NEBRASKAland

November 1975

NEBRASKAland

VOL. 53/NO. 11 /NOVEMBER 1975 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Fifty cents per copy. Subscription rates $5 for one year, $9 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Single Copy Price: 50 cents commission Chairman: jack D. Obbink, Lincoln Southeast District (402) 488-3862 Vice Chairman: Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 2nd Vice Chairman: Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-Central District, (308) 745-1694 Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-central District, (308) 452-3800 H. B. "Tod" Kuntzelman, North Platte Southwest District, (308) 532-2982 Director: Willard R. Barbee Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, Jr. Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree Staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: Jon Farrar Greg Beaumont, Ken Bouc Contributing Editors: Bob Grier Faye Musil, Tim Hergenrader, Roland Hoffmann, Bill Janssen, Ben Schole Art Director: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1975. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska Contents FEATURES RIVER-BOTTOM BUCKS FISHY HAPPENINGS HERITAGE COMES ALIVE MALLARDS AT A DISTANCE FISHING PADDLEFISH SNAGGING THE PERSISTENT COYOTE THE TRIANGLE DRESSING BIG GAME 8 12 14 18 26 28 36 38 DEPARTMENTS SPEAK UP. TRADING POST 49 COVER: Time puts its mark on the sands, and also removes them in the eternal flux that is measured by man only briefly. This is one of thousands of dunes in the Sand Hills. Photo by Lou Ell.

Speak up

Camping ChangesSir / The 4th of July weekend is now his tory at Lake Colorado, formerly known as Lake McConaughy, and I would like to suggest some things to the Game and Parks Commission that may help the area around the lake.

First, I believe that everyone who uses the public camping areas, such as Omaha Beach, Otter Creek, etc., should be as sessed an annual fee, say $5 per recrea tion vehicle. This money then stays at Lake McConaughy and can be used for the following purposes: (1) to buy lime for the outdoor toilets; (2) to construct out door toilets at the public areas; (3) to construct additional boat ramps at the public-use areas; (4) to hire part-time or weekend help at the public boat ramps to direct traffic; and (5) add additional wardens to the lake.

The lake area is a small city on week ends and a large city during summer holi days. I've seen people with over-limits of fish, fast moving boats passing over and cutting fishing lines, skiers buzzing fish ing boats, beer cans in the lake and on shore, garbage on the ground at the publ ic use areas, fist fights at the boat ramps, and at times, too many people. Motorcycles should be outlawed, and here, a few bad ones, the hill climbers, are destroying the vegetation and creating a bad image for all cyclists.

Lake McConaughy is a beautiful lake, but the users of the area will destroy it un less use is controlled.

Corwin Arndt Maxwell, NebraskaIn response to the suggestions offered, I wish to point out that a Legislative Bill establishing a permit to enter State Park areas for a fee was reviewed by the Legis lature in 1973. The bill was defeated. In addition, Section 81-812.02 R.S.N, es tablished a recreation ground sticker fee in 1957 as an income producing tool. There was considerable negative public reaction to this sticker fee of $1 and it proved of little value.

I do not believe that a park entrance fee system is the best way to obtain the sorely needed funds at this time. Some factors to be considered include that costs of collec tion and enforcement of user fees amount to perhaps 40 percent or more of the amount collected, thus as a fund-raising device, they are inefficient.

Also, since colonial times, entrance into various public parks have been free, with charges being made only for special service, and any such fees violate the long-standing concept that entrance should be free.

As most units of the park system are without resident personnel, an entrance fee would likely be directed toward im proved operations and maintenance, and no significant capital improvement.

Most public fishing and much hunting is done on state recreation areas. An en trance fee would thus result in hunters and fishermen paying twice.

Nebraska is operating a good park sys tem. There are some serious deficiencies, including a steadily decreasing capability to manage some areas at the level the public desires. I seriously doubt if in creased funding for future operations can come from the general fund source alone. It may be that such funds will have to come from some type of "earmarked" public tax.

Dale Bree Assistant Director Organic FencesSir / Long ago, I wondered if conventional wire fences could be replaced with wind rows of wood brush to serve the many fold purpose of livestock control, wildlife promotion, soil improvement, etc., in cluding landscape beautification (to me, a brush heap is less obstrusive than a wire fence).

True, such a fence would take more land surface than does a wire fence. A mile of one-rod-wide windrow takes up a couple of acres whereas the same length of wire fence on cultivated land leaves only V2-acre unused. However, the wind row provides such additional benefits it might well justify itself.

The foundation of a brush windrow is tree branches inserted butt end first, leav ing the twig ends bristling outward. Farm animals dislike entering the windrow head-on. Wherever convenient, the wind row should incorporate trees and other live plants in its structure. Without such growth, they need addition of new brush as old brush deteriorates. I expect our windrows to turn livestock by virtue of their "barrier" effect, they shelter wild creatures, accumulate humus, surely en hance the sport of hunting, reduce the force of wind and rain.

I wish other farmers who have an abun dance of brush would try windrowing instead of burning. I even hope that in novators carry the idea to the point of ad mixing domestic and industrial trash with the brush.

Charles Novak Crete, Nebraska Dumb NumbersSir / What on earth does my Social Secu rity number have to do with a subscription to your magazine, or with any magazine, paper or other publication?

Renewal notices began coming with that very casual little notice at the bottom regarding my SS number —and without even a "please" to soften the impact. This smacks of some of the peremptory arro gance we're being treated to at the hands of the government, and I for one strongly resent it.

You certainly don't need my SS number in order to send me your magazine; all you need is my name and full address, so this whole thing mystifies me and all I can conclude is that you simply want to gather every possible bit of personal information you can and keep it on file for sale at some future time. Perhaps soon now you'll be asking for the name of my bank and the size of my present balance, so you can keep that on file.

E. S. Haddas Chula Vista, Cal.My, aren't we touchy! No, we don't sell subscription lists, but I must admit the Social Security number is only important on very rare occasions; certainly not enough to bug people about. We have since removed the request, and will only ask the number when it is necessary. There was a trend nationally to use the number on all records, thereby reducing the chance to confuse people. Many people, as you may have noticed, have the same or similar names, but there is only sup posed to be one number assigned each human. Now, the use of the number is be coming of less importance, for some rea son, and we certainly are happy to drop our request. (Editor)

NEBRASKAland Magazine invites all readers to submit their comments, sugges tions, and gripes to Speak Up. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters. — Editor.

HUNTERS

Eat and/or

stay overnight

$13.75 per

person per day

J'S OTTER CREEK MARINA

North Side Lake McConaughy

Open 4:30 a.m. till 7 p.m. daily

Hunting permits, Ammunition,

General Hunting Supplies

Phone LEYMOYNE (308) 355-2341

P.O. LEWELLEN, NEBR. 69147

Jay & Julie Peterson

Every trip doesn't have

to be a hunting trip

Why shoot your fun searching

for a pleasant place to stay?

Phone ahead before you go.

THE LINCOLN TELEPHONE CO.

WATER POLLUTION CONTROL

Blue Ribbon

CONTRACTING

ST. PAUL, NEBR.

REMOVE:

SEDIMENTATION

MUCK

WEEDS

SILT

SAND

SLUDGE

INDUSTRIAL WASTE

HYDRAULIC FILLS

NO JOB TOO LARGE OR SMALL

381-1223

GRAND ISLAND

BIDS-

GIVEN

754-5211

ST PAUL

ST

PAUL

FORT KEARNEY MUSEUM

TAXIDERMY STUDIO

TO KEARNEY

FORT

ORT KEARNEY

MUSEUM

BLOCK

Specializing in birds,

animals, game heads,

fish.

Licensed Professional Taxidermists.

Only latest museum methods used.

Phone: (308) 234-5200.

KEARNEY, NEBRASKA

NEW INVENTION FOR FISHERMEN

The SENTRY ROD HOLDER®

DESIGNED FOR SUMMER...WINTER ICE FISHING

Feather-Lite Release - 5 Select Positions

No Fumbling-Drag-or Whip-Lash or Tangled

Lines Holds Rod From Turning and Swaying In

The Wind • Give As A Gift Every Fishermens

Rod Should Have One 30 Day Refund Guarantee

Dealers Inquiry Invited.

