NEBRASKAland

September 1975

NEBRASKAland

VOL. 53 / NO. 9 / SEPTEMBER 1975 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Fifty cents per copy. Subscription rates $5 for one year, $9 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Single Copy Price: 50 cents commission Chairman: jack D. Obbink, Lincoln Southeast District (402) 488-3862 Vice Chairman: Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 2nd Vice Chairman: Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-Central District, (308) 745-1694 Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-central District, (308) 452-3800 H. B. "Tod" Kuntzelman, North Platte Southwest District, (308) 532-2982 Director: Willard R. Barbee Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, Jr. Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree Staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: Jon Farrar Greg Beaumont, Ken Bouc Contributing Editors: Bob Grier Faye Musil, Tim Hergenrader, Roland Hoffmann, Bill Janssen, Ben Schole Art Director: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1975. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska Contents FEATURES HOOKED ON WHISKERS 8 DOVES A NEW CHALLENGE 10 FISHING ... BIG GAME AT BIG MAC 12 POLING FOR FROGS 16 THE PRONGHORN ANTELOPE A special 18-page color feature studying this fleet prairie animal, his lifestyle and his hardships 18 THE GAME'S THE THING 35 THE AMBUSH TREE 36 PRAIRIE LIFE/SEASONAL CHANGES 38 DEPARTMENTS SPEAK UP 4 TRADING POST 49 COVER: Among the joys of boating and fishing is watching sunshine and sunsets on a quiet stretch of water, in this case, part of the Tri County Canal system near Cozad. OPPOSITE: Of delicate beauty and craftsmanship, yet with a function as grisly as a hangman's rope, the spider's web is truly a marvel of nature. Photos by Greg Beaumont.

Speak up

Healthy FalconsSir / My co-workers and I have published several scientific articles on the status of the prairie falcon, including most recently two papers dealing with chlorinated pesticide poisoning.

The prairie falcon does not appear to be significantly involved in the DDT-egg shell thinning syndrome that has severely limited the productivity of some other raptors. Of course DDT residues can be found in nearly all prairie falcon eggs, but the levels are usually low, and rare indeed is the eggshell that is less than 90 percent of normal thickness. There is evidence, as yet inconclusive, that eggshell condition is better than in the 1960s. In Alberta, Canada, local problems with mercury compounds used as fungicides in grain, and industrial pollutants called polychlorinated biphenyls, seem more pre valent now than a decade ago. However, their effects on this species are not apparently widespread.

If anything, reproductive performance has increased since I first studied prairie falcons in 1959. In 1973 for example, 37 eyries in Colorado fledged about 100 young, which is near the maximum possible in terms of clutch size.

It is very difficult for conservationists to accept the condition that a large falcon population can be healthy after all that has been said about the risks to raptors from chemical pollutants. For the prairie falcon, many of the supposed risks have just not been realized.

Inadequate information or erroneous judgments were made when this species was considered "threatened" (listed in the Department of Interior's Threatened Wildlife of the United States). Regardless of its official status, it seems clear that limited use of prairie falcons by falconers in the region is not unwarranted.

James H. Enderson Professor of Biology Colorado CollegeProfessor Enderson wrote this letter in response to a previous exchange between Joe Shown of Elmwood, a falconer, and NEBRASKAland. At that time, the federal listing was quoted, and it stated that hard pesticides, and the practice of falconers taking young, may have been factors contributing to the decline of the prairie falcon. Apparently the status has been changed, and certainly "conservationists" are as elated as anyone about the relatively good status the prairie falcon is enjoying. Also, we are certainly not opposed to any form of legal hunting which doesn't hurt the resource. It would be fantastic if all species of wildlife could be maintained at maximum levels. Hurrah for the prairie falcon. (Editor)

Writer WantedSir / I hope you can help me with one of my biggest wishes. I want to write to an Indian boy, 15 to 18 years old. I can't write so good English but I can learn it better. My interest is everything. I'm a scout, YMCA. I'm 16V2 years old and 125 mm high and have light hair. Thanks.

Ola Molvar 6030 Landevag NorwayYoung Ola also included a P.S. which I am yet to make out, but he sounds like an excellent pen pal. The above address appears to be all that's necessary, so here's hoping Ola gets his much desired letter. (Editor)

Kids for WildlifeSir / The Nebraska Game and Parks Commission had teachers' kits available for National Wildlife Week on March 17-25 this year. Among the schools that request ed and used them was Burwell Elementary School at Burwell. The deer, turkey, pheasant and duck populations in this area bordering the Nebraska Sand Hills have always made the people around Bur well aware of how important wildlife habitat is. But this year the teachers and stu dents made everyone more aware of it by using all the materials in the kits given out by the Game Commission. Children were sporting badges all week, posters adorned the walls of the halls and classrooms, encyclopedias were being avidly read as each 5th and 6th grade science student reported on one species of wildlife. Beautiful collages of wildlife lined the walls around science teacher Dan Woeppel's room.

The Burwell teachers feel the National Wildlife kits are a very worthwhile project for the Game Commission to sponsor, and hope the kits will be available again next year.

Iryne Kapustka Elyria, Nebr.We thank you and the wildlife thanks you. Any additional awareness of the need for habitat is important and helpful. And, we do plan to have the kits available next year. (Editor)

Ruthless KillerSir / In your January issue on page 6 you had a picture of a man out shooting squirrels just for the sport of it. Don't you see this is too cruel a sport, as it is a useless killing?

It seems we have a very sick group of people who enjoy killing animals merely to satisfy their own egos or have nothing better to do. Everyone should be angry about such a senseless waste, especially when they harm no one. Also, the prairie dogs as there are so few of them left today; also the cute squirrels.

"If Nebraska is a ecologically state why do you allow this to continue".

Please put the pressure on government representatives and more importantly on the people who get their kicks out of killing animals just for the hell of it and leaving them dead or near dead. Please stop this!

Mrs. Dewey Ingle Denver, ColoradoWe are definitely against any senseless killing, but the hunting of squirrels, or any other game animal, is far from senseless, and far from cruel. There is apparently some confusion in your mind about the balance of nature and the operations of ecology, etc. Hunters do not cruelly at tack defenseless animals and leave them lying in a heap. Hunting seasons are, as we have explained for years, a sensible and legitimate method of harvesting a surplus of animals which nature provides each year, or in most years. Many people have been totally spoiled by the easy life in America, and become so dependent upon the super market they don't realize that everything we eat must be killed, whether animal or vegetable. The next time you go to the store for something as unnecessary as a cute chicken or a cut of cuddly pig, think about the "cruel" person who would kill that animal for you to eat. (Editor)

The State Fair, Aug. 29 thru Sept. 7

Nebraska's Grow & Tell Show

Friday, August 29

Captain & Tennille

Saturday, August 30 (Featuring the Imperials)

Gospel Night at the Fair

Sunday, August 31 (Freddie Prinze & Jack Albertson)

Chico and the Man

Monday & Tuesday, September 1 & 2

Roy Clark

Friday, September 5

The Osmonds

Saturday & Sunday, September 6 & 7

Roger Miller/Lynn Anderson

SAVE TIME & STEPS BY ORDERING TICKETS IN ADVANCE.

Ticket prices: The Osmonds, $6.00 & $5.00; all

other Grandstand shows are $4.00 & $3.00.

Orders should be mailed soon to insure best seats.

Ticket order form available by writing to:

(send stamped & addressed envelope)

The Nebraska State Fair, P.O. Box 81223,

Lincoln, NE 68501

Tickets also available at all Brandeis ticket counters

in Lincoln & Omaha. (Phone orders accepted).

The State Fair, Aug. 29 thru Sept. 7

Nebraska's Grow & Tell Show

Friday, August 29

Captain & Tennille

Saturday, August 30 (Featuring the Imperials)

Gospel Night at the Fair

Sunday, August 31 (Freddie Prinze & Jack Albertson)

Chico and the Man

Monday & Tuesday, September 1 & 2

Roy Clark

Friday, September 5

The Osmonds

Saturday & Sunday, September 6 & 7

Roger Miller/Lynn Anderson

SAVE TIME & STEPS BY ORDERING TICKETS IN ADVANCE.

