NEBRASKAland

February 1975

NEBRASKAland

VOL. 53 / NO. 2 / FEBRUARY 1975 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Fifty cents per copy. Subscription rates $5 for one vear, $9 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. commission Chairman: James W. McNair, Imperial Southwest District, (308) 882-4425 Vice Chairman: Jack D. Obbink, Lincoln Southeast District, (402) 488-3862 Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-central District, (308) 745-1694 Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-central District, (308) 452-3800 Director: Willard R. Barbee Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, |r. Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: Jon Farrar Greg Beaumont, Ken Bouc, Steve O'Hare Contributing Editors: Bob Grier Faye Musil, Tim Hergenrader, Roland Hoffmann Layout Design: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1975. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska Contents FEATURES TOO MANY BUCKS YOUTH CONSERVATION CORPS 8 WINTER'S DRESS 10 FRONTIER FIASCO 16 YOUR WILDLIFE LANDS/THE SAND HILLS MUSKIES IN THE MAKING PRAIRIE LIFE/FLIGHT 18 35 36 HUNTING-DOG HEAVEN 40 DEPARTMENTS SPEAK UP TRADING POST 49 COVER: The prairie falcon is a winter resident of Nebraska, with a range primarily in the central and south-central Panhandle. Found only west of the Missouri River, this falcon could be threatened with extinction and is declining in some areas from pesticide poisoning. Some nesting is done in the Pine Ridge in the spring. Horned larks are among the falcon's main winter food. Photo by Jon Farrar. OPPOSITE: Ice fishing, despite the cold, can be a pleasant and beautiful experience — especially if the fish are hitting. Photo by Jack Curran.

Speak up

Paste-on EyesoreSir / I enjoy NEBRASKAland Magazine, however I would like to bring your attention to the fact that you have an eyesore that I feel should be corrected. Each month you are putting one of the nicest covers on the magazine, then turning around and ruining it with the mailing address. I find very few magazines that do this; most of them put them on the back side. I hope to see a change.

Jim Weinberger McCook, Nebr.Placement of the address label is a problem, as it does have to be somewhere so that the post office can find it. Also, we often carry attractive photos on the back cover, and s/nce the front is already "messed up" with the magazine logo, it was thought to be the most logical place. We do try to place the label out of the way and neatly to one side. (Editor)

Pleasant IntroductionSir / When visiting my sister in Lincoln, I was introduced to your lovely state. I especially enjoyed the Sand Hills country... and the feeling of expanse. A horizon that could be viewed from four directions? Unheard of in my New England with its overpopulation of trees!

As a longtime Sudburyite, I've lived adjacent to Concord, Mass. for many years so the opening sentence of the "Wapiti Wilderness" article (Nov. 74) quoting Thoreau seemed very familiar.

Dr. Vincent Kershaw has written a marvelous article. I especially enjoyed the second paragraph on page 31: "Wilder ness is another world. In it, time is not an hour or a day or a month, but sunrise and sunset, moon changes and seasons. There man can see himself in relation to the overall scheme, the strength of life and the purpose of death." Beautifully expressed!

What a worthwhile project. I do wish you success. Please let me know when you get around to money-raising.

Miriam F. Marquis Sudbury, MA Things Are DuckySir / Thought you might be interested in this duck-hunting photo of Rich Osentow ski, on the left, and my 14-year-old son Tom, and our dogs. The blind we use is on the Platte River west of Gibbon. This was taken on November 4, 1973.

Archie Boyd Grand Island, Nebr. Hey, Save HaySir /1 was appalled this fall when the State Department of Roads shredded much of the grass cover on the state's roadsides. For years now, the Game Commission has encouraged farmers and landowners to set aside land for much-needed wildlife habitat. I am certainly not opposed to this. This roadside cover was not utilized for livestock feed, but was simply shredded and destroyed.

Think of the thousands of acres of cover that was needlessly destroyed throughout this state and also the many gallons of gasoline used. My question is, why was this done?

Roger Haake Western, Nebr.Although the bulk of haying by the Department of Roads was done for the pur pose of providing much-needed hay for livestock, spokesmen for the department said some shredding was done in some sections of the state. This is not done annually, but usually on a three-year cycle, and primarily to control tree growth. Most of the benefit of the grass is for wildlife nesting in the spring, and all such mowing is held off until fall, when it is least damaging. If not ground up by rotary mowers, the trees would have to be cut by hand, which would be time consuming and even more expensive, the Roads Department feels. Baling operations, by the way, was about a break-even proposition, but provided about $178,000 worth of hay to feeders who needed it badly last fall. (Editor)

Down With ViolatorsSir / Since my release from active military duty in 1971 I have found hunting to be my most enjoyable pastime. After settling in southeastern Nebraska in mid 1971 my hunting partner and I have hunted deer every year that we could get permits. We always hunt whitetails the way they should be hunted —by fair-chase methods.

Recently we found that our familiar hunting grounds might be off limits in the future because a few hunters trespassed, hunted deer with citizen-band radios as they would hunt coyotes, and worst of all, this all took place after the regular firearm deer season. After several years of proper conduct, abiding by the laws, and hunt ing always in a sportsmanlike manner, the news we received from this landowner is most disgusting.

The message here is one I would like to convey to all law-abiding hunters. I want them to see what may be ahead for them if they fail to take action. Wake up, law abiding hunters, before it's too late. Don't wait for the conservation officer to handle all violations. He can only make rounds every so often. Don't wait for the landowner to handle the violations because you may hear the sad news that I recently did. There's a violation form on your Nebraska Hunting Guide. If you have knowledge of a violation, write it up.

Let's get these outlaws who call them selves hunters out of our familiar hunting grounds so we can keep them familiar.

Roderick Kahlenbeck Springfield, Nebr.NEBRASKAland Magazine invites all readers to submit their comments, sugges tions, and gripes to Speak Up. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters. — Editor.

Too Many Buoks

For more than 20 years, Bess Hickey has been actively hunting Nebraska deer

ROUND 1953 I'd go out into the hills and see maybe seven or eight bucks with my binoculars, and I thought,'there's getting to be too many bucks.' So, I got a permit, and I've hunted ever since."

For Mrs. Bess Hickey of Alliance, deer hunting was as natural as breathing —an extension of her early ranch ing and trapping days along the Niobrara River. Her annual hunting trips started in 1953 and have continued each year since.

Not so unusual you say? You've seen lady deer hunters before?

Well, perhaps you have, but how many 76-year young gals have you seen out deer hunting? And how many of them have taken two deer each year that double permits were issued, and have filled a permit each year but one since?

Of slight and slender build, the term "from pioneer stock" perfectly describes Bess. She continues with her ranch work and sports participation long after younger men and women have retired to less active lives. Besides hunting, Bess is an avid bowler, meeting once a week with teammates in a registered league at Alliance.

The trophy deer and one antelope mount adorning the walls of her home in Alliance bring back memories of each exciting hunt on the rough, rolling hill country of the Hickey ranch along the Niobrara river.

"Originally, I hunted alone, but since my eyes haven't been as good, I hunt with a boy from the ranch. He helps spot them for me. He doesn't have much time, though, so I still go out alone many times. I was alone when I took that one there," pointing to a handsome 4 pointer mounted on the living room wall. "My husband was with me when I got that antelope."

The ranch was split by the Niobrara, and for Bess this was a blessing during her early years of deer hunting.

"We could get a permit in the Pine Ridge Unit, and if they weren't sold out, I could get one in the Plains Unit also. That way, I could hunt both units without leaving the ranch. Later, of course, you could only get one permit."