SEND $1.98 PLUS 25? EACH FOR SHIPPING COST

CHECK OR M.O. ONLY TO

SENTRY ROD HOLDER BOX 3885 OMAHA, NE. 68108

"FISH

ING

MADE

EASY"

AUTHORS WANTED BY

NEW YORK PUBLISHER

Leading book publisher seeks manuscripts of all

types: fiction, non-fiction, poetry, scholarly and

juvenile works, etc. New authors welcomed. For

complete information, send for free booklet R-70.

Vantage Press, 516 W. 34 St., New York 10001

4 miles east,

1/2 mile south

on north side

Platte River

Lewellen, Nebr.

in Garden County

GOOSE PITS

George O. Rishling, Manager

Write

236 No. Chadron, Chadron, Nebr. 69337

Or Call

Oregon Trail Motel, (308) 778-5566

or (308) 778-5611 Lewellen, NE

NEBRASKAland

WESTERN CHRISTMAS CARDS

The Breathtaking Beauty of the Outdoor West

REALISTIC FINE ART REPRODUCTIONS

You and your friends will treasure these fine quality 5" x 7" cards.

Featuring colorful reproductions of paintings by America's foremost

western and outdoor artists. Greetings thoughtfully matched to designs.

We can imprint your name inside in red, also your address on the bright

white envelopes. FAST, IMMEDIATE shipment now 'til Christmas.

OUR 26TH YEAR OF HAPPY CUSTOMERS BY MAIL

ORDER FROM THIS AD OR SEND FOR FREE SAMPLE AND CATALOG

1033 A Cowboy's Christmas- ..good prospects ain't

a half inch high... but Merry Christmas same as ever!

3023 Covey of Quail-This time of year...What

could be better than to wish Merry Christmas, etc.

3018 Confrontation in the Corn- Holiday Greetings 1092 Cowboy's Prayer "I ain't good at prayin'.

and Best Wishes for the New Year - Peace and Good Will at Christmas, etc.

1139 "Christmas a-comin'. Purt near broke..." 3050 The Star That Stayed Til Morning- May the

- But we... hope you're doin' as good---or better! Peace and Joy of Christmas be with you, etc.

a prayer at Christmas lime

1095 Bringin'Them Home- ...What could be better 1135 "This brings a prayer at Christmas..."- That 1140 The Wonder of Christmas- May Christmas 1161 "Let us keep Christmas...its meaning never

...than to wish Merry Christmas to all that we know! God will bless...those you love with lasting happiness bring Friends to your Fireside, Peace...Health, etc. ends, etc."- Merry Christmas and Happy New Year

beams

1212 "We are thinking of you..."- ...good will to

you is what we mean in...The Spirit of Christmas

1164 "...Christ's humble birth, the love of friend

for friend."- Merry Christmas and Happy New Year

1142 Christmas Morning Handout- ...Never too

deep the snow, To wish the Merriest Christmas, etc.

3022 "...the bird of the fields, etc"- Happy

Holidays and Best Wishes for the Coming Year

1151 "...the fair, and open face of heaven..."

- May every happiness be yours at Christmas, etc.

1137 "Britches patched. Vittles skeerce..."- Both

horses lame, But Merry Christmas just the same!

58 "May the Great Spirit watch over you, etc."

Merry Christmas and Happy New Year

HOW TO ORDER: Use coupon or letter and

mail with payment. Order all of one kind

or as many of each as desired. Include fee

for postage and handling in total payment.

Colorado residents add 3% sales tax. Cali-

fornia residents add 6% use tax. Canadian

customs duty charged at border. No CO. D.

Postage and Handling Fee

Orders to $8.00 add 70C

$8.01 to $18.00 add 90C

$18 01 and up add $1.00

1220 Bicentennial- At Christmas comes this wish

...may 1976 overflow with health, happiness, etc.

Quan. of Without

cards name

and envs. imprinted

With

name

imprinted

Name AND Extra for

brand OR address on

brand only env. flaps

12 $ 2.85

25 4.95

37 7.45

50 9 90

75 14.60

100 18.80

125 23.25

150 27.70

200 36.60

300 54 40

500 88.50

$4.

6.

9.

12.

17.

21

26

30

40

59

95

35

70

45

15

10

55

25

95

35

15

25

$6.10

8.45

11.30

13.90

18.85

23.30

28.00

32.70

42.10

60.90

97.00

175

2.00

2.25

2.50

2.75

3.00

3.25

3.50

4.00

5.00

7.00

Fill in quantity desired of each card number at right. Mix and assort at no extra cost. 1033 1139 1161 3018

1092 1140 1164 3022

1095 1142 1212 3023

1135 1151 1220 3050

1137 1158 Total Cards Ordered

To order envelopes imprinted, check here. See price list for additional cost. Total Payment Enclosed

NAMES TO BE PRINTED ON CHRISTMAS

CARDS (ENCLOSE DRAWING OF BRAND)

SEND CARDS

AND/OR CATALOG TO:

R-NT26

Rte.. St., or Box No.

City

State

Zip

SATISFACTION GUARANTEED OR YOUR MONEY BACK

LEANIN'TREE BOX 150Q-R-NT26, BOULDER, COLORADO 80302

Rush free

sample and

full-color

catalog

LEANIN' TREE

HUNTERS

Eat and/or

stay overnight

$13.75 per

person per day

J'S OTTER CREEK MARINA

North Side Lake McConaughy

Open 4:30 a.m. till 7 p.m. daily

Hunting permits, Ammunition,

General Hunting Supplies

Phone LEYMOYNE (308) 355-2341

P.O. LEWELLEN, NEBR. 69147

Jay & Julie Peterson

Every trip doesn't have

to be a hunting trip

Why shoot your fun searching

for a pleasant place to stay?

Phone ahead before you go.

THE LINCOLN TELEPHONE CO.

WATER POLLUTION CONTROL

Blue Ribbon

CONTRACTING

ST. PAUL, NEBR.

REMOVE:

SEDIMENTATION

MUCK

WEEDS

SILT

SAND

SLUDGE

INDUSTRIAL WASTE

HYDRAULIC FILLS

NO JOB TOO LARGE OR SMALL

381-1223

GRAND ISLAND

BIDS-

GIVEN

754-5211

ST PAUL

ST

PAUL

FORT KEARNEY MUSEUM

TAXIDERMY STUDIO

TO KEARNEY

FORT

ORT KEARNEY

MUSEUM

BLOCK

Specializing in birds,

animals, game heads,

fish.

Licensed Professional Taxidermists.

Only latest museum methods used.

Phone: (308) 234-5200.

KEARNEY, NEBRASKA

NEW INVENTION FOR FISHERMEN

The SENTRY ROD HOLDER®

DESIGNED FOR SUMMER...WINTER ICE FISHING

Feather-Lite Release - 5 Select Positions

No Fumbling-Drag-or Whip-Lash or Tangled

Lines Holds Rod From Turning and Swaying In

The Wind • Give As A Gift Every Fishermens

Rod Should Have One 30 Day Refund Guarantee

Dealers Inquiry Invited.

SEND $1.98 PLUS 25? EACH FOR SHIPPING COST

CHECK OR M.O. ONLY TO

SENTRY ROD HOLDER BOX 3885 OMAHA, NE. 68108

"FISH

ING

MADE

EASY"

AUTHORS WANTED BY

NEW YORK PUBLISHER

Leading book publisher seeks manuscripts of all

types: fiction, non-fiction, poetry, scholarly and

juvenile works, etc. New authors welcomed. For

complete information, send for free booklet R-70.

Vantage Press, 516 W. 34 St., New York 10001

4 miles east,

1/2 mile south

on north side

Platte River

Lewellen, Nebr.

in Garden County

GOOSE PITS

George O. Rishling, Manager

Write

236 No. Chadron, Chadron, Nebr. 69337

Or Call

Oregon Trail Motel, (308) 778-5566

or (308) 778-5611 Lewellen, NE

NEBRASKAland

WESTERN CHRISTMAS CARDS

The Breathtaking Beauty of the Outdoor West

REALISTIC FINE ART REPRODUCTIONS

You and your friends will treasure these fine quality 5" x 7" cards.

Featuring colorful reproductions of paintings by America's foremost

western and outdoor artists. Greetings thoughtfully matched to designs.