Ticket prices: The Osmonds, $6.00 & $5.00; all

other Grandstand shows are $4.00 & $3.00.

Orders should be mailed soon to insure best seats.

Ticket order form available by writing to:

(send stamped & addressed envelope)

The Nebraska State Fair, P.O. Box 81223,

Lincoln, NE 68501

Tickets also available at all Brandeis ticket counters

in Lincoln & Omaha. (Phone orders accepted).

Early season catfish outing proves lonely but productive as channels take bait and run. Finding holes is main key to fast action, but landing fish gets tricky

SPRING WAS ALIVE and well along the river. The dead, brown rushes of last year had been replaced by the vibrant, waving fronds of green cattail shoots. Overhead, large pelicans moved with the grace of wind blown clouds, lower and lower until they touched the water and appeared as Egyptian sailboats resting in the river's shallows.

The sights, sounds, and freshness of spring were soon out of mind as a sharp tug on my line brought my attention back to the slow-moving water and the fish somewhere downstream that had found the bait.

Again, two sharp tugs at the rod tip, followed by the solid pull of a good size fish carrying the bait down stream. Setting the hook wasn't necessary, and the fish struggled as i strained to change his course against the current's movement.

The fight was as short as it was violent, and the snap of the breaking monofiliment line was like a bell, ending round one in favor of old whiskermouth.

"ICALURUS PUNCTATUS, whitish below and on sides, bluish on back, sides with small irregular spots. Reaches a weight of over 20 pounds. Great Lakes and Saskatchewan River southward to Gulf and Mexico...."

All of the above and more, the channel catfish meets all the requirements for top-notch gamefish status. Fine of flavor, excellent fighting ability, numerous in Nebraska waters; the channel cat has it all; all but good looks and public acceptance.

Eight species of catfish call Nebraska their home. Easily recognized by their flattened heads and long, whisker-like barbels, nothing else quite matches the homeliness of a freshly caught catfish. Even the me tallic protection of scales common on other species of Nebraska fish are missing; replaced by sleek skin.

Yet with all his attributes, the catfish is for the most part spurned when fishermen gather to speak of the walleye's spawning run, or the striped bass's line-break ing capability. Many is the time I've answered requests for fishing information with a question: what do you think of catfish? In most cases, I'd end up providing in formation on other fish activity going.

Fortunately, this lack of interest by the fishing community makes a day spent on the river in pursuit of cat fish a solitary pastime, without the fishing pressure of the lakes or ponds.

Each spring, Lake McConaughy's upper end and the Platte River that flows into the irrigation impoundment at that point, are the center of attraction for a knowledgeable group of catfishermen waiting for the ice to thaw, and for the subsequent migration-like move ment of hungry catfish.

Not about to admit defeat after a short, first-round setback, I dipped into the tacklebox for a new hook and split shot to refurbish the broken line. The easy part of tying the knot and cinching the splitshot with a bite gave way to the less enjoyable task of baiting the hook.

Cats go for strong-smelling baits, with the entrails of the gizzard shad the most popular fish producer on the Platte. The best method of transport for the ripe entrails is a small glass jar, with a tight fitting lid. A large rag and a washing in the nearest water completes baiting chores.

Before setting up along the grassy river bank, I'd moved up and down the shore, using the rod tip to find the deeper holes that currents cut from the sandy bottom at almost regular intervals. Any place more than half a fishing rod deep is a likely lurking place for catfish.

Moving upstream from a slow moving eddy, I prepared for round number two.

Another advantage of the catfisherman is the wide assortment of equipment that can be used. Mine was an open-faced reel loaded with eight-pound-test monofilament. Perhaps I'd come over-equipped, as a school boy armed with a cane pole and strong braided line would have landed my first-round adversary.

Casting the bait downstream, I let it drift into the deeper water. To forgo the loss of another fish, I light ened the drag on the reel. The bait had hardly settled when a series of light taps brought my response, a sharp neck-snapping guaranteed to get the attention of the feeding catfish. The pull seemed to do the trick, and a battle similar to the first progressed, with the fish rolling on the surface, flipping end for end out of the water, but again, I felt the sickening slack on the line that meant the loss of round two.

This time the hook remained attached to the line; even the bait remained as if nothing happened.

To coin a pun, my problem seemed to be a reel drag. In the first round, the drag was set too tight and the fish broke free. The (Continued on page 50)

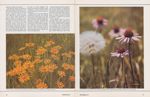

DOVE... A NEW CHALLENGE

Top U.S. game bird is back on the shooting agenda, but hunters must sharpen up and "shape up"

IN JUNE OF THIS year, a seven-man board of Game and Parks Commissioners sat down in public hearing to consider recommendations which would establish hunting regulations on the mourning dove.

Public hearings on this topic had not been heard in Nebraska since 1952 when the last season and bag limits were set on this aerobatic fool maker. The passage of LB-142 once again proclaimed the dove a game bird, indicating popular public sentiment for reviving a long-lost Nebraska sport.

But 23 years of idle bird, watching has produced a new generation of hunters. Hunters who can only reflect back on dove hunting, second hand, from the stories told by fathers and uncles. And this is a generation of hunters anxious for first-hand proof that the mourning dove is truly a game bird of extraordinary quality, and that the stories told were not jaded with exaggerations often produced from tales of the good old days.

Those presently under the age of 23 were not yet born when the final legal shot was fired at a fast winging evening dove, and those presently under age 33, unless they started hunting at an age younger than 10, were probably not among those with scattergun concealed between a dead tree and a dove-frequented watering hole.

Streamlined features and sleekness best describe the overall conformation of the mourning dove. Its total length varies from 11 to 13 inches. Wings long and pointed with narrow tail allow it agility and speed which has made reloading popular or even necessary among dove hunters. The neck is long and protruding, which at tached to a comparatively small head, has resulted in its colloquial name of "turtle dove".

Males are almost identical to females, with slight coloration variances providing the primary distinguishing characteristics. From afar, not much more can be said about the color of the dove other than that it's gray. But up close, under careful observation, the male of the species is a rendition of delicate beauty. Colors combined in gentle plumage run the spectrum from olive brown to bluish-gray. Finishing touches of art are added by a black cross-bar punctuated with a white tip to the tail. The head is predominantly fawn brown topped with a bluish-gray crown. Reflected sun 10 light from the iridescent neck feathers produces a purplish, metallic bronze and gold.

The breast and other underlinings are purplish buff with a paler throat, tail and underwing.

The similarly marked female is drab with duller colors, and she lacks reflected brilliance. The legs and feet of both sexes are red.

The mourning dove is a familiar nationwide resident, and has the distinction of being our only game bird to commonly nest in all 48 mainland states, with occasional housekeeping in Alaska.

The mourning dove, unlike other species of game birds, have thrived on progress, agriculture and the conquering of wilderness. Clearing of vast forests greatly increased its habitat and population, and the bird can be found setting up residence in suburbs of large cities, but it is more common to farm folk. Its remarkable ability to adapt to changing land cover suggests stable populations will continue, and with an increasing human population, doves have readily learned to live in close association with man.

Man's created environment is often times to the liking of this game bird, as orchards, front yard landscaping, ornamental hedges, and windbreaks have provided it with excellent nest ing sites. T.V. antennas are often frequented by resting doves.

And what about nesting and brood rearing. This is important knowledge for hunters, as propagation of the young insures future harvests and a continued sport. Concerned hunters simply don't forget about the welfare of game at the final sundown of the season, but consistently support habitat and conservation programs through money and effort.

The nest is crude, and loose construction supports the customary two squab brood. The majority of nests is found in trees. Most are constructed at low altitude, with some found directly on the ground or in fallen trees. When both eggs are balanced precariously on a few interwoven dry sticks provided by the male, the female is ready to incubate, and hatch ing occurs 14 or 15 days later. The male practices very little chauvinism, as he spends equal time in the incubation process. Like clockwork, the male takes his place warming the small white eggs approximately from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. and then exchanges places.

