NEBRASKAland

December 1975

NEBRASKAland

VOL. 53 / NO. 12 / DECEMBER 1975 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Fifty cents per copy. Subscription rates $5 for one year, $9 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Single Copy Price: 50 cents commission Chairman: jack D. Obbink, Lincoln Southeast District (402) 488-3862 Vice Chairman: Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 2nd Vice Chairman: Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-Central District, (308) 745-1694 Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-central District, (308) 452-3800 H. B. "Tod" Kuntzelman, North Platte Southwest District, (308) 532-2982 Director: Willard R. Barbee Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, Jr. Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: Jon Farrar Greg Beaumont, Ken Bouc Contributing Editors: Bob Grier Faye Musil, Tim Hergenrader, Roland Hoffmann, Bill Janssen, Ben Schole Art Director: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1975. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska Contents FEATURES THE SILVER SEASON 8 WELCOME WOOD DUCKS 12 SHOOTING COACHES 16 A GATHERING OF WILDFLOWERS 22 FISHING CRAPPIE ON ICE 30 WILDLIFE DISEASES 34 A PHEASANT EXPERIENCE 36 TOYLAND 40 NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA/SWIFT FOX 50 DEPARTMENTS SPEAK UP 4 TRADING POST 49 COVER: Only the St. Deroin Cemetery remains of a once active and intense community of early day Nebraska. It is now within the boundaries of Indian Cave State Park in southeast Nebraska. Photo by Jack Curran. OPPOSITE: The flight of a flock of white-fronted geese on a misty, early morning is a thrilling sight for hunters and nature lovers, but is too seldom enjoyed. Photo by Greg Beaumont.

Speak up

River PollutersSir/The other evening several of us from Lincoln went to Brownville to take the riverboat ride. Seeing how many people that were getting on, we decided to go on top. About halfway through the night, it seemed that a lot of people forgot they were on what used to be a beautiful river. No longer were the trash cans used —in place of them, everything went into the river; beer cans, cups, papers, etc. No one seemed to care; in fact they seemed to enjoy watching those cans float down to who knows where. This went on for the rest of the evening, and when we got back to the dock, they really got with it. I guess everyone wanted to see if their beer can or cup would be smashed against the dock. Again, no one on the boat or dock seemed to care, so I guess it goes on all the time. It is a real shame, and I hope someday the state could help stop some of this.

Name withheldThere are penalties for littering and pollution—it is simply a problem of enforcement. There are more polluters than can be watched. Everyone seems to think a little doesn't hurt, not realizing that millions of such uncaring acts are what destroy things. Mass education is an endless project, because we are realizing that new problem areas arise. And, the more people, the more problems. We will alert the necessary authorities to the river problem in hopes it can be stopped. (Editor)

Deer Hunter's DelightSir / I have long awaited the magnificent article that appeared in your April '75 issue on "The Deer of Nebraska". Your staff is to be complimented on the wonderful pictures, information, charts and statistics that were included in the 34-page coverage of one of the most magnificent animals in the outdoor world. I know that every true deer hunter really appreciated your work.

As I write this, I am looking at the 10 mounted racks and two deer heads that hang in my living room. I am thankful that I have had the opportunity to match skills against such outstanding representatives of Mother Nature's gifted world. And, I thank not only her, but the great state of Nebraska for giving the chance to hunt these beautiful animals.

Anyone who thinks he has all the angles figured in the art of deer hunting is either kidding himself or has never really matched wits with the intelligent creature. Again, I want to commend the NEBRASKAland staff for the article. It was truly a "deer hunter's delight".

Greg Rogers Nebraska City, Nebr.Thank you for the kind words for the deer publication, and I hope most other deer hunters and wildlife buffs enjoyed it nearly as much. Reprints are available free by writing the Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebr. 68503, or they can be picked up at district offices. Other similar works have been done or are scheduled on grouse, quail, antelope, turkey, and pheasant. Considerable time and effort goes into them, and we hope that readers find them of value and interest. (Editor)

Coyote HuntSir / Thought you might be interested in this old photo of a coyote hunt I participated in as a young lad in Fillmore County in 1916. They were very popular back then, and traditionally they covered 16 sections of land, an area of four miles square, with everyone walking a little over two miles to the center or roundup area. This group, photographed on a convenient haystack, I believe only garnered four coyotes, along with a few rabbits. The hides were shipped to Chicago.

Loyd Russell Lincoln, Nebr.Sir / Fishing was great at Branched Oak. This whopper weighed in at 21 Vi pounds and was 34V2 inches long. I caught it on a telescoping rod while fishing for bluegills. I had a small crappie hook and 12-pound monofilament line.

When he decided to go to the bottom for one more time, my rod almost went along; it bent to a 45 degree angle and I had to bring him in by hand.

Lloyd Hendricks Omaha, Nebraska Center SchoolSir/This is in regards to Center School, District 65, Nemaha County, on page 8 of your August 1975 issue. I was delighted to see a picture of the school in that issue of the abandoned country school. It is where I started my learnin' career. It is located 7 miles north of Auburn on Highway 275-273, earlier known as the "King of Trails".

Nothing has changed in regard to the outside appearance. I rode my pony to school the first Monday of September over 60 years ago. We lived one mile north. My whole family attended this one-teacher school for their primary education and junior high.

Vividly in my mind is the huge college dictionary on its very own shelf; the globe suspended from the ceiling, raised and lowered by rope and pulley; the red-back Sears and Martin readers for grades one through eight; the rows of lunch pails in the hall, with the water fountain in the corner, and the rope that was fastened to the big iron bell in the belfry that was rung at 8:30 each school day, alerting the children if they were loitering down the road.

We felt lucky when we were appointed by the teacher to get the cobs and wood, the water from the well or dust the erasers. How the entire school looked forward to the annual school program and box supper. Old settlers in the district included the Bernards, Lavignes, Clouses, Burgers and Nincehelsers.

Yes, it is abandoned as far as children are concerned, but lots of memories are recalled as former pupils pass by on the old "King of Trails".

Lenora Bernard Parker Hastings, NebraskaNEBRASKAland Magazine invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to Speak Up. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters. — Editor.

WATER POLLUTION CONTROL

Blue Ribbon

CONTRACTING

ST. PAUL, NEBR.

REMOVE:

SEDIMENTATION

MUCK

WEEDS

SILT

SAND

SLUDGE

INDUSTRIAL WASTE

HYDRAULIC FILLS

NO JOB TOO LARGE OR SMALL

381-1223

GRAND ISLAND

BIDS-

GIVEN

754-5211

ST PAUL

ST

PAUL

Every trip doesn't have

to be a hunting trip

Why shoot your fun searching

for a pleasant place to stay?

Phone ahead before you go.

THE LINCOLN TELEPHONE CO.

HUNTERS

Eat and/or

stay overnight

Cafe-

Modern Motel

J'S OTTER CREEK MARINA

North Side Lake McConaughy

Open 4:30 a.m. till 7 p.m. daily

Ask about meals & lodging special

$13.75 per person per day

Hunting permits, Ammunition,

General Hunting Supplies

Phone LEYMOYNE (308) 355-2341

P.O. LEWELLEN, NEBR. 69147

Jay & Julie Peterson

The Commonwealth now pays

even higher interest rates!

6.25

Passbook Savings

6.54

Annual Yield

Comp. Daily

6.75

1 Yr. Cert.

7.08

Annual Yield

Comp. Daily

7.00

2 Yr. Cert.

7.35

Annual Yield

Comp. Daily

7.25

3 Yr. Cert.

7.62

Annual Yield

Comp. Daily

8.00

4 Yr. Cert.

8.45

Annual Yield

Comp. Daily

A substantial interest penalty, as required by law, will be imposed for early withdrawal.

THE

TH

COMPANY

126 North 11th Street / Lincoln, NE 68508 / 402-432-2746

Chartered and Supervised by the Nebraska State Department of Banking

NEBRASKAland

BICENTENNIAL SPECIAL

NEBRASKAland

Calendar

BIG 9"x12" PAGES

Featuring . . .

12 beautiful scenes

printed in full color.

Historic highlights.

Bicentennial products

shown in "Country Store

Plenty of room for

appointments, special

notes, etc.

//

ORDER YOUR

COPY NOW

Ideal for

gifts too!

