NEBRASKAland

October 1975

NEBRASKAland

VOL 53 / NO. 10 / OCTOBER 1975 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Fifty cents per copy. Subscription rates $5 for one year, $9 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Single Copy Price: 50 cents commission Chairman: jack D. Obbink, LincoJn Southeast District (402) 488-3862 Vice Chairman: Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 2nd Vice Chairman: Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-Central District, (308) 745-1694 Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-central District, (308) 452-3800 H. B. "Tod" Kuntzelman, North Platte Southwest District, (308) 532-2982 Director: Willard R. Barbee Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, jr. Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: jon Farrar Greg Beaumont, Ken Bouc Contributing Editors: Bob Grier Faye Musil, Tim Hergenrader, Roland Hoffmann, Bill janssen, Ben Schole Art Director: Michele Angle Farrar illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1975. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska Contents FEATURES ALL GROUSE ARE TROPHIES! STRIPER HOT ACTION IN COLD WEATHER 8 WHEELS OF JUSTICE VS. WHEELS 12 FOWL CHOLERA 14 TURNCOAT SEASON 16 FAMILY HUNT 24 OUTDOOR ENCOUNTER 26 FISHING WAX WORMS 32 PRAIRIE LIFE/BATS 34 DRESSING GAME BIRDS 38 DEPARTMENTS SPEAK UP TRADING POST 49 COVER: In mid October, there is often the hint of frost in the air, and usually some migrating ducks. It is a magnificent time of year, bringing out the hunter and nature buff in everyone. Photo by Jon Farrar. OPPOSITE: Like motionless yachts, willow leaves float the quiet surface of a backwater on Nebraska's White River during the soft days of Indian Summer. Photo by Greg Beaumont.

Speak up

Thanks, CannersSir / I wrote a letter in the July Speak Up asking for recipes for canning carp, and I have answered some of the responses, but I would sure like to thank all those nice folks who wrote me, giving me their recipes. A special thanks to the director of the Game and Parks Commission for his recipe (secret—1 chicken bouillon cube).

Howard Smersh Estes Park, Colo. Keeping in TouchSir /1 am currently a lance corporal in the U.S. Marine security guard at the American embassy in Tehran, Iran. I am receiving NEBRASKAland magazine each month and so I thought I'd write to you and tell you how much I enjoy it. I have spent most of my 21 years in Nebraska and I believe that there are very few places that can compare to Nebraska for being an all-around good place to live.

By reading your magazine, my memory is kept fresh as to what 'The Good Life" really is. Thank you so much for making it possible to have a little bit of home all the way over here.

Sid Hooper APO N.Y. N.Y.Thank you Sid, and I hope you get back soon to enjoy more of Nebraska in person. (Editor)

Vicious AttackerSir / I have never seen such a vicious, biased attack by an editor on a reader! (Editorial reply to a Speak Up from Mrs. R. Foster in March, 1975 issue). And, your comparison isn't even authentic. What other crop is raised, tended, fed and protected by the farmer, and then harvested and carried off by a horde of strangers who pay nothing and leave behind litter and destruction?

I guess we are not lucky enough to see many of your "By-and-large honest, clean-cut hunters" here. Our opinion is formed from our own experiences: signs torn down and destroyed, fences cut, gates left open, cattle shot and left to suffer, domestic fowl killed and carried off—one year my entire flock of white muscovy ducks disappeared in the first two days of hunting!

We have planned and maintained a 4-acre refuge a half-mile from any road, and it is clearly posted, yet they will drive in to it across neighbors' fields or shoot into it with high-powered rifles to scare the game out, knowing there is no way to get any animals or birds that are hit.

These hunters of yours trample through our unharvested row crops, drive across our newly planted wheat fields, and shoot so close to our buildings that pellets lodge in the siding and windows are broken. Every year my laying hens moult during hunting season because we can't keep hunters out of the windbreak just behind the house. If we try to get the hunters out, they drive away speedily, throwing out dead hen pheasants as they go. Some of them come and camp during the open season, and these dress and eat the hens while they are here.

There are no longer any quail in this area, so we local farmers buy them and raise them, to be liberated the next year so we will be able to see and hear a few around. We feed them at nearby feeding stations all winter long-and your honest, clean-cut hunters slaughter them right in the sheltered feeding stations.

I won't go into any description of the beer and liquor containers, paper cups, napkins and sacks, etc. that are left behind for us to clean up. Isn't it supposed to be true that any reader has the right to express an honest opinion, even if it does not agree with that of the editor? In view of your reply to Mrs. Foster, I truly dread your reaction to my letter —but here it is.

Mrs. D. D. Griffith Carleton, Nebr.You sound like you expect another unwarranted attack—but, I hope that is not the case. I sympathize with your situation and know that location, etc. can mean an especially grueling time for landowners because they draw a disproportionate amount of pressure. And in your case, apparently some bad ones. But, you must realize that hunting is presently undergoing a transition from the time when most land was open and there were very minor problems. Now, people are crammed in ever-increasing numbers in cities and much of the land is closed or closely controlled to hunting, and that leaves nothing but frustration, and competition, lust as industry pollutes air and we must all breathe it, whether we like it or not, landowners close their land, or lease it, or destroy habitat so that nothing can live on it but crops, and even they are polluted by an overuse of chemicals, but people must eat them. Social responsibilities become increasingly important with more people, and this perhaps includes the hunter more than most other sections of the public. Any suggestions anyone has on ways to improve cooper- ation and observance of the laws are welcome. Hopefully, both manners and opportunities for hunting can be much improved. Penalties for violations must be stiffened to discourage bad behavior and to try to weed out the "bad guys" without curtailing the good ones. And, I maintain most hunters are honest, personable people. (Editor)

Following is a poem and artwork done by a Lincolnite, David Okerlund, reflecting upon the destruction of wildlife habitat. (Editor)

NEBRASKAland Magazine invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to Speak Up. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters. — Editor.

Rivalry, exercise and wary birds combine to make Sand Hills a hunting challenge

All Grouse Are Trophies!

NOW I SUDDENLY remember why I only go grouse hunting once a year/' said a tired and footsore Leroy Stauffer as we sat down to rest. Whiskers, his three-year-old black lab, limped over to me and offered a cactus-spined paw. We were a weary trio, having walked for over six hours in the rolling sandhills west of Halsey.

It was Sunday, the second day of Nebraska's 44-day 1974 grouse season, and we were hunting on part of the Nebraska National Forest west of the headquarters area.

Leroy, my brother-in-law, and I were renewing a friendly rivalry we carry on every hunting season. I had driven to his home in Kearney the night before from Lincoln, where I was a journalism student at the University of Nebraska.

After swapping lies for a few hours, we hit the sack, planning to get an early start in the morning. The next thing I remembered was the smell of bacon frying at 4:30 a.m. In the kitchen, my sister Carol was busy cooking a hunter's breakfast. After stuffing ourselves, Leroy and I loaded the car and headed north.

It's about a two-hour drive from Kearney, so we figured on reaching Halsey about sunrise. Since we were a little early, we stopped at a cafe in town for a cup of coffee.

The little cafe was packed. Olive-drab clothing of most of the patrons identified them as other hopeful grouse hunters, but I recognized one of the customers as Norm Dey, upland game specialist with the Game and Parks Commission, working out of Lincoln. He was at Halsey to man a check station for grouse hunters, and he told us that hunters had averaged slightly better than a bird each the day before and he would expect about the same success today.

Encouraged by this, we hurried to the place we had planned to hunt and began getting our field exercise shortly after sunrise. It was one of those rare days in the Sand Hills. Not a breath of air stirred; onfy a few light clouds obscured the sun. The air was chilly now, but we knew it would be warm by mid-morning and hot by noon. Sporadic gunfire could be heard in the distance all around us, so it sounded like some hunters were getting action.

We started walking west along a line of hills. Our plan was to hunt the morning hours on the side hills and in the draws where a favorite food of the sharptail, the wild rose, is abundant. Then, toward the middle of the day, we would hunt near the crest of the hills hoping to catch them loafing in the cooling breeze.

