NEBRASKAland

April 1975

NEBRASKAland

VOL. 53 / NO. 4/ APRIL 1975 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Fifty cents per copy. Subscription rates $5 for one year, $9 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. commission Chairman: Jack D. Obbink, Lincoln Southeast District (402) 488-3862 Vice Chairman: Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 2nd Vice Chairman: Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-Central District, (308) 745-1694 Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-central District, (308) 452-3800 H. B. (Tod) Kuntzelman, North Platte Southwest District (308) 532-2982 Director: Willard R. Barbee Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, Jr. Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: Jon Farrar Greg Beaumont, Ken Bouc, Steve O'Hare Contributing Editors: Bob Grier Faye Musil, Tim Hergenrader, Roland Hoffmann Layout Design: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1975. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Lame and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska Contents FEATURES TOUGH AND SILENT TRAILS 8 10 ARBOR DAY-A CENTURY PLUS THE DEER OF NEBRASKA a special 34-page feature on the life history of white-tailed and mule deer ADJUSTING TO CHANGING TIMES FACTS OF LIFE MAINTAINING THE BALANCE TECHNIQUES FOR HUNTING DEER MONEY WELL SPENT 42 FISHING AN EARLY START .44 NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA/PRONGHORN ANTELOPE 50 DEPARTMENTS TRADING POST 49 COVER: A mule deer fawn pauses for a drink from Chadron Creek. Photo by Lou Ell. OPPOSITE: A friendly great-homed owl poses for camera in his territory near McCook. Photograph by Bob Grier. BACK COVER: Endangered peregrine falcons, painted by Ron Jenkins. Art courtesy of National Wildlife Art Exchange, Inc., P.O. Drawer 3385, Vero Beach, Fla. 32960, all rights reserved, and reproduced here with permission.

TOUGH AND SILENT TRAILS

POET ROBERT FROST once wrote:

"Two roads forked in a quiet wood And I, I took the one less traveled", and those words came to mind as we shouldered our packs at the entrance to Indian Cave State Park. Duane Westerholt, who works for NEBRASKAland, had been telling me about the comprehensive plans for develop ing this park. Together with our wives, we decided to do some exploring and camping while there was still an opportunity to take the "road less traveled."

The last land parcels had been added to Indian Cave State Park the year before, culminating many years of planning and preparation. Long before the surveying and road grading began, quite a few southeastern Nebraskans were enjoying the park. That corner of Nebraska has needed such a major park for a long time, and the location couldn't be much better.

It's situated on the Missouri River nearly equidistant between Brown ville and Rulo. The closest hamlets are Shubertand Barada.

To get there, we went south out of Nebraska City on Highway 73-75 to Highway 62. Indian Cave Park lies straight east on Highway 62. At Shubert, the highway becomes county road for the last few miles.

We arrived at the park entrance about 8:30 on a blustery Saturday morning. Relying on trail maps, topographical maps and some seat of-the-pants or intuitive directions from Suzanne and Janice, we chose a route along the western edge of the park for our morning leg of the hike.

Our first impression was that we weren't still in Nebraska. The rolling hills and meadows, accented with groves of trees, brought visions of the Ozarks or Pennsylvania Dutch country. It was green and growing every where, with thick, wild grass up to our knees, and big, old oaks standing out here and there.

Making our way cross country, we seemed to be feeling the beauty as much as seeing it. Those feelings gave way to others —we were feeling pooped. Two hours of steady hiking, even with light packs, and our thoughts of poetry had turned to perspiration. The nice thing about back packing is that weariness always seems to coincide with some good excuse to take off your pack and take a closer look at nature firsthand.

Our quick calculations after study ing the maps indicated we must be close to the St. Deroin cemetery. We decided to make best use of our rest stop by going to look for it, and we didn't have far to go. Reaching the crest of a nearby hill, bleached stone markers just seemed to appear as though they were growing there. It was a bit eerie. No entrance, no trimmed hedges, no fences gave the formal hallmarks of a cemetery. There were only tombstones, quiet in a meadow, holding final sentences to history no one may ever know.

We spent an hour there, taking photos and thinking about what had gone before. Then, it was back to our packs. From the western boundary of the park we headed toward the Missouri River. On the way, the trail got tougher and the scenery changed again. Never on the level, we were either walking uphill or downhill as we crossed ridges and ravines that parallel the river.

The heavy woods seem like a wonderland to those who envision Nebraska only as flat farmland. There was oak, elm, ash, hickory, locust and Cottonwood. Heavy underbrush added to the seclusion —leaves were budding out everywhere —and the silence was sweet with a fragrance of blossoms.

During that part of our hike we made our most helpful discovery: an old windmill, still pumping cold, clear water. Although we had planned to carry enough water, it quickly disappeared with the exertion of hiking. The day also turned out to be much warmer than the morning had promised. Without the windmill, our plans to camp overnight would have been shot. The windmill was on an old farmstead, and we spent the rest of the morning exploring its remains.

An hour later, we were having lunch on the bank of the Missouri River. There seemed to be mushroom hunters behind every tree. We asked and learned that morels are an easily distinguished member of the mushroom family with a very delicate flavor. And, hunting for them appears to be as contagious as fishing and golf.

Morel hunters consider it an annual tradition, and some of the oldtimers we talked with that Saturday after noon told of "hunting" Indian Cave for as long as they could remember.

Apparently we were near too many hunters, for we got the bug. Euell Gibbons would have been proud of us, grubbing around in the decaying remains of fallen oaks to get part of our supper. Our afternoon foray was well worth it, as the morels far exceeded the scheduled freeze-dried carrots on the menu. Of course, the appetites we worked up looking for them may have had something to do with it.

With the Saturday night supper over, we contentedly contemplated a beautiful sunset and its influence and interplay on gathering thunder heads. Evenings on a campout always seem to be the finest moments of the trip, perhaps because we weren't walking then. So, we decided to find the nearest, highest vantage we could and watch it get dark.

From there, the combination of a full stomach, heavy eyelids and threat ening storm helped us decide to can cel our plans for Sunday. Our schedule had called for us to hike to the southern edge of the park to explore the cave for which Indian Cave is named. Instead, we agreed to head back to our car and save the rest of Indian Cave for a fall outing.

That night the storm did come, and it blew like fury...or at least that's what Janice told me the next morning. Sunday started with a quick, cold breakfast and the unpleasant chore of repacking our soggy gear.

On the way out, we discussed the future of Indian Cave park. We had chosen the "road less traveled," but others may well choose a paved one. The real beauty of Indian Cave may be that when "two roads fork in a quiet wood", each of us can choose the one we prefer.

Photos by Duane Westerholt

ARBOR DAY A CENTURY PLUS

AMERICAN AS apple pie, Arbor Day has been called the grand-daddy of our nation's conservation move ments. Born of expediency on Nebraska's prairies in 1872, Arbor Day shares that venerable honor with Yellowstone National Park, created in the same year. Both Arbor Day and the national park concept are world wide today!

No observance ever sprang into existence so rapidly as Arbor Day. Other holidays repose upon the past; Arbor Day proposes for the future. Its author, J. Sterling Morton —editor of the first newspaper in the Nebraska Territory, Governor of that Territory, secretary of the Nebraska State Board of Agriculture, President of the American Forestry Association, and U.S. Secretary of Agriculture in the Cleveland administration —found many opportunities to persuade others of the importance of planting woodlot, fruit and shade trees.

Through Morton's efforts, April 10, 1872, was proclaimed Arbor Day in the state of Nebraska. More than a million trees were planted on that day and prizes awarded the individual and county agricultural society plant ing the greatest number. In 1885, the State Legislature designated April 22, birthday of J. Sterling Morton, as Arbor Day, making it a iegal holiday. With no more than a 3% native tree cover, and that chiefly along its streams, and in a region where even the geographies stated that trees would not grow, Nebraska became a leader in tree culture, earning the name of "Tree Planter's State" in 1895!