TO: NEBRASKAland

P.O. Box 27342, Omaha, Nebraska 68127

Gentlemen:

Date

PLEASE PRINT CLEARLY

Please mail, postpaid,

(quantity) Calendars at $2.00

each (plus tax, if any).

Total enclosed $

Nebraska residents add sales tax

Omaha, Lincoln and Bellevue, 3-1/2%

outstate, 2-1/2%.

My check is enclosed

Money order enclosed

NAME

ADDRESS

CITY

STATE

ZIP

NAME TO SHOW ON GIFT CARD, IF ANY

USE EXTRA PAPER FOR ADDITIONAL NAMES AND ADDRESSES.

WATER POLLUTION CONTROL

Blue Ribbon

CONTRACTING

ST. PAUL, NEBR.

REMOVE:

SEDIMENTATION

MUCK

WEEDS

SILT

SAND

SLUDGE

INDUSTRIAL WASTE

HYDRAULIC FILLS

NO JOB TOO LARGE OR SMALL

381-1223

GRAND ISLAND

BIDS-

GIVEN

754-5211

ST PAUL

ST

PAUL

Every trip doesn't have

to be a hunting trip

Why shoot your fun searching

for a pleasant place to stay?

Phone ahead before you go.

THE LINCOLN TELEPHONE CO.

HUNTERS

Eat and/or

stay overnight

Cafe-

Modern Motel

J'S OTTER CREEK MARINA

North Side Lake McConaughy

Open 4:30 a.m. till 7 p.m. daily

Ask about meals & lodging special

$13.75 per person per day

Hunting permits, Ammunition,

General Hunting Supplies

Phone LEYMOYNE (308) 355-2341

P.O. LEWELLEN, NEBR. 69147

Jay & Julie Peterson

The Commonwealth now pays

even higher interest rates!

6.25

Passbook Savings

6.54

Annual Yield

Comp. Daily

6.75

1 Yr. Cert.

7.08

Annual Yield

Comp. Daily

7.00

2 Yr. Cert.

7.35

Annual Yield

Comp. Daily

7.25

3 Yr. Cert.

7.62

Annual Yield

Comp. Daily

8.00

4 Yr. Cert.

8.45

Annual Yield

Comp. Daily

A substantial interest penalty, as required by law, will be imposed for early withdrawal.

THE

TH

COMPANY

126 North 11th Street / Lincoln, NE 68508 / 402-432-2746

Chartered and Supervised by the Nebraska State Department of Banking

NEBRASKAland

BICENTENNIAL SPECIAL

NEBRASKAland

Calendar

BIG 9"x12" PAGES

Featuring . . .

12 beautiful scenes

printed in full color.

Historic highlights.

Bicentennial products

shown in "Country Store

Plenty of room for

appointments, special

notes, etc.

//

ORDER YOUR

COPY NOW

Ideal for

gifts too!

TO: NEBRASKAland

P.O. Box 27342, Omaha, Nebraska 68127

Gentlemen:

Date

PLEASE PRINT CLEARLY

Please mail, postpaid,

(quantity) Calendars at $2.00

each (plus tax, if any).

Total enclosed $

Nebraska residents add sales tax

Omaha, Lincoln and Bellevue, 3-1/2%

outstate, 2-1/2%.

My check is enclosed

Money order enclosed

NAME

ADDRESS

CITY

STATE

ZIP

NAME TO SHOW ON GIFT CARD, IF ANY

USE EXTRA PAPER FOR ADDITIONAL NAMES AND ADDRESSES.

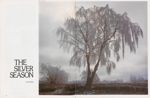

THE SILVER SEASON

photo by Faye MusilHOARFROST is a fantastic creation that winter gives us as a reminder of its power to transform. A softly frozen dew that covers the landscape with a fuzzy, almost unreal coating, hoarfrost is easily melted by the first rays of the sun. There is a silence about hoarfrost; it seems distant and delicate. And, as the sun breaks through clouds or fog, there is a quiet rustle of bits and pieces falling from the trees and shattering on the ground below.

There is a hint of cold that still tempts the shedding of coats to feel its touch—like wading in a spring-fed stream. There are filmy ice crystals on the heads of last summer's sunflowers, and only the ghost of a sun, trying to break through the eerie overcast that shrouds the frost. There are cascades of weeping willow that the pale sun seems to highlight, to hover over.

An unusual balance of circumstances combine to create the special frost. The air must be still, the temperature around 30.4 degrees but not much lower, or the frost will be hard and solid rather than soft and delicate. There must be ample moisture in the air; moisture that condenses in thick layers on the cooler surfaces that it touches. And, what a fortunate coincidence, after all, that these conditions occasionally combine to give us hoarfrost. It is one of those visual treasures to be deposited in whatever storehouse there is inside the mind to record and retrieve those experiences that we dwell upon in leisure.

Wood Duck Welcome

Already active, sportsman's club in Sand Hills takes on new project of prividing housing for waterfowl

AS IF THE Sandhills Rod and Gun Club wasn't already doing enough, club member and State Conservation Officer, Max Showalter, came to his feet at a regular monthly meeting and suggested that the club take on still another project in the interest of conservation.

The suggestion was simple: that the club build and erect nesting boxes for the few wood ducks naturally inhabiting the area. Even though implementation of the project would be time-consuming and demanding, Showalter knew that his suggestion would not fall on any deaf ears, even though fellow members were already throttled with responsibilities from other worthwhile projects.

"As a conservation officer, I've worked with a number of sportsman's clubs, but the Sandhills Rod and Gun Club is the most active and most cooperative organization I've ever been associated with." Showalter's assessment of the character of his club held once again as its energetic members endorsed his proposal with over whelming enthusiasm.

The Sandhills Club boasts a generous membership of nearly 200 men, primarily comprised of Ainsworth area citizens, but over its 30 years of existence, it has drawn a statewide enrollment. The longevity of this sportsman's fraternity is not merely founded on the fact that a unifying title has bonded its membership in print as a recognized organization, but that its true strength is derived from its ability to remain active, and to keep all its members active. To do this, projects are readily accepted which the members feel are workable and worthwhile, and that best exemplify the fulfillment of the goals which brought its founding fathers together 30 years before. Besides regular annual activities, such as the spring clean-up of Pine Creek and several Sandhill lakes, coupled with their post hunting season mailbox-maintenance programs, during which members drive country roads and repair and replace mailboxes destroyed by vandals, the Sandhills Rod and Gun Club instructs a continuing Nebraska Hunter Safety course. Members also hold weekly trap shoots and an annual trophy shoot. They are now in the real estate business, as they are actively involved in acquiring land for public recreation, and on some of these lands have developed substantial public fisheries from existing ponds. They have been instigators of public surveys to determine the status of hunter-landowner relations. Then, through the results of these surveys, campaigns have been launched to remedy any existing hard feelings.

Ainsworth is located on the southern perimeter of the Niobrara River Valley. Tributaries drain the Sand Hills and run north into the river, providing a network of streams and aquatic habitat. As the streams converge on their Niobrara destination, bayous are formed and trees become more and more prevalent in the form of ponderosa pine, bur oak, cedar and cottonwood; a drastic change from the environment typical of the vast hills of sparsely vegetated sand just south of U.S. Highway 20, the town's "main drag".

Showalter regularly patrols the area, and over the summer months he became cognizant of the fact that many wood ducks were present in this northwestern Nebraska area; an area not generally known for its ability to support a breeding population of the magnificently gaudy wood ducks. Nevertheless, they were there, and as Showalter assessed the situation, the greatest limiting factor to increasing their population was a lack of natural cavities for nesting.

Wood ducks, as the name implies, refers to the bird's nesting and resting habits, and not to any physical characteristics of appearance. Unlike the majority of their web-footed relatives, who desire grassy, down-to-earth abodes, "woodies" search out hollow, high-rise arbors, then carpet them with wall-to-wall down on which they place a dozen eggs and sit back and enjoy the comfort of their lofty bedroom. They have been known to move into hollow branches more than 50 feet above the ground, but with the demand these days on nature's housing, one can't be too choosy or it'll end up playing second fiddle to a maternal-feeling screech owl.

