NEBRASKAland

July 1976

NEBRASKAland

VOL. 54/ NO. 7/JULY 1976 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Sixty cents per copy. Subscription rates $5 for one year, $9 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. commission Chairman: Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 Vice Chairman: Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-Central District, (308) 745-1694 2nd Vice Chairman: Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-central District, (308) 452-3800 H. B. "Tod" Kuntzelman, North Platte Southwest District, (308) 532-2982 Richard W. Nisley, Roca Southeast District, (402) 782-6850 Director: Willard R. Barbee Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, jr. Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: jon Farrar Greg Beaumont, Ken Bouc, Contributing Editors: Bob Grier Faye Musil, Tim Hergenrader, Roland Hoffmann, Bill Janssen, Ben Schole Art Director: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commision 1976. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska JULY 1976 Contents FEATURES FISHING AFTER DARK 8 PANHANDLE-SPECTACULAR IN ANY SEASON 10 WILD ABOUT BERRIES 18 THE BRONC, THE SAND LIZARD AND THE SUSAN SNOOKS 22 REDWING 24 BLUEGILLS BY THE POUND 30 WHITE PERCH BLUES 32 THE VIEW FROM BELOW 36 A QUESTION OF TREES 42 NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA/BISON 50 DEPARTMENTS SPEAKUP 4 TRADING POST 49 COVER: The redwinged blackbird is known across Nebraska by its raucous song and brilliant wing patches. For the story of nesting redwings, see page 24. Photo by Jon Farrar. OPPOSITE: The object of an extensive restoration project, these Canada geese are part of the population at Branched Oak Lake near Lincoln. Photo by Greg Beaumont. 3

Speak Up

How Nice Sir / Thank you so much for the January "Portrait of the Plains". My husband and I both grew up in western Nebraska and love it, so we are very happy to have that lovely book. How nice of you to publish that and send it to subscribers. Ruth Fingal Santa Cruz, Cal.

What's The Deal? Sir / I enjoy NEBRASKAland magazine very much, and my grandchildren also love the pictures. But, what is our Game Commission trying to do? Do you know how many people who are honest young people, working hard to make a living and raise a family, like to fish and hunt, and take their children with them for some good clean sport? Now all at once you need more money for wildlife, and I suppose, like our senators, vote yourselves another raise. I think personally our fees are high enough. If the Game Commission would spend the money from permit fees for what it was set up for, we could get a lot more done. We don't need all those fancy rest rooms along our freeways. We have cafes and gas stations all along the freeways that tourists can use. How about the $55,000 that Hastings received for a rest area. I think the money taken in from permits should be used for the people who buy permits. If you increase the fee as you have proposed, don't look for as many permits to be sold. I have talked with people and they say they can't afford to buy a permit at these proposals. I think you are cutting your own throat. I still love to take my grandchildren fishing, as I can't hunt anymore. Richard Smidt Juniata, Nebraska

Since your letter arrived, the Habitat Rill, LB861, passed the Legislature and was signed by the Governor. But, first let me stress that permit money is not used to build rest areas or the like. That money comes from the general fund, if in our 4 parks, or through the highway department. Also, community projects come about with federal and state funds, also separate from game funds. Money is spent for the intended purposes, it is just that there are far more purposes than money. Although permit costs seem high, they have risen far less than other items in the economy, while the management needs have increased tremendously due to lessening habitat. We need more and better public lands, or more access to private lands. Purchase and easements are possibilities, but they require more money, so hunters and fishermen must pay more. It is an unfortunate fact of life, and one of too few areas where the benefactors must pay their own way. (Editor)

Needs Bait Sir / Would anyone in your NEBRASKAland reading area have a recipe for "stinky bait" to use for catfish, which is homemade and which they would care to share with me or all your readers. I would appreciate it very much. Mrs. Alfred Buettner Grand Island, Nebraska

We also encourage readers to submit their recipes for bait, but I will include a couple that have worked for the originators. One merely calls for cutting up a fish, such as a shad or carp, in convenient chunks, putting them with water in a quart jar, then setting the jar in the sun to rot. Handling the bait is bad, but results are good. Another recipe combines Vi-gallon of chicken or beef blood, I tablespoon of brown sugar and 7 cup of corn starch. This is heated but not boiled, then alternate layers of it and newspaper poured in a box. After drying in the sun a while, the goop solidifies somewhat and can be refrigerated until use. The papers give it more strength. (Editor)If Shoe Fits Sir / Enclosed is copy of "Six Fishermen to Leave Ashore" which I thought could be passed along to other readers. Some of these items are true to life to any old experienced angler who has fished the waters of our great state. D. D. Maca Omaha, Nebr.

Six Fishermen to Leave Ashore

1. Noise-in-the-boat type. This guy sits quietly in the boat at dockside, but once you're fishing, he starts operating. He knocks over the minnow pail, throws oars against the boat, fusses loudly with tackle box. You don't get a bite as a result, but often HE catches a mess of fish.

2. Would-be caster. This fellow doesn't know how to cast, so of course he proceeds to practice. Leaves the clicker on when reeling in. He throws with sideways motion as companions duck in terror. The baited hook goes out about six feet, and while he is unsnarling an ugly backlash, he catches a beautiful northern pike.

3. Tonsil toaster. Lets both lines over the edge of the boat, sprawls comfortably over two seats, pushes hat over his face and goes to sleep, letting the sun peer into his gaping mouth. Doesn't catch any fish, but man, you ought to see the good strikes he gets and doesn't even know about.

4. Ye merry angler. Takes along a half-pint and six-pack in an ice chest, 12 cigars, seat cushion, portable radio, sandwiches and magazines. Almost forgets his tackle. Makes you go back to the dock because he forgot his can opener. Takes a half hour to unload all the junk in the boat and get the merry angler back into the car.

5. Rank amateur. Our wives fit nicely into this category. They go fishing once a season. After rowing out into the lake, she puts her line in the water, promptly catches a northern pike 28 inches long. After 10 minutes she observes, "Fishing doesn't seem to be any good today. Shall we go in?"

6. The mover. If you're fishing from shore, he disappears, reappears, explores and often goes away for half an hour, then shows up standing on the other side of the lake. If in a boat, he always suggests pulling up anchor and having you row him around the next bend, or back against the waves for half a mile.

Search Is On Sir / For the purpose of obtaining some historical and biographical information, we would very much like to get in contact with the descendents of Col. Frank Boyd O'Connell. He was, as you know, founder and editor of Outdoor Nebraska, a contributor to the Saturday Evening Post and other magazines, as well as the author of Farewell to the Farm. Any information you can give us as to names and addresses of Col. O'Connell's descendents and/or relatives would be greatly appreciated. Gene Gressley Univ. of Wyoming Conservation History and Research Laramie, Wyo. 82071 In hopes that some readers might know of someone, we hereby print your letter. Anyone having information is urged to contact the writer direct. (Editor) NEBRASKAland Magazine invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to Speak Up. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters. — Editor. NEBRASKAlandFree or at special prices CORNING WARE

for Mutual Saving Savers.

SURPLUS CENTER

- NATIONAL KNOWNN - WORLD FAMOUS -

OPTIMUS Lantern-Stove Propane Tank Outfit Regular Sale Price Items Purchased Separately, $79.62Relive Nebraska's colorful Past!

Stuhr Museum of the Prairie Pioneer

FISHING.... AFTER DARK

COME THE HOT days of summer, just about everyone and everything is figuring ways to beat the heat. Many fish, for example, switch over to the night shift and spend their daytime hours loafing in deep water.

So, it seems logical that a good way for a fisherman to score in the summer is to devote some extra effort to night fishing. Crappie, catfish and walleye prefer the dark hours all year long, but are particularly nocturnal when things get hot. And, some nice largemouth bass and white bass can sometimes be taken between sunset and sunrise.

Aside from the promise of hefty stringers, night fishing offers other rewards. There's relief from the burning sun and oppressive heat, as well as some refuge from the masses of boaters, water skiers and other fishermen that may crowd the lake during the day. And, the strong winds that often make daytime fishing impossible, or at least unpleasant, many times diminish after sundown.

