NEBRASKAland

March 1975

NEBRASKAland

VOL. 53 / NO. 3 / MARCH 1975 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Fifty cents per copy. Subscription rates $5 for one year, $9 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. commission Chairman: Jack D. Obbink, Lincoln Southeast District (402) 488-3862 Vice Chairman: Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 2nd Vice Chairman: Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-Central District, (308) 745-1694 Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-central District, (308) 452-3800 James W. McNair, Imperial Southwest District, (308) 882-4425 Director: Willard R. Barbee Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, jr. Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: Jon Farrar Greg Beaumont, Ken Bouc, Steve O'Hare Contributing Editors: Bob Grier Faye Musil, Tim Hergenrader, Roland Hoffmann Layout Design: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1975. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska Contents FEATURES BOB WHITE HOTSPOT A SPORT YOU CAN LIVE WITH 10 PRAIRIE STEAMBOATS 12 IN TOUCH WITH THE WORLD CRANE RIVER 14 A SPECIAL SECTION ON THE LIFE AND TIMES OF THE SANDHILL CRANE IN NEBRASKA 18 CAMPING WITH THE CRANES 36 PRAIRIE LIFE/NATIVE HUNTER NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA/SMALL-MOUTHED BASS 38 50 DEPARTMENTS SPEAK UP 4 TRADING POST 49 COVER: The Canada goose is a handsome and welcome traveler through Nebraska, but some also spend the winter here, apparently finding the season temperatures within their comfort range. Photo by Bill McClurg. OPPOSITE: Attractive even though no longer living, an American elm stands as a monument to the many trees and shelterbelts being sacrificed across the state. Photo by Bob Grier.

Speak up

What Scenery!Sir / I have been a subscriber of your very fine magazine since 1970 (my last trip to the capitol in Lincoln) and have enjoyed reading it very much.

Although a former Nebraskan (north east) I have been a resident of Hawaii since 1940 except for a period from 1945 to 1948 when we lived in Lyons, Nebraska.

I was especially taken with your August 1974 issue, and wonder if the picture on page 20 of the Pine Ridge is available. I would like to get a large one suitable for framing. I had no idea that Nebraska had such scenery! I might add that the magazine has acquainted me with many parts of the state I've never seen.

Merle Arnold, Jr. Kailua, HawaiiNegatives and transparencies appearing in NEBRASKAland may be borrowed at no cost to have prints made. We have no facilities for making color prints, so it must be done by one of the commercial processors. (Editor)

On Deer SavvySir/ Have just completed reading the article on deer hunting by Ken Bouc. (November '74) and can certainly tell he has a lot of knowledge on deer. If all deer hunters would read then use this advice, they would take a deer home. I'm not a newcomer to deer hunting, as I have tagged 7 archery deer in Nebraska in the last 10 years.

Ray Vondracek Omaha, Nebr.As with all forms of hunting, it always helps to know as much as possible about the species being pursued. And, it makes the hunter more safe, appreciative, and certainly enhances enjoyment. After all, it is more important that people have totally enjoyable and memorable hunts than bringing home game, but success doesn't hurt. (Editor)

Big PlansSir / In reference to "Wapiti Wilderness Project" ad in January NEBRASKAland: "Our plan calls for a minimum of 64,000 acres to be set aside as a primitive reserve of grasslands, timber and waterways... area without roads and other man-made structures."

64,000 acres —people live there! The creation of this wilderness would mean the displacing of some 600 farm families! Considering that there are but few farms for sale or rent, where would these families go?

The idea of a wilderness featuring the tall, native grasses, birds and animals is commendable. But need it encompass 64,000 acres? 1,000 acres would be way plenty. Let's be reasonable!

Ex-Nebraskan Agatha Walter Portland, Ore.Several sites are under consideration by the Wapiti project, but none of them would displace many people, and of course all would be strictly voluntary. The 64,000 acres was apparently decided upon as necessary to incorporate all the many features planned for the area. An area is not wilderness if you can see roads and telephone poles, and if there is not sufficient land for animals to feel unconfined. Interested persons might want to write the Wapiti Wilderness Project, 10914 Prairie Hills Dr., Omaha, Nebr. 68144 for additional information. (Editor)

Pickle Anyone?Sir / I would like to share a recipe for pickled fish. My husband does a lot of fishing, and I searched for recipes but all I could find was one for salted herring. I've since done a lot of testing, and would like to share my results with NEBRASKAland readers.

Crappies, bass or perch are very good. We clean them all with an electric knife, then take the rib bones out with a boning knife afterwards. Place the fish in salt water and let them stand overnight. Drain and rinse. Dry the fish pieces and place on a cookie sheet in an oven preheated to 200-250. Bake 30 minutes. Remove fish carefully with a spatula and place in crock or plastic bowl, put a layer of fish, a few onion slices and layer of fish and more onions until the bowl is full.

Boil the following and pour over fish:

2 cups red wine vinegar 1 cup water 3 tablespoons white sugar 3 tablespoons brown sugar 6 bay leaves 2 tablespoons mustard seed 2 tablespoons whole black peppers 1 tablespoon whole allspiceMake sufficient amount to cover fish, and they will be ready in just a few days. I've had a lot of calls and compliments on fish fixed like this, soothersvouch for them.

Mrs. Gus Steppat Valentine, Nebr. Save the BirdsSir / I enjoy all the lovely pictures in each month's issue, but I can't agree with your promotion in all your hunting articles. The terrible slaughter of all our pheasants and prairie chickens is sickening. I can't buy the big excuse that they have to be reduced in number for their own good. It's just an excuse to absolve any guilt the hunters have.

Now I've had my say and know there will be letters from the greedy hunters galore. Anyway, I want to say that when our grandchildren need any pictures for school we bring out our old copies. We needed bird pictures. We found all the game birds many times, but never a robin. Now a robin is a beautiful bird —would make a pretty picture, is also very numerous in Nebraska. How about a couple? Maybe some other kinds too. Birds can be enjoyed other ways besides eaten or exploited. Much money is spent for bird seed.

Mrs. R. Foster Stuart, NebraskaI hope that many hunters take up the gauntlet so openly cast down by your charge. You seem to consider hunters a form of mafia —waiting like hired killers to do in the innocent and sweet wildlife merely for kicks. Why not pick on the major killers, those who poison the countryside and destroy wildlife and bird habitat? They wipe out the birds' future, rather than harvest the annual surplus. Hunters are by and large honest, clean-cut people enjoying a legitimate, time honored sport. Only under certain circumstances is hunting "good" for the game, but modern management sees to it that there is no harm. It is just good common sense, just like picking fruit or digging carrots, to harvest each season's "crop". For no matter what you think, those birds are going to die —whether alone by nature's hand, unseen by "friends of animals", or by the hunter's hand, after which they are utilized as food. So be it, ordains Mother Nature. If feeding a few songbirds satisfies your conscience, that is fine. But, don't attack those who lawfully and logically and financially are doing more. (Editor)

BOBWHITE HOTSPOT

Returning to favored haunts, late-season quail seekers draw blank. Then, pair of treed bobs flush and cold-weather hunters get hot

Photographs by Bill McClurgWHERE DID they go?" said a surprised and disillusioned Don Kimbrough, Jr. "I've hunted quail here the past 10 years and I always find two or three coveys along this draw."

It had looked promising, all right, but something was missing, and for Don, myself and Tuffy, Don's two year-old black Labrador, that some thing was quail.

Don, an old school buddy who farms near Geneva, and I were hunting south of Beatrice, hoping to bag a few birds to cook with a Christmas turkey. He grew up on a farm south of Geneva in an area long famous for its pheasant hunting, but the osage lined fencerows provided only a sample of quail. So Don, his father and brothers try to make at least one hunt ing trip a year for the little feathered bombshells.