With the knowledge that the birds would be arriving as early as the middle of March from their southeastern coastal-states wintering grounds, a solid plan was necessary to expedite the project so that tidy homes would be ready to greet the returning pairs.

Gaining use of a private airplane, club members made aerial inspections of the Niobrara valley and its tributaries. They were looking for the river's slower moving backwaters and isolated marshes formed by low pockets in the meandering streams. When areas were sighted which appeared from this distant bird's-eye viewpoint as suitable wood duck habitat, it was so designated on a map.

Later, by boat, canoe, four-wheel drive or on foot, access was gained to the map-marked areas for closer examination to determine if the area was a truly desirable prospect as a nesting site.

Nesting habitat potential is only one aspect that must be considered when attempting to propagate wood ducks, or, for that matter, any other species of wildlife.

For wood ducks, brood cover is important, and a considerable abundance of peripheral pond vegetation must be present. Extensive overhanging shrubbery is ideal as it provides a protective tunnel/canal through which broods may swim and feed freely.

Certain types of aquatic vegetation sometimes provide adequate substitutes if there is a scarcity of close bank shrubbery. This can be a variety of cattails, bulrushes, smartweed, arrowheads and sedges. This was the type of thing that members of the Sandhills Rod and Gun Club were obviously looking for during their detailed examinations of the possible brooding areas.

Fourteen areas seemed to meet nature's blueprint for the wood duck housing code. Backwaters of the Niobrara provided eight housing locations. Bone Creek had three suitable sites, Pine Creek two, and Plum Creek had one.

Cecil McCullough, last year's club president, owns and operates his own sawmill, and with the plans for wood duck houses supplied by the Game and Parks Commission, cottonwood logs, donated by McCullough, were split into chunks and then sawed into boards. Steel poles were begged and borrowed through methods only energetic clubs have the ability to employ.

Each house required 10 linear feet of 1x12-inch lumber, as they were constructed approximately 20 inches high and 12 inches square. The box was provided with an overhead shelter by means of a roof which protruded over the front of the house. The front board was hinged to allow access for cleaning out the interior, and an elliptical 4x3-inch entrance hole was cut in the upper third of the board. The exactness of the shape and size of the entrance hole is important as it is just large enough to allow the female wood duck to pass through, but small enough to prevent adult raccoons from entering and destroying the nest. A strip of hail screen was attached to the inside of the door, down from the access hole. The screen would provide a ladder up which the newly hatched ducklings could climb

when leaving their nest.

As with all fine homes, the finishing touches were applied —a fresh coat of paint—inside and out. The color scheme is important, as it is prescribed to use a stain or paint that will not produce a sheen or glare. Club members chose to apply a personally blended pigment of beige and gray, and two coats of flat black adorned the interior walls. The boxes were then complete, but the real work was yet in the offing.

The setting of the poles proved to produce equal coatings of mud and perspiration on the bodies of the volunteers who found themselves belly deep in cold March water. The work offset the chill of the recently thawed bayous, and the icy water cooled the heat generated by the exertion involved.

Steel poles were driven firmly into the floor of the marshes, 10 feet from the bank. The poles were set to a depth where the tops just protruded above the surface of the water. Permanence was the theme of the operation, and it was realized that submerged wooden poles would eventually rot, and the same miserable task of resetting new poles would have to be undertaken at that time; a situation which would probably result in a decline in membership of the Sandhills Rod and Gun Club. Houses can and sometimes are attached directly to trees with equal success except that predation is harder to control when using this method.

Oversized cottonwood 2 x 4-inch poles were then attached to the top of the steel poles and a strong hinge placed at the junction. Since a mother wood duck requires meticulous house cleaning prior to her return from the wintering grounds, club members felt it would be beneficial to be able to walk out on the ice during her absence and let the pole down rather than scaling it to the house, which was placed 15 feet in the air. This would more easily facilitate the removal of last year's down, egg shells, droppings, or other animal nests which may have accumulated over the winter. Wood ducks will very seldom use a dirty box.

A predator band was then attached to the pole to discourage climbing by raccoons and other hungry night visitors, and a thick bed of cottonwood shavings was spread on the floor of the house.

Needless to say, there was quite a celebration at the raising of house number 14, and the occasion came none too soon, as woodies were seen arriving in the area soon after.

The work paid off for the dedicated club in the upper Sand Hills, as broods of 8 to 10 downy ducklings were observed with the comparatively pallid females in the vicinity of more than half the houses, a ratio that any club could be proud of. Winter nest cleaning was hoped to confirm an even higher percentage of verified house usage.

Members were fortunate to observe a hen calling encouragement to her brood of day-old ducklings, and to watch them reluctantly heed her commands to make the 15-foot leap, like student paratroopers making their first jump. That one incident more than repaid all their efforts, they felt.

This year, the Sandhills Rod and Gun Club has erected 14 additional nest boxes, their continuing work with the project partially due to the gratification from the success of the initial program. They are also somewhat obligated to their task, since the female wood ducks reared in the Ainsworth area are now prone to return to the same nesting grounds, bringing along their colorful mate, once again in the market for a house.

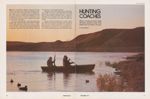

HUNTING COACHES

When it comes to ducks, these Wauneta teachers know their beans and put birds in the pot

photos by Lowell JohnsonTHERE IS SOMETHING different about duck hunting than most other types of gunning, although it is difficult to put a finger on exactly what it is. Perhaps having to hide out in a concealed area to keep their sharp eyes and suspicious natures from detecting you has something to do with it—or that you must rely on a call to entice them from their course, whatever that might be, into the area of the blind.

Of course, sneaking into a water-side blind before daylight after arising sometime shortly after the middle of the night would give almost any activity a certain aura of unreality. Such was the case in mid November of 1974 as four coaches from the Wauneta school and I prepared to hunt from their blind located at the end of a precipitous road at Enders Reservoir.

Although such ventures were far from new for them, it was hardly so for me, as it had been years since I had duck hunted. Stumbling along with them in the half light of morning after a half night's sleep, I vaguely remembered why it had been years. But, their quiet enthusiasm and good spirits were enough to dispel any qualms.

The duck blind was located out on a point, with a cove behind it at the base of tall bluffs. In front was the lake, with the shoreline extending fairly straight in either direction. We arrived over a half-hour before shooting time, which was 15 minutes before sunrise, and that apparently gave enough latitude for chores

around the blind. This included, I found, a shaping up

of the spread of decoys. While I stood and watched and

shivered, although it wasn't really that cold, the four

coaches went about their business. Jim McKinney and

Bob Troudt seemed occupied with a small herd of imitation Canada geese positioned on the land which

formed the point of the peninsula. Roland Johnson and

Larry Kitt placed duck decoys into the shallow water

along the shore, and propped others onto short sticks

poked along the water's edge.

around the blind. This included, I found, a shaping up

of the spread of decoys. While I stood and watched and

shivered, although it wasn't really that cold, the four

coaches went about their business. Jim McKinney and

Bob Troudt seemed occupied with a small herd of imitation Canada geese positioned on the land which

formed the point of the peninsula. Roland Johnson and

Larry Kitt placed duck decoys into the shallow water

along the shore, and propped others onto short sticks

poked along the water's edge.

The sky was partially overcast and a slight breeze wafted parallel with shore, and it appeared that all the decoys had to face into the wind. The goose decoys, I noticed only after close examination, were fashioned from cut-up tires with wooden necks and heads affixed. Despite the materials, they looked quite realistic.

Because of the relatively warm weather, little frost had formed on the floating decoys, so it was not necessary, they felt, to go out among them and wash them off. A can was used to souse those on shore, which did improve their appearance, giving them a darker cast.

Jim's two dogs, female Labs, frisked about the area and seemed to inspect the decoys as well. Shannon, the older, just days before had a litter of pups, and Cinder, Shannon's daughter, was very apparently in a family way. Before that day was over, those dogs would prove how invaluable retrievers are in the sport of duck hunting.

The blind was rather unimposing from the outside, looking only like a few shocks of corn tossed together in a heap. Inside, it was a different matter, as there was a roof over all but the shooting area, a bench for resting, and there was plenty of room for all five of us to stand with room to breathe. There was even a stove to heat coffee and chocolate and soup, which turned out to be one of the most popular pastimes during the lulls in action.

