NEBRASKAland

May 1976

NEBRASKland

VOL. 54 / NO. 5 / MAY 1976 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Fifty cents per copy. Subscription rates $5 for one year, $9 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKMand, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. commission Chairman: Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 Vice Chairman: Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-Central District, (308) 745-1694 2nd Vice Chairman: Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-central District, (308) 452-3800 H. B. "Tod" Kuntzelman, North Platte Southwest District, (308) 532-2982 Richard W. Nisley, Roca Southeast District, (402) 782-6850 Director: Willard R. Barbee Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, Jr. Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: Jon Farrar Greg Beaumont, Ken Bouc, Contributing Editors: Bob Grier Faye Musil, Tim Hergenrader, Roland Hoffmann, Bill Janssen, Ben Schole Art Director: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff G riff in Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commision 1976. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska MAY 1976 Contents FEATURES FOR FUN AND FISH 6 WEEKEND IN THE SADDLE 8 FISHING BEST TIME FOR BASS 14 THE WILD TURKEY IN NEBRASKA A special 18-page all-color section focusing on the Merriam's life history 18 THE FIRST TOM IS THE HARDEST 35 A RIVER AND ITS PEOPLE 36 PRAIRIE LIFE/PLANT SUCCESSION 38 DEPARTMENTS SPEAKUP 4 TRADING POST 49 COVER: Springtime fishing is a noble pastime for man and boy, no matter what part of the state. Jason Schiictemeier gives it a try during weekend outing. Story on page 8. (214 relex with 250mm at F8) Photo by Bob Grier. OPPOSITE: The long, ribbon-like leaves of broad-fruited bur-reed sweep the surfaces of Nebraska marshes and waterways. During May, the bur-like female flowers and clustered male flowers are evident. (35mm with 100mm macro). Photo by Jon Farrar. 3

Speak Up

Sir/I want to thank you for your Bicentennial issue of NEBRASKAland, Portrait of the Plains. It was the best piece of work put between two covers that I have ever seen.

Looking through this issue, you notice some of the beautiful scenes we take for granted in Nebraska. Portrait of the Plains shows us what a great state we have and how proud we should be of it. Thanks again.

Steve Will Harvard, Nebr.As It Should Be

Sir/After living in New Jersey for four years and having Bicentennial done and redone to the point of oversaturation, your January "Portrait of the Plains", at last, is a salute to the nation and to our state as it should be.

"Portrait" brings us back to the land, the flora and fauna, our very unpretentious existence.

In the Tri-Centennial, "Portrait" will still be pertinent. How perfect to picture Chimney Rock on the cover. It was there 200 years ago when the Indians loved the land; it will be there 200 years in the future for those who will love it then.

We greatly enjoy receiving NEBRASKAland while we are away. We enjoy the paintings by Neil Anderson and expect to hear more about him as an outstanding wildlife artist.

Please continue your excellent work and help keep Nebraska a "living" state til we can return to it.

Patricia Kempkes Browns Mills, N.J.Thank you for your letter, and weTI do all we can to carry on. (Editor)

Surprise!Sir/We have just received Portrait of the Plains. Congratulations, it is a beautiful book and should surprise any subscriber. 4 We would like to order some separate copies so we could send them to my relatives and friends in Switzerland. I am a native of Switzerland, though Nebraska is my home state where I became a citizen in 1960 and I am proud of it and always will be.

We are subscribers and enjoy the magazine for years —also donate the magazine for years to the Omaha Home for Boys.

Mrs. Ora Sindelar Clovis, Calif.The Hunting Parson

Sir/I received my October NEBRASKAland with the letter from Mrs. Griffith of Carleton, and it ought to tell us who hunt to appreciate the farmer and his land. I hunted in South Dakota last year and then went to Sherman Reservoir near Loup City. We had a wonderful time. My wife and I met the friendliest folks, and are looking forward to returning this year. I have always made it a practice to stop at the farm house and ask permission to hunt, and then ask what areas I should not hunt in. I have been refused permission, and I respected that person's decision because I own land in Michigan. Last spring I spent a month making maple syrup, and this fall I will stop at all the farm homes that let me hunt and say hello, and give them a half gallon of pure maple syrup for their pancakes this winter. I am also taking some along for new friends I hope to make.

So please tell Mrs. Griffith that if I come to her house, I will drive in and come to the door and ask. I would hunt only where she says I may. I will leave no trash on the land, or bring a gang with me. And, I will guarantee there will be no hen pheasants in my rig. I can sympathize with her, but certainly all hunters are not like those she described. Sometimes when we expect the worst, it happens; and when we look for the better things, they happen.

Rev. Bernie Griner Karlin, Mich.I agree that we often see bad happen if we look for it, and too many people have gotten conditioned to look only for the bad. Most Nebraskans are extremely friendly and cordial, and I hope that you continue to encounter only those. Happy hunting. (Editor)

* * *Toughen Penalties

Sir/I heard on the radio the Game Commission is thinking of raising the license fee for hunting and fishing.

Nebraska is the highest in the nation for resident license. Why don't they make the penalty for poaching and over-bag limit much higher? This way, the people who buy a license and stick to the law don't get penalized. This is our sport —don't drive us to hunt in our neighboring states!

Ray Vondracek Omaha, Nebr.

It's a good idea to toughen penalties for violators, and probably to put the money into management rather than local school districts. But the proposed license fee increases are for our, the hunters' benefit, and we must be willing to pay more for our sport than we did in the good old days, just as penalties should be updated. (Editor)

* * *For the Birds

Sir/I read that the proposed habitat stamp would be required for deer and antelope hunters, also. I believe that is very unfair and improper. The habitat for deer and antelope cannot be improved or new habitat acquired.

If so, how can the big game habitat be improved? There is more and better habitat for antelope now than during the last antelope season at the beginning of the century. Many cultivated fields have reverted back to prairie, cactus and yucca since the homestead and Kincaid days without a habitat stamp fee. The deer need no more habitat with the present good hunting management. The habitat stamp is an excellent idea for improving habitat of pheasant, quail and waterfowl, but should only be paid for by the hunters of upland and water birds, exactly as the old upland bird tax was assessed.

Frank Tesar Omaha, Nebr.

While deer have adequate habitat in most areas of the state, access to land is getting tougher, and part of the idea of the habitat plan is to provide public lands and leases on private lands where possible. All hunters will benefit from the plan, as no segment is being favored over another. Any improvement in one also tends to benefit all others, and certainly hunters should be sticking together. (Editor)

* * *Snake Observer

Sir/I enjoyed your last issue about rattlesnakes. I have fished and hunted all my life. About a year ago I was coming home from fishing above Arcadia in the canal. I started up a high sandy bank with fishing tackle in one hand and a plum stick in the other, and saw a loosely coiled yellow snake about three feet long. I lifted him out of the way with my stick and started up the bank again and it coiled and struck at me. I then noticed he had a viper shaped head but no rattles. I hit it two or three times with my stick and went on home. I was glad to read what kind it was from NEBRASKAland.

Curt Blakeslee Arcadia, Nebraska NEBRASKAlandINLAND SHORES MARINAS, INC.

Located on the North Shore of Branched Oak Lake-One-Stop Service Restaurant-Ice-Groceries-Fishing Tackle -Live Bait-Boat Rentals-Public Boat Ramp-Slip Rentals-Public Docking- Bank Storage-Boating Equipment -Gas-Oil-Light Marine Service -Jobber-Wholesale-Retail Off-Sale BeerJ'S OTTER CREEK MARINA

NORTH SIDE LAKE McCONAUGHY HWY. 92-OPEN YEAR AROUND ALL MODERN MOTEL CAFE BAIT TACKLE GAS BOAT RENTALS HUNTING & FISHING LICENSES CHRYSLER BOATS MOTORS SALES SERVICE ON & OFF SALE BEER •LAKE VIEW FISHING CAMP

CABINS • MODERN CAMPING • MARINA Center-South Side Lake McConaughy Everything for the Fisherman Pontoon, Boat and Motor RentalsNEW INVENTION FOR FISHERMEN

The SENTRY ROD HOLDER®

IDEAL FOR CATFISH AND CARPThe Commonwealth now pays oven higher interest rates!

