Portrait of the Plains A NEBRASKAland Gallery

Portrait of the Plains

A NEBRASKAland Gallery NEBRASKAland VOL. 54 NO. 1 JANUARY 1976 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Fifty cents per copy. Subscription rates $5 for one year, $9 for two years. Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1976. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska.

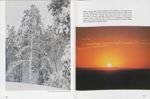

"Oh beautiful for spacious skies for amber waves of grain . . ." These few words seem to capture much of the richness that is Nebraska. In this Bicentennial year, we join all Americans in reflecting upon our proud heritage and saluting the nation's first 200 years. Nebraskans are a proud and independent people, much like our founding fathers. With that kind of heritage to draw on, Nebraska and the nation can look to the next 200 years with confidence and high expectations.

J. James Exon, GovernorThe Nebraska Game and Parks Commission proudly salutes the nation's 200th anniversary with this special issue of NEBRASKAland Magazine. This pictorial view of Nebraska in general and conservation in particular seemed a most appropriate way to observe our country's 200th birthday. We hope that you will find this kaleidoscope of Nebraska's intriguing past and present a stimulating prelude to the state's and nation's rich and varied future.

NEBRASKA GAME AND PARKS COMMISSION Willard R. Barbee, Director William I. Bailey, Assistant Director Dale R. Bree, Assistant Director lack D. Obbink, Chairman Arthur D. Brown, Vice Chairman Kenneth W. Zimmerman, 2nd Vice Chairman Don O. Bridge William G. Lindeken Gerald R. Campbell H. B. Kuntzelman Contents CHAPTER I, PLATTE VALLEY 4 A major artery since early times, river system has served wildlife and people CHAPTER II, SAND HILLS 26 Once a no-man's land and now lush cattle country, grassy dunes are unique in America CHAPTER III, FARMLANDS 60 Where prairie grasses formerly reigned, corn and wheat and irrigation are modern royalty CHAPTER IV, MISSOURI VALLEY 82 The cradle of westward expansion, rich soil and beautiful bluffs fostered man's growth CHAPTER V, PANHANDLE 112 From expansive wheat fields to rugged bluffs, western Nebraska has long been magnet of life

Platte Valley

For countless centuries, the Platte River Valley has

been a gathering place for migrants. Wild birds found

it an inviting resting place during their twice-a-year,

north-south movements between summer and wintering

grounds, and nomadic early man used the river for its

ability to attract and support game animals. Then, when

white settlement came about, the river became important

in another way, as it provided a natural valley which

proved to be the best route for east-west travel. All

across Nebraska, the Platte River and its western

4

5

sub-rivers, the North and South forks, still are important to

migrating and resident wildlife, and to man. After

initial settlement, subsequent agricultural techniques became more sophisticated, and the need for additional

water for irrigation put extra demands upon the river

system. During the westward migration of settlers in the

last century, the Platte River grew in fame. Along much

of its length, wagons, horses and people used it for direction and sustenance, and made many references to its

remarkable breadth and shallowness. While traversing

the trail beside it, the going was relatively easy with

only an occasional rough place, such as the precipitous

Windlass Hill at Ash Hollow. As formerly, the river

sub-rivers, the North and South forks, still are important to

migrating and resident wildlife, and to man. After

initial settlement, subsequent agricultural techniques became more sophisticated, and the need for additional

water for irrigation put extra demands upon the river

system. During the westward migration of settlers in the

last century, the Platte River grew in fame. Along much

of its length, wagons, horses and people used it for direction and sustenance, and made many references to its

remarkable breadth and shallowness. While traversing

the trail beside it, the going was relatively easy with

only an occasional rough place, such as the precipitous

Windlass Hill at Ash Hollow. As formerly, the river

continued to attract game and people, with farms developing along its banks. In many regions, the river held the only timber available for buildings, and its water was clean and dependable.

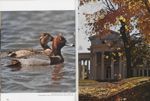

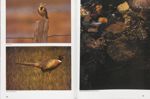

In more recent times, recreation has grown in importance, and the river again was a natural attraction. Now, however, access is more limited due to private ownership, and usage of the river and its environs is very heavy in areas. This has caused concern, and acquisition of more public land may become necessary. Use of the river by wild birds is still among the most spectacular in both spring and fall, with the sandhill crane drawing a major audience in March. The river across the

9

central part of the state is the primary staging area for the noisy, colorful birds, and it's considered a critical factor in their well-being. Heavy use of the river during

the cranes' stay would be detrimental, as it would in heronries farther west. There, visiting herons have relatively undisturbed sites for nesting, and an ample fish

supply. Eagles, hawks and owls also find the wooded riverbanks and adjoining croplands a fruitful hunting ground for much of the year. Travelers on Interstate 80 are treated to the

scenic wonders of the ageless river, but many probably do not realize the significance the river had historically, both to the Plains Indian and to the nation's westward expansion.