It is Ohio, however, which holds the all-time record for tree-planting ceremonies. The event took place on April 27, 1882, in Cincinnati, where the newly formed American Forestry Association had called an American Forestry Congress. And, 25,000 people came. Schools were closed. Under the direction of B. G. Northrup, Congregational minister and educator, a procession of children and enthusiastic patrons marched from city center to Eden Park, to be met by a 13-gun salute. Platforms draped with buntings, and lemonade stands, lent a festival atmosphere. Young trees were planted as memorials to presidents, heroes, famous citizens, authors, pioneers.. ."and the band played on." Perhaps unaware of Nebraska's earlier action, Northrup promoted the idea of an annual day for tree planting by schools all over the eastern states, following the "Cincinnati" plan...even providing the literary exercises for the occasion. Many persons believed Northrup had invented the day. His emphasis on plant ing trees as memorials and involving youth groups were important.

By 1892, Arbor Day was already a holiday in 40 states and territories, and in several countries. By the 1930s, the day was officially observed in each of the 48 states and in a growing number of countries around the world. During the following two decades it was reduced to minor importance in many American schools and communities, causing a few concerned persons to ask: "Whatever became of Arbor Day?" Perhaps such widely advertised planting projects as those of Weyerhaeuser, Georgia-Pacific, state and national forest agencies, made the small tree-planting ceremony seem unimportant.

Hoping to revitalize the day, Edward H. Scanlon, tree commissioner for the city of Cleveland, had begun the promotion of a National Arbor Day to be held the last Friday in April. Thirty years of effort on the part of his Committee and associated groups were culminated in 1970, when President Richard Nixon proclaimed April 24 of that year as National Arbor Day. Amended shortly before its passage, the original House joint resolution was intended to make Arbor Day an annual observance. A resolution designating the last Friday in April as Arbor Day was referred to the Judiciary Committee in December, 1973.

Approximately 25 states already observe Arbor Day on the last Friday in April. The date varies among other states with local climatic conditions. Southern states have, traditionally, chosen earlier months. Western Oregon has observed the second Friday in February; eastern Oregon, the second Friday in April. Pennsylvania has two Arbor Days, in April and November!

Like many other customs, Arbor Day is rooted j'n man's heritage. In the Fifth Century, leaders of the Swiss community of Brugg, envisioning the need for a forest park in future years, encouraged the townspeople to plant a dozen sacks of acorns, offering each a wheaten roll for his efforts. When the acorns failed to sprout, the people transplanted young oaks to the site, initiating a holiday celebrated to this day.

The Aztecs are known to have planted a seedling whenever a child was born. Since ancient times, the people of Palestine have celebrated a day known as Tu B'Shebat by plant ing a cedar sapling for each male child born in that year; a cypress for each girl child. Jews throughout the world celebrate the day by sending money to Israel for tree planting on slopes barren for more than a thousand years.

It was never more important that "islands of green" be planted across our nation, and that Arbor Day not be relegated to the little red school house. A revitalized Arbor Day has become a spearhead in the new environmental thrust...at a time when one million "acres of green" are being paved with masonry and asphalt each year. A native bluestem prairie near Nebraska's own capital, a research area for the University of Nebraska's plant and animal ecologists for nearly half a century, is to day a concrete airport!

On the very eve of the 100th an niversary of Arbor Day in the U.S., 1972, came the tragi-comic news that atmospheric pollutants in the Los Angeles area were responsible for that city's launching an experiment with plastic highway plantings!

With its growing concern for good earth keeping, 1975 is the year to do away with any "deadwood" surround ing Arbor Day, to look closely at its broader facets... emphasizing the proper use of existing forests, the recycling of used paper and other wood products which demand so great a toll of America's trees each year. To day's forestry is concerned with faster growing, more flawless trees through altered chromosomes, controlled seedlings, speeded carbon dioxide intake and other V.I.P. treatment for young trees that are to become part of tomorrow's forests. Douglas fir mar keting time may be cut to forty years;" no small consideration when it has been estimated that in a recent year the U.S. consumed enough wood to build a 1 2-foot-wide, 1-foot-thick walkway to the moon!

The thousands who annually visit Arbor Lodge State Historical Park at Nebraska City gain a closer look at the man, J. Sterling Morton, founder of Arbor Day, whose home it was from 1855-1902. The National Broadcast ing Company brought it to the American television public on Arbor Day in 1947. The stately white, columned mansion, now a museum, evolved from a 4-room structure built by Morton in 1855 for his bride, Carolyn Joy Morton. Terraced gardens, shade trees, carriage house and arboretum planted around an open meadow, draw the visitor outside. The arbore tum, designed in 1903 by Frederick Law Olmsted, noted landscape architect who designed New York City's Central Park, includes at least 300 plantings and 170 different species.

Pausing before a bronze statue of the Tree Planter and author of Arbor Day in its grove of native trees, the visitor seems to hear J. Sterling Morton's own maxim echo clearly: "Let the trees he plants be a man's best monument!"

NEBRASKAland proudly presents the stories of its readers. Here is the opportunity so many have requested-a chance to tell their own outdoor tales. Hunting trips, the "big fish that got away", unforgettable characters, outdoor impressions—all have a place here.

If you have a story to tell, jot it down and send it to Editor, NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lin coln, Nebr. 68503. Send photographs, black and white or color, too, if any are available.

the Deer of Nebraska

Photo by Greg Beamount

Adjusting to Changing Times

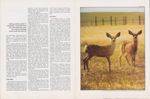

Photo by Greg BeaumontNEBRASKA'S APPEARANCE today is greatly changed from its territorial, prestate days; so much so that it is difficult to imagine our vast, grass covered plains without today's cities, roads, fences, farm and ranch build ings and other contributions of progress. This "sea of grass" of yesteryear was liberally sprinkled with sunflow ers, wild legumes, wild rose, buck brush and other low-growing shrubs. Streams in central and eastern Nebraska-the Loups, Cedar, Dismal, Calamus, Blue, Nemaha, Elkhorn, Niobrara and many of their tributaries — added variety by supporting a scrubby growth of wild plum and chokecherry along their banks. Tim bered areas were restricted to the Missouri River region and to other stream banks in the eastern portion of the state.

Diaries of some of the thousands of gold-seekers and settlers who followed the Platte River across this territory in 1849 and the early 1850s repeatedly mention a treeless country with very few deer observed until they reached what is now Scotts Bluff County. There they reported numbers of deer, antelope and mountain sheep. Whitetails were abundant along the Missouri River on our eastern bound ary according to the Lewis and Clark record of 1804.

We cannot say how long deer have been in Nebraska, but archaeologists have found that they were of great importance to the inhabitants of this area as early as 300 A.D. We do not know whether these ancient deer were of the same species we know to day; only that they were of the same group (genus Odocoileus) as our present deer. Evidence of them fades after about 900 A.D. when buffalo became the all-important species. During the 1800s, trappers, explorers and early white settlers entering the Nebraska territory found both white tailed and mule deer, the same species seen today.

During the last 100 years or so the deer have fluctuated from abundant to near extinction and are now abundant. Today there are probably more deer within our boundaries than there were when the settlers began arriving in numbers in the 1850s.

Nebraska's deer herds were reduced to a very low level by excessive harvests during the late 1800s. The Game and Fish Commission's report for 1901-1902 estimated there were about 50 deer in the state. In 1907,

Photo by jon Farrar

Photo by jon Farrar

the Legislature passed a provision prohibiting the taking of deer. The recovery of our deer populations from the extremely low numbers of the early 1900s was very slow, and as late as 1919 some authorities thought that deer were doomed to extinction in the state. By the mid-1930s, occasional deer were seen in the western and central portions of the state. Mule deer were the first to return, perhaps because of movement from the west. With the exception of a few whitetails transplanted to southeast Nebraska, there has been no stocking of deer in the state.