Within a few minutes we were ready to get out of sight and into the blind, but it was difficult to talk because we had to listen for any telltale quacking and leave silence for any whisper of alert anyone might give.

Still, we were able to discuss a few things, and I learned that three or four of the coaches hunted from the blind virtually every day of the season, although it was usually only for about 45 minutes during the school week. Then, they would drive the few miles from town, over the rough and winding road from the highway to a point about 150 yards or so from the blind.

"Usually we have to leave just when the flights get good, but some mornings are better than others" whispered Jim McKinney. "Of course, on weekends we spend most of the day here unless things are real slow."

Only Larry Kitt is a native of the area. Roland Johnson, the head football coach and physical education teacher at Wauneta Consolidated School, was in his first year at the school, and was from Wausa. His wife, Connie, was expecting their second child any moment, so it was with some trepidation that he was even along on the hunt.

Bob Troudt, originally from Nelson, was head bas- ketball coach, assistant on football, and also taught math and related math and driver's education at the 170-student junior and senior high. He, Jim and Larry were all in their 5th year of teaching there, so they had that many seasons of duck hunting in the area.

Jim McKinney was industrial arts instructor, as well as basketball coach, and Larry Kitt was a junior high coach and taught science, math and physical education. He also farmed with his father nearby.

Almost everything that went on during each day's hunt was subsequently entered in a log which Jim kept. Thus, success, weather and many other interesting facts could be studied and compared.

When it was still being discussed as to whether to open the thermos of coffee or not, a flight of ducks was spotted somewhere in the distance, and McKinney, apparently the most accomplished caller, was pushed into the forefront to do his thing. It was several minutes be fore I could see the ducks, although all the others had them spotted instantly, and seemed to know if they had a chance to lure them in.

For about two hours it was pretty hectic, I thought, with flights of ducks passing by sometimes in range, oftener not, but seeing so many was enough to make the morning go fast. There was the feeling of being a Jack-in-the-box, as whenever anyone would spot birds, we would duck down and wait for the signal. Then, it would be up and look quick to locate the ducks after someone wou Id say what they were.

While it seemed we were always busy, either scanning the skies or hopping into or out of cover, my companions explained that this was pretty slow action for this time of year. The duck season was split in 1974, and the first half ended on Sunday of the weekend we were presently enjoying. This bothered the four coaches, as they were convinced it would mean a virtual end of the season for them.

"By the time the second half opens," Jim McKinney said, "the reservoir will be all iced in and the ducks will move out, except for possibly an area over on the refuge. Right now is usually when the flights really get good. I suppose there is a reason for the split season, but it sure doesn't do western hunters any good. We'll just have to wait and see, though."

Before there could be any further comment on the situation, another wedge of clucks was spotted and it was back under cover as someone started hooting on a call.

Strangely, the coaches commented later, few of the ducks moving around were mallards. In fact, oftener than not it would be a teal or ringnecks or ruddies that would come by and check in at the setup. Some mallards were moving, but mostly far to the west and high up. There were also some fooling around near the dam, but we needed binoculars to see them.

But, there was plenty of shooting, although not nearly as much hitting. At times, I knew where I was

Split duck season was about to interrupt

hunting just as weather was changing, so

this November weekend was a special date

Split duck season was about to interrupt

hunting just as weather was changing, so

this November weekend was a special date

missing, but usually even that satisfaction was absent. But it was nice to be in on the action, and I am still convinced that I hit one or two of the ducks that we garnered during the morning.

On four occasions, lone mallard drakes or doubles came in range, but never any of the big groups we could see in the distance. Of these, we knocked down four drakes and enjoyed the retrieves of Jim's Labradors. When sent out to bring in a duck, Cinder or Shannon would yelp excitedly all the way out to the duck, as if they couldn't get there fast enough.

Jim got concerned on one retrieve, of one of the three ringnecks that we scored on during the morning, when Cinder couldn't keep up with its diving maneuvers. In her delicate condition, the added exertion and frustration of chasing that pesky diver must have been gruelling for her. Finally, there was sufficient space between them that Jim nailed the duck again, putting an end to the chase.

Without a doubt, it was the joviality and comradeship that makes such hunting a pleasure. In fact, there was as much or more fun during the lulls as when the action was heavy. Breaking out a jar of peanut butter and crackers was an event, as a lot of kidding went on when we, like a bunch of hungry baby birds, reached for samples as Bob knifed the thick peanut butter.

With a tally of four mallard drakes, three teal, three ringnecks, one canvasback and two ruddy ducks, the activity seemed over for the morning. But, rather than give up, we decided to see some of the rest of the reservoir, and to check on the congregations in the refuge portion.

Piling back into the pickup, we wended our way over the rough roads to a point overlooking a portion of the refuge, but there were not nearly as many ducks around as the coaches had expected. There were hundreds and perhaps thousands, but not the tens of thousands that might have been there.

Deciding to walk around to a point to see if they were farther up the arm of the lake, we hadn't gone far when Roland Johnson dropped a lone mallard drake that was hiding in a cove. The shot was heard by another teacher from town, who had come out to retrieve Rollie. He told him that his wife apparently didn't want to wait until that afternoon, and had gone to the hospital to have her baby.

The rest of us returned to the blind, but only to enjoy the view for another hour or so before also returning to Wauneta. In addition to looking forward to another great morning in the blind the next day, the guys had planned a fantastic dinner that evening, with a wide range of Nebraska game on the menu. That was as memorable as the hunt.

Just as early the next morning and with as little sleep, we were again slipping down the hill to the blind. Larry Kitt couldn't make it that morning, but Roland, now with a new son, was there, along with Jim and Bob.

If anything, the weather was even more beautiful than the day before, which forebode ill tidings for duck hunters. The lake was as the proverbial glass and the sky bright and clear. This, as the coaches said, was hardly the type of day they would have asked for to observe the close of the first half of the season.

Absolutely nothing was moving anywhere, as the ducks were apparently happy where they were when the sun came up. It seemed like about an hour before anything was attracted into our set, but then for a couple of hours there were some great times. On one of those occasions, a pair of redheads came by, and Bob Troudt, who perhaps had missed on some earlier shots or something, dumped one of the ducks at such close range after it had swung around behind the blind, that it landed on the point only 20 yards from us.

He immediately chastised himself, but that didn't save him from the others. Such things as "You don't have to put every single BB in them," and "You don't have to shoot and pick at the same time", were his rewards. Surprisingly, the bird wasn't torn up, but Bob regretted the close shot anyway because of the razzing.

It was fairiy late in the morning, perhaps 10 a.m., when the big moment came. According to Jim's diary of that momentous day, he recorded downing three ducks-the redhead that Bob "murdered at close range, and two widgeon. Then it happened! We heard geese. To be exact, we heard goose. A loner came up east side of the blind."

What happened after that was sheer pandemonium. The six of us, four hunters and two dogs, crouched low but most eyes were glued to that unsuspecting goose. He was probably debating whether to stop by and visit with those geese and ducks resting down below, until he got alongside that pile of vegetation. Then things got wiid as four gunners tried to zero in on him. At least 10 shots bellowed out before he finally dropped, then he was only winged. A gradual drop to the water, then the young Canada started swimming. The dogs took off after him, but Jim had to call them back as he easily outdistanced them.

It was a silent-comedy scene for the next few minutes as hunters dashed off to the east, unsheathed a small boat and began paddling off across the lake. Soon, the boat was only a speck in the distance as it crisscrossed in pursuit and finally caught up with our prize. It was the first goose I had ever shot at, let alone possibly hit, and it was the first of the season for my companions. We had seen five or six large flocks the previous day, and one flight was heading directly toward us within shooting height until they flared from a fisherman across the bay from our blind. That had been a major disappointment—one of those times that try the soul and flavor the language.

The arrival of our crew and goose from lakeside was one of joviality, and also brought an end to the shooting activity except for a short excursion by Jim, who spotted a duck way back in the cove behind our blind. "It must have sneaked in without our seeing him", he surmised. Thereupon he pulled a masterly sneak on the brazen duck, skulking through the brush and trees until he figured he was right on top of it, then vaulting out onto the bank for the anticipated spooking of the duck. His quarry, however, turned out to be only a scrawny beverage container, but it took a load of six shot in the hindquarters anyway. Thus ended the weekend hunt.

