NEBRASKAland

August 1975

NEBRASKAland

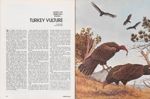

VOL. 53 / NO. 8 / AUGUST 1975 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Fifty cents per copy. Subscription rates $5 for one year, $9 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Single Copy Price: 50 cents commission Chairman: jack D. Obbink, Lincoln Southeast District (402) 488-3862 Vice Chairman: Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 2nd Vice Chairman: Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-Central District, (308) 745-1694 Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-central District, (308) 452-3800 H. B. "Tod" Kuntzelman, North Platte Southwest District, (308) 532-2982 Director: Willard R. Barbee Assistant Director: William j. Bailey, jr. Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: jon Farrar Greg Beaumont, Ken Bouc Contributing Editors: Bob Grier Faye Musil, Tim Hergenrader, Roland Hoffmann, Bill Janssen, Ben Schole Art Director: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1975. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska Contents FEATURES MISSOURI RIVER COUNTRY PRAIRIE VENGEANCE ON TRIAL 12 RIVER OF SAND AND SAUGER 16 YOUR WILDLIFE LANDS/SOUTHEAST A special 18-page section in color of certain public recreation lands 18 FISHING ... WHITE BASS TIME 36 PRAIRIE LIFE/AGGRESSION . NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA/TURKEY VULTURE 38 50 DEPARTMENTS SPEAK UP 4 TRADING POST 49 COVER: Two species of leopard frog are found in Nebraska. The northern leopard frog occurs primarily north of the Platte Valley near any permanent water, especially those with grassy shorelines. Photo by Jon Farrar. OPPOSITE: Having served man for hundreds of years, the windmill may yet be in its infancy as a tool for harnessing nature's power. This one is in the Nebraska Sand Hills. Photo by Greg Beaumont.

Speak up

Steamboat ArtSir / I was pleased when I opened the March 1975 issue of NEBRASKAland and found that my drawing of the steamboat Bertrand had been used to illustrate an article on prairie steamboats. I was, how ever, surprised that although the author saw fit to use the drawing as a two-page spread, he failed to even mention The Steamboat Bertrand by Jerome E. Petsche from which the drawing was taken.

Since the author apparently intended to stimulate interest in steam boating, he would have done his readers a service by citing this U.S. Government publication which is one of the most recent and comprehensive books on the subject.

Jerry Livingston U.S. Park ServiceThe story in our magazine was done by a non-staff writer, and we had no way of knowing where the illustration came from. Our thanks to you for the excellent art work, and for bringing the book to our attention. (Editor)

Good Old DaysSir/Am sending you two pictures from the so-called "good old days." One is a picture of Lester Tinkham taken about 1912 with a possession limit of ducks. They were taken on the 21 Lake in the Sand Hills southwest of Wood Lake.

The other is of me and a day's limit of 15 ducks taken about 1924 in the same country. If there are any old timers left at Wood Lake they will remember Lester and me.

My mother and her brother Ira Lawton took homesteads in the Sand Hills. I worked for the old 21 Ranch in the March 1913 blizzard that killed so many cattle. I also worked for Bill Ballard and several other ranchers. I am 79 now and retired here in Torrington. I sure like NEBRASKA Iand, as it often tells of the Sand Hills.

Ed Redifer Torrington, Wyo.Thanks for the old photos, which appear here, feathers and all. Seasons were some what different in those days, but I hope you still see plenty of ducks. (Editor)

Sir /I am a Nebraskan displaced by necessity and not desire. Every year I find some way to get back to the home state for a visit. Part of my vacation is spent there hunting, which is what prompts this letter.

I would like to get in contact with some people in the Kearney or Grand Island area who will permit people from way out to enter their property to hunt birds. A week's vacation does not give much time to get acquainted with the area or to find someone to let you in. I would be willing to take time before the season to call on them to get acquainted and to find the limits to their property and what their wishes might be.

I am in hopes that your magazine might help me to establish a contact.

F. M. Stearns 428 Indian Trail Aurora, III. 60506If anyone in south-central Nebraska is willing to host a gentleman hunter for a few days, please contact Mr. Stearns directly or let us know and we'll contact him. (Editor)

County CoverSir / I was born at Greeley, Nebraska, moved to Denver in 1936. I did get to visit Greeley this last August for a few days, and believe me I wished that I could have remained there, for Nebraska to me is the best state in the nation. It will always be home to me.

Enjoy your magazine very much but would like to see more articles on history and not so much concerning hunting and fishing.

One question-with the lack of cover for game birds, why can't each county set aside a portion of land and provide cover for these wonderful creatures? Surely in each county there is some land which is not good for agriculture and such. Just an idea, but worth thinking about.

R. P. Clinch Denver, Colo.I suppose there is considerable land in every county which could be allowed to revert to wildlife habitat, and it would be super if the respective counties would take it upon themselves to undertake such a project. Often, overgrown land looks "untidy", however, and someone feels it should be cleaned up. Unfortunately, this is the case with land in private ownership too, and with farm land, so that both the land and the wildlife get cleaned up or out together. By the way, we have several historical articles scheduled in the coming months, including this very issue (Editor)

NEBRASKAland Magazine invites all readers to submit their comments, sugges tions, and gripes to Speak Up. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters. - Editor.

MISSOURI RIVER COUNTRY

Rich, quiet area earns title "land of gracious living" by continuing trends of the past

IT'S NOT A LAND of cowboys and Indians or old cavalry posts or monuments to historic clashes between the red man and white. Nor does it shudder with the roar of big motorboats or ring with the thrill and excite ment of the ski slope.

As a matter of fact, it's a rather quiet place; probably too quiet for many seeking a place to spend their leisure time. For some, the idea of relaxation is racking up miles on the odometer heading for faraway places or inhaling lots of gunsmoke and rodeo dust at the customary summertime Old-West celebration. By comparison, the pace in southeast Nebraska's Missouri River Country would seem a bit slow.

But, an entire generation of midwesterners is getting its fill of the fast, the flashy and the noisy, especially if they hail from a city of any size. To them, the quiet and serenity of places like this are the perfect antidote to hectic modern living.

It's not that Missouri River Country is without color or history. There's plenty of both. It's just that the essence of this region permeates the whole landscape and is entwined into everyday living, not concentrated in a few spectacular places and events.

Houses and public buildings were built here while the Civil War was still raging, and they have remained in use to this day. In Nebraska City, for example, the Otoe County Court House still serves as the seat of county government 110 years after its construction. And nearly every locality has at least one old house, church, post office or commercial building listed in "Historic Preservation in Nebraska," the State Historical Society's official log of historic sites in Nebraska.

Looking at fine old buildings that have stood for perhaps a century or more, one feels that, even then, life here was somehow easier, more rewarding and more gracious than other places in the state. Many of the mansions have an aura of the "Old South" about them, or perhaps suggest Kentucky bluegrass country. The amazing part is, that there were such fine, highly ornamented wood and brick structures here in the 1860s, when other Nebraskans were still struggling to build crude sod houses on the prairies a quarter-century later.

Part of the explanation lies in the land itself. It's a rich place, with the fertility to produce good crops and a pleasant, green landscape. In addition to grain and other standard farm crops, there are hardwood stands, and orchards such as those in the Nebraska City area yield a bounty of fruit each year. Across the river in Iowa, industrious nurserymen have converted this bounty into a world-famous enterprise.

This part of the country also had a head start toward "the good life" because of its proximity to the Missouri. The river was the first corridor of the explorers, and was the artery that supplied the vanguards of civilization. While only the barest essentials like lead, powder, tools and whiskey could be transported overland to settlers, those along the river had the steamboats at their door step so they could order all of the niceties such as fine furniture, carpets and building materials.

Even today, with the steamboats gone and the man sions and other vintage buildings retired to museum duty, this stretch of Missouri River Country still seems to promise an extra ration of good living.

The scenery still has a soothing quality. The Missouri River and its bluffs dominate the scene. The river has been stabilized in a channel that hugs the bluffs on the Nebraska side, and miles of fertile riverbottom farm land separate the river from its bluffs to the east.