Nesting is generally underway by some birds in April in Nebraska and builds to a peak by June to slowly diminish to only a few nesting pairs in September. From 2 to 5 nesting periods are possible, depending on climate and location, with a possible maximum yearly brood yield of 10 squabs per pair.

The total time for brood rearing is about a month, including egg laying, incubation, and care of the squabs until they leave the nest. If a nest is destroyed, renesting begins immediately, and in some instances the same nest will receive new eggs, thus saving time.

Dove shooting is a sport of its own, carrying distinctions not typical of any other game bird. It is an exacting sport, and can bewilder the finest shots, as many loads of No. 8's never quite catch up with a fast moving dove.

Its distinction gives the sport many variations which can be tried and tested in the field until the most successful and rewarding approach is matched to the individual preference of the hunter.

Doves are a migratory game bird, and therefore hunting of them must fall within a framework established by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The Federal agency has provided state conservation agencies with a maxi mum season length of 60 days which must fall after September 1.

The Commissioners, after considering the recommendations of game biologists and public input, decided to open the season September 1 and extend it for 30 days until September 30. They provided for a bag limit of 10 doves and for a possession limit of 20.

Shooting time will be 15 minutes before sunrise to sunset. The legislature amended LB-142 with provisions that would make road ditch hunting of any game species illegal, and the lawmakers also added that birds must be taken by shotgun, and on the fly.

Perhaps the most challenging, and consequently the most popular method of hunting by the experienced dove hunter, is the practice of pass shooting. Because mourning doves rarely fly high enough to be considered out of range, any location be tween "points of need" for the dove will serve as a pass shooting site.

Find a favorite feeding area, observe NEBRASKAland the direction that the majority of birds are coming from, obtain per mission, and you're in business. Best feeding areas are wheat stubble fields, or other waste grain or weedy fields located within a mile of trees in shelterbelts, wood lots, or creek bottoms and river land.

Shooting should be best in such a situation early in the morning and late in the afternoon; however, some opportunities may be available throughout the day.

Other areas which serve the daily needs of the mourning dove and provide additional areas for a pass shoot ing experience include watering places and favorite gravel supplies.

A third method of hunting doves, favored by many, is the practice of shooting near water holes, Targets are incoming at varying degrees and speed. Doves will zig when they should be zagging or they may virtually stop in mid-air from a speed of 50 to 60 miles per hour. Shooting over watering areas may be most rewarding following a morning or eve ning feeding period or on hot days in dry weather. Dove decoys sometimes add to the flavor of the hunt, as fall migratory mourning doves are flock ing birds, and are generally attracted by decoys.

Doves are attracted to the roads in large flocks, as hunters will discover. Pass shooting will be a frustrating experience for the veteran hunter as well as the novice on the first few trips of the season. Experienced dove hunters advise those who are having trouble connecting to make yourself lead much farther than your instinct tells you. You might find that proper lead has been the main cause of your misses.

Another dove hunting technique compares closely with that of hunting other upland game birds. Jump shoot ing doves out of a harvested weedy field or narrow tree planting will mean more footwork than pass shoot ing, but will provide an interesting challenge. Jump shooting doves can be compared with hunting species such as sharptail grouse and prairie chicken, pheasants, and quail.

The jump shooters will find an in teresting variety of shots ranging from out of range to those virtually flushing from under foot. Jump shooting is a productive method of dove hunting during the heat of mid-day when the birds seek the shade of weedy growth or trees.

SEPTEMBER 1975However, road hunting should not be considered a fourth method for taking doves. Besides being unnecessary, road hunting is illegal. Laws covering trespass, shooting from the road right-of-way, and loaded shot guns in a vehicle make legal road hunting virtually impossible. Hunters can use the presence of large concentrations of doves along the roadways to their advantage, however. Such concentrations indicate that doves are using a nearby field or pond, and after receiving permission, good dove shooting may be in the offing.

Energy minded hunters will only use their vehicles for transportation to a hunting location. And, how does man's best friend fit into his master's new outdoor adventure? Does a dog work well on doves? What type of dog should be used for dove hunting?

The answers to the previous questions need to be qualified as to what you want from a hunting dog. If your dog is a pointer, and you enjoy using him for his pointing ability only, then dove hunting is not for him. Doves do not lend themselves to good bird dog ging, as they are not a pointing species. However, if your dog is accustomed to sitting silently in a blind and is used for retrieving ducks, you will find him an asset and highly enjoyable on doves.

Familiarity and patience, along with the frequency of the action, will generally convince your dog that he too can hunt doves, and his ability to find cripples will be greatly appreciated.

Regardless of what method Nebraska hunters choose to use when pur suing doves, hunting on private land will require permission. An exciting, challenging experience can be enjoyed again in 1975, but a completely clear conscience will require the O.K. of the farmer host.

Hunters planning to hunt mourning doves should investigate the potential of state and federally owned lands. Some of the public hunting areas will offer thousands of acres of excellent dove shooting, and the areas are well distributed throughout the state.

Panhandle hunters should consider the vast acreages available in the Pine Ridge. Federal and state lands will be open to dove hunting, and excellent hunting opportunities should be available.

Hunters residing in the Sand Hills will have their choice of many large tracts, including Pressy, Rat and Beaver lakes and the national forest.

Southwest Nebraska residents may look forward to hunting on the lands surrounding the large reservoirs, the Sacramento Game Management Area, or on any of the wetlands maintained for waterfowl production in the rain water basin country.

Those in the northeast or southeast have less acreage per capita of public lands than the western hunters, but an ample number of prime sites will be available for those wishing to investigate.

Hunters statewide shouid obtain a copy of the brochure, "Where to Hunt in Nebraska". All public hunt ing areas are listed, giving directions from nearest town, size in acres, and species likely found. Doves will not be listed, but can be considered present at nearly all areas. Due to the short time span, some public lands could not be opened for dove season, in cluding the Valentine and Crescent Lake refuges. Also, state recreation areas will not be open unless specifically posted.

FISHING... BIG GAME AT BIG MAC

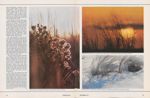

FISHING AT LAKE McConaughy always looks good. But every year, the big lake seems to save the best of its fishing for the tail end of the season.

Come fall, when most folks are stowing their fishing tackle and parking the family tub in drydock, Big Mac's fish are cruising the lake, ready to pick a fight with any angler they come across. By that time, Nebraska's summer vacationers are back in school or on the job, and many serious outdoorsmen are polishing shootin' irons and sharpening their eye for hunting seasons.

But the savvy fisherman will stick with Lake McConaughy through the last days of September's shirtsleeve weather right on into the chilliest days of October and November. And his reward will most likely be stringers of big and heavy walleye, some showoff rain bow trout, and a chance to tangle with the boss fish of Big Mac, the brawny striped bass. In fact, this fall fishing is the favorite sport of those who know the lake well; men like fishing guides Monte Samuelson and Al Van Borkum.

In recent years, the striper has been the big star of McConaughy's fall fishing, and, he probably deserves the top billing. He is everything a sportsman could ask for in a game fish: a short-fused charge of silver dynamite that can tax the stamina of the best tackle and hard iest angler.

But the most intriguing thing about him is the future. All kinds of excitement have been generated by mere 15-pounders, yet fisheries biologists say the striped bass has the potential of easily topping 20 pounds, very possibly reaching 30 pounds or more in Nebraska.

Quite a few fishermen have learned how to score on Big Mac's big stripers, but darn few have spent more time with them and learned more about them than "Monte" Samuelson of Lemoyne. He and his father, Gus Samuelson, operate a tackle shop and cabins at Lemoyne, and Monte spends a good share of his time guiding fishermen on the lake.

Last year, Monte personally connected on eight Master Angler Award stripers, and their resort verified applications for more than one-third of the 282 Master Angler striped bass Big Mac produced that year.