6.25% Passbook Savings 6.54% Annual Yield Comp. Daily 6.75% 1 Yr. Cert. 7.08% Annual Yield Comp. Daily 7.00% 2 Yr. Cert. 7.35% Annual Yield Comp. Daily 7.25% 3 Yr. Cert. 7.62% Annual Yield Comp. Daily 8.00% 4 Yr. Cert. 8.45% Annual Yield Comp. Daily A substantial interest penalty, as required by law, will be imposed for early withdrawal.

FOR FUN AND FISH

Like casting bread upon the water, a flyrod will return many times the cost in excitement and pleasure. Few methods of angling can match the thrill of landing even a small fish, and learning is not all that tough. Give it a try this summer!

EVEN IN MID SUMMER, when the fishing doldrums set in and most anglers have given up on their weedy fishing hotspots in favor of an easy chair and iced drinks, there is still hope. All you have to do is put on your waders and try a little topwater action for bass and bluegill.

Few outdoor experiences can match the excitement of a good bass smacking a topwater popper. And, that same popper in a smaller size can be just as effective and a lot more fun when fished with a fly rod. Even a 3A-pound bluegill can put a healthy bend in a long and limber fly rod, yet this same outfit is capable of landing the biggest bass in the state if it's handled properly.

Too hard to learn to use one, you say? Baloney! A fly rod is just as easy to learn to use as any other fishing outfit and a lot more fun.

Many anglers would like to learn fly casting and maybe have even gone as far as buying an outfit, but have given up because they couldn't cast a line. Many prospective fly rodders get discouraged at this point and give up, but that's a mistake. Fly casting isn't hard; it just requires a balanced outfit and a little concentration at first to learn the basics of casting.

So stay with me; I'll tell you what to buy, how to cast and where to fish. I won't guarantee you'll catch big fish right away, but if you stick with it, you'll at least catch bluegill and small bass and have a heck of a lot more fun doing it.

EQUIPMENT: The first thing you'll need is a rod. A lot has been written about the virtues of a heavy 9-foot rod, while others say a short, 7-footer will do the job very nicely. True, but a good quality fiberglass rod of 8 to 8V2 feet combines the virtues of both, giving you a rod with the backbone to lay out a long line and yet is easy to cast without tiring you out rapidly. What to buy depends a lot on the size of bug you intend to cast. A heavy popper or fluffy deer hair bug has a lot of wind resistance. It may require a heavy line and therefore a heavier rod than if you intend to cast small panfish-sized poppers.

So, if you plan on casting big stuff, 6 get an 8 1/2 footer. If you want to use the smaller bugs and poppers, an 8 footer will do the job. Cost-wise, you can spend a lot of money and get a really good rod, but a usable rod can be purchased for around $15 to $25.

Buy one with the so-called "slow action" that flexes throughout its entire length, even into the handle. Stay away from "fast tip" or "fast action" type rods. They have a place in fly casting, but they require too much work to cast bugs and poppers easily.

The fly reel is not really critical; its purpose is merely to hold the line. When you hook a bass, you normally play him by hand-stripping line from the reel and applying drag on the line as necessary. A good quality, single-action or automatic fly reel can be purchased for slightly more than $10. Cheaper ones can be had, but you take the chance of a poor quality reel binding up as you're playing a big fish.

Most experts use a single-action reel but a few use automatics. Both reels have their merits but the single-action is lighter and therefore probably balances better on a rod. Beyond this it is a moot point; whichever the angler prefers will work quite well for this type of fishing.

The line is probably the next most critical piece of fly equipment to buy after the rod. To cast properly, get a line weight that is recommended by the rod maker. Most fly rods today are marked with the proper line weight that you should use. If not, an 8-foot rod should handle a No. 6 or No. 7 line, and an 81/2-foot rod should take a No. 7 or No. 8 line. In bug fishing, don't get a line that is too light; it may be better to get one a size bigger to help cast the wind-resistant big ones.

For bug casting, use either a level-floating line or the more expensive weight-forward (WF) floating line. Either one will work, but the weight-forward line will be easier to cast and will carry an air-resistant bug farther. A leader is a necessity with a fly line but bass are not as picky about line sizes and lengths as trout are. A six to seven-foot leader usually is plenty. Tapered ones are best for laying out a bug but they aren't really necessary. If you want to, you can tie your own tapered leaders. Start with about 3 feet of 20-pound mono, 2 feet of 15-pound and about 1 Vi feet of 10-pound. Tie the sections with a blood knot and use a blood knot or nail knot to attach the fly line to the heavy end of the leader.

What's the best flyrod lure for bass? Topwater poppers made from cork or plastic probably work the best. Some bass fishermen use large deer hair bugs that resemble frogs or mice, which are quite effective at times. The smaller poppers are dynamite on bluegill and small bass, especially when fished over shallow spawning areas of the bluegill.

Good popper colors are white, yellow, black and green with a white belly. Try some with feathers, buck-tail or rubber legs. The rubber-legged ones can really be effective at times, especially on bluegill. You can buy flyrod poppers in most tackle stores. Mail-order supply houses are another good source, or you can make your own.

A good pair of waders is a real help in getting away from trees and brush on the bank that might foul up your back cast. In very warm weather you probably wouldn't need them; a pair of old pants and tennis shoes are very comfortable to wade in. A small boat or canoe is good for reaching places you can't cast to by wading. If you don't have a boat, a canvas and innertube float works well to reach the hard-to-get-to backwater areas.

TO CAST: In learning to use a fly-rod, keep it simple at first. The best way to learn is without leader and lure. Find yourself a nice open grassy area so you can cast without hanging up on trees or overhead wires.

Strip out about 25 to 30 feet of line and lay it out in a straight line in front of you. Hold the rod in vour right hand, parallel to the ground and pointing down the line. Take up the slack with your left hand.

Now pull on the line with your left hand and start it moving toward you. At the same time, quickly pull your rod hand upwards, bending your arm at the elbow. (Continued on page 44)

NEBRASKAland

WEEKEND IN THE SADDLE

For the boys, trip would be respite from mowing lawns and haying. For dad, it was simply a chance to ride with his sons

AT FIRST GLANCE, Nebraska's Sand Hills region appears as rolling sameness stretching beyond the horizon, taxing even one's imagination by sheer vastness. From the ribbons of pavement that cross the undulating dunes only at great intervals, the casual motorist can see little of the hills and their hidden treasures of succulent green and sparkling blue.

Turn five youngsters loose on horseback, add a father for guidance and cooking, and the beauty of the hidden valleys and rolling dunes form the backdrop for outdoor adventure and learning.

The idea for a western style campout and ride was met with enthusiasm at the Gary Schlichtemeier residence in Alliance. A native of Crete, Gary shares a love of horses and things western with his three growing sons; Jeff, 12, Chad, 10, and Jason, 7.

Also, two of their friends, Tom Wildy, 12, and Loren West, 12, joined in the trip. It was with no better plan than to enjoy the pleasant weather that the six moved out across the prairie. Only time, and a well provisioned pickup and stocktrailer, separated the riders from similar trips on the prairie of yesteryear. The trailer transported the horses and gear northeast of Alliance, where a group of friendly ranchers opened their land to the riders. Enthusiasm was the game plan, and informal the password.

Camp was located near a sparkling, marsh-ringed lake. On two sides a high ridge of hills defined the limits of a natural hay meadow. The first hours were hectic —gear unloaded, tent set up, and horses cared for.

Tom and Jeff soon slipped away to explore the area, and their entry in the camp journal described finding two lizards, one toad and two mallards, one male, one female.

Each of Gary's boys has a growing interest in wildlife, a byproduct of their dad's career as a wildlife habitat manager for the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Each youngster noted the species in the journal, and an unofficial race for new and varied journal material quickly ensued.