Nebraska's bluffs are wild places, with high ridges and steep slopes covered with timber. Often, the bluff ends in a sheer drop to the river below. It's a place filled with the music of songbirds and the scolding of squirrels. White-tailed deer find privacy there, while bobwhite quail distinctly announce their presence from the brush where timber and fields converge.

Beyond the bluffs lie gently rolling farmlands. Even here, the land seems determined to produce trees and shrubs. The countryside is laced with watercourses lined with oak, elm, ash, cottonwood, and a host of shrubs. Even the fields boast an extra bit of greenery, as many are bordered with a thick hedge of Osage orange.

Dotting the countryside are dozens of small towns and villages: Peru, Brownville, Barada, Shubert and Rulo on the Nebraska side, and Mound City, Craig, Corning and Tabor across the river. These places and the farmlands around them are homes of quiet, hard working, courteous people who mind their own business, but know when to offer a neighbor a helping hand.

It's no wonder, then, that people from the high pressure world of the cities are looking for places like southeast Nebraska, particularly Missouri River Country

and the immediately adjacent parts of neighboring states. With more leisure time available (and made necessary by the 20th Century pace), this land of gracious living offers the tonic needed to soothe contemporary nerves.

At least a couple of ways to take advantage of this rich store of leisure-time potential are readily apparent. One involves putting down roots, in a manner of speak ing, in a way that would enhance an area, rather than exploit it as so many other forms of recreation end up doing.

Like many other parts of Nebraska, the same small towns and villages that provide the rustic charm of the region are quietly struggling for their very survival. Since World War II, their young people have been leaving for jobs, colleges and careers in the bigger cities; entering the same hectic race that causes others to seek refuge. At the same time, their parents and grandparents who stayed behind were getting fewer, leaving the community short of people.

This depopulation of rural Nebraska communities has left a niche for those seeking solitude. Hundreds of substantial old houses are standing abandoned, which can be bought for very reasonable sums. With a little paint, a few tacks and nails here and there and some yard work, these homes could provide ideal weekend retreats, summer vacation homes, perhaps a place to live in retirement.

This idea of a second home is not a new one. For a long time now, people have been running off to cabins deep in the woods, high up on a river bluff or along some private lake or sandpit. And the Missouri River Country is ideal for this sort of thing.

But a new wrinkle to this scheme, with even more options for relaxation, is available in the area's small communities. A home in one of these towns or villages would serve as a base of operations for anyone wanting to fish, hunt, boat, hike or take part in any of the outdoor recreation opportunities along the river. At the same time, this home would introduce its new owners to the community's relaxing way of life, and would provide options for something to do other than the outdoor pursuits offered by wilderness cabins. And in time, the best reward of all would come to those deserving it—new friendships with people of the community.

For some, the very act of setting up such a home would be a rewarding experience. A special delight comes from watching an old house shape up as a result of your own time and labor. A bright coat of paint and a freshly manicured lawn would do wonders for the appearance of one of these houses, to say nothing of a new owner's sense of accomplishment.

New owners for these homes would be welcomed by the community, too, since they would keep the property from becoming an eyesore after a few years of neglect. A house in good shape is also worth more to the community on the tax-rolls, and the part-time residents would mean a little extra business at the grocery store, lumber yard or hardware store.

Besides offering a chance to relax in a "grassroots"

society, the rural community-based second home offers another advantage —economy. Many of these homes can be bought for a very modest price, certainly less than the cost of riverfront property, a new cabin, road, electrical lines and whatever other services might be needed.

Of course it would be foolhardy to simply pick a small town or village at random and buy the first house available. And for many, buying a second home is impossible financially, or simply not their "cup of tea," even though the Missouri River Country appeals to them as a place to visit.

In either case, it would be appropriate to drive down for a look. It would not be necessary, and probably not desirable for that matter, to try to see the entire area in one grandiose, two-week summer vacation trip. Missouri River Country seems to be better suited to visit in small, one or two-day excursions. Completion of Interstate 29 down the river's eastern bank provides rapid access to any general area, and bridges at Plattsmouth, Nebraska City, Brownville and Rulo then lead into the heart of rural southeast Nebraska.

The amount of time available for each foray would influence the destination. With just one day, travelers would probably look over one or two small villages and take in a bit of scenery. One day might also be enough to cover one city, such as Nebraska City with its Arbor Lodge, Old Fort Kearny, the old Otoe County Court house, Wildwood Park and its period house, the apple orchards and a number of other attractions. But, two days would make more sense if visitors wanted to see more of rural Otoe County, and perhaps visit or camp overnight at Iowa's beautiful Waubonsie State Park just across the river.

Another time, perhaps with a three-day weekend available, would be well spent in the Peru-Brownville Auburn area. Brownville is well known as an historic town, with mansions dating back to the river steamboat days of the 1860s, open for tours, just about every summer weekend, a theater, concerts or some other sort of event is going on. Riverboat excursions, camping facilities, fishing and picnicking are available at Brownville State Recreation Area at the edge of town. A short cross country drive to the north winds through scenic hills and farmlands, offering panoramic views of the Missouri River Valley before ending up in Peru, a picturesque community that is home to one of Nebraska's most attractive small college campuses. And across the river is Rock Port, Mo., and Big Lake State Park along with Tarkio, Mo., and the Mule Barn Theater and Museum.

Another few days might be devoted to Indian Cave State Park on the Nemaha-Richardson county line, and the Rulo-Falls City area might be worthy of yet another excursion.

Timing would be important on some of these out ings. Nebraska City's apple orchards beckon twice each year: in the spring when blossoms bedeck the trees and sweeten the air, and again in late summer when the trees give up their wealth of fruit. Most of the river

Charm of Missouri River Country is not all Nebraska's. Missouri and Iowa neighbors have long been aware of the region's riches in terms of wildlife, recreation and agriculture Photos by Iowa Conservation Commissionscenery is at its most spectacular in Autumn when the trees turn to splashes of red, gold, yellow, brown and orange. Indian Cave State Park is especially attractive then. It would also make sense to be in southwest Iowa during Sidney's rodeo and during open houses scheduled by nurseries in the vicinity.

Fall would be a logical time to visit waterfowl-management and public-hunting areas in the region. This part of the Missouri River is the focal point of the mid-continent migration route of blue and snow geese. More than 120,000 geese have gathered at Plattsmouth Waterfowl Management Area in Nebraska at one time. The birds also stop at Forney's Lake and Riverton Wild life Refuges in Iowa, and at Squaw Creek Refuge near Mound City, Mo.; perhaps the largest and most famous of them all. Some of these areas offer public hunting, and also provide opportunities for non-hunters to view the birds.

The agenda could go on and on. Excursions might go beyond the southeastern tip of Nebraska, perhaps to the White Cloud Agency in Kansas, or to St. Joseph, Mo.; eastern terminal of the Pony Express.

Development of more recreation in Missouri River Country may not be far in the future. Residents are show ing an interest in making their area more attractive, which is evident in the formation of groups like the Tri-State Missouri River Development Organization. One of this organization's primary purposes is to work for effective planning in recreation and tourism development.

A couple of Game and Parks Commission proposals might also fit well into the picture. One would be the development of a museum at Brownville State Recreation Area on board an old river dredge boat, the Meriwether Lewis.

This boat is largely responsible for "taming" the wild Missouri. With its mission now complete, it rests in drydock in Gasconade, Mo. It's a large old craft, nearly as long as a football field and some 80 feet wide. It would have ample room for museum displays portray ing the Missouri's role in the early fur trade, the Lewis and Clark expedition, the westward movement of civilization, the Indian Wars and modern commerce.

The Brownville location is ideal in several ways. The recreation area has a suitable piece of land where engineers could permanently situate the craft. Nearby highways would make it easily accessible, and the Brownville location would be especially appropriate because of the town's early history as a riverboat port. The proposal depends on Congressional action in Washington, however.

Another Commission proposal for the region involves a "strip park" for this stretch of river.

