NEBRASKAland

April 1976

NEBRASKAland

VOL. 54/ NO. 4 /APRIL 1976 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Fifty cents per copy. Subscription rates $5 for one year, $9 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. commission Chairman: Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 Vice Chairman: Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-Central District, (308) 745-1694 2nd Vice Chairman: Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-central District, (308) 452-3800 H. B. "Tod" Kuntzelman, North Platte Southwest District, (308) 532-2982 Richard W. Nisley, Roca Southeast District, (402) 782-6850 Director: Willard R. Barbee Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, Jr. Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: Jon Farrar Greg Beaumont, Ken Bouc, Contributing Editors: Bob Grier Faye Musil, Tim Hergenrader, Roland Hoffmann, Bill Janssen, Ben Schole Art Director: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commision 1976. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska APRIL 1976 Contents FEATURES BEAGLING FOR BUNNIES 8 FISHING THE WALLEYE RUN 12 BEAUTY AND THE HUMAN BEAST 14 ARBOR DAY: A STERLING IDEA 18 THE WILD EDGE: LIFE OF A MARSH 20 THOSE DAM CATS 32 TREES! PLANTING FOR THE FUTURE 34 ANYTHING FOR A HORSE 38 OLD BEFORE ITS TIME 40 NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA/BLACK-TAILED JACKRABBIT 50 DEPARTMENTS SPEAKUP 4 TRADING POST 49 COVER: Eared grebes are common residents of marshes in western North America. Constructing floating platform nests from aquatic vegetation, they are colony nesters. (500 mm lens on 214 single-lens reflex) Photo by Greg Beaumont. For story on marsh life, see page 20. OPPOSITE: Cursed since man first planted crops, the multitude of prairie grasshoppers are an indispensable food for more desirable wildlife. (35 mm with 100 mm macro) Photo by Jon Farrar. 3

Speak Up

Warranted Attack Sir/I'm sure glad to hear that Carleton, Nebraska has gained some notoriety through your "Speak Up" column (October 1975) followed by your "attack" (but warranted) for the lady from Carleton. Apparently it has been overrun by a horde of unscrupulous, social-moral degenerates posing as hunters.

I've lived most of my life in Carleton and that's a great little hunting locality. However, if you pass through there in the near future, you may notice some residents holding aching sides. Don't be alarmed —just a result of reading that bizarre fabrication a Carletonite concocted for NEBRASKAland, October 1975.

Have some doubts? Go to Carleton-a fine place with fine people —and get the real story. Name Withheld

It is always with severe doubt that a crank letter is accepted as representative of any group (as with our lady), but there are problem areas because of problem people. Thanks for your views on the subject. (Editor)

How is Knox? Sir/How I enjoy the articles about my home state! In the 4 years I have received the magazine, have yet to see anything about good old Knox County and Creighton, Center and Verdigre — good old home towns.

Would love to see a picture of the court house in Center. I understand it is a real old one. Is the old stone school house in Center still in use?

Would love to get in touch with descendants of the Ballard, McGill, Weaver or LaFrance families. Thanks. Viola Hogle Box 87 Rt. 1 Montague, Cal. 96064

Nice Surprise Sir/Today we received the nicest surprise in the mail. Thank you for the special commemorative issue, Portrait of the Plains. We enjoy all your magazines, but will especially treasure this one. Joe, Marlene, Kevin and Mark Booth

STUHR MUSEUM of the Prairie Pioneer U.S. 281-34 Junction Grand Island, Nebraska 68801Send Subscriptions Sir/My wife and I congratulate you on your January issue of Portrait of the Plains. This issue alone is worth more than the whole year's subscription to the magazine, and as soon as we recover financially from Christmas, we are going to send a subscription to our son in Minnesota and our two daughters in Arizona. I think everyone of your subscribers should do this: send a subscription to sons and daughters and friends in other areas of the country so that they can see what a truly great state we live in. Ferd Bogner Crofton, Nebr.

For Archives Sir/I received my copy of Portrait of the Plains. It's just great and I intend to place it in my archives.

The past two seasons I have hunted pheasants in Nebraska and although I didn't fill the deep freeze, the trips were worthwhile. However, that which I enjoyed most was the hospitality of the people and a most pleasant atmosphere. Gary Buchanan Wisconsin Rapids, Wis.

Finest Ever Sir/The copy of Portrait of the Plains is the finest thing that I have ever seen. I have used many of the previous pictures in my home over the years. Many of my friends have seen the pictures framed and it has "caught on". Truly a fine, rewarding gift to all. Mrs. Joe Tess Omaha, Nebraska

Thanks For Photos Sir/We received the book, Portrait of the Plains, and want to thank you for the wonderful pictures of our state. Nebraska is indeed a beautiful state. Mr. and Mrs. Forrest Billings Franklin, Nebr.

Congratulations Sir/I just received Portrait of the Plains. It is beautiful. You and your staff can be proud of the job you have done. Congratulations! Harvey Gunderson Associate Director of Museum and Professor of Zoology University of Nebraska-Lincoln

NEBRASKAlandSURPLUS CENTER

Nationally Known ~ World Famous

OPTIMUS Camper's Outfit Regular Sale $74.20 Special, As Shown $66.95

The Commonwealth now pays even higher interest rates!

6.25% Passbook Savings 6.54% Annual Yield Comp. Daily 6.75% 1 Yr. Cert. 7.08% Annual Yield Comp. Daily 7.00% 2 Yr. Cert. 7.35% Annual Yield Comp. Daily 7.25% 3 Yr. Cert. 7.62% Annual Yield Comp. Daily 8.00% 4 Yr. Cert. 8.45% Annual Yield Comp. Daily A substantial interest penalty, as required by law, will be imposed for early withdrawal.the Admiral's Cove inc.

WILLOW LAKE FISH HATCHERY

J'S OTTER CREEK MARINA

NORTH SIDE LAKE McCONAUGHY HWY. 92-OPEN YEAR AROUNDPortrait of the Plains

NEBRASKAland Magazine and Nebraska Afield & Afloat

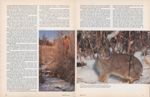

BEAGLING FOR BUNNIES

Small, ambitious dogs set a fast but easy-to-follow pace

THERE IS SOMETHING totally different about hunting with hounds, and there was little doubt that those little dogs were really hounds, as they packed plenty of noise and energy in their little bodies.

We were pursuing bunnies, and doing most of the work and providing all the noise and color was a pack of beagles. While in more recent times the beagle is often considered just a "cute" dog, he was originally bred for the express purpose of hunting. His lineage up to that time may be somewhat clouded, but the result is certainly quite clear —he is a small bundleof energy that prefers running and sniffing to almost anything else.

The beagles were not just a rowdy bunch of amateurs. They were a well trained but loose-knit crew belonging to Jim Conway of Bellevue. Although now officially retired from a railroad career, Jim is far from

Also on the hunt was Jim's son Dan, whose bunny hunting fervor matches if not exceeds Jim's. Dan is a fireman at Offutt Air Force Base, but has a schedule which allows him nearly as much time to hunt as he wants.

The five beagles presently snuffling and padding around in the trees were all eager, and all well-versed in the game of detecting and trailing cottontails. They had ridden quietly reposed in the back of Jim's station wagon, but when we pulled in and stopped, they were ready to go. Although considered small as dogs go, being only about a foot to a maximum of 15 inches high, their lungs and noses must be at least 50 percent of their weight.

Beagles are great dogs, cute and extremely pleasant to hunt with. They don't go dashing off into the distance unless they are on a hot trail, and then, bunnies being what they are, they usually will be back within a few minutes. When we first set out, the little dogs seemed to have individual preferences of habitat to work. Some went low, working the frozen-over creek bottom, others stayed on the hillside, puttering in the trees.

Within a few minutes after starting, I was on a hillside and things were quiet, when I heard a rustling sound in a small draw. Walking over, I saw one wrinkle-faced beagle, tail wagging almost continually, shiifflihg around the bottom. It, or she, seemed to detect evidence of bunnies there, but not fresh enough to get excited about and call the other dogs.