"I've got a small Jeep, a 4-wheel-drive with a winch on it; that way I never had to do a lot of walking. Up to last year I always loaded the deer into the Jeep myself. I try to shoot them on a side hill, then drive the jeep below and roll them on. You have to be careful though when you're cleaning them —that they don't slide on down the hill."

Marksmanship came naturally to Bess Hickey.

"I've had the same gun since the beginning. I bought it secondhand. For my first deer I had borrowed a 30/40 Krag from a friend. When he gave me the Krag he sent along some shells, and told me to go out into the hills and shoot it. I shot once and hit what I was aiming at, so I never shot any more. After that, I bought my 30/06, which I've used every year since."

The lack of practice doesn't show in her trophy room, and her percentage of one-shot kills would be a match for the majority of deer hunters, male or female. "I don't think I usually shoot more than 200 yards. There was a year I'd broken a leg on one at long range, which we were able to recover, but I'll stick to under 200 yards anymore.

"I will admit I'm not as good a shot as I used to be. I said this year if I didn't get one I'd give it up. I don't plan on quitting though, until my health is too poor.

"I had my most fun, of course, when I got that big one.

"We drove north in the Jeep, the 12-year-old Skavdahl boy and I. This buck and three does came out of a draw, close enough to shoot, but I wanted to get him so bad I didn't. We tried to get closer, and we got as far as we could in the Jeep and then started following him on foot.

"We'd get to the top of one hill and they would just be going over the next one. We followed him, I think it was to the fourth ridge. I threw the shell out of my gun, and said I thought he'd given us the slip. Then I started to stand up and saw a doe about 200 yards away.

"We dropped back down and I loaded my gun and raised up again, and there he was. Four points on a side!

"I did a good job shooting that day, and got him with one shot. He was fat and pretty. I do the field dressing myself—one of my brothers sent me a knife and hatchet, which work real well. I carry some hand towels, and plastic bags for the heart and liver.

"My other trophy, I'd hunted until the fourth morning. Saw a doe, but I knew there were several bucks. I wanted one of them.

"I had to go through a part of Agate Park. Well, the man came out and told me I couldn't hunt there. I knew that, but I had to go through part of it to get to the hills. He was kind enough to show me where they usually come out, so I went up behind an earthen dam and laid there for 45 minutes and scoped.

"Finally, this old buck and four does came over the hillside, and I missed him the first two times. Overshot him. I'd laid down so he couldn't see me, but when I shot over the second time, he ran back toward me.

"I sat up like I should have, and got him.

"The park man came up and said he'd help me load him. He'd never killed a deer before, apparently, and I told him I would have to hog-dress him first. "He said 'I'm sure learning something', as I showed him how to dress one."

While almost all of Bess's hunting has been around the ranch, she did venture to Montana one year, and was rewarded with two elusive whitetails.

"I got a white-tailed deer in Nebraska now, and those two in Montana, but the rest have been mule deer. We've had the hides tanned and I've had deer gloves, a short jacket, and moccasins made." The Hickeys have been living in Alliance since 1959, but her strong ties to the ranch along the Niobrara set the tone for many of her memories of early Nebraska life. "I was born on that ranch, and I've lived up in that area all my life. I trapped beaver on the Niobrara and skinned skunks, coyotes, beaver, muskrats and a mink if I could catch one. I've even got a beaverskin coat; its a little out of style, but it sure is pretty. I trapped the beaver and sent the hides in. I've also got a coyote-fur muff and scarf—my husband shot the coyotes. "I caught 21 beaver one winter, all in the Niobrara. Trapped four of them in one night. "I knew Captain Cook at Agate; Jim had his house and museum there. Harold ran the post office." Along with her hunting and bowling, Bess paints wildlife and ranch scenes and keeps a running scrapbook of faimily photographs and unusual clippings, including photographs of the great blizzard of 1949 that trapped ranchers and cattle in much of Nebraska. Bess splits with convention on another of her hobbies-collecting rattlesnake rattles. She now has, over 900, accumulated over the years. "I've got 2 jars, one with 497 rattles, and 400 in the other!" Memories are great for idle moments, but for Bess Hickey, idle moments are few and far between. A life in the outdoors, a kinship with the land; all of these things are denied to no man, or woman, as Bess Hickey readily proves.

Youth Conservation Corps

Hard work, learning and recreation are basis for this program. Benefits accrue to all involved

Photographs by Roger WilsonIT'S 6:30-get up sleepyhead. We have to get down for breakfast and then load tools, food and water in the rig so we can leave at 7:30. Better not forget my gloves and yellow hardhat or the group leader will get me.

"It's going to be a great day, we're planning to finish the shelter at Red Willow and then work on the nature trail at Trenton. I wonder where our campout will be this weekend?"

This is a typical morning at the Youth Conservation Corp camp in McCook, Nebraska. After being in operation for three summers, the camp has had a total of 90 Nebraska youths in its program. They have come from Omaha, Auburn, Lincoln, Battle Creek, Scottsbluff, Kearney, Wauneta, Bridgeport, Culbertson, McCook, Fremont, Imperial, and many other communities.

What is this YCC? Why are these young people here? How did they get here? What do they do? How can I participate in YCC? Such questions have been asked by people in Southwest Nebraska, and for that matter, all over the state. The ''Corps" can be seen working around the reservoirs trying to improve them (Continued on page 42)

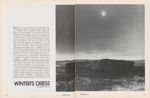

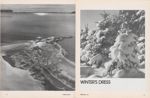

WINTER'S DRESS

BEAUTY, it is said, is in the eye of the beholder. Certainly the capacity for enjoying beauty varies with the individual, but the magical changes which take place when winter touches her frigid wand to a brown, seemingly dead landscape create fantasy shapes and sculpture almost limitless in their variety. Although often accepted routinely, as the accompaniment of the sea son, the marvels of winter are fascinating and magnificent embellishments that awed early man and still should bewilder modern earth residents. It is in the nature of man to admire what is difficult only until bore dom sets in, and enjoy what is beautiful only until something more attractive draws his attention. But, it is this fickleness of mankind that leads to callousness, and in turn to insensitive snobbery. As it is also said, the best things in life are free, and certainly the cost of enjoying one of winter's many spectaculars comes at a very reasonable price —requiring only a little effort and a willingness or ability to appreciate. Transforming a humdrum or blighted scene into textured, snow blanketed loveliness is an uncommon accomplishment. And, when an already fine view is touched by winter's magic, it becomes fantastic. Not everything about winter is beauty and light, but it has the advantage of concealing, transforming and highlighting the great outdoors -and all at once-so that a few moments among a particularly splendid example can provide memories that last a lifetime, and that can actually alter a person's outlook and ideals from then on. Perhaps this is the true magic of winter...the ability to create beauty...on the outside of the inanimate, and on the inside of the living

10 NEBRASKAland FEBRUARY 1975 11

WINTER'S DRESS/ HOARFROST

A FEW YEARS ago, near the end of one of those beautiful, wonderland falls, we had risen early for some now forgotten reason. My wife had gone outside on some errand when she opened the door and told rue to come out. There I was greeted by such a magical vision that I was spellbound. Hoarfrost, thicker than any we had ever seen before, covered everything. It was still a good half-hour until the first light of day, but the full moon was just entering its final quadrant and shown brightly. The stars twinkled and shone in their very best manner as if very proud of their part in this magnificent spectacle. Everything within our vision seemed alive with a dancing, glimmering, slivery beauty, as if every particle of hoarfrost, when it formed, had absorbed the rays from the night lights.

