NEBRASKAland

NEBRASKAland

VOL. 53 / NO. 5 / MAY 1975 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Fifty cents per copy. Subscription rates $5 for one year, $9 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. commission Chairman: Jack D. Obbink, Lincoln Southeast District (402) 488-3862 Vice Chairman: Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 2nd Vice Chairman: Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-Central District, (308) 745-1694 Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-central District, (308) 452-3800 H. B. "Tod" Kuntzelman, North Platte Southwest District, (308) 532-2982 Director: Willard R. Barbee Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, Jr. Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: Jon Farrar Greg Beaumont, Ken Bouc, Steve O'Hare Contributing Editors: Bob Grier Faye Musil, Tim Hergenrader, Roland Hoffmann Layout Design: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1975. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska Contents FEATURES FISHING...THE SMALL WATERS FISH AND BRAIN FOOD GOBBLER BAIT NEBRASKA'S VANISHING WETLANDS GET THE LEAD IN CANYON TROUBLE A PLAINS PEOPLE THE SUMMER OF '75 PRAIRIE LIFE/HUNTING INSECTS NATURAL RESOURCES ... A DISTRICT CONCEPT NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA/OPOSSUM 6 10 14 16 24 28 30 36 38 42 50 DEPARTMENTS SPEAK UP 4 TRADING POST 49 COVER: A quiet moment in the spring along the Republican River is enjoyed by John Dietz. Story on page 10. Photo by Lowell Johnson. OPPOSITE: One of the rarest of Nebraska's spring flowers, the showy orchis, can sometimes be found in rich, moist woodlands along the Missouri River bluffs. Photo by Jon Farrar.

Speak up

Hats Off-Hats OnSir / Good article, Winter Survival, by Gary Gabelhouse in the January issue of NEBRASKAland. Reminds me of the occasional times whenever I woke up at night feeling chilly (maybe a bedcover partly thrown off). I'd pull the covers up over my head, allowing only a small aperture for breathing. This helps a person warm up fast. I did not know the reason for this rapid warm-up until reading "Survival", wherein the author explains why: "Your head is the route that heat most readily is lost...if you're cold, put on a hat, thus stopping the flow of heat into the environment."

A cap would be much better. Indeed, a warm cap is far better for winter weather than a hat.

Your cardinal picture on the back cover — beautiful.

Agatha Walter Portland, Ore. Birds and BirdsSir / I've never written a letter to a magazine before, but I wanted to say a few things to the lady who complained about the "slaughter" of our game birds in your March issue. (Mrs. Foster)

I, too, think we have some beautiful non-game birds in the state, including robins. We have three bird feeders in our yard and buy seed to keep them filled during the winter. My whole family loves to watch the birds feed and identify the many different species.

But, I don't see where this has anything to do with the game birds and hunting. My husband and I both buy combina tion hunting and fishing licenses every year, including upland game bird and duck stamps, so I feel we are contributing something to the wildlife management in the state.

Most hunters are primarily sportsmen and obey the hunting laws set up by the Game Commission, a group of men who are familiar with the need to "harvest" the game bird crop to maintain nature's balance.

If this lady had ever seen birds trapped by the snow that have smothered or frozen, or birds that have been torn apart by coyotes or hit by a car, she would have to admit that the hunter who shoots a bird, takes it home and has it for dinner is by far the best "harvester".

I'll climb off my soapbox now, and say thanks for a great magazine. Also, thanks to the Game Commission for the terrific work they're doing and we hope that Nebraskans can soon enjoy a dove season.

Carol Ingald Ashton, Nebr. Wants to ListenSir / I didn't need any prompting to reply to Mrs. R. Foster's letter in March's issue. To all the Mrs. Fosters, I say:

Put your money where your mouth is. Even though you don't hunt, buy one or more hunting licenses, upland game stamps, duck stamps, give generously to all the fine organizations like Ducks Unlimited and the National Wildlife Federa tion, and give your time to helping wildlife in a direct way.

Then, and only then, will I listen to your opinions about wildlife.

Judy Sherwood Imperial, Nebr.Bravo, ditto, and why isn't everyone as aware as Judy? (Editor)

Workshop BoosterSir / I just finished the article "In Touch with the World" in the March NEBRASKAIand. The article dealt with the environmental workshop.

I would like to know more about the workshops and hope that in the future I can receive information as they are planned.

Here in the Upper Big Blue Natural Resources District, we are trying to develop an education program that would benefit students as well as teachers, and hope that we can get the teachers in volved more in environmental and conservation education. We're hoping we can set up a solid scholarshfp program to provide funds to send teachers to workshops of this type. We currently have a program that pays for 75 percent of the costs to send teachers to environmental workshops.

Any other suggestions you may offer us on environmental education would be greatly appreciated.

Dan Staehr, program director Upper Big Blue NRD, YorkA workshop tor interested persons, in cluding teachers, will be held again near Louisville on June 10 through 13 of this year. Details on this and other workshops, and registration forms, can be obtained by writing Dick Nelson, Education Section, Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebr. 68503.

Thanks, NebraskansSir / We have returned to our winter home after spending a marvelous summer in your beautiful state. We toured from the northwest's Wildcat Hills to the south east and Missouri River. We were impressed by its vast prairies, productive fields and varied industries. These are all assets of a wealthy state. But more than these, a far greater asset of any state, we noticed the warm hospitality and sincere friendliness of all the people we met.

We were especially impressed by the people of the small but busy sandhills town of Valentine. The merchants were extremely warm and receptive; the adults helpful and friendly; the children well mannered and happy. We camped in the beautiful and natural city park and found it well taken care of by a young couple who went out of their way to make our stay pleasant and enjoyable. Truly, Valentine is a city with a heart, as many of the townspeople shared the fruits, vegetables, jellies and many hours of delightful conversation with us. We are full of wonder ful memories of Nebraska that we shall share with people here in Arizona.

Peck and Clara Davis Mesa, ArizonaShucks, you'll have all those folks blushing and carrying on. Our weather may not be the best, but our people are. (Editor)

Sad But TrueFollowing is a poem sent to us by Lillian Wyles of Lakewood, Colorado which points up a disparity in life styles. It is entitled "Message From the City to the Country".

You offer us quiet the fruit of your labors. So what can we offer you? Wall-to-wall neighbors!NEBRASKAland Magazine invites all readers to submit their comments, sugges tions, and gripes to Speak Up. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters. — Editor.

FISHING... THE SMALL WATERS

FOR SOME, THE joy of fishing lies in excitement—in setting the hook to a topwater strike or wrestling a brawny lunker from a deep hideout. Other anglers thrive on the challenge of locating fish and figuring out the tactics that will make them hit.

Some fishermen seek the satisfaction that goes with a stringer of panfish and the prospect of a tasty fish fry. And, some just like the tranquility that comes on a quiet, solitary stretch of water far away from everyday pressures.

Whatever it is that he seeks, a fisherman has an excellent chance of finding it on Nebraska's small waters; its farm ponds and sandpits. And, May is among the best of times to sample the sport these waters offer.

Many of Nebraska's smaller waters are on private property, and permission of landowners is needed to fish them. Obviously, this kind of quality fishing opportunity is at a premium. Some landowners reserve the privilege of fishing for a few close associates. But, many will honor a fisherman's courteous request, and the angler will be welcomed back if he leaves the area litter free, observes any rules that the owner might make, and otherwise behaves himself.

Both farm ponds and sandpits are usually relatively small, and some of the same species of fish inhabit them. But, they have little else in common as far as the fish erman is concerned. The pond is a small reservoir built on fertile farm ground and fed by runoff from agricultural land. The pit is scooped out of the sandy bed of a river valley, and is most often fed by groundwater or by seepage from the river.

The factors of farm ponds that most often hinder their fish-producing potential are their extreme fertility and shallowness. Pits, on the other hand, suffer from extreme depths and infertile waters.

