NEBRASKAland

March 1976

Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commision 1976. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska

Contents FEATURES FISHING PANHANDLE TROUT VENOMOUS SNAKES 10 PASSAGE 14 COMEBACK OF A KILN 16 YOUR WILDLIFE LANDS/NORTHEAST A special 16-page, 4-color section about wild public recreation lands 18 NIGHT SAVAGE 35 LAST BREATH OF WINTER 36 A BIRD IN THE HAND NEEDS A BUSH 41 DEPARTMENTS SPEAKUP TRADING POST 49

Speak Up

What About Stamps?Sir / I am writing to request that you clarify a situation relating to the submission of applying for special hunting permits. The application for special permits suggests that an additional stamp be enclosed for the return of the fee in the event the permit is not issued. It is reasonable that the stamp be used for that purpose. However, those that are issued do not utilize the stamp enclosed, but are mailed in a printed, postage-paid envelope. My question is, what disposition is made of those stamps? Lynn Herot Scottsbluff, Nebr. 69361

Sir / My husband and I are not young anymore, but we still fish nearly every weekend, summer, winter and fall, and I would like to pass along an idea of interest to ice fishermen. We use aluminum, web-seated lawn chairs to convey our gear onto the ice, and it also serves as a crutch to eliminate falls. We place large plastic buckets on the seat along with a sack of dry gloves, bait, poles, etc. in the pail, and there is still room for a small metal bucket of charcoal and lighter fluid. The chair slides better than a sled, is not so bulky, folds for putting into the car, is easy to carry, and you can sit comfortably in them when on the ice. My husband carries the auger and drills the holes, as I am not too strong, having had open heart surgery in 1973. But, that hasn't stopped my fishing one bit. Who is afraid of a little cold weather? Not us hardy old folks. Now we supply our grand kids with tasty platters of fried fish that our own kids enjoyed 20 years ago. Lana Hansen Lincoln, Ne

Is She For Real?Sir / In reply to Mrs. R. Foster, Stuart, Nebraska, by another letter I expressed my satisfaction in reading her "Save the Birds" in the March issue of NEBRASKAland. Satisfaction comes from having first-hand knowledge that there are persons like her who actually believe that if we stopped hunting there would be birds galore and that those now living would live happily ever after.

I suggested that she might take camera and have a go at taking her own pictures of the robin she wishes. Perhaps being closer to nature, she might even become interested enough to actually learn the facts about hunting and wildlife production. I have hunted for over 30 years and have yet to see slaughter of all of our pheasants and prairie chickens. I have seen pheasants perish from extreme winters, and I would call that sight terrible. Eldon Marsh Brunswick, NE

Kind WordsSir / The January copy is a masterpiece. We will keep it and cherish it for a long time. We are proud to be Nebraskans. We have so many things going for us. You are doing a good job. Edwin Fahrenholz

Sir / Thank you for Portrait of the Plains. It's beautiful. Luella King Palmer, Nebr.

Sir / We have just received our copy of Portrait of the Plains. I was really fascinated by the beautiful photos. I couldn't resist comparing the picture on page 141 to one I took at Johnson Lake a few years ago. My family goes camping there each summer, and we think its really great. Lori Taborek Crete, Nebr.

Sir / I would like to congratulate you on the excellent January issue of NEBRASKAland. It is one of the most striking publications I have seen in quite some time, and as I have been unable to talk the editor of our magazine out of her copy, would you please send me a copy. I am looking forward to making it an addition to my photographic library. Rob Womack Mississippi Game and Fish Commission

Sir/Can't express how Portrait of the Plains hit me. It took me back to my boyhood days in Nebraska. Your photos of Chimney Rock are great, and so are the rest. I've hunted, fished, trapped and worked and was close to the rock all the time in Nebraska. I'll treasure this magazine for all time. Thanks to everyone. Gilbert Henry Detroit, Mich.

Sir / My copy of Portrait of the Plains reached me last week. It is a piece of art. The pictures are exceptional. The photographers should be proud of their achievement, and you and the art director are to be commended for the style and balance in putting it all together. Congratulations. Marvin Kruse Beloit, Wis.

Sir / I wanted to tell you that I have enjoyed the beautiful Portrait of the Plains immensely. Nothing could be finer. I grew up in Nebraska but haven't been back for many years and did not realize that there were so many fine lakes and wildlife as well as the beautiful flowers. Eloise McCray Long Beach, Calif.

Sir/I just received my "Portrait of the Plains". What a superb publication! I dearly love the monthly magazine and this issue really puts the frosting on the cake. You have a great thing going. Congratulations to all who are responsible. I truly wish our state could follow your marvelous lead. Mrs. Ruth Goldsberry Minburn, Iowa NEBRASKAland

FISHING...PANHANDLE TROUT

Spring and fall, western Nebraska is golden with end of rainbow run

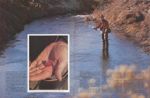

SPRING'S A TIME for beautiful things —a time for birds, flowers, lovers and, of course, fishing. And in Nebraska's Panhandle, spring fishing comes on big and it comes on early, usually well in advance of most tweety-birds and posies.

Big rainbow trout are the main attraction along the scenic tributaries in the North Platte Valley. They come upstream from Lake McConaughy each year to spawn. And, their presence draws anglers from many miles, eager for the opportunity to tangle with rainbow-hued trophies along the banks of these swift little creeks.

The fish that anglers take usually average about four pounds, but eight-pounders are not really rare. And, one whopper rainbow of 13 pounds, 2 ounces was landed one spring from one of these streams, and it held the state record for several years.

Fishermen who ply these creeks speakof "fall" runs and "spring" runs. The fact is, rainbows are on the move in these streams to spawn from early October through sometime in April. However, the bulk of the spawners show up in November and December, and a smaller migration comes in early spring. The spring run often lasts about three or four weeks, usually reaching a peak in late March.

Most of the fish are taken on bait, though a few occasionally fall for a spinner or some other artificial. By far the most popular and productive trout-getter is a blob of trout eggs, taken from fish caught on an earlier outing and preserved in a freezer.

Years ago, fishermen would tediously thread two or three of the

gummy eggs on a fine-wire hook. But,

it didn't take ingenious anglers long to

MARCH 1976

At first, countless of milady's nylon stockings were sacrificed to the higher priority of hubby's trout fishing. Lately, however, other materials of more open weave are being used, including cheesecloth or the lace used to contain the little rations of rice passed out at weddings.

Fishermen most often prepare a batch of these bags in advance and freeze enough of them in containers to supply a day's fishing. The night

At streamside, rigging up for fishing is a simple matter. A medium-size hook, usually a No. 4 or 6, is tied to the end of the line, and a split-shot weight or two is added a foot or so above the hook. With the addition of one of the egg sacks on the hook, the angler is ready.

Fishing techniques vary from one fisherman to another, and so does the choice of fishing rods. Many anglers simply walk downstream using open-faced spinning rigs to cast their offerings-above pools and other likely looking spots. They let the eggs drift along on a tight line so that the strike can be easily detected.

Others will use a long flyrod, with which they swing, lob or dangle their bait into the water. Usually, the flyrod is selected by fishermen who really believe in the value of a cautious approach. Many anglers keep a low profile, keep their shadows off the water, and pussyfoot along the stream like a tabby cat stalking a bird. Others are only moderately sneaky, and some seem downright careless. Yet, each fisherman seems confident with his technique, so they all must work at one time or another.

A somewhat cautious approach would seem the most practical, since it is often possible to see the fish in pools when the water is clear, or moving upstream through riffles even when it's murky. It seems logical that, if the fisherman can see trout, they probably can see him.

The fish may be seen alone or in groups of (Continued on page 44)

VENOMOUS SNAKES

Four poisonous reptiles are found in Nebraska, but seldom are encountered or pose danger

SNAKES ENJOY a special position in man's awareness of nature. This is especially true of the poisonous snakes. The fascination we accord them is a mixture of awe and fear — awe because most of us have had little experience with them, and fear because we know or have been told of the dangers they pose.