But, probably the best reason of all to fish at night is time. Because, it is at night when most working folks have the opportunity to sneak in a few hours on the lake or river.

Night fishing's an altogether different sport than the daytime version, and it doesn't suit everyone. Besides its advantages, night angling also offers a few drawbacks. First and foremost, there are mosquitoes and a whole host of other buggy beings, all fully capable of driving anglers to distraction with their buzzing, biting and crawling.

There's also a lot of tangled lines, jammed reels, snagged baits and lures, and much frustrating time spent redgging in poor light. But, if you can take the bad with the good, night fishing rates a try.

Without a doubt, the most popular night-time fish in Nebraska is the crappie. As summer progresses, crappies head for deeper, cooler waters. Areas with sunken brush piles, flooded trees and the like in a respectable depth of water are the best crappie hangouts, and they are usually fairly easy to locate. Fifteen or 20 minutes over such a spot should tell whether or not it will produce. Don't be afraid to move on to another spot if things are slow.

Crappie tend to travel in small, loose-knit schools in the summer, so chances are that you may take only a handful in one particular spot before it's time to move on. However, that same spot might be visited by another group of crappie later in the evening, and produce more fish. Occasionally, one spot proves so desirable to crappie that a whole evening's fishing can be had right there.

On quiet, "buggy" evenings, it's sometimes possible to locate schools of crappie feeding on insects at the surface. (Continued on page 44)

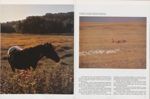

Panhandle Spectacular in any Season

THERE IS A GROWING realization that we require the solitude of quiet times; brief sojourns to simpler concepts. For many, these important moments are spent returning to the land, returning as visitors to our remaining natural areas.

The value of such moments lies deep in the natural systems that surround our visits to the land —natural systems that have somehow survived repeated clashes with time and progress. The wildlife, the vast stands of ponderosa and cedar, the bubbling rivulets moving noisily down uncounted watersheds toward the greater significance of the Platte; all of these and more can be found in the Panhandle.

Our love of this unique corner of the state is reflected by the great number of visitors it enthralls each year, each bringing something of himself to this place, and departing richer for the experience.

A growing number of enthusiasts visit this land outside the traditional summer vacation months. For them, the diversity and vitality of the seasonal transformations, the richness of the fall color, the subtle feelings of a quiet spring, outweigh the hardships imposed by inclement weather.

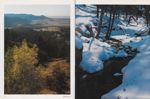

Winter grapples to dominate a snow-covered landscape and its residents, isolating the countryside for extended periods following blizzards. Trailing the heavy snow and high wind at a discreet distance, the sun returns.

The soft, fallen snow scintillates under its warmth. Blue shadows break the glare, but melting returns a bubbling rush to a freshly charged stream. Descriptive names mark these waterways. East and West Ash, Squaw Creek, Deadman's Creek, Warbonnet, the Little Beaver and Bordeaux — each moves like a life-giving artery through this rugged, pulsing land.

To the south, the Platte, powerful with freshly melted snow, cuts through the historic valley like a brawler, with little finesse or charm. The river knows well that the high waters cannot last, but is determined to begin the new year with this reminder of once-great importance.

In other seasons, visitors viewing its cracked stream bed may be hard-put to think of the Platte as a river at all. Elsewhere, spring returns clothed in the muted, peaceful pastels of new growth.

10

Snow becomes rain, and combined with the diminishing snow drifts, nourishes the landscape to new life. Spring rains are extremely valuable to this land; the moisture a blessing for all.

Occasionally, violent cloud maneuvering, heralded by rolling claps of thunder, escort the moisture to the land. Hiking through a landscape of rainsoaked pine during such storms is a rate experience to be often recalled.

Our leather boots quickly soak through, and the falling rain hinders vision. The fresh smell of damp pine fills the senses, and the thought of lightning searching for us with echoing clashes enters the mind from time to time.

Spring's pageantry of life continues even under such onslaughts. The regal turkey gobbler, his pride and power undiminished even in the face of cooling rain, answers each rolling blast of thunder with a defiant gobble.

Moving close to observe, we see small but freshly scratched beds in pine needles, and hear only the "perk-perk" call of alarm. Outwitted again, we move on through the drenching downpour.

The storm clears the air and sets the stage for a multicolored sunset, its peacefulness made the more memorable by the passing storm's violence.

The dawn's light slices through the mists rising from the

Platte, and the quiet, golden illumination bounces from

shadow to shadow. Trees leaf out with green finery, and

13

summer ushers in with warm, soft breezes. The high winds

of spring are easily forgotten, although the hearty gusts seem

to be as much of this place as the land.

summer ushers in with warm, soft breezes. The high winds

of spring are easily forgotten, although the hearty gusts seem

to be as much of this place as the land.

Summer is a time of puffy clouds wafting above vast stretches of prairie. On the Oglala National Grassland, the greyed wood of man's earlier hopes to settle this land stand as witness to the changing cycles, watching with empty windows once curtained by some eastern lady's hope and handiwork.

Life continues around the abandoned buildings. The antelope move by as they have for thousands of years. The prairie dogs continue to tunnel, and occasionally the rattlesnake issues his warning. Little has changed in this place since early settlers moved before the hostility of the land, leaving silent once again vast stretches.

The warmth that started the growth now quickly burns the moisture from the ground. Grass goes from green to golden tan, and the earth cracks under the dry heat. Soon fall's reprieve and the first moisture of winter start again the continuing cycle. To witness the changes, to experience the eloquent statements time writes on this place, is to renew again our closeness, our life-sustaining ties to the land. Ω

WILD ABOUT BERRIES

Many stands of native fruits and berries remain and others are coming back, but they should be actively encouraged Planting in roadsides and fencerows will spread bounty

18 NEBRASKAlandPERHAPS MOST of us have a certain amount of the "Johnny Appleseed" syndrome, with impulses to dash about the countryside planting our favorite trees or bushes in order to improve or capitalize on Mother Nature. Whatever the reason, I admit to being a nut for nuts, fruits and berries and would like to see country roads and other barren or accessible areas thrive with such worthwhile growth rather than sneaky weeds or pompous brome.

It seems so logical that waste areas such as uncultivated plots and roadsides be adorned with thriving stands of useful plants —both for wildlife and humans —rather than continuing to be waste areas. Besides, there is considerable satisfaction and economic benefit to picking and processing one's own berries for jelly, syrup, wine or eating fresh.

Such endeavors have never died out totally, as since pioneer times some people have taken advantage of wild foods, including the much-sought-after mushrooms and the like. However, vast stands of these wild fruits and berries have disappeared due to spraying, agricultural intensification and urban expansion. There is still ample room for them, if they could only be started in appropriate sites.

Even now there may be wild crops going unused merely because people don't know they are available, and don't know how to utilize them. Others are extensively used, such as plums, but many more people should avail themselves of these fantastic fruits. Few if any fruits can rival the wild plum for jelly or syrup. The chokecherry is a close competitor, then many others follow. Elderberries grow in profusion in some areas, and only a few local areas are harvested. It just seems that many more people would take advantage of wild crops if they were more abundant, as demand would certainly keep close pace with supply. Thus, if more plots of these magnificent plants could be started, and preserved from destruction by spraying, it would be extremely beneficial. Those that people did not pick would still go to good use by birds and other critters that appreciate such things.

JULY 1976Although most cook books include recipes for processing the more common varieties, I have found the most help with the liquid type commercial pectin. Enclosed with this product is a full, detailed list of fruits and directions for working with them. Also, some types of berries cannot be processed

Many factors are involved in harvesting wild fruits and berries, not the least of which is locating them. Of course it is also necessary to recognize them, and to know when to look for the various types.

