawnee Prairie is maintained in native grassland. For years, haying was the primary management tool used to slow the invasion of woody shrubs and trees and to rejuvenate grasses and forbs. During the last three years, Game commission land managers have tapped a natural force of the prairie, fire, to scour the sod of matted vegetation, control woody plants and to invigorate the plant community.

A substantial portion of the area is in woodland, shrubby draws and occasional food plots though, and that is a boon for the hunter. Quail, doves and white-tailed deer are the area's primary game species.

Bobwhite hunting is good but limited to the creek bottom and weedy areas. Johnson Creek and draws fingering into it, make the walk from the parking lots well worth while. As in most of southeast Nebraska, the best quail habitat is also the best for cottontail. In recent years, Game Commission land managers have allowed trees and shrubs to increase on some parts of Pawnee Prairie and the whitetail population has expanded significantly. Even though the creek bottom is a natural for bow hunters, there is little hunting pressure on deer.

An already good duck hunting situation on Pawnee Prairie was made even better with the addition of more aonds and the closing of the area to vehicles. The absence of numan disturbance and the presence of abundant water

Pawnee Prairie is also an ideal mix of watering holes, food plots and mid-day loafing trees for mourning dove hunting. The ponds draw doves like magnets in the late afternoon, numerous hedge and locust trees provide mid-day jump shooting, and the food plots attract feeding birds.

There are no formal camping areas at Pawnee Prairie but primitive campers have the run of the entire 1,120 acres. Open fires are not allowed and Pawnee Prairie was closed to vehicles last October. Service roads function nicely as hiking trails for backpackers. Food containers should be carried out and campers and hikers should avoid disturbing the natural environment as much as possible. There are four parking lots, two on the east side and two on the west.

Visitors to Pawnee Prairie should be aware of, but not unduly alarmed at, the occurrence of massasauga rattlesnakes. 28

By September, the nights will be cool. Doves will be gathering for migration, and the season's first bluewings will begin arriving. Pond bass will be greedily building their winter fat. Cool-season grasses are beginning to eclipse those of summer, and the first blush of fall will sweep across the bottomland. It's a good time to discover Pawnee Prairie. Ω

Heritage in Canvas

Desire to preserve mementoes from the past brought an artist and subjects together for the Bicentennial

SENTIMENT FOR the things of yesteryear has played an important role in the philosophies and lives of Harry and Helen Obitz of Red Cloud. Long in love with collectable and portable antiques, it has been a long-time priority with the Obitzes to appreciate and preserve vanishing Nebraska landmarks.

Thus it came about, when an appropriate and worthwhile project was needed for the Red Cloud community to commemorate the Bicentennial year, that Mr. and Mrs. Obitz thought of preserving the rapidly vanishing sights of the Nebraska prairies in oil paintings. They realized the impossibility of true preservation of all the larger and more permanent landmarks.

Elnora Robertson, an artist of Red Cloud, was commissioned to capture some of the vanishing landmarks in oils, and she produced 33 paintings. Included are once-common but now rare objects such as foot-powered grindstone, a soddy, clapboard buildings, the trusty hand pump, and other curios.

The collection, according to Obitz, represents "a documentation of vanishing landmarks, most of which could have been seen in the Red Cloud area. There is a truism in the antique and museum field that states that the most common items, those used over a long period by a great number of people, are the first to be discarded when something better comes along. So, spinning wheels became an oddity quickly after they were no longer needed in every household.

A trend has developed nationally which shows that a great number of people hold considerable reverence for objects from the past. This may be primarily nostalgia for relics of an age when relatives were trying to settle the land, and there might be some monetary concern as well, but the fact is that almost anything old has value—sentimental or otherwise.

As time marches on its inexplicable course, curiosity develops and refines the new, and sentiment does what it can to preserve the past. Fortunately, there are getting to be a good number of sentimentalists who find value in more than utilitarian innovations and gadgets.

Artist Robertson was actually partly responsible for the project undertaking, as she is also interested in preserving the past. One of the subjects, the barn and silo in the upper right, was the place where she lived previously. "Changes in rural Nebraska are taking place rapidly," she said. "In fact, several of the sites done for this collection have since disappeared. Even the old barn on our home place has fallen down."

Several of the subjects in the collection hold special meaning to her, with the pump house, shown here in the center, being perhaps the most intriguing. The Red Cloud depot, made famous in the writings of Willa Cather, and now preserved as part of the Catherland "memorabilia", has drawn the most comment from viewers.