Since there wasn't any wind to cover the sound of our approach, we thought we would have trouble getting within shotgun range of spooky birds. Our suspicions were confirmed a few hours later when we began noticing birds getting up several hundred yards in front of us.

"I sure hope the wind comes up soon; I left my deer rifle at home," Leroy said jokingly as we topped a rise. I started to agree with him but was interrupted by a rustle of wings and the weak cackle of two sharptails as they flushed about 20 yards in front of him. His 12-gauge over-under bellowed twice and both birds continued on their way until they disappeared behind the next hill. Stifling an impulse to chide him about his misses, I offered some consolation by telling him that I thought he had winged one.

Knowing how easy grouse are to kill, we walked to the point where we had lost sight of them, and Whiskers soon reminded us of the value of a good retriever. Casting about the hillside, he suddenly locked on a point that would have made an Irish setter jealous.

Waiting until Leroy closed in, Whiskers suddenly lunged into a patch of wild rose and came up with one very dead grouse-the one Leroy had winged only minutes before. This time I couldn't resist the temptation to needle him about using a dog to catch birds instead of shooting them himself.

By this time, several hours had elapsed so we decided to rest awhile. Checking the bird's crop, we found it stuffed with a mixture of wild rose hips and grasshoppers. Since it was early fall, we knew the birds wouldn't have any trouble finding food but we were certainly having trouble finding them.

Taking a drink from his canteen, Leroy said the birds were a little spookier than in years past. We agreed that it was probably due to the lack of wind that commonly blows in this area. Meanwhile, a slight breeze was starting to come up behind us so we turned and headed toward the car, facing into the wind.

We had walked about a quarter of a mile when another pair of birds flushed ahead of Leroy. These he missed cleanly. "Scare some of those birds over my way," I yelled at him. I couldn't hear what he replied but my hunting instincts told me that a new shotgun had received the blame for the missed birds.

I was beginning to wonder if I would ever get a shot when a bird exploded about a yard ahead of me. Reacting too quickly, my 12-gauge pump was ready in an in stant and the bird fell less than 15 yards away. Expecting to find a torn-up mess of feathers and meat, I cussed myself for shooting too soon. My fears were forgotten though, when I found a cleanly killed, head-shot bird.

photo by Bill McClurgThe score was now one bird apiece. We must have walked several miles farther without sighting any more birds. As we topped one hill, two mule deer does flushed out of a draw ahead of us. A few minutes later, a half-dozen does and a large buck ran across the ridge in front of us. "It's hard to believe a deer could hide in these hills," I said to Leroy, but in seconds they were out of sight.

When we were within about a half-mile of the car, a flock of about 15 birds got up about 30 yards away. I was looking off to the side and didn't notice them until they were out of range. I looked over at Leroy who was also caught off guard and (Continued on page 46)

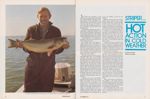

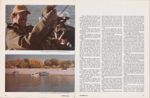

STRIPER... ACTION IN COLD WEATHER

Photos by Jim JakubTHE LINE was freezing in the guides of our casting rods as the eight a.m. radio broadcast reported 18 degrees locally. It was a beautiful, calm November day and we knew it would warm up, but for now, the fresh air out on the lake numbed our senses as we continued to jig the heavy lead bomber slabs.

A three-pound striped bass had already been caught and released. Too small. We were laboring under layers of insulated underwear and clothing when something hit Jim's lure so hard it almost jerked the rod from his hands.

"Got a big one on," he clipped, and strained as the fish tore line from his heavy baitcasting reel.

Jim Switzer and I had fished for stripers several times in October during the last five years. In the past we've had good luck, boating several fish in the 8 to 12-pound range. The last time we met some of the locals when we were cleaning our fish and they told us to come back in November, when the big ones were hitting.

We had already planned a mid-November deer hunt, so we decided to bring a boat along and try striper fishing if we scored on our bucks early and had time. We pulled onto Lake McConaughy from Lincoln on Sunday afternoon, the second day of deer season. Monte Samuelson at Lemoyne told us that the big ones had really been hitting, so we decided to pass up the deer hunting for a chance at a state record striper. He told us that other fishermen had been catching stripers at North Shore and Thies Bay, but that they had been hitting on the south side also.

Anxious to wet a line, we hurriedly backed the boat down to the water's edge and loaded up our gear. With only a few hours of light left, we headed over to North Shore and trolled slowly, with our lures working about 35 feet deep. Before dark we netted a 6-pounder and a nice 11-pound, 8-ounce striper, but caught and released many in the 2 to 3-pound class. Darkness was creeping up on us so we headed in with our two keepers.

Monday dawned cold and windy. Windy days produced poor striper fishing, at feast for us. It's hard enough to troll at the right speed when the wind is blowing, but it's almost impossible to jig properly. When jigging, we like to be able to drift slowly. That way we cover an area more effectively. Trolling, we use lead-core lines to get down on the bottom fast. We've found that the less line we have out, the easier it is to react to a strike quickly. Regardless, the high wind out on the lake didn't fit into our fishing plans, so we restlessly spent the day in camp.

Tuesday morning was cold but the air was calm as we headed for North Shore. A half-hour's trolling produced nothing but frigid fingers there, so we headed for Thies Bay —Monster Bay as we call it from the luck we've had on previous trips for stripers.

I had caught and released the three-pounder. Jim was jigging a yellow slab. He raised and then lowered his rod tip just as he had a thousand times before and the big striper hit the lure as it fluttered to the bottom. The fish didn't hesitate as it engulfed the lure, and Jim socked the hooks home. Adding fuel to the fire, the striper stripped most of the 200 yards of 20-pound mono from the reel before Jim finally turned the monster's nose, and then the see-saw battle really began.

Twenty or 30 minutes passed before we finally got a look at the deep-fighting bruiser. Jim pumped him close to the boat, but then it turned and bulled it's way back into deep water.

"Man, I got a hog on. Get the net!" Jim hollered. I got ready while he worked the fish in closer and I scooped him up in the big boat net. The powerful striper continued to thrash around as I unhooked it and held it up.

We had landed quite a few in the 10 to 12-pound class, and I said: "Jim, that's a big one. I bet it'll go 14 pounds."

OCTOBER 1975

"Yeah, it should go 14 at least," he replied. Our pocket scales only went to 10 pounds, so the fish's weight buried the needle past that point.

We should have quit right there and taken it in to weigh it, but to us, it was just another big fish. We were after the state record, not knowing it was on our stringer.

"These stripers are really great sporting fish" I said to Jim. "They have the speed of a trout and the power of a black bass."

"Plus the appetite of a hog!" he added. "Remember the one we netted on the surface back in October?" he laughed.

"We had been jigging for stripers when we noticed something swimming on the surface some distance away. Jim started the motor and we went over to investigate. A nice striper was swimming on the surface with something hanging out of its mouth. We netted it and found that the five-pound striper had tried to swallow a one-pound catfish, and the spiny pectoral fins on the side of the cat had lodged in the striper's throat.

Other times when we were catching stripers, we noticed dead and injured shad floating to the surface. Stripers are school fish, and Monte told us some bank fishermen had caught them in the evening as they drove schools of shad into shallow water.

We jigged a while longer, but our luck had turned sour. We caught a few small ones, but no keepers.

"How many of these are kept as white bass?" Jim asked as he unhooked a two-pounder.

"I don't know," I replied, "but fishermen should learn the difference and turn back the smaller ones to grow up."

The white bass is a lot more compact than the longer, streamlined striper. Plus the striper has a series of continuous dark stripes running lengthwise on its side, where the white bass's stripes are lighter and often broken. Not too much is known about whether the stripers are reproducing in Big Mac, but we caught some one-pounders. These could have been from* natural reproduction, but we had heard that the Game and Parks Commission had been stocking new fish every year, so there was no way to tell.

"Let's try the south side," Jim sug gested as he slipped the bass back into the water. I cranked up the motor and we headed toward a tree-lined cove on the south side.