Mulberries are among the first to ripen, and are also very common in many parts of the state. It is along about the middle to third week of June when they normally are ready to pick, but the time can vary somewhat depending upon the weather and part of state. Mulberries grow on trees, rather than bushes, and are more difficult to pick for that reason. One way to get a large number of them is to spread blankets or plastic sheeting on the ground under the tree, then rattle the branches rather ambitiously. On younger trees, it is possible to reach most of them, and they can be hand picked.

There is a white mulberry, but the dark red is the most common. Although leaf shape varies, they normally appear as three-lobed, light green, and small. The fruit can appear singly along the branches, or in clumps at the base of the leaves. Mulberries are extensively used by birds, as most car owners can attest at that time of year, and also will be utilized by carp if branches overhang appropriate water. While rather bland as wild berries go, they are pleasant tasting, abundant and easily processed for wine and pies, or can be mixed with sour cherries or rhubarb to add a tangy zip. Wild strawberries are available at about the same time as mulberries, but virtually everyone can recognize them due to their similarity to tame varieties. Only size of the fruit and leaves differs.

Shortly after, from late June to mid July, come the raspberries, and again, they appear the same as tame types, with tall, limber stalks heavily armed with thorns. Raspberries are perhaps most often eaten raw and unprocessed.

July is actually the most active month for wild berry pickers, as a great number of species ripen then. One of the most interesting and fantastic is the chokecherry. While containing a relatively large seed or pit for its overall size, the chokecherry is a favorite for jelly and syrup. Normally a medium-height bush found along country roads, they bear fruits that

turn a dark purple, almost black, when

ripe, and are easily picked by the

bucket. The fruits are about 3/a-inch

in diameter and grow on short stems

off the main branches. When ripe,

they can be stripped directly off the

stems into a container without any

muss or fuss.

turn a dark purple, almost black, when

ripe, and are easily picked by the

bucket. The fruits are about 3/a-inch

in diameter and grow on short stems

off the main branches. When ripe,

they can be stripped directly off the

stems into a container without any

muss or fuss.

The tart, delicious berries have been used for virtually every use possible, from eating fresh to pies and jelly and syrup and wine. And, they excel at each. They are a true bounty as a native fruit, and are utilized extensively by humans and animals.

As with most native species, the advent of spraying various chemicals along the state's roadsides wiped out vast stands of them, and doubtless poisoned many birds and other users who were unable to wash the berries. Since chemicals have become more expensive and spraying curtailed, these bushes are making a comeback, and it can only be hoped it continues. They are attractive bushes, being symmetrical with dark foilage. When loaded with purple berries, they are very special indeed.

In those areas where available, the wild currant, sand cherry and gooseberry are ripe at the same time as chokecherries, and are extensively

Sand cherries are large, sweet fruits which grow on short, sparse plants about one or two feet high. They are delicious, being so similar to bing cherries that they could be mistaken for them. The bush is found primarily in the northern Sand Hills area, although formerly they were found nearly statewide. Even in the hills they are disappearing, and that is truly unfortunate. The fruit is best utilized raw.

Currants and gooseberries are so similar in appearance that some references consider them the same plant. Both have smooth and prickly varieties, although the wild types usually have spines on the branches. Often, the light green unripe and purple ripe fruits are mixed for jelly, although that is a little awkward when all fruits ripen about the same time.

Gooseberries make excellent jelly and wine, but are difficult to harvest because of the thorns. The bushes are low, normally about three feet high, and rounded, but with long branches. The unripe berries are unique with almost a transparent, light green skin with definite stripes. Leaves are small, three-lobed and light green, resembling mulberry. Although difficult to pick, they are worthwhile. For wine, unripe or green fruit is preferred.

Late July to early August is the time to seek out blackberries, although they are not as common in Nebraska as compared to western states. They grow well here except during extreme winters, and some planting is done. Wild blackberries are also extremely thorny, requiring gloves and long sleeves for picking the fruits, which resemble raspberries except for the dark, purple-black color. Very popular for jelly and also for wine.

Buffalo berries also begin ripening in late July, but their season extends later, into early September. Found primarily in the northwest part of the state, the fruit is about the same size as a gooseberry and is very acid until after frost, when it is much sweeter. The fruit is bright red, and grows on shrubs normally about five or six feet

Next on the outdoor menu is the elderberry, often the most abundant fruit in a wide area. They are distinctive in that the berries form in large, circular masses often the size of a dinner plate. As they grow heavier, they droop and weigh the branches down. In prime growing conditions, a bush only five or six feet high may produce several pounds of the smallish, pea-sized berries.

Elderberries are easy to harvest, as the entire heads with stems may be NEBRASKAland cut off. Later, when processing, the berries can be stripped off. For wine making, the berries are normally left on the smaller stems, which saves considerable time.

Due to their flavor, which is strong but neither tart or sweet, elderberries are commonly mixed with other varieties or have acid added for perfectly clear, dark purple jelly. Another use, although not yet common, is to use elderberries in place of blueberries in muffins. They are excellent, and freezing them beforehand tends to make the seeds unnoticeable. They are also tremendous when made into a cream pie, and with or without additional acid, produce a fine, clear wine of heavy body.

Although late August to early October doesn't find many fruits remaining, certainly some of the best are saved for last. The wild grape is ready at that time, and in fact the flavor is improved after a light frost. Grapes need very little promoting as they have long been favored.

Another very special, and perhaps the most outstanding of the entire array of wild fruits, is the native plum. Formerly common almost throughout the state, the plum has suffered much persecution during road widening and brush clearing. The bushes are very valuable for wildlife habitat, however, and the fruit alone makes this native fruit the top nomination if there is a fruit of the year contest.

While it is troublesome for wine making because of haze, it makes absolutely fantastic jelly and syrup, and its other uses are likewise delightful.

Plums are large, averaging over an inch long, and are found in both red and yellow varieties. The red are most common, and also have slightly more flavor. They ripen slowly, starting to turn color in July and early August, but are not ready for harvesting until normally late August with a peak in mid September. Often, the fallen fruit is the best, as these will be fully ripe and plentiful. The bushes, averaging five or six feet high, are rather prickly and awkward to work in, but gathering fallen fruit is much easier and faster. A bucket of plums will go a long way as they contain much delicious pulp, but with all wild fruit, each picker will have to determine JULY 1976

It is best to not overpick, as the anticipation of the next season is then much greater, and people are encouraged to get out and enjoy a little bit of nature —in fact a mighty fine bit of nature.

And, speaking of nature, we get back to the Johnny Appleseed syndrome. There is certainly nothing wrong with giving nature a hand in proliferating native fruits and berries, so if you have a few prize seeds, or a batch of them left over from wine making or other use which does not require cooking or otherwise destroying the seeds, see that they get planted where they will do some good. Plant them in roadsides where birds, animals and people can eventually make use of them. They are so much nicer than weeds, and in fact will keep weeds from growing there. And, they can mean an ever-expanding source of wild produce, and probably will help encourage other people to benefit from them. Ω

20

the BRONC, the SAND LIZARD and the SUSAN SNOOKS

Across the Sand Hills and to Yellowstone was goal of this young girl and three old cars

ABOUT 8 A.M. WE started for the park. The auto was so loaded that you could hardly tell what it was. I sat in the front seat with the chauffeur (my Papa). A large comforter made the seat so high I could hardly stay in, and I could not possibly hold on as I had field glasses in one hand and a camera in the other.

"The back seat was so full that Mamma, Honor and Roy could hardly get in. We went first to the Burwell lumber yard where we found that our auto, the Susan Snooks, weighed 710 pounds on their scales."

Thus begins a story of fun and adventure in 1913 as three touring cars, looking much like buggies with motors where the horses should be, set out through the Sand Hills of central Nebraska for Yellowstone Park.

At the present time when there is great interest in restoring old cars and enjoying trips in them, I found this story of an original trip exciting.

It was penciled on yellowed sheets of tablet paper in my mother's fancy handwriting. Besse Cram was 15 when she wrote it, and full of vim and vigor. But I'll let her tell it.

"Mr. Butler drove up in their auto, which they christened the Bronc, with his family of five. Then the Coffins completed our party in the Sand Lizard with their five.