Reflecting on the split season with a brief wrap-up is this excerpt from Jim's diary:

"We had poor pond shooting this year because of no water, but lake success was about normal. We missed getting any snow days to hunt, and that's when we score most. We missed the best hunting days this year because of the split season that began November 18 and will last until December 14. Our prime hunting areas will be frozen by then and we will have a hard time finding a place to put decoys. Goose shooting is still good but we rarely hunt geese unless we combine a duck hunt, because of the unpredictable geese and few that stay around here. We probably end up with two weeks that tend to be good northern duck shooting. I guess we can be thankful for that."

I was thankful too —for the chance to enjoy the company and facilities of some good hunters and nice people. All hunting trips may be good, but some are certainly more pleasurable than others, and such was that Enders outing. That lone goose was enough to make it a success, but there were many high spots in those two days.

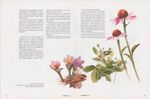

Colorless December, cold, brittle as glass: I think of the ruined flowers, pressed prone By woodland snowbeds, stung and jabbed By the prairie snow-sleet, waiting, Waiting to bear again a triumph of many colors

A Gathering of Wildflowers

Art by Michele Angle Farrar

IT IS NOT EASY to regard the March prairie, extravagant with pasqueflower, in a detached fashion; to encounter a woodland meadow proclaiming ladyslipper and bloodroot and not feel an electric charge. Even a child responds.

Can it be that human blood recognizes some ancient significance here, something deeper than a tossing beauty of color and form? Perhaps the recognition that our own evolution is rooted here? Link by link, if we trace the lifechain far enough back, we discover that the evolution of man was dependent upon the prior evolution of flowering plants.

Geologically, the earth's spectacular explosions of bird and mammal species are yesterday events. As recently as a hundred million years ago, during the close of the Age of Reptiles, angiosperms — flowering plants —had not yet evolved. Plant reproduction still belonged to the kingdom of gymnosperms, the ancient, non-flowering forms of spore and pine cone.

During the Cretaceous Era, the old, slow, tropical order of life on land began to change. Tropical climate changed to temperate extremes during this period; the dominion of cold-blooded dinosaurs was extinguished. The moisture-sensitive coniferous forests, which had so long mantled the land in green monotony, began to shrink.

Evolving flowering plants, nurtured by the stimulus of rudimentary insect forms, provided a solution to the developing ecological void. Grasses, forbs, shrubs and deciduous trees adapted to and flourished in the cooler, drier climates.

Plants and insects had long been involved in a life-and-death struggle. With the advent of angiosperms, a mutually beneficial relationship developed. The flowering plants produced a food source for insects; the insects assisted the sexual reproduction of the plants. No longer did the plant kingdom rely solely on wind and water as agents of fertilization.

Because of this partnership, insects rapidly diversified, evolving new, specialized forms, such as bees, moths and butterflies.

The most dramatic result of angiosperm evolution was the stimulus it gave to two recently evolved classes of animals —birds and mammals. Warm-blooded animals, because of their high rates of metabolism, require an abundant supply of readily available, high-energy fuel. Angiosperm means "encased seed/ Unlike gymnosperm seeds, which contain no protective covering, angiosperm seeds are surrounded by a fruit. The development of these highly nutritious seeds, along with the attendant explosion of insect species, insured the experiment of feathered furnaces called birds.

As the birds diversified into seed-eaters, insectivores and birds of prey, the mammals too —uncertain little creatures which, in primitive, rat-like forms had scuttled among

the feet of dinosaurs —began their rapid rise to dominance.

The development of grasslands —a new biotic community capable of enduring a climate of low annual precipitation and seasonal weather extremes — promoted and supported its own explosion of mammal species, including, eventually, homo sapiens. It is no accident that all the great civilizations developed near the grasslands, where the domestication of livestock and the cultivation of cereal grains were possible.

In particular, I remember one morning. It wore the cloudy countenance of late April along the Missouri. I was sitting statue-still on a downed log listening to nearby leaf scratchings and hoping to get a glimpse of the busy ovenbird. The bright, diffuse light made the woods glow, as if the bald, featureless sky was a mirror and not the source of the surrounding spring radiance. At my feet a loose colony of Dutchman's breeches stood in white conquest above the leaf-litter of the former summer. Blue torches of phlox spikes stood about, and here and there wood violets stained the brown, leaf-strewn floor yellow, white and blue. So intent had I been to sight the drab, secretive bird, I had not read this other message, everywhere displayed. As I looked around, I rapidly discovered a succession of other flowers —lady slipper and May apple—new species added to my awareness of this patch of woods.

It must have been similar to the earth itself, suddenly sponsoring such a fever of new forms, colors and fragrances. I began to think of the wonders of adaptation so casually represented here; the mysterious methods the earth chooses by which to perpetuate itself, the unlightable geologic pit beneath the bright, shallow throat of a yellow violet.

How do we unravel the background of the bee; the stunning, impossible blueprint of xthe hummingbird; the dare of metamorphosis twice flaunted by the yellow and black wings of the tiger swallowtail?

There is no answer, of course. Only the continual scratchings of an ovenbird somewhere beyond our vision; or the brief, wordless statements wild!lowers make in the hard, motionless month of December when the memory of April stirs.

FISHING... CRAPPIE ON ICE

WHY WOULD HUNDREDS of otherwise sane and rational people leave their warm homes on frigid winter nights to risk frostbite and pneumonia on a cold, dark slab of ice?

For fish, of course! Not just a few, but dozens, maybe even hundreds of crappie.

Usually beginning in the latter part of December, when Salt Valley lakes sport four inches of ice or more, people from the Lincoln area flock to the ice after finishing their day's work. The most productive and popular area, Pawnee Lake, will have so many fishermen and their gas lanterns by dark, that the area off the dam will resemble a rather respectable-size village, and the parking lots near the dam will be filled to overflowing.

On many nights during the week, the crowd at Pawnee Lake numbers one or two hundred, and it doubles during weekends.

Fisheries biologists have estimated that the harvest of crappies from the dam area of Pawnee Lake, alone, is from one to two thousand pounds offish per night when fishing is at its peak. The biologists say this harvest approaches maximum use of the resource, without damaging the population.

Despite temperatures that often drop to near zero, and winds that magnify the effect of the cold, a carnival atmosphere usually prevails on Pawnee. Newly arrived fishermen wander among others until they find a spot that appeals to them. Then, it's a matter of starting the gas lantern, cutting holes, baiting up and getting lines in the water and setting up the rest of the paraphernalia.

After a few days of heavy ice fishing pressure, fishermen no longer have to bother cutting new holes, because the entire productive area is dotted with those used the night before. Unless it's been bitterly cold, old holes can be reopened with a minimum of labor.

Ice fishermen are an inventive lot, especially when it comes to providing for their comfort while on the ice. Their equipment includes shelters ranging from fancy ice shacks complete with roof and windows, to simple windbreaks consisting of a plywood lean-to, a large cardboard shipping crate, or just a sheet of cardboard they wrap around themselves.

There's usually some sort of heat source. Some have special heaters made for camping, while others resort to lighting cans of Sterno, or coffee cans with a wick consisting of a roll of toilet tissue and fueled by lantern gas. Some also use a portable charcoal grill, which does

double duty in preparing hot dogs.

If things are a bit slow after the gear is made ready, fishermen often go calling on their neighbors to find out how they've been doing and to swap fishing lies about their last outing. The circle of light that envelops each party is likely to hold people of just about any shape, size or age.

Parked near one hole last year was a rather large cardboard box with one side cut out, and inside was what appeared to be a small bundle of warm clothing perched on a stool near a bright lantern. Only stubby, heavily gloved hands holding a rod and a cherry colored nose and cheeks poking out of the parka, told that there was a four-year-old fisherman inside.

The lantern and cardboard windbreak were keeping the youngster comfortable and the fishing action was keeping him happy. His dad stayed warm by removing fish from the fisherman's line and rebaiting his hook.

The law allows ice fishermen up to 15 lines, but few use more than two. Cutting all those holes is a lot of work, and when the action starts, a fisherman usually has more than he can keep up with if he has even two lines in the water.

The business end of the line is usually equipped with a light wire hook, usually No. 4 or 6, minnow and a few small split-shot weights a foot or so above the hook. Weights are added or removed until a small bobber at the angler's end will just barely float.