Monte generally locates stripers in flooded timber from 25 to 45 feet deep when the fish are feeding, or in timber as deep as 70 feet when they are at rest. His most productive areas lie along the north shore of the lake, two miles, five miles, and seven and one-half miles above the dam respectively.

"Stripers like the flooded trees in deep water. We've got several spots offering these conditions on the north side, but the habitat on the south shore offers mostly rocky cover. That's why most of the striped bass are caught along the north side," Samuelson said.

Photo by Bob GrierHis favorite method, by far, is jigging with a big white slab. The jigging technique and the heavy lure allow him to reach the deep hangouts of the stripers without resorting to lead-core line, heavy sinkers, troll ing planes, oversize fishing rods and reels, and any other paraphernalia that dampen a fish's fighting ability and reduce the angler's "feel". Jigging with the slab, or perhaps a 1 -ounce jig, provides the fun of fighting a furious striper with medium-weight spinning rod and standard monofilament line.

Samuelson makes good use of an electronic depth finder to pinpoint potential striper areas. Generally, the cover patches he works were once tree groves associated with ranches now covered by the reservoir. He drops his slab right alongside these lines and clumps of trees, fishing on the bottom as close to cover as possible.

In his jigging game, Samuelson prefers the white slab, although yellow sometimes works in the mornings and evenings. Usingagood spinning rod and reel loaded with 12 or 14-pount-test line, he raises the lure gently, then lets it flutter back down.

Sometimes, jigging just doesn't work, usually because the stripers are scattered. Then, Samuelson grabs his trolling rig, an 8I/2 or 9-foot rod loaded with lead core line, a 15-pound test monofilament leader, and equipped with a shad-like lure. Hottest lure last year was a large Bayou Boogie, although the Thin-fin and a large Rebel also produced fish.

The lures that Monte and other striper fishermen select attests to the fish's fighting ability. "I ordered larger lures because they have stronger hooks. I've even special-ordered some with stainless steel ocean hooks. Big stripers will simply tear the hooks off ordinary lures."

Besides strong construction, the right appearance is another requisite for a top-notch striper lure. Shad are the staple in a white bass' diet, and a lure should be colored like one if a fisherman expects a striper to try it out for lunch. That's why most of Monte's striped bass plugs are grey, grey with a white belly, or metallic silver in color.

When he has to resort to trolling, Samuelson sometimes drags these magnum lures right over the top branches in 35 to 40 feet of water, but he really prefers to work nearer the bottom, alongside the trees. He has found that stripers like the lures fairly close to the floor of the lake. "They'll rise to a lure if you don't have it right on the bottom, but usually not more than about four or five feet," he said.

12 NEBRASKAland SEPTEMBER 1975 13

Jigging and trolling near the trees account for a vast majority of the stripers taken, but Monte advises that some other methods also work on occasion. Sometimes a minnow or nightcrawler dropped into the striper's lair will get results, although artificials usually outproduce bait by a wide margin.

Sometimes, fishermen manage to nab stripers by trolling at night. And, on very rare occasions, they can be located near the surface much like white bass, when gulls mark the schools of shad that feeding game fish drive to the surface.

Samuelson offers one final bit of advice to would-be striper fishermen: "The striped bass is the king of the hill in this lake, and when there are stripers around, other fish just move out. So, if you catch a walleye or white bass in one spot and you want nothing but stripers, move on. Other fish in an area generally tell you there's no striped bass nearby."

However, if you wouldn't mind catching a walleye or two in the fall, Lake McConaughy's still the place to be, and Samuelson can give some good advice for taking them in the lower part of the lake.

Generally, the north shore features bars and other sand structure, while the south shore offers rocky points and ledges. Monte advises fishermen to work all of these areas from 20 to 50 feet deep. Trolling is done with lead core line, monofilament leaders, and bayou boogies or Thin-fins.

Jigging with slabs also produces, especially along the rocky shelves and ledges. Good-size walleye lurk at the lower part of these dropoffs, and will often latch onto a slab dragged into their lair from above. Generally they strike with all the enthusiasm of a medium-size boulder, and unsuspecting anglers often find the "snag" of a moment before trying to swim away.

FISHING... BIG GAME AT BIG MACFarther up the lake, the fall walleye is altogether a different critter than the one nearer the dam, according to Al VanBorkum, operator of Lake View Fishing Camp. And his opinion shows in some of the fishing tactics he uses.

He feels that water temperature plays a big part in the walleye's life at that time of year, and the number of fishermen on the lake has something to do with fishing success.

"Whether we have good fall walleye fishing or not is kind of a hit-or-miss affair. If the water temperature drops to a walleye's preferred range early while there are still some fishermen around, we will be able to locate them. But, if the cooler temperatures wake the fish up after most everyone's gone, it's hard for the few of us left out here to find the fish."

According to VanBorkum, the walleye's preferred temperature in the fall is about 60 degrees, or within five degrees either side of that mark. Consequently, a thermometer and a depth finder play a big part in his fishing plans.

Most of the time, he will use the thermometer to find how deep the 60-degree layer lies, then refer to the depth finder to locate bottom structure at that level. He uses a controlled drift in such areas until a fish is caught, then anchors and works it by casting or jigging.

His favorite walleye getter at that time of the year is a tandem rig, usually a white slab at the very end of the line, with a yellow or white, Va-ounce jig tied 12 to 18 inches above. Sometimes, a Kastmaster works well in place of the slab.

Snap-swivels should not be used to attach the slab or Kastmaster, since the lures tend to get hung up on the line when the extra bit of hardware is used. They should be tied directly to the line, and the knot should be re tied often, since the jigging on the bottom and tugging of the fish is hard on knots and line.

The thermometer and depth finder tactic works well for VanBorkum, but his favorite fall walleye tactic reads more like a page from a white bass fisherman's book. "I check out every flock of gulls that I can find feeding on the surface of the lake. White bass are not

ICE FISHERMEN! If winter bait is expensive or hard to come by in your area, ask a local beekeeper for some waxworms, and our October "Fishing" will show you how to raise enough to last all season. Don't wait too long to approach the beekeepers since they wrap up opera tions from late August to mid September. It's a somewhat involved process, and only serious hard-water anglers will want to bother. In the meantime, get a pound of cheap brewer's yeast, a few ounces of bees wax, and you'll be ready when the directions appear next month. Keep the waxworms refrigerated until then.

the only fish that feed on shad and drive them up to the gulls. Walleye do this frequently, and I've even caught limits of catfish where gulls are working."

"I've found that the walleye is not always the bot tom-hugging fish that everyone says he is. When conditions are right, he will leave the deep water and chase baitfish to the surface. For example, the state record walleye of 16 pounds, 2 ounces, was taken near here on a surface lure in the middle of summer." (see Fishing Fanatic, July 1973 NEBRASKAland)

When he's not chasing walleye around the lake in the fall, VanBorkum looks for the third of Big Mac's big fall combo, the rainbow trout. He rates the midsection of the lake as the best rainbow territory at that time of year. The trout apparently gather in the middle of the lake over 60 to 70 feet of water to feed in preparation for spawning runs up the North Platte River in November and December.

His method involves trolling, but he runs his boat several times faster than most walleye and white bass fishermen would consider prudent. "You have to move your lure right along, probably from 700 to 1,200 rpm on most fishing motors. You have to be careful when you select your lure, too, because a lot of them do not perform well at that speed. Speed Shad and Thin-fins work well, and Kastmasters or conventional spoons sometimes produce. But others, like the flatfish, will twist your line and be nothing but trouble at that speed."

This fast trolling technique, combined with medium-weight spinning gear and 10 or 12-pound-test monofilament line, keeps the lure near the surface. Thus, the rainbows can best show their fighting form right on top against sporting tackle.

Another way to get fall rainbows also involves fast trolling, and about the same lures are used. The only difference is about four to six "colors" (40 to 60 yards) of lead-core line. At that speed, the lead-core line takes the lure down only about 15 feet.