"The Bronc took the lead and after Forks Hall we went through sand for about half a mile and then crossed the Calamus bridge.

"About half past one we ate a picnic dinner near Duff. There was a bad sandy place about four miles from Duff and we had to go back and push the Sand Lizard up the hill.

"About 4:30 we reached Long Pine which is about 68 miles from Burwell. A storekeeper there told us there was 22 a fine camping place down in the canyon so the Bronc started on. Couldn't find it. The road was being fixed so most of us got out to walk uphill as it didn't look very far. When we got to the top of the first incline we stopped in dismay; another long, crooked, steep hill extended in front of us. When the top was finally reached, we nearly fell into the cars, but from there on the roads were grand.

"At Ainsworth they again told us to go on a little way and we would come to a good camp. We went the required distance but the camping place was not visible so we went on. A terrible wind storm came up but we outran the rain and came to Johnstown.

"We were as hungry as bears by this time and what luck! All over the sidewalk were signs with "Chicken Pie Supper" written on them. We ran around trying to find it, but had to be satisfied by walking over the signs as it had happened a week before.

"About three miles out the Susan Snooks suddenly ran into a beautiful little canyon and was so struck with wonder that we stopped and made our first camp on the spot.

"If you have ever camped in an auto before you will probably be interested in hearing about ours. The Bronc ran up beside some chokecherry bushes. The Sand Lizard and the Susan Snooks followed. The ladies went up a hill to a house to ask if we might camp there. They were told that they could if they would promise not to take any chokecherries.

"In the meanwhile the men built a campfire by digging a hole in the ground, filling it with dry twigs and putting a grate over the hole. We kids went down to the creek and washed and got a drink.

"When we got back, supper was ready. It was hurriedly eaten and then I got out the side curtains and Papa the canvas. On the side away from the bushes, I put up the curtains, then went to help the chauffeur. He had the canvas unfolded and ropes, tied into some loops in one end, which he threw over the top of the auto to me. I put up the windshield while he fastened down the sides of the canvas. We then went to bed but were aroused about four by a noise. Peeking under the canvas, I saw Mr. Butler making a fire. It was very cold so I got up and dressed as quickly as possible.

"About 8 we started for Wood Lake, but some distance after leaving it many roads led off from the main one. Suddenly the road ended in a farmer's yard. Taking the farmer's directions we bumped across a swampy pasture with the prettiest, fattest horses in it I ever saw, but we ended up blocked by a creek. We kids went in the water though it was muddy. We saw dilapidated farm buildings and when we got to them they turned out to be deserted. Then we started on another road which ended up in a small pasture. We did not know what to do.

"The railroad track was built up higher than our heads on one side, and the road we had come over was on the other side. I took the field glasses and went up on the track but could see no road or anything else but sand hills.

"About noon we heard a threshing machine over the hills and Mr. Butler went to find it. When he got back he said that we were to go down the track and find the road, but a man came on horseback before we started and showed us a better road. We had gone but a little ways when we came to the (Continued on page 47)

NEBRASKAland

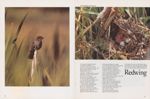

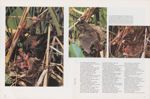

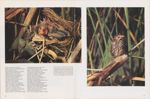

Redwing

Twin Lakes just west of Lincoln is a refuge for wildlife. It is closed to hunting and to public access during waterfowl seasons. The drone of power boats has never reverberated across its 270 acres of water. It is a sanctuary, a storehouse that annually replenishes the sky and land with wild animals and plants for hunters and nonhunters alike. For the redwinged blackbird, its cattail marshes provide nest sites and unlimited food for naked, gawking clutches of young.

During March, spiraling flocks of male redwings descend into the marsh. In the days that follow, the cooperation required for those precicion flights dwindles as individual males claim and aggressively defend their territories with song and display. A month or more wili pass before adult females arrive. At first they may be driven away by belligerent males but eventually they are accepted into a territory. A frenzy spreads over the marsh as more and more females arrive. Males hover overhead and release their pent-up passion with scolding song, quivering wings and flaming shoulders from the highest of last season's cattails. The females seem unconcerned and occupy their days walking about on the broken-down marsh plants in search of food. It may be a week or two before actual mating takes place. During late April and early May, when the new cattails are nearly full grown, the female redwings begin to build their basket nests.

25

Each redwing nest is distinctive, varying with the location and materials used, but each follows a construction plan dictated by some innate sense. Generally there is an outer basket woven snugly into the supporting cattails or rushes. The basket is lined with mud and then an inner liner of softer material is added. For six days or more the female redwing works at the task while the male occupies the highest perch in his territory, fluffing each feather until he appears twice his size, and calling challenges to intruders.

Immediately following the completion of the nest, the female will begin laying eggs, three or four composing an average clutch. Only 11 days after she begins incubating, the first egg may pip and in just minutes the near-naked young forces its way from the blueish egg and sprawls helpless in the nest. The chicks are orange at hatching, with gray-violet skin stretched over the bulbous eyes. They are scantily covered with a grayish down.

Before their down has thoroughly dried the awkward young redwings are offered their first meal of insects. Mayflies, beetles, assorted worms and the catterpillars of moths or butterflies are the usual fare. The most aggressive chick, the one that can raise its gaping maw highest above the bowl of the nest, receives the lion's share of the food. Fortunately, a full stomach satiates even the most greedy appetite and each chick in turn receives its fill. The insect supply is abundant during June and the female may make 20 or more trips during a 5-minute period, returning each time with a bill packed full of twisting, squirming food. When feeding, the adult thrusts its bill far down the young's throat to prevent any of the live insects from escaping.

After each feeding the nest is meticulously inspected and the membrane-enclosed feces of the young removed. Likewise, the female carries egg shells away from the nest site so as not to attract predators.

On the protein rich diet of insects, the chicks grow perceptively by the hour. On their second day the blue "pinfeathers", that are destined to become the primary wing feathers, show prominently. On the sixth day the feathers of the wing have emerged from their sheaths and the body feathers begin to show the following day. The female is forced to spend most of the daylight hours searching the marsh for food, now.

27

By the ninth day, the redwing-chicks are nearly covered with feathers except around the eyes. Nest sanitation has become a serious problem in spite of the female's valiant efforts. The young are capable of short, frantic flights and will leave the nest if threatened. When just 10 days old the strongest redwing chicks leave the nest and climb on nearby vegetation. In the days that follow, the chicks learn to capture insects and begin to strengthen their wings. The female continues to bring food to the young but more irregularly. By late July and into August, the young birds will resemble the drab, streaked female and begin to gather in large migration flocks. 28 Ornithologists generally agree that a few redwings bring off two broods a year. Some have even reported three successful hatches in one nesting season. With such explosive reproductive potential, it becomes obvious that redwings must also be victims of a rather high mortality rate, less the world soon be blanketed with blackbirds. In years past, blackbirds descended on ripe grainfields in such numbers that landowners would habitually burn entire marshes during the nesting season in hope of slowing the depredation. During the early 1900's redwings were offered for sale in posh Eastern markets under the name of "reed-birds" Today, they offer little threat; only a raucous song and a lesson in living.

BLUEGILLS BY THE POUND

Nearly hand-over-hand they came in, after a storm moved and lake calmed

SPRING HAD ALREADY a fine start on summer in the Sand Hills, and judging from the number of Master Angler Award applications arriving almost daily at the Game and Parks Commission's district office in Alliance, fishing was improving with the weather.

A routine sorting of the day's arrival of Master Angler applications served as my introduction to the fine bluegill fishing at Smith Lake, and a great family of Alliance anglers, the Gordon and Roger Goldens.

Gordon, his son Roger, and Roger's children make for three generations of enthusiastic anglers.

I had taken up residence in the fast growing Panhandle community only recently, but had already visited nearby Smith Lake on several occasions. The fortunate visit of the Golden family to the office to weigh several large bluegill for Master Angler awards gave me the opportunity to ask about fishing methods and techniques for the large, one-pound-plus bluegill.