Presently, the Obitz collection is being booked for display across the state, and it will eventually be donated to an appropriate institution by the Obitz family as a permanent display. Ω

Elnora Robertson is a native of the Red Cloud area. Her interest in art developed while in high school, and she began working in oils about 10 or 12 years ago. She now prefers painting on consignment. 32

THE BASICS OF BOWHUNTING

YOU DONT KNOW the meaning of buck fever until you've hunted deer with a bow. When you're rifle hunting and see a deer, chances are you've got the safety off in one second and a second later it's all over. The first buck I killed with a bow was in 1966. He was coming down a trail very gingerly, stopping every now and then to look around. He'd rub on a willow a little bit, look around, walk a few steps and then pause again. His ears were wagging around like semaphores and he tested the air several times every minute. By this time you're really getting up tight knowing that he is coming toward you. I watched him coming for a good 20 or 30 minutes. By the time he was in range I was nearly a basket case. My temples were throbbing so much I thought I was going to have a stroke. My hands and feet were numb and I lost all feeling in my lower lip. I don't remember shooting; it was purely from instinct. I remember seeing his eyelashes but I don't remember pulling back on the bow string. The next thing I knew I was on the ground looking like crazy for a blood trail.

That first deer taught me a lesson: the key to successful bow hunting is practice, practice and more practice. I had shot thousands of practice arrows that year. It's probably not so important that you can hit a paper cup at- 30 yards as it is to be able to shoot instinctively. There is no way you can stop and think about it when that buck is right under you. You can't say, OK now, I'm going to raise my left arm; now I'm going to draw back and now I want my thumb to hit my anchor point at the corner of my mouth. To be successful I'm convinced that you must be able to "react" to a deer passing by you.

It's important that you practice under conditions similar to those you'll meet in the field. I always wear my hunting clothes when I practice. That means shooting with coveralls, hat, shooting gloves and head net. If you hunt late in the season, practice with a heavy coat on, or with insulated underwear. A slight change in clothing can completely change your shooting style.

I try to do my practice shooting from the same height that I'll be in the field; 10,12 or 15 feet. When I first started hunting, I had access to a lumber yard and practiced shooting from the catwalk. Often I'll drag one bale of hay out 30 or 40 yards and shoot practice arrows at it from the top of the bale pile. If nothing else, shooting from a step ladder will help. If you're shooting from up high, you'll tend to shoot high. Unless you're a tournament archer, I don't believe in standing in the yard and letting arrows fly at a paper target 30 yards away.

For targets, use a crude cardboard cut-out of a deer. I concentrate on that vital area just behind the front shoulder. Your total concentration has to be on that one spot. Pick a spot, don't shoot at the entire deer. I did this once in 1969 and made my first and only gut shot. I made the mistake of looking at those antlers right up to the time I released the arrow. I was shooting at the whole deer and I hit the whole deer, but not where I intended. (Rupp found that buck in 1969 and it scored 144 in Pope and Young competition; 29 points over the minimum requirement. Editor)

34Hunting whitetails with the bow is about the ultimate challenge that a hunter can accept. You have to get close to make a clean kill with a bow, and you know that the whitetail has you whipped in all the senses, especially smell and hearing. And then, while you're within 20 or 30 yards of the animal, you have to make several movements; pivoting and drawing back. I've hunted during 10 seasons with rifle and can say that there is no comparison in the amount of patience and skill required to take a buck with a bow and arrow.

I had the privilege of hunting with Fred Bear several years ago. We spent one whole evening talking about hunting the whitetail. Considering that he had hunted polar bear, lion, bighorn sheep and dozens of other big game animals all around the world, I was surprised to hear him say that he considered the whitetail the most difficult trophy to take with the bow as far as the innate intelligence of the animal is concerned. He feels that the whitetail is what bow hunting is all about.

Apparently a lot of Nebraska hunters agree with him. In 1955, 173 bow hunters purchased deer permits. In 1965 the number had climbed to 2,618 and last fall just short of 10,000 archers were afield in Nebraska. With rifle deer permits in short supply, a lot of hunters have turned to the bow. I'm all for the serious bow hunter, but one of my peeves is the rifle hunter who runs out, buys a bow and goes hunting just so he won't miss a season. Any game animal deserves more respect than that. Those hunters don't realize that they have gone from a sophisticated weapon to a primitive one and that there is more preparation involved than just buying a permit. It is every hunter's responsibility to minimize crippling losses, and a big part of that is mastering your equipment.

