NERASKAland

June 1976

NEBRASKland

VOL. 54/NO. 6/JUNE 1976 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission Fifty cents per copy. Subscription rates $5 for one year, $9 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKMand, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. commission Chairman: Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 Vice Chairman: Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-Central District, (308) 745-1694 2nd Vice Chairman: Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-central District, (308) 452-3800 H. B. "Tod" Kuntzelman, North Platte Southwest District, (308) 532-2982 Richard W. Nisley, Roca Southeast District, (402) 782-6850 Director: Willard R. Barbee Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, Jr. Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: Jon Farrar Greg Beaumont, Ken Bouc, Contributing Editors: Bob Grier Faye Musil, Tim Hergenrader, Roland Hoffmann, Bill Janssen, Ben Schole Art Director: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commision 1976. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska JUNE 1976 Contents FEATURES THE HABITAT PLAN HOPE FOR THE FUTURE 8 YOUNG WILDLIFE 10 ONE QUARTER HORSE, THREE QUARTERS DYNAMITE 16 RAINBOW TROUT IN THE NORTH PLATTE VALLEY A special 16-page, 4-color section on the life history of this valuable fish 18 SAFETY WHEN IT COUNTS 35 THE WILDERNESS ETHIC 36 FISHING ON VACATION 38 DEPARTMENTS SPEAKUP 4 TRADING POST 49 49 COVER: Unfurling the sails and tacking and running before the wind are becoming increasingly popular with Nebraskans as the art and enjoyment of sailing touches more people. The state's largest body of water, Lake McConaugh, gets its share of sailors, but others are also sprinkled with colorful wind machines. OPPOSITE: While not everyone prefers to catch carp on hook and line, summertime fishing would not be the same without those big, scrappy, prolific fish. Interest in them is about equally divided between anglers, archers and spearers. Photos by Bob Grier. 3

Speak Up

Water SafetySir /I am writing in regard to the drownings in the state recreation areas of Nebraska. The latest was at Fremont State Recreation Area. Swimming is one of the best "fun" sports there is for a family.

Fremont has a free public beach and lake to swim in, however there are no lifeguards.

The swimming lake at Two Rivers does have lifeguards, however the hours are limited from 1 to 5 due to what the state says, they are cutting back on cost. Also, the Louisville State Lakes have no lifeguards. No Money!

The state, however, is shoving another $104,000 toward camping facilities at Ogallala. This money would be spent much better, I would think, for lifeguards to save lives or to build a pool at Two Rivers State Recreation Area, which would be a lot safer.

Chadron and Ponca Parks have pools. How come the state is always shoving money to western Nebraska when the population is in eastern Nebraska? Let us hope the state legislators and the state Game Commission wake up before another person drowns due to very poor management.

Allen Arp Yutan, NebraskaNo one wants to sacrifice safety for needless facilities, but different communities have many needs which they give priority to. And, the state agencies cannot spend money wherever they want to, as there are also priorities here. Unfortunately, safety is not something that can be easily measured, whereas the need for a camping area or other such facility, can be seen. It comes down to hard facts where money is concerned, and there are many more requests and services than funds available. Also, presence of lifeguards cannot insure safety — drownings occur even when they are on duty. Some common-sense rules would almost eliminate water-related accidents, such as not swimming alone, not going into water too deep for 4 the person's ability, not relying on flotation devices in deep water, and many others. The individual should have the primary responsibility for safety, and to take as many precautions as possible. (Editor)

* * * Reap the WindSir / I was reading Lois Allen's story, "Wind on the Hill" about windmills in Nebraska. Nebraska and all the prairie states are famed for their steady winds. I should think that wind would be the best natural resource, and the safest, for providing electric power. Certainly it would be interesting to see the findings of some good, innovative young engineer's study and figures on it. If every little community had its own power station with its own windmills —electricity wouldn't have to be sent such long, expensive distances as it is now. No matter what people say about how cheap and safe nuclear power is, uranium isn't infinitely abundant, and no one seems to want the wastes buried in their neighborhoods to leach down into their underground water supplies. So, wind power makes sense —especially with some funds put into research and development of creative new systems.

Joanne Ashley Manlius, N.Y.P.S. I've wanted to live in Nebraska someday in a solar heated house powered by a windmill.

I think that is a desire shared by many people, and it seems that at long last, steps are being taken to make "natural" power a reality. We should all get behind all research of solar and wind systems. You might be out here soon. (Editor)

* * * What is Fencerow?Sir / When pioneers laid out this land in 40, 80, 160 acres or larger, the farmer usually put in a fence for the dividing line, with a post every rod and 4 strands of barb wire.

All that is left of many of these fences is a lot of broken posts and rusty wire. Today a single strand of electric fence does a better job.

What I'm getting at is wildlife is in trouble; we need more cover for pheasants, quail, rabbits and birds. If we could get the farmers to replace that old fencerow, with a row of cedar trees, it would sure help wildlife, and wouldn't that make the farm look beautiful?

Ten years after he planted these trees, his boys and neighbor boys could walk along these trees to look at and hunt pheasants and rabbits, and the younger generation would have it to enjoy.

I believe we could get help from the Game Department or the A.S.C.S. to help share the cost of planting the trees. If we want wildlife to survive, we must do something to help. The reason I mention cedar trees is that they are shallow rooted, and you can raise a crop close to them, and all wildlife sure loves to use the cedars when the wind is blowing and snow drifting.

If we could just get a few miles started and show people how beautiful the old fencerow could look, I believe more miles would come easy. But, they should not be right along the road. That is for the road hunter to shoot from the car when it snows. Let's get them planted back in the fields.

Einar Anderson Edgar, Nebraska A tremendous idea. It is tragic watching all the shelterbelts being ripped out after they have served so well all these years. Yet, few if any are being replaced. Fence-rows of trees sounds like a beautifying and functional project that certainly would help wildlife. Let's hope it catches on. (Editor) * * * Cover is GoingSir / According to my travels in Nebraska, wildlife has become an endangered species. Each year all types of wildlife seem harder to find. I know it isn't just my imagination. Just last Saturday I watched bulldozers clear out a long shelterbelt for a pivot irrigation. Last fall that shelterbelt flowed with pheasants. Now it's gone! And that was just one of many I have seen cleared off this summer. Last winter I noticed more frozen and starved wildlife of all kinds. Why? Because we're destroying acres of natural habitat and not replacing any.

Talking about it won't get much done, but sometimes it starts gears turning. ! would favor more split seasons and very short seasons. There are 4-H clubs, gun clubs, Boy Scouts and other groups which could start rebuilding habitat areas all over Nebraska. We also have many people needing work. What more worthwhile project than hiring people to resupply habitat for wildlife?

Terry Greger Central City, NebraskaWhat we need is more people concerned about the problem of wildlife, and willing to do something about it. A major step was taken with passage of LB861, the Habitat Bill, which will mean more funds for all sorts of habitat in the future. But, it isn't the final answer, so keep on observing and talking. (Editor)

NEBRASKAland Magazine invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to Speak Up. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters. — Editor. NEBRASKAlandThe Commonwealth now pays even higher interest rates!

6.25% Passbook Savings 6.54% Annual Yield Comp. Daily 6.75% 1 Yr. Cert. 7.08% Annual Yield Comp. Daily 7.00% 2 Yr. Cert. 7.35% Annual Yield Comp. Daily 7.25% 3 Yr. Cert. 7.62% Annual Yield Comp. Daily 8.00% 4 Yr. Cert. 8.45% Annual Yield Comp. Daily A substantial interest penalty, as required by law, will be imposed for early withdrawal.

Delivered to your home or even your deserted island

Tree City USA

Make your town a better place to live... Plant a tree for tomorrow!

For details of the TREE CITY USA program, write The National Arbor Day Foundation Arbor Lodge 100 Nebraska City, Nebraska 68410There's always a tomorrow with trees

"The Glorious Fourth. An Old Fashioned Day, an Old Fashioned Time, an Old Fashioned Crowd."