In using either method, VanBorkum sets the drag on his reel so light that it just barely holds against the resistance of the trolled lure. "I figure the drag's about right if I can make it give line by pulling forward on the rod while trolling. That's what I'll want the drag to do when a rainbow hits, because they smack the lure with incredible gusto. Any more resistance than a very loose drag would pop the line or tear the hooks out of their mouths immediately."

According to VanBorkum, somewhere around September 10 to October 10 is usually tops for rainbows. And the entire fall period is one of the best times of all for anglers on Big Mac. "We have this big lake all to our selves then," he says. "No sandeaters or sunburners — just a few fishermen and lots offish."

Poling For Frogs

WHEN SMOKEY AND BO drive that old pickup back into town after a day of froggin', you can bet that a small crowd of speculators is about to accidentally happen by to gaze in amazement at the pile of frogs certain to be dumped from their white cotton game bags.

All experts have a reputation to up hold, whether it be marksmanship, art, or just plain froggin', and I guess you might say that Smoke and Bo have done a pretty fair job of protecting theirs, as they have been dubbed the foremost frog experts of Nemaha County.

George (Smokey) Schmucker and Alfie Floyd (Bo) Bowen grew up around the town of Brock, which was originally and officially named Podunk, Nebraska. To coin a phrase familiar to Jack Webb fans, the name was changed to protect the innocent. Brock is a solid farming community with a large percentage of its revenue generated directly or indirectly on what the land can produce. Even with this strong demand placed on crops and cattle, it is evident that wildlife has won a warm place in the hearts of the people of that community.

Good habitat is apparent almost everywhere, as most fencerows have been left decorated with wild plum thickets, and wood lots continue to grow with oak, walnut, elm and spruce. Squirrels find cover and food in the hickory brush, and the bobwhite's whistle complements an early spring morning for those who accustom themselves to arising before the sun.

When World War II came to Europe, it also came to Brock. George Schmucker enlisted in the Army Air Corps and piloted a large bomber. Floyd Bowen enlisted in the Army and drove a tank. From then until the end of the war, they saw each other only once; and it was probably for the good of both men that another wartime reunion did not present itself. Smokey took Bo for a ride in "his" plane and Bo took Smokey for a ride in "his" tank. Who scared who the most is still being argued.

Bo's tank-driving experience is evident in the way he maneuvers his old station wagon over the rugged roads of the Nemaha Valley surrounding Brock, and Smokey must have learned a few tricks about terrestrial navigation, as his old '51 pickup won't be outdone by any wagon.

"Hard telling what kind of mood the frogs will be in today," lamented Bo as he cast a disgusted glance at the cold September rain that had settled in on the valley. "Don't know if we're gonna see any frogs or not. Sure wish it would quit drizzling and let that sun out, maybe it would warm up a bit."

"We'll have sun by 10," predicted Smokey as he assessed the conditions, noting that is was already starting to clear in the west.

Though George and Floyd cussed and discussed the weather most of the morning, continuous progress was being made in preparation for frog hunting, and finally the inevitable suggestion was made to give the frogs a try regardless of atmospheric conditions.

The first pond was just a few minutes from town, and completely concealed from the view of passing motorists. This is basically true of all the ponds George and Floyd frog.

"Ponds you can't see get less pressure," George theorized, "and most people don't know that some of our best froggin' ponds even exist."

Every time someone makes the mistake of asking where they get such big frogs, he gets the standard reply: "In the pond." This is a pretty vague answer considering there are more farm ponds in Nemaha County than there are farms. Still, somebody will always ask, and they always get the same answer. It doesn't anger George or Floyd when people try to uncover the secrets of their specialty. In fact, they'd probably be disappointed if people didn't ask.

As the two men approached the dam from below, an air of cunning slyness gradually gained control of their every move. Peeking cautiously over the top of the dam, their eyes strained in an attempt to differentiate frogs from various clods lumped at random around the perimeter.

"There's some real beauties out there," whispered George. And if some of those lumps weren't clods, George was right...there were some real beauties out there. They slowly stood up to gain a better view of the pond, and it sounded like one big splash as every frog around the lake simultaneously hit the water. There went the clod theory.

"Would you just look how spooky they are? Never seen them quite so bad as that," remarked Bo, whose eyes were still wide from the diving exhibition he had just witnessed.

"This drizzly weather's got some thing to do with it. You can bet even money on that," rationalized Smokey. "They'll be back up. That's one thing about an old bull. He'll pick himself a spot along the bank and wash himself out a shallow hole, and there he'll sit in the sun waiting to stick that long tongue out and latch onto just about anything smaller than hemself."

Then George rendered a lengthy dissertation on frog know-how. "It's a proven fact that bullfrogs eat snakes, fish, crawdads, mice and sometimes birds. If he gets scared and takes to the water, he'll be back soon, and return to the exact same spot— in a mat ter of minutes. First you'll see those two big eyes poke up out there in the middle somewhere, then he'll stick his head out and look back toward the bank to see if the coast is clear. Then he'll disappear again only to repeat his previous maneuver, but this time he'll be only a few feet off shore. The next time you see him, he'll be crawlin' out on the bank. Sometimes you can be there waitin' for him."

With that confidence in their know ledge of typical, every-day, bullfrog habits, Bo went one direction and Smokey headed the other. Toward the north corner of the pond was a sheltered area with trees in the water. A large bull was propped up under the trunk of a diamond willow. George must have spotted him a hundred yards away, and likewise the frog did George. With a vault that would have won the Calivarus County frog jump ing contest, the mammoth bull disappeared (Continued on page 46)

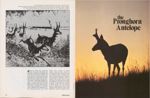

the Pronghorn Antelope

Before the white man moved out onto the prairie and plains, the pronghorn antelope was probably the most abundant hooved animal next to the bison. An early traveler on the Nebraska plains noted that "the antelope, with the simple curiosity peculiar to them, would often approach us closely/' In a few short years the antelope's curiosity had nearly led to its extinction in the state. By the 1880s, most of the pronghorns in Nebraska were confined to the northwest corner. During the early years of the 1900s, their numbers in North America were less than 20,000. In 1925 fewer than 200 antelope roamed the Nebraska plains. Complete protection and ^introduction programs have helped the antelope to grow in numbers and reclaim some of their old range. In recent years the number of pronghorns in Nebraska hasclimbed to nearly 10,000 with over 400,000 in North America. On the following pages is presented the story of that uniquely North American animal, the pronghorn; and their struggle to exist.

18 NEBRASKAland

FOSSILIZED REMAINS on the North American continent are reminders that the pronghorn antelope (Antilocapra americana) roamed the land in present-day forms as early as the Age of Mammals, over one million years ago. Evolutionary changes may have taken 20 million years to develop the pronghorn as we know it today.

Surviving the rigors of this violent young continent, the ancestral pronghorn antelope thrived and evolved into an alert, fleet-footed ungulate which roamed the large expanse of brush, grassland and cactus of the plains area.

Into this scene man made his appearance some 20,000 years ago. The pronghorn surmounted obstacles of glacial and drought changes of the young developing continent, but was nearly exterminated by modern man and his machines.

In the early 1800s, vast herds of bison and antelope were recorded by the Lewis and Clark expedition and others. Estimates were made of about 35 million antelope in North America. Within 100 years, antelope declined to a low of 20,000 animals and it was predicted that they were doomed to vanish from this continent. But, con servation-minded leaders in our coun try saved the pronghorn from extinc tion by their quick action.

The pronghorn antelope is the only living member of its family, Antilo capridae. Generally, four subspecies are recognized: 1) A. a. americana found throughout the great plains from Canada to Texas; 2) A. a. oregona found in Oregon, Idaho, Nevada and California; 3) A. a. peninsulara of lower California; and 4) A. a. mexi cana found in Mexico.

The historical antelope range covered most of the Great Plains, as well as the high sagebrush plateaus and grassland valleys in the western states, parts of south-central Canada, and northern Mexico. By the mid-1920s this original range was reduced considerably due to habitat changes caused by agricultural development and man's inroads into the antelope domain. Only the more arid, unsuit able lands for agriculture in the great west remained for the antelope, and today these are its strongholds.