35

Part of the bow hunter's responsibility is using the best equipment available. The only bow I've ever used is a 50-pound Ben Pearson. There are a number of good quality bows on the market made by reputable archery equipment companies. I personally do not use a compound bow. Compound bows are just additional paraphernalia and I have enough trouble getting through the timber and brush with my little bow. With a conventional bow it takes a lot of practice to develop the muscle tone in the shoulder needed to draw and hold for several seconds. The individual who feels he cannot efficiently hold a conventional bow at full draw long enough to make accurate shots should probably consider a compound bow.

Buying arrows is no time to try and save money. Again, I think that the archer owes it to his quarry to make a clean, quick kill and good quality arrows are an archer's most important piece of equipment. I prefer aluminum arrows. I would not consider using cedar shafts just to save a few dollars. They (Continued on page 46)

36BUILDING A STAND

ARCHERY HUNTERS across Nebraska have entered the fields and timber each fall since 1955 in search of white-tailed and mule deer. Since that first season, the technology involved in the manufacture of archery equipment has advanced tremendously. The bow has changed from a simple string and curved stick to a complex network of wire cables and pulleys capable of pushing an arrow at velocities exceeding 200 feet per second. The arrow itself has evolved from a wooden shaft of cedar, fletched with turkey feathers, to one of aluminum or fiberglass mounted with plastic fletching for stability.

As the equipment became more sophisticated, many archers turned to their tree blinds with improvements in mind. By moving the blind a couple of feet higher and nailing on a few more boards, it looked better and therefore must be more effective. The end result of this remodeling, in many cases, was a blind resembling the kids' tree house; too high for effective archery shots and conspicuous to both deer and other archers.

When building a new tree blind or revamping an old one, several factors must be considered.

The landowner who has given you permission to hunt should be notified of the blind construction. He may not want a blind in a certain tree or area, and as your host should be consulted. This will also eliminate the possibility of unauthorized hunters building blinds and the landowner mistaking them for yours.

In terms of archery success, proper blind location is the most important factor. To build a blind in the best possible spot, a bow hunter should first consider the behavioral patterns of deer.

Deer are creatures of habit. When not disturbed, their daily routine may remain the same for weeks or even months. Their home range will vary from one half to one square mile depending upon the terrain. Within this area, deer will have definite travel SEPTEMBER 1976 lanes between feeding and watering areas and bedding grounds. Deer feed primarily at night and travel during the morning and evening hours, bedding down during daylight in the thick cpvqr of buck brush or weeds. Active feeding areas can be identified by fresh tracks or droppings and are generally located in open meadows, grain fields or along the edges of heavy timber.

The most active travel lane between bedding grounds and feeding area is the ideal location for a tree blind. To increase the chances of seeing deer and possibly getting a shot, a bow hunter should study an area several times before deciding on a blind location. This should be done several days before the season if possible, when travel lanes are well established and food supplies are still plentiful.

Archery tree blinds should be simple both in construction and in materials. The blind should be approximately 10 feet above the ground and allow a good view of travel lanes and surrounding area. From this height, human scent will carry nearly 100 yards before settling to ground level. It should be from 10 to 30 yards from the expected target point. Arrows released from ranges of less than 10 yards seldom hit a vital area. At such close range, deer are more apt to hear the bow string when released or detect the archer's movement and jump out of the path of the arrow. The natural setting should be altered as little as possible and one should make use of half-fallen trees or broken limbs which may serve as ready-made blinds. If other materials must be used, they should blend in with the natural surroundings.

The first problem most blind builders encounter after selecting a tree is how to climb it. Methods for ascension range from the squirrel technique to rope ladders and seven-inch gutter spikes. Whatever method used for climbing should have as little detrimental effect on the tree as possible and should be removed after each use or at the close of the season.

A fork of a tree is generally used when building a blind. Larger limbs may also work well, especially if they extend over the travel lane.

As the majority of archery hunters shoot from a standing position, the blind should be wide enough for adequate footing and fairly level. The platform and its foundation must be strong and steady enough for weight shifts. Boards measuring two by four inches or two by six inches work well for all parts of the blind.

Most archers use nails to assemble their blinds and secure them to the tree; however wire and rope are also used. Rather than cutting away the bark of the tree to fit and nail boards, shape the boards to fit the tree with a saw or wood chisel and use longer nails. Galvanized nails are recommended as they will not rust and therefore have little effect on the tree.