The sandhills were up to the examination. Everywhere signs of new life appeared. Locked in winter's icy grip for a three to four-month period, spring fairly bursts upon the hills as new life and new growth feed on winter's moisture.

The marsh-ringed lake attracted waterfowl and shore birds, and young boys in pursuit of knowledge. Avocets, graceful on awkward appearing legs, stood while the boys tallied their numbers along the shallows of the lake.

Red-winged blackbirds returned the boys' interest with vibrant melodies; a call, once heard, forever remembered as a natural song of a natural marsh, forever a memory of a warm summer afternoon.

The brownish hens of the species jumped from bulrush to bulrush as the youngsters approached, their movement a vain effort to hide the nest held above the water's

surface by cattail fronds.

surface by cattail fronds.

Overhead, the brilliant red and black of the male signaled with his nearly stationary flight that the youngsters were too close to the nest; his shrill warning taken up by the other birds of the marsh.

A hen mallard moved out from the lake to the far shore, flying in an ever widening arc. With a quick maneuver, the hen suddenly dropped and disappeared into a camouflage of grass.

Hidden there by the "tent type" grasses, the mallard had constructed a nest of soft grass and down from her body. Secreted within the soft enclosure were eight greenbuff delicate eggs.

After searching near the camp on foot, the horses were saddled for a ride before dinner, which the journal entry described as sandwiches, cookies and water. A near-by indmill provided the latter.

The six riders had an opportunity to fill in as working cowhands as they helped their rancher friend round up cattle that had moved out of his pasture. After the cattle were turned in, the riders moved leisurely back to camp.

Stew followed by popcorn filled the young riders, and after supper everyone turned in. Tom and Jeff found the stock trailer to their liking while the rest unrolled their blankets in the tent.

One of the most memorable times on any camping trip is the night spent under the stars. Only under the blanket of millions of twinkling lights did the sandhills surrounding camp become insignificant. Looking at the color changes of individual stars and bands of concentrated light, that night formed a bond between each of the six adventurers camped on a small part of a small continent, on a small planet among millions.

Nearby the horses could be heard moving in the dark. A coyote added his forlorn call to the night. Sleeping bags and warm blankets never felt so good.

The morning sun returned the majesty of the Sand Hills with light bouncing from hilltop to hilltop. Golden rays moved down from the hills to push back the purple shadows of the valley. Soon the camp was stirring with activity.

Tom and Jeff rode early and found a dead bull, a reminder of the high winds and heavy snows earlier that spring. The morning's journal also noted many ducks, as well as Chad and Loren finding several snakes near camp.

Before breakfast the horses were cared for by the youngsters —each knowing well that on the prairie a rider couldn't skimp on the care and feeding of his horse. Too many miles of hard walking stood in front of the man who neglected his transportation.

With dad preparing lunch after the morning's ride, the youngsters splashed into the lake, their youthful exuberance and shouts rolling across the hay meadow. A mule splashing youngsters in the lake below. Dad also kept a watchful eye on his crew.

That afternoon, Gary and the boys fished a nearby pond. If it held any fish the boys never found out, but it was a special time for Gary and his sons. Seven-year-old Jason moved close to his father, and sitting there on the grassy bank they formed a memorable picture that would linger long after the disappointment of the fishing was forgotten.

Rain came to dinner that evening, and the tent and stock trailer saw use once again. Outside, the gray sheets of rain whipped across the surface of the lake and up the sides of the high range of hills. The fresh smell of rain on a spring landscape returned with the sun. The boys washed off the alkali from the day's swim in a windmill tank. "Very cold", was the journal's entry.

The evening was a special one for the riders. The rain had cleared the air and everywhere the brilliant green of growing things shimmered under beads of moisture. Moving to the highest hill overlooking the valley, the boys watched the sun disappear behind purple hills to the west.

The journal would forever remain blank about that night, for the boys slept well after the day's activities. Gary alone soaked in the warmth of the day as he sat in the darkening glow before the camp, the steam from his coffee a screen to view again the memories of good times.

Camp was packed away the following morning. Gary made two trips to town, first with a load of horses and then with the boys and the remaining horses. The last entry in the journal noted the finishing activities with a simple, "very tired —very thirsty — went home." Ω

FISHING...BEST TIME FOR BASS

Records, experience show that May is top bass fishing time

Largemouths come in all sizes, but they all have that strange attraction PROBABLY THE BEST time of all is right now; the month of May. At least, you most likely feel that way if you're addicted to bass fishing to any degree.

In most years, May sees the best of Nebraska's large-mouthed bass fishing. It's the time when ol' bigmouth is feeling his sassy best, with his wintertime blues long cured by several weeks of warm water. In May, hungry bucketmouths are busily packing in the chow that makes for much of their annual growth and gives them the reserves to help them through spawning and summer's dog days, when their appetites slacken.

And, in May, eager bassin' folks capitalize on all this activity. Fishermen by the score probe the better public bass waters, and most private ponds and pits host one or two anglers favored by the landowner and allowed in. These fishermen are there in force because they know that, in most years, May will give them their biggest rewards.

Observant fishermen have suspected this for a long time, and statistics of the Master Angler program back them up. In 1975, 102 of the year's 388 trophy largemouths were taken in May. The records also provided information that might be of more practical use to the May bass fisherman, but we'll get to that later.

Without a doubt, the largemouth is the most sought-after game fish in Nebraska and the whole country. Clubs have been formed by those addicted to his pursuit, and big-money tournaments are staged for the best of the pros. In conjunction with this bass mania, a whole array of gear has been tailored for the bassin' man, ranging from small-change items like lures and rods to special, big-muscled boats sporting sophisticated electronic gear and price tags of several kilobucks.

And, for every fisherman caught up in the fast-moving world of clubs, tournaments and big-time paraphernalia, there are scores who quietly go MAY 1976 after the largemouth alone or with a buddy or two, and with little or no special gear or fanfare.

Those nbt bitten by the bass bug might ask what makes this fish so danged special. And, most bass fishermen would jump right up and offer an answer. But, if there were a dozen bass fishermen in the same gathering, chances are there would be about a dozen versions of the largemouth's qualities as a game fish offered as the reason people fish for him.

A look at what makes the largemouth the fish that he is will go a long way toward helping normal people understand those apparently addled folks who pursue him. And, a little review of some basic lore on the largemouth might also help the angler.

For starters, the large-mouthed bass is a pretty good sized customer. Two and 3-pounders are common in Nebraska, fish 5 pounds or bigger are considered trophies, and the state record stands at 10 pounds, 11 ounces. This size, coupled with a pugnacious disposition, make him hard to beat for a sporting fight.

The largemouth is an adaptable fellow, capable of living in small farm ponds, sandpits, flood control and irrigation reservoirs, slow streams, and river backwaters. He is available almost anywhere in Nebraska, and is usually abundant in waters where conditions are right for him. And, early in the season (like right now) before the water gets tepid, the largemouth is a rather tasty morsel in the bargain.

But, don't let his aggressiveness or abundance fool you, because the bass is nobody's dummy. But more important, the bass is a complex fish with a number of drives and requirements. And, different waters and different days offer him various ways of meeting those wants and needs. Thus, putting all the clues together to simply find the bass becomes a big challenge, to say nothing of getting the fish to slam a lure after he has been located. This challenge is probably the biggest thing about bass fishing that lures, and hooks, anglers.

The largemouth is an efficient predator, dining mostly on other fish but also hitting worms, insects, crawdads, frogs, small birds and just about anything else that doesn't eat him first. His whole existence centers around eating, surviving and staying just as comfortable as possible in the process. And, for a bass, comfort is mainly a matter of the proper temperature.

In fact, nothing rules a bass' life more than water temperature. Bass do not begin to feed actively or grow in the spring until the water warms to 50 degrees or more, but as it warms, the bass" appetite grows. At about 65 degrees, the males begin to think about selecting nest sites, and spawning takes place when the water is between 68 and 72 degrees.