To some fishermen, the physical and biological characteristics of ponds and pits might seem a bit academic at first. However, a fisherman armed with a bit of this knowledge can quickly assess the quality of a body of water, pinpoint some probable hotspots, select a likely lure or bait, and even make an educated guess as to what species might be living there.

For example, a pond should be at least 10 feet deep and one-half acre in size to support game fish such as large-mouthed bass and enable them to survive over winter. A quick look at the dam and the terrain surround ing the lake, plus a few probing casts with a sinking lure, quickly tells the fisherman if a pond meets the requirements.

A bit more assaying will determine if the water is clear or turbid, and if there is excessive weed growth on the bottom or just a moderate amount of aquatic plants. Clear water and moderate weed growth are optimum conditions for largemouths, which locate their food primarily by sight. They can see well through the water, and their prey, usually bluegill, cannot always escape into heavy plant growth.

If the fisherman finds turbid water and knows that it hasn't rained heavily in several days, he can probably resign himself to the fact that there is little chance of the pond supporting a good bass population. Most likely, the water is being roiled by carp or bullheads. But he might do well to check it out again when he's in the mood for some catfishing, since this type of lake some times holds good numbers of cats. In fact, most sandpit and farm pond stockings include combinations of catfish, largemouth, and bluegills.

Early in the season, fish will tend to be in the shallows and at the upper end of the pond, where warmer water and sunlight help them fight chilly temperatures. In late May and much of June, bluegill and bass head for spawning beds, usually choosing sand or clay bottoms in three to six feet of water. Later, the fish head for deep water to ward off summer's heat, or for the shade of submerged logs or overhanging cover.

Taking all of these things into consideration, a fish erman can assess a pond, make an intelligent selection of bait or lure, and be fishing the most likely part of it within minutes of seeing it for the first time. There is basically a pattern that usually works.

A sandpit fisherman can do about the same thing, but he is looking for quite a different batch of clues than the pond fisherman.

Depth is a factor on pits, too, but it's usually a case of too much rather than too little. Many pits in Nebraska have steep banks that drop rapidly to 25 or even 35 feet of water. During warm summer months, sandpits will not support life much below 10 feet deep because of oxygen depletion, so most of the bottom never develops sustained fish or forage production. The only bottom in the lake of biological value is thus a narrow band around the shoreline.

Because of a new pit's low fertility (resting on sand rather than soil and fed by groundwater rather than run off), every bit of aquatic plant and animal production is vital. Some of the better pits contain shelves in less than 10 feet of water, or their sharp banks have eroded and fallen into the lake after a few years, giving a more

NEBRASKAland THE SMALL WATERS

THE SMALL WATERS

gradual slope in the deeper water. Both conditions in crease the bottom area that plants, fish and fish-food organisms need.

Generally, a glance at the pit tells its character. Steep banks usually mean a continued sharp drop below, down to its dark depths. The presence of pumping equipment or evidence of recent operation means that the lake is relatively new, and has had little time to build up fertility, cave in its banks, or develop much of a fish population. A pit that's obviously been out of gravel production for a time has much more potential.

Carp can be a real problem in sandpits, and are quite likely to be present because of their proximity to rivers. These fish destroy the already sparse plant life on the pit's bottom, making forage species such as the bluegill extremely vulnerable to predators like bass. The predators actually overharvest the bluegill and deplete their major food supply. Generally, water of a pit in fested with carp looks murky, and the bottom is devoid of vegetation.

Figuring which parts of a sandpit to fish should not be too difficult. Very little bottom is available for fish to use except along the shoreline. This is important in April when fish seek the warmth and sunshine of shallow water, in early May when crappie are looking for spawning areas in four to eight feet of water, and in late May and into June when bass and bluegill are building nests.

The shoreline is also the best bet after spawning. In pits, about the only cover available for big predators such as bass would be fallen trees, brush and debris that grows, falls or accumulates along the banks. Anything farther out in the lake would be too deep to be of much value to the fish.

All this should suggest some do's and don'ts as far as tactics and tackle selection are concerned. For in stance, flinging a heavily weighted chunk of bait far out from shore is not likely to be very productive. Neither, in most cases, will be most bottom-crawling offerings such as the heavily weighted "Texas rig" plastic worm, or the "jig and eel" when fished in a conventional manner.

However, plastic worms can still be effective in sandpits if used with little or no weight and kept fairly close to shoreline structure. Other sinking lures such as spoons and jigs, or the deep-diving plugs, also have their place in the sandpit, but the fisherman should stifle the temptation to fling them far and fish them deep.

Because of their peculiar nature, sandpits can be a source of frustration to a fisherman not used to their ways. But even more important, they can be a source of danger to the uninitiated or careless.

Because of the steep sides and unstable sand bottom, it should be apparent that wading would be hazardous in many pits. Even fishermen perched high and dry on shore should be on the lookout for crumbly or under cut banks that might drop them into the drink.

The area around the site of active pumping operations is especially hazardous. There's the obvious danger of being around big and unfamiliar machinery. But the main thing to consider is that the sand and gravel pumping operation can make banks in the area particularly unstable.

Also, the spoil areas of clean, fine waste sand found along shore near the hopper are dangerous and should be avoided. This sand often forms an almost vertical bank under the water's surface, and is very unstable. Large chunks of this inviting "beach" often break off or "dissolve" and slide into the water, and any fisherman caught out there would find himself swept to the bottom of the pit in an avalanche of sand, with little or no chance of escape.

Despite the few drawbacks that they might have, Nebraska's pits are an important resource for the state's anglers. Several of Nebraska's hook-and-line records have come from such waters, including the 10-pound, 11-ounce large-mouthed bass that has been on the books for some 10 years.

And, it's about the same story for farm ponds, which have a number of state records to their credit.

Consider, for a moment, the statistics on pond and pit fishing. About eight percent of Nebraska's fishing takes place on private ponds and pits, yet these waters accounted for nearly half of the Master Angler bucket mouths taken in the state the past two years.

Nebraska's small waters offer more than impressive stringers to those earning the privilege of fishing them. Even if the fish don't bite, an outdoorsman can still Collect his reward. He might share the water for a moment or two with a stately heron or a brood of brand new teal. He might spot a shy buck coming in for a drink, or witness the reawakening of the outdoor world some bright, spring dawn.

Whether the fish hit or not, an outing to one of these small waters is worth considerable effort. If nothing else, they offer a chance to escape the hordes of noisy boats and people on the larger lakes. Nebraska's small waters offer good sport nearly all year, and May is a perfect time to give them a try.

FISH AND BRAIN FOOD

Being smarter than the catfish helps, but the real secret to success is giving them exactly what they want

Photos by Lowell Johnson 10 NEBRASKAlandONE WOULD naturally be taken aback if, when ask ing a fisherman what was needed to catch catfish, his reply was "brains". And, that was my first impression of John Dietz, a Lincoln man who spends much of his spare time splashing and squishing in stream and along shore in search of catfish.

John, who has set type for NEBRASKAland Magazine for many years, occasionally flashes a photo ing him and some of his cronies with a long stringer of huge catfish. After he had done this several times, I was finally forced to ask him about details —the usual thing of where he got them, when, and about the size. But, it was when I asked him what he used or what his secret was that he responded with the "brains" bit. I assumed he meant it required a fisherman smarter than the fish, but then he went on to explain.

His secret, and it really has been pretty much that, is using beef brains for bait. The catfish, it seems, really go for them. I suppose that is because they are messy, because that is what most catfish baits seem to be. In fact, the rather mushy, loose texture of the brains makes them a difficult bait to use unless coupled with a special method of affixing them to a hook.

Anyway, after several exposures to John's photos, I talked him into a weekend outing to one of his favorite fishing spots. It didn't matter where, so he said he would scout around and pick a spot in a few weeks.