The base or foundation of a blind is the most important part. It should be solid and perpendicular to the platform if possible. In some cases, two base boards may be necessary depending upon the angle of the fork or limbs. These boards should be grooved on one end to fit the tree and sawed on the other to fit flush with the platform if angles require. Once the base is in place the cross piece should be measured and cut to fit. It should then be nailed in at least three places on each end to prevent it from tilting or working loose.

If new lumber is used it should be left outside to weather, thus eliminating any scent of the curing process and discoloration due to factory dyes. This can also be accomplished in part by smearing mud on the boards after the blind is completed.

Blinds made in this manner are strong, durable and easily removed at the end of a season. They also have little negative impact on either the tree or the total forest environment. Upon removal the materials can be salvaged and used again the following season.

Archery deer hunting is an exciting sport and continues to grow in popularity every year. By learning about deer and their habits and applying that knowledge to blind building, the archery hunting experience will be much more enjoyable. Ω

37

LADY IN ORANGE

Often along but never hunting, this woman is convinced that gals appreciate the experience as much as men. Knowing mechanics of the gun is important, she feels, and adds to enjoyment

THE HALF-RATTLE buzz of an infrequently used alarm clock, a few pinches of anxious moments anticipating the day's events to come, and a large measure of the indescribable fragrance of early morning country air. Blend in a savory breakfast in a room filled with strangers clad in bright orange attire and add the brilliance of the morning sun peeking over the horizon. Top it off with the echoes of a distant rifle and serve with a never-ending panoramic view of the Nebraska Grasslands.

Undoubtedly, this enticing recipe describes the memorable activities implanted in the minds of many antelope hunters throughout the state. Of course, we must include a quick scan of the horizon with a set of dusty binoculars and then—what's that! something unfamiliar—a slight focus adjustment and I'll be darned! It is! A female-type antelope hunter!

The appearance of women with each new hunting season is becoming more commonplace in all aspects of hunting. Such is the case of Mrs. Larry Koester of Allen, Nebraska. The actual hunting is a new experience for Gloryann. The other factors of the hunt she has enjoyed, and can call up many fond memories of the past.

A further investigation from a typical sandhill knob strewn with those little green things that somehow get stuck in your elbows and knees, revealed what the Koesters would temporarily call home. A small green tent, next to an inviting trout stream, was nestled in a picturesque little valley south of Harrison, Nebraska.

Gloryann and her husband Larry arrived at their campsite in the early afternoon the day before antelope season. The tent was soon erected and a few brief hours of sunlight still remained, allowing for a brief scouting expedition. Unlike past years, Harry was the observer and scout for this trip. An evening meal prepared on a campstove and a good night's sleep put the final touches on preparations for the days to come.

The first day of hunting opened, revealing cloudy skies and a rather chilly northwest wind. It soon became evident that the area was teeming with the swift-footed little speed merchants known as pronghoms. Puffs of dust and the bristle of white rump hair could be seen drifting across the distant slopes of the sandhills. Gloryann soon realized that the task of approaching 38 these wary, fleet animals would be a demanding encounter for a rookie. The sneak-up-and-peek-over method often revealed only distant dots or silhouettes that might be Antilocapra americana. A quick check through the binoculars and her suspicions were confirmed. There they would be, standing and staring back with their own telescopic vision, muscles toned for a speedy sprint to safety.

It was soon evident that the area contained enough hunters to keep the antelope moving, and so a "sit-and- wait" period was initiated. Anxious moments of anticipation were short-lived as Gloryann's mustached, binocular-toting husband/guide shouted, "There they are!" Four antelope, tended by a nice buck, caromed down the slope in a 50 mile-per-hour dash. A quick positioning of the rifle, a click of the safety, and four shots echoed through the morning silence. Lesson number one in proper lead had just unfolded and was stored in the back of her mind to improve her chances when the next opportunity arose.

Two similar situations were encountered during the remaining daylight hours, along with a quarter-mile sneak which was terminated by a 200-yard standing shot that could have been scored only in a horseshoe-pitching contest—close but not a ringer.

The moment of disappointment was soon erased during an evening spent recapping the day's events with the landowner, Bob Manns, and his wife. After garnishing the day with western Nebraska hospitality and a moon-lit campsite, a very tired hunter drifted off to sleep.

Sunday morning was to bring a day that could be accurately described as a rerun of the previous day's activities. The antelope were like ghosts, suddenly appearing and disappearing in a mysterious elusive manner as they became more aware of the presence of man (and woman) in their domain. Sunday was soon another day past, and the unfamiliar strain of extensive walking and toting a heavy gun had left her very weary. Again, the night would be too short, but a pre-dawn helping of bacon and eggs and a cup of hot coffee soon restored her enthusiasm.