In the late 1930s, deer had in creased to the point where their presence was known at various points in the state. Game Commission surveys in the winter of 1939-1940 found be tween 2,000 and 3,000 deer, mostly mulies, in the Pine Ridge area and in the Platte and Niobrara River valleys.

Complete protection from hunting allowed deer to continue increasing in numbers and range, and deer now occur in every county in the state. A limited hunting season was held in 1945, with annual seasons since 1949. Only a portion of the Panhandle was open to hunting in 1949, but the amount of area was gradually in creased, until the entire state was open in 1961. Today's deer herd numbers near 100,000. Habitat limitations and regulated hunting have stabilized the population over most of Nebraska but some areas are still experiencing increases.

In historical times, two species of deer have been native to Nebraska. The white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) is the most abundant big game animal in North America. Its various subspecies range from the Atlantic to the Pacific and from the latitude of Hudson Bay in Canada to the Isthmus of Panama. Mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) occur from Great Slave Lake in the north to a line about even with the southern end of Baja California, and range primarily west of a line through eastern Nebraska. The subspecies found in Nebraska are Odocoileus virginianus macrourus, the Kansas whitetail, and Odocoileus hemionus hemionus, the Rocky Mountain mule deer.

The fallow deer (Dama dama), a native of Europe, was introduced in east-central Nebraska in 1939. In 1955 the population was estimated at 300-350, but has steadily declined to approximately 50 deer.

From a low of 50 deer at turn of the century, Nebraska's herds have increased until now there are about 100,000 in the stateWhitetails have been recorded in all Nebraska counties. They are the most common species roughly east of the Harlan-Furnas County line on the south and the Keya Paha-Cherry line in the north. Mule deer are the predominant species west of this line. A considerable portion of the state, particularly west of Grand Island, has a reasonable degree of overlap of the two species, although whitetails are unusual in a few western counties, and vice versa.

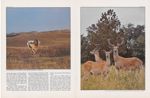

As with any species, densities of deer are dependent on quality of the habitat. Over most of Nebraska, the best habitat is along stream courses and the associated river breaks. Deciduous trees, primarily Cottonwood, ash, willow, elm and box elder are generally distributed along stream courses. Oak and red cedar occur along some drainages. Basswood, walnut and maple occur occasionally. Associated shrubby vegetation in cludes plum, sumac, chokecherry, buckbrush (snowberry or coralberry), wild rose and several other species. River breaks are often characterized by deep gullies and ridges with generally sparse but occasionally heavy, woody growth. Associated croplands often provide much of the food requirements, and seasonally may provide necessary cover also. However, following crop harvest, deer pull back to woody cover for necessary concealment.

Throughout the state, but consider

ably more so in the eastern part, are thousands of miles of shelterbelts. A combination of hardwood trees, shrubs and red cedar are usually found in these plantings. They are often used by deer for cover, but may not be occupied on a year-round basis if considerably removed from stream courses.

Natural stands of ponderosa pine are found in parts of western and north-central Nebraska, and provide some of the highest deer densities. The Pine Ridge, in the northern part of the Panhandle, is the most extensive habitat of this type, covering about 650 square miles. The Wildcat Hills and Cheyenne Escarpment in Banner, Morrill and Scotts Bluff counties also have ponderosa, generally in sparser stands than in the Ridge. Ponderosa extends for about 120 miles along the Niobrara River and occurs on most of its tributaries within this span.

Woody cover provides the best deer habitat, but it is certainly not essential. One biologist stated that the only areas which could be excluded as deer habitat are water and concrete, and this statement is not far from true. Grasslands are suitable, particularly where topography aids in providing necessary concealment. The Sand Hills occupy about 20,000 square miles and deer are found throughout this area. However, densities are generally considerably lower away from stream courses, except where vegeta tion around lakes and marshes provides heavier cover.

Whitetails are found most frequently along stream courses, and a map of whitetail harvest distribution would plot the stream courses even if you didn't know where they were. Even where whitetails are comparatively minor on a countywide basis, they are often the predominant species in this habitat type. Mule deer also occupy stream courses, and they are generally the more abundant species in the breaks and upland within the area of major range overlap.

The Facts of Life

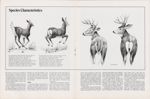

Photo by Jon CatesTHE WHITE-TAILED deer is so named for its most distinctive feature, its large tail or "flag." The underside of the tail is pure white and is usually exposed when fleeing. The upper surface is colored similarly to the rest of the coat—normally reddish brown in summer and buff in winter.

Mule deer are named for their prominent, mule-like ears, which measure about one-fourth larger than in whitetails. This super abundance of ears is compensated for by shortness of the tail, which is about two-thirds as long as in whitetails. The mule deer tail appears rounded, is white with a black tip, and is carried down when running, rather than erect. The summer coat is basically reddish brown, but more yellowish than in whitetails. Winter pelage is generally plain gray.

Both species have white bellies. However, the mule deer's brisket is a rich brown. Summer hair is relatively fine and silky in texture. The winter coat is much coarser and thicker, providing good insulation against cold.

Additional distinctive features between species are: a prominent white rump patch on mule deer, which is lacking on whitetails; the stiff-legged bounce of mule deer, compared to the easy lope of whitetails; the metatarsal glands, on the outside of the hocks, which are about four inches long in mule deer and only an inch in white tails; and the antlers, which will be discussed later.

Fawns have coats with background color similar to the summer coat of adults, but with white spots on the back and sides. These spots become less obvious during the summer, through wearing of the hair, and disappear by the time fawns are about three months old.

Deer are blessed with an acute sense of smell, good eyesight, and a keen sense of hearing, all of which are important in avoiding enemies. Primary reliance is probably on scent. Since they are color blind, stationary objects are often overlooked.

Age and AgingLongevity records of captive deer have shown whitetails living as long as 19 years and mule deer, 22 years. Records for tagged deer in Nebraska have been 101/2 years for a whitetail doe and 9Vi years for a mule doe, both of which were taken during hunt ing seasons. During recent hunting seasons, very few bucks have been taken as old as W2 years, and only about 2 percent of the whitetail and 4 percent of mule does reach this age.

Although weight and antler size are related to age, both are highly variable and the only accurate aging is through examination of teeth. As a field technique, tooth wear and replacement is the most reliable method available. Fawns generally have four cheek teeth, three premolars, and one molar on each side of the upper and lower jaws. Long yearlings add two more molars, with the third not fully erupted. Temporary premolars, which are shaped differently than the adult ones, are replaced after 11/2 years, so that most deer with permanent pre molars during the hunting season are 21/2 years or older. From this point on, age can be determined with a fair degree of accuracy by the amount of wear on premolars and molars.

For more precise aging, a section of the center incisor (front tooth) will reveal markings which permit designation of age similar to reading fish scales. This is a time consuming and comparatively costly process, but where greater accuracy is desirable, it is necessary.

A common fallacy encountered in Nebraska is aging by the external appearance of the incisors, similar to the method used for sheep. However, since all four pairs of permanent in cisors may be present at 1 1/2 years, and are almost always present at 2 1/2 years, this method is obviously unworkable. The only worse method is calling a deer ancient because the upper incisors are gone. Even a fawn would be ancient by this method, since deer have no such teeth.

WeightAt birth, female whitetails average 51/2 pounds and males are about 2 pounds heavier. Mule deer are of similar size. By fall, whitetail fawns have outstripped mulies in weight, averaging about 15 percent more. Whitetails maintain a weight advantage, and in older animals average from 8 to 16 percent heavier.

At the time of the November hunting season, buck fawns are about 7 percent heavier than does of the same age. This difference increases proportionately with age —yearling bucks are 20 percent heavier, and by 2 1/2 they are 40 percent heavier.

The heaviest mule deer recorded in recent years, taken in Garden County in 1957, weighed 310 pounds hog dressed, which would amount to about 378 pounds live weight. The record whitetail, killed in Cherry County the same year, weighed 287 pounds field-dressed, or about 350 pounds live weight.