This time, though, I was filling in for Don's relatives after they couldn't make it. We were hoping Tuffy would help take up some of the slack. His nose is an integral part of a quail hunt with Don, as I had learned in several outings with them earlier in the season. Don's fetish for quail hunting is at least equaled by the dog's enthusiasm for finding them.

For mid December, the weather was pleasantly mild with a forecast high in the 50s. Too dry for good dog work, we thought, but before the day was through Tuffy was destined to prove us wrong.

The cover in the draw was heavy enough to hide a good covey, and it did, or they weren't there. A lack of interest by the dog confirmed our be lief that the birds weren't there. We agreed that a shortage of food was the limiting factor for this area, as the only available grain was a recently plowed milo field next to the draw.

It was close to noon when we final ly found a spot that looked so birdy we knew they had to be in there. A maze of plum thickets, honey locust and sumac, surrounded by milo stubble, beckoned to us, but a check with a neighbor across the road proved futile when he said the land was owned by a farmer who lived some 20 miles distant.

After listening to our pitiful woes about the scarcity of quail, he offered to let us hunt a draw in back of his buildings. He told us he had seen a covey there, but not in at least a month.

With a little skepticism from our previous morning's experience, we thanked him and headed toward the draw. From the road it hadn't looked too promising, but at least we would get some exercise.

After walking over a hill behind the farmhouse, it soon became apparent there was considerably more cover than could be seen from the road. A huge plum thicket about 20 yards wide lay before us, and an enthused Don hollered across the draw that this was the place. Tuffy was working every inch of the big thicket, and every second we expected a covey to explode But nothing happened.

Tuffy had covered the whole thicket at least twice and we just knew the birds were around, but where were they?

Almost on cue, a pair burst into the air from a large cedar tree in the pasture to my left.

Too far away for a good shot, I marked them down near another thicket and yelled over to Don. Just then the rest of the covey flushed from the other side of the tree. These too were out of range, and I tried to mark down as many of them as I could.

"How many were there?" wheezed Don as he scrambled up the hill where I was standing.

"Maybe 25," I told him. "About a dozen flew down the creek bottom, some went toward a thicket on the left and the rest just disappeared."

"Well, let's get the ones along the bottom first and then swing around and get the others on the way back," he suggested. I agreed, and Tuffy's wildly swinging tail told us the decision was unanimous.

"Careful," I warned as we approached the place. "They should be close now." Tuffy was tearing up the grass as he rooted for the scent of a quail. Then he lunged forward as a bird buzzed off. Reacting quickly, I dumped it about 30 yards ahead.

Tuffy was still working intently and flushed another in front of Don. His shot only punctured the air as the quail ducked around a big cotton

wood and crossed in front of me. I swung the barrel of my 12-gauge pump and dropped it cleanly near the first. Then a third got up, and I folded that one too.

"Boy, you're really hot today/' Don said. I felt pretty smug beating him at his own game, because it's usually the other way around when we hunt together. My smugness must have turned into overconfidence though, because two more birds got up on my side and I missed them both.

We worked the rest of the drainage without seeing any more quail. "Let's pick up those stragglers on the left," I suggested, so we headed toward a small thicket and some more cedars where I had watched a few land.

"Just look at all this cover," Don said, referring to the milo and corn stubble fields. "Back home you won't find this kind of habitat. Most people around my place have done their fall plowing by now, and all the food and cover is gone. Then, to top it off, they tear out the osage orange fencerows and burn their road ditches."

We were approaching the thicket, and Tuffy had a quail on his mind as he zigzagged through the pasture.

A single took off right at Don's feet, but this time he managed to drop it with one shot. Tuffy was retrieving it when another got up. I missed it cleanly, but Don's shot knocked feathers loose and I watched it land about a hundred yards ahead on my side.

"I think you hit him pretty good," I told Don. "Let's see if Tuffy can find him."

The bird had landed in a strip of bluestem about three feet wide, and I knew it would hold tight in the tall grass. Tuffy smelled the bird when he was still about five yards away and he worked the grass back and forth trying to find the exact spot where the bird was hiding. Twice he went past the bird but the third time the quail took off to my left and one shot put him down for the count.

The hedgerow ahead attracted our attention, and it didn't take long to figure out that birds were here, too.

Just after Don crossed the fence, another large covey took off ahead. Two shots from Don's 20-gauge produced his second quail of the day. The covey had flushed and flown on his side of the grove, but he lost sight of them as they flew over the hill.

"They should have landed just ahead," Don hollered as we walked over the hill. A single popped up a head of the dog and Don's shot tumbled it. The remainder of the walk produced only exercise, as the rest of the covey had disappeared some where.

Retracing our route, we turned left and followed yet another fencerow. This one looked more like pheasant cover, so I replaced my No. Wis with a few loads of No. 5 shot.

Something had spooked the birds though, because they flushed wild about 50 yards ahead. Another hunter, a coyote, ran out of the weed patch on the other side, so we knew it wasn't any use for us to hunt the area he had already covered.

A grassy draw on the right cut back down to a thicket and then to the car, so it seemed a good direction to go. Tuffy was getting thirsty, so a patch of snow on the shady side of a tree attracted his attention.

It seemed like a good time for us all to take a rest. As he sat down on a log, Don mentioned that the birds appeared to be a little small for this time of year. We agreed that the birds could stand a lot more hunting pressure to reduce the competition for food and cover.

Southeast Nebraska is a perennial hotspot for quail. A combination of habitat and usually milder winters are two of the primary reasons for their abundance. In most years, survival of newly hatched quail to reproductive age the following year ranges around 20 percent. Thus, about 80 percent mortality occurs even if they are not hunted, so the population may actually benefit if it is reduced before going into the stress of winter.

Tuffy had rested more quickly than we and was ready to go again, so we reluctantly got up and headed back toward the car.

A small plum thicket drew the dog's interest, but we were too busy talking when a pair of quail took off. Since it was close to where the second covey had been, we figured they were part of the broken-up group, Tuffy proved us wrong when another covey took off in front of Don and swung around in front of me.

I heard three shots from Don's side as I swung on the covey. Picking a target from the bunch wasn't easy, as the birds buzzed all around me. Almost too late, I recovered in time to dump one in a fencerow.

Don had dropped two from the covey. Tuffy was retrieving one of his birds as I came around the brush and Don was looking for the other.

"The bird looked like it was crippled," said Don as he kicked around in the tall bluestem grass.

Sure enough, it buzzed up in front of Don, flew a couple of yards and landed again. This time Tuffy spotted it and was hot on its trail.

"There it goes," said a flustered Don as the bird ran through an open ing under a large cedar tree. Tuffy followed it right to the tree's edge and then lost the scent. Finding it again, he worked back and forth. This was his bird and he was not to be denied.

Then he stopped, reared back and lunged into the grass. When he came up, the quail was in his mouth.

"If this is all he did, he would be worth his weight in gold," said his proud owner.

The limit was six birds apiece, and we both had five. As the sun crept near the horizon, we headed back to the car. We had all the birds we needed.

"Can you believe it?" Don mused. "Three coveys and at least 70 or 80 birds on about 100 acres of land."

"The key to more birds then," I offered, "is habitat. Where you find adequate food and cover, you'll find quail and other wildlife."

"I'll buy that," he replied.

Tuffy was still going strong as we entered a draw leading up to the car. Hot on the trail of something, Don hollered a warning just as the dog flushed a rooster pheasant. My gun was empty but Don was ready and his shot rolled the bird. Tuffy had it and was waiting patiently by the car as we cleared the top of the draw.

"How about that?" Don said as he held the rooster up against the setting sun.

"Beautiful," was all I could say.

A SPORT YOU CAN LIVE WITH

Recreation accidents and can turn fun-filled outings into tragic nightmares. Before mishaps is time to learn to avoid them. So, Game and Parks Commission is initiating a boating safety course aimed at curbing mistakes

DEATH CAN COME in many many forms, and it is not pleasant under any circumstances, but when it results from a recreational pastime, through an act of carelessness or ignorance, it is especially distressing.