Perhaps the best way to explain the strip-park concept is to compare it to a conventional park. The parks we're all used to attempt to be all things to all people, with playgrounds, campgrounds, golf courses, tennis courts, swimming pools, fishing lakes, wilderness areas and all sorts of other attractions. By the time everyone arrives to "do their thing", the place is often as crowded and hectic as the places from which they seek refuge.

The Missouri River strip park, however, would consist of a series of areas all along the Missouri, each offer ing just one or two attractions. Most would offer just enough to do for one or two days, or perhaps several small attractions in close proximity might provide a full day's recreation.

Under this concept, travelers could make a leisure ly tour of Missouri River Country, skipping things that are not seasonal or not of interest to them. They could cover whatever parts they wish at their own pace —a day here, a weekend there.

Many of the facilities already exist on Game and Parks Commission lands. There's Plattsmouth Water fowl Management Area at Plattsmouth; Riverview Marina and Arbor Lodge State Historical park at Nebraska City; Brownville State Recreation Area, and Indian Cave State Park. Across the river, state lands include Forney's Lake and Riverton hunting areas and Waubonsie State Park in Iowa, and Big Lake State Park and Squaw Creek Refuge in Missouri.

There are also recreation facilities and historic at tractions operated by communities or local civic organizations that should be looked into. And, private campground and commercialized attractions might hold some potential.

There are also other lands that might be incorporated which could provide cross-country hiking or bicycle trails. These include property of the Corps of Engineers along the river, and county road right-of-way. And, of course, the Game and Parks Commission might have to lease or buy some land in the area. Even "Sun day drivers" could be accommodated with the marking of a route through the most scenic of the farmlands, timber, bluffs and river valley.

In reality, this strip park might not be far in the future. Many of the physical facilities are already there. The main development needed is a new attitude among those looking for leisure; an attitude that would send them away from the big, all-inclusive conventional park once in a while and allow them to find their own enter tainment on a strip park such as this.

There need be no shortage of things to see and do in Missouri River Country. But, the attractions should not overshadow the real reason for being there —the search for that soothing way of life found exclusively in a country setting.

Perhaps you might find it while sharing a quiet riverbank with DelbertClifton, his 6-year old son, Delyn, and their dog Cocoa as they catfish not far from their Brownville home. Or, it might come in Nemaha during a chat with Herman and Rosa Boden as they work in their garden. Or perhaps a resident of Union or Peru or Shubert or Rulo or some other quiet little community might point out that special spot you're looking for.

Past generations once enjoyed an extra helping of gracious living in Missouri River Country. Given a chance, this region could do the same for us.

10

Cowmen and nesters were at each others throats and any spark could set off a range war. Then, the ranchers hanged and burned two settlers

Prairie Vengeance on Trial

NIGHT WAS CLOSE at hand as the wagon jolted along the trail that led north into the endless stretches of the sandhills. An unusual chill was in the December air; caused perhaps by the cold wind out of the north, perhaps by the ill-fated party that rode the trail that night. Hardly a word was spoken. Only the canter of the horses and the creaking of the wagon broke the silence. The two men in the back of the wagon were handcuffed and one of them wore a heavy overcoat. The other shivered and hunched forward as the mounted riders on either side pulled their coats tighter for protection against the icy wind.

Abruptly, as the leader signalled, the horses were turned into a small canyon and the wagon was pulled to a stop beneath a small tree. The leader, a small, swarthy man, ordered the men to stand, and a rope was placed around the neck of each. The other end was thrown over a low hanging branch. At this point the leader spurred his mount forward, rifle in hand. Placing the muzzle against the older of the two men, he fired, killing him almost immediately. Then he gave the signal to move the wagon and both men were swinging in the frigid night.

The riders watched until the jerk ing and twitching ceased, then they turned up the canyon. Hangings, as a part of frontier justice, were not unusual in themselves, but this par ticular night was destined to be long remembered.

The hanging turned out to be a grotesque turning point in the war between the settlers and cattlemen on the Nebraska plains. All of the in gredients for bloodshed were there. Isom "Print" Olive, the hangman, was a tough, morose, hard-drinking Texan who had driven thousands of cattle up the Old Chisholm Trail. Schooled in war and killing, he be lieved in gun law and used it to up hold another belief: that the open range was for cattle and should not be put to the plow or enclosed with barbed wire. He had settled in Ne braska only recently, with expectations that rustling would be less of a problem than on the spread in Texas where range wars were imminent. With gun in hand, he was determined to rule the range and he was ably as sisted by his brothers, Bob and Ira; Bob traveling under the alias "Bob Stevens" after having killed a man.

As the settlers moved in on the blue stem country with their soddies and plows, the ranchers grew apprehensive.

Soon, rumblings of discontent could be heard. Veiled threats were beginning to reach the ears of the settlers and it was not totally unexpected when Print accused an old home steader of stealing Olive cattle and gave him a beating. This struck fear into the hearts of a few and they loaded their belongings and pulled out.

Among those who stayed were Ami Ketchum and Luther Mitchell. Ketchum was in his twenties and was engaged to Tamar Snow, the attractive stepdaughter of Mitchell. They had filed two claims to the north and east on Clear Creek and their sod house was built in such a way that it straddled the boundary line of the properties. Others moved into the area, found Clear Creek to their liking and settled there. A tiny community had formed and Ketchum and Mitchell were the central figures.

A pressure cooker was building and the lid would soon blow with such unexpected repercussions that the entire nation would feel the shock waves. The harassments continued and one day Olive longhorns were found in Mitchell's corn. Shortly after that, a mysterious range fire broke out and left many miles of blackened range land in its wake. Tempers flared and nerves were stretched to the breaking point. Ketchum and Mitchell were openly warned that time was running out for them. As threats and annoyances continued to the point of intolerance, another element entered the boiling episode. It became more than just rumor that Ketchum and Mitchell were selling butchered Olive cattle at the markets in Kearney.

Print Olive had been in the law courts almost as much as the lawyers in his lifetime, and he decided to get the law on his side. After several details were agreed upon, it was ar ranged with "Cap" Anderson, sheriff of Buffalo County, that a posse would be sent to arrest Ketchum and Mitchell. Bob Olive, alias "Bob Stevens", would be the deputy and would have his pick of men for a posse.

On the appointed day, Bob and some Olive cowboys rode to the site of the settlers' home on Clear Creek. "Sheriff" Bob gave the signal and the

12 NEBRASKAland AUGUST 1975 13

Olive posse galloped into the yard as Bob yelled to the settlers to throw up their hands. Almost immediately gunfire broke out and Ketchum took a bullet in the arm. Mitchell began firing and scored, to his lasting regret. His target, Bob Olive, slumped in the saddle mortally wounded. As they saw Bob's plight, the cowboys abandoned the attack and turned and fled, holding Bob in the saddle. When they reached Print, he took charge and the party set out with all possible haste to transport Bob to the nearest medical help. All efforts were in vain and he died, the victim of a settler's gun.

Print was grim and sullen at Bob's death. Jay, Print's brother, had died during a night attack on their spread in Texas, and in the days that followed, those who were under suspicion began to disappear. Some had been shot; others were never found. Clearly, vengeance could be expected. At his headquarters on the South Loup, Print organized the search for Ketchum and Mitchell, offering a $700 reward for their capture.

The settlers had fled with the in jured Ketchum in the back of a wagon. They knew that retaliation could be expected, and in desperation they headed for Loup City. They were familiar with the country and Judge Aaron Wall lived there. At the Wall residence they were greeted warmly and given food, but warned that the Olive gunmen could be expected soon. After some discussion, it was agreed that their chances would be better if they would travel on to Central City and turn themselves in to Sheriff Letcher, who would arrange for their return to the jail in Kearney. There they would stand trial. With this arrangement, they felt better. At least they would not be hunted down on the prairie like wild animals.

So it was that they rode the train back to Kearney and directly into the hands of Sheriff Anderson, friend of the Olives. When this news reached Print, he was elated. He contacted Barney Gillan, Keith County Sheriff and close friend, and arranged for Ketchum and Mitchell to be brought to Custer County, site of the shooting, for trial. A Plum Creek attorney, C. W. McNamar, had agreed to serve as lawyer for Ketchum and Mitchell.