Their metabolism is in high gear around 80 degrees, and this temperature seems to offer them the most comfort. Research in power plant cooling reservoirs, where a wide range in temperature is available, shows bass gathering in waters between 77 and 86 degrees. Generally, the smaller bass preferred the warmer end of the spectrum while larger ones favored slightly cooler areas. When the water reaches 86 degrees the bass begin to slow down, and at 96 degrees, they begin to die.

Cover is also important to bass. They apparently feel vulnerable in open expanses of clear water, so they hide out around sunken stumps, logs, weedbeds and the like. A bass doesn't like to chase a meal very far, either — uses up too much energy. So, he lurks in cover and ambushes his meals. The cover also gives him a refuge from bright light, which bass shun.

To help him live up to his reputation

as a big eater, the largemouth is

equipped with some pretty keen

senses. Though a bit nearsighted, the

bass sees anything within a few feet

quite well, and he sees it in full, living

color. He hears through a set of

internal ears on his head, and senses

15

vibrations like those made by a swimming baitfish (or lure) through very

sensitive nerves in his skin. His senses

of smell and taste also function well.

vibrations like those made by a swimming baitfish (or lure) through very

sensitive nerves in his skin. His senses

of smell and taste also function well.

All of these things help the bass find his food, and the angler can use them to make his lure appeal to the fish. But, these senses can also alert the bass to the angler's presence. A bass can see a fisherman standing in a boat or on shore, or perched high in a pedestal seat on one of those fancy bass boats. They can hear the hum of an electric motor or an oar bumped against the side of the boat. And, they can taste or smell the taint of outboard motor fuel or cigar smoke transferred to a lure by a fisherman's careless hand. What it all boils down to is that the bass has a lot going for him, and catching him consistently calls for a "savvy" and careful fisherman.

Knowing how temperatures affect bass will keep the angler from wasting time too early in the year. And, when the thermometer says spawning temperatures have been reached, the smart fisherman will be looking for sandy or sand-clay bottoms under two to six feet of water; favorite locations for bass nests.

After spawning, the bass' need for cover will tell a fisherman where to go. Sometimes, the bucketmouth's favorite hangout will be an undercut bank, or a tangle of tree roots along shore, or the edge of a weed bed, or the timber and hedgerows that were flooded when the pond or reservoir was built. The best way to determine the bass' cover preference at any particular time is to fish them all. If there's no action after a short time, move on. Once the bass are located, keep fishing places just like that until success drops. Sometimes, one particular type of cover will stay prime for only a few minutes, and at other times the action there may last for days or weeks.

Anglers should remember to the foot the exact spot at which they caught fish on other outings. Only largemouth know just exactly what it takes to make the perfect bass lair. But, they all seem to recognize a good hangout when they see one. So, if you catch a decent fish under a particular branch of a certain downed tree, try it again. Chances are another fish came along within a few days and called it his home.

Of course, it never hurts to learn more about bass fishing from other anglers. But, much of the information found in the reams written on bass fishing comes from other parts of the country with different kinds of bass water. However, we might be able to learn something from successful Nebraska fishermen, like those who took Master Angler fish last May.

The most obvious factor among them is the waters these anglers fish. The majority scored on lunkers in farm ponds, sandpits or small reservoirs. The only large lakes represented were Red Willow Reservoir, which produced a handful of good bass last May; Merritt Reservoir with a couple; Branched Oak Lake with a few; and a single trophy bucketmouth from Sherman Reservoir. It is apparent that big waters are not generally largemouthed bass waters in Nebraska.

The lures these fishermen used seem to tell a story, too. Spinnerbaits were far and away the most productive on big fish, accounting for one quarter (24) of all Master Angler Award bass taken in May of 1975. Ordinary spinners and plastic worms each accounted for another eighth (12 fish each).

Floating/diving plugs, deep-divers, surface lures, alphabet or "fat" plugs, spoons, live baits and various pork or plastic critters each took a handful of fish and accounted for the rest of the 98 fish. Four fishermen did not say what bait or lure they used.

Spinnerbaits are not usually fished much deeper than six feet, nor are floater-divers or a lot of the other lures. The Texas-rigged plastic worm can go deep, but it is also used a lot in medium-depth situations. It's an assumption, but judging by the lures used, deep-water tactics do not seem to produce all that well in Nebraska, at least not during May.

Of course, that would be expected early in the season when shallow-water temperatures are still comfortable for bass. However, the not-so-deep stuff continues to work to some degree all year long in Nebraska. Perhaps that is because Nebraskans are not familiar with deep-water methods, or it might be that big-water tactics simply do not appeal to them.

Much of a largemouth bass' worth is calculated on his status as an excellent sport fish, and so is a lot of the lore fishermen study about him. But, he has another value —that of maintaining a balance in the fish populations of the waters he inhabits.

Most good bass fisheries in Nebraska are based on the bluegill as a food source for the bucketmouth. The bass' appetite for bite-size bluegill keeps the lid on the panfish population and keeps it from dominating the lake. And, with the bluegill populations heavily thinned, the panfish grow to good size because there is enough bluegill chow to go around among the survivors.

If, for some reason, the bass are not able to keep up with the prolific panfish, the lake is soon overpopulated with stunted bluegill. These hordes of small fish prey on bass spawn and dominate the food that any surviving bass fry need during their first weeks. The result is disaster for both the bluegill fisherman (nothing but runts) and the bass angler (no bass reproduction).

How does a lake get into such sad shape? Too much fishing pressure on the bass and too little on the bluegill will do the trick in short order. This is exactly what happened so often on small lakes near eastern Nebraska population centers and those along Interstate 80. Under such intense fishing pressure, not many bass had time to grow to spawning size and populations of stunted panfish eventually took over.

In fact, this can happen to any lake if the small bass are not allowed to grow up. This is one reason for the 12-inch size limiton bass in Nebraska. For every good-sized bass in a lake, there are dozens of eight or nine-inchers, and they delight in eating just as many one and two-inch bluegill as they can find. Obviously, these junior largemouths are of much more value in the water doing their job on the bluegill than they are in a frying pan.

As a matter of fact, bassin' sportsmen would do well to release more bass, even if they top the 12-inch legal minimum. There's nothing wrong with keeping a few modest fish for the skillet, particularly early in the year when they taste best. And, fishermen landing a big ol' lunker shouldn't worry a bit about keeping him for the den wall. The oldtimer probably didn't have much longer for this world anyway.

But many bass are caught and killed by people who already have a freezer full of fillets and must struggle to give them away. And others catch and keep bass simply for bragging stock, camera fodder or "macho" points with the neighbors, and have no desire or intention of using them as food for themselves. The bass is too valuable as a fishery resource to be caught and killed for such motives. If you want to score a hit in the neighborhood by providing everyone with fish, do it with bluegill or crappie.

Releasing bass means that they may someday thrill another angler with a savage strike and strong fight. In the meantime, they will continue their campaign against panfish overpopulation with the utmost efficiency. Bass, bluegill and fishermen would be better off if this happened more often. Ω

the Wild Turkey in Nebraska

ONLY AFTER MANY unsuccessful efforts releasing game-farm " birds did Nebraska's wild turkey program get underway. Then, trapped wild birds were used, and they were capable of not only surviving but thriving in Nebraska's Pine Ridge. Although a native, the wild turkey was removed from the state by settlers who found this large, noble bird more desirable on the table than in the fields. Although it is often told, the success story of stocking the wild turkey bears repeating, as a nucleus of 28 birds was responsible in only 3 years for an estimated 3,000. Not only was it possible to then open a hunting season, but birds were also trapped and transplanted in other areas offering adequate habitat. It is now felt that all available wooded areas with sufficient cover to support a turkey population have received birds. Few game animals are so fascinating or frustrating, or are held in such high esteem by dedicated hunters. Following is a special section on these colorful birds.

18 NEBRASKAland

Return of the Turkey

FOSSILIZED REMAINS indicate that prehistoric turkeys roamed the eastern and southwestern United States. Five different prehistoric turkeys have been described that lived during the Pleistocene period some 15,000 to 50,000 years ago.