Although the poisonous snakes of the United States are generally reported as being of four types (copperheads, coral snakes, rattlesnakes, and water mocassins), there are 19 species of dangerously poisonous snakes found naturally in the United States. Of the 19, 2 kinds are coral snakes; rather pretty, small relatives of the cobras (family Elapidae), and only remotely related to the other 17 dangerously poisonous snakes. These other snakes are vipers (family Viperidae) and are readily distinguished from cobras and their relatives in that vipers have erectile and movable fangs. When the fangs are not in use, they are enclosed in a sheath of tissue and lie folded back against the roof of the mouth. When the snake uses the fangs, they are rotated more than 90 degrees. The sheath covers the fang but is pushed back, exposing the needle-like tooth when the fang penetrates the skin. Several other species of snakes are technically poisonous but their venom is toxic to small lizards, other snakes and insects, and only mildly irritating to man.

Four species of vipers are found within the political boundaries of Nebraska —the copperhead, Agkistrodon contortrix, the massasauga rattlesnake, Sistrurus catenates, the prairie rattlesnake, Crotalus viridis, and the timber rattlesnake, Crotalus horridus. Three are found only in the southeastern portion of the state, but the prairie rattlesnake occurs over most of western and northern Nebraska; as far east as the vicinity of Niobrara along the Niobrara River, but otherwise west of a line connecting Burwell, Broken Bow, Lexington and Holdrege. Over most of the western two-thfrds of the state, the prairie rattler is uncommon, but there are areas where the snake is sufficiently common that one should be aware of the potential hazards —along much of the Niobrara River, the Platte Rivers west of North Platte, and the Republican River west of Harlan County reservoir.

In southeastern Nebraska, we have three dangerously poisonous snakes. The copperhead and timber rattler are found in the oak forests along the bluffs of the Big Blue River in southern Gage County, and along the Missouri River from near Plattsmouth to Rulo (Cass to Richardson counties). Both snakes may have once ranged farther north along the Missouri River and farther west along the Platte, but habitat alteration and decrease, as well as the killing of the snakes whenever discovered, have reduced their distributions to those areas sufficiently rocky and wooded that little alteration of habitat is attempted. In these forested refugia with numerous rock outcroppings, the snakes find many concealment and overwintering sites as well as ample food. In some such areas, both of these snakes are appropriately considered abundant.

In some ways the copperheads are more dreaded than are the rattlesnakes. The greater fear derives from the fact that copperheads have no rattle and thus cannot alert an intruder. Whether rattlesnakes are consciously "warning" us to beware is open to question, but their habit of usually rattling when disturbed earns them unspoken thanks from hikers, ranchers and sportsmen. It is folly to depend on them to warn you; some individuals vigorously rattle at the slightest disturbance while others rattle only when stepped on or severely molested. Because copperheads do not rattle, one can inadvertently get closer to them than might be prudent for the observer or casual passerby.

It is difficult to pin a "most dangerous" label on any one of our four poisonous species. The abundance and wide geographic distribution of the prairie rattler support claims that he be considered the most dangerous. However, the timber rattler is our largest species and can produce the deepest wound with the most venom; but, because it occurs in a smaller area and is generally less abundant, fewer people are likely to encounter this snake. The copperhead and massasauga rattler are smaller, seldom encountered, and are found in restricted habitats; thus the choice of most dangerous lies between the two larger rattlesnakes.

The third poisonous snake found in southeastern Nebraska is the massasauga rattlesnake. This small creature prefers more moist habitats than do the other three species, living in the shrinking remnants of the poorly drained, tall-grass prairies, and further differing by preferring more frogs and fewer mammals in its diet. Unlike the prairie and timber rattlers, the massasauga has a considerably smaller rattle. The noise it produces can be heard over a much shorter distance. The massasauga has been known in Fillmore, Gage, Lancaster, Nemaha and Pawnee counties, but apparently occurs today only in Gage and Pawnee counties. Only 15 to 20 years ago it was reasonably common around Lincoln. It is still relatively abundant at Burchard Lake in Pawnee County.

Our vipers share many features in addition to movable fangs. They are pit-vipers; the facial pit, giving the group its name, is a deep cavity located between the eye and nostril on each side of the head. The pits are oriented so that they face forward on the snake's head (see photos). The pits are heat-sensing devices enabling the viper to detect the direction and distance away of a heat-producing object. These snakes feed primarily on warm-blooded prey such as birds and mammals, whose body heat is thus detected by the facial pit. Experiments reveal that even if blinded, a rattlesnake can accurately locate and strike a heat-producing object such as a balloon filled with warm water and having no smell. The pit provides the pit-viper with his most effective sense for locating prey and avoiding predators.

Our vipers have vertical pupils (similar to a cat's eye), broad heads, and thick bodies. In addition, all give birth to living young in the late summer or early fall. At birth the young snakes are quite capable of self defense. They are poisonous but have shorter fangs and less poison than the adults, but the poison is not dilute or weak. In the case of rattlers, newborn snakes do not (Continued on page 47)

Like time in its flight, wild wings seem ever moving, and in so doing give us renewed hope for future

Passage

IN MARCH, the prairie stretches between two seasons. Abandoned by winter, not yet explored by spring, these are the "ghost days;" the time in between.

By now the last configurations of snow have collapsed and sunk to the soil. The ice debris, rattling for days against the lee shores, sighs away at last and today seems gone from every pond.

This great melt is like a season itself. The ground whispers with seep and drip, and the sheet-water in miles of fields dances with the growing sun. The promise of spring —and the staggering production of the great plains summer to follow —are born in the cold mud and bread-dark clouds of these uncertain days.

Yesterday it began with the cries of a single kilideer; a lonely, nervous, shivering cry and pacing figure, fit for the wreckage of this landscape.

Today a scattering of divers rides the deepest pond —the distant twinkling shapes of bufflehead, scaup and goldeneye.

Tomorrow it will begin in earnest, those first faint wisps on the morning's southern horizon. . . .

If you are like me you will see them in your sleep and try to resurrect that vital sound. Like them you will be restless before dawn and up before the sun. . . .

It is a day for flying; clear and sharp. You are aware of the seconds passing, the coming sun, the silence of the northern continent...a waiting mind in a network of muddy roads.

Then through your binoculars you see them-the distance-silent strings and skeins, the shifting chevrons of determined, pumping wings. Then the first thin syllables, and soon the sharp air swims with the sounds of geese. This is the very voice of spring itself, unwinding at last the long dark bandages of winter from our eyes.

A seige of life. For days the waves sweep over and away, white and blue, swift with desire, huge as the generations. Like swirling snow they settle down to rest and feed, the choice fields collecting their endless gabble and march. A sudden quiet and they rise as one in a clap of wings, loud as a stadium roar.

One does not outlive this human need for bright wings in March and the winter broken; to see the land again glad with purpose and set to the pressing businesses of life.

Next year we will again return by these same precarious roads to drink this same swift celebration —to know once more the ancient gladness of this equinox. Having stood for a time beneath such passage, we cap binoculars and return to our concrete days, knowing that the spirit lives, the planet survives.

14 NEBRASKAIand MARCH 1976 15

As Bicentennial project, Jefferson County decided to restore a facility that served area pioneers

A COMEBACK OF A KILN

FAIRBURY, NEBRASKA sits almost upon the Oregon Trail where it crosses Jefferson County, not more than 10 miles north of the Kansas border.

The Oregon Trail moves diagonally toward the northwest, eventually meets the North Platte River, then heads for "Oregon Country".

As many as two million persons followed the trail from its inception (between 1800 and 1830). They traded, trapped, hunted and settled. Lieutenant Fremont, commissioned in Washington to find an official route to the Oregon country, stopped and camped by the trail in Jefferson County. (Kit Carson was his guide). Blacksmithing shops sprang up...general stores...homesteads ...stage companies. The trail witnessed the gold rush and the Overland mail. Wells Fargo wagons trundled their goods over its path. The area became an integral part of our American heritage.

Woral C. Smith purchased land near Fairbury in Jefferson County in about 1875. He built a home; more importantly he erected a lime kiln, and began the manufacture of quicklime for the area.