No wonder the silversmiths have always claimed that silver gets its color by absorbing the rays of the moon and the stars. They ask us to fondle it closely in our hands with its soft, cool touch. Then you will be able to understand not only why this is the metal of love, but also the metal of kindness and compassion, which be gets a feeling of brotherly love toward all. They also tell us that the better the craftsman has built his design, the stronger one reacts to it.

You watch the affect of this night light on the trees and shrubs; on the flowers and buildings and the lawn — all of them covered with hoarfrost, or dew frost as some prefer to call it. We were amazed at how each still seemed to reflect its own particular shades of silver.

As we watched, we became aware that daylight would soon arrive. At first there was just a slight shading of the lights, which kept increasing until only protected corners retained a night darkness. Then a faint light in the east, followed by a rosy hue, told us the sun was not far behind.

I tried to think of an adequate word to describe all of this: magnificent, superb, glorious, and many others. I think inspiring came closest. That it surely was, but somehow it took still more to do this wonderland justice.

We were very fortunate as our home in Norfolk, Nebraska, sits near the crest of a rather high hill. We looked downhill toward the east, and up toward the west. From the south of our home we could catch the light from nearly every angle. The funny thing about it, it seemed that any view seemed to be the best possible one.

Suddenly, before we were fully aware of it, the sun became visible. As it rose, the first things I noticed were the enormous size and its beautiful red hue. The night had cleared the air of nearly all of yesterday's accumulation of dust and other foreign matter, and on this morning there were very few clouds. Those visible were small and fleecy, with only an occasional one large enough to have developed a dark center. It was fascinating to watch the development and play of colors on these clouds, as the fleece changed to yellows, oranges, pinks, then purples, and finally a deep red or even scarlet.

We returned to the main performance of watching the fascinating picture as the rays of the sun would penetrate into and sometimes through the branches of the trees. As they did, it seemed as if the silver in the frost now absorbed the rays of the early morning sun and in corporated them into their color scheme, not only in the trees but everywhere that the frost existed.

Then a look west where the sun's rays hit more directly on the frozen particles. We constantly had to look both east and west because the diverging angles of the rays seemed to reflect an entirely different glow. The only comparison I could think of was a great jewel box being dumped out, with every kind of gem being present, and each gem cut individually by a master jeweler. This was even more apparent when, as if on a prearranged signal, a cascade of these beautiful gems seemed released from all the trees. As they fell, each particle was so tiny that they merely felt cool wherever they touched our skin.

One just had to feel awe witnessing such an occurrence; at the wonder of Mother Nature bringing this magnificent spectacle right to our doorstep. We continued to watch and it seemed that all the falling gems melted upon contact with the earth, but even the little rivulets seemed to sparkle and glisten together with their happy gurgle as they disappeared into the soil. We couldn't help but feel humble at the thought that Nature had seen fit to bring one of the most sublime, wonderful, colorful sights of her Wonderland to us in our own yard.

Perhaps we should witness more dawns.

frontier fiasco

PANDEMONIUM reigned in the Arikara village throughout the long night. The women wailed, the men shrieked. There was the din of drums, howling of dogs and braying of livestock.

Peace talks had failed, retaliation had not been made, and still the village was surrounded by soldiers and artillery and angry Sioux. Still the Arikaras hung back within their fortifications, unpunished.

The foray was part of a struggle to secure a monopoly on fur trapping along the upper Missouri and Yellowstone rivers. Several white interests had been scrambling along the river since fall, trapping and trying to transport furs to the eastern markets, try ing to get the jump on one another.

Then the Indians intervened.

In the spring of 1823, Andrew Henry of the Missouri Fur Company was moving downstream with his trappers and their winter's catch when Blackfoot Indians attacked. He lost four men and was driven back to his stock ade on the fork of the Missouri and the Yellowstone. About a month later, Robert Jones and Michael Immell, with their Missouri Fur Company trap pers, were also attacked by Blackfeet. Seven men, including Jones and Immell, died.

Meanwhile, William Ashley was leading another hundred men to join Henry. Toward the end of May, with no word of the twin disasters, he halted at the Arikara villages to trade for pack horses.

Hostilities with the Arikara had begun a few weeks before when the Indians had attacked the Missouri Fur Company trading houses. Several Sioux women, escaped prisoners of the Arikara, had taken refuge there. Two chiefs were killed and several braves wounded in the action, and the Arikaras were sullen.

When William Ashley's boats landed at the village on Oak Creek, in present-day South Dakota, he sensed the mood. But he badly needed horses. Without thought of the consequences, he traded them guns and ammunition.

An uneasy dusk settled that night with part of Ashley's party camping on shore, between the village and the river. During the night, one of Ashley's men, busy sampling the town's "entertainment", was killed. Then at dawn, the Indians devoted some of their new firepower on the camp. Ashley's men were cut down with their own weapons. Nearly all the newly purchased horses were killed, and 11 or 12 men, too.

Ashley retreated downriver and called for reinforcements from Fort Atkinson in Nebraska, and from his partner, Andrew Henry.

Once alerted, Colonel Henry Leavenworth ordered out all the men he could muster to teach the Indians a lesson, and to open the Missouri route west. Altogether, Leavenworth took some 250 men from the fort. Indian Agent Benjamin O'Fallon thought the force insufficient, and appealed to Joshua Pilcher, also of the Missouri Fur Company, who then supplied another 40 men.

On June 22, Leavenworth left the fort. The supplies and some of the soldiers went by river, but most went overland. The river was a torrent; the banks sloppy. One of the Army boats broke in half, drowning a sergeant and six privates.

On the way upriver, the trappers stopped to enlist the aid of the Sioux, who were then at war with the Arikara. About 700 braves joined the force.

Ashley's men and Andrew Henry's party, who had moved downstream, also joined the attack.

Finally, in early August, 1,100 men moved against the Arikara with the mounted Sioux riding ahead. White muslin headbands, worn to distinguish friendly from unfriendly Indian, fluttered. War paint flashed. Arikaras rode out to meet the attack, but the battle was indecisive when the whites finally caught up. When the dust cleared, the Arikaras, except for a few casualties, were inside their village.

Frenzied Sioux taunted the enemy to come out and fight, but though screaming with fury at the taunts, the Arikara remained behind their walls. Leavenworth, meanwhile, waited for his artillery and refused to charge as demanded by the Sioux and some of his own force.

The following morning, bombardment began with a six-pound cannon. Although Chief Gray Eyes and a number of braves were killed, the villagers soon learned to lie flat and let the round shot drop over their heads and into their mud huts. In the midst of the bombardment, the Sioux were busy raiding Arikara cornfields. Leavenworth ordered a charge, then called it off. Bored the Sioux stole 13 horses and mules and left.

Finally, the Arikaras came out to talk peace.

At this point, Leavenworth apparently discovered some conflicts in the purpose and goals of his mission. He changed his policy to one of appeasement, gave the Indians lenient terms, and the peace pipe was passed. Pilcher, however, refused to smoke. Before the conference adjourned, he and one or two other men opened fire on the Indians. The Arikaras fired back, but the fracas was quickly broken up and the Arikaras returned to their village. So began the long, eerie night.

Next morning the treaty was renegotiated. The Indians then said that they could not meet the terms, and Leavenworth gave them another 24 hours. During the night, though, the Indians disappeared.

On August 15, the blushing attack ers started back to the fort. Leavenworth ordered that the village be left unharmed, but no sooner was the military complement out of sight than trappers set it ablaze.