This delicate adjustment often spells the difference between success and failure. These winter crappie seldom take the bait with any enthusiasm. Most often the bobber will simply sink slowly from sight. Also, crappie sometimes grab the bait without moving off. Then, the only clue the angler has is a bobber that rises in the water just the tiniest fraction of an inch because the crappie at the other end is supporting the weight of the minnow and hook. When a crappie comes calling, the fisherman should set the hook gently, keep a tight line, and haul him in steadily.

Several common errors can cut substantially into the fisherman's catch. One is the tendency to use line, weights and bobbers that are too heavy. Four-pound-test monofilament is plenty adequate for the job, though six- pound mono may also work. Anything heavier seems to spook the fish, especially on those slower nights when the fisherman needs every break he can get.

Another mistake is to use the wrong hook. Crappie seem able to escape small hooks, but No. 4 or 6 work well. Light wire models seem to be a bit less visible to the fish than heavier versions of the same size. The other mistake that costs anglers fish is common to all crappie fishing- setting the hook too hard.

Most of the time, the crappie are caught from 15 to 25 feet below the ice. With this amount of line below the bobber, most of the line has to be pulled in by hand, and this makes for a lot of mono lying around on the ice. Wind and other fishermen tramping through the nearly invisible monofilament on the ice cause a lot of tangles, and fishermen often lose track of their own lines on the ice even when wind or clumsy partners don't interfere. Also, monofilament line gets stiff and kinky in the cold, and is almost impossible to handle with gloves on, and darn difficult to manage with cold-stiffened fingers.

Some fishermen have tried various slip-bobber rigs that allow them to store troublesome line on reels, but these setups often fail because ice forms on the line or in the bobber, making them inoperative.

One solution seems to satisfy at least some fishermen. They use a conventional ice rod, but equip it with 15-pound-test black braided line. A leader of a few feet of fine monofilament carries the hook and weights so that the heavy black line does not spook the fish. The braided line is easy to see on the ice, does not tangle or get stiff as easy as monofilament, and is easier to manipulate with gloves or cold hands.

The crappie seem to move in and out of the fishing area in bunches. Often, action is good only for one or two anglers, while another using a hole only a few feet away gets skunked. And fishing can go from very poor to very good in a matter of seconds. Many times, fishermen who have reached the limit of their patience and endurance begin to pack up, only to have a hungry school of crappies show up and catch them with their shelters down.

The winter crappie run at Pawnee Lake is about the nearest thing in Nebraska to guaranteed fishing, and some of the other Salt Valley lakes also produce crappie on a less dependable basis.

Branched Oak Lake ranked second in popularity last year, offering larger fish but slower and less regular success. Surveys during the summer and fall of 1975 indicate that the crappie population has declined there and should be a couple of years in rebuilding.

However, other Salt Valley lakes offer good ice fishing potential. Conestoga Lake might come closest to Pawnee in terms of numbers of crappie. Bluestem offers crappie potential largely untapped by ice fishermen, as do East Twin, Olive Creek, Yankee Hill and most other Salt Valley lakes.

The Salt VaNey certainly has no monopoly on nighttime ice fishing or on crappie. But, it seems that this particular technique is not used to a very large extent elsewhere in Nebraska.

There's no reason to believe that crappie could not be taken in other Nebraska lakes at night this winter. Most parts of Nebraska have some good crappie water, and there are plenty of ice fishermen in most areas with the required gumption and skill. If the fishermen decide to give night ice fishing a try, there's a good chance they might duplicate the Salt Valley's success.

WILDLIFE DISEASES

They exist, but seldom are cause for worry

BOTH PARASITES and diseases are common in virtually every wildlife population. Several have been recorded in Nebraska over the past several years, but they are not considered a major problem. The rate of occurrence does seem to be increasing, but this is probably due to more people being aware of and reporting the incidence. It is also quite likely that we will have an increase in wildlife diseases and related problems in the future. Much of this is due to a decrease of suitable habitat and overcrowding of some species during certain times of the year along with a general degrading of the environment.

The two most recent major outbreaks of wildlife diseases occurring in or close to our state were in January 1973 at Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge in South Dakota when some 40,000 ducks and geese died of duck virus enteritis (DVE) or duck plague; the other and most recent outbreak was in April 1975 in Phelps County where approximately 25,000 ducks and geese died of fowl cholera. These were both extreme cases of wildlife diseases and are shocking experiences.

On a smaller scale each year, many hunters and other outdoor people happen upon a bird or animal that is sick, shows signs of a disease or parasite, or when field dressing a bird or animal find an unusual looking liver or other organs that are abnormal. Their first thoughts will be, "what is it, is it edible, who should I contact?"

Many people who hunt waterfowl have sive, the host animal seems to experience little discomfort.

The parasite does not seem to affect ducks in any way. It may be found in most species of ducks, but mallard, teal and pintail are noted frequently.

If the parasites are found in slaughtered domestic animals, the carcass is rendered unfit for human consumption. In ducks, it would be safe to eat if cooked thoroughly.

Lead poisoning is another waterfowl-related problem that hunters may encounter. It is the greatest non-hunting source of mortality in North American waterfowl. Contrary to popular belief, lead shot in the flesh of waterfowl does not cause lead poisoning. Shot pellets in the flesh undergo slight, if any change, and are of little harm to waterfowl unless they have damaged vital tissues.

Lead poisoning is likely to occur in waterfowl that have swallowed lead shot pellets while feeding on the bottoms of lakes and marshes. When a shot pellet has come to rest in the gizzard of a bird, the surface of the pellet is eroded and dissolved away through the grinding action of the gizzard and its contents, along with chemical action of the digestive juices. The lead then undergoes further chemical change as it moves through the intestine. Some of the lead compounds thus formed are absorbed by the bloodstream through the intestinal walls and apparently damage the liver and kidneys. These lead compounds also appear to have a direct harmful effect on the muscles of the digestive

encountered "wormy" ducks. These are rice-shaped flecks in the breast of a duck, usually found when a duck is skinned instead of picked. It is a protozoan parasite, Sarcocystis releyi, that invades the skeletal musculature of the duck. The tissue most commonly affected is the breast muscle of the bird. These same parasites may invade muscles of the tongue, heart, diaphragm and esophagus of other animals such as horses, cattle, pigs, goats, mice and rabbits.

In most animals the parasite appears harmless, and unless the infection is mas- DECEMBER 1975 tract. The normal activity of these muscles may be reduced to such an extent that adequate digestion and assimilation of food are seriously impaired. Lead poisoning is the name given to the pathogenical conditions that result.

External symptoms that are common in ducks dying from lead poisoningare visible "keel breast" and green-stained vent. A bird may only weigh about 40 to 50 percent of its original weight before it dies.

Factors influencing the frequency and magnitude of lead poisoning outbreaks are: (1) Number (Continued on page 46)

Pheasant Experience

When four Texans came up to hunt ring necks it was a first for most of us. They hadn't hunted our birds and we hadn't been around many nonresidents, so we learned by experience

photos by Faye MusilA BIG COCK burst out of the dense cover and arched to a peak, the sun bringing out the iridescence of his plumage. Then he set his wings and glided across the row of six hunters like a bomber.

Six shots were fired, but not one of them disturbed a single feather. No one said much about the misses.

It was opening day of the 1974 pheasant season, and although that was not our first bird of the day, he wasn't spooky yet. The roosters would get more cautious as the season wore on.

Four of the hunters, Bill Colhour, John Coburn, Jerry Smith and Wayne McDonald were Texans, hunting the wild Nebraska roosters for the first time. The other two, Jack Fountaine and Don Jones, were providing dogs and guide service for the non-residents. Don's son Ken, was also along.

We had started out that morning like some cur dogs, circling cautiously and "sizing up" each other. The four Texans were total strangers to us, except for telephone conversations over the previous few weeks, and they had no idea what to expect of us as hosts.

The hunt was set up in the most circuitous way possibly —an old friend of a friend of a business associate had moved to Texas. He wanted to bring three or four friends to Nebraska to hunt pheasant. It would also be his first experience with really wild birds, he said.