Quicklime is a most useful material. In a kiln built of native limestone, lined with brick, 17' square and 25' high, Smith burned the lime quarried from the local hills. He hauled stone by mule, up an earthen embankment, and dumped the stone through the top, down onto the great iron grates in its depths. He gathered oak from a local wood, lit a fire under the grates, and kept it burning for several days and nights. Water and carbon dioxide were driven from the stones, and they became the chalky powder called "quicklime", which was then stored in barrels and kept very dry. (Quicklime is highly

These lime combinations enabled settlers to build their homes and outbuildings, cement them with mortar and plaster and finish the insides, all with materials available near at hand.

Because the manufacture of quicklime was such an important element of pioneer life, because the lime-kiln in Fairbury and its adjacent house are nominally standing, and because the lime kiln is the best remaining example extant in Nebraska, the Jefferson County Historical Society has chosen to restore these sites as part of its Bicentennial observation.

The society engaged the firm of Wilson & Company, Engineers & Architects, of Salina, Kansas, to study the general condition of the lime kiln and the Smith house. That company feels that these sites can be restored, and so it has prepared a restoration and preservation plan for the society.

This study shows the lime kiln to be in repairable condition. Its original timbers and braces are gone, the stonework is cracked and the earthworks have eroded. The pit is filled with earth, stones and debris to a depth of several feet. Retaining walls need to be rebuilt, new wooden braces must be constructed and anchored. Stonework should be stabilized and sealed. All this, however, is feasible. Wilson suggests the addition of a safety grate over the kiln hole at the top, and a walk and step system to facilitate public viewing and to stabilize the earth slopes. The finished site would then be planted, both for practicality and beauty.

The general structure of the Smith House is reasonably sound. It has changed as the years have gone by, but can be restored to its original form. The floors and roof are badly deteriorated. There is evidence which shows a doorway has been replaced by a window. Another window has been bricked up at sometime, and used to create an outside cupboard protected by an added roof. On-site observations indicate that the house once had three brick chimneys, with the east one located outside the wall. This outside chimney is totally gone, and only an outline remains. Several layers of wallpaper cover the plastered walls. Examination reveals the original paper is something which could be duplicated without too much difficulty.

The Smith house and the lime kiln have been proposed as an historic district to be included in the National Register of Historic Places. They are the "Heritage 76" project of the Jefferson County Historical Society.

When restoration is complete, a marker describing the process of making quicklime will be added to the site with the hope that the project will contribute to the understanding of a period when our country was "building and growing".

16 NEBRASKAland MARCH 1976 17

Your Wildlife Lands The Northeast

LAND IS STATIC-unchanging. What we had in Nebraska yesterday, we have today and will have tomorrow. No more, no less. The use of land is ever changing. Make no mistake; land is the base of wildlife. What grows upon it, or what man places upon it, becomes the next determiner. This simple chronology is used to point out clearly that land-use dictates wildlife presence. Your Game and Parks Commission, and the staff, try in many ways to serve as advocates for wildlife —on the lands and waters of Nebraska.

The lands and waters that this agency owns or controls offer the most certain assurance that wildlife will receive first attention. This is the reason that we attempt to bring key tracts of land under ownership of the agency. In most any view to the future—be it budgets, plans, statement of needs, etc. —acquisition of land and water for wildlife purposes is always an important part of our considerations.

We can always wish that land-owners will save a place for wildlife. Many do, but many do not. Thus we must intercede where funds are provided, and willing sellers are found, and acquire wildlife lands. It is as certain as anything can be that once acquired, land and water areas will be held for wildlife and compatible public use into perpetuity. And that is a long, long time.

The annual wildlife crops may wax and wane. Managers will come and go. Generations of users will come and go. But the land will still be there. Somewhere in this rationale is the reason for our continual interest in acquiring wildlife lands, whether it be by gift, management agreement with other public entities, or by fee title purchase.

Then comes the trite but true statement of us all: "But what can one person do?" For every acre of wildlife land we purchase, one person, joined by others, buys a hunting or fishing license. Some of this money buys the land. An older couple says to us: "We want to give you this land to manage for wildlife. Nebraska has been good to us, and we wish to leave something of enduring value for the future." In other instances, an individual has said to us: "I want to sell this land to you because it was the wish of my late husband. I cannot afford to give it to you. We have always let the public fish and picnic here. May it always be that way."

Some of the best land and water acquisitions of this agency have come to our attention on a feebly written page, hardly legible, but carrying a clear message "would you be interested...?"

In a time when inflation is the "robber in the night", when generation gaps are apparent, when alienation and violence are daily fare, it may seem to many that we are crying in the wilderness on an issue of concern to no one. It behooves each of us concerned, to not let this be so.

This nation in general, and Nebraska in particular, will not be made more livable by dominant self interests. Some few will (and do) insist on selfless motives for public good. Quite often those who feel this motivation most strongly are least able to express it in words, but in deeds they excel I!

As you read the following pages relating to "Your Wildlife Lands- Northeast Nebraska", look for the timeless, durable qualities that were apparent to the writer. Read carefully the few quotations. Glance at the photographs, then study them, for they really begin where the narrative ends.

Harold Edwards, Chief, Resource Services 18 NEBRASKAIand

Wildlife lands are managed for specific purposes, which are wildlife production and public hunting, fishing, camping and other outdoor activities. They have a minimum of maintenance, and it is therefore important that visitors make as little impact as possible. Access is open year-round and there is some form of recreation to be enjoyed on them regardless of the season. Approximate locations of the wildlife lands in the northeast, and opportunities they offer, are shown below.

THE RIVER. For some 240 miles the Missouri River borders the northeast district of Nebraska. In winter it becomes a spectacle not enjoyed by most. Ice crashes on ice and comes to a grinding halt. Roaring ice chunks pile on each other. It is power!

Water flows constantly under, and seeks a more adequate outlet. It washes along the south bank, jams again, then breaks through on the north. Its passage is inevitable, just as the flow of life is inevitable if protected from man's ceaseless tampering, his stranglehold.

Winter has choked Northeast Nebraska. Ice lies impersonally on dead, brown grass. Oaks stretch barren and gnarled limbs to the cold, uncaring sky and devastating wind, their life force stopped down to defy the winter.

A nondescript log lies partially buried by sand, a casualty in the march of time. Its harsh past is written upon its charred and rotting carcass. Worms and beetles bore through its dead wood, breaking it down and rendering its limbs into dust. It will be organic matter to support the next generation, the coming cycle of life.

Yesterday a bleak sun shone, calling life to itself. Under a gray haze, small reddish swirls of plankton quietly appeared on the sandy riverbank. There was no signal of their arrival; no crashing of cymbals or choruses of angels. But their coming was inevitable just as was the escape of the river.

A red-tailed hawk, startled, bursts through the trees, leaving traces of rabbit furbehind. A confusion of songbirds calls across the meadows, awakened by warmer air under a heavv blanket of clouds. Deer leave sharp tracks along muddy flats, determined in their direction, following the trails of generations before them.

Coyotes pad across a hogback on the Missouri bluffs, also leaving footprints in the mud. It seems as though thousands of eyes peer at empty meadows and lonely trails. The interloper sees no animals in the forest, yet he feels their presence at all levels. Eyes seem to be watching from tree tops and branches —from behind trunks — and through grass blades and weed stems.

Scattered throughout Northeast Nebraska are parcels of land where logs decay and ice jams; where gnarled, lifeless stumps provide roots for clumps of new trees. There are only eight wildlife areas in the Northeast district administered by the Game and Parks Commission. They include Basswood Ridge, Wood Duck, Yellowbanks, Grove Lake, Whitetail, Beaver Bend, Bazile Creek and Sioux Strip. These sites comprise some 3,650 acres including 3,200 of land, 150 of water, and 300 of marsh. The areas also provide some 9 miles of river, stream and lake frontage.

Opportunities for the Game and Parks Commission to purchase good wildlife lands have been few. Managers are constantly on the lookout for those "waste" areas that are worthless (or almost so) for most agricultural and development purposes, but prized for wildlife.

Floodplain areas like Wood Duck make some of the very best wildlife areas for several reasons. To begin with, periodic flooding makes them marginal at best for farming, and disastrous for housing. Even minor recreational developments are too expensive to replace frequently. But wildlife lands, almost by definition, are devoid of major facilities. There is little there for a flood to harm.