While early man, the paleo-lndians, preyed primarily upon larger animals for food and fiber, birds were also preyed upon, as evidenced by artifacts of later man. The wild turkey is believed to have played important roles in the cultures of pre-Columbian Indians, especially in Mexico and the southwestern United States. Historical records and archeological findings indicate that extensive domestication of the wild turkey existed throughout the southwestern United States and in Mexico. Although kept for food, turkeys were raised principally for feathers, to adorn garments and fletch arrows.

Early colonists were surprised to find wild turkeys in abundance. Generally, they found the flesh of turkeys a great delicacy. The wild turkeys, due to the loss of their forest habitat, disappeared from large sections of their original range following settlement of this country.

Natural selection of hereditary characteristics, which enables a living organism to adapt to particular environmental conditions, takes long periods of time. Distinct differences in size and coloration occur in different ecological regions. Generally, wild turkeys associated with the denser and moister deciduous forests of the eastern United States exhibit darker plumages, while less darkly pigmented turkeys are found in the drier southwest and in Mexico. The wild turkey, Meleagris gallopavo, is native and exclusive to North America. There are six recognized races or subspecies: the Eastern, M. g. silvestris; the Florida, M. g. osceola; the Rio Grande, M. g. intermedia; the Merriam's, M. g. merriami; the Gould's, M. g. mexicana; and the Mexican, M. g. gallopavo. The eastern subspecies, and possibly the Rio Grande turkey, was believed to have been native to Nebraska, but was extirpated by 1915.

While the original habitat has been greatly reduced in size, distribution of the wild turkey has been greatly expanded by restoration and transplantation programs being carried out by numerous states. The Nebraska Game and Parks Commission initiated a restoration program in 1959 that developed into an overnight success. The release of 28 Merriam's wild turkeys in northwest Nebraska was the nucleus for other successful introduction programs throughout the state.

Historically, the Merriam's turkey range encompassed portions of Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado and possibly Texas. The range is characterized by high mesas, deep canyons and rugged mountains. Ponderosa pine, juniper, pinon, and oak forests are the dominant types in this arid habitat. The extent of the turkey range within the region is limited by the type of vegetational cover.

Numerous early attempts were made to re-establish the wild turkey in Nebraska, both by private individuals and groups and by the Game Commission. Since all of the release stock was pen-reared and crossed with domestic strains, none of the birds possessed the traits necessary for survival in the wild. Thus, they soon succumbed to the environment.

The state's wild turkey program started with the release of 28 Merriam's turkeys in 1959 in the Pine Ridge, and 518 Rio Grande turkeys in 1961 and 1962 throughout the riparianwoodland habitat of central and southcentral Nebraska. The Merriam's turkey program met with immediate success, while the Rio Grande program showed only limited success and failed in most areas.

Nebraska does not have the rugged terrain and vast timber expanses found in the Merriam's historical range, however, the Pine Ridge of northwest Nebraska is similar. States of northern latitudes outside of the historic range of the wild turkey have also initiated release programs utilizing the western species and have met with success.

The Pine Ridge is a narrow escarpment about 90 miles long varying from a few miles to almost 20 miles in width. The extent of the area occupied by timber, interspersed with grassland and cropland, is approximately 630 square miles. The area

The predominant vegetation is open stands of ponderosa pine with understories of native and introduced short and mid grasses. Grasses include grama, buffalo grass, bluestem, switchgrass, needle-and-thread and wheatgrasses. Forbs include soapweed, sand sage, vetches, sunflower and a variety of other composites. The more mesic sites support a growth of deciduous trees with an understory of shrubs. Common hardwoods are boxelder, Cottonwood and ash. Shrubs include buckbrush, chokecherry and wild rose.

Preliminary reconnaissance of the Pine Ridge indicated that suitable habitat for Merriam's turkeys was in areas composed of 46 percent pine woodland, 32 percent grassland, 13 percent grain crops, 5 percent alfalfa and 4 percent deciduous woodlands.

In February and March of 1959, 28 wild-trapped Merriam's turkeys were released at two sites in the Pine Ridge area. Three toms and 17 hens were released at the Cottonwood Creek site northwest of Crawford, and 3 toms and 5 hens at the Deadhorse Creek site southwest of Chadron.

Following their release, the birds remained relatively close to the sites. However, with the breeding period rapidly approaching, the birds immediately set out to select suitable nesting sites.

The initial 28 birds ranged within 5 miles of the release sites during the first nesting period and wintered their broods in the same area. The Cottonwood Creek flock, where only juvenile toms were released, increased from 20 to 91, disputing previous beliefs that only adult males are capable of mating successfully.

As the second nesting period approached, the wintering birds dispersed and found sites in various creek drainages. Distribution of turkeys was Range of the Wild Turkey

The fourth year revealed that turkeys had moved into Wyoming through an extension of the Pine Ridge and into South Dakota through the Hat Creek drainage. Nesting birds and summer broods were reported in about 80 percent of the suitable habitat. Reports of birds traveling across rangeland and cropland indicated nest site saturation in some areas. It was estimated that during the fall of 1962 a minimum of 3,000 birds existed in the Pine Ridge, which duplicated population patterns of other western states. A limited fall season was allowed, with 500 turkey hunters bagging 281 birds.

A trapping and transplanting program was initiated in February of 1961 using the original Cottonwood Creek release site for the nucleus stock. These birds formed the parent stock for the greater portion of habitable Nebraska turkey range.

The population of Merriam's turkeys reached a plateau during the fall of 1963. The Pine Ridge turkey range had apparently reached its carrying capacity.

During 1975, after 17 years of turkey management, Nebraskans enjoyed four different types of hunting seasons. That year, 4,334 hunters bagged 1,457 turkeys during all the spring archery, spring shotgun, fall archery, and fall shotgun seasons. Ω

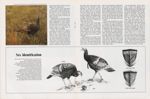

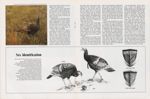

A Year with the Merriam's

SINCE THE DOMESTIC turkey was originally developed from wild stock, the general appearance of the birds is very similar. However, to the outdoorsman, some differences are very easily discernible. Wild turkeys have longer legs and a more streamlined body. The neck is longer and the head smaller and flattened. The adult Merriam's wild turkey normally has pink legs while those of young-of-the-year are brownish-gray. The large, black bird displays a variety of iridescent colors from bronze to green. Breast feathers of the torn appear to be jet black while the hen's are edged with a white band, giving the appearance of a white, frosted breast. The neck and shoulders of the bird appear metallic bronze in the sunlight. Wing primaries show distinct white bars with a light gray background. The back is covered with velvety black feathers. The tail coverts or rump feathers are edged with white or light tan. Farther back toward the tail the feathers are a rich chestnut brown with darker markings. The tail feathers are almost black with chestnut markings and a light tan or buff-colored tip. The head of the torn is bald with a narrow band of feathers running up the back of the neck almost to the crown. The head is greenish blue except when the torn is excited, when it will turn red about the neck and reddish blue in the cheeks. The hen's head is covered with a scattering of short, velvety black, hair-like feathers.

The wild turkey, the largest upland game bird of America, weighs up to 30 pounds. During fall hunting seasons in Nebraska, Merriam's turkeys average 18 pounds for adult toms, 12 pounds for juvenile toms, 10 pounds for adult hens, and about 9 pounds for juvenile hens.

As the days grow longer and nights shorter during late winter and early spring, the increased amount of light upon the receptive cells in the eyes of birds and many mammals causes a response from certain endocrine glands. The hormones produced enlarge the ovaries of the hen and the testes of the torn, resulting in physiological changes in the birds. Courtship and mating begins about the same date each year despite temperature variations. The toms spend increasing periods of time in gobbling and engaging in mock battles with one another. Often these activities result in a squaring off of two males with much neck exercise, similar to "necking", and end with a show of strength with the pair having their necks twisted around each other.

Dominant males soon establish breeding territories on which more and more time is spent. During the peak of courtship and breeding activities, the toms are on their established mating grounds entertaining as many hens as choose to visit them.