The prisoners detrained at Plum Creek and were put on a rig for the trip north into Custer County against the strong objections of McNamar. Sheriff Gillan and Phil DuFran, a Custer County deputy and cattle man, were in charge. As they drove north out of Plum Creek, McNamar followed in his wagon. There was a brief rest stop at a ranch and then they rode on as darkness settled over the prairie. The trail was barely discernible now and the distance between the two rigs was gradually increasing. Eventually, the rig with Ketchum and Mitchell was lost from sight. As McNamar drove on north, he was aware of riders from behind and he recognized Print Olive as they swept by. He drove on north but there was no longer a wagon in front of him. It had turned through Devil's Gap and into a small canyon. It was December 10, 1878, and Luther Mitchell had fired his last gun. Ami Ketchum would never again stroll through the moonlight with Tamar Snow.

McNamar had lost the trail of the prisoners, and fearing foul play, he organized a search party the next day. The group was apprehensive to say the least, but they were ill-prepared for the grisly sight which met their eyes when they came upon the two men. It had been no ordinary hang 14 NEBRASKAland ing. The two had been set afire and were badly burned. Mitchell's body had fallen to the ground and was more severely burned than that of Ketchum. They were still manacled together. The party took notes and made observations before leaving.

When they arrived in Kearney, the bodies were left outside a funeral home for several days. It was there that H. M. Hatch, Kearney photographer, took pictures of the burned corpses. Soon people were reading in newspapers across the state and nation about the repulsive "man burning" episode on the Nebraska plains.

Print Olive was secure if not over confident of his power on the range after the hanging.

Events of the last few days had turned Print into a braggart who be lieved more than ever that no power on earth could touch him. In this state of mind, his arrest came like a bolt out of the blue. As he walked the streets of Plum Creek one morning, he was surrounded and placed under arrest before there was any chance to draw a gun. Immediately after his arrest he was introduced to his captors, the brothers of Ami Ketchum.

Five others were taken into custody that day: Fred Fisher, Print's foreman, Bion Brown, and Barney Arm strong were all Olive riders. John Baldwin, a Plum Creek hotel owner, and William Green, a saloon operator, had gone along to see the hanging. They were placed under in dictment as witnesses.

The Attorney General of Nebraska, Caleb J. Dilworth, had planned the entire operation under such tight security that all prisoners were hand cuffed and placed on a special train before there was any possibility of a rescue effort. They were taken to the penitentiary at Lincoln for safekeep ing until their trial.

Judge William Gaslin was administrator of the Fifth Judicial District and would preside over the trial. He handed down other indictments, and among those charged were Sheriff Barney Gillan and Deputy Sheriff Phil DuFran. Both were friends of the cattlemen. Shortly before the trial was to begin,^Gillan mysteriously escaped and was never caught. Judge Gaslin, meanwhile, was concerned about the turbulent situation in Kearney and decided to move the trial to Hastings in Adams County where there would be less chance of outside interference.

An impressive battery of lawyers squared off in Liberal Hall. Print could afford the best, and he hired such prominent men in law as Judge Beach Hinman, Francis Hamer and James Laird. Against this imposing array of talent stood Attorney General Dilworth and John Thurston, a speaker with few peers.

Jury selection was a time-consum ing process. It was difficult to find unprejudiced individuals, and Olive's reputation was such that few men were willing to risk jury duty.

From the start, the prospects were not bright for the defense. Testimony by the many witnesses was damaging and the attempt by the prosecution to place Olive and his men at the scene of the crime was alarmingly success ful. It was known that the prosecution would seek the death penalty, but even as these initial successes were scored, James Laird brought up the issue of jurisdiction for the defense and he pressed it with regularity, little knowing how critical it would be in the future.

During those early phases of the trial, the fearful spectre of Olive vengeance rose again. Rumors were fly ing that a lawless band of riders was on the way to rescue the prisoners and reduce the little town of Hastings to ashes if need be. Large numbers of cowboys and strangers on the streets added credence to the story, and whether or not a rescue attempt was in the offing, Hastings residents were getting edgy. It was reason enough for the governor to receive a telegram requesting that troops be sent with all possible haste. An order was given to General Crook at Fort Omaha and he lost no time dispatching troops to Hastings. In Past and Present of Adams County, Judge William Burton gives some interesting sidelights of the events that transpired:

A patrol guarded the jail, a small wooden affair standing on the south west corner of the present courthouse square. Prisoners were handcuffed and marched two by two when escorted to and from the courthouse. Spectators lined the way, many of them women, and remarked on the appearance and character of the men. At intervals the bugle of the military might be heard all over the town as the guard was changed.

Next to Olive and Fisher of the men tried here the Mexican, Pedro Dominicus and the negro are best remem bered. The Mexican was a one-eyed man and peculiarly vicious in appearance. The negro insisted on sing ing in a loud voice whenever there was an opportunity and it was his habit to clamber up to the high windows of the jail from where his strong voice could be heard many blocks.

One interested trial spectator was a small boy who sold peanuts to the hungry visitors to the court. He kept his eyes upon the prisoners and law yers when the stress of business permitted. Then and there he resolved to become a lawyer. He never changed his mind and in due time he came to preside as judge over the very same court in which his ambition was awakened. The boy became judge Harry S. Dungan, Judge of the Tenth judicial District.

Print's contact with the courts had previously been of an amiable nature, for he had been among associates and allies where his influence was felt. Now he had misgivings. McNamar's testimony had been decisive in placing Print in the general area at the time of the hanging when he told of recognizing him (Continued on page 42)

River of Sand and Sauger

Though shrunken to little water and much sand by drought last year, Platte River was good to Bill Pearson and crew of fishermen

IT WAS LIKE VISITING a staid old hunting and fishing buddy, only to find him weak and sick and shriveled. That feeling came over me last summer as I broke out of the timber and took my first close look at what was left of the Platte River.

It was late July, and most of Nebraska was wilting under a relentless drought and scorching to a dead, dusty brown. Even the Platte, which takes hot, dry summers almost as a matter of routine, was suffering more than usual.

In fact, parts of the river had already been declared in a state of emergency, and hope had been abandoned for survival of most of the fish in those areas. The river from Central City to Columbus was opened to fishing with spears, dip nets and hand fishing so that fish trapped in holes, and facing death due to oxygen depletion, would not go to waste. And officials did not even bother with such measures for another distressed area upstream from Central City, where there was no water flow, few holes to hold water, and consequently, no fish.

Our part of the Platte was more fortunate, however. Though it had shrunken to a fraction of its normal volume, the river was being kept very much alive by flows from the Loup River drainage and other smaller tributaries. Most of the river bed was a half-mile-wide band of dry sand, but there was a band of water perhaps 20 or 30 yards wide and a couple of feet deep meandering between the banks.

I was tagging along with Bill Pearson of Wahoo, an old outdoor sidekick of mine who has probably forgot ten more about the Platte than most people will ever know. Others included Bill's son, Jon, who was visiting from Colorado, Bill's son-in-law John Norris, and Bill Jurgens, Danny Wright and Lynn Wright, all of Wahoo.

We were after the sauger that live in the Platte be low Columbus. Just the day before, Jurgens and the two Wright brothers had found a deep, dark, wide hole in the river full of hungry sauger, and had enjoyed a good evening of fishing. Now, we were hoping to duplicate their success.

I had known for some time that sauger lived in that part of the river, but I always thought that minnows would be the way to fish for them. Tossing an artificial into the Platte seemed almost unthinkable; downright un-American, in fact. Even Bill, who had spent maybe 40 years on the river, couldn't recall seeing anyone successfully fling hardware there.

But when Jurgens showed us the little daredevles they had used to nail their sauger the day before, the rest of us began rummaging through our tackle boxes for something similar. Of course, my tackle box had just about everything in it except the lure I needed, so I had to con Bill out of one of his extra spoons.