Vegetation, and the wild birds and animals it supports, are the basis for a wildlife area. Flooding does very little permanent damage to wild vegetation.

Northeast Wildlife Lands represent almost every type of terrain to be found among the buckskin-colored hills of the region. There are bluff-lands, marshes, riverfront and floodplain. There are Platte River islands and artificial lakes. There are grasslands and small parcels of cropland to attract, feed and concentrate wildlife.

Rivers and streams are important to nearly every area. Bazile Creek borders the Niobrara, the Missouri, and Lewis and Clark Lake. Whitetail fronts on the shifting Platte and includes some islands. Wood Duck borders the Elkhorn, embracing its oxbows and marshes. Yellowbanks, too, fronts on the Elkhorn, its bluffs overlooking the deep floodplain. Grove Lake nestles on Verdigre Creek, and is a fishing water created by the Game and Parks Commission by damming the stream. Beaver Bend rests on Beaver Creek, and includes a tiny lake also resulting from damming.

The result of the varying topography from site to site and the different soils, is a wide range of plant communities from oak-linden forests to shortgrass prairie, to expanses of cattails on Missouri swamps.

The diversity of plant materials, in turn contributes to a variety of wildlife species. Coyotes and hawks, robins and muskrats, all find homes on one area or another. From deer to waterfowl to pheasant and quail, game species are abundant.

Hunters and hikers, fishermen and primitive campers are drawn to the Northeast. Space and subject matter for backpacking, nature study and photography are abundant. There are no sophisticated developments, no modern restrooms, no camping pads, no electrical hookups. There are sandy beaches and gnarled trees that house chattering squirrels. There are cattails and beaver lodges and muskrat houses.

A guide to the Northeast Wildlife Areas follows. You will find a description of recreation possibilities, management philosophies and some of the wildlife and plants that you will encounter as you explore the buckskin hills.

EARLY SUN sparkles on cool water that is gently rippled by an easy breeze, and touches the damp sheen of canary grass that lines the lake. A fisherman stands poised, line and body taut for a strike. He walked in when dawn was a mere promise of light. The quiet blue and green lake is a focal point of Grove Lake State Special Use Area near Royal.

Grove Lake itself was among the first fish and wildlife projects in Nebraska funded under the Dingell-Johnson Act. Both Dingell-Johnson and Pittman-Robertson programs provide 75 percent federal aid matching moneys for purchase, development and management of wildlife lands. Federal and state funds purchased land along Verdigre Creek, built the impoundment and provided for fish stocking and game management.

Anglers have their choice of the lake stocked with bass, crappie, bluegill and channel catfish, or of the stream with its flashing trout.

The Grove Trout Rearing Station, on the Special Use Area, stocks its surplus at season's end at Grove Lake.

In spring, visitors will find sharptailed grouse booming on grassy knolls, their mating call, on a still day, echoing a mile or more across the hills. Mallards dabble in the lake's floating watercress, making a salad of the greenery, their splashy slurping another life sign.

Poking around the creek bottom, hikers will find springs flowing from cracks in the bottoms of sandstone shelves. Rocks across the creek form tiny falls.

Soil on Grove Lake is gravelly, the result of weathering sandstone. The area's extensive tree planting for wildlife has been restricted to what will grow there, mostly red cedar on windblown hills —to hold soil. Near the creek is a heavy growth of bur oak, ash, sumac, gooseberry and dogwood.

Some of the Grove Lake lands have been purchased to control erosion. The first thing managers do to those lands, as on any area, is to stop all grazing. Wildlife land differs from surrounding territory by an obvious growth of taller grasses-clumps of switchgrass and scattered forbs. Private, grazed acres are smooth, as though mowed.

Prairie flowers bloom in spring. White-tailed jackrabbits and plains mice devour the tender greenery; the rose mallow's bright red blooms and the panicgrasses.

To add further to Grove's attractiveness to wildlife, conservation leases provide for small row-crop areas. Food plots of milo and corn bring pheasant, quail and deer along with songbirds and small mammals.

Back in the trees, opossums amble through a thick understory of shrubs, looking for decaying logs. They pick beetles and grubs from soft wood with gnarled-looking fingers. Squirrels scurry from tree to tree, chattering and chewing on tree buds and twigs.

A red fox steals through the bushes, a meadow vole or ground squirrel in his mind's eye. A spotted skunk and family waddle through a clearing in evening, maybe hoping to happen upon a quail's nest and a dinner of eggs.

American plum thickets line the hills and fencerows, their fragrance heavy in spring, their fruit heavy in fall. A confusion of songbirds, game birds and small mammals make their beds in the shrubbery, thier kitchens in the branches.

Tomorrow will bring no cattle to graze the mouse's trails through tall grass, no mowers to disturb ground nests. No bulldozers will tear out squirrel trees and shrubs, no farm implements will break the vegetation and erode the hillsides.

Tomorrow, like today, Grove Lake will be a refuge for wildlife where progress halts —except in nature's cycle of life and death, to death into life.

IT'S JUST KIND of a nifty little creek ...the whole area is valuable if for no other reason than that people can wander along the stream edge and see and enjoy."

Catfishermen might disagree about the value of Beaver Bend. An old power dam on the meandering stream has created a good fishing hole just below the structure.

Beaver Bend is a wooded area along a winding stream. There are only about 20 acres of cotton woodlined stream bed, but the lazy stream trickling along its lazy course, catching an occasional glint of sunlight, brings to mind barefoot boys with strings tied on brown toes. Perhaps a string and a safety pin are all that's necessary to enjoy Beaver Creek.

Or maybe the vision is one of cane pole and "merry whistled tune". A tobacco-spitting grasshopper is all that's needed to complete the vision.

A viceroy butterfly lights on a nearby violet...the rough trunk of a distinguished elm is a backrest. Dragonflies and tumblebugs are instant entertainment. A fresh blade of green grass is nourishment.

Tadpoles. There must be puddles nearby where tadpoles grow into frogs, and backwaters where the frogs go to call at night.

Deer, as well as boys, are comfortable on Beaver Creek. Songbirds and buzzing bees fill warm, afternoon air... now where do you suppose that hive is anyway? Hives mean honey, and boys like honey. . . .

TIME AND AGAIN man abandons his toys, and nature, aided by time, reclaims them.

Sioux Strip is a series of tiny land parcels that were part of a railroad. Trains no longer cross it, however, so pheasants are taking it over, setting up housekeeping where tall grasses cover the once-valuable railroad ties.

The right-of-way has been turned back to grass. Management consists primarily of fencing to prevent grazing. Grasses and forbs are being encouraged to take over as nesting and brooding cover.

DEW CLINGS to elderberries, making each cluster a shining mass of purple. A glistening drop falls on a leaf below, runs down the trough formed by its curl, drips on another leaf, runs off, and falls on a stem of panic grass.

Almost a mile of Platte River access, cottonwood timber, shrubs and oxbows comprise Whitetail. Deer use the woods, but the climax growth of timber must be thinned to let light in for the young, tender growth deer Iike to browse.

An archer wades through wet grass and sumac to a cottonwood tree stand, along a deer trail to the river. When the river is high, canoeists can launch at Whitetail for a quiet day on the water. The islands are a good place for stopping-off for a picnic lunch. Shifting sand builds and destroys islands from day to day.

Silent water mirrors shimmering trees in the oxbows where waterfowl dabble, muskrats build their impossible-looking mounds, and mink go fishing. A red-winged blackbird perches on a dusty goldenrod stalk, fluttering off only when approached too close by a fisherman, tramping to the oxbow for his dinner...

I CAN SIT here in this clearing with the petroglyphs behind me and the spring bubbling from the hill, and see Indians camped all around me. I smell their campfires and drying buffalo hides..."

A spring pours modestly from beneath a rock outcrop at the Missouri bluffs' base. Today it is silent in the tiny canyon, there is only wind in bluff-top oaks. Wind through trees and an occasional jay's scream awaken past sounds, though.

Maybe 100 years ago a prairie wolf stalked the bluffs, howling at evening. The wind would have sounded different; trees would have been few; the ridge would have been grassy; or maybe shrubs would have broken its sheer slopes. Man was just another predator then —more organized, more intellectual than any other, but still very dependent on the whims of abundance and scarcity.