These headlines, published over one hundred years ago in the Grand Island Times, serve to announce the Independence Day festivities planned for Fort Hartsuff State Historical Park this July 4th. The Fort was a focal point for such celebrations in the 1870's, and it is hoped that spirit can be brought to life in our Bicentennial year.

"Our Glorious Fourth" was a day of great importance to early Nebraskans. Settlers and homesteaders far from urban centers came together to commemorate the birthday of the nation in whatever way circumstances would permit.

This year's celebration at Fort Hart-suff will begin at dawn, with a black-powder anvil-firing. The morning's activities include an ecumenical religious service followed by a picnic lunch on the grounds. Demonstrations of traditional crafts, including quilting, horse-shoeing, spinning and such entertainments as square-dancing and horse-pulling, are scheduled throughout the afternoon. Foot races and a tug-of-war are being organized for those desiring exercise, with free lemonade to quench the thirst. A number of small groups will provide music of various types, and the work of local artists will be on display. The celebration is expected to continue until sunset.

* * *Activities in honor of the Bicentennial are also being planned for the other state historical parks. Currently on schedule are a crafts fair and soap and candle-making demonstrations at Arbor Lodge; demonstrations by blacksmiths, wheelwrights and other craftspersons at Ft. Kearny; the sight, smell and taste of Oregon Trail cookery at Ash Hollow. Finalized plans will be made public in the June issue of Afield and Afloat, next month's issue of Nebraskaland, and in local newspapers.

NEBRASKAlandPark Lands are for People

THE HABITAT PLAN HOPE FOR THE FUTURE

New funds for enhancement of wildlife lands will be a reality soon. While not the complete answer, this money should slow the tide of cover losses

OF CURRENT INTEREST to many sportsmen and women, even some children, is the future of fish and wildlife in our state. Over the last several years, the governing body of this agency, the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, has become more and more concerned about diminishing wildlife numbers and the reasons for that decline. One of the greatest reasons is related to wildlife habitat — the place wildlife lives and reproduces.

In February of 1975, a Wildlife Habitat Conference was held in Lincoln to discuss the problem of diminishing wildlife habitat and what could be done. The outgrowth of that conference was the formulation of the Wildlife Habitat Plan, as expressed in LB861, which was recently passed by the Legislature and signed into law by the Governor.

As expressed in the Habitat Plan, the intent is to work to preserve and enhance wildlife habitat across the state. It would seem that $2.9 million in new funds per year should make a significant impact, given a reasonable period of time. It behooves us to not expect miracles, for many things are happening to wildlife habitat. Earlier federal agricultural production control programs are gone. Even this winter, many areas of prime pheasant and quail cover have been removed from across our state. Wetlands continue to be drained or squeezed down in size. The rate of hab'at decline will probably exceed anything that the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission can do to counter this onrush of change, but it is necessary that all interested persons understand the full picture, even as we labor with the help of interested citizens to keep a reasonable habitat reservoir. With these broad-ranging realities, we will do our best to extract maximum value for minimum dollars, as granted and directed in LB861.

The plan has essentially three phases of action—acquisition, the Natural Resources District (NRD) private lands program, and the developments of better habitat on public lands, including currently owned or controlled department wildlife lands.

The acquisition phase is to be allocated approximately $900,000 of the new funds each year. When combined with available federal funds, 3,500 acres a year could be acquired, assuming willing sellers of good or potentially good critical habitat lands. Of interest to some will be the fact that by law, according (Continued on page 48)

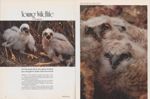

Young Wildlife

For the young, life is not a game of spring but a struggle for space, food and survival

SPRING IS THE SEASON of renewal, the time for new life; it is yet another beginning in the endless cycle of competition between the myriad of life forms in every plant and animal community.

At first glance the explosion of new life in wetland, prairie and woodland seems haphazard and out of control, like a factory gone beserk. Suddenly, animal populations begin to skyrocket.

But this is the best of times, and the land in spring and summer can support many demanding mouths. Each year more life is produced than the earth can possibly 10 NEBRASKAland

Unlike man, nature is amazingly adept at such complicated bookwork. In a balanced ecosystem, each life form —from bacterium to bison —is given a chance, for each performs some vital service crucial to the welfare of the entire community.

For the numbers game to succeed in a world of brutal competition, no species can be so disadvantaged that it easily loses the struggle to survive; and none can be allowed to become so successful (man is a notable exception) that it begins to eliminate others.

To survive, each species must reproduce sufficient numbers each season to accommodate a high mortality ratio. Lower animals, such as insects and fish, beat the odds through sheer weight of numbers. Out of many thousands produced, only a few will reach maturity.

All animals have the reproductive potential to overpopulate their range, but small animals, because of their faster reproductive rates, can achieve an imbalance more quickly than larger animals. Were it not for the continual pressure of predation, insects could attain staggering numbers in a matter of weeks. The ubiquitous house fly, for example, has 8 to 20 generations per season, depending on latitude. One female produces between 600 and 1,200 eggs. If all the succeeding generations survived and themselves successfully reproduced, one season would produce more than 191,000,000,000,000,000,000 offspring, a biotic mass of some 21/2 billion cubic yards; this volume would cover a 24-square-mile area 100 feet deep!

A precocial mammal, the newborn deer fawn, far left, relies on camouflage and an absence of scent to survive its first critical days of life. Canada goose goslings, above, receive constant parental protection during their flightless period, while squirrels, left, find refuge in the safety of a tree den 13

Even the biotic potential of vertebrates is impressive. A meadow mouse, sexually maturq at}about 28 days, has a gestation period of only 21 days and produces 6 to 8 young per litter. In one year a single pair of mice could theoretically produce over 1,000,000 descendants. In a region of California in 1927, house mice reached a density of 82,000 per acre (or over 200 in an area covered by a 9x12-foot rug), a population far exceeding the carrying capacity of the land. Such population peaks are short-lived, however, since the resulting stress on the individuals and the damaged habitat soon lead to disease, starvation, and an increased vulnerability to predation.

Larger animals, such as deer, can also exhibit remarkable population increases in a relatively short period of time. By extirpating the cougar and wolf, the natural predators of deer, man encouraged deer herds to proliferate, which often resulted in the same boom-and-crash cycle. Eventually it was learned that the best protector of deer was, ironically enough, its own natural enemies. By culling the excess young and the old and unfit, the predators insured that the deer herds were genetically strong and maintained at a level within the carrying capacity of their habitat.

Not only must a species successfully reproduce itself year after year, it must also adapt to changing conditions. The immense landscape of evolution is a graveyard littered with vanished species, an impressive array of animals that in one way or another failed to adapt to changes that affected its community or climate.

Reptiles, for example, ruled the earth for a long period, gradually evolving and diversifying in a stable, tropical climate that produced abundant vegetation and tolerated primitive methods of reproduction. Although adaptively superior classes of animals —the birds and mammals —had evolved before the extinction of dinosaurs, their biological supremacy did not challenge the old reptilian dominance until the climate began to cool. Then the differences between reptiles and the birds and mammals became critical. Not only could birds and mammals adapt to cold (since they maintained a constant, internally controlled body temperature), but their methods of reproduction were more advanced than the reptiles.

Although birds, like reptiles, reproduced by laying eggs, they did not simply deposit and abandon them, trusting in the warm earth to incubate the eggs. Instead, they incubated their eggs with their own bodies, continuing to brood and feed the helpless young after hatching. Mammals carried the process a step further, bringing forth young already "hatched/' thereby eliminating the vulnerable external-egg stage altogether. In addition, they provided nourishment for their young from their own bodies.

Not only did these significant biological improvements insure the survival of birds and mammals, they also gave them a certain degree of independence from minor shifts in the climate. Both could be active in cold weather; and birds, with their wings, could migrate elsewhere to escape seasonally inhospitable conditions. Food supply and competition became the only restrictions to adaptive radiation and both birds and mammals flourished, diversifying into a bewildering array of forms and extending their ranges even into the polar regions.