We can imprint your name inside in red, also your address on the bright

white envelopes. FAST, IMMEDIATE shipment now 'til Christmas.

OUR 26TH YEAR OF HAPPY CUSTOMERS BY MAIL

ORDER FROM THIS AD OR SEND FOR FREE SAMPLE AND CATALOG

1033 A Cowboy's Christmas- ..good prospects ain't

a half inch high... but Merry Christmas same as ever!

3023 Covey of Quail-This time of year...What

could be better than to wish Merry Christmas, etc.

3018 Confrontation in the Corn- Holiday Greetings 1092 Cowboy's Prayer "I ain't good at prayin'.

and Best Wishes for the New Year - Peace and Good Will at Christmas, etc.

1139 "Christmas a-comin'. Purt near broke..." 3050 The Star That Stayed Til Morning- May the

- But we... hope you're doin' as good---or better! Peace and Joy of Christmas be with you, etc.

a prayer at Christmas lime

1095 Bringin'Them Home- ...What could be better 1135 "This brings a prayer at Christmas..."- That 1140 The Wonder of Christmas- May Christmas 1161 "Let us keep Christmas...its meaning never

...than to wish Merry Christmas to all that we know! God will bless...those you love with lasting happiness bring Friends to your Fireside, Peace...Health, etc. ends, etc."- Merry Christmas and Happy New Year

beams

1212 "We are thinking of you..."- ...good will to

you is what we mean in...The Spirit of Christmas

1164 "...Christ's humble birth, the love of friend

for friend."- Merry Christmas and Happy New Year

1142 Christmas Morning Handout- ...Never too

deep the snow, To wish the Merriest Christmas, etc.

3022 "...the bird of the fields, etc"- Happy

Holidays and Best Wishes for the Coming Year

1151 "...the fair, and open face of heaven..."

- May every happiness be yours at Christmas, etc.

1137 "Britches patched. Vittles skeerce..."- Both

horses lame, But Merry Christmas just the same!

58 "May the Great Spirit watch over you, etc."

Merry Christmas and Happy New Year

HOW TO ORDER: Use coupon or letter and

mail with payment. Order all of one kind

or as many of each as desired. Include fee

for postage and handling in total payment.

Colorado residents add 3% sales tax. Cali-

fornia residents add 6% use tax. Canadian

customs duty charged at border. No CO. D.

Postage and Handling Fee

Orders to $8.00 add 70C

$8.01 to $18.00 add 90C

$18 01 and up add $1.00

1220 Bicentennial- At Christmas comes this wish

...may 1976 overflow with health, happiness, etc.

Quan. of Without

cards name

and envs. imprinted

With

name

imprinted

Name AND Extra for

brand OR address on

brand only env. flaps

12 $ 2.85

25 4.95

37 7.45

50 9 90

75 14.60

100 18.80

125 23.25

150 27.70

200 36.60

300 54 40

500 88.50

$4.

6.

9.

12.

17.

21

26

30

40

59

95

35

70

45

15

10

55

25

95

35

15

25

$6.10

8.45

11.30

13.90

18.85

23.30

28.00

32.70

42.10

60.90

97.00

175

2.00

2.25

2.50

2.75

3.00

3.25

3.50

4.00

5.00

7.00

Fill in quantity desired of each card number at right. Mix and assort at no extra cost. 1033 1139 1161 3018

1092 1140 1164 3022

1095 1142 1212 3023

1135 1151 1220 3050

1137 1158 Total Cards Ordered

To order envelopes imprinted, check here. See price list for additional cost. Total Payment Enclosed

NAMES TO BE PRINTED ON CHRISTMAS

CARDS (ENCLOSE DRAWING OF BRAND)

SEND CARDS

AND/OR CATALOG TO:

R-NT26

Rte.. St., or Box No.

City

State

Zip

SATISFACTION GUARANTEED OR YOUR MONEY BACK

LEANIN'TREE BOX 150Q-R-NT26, BOULDER, COLORADO 80302

Rush free

sample and

full-color

catalog

LEANIN' TREE

RIVER-BOTTOM BUCKS

IT WAS ONLY 30 minutes into the 1973 Nebraska deer season. I had just finished field dressing my five-point whitetail and was toasting a cold sandwich over a fire of Cottonwood twigs. I heard a noise and glanced up just as a three-point buck walked out from behind a cedar, 20 yards beyond the fire. The sight of an orange-clad hunter and curling smoke seemed to confuse the buck more than frighten him. Instead of bounding off in the opposite direction, he took two steps closer and tested the air. At 15 paces we eyed each other with far more calm than most bucks and hunters do on the opening morning of deer season. Satisfied that I didn't belong, but still unsure of what I was, he trotted off 40 yards and then paused to look again. During the next 20 minutes he left a maze of fox-and goose trails in the new snow, never once going farther than 75 yards away from me, but never once letting a tree come between us.

One of my hunting companions was in a tree stand only a quarter of a mile south. I was hoping that he would leave his post early to see if I had filled my permit with my two earlier shots. I heard a stick snap and slowly pivoted so that I could

point out the buck to him. As I turned I expected to see him coming over the ridge about 40 yards behind me. Instead, I saw a second buck, a twin to the one in front of me, trying to belly crawl between me and the ridge. He chose not to run, but instead continued to creep along as if I weren't looking at him.

Twenty minutes before I had heard two shots*from the direction the buck was creeping. Maybe he was hit. I decided to check for blood. I barely had my legs stretched out when he did the same and started putting distance between us. He didn't look crippled as he bounded away, but I started over to check his trail anyway. I'd gone about two steps when a third buck, this one a nice 4 pointer, exploded out of a clump of cedars only 80 yards east of me. He wasn't at all interested in belly crawling or investigating a crackling fire.

As I think back on that moment, I can hardly believe it. There I stood, on opening morning of deer season with a respectable 5 pointer at my feet, and within 150 yards another 3 bucks hightailing it out of the country.

That was my tenth year of hunting Nebraska deer and I can't honestly say that that was a typical opener, but for half of those seasons I have filled my buck only tags on the opening day. For the last five years I've worked for the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission and have travelled over most of the state's best deer ranges, but come opening day I still head for the same area I first hunted at 16. With the exception of one year, I've hunted with a brother, an uncle and assorted cousins on the Loup River in east central Nebraska, less than a mile from my hometown of Monroe. Deer hunting there is sort of a family affair with all the tradition of a Maine hunting camp. Instead of hardwood forests we hunt cornfield riverfront, and chili takes the place of the usual oyster stew.

Deer hunting the Loup River Valley is pretty much like deer hunting any farm land laced with creek and river bottoms. The bulk of the land is planted to corn or milo, but strips of brush and timber between the streams and the fields have provided the versatile whitetail some prime habitat, and he has taken full advantage of it.

The habits of farmland whitetails are influenced by many variables during the fall-the weather, crop harvest and hunter activity —but in general they follow a predictable pattern that the hunter can capitalize on. As soon as it is light, and often slightly before, deer browse their way out of the timber to feed in the cornfields for half an hour to an hour before returning to their day beds in the timber. Most of the time you won't see much of whitetails during the day, unless the weather is starting to turn for the worse and they're busy feeding. With storm fronts moving in, I've found the cornfields loaded with deer. During typical fall NOVEMBER 1975 weather, though, the deer seem to stay holed up in the heaviest brush the river bottoms have to offer. Shortly before sundown they start moving into the grain fields again. It's anybody's guess where they spend the nights —in the fields or back in the woods. Probably they do a little of both depending on the weather.

A lot of farmers tell me that before the corn is picked in the fall, whitetails spend most of their time in the cornfields —bedding there during the day and feeding at leisure. I know one farmer who takes a nice buck almost every year while picking his corn. One of the largest bucks I've ever seen shot in the Monroe area kept moving over a few rows as he picked back and forth across the field. He returned after lunch with his deer rifle and shot the buck bedded in one of the rows.

Because deer use the fields so heavily in the fall, the progress of corn harvest can make a vast difference in hunting success. If the corn is still in during the season, the deer kill can nosedive. Cornfields are nearly impossible to hunt successfully too dense to post a stand, too noisy to still hunt and too large to drive.

During the 1973 season, though, only about 20 percent of the corn was still standing on opening day and it had all the makings of a good year.