Our conversation about Smith Lake ended with an invitation to join the Goldens' next trip to the sandhill-surrounded lake.

Smith Lake is in Sheridap County about 23 miles south of Rushville and 25 miles north of Lakeside. The lake covers approximately 222 acres and was formed in 1949 when an outlet control structure and dam were laced on Pine Creek. The lake and surrounding 418 acres of land is classified as a state special use area, and is maintained for public hunting and fishing.

The lake offered excellent fishing until an extreme winter kill occurred in 1968. Netting by biologists the following spring indicated that crappie, largemouth bass, bluegill and channel catfish were completely eliminated, leaving black bullheads and few other fish. The lake was drawn down after the winter kill to facilitate renovation aimed at preventing a bullhead takeover, and restocking began in April of 1969.

Roger and Gordon were right on schedule, arriving while I was still trying to sort a usable combination of fishing equipment from several boxes still unpacked after my transfer to Alliance. Settling on a closed-face spinning reel and a rod that I'd previously given my oldest boy for his birthday, we loaded my gear into the trunk of Gordon's car and were soon moving east through the sandhills.

Bouncing over the one-lane oil road north of Lakeside with the boat and trailer in tow, it was quickly evident that the main problem with fishing at Smith Lake was the driving distance from Alliance, or any other Panhandle community.

The idea that the distance presented too great a deterrent was completely shot down when Roger talked of fishing and camping at Smith Lake without the overrun, packed-in feeling that many of the more popular fishing areas have become known for.

"We would camp out at Smith Lake and really catch some nice bullhead in the spring," Roger said. "It seemed that when the water got to about 35 degrees, the bullhead, and there are some nice ones in there, really started biting!"

I mentioned one of the fisheries biologist's work with the bullhead population in Smith. Walt Meyers of the Alliance office found an amazing number of large

"The funny thing about bullhead fishing at Smith," Gordon added, "is that the bullhead will only bite iate at night, sometimes waiting until after midnight to really get going."

The conversation quickly turned to other fish species found in Smith, including our main quarry on the trip. Roger detailed the spring and early summer schedule, starting with bass fishing early in the year.

"In April we catch good bass, fishing along the bank with small spinner baits and other artificials. As NEBRASKAland the water warms up, usually in May, we begin catching bluegill. June is the best month for bluegill, but it continues until the middle or later part of July."

A rain squall several miles to the north threatened to prevent an extended stay on the lake, and a building wind was kicking up choppy, dark green waves as we loaded into the boat. The youngsters had put on their life jackets even before climbing into the boat. On board were Roger, Gordon and me, young Joe and his sister Tammy, 11, and Gordon's wife Eleanor.

While moving south from the boat dock, Roger mentioned several areas that had been good bluegill producers. Several bank fishermen and two other^boats were the only ones on the lake. Everyone we passed reported little success, with a consensus expressed that the weather appeared to be the reason for the slack fishing action.

As we neared the Golden's favorite fishing spot, Gordon checked the water depth with the anchor rope several times, and finally motioned for Roger to kill the motor. Two anchors were used to hold us in correct position to al low everyonean equal chance at the hotspot.

Nightcrawlers baited on a single hook, everyone using only a l/2-inch portion of worm, was the technique. The small amount of worm had worked well in the past and really "stretched" the bait. A small bobber was placed about two feet above the bait.

The rolling, choppy waves made it difficult to determine exactly when the bluegill were biting, and in general, the action was spotty. Only a few bluegill were landed, and most were small.

Rain arrived, along with gusty winds, as a typical Sand Hills rain squall moved over the lake. Roger guided the boat to the dock through the peppering droplets and everyone piled into the vehicle to enjoy a storm-prompted lunch. Sandwiches and steaming mugs of coffee accompanied stories of fish and fishermen. Young Joe told of the time he'd caught two bullhead at Smith, each only two ounces under two pounds, at the same time on one fishing pole.

"We didn't know what he had," Roger added. "The pole was really bending, but the fish didn't fight like anything we had caught before in Smith Lake. Finally we saw that Joe had caught two nice bullhead, and we left for town shortly after he landed them to have the fish weighed for Master Angler awards, which they just missed by two ounces."

Joe's grandfather, Gordon, entered into the conversation and described pulling a good-natured joke on several Smith fishermen; taking advantage of the natural tendency of anglers to head for a spot where someone had reportedly taken large fish, or a limit.

"Roger and I had fished bullhead most of the night, and after the sun came up, the action stopped almost completely. We drove down to a section of nearby Pine Creek, where we caught our limit of brown trout. Back at the lake, the other fishermen asked where we'd caught the trout. Roger and I had everyone down to the lake's outlet in no time, beating the water to a froth in an effort to catch brown trout."

Again, as if on schedule, the dark rain clouds moved south from Smith, and a bright, warming sun exposed JULY 1976 everything covered with drops of water; crisp and green under a mantle of sparkling jewels.

Moving once again to the yet unproven hotspot, everyone rebaited their hooks and positioned bobbers.

This time, however, the bluegill cooperated, and it was scon apparent that a post-storm feeding spree was underway. Tammy caught the first pound-plus bluegill of the day, a feisty, hard-fighting fish that appeared as round as a dinner plate when the youngster expertly brought the fish into the boat.

The action came fast, and a number of good-size bluegill, several weighing better than a pound, quickly found their way into the holding baskets.

The distance between bait and bobber appeared to be a critical factor in the success of each angler, and I noticed that Roger continually moved the bobber on his line until several hefty 'gills signaled that everything was right.

Long strands of water vegetation also plagued this type of bluegill fishing, and everyone had to reel in often to clean the line. Any break in fishing action indicated that the line had become fouled with vegetation.

"In July, sometimes earlier, the thick water plants almost completely close Smith to fishing access," Roger said. "The vegetation starts building along the bank first, blocking off bank fishermen."

To the north of our boat, several anglers had overcome the high bulrush and cattail growth near the bank by using a harness and innertube to float along, casting toward fhe bank.

The floater appeared to be a useful device for the shallow water, and several of the fishermen using them were catching bluegill as they moved along the shoreline.

Back on the boat, the fish baskets were quickly filling with bluegill when Joe gave a startled yell as his fishing rod bent dangerously close to the breaking point.

"That's no bluegill," Roger shouted as everyone in the boat quickly reeled in to prevent Joe's fish from tangling the other lines.

The fish was putting up quite a battle, but it appeared that Joe had the upper hand as he pulled on the rod and reeled in as he moved the rod down. Approaching the surface near the side of the boat, the big fish gave everyone a glimpse of his mottled green torpedo shape. Thereon the end of Joe's line was a large northern pike, clenched tenaciously to the back half of a large bluegill that had taken Joe's bait. The pike appeared to be nearly three feet in length.

Roger cautioned Joe to keep from forcing the fish, but as suddenly as the pike had hit Joe's bluegill, the line went slack, a mauled bluegill still well hooked at the end of the line.

The bluegill feeding spree was quickly slowing down as we brought in the anchors, placed the loaded fish baskets in the boat and moved north to the boat ramp and dock.

All told, we had 53 keeper bluegill, 6 weighing over the 1-pound Master Angler mark. With the passing of the brief rain squall, Smith Lake had become a real bluegill producer; a worthy and gratifying challenge for the angler interested in catching skillet-size bluegill during an enjoyable Sand Hills outing. Ω

31

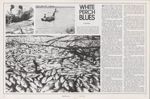

WHITE PERCH BLUES

A SMALL, SILVERY fish arrived in the Salt Valley a dozen years ago, and he managed to stay in the background for quite a time before anyone paid much attention to him. But last year, and again later this summer, this fish and efforts to manage him will greatly affect many fishermen in the area and, hopefully, it will benefit all Salt Valley anglers in the long run.

That seemingly insignificant little critter is the White perch, and the management effort directed at him is simple in concept though tough to accomplish —extermination.