I guess the vocalness of trailing dogs is remarkable

enough, being able to distinguish what they are up to at

any given time, but coupled with that magnificent nose

is downright amazing. It is nothing short of fantastic that

any animal can poke a nose on the ground and detect

faint traces of another animal that may have passed

there hours before. Yet, those dogs can tell of two recent

scents which is the most recent, as if there were little

arrows showing the direction of travel.

enough, being able to distinguish what they are up to at

any given time, but coupled with that magnificent nose

is downright amazing. It is nothing short of fantastic that

any animal can poke a nose on the ground and detect

faint traces of another animal that may have passed

there hours before. Yet, those dogs can tell of two recent

scents which is the most recent, as if there were little

arrows showing the direction of travel.

The wrinkle-faced dog finally gave up on the gully without causing any rumpus, so I assumed there was nothing fresh to report. Elsewhere, four other dogs were still going over other parts of the terrain, and they weren't making much racket either. Occasionally one of them would make a sound or two, but the other dogs, and Jim, knew it was nothing to get excited about.

We had covered nearly a quarter mile of creek bottom and hillside before things started to happen. Then, there were very few minutes when a trail was not being pursued. We must have gotten into the bunny area.

When a hot scent was discovered, there was no doubt about it, as the excitement could really be heard in the dogs' voices. After several hot and cold trails were signalled, even I got to know the difference. I guess that is when hunting with dogs is most enjoyable —when you can tell when they are or aren't on a fresh track. At any rate, during the next couple of hours there were few times when those beagles weren't pushing something through the trees.

Jim and Dan were both toting shotguns for the time when they could see a cottontail, but only Dan was to cash in. He garnered two bunnies while Jim had only one slim opportunity, which he missed by not being ready.

During one period of about five minutes, I saw three bunnies dashing hither and yon, scooting under or between trees, but I was unarmed, and don't think there would have been time to get a shot off anyway. I suppose the rabbits know there is something going on out of the ordinary, for they didn't just hop and stop —they were moving around with considerable enthusiasm for what must have been safer cover.

A couple of times the dogs ran a rabbit into a hole, and at that stage they seemed to pause only a few minutes and then give up, seemingly aware that a new trail was the wisest course. With only a sniff and a peek, they headed away from the hole.

Another time, Jim and I were standing in a little meadow at the base of a steep hill. We could see nothing up on the hill because of the dense trees, but we could hear the dogs running and baying, if that is what they do. They were heading nearly away from us, and I wondered if we should follow.

"They'll be back," Jim said. And, sure enough, within a minute I could tell they had turned around, probably hot on the heels of a scooting rabbit. They came back nearly to the place we had first heard them, then the pack seemed to break up. Either the rabbit had gone to ground or had doubled back in an area of a maze of tracks where the dogs got confused. Jim theorized the bunny may have heard us talking and turned tail rather than come into the open meadow.

Even so, it was fun hearing the activity and wondering what was going on above us. Eventually we saw a few dogs working down nearer to us, and we knew they had lost the scent.

Having been on several coon hunts, the difference in style was perhaps the most noticeable thing about the beagles. It is lucky to stay even within earshot of a pack of coon hounds, as they really move long and fast on a trail. I suppose beagles would too if they were following a raccoon, but it seemed you could keep up with them easily merely walking.

Dan's first cottontail was the most classic, as he was standing on the hillside overlooking another draw when the bunny decided the dogs were getting too close. He skittered between trees into two clearings. Dan saw him cross the first, and popped him when he got into the second. It takes some pretty fast gun handling

When I asked Dan about how the chase goes, he explained that the dogs don't get a rabbit and run him by you in a nice straight line. They just roust the rabbits, make them move from one place to another, and you have to be somewhere near and spot the movement. It was only a few minutes later that I saw the three cottontails scatter, and his explanation became clearer.

Jim has been working with beagles for 30 years as a member of the Pine View Beagle Club at Omaha. He believes that training of a beagle should start when about four months old, preferably taking him to a field with bunnies. He suggests working until a rabbit is kicked up, then putting the dog's nose into the set and trying to coax him to get interested in the scent. The oftener this is done, the better.

Jim cautions not to shoot over the dog until he becomes proficient at trailing, but not to become impatient with early nosing efforts. Once the dog is trailing, don't let too much time pass between outings so he doesn't forget, but that is doubtful. Once having hunted with a beagle, one wants to do it often. These short dogs also are good on quail, pheasants, fox, coyote and other game, but for bunnies they are superb. And, they make it a much more exciting and productive sport, for their efficient noses can make up for a lot of human shortcomings. They will, for instance, eventually retrieve almost any cripple, unless it flies away, as they will continue on a trail until it ends. And, they are persistent searchers, following game by scent rather than sight. Ω

photo by Jon Farrar

FISHING...THE WALLEYE RUN

About arrival of spring, old marble-eyes starts heading for the rocks

WALLEYE ARE exasperating fish. They're unpredictable in their movements, finicky in their feeding habits, and incredibly demanding on the angler's store of patience.

So, those rare times when walleyes are concentrated in one place and shed of some of their customary wariness are opportunities no fisherman should pass up. In Nebraska, this optimum time is just about here: the 12 walleye spawning run of early spring.

Not long after the ice leaves the lakes, walleye begin to head for their spawning grounds. They seek shallow areas covered with gravel or rock, where they gather to deposit their eggs. Nearly all Nebraska lakes are man-made affairs, and the only areas meeting these requirements are usually the face of the dams with their lining of rock riprap.

Usually, the best of the spawning run comes in early April in most of our lakes. But, walleye pay no heed to the calendar. The signal they look for as spawning time nears is the right water temperature. Fishermen in the know keep an eye on the thermometer, and when the water temperature edges a couple of notches past 40 degrees, it's time to start fishing.

Generally, this occurs a bit earlier NEBRASKAland in smaller lakes and somewhat later in the big ones. The walleye run at Harlan County Reservoir, the standard by which Nebraska walleye fishing was measured for a lot of years, most often peaks the first or second week of April. The runs in some lakes come a bit earlier, a few are later, and big Lake McConaughy often trails Harlan by several weeks.

Walleye spawning activity begins with the arrival of males at the dam. Usually smaller fish, in the two to four-pound range, the males spend most of the spawning period in the immediate area of the spawning bed.

The females, on the other hand, stay away from the spawning grounds until they are ready to deposit their eggs. Then they move in, scatter their eggs on the rocks (to be fertilized by the males) and leave as soon as the task is finished. The difference in behavior of male and female walleye during the spawning run accounts for the fact that most of the fish taken are the smaller males, and relatively few are the lunker females.

Often, the early part of the run is prolonged by lingering cold weather. This early fishing is tantalizingly slow, usually yielding only a few of the smaller males. But when the water finally warms to the walleyes' liking, the size and number of fish caught improves considerably. The best of the fishing lasts about a week, maybe two, before the marble-eyes quit the dam and scatter to deeper parts of the lake.

But while the walleyes are at the dam, fishermen will use several tactics to put fish on the stringer. Probably the most common is trolling.

This kind of trolling is not the apparently aimless and random chugging along that sometimes passes for fishing at other times of the year. In fishing the walleye run, the helmsman must guide his craft to within a rod's length of the water's edge along the dam. In this way, the lures in tow will bump and scrape along the tops of rocks in just a foot or two of water, where spawning walleye will most likely be.

Some fishermen use an extra long rod and lean over the side of the boat in order to get their lures just a bit closer to the dam. But most get along just fine with more conventional posture in the boat and some ordinary, APRIL 1976 medium-weight spinning gear.

Rapalas or floating lures of similar configuration are the most common choice of trollers, and there are a couple of good reasons. First of all, they catch fish. In addition, the Rapalas track straight behind the boat, enabling several anglers to fish out of the same craft with a minimum of foul-ups. And, the balsawood minnows are buoyant, so that an angler who hangs up on a rdckcan let the line go slack for a few seconds with a reasonable chance of the lure floating free. This saves a lot of time and trouble that would otherwise be spent circling back to free snags.