I was hunting with my brother Tom, a body-shop foreman in Norfolk; cousin Gary Ziegler, a propane dealer in Monroe; and my 16-year-old cousin Kathy Schmidt. It was Kathy's first year of deer hunting, so her father Ralph was tagging along to teach her the ropes. Ralph usually hunts with us, but his number hadn't been pulled in the drawing that year. Tom, Gary and I had all drawn permits for the Elkhorn Management Unit around Monroe. Kathy hadn't been so lucky and was hunting her second choice, Loup East, a unit that started just eight miles west of Monroe.

So, come opening morning, Ralph and Kathy headed west of town to her unit, Tom staked out a cornfield about a mile north of the river, and Gary and I made the mile walk along the river to the area we always hunt. It seemed kind of unusual to have our party spread out this much, but Kathy didn't have any other choice, and Tom thought he had a good chance to ambush a buck in the corn.

A quarter-moon cast enough light on the snow so that Gary and I could pick out the silhouettes of a half-dozen deer on the picked corn as we walked in. Most years I open the season from a stand that overlooks that cornfield and some river-bottom land, but when we spooked those deer I decided to hunt farther back in the timber where the deer would be moving later in the morning. As a rule, I've found that they don't stay out in the open much after the sun makes it over the tops of the (Continued on page 42)

fishy happenings

In this class, grades were earned as students stood in sub-zero cold with homemade tackle standing in frigid water

CRAZY! EVERY ONE of them! There they were, freezing their mitts off, fishing with flies — in January —for trout. A handful of college students was scattered along the banks of Verdigre Creek, each-one whipping flies into the icy-stream and hoping for some poor fool fish to chomp down on his (or her) lure. They could easily have been laughed away ex cept the trout did not think it was very funny. They were not laughing —they were biting.

This seemingly mad adventure was all part of a college course. At Mount Marty College in Yankton, South Da- kota, as in many other colleges, there is a month between semesters called the Interim. During the Interim, stu dents have an opportunity to study areas, academic and otherwise, which are not generally included in the col lege curriculum. The course offerings include everything from dramatic lit- erature to fly fishing.

A dozen students signed up for the course on fly fishing. They were a lively and eager bunch, ready to go fishing every time the mercury bounced up to 10 below zero. But most of them had never been fly fish ing before, and if a field trip was to be successful, they first had to learn the fundamentals of the sport.

They began by learning what a fly line is and how to use a well-bal anced rod to cast that line. To avoid the bad casting habits which plague many beginners and some experts, they learned to cast in the gym under the critical eye of the instructor. As their form and timing developed, they were forced to move to more spacious surroundings —the parking lot.

But there is more to fly fishing than graceful casting. A fly of some type is required, so the students learned how to make flies of all types. Starting with size 4 streamers, they worked down to size 24 midges, and included all kinds of wet flies, dry flies and nymphs in between. The flies they made themselves were the only lures they would have to use on the field trip.

Even casting skill and a tackle box full of flies are not sufficient to make a successful fisherman. Indeed, the intellectual hardware is probably even more important than the physical hardware. The students had to learn to "think like a trout/' So they studied slides of streams in order to spot the places where the fish might be. They listened to countless lectures on the selection of flies, reading rises, stalk ing fish, and what to do if one finally strikes.

After several weeks of work, the students were physically, mentally and emotionally prepared for a fish ing trip. The weather was ready, too, with daytime temperatures in the 40's. The little band of intrepid fishermen gathered in the foggy darkness of a January morning, crossed the river into Nebraska, and headed for Ver digre Creek near Royal.

The stream is spring-fed and flows fast enough that the water is open even on the coldest winter days. The stream is usually well stocked with trout from the nearby hatchery. While most hatchery trout do not know what a fly is and prefer to be caught on cheese, a few survive the bait fisher men and become more wary and more fussy in their eating habits. The main goal of the trip was to learn how to catch thesefew relatively wild trout. It would not be easy. The stream flows through abundant beds of watercress which harbor an ample supply of in sects and Crustacea and provide good cover for the trout.

Casting on the stream was not like casting in the gym. Willow shrubs, trees, and even grasses reached out to snatch at flies and lines. A cruel wind, which always blew from the wrong di rection, dropped otherwise perfect casts in tangled piles on the bank. Each inviting pool concealed immov able snags which cost the novice fish ermen a few flies and a lot of pa tience. But the students adapted to the obstacles, realizing that they gave the fish an even break and were an impor tant parti of the sport. They then turned their attention to catching fish.

The most popular fly with both the fishermen and the fish was the Mud dler Minnow. When it was fished very slowly along cut banks or near brush piles, it looked like a bait fish holding in the current. It was too big, too deli cious and too vulnerable looking for even the most satisfied fish to resist. In the cold water, the rainbows left their cover slowly and struck deliber ately so it was necessary to set the hook with a very firm motion.

It was not easy fishing, for the fish gave no clues about their presence or position. There were no rises to cast to. The few fish that were in the open spooked while still out of casting range. It was difficult, but not impos sible. The greater challenge of winter fishing led to greater satisfaction with success.

As the early darkness of evening began to fall, a cold, hungry and thor oughly fatigued band of fishermen returned home. They had not stuffed their creels with legendary lunkers, but they had learned that a good an gler could give the fish a better-than even break and still catch them. And that's what fly fishing is all about.

NEBRASKAland proudly presents stories of its readers, and welcomes tales of out door recreation, hunting, fishing, or his torical s. If you have a story to submit, mail it to Editor, NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebr. 68503. Send photos, too, if available.

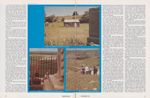

HERITAGE COMES ALIVE

Retracing the route of the Oregon Trail becomes an exciting experience for these school children. An attempt is made to simulate the wagon trains of yore

photos by Lowell JohnsonIN THE SPRING of 1974, a social studies class was set up at Norris Elementary School, aconsolidated school located in southern Lancaster County, with Bob Manley Jr. as its teacher. The class was formed with the premise in mind that: To under stand what and who we are, we shou Id know from where we come, and, that we learn best through experience.

The semester's study began with research of the children's ancestors. Family trees were developed and our mostly European roots were explored. Emigration as a concept was developed; first the emigration to the New World and later, emigration across the new land. We were most interested, of course, in the Oregon Trail; the Great Platte River Road across Nebraska, sinceourstateplayed such a significant historical part in the emigration to the west during the mid 1800s.

The culmination of the semester's study was a trip along this Old West highway across Nebraska, and thus a modern version of a wagon train was formed.

Our purpose was to make heritage come alive for the children; to do something to help people to be able to look at and appreciate all that we have around us; to live the life of the pioneer with responsibilities and work for all, and to better appreciate all which has been done, but constraints of time, finances, and such made this impractical. We finally formed a caravan of two vans, two cars and a trailer.

Loren Wilson, owner and operator of Wilson Outfitters of Lincoln, was called in early for advice since we didn't want to litter the trailside all the way across the state with unwanted items as our forefathers did. Loren worked with the children, helping them plan and learn, and he accompanied us on the trip supplying most of the needed camping equipment and "know how". In his role as sutler of the excursion, Loren added much to the trip for the children. His lead ing of songs, empathy for the home sick, and general good naturedness were felt by all. And, an unexpected bonus, he surprised us all with his historical knowledge.

The trip was financed through a grant from the State Department of Education's ESEA Title III division and by money raised locally by the children. A highlight of this effort for the kids was a program of pioneer singing and dramatizations they did with the help of Dr. Robert Manley, noted Nebraska historian, the father of our staff member.

Just, (well almost) as it must have been in the mid 1800s, spring finally arrived for these latter day emigrants after anxious anticipation and preparation. Our assemblage in the early morning hours of May 27, 1974 surely did in some ways resemble scenes in early Independence, St. Joe or Omaha. The travellers were there, eager but a little scared, and wondering if they'd see the "elephants of the Platte."