Breeding or mating grounds are also referred to as strutting grounds. There may be several within the territories of dominant males. Several adult toms may frequent an area established as their territory and visit their strutting grounds, and will actively defend them against lesser males. Gobbling is their way of announcing their status and encouraging hens to visit them. When the hen becomes receptive to mating, she will seek out strutting grounds and participate in the courtship ritual. Mating is promiscuous, and while non-receptive females will avoid the toms, receptive hens will seek them.

The tom's courtship display movements are slow and deliberate with a

proud display of feathers. The wings

are lowered to the ground with the

primary feathers spread apart, sometimes dragging in the forest and grassy

litter. Body feathers are held erect and

the tail is held upright and fanned out,

cocked first to one side and then the

other. The neck is pressed against the

body while the upper portion of the

neck is curved forward in an S-shape.

The caruncules (fleshy part of head

and neck) change from red to blue

and the peduncle becomes elongated

and turgid. The presence of a receptive female increases the intensity of

the male's courtship display. Pacing

back and forth, several quick steps

may be taken toward the hen with his

wings dragging while expelling air in

puffs.

and neck) change from red to blue

and the peduncle becomes elongated

and turgid. The presence of a receptive female increases the intensity of

the male's courtship display. Pacing

back and forth, several quick steps

may be taken toward the hen with his

wings dragging while expelling air in

puffs.

The male is a formidable sight of solid power in the early morning sun, as the feathers display various iridescent hues of bronze, gold, red, green and blue. The female responds by assuming a low crouching position, holding her head close to her body with tail low, but raising her head as the male approaches. The male mounts the female very deliberately, with their sexual organs in contact it takes only a moment to consummate the copulatory act.

Only one successful copulation is necessary for the eggs of a single clutch to be fertilized. Eggs laid up to four weeks after the last mating have been found fertile, as the walls of the upper oviduct serve as reservoirs for the male sperm. Sperm has been found to remain viable for 56 days in the oviduct of the hen.

When the turkey hen becomes broody, her ovaries begin to shrink and mating ceases. It is at this time, when the hens are on the nest incubating their eggs, that the amorous males respond to artificial calls and can be lured to within shooting range of the hunter. Based upon information compiled in Nebraska, most hens are actively engaged in nesting by mid to late April.

Nests, which are crudely constructed, may be only slight depressions in the forest litter. Several nests have been examined which revealed very little concealment; located in open areas and usually on a side hill. The eggs are highly resistant to cold as shown by late snowstorms during the spring of the year which still resulted in fair production. An undisturbed, experienced hen covers her nest with feathers, leaves and other forest litter when leaving to feed or water. Clutch size averages 10 eggs, with 13 to 15 not uncommon. Egg laying usually takes 14 days for the 10 eggs.

The incubating hen leaves her nest secretively for short periods during the early or late hours of the day for brief feeding and watering. Nest abandonment is not infrequent during the early stage of incubation, but the hen will exhibit greater broodiness during the last several days of the 28-day incubation period. The frequency of abandonment is not known in our turkey populations, but it is suspected that disturbance by human intervention is a far greater cause than any other.

Hatching peak in Nebraska occurs during the first weeks in June. Although hatching may occur over a period of 24 hours, most of the eggs in the clutch hatch out within a short time. Shortly after hatching activity ceases, the hen leads the poults to a nearby grassy opening where insect life abounds. The poults grow rapidly on the protein-rich diet of insect and other animal matter.

Chilling by dew or summer showers during the poults' early life can be disastrous. The hen's body and wings provide adequate warmth and shelter for the poults from precipitation, but if they feed, they may get wet. The hen will lead her brood to a feeding area as soon as a storm lets up. The young poults following the hen may be in head-high, moist vegetation and may soon get chilled. Lowering of body temperature will soon affect the poults and they will become sluggish and lie down frequently. The hen may notice the loss of a poult, but can only call to her straggler. If the weakened poult does not join the family group, it will be left behind to succumb to the elements.

The young poults are brooded on the ground for about four weeks since it takes that long for the primaries to develop and sustain the turkey in flight. However, even at two weeks of age a young turkey is capable of hopping

As summer progresses, the brood is

joined by other families. Much can be

said in favor of this gregarious nature

of turkeys as there is safety in numbers. A group of turkeys can feed and

travel in safety as there are more sentinels to keep watch. At no instant will

all the birds have their heads down

and feeding, thus any suspicious

movement or object will be noticed

and soon the entire group will be

alerted. Observations of turkeys indicate that while the birds' vision is no

sharper than man's, it is capable of

detecting the slightest change in position of an object. Vision of the bird is

flat and requires several quick glances,

and from different positions, to ascertain size, shape, and interpretation of

an object. Experienced hunters have

learned this fact and try not to reveal

themselves with movement even

though they may not be concealed too

well, as the wary wild turkey cranes

his neck one way and another to get

a better picture of the scene. Studies

have shown that wild turkeys can easily detect differences in some colors

such as white and yellow. Nocturnal

vision is quite poor, and no movement from one tree to another occurs

after they go to roost. When disturbed

and forced to leave their roost, they

will awkwardly blunder about, crashing

Turkeys usually start to roost about sundown and leave shortly before sunrise. However, on dark, overcast days the birds may go to roost earlier and on cloudy or snowy mornings may spend a greater portion of the day on their roost trees.

Observations of wild turkey behavior indicates that their hearing is quite sharp, comparable to man's. Turkeys detect differences in sound frequencies more easily than do human ears, and like most wild creatures, are acutely aware of a great range of sounds in their environment.

Turkeys, like most birds, have a poor sense of smell but it is believed they possess a sense of taste about equal to man. Wild turkeys are not finicky in their choice of food. They are omnivorous feeders and will pick up nearly anything and consume it. Their choice includes soft vegetation and insects to very hard nuts and pits of fruits. Greens, seeds and animal matter constitute the major portion of the turkey's diet in spring and summer while fruits are consumed in great quantities in late summer and fall. Mast and waste grains are used in late fall and winter. Pieces of minerals and rocks that they pick up and store in their gizzards help break down hard food material. The digestive tract is highly developed and has a high microbial count of bacteria that enables the wild turkey to utilize many varied and bulky items.

The wild poults and young turkeys depend on the wisdom of the older birds. In response to a warning cluck of the hen, wild poults will freeze and be camouflaged in the surroundings while domestic birds will scatter. Older birds will rely on their long legs to carry them from danger in short order, although they are capable of swift flight.

When startled or if danger is close at hand, the birds take to wing and fly at speeds of about 30 to 35 miles per hour. It has been estimated that the wild turkey can attain a flight speed of up to 50 or 55 miles per hour. Perhaps this is achieved in a flight down into a valley. The distance flown is dictated by the terrain and the danger, but flight capability is one of the turkey's greatest assets for protection. After a few running steps he can spring into the air and the wings will lift him quickly upward. Rising almost straight up until the tree tops are cleared, the bird levels off and glides and soars to safety.

Sex and age information of a flock of turkeys in the wild are important in managing the species. Determination of sex is more difficult during the sub-juvenile state, but even as early as September, when turkeys are 12 to 15 weeks old, sex can be determined by examining the contour feathers. Male's are black tipped and female's are white tipped. In younger males, the black band may be masked by a buffy fringe that will eventually be worn off. By late fall, most of the young birds of the year can be sexed easily by the feathering of the female's head, or the lack of feathering of the male's head.

Sex determination of the mature birds is easier. The gobbler has a greater portion of his head devoid of feathers and covered with fleshy folds of skin that elongate to great size during sexual excitement. The contour feathers of the body, especially the breast, are tipped with a dark black band of a rich sheen that makes the torn appear black in the distance. These same black feathers will become iridescent with many colors in the sunlight. The shape of these breast contour feathers are more squared than that of the females, which are rounded at the edges. The "beard" is a group of modified feathers found on the breast of the gobbler. It may attain a length of up to 12 inches, but is usually about 6 to 10 inches long. These hair-like feathers look like bristles, and continue to grow throughout the birds' lives, but wear and breakage limits the length. It is not uncommon to find birds possessing multiple beards. Adult toms also possess a modified scale on their tarsus which is commonly referred to as a spur.