The decision to eliminate this fish was not made lightly. When Game and Parks Commission fisheries biologists became aware of the problems the white perch were causing, and the potential he offered for future trouble, a comprehensive study was initiated that took nearly three years. When the data was tabulated, the answer was clear: the white perch must go.

The white perch's visit to the Salt Valley is turning into an expensive one for the area's fishermen. The price has been several years of reduced fishing potential from Wagon Train and Stagecoach lakes, followed by two years of absolutely no fishing at all from each of these impoundments. In addition, some $70,000 in fishing license revenues will be expended on the problem.

This all seems like a heap of trouble to be caused by some tiny fish, especially fish that are thought of as good panfish in other parts of the country. But, the fact is that the white perch overpopulated Wagon Train and Stagecoach lakes to such an extent that desirable fish couldn't get along there.

The white perch caused all of this trouble because of its extreme fertility, a characteristic that is necessary in its native tidal waters along the Atlantic coast. Life is tough there, and a species of small fish must produce many individuals if a few are to survive to adulthood.

But, in small inland waters like the Salt Valley lakes, such a high rate of reproduction soon outstrips that of the native species. A two-year-old female white perch taken from Wagon Train Lake would have an average of 167,000 eggs, and some carried as many as 460,000. Compare that to the native bluegill female, capable of JULY 1976 producing 5,000 eggs, at most, at two years of age. Compounding the problem is a little-understood phenomenon in which Salt Valley white perch mature at one year of age instead of the usual three years in native waters, and bring off about 6,000 eggs that first year.

You don't have to be much of a mathematician to figure that white perch would soon dominate a lake by virtue of this numbers game. It would take a year or two for that to happen, and during that time, there would be enough food to go around to allow some of the perch to reach 10 inches or so. They might interest a panfisherman, if he could figure a way to catch them.

But after a while, there are so many white perch mouths to feed that there is not enough food to enable any of them to get much over five or six inches. And, the same aquatic insects that they eat are needed by young channel catfish and largemouth bass during their first year, and by bluegill throughout their lives. It is obvious that good sportfishing is not possible under such conditions.

The white perch even appear useless as forage for the predator fish already in the lake. Stomach samples taken at Stagecoach Lake showed that only 3 of 90 largemouth bass and none of the 58 crappie sampled, had eaten white perch.

The aquatic insects gobbled by hordes of white perch are needed by bluegill, which do supply forage for game fish when young and sport to panfishermen when grown. And, this food is needed to sustain young large-mouth bass until they are old enough to hunt larger prey. And, this same food supply gets young catfish off to a good start. But with white perch overpopulation, the basic food stock of the lake is short-circuited to production of a fish useless to fishermen and nearly so to predator fish.

Besides white perch, other problem fish also plague this part of the Salt Valley system. Gizzard shad are also present in very large numbers, and they are equally worthless to fishermen while constituting yet another drain on the food supply. Carp were also present in Wagon Train.

The cost of the invasion of undesirable fish in these lakes has been high,

but the first payments have already

been made and the last installments

33

are hopefully in sight. Wagon Train

Lake was renovated last year with fish-killing chemicals and restocked with

game fish. And in mid-July and early

August this year, fisheries personnel

will be doing the same thing to Stagecoach Lake.

are hopefully in sight. Wagon Train

Lake was renovated last year with fish-killing chemicals and restocked with

game fish. And in mid-July and early

August this year, fisheries personnel

will be doing the same thing to Stagecoach Lake.

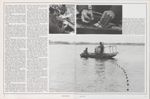

Such operations are expensive and involve a lot of planning and hard work. Except for an earlier starting date, this year's renovation of Stagecoach Lake will be almost a carbon copy of last year's Wagon Train project.

Landowners with farm ponds in the watershed above the lake must be contacted for permission to check their waters. Those where potentially harmful fish, such as bullheads, carp or white perch are found, will be renovated with the landowner's permission. The ponds capable of supporting them will later be restocked with game fish.

With cooperation of the Corps of Engineers, the outlet structure at the dam will be opened to partially drain the lake, minimizing the amount of expensive chemical needed. Barring significant rainfall and runoff, the lake will be reduced from 2,000 to 500 acre-feet in about 19 days.

Before chemical is applied, an attempt will be made to salvage as many game fish as possible for transfer to Hedgefield Lake just Vh miles to the east. This year, trap nets and shocking equipment mounted on boats will be used to gather walleye, catfish and bass when they are concentrated on known spawning areas, and again when the lake is drawn down. Before the Wagon Train renovation last year, a huge seine was used to salvage fish, but the operation was expensive and results were disappointing.

Hopefully, in mid-August, draw-down will be complete and fisheries personnel will be able to apply some 315 gallons of chemical, in this case, rotenone. On the main part of the lake, the fish toxicant will be pumped from boats into the water, while shallows, flooded timber and other hard-to-reach places will be sprayed from a helicopter.

After the rotenone has been applied to the lake, attention will be turned to Salt Creek and its tributaries above and below the lake. Because of a good catfish population, the creek will be treated with antimycin, a chemical 34 that kills scaled fish like white perch, carp and shad much easier than it does non-scaled fish.

Treatment of the creek will probably not completely eliminate white perch from the watershed, but it will cut the population back considerably. Winter will do more to reduce their numbers, since they are rather delicate. By next spring, they could be nearly eliminated from the Salt Valley and prospects for their return would be slim, since they do not appear to reproduce in the creek.

In early fall, after the rotenone wears off, Stagecoach will be restocked with nearly 200,000 large-mouth bass, bluegill, redear sunfish and channel catfish, plus a quantity of fathead minnows and crayfish for forage. The next three years will see more bass and catfish introduced, plus walleye and northern pike.

It will not be long before fishing returns to that corner of the Salt Valley. Wagon Train, the lake treated last summer, will open to fishing on January 1 of 1977. And Stagecoach, a very fertile and productive body of water, should be turning out legal-size bass by the fall of 1977 or spring 1978.

Predictably, there has been a little grumbling about taking two lakes in the same area out of the fishing picture at the same time. But, there is a very good reason for the schedule that biologists are following on the white perch problem.

It is necessary to renovate Stagecoach as soon after Wagon Train as possible, since one could serve as a source of white perch to reinfest the other if left untreated. In fact, leaving a lake with the white perch population intact could endanger every other lake in the Salt Valley system.

This summer, when Stagecoach Lake is drawn down and fisheries personnel are applying the chemical to the reservoir and creek, it might seem that the price of controlling the white perch is a pretty stiff one.

But, consider for a moment what the white perch might mean to the rest of the Salt Valley lakes if allowed to survive in Stagecoach and spread to the others. In a few years, similar renovations might be required at many of the other lakes. In view of this threat, perhaps the price paid this year at Stagecoach and last year at Wagon Train is not so great, after all. Ω

THE VIEW FROM BELOW

DIVE INTERSTATE 80? But I-80 is a concrete highway, not a waterway or any kind! The late Mel Steen had a vision for sportsmen that involved the building or Interstate 80. That dream entailed transforming into recreation areas the lakes created bv pumping fill for highway construction. These public areas have become a Mecca tor fishermen, campers, and especially divers.

Scuba diving in Nebraska is limited primarily by poor underwater visibility. There are many lakes and rivers in the state, but verv, very few that are clear enough for diving. Sandpits have always contained some of the clearest waters, but private owners quite often limit access to their lakes. The Interstate Lakes have it all-free access and clear water-for local divers from Grand Island to Ogaliala and manv others, especially from the Lincoln and Omaha areas.

Ocean-based divers might not even consider diving these comparativelv barren waters. However, our hardy, land-locked enthusiasts take advantage of the Interstate Lakes. We, too, have the beauty and wonderment inherent to the underwater world — even though one may have to look a little harder for it.