As far as we could see, there was only one other boat on the lake, and it was coming toward us as we crossed the lake. Recognizing the boat as Bob Stahr's, a fishing guide who operates on McConaughy, we slowed to see how they had done. He reported that they had been working the south side and had caught some small ones, but no keepers. After showing them our big one, we parted; they for the north side, where we had been, and us back to a cove on the south shore. Jigging produced no action, so we trolled a couple of hours. Feisty little smallmouthed bass and a few small walleyes were all we hooked, as the stripers apparently weren't interested.

Yielding to an urge to wander again, we headed back over to the north shore where we met Bob Stahr again. This time they had two big walleyes, an 8-pounder and one about 10. It was getting to be late afternoon as we let down our trolling lines off North Shore. Monte had told us that if we didn't get stripers there in the morning, we could just about plan on getting them toward evening, just before dark.

The way we troll is to make about a quarter-mile pass straight out from North Shore Lodge, then head east. Again, we try to work in about 35 feet of water. It must have been the right combination, because every time we made a pass we either landed one, had lines broken or had hooks straightened.

These fish have so much power, the large ones either bend or straighten hooks on the lures we were trolling. Monte had told us to replace the standard hooks on our Bayou Bogies and Thinfins with heavier hooks. We did, but they still weren't stout enough.

Jim hooked another big one that took 200 yards of 20-pound line from his reel and just kept going. We both knew that it was a bigger fish than the one we already had, and we lost some others that felt almost as big.

We caught and released several 4 to 6-pounders, and kept bigger ones. I can't remember how many we caught just before sundown, but when we went in, we had our limits of 2 each, all over 6 pounds. When the big one tipped the scales at 15 pounds, 8 ounces, we knew we had a new state record. How much weight it had lost between 8 a.m. when we caught it, and 6 p.m. when it was weighed is hard to say, but probably it was at least a pound. We figured it was just another big fish, and we had kept after a bigger one.

It doesn't really matter though, because next year the record will probably be bettered again. It could well be a 20 to 30-pound fish to hold the record for any length of time.

We both like to fish Big Mac because we never know what we'll catch. Besides stripers, we have caught trout, walleye, perch, white and black bass, channel cats and even carp on the slabs. The last two state records have been caught by jigging slabs. We catch our biggest fish on them but catch more fish by trolling Bayou Bogies.

We know bigger ones are in there, both from our experiences and what others tell us. Next year we'll be back with stronger hooks, heavier line and plenty of warm clothes for another go at an even bigger state record striper.

This was a record striper, but only briefly, as the record has been broken several times since, and presently stands at 17 pounds, 3 ounces. (Editor)

10

Wheels of Jutice vs Wheels

The following story is true; at least according to court records. The names of violators are fictitious to protect any living relatives.

AS NATIVE NEBRASKANS, we probably tend to think of our ancestors as sober, law-abiding citizens who stoically wrested a living from a hard land. Yet, tales of moonshine stills and gambling dens, along with various rough and tumble episodes, filter down through our history, like the time Sheriff Hudson arrested a Model T Ford for transportation of liquor.

There are cases like that of one southwestern Nebraska man who was taken to criminal court for winning $5 from his neighbor in a kitchen-table poker game. Watermelon steal ing brought a lad to criminal court early in the century.

In one instance, two men were charged with contributing to the delinquency of minors. They were accused of keeping two young ladies out too late. The case was dismissed the next day, though, when one of the men was charged with assaulting one of the young ladies with intent to do bodily harm.

But much more serious crimes appeared on court dockets, too.

In 1923 and 1924, the vast preponderance of criminal court records for Frontier County, for example, revolved around intoxication. Fines ranged from $5 to $20 and it seemed that a second offender could count on sitting out 30 days in jail. The only other crime anyone in Frontier County got caught committing with any regularity was assault and battery.

In fact, if Frontier County during prohibition years was any indication, it would seem that Nebraskans were just as busy evading the "revenuers" as Robert Mitchum in "Thunder Road".

Most cases seem to have been settled peaceably enough in court, but one man became rather irritated when served with a search warrant. He was finally charged with possession of intoxicating liquor, assault and battery, and resisting arrest. It seemed the county sheriff in those days had his share of frustrations.

In 1925 the emphasis in liquor law enforcement seemed to change in Frontier County. County sheriffs, with help from the judges and county attorneys, began digging out the rural stills. During that year, fat files began developing on the possession, transportation, manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages. The average Joe who got drunk on Saturday night could no longer achieve immortality through court records.

Many of the searches for liquor were unproductive and search warrants came back to the judges marked "nothing" where the lists of confiscated materials were supposed to be.

Some of the frustration experienced by enforcement personnel appears in excerpts from a letter to Frontier County Judge W. J. Siebecker from Red Willow County Sheriff, George McClain: "I was down to indianola to day and I found out that William Sands is sure making liquor...if you want to get out a serch warrant...! don't like to ask Hudson to come over as it is so far and if we wouldent get any thing I would feel Bad as I have all ready caused him so much driving without getting any thing...I will serch it frome here. I don't want to but in on your county, but this Liquor is coming to indianola and I would like to stop it...."

It seems as though the stills just "dried up" whenever the law appeared.

In 1925, though, many more cases found their way to court. The help of a federal, plainclothes agent began to pay off. His claimed expenses included a king's ransom in liquor purchases, which meant that the businessman was caught "red handed".

The case of the Ford touring car, license number 60-253, motor number 6185126 seems to have excited no special interest in 1925. Apparently, it has not been passed down among the momentous events of that time, from father to son, though someone may still remain who has heard tell of it.

It appears that the court records are for real, complete with public notice clipped from a local newspaper. A complaint was filed against a certain Howard Hoffshyster for transportation and sale of liquor. Next day, on August 4, a second complaint was filed against Cecil Hoffshyster for the same offense. Apparently, the pair was suspected of being in "business" together, for the complaints both charged that the crimes had been committed on the same day, August 1, and both men were said to be carrying the beverages in the same unsavory Ford touring car.

Warrants were issued for the arrest of both men, and for seizure of the car. Somehow, on the first warrant, Sheriff Hudson was able to complete only half his task. There is no indication where Hudson found it, whether the scoundrel had stopped for petrol or if it was parked outside its own house, but Hudson seized the car. Hoffshyster, apparently the driver, was nowhere to be found.

Cecil seems to have posed just slightly less of a problem than Howard. He was arrested, but it cost over $100 in mileage and 15 days time.

The wheels of justice kept grinding on, though, and Judge Siebecker tried the car on the one count and Cecil on the other. The automobile was not deserted, and its owner even hired counsel to defend it. The car's plea reads in part: "Comes now Howard Hoffshyster and respectfully represents to the court that he is the owner of the car above-mentioned, and on behalf of the said car says that the same is not guilty of transporting liquor."

Next came a motion from "the defendant, one Ford car... to dismiss the action because the proof varies for the complaint."

As fate would have it, the motion was overruled. The state had a good case, calling Earl Prall and Oscar Kindred as witnesses.

Judge Siebecker entered the following judgment: "...the automobile license number 60-253 and motor number 6185126 being represented by Kiplinger and Hansen, whereupon said cause came to be heard...and the evidence, upon consideration thereof the court finds the complaint as to said car to be true and that said car is guilty as charged therein."

Judge Siebecker's sentence was to the point, "...it is therefore considered by the court that said car be sold at public sale on 10 days' notice and the proceeds paid into the school fund...."

When Cecil Hoffshyster finally went to court on November 20, he was not represented by counsel. He entered a plea of guilty "without reference to the car described in said complaint." He was sentenced to jail for 90 days, and fined $100 plus costs of prosecution, amounting to $129.90.

Meanwhile, the car appealed to the District Court and was bound over to its owner on a $200 bond. On November 5, the appeal was denied, the District Judge ruling that he lacked jurisdiction in the case. Siebecker's decision stood. It seems the District Court would have nothing to do with the trial of a Model T Ford.