The largest fawn, a whitetail male taken on the De Soto Refuge in mid December of 1963, weighed 102 pounds dressed. The heaviest doe recorded, also a whitetail from De Soto, weighed 165 dressed.

Weights vary among individuals of

the same sex and age according to area and physical condition, primarily due to nutrition. Time of year has a considerable effect, and time of birth will affect weights of fawns taken during the hunting season. Genetics may also be a factor, but this is minor compared to nutrition.

An indication of weight differences by area can be obtained by comparing average weights of yearling bucks. The lightest whitetails are those from the Pine Ridge (109 pounds) and the heaviest are from the Elkhorn Unit (129 pounds). Variations in mule deer are not as great, with an average of 103 pounds in the Sand Hills at the low end, and 116 pounds in the Platte Unit for high.

AntlersThe most prized part of the deer for a trophy, the antlers, generally vary sufficiently between species to permit differentiation. In whitetails, the points on each antler usually rise from a single main beam, much as the points on a garden rake. On the other hand, the mule deer's antlers are basically in the form of the letter "Y" and the upper ends fork to form two smaller "Ys". Both species commonly have a brow tine.

Most buck fawns develop "buttons" by fall, which are generally not visible above the hairline. These are hard ened antlers which are shed. Subsequent antlers are also shed each year. Time of shedding varies among individuals and somewhat by area. During a mid-December season on the Valentine Refuge, one-third of the whitetail bucks had shed one or both antlers. However, similarly timed seasons on the De Soto Refuge produced no evidence of antler shedding. Most bucks drop their racks in January and February, but rarely may carry them into early May.

Antler growth commences normally in late April to early May. These new antlers are tender and velvet covered, with the velvet shed in early September on almost all bucks. An occasional male, possibly one-half of one percent, does not shed the velvet.

A very small portion of does also develop antlers. In an average year, two or three of these are taken in Nebraska. Such antlers are small, normally only a spike or two points on a side, and are velvet covered.

Terminology on numbers of points is somewhat confusing. Most states east of Nebraska count all points on both antlers, thus a deer with four points on each antler would be an eight point. In Nebraska and states to the west, only the points on one antler are counted, and this same deer would be a four point.

Contrary to some opinions, numbers of points are no indication of age, but they are of some value in judging condition. However, antler beam diameter is a better indication of condition, and may generally be used in Nebraska to differentiate yearlings

Rutting activity peaks in

November, most fawns are

born the following June.

Over half of whitetail

fawns mate the next fall

Rutting activity peaks in

November, most fawns are

born the following June.

Over half of whitetail

fawns mate the next fall

from older deer. If the beam circumference 1 inch above the burr is greater than 3 5/16 inches on white tails, or 3 1/16 inches on mule deer, the buck is generally 21/2 years or older.

For yearling whitetails, the most frequent point class is 3 on each side, with about 26 percent falling into this category. The next most common is 4 on a side, with 17 percent. About 7 percent have only spikes, and 1 percent have 5 points per side. The average is about 5.7 points, counting both sides. On older whitetails, four points per antler is the most frequent. Typical heads seldom exceed seven on an antler.

Fifty-five percent of yearling mule bucks have two points on each antler. About 10 percent have spikes, and 2 percent have 4 points or more. The average is 4.2 points on both sides. The typical good rack, with 5 points (including brow tine), is attained by 16 percent of 21/2-year-olds and 34 percent of the older bucks.

These point categories vary some what by area, and figures listed are statewide averages.

Food HabitsNebraska data regarding food habits relate primarily to samples from mule deer taken during firearm seasons. In the Pine Ridge, agricultural crops comprise 41 percent of the food with corn (19 percent), green wheat (11 percent) and alfalfa (10 percent) of major im portance. In this same area, buck brush makes up 13 percent of the November diet, and ponderosa pine comprises 18 percent.

In the North Platte Valley, where 51 percent of the diet consists of crops, corn (19 percent), beets (12 percent), and green wheat and alfalfa (each 8 percent) are of particular significance. Here, buck brush (13 percent) and cottonwood (6 percent) are the major woody species used.

On the Bessey Division of the Nebraska National Forest near Halsey, where no crops are available, woody plants comprise 77 percent of the food. Primary species used are buck brush (32 percent), jack pine (23 per cent), and wild rose (13 percent). Sunflowers comprise 15 percent, soapweed 3 percent, and miscellaneous grasses and sedges, 4 percent. Small samples from the Bessey Division for spring and autumn show grasses and sedges making up about 34 percent and 6 percent, respectively, of the diet. In autumn, wild rose (34 percent) and red root (21 percent) are the most important foods.

We have little data for whitetails in Nebraska, but can obtain a good indication, at least for agricultural areas, from neighboring states. In northeast Kansas, corn is the single most-used plant in all seasons except summer, and makes up about 29 percent of the year-around diet. Other important items are sorghum and coralberry, each with 8 percent, and winter wheat and oaks with about 6 percent each. Forbs (weeds) comprise about 43 percent of the summer diet and contribute about 11 percent on the year round basis.

In Iowa, agricultural crops comprise 56 percent of the food volume, with corn (40 percent) and soybeans (13 percent) most important. Woody vegetation, with 21 percent, and forbs with 18 percent, comprise most of the remaining foods.

Data from northern Missouri show 41 percent agricultural crops in the diet, but oak leaves and acorns (25 percent) are as important as corn (21 percent). Forbs (14 percent) and browse and wild fruits (12 percent) are also important.

In all three states mentioned, alfalfa is little used, although whitetails are very commonly observed on alfalfa fields. In all studies, grasses are only a minor constituent in the year-round diet.

Life HistoryThe breeding season, or "rutting period" of both white-tailed and mule deer, commences in mid-October, with the peak normally in mid to late November. There is no fixed bond between buck and does, such as would be indicated by the words monogamy or harem, and one buck may mate with a large number of does. The number of does which may be serviced by a buck is dependent mainly on distribution. In one study, 19 of 21 does penned with a single buck produced fawns. However, where deer densities'are low it is doubtful that one buck would mate with so many does.

Bucks are generally capable of breeding at 1 1/2 years of age, although at least a portion of whitetail bucks produce viable sperm as fawns. The majority of whitetail does and a small portion of mule does breed when six to eight months old.

Does come in heat for about 24 hours at intervals of 28 days or so, and normally go through three heat periods if not bred earlier. Some breeding occurs from at least mid-October to early February in mule deer, and until mid March in white tails.

Information regarding pregnancy rates has been collected primarily from road-killed does. Over a 12-year period, almost 1,000 does, of which about two-thirds were whitetails, were examined. There are some differences between parts of the state and between years, and the following data represent a composite.

The two species vary greatly in fecundity. About 61 percent of white tail females breed as fawns, whereas only about 7 percent of mule deer do so. The following year also shows a major difference, with 94 percent of whitetails and only 68 percent of mule deer pregnant as long yearlings.

The proportion of singles, twins and triplets varies between species and

Photo by Lou Ell Photo by Jon Farrar

Photo by Jon Farrar

among age groups. Seventy-eight percent of the pregnant yearling white tails carry twins or triplets, whereas only 52 percent of mule deer in the same age class have more than one embryo. Even in the older age groups, whitetails maintain the edge, with 1.95 embryos per doe compared to 1.63 for mule deer.

Using the average composition for age classes in the population, 100 whitetail does produce 137 fawns, while an equal number of mule does have only 94 fawns. Obviously, white tails are considerably more productive.

Gestation, the period from conception to birth, takes about 201 days. Based on estimates of embryonic development, fawning occurs from early May to early October. However, about half of the young of both species are born between late May and late June. Whitetails which breed as fawns bear young about three weeks later than older does. Most of the late births, and all of those after the end of August, are from does which breed as fawns.