Elephants once roamed the Platte River Valley —mammoths and mastodons, that is, which flourished during the Ice Age as recently as 20,000 years ago. To read the diaries of the Gold Rush, one might suppose that elephants flourished also in 1849, but the emigrants weren't talking about woolly mammoths or genuine circus type elephants. They were talking about one particular elephant, the Elephant, an imaginary beast of fear some dimensions which, according to Niles Searls, was "but another name for going to California." But it was more than that. It was the popular symbol of the Great Adventure, all the wonder and the glory and the shivering thrill of the plunge into the ocean of prairie and plains, and the brave assault upon mountains and deserts that were gigantic barriers to California gold. It was the poetic imagery of all the deadly perils that threatened a westering emigrant. Thus, on his first day out of St. Joe in 1852, John Clark wrote: "All hands early up anxious to see the path that leads to the Elephant." In 1849 James D. Lyon, 10 miles east of Fort Lara mie, was defiant: "We are told that the Elephant is in waiting, ready to receive us...if he shows fight or at tempts to stop us on our progress to the golden land, we shall attack him with sword and spear."

No one has quite nailed down the origin of this mythical figure, often more vivid in imagination than the real three-dimensional rattler or buffalo. This creature seldom appeared except on the fringes of danger, and then it was only a fleeting glimpse. During a cattle stampede, says Martha Morgan, "I think I saw the tracks of the big elephant." Excited about his first buffalo chase, David Staples "went out to get a nearer view of the elephant." This phantom appeared most often during violent storms. James Abbey felt "a brush of the elephant's tail," while Niles Searls "had a peep at his proboscis."

"The joys and sorrows, the hazards and heartaches of the covered wagon emigrants were enough to populate a whole continent full of elephants."

And there were those staying be hind there, too, to say goodbye and trying to hide their own apprehensions about the trials of trail life await ing their loved ones. We knew it wasn't really the same, but it did, I think, help the people involved in imagining the thoughts the real pioneers must have felt knowing that everything in the world that they owned was with them as they struck off for several months' travel into the unknown.

May 27: Our first stop was Alcove Springs near Marysville, Kansas. Here, as was to follow at each historic stop, a group of two or three students reviewed with the others the significance of the spot. Others were responsible at each spot to observe and record land formations, plant and animal life, and infer differences now from what it must have been like 125 years ago. In addition, all the children kept diaries of the trip.

Alcove Springs was one of the first big rest stops about three weeks out of Independence for the pioneers, and even though the water no longer spills over the famed rock alcove, the grave of "Grandma Keyes" is there and it is a significant spot.

The first night was spent camping along the banks of the Big Blue River on the Keith Williams ranch, and early the next morning we were off on the second day's journey.

photos by Richard Eisenhauer

photos by Richard Eisenhauer

May 28: The second day, our hardy band moved into Nebraska, stopping over at the Hollenberg, Kansas Pony Express Station, and Jefferson County's Rock Creek Station, Qui vera Park, Steele City, and the site of George Winslow's grave. Much credit is due to the Jefferson County Historical Society for the efforts of several members who gave so much of themselves to our kids during our day-long stay in their county.

The day ended as we moved across the county following the Trail, and into Thayer County to Alexandria where we pitched camp for the second night.

May 29: The third day we journeyed on through the back roads down the Little Blue Valley. And I do mean back roads! This was no Interstate trip! Never were we more than a mile or so from the actual Oregon Trail.

Stops were made this day at the sites of Big Sandy Station, Thompson's Station, Kiowa Station, and a favorite area of the kids, Oak Grove Station and the Narrows near present day Oak and Nora, sites of battles in the famous Indian Wars of 1864. As we sat on a warm spring day on a hilltop overlooking the Narrows and reading aloud an eyewitness account of the Eubanks massacre, more than one imagination saw the Indian raiders coming up along the river, and more than one imagined themselves as Laura Roper being carried off.

Later that day we visited Spring Ranch and then moved on to Fort Kearny for the night, as did most early travellers since it was a fact that all roads led to Kearny.

May 30: Day four began with a stop at the site of infamous Dobytown, the R. & R center for Old Fort Kearny, then into Phelps County to the site of the Plum Creek massacre, another sig nificant Indian encounter site. Then up the Interstate (those guys really knew where to put a road) to Fort McPherson and the site of Old Fort Cottonwood.

Camp that night was at the Maloney Reservoir.

May 31: Day five brought a hike up to Sioux Lookout in Lincoln County and stops at several Oregon Trail markers in the area south of Hershey and Sutherland. Ogallala and Front Street provided good diversions for

June 1: The morning of the sixth day we went on toward the west pausing at the gravesite of Rachael Pattison, one of many of our predecessors who didn't make it. We struck out across Garden and Morrill counties heading for Mud Springs, a Pony Express and trail station. We looked for artifacts from the station and heard about Indian battles there and then proceeded to get stuck in the sand, an event which only increased our appreciation of the time when there were no roads.

Shortly after, into our sight came the panorama of the great landmark rocks. The next stop was Courthouse and Jail Rock. Here we owe another debt of thanks to Paul Henderson and Rev. Spencer of Bridgeport who shared with the children their vast knowledge of the Oregon Trail and their vicinity.

Chimney Rock stirred our group's imagination, and I would guess that the variance in our kids' estimates of its magnitude were just about as great as those referred to in past trail diaries.

The long day ended with our camp at Wildcat Hills south of Scottsbluff.

June 2: Our seventh day out was highlighted by visits to Fort Laramie and Gurnsey, Wyoming where we saw the trail ruts cut into rock, and the famous Register Cliff, where numerous early autographs were left by passersby. Fort Laramie was quite an experience for the kids as the personnel of the Fort dressed, acted and spoke as if it were 100 years earlier.

The seventh night was also spent at Wildcat Hills, making it the only day of the trip when the entire camp and all our belongings weren't packed and moved and reassembled by the 10 and 11 -year-olds.

June 3: Day eight began our way back —the long way. We journeyed from Scottsbluff up to Fort Robinson, leaving the Oregon Trail portion of the trip but feeling that having the children this far west, a visit to Fort Rob was essential since it has been so significant in Nebraska history. Also, I must confess that this particular visit represented a highlight of the trip for the adults —our first showers after seven days of camping and being out doors were more than appreciated. Loren Wilson was counted going for a shower three times. He can supply nearly every convenience for the camper including steam tables and freshly baked birthday cake, but so far, not showers.

Fort Rob was toured completely and the kids enjoyed the jeep and trail rides and especially the chuckwagon dinner.

June 4: On the ninth day we began our trek back across the state, skirting the northern edge of the Sand Hills, and upon reaching Valentine, we made use of Wilson Outfitter Canoes for a trip down the Niobrara River to Smith Falls, scenery matching any vacation area for beauty.

June 5: Travelling through the Sand Hills took a good portion of this day, and arriving at Halsey National Forest in mid afternoon, our kids made good use of the swimming pool. It cooled them off, was of course fun, and what an excellent way to clean them up for their arrival back to their parents!

June 6: Home again! A day's rest, and then back to school for a day of evaluation with the kids. We had to, you see, do more than just assume they'd learned as well as having had a good time, and the results were quite pleasing.

Now then, the usual question: "You actually went out with how many kids?" Thirty nine of us in all — six were adults. "And you're still sane?" Of course! Kids can assume respon sibility and work hard if it's necessary and if it is expected of them. Personally, I can think of few ways of helping children learn self-reliance and responsibility better than camp ing. I recommend it to families for the same purpose. The kids were great. They were organized just as wagon trains were, in companies with their own captains, and so were involved in some decision making, and fully understood the definite jobs that were shared by all on a rotating basis. And they learned! Not only about Nebraska and all in which we need to develop pride, but about themselves. Finally, "Would I do it again?" You bet! And you can, too. It's all right here in Nebraska if we only look.

MALLARDS AT DISTANCE

A long drive west was necessary to get in a duck hunt, and the weather dictated that I go alone. Ducks in droves milled nearby, just out of reach

Photo by Bill McClurgDUCK HUNTERS ARE CRAZY, I thought out loud as I drove in the darkness through the blowing and drifting snow. (Talking to myself even helps substantiate the statement). The interstate was already snow-packed and I had at least a hundred more miles to go to reach Sutherland.

A last minute duck hunt was on my mind, and I had to go to the western half of the state since the season had been closed in the east for nearly a month. Tomorrow was the last day of the season and I had picked the Sutherland area feeling I had a better chance to score because I knew the country from previous hunts.

Curled up on the seat beside me was Whiskers, a black Lab borrowed from my brother-in-law. The dog would be my hunting companion as I couldn't find an other hunter foolhardy enough to make the trip. As they say, "we may be crazy, but we're not stupid."