Few people like to contemplate the unpleasant aspects of a disaster, yet many people, far too many, must face them every year. Boating accidents or mishaps are often fatal, and for this reason, the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission would like all Nebraskans who engage in boating in any form, to start thinking of it with an attitude based on sound knowledge of their vessel, equipment, methods to make that boat safe and efficient, and laws governing its use.

Before a tragic accident occurs is the time to consider what can happen if any of that knowledge is neglected. To this end, the Information and Education Division has developed a course in Boating Safety to be used in addition to the efforts already being made to lower boating and boat related accidents and fatalities in Nebraska.

As part of a comprehensive plan for statewide boating safety, this course was developed using funds from the Federal Boating Safety Act of 1971. In previous years, safety programs were offered to any interested group by the Game and Parks Commission in cooperation with the American Red Cross and the Lincoln Parks and Recreation Department. Safety material was presented by conservation officers, Red Cross Personnel, the Coast Guard Auxiliary, Lincoln Parks and Recreation representatives, citizens desiring to act as instructors, and Information and Education staffers through lectures, films, demonstrations and written materials. In a program like that, however, many persons and organizations put forth individualized efforts, which tended 10 NEBRASKAland to create a state of disorganization, or at best, very random and limited exposure.

The program developed by Information and Education differs from previous efforts in that the main thrust of instruction is intended to be through school systems, public and private, and is designed for students at the junior and senior high school levels. It is believed a more thorough exposure to boaters of the future will thus be attained, and that the teaching facilities available in schools will be of a higher caliber than those arranged for "one-shot" sessions. By giving this instruction to students, they are exposed to sound ideas and principles when they are old enough to learn how to boat properly while young enough to form or change their basic attitudes. A learning situation will be more effective if it exists among students and teachers who know each other in a familiar setting. It is hoped that teachers will arrange for and use the examples and activities suggested in the program, as actual experience is the best teacher known.

To make this program available to teachers for use as a form of curriculum enrichment, the Game and Parks Commission is working in cooperation with the State Department of Education. The course comes in self-contained packets including all materials needed for the complete program. Three films produced by the Game and Parks Commission, in structor's guides, student materials and certificates, are provided free of charge with additional written materials available upon request.

Anyone who boats could tell you how popularity of this activity has in creased in the very recent past. A few facts compiled by the Game and Parks Commission may help portray this in a graphic way. They will also help picture what is projected to happen to boating in the next 20 years or so. It has been found that the boats typically used by family groups for weekend and summer recreation (Class II and III) comprised over 80% of all boats registered in the state in 1971. When you learn that roughly half of those were registered in Omaha and Lincoln alone, you can see how the de mand for boating opportunities has become somewhat lopsided. A study concluded that there is presently a deficiency of 22,000 acres of water suitable for boating in the areas of Omaha and Lincoln, and that this deficiency will increase to 33,000 acres about 1990. Information that further depicts the trend in boating comes from surveying individual power boat users to estimate the actual number of separate outings in which boats were used. Such a survey of power boating occasions, coupled with population, age, income and other recreation trends, leads to a prediction that power boating occasions will increase almost 45% in the forecasting period. This, combined with expectations of little increase in supply of boating facilities, is a distressing situation. It simply boils down to where demand for boating opportunities will go up while the supply remains essentially stable, resulting in crowded, unsafe operating conditions in many areas.

A number of ways of coping with this situation are being proposed, not the least of which is an educational process to make boaters knowledge able on how to safely conduct them selves on the water. One other proposal has been to create new boating areas; a solution which has been known to backfire, as that tends to create more demand in itself. Other proposals under consideration involve zoning or restricting bodies of water to specific uses, and to find ways of distributing use from the peak days of Saturday, Sunday and holidays.

The education process that will do the most good, will be the one that fosters knowledge of the entire situation concerning boating as a recrea tional pastime. Boaters need to know that with increased use, facilities that are now taken for granted will have to be treated with great care. Boat ramps, docks, picnic areas, toilets and water systems will be positive aspects of water-related experiences only if people are sensible in their use of these facilities, and then are willing to compensate for the careless person who doesn't. Consideration by the power boater for lower impact, slower moving boats such as canoes and sailboats must increase, or conflicts similar to those between backpackers and trail bike riders will arise, necessitating management decisions regarding "non-compatible" forms of recreation.

Educational tools in related fields of safety education have proven effective in reducing accidents, fatalities, and all sorts of just plain bad times. A case in point is the Hunter Safety Program developed by the NRA which was subsequently adopted by many state agencies. Hunter accidents have decreased, and the awareness needed for safe gun handling has in creased to the point where accidents are truly few and far between.

A program of this type can be a success, or it can be a "real" success. It becomes a "real" success when those involved put what they learned into constant use, both on the action and attitude levels. When this comes about, boating can become an even safer and more enjoyable activity than now, even in the face of expanding demand.

Any teacher interested in using the Boating Safety Course should contact the Education Section, Nebraska Game and Parks Commis sion, P.O. Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503.

PRAIRIE STEAMBOATS

A Legend Reexamined

IN THE SPRING of 1819, word was passed from Indian camp to Indian camp on the banks of the Missouri River, that a strange craft, "a fire canoe", was belching smoke and spitting sparks as it slowly paddled up the river.

Quite possibly some well traveled Oto or Omaha had ridden a keelboat or mackinaw, packed to its gunwhales with fur pelts; or even the swift bull boat—a buffalo hide lashed taut over willow poles —down the river to St. Louis and had seen steamboats. But this new craft was different; this truly was a fiery animal.

The phenomena was the Western Engineer, a government-constructed vessel for exploration. It was the first steamboat up the Missouri in Nebraska Territory, and it got as far as Fort Lisa, a trading post above the Council Bluff. The boat was unique in construction in that it had a pipe from its boilers that allowed steam to emit from a fiery red mouth painted on its black bow. The sight was enough to frighten the bravest of the braves, which is probably what the government had in mind.

Officials thought that when the burly, brawling Mississippi was conquered by steamboat, all traffic west would be overland. They did not reckon with the lucrative mountain fur trade and the adventurous river boat men.

It was not long after the government boat plied its course up the Missouri that the American Fur Company built a steamboat to climb its way up the river. "Clipnb" is no mere figure of speech, as the early boats literally had to perform some strange maneuvers to cross the shallow, sandbar infested river.

Various techniques were used by enterprising pilots. One method was to attach a line from the grounded steamer to a buried log, called a "deadman," up ahead on the bank and then pull itself over the bar with a steam-powered deck winch. An other operation was to set long poles at a slight angle in the sand ahead of the boat. A line was placed from each pole to the capstan and, as the line was taken up, the boat was lifted and lurched forward. This gave the appear ance of a series of leaps, from which it drew its name, "grasshoppering".

On some parts of the Nebraska coastline, such as near the mouth of the Niobrara, these methods were not feasible due to the harder bottoms. Here the grounded steamboat was lightened by unloading the cargo into small boats and hauling it ahead until the vessel would float free. The cargo would then be laboriously replaced aboard.

In the early days, the fur company would send boats, one per season, up the Missouri. This was done in the spring of the year to catch the river in full flow from winter thaws. By 1850, steamboat traffic had become considerably heavier. How many boats plied their trade on the Nebraska coastline is difficult to determine exactly, but a Corps of Engineers report showed that between the years 1830 and 1902, 53 were sunk within a stone's throw of the Nebraska shore. The Bertrand, because of the recency of its salvage, may be the most prominent, yet there were others of most novel interest.

The Louisville was sunk in 1858. Sixteen years later a corporation was formed to salvage its cargo of 16 barrels of whiskey and one wagon. An Omaha newspaper reported that it was the wagon that the corporation was after.

In 1876 the Damsel! hit a snag (floating log) off the sleepy little river town of Decatur. The steamer had as its passengers Don Rice, a great if fading circus star, one lion and a trick white horse. The good people of Decatur heeded the Damsel! in distress and saved the white horse. To show his appreciation, the showman donated the steamer's bell for the village community church.