As for Howard Hoffshyster, it would seem that he got off without a criminal record —also without a car. Apparently, the liquor business became too much of a liability for him, as he went into another line of work, or so say District Court records. In 1928 the family enterprise was again in trouble, however, as Howard and Cecil were sent to the Nebraska penal complex in Lancaster County for hog stealing.

FOWL CHOLERA

Heavy waterfowl toll follows outbreak of disease, but captive flock survives

photo by Joe HylandTHE WORD "CHOLERA" alarms people even in this day and age when it is practically unheard of as far as humans are concerned. The people in south-central Nebraska were reminded of the disease during the spring of 1975, however, when a fowl cholera epidemic hit the area. Many of the state and federal wildlife agency people who worked with it will remember it as the worst tragedy to hit wildlife in many years. In less than two weeks, approximately 25,000 ducks and geese died in Phelps County.

Spring migration of waterfowl began as usual with the arrival of white-fronted geese late in February in the Holdrege area. Due to extreme drought conditions during the previous summer, the early arriving birds found many water areas completely dry or only a fraction of their normal size.

The lack of water is no major deterrent to early migrants stopping in Nebraska. They normally spend two to three weeks resting and feeding on the waste grains found throughout the countryside. Movement north from south-central Nebraska is normally triggered by the spring thaw in the Dakotas.

During normal years, the peak number of waterfowl exceeds 500,000 by late March, and a mass migration will see this number decrease drastically by the first part of April. This did not occur in 1975 because of abnormal spring blizzards, and cold temperatures kept most of the Dakotas and Canada under a blanket of ice and snow during the first part of April.

The delay in migration and the low water levels made the spring visitors very susceptible to any type of disease that would be present in the area.

Along with the waterfowl, a large crow population that was moving through the area was also delayed be cause of the bad weather farther north. They were roosting at night in the numerous shelterbelts on the state-owned, game-management area near Wilcox. The crows spent the day scavenging throughout the area, coming in contact with the waterfowl during the process. An estimated 10,000 crows were roosting on the state area.

All indications point to the crow as the culprit in the fowl cholera outbreak that developed. Sick and dying crows were first observed on the Sacramento Game Management Area about the middle of March.

The first sign of waterfowl losses occurred March 28 when one goose of the 270-bird captive flock on the Sacramento area was found dead. Three days later, one more bird was lost from the flock. Following a brief snow storm on April 2, reports were received of dead white-fronted geese on the Johnson Lagoon northeast of Holdrege. Further reports were received on April 5 and 6 of large numbers of dead ducks and geese on a marsh north of Funk.

On April 7, a thorough investigation was made of the water areas in eastern Phelps County. Initial losses at that time were estimated at over 5,000 ducks and geese. Veterinarians with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service were contacted to assist in identification of the cause of the die-off.

A Fish and Wildlife Service veterinarian arrived at the Sacramento area on April 8 and made a tentative diagnosis of fowl cholera at that time.

The first thing that comes to most people's minds when they hear the word "cholera" is —will it affect us, our children, our poultry or livestock? These were common questions from the public. The bacteria that causes fowl cholera primarily infects birds. It is not the same causative agent as in cholera that infects humans. Hog cholera is caused by a virus, this being completely different than the bacteria involved in fowl cholera.

Fowl cholera is a highly infectious disease caused by the bacterium Pasteurella multocidia. Both wild and domestic birds are susceptible to the disease, and waterfowl seem to be particularly vulnerable.

The disease has been recognized for nearly 200 years. In 1836 the term "fowl cholera" was applied to the disease because of its explosive onset and high mortality rate among such birds.

There is considerable literature pertaining to fowl cholera in domestic poultry, but as is true with most other diseases, very few reports of the disease in wild birds are available.

The first epizootic of fowl cholera in wild waterfowl was reported at Lake Nakura in Kenya in 1940. Five years later, wild ducks migrating through Holland died of the disease and were suspected of transmitting it to domestic poultry flocks. The first record of an outbreak in North America in wild ducks, occurred at the Muleshoe National Wildlife Refuge in Texas in February 1944, with a loss of 307 ducks. During the winter of 1948-49 approximately 40,000 swans, geese, ducks, coots and some shore birds succumbed to fowl cholera in the San Francisco Bay area. The Muleshoe Refuge in Texas was hard-hit during the winter of 1956-57 when more than 60,000 waterfowl died due to the disease. One of the more recent outbreaks occurring near Nebraska was at the Squaw Creek National Wildlife Refuge in Missouri. During one night in January 1964, more than 1,100 snow and blue geese died. At about the same time, 5,615 mallards were picked up, along with a few other ducks representing several species. Fowl cholera may have been responsible for a die-off of waterfowl on the Platte River in Nebraska near Overton in 1950 and again in 1964.

The Muleshoe National Wildlife Refuge in Texas and north-central California are the only two areas in the world that have experienced nearly annual outbreaks of the disease since 1944.

Data gathered in California indicates that there is no correlation between size of the population and number of birds that die, and the mortality rate does not vary by species according to body size.

It is not known how fowl cholera is spread in the wild. It has been theorized that among domestic fowl it is spread by ingestion; by insects mechanically, and by inhalation. In the wild, the disease is probably spread mostly by inhalation, although there is evidence of oral transmission from diseased carcasses to predators and scavenging birds. When an outbreak occurs in waterfowl, crows, gulls and hawks eat the carcasses and may spread the disease in this manner. Contaminated dead birds may remain infective for at least three months, and pond water can remain (Continued on page 33)

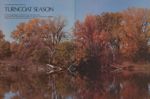

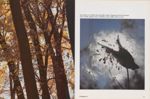

TURNCOAT SEASON

To hear grasshoppers sing these long, slow days away You would think the greening kingdom of summer could never conclude, Could never surrender such landscapes of life...

I remember how blackbirds sang their spring domains,

Dickcissles from the budded branches, meadowlarks

And bobolinks in every field crazed with courtship,

Flashing their plumage-flags to wake us from winter.

The earth is faithful to its rituals, and the warm ground

Sprang mushrooms, spiderwort, and adder's tongues.

Summer brought forth the industries of insects,

Deer wading grass at the woodland's edge,

Land and pond grown green with the genius of the sun.

Fruition is a difficult time. The good harvest

Casts long shadows forward, past the vireo's ease,

The waxwings and robins gorged on berries, beyond

Warm nights raccoons love best, bellied with crayfish.

You hear it in the crickets' and cicadas' singing,

See it in the sinking summer stars, the sun one morning

Displayed on gossamer laceworks, and shadows grow.

We are like summer itself, lazy in this lotus time,

Forgetting flint-sharp wind, the coming tyranny of ice.

Cotton woods know. Let grasshoppers now in October

Continue their days in pleasing, skipping songs...

I remember how blackbirds sang their spring domains,

Dickcissles from the budded branches, meadowlarks

And bobolinks in every field crazed with courtship,

Flashing their plumage-flags to wake us from winter.

The earth is faithful to its rituals, and the warm ground

Sprang mushrooms, spiderwort, and adder's tongues.

Summer brought forth the industries of insects,

Deer wading grass at the woodland's edge,

Land and pond grown green with the genius of the sun.

Fruition is a difficult time. The good harvest

Casts long shadows forward, past the vireo's ease,

The waxwings and robins gorged on berries, beyond

Warm nights raccoons love best, bellied with crayfish.

You hear it in the crickets' and cicadas' singing,

See it in the sinking summer stars, the sun one morning

Displayed on gossamer laceworks, and shadows grow.

We are like summer itself, lazy in this lotus time,

Forgetting flint-sharp wind, the coming tyranny of ice.

Cotton woods know. Let grasshoppers now in October

Continue their days in pleasing, skipping songs...

FAMILY HUNT

Traditions are forming each year for the Parkins and their kids. It means fun as a group, and memories for all their lives

Photo by Faye MusilWITH A SILENT CALM known only to the Pine Ridge, they came out from the canyons, and an evening fog settled on the canyon floors.