A few fishermen might try other lures with good success. Some pick the ThinFin and some go for other plastic plugs with rattle chambers, hoping that the noise will attract fish.

No matter which lure he uses, a smart fisherman will make it a point to check his lure and line often. The rocks can quickly wear and weaken the last foot or so of the line, so it is a good idea to snip off a bit of monofilament and retie the lure periodically. Also, the rocks can straighten or dull hooks, break the diving lip or otherwise damage the lure, greatly reducing its efficiency.

If a fisherman is careful about checking his line, eight-pound-test mono will work just fine since most of the fish will be males of from two to four pounds. Even the bigger females that push 8 or 10 pounds can be landed on fairly light line if it is free of abrasions and tied with a good knot.

Another breed of walleye fisherman shuns the boats, preferring to stalk his prey from the insecure footing of the rocks of the dam. These fall into two categories: one casting plugs similar to those used by the trollers, and others flinging an assortment of jigs.

The plug casters also rely heavily on the Rapala-type lure, though they tend to use larger versions than the boatmen. While the trollers generally stick to 2V2 or 3-inch models, the shore-bound anglers often are found tossing lures of 5 inches or more. They often say that walleye prefer the bigger lure, but ease of casting the jumbo plug might also have something to do with their selection.

Most are content with a vantage point at the water's edge, but a few don waders and brave the treacherous footing in the jumble of slippery rocks just off shore. One wrong step could result in a chilly and possibly bruising encounter with the rocks, but some fishermen seem to feel that wading gives enough of an advantage to merit the risk.

The best of the plug casters waste little time throwing lures away from the dam toward deep water. Experience has taught them that this will earn them precious few walleye. Instead, they cast parallel to the dam, scraping the same shallow rocks that the trollers do.

Probing the deeper water is left to fishermen armed with jigs. These fast sinking numbers can work somewhat deeper waters that the floating plugs can't reach. And, they are easy to cast, especially in the blustery winds that often prevail.

Tackle ranges from ultra-light to medium-weight spinning gear, and lure sizes run from 1 /16 to 3/8-ounce. Basic colors of white, yellow and black predominate, but a few anglers also do well on multi-colored numbers like red-yellow-green and red-yellow-black.

During the spawning run, walleys can be taken at any time of the day. The best fishing, however, comes after dark when these nocturnal fish are most active and most comfortable in shallow water. If there is any good daytime fishing, it almost always comes on an overcast day or on a day when wind ripples the water and cuts down on light penetration.

All of the things the walleye likes — the wind, the clouds and the darkness — are the things that exact a stiff price from the spring-run fisherman. Early April is often quite chilly, and it gets downright cold after sundown. Any breeze magnifies the chill and fishermen feel it even more near the water. Even in the daytime the cloudy skies of the best walleye days filter out the sun's warmth.

But, despite whatever discomfort it might bring them, walleye fishermen are eagerly awaiting the spring run. Any day now, a flannel-shirted angler will detect a promising water-temperature reading on his thermometer and the word will spread like the flu. The walleye run will be on. Ω

13

Beauty and the Human Beast

AS I SIT and read books about nature and animals and the life they lead, I think of my own longing for more solitude with them. Sometimes 1 get an emptiness within that 1 cannot explain. It is as though something has passed that I cannot ever be a part of. My dreams are: to someday own land in which 1 can grow food for my table, raise cattle and still be surrounded by woodland creatures such as deer, fox, squirrel, woodpecker, songbird, and rabbit. I dream of having all this in harmony with each other, and yet separated from the outer world.

I believe that if we lose the serenity and tranquility of the woodlands and forests and of the creatures that abound and belong in them, that we lose a part of ourselves that was present when the Indian inhabited and coexisted with this 14

Maybe I am not being fair with my appraisal of progress, but I cannot help feeling the loneliness that sometimes 16 creeps into the back of my mind when I descend upon a beautiful, wooded area, devoid of houses and man s litter and other 'inventions and think to myself about this being all gone someday and my children not being able to inhale the beauty and peacefulness of it all. Maybe I am wrong and no one will ever say something has forever gone from here. Ω

These woodblock prints are by Amy Sadie, an artist formerly of Hawaii and Cuba, now living in Nebraska. Her work has won many awards and has been exhibited at such places as Joslyn and Smithsonian. For interested persons, her address is Rt. 2, Mitchell, NE. NEBRASKAland

Arbor Day: A Sterling Idea

From native species to exotics, Morton saw tremendous value in tree planting, and his pioneering efforts are still bearing fruit

STERLING MAY not always refer to silver. In Nebraska it may well mean trees; J. Sterling Morton trees, that is.

When General John Fremont scouted the plains, only a few scattered cottonwoods and a couple of sleepy willows bordered Nebraska's flat waters.

It seems possible that when J. Sterling gazed west beyond the Missouri, he wished for a few eastern seedlings in his pocket. He saw thick, grassy prairie, from the wide valleys to the bluffs, with hardly a tree in sight.

This picture was to change soon. After becoming editor of the "Nebraska City News" in 1855, Morton homesteaded 160 acres of fertile land on the west edge of Nebraska City which later became Arbor Lodge. Morton's dream sprouted into reality as he explained in his newspaper the need for trees. Trees became a valuable friend to settlers, providing wind breaks, fuel, shade and lumber.

A resolution was presented to the state board of agriculture in 1872 calling for an annual tree planting day to be known as Arbor Day, and in 1885 the State Legislature declared Arbor Day a legal holiday to be celebrated on April 22.

Memorial tree plantings and the dedication of trees has long been a part of the Arbor Day celebration. Former President Grover Cleveland planted a white ash at Nebraska City in 1905, and that party was so enthusiastic that several other trees were planted before the ceremonies ended. A row of 28 sugar maples on the east end of the park was dedicated to veterans of World War I in 1925, and 69 pin oaks were planted to commemorate World War II veterans in 1947. Presidents, governors, agriculturists and leading members of society have 18 been a part of Arbor Day, but the true reason for celebration is trees.

Trees from across the United States and the oceans are residing at Arbor Lodge. The Algerian fir is the rarest species on the grounds. It is the only tree of its kind known to be in the United States. Other thriving trees not native to Nebraska are the mountain dwellers. Engelmann spruce, with gray-green foliage and cone-shaped crown, lives well in mountains and on plateaus where soil is rich and where it is protected from high winds. The ponderosa pine also does well in Nebraska soil, but does not tolerate permanent shading. Hardy and resistant to cold is the Norway spruce. It grows successfully in Nebraska soil but requires much moisture.

Delicate ornamentals also adorn the park grounds. An unusual yellow lilac has been recently planted and is one of many lilacs that disperse their perfumed fragrances in spring breezes. Native to Kentucky is the umbrella magnolia tree. Preferring moist, fertile soil, this magnolia tree bares creamy white blooms that measure 6 to 10 inches across. A bald cypress, the picturesque representative of southern swamps, is also at Arbor Lodge. Known to attain an age of over 1,000 years, the bald cypress grows well on drained, upland sites.

The list of residents includes a stand of American Chestnut trees. One of the largest pockets of this species left in the world, it has so far escaped the dreaded chestnut blight. Its seeds are mailed to arboretums in other parts of the United States in hopes that one day the species may again flourish.

Arbor Lodge also boasts the biggest black walnut tree in Nebraska and perhaps the midwest. The black walnut is a tree prized in many ways. Its wood has been desired since pioneer days for furniture making and gun stocks. The nut is somewhat sweet and offers a distinctive taste that is much in demand for cakes and cookies. The hulls of the nut were even used as a dye by pioneers. The black walnut prefers rich soil and may be grown quite easily by planting the nut, hull and all, in three to five inches of soil.

Another member of the nut family at Arbor Lodge is the American beech. It is more commonly found east of the Mississippi River. The sweet, edible beechnut is utilized as food by many species of wildlife.

There are many other trees at Arbor Lodge with intriguing stories behind them. Trees are a part of all our pasts and monuments to our future.