Needless to say, the Indians were not awe-inspired by the whites' military might. In fact, the attacks on trappers continued on and on. It's impos sible to say what the result would have been if Leavenworth's mission had been successful, or if it had been carried out in a different manner, but it was probably a case of expensive error —for all concerned —regardless of where the fault lay.

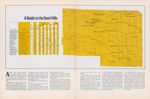

Your Wildlife Lands The Sand Hills

Among the vastness of the Sand Hills' approximately 27,000 square miles are a few precious areas devoted to public use. Besides park areas are wildlife lands, intentionally left much to their own devices, with a minimum of improvements and upkeep. They are lands for hiking and camping and hunting, with many having access to lake or stream. For persons seeking respite from metropolitan trem ors or sheer boredom, these areas can serve as panacea for population pressure. In them, there is solitude and beauty to enrich mankind's spirit

survive the hot dry winds of summer to hold the sand.

Today among the choppies, the Game and Parks Commission main tains a number of wildlife lands where grazing is forbidden or closely man aged. Grass is permitted to grow lush and tall to provide cover for wildlife "crops" that nest and loaf among its plenty.

There are streams for canoeing and fishing, and wildlife areas provide access to them. There is a major reservoir for boating, fishing, swimming and various other water-related activities, surrounded by recreation and wildlife lands. There is a small reservoir surrounded by oak and cotton wood and clumps of wild rose. It is marshes and lakes ideal for waterfowl production and hunting. There is a section of Pine Creek, flowing clear and cold through tree-covered canyons. There is Pressey, located on the Loup River, broken by canyons and smoothed by river valley; and Schlagel Creek, a combination of Sand Hills and creek bottom, with trees and shrubs and grass intermixed.

Wildlife lands, here as elsewhere in Nebraska, receive a minimum of "tending". They are allowed to go their own way as much as possible, all 11,591 acres of them.

There are no facilities to speak of, but tomorrow promises wild plants and animals that are unique. Visitors will lay their fires on the ground, may be in fire rings they have dug them selves; not in firegrates. Campers will pitch their own tents, not plug in their self-contained, jet-age units. Recreation will mean meeting the out-of-doors, not bringing the suburbs to the country.

MOVING SAND. Wind blows sand on sand with a soft tinkle. From the center of a blowout, only distance is visible. Dunes follow dunes, dressed in flowing grasses, to the far horizon, and blue-sky clouds march back to zenith. Sand stings.

Mounds and ridges of sand, held in place by a delicate cover of tough grasses, reach high above the intervening troughs. Here and there, the grass loses its tenuous hold and sand begins moving again. The hills are covered with grass clumps and yucca.

Water oozes in low meadows, form ing little lakes and puddles, or maybe just wet meadows. Here marsh grass is lush, reed canary and bulrush. Flowers and birds change character. Shorebirds and waterfowl are common. Penstemon and puccoons grow in roadside ditches along with purple vetch and leadplant.

In the quiet of a lavender-purple dusk a great blue heron wings slowly across the hills, a black silhouette with neck folded back. It seems he has never touched ground and never will, always remaining suspended between sandy grass and sky.

The Sand Hills have been called the Great American Desert. They have been defamed and avoided like a plague. But their ill reputation kept man away. They were little tampered with for many years after white men began "domesticating" other parts of Nebraska.

The Sand Hills were cursed when cattle disappeared there, never to return. Then an enterprising cattleman rode into the hills to round up the scrawny remnants of his lost cattle and found them sleek and fat among the grass-frozen sand dunes and wet meadows. The Sand Hills became cattle country.

But yet the plow little disturbed the hills, for to break grass cover was in viting disaster. Exposed sand would blow, and no domestic crops could

IN THE PROTECTION of towering sandhills, thousands of lakes and wet meadows percolate from the sandy soil, clear and still, reflect ing puffy clouds and azure sky.

Where water meets land...that's where the coyote and the rabbit come to drink. It's where the greatest variety of plants congregate in quest of life giving water. All sorts of wild animals and plants gather at water's edge. In early summer, blue-winged teal, mallards and shovellers lead their broods among the stalks of cattail and bulrush, barely disturbing the surface of quiet water. Shorebirds wade the shallows in search of insect larvae and snails.

A shunk waddles slowly through the grass, divebombed by a pair of black-and-white shorebirds. He must be very near their nest, for their distress is evident. They nearly dive right into his face, then pull up and circle for another strafing run. Willets —protecting their eggs, or their young. Avocets patrol the lakeside shores There's quite an assortment along the shoreline. Phalaropes, dowitchers, kilideer and maybe a sandpiper or two, wade the water's edge.

An American avocet strides stilt like through the scattering of sedge that claims the inch-deep shallows.

In the lush meadows that creep down from the choppies to meet the water's edge, a handful of Canada geese raise up from their grazing, alert for danger. From a hand-hewn fencepost, a western meadowlark an nounces its territorial claims to neighboring males.

Herons and bitterns cast patient silhouettes on water. Motionless, they wait for minnows, tadpoles or small frogs. Occasionally a human angler will stand as patiently, in the shallows of Goose Lake perhaps, waiting for a northern pike or a perch to nibble on his minnow.

Ballard's Marsh, Big Alkali Lake, Goose Lake, Rat and Beaver lakes and South Twin Lake are all state wildlife lands. Some of them are hidden away in the midst of private land. Access involves driving sandy trails through cattle guards and sometimes lazy beeves. But the end product is the marsh with its fishing and waterfowl hunting, and its trapping for mink, muskrat and beaver.

Decades of adjustment have made

the sandhill lakes into intricate, well

balanced wildlife communities in

which each plant and animal has established its own relationships with

But the web becomes considerably more intricate in view of the total dependence of some varieties of crayfish on the muddy shallows, not for food, but for homes. Crayfish build mud chimneys with tops that clear the surface. Looking down the chim ney reveals the animal inside.

Muskrats, too, use the raw materials of the marsh to build homes; their dome-shaped houses are most often fashioned of cattails. Marsh without plants would be a marsh without rails, even if other food were available, for the rails use vegetation for cover.

Northern pike use marsh vegetation in a different way. They deposit their spawn among the plants, and the young fish hide there to put on their first growth.

Marshes change from day to day, from hour to hour. Small lakes rise and fall. Ducks come and go. Yet it seems that the changes are predictable, not surprising. Tomorrow most of the ducks sitting on this little lake may be gone, heading north. But that's good; it means they'll probably be back sometime in the fall on their way south. Perhaps someone will roast one or two of them.

The Game and Parks Commission's marsh-lake wildlife areas are held in trust, like all wildlife lands. They are places where tomorrow is much like today, and next year will be much the same as this. They are places where change is inevitable, but structured; understandable.

SCHLAGEL CREEK has just about everything. There is the little I creek and many acres of surrounding sandhills. There are cottonwoodsand willows and pockets of shrubs, sumac and buck brush.

The stream bottom itself is almost more wet meadow than creek. Water barely trickles among the rushes and cattails. The little draw is lined with brush and a few trees. Here is an oasis for deer, with browse and water with in a few feet.

A combination of shade from tower ing cottonwoods and cold spring water provide cool mud banks for bullfrogs. Leopard frogs, too, use the damp draw. In sharp contrast, the creek gives way to towering sandhills where skinks rest in the shade of Spanish bayonet, the only shade to be had.

Sharp-tailed grouse feed on rosehips among the hills and perform their courting rituals in spring. The young supply their dietary needs with fat grasshoppers and other insects.