As it turned out, the Republican River in the Or leans area was the spot, and we headed for it so we couId be out on the water bright and early on a Friday morning in mid-May.

That particular Friday morning, like several before, was not bright, as it was heavily overcast and frequently damp as a light drizzle decided to fall all day instead of presenting a good rain for a while. Also fishing with us was John's son, Jim, who was only 14 but is a hulking 180 pounds. And, probably as avid a catfisherman as his dad.

After surveying the damp terrain for just a few minutes, we forced ourselves out into it and started putting tackle together. With only a few hundred yards to go to the river, it wasn't long before John demonstrated his unique method of affixing the mushy brains to a hook. He used a treble hook, then above it he attaches three small rubber bands by simply looping them around the line just above the hook eye. These can then be stretched one at a time, looping them over the gob of bait, form ing an elastic net.

For the first six or eight times, I asked John to again demonstrate, but he finally got wise and I had to do my own. The brains aren't unpleasant to handle, because they do not have any odor, at least when they are still half frozen, but I kept snapping the rubber bands onto them, which rather splatters goop around the area — especially onto the arms, face, and shirt.

Things really happened rather quickly, at least for John and Jim. They would wander up the bank, seeming to be quite casual, but always with an eye along the shoreline. Whenever some obstruction or overhang looked good to them, they would flip out their bait, adjust the line, then set the pole down, watching and waiting.

Usually only a few moments would pass before something would start playing with it. Now, trying to visualize the size of a catfish playing with a gob of brains in a fairly murky river, can become a challenging hobby. But, being able to read the river and know which spots were most apt to contain any catfish at all seemed a to tally baffling and frustrating proposition. Yet, John would walk by good-looking stretches of water in preference for some other spot he saw or expected up ahead. Thinking he was just being picky, I would angle in those stretches he ignored, and never did get a nibble.

Even Jim, who I figured couldn't have more than eight years of experience, would be carrying one more fish every time he walked by me. Within the first hour each of them had four fish, with the largest going maybe four pounds, and the smallest about one pound. The little one wouldn't have been kept but was injured during the scrap.

Almost constantly on the move, working each selected spot only for several minutes unless there was some action on the line, or unless convinced there should be a cat in there, it didn't take long for us to cover a couple miles of river. It seemed longer, what with the light mist falling most of that time, and with me not getting more than little brain robbers —no fish with healthy appetites. Apparently I was setting the hook too soon, or too late. Nothing worked, anyway.

I soon pretended that it was more exciting for me to merely watch the action, study the methods, and in spect the millions of wild grapes that clung to nearly every bush and tree within reach of the climbing vines. I hoped to return that fall to assay the grapes for possible use for jelly and such, as it certainly appeared to be a bumper crop.

There were other diversions for me to fall into, also, such as a network of wildlife tracks in the damp shore line along one open stretch. Almost on top of each other were tracks of some large bird, probably a blue heron, raccoon, deer, plus another small bird and what appeared to be mouse, although the mist had about erased the smaller marks. I spent quite a little time perusing the prints in the sandy mud, so John and Jim got quite a ways ahead, where they were fishing a sort of backwater formed behind a dike of land which had sloughed off the shore.

Although partially concealed behind a thick growth of willows, I could see them occasionally moving along the bank. After a few minutes I started to join them, and

MAY 1975 11 Whether wading or slipping along the bank, it is

selecting the fish hangouts that counts

Whether wading or slipping along the bank, it is

selecting the fish hangouts that counts

then saw John walk Into the water and head for the other bank. He apparently saw greener water over on the far bank, so decided to walk over. I assumed that deep holes would make such maneuvers risky, but he merely probed suspicious areas with his fly rod before walking into them, and soon was indeed fishing new holes.

As we were already fairly damp, Jim and I talked things over and we decided to cross over too. Most of the water was shallow, and we never got our knees wet by following the areas where the current had filled in with sand. About a half hour had passed without any fish being taken, then John caught two small ones quick ly. Jim settled down on the bank under the minimal protection of a low-growing tree. Naturally, I sat down near by to watch the proceedings, and action wasn't long in coming. He had more or less dropped his bait right next to the bank, probably no more than four feet away, and probably in no more than three feet of water under a fallen tree.

In less than a minute, a fish had gobbled up the mess of brains and was sneaking away with it. Jim expertly set the hook, even under the low branches, and in just a few moments was hauling in a nice catfish, at least 3V2 pounds. I cast a wishful eye at my gear, which I had leaned against a tree, but there was not even room for one angler in that tangle of branches and brush. Any way, several more minutes produced no more fish for Jim either, so we again picked up and moved upriver. It was getting on toward noon, and as fish activity had slowed noticeably, John suggested a quick lunch and a move to another stretch of river.

First, though, came the cleaning of the 11 fish taken during the morning, and depositing them in the cooler where the many cartons of frozen brains would keep them cool. The weather was clearing somewhat, which may have brought the slowdown in fishing, but it was after we moved back to the river that we learned how unusual our success had been. From an access road, we had walked about a quarter of a mile to a bend in the river where a number of car bodies had been implanted, either for beautification or for erosion control, when another fisherman came by. He was checking his set lines, and we learned that fish hadn't been hitting for more than a week.

Fluctuating water levels that spring had brought in a number of fish, as shown by his success, then every thing dropped to about zero and had stayed there for over a week. When John's rod took a nosedive and he finally retrieved a 5-pound cat from among the car bodies and a fence, the old fisherman must have won dered about his bait, for he promptly asked what John was using. I watched closely for a change in expression when John answered "brains", but he actually said "beef brains", which is considerably modified.

When we were again alone, I had to tell John about a friend of mine who once told a story about catfishing only a few miles from where we were. He told about a fish taking the bait and easily breaking the 8-pound line he was using. So, he put on some 20-pound braid and tossed it into the same hole, only to have the fish also snap that line. Remembering some nylon rope in his car, he quickly fashioned a fishing rig of it, lashed on a big gob of bait and again dropped it into the hole.

Sure enough, the fish grabbed it up and soon tight ened the rope, but couldn't break it. Unable to pull the fish in, my friend said he took off his watch and jumped into the river, following the rope downward. Before he could get to the fish, that tough old cat swam into one of the car bodies, barely squeezing his bulk through the window. Having the fish cornered, my friend said he reached in to grab him. but that nasty catfish rolled the window up on his arm.

John laughed politely, then strolled upriver. I played around among the cars for a while, waiting for Jim to work his way along, then we waited and inspected John's fish when he returned. Again, a move to another stretch was suggested, and again we watched as John cleaned the new addition for the cooler.

Although the next stretch looked good from a distance, the water was much too shallow to suit John's critical eye, so we headed several miles upriver to one of John's favorite spots. There, the river more than doubled back upon itself within a short distance, providing two big bends that looked mighty fishy. Here, though, amid what looked to be the best water, we went fishless for the first time. The nearest stretch, which looked extremely good, produced nothing. Jim did have a little trouble getting into the water, as his reel acted up and resulted in considerable splashing and mumbling. The line was replaced, but that piece of water was subsequently ignored.

Elsewhere up and down the bank, the lower water level had apparently lessened the habitat to such a degree that no fish could or would hang out there. By that time, I was as convinced as John that if brains wouldn't drag in the cats, nothing would, so there must not have been any around.

With the sun settling down for the night, we made plans for an early breakfast the next morning to get in a good half day's fishing before returning to Lincoln. The next morning the weather was as good as it had been bad the day before, although we were out even before the sun showed up. The first fishing was done above the bridge just south of Orleans, again along old car bodies, but although we had several nibbles, only one fish was landed by John —I lost several more gobs of brains for my efforts.