Once the challenge of the Missouri was overcome, if the ever-changing river ever could be, what was to stop the adventurous riverboat men and the enterprising owners from trying the river's tributaries right out into Nebraska Territory? And, eventual ly, the Advertiser of Brownsville in 1858 reported a steamboat ascending the Big Nemaha as far as Falls City, and in 1875 the Omaha Herald tells of a small steamboat for commercial use plying the Loup River.

Certainly, if the steamboat could navigate these streams, the river sirens must have lured a captain and his vessel up the Niobrara. What, then, about the longest of the tributaries —the Platte —the river described by some as "a mile wide and a foot deep" or by others as "too muddy to drink and too clear to plow?"

The steamer Florida was reported by the Cass County Sentinel as heading up the Platte in March, 1859 with great difficulty due to rapid currents. The reporter commended the feat with great enthusiasm. However, the editor of the Telescope of Wyoming, a now defunct but then a rival river shipping point, painted steamboat navigation on the Platte in a different light: "It is well known that in low water it would be difficult to run a ship up that stream, much less a steamboat." The editor went on to tell his readers that at the passage of the Florida, the river was on a "bender"; that is, out of its banks.

The Territorial Legislature seemed to have had ideas about navigation of the Platte. The governing body officially requested the U.S. Congress to "grant John A. Latta 20,000 acres of land in the Valley of the Platte on the condition that on or before October 1, 1861 he should place on said river a good and substantial steamboat to run between the mouth of the Platte and Fort Kearny." It continued that Mr. Latta had to do all the necessary dredging and, they, the governing body, gave confidence to the idea, stating there was a sufficient volume of water in the river.

Was this then all there was to the navigation of Nebraska's rivers? Only a few steamboats, several exploratory miles upstream and back, and a petition to Congress?

The New York Tribune reported in 1852 that the steamboat El Paso went up the Platte "on the June rise and back on the same high water."

Previous to his fame-gaining and stirring story, "Man Without a Country," Edward Everett Hale mentions the El Paso's feat in a book titled Kansas and Nebraska.

Grant Lee Shumway in his "History of Western Nebraska and Its People," published in 1925, writes of an early June day in 1852:"...the first and only steamboat that was ever seen in Scotts Bluff County could be seen as cending the river."

Shumway continued, adding much detail: "The El Paso, as it proved to be, pulled into the bank below the fort where now R. S. Hunt's stock go down to water and made fast for the night." According to the historian, the El Paso continued up the Platte, but the current proved too strong and the steamer turned to begin the journey back down the river.

Shumway even mentions a few passengers alighting, one of whom was the trapper Reuleau.

Whether a steamboat was at Scottsbluff, and whether there was a passenger may be apocryphal, but history tells us there was such a man Reuleau and also a steamboat named El Paso.

Reuleau was mentioned by Francis Parkman in his classic on the Oregon Trail as being "one of his if not elegant or refined companions, but a welcome addition to society at Fort Laramie in 1847." Reuleau, according to biographies of mountain men, was a small statured man made even shorter in appearance by the loss of the front part of both of his feet by freezing. Quite possibly the cherubic, happy-go-lucky trapper was returning from the Missouri with "a red dress with bright buttons" for his Indian woman, whom he had married.

If the story as reported by Shumway was a hoax, the perpetrator of it picked the correct steamboat and the proper captain.

The El Paso, a sidewheeler of shallow draft, was 180 feet long and 28 feet wide. She had been chartered by Pierre Chou- (Continued on page 48)

In Touch with the World

Environmental awareness is a many facted art, involving women in cumbersome waders, seeking crawdads. Our workshop placed us among the wonders of nature not to identify, but to become aware

ONE MONDAY morning last May, Dick Nelson, Conservation Education Coordinator for the Game and Parks Commission, strolled past my desk and dropped a light blue flyer on my type writer, smiled and quickly retreated to his office. Suspicious, I thought, but then felt obliged to pick it up as it was obvious that Dick had left it there for some reason. The first thing I no ticed was "Camp Harriet Harding, Louisville, Nebraska, June 5-7".

At first it struck me like receiving a bar of soap from a friend —a hint that I was being sent off to summer camp to keep me out of his hair. Then I noticed the title of the flyer: "Environmental Education Workshop", and I remembered that I had been harassing Nelson for information about just what was being done to promote studies in Environmental Education. He kept telling me that there was a program coming up that he thought I should attend, and his subtle hint that Monday morning left no doubt in my mind that I was about to attend that program and observe first-hand, as a student, just what is being done to promote an awareness of man's environment.

I arrived at Camp Harriet Harding the night of June 4 with my duffle bag neatly packed with tooth brush, changes of clothing, field boots, rain gear and sleeping bag, feeling just like a school kid arriving at "Camp Grenada" after getting the quick brush-off from mom and dad. And probably like that kid, I was skeptical of the whole situation as I really wasn't looking forward to three days of lectures from some university biologist in the midst of a mosquito-filled classroom.

Others started arriving, and I was intrigued by the variety of people who were gathering on that bluff overlook ing the Platte River. As I started meet ing those people, who had somehow also taken the hook and were beyond the point of no return, I discovered that most of them were teachers.

Some were experienced old-hats, veterans of the classroom; others were student teachers working on their master's degree in education. Then there were youth leaders from all facets of life —resource people, Game Commission employees, and just interested observers trying to broaden their repertoire of experiences. A true experience was indeed in the offing.

A four-inch bur oak limb had been sliced into neat wafers. Each wafer had two holes drilled near the edge through which a grocery string had been threaded and tied. These neck laces were our backwoods dog tags, with colored ink designating which team we had been placed in, for what was to come. In all, about 35 chunks of wood could be seen bouncing off the chests of 35 people busily setting up residences for their three-day tour of duty in nature's woodland work shop.

We all gathered for breakfast the next moring at 7 sharp, experiencing that kind of hunger that only the outdoors can cultivate. I honestly believe that every pancake and strip of bacon had disappeared by 7:05, and the cook was ready for a vacation. Now to what we had come for.

We were immediately separated into groups of six, and the course facilitators were introduced by Neal Jennings, who is an extension forester with the University of Nebraska and who was also to be one of our facilitators (workshop instructor). Others were Larry Barber, an extension forester from Clay Center, Gary Christoff, holding the same title from North Platte, and Dick Nelson, the one responsible for me being there. Dick, as I have mentioned, is the Conservation Education Coordinator for the Nebraska Game and Parks Com mission in Lincoln. Then Dr. J. O. Young, who was the course instructor for those attending the workshop for one hour of undergraduate or grad uate credit, gave a short speech to get the ball rolling.

It was announced that in our groups of six, we were going to play a "six bits game". Truthfully, the consensus at that time (if we would have been polled) would probably have indicated that this announcement did not arouse uncontrollable enthusiasm. We were all complete strangers to each other, coming from all parts of the state and from all walks of life. Now what kind of basis is that for game playing?

Nevertheless, we were told that there was a problem to solve, and six pieces of paper were passed out to each group. One paper went to each member of the group, and on each piece there was some information. You could tell the rest of the group what that information was, yet you could not show them your piece of paper. This was the problem: "In what sequence did the apes have the various teachers during the first four periods?" Now from the question, you can see how abstract the situation was, and the bits of information were equally abstract.

Thinking back now on that game, I

can see the relevance to the course

clearly. Analyze the situation. Remember we were all strangers when

the six bits of paper were passed out.

Immediately, a trust developed; trust

that the instructor gave us a solvable

problem, and a trust in each other

that we were working toward a common goal. Then, ritualistic listening

could be observed; a kind of polite

listening, really without caring much

because the data had no relevance at

that time. The ritualistic listening was

gradually displaced by real listening.