As a member of the Kearney Aqua Lords, I dive year-round, including going under the ice. Our club participates in a number of organized dives each year, but more importantly, it provides a group of about 40 potential diving buddies. Diving is by nature not a group activity, but neither should it be a solo affair. Thus, the majority of my diving is done with one or two friends. I probably dive about 25 or 30 weekends of the year —locally or at Lake McConaughy. I also try to make Lake Oahe at Pierre, South Dakota, at least once or twice a year. In addition, I try to make one long-distance dive trip each year to some place like Catalina Island off the coast of southern California, or the Bahamas.

Diving equipment includes the standard items such as mask, fins, snorkel and

For underwater photography I use a Nikonos II J5mm camera with a 35mm lens. It is an amphibious yrewfinder camera requiring no separate housing to make it watei-tight. In order to provide ample light and restore colors absorbed by the water, I use a Subsea Mark 100 electronic strobe which is also amphibious. Three Hydro Photo close-up lenses which can be attached under w«ater give me a choice of shooting at 4 1/4, 8 1/2 or 15 inches from the subject. A Green things "Opal eye" wide angle lens (also attachable under water) allows me to shoot photographs of entire divers from a distance of only three feet. These lenses, whic h allow me to get very close to the subjet are essential for good quality photographs in Nebraska's waters.

Prolific stands ol moss grace most sandpits within a le*w years of their pumping, changing a lunar landscape into a botanical garden, this moss is functional as well as

A diver with a bit of imagination fantasizes as he swims through the moss. He may imagine himself gliding through a forest of giant kelp off the coast of southern California. The thrill is much the same, only the forest is on a little smaller scale. A really active imagination allows the diver to fly weightless through a terrestrial forest environment. This is a rare experience shared only by divers and astronauts.

The crayfish, commonly known as the crawdad, is a colorful character dressed in

The largemouth bass resembles one of F. Scott Fitzgerald's nouveau riche. Always wearing striped formal wear, he is both skittish and excessively haughty, as if trying to impress the "old money" at a Yacht Club party. Very aloof during the day, he is more easily approached at night. Feeling secure in his extravagant tree stump mansion, he will accept all callers, even crawdads and divers. If disturbed, he may disappear down one of the cavernous hallways, but usually returns in a short time, composed and receptive.

The green sunfish carries on like a tipsy, obnoxious court jester. Resplendent in his bright-speckled, fluffy finned dress, he hovers about and intrudes on a quiet diver at any time. He may unashamedly and comically admire himself in the mirror of a camera-lens. If the buffoon can't get the laugh, he'll go as far as to nip the diver's backside in art-awkward attempt at humor.

The box turtle is one of the most colorful denizens with his circus-wagon paint job. As he lumbers along, a diver can almost hear accompanying calliope music announcing the arrival of the circus. The turtle moves along slowly/pausing for the necessary publicity shots. Then he continues on, gradually making his way to the Big Top.

The plants and animals found in Nebraska waters offer a rich and varied diving experience for Nebraska enthusiasts. The relatively clear water and the free access to the Interstate Lakes constitute a dream come true for divers. Ω

A QUESTION OF TREES

THE PIONEERS, who kept their wagons close to the Platte River for week after week on their long journey west, would be amazed to see the river today. Few would recognize its channel, lined with cottonwood, as the same wild, free-ranging, treeless river they came to know so well.

There were occasional trees, of course, but they were mostly confined to islands and sheltered places. Natural forces, such as fire and flooding, did not favor the permanent establishment of trees along prairie rivers. In addition, the activities of bison eliminated stands of young trees that otherwise might have survived.

With settlement, the long dynasty of free-roaming bison and uncontrolled prairie fires came to an end. As always, cottonwoods sprang up along the moist river bottoms, and those sufficiently removed from the current-scoured main channels survived the periodic floods and grew rapidly. Yet floods remained, and the rivers could still exert authority over their floodplains. More than half the trees along the Republican River in Nebraska and Kansas were estimated to have been lost to the disastrous flood of 1935.

Flood control projects effectively eliminated the last natural impediment to the long-term establishment of timber along the prairie rivers. Few of the pioneers who forded these naked rivers could have guessed that within a century trees would crowd the banks.

Few sights in Nebraska suggest rugged permanence like a huge, gnarled, mature cottonwood. Yet for all its dominance along much of Nebraska's landscape, the future of the cottonwood in its present density is in question. Two factors, one natural and one man-caused, conspire to reduce the cottonwood.

The first factor is simply natural succession. Cottonwood is a "pioneer" species, an invader of disturbed sites. Before rivers and streams were impeded by dams, fast-flowing water continually altered the channels. Bare, open areas were constantly created, ideal seed beds for the pioneering willow and cottonwood species. On the exposed, sun-drenched sites the seedlings grew rapidly in dense stands. Subsequent flooding and channel disturbance obliterated most, but the cycle continued and new stands appeared every year. Those seedlings that became established on a favorable site survived. However, the whim of the river ruled, and most of the millions of seedlings did not remain long enough to compete with one another for space and light or stabilize the site. Yet, because of the immense numbers of seeds produced at irregular intervals during the summer —conveniently carried by the river itself— the cottonwood could withstand such attrition. Like most other pioneer species, it depended on site disturbance to persist.

With the advent of flood-control and highway development, the conditions of perpetual change to which the cottonwood had successfully adapted, dramatically changed. More seedlings survived and, for a time, flourished. As the crowded stands of trees grew, they began to change the conditions of the site. The leaf litter and the debris they accumulated during high water gradually added humus to the soil. More importantly, the shade cast by such a close stand of maturing trees inhibited further germination of cottonwood. Other tree species capable of growing (Continued on page 44) in the shade of the cottonwood canopy began to infiltrate the site.

A QUESTION OF TREES

(Continued from page 42)

A QUESTION OF TREES

(Continued from page 42)

Since cottonwood is not an especially long-lived tree, the natural processes of plant succession would tend to replace it as the dominant tree species as the 100-year-old cottonwood giants began to die off. A mixed hardwood forest, composed of shade-tolerant species, would emerge. These would include green ash, boxelder, American and slippery elm. The cottonwood, which began the succession process, would be phased out from this stabilized community.

However, few tracts of land remain undisturbed by man long enough for this natural plant succession to occur. Wood •is a valuable resource that man has always exploited for fuel and implements. At the same time, timberland stood in the way of crop production. Clearing land of trees for agricultural purposes on a grand scale dates back to medieval days when the forests of Europe steadily diminished before the wooden plow. What took centuries to accomplish in early Europe required only decades in 18th and 19th century America. The great eastern forests of oak, maple, sycamore, beech, walnut and white pine disappeared quickly. The transformation was inevitable and necessary, but the waste was appalling.

Nebraska seems an unlikely place in which to discuss the loss of timber. Looking at a satellite image of the state, one is perhaps most impressed by the absence of large timber stands. There is the Pine Ridge, of course, with its 200,000 acres of Ponderosa; the man-planted pine forests near Halsey and Nenzel; the timber pockets along the Missouri blufflands; and the frail, barely discernible but important ribbons of trees along the river courses of the Platte, Republican, Loup....

Trees along those rivers are going fast. Using the 1955 woodland inventory as a basis for comparison, the University of Nebraska Department of Forestry, using current aerial surveys, estimates that fully two-thirds of the trees along the Republican River have been cut. At first, one is tempted to hold the sawmills responsible for this decline. After all, of the 36 saw-mills currently operating in Nebraska, only 9 do not utilize cottonwood, the dominant tree species of these drainages.

• Yet mil! operators are interested in selective cutting, rather than clear cutting. Since there is no local demand for pulp, economy demands that they handle only the high-yield saw-log trees and leave the rest. While the after-effects of such an operation might appear disastrous, there are immediate benefits. By culling some trees, the remainder of the stand is rejuvenated. 44 And by breaking the closed canopy, allowing sunlight to penetrate, new cottonwood growth can become established. Sunlight also promotes the growth of forbs and brush, important cover and food sources for wildlife — especially deer, pheasant and quail.