Sex ratios run slightly heavy to males, with embryo counts showing 102 males per 100 females for white tails and 111:100 for mule deer. The fall harvest of fawns shows a some what greater preponderance of males than among embryos, with 107:100 for whitetails and 115:100 for mules. Survival could be slightly better for males, but apparent sex ratios could also be affected by behavior differ

Photo by Lou Ell Productivity Rates by Species and Breeding Age

Age When Bred Vi Year 1V2 Years 2V2 Year Plus

Species Whitetail Mule Whitetail Mule Whitetail Mule

Percent Pregnant 61 7 94 68 99 90

Percent Pregnant With: 89 86 22 48 19 19

Embryos per Doe 0.68 0.08 1.74 1.03 1.95 1.63

Percent of Total Doe Population 41 33 29 29 30 38

Percentage of Young Produced Annually by Each Age Class 20 3 37 32 43 65

Fawning success, and hence productivity of the herd,

is dependent upon many factors, including age of the doe and species.

Whitetails are generally more productive since nearly two thirds of the

year-old deer bear young. Multiple births

are more common in whitetails of all age classes, too

Productivity Rates by Species and Breeding Age

Age When Bred Vi Year 1V2 Years 2V2 Year Plus

Species Whitetail Mule Whitetail Mule Whitetail Mule

Percent Pregnant 61 7 94 68 99 90

Percent Pregnant With: 89 86 22 48 19 19

Embryos per Doe 0.68 0.08 1.74 1.03 1.95 1.63

Percent of Total Doe Population 41 33 29 29 30 38

Percentage of Young Produced Annually by Each Age Class 20 3 37 32 43 65

Fawning success, and hence productivity of the herd,

is dependent upon many factors, including age of the doe and species.

Whitetails are generally more productive since nearly two thirds of the

year-old deer bear young. Multiple births

are more common in whitetails of all age classes, too

ences which make the male fawn somewhat more vulnerable. At any rate, as in humans, males outnumber females at birth, but the degree of preponderance is much harder to determine for deer.

Although capable of a few steps shortly after birth, fawn activity is initially very limited. They are left by the doe while she forages for food, but she returns at intervals to check and feed them. Nursing takes about two minutes and is conducted at two or three-hour intervals.

During their first month, fawns do little wandering, remaining hidden for the most part with the spotted coat providing superb camouflage. They are virtually scentless for several days or more, which is of considerable as sistance in avoiding predation. Agility increases rapidly, and within one to three weeks fawns are able to evade capture by man.

Milk constitutes the entire diet initially, with some greenery added within two to three weeks. Normally fawns are weaned at about four months, but they are capable of surviving without milk in three months or less.

Survival of fawns does not follow entirely the lines indicated by the pregnancy rates presented earlier. For instance, triplets are not as commonly observed in whitetails as the indicated eight percent for all does which have fawns. Furthermore, although about 20 percent of the whitetail fawn crop is dropped by females which breed at 6 to 8 months of age, these fawns are generally born later and survival is probably not as good as for those born earlier. Fall age ratios generally show 110 to 125 fawns per 100 does for whitetails and 80 to 95 fawns per 100 mule does. Net productivity there fore is about 35 percent greater for whitetails, whereas embryo counts show a difference of about 46 percent.

Although fawns associate more closely with does as their activity in creases, it is early fall before they are seen together with a great degree of regularity. Frequently does are seen without fawns in August and early September, after which time they are almost always seen together. This close association may be partially broken during the mating season, but they continue to hang together through the rest of the winter. At or near fawn ing time, the ties are completely broken, and the previous summer's fawns are turned out on their own. This to a large part accounts for in creased mobility in May and June does searching for suitable fawning areas, and the short yearlings some what at a loss without parental guidance.

Numbers of deer in groups vary considerably by season. In summer, groups are small, often just a doe and her fawns or a few bucks or non-productive does together. These pull to gether gradually, and by early winter groups of 10 to 20 are common, while herds in excess of 100 may occur in higher population areas. Greatest congregations occur during heavier snows when ease of travel is restricted and more deer gather at the most favorable areas.

Although periodically active at all

In many areas, which are often cited as a general rule, deer may move only a mile or two from the place of birth. Exceptions occur with migratory herds of mule deer, which travel con siderable distances between summer and winter ranges, primarily between elevational differences. In the Great Lakes states, where yarding of white tails is common, movements may also be somewhat greater. A Wisconsin study showed an average movement of 3.4 miles, with a maximum of 12 miles, between winter yards and hunting season recovery sites.

The amount of movement apparently depends primarily upon the adequacy of the habitat. Whereconditions are best, movement is comparatively minor; in less suitable areas, move ments are extensive.

In Nebraska, deer occupy some habitats only on a seasonal basis. For instance, cornfields may provide good cover from July through October. At this time, deer may occupy fields con siderably removed from permanent cover, but must pull back to stream courses or other permanent vegetation during the remainder of the year.

Photo by Bob Grier

Photo by Bob Grier

Tagging studies have shown move ments in Nebraska which are considerably greater than normal. Recoveries of 23 whitetails which were tagged in the Sand Hills showed an average movement of 38 miles. A yearling buck tagged southwest of Valentine was killed the following year near Clearwater, a movement of about 137 miles. Another whitetail buck, tagged south of Valentine, was taken the next year west of Lewellen, having traveled about 125 miles.

Recoveries of 30 mule deer tagged in the Sand Hills showed lesser move ment than for whitetails, with an average of 16 miles. Greatest distance covered was by a buck tagged north of Newport which was killed south of Burwell 2Vi months later. It had traveled about 78 miles.

For short-term movement, one buck moved 48 miles in 17 days. Also, a doe tagged in July moved 23 miles in 16 days and was observed at least 11 times in that same location until she was shot in the fall of the following year.

In the better habitat of the Pine Ridge, movements are considerably less. Forty-five recoveries of mule deer showed an average travel of 5 miles, compared to 16 for the Sand Hills. As a better indication of stability, 30 of 45 mule deer (67 percent) in the Ridge were killed within two miles of the tag site, compared to only 1 of 30 in the Sand Hills taken so close to the area of capture.

Photo by Jon Cates

Photo by Jon Cates

As in all species, various mortality factors operate to control deer populations. Where numbers of deer remain relatively stable, then the sum of these losses must be equal to production. Hunting, accidents, predation, starvation and diseases all trim deer popula tions, keeping them in balance with available habitat and landowner tolerance.

With compulsory checking of the deer harvest, the portion of the legal hunting kill taken home is known with a high degree of accuracy. This is by far the largest mortality factor for which we have a figure. In 1974, about 1 7,400 deer were taken during the rifle and archery seasons.

Additional mortality caused by hunting is much harder to measure, and any estimates would be primarily speculation. Crippling loss during the hunting season is largely an unknown. In 1967, when we operated under a report card system, hunters were queried regarding numbers of deer which were crippled and lost. Reported rates were 5 percent of the legal kill for firearm hunters and 40 percent for archers. However, studies on other species have proved that hunters are reluctant to report crippling, and it is probable that both of these reported figures are considerably lower than actual.

On two surveys conducted in Nebraska, the number of legal animals lost in the field by gun hunting was about one-third of the legal harvest from these same areas. Conditions on these areas were somewhat abnormal, so that these possibly were higher than average. As a guess, crippling losses account for an addition of 15 to 20 percent of the legal harvest.

Illegal harvest takes two major forms, both of which are undoubtedly significant but nearly impossible to measure. Since much of our hunting has been under a basic bucks-only season, with only a portion of the hunters allowed to take either sex, does and fawns are often illegal for many hunters. A small minority of hunters may make little effort to identify, but will shoot first and hope for a legal deer. Honest mistakes can occur, but these are generally wasted.

Out-of-season hunting also occurs, and in some states could be equal to the legal harvest. Studies conducted in Maine and Idaho have indicated that only about one percent of big game violations are detected. It is doubtful that losses are that major in Nebraska, but we do have problems.