The lessons learned from the experiences of the two previous days were about to pay off. Less than one hour after sunrise, a small herd of antelope loped into sight on a nearby slope. After spotting their pursuers, they broke into full stride. Again, Gloryann leveled the heavy .25-06 rifle, peered through the scope, estimated lead, and squeezed the trigger. Her antelope came to a dusty stop from a well-placed shot in the base of the neck. Larry excitedly glanced over at his wife who was shaking in disbelief. Her recent dreams had suddenly became a reality. A 275-yard shot at an antelope in full sprint is excellent in any hunter's opinion.

Gloryann described her first hunt as a fantastic and most enjoyable experience. She was very impressed with the western hospitality and would advise any woman interested in hunting to take part, but that first she should enroll in a Hunter Safety class.

Gloryann, mother of four, is an avid subscriber to the belief that the success of a hunt is measured by the enjoyment of the experience. The actual taking of game can be enjoyed later as part of a favorite recipe, but is not an integral and necessary part of a successful hunt.

Yes gents, it seems that the appearance of a lady in the field may become a part of that previously mentioned mental recipe. I'm sure that the multi-colored landscapes of autumn, with all its varied scenery, will not be lessened with the change. Ω

NEBRASKAland

Adventures with Whiskers the prairie vole

Getting along in a civilized world can be quite a chore for wild animals. There are unnatural dangers lurking all about; ugly bulldozers, speeding cars and people spraying poisons

WHEW! That was close. You know, last month I was telling you how scary it was for great, great, great Grandpa vole living with all those mammoths and buffalo. Well, things are still pretty scary for us little prairie voles. Almost every day we have to run fast to get out of the way of you human beings. That guy running the bulldozer didn't even see my nest in the grass. Why, if I'd been a heavy sleeper, that tree would have fallen right on top of me.

In the old days, all we had to worry about was an occasional prairie fire or a hungry fox on the prowl. Nowadays it's a dangerous world. There are highways crisscrossing all over the place. Tractors come along and cut the grass where we live and sometimes they even plow it under. And as if all that weren't enough, this guy on the bulldozer pushes out all the trees around my country home along the Platte. That's about the last straw!

I guess I'm luckier than some, though. A lot of the animals that were around when great, great, great Grandpa was young just couldn't get along with you humans. Come to think of it, maybe it was the other way around. You human beings just couldn't get along with anyone else.

Take the black-footed ferret for example. They're big weasels with black masks like a raccoon. Ferrets were never as abundant as some animals, but they used to be all over Nebraska.

40Their main food is prairie dogs. Almost every prairie dog town had some ferrets and there were a lot of dog towns before you humans moved in.

You humans weren't around very many years before most of Nebraska was plowed and corn, wheat and milo planted. That meant that the prairie dogs, and we voles, too, had to pack up and move. There wasn't any grass to eat or any place to build a nest. When the prairie dogs moved, the ferrets had to move, too. NEBRASKAland

But there got to be more and more human beings to feed and ranchers had to raise more and more cattle on the grasslands. Prairie dogs were competing with the cattle for food and so they had to go. Almost all of the prairie dogs in Nebraska were poisoned.

There are still some prairie dog towns SEPTEMBER 1976 around. I've visited the one just north of the dam at Harlan County Reservoir and a couple of the towns on the National Forest near Halsey. My favorite prairie dog town is at the Fort Niobrara Wildlife Refuge near Valentine. Those Valentine prairie dogs are real friendly. Sure, they'll bark and stand up on their hind legs and whistle at you, but after awhile they just ignore you. Probably you won't see any ferrets in Nebraska, though. They're one of the rarest mammals in North America.

41

I get awful mad at some of you humans when I think about the black-footed ferrets and the prairie dogs. But, youVe done some good things, too. For a long time the pronghorn antelope was declining in numbers just like the prairie dogs. Two hundred years ago there were pronghorns all across Nebraska. Pioneers even saw them grazing on thistle, goldenrod and grasses down where the Platte River runs into the Missouri River. Imagine how surprised everyone would be to see a pronghorn where the town of Plattsmouth is today.