In a small hay field near Crawford, there was a time of celebration for the Parkins family as we concluded our deer season for 1974. It was Friday, November 15, and 7 of our children joined my wife and I in dressing out the 4 deer we had just tagged.

My oldest daughter, Esther, who had tagged her deer the first day, was in Scottsbluff where she had joined her classmates for a volleyball tournament.

Esther had downed her buck in the morning. I had positioned the family hunters, with the three oldest girls, my wife and myself, on overlooks at a natural passageway between canyons on the Peterson Wildlife Area near Crawford. As the deer moved toward daytime resting places, Esther had spotted her deer.

She only needed one shot. I was proud of her care, and grateful for the exacting train ing we had all taken before ever starting for our favorite hunting area —the Pine Ridge. That's one thing my wife and I stress —we don't like crippling.

Actually, the story goes back 11 years to my first hunting trip to the Pine Ridge. I was so taken with the rough buttes, the pines and the wildlife that I began taking my wife. We were cautious at first, but finally we decided that the entire family should share the experience. My wife, Esther, and I look forward to going each year so much, that we haven't missed a season —even when Esther was eight months pregnant with Catrina.

I hope our feeling for the rough, pine-covered country and the ranchers there will stay with my kids the rest of their lives. I think it really bloomed last year when we all came out here —even Catrina at 11 months.

We arrived just before the season opened and, true to form, everybody helped move into our cabin at Fort Robinson. I encourage that. I'd like to see more families living and working together like we try to do. If we can bring eight kids to the Ridge, surely other people could bring one or two.

It just seems to be a good "training" area for kids. It's a way for them to learn first-hand about death and how it's a part of life. They can develop a reverence for the death of an animal that very literally feeds them.

With a family as large as mine, everyone eligible for a permit applies. The three oldest girls, my wife and I have filled our permits two years running. We've been lucky. That's five deer—and it sure helps feed the crew.

But I'm rambling. . . With young Esther's deer in the bag, we still had four permits to fill. We hunted every day for a week. Finally, on Friday evening, I situated the girls, LeEtta and Rose, and Esther and myself, in a small hay meadow on private land near the fort. The landowner is a friend from years back, and is always an open-handed host when we ask to use his land.

As dusk settled, a small herd of deer walked through the meadow. When the smoke cleared, we had four more deer, each one a good, clean, one-shot kill. My family had done their part in providing for themselves. They had worked for months learning, shooting targets, and it had paid off.

As the rest of my children grow up, I sus- pect each of them will be eager to carry on our deer-hunting tradition.

Over our victory feast at the Fort Robinson restaurant — another budding tradition — we discussed our hunts, this year and last.

Six-year-old Gene probably enjoyed the hunt as much as I did. He's a pine cone smutcher. If there are 100 pine cones lying under a tree, he'll smutch 98. Probably has the fastest feet west of the Mississippi.

I think about a sunlit afternoon on "brushy point" as we call it. (Continued on page 42)

OUTDOOR ENCOUNTER

High schoolers planned a pleasant hike-and-camp session. Then a blizzard moved into Pine Ridge, trying their mettle and collapsing their tents

photos by Ted LannanPACKED IN A VAN like sardines in a can, we started on our adventure to Northwestern Nebraska. We learned the definition of adventure earlier than we had planned to on this trip —the outdoor encounter sponsored by the Game and Parks Commission and Nebraska Outdoor Encounter, Inc. The program's goals are to help high school students learn about the out-of-doors and themselves.

The leaders are old hands at outdoor survival. Their names are Gary Gablehouse and Ted Lannan. Both are special people, each in his own way.

Gary is pure professional — knowing what to do and when; but he was one of us, too. He was silly, and when he was happy and laughed he would get an expression that looked like ecstasy. He would cross his arms on his chest, throw back his head and laugh. We couldn't help but laugh with him and at him.

Then there was Ted! He's pudgy, loving, funny, kind and adorable. Everyone liked Ted; he was easy to get to know. When Ted laughed, like Gary, it seemed like the sun shown a little brighter. One of the boys said that Ted's stomach was one big lung used for his special laugh.

There were 16 of us under the leadership of Ted and Gary. I guess you could call us semi-novices; none of us had been exposed to the wilderness much. When we began our adventure we didn't know each other very well. We were shy, apprehensive and not sure what to expect.

March 23,1975Up at 7 a.m. today to pack the rest of our supplies and get ready to leave.

As we started to hike it was blowing so much that it was hard to walk straight. Besides being windy, it was cold, and while walking it felt as if the chill were going right through us.

We hiked approximately 21/2 miles to a campsite, which was located by a small, winding stream; the water was so clear that it looked like glass.

We set up our tents, although everytime we'd get them laid out and ready for staking, they'd start to blow away. We, of course, got them up with no major difficulties.

Several times the tent fell down, but each time Terry, (my tentmate) and I scampered out to set it back up. After about five times Brad brought us the end of a dead tree, or what looked like a tree, to use as a deadfall. We tied the end of the tent to it and it worked beautifully.

After lunch Bob, Brad, John, Lee, Kris and I took a hike to see what could be found. We followed the stream. It wound in and out like a vine. We followed it until we reached a pasture with three cows grazing. As soon as they saw us they turned and ran, never to be seen again.

While the guys climbed a bluff, Kris and I loafed in the pasture trying to catch the warming rays of the sun. I could have taken a nap but they were back in 15 minutes. On the way back, Lee and Brad went up the hills, and John, Kris, Bob and I went along the stream again. When back at camp we got into a poker game in wlpich we used gorp as chips. (Gorp is a mixture of peanuts, M&M's and raisins). The M&M's were worth 10, peanuts 5 and raisins 1. I was the first to lose. I guess I'm not much of a poker player, but I probably munched away more than I lost.

Our cook group prepared macaroni and cheese, which was runny like soup. Steve's cook group had fish, because during the day he had gone out and caught a couple. While we sat gumming our macaroni and cheese, we drooled over the aroma of Steve's fish.

We went to bed early, about 8 p.m., but didn't sleep in our own tent. We moved in with Kris and Mary to keep warmer.

March 24,1975We were allowed to sleep late today, although when the sun's up it's hard to sleep.

When we were all up and had eaten, Gary and Ted took us to a canyon for a meeting. They told us about hypothermia and how to watch for symptoms. Hypothermia is when a person's body loses too much heat and starts to shake. The cure is to administer hot liquids and warm the body —with the external heat of other bodies. There were a lot of jokes about who was going to treat who, but when it happens, it is such a serious situation that it has to be taken care of immediately. In the wilderness, the only thing that matters is survival.

We also talked about the 10-mile walk to our new camp. Gary said it would probably take 5 hours to get there. It was strange thinking about walking that far and it taking so long, because in a car you lose your concept of miles.

After the meeting we played several games. One was giving ourselves nicknames, then going around the circle and reciting everyone else's nickname. The game seemed to break the ice between us, and we all started to open up.

After our games, we broke for lunch. Terry, Brad, Mike and I lunched in the canyon. The weather was beautiful up there, no wind, sunny and warm. On the way back we met Steve, who told us that

among Kevin, Ted and himself, they had caught 12 fish. We would feast tonight.

When we returned, Ted and Gary were getting ready to make dinner, so we gathered around to help. We cooked the fish along with fry bread. Everyone stood around looking like vultures.

Tonight we took our insolite pads and sleeping bags and laid out under the stars. Ted pointed out some of them and Gary told us about some of the legends behind the constellations. Then we just laid in silence thinking. Because of the cold we didn't stay out long before we went to bed, but while we were there it was peaceful and pretty.

March 25,1975We were up early today gathering our supplies and getting ready to move out.

We broke into two groups, the As and Bs. My group, the As, went first, We walked about two miles before our first break. It didn't seem to take very long, and it wasn't tiring at all. We rested while we waited for the second group to catch up.

About five minutes after the Bs arrived, we were off again. Walking became automatic and paced after a while.

My shoulders didn't ache like they had on Sunday. It may have been that I was used to it, or that it was better packed today. Whatever the reason, I was pleased.