The data began to mean something,

14

NEBRASKAland

MARCH 1975

15

It was evident that this game was staged as an ice-breaker, and it had a lesson to teach. It involved the techniques and processes of involving people in problem-solving activities. And, the success was made obvious by the application of group interaction and problem-solving skill to the environmental investigations that we did later. The lesson: "None of us is as smart as all of us."

The remaining 21/z days were devoted primarily to small group sessions in the field. The rain gear came in handy, and nighttime found us cleaning mud from our boots. Every one was actively involved in the process approach of studying soil, forest, water, wildlife and urban environ ments. Older ladies trudged through creek water and muck in hip waders obviously designed for duck hunters and river rats. Those same ladies would probably have shrieked in fear at the sight of an earthworm in their garden, but, involved in an environmental workshop, one gal plunged into the creek over her waders in an attempt to grab a crayfish for study.

In tree study, poems were composed by participants describing their observations. Sketches were also attempted, using burned sticks and green leaves to provide color to the drawings. Even the drawing utensils created a new awareness to the involved participants combing the hills of Camp Harriet Harding.

It was not until I had completed my first field study investigation that I realized the purpose of the workshop. I was not there to learn the difference between an oak tree and a maple tree, but to realize that there was a difference, and a reason for that difference. I was not there to learn the names of everything I observed, but to learn how to observe. Nor was I there to learn everything about my environment, but how to teach about my environment. I was to learn how to involve others in the understanding of nature. I was to learn how to investigate and how to participate in a group discussion.

I also learned not to ask the facilitator a direct question, because after many attempts it was obvious that I would be answered only with another question. Facilitators were also quite skilled in formulating well placed and well-phrased questions to promote investigation and discus sion between participants and nobody was at a loss for words. Group discussions were earnest, and an honest attempt was made by all to find a solution for any problem discovered in field investigations.

Probably the highlight of any environmental workshop is the Urban Investigation. In the case of the one that I attended, Louisville, Nebraska was the target for this phase of the workshop. The town was swarmed upon by us hill-people from Harriet Harding on Friday morning. The residents there probably really didn't know what to expect as this hoard of investigators, wearing oak slabs around their necks, descended on their village, and it is little wonder. Thirty-five adults who had been living up in the forested hills for three days and diving in creeks for crayfish are generally not too presentable to a quiet community which was totally unaware of their existence.

The purpose of this project was to become as familiar as possible with the town of Louisville, discover a problem area, investigate the situation, devise a solution to the problem, and investigate the workability of the solution. When finally convinced that we were not an uncivilized clan of desperate marauders, the townspeople provided their full cooperation. An interest was stimulated, and members of the Louisville press, and the originator of their Chamber of Commerce, joined us back in the hills for lunch and to observe our reports.

Most current programs in conservation education are oriented primarily to basic resources; they do not focus on the community environment and its associated problems. Furthermore, few programs emphasize the role of the citizen in working, both individ ually and collectively, toward the soltion of problems that affect our well being. There is a vital need for an educational approach that effectively educates man regarding his relationship to the total environment.

The Supreme Court decision regarding the one-man, one-vote concept, that has enabled the increasing urban majority to acquire greater powers in decision making, makes it imperative that programs developed for urbanites be designed with them in mind. It is important to assist each individual whether urbanite or rural ite, to obtain a fuller understanding of the environment, problems that confront it, the interrelationship between the community and surrounding land, and opportunities for the individual to be effective in working toward the solution of environmental problems.

This new approach, designed to reach citizens of all ages, is called "environmental education." We define it in this way:

Environmental Education is aimed at producing a citizenry that is knowledgeable concerning the biophysical environment and its associated problems, aware of how to help solve these problems, and motivated to work toward their solution.

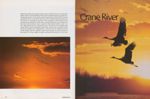

Crane River

Before the white man swept across the plains, there were vast, undulating herds of bison and hundreds of thousands scattered bands of pronghorns. Prairie dog towns ran for miles over the grasslands and the flights of some shorebirds were so immense that they were called passenger pigeons of the prairie. In a quarter of a century, they were gone. The masses of wild animals that marked the 1800s were incompatible with man's designs on the land and proved too easy a target for the market hunters' guns. Today, dog towns are few, and small in size. The bison live on refuges. But come March, the sky along the Platte River is dark with a quarter-million birds, the sandbars are swallowed in aclammerof calls. Spring has come to the Platte and the sandhill cranes have paused on their journey to the north. For a few weeks, at least, we know the prairie as it once was Crane

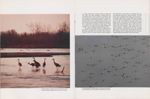

UNUSUALLY SILENT and with a laboring wing beat, the ungainly birds toiled against a gusting wind and spitting snow. It was late February and the vanguard of some 200,000 sandhill cranes was arriving at the slush-choked Platte River. Non-stop they had flown, some 600 miles from their wintering grounds on the Muleshoe Refuge in West Texas, or the Platte like shallows of the Pecos River in New Mexico. In the next few weeks, more cranes would join them from southern California and Arizona, northern and central Mexico. By mid-March, 70 percent of the world's lesser sandhill cranes would crowd a 150 mile stretch of the Platte River between Grand Island and Sutherland.

By morning the wind had subsided; the late-winter squall had passed. More cranes arrived, wheeling in flocks high overhead, their trilling calls often preceding their appearance on the horizon. Eager to land, to rest and feed in the wet meadows and grain fields, the whole sky seemed to be peeling off as cranes side-slipped to the ground. On wings of gray, another spring came to the Platte.

An archaic bird, the sandhill crane seems some how reptilian. Their remains have been found in sediments from the Eocene period, some 55 million years ago, and fossil evidence indicates that the sand hill crane has been a part of Nebraska's fauna for at least the last 10 million years.

Four subspecies of sandhill cranes are generally recognized. Two, the Florida sandhill crane and the Cuban sandhill crane, are non-migratory and considered rare by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Fewer than 600 Florida cranes, and less than 100 Cuban cranes, are known to exist.

The three remaining subspecies —the greater, intermediate and lesser sandhill cranes —are all migratory and pass through Nebraska. The number of greater sandhill cranes is believed to be less than 10,000, and the intermediate sandhill crane population is not known. By far the most abundant in North America and along the Platte during spring migration is the lesser sandhill crane.

Though called "lesser" these sandhill cranes are impressive birds. Standing three and one-half feet tall, the lesser, or little brown crane, weighs seven to eight pounds and has a wing span of six feet. On the wing and on the ground, the sandhill crane often seems to be a tangle of legs, neck and wings.

A description of the sandhill crane published in 1915 said that although "...he is big and tall, he is really not easily seen, for his coat is one of Nature's triumphs of protective coloration. Blue-gray in tone, it is obscure always; it fades into the gray-green of the prairie even in the brightest sunlight; it melts into the dusk of twilight or is swallowed in the blue dome of the heavens at midday."

The predominant color of the sandhill crane is an ash-gray. Lawrence H. Walkinshaw, noted sand hill crane authority, gave a more detailed account, calling the crane a light to pale mouse gray with a fawn color washed on the feathers of the back, wings and shoulders. Iron-rich soils common to parts of the crane's range are apparently responsible for the red dish-brown wash. Walkinshaw observed that cranes have the habit of digging with their bills in the ground during preening sessions. He concluded that the red dish coloration was the result of ferric-oxide stains. Immediately following their late summer or early autumn molt, cranes return to an unstained gray, supporting his theory.

The legs and bill of the sandhill crane are gray black. The area above and in front of the eyes, is varying shades of red or red-orange, fading into a drab gray where it meets with the bill. A stylish pompadour on the crane's rump adds the only flair to the otherwise drab plumage. By fall of the year in which they were hatched, young birds nearly resemble adults. In the field, the only clue to their age is a crown and forehead less red than adults.

A DAY ON the crane river begins at the roost. An hour before the first break of day, the mass of birds is silent. Occasionally a mournful, almost prehistoric warble, carries across the river. One or two other cranes join in, but there is little enthusiasm for call. Many are standing in the shallow water sleeping, others are beginning to stir. Some move up onto the sandbars and begin preening.