Those early pioneers killed almost every pronghorn in Nebraska. In 1920 there were fewer than 200 in the entire state. They started making a comeback, and then, about 20 years ago biologists from the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission caught over 1,000 pronghorns near the towns of Sidney and Harrison. They loaded them in trucks and released them in Nebraska's Sandhills. Today there are more than 10,000 antelope in the state.

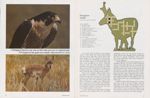

Just last Sunday great, great, great Grandpa vole and I were sitting in the sun munching SEPTEMBER 1976 wheatgrass seeds. He told about seeing peregrine falcons dive through the air at 200 miles per hour to capture shorebirds. That's about four times faster than when you're riding in a car on the highway.

I asked grandpa vole what happened to the peregrine falcons. He told me that peregrines nest in rocky bluffs like those by Crawford and Chadron. They're pretty secure there and man doesn't bother them. Many of the animals that the falcons eat have poisons in their bodies from the insecticides used to kill insects in gardens and farm crops. Sometimes the poisons kill the falcons directly, Often, though, the poisons make the shells of their eggs so thin that they break before the young peregrines can hatch out.

I'd like to talk a little longer but I've got to see what is left of my nest. Maybe I can still find some of the seeds I had stored for winter. Hopefully I'll be settled in someplace new by next month. If you live close to a library, try to find a book on trees. I'll see how many kinds you know the next time we meet. So long.

43

GUN DOG TRAINING

All Sporting Breeds

Each dog trained on both native game and pen-reared birds. Ducks for retrievers. All dogs worked individually. Field Champion-sired labrador pups for sale. Midwest's finest facilities. WILDERNESS KENNELS Henry Sader-Roca, Nb. (402)423-4212 68430THE LINCOLN TELEPHONE CO.

Every trip doesn't have to be a fishing trip Why spoil your fun searching for a pleasant place to stay? Phone ahead before you go.WILLOW LAKE FISH HATCHERY

STOCK YOUR LAKE OR POND with CHANNEL CAT LARGEMOUTH BASS BLUEGILL ORDER NOW Rt. 3, Box 46, Hastings, Nebr. 68901 Gaylord L. Crawford Phone-. (402)463-8611 Day or Night For spring or fall orders Pond Mill-Aquazine for algae-free waterMUTCHIE'S Johnson Lake RESORT

Upstairs Anchor Room Lounge Cold Beer-On/Off Sale Lakefront cabins with swimming beach Fishing tackle Boats & motors Free boat ramp Fishing Swimming Cafe and ice Boating & skiing Gas and oil 9-hole golf course just around the corner Live and frozen bait Pontoon, boat & motor rentals. WRITE FOR FREE BROCHURE or phone reservations 785-2298 Elwood, NebraskaHANK & AGG'S CABINS

Harlan County Reservoir Road No. 3 South of Dam Housekeeping and Sleeping Units Republican City, Nebraska Phone 308-799-2675 Fishermen and Hunters Welcome! Weekly and Daily Rates 44THE WALLEYE WAY

(Continued from page 11)through the lips and without the puff of air. Minnows are also dynamite when used in tandem with jigs, according to Roach. He proved that point fishing Branched Oak Lake as he tipped a white jig with rubber body and maribou tail (Lindy's Fuzzy Grub) with a crappie-sized minnow and put 50 plus walleye in the boat (only temporarily) during one very windy day.

Another live bait technique involves the use of leeches, a favorite walleye bait in Minnesota but one seldom used in Nebraska. Still another new idea is the use of salamanders, a bait deadly on lunker walleye in the spring.

Roach said that the food preference of walleye is minnows in the spring, nightcrawlers in the summer and fall.

The versatile Lindy approach involves not being afraid to move or try something different. When feeling out a new lake, Roach first consults a topographic map if available. He finds the likely bends in an old creek channel, rocky points, dropoffs, then makes these spots his starting points. Hell start out fishing shallow; trolling around the points in about 10 feet of water. If nothing, hell come back at 15 feet. If nothing, 20 feet, and so on.

If he hasn't hit fish by the time he reaches the end of the point or ridge, he'll pull up and try another spot.

At Branched Oak in April, Roach found the walleye in a post-spawn period. The females were not feeding but the males seemed starved. The fish were in one to four feet of water. Here was one instance when bank fishermen would have had a ball casting jigs tipped with minnows. Roach held his boat off the bank but within casting distance. At one point he and I put five fish in the boat with five casts. They ranged from VA to 5 pounds. We also caught a large number of yearling

Roach found the same technique successful at Harlan County and at Red Willow, both in post-spawn periods.