Every time we crossed a stream we would have to The definition of a mile took on new meaning, as did rest periods

When we reached our destination, we had walked about 7 miles. We originally were going to walk 10, but Gary said he could see we weren't up to it. When we reached the campsite we all collapsed on our packs. We just laid there like lumps for about 10 minutes.

After dinner we decided to have a dance. John played his harmonica while the rest of us did the Virginia reel. I think this helped bring us all a lot closer.

After that I felt more relaxed and open to the people around me. It was a good feeling. I think it was then when everyone started to really know each other.

March 26,1975Today begins our biggest adventure yet. We go out on solo; that is, spending a day and night by ourselves.

We again split into two groups. This time I was in the second group, but I was the first to get a campsite. It was the nearest to camp, but totally concealed. It was in a canyon with fallen trees criss-crossing every which way. It was a serene place, and I grew to love it.

The country was beautiful —so silent, so different from what I was used to. I scouted the area, and it soon became my territory. When I was out I would just stand and listen. I felt like I was the only living thing there.

It was the first time I had ever been alone, and the first time I had been in the wilderness. That's quite a combination. I felt like I wanted to see everything and do everything. It gave me a feeling of peace and serenity, and I felt a new and exciting love of life that hadn't been there before.

I explored everywhere and everything. I was fascinated by the simplest things. Fallen trees, for instance. I inspected every inch of them and wondered how and why they had fallen. It was strange because I usually don't pay attention to such things, but it felt good.

It started snowing in the afternoon, just a light, quiet snow which seemed to make everything even more silent and serene. It was beautiful.

In the evening I was swinging on one of the fallen trees when I saw Leonard walk by below me. I thought he was going back to camp. I went to the clearing to watch, but when I got there he was gone. I looked all around but I could not see him anywhere so I started up the hill to see if I could see him. I felt puzzled and intruded upon. I felt like a mountain lion who had to defend its territory from predators. It was the strangest feeling I have ever had.

When I reached the top I heard something move and then I saw Leonard climbing down the side of the hill. I just stood and watched. I didn't say a word. I felt betrayed but at the same time I felt I should talk to him. I didn't, maybe because I didn't understand what I was feeling. After that he went back to his own territory.

I went to bed about 7 p.m. and went right to sleep. I was awakened by Leonard in the night telling me his

tent had fallen down. I told him to talk to Gary and tell

him what had happened. I thought Gary should know

what happened and where he was. I didn't think about

him getting lost, but after he left I started getting worried

about him.

tent had fallen down. I told him to talk to Gary and tell

him what had happened. I thought Gary should know

what happened and where he was. I didn't think about

him getting lost, but after he left I started getting worried

about him.

After waiting awhile and not hearing him yell I figured he had made it safely. I hoped so. I went back to sleep but awoke again to find my own tent down. The snow had gotten deep but I had no problem getting it back up.

March 27,1975When it was light I awoke to find my tent down again. I pulled on my boots, coat and mittens and shoveled my way out to put it back up.

Besides being deep out, it was snowing harder and the wind had come up. I tried and tried to get my tent back up, but for the life of me I couldn't. I grabbed my sleeping bag and plowed my way to Gary's tent. It was pretty windy and terribly cold, so I put my sleeping bag over my head and kept going.

I opened the flap of the tent and Gary and Ted groaned when the snow blew in on them. They both decided to go get the others. Leonard and I stayed in the tent with Cheri. It was so cold that when I took off my socks they froze solid.

People came back one by one. Some put up tents while Gary and Ted were out getting the other people. Kris came back and we were lying in the tent until she decided she didn't want to listen to Cheri's complaining anymore, so we left.

It was blowing really hard and it was even colder. We helped John tie the last couple of knots on his tent, then we moved in with him.

There were still two out from camp. Gary and Ted were concerned about them as it was turning into what Gary called a "white-out". Both of them began the last trudge to retrieve the two, each holding onto a long tree limb so as not to get separated. They said that after about 10 minutes of nearly blind walking they heard a yell and then saw two figures coming toward them. They were so glad to see them that they yelled and screamed and hugged each other.

Bob got in our tent and Brad got in with Lee. We then had four in our 2-man tent and it was warming up fast. It was a little cramped but better than being out in the storm.

We cracked jokes, sang, slept, and talked to keep occupied. It was blowing really bad then, worse than I had ever seen.

The wind was blowing so hard that snow was com ing in the tent. We had to keep our heads under the sleeping bags to keep from getting wet.

During the day we played 20 questions, and the answers always turned out to be something like a heater, bath tub, helicopter or food. We quit, though, because we were afraid we would go insane if we did it too much.

We also noticed there seemed to be a lingering stench in the tent. It was us. We hadn't bathed in a week.

During the night Bob got a touch of hypothermia so Lee and I hugged him tight till he quit shaking. We also gave him handfuls of gorp to give him energy. Dur ing the night our spirits seemed to go down, but John tried to keep them up. I know he made me feel better.

March 28,1975We awoke to Kirby's voice telling everyone to get up and get ready to move out. We weren't sure the weather was good enough, but when we looked out the wind and snow had slowed.

Our pants and socks were at the bottom of the tent and when we found them they were covered with snow and partially frozen. We were hesitant about putting them on, but we had to if we were leaving. I was sure glad I had long underwear.

The drifts were high around the tent, not quite halfway up.

Surprisingly enough, it wasn't cold, I guess because we were moving. Several times we had to take off our packs and crawl because the snow was so deep. This technique distributed our weight over the crusted drifts.

We reached a hill which we had to slide down because the snow was too deep to walk. As I went I could feel the snow going up my pants.

At the bottom of the hill was a creek covered with ice. Gary crawled across, pushing his pack in front of him. As he reached the edge it cracked, but he scrambled across. Kirby went behind him and the ice broke. Luckily he didn't get wet. We put two logs across the stream and crawled across on our hands and knees.

Gary left Kirby behind to help everyone else across while the rest of us went on. From the stream it wasn't far to the line shack, but that's when I began to get tired.

When we reached the shack the door was locked so Gary had to break in. The room wasn't big but it was out of the wind and it had a stove. We unzipped the sleeping bags and laid them out like we had in the tent. Ted started the stove and we all got between the sleeping bags.

We had one bad case of hypothermia when we reached the shack. Ryan was blacking out and shaking. Gary had him get in the sleeping bag and had people get in with him. Mike also had a slight case of hypothermia; he was shaking a little. I think we were all dehydrated—that may have been why we felt funny.

We were just getting comfortable in our new home when someone yelled "truck, truck". Everyone bolted out the door and screamed and yelled. We were ecstatic to see the men and the snow cat.

We piled into the snow cat and rode into Fort Robinson, where we were greeted by a family who opened their home to us.

Mrs. Rotherham fed us sandwiches, fruit and hot chocolate, which we stuffed ourselves with. We acted like we hadn't seen food in a year.

The rest of the day we played cards, talked, ate and watched TV. I think we enjoyed being in civilization again. Later in the day we shampooed and showered.

March 30, 1975Today the alarm went off at 6:30, Everyone moaned with agony. Today was the day we were going home. Someone made a thank you card for the Rotherhams and everyone signed it. Then we were off, packed like sardines as usual.

Today was like the first day. We talked, laughed and cracked jokes, but most of the talk was about food. We all had a bad case of the munchies.

We reached the Game Commission about 9:30. We called our parents and said goodbye to everyone. It was hard saying goodbye. We had gotten so close and now we had to let go. We would never be so close again.

Long after this adventure is over I will look back with fond memories. This is something no one can take from me. It will be cherished, and when I am down I will think back and smile.

FISHING... RAISING WAX WORMS

ICE FISHING IS STILL several months away, but it's not too early to start making plans, especially where a winter bait supply is concerned.

Probably the most popular of all winter baits in Nebraska is the waxworm, an offering that's strong medicine on panfish when used in combination with the tiny lures of the ''teardrop" family.