A hike along the marshy stream might reveal myriad wildflowers from Solomon's seal to marsh bellflower. Farther up the slopes are shell-leaf penstemon, spiderwort and hoary puccoon. Yellow-headed and red winged blackbirds add color to the lowlands, and cowbirds, grackles and kingfishers nest or feed in nearby fields or stream banks.

Wind rustles willows and cotton woods and dry bunch grass that have gone to seed and now lie yellow and dormant, waiting for cool, spring rains to green them again. A lone hiker stalks the creek's edge, looking for signs of deer; for a trail. He eyes the hills knowingly, mentally picking a spot. His imagination breaks his man outline just under the hill-crest. In his mind's eye he watches himself lying quiet, rifle ready. A big buck browses warily along the creek toward him. He tenses; braces... yes, that's the spot. In the fall he will be ready. Schlagel Creek is his spot.

SHERMAN RESERVOIR is the child of two outdoor recreation philosophies, and is divided between recreation area and wild life land.

Portions of the lakeshore have received intensive development, including boat ramps, picnic tables, rest rooms, drinking water and so on. Still, there is room for wildlife at Sherman, too. The undeveloped "left overs" from recreation areas have been turned over to the management of the Resource Services Division. These are the wildlife lands.

Waterskiers and boaters use ramps on the recreation area and the lake's center, but the avid fisherman is likely to prefer the lake's upper reaches where water is too narrow and shallow for power boats to maneuver, and dead trees and weeds are permitted to stand along the shore. That's where the fish are.

Around the lake, on the hills and in the shrub-filled draws, are pheasant and quail hunting. Deer browse the buck brush and willows. Concentrations of ducks rest on the lake each fall and spring.

Access to much of the lake is limited. Trails are few and walking is the best way to approach the water. But walking kicks up game birds, and only the man on foot can really see even a tiny portion of the "happenings" among the grass and shrubs. There's a bud of poppy mallow opening; here's a rabbit's nest, empty now; over there a mourning dove is about to hatch in a grass-hidden nest.

The leftovers at Sherman provide a closer look at the wild world; more primitive, satisfying outdoor experiences.

SOME WILDLIFE lands are small; just a stretch of sand beach and I river frontage, or maybe just the river and a few trees. They're a place to get to the water and catch fish, or a place to put a canoe in the stream.

Spencer Dam and Borman Bridge on the Niobrara, and Milburn and Arcadia diversion dams on the Middle Loup River, are such places. All claim good catfishing, with sauger, carp, bullhead and a few bass in addition on the Niobrara.

The Niobrara runs through the Sand Hills, clear and swift; exciting canoe ing water. Rustic Borman Bridge on an area of the same name, marks an easy landmark for taking out to avoid obstacles just a short stretch down river. The area was taken over from the federal Bureau of Land Management for administration by the Game and Parks Commission. It's a bit of riverbottom land that is being held in trust for a time when public lands and river access may become shorter in supply than they are even now.

Spencer Dam is a popular starting point for canoeists, and a deep hole below the old dam attracts fishermen. The spot has an added attraction in its sand beach and the small, grassy, tree-shaded area where a camper spends the night occasionally.

Milburn and Arcadia diversions seem to have been created especially for the ring-of-baloney and loaf-of-bread catfisherman. Here is a place where a man can park his car, set out his bank lines, then nibble sandwiches and snooze until something happens. When the baloney and bread run out, it's time to go home, limit or nothing. Deep holes below each of the old structures have yielded many a catfish to the patient fisherman who has nothing better to do (for a few hours at least) than watch the Big Dipper and unscramble his thoughts. And, for him, the tinkle of an old turkey bell might at any minute signal some excitement—perhaps a Master Angler, or maybe even a state record, catfish.

Photograph by Lou EllThe juncture of water and land. It's a place of excitement where some thing might happen any second. A canoe might upset, a big fish might bite, a sunbather might be drenched in a sudden shower. Limitless outdoor experiences can be had through simple access to the rendezvous of water and land. This is the essence of the wildlife lands, to bring together man and the remaining parcels of Nebraska wilderness.

A BLACK LAB plunges through tall prairie grasses, the sun striking blue on its coat. A man and his son walk behind the dog, the father giving occasional in structions to his boy. It's the boy's first hunt.

Suddenly the dog acts birdy. His master moves up behind him as his father had taught him before the season began, and finally the cock flushes upward, brilliant feathers flashing and the cackling adding to the excitement.

The boy fires, only rumpling a few tail feather Sumac flames on the youngster's disappointment as he groans that he forgot to lead the bird.

The father grins. "I've done that a few times, too, son."

"No kidding?" the youth asks hopefully.

"There will be plenty more pheasants," his father promises.

Spirits cannot be crushed for long, and in a few moments the sunlit, fall smelling day and the dog working take their effect on the boy.

Walking the quaily draws and nearby food plots on Pressey have provided learning experiences for more than one boy.

Pressey is on the South Loup River and encompasses acres and acres of surrounding canyons and grasslands. It is about 1,000 acres of grassland with canyons and ravines that conceal pockets of pheasants and quail. Rabbits range through the grassland and along the 600 acres of riverbottom. An occasional grouse also uses Pressey.

Peering down from canyon rims, visitors can almost always find a deer nestled in a pocket along a far wall. Sometimes a buck can be caught off guard, browsing in a ravine.

The Loup River flows constantly and slowly through the area. Fisher men work the holes there for catfish, bullhead and carp. Here, too, is an access point for floating the river.

The wildlife area was willed to the Game Commission upon the death of its former owner, A. E. Pressey, with the proviso that it be developed and used for public recreation or propagation of wildlife and fish. Pressey's death left some 1,600 acres in trust for the people of Nebraska. Along with the acres of wildlife habitat, Pressey left the remains of his homestead, an extensive flower garden and an or chard on the riverbank. All are gradually becoming part of the natural wildlife community.

A red-tailed hawk sails over the area, his view encompassing vast chunks of land contour —flatgrassland broken by canyons, riverside thickets of trees with an understory of shrubs, weed-choked draws. Yet his vision is narrow, seeking among the bunches of prairie grass for some small rodent.

The hawk's circling glide is part of the changeless, everchanging world of the wildlife lands that are scattered throughout the Sand Hills as tomorrow's legacy.

BREEZELESS silence grips the small lake. It mirrors bowers of wild rose against the vibrant green of bur oak. The surface is broken only occasionally by the movement of a turtle or a bullfrog. Tiny toadstools nestle under the trees.

Then the quiet is broken by the plop of a popper dropping on the water's surface, and again by the strike of a largemouth bass rising to investigate. A man might take his granddaughter and grandson to Hull Lake to fish. The quiet would most likely be shattered then by delighted squeals and chatter.

Children might poke around in the shallows with a stick, disturbing crayfish and waterbugs. Shiny schools of minnows might flash along the shore line, swimming in synch as though guided by one central nervous system. Or tadpoles might catch youthful at tention as youngsters wait for their bobbers to dip under the surface.

Squirrels could answer the children's chatter, or their investigations might turn up a nest of young rabbits — wild cottontails carefully hidden away by their mother. Or perhaps they would occupy themselves with answering the strange whistles of bobwhite quail.

In the fall, when oak leaves burn red and the air smells of musty smoke dust, a hunter might try the grassy slopes above Hull Lake for grouse. Hull Lake is grouse territory, and the alert birds range along the fringes of the public land. Squirrel hunters, too, and rabbit hunters find game on the wildlife area.

Come winter, snow drifts to the surface of the frozen lake, protected in the shadow of the hills from blustering wind. Then cottontails and raccoons, and maybe an opossum or two, leave tracks in the smooth surface of the snow, along with those of varied song birds and quail. The story of lakeside life is there to read; tales of struggle and just day-to-day living.