Not all species within an animal class have the same manner of reproduction, however. Some snakes and fish, for instance, give birth to live young. Among the mammals, most are placental, nourishing the developing embryo within the uterus. A few, such as the opossum, are living representatives of the ancient order of marsupials, animals which give "birth" to underdeveloped young. Baby opossums are "born" 13 days after fertilization, making their way into the mother's marsupial pouch for further development. At the time of transfer, the young are so small that 20 would be required to fill a teaspoon!

Young placental mammals are usually helpless at birth, but some arrive at an advanced stage of development. Baby jackrabbits are said to be precocial, since they are born with hair, developed senses, and muscular coordination —an obvious survival advantage in their prairie habitat. Unlike hares, such as jackrabbits, true rabbits give birth to altricial young. At birth, baby cottontails are naked, blind and utterly helpless for many days. This is not a serious disadvantage to the cottontail, as it would be to the jackrabbit, since the cottontail's habitat provides plenty of protective cover.

Birds, too, show the same differences. Although a meadowlark and a killdeer may nest only yards apart, the young of the meadowlark are altricial at hatching —naked and blind —while the precocial killdeer, fully feathered and coordinated, are active and capable of leaving the nest soon after hatching.

Spring is a celebration of life. The ancient and the new struggle to survive, to insure their kind another spring. But life is what sustains life, and the role of most will be to serve as sustenance for others. In a world of living things, so excellently embroidered, death is but another form of life. Ω

15

ONE-QUARTER HORSE THREE-QUARTERS DYNAMITE

THE QUARTER-HORSE breed originated during the colonial era, in the Carolinas and Virginia. There, more than 300 years ago, match-racing was a leading outdoor sport, with races run on village streets and along country lanes near the plantations. Seldom were the horses raced beyond 440 yards, hence the colloquial name, "quarter miler."

The foundation of these quarter-running horses came from the Arab, Barb and Turk breeds brought to North America by Spanish explorers and traders. Stallions selected from those first arrivals were crossed with a band of mares which arrived from England in 1620. The cross produced compact, heavily muscled horses which could run a short distance faster than those of any other breed.

16The uses of the quarter horse were manifold. As the white man moved west he took the quarter horse with him to help conquer and settle the continent. This is the horse that pulled the plows, wagons and buggies of the pioneers; that went up the trail with cattle to pasture and market; carried preachers and their Bibles to furthermost points of worship; and sped the country doctors to the beds of injured and ailing frontiersmen. The quarter horse survived time and change because he excelled in qualities which were of major importance to the greatest number of persons in diverse occupations and geographical areas. He was early adopted by ranchers and cowboys as the greatest roundup and trail driving horse they had seen, for he possessed inherent "cow sense."

The quarter horse became established in the Southwest in the early part of the 19th Century. As he trailed cattle north and west, he left progeny along the way, though his greatest influence remained in the Southwest until after his registry was established in 1941 by the American Quarter Horse Association. In the years after, the breed spread rapidly throughout the nation, into Canada, Old Mexico, and can now be found in over 50 foreign countries. His registry now is growing more than three times as fast as any other horse breed in the world.

More than three centuries elapsed between the origin of the quarter miler breed in colonial America and the organization of the American Quarter Horse. Years of talk around the branding fires at cow camps and at conventions of cattlemen emphasized the need for forming an organization NEBRASKAland to collect, register and preserve the pedigree of quarter horses. Yet the idea faded away with those who wished to perpetuate the bloodlines of the best individuals in every good remuda.

It was not until 1939, at the Southwestern Exposition and Fat Stock Show in Fort Worth, Texas, that champions of the breed were able to tie down suggestions for establishing an organization to represent the Quarter Horse and those who believed in him.

On March 15, 1940, a group of men and women from several southwestern states and the Republic of Mexico met in Fort Worth to formally establish the American Quarter Horse Association. And it was not until early 1941 that the first horse was registered by the young association. That first JUNE 1976 horse was Wimpy, and he stood Grand Champion Stallion at the 1941 Southwestern Exposition. He was sired by Sol is, and out of Panda, both of which trace back to the solid foundation bloodlines of Old Sorrel, Hickory Bill and Peter McCue. Wimpy was foaled in 1937 on the famous King Ranch in Texas, and died in August of 1959 on the ranch of Rex Cauble, Crockett, Texas.

A model had been set and the American Quarter Horse Association was off and running. The first several thousand quarter horses registered were done so by inspection of type and bloodlines. Later, and today, only horses with two parents registered by the Association may become a permanently registered quarter horse. With over one million registered horses in the American Quarter Horse Association, more than all other breed registries combined, it is only to be expected that they would have the largest horse show, and the horse race with the richest purse of any in the world.

The largest horse show of any single breed is held each fall in Coiumbus, Ohio with more than 2,000 entries of the country's best horses. All phases of the quarter horse are tested. Events include everything from halter conformation classes to cutting, roping and jumping to driving and trail classes. Along with this show are many clinics and demonstrations to help horsemen and women keep up with the latest practices and techniques.

The horse race with the world's richest purse is held in Ruidoso, New Mexico every (Continued on page 46)

17

THE RAINBOW TROUT IN THE NORTH PLATTE VALLEY

Cold, clean water is the key to trout production. The Rock Creek Hatchery is now threatened, and a new location may be necessary

GOOD TROUT FISHING in Nebraska depends on good coldwater management. And that management would be a tough proposition without good trout hatchery facilities upon which the fisheries biologist can draw.

In dealing with natural trout habitat, the fisheries manager must have the services of a good hatchery to provide fish for new waters, restored streams, or renovated waters.

Hatcheries are also needed to propagate specific strains of fish with certain characterisitcs that might enable them to adapt to specific habitats. Trout from the Alliance Drain, for example, seem better adapted to a bit harsher environment, and hatcheries might produce hardier fingerlings for stocking other streams from eggs of the Alliance Drain fish.

Another important use of the hatchery has already proven very successful. Many streams of the North Platte Valley can support trout once they reach a couple of inches in length, but conditions there are not right for spawning. Eggs from North Platte Valley rainbows can be hatched and raised to fingerlings before stocking in these streams.

Trout hatcheries, however, are rather hard to come by. The trout's need for cold, clean, well-aerated water severely limits potential sites in Nebraska. The Game and Parks Commission's present trout facility, Rock Creek Hatchery at Benkelman, has been such a site. Over the years, the water has flowed cold, clean, and in abundance.

However, the very existence of this facility a few years down the road now seems in question, so improvements must be delayed. In recent years, the flow of springs feeding the hatchery have declined, and it appears that the large number of irrigation wells sunk a few miles away for center-pivot systems, is the cause. Furthermore, it seems likely that much more irrigation development will come in the near future.

Geological studies have been initiated by the Game and Parks Commission to determine the relationship between irrigation wells and the hatchery's water supply. If these studies indicate that the hatchery's water supply is, indeed, threatened by irrigation, then it would make little sense to invest money in major improvements. Instead, a new hatchery site will have to be found.

Sites offering the abundant cold, clean water needed are hard to come by in Nebraska. But, if the Rock Creek facility's days are numbered, a new trout hatchery will be needed to keep Nebraska trout fishing up to its potential. Ω

18 NEBRASKAland

RAINBOW CYCLE OF LIFE

Lake McConaughy trout begin their life in gravel riffles of North Platte feeder streams. Three years later they return to perpetuate their kind

LAKE McCONAUGHY is the only 4Great Plains reservoir that supports a self-sustaining rainbow trout population. This unique rainbow population lives during the spring, summer and fall in Lake McConaughy and spawns during the winter in tributary streams of the North Platte River in the Scottsbluff area.