Indians must have camped here, for they left their legends of the animals that captured their imagination, in rock outcrop, beside that of earth's history.

Men are still preoccupied with wild things and the miracle of their continued existence, and Basswood Ridge. is a place to imagine and contemplate that miracle amid rustling oaks, twittering wrens and browsing deer. Man again becomes a hunter.

Rock frowns on Missouri flood plain, seeming to brood on its youth. It was built of sediment, laid down at the bottom of an inland sea, compressed by pressure of water and many years. Later, glaciers ground across the dried-up lake floor, leaving behind boulders and stones, sand and silt.

Then wind carried a thick layer of loess to cover the wounds. A rivulet began to erode a path, and soon a brook was widening its bed. At last, a mighty river thundered through the valley it had carved, wandering back and forth through the centuries and across the miles-wide floodplain now 200 or 300 feet below bluffs that are broken by canyons and valleys cut by run-off.

Gradually, trees populated the shelter of the bluffs. Willows and cottonwoods were slowly replaced by oak and basswood, moving upstream to settle new territory already softened by tough, pioneering trees; the willowy, ash and cottonwoods.

While rough canyons are shelter for oaks, the rock ledges and caves above are home for turkey vultures. From a rocky perch, they survey their territory, looking for a meal that death provides . . . .

In the protection of bluff and ridge, oaks grow lush with a rich forest floor of prickly ash, raspberry, gooseberry and dogwood, draped with grape and Virginia creeper. In daytime, bats hang upside down from trees and shrubs, wrapped tightly in furry wingcloaks.

At trees' edge are sumac and elderberry where red-winged blackbird, robins and eastern bluebirds feed. Small meadows sport bunches of purple prairie clover, Missouri violets and wild strawberries for cottontail rabbits, Franklin ground squirrels and deer mice to savor.

On blufftop, where wind rakes the growth, trees are sparse, and those that survive are tough and twisted. Wind-whipped shrubs bear scars from deer's antler-polishing.

An occasional Kentucky coffee tree shows fat, black seed pods through the surrounding foliage, its rock-hard beans of little use to the animals around it.

Basswood Ridge offers hunters and hikers, backpackers and primitive campers all the isolation of the hard- bitten fur trapper who wandered the country before settlers. Rugged terrain at the back of the bluffs supports squirrels, rabbits and deer.

Little is done to manage Basswood —except by nature. There is little that is plastic, little that is artificial. It is a place where wild plants and animals remain wild; where man is an intruder.

IT WOULD BE hard to lose on Bazile Creek. Fluctuating water levels only change the complexion of the spot a little bit from year to year. . . ."

In wet years, ducks rest among the cattails, and hunters with breast waders can stalk acres of marsh. In dry years, the cattails provide cover for pheasants and quail, and nimrods with dogs have every opportunity for bagging birds.

The beauty of the water "cycle" is that the two types of hunting are not mutually exclusive. In wet years there are fewer pheasants, but they are still there. In dry years there are fewer ducks, but some are still to be found.

Almost every conceivable kind of flood plain plant-and-animal community can be found on Bazile Creek, in a rich, ever-changing intermixture that winds in parallel to the river. Thickets of low-growing willows combine with a few grape vines to provide food and home for gnawing beaver that leaves sharp stumps behind. Whitetailed deer browse on twigs and foliage of willows, while dozens of songbirds, in fall, feed on the fruits of the grapes.

In low areas, dead sandbar willows tangle with cottonwood and willow seedlings, and in the openings, shrubs and vines form an impenetrable mass.

Light penetrates the canopy of trees and shrubs where water drowns their roots. Here reed canary grass reaches for the sun, providing seeds for pheasant and quail. Thickets of dogwood, Indigo bush, prairie rose, and young cottonwoods and willows mingle with grass scattered with clumps of sunflowers, cordgrass and switchgrass.

Shallow pools border the grass. Here last season's dried-up cattails and bullrushes are a thick debris around this year's growth. Carcasses of dead trees, fallen leaves, and old cattails drop into the water, forming a slime of organic matter to nourish snails and clams, and micro-organisms that feed fish and insects. Redwinged blackbirds perch on cattail heads to herald spring. Herons and eagles feed on the minnows and snails of the marsh, while coots and rails paddle among the brush. Sandpipers wade along the shore, probing with long, curved beaks for insects. Clumps of cottonwoods break the cattails.

On the higher ground, half a mile or more from the river, mature cottonwoods provide heavy timber for deer cover. Mostly dead trees, the growth has been thinned to open the top and allow young growth for browse. Bobcats occasionally follow the river timber and deer.

A black crowned night heron sails the sunset, a black silhouette against orange sky and sparkling river. The Mighty Missouri sweeps by the mouth of Bazile Creek, swelled imperceptibly by its waters. Bazile Creek, in its turn, meanders through the floodplain, surrounding itself with a cloak of green shimmering trees and a furry mantle of cattails. . . .

There are quiet times on a wildlife land, for they are seldom crowded. In the spring, river bottoms and bluff lands pulse with new life —young cottontails make their first exploratory journeys from the nest. During the summer, life matures and by fall, asters mark end of growing season

SOMETIMES I just sit on a log and watch the snow fall...it seems to clear my perspective. There's just me and some old, rotten log, and the beginnings of snow. . . ."

A wooded riverbank seems locked in silence as late-season snow drifts through gathering darkness. A man sits in the gloaming, listening to the silence of falling snow....

Later in spring, city folks would call it silent, yet the woods fill to bursting with sound. There are the twitters and screams of multitudinous birds, the flutter of wings and their soft, preening sounds. Red-headed woodpeckers and flickers are jackhammers. As shadows cool grassy clearings, there are the distinct notes of bobwhite quail seeking each other across the meadows. A white-footed mouse squeaks out some message. There is the minute thud of a deer's hoof. A gentle breeze stirs across Wood Duck.

A dusty trail winds through the trees. It leads into clearings where grass is edged by a tangle of dogwood, plum, raspberry and gooseberry shrubs topped by cottonwood, bur oak, ash and elm.

The mournful call of doves mingles with those of quail, driftingfrom shrub and ground nests at meadow's edge, and, as darkness deepens, a great horned owl replaces the quail's call with his echoing hoot. A haphazard line of old fenceposts suddenly springs off, showing white flags—their deer-forms disguised by buckskin tree trunks and gathering dusk....

Beyond the clearing, deep on the area's south end, the road comes up- on a swampy marsh. Here arrowhead and cattails command their territories, each creating wilderness of its own growth. Duckweed floats on deeper water, choking the surface with a sheet of vegetation.

Here tiger salamanders and bullfrogs sit on logs and sticks and clumps of water weeds, waiting for a careless damsel fly. Great blue herons cruise overhead, while water snakes patrol the marsh, waiting for careless frogs.

In the deeper water of the north oxbow, carp and black bullhead provide fishing for people as well as raccoons. Minnows are prey to occasional ospreys and kingfishers. Indigo bush surrounds the water, its first growth in spring a yellow filagree against winter's buffs and grays.

Like all rivers, the Elkhorn has drawn wildlife to its shores for water. Men have followed. Dakota Indians picked up their money there. They knew the Elkhorn as "many snails river" for the mussel and snail shells they used as coin.

The Elkhorn was first mapped by James McKay, they say, and when Lewis and Clark left St. Louis in 1804, they were carrying McKay's map. Besides a cartographer, McKay should be recognized as a magnificent liar, according to some. It was he who recorded the presence of polar bears and pits of bubbling tar in the Sand Hills.

Managers have a better grasp now of what exists —too late for some species. The last buffalo was sighted on the Elkhorn many decades ago. Wildfowl and furbearers are no longer as abundant as in the time of market hunters and trading posts.

Today, man is learning to manage the wild game he once took for granted. Now managers plant alfalfa, clover, and western wheatgrass to replace brome that chokes out prairie variety. The growth provides nesting, brood-rearing cover and forage for deer. Through conservation leases, tenants plant row crops as food plots for pheasant, quail, deer. . . .

"I can tolerate all the garbage I pick up when I look around me and see I'm not alone here. I can track a deer through mud in spring. I can surprise a covey of quail, I can sense the presence of animals I never see...."