Then, with the new flush of spring, a jay's raucous scream pierces the pleasant stillness of the lake. The cycle of bullfrogs and fish, rabbits and squirrels, booming grouse and war bling songbirds, begins again.

Hull Lake is a small place, just a ravine that's been dammed to hold some fishing water. Its stature is amazing, however, as a place for varied wild creatures to make their dens and nests. It's a good place to visit the wild plants and animals that surround men's activities.

STANDING ON THE Pine Glen canyon rim, a solitary man I scans the stream below. He hikes to the creek, bucket in hand, towel over his shoulder, a fly rod in the other hand. Stripping to bluejeans, he immerses himself in a deep hole and permits the current to wash away the day's grime and exhaustion, then fills his jug, buckles on a belt, and wanders aimlessly up stream, flyrod in hand.

A log crosses the stream, with a deep hole below and an overhanging bank above it. Quietly, aimless move ment takes purpose as the man steals to the bank's edge. A homemade fly arches gracefully to the surface, twitches, and begins to drift. Silver sides flash in the waning sunlight as a trout sucks in the bait. A few moments' play and he gasps exhausted in the grass.

Drawing a knife from his belt, the man cleans his trout, soon adds an other to his small cotton sack, gathers his gear, and climbs thoughtfully to camp, moccasins sinking deep into pine needles.

Back on the rim, he startles a white tail doe and fawn that plunge down the ravine to the south. He sees them in slow-motion, knowing that their leaps span many feet. In an instant they will disappear; in a moment their crashing rush will be silent....

Pine Glen wildlife area near Bassett is many things. It's canyons and Sand Hills grasslands; it's a cold, running stream and hillside meadows; it's dawn-frosted dew on spiderwort and little bluestem; it's turkey vultures and songbirds; whitetails and mulies; bullfrogs and skinks and bullsnakes. Pine Glen is large —an entire 960 acre tract that encompasses several land features. In an area where spaces seem wide open, there is little public land. Pine Glen offers a large parcel for all sorts of outdoor activity.

Sitting under a pine tree on the canyon rim is like hanging in space. A turkey vulture circles within a few yards —hundreds of feet above the creek, yet eyeball-to-eyeball with a hiker.

A sunrise in June begins to wash the morning chill from damp air. Crystal dewdrops compress drops of sunlight and sparkle like liquid jewels. Each stem of grass bears a frosty coat ing of moisture. Somewhere on an eastward-facing slope, where wind has bent the grass, a snake lays coiled, absorbing sunlight into his cool hide. Everything is still.

Later, as the sun arcs upward, the frosty grass seems to melt, its sparkling grandeur of morning pales to a lustrous sheen, then to dry, afternoon green. And, when setting, the sun throws glittering ripples from the stream's surface to the canyon wall. The creek blazes.

Fall brings flame to creek bed and canyon walls. Red vine and oak mingle with yellow and gold of ash, elm and cottonwood, and the flaming colors lick at an interspersion of ponderosa pine and redcedar.

Sumac and buck brush provide a rich understory for the trees. A confusion of wildflowers from daisy fleabane to ball cactus line the creek banks and canyon walls.

Buck brush, plum and low junipers crowd the steep valley slopes, and it's from these thickets that bobwhite quail make their clear, morning call in spring. Deer browse the shrubs, leaving sign throughout the area along well-used paths where hoofprints are plentiful.

Silent summer nights are broken by the howls of coyotes and the impossible croak of bullfrogs, sounding like nothing animal at all. Vast hordes of songbirds conduct their various business in the scrubby thickets —twitter ing, warbling, and cheeping—catching grasshoppers and feeding their youngsters.

Pine Glen is new to the Commission, only recently purchased as the result of an offer from the former land owner. Croplands still break the can yon rims; milo and corn for deer and quail to feed on.

Pine Glen is many things to many people. To some, it's a natural cathedral where a jeep track is blas phemy. To others it is a zoological or botanical laboratory where plant and animal habits and interrelationships can be studied. To a hunter it's the challenge to meet a deer on a steep canyon wall. For a fisherman, it's trout. For a camper or hiker, it's the original of an oil that he paints himself into. It's solitude to gaze into a camp fire and discover oneself.

This publication is made available through funding supplied by the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act project W-17-D and the Ne braska Game and Parks Commission. Extra copies can be obtained from the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Photographs by Jon Farrar

MUSKIES IN THE MAKING

Trial releases in two Sand Hills lakes could provide anglers with supply of hefty, scrappy opponents

A FEW THOUSAND fish in a couple of Sand Hills lakes might be forming the basis of a brand new sport fishery in Nebraska. Those waters are Long Lake in Brown County, and Duck Lake on the Valentine National Wildlife Refuge. And the fish involved are brawlers that excite trophy fishermen everywhere at their mere mention — muskellunge.

Whether or not muskie fishing is on the horizon for Nebraska anglers will be determined at these two lakes in the next few years, as the Game and Parks Commission attempts to establish populations there. Long Lake was stocked with 13,000 muskies of an inch or less in June of last year, while some 1,100 in the 8 to 10-inch range were released in Duck Lake in August of 1972. If these muskies survive and grow to adulthood, the Commission will have a source of eggs to propagate in its hatcheries for stock ing selected waters throughout the state.

There is a chance that the fish in Duck Lake might have reached maturity this spring, and could provide some eggs this year. However, it is more likely that first production will come in 1976. As for the fish in Long Lake, they should reach maturity in 1977 or 1978.

The muskellunge should be welcomed by Nebraska fishermen, since it is considered the ultimate trophy in freshwater fishing. The muskie resembles his cousin, the northern pike, but he outdoes the northern as a sport fish in many ways. The muskie grows bigger, and is much more difficult to coax into striking. But when he hits, he does so with a vengeance, and fights with abandon.

The muskellunge is not a native of Nebraska, but of more northerly waters. However, some states have had success in introducing them beyond their normal range, so it might pay big dividends in Nebraska to proceed with the experiment.

Muskellunge are not exactly new to Nebraska. A very few are known to exist in Merritt Reservoir, where anglers have been taking a handful each summer the past couple of years. These fish came from an earlier Game and Parks Commission attempt to propagate muskellunge that failed.

That program involved keeping adult muskies in a hatchery in hopes of collecting spawn from the captive fish. True to the temperamental reputation of the species, these fish threw a monkey wrench into the operation. They simply did not produce ripe eggs in captivity. But when the program was abandoned and the 50 adult fish released into Merritt Reservoir, they apparently spawned.

Just which Nebraska waters, if any, will support muskie fisheries remains to be determined. They might make it in some Sand Hills lakes, although their native waters are deeper, and offer cooler waters in the summertime. Perhaps muskies might find a Nebraska home in some of our medium-sized or large reservoirs. That is where transplants in other states have fared the best.

Even if the Nebraska program is successful, fishermen should not expect large numbers of muskellunge. These fish are never numerous, even in their home range. Rather than providing many decent-sized fish like the northern pike does, muskellunge will number very few in any lake, but those few fish will be big ones, real trophies.

This is why fisheries biologists do not expect any trouble from introducing muskies, such as their crowding out established game species like the pike. Pike have proven very capable of competing with muskies, probably due to their less finicky feeding habits, and because of their willingness to tolerate the company of their own kind. Muskies, on the other hand, are characteristically brooding loners who stake out a territory for their very own. This is what keeps muskie numbers low in any given lake, low enough that they do not have a visible effect on its food chain, and therefore do not significantly affect other game fish populations.