From less than 20,000 antelope in the United States in the early 1900s, numbers increased to over 26,000 in the 1920s, 130,000 in the 1930s, 360,000 in the 1950s, and over 400,000 in the early 1970's. In fact, the North American continent had an estimated population of 435,200.

Reintroduction of antelope has extended the range back into some unoccupied regions of their historical range. In addition, transplants have been made in three states that never had antelope during historical times (Florida, Washington and Hawaii).

As civilization advanced westward, the native prairie gave way to agriculture, and at the same time an antelope decline occurred. Several factors or combination of factors were re sponsible for the decline. Some believe the extirpation of free-ranging buffalo had a great influence on antelope numbers since they were found in direct relationship to each other. Certainly the changes in habitat and land use, and the lack of harvest restrictions, had great influence on antelope numbers. Whatever the cause for the decline, by 1900 only remnant herds remained in pockets of the western ranges.

To prevent a total loss of the species from the Nebraska scene, the 1873 Nebraska legislature passed a law making it unlawful to kill, ensnare or trap any deer, antelope or elk between January 1 and September 1. It was furthered restricted, from January 1 to November 1, in 1897. Finally, in 1907, the season was totally closed for the taking of elk, deer, antelope and beaver. The season on antelope remained closed until 1953, a period of 46 years.

A 1925 publication stated that 10 small bands^totalling 187 animals remained from the thousands of antelope which once roamed the Nebraska plains.

Recovery of the species in Nebraska was slow. However, by 1955 the estimated population in western Nebraska was approximately 3,500. Hunting seasons have been held every year since 1953 with the exception of 1958.

The major antelope range is broken by three escarpments and several rivers and creeks in an east-west direction. The Pierre Hills, commonly referred to as the badlands in Nebraska, extend south from the South Dakota state line in the northwest part of the state. The Pierre Hills then rise abruptly to meet the Pine Ridge escarpment which slopes gently south ward to the Box Butte tableland and on to the North Platte Valley. South of the river, the Wildcat Hills escarpment drops into the Pumpkin Creek Valley and confronts the Cheyenne escarpment and its tableland.

The climate is mild, but as is typical of the High Plains region, much fluctuation of temperature occurs. Occasionally, severe winter storms sweep through the state. Normal annual precipitation in the antelope range varies from 15 inches in the west to 23 inches in the east, with most of it occurring from April to June.

The shortgrass rangeland of the Pierre Hills and Box Butte table support the highest density of antelope numbers in the state (3.7 and 1.6 antelope per square mile respectively). Aerial surveys conducted during the summer of 1974 show an average of 1.1 antelope per square mile in the primary range of the Panhandle.

The better antelope range in Nebraska is found in the northwestern portion of the state. It is characterized by rolling plains developed on soft, clayey shales. The low hills are round topped and the valleys are broad swales. Pockets of small, badly eroded areas of badlands are found in the area. Vegetative cover is thin with sparse stands of grasses, principally western wheatgrass, needle-and-thread, blue grama, hairy grama and buffalo grass. Prickly pear cactus is quite abundant. Willow, cottonwood, ash and elm grow along the watercourses. Pockets of sagebrush do occur in the grass land. A variety of forbs is found scat tered throughout the range.

A Year with A the Antelope

Photo by Bob GrierLATE SPRING is fawning time for the Nebraska pronghorn. As in most gregarious species, the pronghorn doe stays apart from the group as the time of birth approaches. Per haps this desire for solitude is due to an inherent fear of the newborn becoming mixed up within the herd and trampled, or even being attacked by adults of the herd. It may also be from fear of the herd scent being imparted upon the newborn, which would serve to attract predators.

Kidding grounds are usually located in swales and low-lying areas with small ridges or hills surrounding them. Vegetation is usually short and sparse. It must provide cover for the young but still allow the protective doe to keep a watchful eye on her offspring.

When delivery time approaches, in late May or June, the fetal sack drops and distends the abdomen of the doe. By this time the mammary glands are well developed and the doe is seen standing listlessly. As contractions of the abdomen begin, the doe alter nately lies down and gets up, perhaps to get the fetus in proper position. With the fluid-filled sack protruding, the doe becomes even more restless and occasionally spins around in a circle as if to find a place to lie down. Her stance at times is very still except for her flipping tail. Soon the head of the young antelope can be seen. Much lying down and getting up will continue while more of the young is exposed, until the young is slid to the ground. Following the delivery, the doe starts tearing and removing the fetal membrane and licks the young dry to stimulate blood circulation. Normally a second twin is born about 30 minutes later. The entire twin-birth process takes a little over an hour. Nursing of the young begins as soon as it can stand on its wobbling legs; even while his twin is being born. The weight at birth ranges from 5 pounds to over 9 pounds and averages 6% pounds. Males average about Impound heavier than females.

Training of the kids starts early in life. When only a few hours old, the young are taught to remain motion less in the face of danger. The doe usually joins other females in a small group while keeping a watchful eye over her hidden kids. When danger threatens, the doe will try to lure the predator away by being the decoy. Occasionally, in her attempt to lure the intruder away from her hidden young, she may inadvertently stumble across some other kids and endanger them. The kids, unless they are several days old, will remain motion less in the scant vegetation and are completely safe from the nose of a predator as they are scentless while newborn and vulnerable.

Sprinting for short distances, older antelope kids can outrun most pred ators, but usually the doe will lead the way and hide her kids one at a time as they disappear over a slight rise or drop into a depression. If the youngster refuses to hide, the running doe may nudge or even knock the running ki down into hiding while she continues to lead the predator away. When the presence of the predator is no longer imminent, the doe will round up the young, nurse them, and then cache them some distance apart. The doe then resumes her normal routine and may move as far as half a mile away.

As the young grow older, they accompany the doe. Later, they will be joined by other young kids and be left in a group with nursemaid does. In truders are quite often met by a band of does and are threatened with bodily harm, but these actions are usually bluffs on the part of the pronghorns.

The young antelope develops rapidly and soon starts to experiment with various succulent vegetation. His periods of nursing at a couple of weeks of age are restricted to four or five times a day, at intervals of several hours instead of every half hour. At six weeks of age, the young antelope has all of its deciduous incisors and pre-molars with one permanent molar, so he is then ready for a diet of vegetation.

The major portion of their diet is composed of forbs and browse plants, with very little grass being consumed. Studies show that forbs and browse constitute 85 percent of the antelope's annual diet, while cacti make up 11 percent, and grasses and grass-1 ike plants, including wheat, make up 4 percent.

Seasonal variations occur in the diet, which may be due to several factors, including availability, pay ability, succulence, and preference. As the seasons progress, various vegetation becomes available, and pay ability increases or decreases at different growth stages. Certain plants are more palatable or nutritious at different growth periods and thus are preferred. Studies have indicated that pronghorn and other animals are able to select plants with higher nutritional value.

During the fall, browse was shown to make up the major portion of the pronghorn's diet in the shortgrass prairie range of northeast Colorado. As high as 75 percent of the diet is browse plants in the fall, while in winter the percentage drops to 50, and in the spring and summer, about 25 percent.

A limited food habit study made in the fall showed some differences in the diet of the Nebraska pronghorn from those of northeast Colorado. It was found that browse-plant species were not very important in the fall, while forb plant species received greater use. This probably is a reflection of the plants found on the Ne braska antelope range. The study showed that forbs made up 81 percent of the plants used as food, cactus 19 percent, browse less than 1 percent, and only traces of grass.

Forbs play an important part during the spring and summer, while they are of lesser importance during fall and winter. However, they assume an equally important part of the prong horn's diet on a year-around basis.

Cacti use in summer and winter in creases to 15 percent, and drops to 5 percent during spring and fall. Apparently, cactus is used as filler or emergency food when others are less palatable or not available. Grass consumption is low on an annual basis; however, during spring "greening up", use of cheatgrass brome in creases to about 20 percent.