The pool in front of us was a rather large one, considering the state of the river. It must have been 75 yards wide and a couple hundred yards long, and was along the south bank.

At first, it looked as if we might really be in for some red-hot action. While the rest of us were still poking around in our tackle boxes, Lynn stepped a few feet up stream, lobbed a spoon into the river, and landed the first sauger of the day.

The rest of us slammed our tackle boxes shut and started tossing hardware real pronto, but five minutes of concentrated effort failed to produce another fish. Lynn's fish proved that sauger were there, and that they could be caught. But, we also learned that we'd have to work a bit for them.

Soon, the party split up, some head ing upstream in search of other holes, and others going downstream. Jon explored downstream a bit, then came back and selected a comfortable spot to watch, snooze and kibitz, since he'd forgotten to pick up a fishing permit. Bill, Lynn and I decided to stay with the hole we had found initially, but headed for the sandbar on the opposite side where we could maneuver without hindrance of trees,

brush or the sharp river bank. Even though the pool was a good sized affair and water seemed to be mov ing well in the limited channel, I had some misgivings at (Continued on page 42)

18

18

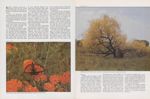

Your Wildlife Land The Southeast

Ranging in use from waterfowl management to fisherman access, wildlife lands are designed for people. Unlike park areas, they are not fancy or developed for extended use, but rather of fer a respite from civilization and a chance to commune with nature. Following is a break down of those lands in the southeastern part of the state, with an idea of what can be found there. Then, whether in terested in trees or fish or birds, and whether they are for watching or catching, they will be available. These are public lands, acquired for special uses, and controlled by the Game and Parks Commission. There are other areas designed for recreation, but these are aimed at the more quiet uses such as camping, fishing and hiking. Hunting is allowed on most during season, but the real value of these lands is solitude for exploring, beauty for viewing, and wildlife habitat for both the animals and humans to enjoy

SILENCE. Nothing moves but a mourning wind and tall, prairie grasses undulating in its hot blast. Yet the grass is everything, and everything moves.

Prairie was movement. Wind mourned through the grasses, a lonely spirit in lonely hillls. Prairie could be a young man standing on a hill crest, surrounded by movement. The prairie touched him.

Heat enveloped blowing clumps of brown-eyed susans and butterfly weed, but couldn't wilt them. The lonely hills were rich with life.

A red buffalo, as the Indians called fire, ran through the grass occasion ally, clearing a choke of undergrowth. Yet under the soil, life endured the fire, awaiting the cool rains. And when the rains didn't come, the wait was only longer. Roots remained, many feet under the soil — seeds were viable

Photo by Carl Wolfefor years, enduring drought in dry, prairie sod. Dry grasses rattled, tinder for more fires. But the prairie lived.

For centuries, the prairie lived that way, with only fires and Indians to disturb its rhythm. Then came the plow and the cow. Grass gave way to corn. Alfalfa replaced prairie hay. Families struggled on the land, changed it. They made it produce crops and livestock, the basic necessities to feed themselves and the cities. The country expanded.

But there was much in the prairie that was good; a natural balance that maintained itself without the manipulation of man. Today, in Southeast Nebraska, where ruts of the Oregon Trail pass, the buffalo have disappeared, but the prairie remains in small, representative areas —the wild life lands. Prairie fires no longer sweep out the old grasses and trees. River and stream banks are lined with oaks and hickories that gradually migrate upstream.

In the tree-brush cover, among remnants of osage orange and multiflora rose hedges planted by farmers to hold the soil, are quail. In the oaks and hickories along the river bottoms are squirrels, and maybe some foxes.

Southeast Nebraska is hilly country, swept by winds, covered by fragile, glaciated soil. The hilly, fragile soil has made the farmer careful. Fields are small, there are terraces to farm around, more odd areas. Good conservation practices hold the land.

The state's two major metropolitan areas are located inside the district. Outdoor recreation opportunities are centered now on Salt Valley Lakes, the wildlife and recreation lands along their shorelines, and on a few prairie areas of various types to fill

Photo by Jon Farrarthe gaps.

Wildlife lands encompass a wide variety of spots from a waterfowl man agement area, where thousands of geese stop off during their migration, to acres of prairie where a remnant flock of prairie chickens remains. Southeast Wildlife Lands include a waterfowl production area at Smart weed Marsh, and a few spots along the Blue River where fishermen can get to the water for cat and carp fish ing, along with several parcels of rail road right-of-way where wildlife can nest and raise broods. There are acres and acres of grass and trees surround ing the Salt Valley Lakes where dog training and trial facilities are offered. Captive Canada goose and wood duck flocks provide waterfowl for stocking, and a plant nursery supplies stock for wildlife areas throughout the state.

There are about 14,000 acres in wildlife areas in the Southeast with springs, lakes, and a rich intermixture of wild plants and animals that are the reason for wildlife lands to exist.

There are no sophisticated develop ments, no playground equipment, no modern restrooms, no camping pads, and no electrical hookups for camper trailers. There are outdoor experiences to be savored and shared.

A guide to the Southeast Wildlife Areas follows. You will find a description of recreation possibilities, and the wildlife and plants that you will encounter as you explore Southeast Nebraska.

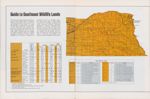

Guide to Southeast Wildlife Lands

The map and charts give approximate locations of the wildlife lands in southeast Nebraska. Recreation areas and parks are not included in this section. If a more detailed map is needed for the Salt Valley or Iron Horse Trail sites, separate bro chures are available from the Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebr. 68503. Wildlife lands are managed for specific pruposes, which are wildlife production and public hunting, fishing, camping, etc. They have a minimum of maintenance, and it is therefore impor tant that visitors make as little impact as possible —no littering, vandalism and similar destructive behavior. Waterfowl production or refuge is becoming more important on some areas, but each of the sites has a primary use. On some, such as Plattsmouth and Twin Lakes, this main use changes with the season. Access is open year-round on most, however, and there is some form of recreation to be enjoyed on them regardless of the season

Salt Valley

PEOPLE. More than 150,000 persons in Lincoln alone. Recreation in the Salt Valley is geared to large numbers of people and centered on a series of reservoirs in the Salt Creek watershed.

Still, there is room for wildlife in the Salt Valley, and room for primitive outdoor experiences. The undeveloped portions of recreation areas have been turned over to the manage ment of the Resource Services Division of the Game and Parks Commission. Other areas have been managed in total by this division —the wildlife lands.

Some of the Salt Valley Lakes have been intensively developed with many recreation facilities, including boat ramps, picnic tables, rest rooms, drink ing water and so on. Others have only modest developments. People crowd into the recreation areas on weekends, evidencing their desire for outdoor experiences.

There are over 10,000 acres of wild life lands bordering Salt Valley water. In an area of the state with large numbers of hunters and increasing acres of private land that is closed to hunt ing, that is not enough, but it is a welcome chunk of public land for hunting. Fishing waters are few out side the Salt Valley. Opportunities for hiking, camping, viewing and photographing wildlife, would be slim in the Lincoln area if the Salt Valley wildlife lands did not exist.

Salt Valley means all these opportunities on lands that are carefully planned to include both recreation facilities and wildlife areas.

A recreation area is made for people. The grass is mowed, unsightly dead limbs and trees are periodically removed. Debris is cleared away, and facilities are provided for people comfort, including fire grates.

But next door, across a highway maybe, are wildlife lands. Grass may not be "high as an elephant's eye", but pheasants and quail can live and hide in it. Dead limbs and trees are permitted to fall at their leisure, mean while providing food for worms and insects, which woodpeckers eat in their turn.

For the camper who prefers a bit of isolation, the wildlife lands offer plenty of open space where he can set up his tent and campstove. But that's all incidental. People must conform to the wildlife areas because they are a product of nature, not man. They

Photo by Lou Ell Photo by Jon Farrarare managed for wildlife.

Waterskiers and sailboaters like Branched Oak Lake proper, but the avid fisherman is likely to prefer the little coves and quiet areas where power boating is limited to five miles per hour and dead trees and weeds are permitted to stand. That's where the fish are. That's where the shade is, too. Trees overhanging the bank shade the water, the fisherman and the fish under the surface.