Highway collisions are the most frequent cause of accidental deer losses in Nebraska. During the past 5 years, reports have been received for over 1,300 deer each year which were lost because they or the motorist failed to yield right of way. Actual losses are undoubtedly greater, since some are not reported and some deer are not killed immediately but succumb later in areas where they are not found. Collisions occur most frequently where highways follow or intersect stream courses, and where deer cross from cover to adjacent feeding areas. Interstate 80, which follows the Platte River in large part, is a high kill area. Peak losses occur in October, November, May, and June, at which time deer movement is greatest.

Deer crossing signs are placed along highways in areas where heavier losses have occurred, in order to warn travelers of potential hazard. How ever, these are often ignored.

Mowing accidents account for some losses, particularly of small fawns. These fawns lay tight when the doe is absent, and frequent reports are received in which they are killed or have legs severed, necessitating their destruction.

Agriculture has been a primary factor in loss of suitable deer habitat in many areas. Irrigation has also caused more direct losses through concrete lined canals, which deer may enter but are unable to cross when much water is present. The most important in this respect is the Ainsworth Canal, which runs 53 miles from Merritt Reservoir to near Johnstown. Peak incidence here was in 1965, the first year of operation, when 136 deer were observed in the canal. Because of low water flows, most of these were removed alive. However, with major flows, few deer survive long enough to be taken out, and about 50 deer have died annually in this canal in recent years.

If more similar canals are constructed, they could become a major mortality factor, particularly in areas of high deer density. Escape structures have proven largely ineffective. The only suitable solution would be total exclusion, either by covering or by installing deer-proof fencing with periodic places for crossing.

Losses due to predation are prob ably the most difficult to measure. They are of scattered occurrence and normally the evidence disappears quickly. Most losses are of fawns, since they are the easiest to catch. Deer in poor condition are more susceptible to predation than healthy ones, but where travel is impeded such as in deep snow or on slick surfaces, all deer are more susceptible than normal. Because of relative abundance and distribution, coyotes are the most common predators of deer. Unlike some other states, we do not have a significant problem with feral

Age in Years White-tailed Deer Mule Deer Male Female Male Female y2 87 81 75 70 V/i 156 128 135 113 2Vi 192 137 173 122 V/2 217 144 201 128 — 213 126 4%+ 238 Average Live Weights of Nebraska Deer The weights of individual deer vary according to sex, age, species, physical conditions and area. At birth, females of both species average 5 1/2 pounds and males are about 2 pounds heavier. By fall the whitetail fawns will outweigh the mule deer by 15 percent. Contrary to popular belief, whitetails maintain this weight advantage in the older age classes as well. The heaviest mule deer recorded in Nebraska, though, would have weighed about 378 pounds on the hoof and the heaviest whitetail approximately 350 pounds

or uncontrolled dogs, although these may be important in local areas.

Because of the nature of Nebraska winters, with snow normally of minor depth and short duration, losses to starvation are rare. Some loss probably occurred in the Pine Ridge in the mid 50s due to excessive deer populations, but in more recent years no losses have been documented.

Malnutrition may indirectly cause losses, by making deer more susceptible to predation or through reduced fecundity of does-resorption of embryos, or fawns born in very weak condition with consequently poor survival. Again, this is of infrequent occurrence in Nebraska.

The only important disease affect ing deer in Nebraska is Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease (EHD). This is caused by a virus, and losses vary considerably by years. EHD is nearly specific to whitetails, although it does occur in and rarely causes losses of mule deer and antelope.

Major losses of whitetails, in which EHD was the probable cause, have occurred in Nebraska in at least 1954, 1955, 1964, and 1974. How ever, 1964 was the only year in which EHD was positively confirmed as the cause of death. Tests of blood samples in 1963 showed presence of EHD antibodies in 14of 53 whitetails, while 13 of 59 whitetails and 27 of 100 mule deer examined in 1968 were positive. Apparently EHD is not un common in most years, but only occasionally causes significant losses.

Brucellosis, which can be of major importance to cattlemen, is probably non-existent in Nebraska deer. Two samples in over two thousand were classed as suspect for brucellosis, but further check on one of these showed tularemia instead, and it is probable that the other case was tularemia also.

Samples from about 3,000 deer of both species were tested for several strains of leptospirosis, and less than 1 percent were positive for pomona. Since this disease occurs frequently in skunks, opossums, raccoons and dogs, the low incidence in deer would indicate that they are of negligible importance in transmission of leptospirosis.

Anaplasmosis, which is normally transmitted by biting insects, has not been tested for in Nebraska. It was found in about one percent of blood samples tested in Kansas, and it is not unlikely that a similar incidence occurs in Nebraska.

Wart-like growths, fibromas or papillomas, occur frequently on deer in Nebraska. These are caused by virus, and may be transferred by body contact to areas of cuts or scrapes, or by insects. These warts are generally unimportant except to appearance, although extreme cases could cause interference with respiration or vision. A mule deer fawn which was examined was probably nearly blind as a result of "warts" which covered one eye and most of the other. Such warts have no effect on edibility of venison.

Maintaining the Balance

PRIMARY OBJECTIVES in deer management in Nebraska are to provide the maximum amount of hunting recreation within the limits of the deer resource, and to maintain numbers of deer within the economic tolerance limits of landowners. Since about 97 percent of Nebraska is privately owned, the latter objective is obviously very important

In our big-game hunting seasons, we have operated under a system of management units, with permit limitations in each unit. Following major revision in 1961, boundaries of most units have remained stable, except for two cases of splitting and two cases of consolidation. Under bucks-only hunting there is little biological reason for permit limitations or unit boundaries, except when illegal kill during hunting season reaches significant proportions. These limitations are imposed primarily to distribute hunting pressure, to maintain a reasonable degree of quality by avoiding excessive hunter concentrations, and to main tain hunter numbers compatible with landowner tolerance to this form of disturbance. Hunting of antlerless deer, however, requires compara tively rigid controls to prevent undesirable overharvest. In 1974 we had 17 management units in Nebraska.

Normally, season recommendations are initially formulated by the Terrestrial Wildlife Division of the Game and Parks Commission. Meetings of most field personnel are then held in each of five districts, and comments and discussions are considered in formulating final recommendations. In addition to deer numbers, compatibility of population levels with agriculture receives primary consideration. Seasons are subsequently set by the seven commissioners at their April meeting. A hearing is provided at this meeting for input from the public.

In most previous seasons, all hunters in a unit operated under the same regulation, and harvest of antlerless deer, if allowed, was permitted throughout the season or on only the last day or two days of the season. Results from this system varied considerably. Since 1969, generally only a percentage of the permittees in a given unit, varying from 10 to 100 percent, have been permitted to take either sex. This method of regulating antlerless harvest is highly superior to the former system, as it permits prediction of antlerless harvest with considerably greater accuracy. This is the most important part of the regulations, since removal of does is the primary factor affecting population levels of succeed ing years.

The number of either-sex permits allotted is dependent on management goals. Where maximum increase is desired, a bucks-only season is the indicated course of action. A low number of either sex permits, such as 10 or 20 percent, permits some utilization of surplus does and allows at least limited control in problem areas. A greater proportion, such as 40 or 50 percent, would generally be aimed at herd stabilization. Allowing all permittees their choice of deer, adjusted properly with permit numbers, is generally geared for reducing deer populations.

In recent years, our firearm seasons have opened the second Saturday in November. This slightly precedes the peak of rut, and normally finds deer in good condition with increased activity on the part of bucks. A later opening would result in reduced table quality, as fat reserves are depleted during the mating season. Crop harvest varies with weather, but normally a sufficient amount of harvest has occurred to provide reasonable hunting opportunity.

Season length varied considerably the first few years, ranging from 7 to 21 days. From 1953 through 1961 it was of 5 days duration, and since that time has been for 9 days. This generally permits adequate hunting time, with two weekends making some allowance for bad weather. On a state wide basis, about 55 percent of the harvest occurs on opening weekend, with each succeeding day contribut ing from 4 to 9 percent of the total. Successful hunters have averaged about 21/2 days afield, while their less lucky counterparts have the dubious advantage of somewhat greater recreation.