The next spot was several miles upriver, with a half mile walk to the river proving to be a pleasant diversion from staring at a slack line. And, the fish were more receptive, although not hysterically so. I had converted to an ultra-light, with silver spoon and various other lures, trying for white bass, but never got a tap. But, a few small catfish must have liked the brain food, and John let me play with one of them. About three of them thus came to hand, which was only about one per hour. After covering several hundred yards of shoreline, we agreed that we should give the fish a break, and the weekend outing thus came to a quiet close.

Since then, even toward the end of the year, John was out dragging in the catfish. Stretches of the Blue River and a couple other places are much closer than the Republican and offer some good catfishing, and John always has the brains available to outsmart a good number of them. While watching him work that week

Just as bass fishermen, who study fish habits and preferences during every part of the year, have learned what will work best, so have catfishermen. After much comparison, John decided that brains were the best bait, and he apparently has developed the best technique for fishing them. And, the experimenting has paid off with some of the most dependable and enjoyable fishing around —all it takes is brains. But as I learned, there must be a brain on both ends of the fishing line. I never did catch one of those stupid catfish.

Gobbler Bait

IN 1959, THE Nebraska Game and Parks Commission released into the western Pine Ridge area of the state, 28 wild Merriam turkeys. The Pine Ridge, a beautiful area of rough, pine-covered hills and high-rising buttes, provided this flock of imports with all the essentials needed to sustain life, and a successful game bird stock ing program was underway.

The population increase was unbelievable, and was commonly referred to as an explosion. The birds spread throughout the entire northern panhandle area, and inside of five years had virtually saturated the available habitat.

Trap and transplant operations began with these birds, and Merriam turkeys were introduced into other desirable or suitable areas throughout the state. Not all releases enjoyed the success of the original, but some of the transplants did develop into populations that now provide many enjoyable hours of hunting for the sportsmen of Nebraska.

Now for any of you who are anti-hunt or semi anti-hunt, don't let that word "hunting" scare you out. This isn't going to be one of those high-powered, super duper, successful hunter articles. Au contraire!

Allow me this viewpoint and we can continue. The hunters in our state have provided the funds (through licenses and taxes from sporting goods purchases) to pay for the turkey stocking program. The turkeys have now reached the point where each year they reproduce in excess of what their habitat will support. Our turkey seasons, then, merely allow hunters to harvest this excess production.

Livestock producers exist by carrying out this same annual process. They maintain all the breeding stock their land or facilities can support. Yearly reproduction creates a surplus of animals and that surplus is sold. Profits, if there are any this day and age, are then put back into the maintenance of the operation, just as license fees are directed to supporting, protecting and assuring the future of the wild turkey.

Now to continue. I'll grant you, as hunters go, there are some bad and some good; but you can believe me when I tell you that the man who chose to accompany me on last spring's torn turkey hunt in the Pine Ridge area, is a good hunter.

Charles Mahler and I have enjoyed each other's company on many hunting endeavors —one being a successful torn turkey hunt in eastern Nebraska back in the 1960s.

Sharing similar philosophies, we agreed that Aldo Leopold was right when he stated that as the means of hunting became more sophisticated, the quality declined. Both of us wanted to keep quality in the hunt, so we decided to use muzzle-loading guns, knowing full well that we would have to be extremely close to make a clean kill on one of those gigantic birds. Our faith in attaining such a shot was placed in two items one, a hand-made, cedar box turkey call; and the other a most alluring, well built and perhaps the sexiest looking hen turkey decoy you ever laid eyes on. We created this turkey teaser from a goose decoy, repainted of course. The only other innovations were detachable legs and head, which made transportation somewhat easier.

Tom turkeys respond best to a call in the early morning hours. Their gobbling and displaying begins immediately after they descend from the roost tree. Knowing this, Chuck and I were up a good two hours before sunrise. We conjured up some bacon and eggs, devoured them, secured the camp, and lit out for the hunting territory.

The morning was perfect —one of those picturesque Pine Ridge sunrises. The air, at a dead calm, allowed us to hear extremely well, which is important in locating gobblers.

The sun's rays shooting over the horizon cast an orange hue on the dew-laden grass, and a thin haze was still visible in low-lying areas.

It was a naturally beautiful scene from where we stood, marred only by the fact that I could see Charlie, and of course he could see me, and neither of us fit the picture.

Both of us carried black-powder guns and two horns, one for shot and one for powder, and a shoulder slung leather pouch full of muzzle-loading necessities. In addition to all this, Charlie had draped over his shoulder a duffle bag full of our turkey decoy.

As we descended a ridge into a heavily timbered area, Charles made an interesting observation. He concluded that we couldn't have heard a turkey gobbling if he were standing on one of our heads and using a megaphone, due to the clattering of all our hunting equip ment. I will have to concede, we did sound like a pair of nomadic junk dealers peddling our wares in a hard sell territory.

After a very uneventful first hour of setting up the decoy twice and calling, we decided to move to a different hunting region. We had just sacked up the decoy and turned to leave when, from less than 300 yards away came a thunderous gobble. Quickly we dropped to our bellies, crawled into the edge of the timber, and began jamming the extremities back into the decoy. We then placed it in an opening approximately 10 yards away and concealed ourselves behind a low embank ment at timber's edge. We primed our shotguns and I began to call to that (Continued on page 44)

Wanting to keep quality in the hunt, my partner and I did everything possible to be sportsmen. Our only advantage was experience, and a sexy decoy

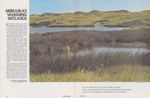

NEBRASKA'S VANISHING WETLANDS

FOR MANY YEARS now, I've been fascinated by the marvelous variety of wildlife that enlivens the wetlands or marshlands of the Midwest. When I was a boy, wetlands were an after school and Saturday attraction for me and several friends. Often during the year, we'd take a short walk to a near by wetland to explore an environment that teemed with living things.

In the spring, we'd watch small flocks of mallards and wood ducks soaring overhead as drakes courted hens; and if we were lucky, we might witness the arrival of Canada geese peeling out of the sky and sideslip ping back and forth as they prepared to splash down in marsh waters.

We soon learned that marshlands held far more than ducks, geese, and other easily seen wildlife. Less conspicuous creatures such as sora rails and nesting grebes often revealed their presence with calls, cackling noises and other intriguing sounds. And the smells that a marsh generated! Varied, pungent... unlike any I'd experienced before.

It is not difficult to understand why marshlands attracted us so, for in and around a marsh we could explore and often experience the unexpected — catching a glimpse, perhaps, of a weasel methodically tracking an invisible mouse, or observing an aroused bit tern on her nest. Wild lands such as marshes were unique, exciting, a welcome change from the manicured bluegrass, asphalt and concrete en

vironment we were all too familiar with.

Nebraskans are fortunate in that their state contains numerous wetlands from the Sand Hills to the rain water basin area in south-central Nebraska. According to an inventory conducted by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, the rainwater basin area originally contained about 3,900 natural wetlands of varying depths and sizes. Water accumulates in these basins during periods of runoff associated with snowmelt or rain fall. Their wetness or lack of it depends on the weather, and it is not unusual for even the deeper basins to be dry throughout most of several growing seasons until a change in the weather causes them to be recharged with water from snowmelt or rainfall.

Nebraska's Sand Hills region constitutes the largest continuous area of sandy soils and dune sand in the plains states. The hills occupy about one-fourth of the total state area, or nearly 20,000 square miles. Although sandy "blowouts" occur locally, the region's sandy soils are generally stabilized by growths of prairie plants. Set within portions of this region of rolling, grassy hills are more than 13,000 wetlands ranging from seasonally flooded meadows to shallow lakes.

Geographically, Nebraska wetlands

are the southern cousins of a large family of wetlands that extends north through parts of the Dakotas, Iowa, Minnesota, and the Canadian prairie provinces. These wetlands not only furnish waterfowl, mink, deer, pheasants and numerous other wildlife with outstanding habitat, but they also help meet the needs of people — of youngsters, adults, farmers, ranch ers and city people.