"These fish won't be up here like this very often, but when they are, after the spawning period, you can bet they're feeding heavily," Roach said. 'The fish will hit anything near them. It's almost like good crappie fishing, and for walleye, that's something."

Roach said the walleye is a fish that's really not too hard to figure. It has a regular movement that it follows year after year. In the spring, once the water temperatures near 40 degrees, the fish will begin heading toward their spawning areas. When done spawning, they'll spread out in the lake to rest for a week or two before regrouping in deeper-water hangouts about mid May through June.

Into July and August, fishermen could find the fish moving back into shallow-water weed beds, if a lake has a deep-water oxygen problem. "Walleye will head to timbered areas, like at Branched Oak, and lay in the shade," Roach said. "Or, they'll lay in weed beds, feeding at night in small openings in the weeds or along the edges. They'll be right in there with bass in cases like this, only a little deeper."

Then in the fall, the fish begin a slow migration toward more shallow haunts. "From what I understand, people don't fish much in the fall," Roach said of Nebraska "walleyers." 'They should be out there. That's when you can get into some of your best fishing of the year, particularly for big walleye."

The movement during various seasons always follows the bait fish, according to the Minnesota pro, who says you can't find walleye without finding bait fish.

During any season, however, the most important thing is to keep the bait on the bottom, according to Roach. "Walleye feed on or just off the bottom 90 per cent of the time, so it just stands to reason that's where you want to keep your bait."

The Lindy method makes use of open-faced reels and a medium or light-action rod. A heavy rod with fast tip also works well for rigging or for jigging. While back-trolling, the slip sinker should bounce across the bottom of the lake and the angler should have an open bail on his reel, a finger holding the line to detect a hit. After a little practice to determine which is a bottom bump and which is a fish bump, the angler will let the line loose for a fish, allow sufficient time for the fish to consume the bait, then reel in the slack and set the hook hard. A walleye has an extremely hard mouth, so setting the hook should be equivalent to the bass fishermen "crossing the fish's eyes" when plastic-worm fishing.

A complete booklet on fishing the Lindy system is available free by writing the Lindy/Little Joe Tackle Co., Route 8, Brainerd, Minn.

NEBRASKAlandThe 10-day tour of Nebraska also gave Roach some ideas as to how Nebraskans could do some good through regulation changes concerning the walleye and northern pike.

"First, I really enjoyed the talks I had with the Game and Parks Commission's biologists throughout the state, but I think they could benefit from some of the programs other states have implemented in attempts to improve their walleye fishing."

One of his thoughts concerned the possibility of a closed season during March and April to permit walleye and northern to spawn without harassment from fishermen lining the dams or the shallow-water grass areas (for northerns). Walleye along the dams will be in on the rocks, but the big females will be spooked off by fishermen from the bank and by boat traffic, according to Roach. Most of these fish, if constantly spooked, will refuse to spawn at all, thus lowering potential for fish in the future.

"Big females simply will not feed during this spawning period," he said. "About 90 percent of the big fish taken at this time of year will be snagged, netted or taken in some illegal manner, and that shouldn't be. The males will hit, but not the females. The same is true for northerns."

A suggestion, if the closed season is not acceptable to fishermen, is closure of a portion of ali of the dam facings on such lakes as Branched Oak and Harlan County, Roach indicated. This would allow at least some undisturbed spawning areas for the fish. Spawners have enough going against them, as bad weather can wipe out an entire spawn or panfish like crappie can eat up most of the spawn, and there are any number of other hazards. Good walleye states such as Minnesota and Wisconsin have closed seasons which tiave helped improve fishing success and production.

Another consideration Nebraskans might think about, according to Roach, is lowering the daily bag limits allowable on walleye and northern pike. Both limits in Nebraska are more generous than those of Minnesota, where fish and fishing are more prevalent. He suggests something like a six-daily walleye limit, and northern pike possibly only two or three.

"The reason you need to regulate for walleye and northern, especially in lakes like Branched Oak and Pawnee in the Salt Valley, is that you have tremendous fishing pressure," Roach said. "When you take out large numbers of walleye and northern, you allow crappie, bluegill and perch to increase beyond a controllable level. These fish will eat up all your little walleye, northerns and bass. Pretty soon you don't have anything but a very few big fish and lots of stunted bluegill, crappie and perch. That's no good. Lakes like Branched Oak should be getting a regular stocking of northerns to help control the bluegill in that lake. You see, when you put in northerns, walleye or bass, you also help the bluegill and crappie fishermen since their fish can get a lot bigger faster with more food available to them. They don't have to compete so hard as when you have too many panfish."