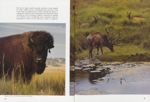

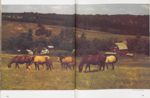

Sand Hills

It must have been with considerable trepidation that man took his first venture into Nebraska's vast Sand Hills, and the journey probably became more frightening with each step. Before the automobile, even before the horse, travel in the 20,000 plus square miles of sand dunes had to represent a suicidal feat. Navigation had to be totally dependent upon celestial bodies, as landmarks were virtually absent. According to legend, the hills were avoided as a wasteland, where no one could survive. Yet, inroads were gradually made as settlers encroached upon

the fringes of the hills, but even they fell victim to the terrain, and many perished when they became hope- lessly disoriented amid the sameness. Even the survival of buffalo must have been credited to magical powers, as it was not until a rancher had cows wander off into the dunes that the area's potential was partly realized. Giving the cattle up for lost, he was astounded to have

them return in the spring fat and healthy. Exploration of the region gained momentum, and the presence of water and grass led to the eventual establishment of hundreds of ranches and expansive cattle empires. The sheer vastness made improved mobility necessary for settlement, as even horses made a trek across the Sand Hills a matter of many days. Today, it is difficult to appreciate hardships

endured by those early settlers. Towns were far apart and money scarce, and it was more difficult to be self-sufficient than in other areas. The soil offered less potential for gardening and crops, as it was primarily hay country. Thus, it evolved as cattle country, and ranching is the primary industry even now. Some natural lakes, and interlacing streams and available groundwater

wells provided ample water for livestock. The primary danger then and now was overgrazing, as the fragility of the dunes is obvious. If the ground cover is removed, the sand blows away leaving "blowouts" which increase in size. Special precautions must be made around any obstacle that tends to catch the wind, so that old tires are laid around utility poles to keep them from being

uprooted by departing sand. Once a blowout starts, it must be protected by hay or other cover until grass can start again. During dry years before the advent of man, the herds of buffalo must have raised havoc with the hills and led to considerable wind erosion, but the surface has the capability of healing itself if left to its own

34

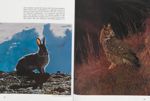

devices. Grass fires must also have occurred even before man's carelessness, as lightning still accounts for a number of fires annually. But again, the grasses merely waited for spring rains to bring them back to life as surface protection. And, even before domestic cattle, the area was grazed and foraged, for wildlife knew what the Sand Hills had to offer. In areas where groundwater

was so high that it covered the surface, waterfowl and shore birds made their homes. Myriad creatures from the insect clan to bison, elk and bear found adequate food and shelter. Antelope preferred its openness, and deer and coyotes thrived. Kangeroo rats, which are evidenced by their millions upon millions of small mounds amid

the sea of large, sandy mounds, provide a food supply for many larger species, including hawks and owls. The food chain as experienced in nature among the dunes is a generally balanced one interrupted only during unusual conditions such as extreme weather conditions or spread of a disease. Even considering man's presence and his utilization of much of the resources, there is a balance

of sorts. The cattle replaced the bison, but many other species carry on without much disruption in their life schedules. Pronghorn antelope prefer foods pretty much disregarded by cattle, and birds are greatly affected only if their nesting and rearing territories are degraded. As the Sand Hills are unique in North America, being

most similar to a portion of the Sahara Desert in North Africa, it is perhaps odd that wildlife is able to adapt to it without more difficulty. Yet, even migrants have no apparent problems, and in fact seem to prefer it to other areas at their disposal. The comparative isolation must certainly be a factor, but the presence of life requirements is perhaps enough. Water, which is the key to all survival, seems totally absent in large areas, yet abundant in others. Although the layer of sand is deeper in the southern portions of

the hills, groundwater never seems far away. The sand is amazingly porous, allowing rainwater to trickle through and replenish the groundwater. It, in turn, drains away via the few streams that exit from the region. Unlike many small rivers, the Dismal, Calamus and Loup rivers do not fluctuate much throughout the year. Where there are no such drains, the groundwater in other areas may be in evidence in lakes where it simply is exposed above the surface rather than hidden beneath. Although never deep, these lakes are likewise quite stable during most of the year, seemingly unaffected by evaporation or the vagaries of rainclouds.

Human life is also different in the Sand Hills. A lifestyle somehow vaguely reminiscent of New England and yet not unlike the Southwest, has a different pulse and tenor. The people are not unsocial, but they know the worth of that increasingly rare commodity, privacy. All seasons may bring them problems, but they are natural ones, and the solutions are reasonable.