Two members of the grassland community, the bison and the antelope, lived in relatively close relationship to one another. The buffalo lived on the great expanse of the grassland plains and moved long distances following the growth of different vegetation through the seasons. In the wake of huge herds of bison, the antelope no doubt benefited by the grazing and trampling activities, which caused much damage to the grassland. The

Photo by Jon Cates

Photo by Jon Cates

sparse vegetation on the grassland, especially the shortgrass range, supported a variety of vegetation such as forbs, browse, grasses and cacti. The forbs, generally annuals, were the first to recover from the onslaught of thousands of feeding bisons.

This relationship and association of bison and antelope is replaced today in the form of antelope and range cattle. This relationship also occurs in other grasslands of the world. Under natural or wild conditions on good range, the antelope and bovines affect each other less than any other combination of animals. On poor range, cattle are forced to utilize browse and forbs, and a competition for food may develop with the pronghorn.

Studies have indicated that antelope livestock competition is nearly negligible, and in some cases is beneficial to the range in general. Because their food habits do not overlap significantly, it would take about 105 pronghorns to utilize as much cattle forage as 1 cow. Pronghorns consume many poisonous and injurious plants, including larkspur, loco weeds, rubber weed, rayless goldenrod, cockleburs, needle-and-thread grass, and yucca. Other undesirable range plants consumed by antelope are snakeweed, rabbitbrush, fringed sage, Russian thistle, and saltbush. Wise range man agers encourage pronghorns to use their rangeland to discourage the in crease of undesirable species of plants.

The growth of the young pronghorns increases rapidly as summer progresses. However, it will be almost three months before they develop the speed and endurance of the adult. Occasionally a weak individual, which has succumbed to disease or parasites, will be overcome by mammalian predators. Avian predation is believed to be rare, but carrion feeding by eagles and hawks is believed to be quite common.

The coyote is the major natural mammalian predator of the pronghorn, even though his top speed is far less than that of the pronghorn. Antelope cruise at speeds of over 30 miles per hour and have been clocked at 50 to 60 miles per hour for short distances. The coyote's cunning and the pronghorn's habit of running in a wide circle can cause the antelope to fall prey. Several coyotes may utilize a system of relays to tire the chosen victim, which frequently ends as a meal for the canines. Coyote predation is, however, normally on weak or sick individuals, or on other less

Photo by Jon Catesspeedy and more abundant prey species. When the buffer species that coyotes usually prey upon is in short supply, the coyote may be an important antelope predator, especially on the young. Natural mortality due to predation alone is not normally considered an important factor in prong horn management.

During late summer and early fall, the more stalwart bucks begin to challenge imaginary rivals as if shadow boxing and sparring. The male will strike an odd pose of head hanging, as if in his last stage of physical decline. Suddenly his rump patch will appear to blossom and each strand of hair on his body will appear to stand up and vibrate. Then, with no apparent reason except, it seems, to release some excess energy, the buck will run and bound stiff-leggedly over the grassland. It doesn't matter to the buck whether he has an audience or not. When other bucks are encountered, two or more may back off and participate in mock battles. Seldom does any individual get injured in this display of vigor and power.

Photo by Greg BeaumontAs the height of courtship and mating approaches during the last half of October, the females in the harem become more and more attentive to the buck. Deer, antelope, and other wild life are stimulated by the excitant of a powerful secretion of musk from special glands. As the buck responds to its influence, the doe is fondled by the neck and head with gentle gestures. Using coquetry, the doe pretends to run away in alarm. Stopping and look ing back at the buck, the doe returns to just beyond his reach. As excite ment mounts, the buck stirs it to higher pitch by giving chase. The two animals gallop off at full speed each time until at the last run, the doe stands and the courtship terminates with the consumation of mating. This behavior is so much a part of the species that lonely old bucks will even make this courtship run alone when unable to

find a doe to precede the chase.

find a doe to precede the chase.

The gestation period is believed to be from 230 to 240 days, with a peak of kidding in Nebraska occurring about June 12. A study on a confined herd of antelope near Sidney, indicated a peak of kidding between June 10 and 15. Thus, if the data obtained from our study is indicative of Nebraska's wild antelope population, conception occurs between October 10 and October 20.

Unlike other wildlife, that relies upon cunning and body coloration, the pronghorn depends on keen eye sight to detect danger, and great speed to outdistance it. The old adage of "safety in numbers" applies to numerous species of wildlife, but most of all to pronghorns. They are nearly al ways found in groups of five or more. The pronghorn buck, however, may be found by himself.

When grazing, a sentinel is stationed on a knoll to watch for intruders on their vast domain of short grass and open space. With the first hint of danger, the group is alerted and swift flight carries the animals to distant safety.

Photo by Jack CurranThe white hairs on the pronghorn's rump can be erected to flash a heliographic warning. Thus, the sentinel can alert others to the potential danger of an approaching predator.

The general body structure indicates great speed. The legs are slender and long and very lightly muscled toward the hooves, while heavily muscled close to the body. Large windpipe and lungs allow huge quantities of air to be gulped in by mouth as well as through the dilated nostrils.

Antelope have true horns that are composed of fused hairs formed over a bony core. There is a forward projection, or prong, from whence the animal derives its common name, the pronghorn antelope. These horn sheaths are shed annually, during the winter. Bucks have well developed horns that may attain trophy lengths (up to 20 inches), while older females have nearly inconspicuous horns of single-point fused hairs, seldom exceeding the length of their ears. Other differences between the sexes include a very dark face and dark triangular-shaped cheek patches on the males. The overall coloration of the antelope is tawny brown on the neck, back and legs, while patches of cream to white occur on the lower side of the neck and body. Viewed from the back, the white rump patch is very prominent.

The antelope is very well adapted to the rigors of the grasslands, where summer temperatures may soar above 100 degrees Fahrenheit and during the winter may drop below minus 20 degrees. The pelt of the pronghorn is composed of individual hairs which are hollow and filled with air. The hair is loosely attached to the skin, which is underlaid with a network of muscles that can raise or lower the hair at will. When the hairs are laid down they form an efficient insulator, keeping the cold temperature of the surrounding environment out while retaining the body heat of the animal. During hot summer days, the hairs can be held erect, allowing a move ment of air to cool the skin. Due to the brittleness and the loose attach ment of the hair to the skin, antelop pelts are not valuable as fur. The tanned skin of antelope is also not valued due to the poor wearing quality of the leather.

Photo by Jon Cates

Managing the Herds

WILDLIFE IS A RENEWABLE natural resource, and if managed wisely, can be cropped annually without depleting the stock. Manage ment of a wildlife species is done by obtaining information about its population and relationship with its habitat. The controlling factors that limit population numbers must be learned before effective management plans can be initiated. In Nebraska, big game management policies must take into consideration the interests of the sportsmen and the landowners upon whose land most of the animals live. The goal of providing the greatest number of antelope and recreational benefits to the sportsmen, while keeping antelope populations at levels consistent with the agricultural interest of the land, becomes a challenging one for the game manager. Herd and harvest inventories play major roles in antelope manage ment of Nebraska.

Information relative to population number, distribution, sex, age and range conditions is collected throughout the year, but the sum mer aerial inventory provides most of this information.

The annual aerial survey is conducted by a low-flying aircraft with observers counting the animals by sex and age on a regular flight path. The time the animals were observed is also recorded. This information can then be plotted on a map and the relative distribution within the management unit can be deter mined. Distribution of antelope has changed over a period of years, and this is important in managing herds on a unit basis.

During the 1974 survey, an estimated 8,217 antelope for the study area in the Panhandle indicated the highest population during a 20-year period. However, the doe-kid ratio of 100 does to 50 kids indicated one of the lowest productivity rates for the same period. The 20-year average is 100 does to 65 kids, while the last 5 years averaged 100 does to 57 kids.

Once herd numbers have been estimated and the population status determined, the game manager must decide whether to increase, decrease or stabilize the herd by controlling the harvest.