ONCE READ that there was a hermit of Yellowbanks. I don't know, though, whether he was a real person, or whether he ever did anything except be a hermit. I can think of worse places to be a hermit in. . . ."

Yellowbanks is a little-used area where deer concentrate. It's valuable because it's quiet and empty of human traffic —a hermit's paradise — even for a hermit-for-a-day.

Mushrooms populate Yellowbanks — and trees, trees planted in hieroglyphics that seem to signal air from the ground. Managers try to avoid rows and artificial right angles in their planting.

Bur oak cover the bluff sides, stretching their crowns from flood plain to the crests. Bare, yellow soil of the exposed bluffs gave the area its name.Bank swallows soar along the bluffs catching insects as they fly.

Catbirds' mews mingle with the calls of yellow-billed cuckoo and meadowlarks, echoing in the distance across nearby prairie pockets. Sawtooth sunflower, goldenrod, and aster mix with tall and short prairie grasses. Tiny prairie flowers shoot up sudden flower stalks, making pinpoints of color in the grass, and disappear in favor of another species. And so it goes throughout the growing season.

Tomorrow snow may fall; ice may again crash on itself, jamming midstream, freezing life within itself. . . .

Small but brazen, the screech owl will tackle animals larger than himself, but never will be lured out during daylight

NIGHT SAVAGE

SMALLEST OF THE eared owls, the screech owl is widely distributed in the United States. Of the 18 recognized subspecies, 3 —the Eastern, Aiken's and Nebraska races —reside in Nebraska. One or more races inhabit virtually every type of habitat in North America. As a result, it is probably the best known of our owls, having more common names than any other species. One of its local names, the quavering owl, would be a more appropriate name since this bird's mellow, quavering trill in no way resembles a screech.

When not hunting, the screech owl has a placid disposition and will often allow a close approach. If the bird feels threatened, however?-it may rely on a camouflage maneuver to escape detection. Squinting its telltale eyes, flattening its body feathers and raising its ear tufts, it will stretch upward, transforming its distinctive owl posture to a shape strongly resembling a branch stub. The disguise is further enhanced by the bird's mottled, bark-colored plumage. Although it will often tolerate close observation, the screech owl is not harmless; provoked birds have inflicted serious injury —from torn ears and punctured noses to eye loss.

Unlike some owls, the screech owl does not specialize on rodents. Its strong, large feet allow it to tackle surprisingly large prey. Although smaller than a robin, this audacious hunter will attack ducks, grouse, and even barnyard hens if sufficiently motivated by hunger. On the other hand, no other owl consumes such a volume of insects, making the screech the nocturnal equivalent of the sparrow hawk. Batlike, the maneuverable little owl will attack concentrations of flying insects attracted to mercury vapor lights.

In savagery, the screech owl is but a miniature version of the great horned owl. However, its ferocious nature sometimes outweighs its capabilities, often with disastrous results. It is known, for example, to attack even large constrictors such as the rat snake, a formidable opponent and a poor choice of prey. Also like the great horned owl, the screech owl is an adroit fisherman, taking crayfish, bullheads and amphibians along shore. It has been observed sitting patiently beside an ice hole, waiting to seize surfacing fish.

Screech owls often fall victim to larger owls, especially when rodents are scarce. By far the greatest enemy is the great horned owl since they usually share the same habitat. Like its smaller cousin, the great horned owl is also ruthlessly determined in pressing an attack, and once selected as a target, the screech owl has but a dim chance of escape. Its smaller size, faster wingbeat and greater maneuverability in dense cover give it a slight edge, but only a nearby tree cavity will keep the smaller owl from becoming just another of the day's countless energy transfers in the endless chain of life.

Marvelously adapted to their role as nocturnal predators, owls combine specialized eyes, acute hearing and silent flight to locate and ambush prey. Owls have the most versatile eyesight of all birds, functioning over a wide range of light levels. And, myths to the contrary, owls see quite well in bright light. The screech owl, in particular, seems to be fascinated by the day world and will often lean far out from its roost branch or tree cavity to watch the progress of a squirrel on the ground below. Yet no matter how many tempting morsels might present themselves during daylight hours, the screech owl remains strictly a nocturnal hunter, not wishing to expose itself to songbirds or hawks. Mercilessly mobbed by small birds when it is discovered, screech owls are often attacked by hawks when fleeing to another roost.

Superb hearing also helps owls to pinpoint prey. In scientific experiments, owls have captured prey in total darkness. Since no animal, not even owls, can see in the complete absence of light, hearing proves equal to eyesight in the capture of food.

But remarkable hearing and eyesight are not enough. If rodents —also highly sensitive to sound —are to be captured, a third adaptation is required: the ability to fly without making sound. Silent flight is accomplished by a unique feather adaptation. The leading edges of an owl's first flight feathers are finely notched, effectively silencing the characteristic rushing sound that air makes when disturbed by the beating of most birds' wings.

No wonder the woods were sometimes feared by our ancestors and thought to harbor demons. The mournful voice of the screech owl, the hollow, eerie notes of a distant great horned owl, or the insane screams and gobblings of the barred owl seemed not natural sounds but superhuman, suggesting spirit voices and souls in torment.

Long worshiped and feared, the owl continues to inspire uncertainty and dread. Even when its adaptations are understood, it somehow remains more suggestive than the sum of its parts. Who has not felt the instinctive shudder when surprised by the sudden swivelling of an owl's head and to be transfixed by a ghoulishly human stare? Who has met the moth-silent flight—eye-level in the dusk hush of deep timber—and not carried that vision through miles of sleep? After all, we are day creatures, diminished by the towering presence of darkness, and forever uneasy in a night world of swift, silent assassins.

MARCH 1976 35

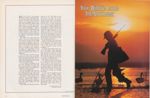

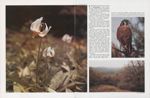

Last Breath of Winter

LIKE MOST MARCH storms, it was the child of low pressure over the mountains of the southwest. As the front pushed eastward, it drew moisture from the Gulf which became a driving rain in Nebraska's Panhandle. The wind shifted to the north as the storm moved eastward and the rain changed to drizzle. In the wake of the low pressure, the barometer began to rise and the drizzle turned to snow. The snow was relentless; pounding the countryside, sparing nothing. It hurled past the windows of isolated farmsteads in horizontal streaks. For farm families, Emerson's words, "a tumultuous privacy of storm", would have new meaning. Throughout the day it raged. By evening the wind had slackened but the snow had not thinned. It laid on the land like a great blanket of down. During the darkness the storm wearied. Morning spread across a land transformed. Woven farmyard fences were meshworks of steel and snow. The shoulder-high bluestem of yesterday was lost in the night's silent crush. Only plants exposed to the wind had escaped. The winter-browned landscape was molded in white.

From the time the storm began there were no birds in the air; each had found its own sheltered place. With morning's first light, man and animal emerged from their sanctuaries. Crows were the first about; raucous black violators of the virgin landscape. Thickets and weed beds stirred with juncos, tree sparrows and an occasional goldfinch. Downy woodpeckers and nuthatches coursed the trunks of dying elms. Coveys of bobwhite quail hurried over the crusted snow, gleaning wind-blown weed seeds, and pheasants broke free of their snow caves. For birds, a late-season storm can be the most fatal. By March they are at the weakest point in their annual cycle. The long winter has burned off fat reserves, food is in short supply and they must expose themselves more to find it. When a late-season blizzard covers the last weed patches, the birds must face days without body fat to carry them over. Fortunately, March snows disappear rapidly. Only hours after the storm, squirrel tracks link tree trunk to tree trunk. Along the edge of riverbottom woodlands, they finger out into cornfields. Chaff, and kernels nipped of their germ, litter the ground under the first convenient post encountered by the forager. A network of tracks tells of a flurry of activity that came after the snow stopped but before the sun could reveal their maker. The trails of deer mice emerge from nowhere, travel purposefully to nowhere and then return. A tangle of sparrow tracks tramples the snow around the bases of goldenrod, sunflower and false flax where they reaped a harvest of fallen seed. The tight-clustered prints of cottontails weave through the sandbar willows and the trail of a hunting fox records each pounce for an unseen vole. Within several days the traffic will have been so heavy as to defy interpretation. And, as the snow melts and refreezes, forming a rigid crust, the adventures of light-bodied animals will again become a mystery. Most migrating waterfowl seem undisturbed by winter's brief return. Canada and white-fronted geese huddle on a Platte River sandbar, tuck up a leg, slide their bill under a wing and wait for the storm to abate. Some birds are less wise, like the thousands of sandhill cranes that gather in mid-state. Their stormy flights all too often end as fatal encounters with powerlines and trees.