Most fishermen depend on their local bait dealer to supply their winter needs, and this works out just fine, in most cases. But, in some areas, a bait emporium that stays open for the winter is somewhat of a rarity. Even shops with the best intentions of serving the winter angler often cannot obtain bait from their suppliers, and run short toward the end of the season. And sometimes, store-bought bait gets a bit expensive, particularly for the fisherman who logs lots of time on the ice. In all these cases, a fisherman with his own supply of waxworms would have an advantage.

Raising such a supply is somewhat involved, however, and only fishermen who use lots of waxworms each season, those who have a hard time obtaining bait, or those who simply like to tinker with an interesting project should get involved.

One thing might make the hassle more worthwhile in the long run, however. Once the process is underway, it can be repeated for several years with a minimum of trouble.

At this point, it might be appropriate to explain a few things about the waxworm. It lives as an unwelcome guest in beehives, laying its eggs and going through its life cycle there. Eggs laid in the hive soon hatch into larvae. These are the worms that fishermen want. After a time in the larval stage, living on comb and pollen in the hive, the worm spins a white, silky cocoon. There, the worms change to moths, emerge to lay eggs, and the cycle is continued.

Naturally, beekeepers do everything they can to eliminate these pests from their hives. However, a few colonies of waxworms are likely to be found each fall as the apiarist goes through the hives. If you contact a local beekeeper early, as suggested in our last issue, he might save some of the worms for your bait project.

The next step, preparation of diet that you will feed your worms, is where most of the hassle comes. The recipe used here will yield about three pounds of food, enough for about 1,500 worms. The diet will keep for several years, so it might pay to expand the recipe to take care of the next few winters.

The ingredients in the diet include:

pablum (or mixed baby cereal) brewer's yeast beeswax (fine shavings) honey 12 oz. 3-1/2 oz. 1-2/3 oz. 3/4 cup glycerine 3/4 cup water 1/3 cup ethyl ether 1 pintEThe ether rates special mention, since it requires cautious handling. First of all, it must be stored in a refrigerator. And, it should not be kept longer than the date indicated on the container.

But most important of all, it should not be opened or used indoors or near any kind of flame. Its vapors are harmful if breathed, and are extremely explosive. You might have gotten away with using gasoline carelessly, but you will not be so lucky with ether. On the other hand, if handled outdoors in a responsible, adult manner, it should be no trouble.

Some of these ingredients sound a bit exotic and hard to come by, especially in smaller communities. However, there are sources available almost everywhere, though they might not be readily apparent.

Of all the "makins" in the diet, the ether will probably be the toughest to come by. However, many taxidermists use ether to remove fats from the skins of the animals they mount, and they might be willing to share their supply or help you obtain some for yourself. Drug stores might have some, and many veterinarians keep ether on hand to anesthetize the animals they treat.

Brewer's yeast is not a common item in most households, but it should not be too hard to come by. One source would be the local drug store, and health food stores stock enriched yeast for human consumption. The latter form might cost as much as $3 per pound, but that would provide enough for about five batches of the diet.

Glycerine is available in drugstores for about $3 per pint; enough for several batches. Beekeepers and honey processors would be the obvious sources of both the beeswax and honey. The wax can also be picked up from a hobby store (be sure to specify genuine beeswax), where it is sold for use in leathercraft for about 50 cents a cake, or in an archery store where it is sold for use on bowstrings. Honey can also be bought in a grocery store, as can the baby cereal.

To make the diet, thoroughly mix the pablum and brewer's yeast in a large, (Continued on page 42)

Prairie Life/ Bats

BEFORE THE COMING of the white man, prairie mammals were abundant and often gathered in groups so large that they defied description. Herds of bison extended from horizon to horizon, and prairie dog towns of a hundred miles in width were known. The day of these vast congregations of bison and prairie dogs has passed, but one group of prairie mammals still numbers in the hundreds of thousands.

They go unnoticed, not only because they are smaller than the bison and the prairie dog, but because of their habits. They hunt for food by night, and during the day- sleep in quarries and caves, trees, and the attics of barns. These abundant, but obscure, mammals are the bats.

Maligned and misunderstood, bats are the subjects of old-wives tales and folklore. They are the bloodthirsty, disease-ridden "vermin" that get tangled in your hair if you trespass in their domain. Actually, there are no "blood-drinking" vampire bats in the United States. Though bats are occasionally carriers of rabies, they seldom transmit the disease to humans because their living habits isolate them. Far from being "vermin", they actually render man a service by consuming vast quantities of insects each night. And, it is doubtful that a bat would ever become tangled in your hair, even if you placed one there.

In a prairie/plains state like Nebraska, a dozen species of bats are known to occur. All are insectivorous, and their diminutive stature is hardly threatening. The Eastern pepistrelle weighs a scant one-sixth of an ounce, and the hoary bat, Nebraska's largest, weighs only an ounce. Like gliders, though, they have a great wing surface for their weight. The hoary bat may have a wingspan of 16 inches.

Bats are mammals; the only true flying mammals in the world. They are covered with dense coats of fur, are warm blooded, bear their young alive and nourish them with milk. Though fossil evidence is sketchy, it is believed that they share ancestors with today's shrew and hedgehog.

The eyes of Nebraska bats are small, pinhead-size specks that function primarily in distinguishing night from day. Since bats are about during the dark hours of the day, a sophisticated echo-location system has supplanted the eyes as a means of interpreting the environment. The ears of bats are the "receiving" mechanisms and consequently are large, funnel-shaped, and generally very mobile. Most bats have large mouths and up to 38 multicusped teeth specialized for crushing the chitinous skeletons of their insect prey to a pulpy consistency.

The feature that makes bats unique among the mammals, though, is the wing. Bat wings possess most of the bones found in other mammal limbs, but they are specialized to accommodate flight. The upper arm is shortened, the forearm is long and slender, and the wrist bones are reduced in number. The thumb bears a claw but otherwise is not greatly modified. It is the bones of the fingers that have undergone an extensive change. Each of the digits is greatly elongated to provide the wing's framework.

The wings are simplistic, being essentially two layers of skin stretched over the finger bones. Only enough muscle to pucker the wings when they are folded and to support the blood vessels, is found between the skin layers. The upper arms and forearms are often furry, probably to help conserve heat when the bat is roosting.

The flight of an insectivorous bat is erratic. Even when hunting over a pond or in a clearing where there are few obstacles, they zig and zag constantly. Each sideslip, dive and rapid braking indicates pursuit and usually capture of an insect. Long flights, such as migrations or travels between roosts and hunting grounds, are straight.

Most of the larger bats in Nebraska, such as the red bat or the hoary bat, are solitary and roost alone, often in trees. Smaller bats, those half dozen "little brown bats", are colonial roosters and generally seek a diurnal retreat in caves, rocky crevices, buildings or even storm sewers. They leave their daytime roosts at dusk and immediately begin to hunt for insects. Before bats leave the roost they are restless, busying themselves with preening and, in the case of colonial species, bickering with neighbors. Bats roosting in old limestone quarries may limber up their wings by flying in circles before approaching the entrance. Often these preliminary flights grow in number until hundreds of bats are milling about inside the quarry. These group flights probably arouse heavy sleepers and synchronize the daily patterns of the colony.

While passing the exits of the quarry, they decide whether or not it is time to emerge and hunt. On overcast days the bats will leave their roosts early. Bats in caves that face away from the setting sun are active earlier than those in caves facing west.

Insects are abundant at night and nocturnal predators are few. Nighthawks are essentially the only night-flying insectivorous birds, and spider webs are the bat's only other competition. To capture flying insects at night, predators need a means of locating their prey other than by sight. The echo-location system of the bats has given them a near exclusive ticket to an ample meal of evening insects.

Echo-location is a sophisticated system that man has only recently copied in the form of sonar. Depending upon the species, sound waves are emitted from either the nose or the mouth. These waves strike an object, are bounced back, received by the ear and interpreted by the brain. The amazing feature of echo-location in bats is that hundreds of objects —their size, shape and distance —are all being computed at the same time. Information about the bat's environment is detailed enough and timely enough to allow them to fly through a maze of obstructions unerringly.