Success rates are generally high, with overall success one of the highest in the nation. Statewide, success has ranged from a low of 43 percent in 1960 to a high of 80 percent in 1956. In 1974, success was 63 percent, ranging from 41 percent in one bucks only unit to 78 percent. During the past 10 years, firearm harvest has varied from about 12,000 to 17,000, while the take of adult bucks has ranged from approximately 9,000 to 11,000 during the same period.

Of much lesser importance to harvest, but providing a high proportion of recreation, are the archery seasons. These have generally started the third Saturday in September and run through the end of the year, exclusive of the period open to rifle hunting. From a token opening in 1955 with 173 permits and 7 deer taken, both permits and harvest generally increased, with about 9,000 permittees taking 1,500 deer in 1974. Only in the last two years has the archery harvest been equal to known losses from highway accidents.

Because of the problem of greater vulnerability and lower productivity of mule deer, mentioned elsewhere in this text, species hunting was tested on a trial basis. Species hunts have been used in other states and are generally considered workable, however there has been little effort to evaluate these seasons.

Photo by Karl MenzelThe Keya Paha Unit was selected for the test in 1971. All hunters in this unit were allowed to take bucks of either species, while a portion of the permittees could take antlerless white tails. No antlerless mule deer were permitted. Four seasons of this type have been held, with from 600 to 1,835 hunters (the numbers varying by year) allowed to take antlerless whitetails. If the season worked, there should have been an increase in the take of mule bucks in later years and a decrease or stabilization of whitetails. Numbers of mule bucks taken have not increased —245 were taken in 1971 and 216 in 1974. Whitetail numbers may have stabilized, with 444 bucks harvested in 1974 compared to 448 the first year. However, a considerably higher kill occurred the third year, with 523 whitetail bucks taken, and the lowered harvest of bucks of this species in 1974 was probably due primarily to more liberal regulations.

Although results are as yet inconclusive, it appears unlikely that differential species regulations provide an acceptable solution for attaining either objective —increasing mule deer, or reducing whitetails. The primary problem is in identification, with a large portion of the hunters either unable to identify species or unwilling to restrain until they are sure of a legal target.

The number of permits issued in each management unit is based on

Photo by Jon Cates

Photo by Jon Cates

population trends rather than actual estimates of the number of deer. The latter is normally practical only for small areas, and estimates for larger areas, such as county, management unit or statewide, could normally be best considered educated guesses.

In areas of low population density, even accurate trend information is difficult to obtain. Aerial counts or spotlighting surveys are generally of necessity limited to more favorable areas, and trends there do not always follow the actual population levels. Both of these methods are currently used in Nebraska. However, snow conditions are only occasionally favorable for aerial counts, and the duration of snow has an effect on the numbers of deer along stream courses. Spotlighting or other direct counts are of primary value in indicating variations in production, by doe-fawn ratios, rather than providing an index to total numbers.

Data obtained on established routes, from random observations of deer and from examination of road-killed does, have shown only comparatively minor variations in deer production. A common fallacy regarding low fawn levels because of relatively heavy buck harvest has been adequately disproven, but this misconception continues. The "dry doe" theory is most commonly related to mule deer, but few of the proponents take into account that mule deer seldom breed as fawns. Since long yearlings are the most common of the older age classes in the fall, obviously there will be a fair proportion of "dry does." Further more, accurate designation of fawns is not possible in the field in November, and even after the animal is bagged, about half of the hunters are unaware that they took a fawn.

Pellet counts have been highly variable in Nebraska and have shown little relationship to other population indices, even in areas of high deer densities. Surveys of browse usage can be important in showing condition of deer range, but where agricultural crops are an important part of the diet, depredations would be common before browse deterioration occurs. Road kills, which areenumerated, are sometimes of value in indicating population trends where variations in traffic, speeds, and new construction are taken into account.

The most important information for measuring population levels in Nebraska is that obtained from harvest surveys. In all years, except 1967, hunters have been required to take their deer to a compulsory check station, where the kill is validated and important data obtained. Considering the widespread distribution of the harvest and comparative abundance of roads, this is the only practical method for examining large numbers of deer.

Data of primary importance are total harvest, hunter success, and species, sex and age composition. In addition to trends, these data also permit calculation of at least minimum population estimates. Since these data are obtained after the fact, basically they show what the season should have been, rather than what next year's season should be. However, the harvest is the only practical method for obtaining sufficient information in areas of lower populations, and it has generally been sufficient for adequate harvest management.

Many factors are taken into account before the harvest levels are set in a management unit. Landowner tolerance may be the most significant but carrying capacity is also considered. Carrying capacity is the number of animals of a given species that can be maintained in a particular area. This capacity is variable, dependent upon natural and man-made changes in the habitat. Where densities of certain animals, such as big game or livestock, temporarily exceed this capacity, it is usually at detriment to the habitat and with a consequent reduction in future carrying capacity.

In large parts of the ranges of mule and white-tailed deer, food is the chief limiting factor which determines carrying capacity. In Nebraska, the mere presence or abundance of food is generally not in itself limiting. How ever, since agricultural crops constitute anywhere from a small to major portion of the deer diet, the basic problem is how much use of these crops can be tolerated without detriment to agricultural economics and landowner tolerance.

Landowner tolerance varies considerably. At one extreme, an indi vidual complained about trampling damage from two animals on a quarter-section of alfalfa. At the other end, herds in excess of one or two hundred are hosted without comment.

Regardless of the level of tolerance, deer are capable of causing real dam age to property. This is not often the case on growing crops, such as alfalfa or wheat, but problems may arise from trampling where the land is marginally suited to farming. More serious damage can occur as crops near maturity or growth has terminated, such as in eared corn or alfalfa seed, or on harvested corn or alfalfa. Where such damage occurs, control is necessary. In such instances, damage can best be prevented by regular hunting seasons.

In spite of harvest levels, major problems may occur during winters of exceptional severity. The winter of 1968-69, when considerable snow was on the ground for several months over much of Nebraska, resulted in as many complaints as during 10 normal years combined.

Some problems are aggravated by stacking or piling hay or grain in areas frequented by deer, and could bf alleviated by storing feed in areas less susceptible to damage. Fencing is costly, but this is often the most practical method to reduce or prevent damage. Scare devices and repellents can be effective, but generally provide only temporary relief. In many cases, temporary is enough, since a change in weather or snow cover may remove the problem.

The presence of two species of deer in Nebraska is a blessing, since even in areas where ranges overlap the habitats are not entirely similar, and it is possible to have more deer of both species than of either species by itself. However, this is not an unmixed blessing, since mule deer are con siderably more vulnerable to hunting. For deer tagged in the Sand Hills, first year hunting season recoveries were three times as great for mule deer as for whitetails. Where the harvest is intended to be directed at control of problems, mule deer may wind up providing a disproportionately heavy part of the harvest.

The pattern of relative species abundance has changed markedly in favor of whitetails during recent years. Using counties as the basic unit, about 14,000 square miles of Nebraska, or 18 percent of the state area, shifted from predominantly mule deer to predominantly whitetails between 1961 and 1973. However, the rapidity of change has decreased considerably in the last few years. Since whitetails are more productive, we can take a greater proportionate harvest of this species without reducing populations, so this change is far from all bad. However, mule deer have been re duced below desirable levels in areas.

The greatest problem in the future of deer is habitat destruction. The removal of timber adjacent to water courses, and complete removal of shelterbelts is very evident in many areas. Introduction of overhead irrigation and increased crop and land values have contributed much to the destruction of this woody cover. Additional stream channelization, which would permit farming to the river bank, and construction of dams with consequent flooding of good timber areas, could result in further significant losses of habitat and deer. A certain amount of cover is necessary if deer are to survive, and if the current rate of habitat loss continues, deer numbers will decline.