If the herds are below the carrying capacity of the range and the tolerance level of the landowners, the number of permits authorized may be low to limit the harvest and in crease antelope numbers in subsequent years. However, if herds are above carrying capacity or tolerance limits, then more permits must be authorized to reduce antelope numbers.

The first hunting season in recent history was held in 1953, after a closure of 46 years. It was a 5-day hunt limited to a small portion of Cheyenne County. Since 1953, antelope seasons have been held annually except for 1958 when the season was closed.

The popularity of antelope hunting is shown by the great number of applications exceeding the authorized number of permits each year. Permit allocations have been on an unbiased, lottery system, but some times purely by chance the same persons were unable to receive permits year after year. Thus, a more equitable system for allocating permits was necessary and in 1973 a restriction was placed upon holders of per mits the previous year. In 1974, restrictions were placed on holders of permits in the previous two years. Even with these restrictions, demand for permits was over two times the authorized number in 1974.

Generally, 83 percent of the total harvest for the season is taken during the first 2 days, regardless of the length of the season, and 93 percent of the hunters require 2 days or less to bag an antelope. Therefore the additional days after the third day are for the benefit of trophy hunters and for hunter convenience. Since 1953, a total of 19,182 antelope have been harvested by 23,719 rifle hunters. Hunter success over the years has varied from 74 to 88 percent, averaging 81 percent.

That rifle hunters show preference for adult bucks is clearly indicated by the harvest data. Summer inventory data show the population structure of 20 percent adult males, 53 percent adult females and 27 per cent young of the year, while 1974 harvest data show 64 percent were adult males, 27 percent adult females, and 9 percent kids.

Information collected at check stations has greatly aided the man agement of the species. Data obtained include sex, age, and general physical condition of the animals (weights and measurements), hunt er distribution, pronghorn distribution and other information concern ing the hunt.

Weight measurements are used to compare with similar data obtained in other years for determining range condition trends and physical condition of antelope. Males are about three percent heavier than females as kids, and by the time males are yearling and older, they are from 8 to 18 percent heavier than the females.

Effective management recommendations can be made by utilizing the population structure by sex and age classes. Several methods can be used to obtain this information, but the sex and age class information obtained during the harvest seem to be the most accurate and unbiased. The game manager utilizes the man dibular eruption and wear method of aging antelope which are brought to check stations. This biological in formation, when used to construct an age structure graph, can reveal a

The archery season, with 64 days, has insignificant influence on the herd while providing considerable recreation. During the last 5 years, 592 archers harvested 65 antelope for an average hunter success of 11 percent. Since 1964, 913 bow hunters took 122 antelope for an overall success of 13.4 percent.

Pre-natal mortalities occur in antelope as in any other species and are probably a matter of poor nutrition and environmental stress. After parturition and before hunter harvest, there are numerous causes of mortality. Accidental losses occur from collisions with automobiles and trains, or when the animal becomes entangled with barbed-wire or woven-wire fences. Severe weather conditions can have drastic effects upon antelope. Large herds have perished during storms, especially when their physical condition was poor prior to being subjected to stress.

Losses occur throughout the life span of the pronghorn, but are probably more prevalent prior to adulthood. Pronghorn kids have been abandoned by their mothers after excessive handling by humans. This may be the result of human scent being imparted to the kid at a time when the animal is scentless.

Predation as a rule is not a threat to any healthy wildlife population, however, under certain circum stances may be devastating. One such period for the pronghorn may be when the herd number is low due to other factors, and losses in combination to this may reduce or even annihilate the herd. This is referred to as the "threshhold point", and the natural increment to the herd by way of reproduction cannot offset the losses.

The most damaging predator with the greatest potential for harm to pronghorn numbers is man. With his modern machines, man can be the super predator with which the pronghorn cannot cope. However, habitat changes brought about by man are currently a much greater threat to antelope than is his predatory nature.

Man, though, has done much to enhance the proliferation of the pronghorn over much of its original range. Historical records show that antelope once roamed throughout most of the Great Plains, of which much of Nebraska is included. A 1925 publication cited that 10 bands, totaling 187 antelope, remained in Nebraska. The Panhandle herd increased to about 3,500 in 1955. However, antelope remained at a low level in the Sand Hills and were primarily restricted to the western edge of the area bordering the major antelope range. Trapping and transplanting has proven to be an efficient method of re-establishing big-game animals on historic ranges, and it was felt that such a program v\*ould be beneficial to Nebraska's antelope management program.

The Sand Hills of Nebraska is about 20,000 square miles in the north-central part of the state. Rain fall ranges from 18 to 23 inches, with topography of sharply rolling hills and irregular ridges, relieved occasionally by level valleys. Shallow lakes and ponds of varying size are distributed throughout much of the region. The soil type of most of this region is described as dune sand. Vegetative cover is characterized by mixed grass associations and a variety of forbs. Trees are limited al most entirely to stream courses. Land use is almost entirely haying and grazing.

About 1.7 million acres were signed up under cooperative agree ments, and the trapping-transplant ing program was initiated in 1958 and terminated in 1962. It resulted in 1,077 antelope being released at 20 sites in the Sand Hills. Individual releases varied in number from 28 to 72 animals.

Within a very short period, the natural habits of the pronghorn to congregate in relatively large numbers, especially during the winter, resulted in depredation problems on alfalfa fields. As a result, it became necessary to hold limited hunting seasons in 1964 in the Sand Hills. A total of 3,238 Nebraskans have participated in the antelope harvest in the Sand Hill units as a direct result of the trapping-transplanting program. Hunter success averaged 72 percent for the period from 1964 to 1974 in the Sand Hills, while state wide success was 80 percent.

Tag recoveries from 75 antelope provided data on longevity and movements. The antelope were all aged and identified with individual ear tags. During the 1968 hunting season, a tagged doe was harvested which records showed as being over 10 years old. Movements of 75 antelope ranged from 0 to 125 miles from their release site, averaging 26 miles.

Hunting Antelope

THE PROPER TIME to harvest Nebraska's pronghorns is determined by a number of factors. Harvest should come at a time when the young of the year would be little affected by loss of the mothers. The young themselves should have developed physically to the point that the meat has flavor and texture. Since sport and trophy hunting are important, the harvest should occur prior to shedding of the horns, which normally occurs during November and December in Nebraska.

Techniques and strategies for hunting antelope vary with individual hunters and field conditions. Regardless of the technique employed, it is the hunter who planned his hunt and anticipated the opening day of the season that will be most satisfied in the end.

Pre-season preparations help the hunter bring home that "special buck." Practice, and lots of practice, under various field conditions, improves the hunter's chances of downing the animal of his choice. This involves sighting allowances for windage, distance and movement of the animal. One problem the hunter will encounter is the deceptiveness of distances due to flat terrain. Another problem is the unbelievable distance the pronghorn can cover between the time the trigger is squeezed and the strike of the bullet.

Trophy hunting is an art in itself which requires discipline, patience, experience, knowledge of the species, and as often as not just plain luck. Many successful hunters take to the field in advance of the season to study the lay of the land. Advance knowledge of the various avenues of approach and the animals' avenues of escape often spells the difference between success and failure. The stalk should be made quietly and carefully until a clean, one-shot kill can be made.

A trophy is defined in different ways by different individuals. It is generally accepted, though, that a trophy is not just a fine buck, but is an individual of wild elusivenss and cunning that taxed the hunter's skill and strategy. The trophy hunt is designed by the hunter in the manner he selects and finds most satisfying. This means meeting basic challenge of man versus wildlife on equal foot ing. This fact is best demonstrated by primitive weapon enthusiasts, such as bow and muzzle-loading hunters.

The hunt is essentially over when the pronghorn is down with a well placed shot. However, it is not complete if the trophy is to be mounted by a taxidermist. Prior to field dressing the animal, sponge away any blood that gets on the hair. Bleeding the carcass by slitting the throat ruins the cape for a full head and shoulder mount, and is unnecessary after a chest shot with a high powered cartridge due to the internal hemorrhage that results.