However, a couple of hurdles still remain. The most immediate is the mere survival of the muskies in the two lakes. At Long Lake, winter kill threatened the fish because the preceding dry summer had lowered water levels some two feet. But, whether there is winter mortality or not, the muskellunge program will continue, as additional stockings of muskies from federal hatcheries are planned for the lake in 1975. Fishermen at the two lakes could help immensely by releasing muskies caught there the next few years.

Of course, Nebraska muskie fishing is quite a few years in the future, or it might not be in the offing at all. It all depends on what happens at Long and Duck lakes. But the plan appears sound, having been proven with other species of fish. Northern pike and walleye taken from wild Nebraska populations have provided more than enough eggs for Nebraska's hatch eries, with enough left over to supply those of several other states. Populations of muskellunge at Long and Duck lakes would offer the same potential, eventually offering muskie fishing for Nebraskans.

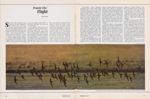

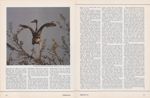

Prairie Life/ Flight

SINCE THE FIRST meeting of man and bird, we have coveted the gift of flight. Only in this century has man been able to shed his terrestrial bindings, but still we are envious of the unbound elegance with which birds ride the wind. When we watch a tern hovering effortlessly, a vulture spiraling upward on a warm air thermal or the capricious flight of a warbler through riparian tangles, we recognize the crudeness of man's metallic wings. The mystery of flight is still very much with us. And, though we are yet unable to duplicate the in tricacies of bird flight, we know much of its mechanics.

Fossil evidence indicates that the first bird-like creature evolved from a groveling reptile some 150 million years ago. One theory suggests that these "flying reptiles" took to the air by running along the ground flapping their front legs, much like a common barnyard chicken. A more likely the ory proposes that these bipedal reptiles began their aerial life clambering about in trees, jumping from limb to limb, and eventually gliding for short distances. Whichever, flight, in this pro-avian reptile, probably evolved to exploit an untapped food source — arboreal and flying insects — and to aid in escape from terrestrial predators. With the ability to fly, birds reaped many other benefits: seasonal migration became possible, permitting birds to utilize uncrowded breeding grounds and temperate wintering areas; traveling became easier, as rivers, mountains and even oceans were no longer impassible barriers.

Transforming a bulky, terrestrial quadruped into a lithe, aerial biped required millions of years and some very basic anatomicaF changes. To permit sustained flight, two gross alterations were necessary: an overall reduction in weight, and the develop ment of muscles powerful enough to propel the body through the air.

To reduce the weight-to-body-surface ratio, evolving birds developed hollow bones and replaced the reptilian scales with light, yet structurally strong feathers. Heavy teeth and jaws were eliminated, and many bones were fused or completely lost. Skin glands were reduced in number and the weighty gonads decreased in size during the nonbreeding season. To reduce the weight of heavy, fluid filled bladders, dry uric acid, rather than urine, was excreted.

To power the lightened body, birds evolved a four-chambered heart that offered double circulation of the blood, a highly efficient respiratory system with auxiliary air storage in the hollow bones, and breathing synchronized with the movement of the wings to increase air exchange. They evolved a higher rate of metabolism and gradually switched to an energy rich diet to feed it. To allow year around activity in temperate climates, they evolved heat-conserving plumage and eventually became warm blooded.

Almost any object can be propelled through the air given a sufficient force behind it, but it takes wings to truly ride the wind. Without them, the most sophisticated of anatomical adaptations would not lift and carry a bird through the air. The story of flight, then, is really the story of wings.

Just as a weather vane turns to present the least resistance to the wind, so the shape of a bird's wing, in fact its entire body, is designed to cleave the air. In cross-section, the wing is teardrop or fusiform shaped. A perfectly symmetrical wing would push air equally from both sides. A bird's wing, though, is concave on the underside and convex on the upper, creating more pressure on the under side and a partial vacuum above. The result is a lifting force, making flight possible.

When air passing on the underside reaches the back of the wing, it is drawn up into the partial vacuum and creates turbulent eddies that disrupt air flow efficiency and lift. This turbulent air is at its strongest at the wing tips. The greater the distance between two wing tips, the greater the length of wing undisturbed by turbulence, the more minimal its disruptive effect. Consequently, long slender wings are the most efficient flight structures, and birds with them do not work as hard to remain airborne.

Short, stubby wings, such as a bob white quail's, are necessarily less ef

Photographs by Jon Farrar

ficient because eddies of air cause turbulence over the entire length of the wing. They are, however, strong and capable of propelling the bird rapidly for short bursts of flight.

The ratio of body weight to wing area, wing-loading, is another factor that influences a bird's efficiency in the air. The larger the ratio (the larger the wing surface relative to the body weight), the more efficient flyer the bird. A barn swallow weighs about one-half ounce and has over 18 square inches of wing surface. On the opposite end of the scale is the pied billed grebe, weighing over 10 ounces but with only 45 square inches of wing surface. If the swallow's body were as large as the grebe's, it would have over 350 square inches of wing area —over seven times more than the grebe.

This is not to say that the swallow is a better bird than the grebe. The swallow has evolved to glide through the air and capture insects on the wing. For that lifestyle, it is well designed. The grebe, on the other hand, spends much of its time diving for food in shallow water. Short, powerful, paddle-shaped wings are requisites for this aquatic life. The swallow would be just as ineffective diving for fish as the grebe would be pursuing insects in the air.

One would expect large birds to have proportionately larger wings than smaller birds, but such is not the case. As a rule, larger birds have less wing area relative to their body weight, hence, heavier wing loads. Large birds such as the trumpeter swan and turkey vulture, are probably near the upper limit in size and weight. Were it not for their ability to extract the energy of air currents, they could barely stay aloft.

As a rule, short, stubby wings are found on birds adapted to wooded habitats. Broad, powerful wings provide the slow, controlled flight needed to maneuver in close quarters. This type of wing is typical of perching birds; doves, woodpeckers and most gallinaceous species.

Long, slender, streamlined wings are characteristic of fast-flying birds that either make long migrations or capture prey on the wing. Often their wing angles back from the body, a design recently adopted by designers of "swing-wing" fighter planes. Falcons, swallows and most shorebirds are good examples of this wing type.

Yet a third type is found on heavy soaring birds, such as hawks, owls and the turkey vulture. These birds spend much of their time riding air currents in search of food. Typically, their wings are broad and deeply concave to provide maximum lift.

While wings provide most of the uplift and power for bird flight, the tail is also an important flight structure. Wings are generally attached to ward the front of the body, so the tail becomes responsible for buoying up the rear. Generally, the tail is slightly concave, like the wings, to provide uplift. In addition, the tail aids in steering, balancing and braking the bird. It is the bird's rudder.

The design of the tail, just as the design of the wings, is specialized to meet the needs of its owner. Insectivorous birds, that capture their prey on the wing, characteristically have long, elaborate, often notched tails that aid in rapid aerial maneuvers. Birds that must negotiate brushy tangles generally have relatively large tails. Fast flying birds and birds of open country, such as ducks and grouse, typically have short, stubby tails since sharp turns and aerial gym nastics are not part of their flight habit. Predatory birds, such as the hawks and eagles, that carry their prey in the talons, have broad tails that may help to buoy up their loaded hind quarters.

Flight can be accomplished in a number of ways, but for convenience could be lumped into two broad groups: soaring flight and flapping flight. Most birds are capable of both but are adapted to one or the other.