Bats are difficult to see after dark, so little is known of their hunting habits. Insectivorous bats, like insectivorous birds, have favorite hunting areas and utilize specific niches in the same environment. The altitude at which a species feeds coincides with the altitudes of their preferred prey. And, as with birds, particular species of bats have evolved specialized flight structures to best exploit their particular niche. Bats that capture insects close to the ground, where vegetation is thick and the odds of collision high, usually have shorter wings permitting slower, more controlled flight. Spe

cies of bats that feed at or above tree-top level, usually have wings that are

longer and more slender.

cies of bats that feed at or above tree-top level, usually have wings that are

longer and more slender.

The sonar systems of bats are likewise specialized. In complex environments, as in a woodland, the exclusion of sound waves bouncing off distant objects is desirable to simplify interpretation of the bat's near surroundings. Thus, bats that hunt these areas emit short pulses to minimize the number of signals being bounced back. They have, in effect, restricted their area of awareness by turning off their senses to all but the immediate environment.

Most bats will take a wide variety of insects ranging in size from the diminutive gnat to large moths. Small insects are probably captured in the mouth and simply swallowed, but larger insects are fielded in the wings, shifted to the interfemoral membrane between the tail and legs, and then grasped by the head and consumed at leisure while on the wing or on a night roost. Undesirable parts of the insect, such as the wings, are discarded. Sometimes insect parts are stored in the cheeks to be chewed and swallowed later.

Over short periods of time, some bats are known to capture and eat as many as two insects per second when the supply is abundant, but a more representative figure would probably be 15 to 20 per minute. The little brown myotis, a species common to Nebraska, weighs only one-fourth to one-third ounce but may take as many as 150 large insects or 5,000 small insects per hour.

If insects are abundant, a bat may finish feeding within an hour or two. Some bats will return to their diurnal roosts and not emerge until the following evening, but many will hang up in a nocturnal roost, a tree or ledge, to rest and sleep until their food is digested. Heaps of guano are often found under such night roosts, as bats have the habit of voiding their bodies to lighten their flight load before leaving. Some bats return to their day roosts after resting, and others will feed again before returning. Seldom does a bat remain out after dawn.

Understandably, little is known of the social life of bats. Mating is pre- ceded by a period of courtship that brings together receptive females and available males. In the temperate zone of North America, most female bats have a single estrous cycle per year. Generally, this cycle occurs in the fall, just prior to hibernation, and lasts for one or two months. During this time the ovaries produce one or more eggs. Males become sexually active during the same period.

Bat courtship has only rarely been observed in the wild, but some details have been revealed by captive ani- mals. Courtship and mating probably occur at the daytime roosts. Colonial nesters have no difficulty meeting suitable mates. It is not know how solitary bats locate one another during the courtship period.

Once together, the male approaches the female, crooning his peculiar buzzes, chitters and purrs. The male probably gestures with his wings. Some observers have reported that the couple seems to embrace with wings and forearms. Copulation is brief and the pair separates immediately after, never to meet again.

Fertilization does not occur at the time of mating; rather the sperm is held in the female's body for several months. In later winter, it is released to fertilize the egg, and approximately four months later the young are born. Most species have a single young, but some larger bats may have twins. The infants will weigh about 20 percent of the female's weight.

Immediately after birth, the young attach to one of the mother's nipples and she thoroughly grooms the infant. In some species, the female will carry the young with her until it is old enough to fly on its own, generally at about six weeks of age. In other species, the young are left at the roost and the female returns frequently to nurse. Young bats roost with their mother until they become sexually mature at the age of one or two years, depending on the species.

Mature bats generally segregate by sex. Researchers have discovered no social structure among North Ameri-

Most bats of the United States are capable of hibernation. Rocky overhangs, caves or just about any crevice are suitable winter resting places. Generally they seek sites where the temperature will stay a few degrees above freezing. Once in hibernation, their body temperature lowers to that of the environment and they live off the thick layer of fat that they acquired in late summer. If the temperature should drop below the bat's minimum range, more stored fat will be burned to raise its body temperature. While hibernating, they are helpless and require 15 to 30 minutes to warm up sufficiently to fly.

Most small animals do not live long, but bats are an exception. Individuals of many species live 10 years or more, and there is a record of a little brown bat living for 24 years. The near absence of natural enemies and their prolonged periods of winter stupor are probably important factors in their longevity. And, because survival is high, the rate at which they reproduce is not as high as other small mammals. Consequently, most species of bats are slow to recover from drastic population declines.

As with many species of animals, though, the bats are threatened by man and his manipulation of the environment. Because they are predominantly insect feeders, bats, like insectivorous birds, are vulnerable to insecticide poisoning. By feeding on thousands of insects each night, they concentrate the sublethal doses that their prey carry. Most people would not notice if bats were to completely disappear from the earth. They would simply apply extra insecticide to ward off the additional swarms of mosquitoes that the bats formerly helped to control. Ironically, that would be like mourning the dead with an additional dose of the poison that killed them. £2

DRESSING GAME BIRDS

Here are some kinks used by old hands to make processing simpler. Picking ducks becomes mere task by eliminating tedious finish work with use of paraffin to extract most feathers

Photos by Greg BeaumontSMALL GAME AND birds are generally not a problem to field dress and clean for the kitchen, but there are some kinks which make the job easier, faster or neater.

When working with birds, the job is easiest if they are skinned, but some waterfowlers absolutely refuse to remove the skin, insisting upon picking. For roasting, of course, it is desirable to leave the hide on. There are arguments for taking it off before cooking, also, but it is a matter of personal taste. Skinning is the easiest and fastest, with the first step being to cut off the feet, and wingtips, leaving the head for a handle.

Generally, pheasants, doves and grouse are skinned, but it is a tossup on quail. Turkeys and waterfowl are usually picked. Even this takes only a few minutes longer except for the fine hairs and pin feathers, which must either be singed or taken off with wax.

Another important step on turkeys and pheasants is removing the many tendons in the legs, which makes them more pleasant to eat. About the only way this can be accomplished is to break the leg bone just above the "ankle" joint by either bending over or crushing of the bone. Then, grasp the lower leg with big pliers or vice grips and give a mighty pull. This should extract all the tendons in one motion, leaving a mighty tidy drumstick.

Next, make an incision somewhere on the breast so that the fingers can be slipped under. Then, simply pull in any direction that is convenient until the carcass is bare. Gutting is then a simple task, as the cavity can be fully exposed and cleaned out. The heart and liver, and gizzard, can be saved if desired, and the animal can then be cut up or left whole.

On pheasants, a neat trick to dismember is to make an incision on either side of the neck, then insert the thumb down behind the crop while grasping the head in the other hand. Pulling in both directions will then split the bird, keeping all the entrails intact in the body cavity, yet easily accessible.

One point which should be brought up is that the entrails of game animals should not be fed to dogs, but should be buried or burned immediately after cleaning. It is not uncommon for many wild critters to carry various types of parasites, many of which are located in the intestines. Rabbits, for example, more often than not are hosts to in- testinal worms, and feeding raw entrails to a dog will quickly pass them on.

Normally, any disease or bacteria is destroyed by cooking, so that the animal can be eaten without worry. Serious contamination, however, usually repulses the hunter, and the entire animal is discarded. This is advisable with obvious abnormalities, such as a badly discolored liver or if the animal is extremely emaciated. These are indications that something is amiss.

Many hunters have never encountered anything wrong with any game they bagged, and it is unlikely that any danger exists in most game. It just pays to be careful and observant when cleaning wild or domestic animals. If it appears healthy, there is nothing to fear. In most cases, a seriously stressed or diseased animal will not be bagged because it will not be in a condition to be running or flying.

It is also advisable, especially with rabbits, to wear rubber gloves when cleaning, especially if you have cuts on your hands. If impossible or impractical, at least wash thoroughly immediately afterwards.

FISHING...WAX WORMS