On the first Arbor Day, J. Sterling Morton wrote the following to the Omaha World Herald: "How enduring are the animate trees of our planting! They grow and self-perpetuate themselves and shed yearly blessings on our race. Trees are the monuments I would have. The cultivation of flowers and trees is the cultivation of the good, the beautiful and noble in man".

Morton left the world with this thought, which is inscribed on his monument at Arbor Lodge: "Other holidays Repose Upon the Past-Arbor Day Proposes for the Future".

Nebraska City will again observe Arbor Day festivities with many set at Arbor Lodge State Historical Park. Activities will be April 23 through 25, with many old-time crafts, games, concerts, and outdoor demonstrations. A parade Sunday at 1 p.m. starts downtown and ends at the Lodge, and most Saturday sessions will center at the Lodge, including an outdoor carnival. Programs are available from Arbor Day Foundation, Arbor Lodge 100, Nebraska City, Nebraska 684 W. Ω NEBRASKAland

The Wild Edge Life of a Marsh

THIS IS THE terrifying last vision of life for countless small creatures in and around a marsh: the sudden, sun-blotting rush of fierce eyes, an inescapable clutch of daggers.

After consuming the blackbird fledgling, the marsh hawk lifts again into the wind, quartering away in its erratic butterfly-like flight over the leaning acres of reed, cattail and bulrush.

The Indians called marshes the between-land, a region that is neither land nor water. It is a transition zone, a band of emergent vegetation that separates and combines the opposite worlds of dry land and open water.

Ecologists recognize the importance of such transition zones between differing plant and animal communities. Just as more wildlife can be found along the boundary between meadow and forest than in either of the two separate zones themselves, so will an acre of marsh support more life forms than an acre of prairie or an acre of open water. The principle is known as the edge effect. In a dry region, such as the sandhills, a marsh is especially significant, serving as an oasis for prairie animals as well as a refuge for wetland creatures.

Marshes also represent another transition; they are the final stages of lakes becoming land. Marshes are dying lakes, and the extent of emergent vegetation is an indicator of the succession progress. When young, lakes have little shoreline vegetation. But as emergent plants become established, the organic debris they produce beginstofill in the lake bottom. Gradually the shoreline shrinks, extending itself toward the center of the lake. Eventually the water is excluded entirely, replaced by a rich deposit of loam.

But while the marsh lives, it provides a habitat for waterbirds, amphibians and water-associated insects, mammals, reptiles and vegetation that otherwise would be out of place in the drier surroundings.

The marsh hawk reappears, trailing a bullsnake, an animal of the dry prairie that now will help sustain creatures reared among the reeds of a marsh. Chased by an indignant male red-winged blackbird, the hawk drops out of sight to its hidden nest.

APRIL 1976 21

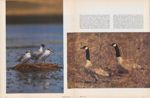

What you remember most about a marsh in spring and early summer is the noise. As if to make up for the long season of ice and silence, the marsh clicks, sings, clatters, buzzes and splashes with the business of bringing forth new life. Contrasted to the occasional life-sounds heard on the surrounding prairie, the marsh roars with its collective sounds. Beiord dawn the quork of the black-crowned night heron is joined by the prehistoric-sounding notes of the male bitterns. At first light all the countless bird territories get announced, from the cheery whisperings of the yellowthroat warbler to the awful raspings of the yellow-headed blackbird. The morning conversations of coots, ducks and grebes form a continual background for the reedy gurglings of the long-billed marsh wrens, the splashing of breeding carp and the clattering wings of dragonflies. The nasal kyarr of the Forester's tern and the ceaseless begging of its young (opposite) are common sounds on remote marshes holding nesting colonies. Once nesting on the central prairies by the thousands, Canada geese (below) find suitable habitat today mostly on the northern prairies. They are early nesters, bringing forth chicks while other marsh birds are still migrating or engaged in courtship and nest building. Chicks are vulnerable to unseen predators such as the snapping turtle.

APRIL 1976 23

A marsh attracts many animals of the open prairie. A jackrabbit, badger or rattlesnake might be seen drinking at the water's edge. Not surprisingly, predators such as the coyote, fox, skunk and raccoon find good hunting along the borders of the densely populated marsh and regularly patrol its edges. Even a great horned owl is occasionally tempted to sample muskrat. Deer are frequent visitors to the marsh, wading among the reeds to drink and escape the heat, and bedding down in the cover of tall grasses along the marsh fringes. The exchange is not all one-sided, however; marsh hawks also exploit the surrounding landscape for prey, and bitterns lead their young to meadows for the easy taking of grasshoppers. The edge between marsh and prairie is so fine that a meadow vole and kangaroo rat may cross paths and a red-winged blackbird and bobolink exchange song.

NEBRASKAland

Few people learn to appreciate a marsh. Unlike lakes and rivers, they are not conducive to water sports. Choked with vegetation and smelling faintly of decay, marshes are reviled for the mosquitoes they produce. Occupying low, level sites, they early lost out to the transportation engineers, who sought to lay track and highway along the valley and river bottoms. Farmers soon discovered that the soil of a drained marsh produced excellent crops.

By the turn of the century, approximately 127 million acres of wetlands remained in this country. By 1950 the total had dropped to about 82 million acres. No one knows the current total, since no recent, comprehensive survey has been conducted, but the trend continues. Only recently, through campaigns by private and federal agencies, have the "useless" wetlands —those not included in the 20 million or so acres recognized as significant in waterfowl production —come to be popularly regarded as valuable wildlife habitat.

APRIL 1976 27

Every plant and animal community develops its own characteristic food chains —the multi-step process that transfers and concentrates energy — from myriads of single-celled algae to the community's top predators. Since the warm, shallow waters of a marsh produce great amounts of vegetation — the foundation of all food chains — it is not surprising that plant-eating animals are also present in great numbers. These, in turn, support various levels of carnivores. The long-billed marsh wren (above) is a common marsh predator, attaching its roofed, ball-shaped nest to reed stalks and subsisting on the multitude of insects that a marsh produces.

A food chain maybe simple or complex. In the harsh regions of the earth, where animal species are few, food chains are necessarily short. But in a teeming marsh the transfers of energy may be many; the food chains complex. Warm, shallow waters abound with aquatic insects, which help to support higher life forms. Even on this small scale, competition is fierce and predation severe. In the top photo, a predacious diving beetle has captured a smaller cousin. Using its proboscis to puncture its victim, it sucks out the body juices. The smaller predacious beetle becomes a link in a complex food chain that may undergo many more energy transfers until the frog eats the beetle and the snake eats the frog, and is finally speared by a great blue heron, completing the food chain. The mink (above) is another common marsh predator that feeds on muskrats, crayfish, bird eggs and fledglings, and whatever else it can catch.

APRIL 1976 29

A marsh produces such a spectacular display of life during the summer that it seems impervious to recession. In the evening sun, swarms of midges choke the air, looking like distant dust columns. As always, a great blue heron appears at daybreak to haunt its favorite hunting spot, standing motionless^ aryd austere until stabbing down to spear frog, fish or snake. Fat with the plenty of their neighborhood, bullfrogs lie awash in the cooling water, listening to gangs of blackbirds pillage the cattails. Every animal, above and below the water, goes about its own cycle, unattached yet interconnected with every other, unaware of its own vital niche in its community. Some, by eating plants, convert the sugars and starches of stored solar energy to animal protein, thereby making their flesh a resource available for exploitation by other animals. In the black, malodorous muck of the marsh bottom, bacteria reduce what the predators and scavengers have left behind, breaking down complex proteins to simple compounds that plants can again utilize, so that the life cycle, like the seasons themselves, continues, the coming winter will shut down the marsh, level another generation of reeds, exile the water birds, and seal off ihe diminished aquatic world, imposing silence, ice and death. But of all earth's habitats, marsh is the oldest, most durable.

THOSE DAM CATS

Young channel cats on the rocks are perfect fishing companions

SOME FISHING expeditions come about after long planning for a special occasion, such as vacation time or a trip scheduled to take advantage of a particular species when they are more vulnerable than usual. Others are spur-of-the-moment affairs resulting from chance encounters with other fishermen.