Passing through North Platte, I stopped at a phone booth and called Joe Hyland, a friend and fellow employee of the Game and Parks Commission stationed at North Platte. He didn't sound encouraging.

"The birds are there," he told me, "but we need a high wind to drive them off the lakes. I went out this morning when it started snowing, but they weren't moving. Most hunters have already given up —the weather has just been too nice."

He suggested that I try either the North or South Platte, as they both had stretches of open water. I decided to try the latter, and a few phone calls to land owners along the river put me in business for the following morning.

The radio said five degrees above zero as my Volkswagen bucked the snowdrifts nearly choking the road to the river. The wind had stopped during the night and the sky was clear. Steam was rising from the water as I set out a half-dozen decoys in the narrow channel.

More decoys might have helped to pull in a large flock, but I knew from experience that a few in the narrow channel would be enough to lure in a small flock, and they certainly were a lot less work than the large decoy spreads some hunters use. Arranging the willows in my makeshift blind, I checked my watch and found it was time to shoot. Now all I needed was a live duck.

The chatter and whistling wings of a flock of mallards attracted my attention skyward. Searching the skies for the source, I finally saw them high above. "Come back, come back," I pleaded with my call, but they weren't interested, and wave after wave of ducks NOVEMBER 1975 continued south toward the safety of the lake. Occasionally a few would break from the formations, but they would always recover and turn back toward the lake before coming into range.

Beside me, the dog was shivering with excitement as I serenaded the passing mallards. All of a sudden he leaped out of the blind when he spotted one of my decoys drifting by. Doing what comes naturally for a retriever, he dutifully brought the decoy in and dropped it at my feet.

Scanning the skies for ducks, I decided against better judgment and waded out in the channel to place the errant decoy. As I set the imitation in the water, I looked upstream and spotted a flock closing in from the east. Freezing motionless, I watched as a dozen or so birds headed my way.

Hoping the dog wouldn't move and spook them, all I could do was wait as they came closer. Low enough, they would be in range if they came over. "Shoot!" said my nerves. "Too far!" said another voice, as I knew they were still out of range. (But, I was still talking to myself).

Now they were over me and I swung on a green head as they flared. My first shot knocked feathers loose from the bird, and the second dropped him in the channel. My last shot missed another rapidly climbing drake and then they were gone. Reloading quickly, I headed for the blind as Whiskers retrieved the bird.

From close behind I heard the whistle of wings. Rising to shoot, I swung on a pair of hen mallards as they frantically beat their wings to gain altitude. Hold ing back, I let them fly away unmolested. If I had shot one, my hunt would have been over. In the point system, they were 70-point birds, and with my 35-point drake, I would have been over the allotted 100 points.

The purpose of the point system is to allow a greater harvest of surplus birds, yet reduce pressure on those species of ducks in short supply. Most of the late-season birds were mallards; perhaps the most important duck species to Nebraska hunters.

Traditionally there is a surplus of drake mallards in the spring, so the drake is assigned a lower point value than the hen. This allows the late-season hunter to shoot an additional bird if he is able to distinguish the sexes. Often this is easily done, as most of the later birds are drakes.

I was glad I had waited. The sun was barely up and my hunt would have been (Continued on page 47)

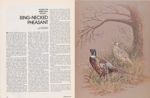

Game Bird Gallery

HERE ARE PRESENTED some original game-bird paintings by Ed Wards (Charlotte Edwards), a Nebraska born artist whose love of nature is readily revealed in her work. She is self taught, but is blessed with natural ability and thus evolved here own style. To conjur up images to put onto canvas, she calls upon past experiences and pleasant memories of campfires, hikes, hunts and other outings she and her husband have enjoyed. She prefers to paint birds, and finds doing backgrounds and landscapes "a bore". As a hunter, she feels frustration when trying to put on canvas the beauty of a rising bird or glint of sun on frosty decoys. A companion to her brush as a tool to produce such realistic paint ings is her camera. Her studio is in her home at 9622 Meredith Avenue in Omaha. She welcomes viewers interested in her work. She does paint on commission, but prefers to paint what she feels, and hope that buyers will be happy with them

FISHING... PADDLEFISH SNAGGING

FOR MOST NEBRASKA fishermen, November is a big, fat nothing. October might have brought some tolerable fall fishing, and December occasionally produces ice fishing. But for most, November lies in an angling limbo —too cold for open water fishing, but not near cold enough for ice fishing.

For a small and unusual breed of Nebraska anglers, however, November is just the beginning of their own special brand of good times. These are the snaggers who ply the Missouri River of northeast Nebraska in pursuit of the paddlefish.

Snagging is an indelicate process, and it is also illegal in Nebraska except for a part of the year and in the Missouri River only. Its straightforward method of get ting hook and fish together, and the legal sanctions against it elsewhere, undoubtedly contribute to the low esteem snagging carries among other fishermen.

However, Lee Rupp, biologist in charge of fisheries management for northeast Nebraska, justifies snagging, saying "paddlefish snaggers are, by and large, going after a species by the only available means. They need not be ashamed of the method, for without a regulated catch, surplus paddlefish would only go to waste."

Perhaps Rupp's statement about "the only available means" is better understood in light of a little background on the paddlefish, or "spoonbill" as he is also called. The paddlefish is of an archaic design, being very similar to species present millions of years ago, in the Age of Reptiles. Its body has no bones; only a gristle like tube that serves as a spine.

Though frightening in appearance, with a long, flatbill, small beady eyes and large mouth, the paddlefish is absolutely harmless. It feeds entirely on microscopic plankton that it gathers as it swims along with mouth wide open. Despite such an unexciting diet, the paddle fish grows fast and large, weighing from 15 to 20 pounds at 5 years of age, and with some of the old-timers tipping the scales at up to 80 pounds.

Thus it's obvious that snagging is called for. How else would you make use of a relatively abundant, large and tasty fish that ignores all manner of bait, lure or fly?

The paddlefish was once found throughout most of the Mississippi and Missouri drainages, but it is now most abundant in the areas below the Missouri's main stem dams. At Gavins Point Dam, the spoonbills spend a good part of winter in the stilling basin immediately below the dam, or in the deeper holes of the river down stream.

Here is where the snagger puts his tackle to work. The rod is usually a short affair, with all the flexibility of a 20-ounce pool cue with line guides. This is fitted with a salt-water casting reel, loaded with heavy monofilament line in the 40-pound-test range. The business end of the line is equipped with a large treble hook, perhaps 6/0, embedded in a 3-ounce chunk of lead.

Shore-bound fishermen generally work from the high concrete wall on the north shore of the tailwaters with good success, but snaggers in boats generally fare better. The hook is worked with sharp upward jerks of the rod, a crank or two on the reel to retrieve slack line, then another jerk.

Though some action is available in November, best snagging comes in late December and into January. At that time, snagging produces bigger fish and more of them. It should be apparent by now that there's little room for weaklings among the ranks of snaggers. The weather is usually miserable, the tackle is heavy and hard to handle, and hours of pumping the big rods is nothing short of gruelling.

There's usually little question about whether the fishing will be good or poor. Attimes, there doesn't seem to be a single spoonbill in the tailwaters, then suddenly everyone has a fish on. Paddlefish feed little in the win ter, so the search for food is apparently not the cause for their movements. But, no one is sure just what motivates their activity.

Fisheries biologists say that the paddlefish population from Gavins Point Dam to Ponca is in good shape. There are lots of fish of all ages, and they grow rapidly. Unfortunately, this is not true in other stretches of the river.

Channelization below Ponca seems to have wiped out paddlefish spawning areas. And upstream, no spoon bill reproduction has been documented above Fort Randall since the last of the Missouri River dams was built. The fish now being taken appear to come from a relatively short stretch of river that still offers suitable spawning areas.

Most of this spawning habitat lies between Lewis and Clark Lake and Fort Randall Dam, though the area from Gavins Point to Ponca may be producing some spoonbills. At any rate, this area spans less than 100 miles, yet it must support considerable snagging pressure.

Obviously, an excessive harvest by snaggers could hurt the population, although this does not yet appear a threat. However, any alteration of the stretch of river with spawning habitat, either through channelization or construction of new dams, would undoubtedly wipe

Snaggers have been cooperative with Game and Parks Commission biologists running a tagging study and creel census the past few years. These studies are yielding important data that will come in handy should the paddlefish be threatened someday.