Fishing for large rainbow trout in the tributary streams began in the late 1940's. Trolling for trout in Lake McConaughy, however, did not become popular until the late 1950's and early 1960's. With this popularity came a significant increase in fishing pressure not only in the lake but also on the spawning streams. The Game and Parks Commission was concerned because not enough information was available to properly manage the rainbow trout population under increased fishing pressure. During the mid-1960's a study was initiated to collect information and prepare a rainbow trout management plan for the upper North Platte River drainage. This publication is part of that endeavor.

The Lake McConaughy rainbow begins its life in the gravel riffle areas of groundwater streams in the upper North Platte Valley. The female rainbow fans a depression in the shallow gravel areas of the stream. She then deposits eggs, and they are quickly fertilized by male rainbows. The female covers the eggs with four to eight inches of gravel and then abandons the nest. The spawning nests or redds, visible because of the disturbed gravel, can be seen throughout the winter in the spawning streams. Rainbow trout spawning is probably confined to the tributary streams of the North Platte River. Spawning has not been documented in the main channels of the river.

Large gravel areas in swift-flowing streams are among the most important requirements for successful reproduction of rainbow trout. Gravel and rocks of one to four inches in diameter provide the spawning habitat in Nebraska. During the spawning season, stream water must be clear; otherwise sand or silt will drift over or settle on the gravel, smothering the eggs that are deposited in the gravel riffle areas. The North Platte Valley contains more streams capable of supporting natural reproduction of trout than all the rest of Nebraska streams combined.

It takes approximately 8 to 10 weeks for the rainbow eggs to hatch and for the fry to develop. After the fry have absorbed their yolk sacs they emerge from the gravel and start feeding on tiny invertebrates drifting in the water. Rainbow fry can be observed during the February to May period in shallow, quiet, slow-moving areas of the stream. By June these fry have reached two to three inches in length and are strong enough to remain in swifter water, where they are hard to observe unless feeding on insects at the surface. The small trout grow during the summer, fall and winter in their native streams. By early spring, one year after being hatched, the juvenile rainbow have reached a length of 7 to 10 inches. Most of them are then ready for the long journey out of the spawning streams, down the North Platte River and into Lake McConaughy. During the 1965 to 1974 period, 91 percent of the juvenile rainbows moved to the lake at the age of one year, while 9 percent remained in the spawning streams two years before migrating to the lake. The juvenile rainbows that spent two years in the spawning streams probably represent the younger and slower growing members of the population. Virtually all the rainbows in the North Platte Valley streams migrate to Lake McConaughy.

The appearance of the juvenile rainbow changes drastically just prior to the downstream migration to Lake McConaughy. The parr marks (dark, oval markings on the side) characteristic of fingerling-size rainbow, disappear while the sides of the trout turn from li^ht* gray to a bright, silvery white. The tips of the tail and to a lesser extent the tip of the dorsal fin (large fin on the back) turn nearly black and the entire body becomes more streamlined. This change in appearance is described as the "smolt stage" and the juvenile rainbows moving to the reservoir are called "smolts." The 7 to 10-inch rainbows with their black tails are obvious and can be spotted by quietly walking along the spawning streams in late February, March and into April just prior to downstream migration.

The smolts enter Lake McConaughy during March, April and May. Some years during May the small trout or smolts can be observed breaking the surface of Lake McConaughy in the Sport Service Bay area, located directly south of the dam. Upon entering Lake McConaughy, the rainbow feed upon plankton, consisting mainly of cladocera or water fleas. The water fleas in the adult stage are only .1 inch

in size and are most abundant

during spring and early summer.

The rainbows grow rapidly, and by

July when the gizzard shad spawn,

are 12 to 13 inches in length. At this

size the rainbows change from a

plankton diet to one of small fish,

usually gizzard shad. At the end of the

first summer or growing season in Lake

McConaughy, the rainbows have

grown to an average length of 15

inches. A small percentage of them,

mostly males, will mature at this size

and migrate upstream to spawn. However, a majority of the Lake McConaughy rainbows become sexually

mature one year later, at three years

of age. At that time they migrate out

of the lake because they cannot successfully spawn in standing water.

in size and are most abundant

during spring and early summer.

The rainbows grow rapidly, and by

July when the gizzard shad spawn,

are 12 to 13 inches in length. At this

size the rainbows change from a

plankton diet to one of small fish,

usually gizzard shad. At the end of the

first summer or growing season in Lake

McConaughy, the rainbows have

grown to an average length of 15

inches. A small percentage of them,

mostly males, will mature at this size

and migrate upstream to spawn. However, a majority of the Lake McConaughy rainbows become sexually

mature one year later, at three years

of age. At that time they migrate out

of the lake because they cannot successfully spawn in standing water.

Two distinct spawning runs occur from Lake McConaughy. The largest occurs during the fall, with rainbows starting to leave the lake in September and continuing until late November. The peak usually occurs between the last week in October and the middle of November, depending somewhat upon weather. Abrupt, adverse weather conditions temporarily reduce the number of rainbow migrating from the lake, but a sharp rise in the barometer usually triggers an increase in the number leaving. Rainbow prefer to migrate upstream during the night. The second largest run of rainbow is during the spring. This migration occurs about the time of ice break-up in the lake (March 1 to April 1). Undoubtedly some rainbow trout move during the December-February period, but these could not be monitored at the electrical weir and fish trap located on the North Platte River near Lewellen. This facility was instrumental in collecting most of the North Platte rainbow trout life history data.

Annual spawning runs during the 1965 to 1974 period were composed of 5% two-year, 70% three-year, 23% four-year, and 2% five-year-old rainbow. There is a high natural mortality of spawners between the first and second year. During the 1965 to 1974 study, 77% of the rainbow spawned only once, 21% twice, and only 2% spawned for a third time. This spawning mortality seems high but is actually lower than reported for rainbow populations in other states. The spawning runs contain approximately two females for every male, which is normal for rainbow populations. The average size of rai nbow trout spawners is 20.6 inches with an average weight of 3.9 pounds.

When the trout complete their journey up the North Platte River and enter the groundwater streams to spawn, their life cycle is nearly completed. And, they end in the same streams where they were hatched three years before. They have moved the 100-mile length of the North Platte River twice, been exposed to high water temperatures, flooding, irrigation return waters, and predation by both man and other fish in the streams, river and lake. The few that have returned are expected to perpetuate the species, which they can if the proper spawning habitat is available and the waters remain clean and pollution free.

Rainbow trout captured in the Lewellen trap were tagged from 1967 to 1972. Anglers returned 19 percent of the tags, indicating that anglers catch a minimum of 19 percent of the population. Data also indicate that of the rainbows caught, 73 percent were taken by stream fishermen and 27 percent by lake fishermen.

The importance of the spawning streams is shown by the return of tags by anglers. Approximately 42% of rainbows caught in spawning streams came from Nine Mile Creek.

Most of the trout spawn in the streams where they were hatched. A small percent, however, "stray" to other streams. There appears to be less straying and more of a homing instinct in the fall-run fish than the spring run. This straying is most noticeable in Pumpkin Creek. Although very few trout successfully reproduce in Pumpkin Creek because of poor spawning conditions and high summer water temperatures, each year, especially during early spring, large rainbows migrate up Pumpkin Creek several miles to a small irrigation dam.

The North Platte Valley streams have the potential to produce more trout naturally than all the other streams in the state combinedAll of these are strays which were hatched in other streams in the drainage. Rainbow straying also occurs in Lake McConaughy. During the spring, as soon as the ice breaks up, a small percentage of the total trout population in Lake McConaughy can be observed in the Sport Service Bay area and similar rocky shores in the southeast corner of the lake. These fish apparently do not have a strong migration instinct to leave the lake even though they can never successfully spawn there. Especially in the last 10 years, most of the rainbow in the lake have hatched or originated from spawning streams in the upper North Platte Valley. Because the trout which stay in the lake never spawn successfully, fewer are seen each year. This fact, rather than a smaller number of rainbow in the lake as suggested by some anglers, probably explains why fewer numbers of rainbow have been observed the past few years along the rocks during early spring.