Some folks enter marshlands each fall attempting to decoy wary green heads within shotgun range. Other people enjoy the scenic beauty of a wetland: a wedge of snow geese against a clear blue sky or a great blue heron silently stalking a frog. Many hunters also appreciate these marsh land experiences and regard them as one of the qualities that makes duck hunting such a superb pastime. By furnishing opportunities for people intent on hunting, trapping, photographing and watching wildlife, wetlands help meet human needs for recreation, mental relaxation, and solitude.

But wetlands have other important values less widely recognized and often overlooked. These include the contributions wetlands make in recharging underground waters and in reducing flood damage. Underground reservoirs may be recharged by waters slowly percolating downward from wetlands. And, by trapping and storing runoff from snowmelts and rains, wetland basins soak up runoff to help blunt the force of floods in nearby creeks and rivers.

Wetlands, widely spaced in pastures, help cause livestock to disperse instead of concentrating their grazing near one or two watering holes. Availability of forage is thus increased, enabling ranchers to produce more beef per acre of pasture. Prairie grasses growing in the moist soils bordering wetlands are an important source of forage for livestock, especially in dry years when upland pastures produce little grass. Coarse hay cut from the interior of wetlands during dry periods has also been used as bedding for livestock.

Finally, in recent years, wetlands and surrounding uplands are attract ing increasing numbers of students who have come to experience first hand what they've studied in school. A group of wetlands between the Platte and Loup rivers holds much promise as an environmental study area for young people. Located east and west of Highway 39, south of Genoa, these marshlands and surround ing grass and dunelands support an amazing variety of wildlife. Of keen interest to hunters, farmers and ranchers, portions of these lands and waters are also well located for use as an environmental study area. The preservation of these wetlands will help assure a place for future generations of students, birdwatchers and hunters to enjoy wildlife in a superb prairie environment.

In pioneer times, the hundreds of thousands of wetlands which settlers found on Midwest prairies must have seemed inexhaustible. However, during the past 100 years, thousands of wetlands have been obliterated, usual ly by drainage or land filling operations. Today, in many parts of Iowa and western Minnesota, wetlands are but a memory, as cropland, shopping centers and homes occupy sites that only a few years ago were homes for mallards, minks and muskrats. Within Nebraska, vast numbers of lagoons or wetlands in the rainwater basin area have been drained or filled in, leaving for the most part only the deeper, more permanent wetlands.

For example, of the inventoried, original 3,907 wetlands located in the rainwater basin area, only 18 percent exist today, and most of these have been reduced in size and quality. These losses have occurred as a result of drainage and land filling operations. Although some of the losses have taken place during the construction of highways and housing developments, most have resulted from at tempts to convert wetlands into fields that will be better suited for the production of farm crops. In the Sand Hills, wetlands considered only a few years ago to be relatively immune to drainage or filling, are now being filled in to make way for self-propelled irrigation equipment.

Now obviously, we need to produce vast quantities of food and fiber on farms and ranches. However, as vital as the production of foodstuffs is, it is also important to preserve semi natural areas such as marshlands, native grasslands and meandering stream channels.

These areas add diversity, scenic beauty and character to the landscape. In combination with the development of cities and farms, the preservation of natural areas creates an environment in which people can enjoy the best of both worlds. Cities, industry, highways, farms and other develop ments help meet the basic needs and comforts of modern society. Natural areas, the undeveloped world, help man realize his needs for recreation, appreciation of natural beauty, solitude and mental rejuvenation. Thus, the presence of natural areas such as wetlands enables people to lead richer, more interesting lives.

In the months ahead, as plans for public projects involving water development are formulated, full consideration should be given to the preservation of prairie wetlands. Their presence represents the remnants of one of the few original features of our natural heritage in the plains. Their preservation will help perpetuate our wildlife heritage and produce benefits related to education, esthetics, water conservation, and production of livestock forage.

Double the excitement of catching fish by catching a big one on a lure of your own making. This how-to article outlines all the steps, from casting and painting the heads to tying the body and tail

Get the Lead In

IF YOU WANT a lure that is cheap, casts well and catches lots of fish, try homemade, lead-headed jigs. Easy to make, jigs imitate minnows, the primary natural food of most adult game fish. Walleyes, northerns, white and black bass and crappies are suckers for a properly fished jig when they're on a feeding spree. Trout also take jigs, and even catfish and bullheads have been known to hit a bottom-bumping jig.

Fast sinking, they are designed to ride "hook up" while being bounced along the bottom. This provides some protection from snags, but most of these fish prefer a rocky or tree-lined bottom that can still take a heavy toll of lures.

Commercial versions of the jig come in a variety of colors, sizes and shapes. Freshwater jigs normally range from 1/16-ounce to over 1 ounce and cost from 20 cents each for crappie jigs up to 75 cents for bass jigs. If you use them a lot and fish them properly, you can expect to lose quite a few each year. Homemade jigs can be produced at a fraction of the cost of the commercial variety and you can tie the size and color to suit yourself.

Different game fish often show preferences for different sizes and colors of jigs. The walleye, for example, often prefers a 1/4 to 1/2-ounce jig with white head and tail. White bass, on the other hand, seem to like 1 /8 to 1 /4-ounce yellow

24 25

jigs with white or red heads. Crappie often take 1/16 to 1/8-ounce jigs in all-white, yellow or even green with a red head. None of these are hard and fast rules, however, and it's any body's guess what a fish will take at any given time.

Perhaps the most frustrating thing a fisherman can experience is to be fishing next to a person who has caught a whole stringer of fish while he goes fishless. Often the only difference is the color or size of a lure, and what seems insignificant to the fisherman may be of major importance from a fish-eye view. The best thing then is to have a variety of sizes and colors so you won't be caught with the wrong one.

If a person doesn't want to carry around a tackle box loaded up with a lot of jigs he may never use, maybe the best way is to carry a few painted jig heads in different sizes. A small pair of locking pliers gives you a makeshift vise, a spool of nylon thread, a few feathers and a small bottle of cement provide the tail, and in a few minutes you have a custom-tied lure to match the one that's catching fish.

For lead-heads, you can cast your own using scrap lead and a mold, or you can buy the hooks with the lead heads already molded on.

If you plan on molding your own, the first things you need are some special jig hooks, some scrap lead (avail able at junkyards), a pot to melt the lead in, a dipper or ladle to pour it with, a jig mold, an old file and a pair of gloves.

A cast iron pot and dipper work the best for melting since they hold the heat better. A gas or electric stove can provide the heat source for melting if the lady of the house can be convinced that you won't burn holes in her countertop. A piece of plywood or thick cardboard provides a flat, protective covering.

Heat the lead until it flows freely, then warm the mold before pouring. It's a good idea to also warm the dip per since you don't want the lead to cool too rapidly.

To mold, place the hooks in the mold, making sure they are the right size. Then close the mold and pour the molten lead with the ladle until the holes fill up. Wait a few minutes for the lead to harden and then open the mold. Use pliers to remove the cast heads and you're ready to pour again.

If the mold isn't warm enough, the lead may not fill the cavities completely. This may be the case with the first ones, but the second batch should be better and more uniform. Any heads that are less than perfect can be dipped back in the pot until they melt, and the hook can be reused.

The heads will need to be trimmed of excess lead. A small file works well for this. A pair of pliers or side cutters will be helpful to break off large pieces.

After the heads cool, paint them with a primer coat to prevent oxidation. They can either be dipped or painted with a small hobby brush. One coat of paint may be sufficient, but two coats last longer.

The little jars of enamel or lacquer for model cars work well for jigs, and if you can get away with it, try baking them in the oven at 175-200° for about 20 minutes. This gives a harder, more durable finish.