As an employee of the Game and Parks Commission, it was important to me that they be safe, ethical hunters, and as the granddaughter of the landowner, I also worried that they might not respect property. I had heard a lot of bad publicity about non-resident hunters from a number of sources, so I was skeptical.

I began to relax at about 15 minutes before sunrise when I overheard the men talking among themselves. Jerry Smith was remarking that shooting hours had begun, and Wayne McDonald said the field we had selected to start with was a likely looking spot. Then Bill commented quietly that he for one couldn't see well enough to tell a hen from a rooster. The other three agreed.

They stood around a few more minutes stomping their feet and trying to pump around some warming blood. Their early morning weather check at the motel had not prepared them for the bitter wind when getting out of the sheltering trees. The atmosphere in the family farmyard, too, had been mild behind the protection of a mature shelterbelt.

I grinned at the fragments of conversation I could hear from the Texans on someone's foresight in planting

36 NEBRASKAland DECEMBER 1975 37

trees, and on the surprising bite of this "northern" chill.

The morning was a disappointing shade of dull gray that promised no respite from the breeze.

As we started into the tangle of smartweed and grass, I reflected on the near uselessness of the 10-acre plot for crop growing. In a wet year, It was full of standing water or ooze for months at a time. This November it was near prime-thick and wild with weeds, and bordering on sorghum.

There should be pheasants, I reflected, and I'd sure like to show our guests that Nebraska has some good pheasant hunting.

Just a few steps into the tangle, my suspicions were confirmed. Pheasants began getting up right and left, mostly cocks. Three shots downed one of them to Jerry Smith's credit. All four of the men seemed a bit startled.

"This is more like shooting quail!" somebody yelped.

"Naw," Jack corrected. "We just got 'em off the roost. Chances are you'll never see 'em get up in a bunch like that again."

Some 15 to 20 pheasants flew out of the brush, and it seemed that they were all cocks. By the time we'd crossed the plot, I was as amazed as my guests. They had remained cool, though, and once I had heard someone yell; "Hen!" and no one fired.

On my own part, I was surprised that anyone had gotten off a shot at all. I was having trouble walking, let alone shooting. The dogs, too, were working hard just to penetrate the cover. "Great," I noted, to no one in particular.

We crossed a fence into a pasture where we had our herd grazing. Cover there was sparce and birds even sparcer. We flushed one out of an old, silted creek bottom. Returning through an ungrazed grass patch and the sorghum, we found another bird, but neither was bagged.

As the one bird we jumped settled at the roadside, a local vehicle approached and stopped. Passengers began to pile out to take advantage of the Texans' legwork.

"That takes some nerve," Wayne muttered.

My mother, who lives on the quarter we were hunting and had stayed with the vehicle, began driving down to intercept, though, and the intruders left.

When the hunters rendezvoused with the vehicle, mom had a few remarks saved about local hunters. "You know," she said, "in all the years I've been on this land, it's always seemed like the non-resident hunter has been the most courteous. They almost always ask permission. They are careful of livestock, they leave gates as they found them...I suppose lots of people would disagree with me, but I think the local hunters are the problem. I've seen local cars parked along my boundary fences, and I've seen hunters coming out of my croplands —men who have never contacted me.

"I'll let anyone hunt if he'll just ask — but I'm more inclined to save the privilege on a given day for someone I know."

We sampled hot coffee and deer jerky that Jerry had made the previous winter. Everyone agreed it was designed to "warm your innards" effectively.

Next the men crossed the county road and climbed a hill to a shelterbelt where they had seen some of the birds they had flushed settle. One pheasant got up from there. Crossing to a grass and weed-covered waterway, wide enough for only three or four men to hunt, Wayne and John Coburn followed along it with Don and Jack and their dogs. Two birds went into the bag there.

From there we piled into Wayne's crew-cab pickup and returned to the house. We walked west through a shelterbelt there, and crossed the pasture to our original starting point. That's where the sun began breaking through —and where we found the rooster that made such a spectacular show.

We returned again to the house for a chili lunch, then climbed immediately into the pickup without the customary rest. We drove to another farm —saving some of the best acres for later in the weekend. We all had a chance to rest as we moved to land owned by a family friend. A phone call the previous day had confirmed the party's permission to hunt there, as the owner lives in another county.

After walking some pasture and milo stubble, we had just about concluded that the only action we would see would be walking. Then a small covey of quail got up from a brushy creek bottom. Wayne's snap shot was unproductive.

Crossing a fence into unpastured grass, we flushed two pheasants, one of which went into the bag.

Meanwhile, the second half of the party had split off, finished walking a grove of trees, and found a bale pile facing into the sun which they found was a perfect resting place for themselves and the dogs.

Another short ride brought us to a third farm where a quarter-mile, tree-lined tract produced one hen (and a near mistake) along with a rooster.

Driving along the perimeter of the farm, one of the men spotted a cock along the fencerow near the road. Pulling into the deserted farmyard, we all piled out, figuring the rooster would be gone. Forming up, the group began walking. The Labs flushed two cocks. One was a solid hit that Colhour claimed as his first for the day, and the other was crippled.

The second bird came down on the far side of a woven fence, and by the time the dogs crossed, he had disappeared. A 45-minute search by all seven men and the dogs wasn't enough to locate him.

We walked miles and miles of marginal farmland that day, and managed to bag an even dozen pheasant cocks between the seven hunters. I believe my mother and I enjoyed sharing our land as much as the Texans did.

By the time the fog and clouds had burned off, the crisp odor of dry fencerows mingled with bright sunlight gleaming on orange caps and vests, and glinting blue from the dogs' coats. Bill Col hour, stroking the feathers of his first bird of the day, remarked on their iridescent brilliance.

The hunters were, without knowing it, repeating the experience of many hunters in the south-central Nebraska area. Throughout the season, hunters reported seeing plenty of birds, but the wily pheasants were flushing wild and not many were taken.

Evening was time for celebration, as each of the hunters had bagged at least one bird. With the birds that dog trainers Jack and Don had given them, the quartet was carrying limits.

Mom and dad and I were promptly invited to dinner at the local "nightclub". Some talk of dancing before the feast revolved around invention of a dance —the "new jerk" —which was sure to develop whenever anyone moved a walk-weary muscle.

The second day's hunting took the party into a three-acre game preserve planted in the early 1950s. The fences have since deteriorated, along with the government programs that helped place them.

The cedars and plum still harbor wildlife, though, and the men found both pheasant and quail there, but they bagged nothing.

"First hunt of the season," someone muttered darkly.

Three days' hunting produced possession limits for all four men to take back with them to Texas. It also produced a friendship that may bring them back to Nebraska next year. In addition, it brought respect for the Nebraska ringneck which "sure looks like it ought to be easy enough to hit, but I'm sure wasting plenty of shells."

When offers of payment for land use were ignored, Bill Colhour tried another tack. "How about going deep-sea fishing with us in the Gulf?" Then some ears almost visibly pricked up. The result was immediate planning for a trip that may or may not take place.

It seems to get more difficult every year to find hunting land, but good experiences with hunters this year will encourage the landowner to open his property next.

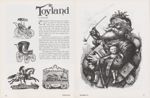

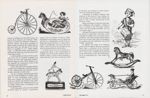

Toyland

COMPARED TO the oppulent array of playthings available to American children today, these wood and iron toys seem sadly primitive by comparison. Yet, to a child of the late 19th Century, growing up when the industrial revolution first spawned the toy industry, possession of even a few such finely crafted toys must have seemed like a dream come true.

More than just artifacts from a vanished era, the toys pictured here represent a dramatic break from the past for the child of American working-class parents. Not only did machine manufacture lower the price of quality toys, heretofore affordable only by the wealthy, but their availability was greatly increased with the advent of mail-order houses.

Throughout the 19th Century, the American view of childhood was gradually changing. In colonial America, children were regarded as miniature adults, subject to the same strict code of behavior as their elders. In the stern

As the hardships of colonial America gradually gave way to increased prosperity and security, the strict rules governing children's behavior began to relax. While diligence was still expected, the importance of play to the child began to be appreciated.

Dress codes reflect this changing attitude; clothing more adequately suited the purposes of play, replacing the stiff, starched, uncomfortable costumes of earlier times.