The Lewellen trap made it possible for the first time to collect information from large numbers of rainbow trout during their spawning runs. One example is the occurrence of deformed trout in the population. Examination of 5,184 rainbow during 1967 to 1975 shows 241 (4.6 percent) were abnormal or deformed. Occasionally, anglers report catching a deformed rainbow. It is usually a natural occurrence, and is rare because deformed fish are usually too weak to survive in a natural population. Deformities are much more common in hatcheries where there is less competition. Anglers also have reported trout with red, infected spots. The same thing was observed on rainbow examined at the Lewellen trap. The infected areas are caused by a parasite identified as an "anchor worm". This condition is most noticeable during the August-November period, and is caused by a small parasite attached to the side or fins of the fish. It does not cause the trout to be unfit for the table, but does detract from its normal appearance.

In any self-sustaining rainbow population, the most competitive and successful individuals survive to carry on the population. Rainbow trout were originally spring spawners. In the case of the Lake McConaughy rainbow, however, a more successful fall run has become established because the stream environment in the North Platte River drainage gives it an advantage over a spring run. Fall spawners have an advantage because the young have from February until May to grow enough to survive the critical conditions that exist during summer months. Also, during this period they become acclimated to warming water temperatures. In contrast, the spring-run rainbow barely emerge from the gravel when the streams begin to show the effects of the critical summer season (flooding, irrigation return water and high water temperatures). Because of these factors, the bulk of the rainbow trout production in the spawning streams, especially Nine Mile Creek, occurs from the fall run. This is the reason the prime spawning areas in Nine Mile Creek are closed from October 1 through December 31. Although spawningcan beobserved periodically from November through April, the most active period and best hatching success occurs before January 1. Stream studies conducted by theGame and Parks Commission in Nine Mile Creek during the months of January and February indicated that approximately 72 percent of the rainbow trout had already spawned by that time.

RAINBOW: Managing the Streams

CHANGES IN rainbow trout management were made during the first years of the rainbow trout investigations. Hatchery origin rainbow stockings in the North Platte Valley spawning streams were ended after 1967. This change came because hatchery trout were not increasing the number of 3 to 4-pound rainbow returning to the streams to spawn. Beginning in 1962, all hatchery rainbow trout were marked prior to stocking in spawning streams. Only a few were caught by fishermen, and even fewer survived to a large enough size to spawn. They did not survive because they could not adjust to the adverse environment that exists in the spawning streams during the critical summer months and they didn't have the instinct to migrate into Lake McConaughy. In addition, these 6 to 9-inch trout were competing with the 1 to 2-inch natural-reproduction trout that were present in the spawning streams during the spring. During 1967 the emphasis was shifted from hatchery trout to stocking fingerling trout hatched from Lake McConaughy rainbow trout eggs. The McConaughy rainbow were genetically better adapted to the North Platte River drainage and when stocked, survived better, migrated to the reservoir, and returned as adults to spawn. Because of their superior performance, a stocking program was initiated for all the trout streams in the North Platte River drainage that did not support natural reproduction of rainbow trout. This program was started in 1968.

Land surrounding approximately 1 1/2 miles on the upper end of Nine Mile Creek was purchased by the Game and Parks Commission in 1969. Since that time this area has been managed as a wildlife area with emphasis on good stream management.

The misuse of dip nets by some anglers in the spawning streams caused a change regarding their use. Since 1974, anglers have been prohibited from using landing nets in tributary streams of the North Platte River located in Keith, Garden, Morrill, Scotts Bluff and Sioux counties.

Fishery investigations in Red Willow Creek indicated that a substantial number of juvenile and adult rainbow were lost down an irrigation canal on their annual downstream migration to the lake. To prevent this loss a rotary screen was designed and installed in 1975. This screen stopped the loss, and it will be operated during downstream migration periods when water is being diverted.

One of the most significant accomplishments of the rainbow investigations in the North Platte Valley occurred in Otter Creek, a stream flowing directly into Lake McConaughy. The trout population since the mid 1950's had been nearly nonexistent in this stream, and spawning habitat was in very poor condition. Livestock in the upper end of the creek kept the stream banks barren of vegetation. Bank erosion was extreme and the stream became wider. Hard rains in the headwaters would wash sand from thesurroundinghills into the stream. Very few pools or resting areas existed in the upper reaches of Otter Creek. The gravel riffle areas were either periodically or permanently covered with drifting sand.

A decade ago, four North Platte Valley streams

were producing rainbows. As a result of wise

management, eight new streams were added

A decade ago, four North Platte Valley streams

were producing rainbows. As a result of wise

management, eight new streams were added

Starting in 1969, land in the head-waters was leased by the Game and Parks Commission. A fencing project removed livestock from the leased land. This unproductive stream with poor habitat was transformed into one of the major rainbow producing streams in the North Platte Valley within three years. Vegetation quickly returned to the stream banks. The average width of the stream was decreased in places. Untrampled stream banks quickly stabilized, providing protection and resting areas for trout. More important, however, fencing protected the watershed from flooding and sand no longer drifted in to smother the gravel beds. Deep pools and clean gravel quickly appeared in the stabilized stream. The water temperature during the critical summer months was reduced 2 to 5 degrees; another benefit of stream fencing. In 1969, Lake McConaughy rainbow eggs were collected, hatched, and the fingerlings were stocked to start a rainbow spawning run in Otter Creek. They migrated to the lake and returned to spawn in 1971. And, due to the fencing project, these trout were able to spawn successfully when they returned. When natural reproduction was confirmed in 1971, stocking was terminated. Today, Otter Creek has a self-sustaining rainbow trout spawning run.

Rotary screens, like the one on Red Willow Creek (far left) are used to prevent trout from diverting into irrigation canals. To provide native fish for stocking, biologists collect eggs, (top left) and milt (middle left) from mature female and male trout during their spawning runs. The eggs and milt are mixed and fertilization takes place. After five minutes the fertile eggs are placed in screen-bottomed boxes and washed with clean, cool water in large tanks (bottom left and below). They are immediately transported to a hatchery and then the fry are reared until stockedBy applying good watershed conservation and stream management practices, plus stocking the correct strain of rainbow, trout in Otter Creek changed from nearly zero before 1969 to a high of 20,000, 7 to 10-inch rainbow smolts in 1974. These 20,000, which migrated into Lake McConaughy, make a major contribution to the rainbow trout fishing in the lake.

A decade ago, only four North Platte Valley streams were producing rainbow trout for Lake McConaughy: Nine Mile Creek, Wildhorse Creek, Tub Springs and Dry Spottedtail Creek. Today, as the result of wise management, eight additional streams are productive trout waters. Natural reproduction now occurs in Red Willow and Otter creeks, and the stocking of fingerlings has added Clear Creek, Alliance Drain, Lonergan Creek, Winters Creek, Mitchell Drain and Stuckenhole Creek.

This type of program can be carried out in other streams if cooperation and money are available. The Otter Creek project represents the ideal approach to the management of the rainbow trout fishery in the North Platte River drainage.

RAINBOW: PLANNING THE FUTURE

THE NORTH PLATTE River from Lake McConaughy upstream to the Nebraska-Wyoming line contains approximately 60 miles of coldwater streams capable of supporting rainbow trout. Natural reproduction takes place in about half of these streams. Spawning gravel is not present in large enough quantities to support natural trout reproduction in the other 30 miles of streams. Because of the difference in stream habitat, a management plan was necessary for both stream types.