59

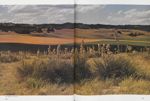

Farmlands

Since that day when the first knowledgeable farmer saw the tall grasses of what is now Nebraska, part of the state's destiny was agricultural. Long before modern equipment and formulated soil additives, the Omaha Indians were producing corn that exceeded 150 bushels to the acre. The soils were rich, and most years growing conditions enabled ample crops, even with lesser strains of seed. In the generations and centuries since, with mechanized irrigation, special seed, modern technology and ingenious implements, a food-producing capacity has evolved that staggers a statistician. During peak harvest time, rail cars

60

and elevators are hard pressed to handle even a part cf the bounty, with much being stored on the farm for later sa e or Hvestock feeding. Soil types vary across the state, yet all Z a few isolated regions are suitable for some crop production Even areas formerly considered marg.nal have been turned into oroductiveness by the introduction of water. Each year, appro mate 1 600 new wells bring another 200,000 acres under Studies indicate the state has an incred.ble supply underground water; sufficient to last 600 years without any

recharging, yet more than twice as much water is added than is used each year. While not all ground-water is available where needed, and not all is at a depth where tapping it is practical, it remains as a veritable buried treasure. Irrigation seems to have followed a sequence of utilizing surface water with dams and ditches where feasible, to pumping from wells into field laterals or pipes, to the latest method of pressure spraying with pivot systems for sprinkling water on top of the plants. These gangling creations are expensive and efficient, but doubtless will be replaced by an even more magnificent device.

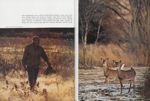

Where crops flourish, so also does wildlife, as the richer the land, the more life requirements can be filled. There is a more diverse and more extensive array of wildlife in agricultural areas, therefore, compared to areas of limited habitat type. With the

71

increase of productivity, however, there is more competition between man and wildlife, and animals are suffering from the decrease in habitat available to them. A growing world population requires more food, and projections indicate a dim future for many species. Quality of life diminishes with overcrowding,

73

and a balance cannot be found until the sides equalize. Many factors have contributed to a gradual increase in the size of farms and fewer farmers until only 16 percent of Nebraska's population, in a primarily agricultural state, now resides on farms. All wildlife resides on the land, and while their numbers have not declined to quite that extent, they are feeling an increasing squeeze. As

their adaptability varies, so does their population. It can only be hoped that the present trend can be slowed, as there must be a point where mankind is able to share this domain with lesser creatures.

As the critical need for conservation becomes more evident to everyone, perhaps that turning point can be recognized before it creates hardships on man and beast.

Missouri Valley

Heading west by wagon train, the Missouri River was a formidable hurdle to cross, yet it signalled only the beginning of a long, arduous trip. "Across the wide

Missouri has a romantic, colorful mood about it, but actually crossing that often deep and roiling, and always unpredictable and dangerous, river was one episode of the journey that most pioneers would gladly have bypassed. And, to reach the mountains before winter made them impassable, the river usually had to be forded in spring, when the

thawing snows and spring rains swelled its normal volume. Many years have passed, and changes have taken place even on the "Mighty Mo". With dams on its upper reaches, the big river is relatively harmless now. For most of its length along Nebraska, the Missouri has been channelized for barge traffic. Pilings have been installed to

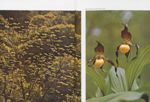

protect the shoreline from erosion, and numerous bridges minimize the river as an obstacle. One thing that hasn't changed is eastern Nebraska's agricultural richness; a richness that pulls down roots and nourishes an amazing array of vegetation. For ages the river cut away at the plains, removing a jagged slice of what had been deposited for eons. At the same time, it established an environment of temperate moistness that encouraged the spread of a unique formation of plants and animals. Some tree species became entrenched to become the westernmost outposts of the eastern hardwood forest.

With the forest and its canopy of leaves to filter out the warming sun, needed to sustain prairie grasses, came shade-tolerant shrubs to further distinguish the area. Plant and animal species gradually adapted, giving the river bluffs an even more singular character. Insects

and reptiles and birds and animals established their new community and thrived. Plant species sorted themselves according to their water and light requirements, ranging from the floodplain varieties nearest the river to hickory and oak atop the bluffs. There is a profusion of lush growth, including some found elsewhere in the state, but often, types found only in the protection of the river's influence-wild berries and paw paws and basswoods, hickory nuts and red oaks. The bluffs and rolling hills to the west of the Missouri somehow protect the less hardy species, and thus they became the northwest terminus. Birds, too, have extended their range only because conditions invite them. Thus the whip-poor-will, pileated woodpecker and woodcock adorn the forest, while below might be found the timber rattlesnake

97

and copperhead-also in their northernmost territory. And, just as the river invited plants and birds to journey from their normal habitat, so it did man. On foot, horseback, wagon and boat he came, seeking fame, fortune or freedom. Many passed through, other stayed, to break the soil's surface and seek the richness beneath. Success came

to those also willing to adapt and accept the river country on its terms. The country helped shape the lives of those residing there, but offered rewards. It came to be known as the land of gracious living because the pace was easier than on the plains. Yet, few farmers are more industrious, because they see the fruits of their labor. And, when the land is good, life upon it is also good.