For deer and pronghorn, blizzards are probably little more than an inconvenience. Most had moved to the protection of riverbottoms, wooded escarpments or rugged terrain when the winter season began. Their trails in the snow tell of routine travels. Within weeks the land will be the gentle green of new foliage. Many of the small birds that bore the bitterness of Nebraska's blizzard will have moved on. Those that remain will reap the abundance of the season's first insect hatches. The browsers will feast on delicate new growth and predators will take their fill of swelling numbers of small mammals. The season's last test has passed and the protest of the unfit is a silent one.

MARCH 1976 41

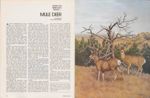

A Bird in the Hand . . . Needs a Bush

Habitat is key to pheasant stocking program undertaken by Game and Parks Commission and Landowners

A BASIC AXIOM of wildlife management deals with declining populations. It states that a species goes on the skids for one of two reasons: either insufficient numbers are born, or insufficient numbers survive to reproduce.

This principle is basic and simple, and its validity is quite obvious. All of the great wildlife managers and scholars have adopted it and paraphrased it, and all fledging students in wildlife management over the years have learned it early in their training.

Its application to Nebraska is evident to anyone who has been around for a few years. The declining species on just about everyone's mind is the ring-necked pheasant. In just 12 years, the number of birds harvested annually by hunters has dropped from 1,461,000 to 844,000 in 1974. And the key to the decline is no secret. It is Habitat.

Habitat figures into both parts of the equation. Without suitable nesting cover, few pheasants are hatched. And without escape cover, winter cover, food, roosting areas and other necessities of life, few of those young hatched will be around to reproduce the following year.

The Game and Parks Commission has long understood the habitat problem. For a few years, favorable federal farm programs helped by making land retirement attractive to farmers. But those programs are gone. Other efforts have also helped, such as the Acres For Wildlife Program. Though valuable, participation is small and habitat it provides is of limited scope. It has become apparent that the only way wildlife can hope to compete with valuable cash crops for space on the land is to instill widespread concern among landowners 42 NEBRASKAland and the general public. Then, hopefully, these people will be more willing to provide habitat.

To stimulate interest in wildlife, especially the pheasant, the seven-member board of Game and Parks Commissioners established a pheasant stocking program in 1975, and it was voted to expand it in 1976. The Commission will buy young chicks from game farms and give them to interested parties to raise until seven weeks old, with those receiving the birds agreeing to provide suitable habitat after the release.

Hopefully, the farmers, ranchers, farm youth groups, sportsmen, and others who invest the time, labor, feed and facilities to raise the young ringnecks, will develop a concern for the birds. They'll not want to turn pheasants loose where they have little chance of survival, so they might be inclined to provide some extra habitat.

And, landowners preparing to raise some pheasant chicks in late spring will likely be more aware of pheasants and other wildlife, and take their habitat needs into consideration in most farming operations.

In adopting the stocking plan, the Commissioners emphasized that its primary function would be to provide habitat by offering the birds as an incentive to landowners. They recognized that, without an improvement in habitat, the whole effort would go for naught, as have so many other stocking programs in other states.

Experience has taught wildlife managers that stocking, alone, will not bring back nor bolster a declining population. The decline is simply a symptom of some serious malady, usually a habitat deficiency, and stocking without improving habitat is attempting to treat the symptom rather than getting at its cause.

You might also consider the Commission's stocking program as a challenge to landowners. In the axiom of declining populations, lack of production is one cause of the problem. By providing birds through the stocking program, lack of production is eliminated as a factor. It then falls to the operator of the land to remedy the second cause of decline by providing the habitat to enable the birds to both survive until the next year and to nest successfully.

If this takes place on a large enough scale, sufficient pheasant habitat will be returned to the Nebraska landscape, and the stocking program will have accomplished its goal.

The 1975 stocking program got a late start and thus operated on a rather small scale. Some 12,250 chicks were distributed to participants. Of these birds, about 40 percent were lost to sickness, cannibalism, predators or accidents before they were released.

An encouraging note was the interest among farm youth. More than half of the total participants were members of 4-H or Future Farmers of America.

The stocking program will continue into 1976, but on a larger scale than last year. At their December meeting, the Game and Parks Commissioners decided that farmers, ranchers, sportsmen's clubs, 4-H and FFA groups, and natural resources districts would be eligible. And, all participants will be given as many birds as they feel they can handle.

In addition to providing the birds, the Commission will also give participants training necessary to successfully raise the young ringnecks. The volunteers will be expected to raise the chicks until they are seven weeks old, at which time a conservation officer will band and release them in suitable habitat near where they were raised.

Deadline for enrollment in the program is April 1. An application blank is found on page 47 of this issue.

If direct involvement with pheasant stocking creates sufficient concern and interest, perhaps those who operate the land will reverse the habitat destruction that has so decimated pheasant numbers. If we can return adequate habitat to the birds with this program, the ringnecks' decline will have been halted. For, with adequate habitat, this hardy and prolific bird will be able to maintain his numbers on his own.

MARCH 1976 43

PANHANDLE TROUT

(Continued from page 9)up to five or six. Often, a fisherman can drift his bait right under their noses all day long without results. Other times, the eighth or tenth attempt will bring a strike and sometimes a feisty rainbow will nail the bait at first sight.

In the fall, the best fishing is found in Tub Springs, Red Willow and Nine Mile creeks, but in the spring, Pumpkin Creek offers action to rival the other three. Besides these, a host of other streams also offer action. These include Sheep, Dry Sheep, Spotted Tail, Dry Spotted Tail, Stuckenhole and Winters creeks.

With the exception of about 1 1/2 miles of stream on Nine Mile Creek, all of the trout streams are on private property, and permission of the landowner is required. Most often, landowners are very reasonable with courteous fishermen who seek access to the streams.

One important regulation applies exclusively to fishermen on these streams, and that is a ban on the possession of any kind of seine or net, including a landing net. It seems that, in past years, the flash of the big silver-and-pink trout caused a few fishermen to lose control of their sportsmanship and go after rainbows by foul means when fair ones failed. Because of this the regulation was enacted, making it necessary for fishermen to beach, "tail" or otherwise land their catches without a net.

This means that fishermen wanting to release a small fish or turn a trophy loose to fight another day will have to be extra careful in the way they handle the trout. The less a fish is handled, the better its chances of survival.

It is best to play a fish until it is completely tired out before bringing it in. A subdued fish will struggle less and allow gentle handling. Ideally, you should grasp the hook with pliers while the fish is still in shallow water and shake it free without handling it. If you must pick up the fish, be careful not to squeeze it amidships, because even a little pressure on its innards could cause fatal injury.

Handling a fish with wet hands decreases the chances of breaking its protective coat of slime and opening the way to fungus or other infections, but this could also mean a fisherman might have to squeeze harder to hold on. It's a toss-up as to which is preferable-wet hands or dry.

One thing is certain. If you grab a fish under its gill covers you'd just as well keep it, because it will not survive such treatment.

Actually, chances are slim that a trout will survive past its first spawning run. A few fish, tagged during one spawning run, have been found returning a second time.

44 NEBRASKAland

A rainbow making its third spawning season is almost unheard of.

The life cycle of these fish is a rather interesting one. Each year, trout from Lake McConaughy head up the North Platte River and into the stream in which they were hatched. They lay their eggs, then return to Lake McConaughy. The eggs spend about 4 weeks in the gravel bottom of the stream before they hatch, and the tiny fry spend several more weeks there until they venture out in search of food.

During this entire time, clean, silt-free water percolating through the gravel is vital to keep the eggs and fry supplied with oxygen.