Nursery StreamsThe 30 miles of streams which do not support trout reproduction were labeled nursery streams because of their growth potential for trout. Nursery streams contain coldwater habitat that will support rainbow trout once past the critical in-gravel stage. These streams are usually less than eight feet wide and are located in the upper end of the drainages where

Many nursery streams stocked with Lake McConaughy rainbow progeny have proven to be excellent production areas. In the nursery streams, McConaughy fingerlings grow to smolt size (7 to 10 inches) in approximately one year, and then migrate to McConaughy. The smolts migrate from the nursery streams in early spring, leaving these streams practically barren of fish. These same streams later that spring are then restocked with rainbow fingerlings. This is an ideal situation because the newly stocked rainbow have little competition from other fishes.

The objective of the rainbow trout management plan for nursery streams is to collect 200,000 Lake McConaughy rainbow trout eggs yearly. Each female produces approximately 3,300 eggs, so about 60 females will be required to produce the required number of eggs. The 200,000 eggs are necessary to raise 1 50,000 fingerlings to a 1 to 2-inch size. If the Lewellen trap is operated, it will be only for a short period (less than two weeks) until enough rainbow are collected to supply eggs for the program.

The 150,000 fingerlings will be stocked in the nursery streams. Stocking rates should be approximately 5,000 per acre of water. Survival in the nursery streams from stocking until the downstream smolt migration one year later usually ranges between 15 and 30 percent. This means that 150,000 fingerlings stocked in the nursery streams will result in Lake McConaughy receiving between 22,500 and 45,000 rainbow smolts each spring in addition to all the 7 to 10-inch natural reproduction trout that also migrate to the reservoir. If, however, the nursery streams are stocked too heavy, the survival and growth rates will be low and fewer rainbow will migrate into the lake.

This fingerling stocking program benefits both the lake and stream angler. Once the smolts migrate into Lake McConaughy they are available to lake fishermen for nearly two years. These same rainbow are then available to stream fishermen during their spawning journey. Even by the time these rainbow have returned, they have served their purpose. Many have been caught, and the ones that haven't may move to other streams to spawn. Nursery stream stocking is superior to both a lake stocking or a catchable (7 to 10-inch) rainbow stocking plan in the spawning streams. Lake stocking benefits only lake fishermen. Stream "catchable" stocking would help only the stream fisherman, if it did that. Besides, catchable stocking, whether in the lake or in streams, is very costly, and under the present hatchery system, facilities are not available to raise the number of trout needed.

Natural Reproduction StreamsThe 30 miles of streams which support rainbow trout reproduction involve a different management approach. The main objective in these streams is to preserve and enhance the trout spawning by providing the best stream habitat possible.

One of the most effective ways to meet this goal is to remove livestock from bank areas. If extreme flooding and fluctuating water levels continue to exist, however, then benefits of livestock removal are diminished. Under normal conditions, however, if grazing can be removed, trout production can beeasily increased 50 percent.

The principles used to restore Otter Creek apply equally in the rest of the North Platte Valley streams. Heavily grazed stream banks are continually being trampled and eroded. This accelerated bank erosion causes streams to widen. The wider the stream the less the water velocity. Water velocity is very important to trout, especially in Nebraska. High water velocities help keep the gravel riffle areas washed clean of silt. The gravel riffles are not only important as spawning areas but also provide most of the trout's food. Slow water also warms up much faster. This is an important consideration because water temperatures in most Nebraska trout streams during the summer months are near the maximum that rainbow can tolerate. Prolonged water temperatures above 75°F is fatal for them, and every effort should therefore be made to keep stream temperatures below 75°.

The important diversity between pool and riffle areas is sometimes lost with reduced stream velocities. Flooding can cause the same problem. Stream bottom and water depth in many Nebraska streams remain nearly the same, offering little diversity.

Overhanging stream-bank vegetation, besides stabilizing the banks, provides protection and hiding areas for trout. The quality of a trout stream in many instances can be judged by the appearance of its banks.

Landowners interested in improving streams on their property, whether in the North Platte Valley or in any other part of the state, should contact the nearest Game and Parks Commission office or employee. Technical assistance and, in many instances financial assistance, can be given to protect one of Nebraska's finest natural resources —its streams.

RAINBOW: STRATIFICATION AND STRESS

A VERY IMPORTANT part of the North Platte rainbow trout studies was to understand what water conditions the rainbow trout population was subjected to in LakeMcConaughy during the summer months. Much was learned about theannual temperature and oxygen cycle.

From ice break-up in the spring until early June, the water temperature and oxygen content from the surface to the bottom of the lake remains the same because of slow warming and the mixing action of the wind. The calm, hot days of early summer cause the surface water to warm faster than that in the middle or bottom of the lake. Since water density changes with temperature, the cooler waters in the depths of the lake form a thermocline, consisting of water considerably cooler than at the surface. The thermocline prevents surface water from mixing with that at the lake bottom. As summer progresses, oxygen in the water below the thermocline is slowly used up by decaying organic materials. This water is cold enough for trout, however, by mid August or sooner, not enough oxygen is available to support fish life. While this is happening below the thermocline, the waters between the thermocline and surface are warmed and mixed by wind as summer progresses.

By mid August, the coolest water remains only in the area of the thermocline, right above the water devoid of oxygen, and below the warm surface waters. Theoretically, the trout also are "sandwiched" in this small area. If "trout water" is defined as water 70°F or cooler, yet containing at least 3 parts per million oxygen, then during August the volume of water meeting this criteria is very small. In some years "trout water"

During September, the surface waters begin to cool and the thermocline sinks lower in the lake. During early October, the surface waters have cooled to about the same temperature as water near the bottorn of the lake. When this happens, the density of the surface waters and bottom waters are nearly equal and the entire lake begins to mix. This period is called the "fall turnover." The lake continues to cool and be mixed by winds until freeze-up in December or January.

Two factors wiil influence the amount of coldwater habitat in Lake McConaughy. The natural aging or eutrophication of the lake is influenced by the activities of man. The lake will reach a point where the organic materials and heavy loads of nutrients, through complicated cycles, eliminate the coldwater habitat. It is anybody's guess when this will happen. The second factor that will influence the capability of Lake McConaughy to support rainbow trout is also controlled by man —the water level of the reservoir. If the demand for water dictates extremely low lake water levels, then the rainbow population will expire accordingly. As in the case of eutrophication, at what water level the rainbow will disappear is hard to determine. However, the smaller the lake, the warmer the water will get during the critical summer period.

If the waters in Lake McConaughy become too warm and the oxygen too low to support trout, some of the rainbow may attempt to leave the lake via the outlet structures. Unless water quality conditions change drastically, a massive, spectacular summer kill of rainbow may not occur. Rather, the rainbow population will slowly decrease in numbers as the coldwater habitat diminishes.

RAINBOW: CROPPING THE SURPLUS

Experience and knowledge of the trout's habits and habitat are characteristics marking the successful rainbow fisherman

BETWEEN THE STREAM fishermen and lake anglers, the North Platte Valley rainbow trout population provides year-around fishing. Although fishing pressure is heavy, it is probably the stream and lake habitats rather than the angler that determines the size of the rainbow population.

Experience and knowledge of the waters favors the good trout angler. For instance, in the lake during the summer, down-riggers or similar devices that control precisely the trolling depth are very beneficial. Flatfish, Thinfins and large spinners are popular trolling lures. In later summer and fall, rainbow can be taken on the surface by locating schools of shad on calm days. Bank fishing for rainbow is best early in the spring along the dam and rocky areas. June, July and September are the months fishermen report the most Master Angler rainbow (verified catches over 5 pounds) in Lake McConaughy.

Most anglers troll for trout, using lead-core line, diving planes or down-riggers to get lures down into trout water. Depth depends upon time of year, temperature and other factors, but much of the summer it is deep — often 40 to over 60 feet.

It may be a matter of trial and error, working until one is landed and then concentrating on that water depth. At any rate, locating the trout seems to be the major problem of the reservoir angler.

Stream fishermen, however, have a different problem. They can be certain that fish are present in the water they are fishing, as they can usually see them when they cross shallow or clear stretches of water. The problem in this situation is getting fish to hit.