SEPTEMBER 1976 LAKE VIEW FISHING CAMP CABINS MODERN CAMPING MARINA Center-South Side Lake McConaughy Everything for the Fisherman Pontoon, Boat and Motor Rentals

Roach said Minnesota had some problems similar to those of Branched Oak in several small lakes in the Brainerd area, but fishing clubs formed to help stop the problem by encouraging stocking programs. He also found out Nebraska has such a club in the Lincoln-based Nebraska Trophy Fish Unlimited group, founded early this year.

"Clubs like this can get a lot accomplished," he said. "When a state doesn't have the manpower or the money, sometimes it takes the interested fishermen to get the job done. And if you don't act soon, some of these lakes around Lincoln will be in trouble."

But while Roach had some suggestions on how to make future fishing better through management techniques, he also had some ideas on the individual lakes. Here are his comments on each lake he fished.

Branched Oak LakeThis lake has a good walleye population despite the extreme fishing pressure. In early spring, after spawning, fish the lake's points, particularly where there are rocks. Minnows and Fuzzy Grubs are best bets, either casting toward shore, trolled or drift fished. Through May and June, switch to nightcrawlers deeper along these same points or along the roadbeds crossing the lake. Into late July and August, I think the fish move into the weed beds and back into the timber. It's tougher fishing then but they can be had. In the fall, the roadbeds and those same hard-bottom points will be good fishing.

Harlan County ReservoirThis is a tough lake to fish. In the spring, after the spawn, we found fish along the rock banks on the south side. I also assume the fish are running up the river right behind the white bass, although I didn't get a chance to try them. After the spawn, too, those big females move off and lay in a hole over the flooded old city. My thinking is they probably hold in this area, sifting down into the mud bottoms during July and August. If there is no oxygen problem In the lake, there should be some good fishing in the deeper water near the dam as well.

Lake MaloneyI believe the fish move into the canals to spawn in the spring, then move back into the lake through May and June. There is a good ridge running almost through the middle of the lake which should be extremely good fishing in the summer and into fall.

Red Willow ReservoirI like this lake. There is good structure in it, particularly one sunken island not far from the boat launch. That island should be good for summer walleye, largemouth and smallmouth fishing. Again, the post-spawn fish were found along the rock 46 banks, away from the dam area.

Lake McConaughyI'd love to guide on this lake. It has water that's probably never been fished; good deep-water dropoffs and rocky ledges all over. Almost any of these will hold walleye, trout, bass or stripers most of the spring, summer or fall. We found pne good area in Martin Bay which had a little cutback toward the bank with a hard bottom surrounded by sandy bottom, it dropped off from 15 to 25 feet and held big fish. We put together a stringer of 10 fish over 50 pounds and that's a good stringer in any state. The biggest trouble in fishing this lake is the wind. If you can get on the water, find a rocky underwater ledge; you'll catch fish.

Merritt ReservoirThis is one of the best bass-looking lakes I've seen in a long while. It reminds me of some of the Minnesota lakes I fish regularly. Here again the sand bars, preferably ones with rocks on them, will be the ones holding bass and walleye. In the spring, the bass and walleye will be in shallower water, the mouth of the (Snake) river and feeder creek. In the summer, they'll stick to the ridges and drops in the main lake and the river arm for the most part.

"There are a ton of walleye in this state and there are also a ton of fishermen who want to catch them," Roach said. "You can catch fish in any of your lakes in this state all year round. You've got some super fishing in Nebraska now but it can get better. As for the fishermen, get out there and do a little backtrolling or drift fishing along the points, rock island, roadbeds, creek channels and other pieces of structure and you'll improve your fishing."

Twelve years as a pro angler, fishing some 300 days each year, Gary Roach knows walleye fishing better than his own kids. Branched Oak, Harlan County, Red Willow, Maloney, Lake McConaughy, Merritt Reservoir. . . they're all good lakes ... and they're right in our back yard. Ω

BOW HUNTING BASICS

(Continued from page 36)will warp, and under most circumstances it is best if the arrow does not break off after a hit. Even fiberglass arrows will break off. I attribute finding one of my bucks to the fact that I was using aluminum arrows. The deer traveled over half a mile, even though I had a well-placed hit. The aluminum arrow had bent back and was still causing hemorrhaging as the buck ran. Had the bleeding stopped, I may not have been successful tracking the animal.