Lots of things are happening on the south arm of Branched Oak Lake. Captive flocks of Canada geese and wood ducks are producing goslings and ducklings for free-flying flocks of both on the Salt Valley. Already, the ducks and geese stocked at Twin Lakes are nesting.

Adjacent to the duck and goose pens are nurseries for trees to be planted on wildlife lands throughout the state. These are the trees that are not available from nurseries; trees that are especially propagated to grow in Nebraska. Valuable nut, hardwood and fruit trees grow strong in the nursery before they are replanted on other areas where they are expected to "grow wild" with a minimum of tend ing. Herbaceous plant materials are also propagated in the nursery. This is where the Game and Parks Commission gets rare plant materials for replacing native wildflowers and shrubs on areas that have been farmed or otherwise disturbed. Rows of butter fly milkweed and creeping juniper will provide seed and cuttings for more flowers and shrubs.

In addition to other "facilities" on Salt Valley reservoirs, there are two dog training areas —one on Wagon Train and another at Yankee Hill, where hunters can exercise and train their dogs. On Branched Oak, the Commission also maintains a nation ally recognized dog trial area. These areas receive minimal management, with mowing occasionally to prevent choking overgrowth that would hamper the dogs' work.

The Salt Valley also offers refuge for waterfowl. Twin Lakes is closed to all hunting the year round, and some of the south arm of Branched Oak is closed as posted throughout the year. Stagecoach and Conestoga are closed to waterfowl hunting. Artificial nest ing has been provided on wooden rafts and posts on the lakes for geese, and in boxes for wood ducks. Hope fully, the cry of the wild goose will someday be commonplace even as close to the metropolitan area as the lakes. It is hoped that the wood duck's soft whisper will be heard around the edges of the reservoir.

Iron Horse Trail

IRON HORSE TRAIL is not a single strip of land, but rather a series of 33 parcels scattered from DuBois to Beatrice. They are parts of an old rail road right-of-way. Along the trail are a variety of soil and vegetation types from woods to grasslands.

Access to the trail is often dirt, and when it rains, visitors have to be a little careful about vehicle travel.

But, perhaps that's part of the attraction of Iron Horse Trail. The winding, tree-lined road to tract 112 is part of being in the country, just as the tiny town of DuBois is anything but urban with its iris-decorated yards.

A cinder path down the center of the tract is evidence of man's passage, but it is almost entirely overgrown with plum thickets now.

Tract 106 probably offers the most variety along the trail. Weathered railroad ties lie in a jumble, waiting to be reclaimed by decay. Here, a casual stroll to the Nemaha River will reveal flashes of color from a dozen different songbirds. Bobolinks' clear, bubbling call will sound like water for just an instant, encouraging the visitor who still has a long walk ahead. Cardinals and bluebirds, and downy wood peckers, share the area with brown thrashers and sparrows.

Rabbits and bobwhite quail aren't overanxious about visitors, and several of them are likely to cross the trail during a walk to the river. A squirrel may even be spotted eating a walnut in a nearby tree. Occasional heavy rustles bring deer to mind.

Snails and clams by the millions must inhabit the Nemaha River, for their shells are strewn throughout the tract. High water frequently floods portions of the area, leaving behind debris of aquatic life. Raccoons leave footprints in the riverside clay.

All along the strip, wildlife uses Iron Horse Trail. Hunters striding through the tracts may push animals to adjacent farmlands, but when the trail is quiet again, they return. Pheasants and quail use the tracts for sunning and dusting areas. Trees and shrubs edge on adjacent croplands where wildlife can feed.

On tracts 29 and 31 near Beatrice, a little creek provides a pocket for hardwood trees like oak and walnut. Squirrels are likely to be found any where on the area.

As the parcels get farther from water, cover changes. Iron Horse is a good study in varying habitat, and its transition from river and stream bottom to prairie. Wooded areas give way to shrubs like sumac with its fall flame, to plum and chokecherry with their frosted fruits. Even dogwood, bittersweet and Virginia creeper tangle with wild grape in a rich plant community where fall paints with vivid color, from white to orange to purple.

Then the shrubs give way to grasses and forbs. Roundhead lespedeza and goldenrod mix with bluestem, switch grass, and foxtail, but the wildflowers are only tiny spots in the blanket of tall grasses; bluestem, switchgrass, and Indian grass. It is a place for pheasants and rabbits to build their nests.

Iron Horse is leftovers, abandoned by the railroad; its original use is ended. But the wildlife that uses it doesn't mind —wild animals and plants have their own uses for it, living together for the hunter and hiker to enjoy.

Photo by Jon FarrarPlattsmouth

GEESE. SQUAWKING, honking geese. By the tens of thousands they stop at Plattsmouth Waterfowl Management Area each fall. But the sound is not a distant, wild gabble it's a clamor which reaches its crescendo with an average peak population estimated at 100,000.

Plattsmouth is a waterfowl refuge, with controlled perimeter shooting. Some 2,000 hunters used blind facilities there in 1973, and about 1,400 geese were harvested.

The area is intensively managed for geese. Game and Parks Commission personnel manipulate crops to suit the tastes of geese. No royalty has sat down to a more carefully planned and prepared cuisine. Wheat is interspersed with corn in a pattern that varies from year to year. Since snows and blues are reluctant to feed in a closed field, corn is harvested in strips — opening 16 rows and leaving 8.

Besides the comforts of food plots, the geese enjoy a 25-acre lake on the area for loafing and resting.

Hunters of several types enjoy Plattsmouth. Human hunters, especially beginners, have an opportunity to participate in goose hunting with out the search for a site. Although blinds are already in place, hunters must take along a thorough knowledge of their weapons and of their game.

Eagles and coyotes hunt Plattsmouth too. Diseased or crippled geese provide most of their meals.

Photo by Greg Beaumont

Photo by Greg Beaumont

Hunters are not the only people encouraged to visit the area. Many visitors bring only cameras or binoculars. On Wednesday and Sunday afternoons, local personnel conduct scheduled tours. Afternoon hunting has not been permitted there recently, allowing geese to feed undisturbed.

Though goose- concentrations are the major attraction, Plattsmouth has other uses as well. During the day-use season, April 15 to September 15, fish ermen use the area for access to the Platte and Missouri rivers where they take many good catfish. The lake and several smaller ponds offer carp and bullheads, some crappie and bass.

Several picnic areas are located on the west perimeter, near the trees. A nature trail winds through the timber.

But, still, Plattsmouth would not be Plattsmouth without its geese. Every year the quiet little area comes alive with the incredible, unexplainable migration of thousands of geese. And every year they leave it again, silent and stripped, to await their next coming.

Smartweed Marsh

SMARTWEED MARSH, nestled in surrounding croplands among acres of corn, milo and wheat, is but one of thousands of rainwater basins in south-central Nebraska. Just south west of Edgar, Smartweed is only 80 acres, but it's big enough to bring off several broods of ducks in good years. In dry years, it offers good edge for pheasants.

A marsh seems an inactive place at first glance. The water stands instead of running; plants just grow, reflect ing their bodies in mirror-smooth water.

But then come evening breezes. Somewhere on the far side a duck quacks; four squawks, then silence. Nearby a muskrat ripples quietly through the bullrushes, barely waving their stems. A red-winged blackbird warbles from a scrubby willow switch. A silent mink glides behind a slow, half-grown duckling; then sudden splashing as he takes his quarry. A single frog begins the evening chorus along the edges of torpid water....

Then comes November, and hunters. An old man and a boy sit hunk ered down in the tall bullrushes. Dawn is but a few minutes off. They can hear the ducks, the summer's hatch, the fall migration. "Now, don't shoot," the old man cautions, "until you can tell what they are. Mallards are big. You should know their pro file; we spent enough mornings out here last spring...."

The sky shows a bare hint of gray. As Aldo Leopold said: "In the marsh, long, windy waves surge across the grassy slough, beat against the far willows. A tree tries to argue, bare limbs waving, but there is no detain ing the wind".