One particular outing that certainly fit into the happinstance category was a few years ago in Lexington during a trip to somewhere else. It was about mid September of 1973 when I ran into Ron Meyer, who has no little reputation as a good fisherman, and one that is very much deserved.

His experience has been hard earned, as he spends plenty of time and has learned from those many days working nearly every kind of fish available in mid state.

There is something smacking of burglary when I accompany Ron fishing, for I cannot help but feel I am capitalizing on his efforts, but that doesn't stop me from going. Perhaps that is the way most of us have to operate—taking advantage of those who know what they are doing so we can learn from their past mistakes and successes.

Anyway, it was a near perfect day even if the fish didn't bite. It was calm and warm and clear. Ron suggested that catfishing might be good at Johnson Lake, and that sounded good. Now, I have fished at Johnson Lake many times, at the inlet, outlet, trolling and sitting on a dock, but I had never fished the face of the dam, which is where we ended up.

First, though, we went to the inlet where Ron rounded up a supply of two and three-inch shad to be used as bait. Those little critters are so fragile they don't survive long after being caught, no matter how carefully handled, but apparently the catfish don't mind in the least.

It was late morning by the time we arrived at the dam and clambered down the rocks to the water's edge. Then, it took a while to prepare gear for the anticipated action. Ron showed me what to do, and our other companion, Ron's uncle, Richard Meyer, already knew.

Richard is from West Palm Beach, Florida, where he has fantastic fishing nearly at his doorstep, yet he comes to Nebraska each year for a month of fishing here. Ron always takes him on a tour of the area so that he can sample several species offish, and doubtless they have better than average success.

Well, there we sat, perched on the flatest rocks we could find, basking in the sun and admiring the scenery. The water was extremely calm under the protection of the dam, and glassy water is always more fun to fish.

Our rigging was relatively simple. Ron slipped on a sliding sinker, pinched on a split shot to keep it about a foot or so above the hook, then baited up with a shad on a medium-small hook. Then we tossed out about as far as (Continued on page 44)

TREES! planting for the future

"Trees will repay you" is horticulturist message

WHEN THE Nebraska Game and Parks Commission expanded its habitat planting program in 1968, Hans Burchardt was hired to head the effort. He was then 65 years old, and just retired from a decade of work in plant propagation and research at the University of Nebraska. For him it was the beginning of yet another career in the horticulture field. Behind him were years of training and study atthe University of Berlin in Germany, 15 years of managing plantations and conducting botanical research in equatorial West Africa, six years of work as a German intern on a British citrus fruit/coffee plantation in Jamaica and years of experience in commercial nurseries in both Missouri and Nebraska. He was a seasoned horticulturist; precisely what the Game Commission required for the monumental task of establishing arboretums and nurseries, and supervising the planting effort on many wildlife areas across the state. Hans retired again last year, at the age of 72, but he still works almost daily as a Game Commission consultant, tending the programs he started. In February of 1976 he was selected to receive the first Forest Conservationist of the Year Award, given by the Nebraska Wildlife Federation. His thinking has been a strong influence on the Commission's habitat planting program. His plant culturing techniques have been innovative; imitating and encouraging nature's own scheme. In the following interview he explains some of the values of trees for Nebraskans, a message especially appropriate for this Arbor Day month.

Arbor Day is just a few weeks away. What are the benefits of planting trees in a prairie state like Nebraska?

Any kind of vegetation, whether it is a tree, shrub, grass or whatever, is somehow important. Vegetation is a living element of our environment. More and more we are moving away from natural conditions with our modern farming, modern living. When possible we should keep in touch with nature.

Trees help maintain the quality of our environment; they clean the air and hold the soil. They keep us alive. 34 We are taking too many of them away. We will miss them someday.

With today's intensive use of the land, can trees compete economically with food and feed grains?

There are areas that are not suitable for farming, along the creeks and between the hills; what I call the hill crotches. These are suitable sites for trees and shrubs. These areas can form a beautiful pattern of plants on farm and ranch land. By many, trees are considered useless; they are neglected, despised and often destroyed in order to gain a few square feet of farmland, or just to clean up. So senseless! Today this is too easily done with heavy equipment. The spraying and burning of roadsides is also senseless.

Domestic animals can use these wooded areas as protection against the weather. Pastureland without any shady spot for livestock is too common a sight today. It is heart-breaking to see cattle lined up under a billboard, the only shade available in a pasture. We do not care about our animals' comfort. A tree or small group of trees would give comfort, would reduce loss of animals and would add natural beauty to a farm.

If not for economic return, why should anyone expend the time and money to grow trees?

About 40 years ago a farmer named Caha started planting trees on his land southwest of Wahoo. He planted about 20 acres on an east-hanging slope just for a hobby. Over a number of years he put out two or three varieties of pecan, two or three varities of black walnut, persimmon, apricot, hazelnut, two or three varieties of hickory and several varieties of chestnut. Later he added 15 to 20 varieties of apples, grapes and peaches. As he grew older he didn't have time to care for it, and it grew wild for years.

Most of the original trees are still there. Hickory, pecan, walnut and persimmon are in good condition. These are plants that no one knew would survive this far north and west. They have grown wild, luxuriantly, with very little or no human help. This man did it the right way; a true multiculture of trees. Today, the

offspring of the parents that he planted

are hybrids. Some are excellent, with

big fruits. It is as I said —out of thousands of seedlings there is one outstanding plant. The Caha orchard is a

kind of cradle for a whole new generation of trees. They are the children

of this soil and this climate; a natural

intercrossing of quality parent plants

with parental characteristics in adaptation to this newly conquered territory. That is important.

offspring of the parents that he planted

are hybrids. Some are excellent, with

big fruits. It is as I said —out of thousands of seedlings there is one outstanding plant. The Caha orchard is a

kind of cradle for a whole new generation of trees. They are the children

of this soil and this climate; a natural

intercrossing of quality parent plants

with parental characteristics in adaptation to this newly conquered territory. That is important.

This man enjoyed plants. He did not ask, "who will pay me." He was not trained; an average farmer, but a naturalist. He loved nature. He invested money without counting on it coming back. Today we are too concerned with money. People such as Caha are disappearing.

The important thing with plants is to start them, see them grow, and your knowledge will grow with them. They will let you make some mistakes. One should not forget that plants are alive. You can do a lot wrong and they will take it; they don't give up. With a car engine or what else, you do something wrong and it is out. The car does not help you, it is not alive. That is what is wonderful about plants. They help you.

What type of trees are especially well suited to Nebraska?

Whenever possible use native species. They're best adapted to our climate and soils. In eastern Nebraska the maples, boxelders, mulberry, ash and poplar are good. In the southeast, hickories, oaks, especially the red and black oak, and the walnut are good trees. The number of trees suited to the Sandhills and western Nebraska is more limited.

In the Game Commission we use "pioneer plantings" to establish trees in unfavorable areas. We start with trees that grow easily, and in their protection we blend in the more valuable, less hardy species. Poplars, willows, junipers and pines are excellent pioneer plants. Russian olive and ash can work some places. Hardwoods and fruit trees need wind protection and more moisture and can be planted several years later.

Do mixed plantings grow better than stands of one species of trees?

A healthy mixture of species is the Alpha and Omega of planting trees. Intermixing avoids exhaustion of the soil. Plants are taking and giving to the soil. A monoculture of trees is only taking. Mixed plantings are in balanced harmony with the environment; it is nearly everlasting. I have seen 5 to 10-acre stands of solid walnut.

Mixed planting is one way we can cut down on the use of chemical pesticides. The disastrous effects of disease, fungus and insects on our plant crops could be reduced by elimination of monoculture. Solid stands of one plant type are inviting trouble. By having a mixed planting we may lose some of our crop but never all. Look at what happened because for years we planted nothing but American elms in towns.

In the beginning when you put plants together, it seems that some are a little bit hostile to each other, but plants are alive and they want to stay alive. After a while they come to a settlement, they are in harmony. The hostile plants, the ones not compatible in the association, are gone and you have a perfect stand of plant species that love to grow together.

What have you found to be the best arrangement for planting trees in Nebraska?