The cranes had arrived at the roost at sundown the night before, first one or two, nervous and alert to danger, and then the others, raining out of the sky like stilt-legged parachutists. In groups of two or three, 20 or 30 and masses of hundreds, they had made their way to the Platte's sandbars. As darkness enveloped the river, the cranes walked into shallow water, preening and rearranging their feathers. New cranes swarmed to the vacant sandbar behind them. It was the early hours of the next morning before the sky was clear of the call of homing cranes. For two or three hours, if the wind remained calm, the river would be silent.

Long before the eye could detect a hint of dawn, the voice of a crane announced its coming. An occasional call grew to a chorus and swelled to a clam or. Silhouetted against a still, starry horizon were cranes, thousands of cranes. With a tumultuous roar, five or six hundred birds leaped into the night. Excited by the departure of their companions, the remaining thousands set up a flurry of calls that swept the darkness. It seems as if the entire flock will take to wing. The hovering cranes circle and circle again as if to encourage the others on, but the river birds would have nothing of it. A dozen cranes settle back into the roosting flock but the calls of the others fade over the meadows of the Platte's floodplain. It is the first of many small departures and false starts.

With the approach of dawn, the excitement on the roost again swells, the birds are busy with the personal chores of morning. Most are occupied with fluffing and cleaning their feathers, carefully running their bills over each primary to oil and mend tears. One by one the cranes lower their long necks, ladle up a bill of water and raise their head to pour it down a tunnelous gullet. As the morning nears, the roost reverberates with calls alien to the ear of civil ized man. In time, each one raises up to test its wings. Many hop into the air and bow to court their mates. The frenzy grows in the mass of shoulder-to-shoulder birds.

Then, like a turning page, the entire roost lifts into the air. The sky is a confusion of wings and legs and stretching necks. Like wind-blown pappi they

sweep across the horizon. Some circle and return to

join the 50 or so that remain on the sandbars, oblivious to the din of calls overhead. The others split

and split again and fade over the corn and milo fields

to the south. Sixty more leave the roost and only a

handful remain to greet the rosy morning. Soon they

take to wing, and a single cripple remains on the

Platte, waiting for dusk, his companions, starvation

and death.

sweep across the horizon. Some circle and return to

join the 50 or so that remain on the sandbars, oblivious to the din of calls overhead. The others split

and split again and fade over the corn and milo fields

to the south. Sixty more leave the roost and only a

handful remain to greet the rosy morning. Soon they

take to wing, and a single cripple remains on the

Platte, waiting for dusk, his companions, starvation

and death.

THE SANDHILL CRANE is fastidious when it comes to roosts. Nothing short of the precise site will woo him to the river. Charles Frith, in his thesis on the ecology of the sandhill crane along the Platte, states that the basic requisite is water less than six inches deep, a broad channel approximately 2,000 feet wide, and infrequent vegetation on the sandbars and islands. It is obvious why the Platte River, traditionally described as a mile wide and an inch deep, plays such an integral part in the sandhill crane's migration.

The character of the Platte's bed is perhaps the most fragile element of the crane's life requirements. Its wintering grounds cover several thousand square miles in parts of two countries, and its breeding grounds are even more extensive, distributed over vast regions of three countries and two continents. The majority of the world's sandhill cranes, though, rely on a relatively short, narrow band of Platte River

The effect of losing the Platte as a staging area is not known, but the effect of man's past actions on the Platte, and indirectly on sandhill cranes, is known. Though cranes are found along the entire length of the Platte from Grand Island to Lewellen, they are concentrated during their spring holdover in three major areas: Lewellen to the upper end of Lake McConaughy; Sutherland to North Platte; and Lexington to Grand Island. Approximately 70 percent of the spring cranes roost between Lexington and Grand Island; nearly 30 percent use the stretch between Sutherland and North Platte; and a relative few roost above Lake McConaughy. These areas share one common feature —relatively little alteration by man. Their water-flow characteristics have not changed significantly in recent times. Spring floods still scour the channels free of colonizing trees and willows. Naked sandbars and shallow water areas persist.

Several areas within these stretches, especially from Kearney to Odessa and just west of Overton to Lexington, are nearly devoid of cranes. Others have declining spring populations. They too have common characteristics —constricted channels (often the result of funneling at bridges), encroaching vegetation and the near absence of open sandbars. The implication of future alteration of the river is obvious.

ONCE OFF THE roost they make their way, in four and fives, or hundreds, to pastures and hayfields, some pottering along, others flying low and direct. These native and cultured grasslands are the cranes' "marshaling areas;" where they group before moving into the grain fields to feed. Generally less than a mile from their river roost, marshaling areas are used for preening, dancing, resting, and when the opportunity presents itself, for feeding.

Here, the cranes seem anxious to be on with the day; the scene is one of chaos. After 15 minutes, or as long as two hours on some mornings, the cranes leave the marshaling areas. In small groups, or en masse if alarmed, they wing to the milo and corn to glean what the pickers and combines have missed.

Other cranes remain on the meadows most of the day. Some feed in the grain fields for a short time and then return to the meadows to loaf. The lowland meadows, with their intermittent drainages, never seem to be void of cranes picking in the soft soils or just biding time until the advancing season prepares the northland for their arrival.

Sandhill cranes are omnivores, taking plant or animal foods as the opportunity presents. Through out the year, and across three countries, their diet includes such varied fare as small birds, eggs, mice, crayfish, snakes, lizards, insects, berries, tubers, weed seeds and waste grain.

Early in the spring, cranes spend most of their feeding hours in wet meadows. Here, natural foods are abundant until growing numbers of cranes deplete the supply. In just a few days of probing the soil for fleshy tubers, tender plant shoots, insects and earthworms, several thousand cranes will rake a meadow clean. Early appearing frogs, toads and snakes are consumed with relish. Emergent plants are uprooted, searched for insects and grubs, and their fleshy parts picked apart and swallowed. Cow chips are methodically turned and examined for in sect larvae or undigested seeds and grain.

Walkinshaw observed that cranes break large pieces of food —small birds, mice, crayfish —into pieces, piercing them with their rapier-like bills and threshing them against the ground. Small tidbits are thus broken off and swallowed.

Waste grain is utilized throughout the cranes' stopover in Nebraska, and is relied upon more and more as the food in the meadows is depleted. Not only is grain taken, but stalks are picked apart and over-wintering cutworms consumed. As the crane buildup peaks in mid-March, the feeding grounds close to the river are gleaned and gleaned again, forcing the flocks to feed farther from the river. By the end of March, cranes will travel as far as seven or eight miles from their roosts to feed in the grainfields.

In 1915, Hamilton M. Laing gave an interesting account of the cranes' grain-feeding habits in Canada just prior to the fall migration. If the season were changed to spring and corn substituted for wheat, the description would be just as appropriate to Nebraska.

"Judging by the time he takes to a meal, one might be led to think that the quantity of grain he can store away at a sitting is prodigious. His regular hours on the field are from 7 to 11 a.m., and from 2 or 3 p.m. till dark. But he is a slow eater; he has not learned to chew and guzzle a whole wheat head at a time, as the geese do, but must pick to pieces with his dagger bill. Yet before he leaves for the South he gets enough grain below his gray coat to round and plump his angularity, and 15-pound "turkeys"-as

they are usually called by the plains folk-are not uncommon."

Both in the grain fields and on the meadows, sandhill cranes seem unconcerned with man, his live stock and his machinery, as long as they follow their normal routine. They move without hesitation among herds of cattle, into farmstead feedlots and even take advantage of farming operations that turn up the soil's bounty of insects, grubs and worms. Farmers mend fences and herd cattle within a few yards of loafing or feeding cranes, but cars that stop along county roads send fields full of cranes scurrying to the middle of the section. The sandhill cranes have learned to live with man, but not to trust him.