Hens have a more feathered head than the male and lack the fleshy folds of skin. Her contour feathers are white tipped rather than black tipped, and generally they do not have beards or spurs. However, it has been found that from 10 to 20 percent of adult hens possess the hair-like appendages with some up to 7.5 inches in length. Therefore, hunters after gobblers in the spring should not use this characteristic alone in determining the sex.

Longevity of the wild turkey has been recorded up to 10 years, but in a hunted wild population this is quite rare. Our marked bird information shows a longevity of at least 6 1/2 years, while tag recoveries show a population turnover of 56 percent.

Movement of turkeys varies from day to day and with season of the year. Basically, habitat quality is the most important factor influencing the extent of daily and seasonal movements.

When a flock is favored with good range, the birds remain in a relatively small area, but in years of poor mast crops the birds may have to range a greater distance. Generally, young hens are greater travelers, perhaps in their quest for nesting sites.

Wintering turkeys spend much of their time feeding, and often range large areas. The warmer, southern slopes are utilized as the snow disappears sooner, making scratching in the litter for pine mast and other seed crops easier. The turkeys group together in large flocks of families. The adult males form their own group but frequent the same feeding and loafing areas. Roosting sites at this time may have a series of trees occupied by as many as 200 to 300 birds.

Predation in the wild is a constant battle for the wild turkey. Acute vision, hearing and quick flight protect the turkey in his struggle for survival against both avian and mammalian predators. Perhaps the most important predator is the bobcat and possibly the coyote. Other predators are the golden eagle, great horned owl, raccoon, fox, skunk, badger, magpie and crow. Losses in the wild to these predators are not considered harmful to the turkey population since most of these natural predations occur upon weak and sick birds. There are situations when predation may have a drastic impact upon the wild population, but if the habitat provides adequate cover the effects are minimal.

The only predator that the wild turkey must fear is the human, with his efficient equipment and machines that can alter the habitat drastically. Uncontrolled fires, started naturally or by man, may destroy the turkey habitat in a short time.

The turkey is known to be susceptible to many diseases and parasites, especially under confinement. Probably the most feared disease that may ravage a population of turkeys is blackhead, or enterohepatitis, especially in a high-density flock. Other diseases that are more commonly cited in literature are fowl cholera, fowl pox, fowl typhoid, avian tuberculosis and coccidiosis. Parasites that are commonly found internally in the turkey are roundworms, tapeworms and flukes, and externally, lice, fleas, flies, mites and ticks.

Several Merriam's turkeys bagged during past hunting seasons have shown lesions on the internal organs, mainly the liver and spleen. Specimens examined by the pathology laboratory in Lincoln revealed the birds were infected by Mycobacterium avium, the causative agent for avian tuberculosis. It is said to be a contagious disease characterized by its insidious chronicity and persistence in a flock once established. It shows few external signs and in general produces unthriftiness, lowering of egg production, and finally death.

Prevention and control of this disease, as in all disease and parasites, is difficult and there is no current cure. Sanitation is about all that can be suggested. For this reason it is best not to encourage large flocks of wild turkey in a given area. Artificial feeding, yarding, and over-protection are not good management practices and certainly not to be recommended. Ω

Managing the Flocks

WILDLIFE IS A renewable natural resource, and if managed wisely, can be cropped annually without depleting the stock. In the management of big game animals in Nebraska, including the wild turkey, policies must take into consideration the interests of sportsmen and landowners upon whose land most of the animals live. The goal of sound management is to provide the greatest number of wildlife and recreational benefits to the sportsmen while keeping the populations at levels consistent with the agricultural interest of the land. Flock and population inventories taken throughout the year and the analysis of harvest information play major roles in managing turkeys in Nebraska.

Currently, the basic objective of providing the greatest number of wildlife consistent with land use is being met. However, the aesthetic value of the wild turkey is outweighed so much by its agricultural value that some landowners who are plagued by annual infestations of insects on their land encourage and protect the flock of wild turkey. This over-protection may cause some problems to the flock and the habitat.

Surveys to determine population status start with winter flock counts which result in the relative population number prior to production period. These wintering population numbers have fluctuated to a high of 3,155 in 1969 from the original 28 birds in the Pine Ridge. The Pine Ridge fall turkey population has stabilized at 4,500 birds or less, while the wintering bird numbers have averaged 1,450. Despite flucutations of the wintering population, the fall population estimates have not varied much from year to year, indicating that a 4,500-bird population in the fall is the carrying capacity for the Pine Ridge range.

Brood indices compiled by 5-year averages reveal a continual decline of

The interpretation of data is difficult

due to the varying factors that may

be affecting total population and production. However, the primary limiting factor may be lack of nesting habitat. This has been based upon the fact

that brood indices are still quite respectable and that when applied to

the known number of wintering birds

should result in a high fall population.

Then, after subtracting the number of

birds taken during the legal harvest

there is still a great number of birds

unaccounted for. It is unrealistic to

think that every year we have a high

mortality attributed to poaching, predation, winter storms, etc. Therefore,

we return to the theory that production was not as high as we believed,

and to the hypothesis that nesting

sites may not be available to all the

hens. Therefore, any downward trend

in the fall population would have to

be attributed to known natural phenomena or a change in the habitat,

rather than a low reproductive potential.

in the fall population would have to

be attributed to known natural phenomena or a change in the habitat,

rather than a low reproductive potential.

Harvest data are analyzed and form the basis for determining whether the management plans are correct or not. The sex and age information of the harvest would generally reflect the structure of the wild population if there were no hunter selectivity for size or sex. The percentage of categories varies from year to year, but during the fall 1975 season, adult males made up 10 percent of the harvest; adult females —27; juvenile males — 33; and juvenile females —28. The youngiadult ratio was 230 young: 100 adult hens compared to the 13-year average of 526:100. The low ratio may be a reflection of an underharvested population or a poor production. However, there were no indications of poor production in 1975. Most of the turkey populations in the United States are presently considered underharvested.

Weight information reveals the physical condition of the flock as the result of range conditions. It may also reveal disease or parasitic infestations in any individual flocks, or an unusually late hatch. Adult males average 18 pounds, juvenile males 12, adult females 10 and juvenile females 9 pounds during fall harvest. Unusually late hatch of some birds resulted in some light weights of 5 pounds in some year's fall harvest. Comparison of data of whole weight versus eviscerated weight indicates a factor of 12 percent can be used for the Merriam's species in the Pine Ridge. The largest bird recorded was 23.3 pounds eviscerated, or about 26 pounds whole weight. There have been heavier bird weights reported but these were suspected of being crossed with the domestic strain.

Crop content examinations confirm that wild turkeys are opportunists, omnivorous in habit, and voracious in appetite. Wild turkeys have been known to have a crop capacity of about 400 cubic centimeters (0.42 quart). This may occur when the birds come across some desirable and abundant food source. Usually, the birds spend much of their time feeding and therefore need not gorge themselves.

Harvest information shows that 87 percent of the successful hunters required 2 days or less to bag their birds during the 1975 fall season. Seventy-one percent of the harvest occurred on opening weekend with 204 hunters bagging 1,138 turkeys for 57 percent success.

During the spring of 1975, 1,875 shotgun hunters bagged 490 toms for a hunter success of 26 percent. Fifty-four percent of the harvest occurred on the first 2 days of the 16-day gobbler-only season.

During 1975 there were both spring and fall archery turkey seasons with 289 and 170 participants respectively. Hunter successes were 7 percent for the spring gobbler-only season, and 28 percent for fall. Successful archers expended an average of 2.7 days in the spring and 2.9 days in the fall. However, this is not a true measure of the total archery-hunter days the season offered. There were no data compiled concerning the number of days expended by the unsuccessful hunters, but personal contacts indicated a much higher effort than by successful hunters.