The ducks are coming through the rising morning bluster, teal rushing by on erratic wings; pintails almost out of sight before they're seen; then mallards, and more mallards. It's the boy's first duck hunt.

Fisherman Access

YOU GET THE LINE and I'll get a pole—" There's a line in an old song like that, and some of the best examples of the fishing hole are tiny wildlife areas purchased by the Game and Parks Commission to provide fishermen access to the Blue River.

Blue Bluffs and Shady Trail are two such areas. Both of them are on old power dam sites, with remnants of the structures still in place. Both man and fish benefit from these remains of a

Photos by Jon Farrar

past use.

They're quiet, pleasant little places with good cat and carp fishing water and lots of shade. A few birds might serenade you as you tote your tackle box and fishing pole downstream to the edge of the area, where you've spotted a place that's unoccupied.

You might exchange pleasantries, or maybe a few fish stories, with an glers who are already there. "Catchin'

Or you might take the family along and picnic adjacent to the river before you start fishing. Take the kids along and let them poke around in the shade.

Dusk settles on an old fisherman, his pipe puffing occasionally. He learned patience with a fishing pole in his hand. It seems to belong there.

Prairie Areas

Photo by Faye MusilBENEATH THE WAVING sea of grasses are thousands of lives...I see the evidence everywhere, though I seldom see a living animal. Here a coyote or a fawn laid on this hillside overlooking the draw. See how the grass has been mashed down by his body? Here is a mourning dove nest, a little circle among a blanket of rustling heads. Look how the grass parts here. It's a tunnel for some kind of mouse or shrew, maybe a prairie vole. It's his highway, or maybe the entrance to his kitchen."

The prairie seems monotonous; grasses all seem the same on prairie wildlife areas like Pawnee Prairie, Burchard Lake and Alexandria. Trees only inhabit the draws, shrubs are few, and grass is everywhere.

Yet, the silent calm of the grass lands hides a centuries-old conflict that is renewed yearly. Warring species of plants never establish victors, nor are any ever entirely conquered. Year after year, they struggle bitterly for the essentials of life. They claw to ward sun and stretch toward water, fighting all the while for nourishment from the soil. They crowd each other. Like rush hour traffic they push and shove, but all are silent. And their crowding leaves them dwarfed and underdeveloped compared to what they could be in another environment. Yet they are tough and healthy.

The natural balance of prairie plants makes it a closed community; safe from invasion by other species, safe from drought, safe from fire.

The community is an interdependent one with tall plants shading smaller ones, and mat-forming grasses shielding the soil and slowing evaporation of precious water. Slender leaves of dominant grasses filter sunlight to short grasses and forbs.

Prairie plants are conservative. They require little water and small amounts of nutrients. Their stems and leaves catch rainwater. They permit little runoff and prevent evaporation with their dense, protective ground

Photo by Gene Hornbeckcover. Flowers take turns blooming, reducing competition. Underground, the prairie is a rich mosaic of intermixed root systems. Tough rhizomes provide food storage for harsh times. Fibers reach for water seven feet and more into the soil.

As prairie plants have their storage rooms beneath the soil, so the prairie provides rooms for wildlife. The entire grassland is a dining room for numerous kinds of birds, with grass and forb seeds as table fare. Rodents dine on stems and leaves.

Water is shelter to beaver, and little ponds are scattered throughout Paw nee Prairie —glistening pools of water where beavers have dammed the tiny creek, or man has built his earthen structures. A cacophony of loafing frogs is suddenly silent as a hawk's shadow glides across their logs and shoreline.

Water is clear and clean here. Pounding rains cannot reach the bare soil through its thick umbrella of plants. Little silt is permitted to wash away. A series of springs water Alexandria, where the resultant tiny stream runs along a sandy bottom and raccoons leave tracks in the granules.

Water at Burchard Lake is stored behind a small dam, built with federal matching money under the Pittman Robertson and Dingell-Johnson programs. Local sportsmen contributed a portion of the funds needed to purchase the area. Nestled between

Photo by Carl Wolfe

Photo by Carl Wolfe

prairie hills, the water attracts water fowl in fall, and fishermen through most of the year. Managers say that Burchard Lake is unique because there are very few vandalism or litter incidents there. They speculate that local involvement has created a greater local interest in the upkeep of the area.

Late in April, when the cattail shoots are but a couple of inches high, a new sound adds dimension to contemplation of the prairie areas. Quiet mornings bring prairie chickens' boom wafting across the gentle grasslands on an almost imperceptible breeze.

On a hill adjacent to Burchard Lake is the only state-maintained prairie chicken observation site in the state. The two blinds are near a booming ground, and most dawns in late April and early May will find chickens there performing their mating rituals. Prairie chickens are among the most unique forms of wildlife of the prairie crop land country, and their springtime booming is one of the spectacular wildlife "shows".

"The morning after I hear that first boom, I try to slip up to the blinds be fore daylight. I don't have much company that time of day, especially

Photo by Jon Farrarduring the week. It's a little like watch ing the Roman gladiators —without the bloodshed. Each of those cocks seems as serious about defending his 10 to 20 yards of hill as a gladiator would have been about defending his life".

During the booming dance, the male's bright orange air sacs puff out the sides of his neck, and the long feathers stand up like horns. He charges forward, screeches to a halt, then stamps his feet rapidly, some times pivoting in a dance. Suddenly, his fanned tail snaps with a sharp click and the air sacs deflate with a cooing "boom" that can be heard for a mile.

Loggerhead shrikes use the prairie areas, too, and later on, when the grasshoppers hatch out, the shrikes find more meals than they can eat. Their answer to the storage problem is a locust thorn or a barbed-wire fence where they pin their excess booty for future reference.

Individuals and groups have helped the Game and Parks Commission to look out for the future of wildlife through prairie wildlife areas. When parts of Pawnee Prairie were offered for sale, the Commission hadn't the ready cash to purchase the land. Nature Conservancy then came into the picture, buying the land and holding it until funds were available from an agency that could manage it in the best interests of wildlife. Finally, the Game Commission was able to budget the necessary monies. Such in vestments hold valuable land, and the wildlife on it, in trust for the public. Native prairie areas like Pawnee Prairie are rare, priceless pieces of yesterday and today that will become even more valuable tomorrow.

Part of Alexandria was also a legacy to Nebraskans that came from a land owner who had planted trees and wildlife habitat on his farm. He encouraged wildlife to visit his home before he sold it to the Commission for further wildlife management.

Prairie is a rare, unique community, and the prairie areas are an attempt to preserve the kind of land and wild life that once spread across entire states. Miles and miles of rolling sod were an amphitheater for the clear song of the lark and the tragic-comic drama of never-ending life and death; the competitive struggle among plants and animals for survival.

"WHAT IS THERE TO DO?"

Family recreation is still a healthy, necessary activity. Public lands can help fill void for urban folks, but appreciating simple things is secret of outdoor enjoyment

Photo by Greg BeaumontI REMEMBER as a kid on the farm that we didn't think much about recreation—it just didn't seem to be a problem. I guess that the spring evenings when we all walked down to the pasture together to check the cattle, when we kids spent a few minutes sliding down a grass-slick slope on the backsides of our jeans, would qualify as recreation for some people even now. The folks would lie back in the shade of a deep-cut bank and listen to us squeal, and to the quail whistle calls that came through the lulls.

I remember dad casually comment ing on cow behavior...there was a heifer conscientiously babysitting with two of the mothers even though she hadn't had her calf yet; and what makes that Hereford stand and watch us while the others couldn't be less interested?

I remember the shimmering rustle of cottonwood leaves, and kicking up bunnies and pheasants along the brushy edge of a windbreak. I remember the solitary experience of morning; dew-touched sun soaking into lightly tanned skin and a multitude of black birds filling the morning with song and making bold to inspect the inert human form lying in their domain.