One of the crane's primary occupations in the spring seems to be dancing. At almost any time —on the roosts, marshaling areas, meadows or grain fields —cranes can be seen hopping into the air on fluttering wings. Once this frantic activity was thought to be exclusively a courtship display. Walkinshaw described the performance:

"Here they stalked along for a short distance, side by side, or one behind the other. Finally one bird began to act as a crane often does when near the nest —stooping to pick up marsh grass and then throwing it into the air. But this crane was not picking up marsh grass; he was bowing, almost touching the ground with his bill, then raising and pointing the bill into the air at a steep angle. He did this several times, then began bowing while at the same time rotating, slowly at first, then faster and faster, sometimes in a complete circle, sometimes in a half circle and then back, usually with head up, wings half-spread and drooping. When he stopped, he acted as if he were a little off balance, possibly a little dizzy. He continued to bow, holding his head near the ground, and some times swinging it from side to side. Again, he would spring into the air rising five or six feet, very light footed, with wings half-spread and legs dangling, partly bent, then drop gracefully and easily to the ground. Many times this crane leaped and whirled at the same time, but not always to the same height. Occasionally he fanned the air gracefully and slowly with his wings as he whirled. The mate stood in nor mal pose, watching the dance...."

Such elaborate courtship displays probably occur only as the breeding season nears. In mid-March, sandhill cranes are still two months away from nest ing, and the dancing is less polished. Fluttering hops, four or five feet into the air, constitute most of the activity.

Cranes mate for life and by March most pair

bonds are formed. The foreshortened display seen on

the Platte is surely a courtship ritual, but it has other

functions as well. Dr. Paul Johnsgard, professor of

zoology at the University of Nebraska, believes that

the dance as it is seen in Nebraska is primarily in response to agitation by man or simply a manifestation

of the bird's nervous condition. Much of the flutter

jumping on the Platte is probably just that —a court

ship display used at seemingly inappropriate times

as an emotional outlet.

bonds are formed. The foreshortened display seen on

the Platte is surely a courtship ritual, but it has other

functions as well. Dr. Paul Johnsgard, professor of

zoology at the University of Nebraska, believes that

the dance as it is seen in Nebraska is primarily in response to agitation by man or simply a manifestation

of the bird's nervous condition. Much of the flutter

jumping on the Platte is probably just that —a court

ship display used at seemingly inappropriate times

as an emotional outlet.

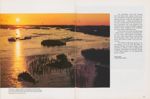

LATE IN THE DAY, as the light warms and the horizon deepens in color, cranes begin leaving the grain fields as they had come —in pairs, by dozens, and by the hundreds. In tight chevrons and ragged strings, they fly effortlessly over hay and grain fields, farmsteads and bands of shelterbelts. A mirror reflection of the morning's routine, they drift on locked wings back to the meadows, to the marshaling areas.

Half-heartedly they preen, dance and pick at the ground. Even after sundown, cranes continue to pour into the meadow, calling inquiringly to those on the ground. The sky is peppered with lanky, drifting cranes. Twenty thousand babbling birds crowd the meadow.

En masse they clamber into the sky and like a swarm of summer insects move toward the river. Climbing for only a quarter of a mile, they glide to

join the scouts that have tested the Platte's shallows.

Most fall to the sandbars, others are carried beyond

the roost and circle out over the valley. It is well into

the night before the sky is silent of their incessant call

ing. On some clear nights, small groups wander the

Platte's shores, barely clearing the cottonwoods, call

ing mournfully into the darkness. Winter has passed

and the cranes seem anxious to move on.

join the scouts that have tested the Platte's shallows.

Most fall to the sandbars, others are carried beyond

the roost and circle out over the valley. It is well into

the night before the sky is silent of their incessant call

ing. On some clear nights, small groups wander the

Platte's shores, barely clearing the cottonwoods, call

ing mournfully into the darkness. Winter has passed

and the cranes seem anxious to move on.

Now it is the first week of April and the Platte Valley is greening. The river has swelled with Wyoming snows and the farmland is being prepared for another season. At dawn, a roost of cranes moves off across the grain fields as they have for the last six weeks.

Today there is an urgency in their travel. Dropping into a cornfield, they are unusually noisy, calling almost constantly, picking at the waste grain half-heartedly. The day warms and a band of cumulus clouds sweeps through.

Halfway through the morning, the cranes leave the corn and cruise like a thousand vultures on spring thermals rising above the river. For hours they criss cross in apparent confusion. At once, as if sensrng their time, they string out, a ragged line in the lead, smaller lines and clusters following, and, with measured wing beats, leave for the north and their breed ing grounds. The smaller lines fall into the larger formation, and just before they are lost to view, the line becomes an immense serpent, wending toward the horizon.

By mid-April the Platte will be silent; a silty prairie river. In October a few cranes will return, among them the young-of-the-year, but most will rest elsewhere or not at all on the return to their wintering grounds. In the summer climates they will wait for the passing of another winter on the prairie and their Arctic nesting grounds. The crane's migration to the north replenished their numbers but natural and unnatural losses began cutting away at the surpluses before their young could even fly. By February they will need to go north again.

For more than 10 million years the Platte has known the comings and goings of the sandhill cranes. Individual birds it has known for 20 seasons or more. Once, man sensed a kinship with the river and its cranes and marked his own time by their comings. The changing seasons stirred something animal with in him. Today, a civilized world rushes by the river and its cranes, heedless of the flocks overhead. But for those who still listen for such things, the call of the sandhill cranes means spring has come to the Platte.

"On motionless wing they emerge from the lifting mists, sweep a final arc of sky, and settle in clangorous spirals to their feeding grounds. A new day has begun on the crane marsh. When we hear this call we hear no mere birds. We hear the trumpet of evolution. He is the symbol of our untamable past, of that incredible sweep of millenia which underlies and conditions the daily affairs of birds and men.

"And so they live and have their being — these cranes —not in the constricted present, but in the wider reaches of evolution- ary time. Their annual return is the ticking of the geologic clock. Upon the place of their return they confer a peculiar distinction.

"Our ability to perceive quality in nature begins, as in art, with the pretty. It expands through successive stages of the beautiful to values as yet uncaptured by language. The quality of cranes lies, I think, in this higher gamut, as yet beyond the reach of words."

Aldo Leopold A Sand County Almanac

Our group safari visits the Platte to witness a migration special

CAMPING WITH THE CRANES

CLOUDS AND clouds of ducks were rising from the marsh into a heavy sky, and we just stood at the edge, overawed. A small group of pintails streaked by to the north, and mallards by the thousands rose in flocks as we walked closer. Acres of water lay before us, and it seemed that every square foot must have contained a duck before we approached.

"My gosh, look at them," somebody whispered.

"Small flock of whitefronts," Earl pointed out.

"Whitefronts?"

"Geese."

"Hey! Over there! At 10 o'clock," Tom whispered excitedly.

We walked automatically, necks craned to the sky. Had there been a hole in the ground, we would have all fallen in, oblivious to the danger.

Streamlined silhouettes against weighted gray, the waterfowl just kept getting up, first from the near edge then from the middle of the pond. We suspected that the far edge of the marsh was still black with sitting ducks when we finally reached water's edge.

Dozens of muskrat houses speckled the gray expanse of sky-reflecting water.

"I've never seen anything like this before," Tom whispered with a touch of awe in his voice.

Suddenly I felt a bit of proprietary pride. I'd had nothing to do with the presence of those ducks on that marsh on that day, but for years I had been watching ducks on the little marshy ponds in Clay County. It was close to the "briar patch" where I had been born and raised. I had learned over the years to look forward to spring and fall when reports of moving waterfowl began filtering into the Game and Parks Commission of fice where I worked as a writer. And now I was sharing the timeless experience with people who seemed to be enjoying it as much as I did-perhaps more-for it was an entirely fresh experience for some of them.