Snaggers have also done well in observing new, more restrictive regulations. These include the lowering of the possession limit from four fish to two, and ending the practice of "high-grading" or releasing a small fish in hopes of catching a bigger one. In past years, the released fish often died of their snagging wounds and went to waste. Now, however, snaggers must keep each fish they take and count it in their daily limit, which is two.

According to Rupp, a few snaggers in the past have used bad manners and unsporting tactics in the tail waters area, that have branded all who use the method as bullies and heavy-handed game hogs, interested more in meat than sport. However, the majority of the snag gers have made a good start in bettering their image through their cooperation with biologists and observance of new regulations. Hopefully, an understanding of the fish they seek will create a collective conscience that will allow snaggers to police their own ranks and improve their own image, while also cooperating in the conservation and management of the paddlefish.

The Persistent Coyote

IN THE DAYS of the pioneer, no animal epitomized the vast*mid-continental grasslands more than the bison. They seemed as inexhaustible as the grass itself. But, in two short decades, the hide hunters and bone pickers gleaned the land of all but the far northern herds. By the early 1900's the land of the bison was fenced and farmed.

Wheat fields spread over the short-grass plains and corn over the tall-grass prairie, livestock grazed the land too dry or rugged to cultivate. Man subdivided the grasslands with roads, farmsteads dotted each section and cities grew to buy and sell the land's bounty. We tamed the prairie and made our mark everywhere.

Though the bison was swept from the prairie forever, a symbol of its wildness endured: an animal as adaptive and clever as man himself. The coyote accepted its new environment and thrived. From the beginning, they were marked as the enemies of man. Trapped, poisoned and dragged from their dens on twisted barbed wire, they were subjected to the darkest of man's nature. But they survived. Where once they hunted in large bands, they began to hunt alone or in pairs. With each generation they became more nocturnal, emerging only after dark to hunt, mate and roam the prairie.

Other predators were not so adaptive and disappeared from much of North America. With these

Today, coyotes are probably the only significant predators in the United States large enough to successfully attack and kill an animal larger than a rabbit. They are the only animals left that send a primitive chill of excitement through us if unexpectedly we meet. The coyote seems to call up all that is wild and predatory in our ancestry. In them we recognize something of ourselves.

Even though the coyote is the largest grass land predator, their size falls short of the estimates given by many of their captors. An average male weighs 25 pounds and stands 21 inches high at the shoulders. Females are slightly smaller. But their bodies are supple and their movements agile. Few animals have their stamina and endurance. In appearance they truly are "little wolves", but in temperament they are far more docile.

A study made 25 years ago of feeding habits of Nebraska coyotes dispelled some of the commonly held beliefs that the coyote is a villainous marauder that lives by hamstringing deer, pulling down cattle and ravaging turkey farms. The report was based on the contents of 2,500 coyote scats and 747 stomachs. All of the state's major land types, from intensive farmland to sandhills ranch land, were represented in the study.

As might have been expected, analysis of what the coyotes had been eating revealed that they are primarily carnivores, feeding on the flesh of vertebrate animals. Substantial quantities of insects and plants were found to be a part of the coyotes' diet, too, but the largest portion of their food was made up of birds and mammals. Statewide, the remains of mammals were found in the stomachs of 89 per cent of the coyotes; birds in 43 percent, insects in 9 percent and fruit in 4 percent. Examination of the scats collected revealed similar percentages. In volume, the flesh of mammals was found to make up 78 percent of the coyote's diet, birds 18 per cent, and fruit and insects the remaining 4 percent.

It became obvious that the coyote is an opportunist, taking those foods that are most abun dant. Examination of stomachs and scats showed that they rely more on mammals for food in the winter and early spring when birds, fruits and in sects are unavailable or difficult to locate.

Detailed examination of the stomach contents

revealed more precisely what Nebraska coyotes eat.

Rabbits made up 54 percent of their diet and wild

mice another 7 percent. The remains of deer were

30

NEBRASKAland

NOVEMBER 1975

31

found in only 0.1 percent of the coyote stomachs.

In all, 31 different mammals were found to be on the

coyote's menu.

found in only 0.1 percent of the coyote stomachs.

In all, 31 different mammals were found to be on the

coyote's menu.

On occasions, coyotes have developed a penchant for domestic livestock; a trait that does not endear them to ranchers. The Nebraska study showed that domestic stock, including cow, horse, sheep and pig, made up 12 percent of the coyote's diet. The authors noted, though, that no attempt was made to distinguish between carrion and fresh meat.

"Many of the remains almost certainly represent carrion. Many farmers do not bury or burn dead young pigs, for example, but make them available to scavenging coyotes by carrying them into fields or by simply tossing them a short distance from the breeding pens.

"It is believed that coyotes rarely if ever kill mature cattle, or even try. Calves are sometimes vulnerable to attack and coyotes occasionally kill them."

Birds were found to be an important item in the coyotes' diet. Wild birds made up about 9 percent of the food material found in their stomachs, as did domestic fowl, primarily chickens. Pheasants were the single most important wild bird taken by coyotes, but still only accounted for 7 percent of their food. The occurrence of both pheasant and grouse in the stomachs of coyotes was highest during the winter months, suggesting that some may have been winter-killed birds scavenged, rather than live birds captured.

Even though insects and fruit were found to be of only minor importance in the coyote diet, it is enlightening to find such a "beastly villain" preoccupied with catching crickets or grasshoppers and picking ripe chokecherries or grapes. One coyote shot on the National Forest near Halsey was found to have 345 grasshoppers and 20 crickets in its stomach. A sparrow hawk with such an appetite for injurious insects would surely be lauded.

The coyote's "impulse" diet is one of the reasons that the species has been so successful in co existing with man. Their tastes are wide-ranging, and unlike the prairie wolf, that had no alternate prey once the bison and elk were shot off, the coyote could thrive on a farmer's dead livestock and field mice just as well as winter-killed deer and wild rabbits. But the coyotes' diet is only one of many traits that marked the species for survival. Coyotes are prolific breeders, capable of rebuilding their numbers rapidly following natural die-offs or intensive predator-control programs.

Unlike wolves that do not mate until their second year, the coyote is sexually mature by its first fall and females may have their first litter when only a year old. More significant is the fact that litter size is the inverse of population density.

Coyotes are territorial, and thus each animal stakes out and defends an area large enough to meet his food demands. If prey is abundant, the territory will be smaller than if prey is scarce. In a stable situation, young are produced at a rate that will fill all the available territory. Excess young must spill over into surrounding, new territories, if there are any. If more coyotes are whelped than there are available hunting territories, reproduction success drops to bring the population back in line with what the land will support.

Exactly the opposite happens if large numbers of coyotes are eliminated from an area. When intensive poisoning or trapping programs reduce coyote numbers, more breed at a younger age and the litter size increases dramatically. In an area of Texas where predator control measures were introduced, the average litter size jumped from 4.3 to 6.9. The irony of the control programs is that the more coyotes that are killed, the more pups the remaining adults produce. Some biologists have actually suggested that predator control programs result in an increased number of coyotes over the long run. They reason that coyote populations normally are cyclic, and if left alone would build to numbers exceeding what the land could support. Die-offs would follow and several years would be required for the population to recover. Predator control programs artificially keep coyote populations from peaking and hence from dying off. Over a 20-year period, the average number of coyotes on a "controlled" area could actually be higher than if the population was allowed to cycle naturally.

Another reason for the coyotes' success is the high survival rate of their young. In areas where they are not disturbed, coyotes are believed to be monogamous and maintain close family ties. Coyotes mate in mid winter, and Nebraska pups are generally born during April. During the first few days follow ing birth, the mother remains in the den with the pups. During this time the male brings food for the female. After the female leaves the den, both parents provide for the pups. Between 9 and 14 days, the pups' eyes open, and by about 3 weeks they totter to the den entrance. For several weeks they will wrestle and practice hunting insects near the den. After five weeks the parents begin bringing meat for the pups to tug at and eventually eat. The adults hunt primarily during the morning and evening, lay ing up in heavy cover within sight of the den during the day. They will aggressively defend their pups, and if distrubed by man, they will move them to a safer den site. Should one adult be killed, the other assumes all parental duties.