I suppose people would call it recreation now, and work themselves into a froth preparing, but when I was a kid I looked forward to a rain. When dad couldn't get into the field, and we needed a change of scene, we threw some old blankets in the trunk of our old car, along with some well-cured catfish bait (which invariably leaked). We dragged a ring of baloney and a loaf of bread out of the freezer, and we called it fishin', not recreation. Even that was probably a misnomer — we seldom caught anything except suntans. We swam (downstream from the fisherfolk) and romped and lay in the shade to daydream.

When we ran out of food, or the fields dried up, we went home.

It seems like, today, there are fewer people on the farm —or maybe there are just more and more people in the cities. At any rate, our society suffers withdrawal symptoms. The with drawal into an urban environment leaves people frustrated and unfulfilled and groping for an undefined something to make their lives fuller.

It seems somehow paradoxical to see people whipping themselves into exhaustion to relax. Never have people worked so hard to play. A weekend of fishing requires a tre mendous cash investment in equip ment and an incredible investment in time and concentration. It is actually important to catch fish so as not to waste the investment!

City people seek out recreation and wildlife areas for recreation. When they arrive, they pile out of the car and, without pausing to take a deep breath, ask, "What is there to do?"

No one ever seems to think that a good start might be to sit down in the grass (most outdoor areas are still provided with that facility) and listen for the variety of sounds made by natural substances and bodies rather than plastic devices.

Public park and recreation areas do what little can be done to fill the gaps where a few acres of family farm used to suffice. There are creek beds and trees and grass along with wild birds and animals to be enjoyed, yet we are so tense about relaxing that we seem to hurry by them without noticing. Our time and attention are too filled with preparation and getting there, and all the activities we have to squeeze in when we do get there.

It seems as though going outside just to be outside is a thing of the past. That seems a shame, for the simple pleasures are often the most enriching.

We all are, after all, something of the overgrown kid. Most of us would like to play on a raft and paddle our feet in the water. And, maybe take a fishing pole along and try to catch a crappie in a quiet bay. We might even catch our dinner tonight. If not, we can come back soon, together with our family, to enjoy more quiet, but exciting, outdoor fun.

FISHING... WHITE BASS TIME

WITHOUT WHITE BASS, August would be a resounding flop for a lot of Nebraska fishermen. The high temperatures and piercing sun drive most of the game fish in Nebraska's big, western reservoirs to the cool, dark depths, where they sulk in wait for more comfortable fall conditions.

But not the white bass. In fact, when the sun is high and hot, the white is at his fast and flashy best. At that time, most of the big-water fishermen forget all about other species and seek white bass almost exclusively. And, why shouldn't they? In August, the bass are easy to find, easy to catch, and roam to the surface in unbelievable numbers.

The key to this frantic activity is the white bass' favorite food, the gizzard shad. In the middle of summer, the year's crop of shad gathers in huge schools at or near the surface of the lakes. By that time, they have grown large enough to be considered bite-size by the hungry white bass.

The whites also gather in schools, and prowl the lake looking for shad. When they home in on their prey, they attack with reckless abandon. If a fisherman can be in range when the bass are working on a school of shad, he can often get a savage strike on nearly every cast.

The way most fishermen manage to be on hand at the right moment is the time-tested practice of "gull chasing". Flocks of gulls often mark schools of bass by gathering over the spot where the whites have driven a school of shad to the surface. The gulls like to eat shad too, and when they gather to collect their share, they tip fishermen off to the whereabouts of the bass.

Once a school of bass is located, getting them to hit is usually an easy matter. A flashy artificial is usually a good choice, and jigs also work well. Favorites include heavy chrome-plated spoons (the weight makes long casts possible) and shad-like plugs.

Though the principle of "gull chasing" is quite simple, there are a couple of fine points to be considered. For one thing, it just will not do for a boatload of anglers to go charging right up to the scene of the action at top speed. A noisy approach is the best way there is to spook that particular school of bass way out of the neighbor hood.

Rather, the fisherman should approach quietly, and cut his motor at a point where he will drift into range of the feeding fish. Ideally, he should plan the drift so that he passes alongside the school rather than over it. Chances are good that his boat will spook the fish if it passes directly overhead.

Not only does the wrong approach to a school cost an angler some fish, it might also cost him the friendship and good will of other fishermen in the area. There's no

Hesser likes to follow the white bass schools when the gulls will play bird dog for him, but he doesn't give up if that strategy doesn't work. Instead, he heads for parts of the lake offering certain conditions that have produced white bass for him in the past.

He keeps his eye on his electronic depth finder, looking for a ledge or dropoff in from 15 to 25 feet of water. When he finds a likely spot, or gets an indication of a school on the depth finder, he anchors and fishes awhile. Most of the time, he simply jigs a heavy lure like a Kastmaster, slab or jig.

Hesser says that it is possible to sit on top of a stationary

At other times, white bass might be over water as deep as 50 feet. However, the fish are not at the bottom, like some other game fish might be. Instead, they are usually "suspended", perhaps 15 to 20 feet below the surface.

Most often, Hesser fishes these schools by trolling, using Thin Fins or jigs behind trolling planes, which take the lure down to the desired depth. Sometimes he lo cates fish trolling in this manner, but at other times, he picks them up on his depth finder. In either case, he stows his trolling rig and casts once he has a school pin pointed.

Generally, Hesser finds that the bass schools be gin the day near shore, then work their way toward the middle of the lake as the day wears on. Late in the after noon, they seem to begin moseying back toward the bank.

Harlan County Reservoir is Hesser's pet lake, and is a traditional favorite among a good number of the state's white bass fishermen. And there is good reason for their preference, since that body of water produces large numbers of good-sized fish.

However, several other Nebraska reservoirs rate mention as proven or potential hotspots. Lake McConaughy has always hosted huge white bass schools, some of them composed of jumbos over two pounds in size. Big Mac's white bass took heavy losses a couple of years ago when a disease cut into their numbers, but they appear to be making a strong comeback.

At present, Swanson Reservoir near Trenton appears to be the champ of Nebraska lakes as far as big white bass are concerned. According to fisheries biologists, Swanson's whites average the largest of any reservoir in the state, although they are a bit less numerous there than elsewhere. Other good bets include some reser voirs along the Tri-County canal system, especially Lake Maloney and Johnson Lake.

If fisheries biologists had to pick a "sleeper" in Nebraska white bass fishing, it would be Lake Minatare near Scottsbluff. White bass were introduced into this lake only a few years ago, and they appear to have done quite well.

No matter where he is found, the white bass has to rank alongside the catfish as a summertime favorite. They can't be beaten in terms of action and excitement, and their golden brown filets rate top billing on any menu.

If there's anything that will make a searing Nebraska August bearable for an angler, it would have to be the white bass.

Prairie Life/ Aggression

Photos by Jon FarrarAGGRESSION CAN TAKE many forms on the prairie. It can be a dominant crow driving another from a favored perch, a male spotted lizard flashing its blue underbelly to another male, or a bull bison wallowing in a dust bowl. Occasionally, aggression occurs between individuals of different species, but most often, conflict grows out of competition, and this competition is keenest between individuals of the same species. Two crows must compete for the same food, nest sites and mates as well as the same perch.

Charles Darwin recognized that "competition should be the most severe between allied forms, which fill nearly the same place in the economy of nature". As the number of individuals in an animal population grows, so do the demands on food supplies and living space. Competition becomes keen.

Most fighting takes place in non-social species during the breeding season. Usually combat, or threat of combat, is between males. In a few species, though, like the Wilson phalarope, the male is the nest builder and incubator and the females battle for territory. Social animals have rigid "pecking orders" and an individual's rank is honored once established. Occasional combat or threat of combat determines social standings and accomplishes reorderingof the hierarchy.

Generally, reproductive fighting is over territories and not mates. The territory may be fixed, as a bluegill's spawning bed, or it may be mobile as when a whitetail buck defends the area around his harem of does. The function of territorial fighting is economical: it serves to distribute individuals evenly, ensuring them of some element essential to their survival or reproductive success —a mate, a feed ing territory or a nest site. It may secure a nearby food source so that parents do not need to forage long distances from their young.