Now you are ready to add the body and/or tail. A fly-tying vise like the one shown is handy while the body and tail are tied on. A C-clamp or locking pliers will aiso work if you don't have a vise.

Other materials needed are yarn or chenille for bodies, some rod-winding thread size A or B, maribou feathers and bucktail or other animal hair. These can be purchased from local sporting goods stores or ordered from mail-order houses. Several companies advertise inexpensive kits that provide enough material to tie quite a few lures.

To tie a hair body, place the bend of the hook in the vise. Make a few wraps of the thread around the hook near the base of the head, wrapping back over the loose end of the thread. Cutoff the loose end and apply a small bit of glue to hold the wrapping in place. To tie a hair-bodied jig, take a clump of hair or bucktail, trim the butt end to the right length, hold it over the hook shank and wrap the thread over the butt several turns. Make a couple of half-hitches around the wrapping, pulling tight with each hitch. Trim the butt end and apply cement to the wrapping.

Maribou-feathered jigs are tied the same way. A variation using chenille for a body is tied slightly differently. To tie this type, first make a few turns around the shank of the hook midway between the head and the bend of the hook. Apply a dab of cement to the windings and attach the feathers or fur with a few more wraps. Make a half-hitch and attach a piece of chenille to the winding. Then wrap the thread back along the body toward the head.

Now wrap the chenille back toward the head in a single layer and tie off with several half-hitches. Trim the ends, apply cement and the chenille body jig is completed.

For protection against toothed fish such as walleyes, wrap some fine wire across the chenille in the opposite direction.

Other ways to use jig heads are as heads for plastic worms or for spinner baits using an off-set spinner blade.

The variations of this lure are many; limited only by the maker's imagina tion and creativity. Tie a few yourself and you'll find the excitement dou bles when you catch a nice fish on a lure that you have created.

Canyon Trouble

Things were tough, off and on, but when we got home, we would miss seeing the bats—and ticks

IT WAS HOT. In fact, it was so hot, I saw a coyote chasing a rabbit and they were both walking. And here were the four of us leaving the car for a backpacking and trout fishing trip. Included was my wife, who has some what gimpy knees; a friend who had quit smoking just the day before and who wasn't fit to be near; and his wife, bless her, who had never backpacked before. Also along was my dog, whose name I can't mention because of the bigoted overtones, and me, who by every definition of insanity I come up with, I fit into.

We walked about a mile to get to the canyon, and down we went, which took about 40 minutes of reverse climbing to descend the canyon to the river. We rearranged our gear and packed about a half-mile of the planned 15-mile trip, then took another break, where 28 My large but faithful dog and I avoid Tim whenever possible we encountered the first of our many troubles. Ned, the wife of the ex-smoker, was flushed in the face and in dire need of a rest, a drink, salt tablets, and a large dose of shade. We all took a dip in the river and retired to the shade of a tree. For dinner, freeze dried food was on the menu —it's light, you know, and easy to carry except internally.

While eating dinner, the second crisis arose —we discovered we were lying in a veritable bed of ticks. Everyone immediately began to scratch abundantly, and the conversation soon shifted to Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, which I never heard of anyone getting anyway. As it turned out, the bed of ticks extended over the entire canyon floor, so it was something to get used to. I never thought I could get used to ticks, and NEBRASKAland

The man with the nicotine fits after a half-day of minor troubles, had by then found an outlet for his frustrations — my dog. He seemed to have developed a hatred for my big pet. Now the poor dog was just trying to get along. All he had done thus far was mess up some dinner, knock Tim off the bank, and swim through a trout hole he was fishing. Did you ever notice how you can overlook faults in your own dog?

Oh yes, my wife, the gimper, is down soaking her knees in the cool river. I hope she makes it, but it doesn't look good at this stage.

It cooled off late in the afternoon (to about 90°) and we decided to pack for 2 or 3 miles before setting up camp for the night. The canyon walls were steep, MAY 1975 and we soon realized that the easiest walking was in the stream. I should say most of us learned, for Tim, who was nicotine crazed by that time, had climbed up and was walking the canyon edges, and having a mighty hard time. He never would admitthat it was easier where we were, below. He's a might bull-headed I guess.

We made camp along the river near some nice pools and decided to try our hands at fishing. Well, Tim and I beat the water to a froth with spinners and never caught a trout.

"Let's eat freeze-dried food for supper", I said. We didn't have much choice, so we did —beef stroganoff and then rather promptly went to bed. The "gimper" and I bunked outside, roughing it without a tent. The bugs darn near ate me; Thoreau never mentioned those bugs. On succeeding nights, you can be sure we used our tent. Tim and Ned used theirs even the first night, and really didn't display near enough sympathy for us, I thought.

We were up at the crack of dawn (dawn cracked about 9:00 a.m. that morning). I nursed and scratched my insect bites and we all sat around like a bunch of baboons, picking those miserable ticks off each other. We burned the ticks, whereas baboons eat them —that's evolution, you know. We had our break from the night's fast, tidied up, packed up, and moved on slowly. The fish were biting that morning, and Tim and I cleaned up. We had to use my ultralight, since the line of Tim's regular spinning reel was scaring the spooky low-water trout. Forgive me for admitting in print that I was spin fishing for trout, because I'm a fly fisherman. Anyway, a few wary trout caught on an ultralight eased Tim's nicotine withdrawal, but when fishing slowed he demanded, from the canyon edge, that we push on. We released all the trout, since if we carried them all day they would probably fall apart before cooking.

You remember Ned...well, she and the "gimper" were bringing up the rear. Ned was really enjoying the whole trip; being away from plumbing and running water and the like for the first time is always an experience. You could always tell she was having a good time when she picked a tick off her neck.

We pushed on that day and the next. We saw a lot of nice country, and here and there we laughed at the dog and ourselves. We caught some nice trout and released all but a few that we ate late one evening.

As always, we reached the end of our backpack with mixed emotions —we were relieved that the heat and ticks were behind us; but we were glad to get some real food instead of the "funny" chow we had been eat ing. And, we knew that when we got back to the city full of people, we would miss seeing the bats taking insects in the evening, and the owl hooting at night, the coyote howling, the babbling stream, and....

Epilogue:

My wife and I picked 155 ticks out of the dog's hide the day after we returned home. And, I remembered that Mark Twain once said: "Anyone can quit smoking — I've done it over a thousand times." Tim also prescribes to that philosophy.

A PLAINS PEOPLE

They belong to the wide spaces of the Great Plains, these faces of Nebraska's small towns. To Phil Winston they mirror the hardships and opportunities of this land

Photos by Phil WinstonSMALL TOWNS dot the Great Plains like patches of pasqueflowers in the spring. From the air they look like countless collections of worthless materials —cinderblock, stucco, clapboard and asphalt—gathered up and then discarded on an immense and level stretch of land.

But when you drive through these small towns of Nebraska, you get a different feeling. They seem products of the earth itself, as if they, too, had sprung from the soil like the fields of living things which surround them. If you come from a big city, you are struck by the brief streets and accessible yards. But you notice less their structures and more their people.

You can see the land in their faces. By their words and spare speech, you know they belong to the long spaces of the plains. When your hands have conformed to the trades of the earth and your eyes are capable of reading its cycles and seasons, you need little more than rain enough and sun to build your life.

You need each other, of course. (And a dog when you're young to help in measuring the immensity of spring). More than anything else, small towns teach the need for other people; a vital perspective easily lost in the crossfire of a city's demands.

With his camera, Phil Winston has captured the many faces of life in Nebraska's small towns. People are his subjects: young, old and in-between. Looking at his photographs which are always deceptively candid, seemingly snapshots you recognize at once the durability of a plains people. Whatever his camera chooses to regard, from a glimpse at a farm auction on a hot afternoon to an old woman, facing alone the formidable shadows of a future landscape, the message remains simple: when you live close to the earth you know enough of storms and promise.