It seemed as though I was introducing a group of old friends to each other, feeling confident that they would all enjoy their association and benefit from it. I guessed that at least one or two of our group had begun to feel something about the birds we were watching. I'm not exactly sure what it is people feel about ducks, but I know it's good to watch them rising off a wetlands pond in the spring when the air is just beginning to smell a tiny bit green.

The land we were standing on was part of a federal Waterfowl Production Area. These marshes, called rain water basins, are administered by the Department of Interior, Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife. They were established to provide breeding and nesting areas and a migratory stopover. Many such marshes have been acquired in south-central Nebraska, and uses vary from hunting to trapping, bird watching, sightseeing and nature study. Peering through reedy grass, we spotted a muskrat waddling nervously (Continued on page 42)

Prairie Life/ Native Hunter

WHEN WE THINK of the pristine prairie, and the ecological interactions of its flora and fauna, we often overlook an animal of powerful im pact. It was a predator that feared few animals, killed even those of superior strength, yet fed on fruits and roots as well as flesh. In geologic time, this species was relatively young, having been on the earth less than two million years, and in what would become Nebraska, for less than 10,000 years. More than any other animal, though, they were the dominate force of the prairie. The name of this predatory mammal was man.

Early man's food, how he hunted and his effect on the environment are as ecologically important as the life habits of the bison or prairie falcon. For like the other prairie animals, he was part of the grasslands and af fected, and was effected by, its other members.

We know little about the way of life of prehistoric man in North America; only vague hints gained from piecemeal evidence offered by his artifacts, skeletal remains and cave-wall scratchings. Just where man fit into the ecological scheme of things is conjectural, but we can be sure that he was more in harmony with the environment than any of his descendants have been since. He affected the prairie little more than any other animal species. By the time the white man swept across the grasslands, the American Indian was the "man" of the prairie. We know a great deal of his life and interactions with the other animals of the prairie.

Understandably, the Plains Indian's culture had grown around the grassland; its plants and animals. To the Indian, the prairie animals were not only food but shelter, clothing and implements as well. The worship of animal spirits was thecoreof their religion.

When the white man first penetrated the mid-continent in the 1750s, there were eight tribes of Indians in what is now Nebraska. The Ponca, Otoe, Omaha and Pawnee lived in permanent earthlodge villages in the eastern portions of the state. They were largely sedentary, raising crops of corn, squash, sunflowers and potatoes, but still they engaged in wide ranging buffalo hunts to add meat to their larders. The Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Potawatome were semi-nomadic tribes that ranged the plains, follow ing the migrations of the buffalo. To all of these tribes, animals meant food.

Before the Cheyenne and Sioux moved onto the Plains, they were woodland tribes, relying on small animals and plants for food. They had no horses then, no stone-tipped weapons suitable for killing large mammals, and little knowledge of how to prepare and preserve the products of hunts. Their only pack animals were 38 NEBRASKAland dogs, which limited the possessions they could move from place to place. From the leavings of prehistoric prairie man, they learned of spear and arrow points and quickly adopted these implements or fashioned their own. From neighboring tribes that had hunted the bison, they learned hide tanning techniques and the construction of implements from bone, horns and hooves. With the arrival of the white man's horse, they were well equipped and educated in the ways of the nomadic hunter.

The seasonal movements and daily living habits of the western tribes were completely at the whims of the vagrant bison. Their camps moved as the buffalo moved, and tribal law and custom grew around the bison hunt. They depended entirely on the buffalo for food, and hunting was thus a highly organized tribal effort. Hunt ing by small groups or individuals was not permitted, and violators were se verely punished. To survive the harsh winters, large numbers of the woolly beasts were needed and hunts for "sport" were not indulged.

Before they had horses, the Cheyenne made foot surrounds of bison herds and drove them over cliffs or into pens of brush where they were clubbed, speared and shot down with arrows. In the winter, when the snows were deep, they herded the buffalo into deep drifts where they floundered and could be easily overtaken by braves.

With the white man's horse, securing food became more reliable and times of famine were few. To the Sioux, the horse was the "sacred dog." Mounted, they became the ultimate predator. At a full gallop, braves could stream along the stampeding herds and thrust their lances into the vital organs or sink arrows into buffalo after buffalo. The Plains Indian's symbiosis with the buffalo is well known*, as is his total utilization of the entire carcass.

The pronghorn was another important game animal to the Nebraska Indian. Before the white man, the pronghorn was probably more abundant in their range, and it was far reaching, than were the bison. Smaller and less spectacular than the undulating herds of buffalo, they often went unnoticed and were not men tioned in camp logs and journals.

The Cheyenne captured large numbers of pronghorns by herding them into enclosures, a technique still used today to capture them for transplant ing to new ranges. When the tribe was in need of antelope flesh for food and the soft pliable hides for warshirts, they made preparations for a "drive". On a broad flat, they built two brush fences, 8 or 10 feet high, wide at one end and almost converging to a point on the other. Where the two fences came together, they dug a pit five feet deep, and partially concealed it with low bushes. The opposite side of the pit was armed with pointed sticks.

To insure the success of the hunt, the tribal medicine man exercised his spiritual power. After elaborate preparation of his lodge —four circles of antelope feet were arranged around the fire, stems of white sage were carefully laid around the edge of the tipi and the floor of the lodge cleared of weeds and grass —the medicine man spent a day and a night alone, fasting and chanting. He was then ready to call the antelope. Painting himself like a pronghorn— mouth black, back red, belly white, and an antelope horn on each temple —he left his lodge naked except for a loin cloth. Filling and lighting his pipe at the apex of the pen, he walked be tween its wings out onto the prairie, singing his sacred song and offering up his pipe to the Great Power. Then he walked back. Four times he did this before placing his pipe on the ground at the edge of the pit. Two young braves then started off across the prairie, one along each wing of the trap. After a time they came to the antelope that were running to the trap. They called to the others. When the antelope were within the wings, other members of the tribe came out of trenches in which they had been hiding and closed off the trap, driving the antelope into the pit where they were overpowered. The hunt was over. More ceremony followed, and a fat young antelope was taken to a high hill and cut into pieces as a sacrifice.

Elk, deer and wild sheep were important game animals to the Plains Indians, too. Black Hills bighorn sheep, former residents of the bad lands and parts of the Pine Ridge, were locally common and unsuspect ing. Of all the Indian's big game, the sheep was said to have been the least wary, and could usually be taken with bow and arrow after stalking.

Elk were hunted and killed in large numbers in midwinter by the Sioux. Using a long pole with a keen-edged knife tied on the end, men on snow shoes would follow a herd into deep snow and sever the hamstrings on as many elk as they needed.

Elk, like antelope, were sometimes driven into enclosures and killed. Cheyennes, like other tribes that moved out from the woodlands, probably brought with them the practice of snaring elk and deer along their well traveled trails. Converging stakes were used to funnel the animals into a hanging noose of rawhide or sinew. Once in the loop, it tightened so that any effort by the animal to extricate itself only hurried its demise.

Deer were also hunted by stalking. Colonel Richard Dodge described the Indian's technique in 1883:

"Often it is necessary to crawl to

the nearest point for a good shot,

MARCH 1975

39

Some men removed their moccasins,

for they could stalk more quietly and

believed this brought good luck.

When stalking, a man must choose his

course, hold his breath, and walk very

slowly. By placing his toes down first

and then putting his weight on his

heels, and taking only a couple of

steps at a time, he could be sure no

noise had been made.

Some men removed their moccasins,

for they could stalk more quietly and

believed this brought good luck.

When stalking, a man must choose his

course, hold his breath, and walk very

slowly. By placing his toes down first

and then putting his weight on his

heels, and taking only a couple of

steps at a time, he could be sure no

noise had been made.

"Before shooting, the first animal to be killed is picked out. Then when ready and in position, the first arrow is shot at the first animal, the next at the second and there may be time for a third, but after that, the others are out of range. Now it is the time to butcher."