Eventually, the young trout move to vegetation along the banks of the stream, where they find both protection and food. They spend a year in the stream before migrating down to Lake McConaughy as 10-inchers. They pass another two or three years in Big Mac, packing on pounds and inches, before reaching maturity and heading upstream to spawn.

According to biologists, the eggs of spring-run fish have much less chance of making it than do those of fall run fish. For one thing, spring rains and irrigation runoff muddy the water and suffocate many eggs and fry. Also, muddy water makes it hard for the fish to see their food, and high water in the spring denies them resting places in shoreline vegetation.

In addition, fry hatched in spring must compete for food and hiding places with those hatched the previous fall —bigger, stronger fish with several months' head start. The biologists therefore say that the spring run is of considerable importance for fishing opportunity, but the fall run is much more important as far as trout reproduction is concerned.

On occasion, there is some objection voiced to the taking of these fish while they are spawning. These spawners represent the total natural reproduction for Lake McConaughy and the North Platte Valley. However, Game and Parks Commission fisheries biologists have determined that the amount of silt-free, gravel stream bottom, and clean, cold water are the limiting factors on trout reproduction, not the relatively small harvest by stream fishermen. Anyone interested in increasing trout numbers, either in the spawning runs or at Lake McConaughy, should work for stream bank stabilization and other practices that would improve spawning habitat in these feeder streams.

VENOMOUS SNAKES

(Continued from page 13)have a rattle. The tip of the tail has a horny knob; the pre-button. The baby snake sheds* its iskin within two weeks of birth and acquires a button, but this button does not produce a rattle. Every six weeks or so throughout the growing season, the snake sheds its skin. With each shedding, a ring is added. When the tail is shaken, the rings bang against one another, producing the "buzz" or rattle. The frequency of shedding is related to growth, not age; thus a snake with a button and five rings has shed six times and may not yet be three years old. The horny rings are fragile and break off as a normal course of events. One rarely finds a wild snake with more than 7 to 10 rings on the rattle.

Copperheads shake their tails when disturbed, as do many harmless snakes. Many persons have experienced considerable fright when discovering an angry bullsnake, fox snake, or rat snake, and the snake vibrates its tail in dead leaves, producing a loud rattle. Bullsnakes are also able to produce a rattle-like noise by forcing air out of their lungs. On more than one occasion, the noise has made me stop and take more careful note of the retreating snake. The noises produced by these harmless snakes probably account for many of the instances of near-discovery of an unseen "rattler" because, upon hearing the sound, most people assume it is a rattler and beat a hasty retreat. To investigate such a noise in many parts of Nebraska is to risk a face-to-face confrontation with an angry snake. If it is harmless, the adrenalin and fear will soon dissipate, but if it is indeed a rattlesnake, you've gotten much too close to an animal well equipped at self defense, and have placed yourself in unnecessary danger.

Newly born copperheads are not so cryptically colored as are their parents. Adult copperheads are nearly invisible against a background of dead leaves, but the newborn and juvenile have bright greenish-yellow tail tips. The small snake wiggles its tail to entice small birds and mammals close enough to be captured.

Although copperheads and massasaugas frequently eat frogs, lizards and large insects, the diets of all four of Nebraska's vipers are composed chiefly of rodents. Smaller snakes eat mice and shrews, and larger snakes take mice, rats, ground squirrels, small prairie dogs, gophers and small rabbits. Birds form a smaller element of the diet, probably because they are less likely to encounter these heavy-bodied snakes. Ground-nesting birds, especially the smaller kinds, have been found in the stomachs of these snakes.

Depending on local weather, the four poisonous snakes emerge from overwintering sites in April or May. In the southeast, the overwintering sites are usually areas of rock outcroppings where the snakes may crawl a considerable distance underground and avoid frost. In the western part of the state, rodent burrows, especially prairie dog towns, and rock outcroppings provide the necessary sites.

Following the spring emergence, the snakes remain in the vicinity of the denning site for protection against cold spring nights. During the day, they bask in the sun. Also, following emergence, the snakes mate and disperse from the denning site. While temperatures are moderate, the snakes are active by day. By mid-summer, they shift their activity cycles and become more nocturnal, rrfoving about in the evening and/or morning. As temperatures cool with the approach of autumn, the activity cycle again shifts to daytime and the snakes begin to gather near the denning sites. The young are born near the overwintering sites. Thus, in the fall, and to a lesser extent in the spring, one might encounter a number of young with one or more adults. It is unlikely that the young are remaining with the parent for protection or some other altruistic purpose, but rather that they remain together because they have arrived at the same overwintering site. In most northern states, including Nebraska, suitable denning sites are not uniformly distributed and we see an aggregation of snakes in the fall.

Our shorter and cooler growing season,

compared to that in southern states, probably accounts for the biennial reproduction of most poisonous snakes at this latitude. During the winter, little or no development of the embryos occurs, and

two years of development time is generally required. Adult females generally

mate in their third year or late in their second. In general, larger females give birth

to larger litters. The copperhead gives

birth to 2 to 11 young (usually 5 or 6)

measuring 7 to 8 inches long at birth. The

MARCH 1976 47

massasauga gives birth to 5 to 15 young

(average 8) 8 to 91/2 inches long. The timber rattlers have 5 to 17 young (average 9)

of 8 to 13 inches in length. Prairie rattlers produce the largest litters; some from

4 to 21 are known, but most contain 8 to

15 young (average 11-12); and newborn

young are 8 to 12 inches long.

massasauga gives birth to 5 to 15 young

(average 8) 8 to 91/2 inches long. The timber rattlers have 5 to 17 young (average 9)

of 8 to 13 inches in length. Prairie rattlers produce the largest litters; some from

4 to 21 are known, but most contain 8 to

15 young (average 11-12); and newborn

young are 8 to 12 inches long.

Males are generally larger than females, and the largest individuals of each species are males. Our copperheads are 22 to 36 inches long as adults with an average of 29 inches. The smaller massasaugas are 18 to 29 inches long and average 26-27 inches. Prairie rattlers are 25 to 45 inches long as adults but examples larger than 40 inches are rare. Adult timber rattlers are 30 to 55 inches long. The largest specimen I have seen from Nebraska was a male 55 inches long. In other parts of the United States, timber rattlers reach at least 72 inches.

Many people believe that cottonmouth mocassins, Agkistrodon piscivorous, occur in Nebraska. This heavy-bodied, relatively large viper is a close relative of the copperhead, with a decidedly marked preference for aquatic habitats. The snake that I think accounts for all supposed sightings of the mocassin in Nebraska is the northern or common watersnake, Natrix sipedon. This pugnacious snake is harmless in that it is not poisonous, but is still capable of inflicting a nasty bite. When swimming, watersnakes are readily distinguished from mocassins because the body of the watersnake does not float on top of the water but glides beneath the surface. A swimming moccasin rides upon the water as though inflated by air. Also, watersnakes do not have the mocassin's habit of throwing back their head and opening their mouth wide, exposing the white linings of the mouth. When disturbed, our watersnakes quickly seek the security of water and dive beneath debris.

If bitten by a poisonous snake, you must seek medical care. A few first-aid rules should be followed even though medical help is readily available. A ligature (a shoe lace will suffice) should be tied a few to several inches above the bite, between the bite and the heart. The ligature must be tight enough to retard blood flow; but too tight a ligature will prevent blood flow and cause other problems. The ligature should be loosened 1 minute in every 10 or 15. The venom will cause local swelling, hemorrhaging and pain. Shallow cuts should be made in the area of the bite and around the bite to get the venom out. Suction, either using cups in snakebite kits or your mouth, should be applied to the cuts to remove venom and blood. Suction cannot be overdone. The hemorrhaging in the vicinity of the bite will slow the spread of venom, and every effort should be made to remove as much venom as possible. The victim should remain as calm as possible under the circumstances; at least avoid exertion. Alcohol provides no remedy and may aggravate the problem. Send someone to get medical aid; if alone, move slowly to avoid speeding up circulation, but get to someone who can get you to a physician or hospital. Although a serious injury, snakebite does not result in instant or sudden death except under most unusual circumstances. A healthy adult without treatment may survive a bite of a small snake, or live for several hours following the bite of a large snake.