After the fall hunting season and when the turkeys are flocked together on their wintering areas, trapping for the purpose of marking birds for basic life history information gets underway. Turkeys at different locations in the Pine Ridge have been captured and wing marked with nylon streamers. The colorful material lays flat over the secondary covert area and is noticeable at a great distance. Traps of various types have been used, including box traps, wire funnel traps, a walk-in frame nylon netting trap, and cannon-net trap (projectile type).

During the winters of 1965 through 1973, 317 turkeys in the Pine Ridge were marked and released, of which 93 (29 percent) have been shot or found dead. Hens marked as juveniles were recovered an average of 5.3 miles from the trap sites as compared to other sex and age groups (young toms, adult hens, and adult toms) which traveled averages of 2.3 and 2.8 miles. One young hen was shot 19 miles from the trap site.

More recent work conducted along the Niobrara River has shown considerably greater movement of turkeys than in the Pine Ridge. Average recovery distance so far was 13 miles, with the longest traveler covering at least 29 miles. Dispersal of 43 miles (considering both directions) was observed within three months of the time of tagging. The greater movements along the Niobrara River are attributed to the comparatively narrow habitat as compared to the Pine Ridge.

A trapping and transplanting program was initiated in the winter of 1961. The Cottonwood Creek birds formed the parent stock for the greater portion of habitable turkey range in Nebraska. By 1963, turkeys had been released on all areas with natural stands of ponderosa pine. Releases along the Niobrara River met with good results, but those in the Wildcat Hills and Cheyenne escarpments were less successful.

In the Niobrara River releases, one flock in the eastern end ranged into areas made up almost exclusively of hardwoods. With this favorable indication of hardwood use, deciduous cover was considered for turkey releases. Some areas of marginal habitat were thus utilized for releases, and between 1963 and 1970, 19 such sites were stocked with 166 birds.

Increases occurred in most areas, regardless of habitat type, and peak numbers were reached within three reproduction years in these narrow habitat types. However, major declines resulted in all areas without ponderosa pine, and none of these releases resulted in more than a token population.

In one area of sparse timber cover, Merriam's turkeys crossed with game-farm stock, resulting in a comparatively successful establishment of birds. Previous attempts at releasing game-farm reared birds in Nebraska met only with failure, but apparently a hybridization of wild strain with game-farm birds was suitable in this type of habitat.

Ten wild-trapped eastern turkeys were released at Indian Cave State park which resulted in limited production but eventual failure.

Many people enjoy just having the turkey around the old homestead. They are beneficial in their foraging for succulent insect life, so what grain they may pick up is quickly forgiven. During the winter, when the birds flock together and appear to barely eke out an existence, many well

Wild turkeys have been known to not feed during an 8-day storm, while birds held in captivity were allowed to go without any feed for 14 days without mortality. Therefore, an inactive flock during a snowstorm does not indicate inadequate winter food.

The well meaning individual should establish natural food areas near escape cover instead of placing feed out for the birds. Creating habitat is important, but holding on to what is there is more important since habitat cannot be created overnight.

With a good place to live that provides adequate food, cover, water and living space, the Merriam's wild turkey should be able to reward us with his presence for a long time. To insure the success of the turkey program, we must have an informed and aware public. Without the efforts of land operators, the protection of laws and regulations, and the awareness of the public, no management program can succeed. Ω

Cropping the Surplus

TECHNIQUES AND STRATEGIES for hunting the wild turkey vary with individual hunters and field conditions. Regardless of the technique used, it is the hunter who planned his hunt and anticipated the first day afield that will be most satisfied in the end. This is only attained through experiences compiled after many trips. A successful hunt need not end with a bird in the bag, but to be holding a bag with a bird in it requires a combination of factors that the hunter must attend to.

Many times a certain experienced turkey hunter that I know has been asked, "How did you come by your bird?" His reply was always, "Just plain luck!" It was always thought that this turkey hunter did not want to reveal his techniques and secrets. However, after getting to know this hunter, it was apparent that it was knowledge that helped form his luck. Turkey habits and behavioral characteristics were learned, he studied and practiced the different calls and communicating sounds of the species, learned the capabilities and became adept with the weapons used, and became thoroughly familiar with the area he planned to hunt.

Since conditions vary in the field and no single method always works on turkey, only hints to a successful turkey hunt will be suggested here.

During the pre-season preparation period, the hunter should obtain all the reading material he can obtain and study it. Popularized magazine stories can certainly help, but usually contain very little information on species behavior, food, nesting and cover. Obtain several different types of turkey calling devices, and along with instructional reading material and recordings, practice with them to develop expertise and confidence. The latter is very important when you are in the field. After selecting a hunting area, obtain detailed maps which will help locate yourself in relation to the surrounding terrain. Planning your trip can be easier if you inquire around for someone who is familiar with the chosen area. Fortunate is the one who can get an experienced hunter to take him afield to put his book learning to practical use.

Selecting the turkey gun is a matter of personal taste, since any legal gauge and shot size will do the job. Remember, the large bird can absorb quite a few pellets in the body, and the heavy wing feathers may shield the bird, but 2 or 3 pellets in the head and neck will finish the quarry. The 12-gauge shotgun loaded with No. 6 shot backed with No. 4 is the choice of many hunters.

When the season approaches, plan on arriving in the chosen area a day or two early to study the lay of the land and to look for turkey sign. After obtaining permission to hunt on privately owned land, the hunter should identify the limits of the property. This can be done at the same time you are looking for turkey sign, such as tracks around wet places, droppings in feeding and loafing areas, roost tree sites, and tell-tale signs of feathers.

During the fall when the turkeys are in family groups, the flush and call method is quite effective. Since the birds are very gregarious and have a strong bond for each other, they can be lured back with a turkey calling device. The hen, upon having her family scattered, will attempt to regroup the birds and the young birds will respond to the call.

Some hunters will locate themselves in turkey territories and will call in an attempt to lure birds that have been scattered by other hunters.

The drive method is used by hunters working together through an area pushing the birds ahead of them to stationary hunters on the theory that turkeys prefer to walk or run instead of flying. Even pass shooting opportunities occur in this type of hunting.

Roosting area locationsare searched for by some hunters who will try to call the bird in to them. This is similar to calling and also flush and call. Shooting the birds off their roost trees is not very sporting and some hunters feel this is a good way to lose a flock in an area.

Stalking is very difficult and tests the hunter's abilities in woodcraft, trailing, and knowledge of the species.

Still hunting is for the hunter who can sit quietly and concealed for many hours waiting for the turkey to come down a well traveled trail.

Regardless of which method is used to hunt the wild turkey, knowledge of the terrain and of the species will play major roles in outwitting the trophy.

The most challenging and thrilling form of turkey hunting is in the spring gobbler-only season. In the Pine Ridge area, spring gobbler-only hunters have scored 25 percent compared to 55 percent during the fall any-turkey season.

When the gobblers first announce their vigor and dominance from their roost trees in the early dawn gloom, half an hour before sunrise or earlier, the hunter's pulse will quicken and he will wonder if he arrived too late. The course of action might be to move closer or sit still, call now or call later, call often or not. All these thoughts will race through the hunter's mind while the torn continues his gobbling in the early morning light. Suddenly, the whirring of his large wings will indicate that he has left his roost to join the group of hens on his strutting ground. Once he has joined the females, calling the torn into gun range will be difficult.

Often, the toms will quit gobbling soon after leaving their roost. Locating the birds under these conditions will be difficult, but the patient hunter can remain in a likely spot and utilize his call or can start his stalk. Turkeys are creatures of habit, so the observant hunter records the time and place of each event and tries to revisit the area.

Calling devices may be wing-bone type, slate scratch type, box type, diaphragm mouth type, or any other. The best type, however, is one that the hunter is comfortable and confident with. Many find the box type with a large friction paddle the easiest to use.

Whichever is used, the hunter may be fortunate and see the deliberate approach of the proud bird, or often as not, may not notice the approach from his blind side. When this "moment of truth" presents itself, lucky is the hunter who is capable of controlling himself to select the most vulnerable spot of the large bird, the small head and neck region.