Any kind of planting should be done in blocks, with the trees close together. A close stand triggers a healthy growth habit. The trees race upward for sunlight. They succeed best in competition. This is how trees grow in nature.

There is an immense variation among plants of the same species. Some seedlings are weak, some are strong. In a close stand the stronger ones, with the best genetic characters, survive and become the "future" plants. To me it is wrong to give juvenile plants the space needed by mature plants. Competition growth is triggered only by close plantings. They chase each other up. Trees that stand alone are not vigorous —they are cripples. They just sit there; they are not forced to grow.

Just as animals huddle together in rough weather to survive, so, too, do plants. The impact of the wind is reduced in a close stand. Look at how APRIL 1976 the blocks of old Homestead plantings have survived in the Sandhills. In our windswept Nebraska this is very important. This is the only way for trees to colonize the hilltops; to start at the bottom and let them creep over the top in the protection of others.

You say that native tree species grown in local nurseries perform the best in Nebraska's climate. Many nurseries sell trees \hat were grown in southern states and shipped in. How do you know what you are buying?

It costs more to raise trees in Nebraska than it does in the south. Too much our nurseries are set up to handle quantity, not quality. Partly that is because Americans do not recognize good plants and want to buy as cheaply as possible.

Locally raised trees are adjusted to the climate and soil. They transplant more successfully. It is not so much of a shock for them. Shipped-in plants might be too delicate with too luxurious a growth to survive here. For example, the English walnut that is shipped in, even those from Oregon, were raised in a more balanced, moist climate. They are not able to take the harsh Nebraska winters and dry summers. I have grafted the English walnut on the black walnut. The black walnut is winter hardy and survives. By grafting you give the English walnut the black walnut's stamina. These are the kind of plants we need here, but the nurseries are not doing it.

Seed material or plants from nurseries farther north generally do better here. There are some good midwestern nurseries but you have to look for them and ask what their tree source is. Don't be afraid to pay a little more, the trees will repay you. Ω

ANYTHING FOR A HORSE

It was 1890 and there had been no trouble with Indians. But, that was about to end for some cowboys

MY FATHER, Sam Lawyer, was a born horseman. There wasn't a time when he wouldn't have traded everything he had for a horse. And it wasn't because he'd been born into a horse-loving family either. His hard-headed Dutch father thought spending money for a riding horse was downright ridiculous. But even so, as a kid in Rushville, Missouri, Dad had managed to wrangle a good saddle horse for himself.

When Grandad Lawyer sold out his Missouri farm and headed west for the free, homestead lands of Nebraska, everything that the family could take was piled on two wagons, one drawn by a team of good horses and the other by a pair of strong Missouri mules. Dad's two older brothers, Edgar and George, had never cared about riding horses so they were mostly the teamsters for the outfit. Dad rode his horse and herded the family livestock. He never said much about the trip except that he was glad he hadn't had to walk, as his mother usually did.

It was an easy drive west after crossing the Missouri, and Grandad Lawyer took up a homestead near the little town of Gothenburg. From then on the fun was over and it was nothing but work—hard work. Logs had to be cut and hauled from the hills. A log house had to be built. The long hard task of breaking sod to farm land claimed everyone's life from dawn to dusk. Dad stayed on as long as he could stand it, but he wasn't cut out to be a farmer. He didn't mind hard work if he could do it from the saddle of a horse but he didn't intend to walk behind one, furrow after furrow.

One night Dad decided to pull out. He tied a blanket on behind his saddle, mounted his old saddle pony and rode away from home —for good. Dad had no doubt about the kind of work he wanted to do. He was a born horseman and a good hand with cattle so he headed for Ogallala, Nebraska. The APRIL 1976

It just happened that when Dad got into Ogallala, this cattle company had just bought a big Texas trail herd and was loading supply wagons for its western ranges. Fortunately for Dad, who didn't have a dime in his pocket, he was taken on immediately as a cowhand. They fitted him out with a new lariet, new clothes, boots and a bed that had a canvas tarp to turn the rain and snow and keep his bed dry. They also issued him a six-gun with ammunition and holster — standard equipment for all their men at that time. (I don't think Dad had it long enough to shoot it, though.) When the big herd and supply wagons pulled out Dad rode with them, ready for anything —except what actually happened; a long walk back.

Since it wasn't too many miles from Ogallala to the main, western ranch which was located on the North Platte River, about where the town of Mitchell is now, Dad didn't have time to get well acquainted with the other hands. He might have heard a few comments about Indians if he had, or even about what was happening to the cattle market. As it was, Dad just prowled around the big ranch headquarters.

The ranch house and barns were built of stone. There was also a stone corral with a high fence. There were many ports in the attic of the ranch house, also in the barn and corral. That the ranch was built that way to protect it from Indian raids went without saying. It was built like a small fort and the Indians couldn't set fire to the buildings.

Well, those old buildings are still standing, or were when I was there in 1933.

Anyway, Dad wasn't at the stone ranch very long because a round-up wagon was ready to pull out and Dad was assigned to it. That round-up wagon was to work the range south into the Wildcat Hills, the southwest section of Nebraska, and from there up into eastern Wyoming, the part known as the Chugwater Creek and Goshen Hole country. This must have been about the year 1890.

Many things were destined to happen that year. Wyoming was to be admitted to the union as the 44th state. Homesteaders were to swarm over the grasslands, fencing the waterholes and plowing the big, open, free ranges, dooming the big cattle barons. It was also to be the year that old Sitting Bull, chief of the Sioux Indians, organized a rebellion on the reservation. Sitting Bull had many of his warriors armed and primed to go.

A religious unrest had swept over the reservation and a group called the Ghost Shirt Dancers believed a great Indian Messiah was coming to the Dakotas who would sweep away the whites. Many of the Dakota Sioux believed Sitting Bull was this messiah. The Indian police, members of the tribe on the U.S. payroll, kept a close watch on old Bull and when they discovered he was getting ready to make war they rushed his lodge and told him he was under arrest. But Sitting Bull wouldn't submit. (This is what Dad heard later.)Old Bull grabbed a rifle and pulled down on the police. It didn't do him any good, however. He was shot and killed in his tracks.

But that wasn't the end. The shots and sounds of confusion, the wails of the women, the hollering, stirred up Sitting Bull's horse. It was a trick horse that Buffalo Bill Cody had given old Bull when he'd been in Cody's Wild West Show. The horse sat down in front of Sitting Bull's lodge and started to do his tricks. He raised one hoof, then another. He scrambled to his feet and danced to music no one could hear. (Continued on page 46)

39

OLD BEFORE ITS TIME

Will Big Mac's rainbows be gone in 5 years or 50? Computer may give answers to save the tout

IN THIS AGE of computers, those mysterious machines have been used for everything from aiming astronauts at the moon to landing crooks in the slammer. They've catalogued man and his activities into masses of magnetic impulses to store information and digest it into answers for all sorts of problems.

And soon, a computer whirring away in the catacombs of the University of Nebraska will devote its circuits to yet another kind of task, one of vital interest to Nebraska fishermen. That task is a study of Lake McConaughy that may enable biologists to peer well into the lake's future as a trout fishery, and do it with accuracy beyond the dreams of any swami with his crystal ball. Once they know what's in store for the lake's trout, the biologists will be better equipped to make the right management decisions and recommendations.

And, it's imperative that they make proper recommendations and that they are followed. For, if the lake continues on its present course, many of today's young adult fishermen will live to see the extinction of Big Mac's rainbows.

Lake McConaughy is a "two-story" lake, one of the best such fisheries in the midwest. The "two-story" label refers to the fact that Big Mac supports both warm-water fish (walleye, catfish, white bass, etc.) and a cold-water species (rainbow trout).

It's the cold-water portion of this lake that has biologists most concerned. As the term implies, cold-water species require cooler temperatures to survive. And they also require well-oxygenated water. In Lake McConaughy, the rainbows can take water no warmer than 70 degrees fahrenheit, and must have at least 3 parts per million (ppm) disolved oxygen.