We see a changing attitude toward childhood also in the emergence of children's literature. In 1819, Washington Irving's Sketch Book gave children the immortal characters of Rip Van Winkle and Ichabod Crane. Entertainment, without some underlying moral, was no longer looked upon as damaging to the child's development.

In the long agony of the Civil War and the profound shock of Lincoln's assassination, America lost its national innocence. Childhood began to be looked upon by adults less and less as a disagreeable period to be endured, and more and more as a magic time, a world of wonderment, discovery and innocence, a term of years to be guarded from too early an encroachment by harsh reality.

In 1865 came Alice In Wonderland, a revolutionary book in the emancipation of children. For the first time, children were al lowed to enter a world of sheer nonsense, a world educators had long warned was ruled

A flowering of children's literature soon followed. In the works of Twain, Kipling, Alcott and others, the natural child, replete with faults as well as virtues, had become, for the first time, a hero.

Adults even began to look back upon their own childhoods with nostalgia; a feeling of loss is conveyed in the 1903 song, Toyland: "Once you have passed its borders, you can never return again."

Although the industrial revolution brought the horrors of child labor to the poor, it also enlarged the middle class, its income and expectations. And while machines freed workers from much manual labor, they also brought to the working man the traditional curse of the wealthy: materialism.

By degrees, the image of St. Nicholas, patron saint of children, became corrupted to Santa Claus, a whimsical, fat elf. Toys from this period in American history seem somehow sad as well as gay —symbolizing not only the luxury and leisure of a new age, but the dawning of an enslavement by a new master, the machine.

...a Big Bicentennial Travelgram

Sprawling over 3,000 acres of wooded bluffs on the

Missouri River, Indian Cave State Park boasts ex-

cellent primitive camping, picnicking, hiking and

exploring. The flora is among the most varied in the

state. History buffs delight in the St. Deroin Ceme-

tery, and the cave.

INDIAN CAVE

STATE PARK

your Independent

Insurance gent

SERVES YOU FIRST

...this message brought to you by the

NEBRASKA ASSOCIATION OF

INDEPENDENT INSURANCE AGENTS

4 miles east,

1/2 mile south

on north side

Platte River

Lewellen, Nebr.

in Garden County

GOOSE PITS

George 0. Rishling, Manager

Write

236 No. Chadron, Chadron, Nebr. 69337

Or Call

Oregon Trail Motel, (308) 778-5566

or (308) 778-5611 Lewellen, NE

Browning

Our EXCLUSIVE DISCOUNT PLAN on all

BROWNING products will save you up to 20%.

This includes guns, ammunition, archery, cloth-

ing, boots, tents, gun cases, rifle scopes and fish-

ing equipment. Inquire ... it will save you $$$.

Big discounts on other sporting goods.

OPEN 7 DAYS A WEEK

Weekdays and Saturdays- 9:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m.

Sunday - 1:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m.

Phone: (402) 643-3303

P.O. Box 243 - Seward, Nebraska 68434

LIVE-CATCH ALL-PURPOSE TRAPS

rhetor

FREE

CATALOG

Low $4.95

Traps without injury squirrels, chipmunks, rabbits mink, fox, rac-

coons, stray animals, pests, etc. Sizes for every need. Also trap, for

•nakes, sparrows, pigeons, crabs, turtles, quail, etc. Save on our low

factory prices. Send no money. Free catalog and trapping secrets.

MUSTANG MFG. CO., Ot. N-34, Box 10880, Houston, Tex. 77011

FORT KEARNEY MUSEUM

TAXIDERMY STUDIO

TO KEARMEV

FORT KEARNEY

MUSEUM

Specializing in birds,

animals, game heads,

fish.

Licensed Professional Taxidermists

Only latest museum methods used.

Phone: (308) 234-5200.

KEARNEY, NEBRASKA

...a Big Bicentennial Travelgram

Sprawling over 3,000 acres of wooded bluffs on the

Missouri River, Indian Cave State Park boasts ex-

cellent primitive camping, picnicking, hiking and

exploring. The flora is among the most varied in the

state. History buffs delight in the St. Deroin Ceme-

tery, and the cave.

INDIAN CAVE

STATE PARK

your Independent

Insurance gent

SERVES YOU FIRST

...this message brought to you by the

NEBRASKA ASSOCIATION OF

INDEPENDENT INSURANCE AGENTS

4 miles east,

1/2 mile south

on north side

Platte River

Lewellen, Nebr.

in Garden County

GOOSE PITS

George 0. Rishling, Manager

Write

236 No. Chadron, Chadron, Nebr. 69337

Or Call

Oregon Trail Motel, (308) 778-5566

or (308) 778-5611 Lewellen, NE

Browning

Our EXCLUSIVE DISCOUNT PLAN on all

BROWNING products will save you up to 20%.

This includes guns, ammunition, archery, cloth-

ing, boots, tents, gun cases, rifle scopes and fish-

ing equipment. Inquire ... it will save you $$$.

Big discounts on other sporting goods.

OPEN 7 DAYS A WEEK

Weekdays and Saturdays- 9:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m.

Sunday - 1:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m.

Phone: (402) 643-3303

P.O. Box 243 - Seward, Nebraska 68434

LIVE-CATCH ALL-PURPOSE TRAPS

rhetor

FREE

CATALOG

Low $4.95

Traps without injury squirrels, chipmunks, rabbits mink, fox, rac-

coons, stray animals, pests, etc. Sizes for every need. Also trap, for

•nakes, sparrows, pigeons, crabs, turtles, quail, etc. Save on our low

factory prices. Send no money. Free catalog and trapping secrets.

MUSTANG MFG. CO., Ot. N-34, Box 10880, Houston, Tex. 77011

FORT KEARNEY MUSEUM

TAXIDERMY STUDIO

TO KEARMEV

FORT KEARNEY

MUSEUM

Specializing in birds,

animals, game heads,

fish.

Licensed Professional Taxidermists

Only latest museum methods used.

Phone: (308) 234-5200.

KEARNEY, NEBRASKA

WILDLIFE DISEASES

(Continued from page 35)of birds using the area; (2) Amount of lead shot present as a result of hunting pres sure; (3) Availability of shot within the habitat (bottom condition); (4) Feeding habits; and (5) Type and amount of feed available.

Avian tuberculosis has shown up peri odically in wild turkeys from the Pine Ridge area. The disease has been verified several times after hunters noticed ab normal livers when field dressing the bird, and contacted Game Commission person nel. Internal signs of avian tuberculosis are usually obvious, especially in advanced stages, with the liver and spleen having lesions that take the form of deep uclers filled with caseous material.

Precaution should be taken when han dling a bird suspected of having tubercu losis, since man is susceptible to the avian strain. If an abnormal liver is noticed when field dressing the bird, the liver, and if possible the whole bird, should be placed in double plastic bags and turned over to the Game Commission for positive identi fication. Precaution should be taken to cleanse and disinfect the hands after han dling the bird, and the meat should be properly disposed of.

Rabbit hunters should be particularly careful in cleaning and handling their game. Probably their most important con sideration is tularemia. This is a disease primarily of rabbits and rodents, and is caused by a bacteria. It is transmitted by mites, ticks, flies, fleas, mosquitoes and lice. The rabbit tick is the chief arthropod vector of tularemia in the wild, and the disease is spread from rabbit to rabbit, principally by the tick. Two other ticks,

Rabbit hunters should use extreme caution in handling, skinning and cooking the animals. Contact should be avoided with rabbits that are possibly infected. Rubber gloves are recommended, if used properly, along with a thorough cleansing and disinfection of the hands. Any cuts and scratches should be painted with iodine. Thorough cooking of the meat will render it harmless, but if lesions are noticed in a rabbit being cleaned, it should be properly disposed of.

Another very common mistake that many rabbit hunters make when cleaning their game is not properly disposing of the entrails. Many times they are fed to the family dog or cat, and even to a prized hunting dog. This should definitely never be done since the chance of tapeworm or other parasitic infection is very great.

Rabbit hunters may also encounter "wormy" rabbits. In dressing a rabbit for the table, one or more large bumps may occasionally be found under the skin. These warbles are the grub or larvae of flies which infect certain mammals. The warble and any local inflammation can be trimmed off when dressing the rabbit and there is no danger of eating the meat, but it should be thoroughly cooked.

Larger animals such as deer are also