As the pups grow, they stray farther and farther from the den, occupying their days with the serious business of stalking and pouncing on insects and

Though coyotes possess all the vocal, facial and posturnal expressions typical of animals with frequent social interactions, they are most commonly seen as singles or pairs. Before man disrupted their way of life, the coyote probably formed social groups throughout the year and cooperated at capturing prey. Today, adults may or may not remain together when the fall break-up occurs. A Minnesota study showed that 60 percent of winter coyotes travel singly and 40 percent with one other coyote.

Probably solitary coyotes are more successful at avoiding man's attention and thus have survived to breed and raise pups that likewise are less social. Through the evolutionary mechanism of natural selection, man has eliminated those individuals most vulnerable and left in their place worthy competitors to breed. By crowding and hunting these predators we have created a "super coyote."

In Nebraska, as in most livestock-producing states, the coyote has been the target for hundreds of thousands of dollars in predator control. And, as

Stanley P. Young, former biologist of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and author of the now classic text The Clever Coyote, assigned himself to this predator's place on the civilized prairie.

"From civilized man's selfish point of view, predators are commonly looked upon as pests or outlaws with almost every hand raised against them. In fairness to these animals, it should always be kept in mind that their destructive habits cannot be due to criminal intent, but are due wholly to their efforts to gain a livelihood by the only means that nature has provided through untold ages of evolution.

"...the coyote, when not an economic liability ... requiring local control, has its place among North America's fauna. Even the coyotes' bitterest enemies amongst men...admit this, if for no other than an aesthetic desire to hear its yap with the setting of the western sun. Because of its versatile attributes, it is extremely doubtful that it ever will entirely disappear from the landscape, in spite of so many hands...constantly turned against it."

DRESSING BIG GAME

Field care is as important as downing game, and speed is often critical. Here is system recommended as most efficient, yet simplest to perform with minimum of equipment

DURING THE stalk or search or wait for that deer or antelope, little thought is given to how to handle it after, or if, one is brought down. How ever, even more important than the techniques used in bringing down the animal is the care given it in the field. And, depending upon the weather, it can mean the difference between excellent meat and a tainted, distasteful carcass.

Probably any system of getting the insides removed is better than leaving them in any longer than is abso lutely necessary, but the neater the job is done, the better. Here is a recommended procedure for field dressing that is fast, simple, and relatively tidy.

Opinions vary somewhat on some procedures, such as removing glands from the "knees" of bucks, and also of cutting the throat to allow good bleeding, but these are actually of minor importance. Many experts agree that removing the glands is unnecessary, but it certainly doesn't hurt. And, field dressing or a high-power bullet makes cutting the throat unnecessary, but this is also a matter of preference.

If the glands are removed from the inside of the hind legs, the knife should be very thoroughly wiped or washed before continuing, as the musk is potent and will contaminate the meat. A large knife is not necessary, and could well be dangerous, but it should have a sharp and rigid blade. Removal of the windpipe is one of the most important steps of dressing, as it is here that spoilage first is noted. After splitting the hide, sever the windpipe just under the chin

RIVER-BOTTOM BUCKS

(Continued from page 71)trees, but they may be moving for another half-hour to 45 minutes in the thicker timber before bedding down. Maybe they round out their corn breakfast with a little green browse.

Since Ralph wasn't hunting, Gary decided to take over his regular stand. With Gary's usual post on a ridge open, I moved in. We've all hunted the Monroe area long enough that everyone has their regular stands and wouldn't think of moving in on another hunter's area.

"Go down the ridge until you think you shouldn't go any farther," Gary advised me when we split, "and then go another 100 yards. You 11 have the bestview there."

I did what Gary said and after going what at first looked like 100 yards too far, I leaned up against a Cottonwood that offered the widest field of view and best backrest. Every once in a while along the Loup River you find high ridges that have managed to hold their soil while the river washed away the land around them. They're naturals for deer hunting, giving hunters the same advantage in height that most tree stands do.

I'd carried in a small pack with coffee and sandwiches. I dumped the contents out and used the canvas as insulation be tween me and the snow-covered ground. I'd also carried a pair of insulated cover alls. I usually sit until I get about as cold as I can stand, then pull the extra layer on.

It was about 15 minutes into the season when I decided that I was as cold as I was going to get. I reached for my coveralls and pealed off my orange vest. I was all stretched out with one arm in and one arm out when that five-point buck walked into an opening only 20 yards below me. He had come from the east; the direction of the cornfield. My reasoning had paid off. The buck was on his way back from the corn, but it didn't seem like I was going to cash in on him, all tangled up in clothes, three feet from my rifle and with the buck looking me right in the eye. The winds seem to corkscrew around the ridge, and it was only seconds before the buck caught my scent. He trotted off about 30 yards before turning for another look to confirm his suspicions. By then I had my rifle up and the crosshairs just behind the front leg. I've shot a .264 magnum since I was 17. I like the rifle but it has the bad habit of kicking enough to block vision at that critical moment of impact. Consequently, I've seldom seen the deer at the time of the shot, and I don't get much of an idea if he is hit or not. That morning was no different. After the recoil of the first shot I saw the buck throw it into high gear toward the densest clump of cedars around. I chambered another round and touched off without much hope 42 of hitting that white flag bobbing away into the trees. It didn't feel good. But while I was jacking a third round into the cham ber, the buck crumpled in the snow.

When I field dressed him, I found where my first 140-grain slug had entered just behind the front leg and exited on the opposite side of the rib cage. The second shot was probably embedded in some cedar tree, but the buck had been running dead after the first shot.

I'd just field dressed the buck when the other three showed up, as I described earlier. By the time I'd settled down from that experience, my sandwich was cold again, so I went to work retoasting it. I nearly had the job done when I heard a lone shot from the direction of Gary's stand. I'd hunted with Gary long enough to know that it was a meat-pole shot.

I stuck the sandwich back into my pack and headed over the ridge to help him dress out his buck. I was barely to the bottom of the other side when two bucks came roaring across the corn stubble about 150 yards east of me. They were coming directly from Gary's tree stand, and from their speed it was obvious that all parties had met. One was a small one, three on a side, and the other one looked like he had five. His rack was wide and heavy at the base.

Gary was still trying to get his breath when he started to tell me what had happened.

"I had been in the stand for about a half hour without seeing a thing," he said. "The sun had just cleared the trees when a string of does filed out of the timber into that grassy opening east of my stand. I watched through the scope, looking for horns. The first four were all does. A fifth one was hanging back in the brush. I was sure it was a buck by the way it was act ing. I practically had him hung in a tree and field dressed. Finally it followed the others into the open and it was a doe, too.

"I must have sat their another 10 min utes before I heard you shoot twice," Gary continued as we walked toward his deer. "I figured you had your deer. That's when it started to get really cold sitting in that tree. I knew you'd start a fire and that you'd probably toast a sandwich and wash it down with a couple cups of hot coffee. The wind started pushing through that opening after the sun was up. I thought I could even smell that hamburger warming over the fire.

"After about 45 minutes I figured that your shooting had put an end to the deer

"I'd walked about 30 yards north," he continued as we traced his trail through the snow, "when this buck came running straight at me. Looked like it had three on a side; nothing to brag about but good salami material. I froze in place and let him go by, no more than 20 yards in front of me. When he got about 50 yards I dropped him."

I held Gary's three-pointer spread-eagle while he started field dressing. He continued with his story.

"Well, I'd no sooner shot than here came these other two bucks, a big five pointer and a smaller one, tearing by me heading for the ridge. They must have seen you walking over the top because they turned and headed straight into the corn field. I could have dropped that big one like a pheasant from a plum thicket."

We dressed Gary's deer and dragged it up to mine. His was too far back in the timber to get a car to. We poked some wood into the fire, poured a round of coffee and I drew a pair of cold sandwiches out of the pack. This time nothing interrupted my warming ceremony.

Gary and I sat there for the better part of an hour rehashing our new and old deer hunts —the 400-yard shot Gary had made on a whitetail from the ridge, the first buck I ever shot, and two years ago when we both shot the same deer. I remember Indian wrestling in the grass to see who was going to tag it since it was a small buck and only opening day.