From mid-fall through winter and spring and into early summer, Big Mac's rainbows are able to find favorable temperature and oxygen conditions throughout most of the lake. But come summer, a phenomenon called stratification (see "Physics and Phish", July 1974, NEBRASKAland) severely 40 NEBRASKAland

In brief, stratification occurs when water warmed by summer temperatures stacks itself atop the colder water in the lake. The warm water, usually in the 70's and upper 60's, does not mix readily with the colder, heavier water below. This layer of warm water thus creates a "ceiling" on the trout population, above which 42 the cold-water rainbows cannot long survive.

Wind, exposure to the atmosphere and an abundance of living microscopic plants, keep this upper layer well supplied with oxygen and life is easy for the warm-water fish. But, since the colder waters do not mix easily with the warm and oxygen-rich upper layer, trout living in the cold water must depend entirely upon the supply of oxygen that was in the water when the lake stratified.

This would be no problem for the trout if all they had to contend with was the temperature "ceiling'' above them. Usually, this ceiling is located somewhere in the neighborhood of 40 or 50 feet below the surface, and Lake McConaughy is as much as 145 feet deep in places.

However, a biological "floor" rises NEBRASKAland from the bottom of the lake and crowds the trout against the ceiling in an ever-shrinking band of life-supporting water. The "floor" is oxygen depletion, which begins in the decaying vegetation and other matter on the lake's bottom and expands toward the upper layers of water as the summer goes on.

Each year this crowding effect gets more pronounced in Big Mac, so much so that the end of the lake's trout population might be approaching. In fact, the most pessimistic estimates of biologists say this could happen in as little as five years if the present trend continues, while the most optimistic say that trout populations there might survive as long as 50 years.

Biologists know the cause of the lake's problems, however, and they might be able to deal with it to a certain extent. The simple fact is that Lake McConaughy is aging; a natural process for all bodies of water. But, as with so many other waters, Lake McConaughy is growing old long before its time through a process called eutrophication. This accelerated aging process is brought on by an abnormal level of nutrients flowing into the lake in the form of man's pollutants, mostly agricultural fertilizer, and to a lesser degree, sewage.

Nutrients, mostly nitrates and phosphates, greatly increase the fertility of a lake and boost its production of plant and animal life. However, fish and rooted plants make up a minute portion of this production. Most of the living matter in a lake is in the form of microscopic plants and animals, giving the lake a "pea soup" appearance. The fertility of a lake's waters, and other variable factors such as temperature and light penetration, determine just how great this over-production of "spinach" will be.

In itself, all this extra "salad" is not much of a problem for trout. But when these things die and settle to the bottom, their decomposition uses up the oxygen at the lower depths. With greater productivity each year, there are more and more tiny plants to die, using up more and more of the cold-water oxygen that trout need.

Lake McConaughy's eutrophication problem is growing rapidly, and with it, critical summer trout habitat continues to shrink dramatically. In 1970, the layer of trout-supporting water was about 32 feet thick, comprising nearly 22 percent of the lake's volume. Since then, summer stratification has produced periods when trout habitat was reduced to a layer only about three feet thick and extending less than half of the lake's length.

If nothing is done to change the situation, the future seems bleak for Lake McConaughy's rainbow trout fishing and the angling along North Platte Valley streams during the spring and fall spawning runs. And if something happened to Big Mac's trout, it would be a severe blow to trout fishing in Nebraska, since that lake's rainbows represent about 75 percent of the state's total trout fishery.

However, biologists have not yet thrown in the towel. They have a good grasp of the process of eutrophication, but it will take help from the world computers to convert this into practical recommendations.

At first, it might be hard to understand just what value computer technology would have in working with trout. After all, fisheries management and a lot of other biological endeavors are inexact sciences and would seem hard to express in terms of numbers. However, each of the processes contributing to eutrophication have been well enough researched over the years that they can be dealt with mathematically, thus making use of computers possible.

What makes the computer absolutely essential in this operation is the extreme complexity of the problem and the machine's ability to deal with a staggering number of calculations in just seconds. Consider for a moment just one of the many factors dealing with Lake McConaughy's eutrophication —the entry and distribution of heat into the lake.

Don't let the following formulas frighten you. You will not need to understand the mathematical calculations. They are simply presented to give you an idea of the complexity of eutrophication. Lake McConaughy's "heat budget" would look something like this:

Qt=Qs-Qr-Qb-Qh-Qe-Qv... Where: Qt is the increase in heat stored in the lake, Qs is the solar radiation at the surface, Qr is the reflected solar radiation, Qb is the back radiation, Qh is the heat convected into the lake, Qe is heat lost through evaporation, and Qv is heat gained through advection.

That one's not so tough to understand, but it doesn't mean much until plugged into this one, which tells of heat distribution at various depths.

\frac{{\alpha T}{\alpha t}} | z = \varphi\frac{{\alpha^2T}{\alphaZ^2}} + \frac{{\alpha}{\alphaZ}} [E(\frac{\alphaT}{\alphaZ}}] + H \div PC

Where: z equals depth, T equals temperature, t equals time, \varphi equals 0.0014 cm2/sec the molecular diffusivity, E is the vertical eddy diffusivity, H is the amount of heat coming into the lake, P (=rho) is the density of H2O (=1) and C is the heat capacity of water.

Understanding these formulas is not important to the layman, but they do give an idea of the enormity of the calculations involved. Besides this "heat budget", there will also be a formula to calculate the lake's dissolved oxygen and another to figure the buildup of nutrients. These three major formulas are interrelated, and in combination make up a mathematical "model" of lake McConaughy's trout habitat.

The model will be like a mathematical blob of jelly. Poke it in one place and the whole thing will quiver. For example, look at the heat budget equations. A small change in one or two factors, like cloudy weather reducing solar radiation or hot, dry winds increasing evaporation, will change the entire heat calculation and be reflected in the results of the other components of the model. There are any number of changeable conditions, all expressed in the model. Yet, the computer will be able to handle all combinations of these variables with ease, a task that would probably keep every pocket calculator, adding machine and abacus in the state humming for weeks.

The model is not yet a reality, however. Much of the information needed to put it together is available from the work of other researchers. But much field work and evaluation are needed to adapt this work to Lake McConaughy, and to derive new formulas. Over the (Continued on page 44)

THOSE DAM CATS

(Continued from page 32)possible and let our offering lie on the bottom. I don't recall how deep it was out there, but probably only about 15 feet or so. It must have been about right, because within 10 minutes Richard had the first fish, a channel cat that easily went three pounds.

Any success is cause for enthusiasm, and that nice a fish stirred all manner of expectation. Of course it was Ron who landed the next one, although it was a little smaller. But, activity was not to stop there. Action was not fast, but it was about as pleasantly consistent as any I can remember. Every few minutes, one of us would have on a fish, and every fish was fun for all of us. And, most of them were roughly the same size, running from just under two pounds to nearly four.

After the initial excitement had calmed, we had time to look about us a little, and we noticed fantastic numbers of shad in the shallow water near shore. Seemingly endless ribbons of them, perhaps two to three feet across, passed by. They were thick, so many millions it was boggling, and they continued to go by.

Although I hadn't seen such a display before, Ron insisted that several reservoirs had like numbers, which enabled the white bass to prosper. It seemed that it must be a bumper year for shad, but maybe they are always that evident in the fall. It surely would be no trouble for a predator fish to find a meal with that sort of delicacy on hand. Game fish would certainly gorge themselves as long as possible, packing on pounds and encouraging their own population boom.

Just as the shad were thick along shore, they must have been elsewhere, as several times during our stay, schools of white bass moved into the calm water about 40 yards out and attacked a batch of shad. That is an unmistakable event. I naturally tied on a silver spoon and tried to fool some of them, but to no avail. They were not as frenzied as their usual feeding sprees, so we assumed they were already stuffed with shad and were only hitting because they were there, and were not seeking them out. It was still fun to watch the activity in calm water, and we enjoyed having them around.

But, the attitude of the white bass tended to remind me that we were fishing for catfish, so it was back to tending that pole. Several times I had noticed gentle nuzzling, but there was never anything on the end —usually even the bait was gone. I have always had trouble with sneaky nibblers, which walleye often are, and those picky cats. Yet, all I could do was pretend I didn't care when the other guys kept dragging them in. Anyway, I got enough that I wasn't skunked, which is a rarity.