Landowners themselves are responsible for most tree loss. Too often, the local sawmill becomes the vehicle by which the landowner converts timberland to pasture or cropland. In Seward County alone, 16 percent of the trees have been removed during the last 10 years. Most of this tree loss comes from the destruction of shelterbelts, another victim of the times. More than any other factor, the center-pivot irrigation system seems to be the culprit. Its wide-swinging arc respects no boundaries, swallowing upfencerows, windbreaks, draws and river-bottom timber —all the odd parcels of otherwise non-cultivated land so important to wildlife.

One can hardly blame the farmer-squeezed between inflation and limited land area —from wanting to bring every possible acre under cultivation. Most land-owners might feel that a few acres here and there might not make much difference. But when the acres are totaled, county by county, the annual loss of trees becomes alarming.

The lesson learned during the dust bowl was that not all land is suited to agriculture. Just as dry years promote wind erosion on vast areas of undiversified cropland, so do wet years promote water erosion. Low areas associated with river drainages, especially if the land is sloped, would best be left to trees.

Ironically, it was agriculture that was responsible for the appearance of trees on the prairie and along the prairie rivers. Now it is agriculture that is responsible for the loss of those trees. As always, it is wildlife that first faces the consequences of drastic land conversion. But, as has been learned time and again, problems of the environment are soon inherited, with compound interest, by man. Ω

FISHING...AFTER DARK

(Continued from page 9)Some deft work with a flyrod, or the more conventional minnow or jig tactics, will work well if the fisherman approaches without a whole lot of noise.

Those who don't have the patience to hunt up brushy crappie holes or surface feeding activity can sometimes make their own crappie hotspot. A couple of ingenious tricks with gas lanternsand electric lights will do the job.

A homemade rig consisting of a two-foot by four-foot chunk of white plywood and a gas lantern, works well from a boat. The plywood must be set up amidships, much like an extension of the gunwale. A lantern hung over the water on the outside of the plywood will draw bugs quickly, and crappie a bit later.

The lantern can be used alone, but the plywood is a nice refinement. It acts as a reflector, keeping most of the light (and most of the bugs) out over the water where you want them.

A somewhat fancier, store-bought rig is also available, and it can do double duty on both crappie and white bass. It consists of a styrofoam float with a sealed-beam headlight poking out of the bottom. Hooked to a 12-volt battery, this outfit shoots light directly into the water. This apparently attracts minnows which draw the game fish, and does not draw nearly as many bugs as does the gas lantern setup. This battery powered job has not yet found a lot of favor with Nebraska fishermen, but it has good potential. In the past year or two, it has been the rage among white bass fishermen on Kansas reservoirs, and there is no reason to believe it will not work on both crappie and white bass in Nebraska.

The gas lantern trick has already caught on among white bass fishermen at some of the southernmost Nebraska reservoirs, particularly Harlan County. Gas lanterns are put out on boats and docks at dusk

As with crappie fishing, minnows are the best bait, although jigs also work well on white bass. On occasion, a spoon or spinner might also produce.

Generally, the night-time white bass fishing is most popular in early summer. It's hard to tell why it is abandoned in July and August. Perhaps it's because the fish change their habits when the shad start to school, or it might be because the daytime "gull-chasing" is more exciting and attracts all of the attention.

Another very popular kind of night angling is practiced by the state's catfishermen. The cats they seek are quite at home in the dark, since they find their food by smell rather than sight. The dark hours are as suitable a meal time as are the daylight ones as far as the fish are concerned. And, most catfishermen seem to have plenty of time at night to take advantage of catfish prowling about for midnight snacks.

Still-fishing a variety of smelly baits is the mostpopular technique, although some anglers do well by drift-fishing if there is a gentle breeze. Terminal tackle varies, with some using little or no weight, others using a lot, some employing slip-sinkers. Apparently the right bait, the right spot and confidence in the technique are most important factors.

Darkness is just a small inconvenience for most catfishermen. Many come equipped with a gas lantern or powerful flashlight. But on moon-lit nights, they use the lights sparingly, or sit at the very edge of the circle of lantern light, thus keeping their night vision relatively intact. This also minimizes trouble with bugs.

One handy item a lot of them use is a tiny bell, usually a turkey bell, equipped with an alligator clip. The clip is attached to the end of the rod when still-fishing in the dark, so that any twitches of the rod are translated into sound when a catfish begins pecking at the bait.

Walleye are another traditional target for night-tirrle Anglers. And, they are no less frustrating and finicky in the dark than they are in daylight. Most Nebraskans still-fish with minnows, some toss jig-and-m in now combos and lures to deep-water points or rocky areas, or troll randomly with artificials. However, they often limit their chances of success by fishing too deep. Walleye spend a lot more time in relatively shallow water than a lot of fishermen realize, particularly at night.

A few ,fortunate Nebraska fishermen have mastered the back-trolling techniques involving nightcrawlers, minnows or other live bait. These seem to produce enough walleye during the day that they don't have to fish at night. But, there comes a time in late summer when walleyes boycott even these experts.

J'S OTTER CREEK MARINA NORTH SIDE LAKE McCONAUGHY HWY. 92-OPEN YEAR AROUND ...a Big Bicentennial Travelgram

...a Big Bicentennial Travelgram

Veteran back-trollers from the northlands, where walleye fishing was invented, say that their "goggle-eyes" hole up in shoreline weedbeds in late summer, and can best be taken at night by casting floating lures into openings in the vegetation. There's no reason to believe that this would not hold true for Nebraska's walleye, too.

Another night-time denizen of the shorelines and shallows is the largemouth bass. During hot summer days, this husky fellow hides out in cool, deep water, which also shields him from the sun's irritating brightness. But after dark, he heads for the shallows to dine on minnows and other small fish, frogs, crawdads, worms and large insects.

Though it's dark where he lurks, he still depends to a large extent on sight to find his food. Most of his vision involves silhouettes backlit by the sky. However, the bucketmouth can detect vibrations made by baitfish and lures, both through his skin and by internal ears. This helps him locate a fleeing minnow, a spinner or a noisy surface lure as it pops, chugs, sputters and flutters along.

This same sense of hearing also tells the bass of the presence of a careless fisherman who shuffles gear around in the boat or stomps along the shoreline. Bass in the shallows feel vulnerable, and anything out of the ordinary will usually give them lockjaw. This seems to include bright lights flashed around on the water, in the boat or on shore.

To sum it all up, the best night-time bass fishing combination seems to be a noisy lure but a quiet fisherman.

There are some hints that help all after-dark fishermen, no matter what species he's going after. They include:

Simplify and organize —Keep gear and tactics simple. Rig poles, fill lanterns, locate stringer, pliers, knife, etc. before shoving off. Have gear well organized.

Specialize —Don't switch from crappie to bass to walleye to catfish in one evening. More time will be spent changing tackle and locating than fishing.

Plan —Have specific fishing spots in mind when you arrive at the lake. Scout them in the daytime so that you know the quickest and quietest way in and out.

Don't spook fish —Keep use of light to a minimum, except where used as an attractor. Use plenty of insect repellent to keep bugs off, but don't get any on your

Be safe —Make double sure that running lights and other safety equipment on the boat are in top shape; keep speed down, wear life jackets after dark, keep night vision intact with minimum use of bright lights.

The lake or river is a different world after dark. It looks different, it sounds different, and its fish act different. The angler who appreciates and understands what is going on after dark is in for some enjoyable times full of good fishing. Ω

THE BRONC, THE SAND LIZARD AND THE SUSAN SNOOKS

(Continued from page 23)creek and found that we had simply gone around the head of it."

In the following chapter they reached Valentine, about 4 in the afternoon and pressed on to Cody. They had to push the cars up sand hills, reaching Cody about 7. Next morning more pushing and even shoveling paths for the wheels. "When we finally got to the main road and into Merriman, I was so hungry and tired I fairly trembled. We stopped in front of the drug store and went in and got a cool drink of pop."

After dinner they started for Gorden, but with a guide, since they had learned that the road wound through pastures and hills. They ran on to an old friend, "our janitor's brother," and he invited them to his farm to camp on fresh hay, "a lovely featherbed."