Panhandle

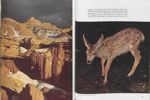

Because of its location, there may very well be no more diverse-terrain area anywhere to compare to Nebraska's Panhandle. In character, it ranges from high plateaus forming towering monuments over level plains, to scarred badlands undercut by centuries of erosion, to the huge,

rugged escarpments and canyons cloaked in dark pines. Northern and southern portions of the Panhandle are the remnants of once flat, high plains which were then worn into irregular, even weird form by the forces of water and wind. In the center, the surface remains much as it

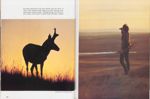

was, but the seemingly endless fields of wheat now grown there will suddenly give way to the beginning of the Pine Ridge in the north, with its scenic buttes, valleys and meadows. To the south, steep, flat-topped mesas overlook grasslands profusely dotted with oil derricks and grazing cattle. All is wildlife country, with the state's highest populations of deer, antelope, turkey

and perhaps waterfowl. It is ranching country, as well as farming yet scenery and recreation are among its strong points The Pine Ridge is the state's admitted scenic center Also it and surrounding area are a hunting mecca because of the wildlife. Restoration projects aimed at replacing species decimated by settlers turned out well, most notably the turkey and antelope releases. Turkeys

in particular mushroomed in population amid the hills and valleys covered with ponderosa pine. Antelope found the neighboring landscape ideal, and deer accepted both regions for their use so that now mule and white-tailed deer are numerous. They dwell in pockets on the range adjoining the Ridge, and inhabit the canyons and cliffs which account for the splendor of the region. Wildlife

has been attracted to the area almost from the dawn of time, with creatures both large and small playing many spectacular dramas nearby. Strange beings, from diminutive camels and horses to great beasts perhaps capable

of eating a horse at a sitting, still are found. Only now, they are in a place of honor at Agate Fossil Beds, a National Historic Site in the northwest corner of the state. Specimens taken from the site are displayed at many museums around the world. But, this is just another^ of many facets of western Nebraska. History continued to pile up in the area, as the North Platte Valley became an important thoroughfare for migrants bound to meet their destinies farther

west. Landmarks for their journey were abundant along part of the way, with Chimney Rock and other spectacular formations posted along the fringes of the valley heralding the end of one challenging increment of the trip and the beginning of another. Many legends of the area have turned up in Indian history as well, such as Lover's Leap, involving a maiden and a warrior from another village. Another centered around a formation, possibly Jail House Rock, after the

confrontation of two rival tribes. One group was driven up the only trail to the top of the rock, then were held prisoners. After several days, a daring escape was made down the sheer side of the formation after tying every available rope together, thus leaving the captors alone

in their vigil. As time progressed, subtle changes occurred in the Panhandle Irrigation developed along the North Platte River and the discovery of oil to the south made an impact economically. It is stilf primarily an agricultural region, however with sugar beets and wheat of greatest importance. Still, most of the recognition of

the region seems to stem from its natural resources that please the eye, and for the recreation that it offers. Much of Nebraska's fishing potential is there, including trout waters which feed into the North Platte River, and northwest streams. Lake McConaughy, on the eastern edge

of the Panhandle, is the state's largest body of water at 35,000 surface acres, and is the recognized leader in fish production and number of species. Nestled in the Pine Ridge are other trout streams, as well as two major state parks-Chadron and Fort Robinson-plus several

large scenic public areas. Included in Fort Robinson is a cattle ranch of over 10 000 acres, and it adjoins Forest Service land of 10,000 acres. The fort served from frontier times into World War II. North just a few miles is an eerie, geologic arena featuring some of nature's most ruthless forces Toadstool Park. While it is a wasteland, the Ridge is greenery, yet both resulted from the same techniques. And, each needs only a beholder to provide beauty.

It IS THE PURPOSE of the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission to practice the husbandry of the state's wildlife, park and outdoor recreation resources in the best long-term interests of the people.

Toward that end, many considerations and goals must be met and dealt with, and the system under which we operate must be occasionally re-evaluated and changed. Part of the problem of overseeing the husbandry of wildlife is dealing with people of diverse interests, backgrounds and attitudes. Some are hunters, others anti-hunters, yet all must find some common ground in order for everyone to live together. Conservation of the wild community ultimately rests in the attitude of the citizens and the value they place on wild things.

It is the purpose of NEBRASKAland Magazine, and of this special Bi-Centennial issue, to try to foster a better understanding and appreciation of the natural world and man's role in it. We strive to provide a means whereby Nebraskans can see themselves as a part of a total community of soil, water, plants and animals which make up our life-support system.

144