Rainbow spawners seldom feed while in spawning streams, as they apparently have other things on their mind. Yet, a good number of them are caught, and many fishermen believe it is a matter of irritating the trout until they strike in frustration.

The most popular bait used is rainbow eggs. These are placed in a piece of nylon or cheesecloth and formed into about one-half-inch balls. This "bal I of eggs" is placed on a hook and fished in large holes, either moving it along with a flyrod or letting it bounce along with the current. A gob of worms is the next best bait, with spinners bringing up a very weak third.

Stream fishermen have the best luck when rainbow first enter the spawning streams, consequently November and March are the top months. The precise time rainbow move into each stream varies by season. Here again, experience favors the good angler.

The North Platte River above,Lake McConaughy offers rainbow fishing that has not been utilized by many anglers. Float-trip fishing or fishing the deep holes is difficult but productive.

Nearly all the streams in the North Platte Valley are privately owned, and the sportsman respects the law and obtains permission before fishing.

Quality rainbow fishing will continue only as long as the trout habitat remains. Sportsmen, irrigation interests and landowners must find an acceptable area of compromise in the North Platte River system or the rainbow will perish because of adverse environments. Help Nebraska trout streams —speak out for clean waters and good stream habitat.

SAFETY WHEN IT COUNTS

Bough water is common on Nebraska's reservoirs, and knowing how to handle your boat and yourself can mean the difference between grim hardship and an easy trip

NEBRASKA'S RESERVOIRS are a great source of recreation, but even fun must be tempered with common sense for the benefit of all.

And, safety is one of the primary considerations when using a boat, as it means that people are out of their element, and there are hazards involved. Yet safety is seldom part of the planning, and only the required equipment and steps are taken.

Reservoirs are notorious for becoming too rough for a small boat —often in a short period of time* Even a relatively gentle breeze can be amplified by long, open stretches of water, with good sized waves generated in the process. Often, embarking upon a fishing expedition in the calm of early morning makes people oblivious to gradually increasing winds later in the day. Then, the boat may be a considerable distance from the dock or trailer, and a very real danger may exist just trying to get off the water.

Being familiar with the boat and its capabilities of riding out rough water helps, but the only way to become familiar with it is to be out on rough water. That can be a difficult lesson.

In most cases, common sense will speak up loudly when the weather gets too bad to be afloat, but even then there are circumstances when that doesn't help. A disabled craft or sheer distance from shore may present special obstacles.

It is at such times that life preservers become of utmost importance. Whether considered a nuisance or not at all other times, it is under adverse conditions that they become necessary, and when they are worth all the trouble at other times.

Finding yourself in a bad situation, the first step would be to buckle on a preserver. Many folks wear life jackets at all times, and although the law doesn't require it except for children under 12 years of age, it is a sensible practice.

Depending on conditions, good boat handling can save a lot of grief. Normally, heading as nearly into the waves as possible is the best course to follow. But, if the waves are so high they break over the bow and could fill the boat, it is a mistake. Under those conditions, the boat should be quartered into the wind and waves until an angle of navigation is possible without shipping too much water.

Except for the danger of capsizing, most boats will JUNE 1976 also ride parallel with the waves, riding the crests and dropping into the troughs. Depending upon conditions, travel is then possible going at a right angle until shore is reached. It is advisable under this procedure to lower the center of gravity as much as possible —having all passengers get into the bottom of the boat to allow the craft to perform its best. Capsizing is most likely when sideways to the waves.

Depending upon the boat and the distance between waves, it may also be possible to go directly or nearly so, away from the wind. Momentum must be maintained, however, or water will usually come over the transom as the boat bogs down in each trough. By keeping moving, you stay just ahead of the waves, riding at the same speed much like surfboarding.

A slow traveling speed is normally best under any rough-water conditions, whether going with, away or diagonally with the wind.

Perhaps the most dangerous situation is if the motor cannot be operated. In this case, the wind and water are going to turn the boat all around, inviting water aboard. In extremely rough weather, the best procedure is to put out the anchor to keep the bow into the wind. If the anchor is on a long rope, it will probably hold the boat in position.

And, that is not always desirable, especially if shore is in reach. Then, it is best to put the anchor on a short line, just barely touching bottom. Then, each time the boat is lifted on a crest, it will drag the anchor a bit, gradually moving the boat. Or, a passenger can operate the rope, letting the anchor drag only enough to keep headway, but lifting it off the bottom to allow more movement.

A sea anchor serves the same purpose —providing sufficient drag to hold the boat's position, but not enough to restrict movement. Even an ice chest may be used, tying it off the bow.

At any rate, even if the boat capsizes, it is best to stay with it. Nearly any craft will stay afloat enough to support several people in the water, and it can then be slowly pushed ashore. It might be necessary to drop the engine off. The important thing is to stay afloat, and a life preserver really comes in handy for that.

Knowing that you are at least partly prepared for unexpected bad times can help considerably in enjoying the good times, too. Ω

35

THE WILDERNESS ETHIC

TIMES HAVE CHANGED, and somewhat unfortunately, so must people if what little wilderness remains is to retain its unique character for those of the present and future to enjoy.

Since the days of pioneer trappers and explorers, when living in the great outdoors was a continual struggle to survive by conquering nature and using the resources to work for themselves, wilderness has shrunk. No longer are there vast tracts of untouched lands. Virtually every foot of the continent has been tamed, and much of it has been pillaged or converted to a "foreign" use by the vagaries of our modern way of life.

Modern outdoor enthusiasts have 36 far more responsibility to nature than those explorers, as they must now consider the impact they make. In fact, today's wilderness will remain wild and unspoiled for future generations only if it is protected and cared for by each and every visitor.

Various groups concerned with this matter, including the Sierra Club, have developed a Wilderness Camping Ethic which is a true code for outdoor living aimed at preserving the wild country. Some of the measures outlined seem extreme, yet in most areas it is absolutely necessary to take the utmost care or destruction is inevitable —and nearly permanent. It takes many generations to restore damage caused by fire, for example, or the cutting of trees. Pollution and littering are senseless and destructive, and have varying impact depending upon the situation.

It is stressed that there should be a deep sense of satisfaction and personal achievement in the knowledge that one has camped in and traveled through an area without leaving any perceptible trace —which is the spirit of living in harmony with the wilderness.

Here, then, are some suggestions for how to experience the outdoors without "hurting the one you love."

CAMP LOCATIONSSet up camp where foot traffic does the least damage to fragile vegetation —never in meadows, preferably in sandy or rocky areas. Minimize building, whether for kitchen facilities or bed sites. Don't disarrange the natural landscape with hard-to-eradicate ramparts of rock for fireplaces or windbreaks. Rig tents by tying ropes to rocks or trees. Never cut boughs or put nails in trees. Avoid disturbing the soil with hollows or trenches — locate shelters so that water drains away naturally. When breaking camp, erase all evidence that you were there.

FIRESEfficient fuel stoves should be used whenever possible. They are clean, fast, dependable and normally safe. Several types are available, including white gas, butane, propane, alcohol, sterno and kerosene burners. There is little need for campfires, as proper clothing and sleeping gear eliminate the excuse that a fire is needed for warmth, and when a focal point is desired for comradeship, use a small candle. When a fire is an absolute necessity, collect small sticks from areas away from the campsite, use only fallen wood, and keep the fire as small as possible and scatter the remains when it is co mpletely dead.

CAMP TOOLSWhen attuned to the spirit of modern camping, such utensils as axes, hatchets, saws, shovels and machetes are not only unnecessary, but potentially destructive. For most purposes, a small sheath or folding knife will suffice for all camp chores such as cutting and peeling. The idea is not to see how much timber can be cut down, so use the large implements only to fight fires or in an emergency situation. Use rope instead of nails or notches or stakes. Use a ground cloth instead of a tableorchairs, and you'll enjoy the simplicity.