History of Nebraska's Deer Harvest At the turn of the century, fewer than 100 deer were believed to be in Nebraska. By 1940 the herd had grown to only 3,000 animals. By 1945, though, the number of deer had increased enough to allow a limited season. Today, Nebraska's estimated 100,000 deer are hunted in every county

Techniques for Nebraska Deer

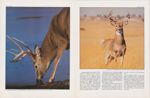

Photo by Bob GrierTHE MOST VALUABLE asset of any deer hunter is an ability to "think deer". A few gunners get reputations of being lucky, and chance probably plays a role in some cases. But in many instances, these hunters are "lucky" simply because they consciously or subconsciously "think deer" when in the field, and this puts them in the right place at the right time.

A hunter must learn what the deer needs and wants in day-to-day life; seasonal factors that drive him; and the places he goes to meet these wants and needs.

These needs are food, a place to bed during the day and a place to hide from intruders. They are the same for whitetails and mulies, although each species might seek them in different kinds of terrain.

Weather conditions and time of year might also influence deer activities. Different foods might come into season, crop harvests and falling leaves might remove protective cover or preferred foods, and varying temperatures and winds might influence the deer's selection of a bed. The rut, or fall breeding season, and heavy hunting pressure also influence the deer's daily routine, often scrambling the pattern.

After inspecting a few deer beds, the hunter will see that they pick warm, sunny spots on a cool day and shady beds when it's warm. They also like to have the wind behind them to bring scent and sound of an intruder, and a good view in front to see trouble approaching.

The comfort and safety factors apply equally to whitetails and mule deer, but the two species generally bed in different terrain. The mule deer is often bedded at the upper end of a canyon, lying behind a light screen of buck brush or weeds, just below the crest of the ridge. Usually the wind is such that it will carry him news of an intruder approaching from behind, and he can easily see a good distance down the canyon.

The whitetail prefers a spot in heavy cover. He might trade a heavy thicket for a good view and depend on the crackling and crunching of an enemy moving through the tangle to warn him. Other approaches would most likely be covered by the wind.

The hunter might note other things just from inspecting a few deer beds. An area with three beds, one just barely larger than the others, is very likely a doe with her two nearly grown fawns. A large, solitary bed pressed into the grass some distance away from a spot used by a large group of deer is probably that of a buck.

Any hunter who is at least half awake when moving through deer country should notice other deer sign. Droppings, for instance, tell a hunter with certainty that deer have been in the area. And, if he is observant and applies a little common sense, these little heaps of dark, slightly elongated pellets will tell him considerably more.

If, for instance, they still appear shiny and moist on the outside, they are probably no more than an hour or two olck Droppings a couple of hours old have a dull appearance, but are still soft when prodded with the toe of a boot. Generally, those older than a day are rather crumbly, and at several days, they begin to get downright hard.

It might seem that a hunter would be interested only in the freshest sign, but that's not necessarily so. If a particular area has some fresh droppings, some a day or so old and others even older, it means that deer use the area quite regularly. However, nothing but day-old droppings in one area, for in stance, probably means that a few deer came through, but that particular spot is not part of any deer's daily routine.

Other sign in deer country is more specific, tattling on the presence of a buck. Nearly every hunter would like to take a brawny trophy animal, and a good share of deer permits in Ne braska are valid for bucks only.

One sure sign of a buck is a "rub" — a branch or sapling stripped of its bark by a buck knocking the velvet from his antlers. Later in the fall, as the rut approaches, fresh sign of this antler work may appear on larger, harder trees, as restless bucks shape up their fighting skills.

An even better sign of a buck, especially in whitetail country, is an active "scrape." This is where a buck has pawed the leaves and grass away, exposing a patch of bare earth from one to three feet in diameter. He generously applies his scent and tracks in the scrape, which serves as a signal to does that he is in the area and available, and warns other bucks that this is his territory and they'd better stay out, or else.

A buck fully caught up in the fever of the rut may have several scrapes which he checks frequently, or he may post just one and stay nearby. Whichever the case, the scrape that is being renewed and maintained is a sure sign that a buck will be along sooner or later, and it merits careful consideration.

Of all the sign a hunter is likely to come across, deer tracks are the most obvious and are also the most misused and misunderstood by the novice. A lot of greenhorn deer hunters are likely to latch onto the first set of tracks they find and spend the rest of the day following them, almost invariably without seeing the deer.

Tracks are a valuable sign to the hunter, chiefly as an indication of the frequency and direction of travel. They might also give an indication of the size of deer using an area. Generally, they provide a lot of the same information as do droppings.

Some hunters claim they can distinguish tracks of bucks from those of does, but other experienced hunters discount this. Generally, tracks of large does and bucks look identical, although a hunter tracking a deer might surmise he's on the trail of a buck if it is travelling alone and stick ing to more secretive haunts.

Following a set of tracks in hopes of getting a shot at the critter making them is an iffy game, and is a tactic mastered only by a few specialists. Most hunters follow a trail too slowly or make too much noise to be success ful. And, a lot of hunters cannot distinguish a really fresh track, and thus may take up on a trail half a day old or more.

Most hunters following deer tracks pay way too much attention to the impressions themselves and almost forget to look for the critter standing in the tracks. Experienced trackers look for the most distant visible sign, giving it just a glance while keeping their eyes on the cover ahead, ready for a shot. They also look behind, be cause deer often double back on their trail to see if they are being pursued.

About the only time most hunters will need to track a deer is after they have taken a shot at one. If the deer

When it comes to hunting

deer, experience is the best

teacher. In most

situations success belongs

to hunters that can

patiently wait out a deer

When it comes to hunting

deer, experience is the best

teacher. In most

situations success belongs

to hunters that can

patiently wait out a deer

doesn't go down, the hunter should check where the deer was standing when the shot was fired, looking for blood, hair or other signs of a hit. If none is apparent, he should take up the track for a few hundred yards, looking for blood on the ground, bushes and trees the deer may have brushed against, or for signs of staggering, limping or other evidence of a hit.

After a season or two of apprentice ship, a deer hunter should begin to get an idea of what he's doing. He will probably know what deer eat in the fall—the weeds, corn, tree leaves and buck brush. He'll probably be able to pick out likely bedding areas and escape routes. And, he'll have an idea how the deer uses his excellent nose and radar-like ears to pick up signs of danger.

The hunter's problem now is to put all of this together and come up with a workable strategy for the particular piece of ground in front of him. If he's hunted with good sportsmen in the past, he's come to appreciate the challenge of finding sign, figuring out the deer's habits and stalking him on foot. Even if he doesn't bag a buck, the experience of the hunt is reward enough.

Sporting methods of hunting deer vary according to the terrain involved. In heavily timbered areas like those along the Missouri River or other major waterways, direction of deer move ment at feeding time is fairly predictable. The hunter will be dealing with whitetails, who bed in the heavy cover during the day and move toward corn fields and weed patches on adjacent farmlands to feed as dark approaches.

If hunting pressure has spooked them away from the fields, deer will be content to munch on tree leaves, a large variety of shrubs, chokecherry bushes and even pine needles. But even then, they will have to head for the edge of the big patches of timber.

Stands of mature trees offer little undergrowth for deer to eat, but there is sufficient food along the edges, around clearings, and in the new growth in areas once cleared by fire, logging or clearing.

One good tactic would be to take a position along the edge of the timber or inside the timber near a trail lead ing from bedding to feeding areas. Chances of ambushing a buck along one of these routes are good around dawn and dusk.

During the rest of the day, a hunter might spend his time still hunting, a tactic where he walks ever so slowly and quietly through deer cover. A good still hunter will spend a lot more time using his eyes and ears than his feet, perhaps taking only one or two steps, then carefully scanning the woods for a minute or more.

Two or three hunters can sometimes team up in cases like this, and can have good success. Some teams have done well with one posted on an es cape route while another still hunts in the area. Sometimes, the hunter on the move gets the shot, but more often, the gunner on the stand gets the op portunity while the buck's attention is focused on flanking the moving hunter.