30 NEBRASKAland MAY 1975 31

Decisions on public areas must be made wisely, and soon, if outdoor heritage is to survive

The Summer of 1975

EVEN THOUGH the energy crisis still looms high over our heads, every indication brings the professional park manager to anticipate record-breaking attendance at many areas of the Nebraska State Park System during 1975. Although many people may be forced to make cutbacks in vacation travel and recreation expenditures due to inflation, it is anticipated that people will, in many respects, vacation closer to home this year. State park areas offer family type outdoor recreation and vacations at reasonable cost, and these sites are scattered across the state making them generally accessible.

Increased visitor demands upon areas of the State Park System, coupled with the impact of inflationary costs in meeting operating requirements during 1974, have caused the Game and Parks Commission to seek additional revenue from the Legislature in order to carry out state park operations for the remainder of the fiscal year ending June 30. Additional budget authority in the amount of $160,000 has been granted the Commission to meet supply, operating and travel requirements. Without the additional grant the Commission would have had to close the park areas until new funds were derived from 1975-76 appropriations July 1. The additional grant will not solve all park operating problems, since it will be necessary for the Commission to cut back services throughout the State Park System in order to live within the budget requirements. These cutbacks will mean less overall service to visitors in the form of 36 NEBRASKAland general area upkeep —mowing, cleaning, servicing and repair. It is also very likely that reduced services in the form of shorter use season for fee-type facilities, including overnight cabins, campgrounds, swimming pools, trail rides, etc. State historical park areas and the major Interstate 80 wayside sites will likely be operated on a shorter visitation season. It may even be necessary to close some areas.

Since the 1959 Legislature provided the first appreciable funding for the State Park System by designating a .13 mill levy for state park development and operation, about 50 park areas have been developed, acquired or significantly improved for the public. Today areas exist in the system that will equal any other facilities of the same nature found throughout the country. As lawmakers have seen fit to allow state park develop ment, and new facilities have been constructed, so has this nation's economy undergone almost constant change resulting in eVer-increasing costs to maintain and operate park areas and improvements. Although the Commission has received increases in its park operating fund, these increases have not kept pace with the scope of development, rising economy and most significantly, the tremendous increase in today's visitor demand. The Game and Parks Commission cannot hope to continue meeting future state park operating demands without the granting of sufficient funds to meet these requirements. During the early 1960s the State Park System realized some 3 million plus visitors annually. Last year it is estimated that over 6.3 million persons visited areas of the system. We are currently experiencing visitation at major park areas during weekends and holidays equal to the population of small towns —it is not uncommon to have 7,000 to 8,000 visitors in one area at these times. High demands are placed upon state park areas and facilities. There are ever-increasing needs for more law enforcement and visitor control. We are experiencing increased conflicts at high use areas with multiple use by fishermen, boaters, water skiers, swimmers and others. The agency is receiving ever-increasing demands for services to special-interest groups such as snowmobilers, motorcyclists, horseback riders, pack and other types of campers, etc.

The input of outdoor recreation and the role of public service provided by the State Park System is gaining momentum. The aforementioned trends indicate that the demand for parks and outdoor recreation continue to boom at an ever-increasing rate. But, the financial capability for Nebraska's state park operations is diminishing in this era of growth, demand and national inflation. Because of this, the time has arrived for citizens to analyze seriously what it is they want from life and what they want for their children and grandchildren. Is the great Nebraska outdoors we've enjoyed so much in the past really worth building on for the future? If the answer is "no", then our outdoor heritage is doomed, and the simple pleasures of natural beauty and adventure will likely only be storybook tales. On the other hand, if the answer is "yes", then we had best act wisely, and soon.

The future of state parks is, in many respects, what state park administrators, planners, or state legislators want to make of it. The challenges of the future are great in Nebraska; and challenges always present opportunities. We cannot hope now to see all the options that will develop over the next decade, and there are the problems of equal dimensions —money, the increasing number of visitors, enhancing the visitor experience, coping with the destructive attitudes of some users, and others.

But, there is no reason why the state park movement cannot cope with these problems. State parks are vital for Nebraska's future —to the degree that the public desires to make them so.

Visitors this year will find new hard-surfaced access roads at the following areas of the State Park System: Ash Hollow, Arbor Lodge and Fort Atkinson state his torical parks; Indian Cave State Park; Box Butte, Long Pine, Medicine Creek and Merritt Reservoir state recreation areas.

Road paving at these areas was accomplished during 1974 under the State Recreational Road Program in cooperation with the State Department of Roads.

Visitors may find some park areas undergoing construction and renovation this summer. Please observe signs and plan your outing with sufficient time to allow for heavy use during peak visitation days, especially on weekends and holidays.

We ask that you familiarize yourself with the park rules and regulations. And, we hope you have a safe and pleasant experience during your visit to state park areas this year.

Capital improvements under 1974-75 budget authority involves the following listed State Park program activities: Indian Cave State Park—Cave renovation, additional pit latrines and area development planning. Fort Robinson State Park—Building repair and renovation. Sanitary improvement planning study. Chadron State Park —Cabin exterior renovation, reforestation and construction of new maintenance building. Ponca State Park—New vault toilets for picnic areas, swimming pool renovation and construction of new maintenance building. Arbor Lodge State Historical Park—Installation of heating and air conditioning system in mansion. Fort Kearny State Historical Park —Reconstruction of Fort powder magazine. Buffalo Bill State Historical Park —Installation of new irrigation well for system. Fort Atkinson State Historical Park —Planning and reconstruction of west barracks. Ash Hollow State Historical Park—Development of visitor center plan and installation of new water well. Recreation Areas—General —Addition and replacement of basic gen eral facilities ($70,200). Branched Oak State Recreation Area —Construction of maintenance building, beach renovation and campground planning. Fremont State Recreation Area —Construction of modern latrine and residence for superintendent. Schramm State Recreation Area —Planning services for aquarium education center complex. Walgren State Recreation Area—Installation of water well system serving lake water supply. Lake McConaughy State Recreation Area —Construction of residence for superintendent. Lake Ogallala State Recreation Area —Development of campground facilities. Sherman Reservoir State Recreation Area —Construction of mainte nance shop building.

Prairie Life Hunting Insects

Photo by Jon FarrarWALKING THROUGH the prairie's streamside woodlands, grassland meadows or across its shift ing dune sand, one is not aware of the struggle for life taking place at our feet. The day-to-day business of killing to live goes on among the insects just as surely as it does between the coyote and the field mouse, or the mink and the muskrat. Dragonflies dart across moss-choked sloughs, scooping up their prey with basketlike legs. Praying mantises wait motionless, their forelegs poised in a supplicating manner, and then lunge out to snatch up unsuspecting passersby. Metallic tiger beetles skate across the sand in search of their next meal. The struggle is as awesome as any in the animal king dom.

The prairie teems with insects of all vocations: the prodigious grass hoppers that ravage plants of all sorts; tumblebugs that roll their balls of manure provender before them; and the mound-building harvester ants. The number of their kind is astound ing. A prairie state like Kansas hosts an estimated 15,000 to 18,000 differ ent species of insects. Of all the grassland insects, none are more interesting than the predatory species-those that kill others for food.

It would be difficult to estimate the number of predatory insects in any particular prairie environment, but we can be sure that they are far less in numbers and in species than those vegetarian insects upon which they prey.

The evolution of predatism among insects has followed divergent paths so that today we find species that ply their deadly trade in every imaginable way. The great majority of predatory insects depend upon other, less active vegetarian insects for food. This indicates that they are of a more recent origin than their vegetarian prey and probably evolved after that supply of food became plentiful. Fossil evidence indicates that the first insects appeared some 405 million years ago and that predatory insects, like the gigantic dragonflies of the lush carboniferous forests, are first recorded some 345 million years ago.