CLEAN-UPIn most cases, garbage should be carried out rather than being buried, as excavations are subject to erosion and can attract animals to dig them back up. Burn everything that will burn, clean °ut the fire and carry out everything else-cans, bottles, etc. Edibles may be scattered thinly, out of sight and away from camp ot trails, where they will decompose or be consumed by birds or animals. Actually, there should be little garbage if the trip was carefully planned and meals are prepared properly. Fix only enough food for each meal and there will be no leftovers to deal with. Leave the campsite cleaner than you found it, make every trip around camp a clean-up trip, and on the way out, offer to carry out other people's trash as well... may be they will get the hint to aiso practice the code.

TRAVELStay on established trails if they are present. Cutting corners or across switchbacks breaks down trail edges to start erosion, and can dislodge rocks and vegetation. Restrain the impulse to blaze trees, build markers or leave other signs. Let the next hiker find his own way ,as you did.

BATHING, SANITATIONDo all bathing and washing of dishes well back from the shores of lakes or streams in a bucket or basin. Swim away and downstream from camp. Prevent pollution by keeping all soaps out of the water. Soap is preferred even to a biodegradable detergent, which may leach into adjoining drainage. Bathing should be done by lathering and rinsing away from open water before taking a final dip. For a latrine, select a site at least 50 feet from open water. Dig a hole about 8 inches in diameter with a heel or trowel, and no more than 8 inches deep, to stay within the "biological disposer" layer of soil. Save the sod and replace after use. Burn any paper and replace the dirt and sod.

BED SITESAvoid digging or leveling if at all possible. Try to find a flat and sheltered area, and if materials must be moved, such as rocks, replace them when you leave.

MISCELLANEOUSCatch only as many fish as you can eat, and clean them away from eating areas and water. Conceal entrails —do not throw back into the water. Avoid using pressure-type lanterns as they scorch trees and foilage if hung up. It is best to avoid artificial lights, relying instead on completing chores during daylight and enjoying the natural qualities of darkness and night. A small flashlight is adequate for moving around at night. Be a considerate neighbor at all times, even when you have no neighbors. Don't crowd other camps or sleeping areas if they are present. Noise is not in harmony with wilderness. Radios are likewise out of place. Learn to read the weather and anticipate changes for yourself. Also, smoke only in camp and at stops, never when traveling. Then field strip and put completely out.

The tenets of the wilderness traveler's creed are that man —an intelligent animal—can travel the wilderness and leave no trace. Keep groups small; do not stay in one place long; do not cut trees or branches; do not build fires; leave no trash or other evidence —leave no trace.

Many people do not appreciate the fragile nature of nature. While it is capable of withstanding natural fires, storms and wind, the careless hand of man can be extremely damaging. Modern developments are the most serious threat, as greed usually usurps good judgement to everyone's detriment.

Developed parks are extremely valuable, but they are not nearly extensive enough to handle the demand for open spaces. It is the wilderness areas —those regions not scraped and scarred and leveled and mined that must be preserved. Once destroyed, and tamed, they are irreplaceable. Fortunately, more and more people are coming to realize that all effort must be made to preserve natural places. The cost is small, yet the benefits are incalculable. Ω

37

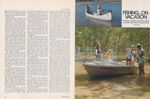

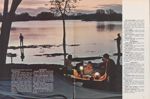

FISHING...ON VACATION

Fishing, vacation activities make natural combination for good time

IN JANUARY and February, it's ice fishing. Then, there's the rainbow trout run in the Panhandle in March, walleye along the dams come April, and bass in May.

By the time June rolls around, the hard-pressed angler should be just about ready for a break, or at least a change of pace. And what better way is there to relax than a leisurely Nebraska vacation, with a little camping and fishing, or perhaps some sightseeing and fishing, or maybe tours of historical parks, museums and the like combined with a bit of fishing?

In fact, a summer vacation with family and friends can be among the most rewarding of fishing experiences, especially for the hard-core, dedicated angler. On a Nebraska vacation of a week or more, there need not be any of the pressure to put in a lot of time on the water as there might be on an outing devoted exclusively to fishing. And, there's no need to rack up a lot of miles and spend a lot of cash hurrying to one of the distant and traditional tourist traps that are the goals of hordes of other vacationers.

The summer vacation is also the perfect opportunity for the angler at the other end of the spectrum —the now-and-then fisherman who gets out only once or twice a year. Whether red hot or luke warm on the sport, including fishing in your vacation plans (or including vacation in your fishing plans) gives another dimension to the trip that's sure to be worthwhile.

If you stop and think about it, there are a lot of things to do, places to go, and sights to see in Nebraska that offer fishing opportunity in the area or on the way. History or antique buffs, for example, can gawk at relics to their heart's content travelling Interstate 80 and the Platte Valley. There's Stuhr Museum, House of Yesterday, Pioneer Village, Fort Kearny State Historical Park, Fort McPherson National Cemetery, Buffalo Bill Ranch State Historical Park, and Ash Hollow State Historical Park.

Paralleling the route is the 1-80 Chain of Lakes, beginning with Mormon Island State Wayside Area at Grand Island with a couple of lakes 38 with good (though rather wary) bass populations. In addition, the Tri-County system of lakes also lies nearby, with Johnson Lake, Lake Maloney, and Sutherland Reservoir the best of the lot. And, at the western end of the line lies Lake McConaughy, probably the top fishing hole in the state.

Other combinations are also possible. Campers in Nebraska have it made when it comes to fishing, since nearly all of the best fishing waters have at least one campground on their shores. The Platte Valley lakes offer many choices, although the campgrounds and lakes can become a bit crowded at the peak of the season and on weekends.

Another camping-fishing possibility parallels Nebraska's southern border—following the Republican River Valley and reservoirs there. Harlan County Reservoir provides good walleye fishing through most of June, white bass fishing later in the summer, and catfish nearly all year. It's much the same story for Medicine Creek and Swanson reservoirs, while Red Willow Reservoir offers good crappie fishing and fine bass angling for the experienced angler. Other smaller lakes in the region offer good fishing, too, combined with a quieter, more relaxing atmosphere.

Canoeists also have built-in fishing opportunities, particularly if they select the proper stretches of water. The Missouri River above and below Lewis and Clark Lake is good for experienced canoeists in years of normal water flows, and it offers some fine walleye, sauger and other game fish. But, abnormally high water releases from dams upstream can make that stretch troublesome for canoeists, so it is wise to check before embarking on a trip.

Some stretches of the Platte, Elkhorn, Republican and Loup rivers offer both good canoeing and good catfishing, although it may be a bit late this year to find enough water to float the craft. But, these and other rivers bear consideration for a springtime outing next year.

Hikers and backpackers also have some fishing opportunities, though these are more limited. The trout streams in north-central and northwest Nebraska are generally located in the kind of scenic and remote country that hikers like. With a little scouting beforehand, it is possible to line up permission from ranchers to hike across their property and fish their streams. In a very few instances, such opportunities are available on public land in state or federal ownership. Trout streams with public access include Soldiers Creek on the James Ranch Special Use Area and Fort Robinson Wood Reserve above Fort Robinson State Park. There is also Pine Glen Special Use Area on Long Pine Creek. The area is small by hiker and backpacker standards, but it does provide access to trout water and nearly 1,000 acres of splendorous countryside.

Another relaxing way to while away a vacation is to pick just one locality with some interesting activities and stay put there for a week or so. Merritt Reservoir, for example, can serve as a base of operations for such a stay. Campgrounds on the reservoir or cabins and motels in the area provide a place to stash your duds for a few days while taking a look around.

The Snake River Falls below the lake, and a section of the river are open to visitors for a modest fee. The Valentine National Wildlife Refuge nearby offers chances for sightseeing, wildlife observation and good fishing action. Broods of young ducks and geese should be following proud parents around, and other critters and their young should also be apparent. Fort Niobrara National Wildlife Refuge to the northeast is also well worth a visit, with its bison, longhorns, elk and other animals. And, canoes are available locally for a day's float trip down the scenic Niobrara River.