44When I kept casually conning Ron into removing the cats from my hook, his uncle told about an incident shortly after he moved to Florida. He naturally went fishing soon after arriving there, and landed one of the local catfish, which are a different breed altogether. While wrestling with it, he stepped upon its carcass to remove his hook, and one of the horns promptly penetrated his crepe sole and entered his foot.

Although it hurt a lot for a few days, he never had it taken care of except at home. Then, a while later a neighbor told him to be very careful as those catfish have a poisonous goop on them. Richard then worried, but figured his crepe sole had been snug enough to squeegee most of the toxin off the spine before it got to his foot.

Luckily, Ron continued to remove my fish, even though he and Richard were both pretty busy on their own, as they had been regularly unbuckling their own fish. About every 15 minutes or so, a fish would pull on someone's line, and it just happened they must have moved in from the wrong direction for me, or were out just a bit farther than my line most of the time.

After a couple of hours the wind picked up some, and it wasn't hard for it to cool off that time of year, but the dam apparently gave us protection, as the water didn't get ruffled much until about 100 yards out.

Once the freshening wind had been discussed at length, the conversation got back to fishing, and I asked Ron about some of his other hangouts. It always pays to glean as much information as possible from those who know. I asked about the Tri-County canal south of Lexington, which is one of those places that Ron visits fairly regularly during certain times of the year. And, fall seemed like one of them. When most people forgo fishing when temperatures drop and the wind picks up, Ron can spend hours on end along the diversion which returns water to the Platte, fishing for walleye.

Special techniques are needed to fish parts of the canal, as the volume of water varies from full on to full off, depending upon the season and time of day. The cascading water onto the rocks is impressive

I had happened onto Ron during one of his sessions at the canal, but I could see no obvious difference in his methods from what others might do. He usually used chub minnows with one or two split shot up a foot or two from the hook, and let the works drift around in the roiling water. In October or February, it was not unusual for him to drag in some big walleye—eight pounders.

There is some knack for being able to read the water and know where the fish are most likely to be, but there is more to it than that. Knowing how to rig up, how far out to drop the offering, when to check for missing bait and such things are a matter of fee! rather than hard-and-fast rules. That must be what accounts for side-by-side anglers having a disparity of success from limits to nothing. Of course, Ron is happy with one good fish, but it seldom ends there.

Ideally, everyone would get out as often as desired, and success would then doubtless increase all around. In that case, though, those few occasions which are now memorable for success would not stand out so much. Like that day along the dam at Johnson Lake. The several catfish that I managed to land made it a super day. If I could look forward to such luck on all days...well, maybe that wouldn't be so bad after all.

My stringer still looked rather skimpy compared to either Ron's or Richard's, even though nearly equal effort went into it. There might have been a better showing had I attended my rod more carefully, but more likely it had something to do with care to detail in the rigging, and a better sense of touch.

No matter what some anglers say, you cannot get along with a bare minimum of gear. There are times when one size of split shot just won't work, or when you need a slip sinker, or a larger or smaller lure. Either you have it or you have to borrow or do without. Anyway, with Ron's tutoring and guiding, we had near limits of pan-size catfish, I had learned of a new, productive fishing spot, and had enjoyed a fine day afield when the prospects had been rather bleak. Ω

OLD BEFORE ITS TIME

(Continued from page 43)past two years, water samples and other observations have been made at Big Mac on a regular basis for inclusion in the model, and such tests will continue on a bi-monthly basis for another two years. Among the things tested at the lake are temperature, oxygen content, nitrates, phosphates, chemical oxygen demand NEBRASKAland (amount of oxygen removed by decomposition as well as inorganic reaction), water hardness, alkalinity, productivity as indicated by chlorophyl levels, turbidity and light transmittance.

When you consider the field work, in combination with that demanded of biologists, researchers and computer personnel, the "modeling" of Lake McConaughy represents quite an undertaking. The project is being made possible by a $43,750 grant from the Office of Water Resources and Technology.

Upon its completion, the model will be adjusted by testing it against situations where the answers are already known. Then, biologists will be able to use it to answer a number of other questions. Undoubtedly, the most important is "how long will trout continue to survive in Lake McConaughy under present conditions?"

Biologists will also be able to predict the effects of heavy irrigation drawdown, changes in nutrient levels and any number of other factors. The model should also give some indication of possible success to any steps biologists might propose to maintain water meeting the rainbow's temperature and oxygen requirements.

Little can be done about the inflow of nutrients, since most of them come from agricultural fertilizer carried into the North Platte River by runoff from fields, mostly in Wyoming. Each year, 1,820 tons of nitrate and 325 tons of phosphate enter the lake. Only 400 tons of nitrates and 260 tons of phosphate exit through the outflow structure, leaving a considerable buildup to compound the lake's problems. Unless agricultural technology or farm economics cause a change, this nutrient loading will continue. But, maybe high costs of fertilizers will see farmers use them more efficiently rather than dumping an abundance of the chemicals on their fields and then rinsing them off with an excess of irrigation water.

While control of nutrients seems out of reach, attleast for a while, other possibilities do exist. One of these is manipulation of Big Mac's outflow structure. Lake McConaughy is capable of releasing water either from an outlet near the surface or from another near the bottom.

By making greater use of the lower outlet, it seems possible that some nutrients might be flushed from the lake. Use of the low outlet might also retard the raising of the deoxygenated layer of water that forms the "floor" of the trout's world. And, the upper outlet might be used when hot weather threatens to push the "ceiling" too deep into the lake.

The flexibility offered by Big Mac's two outlets has intrigued biologists for years, but little use has been made of the lower one. Officials of the Central Nebraska Public Power and Irrigation District have said in the past that operating the lower outlet is more difficult, and therefore a bit more expensive than using the upper.

AUTHORS WANTED BY NEW YORK PUBLISHER Leading book publisher seeks manuscripts of all types: fiction, non-fiction, poetry, scholarly and juvenile works, etc. New authors welcomed. For complete information, send for free booklet R-70. Vantage Press, 516 W. 34 St., New York 10001 Why call back home when you travel?...because it's so nice that someone notices when you're away. THE LINCOLN TELEPHONE CO. GUN DOG TRAINING All Sporting Breeds Each dog trained on both native game and pen-reared birds. Ducks for retrievers. All dogs worked individually.

However, with the survival of Lake McConaughy's rainbow trout population at stake, the problems involved with using the lower outlet seem to lose significance.

There are other areas in which biologists can use the model to predict effects of various practices and to protect the trout. For example, development of recreation and summer homes is getting more popular at Big Mac. With homes, there is going to be more pollution and more eutrophicationof the lake unless proper regulations are enacted and enforced. The model can be used to predict the effects of proposed regulations.

In the long run, Lake McConaughy's trout will lose their battle for survival to eutrophication, whether in 5 years or 50. With the aid of the computer and the model being developed, Game and Parks Commission fisheries biologists will possibly be able to maintain the lake's trout for a long time.

But, even when the trout population is nearing the end of the line sometime in the future, the model will continue to serve Nebraska sportsmen. Then, it will tell biologists when it's time to apply their time, funds and facilities toward other fisheries that promise more for the angler. Hopefully, that decision will be a long, long time in the future, thanks to biologists and the computer. Ω

ANYTHING FOR A HORSE

(Continued from page 39)To the watching Indians it seemed he was doing the Ghost Dance. This stirred up the Sioux braves and later some of them got together in small bands and broke away from the reservation to go on the warpath.

Some of those roving bands of Indians raided area homes, killed some of the settlers, burned buildings and either killed or ran off the livestock. A lot of the Indians were rounded up before they got too far, but others were still at large when the old year ended and turned over into 1891.

One of the bands kept out of the soldiers' way and got across the western Nebraska plains, through the Wild Cat Hillsand west to Wyoming, right where Dad's round-up wagon was working. The cowboys knew nothing about a roving band of Indians in the country.