Examination of today's hunting insects shows many specialized structures that enhance predatory proficiency. Yet, at the same time, one is amazed with the minimum of modifications that were made as some insects changed from plant eaters to animal eaters. Out of necessity, the jaws of most plant-eating insects are sharp and powerful. When the occasion presents itself, many of these vegetarians, like the katydid, will bite at and feed on other insects. Cases of these insects becoming temporarily predatory are well known to entomologists. This is good evidence that when vegetarian insects become carnivorous, their mouth parts and digestive apparatus are well fitted for their new mode of life. Most of the modifications that predatory insects have made over the millions of years that they have been evolving are refinements of their bodies and behavior to aid in the capture of prey. These specializations are what make predatory insects so fascinating.

One of the best known predatory insects is the praying mantis. The mantis is a traditionalist when it comes to capturing prey, using no special poisons, ploys or beguilement. Rather, the mantis is ever alert to potential prey, which he snatches up with lightning speed.

Though of fearsome disposition, the praying mantis is the most elegant of insects. Their lithe, responsive bodies are well designed for rapid travel through the tangles of plants where they hunt. The fact that their closest relative is the cockroach seems in credible.

The mantis's forelegs are specialized for seizing and holding insect prey. The outer three segments fold on each other to form an enclosure lined with horny raptorial spines. When at rest, the death-dealing machinery is folded back, praying fashion, against the chest. But, when a potential victim passes by, the forelegs are thrust out and a hook on the very end draws the insect back between the two saws where it is held and consumed at leisure.

First the mantis bites at the neck to destroy its prey's power of movement. Because of this mode of attack, and its aggressive nature, the mantis can capture and subdue insects as large as the locust. The appetite of a mantis seems insatiable. So much so, in fact, that males lingering after mating often end up the meal of their mates.

Among the most interesting winged predators are species of the wasp family. Some are nectar feeders, but kill or paralyze prey insects to feed their larvae; others are insect feeders themselves. Some wasps are solitary, others communal.

Carnivorous, solitary wasps are of particular interest because of their selectiveness when it comes to prey and their practice of provisioning their nests. The brown and yellow mud dauber, that attaches its nest to the rafters and eaves of barns and houses, is a good example.

Methodically, the dauber carries mud in its mandibles from a nearby streamside or rain puddle and tacks it on its chosen place. Unlike some species that mix saliva with their nest material to help it set up, the mud dauber simply sticks it in place and works it into tubular cells.

With nest complete, the female

dauber goes about the chore of pro

in sects

38

NEBRASKAland

MAY 1975

39

visioning each cell with insect larder.

Typically, she selects another predatory arthropod, usually a species of

crab spider. Delicately, she stings the

spider, just enough to paralyze and

immobilize it, but not enough to kill

it. Returning to the nest with her prize,

she places it in one of the cells and

leaves to hunt for more. After the cell

is filled, often with as many as 20

spiders, she lays a single egg on one

of the spiders and seals off the cham

ber. In a matter of days the young wasp

grub will hatch out, surrounded with

a room of food to sustain it until it is

ready to break through the cell's mud

cap and assume life as an adult mud

dauber.

visioning each cell with insect larder.

Typically, she selects another predatory arthropod, usually a species of

crab spider. Delicately, she stings the

spider, just enough to paralyze and

immobilize it, but not enough to kill

it. Returning to the nest with her prize,

she places it in one of the cells and

leaves to hunt for more. After the cell

is filled, often with as many as 20

spiders, she lays a single egg on one

of the spiders and seals off the cham

ber. In a matter of days the young wasp

grub will hatch out, surrounded with

a room of food to sustain it until it is

ready to break through the cell's mud

cap and assume life as an adult mud

dauber.

Though several species of hunting wasps may live in a small area, there is little direct competition for living space or food. Each species nests in a characteristic location: the digger wasp in subterranean tunnels, the mud dauber under bridges and buildings, and the social paper wasps build their nests of regurgitated wood and sticky saliva in any protected site available. The wasps are even more rigid when it comes to selection of appropriate prey. Some species are so specialized that they will stock their nests only with one or two species of spiders.

Just as each species of wasp occupies a unique niche in the environment, so do other predatory insects. One of the most notable of these winged hunters is the robberfly. These vigorous, robust creatures are addicted to capturing insects on the wing. Their appearance is formidable. A horny, downward directed proboscis, surrounded by a tuft of hairs known as the "mouth beard", is topped by large, bulging eyes. The body is stout and hairy. The long, spiny legs end with a bristle between each claw.

Robberflies are powerful aviators and scoop up their prey in a basket formed by their long, fringed legs. Once the insect is captured, the robberfly carries it to a convenient perch and pierces it with his proboscis. The victim collapses immediately, probably injected with a toxic or narcotic substance. A powerful digestive fluid is pumped into the unfortunate prey and the vital, nourishing body fluids are sucked out. Robberflies are especially sporting at their deadly game, selecting large and worthy quarry. Wasps, bees, ants, flies and beetles are the robberfly's usual fare.

Another winged predator, not unlike the robberfly in temperament and culinary tastes but disguised with gay colors, is the dragonfly. Fossil evidence indicates that dragonflies are the oldest of insect predators, and in deed, they are wonderfully adapted for making their living at the expense of others. Their two pair of membranous wings make them highly mobile; able to hover over potential prey or to dart to and fro in erratic flight pursuing some hapless fly or mosquito. The dragonfly is one of a handful of insects whose head pivots freely. In flight or on a roost, the dragonfly's head swivels constantly as the large, compound eyes scan for the next meal or an insectivorous bird that would make a meal of him. Like the robberfly, the dragonfly captures its prey on the wing in its bristly basket of legs. Its mouth parts are adapted for biting and crushing, so unlike the robberfly, small prey is simply jammed in, and large insects are torn apart and consumed. So greedy are their feeding habits that an entomologist reported finding one with so many mosquitoes crammed into its mouth, probably more than a hundred, that the jaws would no longer close.

While adult dragonflies are the terror of flying pond insects, their aquatic nymphs are the tyrants of the under water world. Depending upon the species, these developing, wingless insects spend a matter of months or years feeding and growing prior to their metamorphosis into adults. During this time, few aquatic organisms, be they minute protozoa or small fish, can live a fearless life.

In the shadowy world of the pond, only one insect can challenge the dragonfly nymph in voracity —the giant water beetle. As with the dragon flies, both the larva and the aduit are predatory. The adult, though, remains fully aquatic, leaving the water only to move to new hunting grounds in other ponds. The larvae are equipped with hollow, sickle-shaped jaws with which they grasp their prey and suck the body fluids. Adult water beetles sometimes attain lengths of 1 1/2 inches and are excellent swimmers, propel ling themselves with their bristly, fringed legs. Adults attack all that comes their way, especially other in sects and small fish, which they seize with their mandibles, chew and swallow.

The tiger beetle is a land insect that, like both the dragonfly and the water beetle, is an aggressive predator in the larval and adult stages. When full size, the larva is about one inch in length. The forepart of the body, including the head, is hard and chitinized; the remainder is tender and white. When hunting, the tiger beetle larva occupies a nearly vertical tunnel, about the size of a lead pencil, situated in an area well used by other insects. When in position, the head is at ground level and the mandibles are spread like a trap. As an insect passes by, the larva lunges out, grabs it and retreats back into its tunnel.

The adult tiger beetle is just as effective a hunter as the larva but with a less devious approach. A common species in Nebraska is a metallic, maroon and cream species often seen dancing across sandy beaches or among sandhill yucca. Their eyesight is apparently excellent and their slender legs are well suited to the chase. Formidable mandibles give it a fearsome hold on prey that they run down.