Gliding was probably the original means of flight and soaring could be thought of as a sophistication of it. Gliding is simply a matter of present ing enough resistance to air to slow a plummeting descent. By definition gliding is always accompanied by a loss of altitude.

Soaring, on the other hand, permits a bird to maintain or even increase its altitude. Soaring is simply gliding through air that is rising at a speed greater than the speed at which the bird is sinking. The bird is thus carried upward and attains an altitude from which it can later glide through air that is not rising. Soaring birds characteristically are of a rather larger size to carry them through turbulent air currents without appreciably disrupt ing their flight, and have light wing loading to minimize the amount of air current needed to keep them airborne.

Birds that soar over land ride two types of air currents: obstruction currents and thermal currents. Obstruction currents result from steady winds striking and rising over natural obstacles such as hills, canyon walls or a line of bluffs. Thermal currents result from uneven heating of the air near the earth's surface. Air over bare fields, especially plowed land, or cities, heats faster than air over wood land or water and rises in columns or bubbles. Thermals may also occur when a cold front slides under warm air and forces it to rise.

To ride an obstruction current, a soaring bird tacks to and fro across the wind, always remaining above the windward slope. To ride a ther mal, soaring birds spiral upward in the rising warm air. Once the bird has attained some height by one of these currents, it may glide for miles before climbing another current.

Flapping flight, unlike soaring, is largely at the expense of body energy. Although birds like the grouse, bittern, owl or other nonsoaring birds are buoyed up by their wings and tails, all must expend considerable energy to flap their way from place to place.

Strong, flapping flyers do not simply swim through the air as many be lieve. Actually, they are propeller driven, on the same basic principle of a prop-driven airplane. On the powerful downstroke, air pressure twists the more flexible back of the wing upward, pulling the entire bird forward, propeller fashion, through the air. At the end of the downstroke, the tips of the wing are level with the bill. On small birds with light wing loading, the return stroke is upward and backward, with the primary feathers separated to permit easy passage of air. This recovery stroke does not help propel small birds. On larger birds, with their slower wing move ment, too much time is lost in the recovery stroke. So, to make efficient use of each cycle, their wings go through a complex series of move ments that allows the primary feathers to push against the air on their return stroke and help propel the bird forward.

The rate of wing flapping is general ly the inverse of a bird's size. Chickadees beat their wings about 30 cycles per second. Ducks, hawks, crows and shorebirds have about two or three wing beats per second. Large birds of prey and wading birds, like the turkey vulture and great blue heron, may beattheirwingsonly once per second.

Though it is never as difficult to get back onto the ground as it is to get airborne, landing can be more treacherous. Unplanned landings can be just as destructive to a bird as it can be to an airplane. To slow their land ings, birds swing into the wind so that their spread wings and tail act as a parachute. Water birds even spread their webbed feet. Just before landing, they beat their wings to create as much resistance as possible. Land birds must be more expert at setting down than waterfowl, since they lack a watery cushion.

Despite the disadvantages of life in the air, flight opened a completely new world. Since that first gliding reptile took to the air, birds have diversified to tap every available living space and food. To earth-bound man, it will always seem that birds have the best of both worlds.

HUNTING DOG HEAVEN

DUKE WAS ON POINT at the end of the hedgerow and Pam was 30 feet behind, backing him. Daryl and I walked up, and with a cackling that is music to a pheasant hunter's ears, a big rooster came out at top speed. We waited until he had leveled off, then one shot from Daryl's 12-gauge pump and Duke's retrieve put Number 9 for the day in our bag.

Leaving Birmingham, Alabama and heading west to Memphis, then north along the banks of the "Father of Waters" to St. Louis, west again by way of Salina, Kansas to Kearney, Nebraska in a station wagon with two fine young dogs had come the three of us, anticipating four days of great hunting in the heart of Nebraska's pheasant country. Two of us were pastors of adjoining churches in Birmingham; I, pastor of the 85th Street Baptist church, and Daryl Jones of the Roebuck Park Baptist church. The third in our party was my son, Bob, an attorney with offices in Birmingham, but we were going to hunt with Rev. Irvin Burlison, pastor of Immanuel Baptist church in Grand Island.

Bob and I have four fine bird dogs that we raised and trained. Our state has some of the finest quail hunting in the world, but no pheasant, so for 24 years we have loaded up our dogs and headed to pheasant country.

Many people have asked me questions about using quail dogs to hunt pheasants; "Will they work pheasants?" "Since a pheasant usually runs and doesn't hold like a quail, won't this ruin your dog for quail?" I'm sure I have been asked no less than a hundred questions along this line. On this trip we only carried two of our dogs-Pam, a pointer, was three years old in January, and Duke, an English setter, was three years old in June. Even though they would "do it all" on quail, they had never seen a pheasant.

We stopped about every 200 miles to let the dogs run for a few minutes. When we reached Nebraska we found a plot of C.A.P. ground that looked good. Almost as soon as the dogs were on the ground they started working, and within 10 minutes put 2 roosters in the air.

Just a word regarding dogs: we have used our dogs all these years on all types of upland game birds. Any well trained dog will handle any of these and it will not affect him in any way on other birds.

We had made our plans ahead of time and had motel accommodations in Kearney, but planned to hunt in the Wilcox area. Since it is always best to know something of the area, we arrived a day early and scouted.

A nice C.A.P. field covered with weeds seemed to be a favorable place since corn and milo were all around it. We put Duke and Pam on the ground to exercise and it was only a few minutes until we found plenty of birds. We decided this would be the place to open our season the next morning.

We could hear crowing as dawn began to break, and the urge to get started was almost overpowering. We NEBRASKAland had hardly left the road when Bob and I doubled on a rooster that he almost stepped on. This signalled others, and birds began to break cover all over. Most were out of range, but we did manage to down three with Burlison killing one so far away we de cided he had strained his gun. Pam and Duke were in "Dog Heaven"; not only did they bring our birds to us, but Duke picked up two cripples for other hunters.

Most of the birds had flown to the corn, so that was our destination. Keeping one hunter at the end of the corn to get the birds that would run or fly, we soon had shooting again. Pam was getting too close to some birds for comfort. Several hens got up and then a rooster; my first shot got feathers but the second was on target. Burlison was at the end of the rows and getting his share of action. When Bob went back to get the station wagon to meet us at the end of the field, it sounded like he got involved in a private war, as he walked into two roosters along the edge of the field. Two more had been added to the pot when he picked us up. A swing through another small corn field and some beautiful teamwork by the dogs produced one for me and one for Daryl before Number 9 was encountered at the hedgerow.

We planned on having our noon meal on opening day with the Lions Club at Wilcox, and after bagging Number 9, we thought it was about time to eat. We planned on hunting in another area after lunch that our hunting partner, Rev. Burlison had suggested. To just call it a noon meal is not appropriate; it was a feast. This fine organization has hunting rights on several thousand acres of choice land and sells season permits for $5 to support worthy community projects. The men and women join hands to prepare the meals, and I can truthfully say that the food and fellowship are unsurpassed. And, only a short while after lunch, we all had our limits.

Monday morning was cold and windy with light snow. We went back to the weed field where we started Saturday. Hunting with dogs is always better after opening day. The birds hold better, partly because they are usually in heavier cover. We had added another member to the party; Clyde Blythe, a plumbing contractor, who had flown in from Birmingham Sunday night. Both dogs worked into heavy weeds and pointed; two roosters burst out in opposite directions. I dropped one and Burlison the other. We had hardly taken a dozen steps until another took off against the wind. He looked like he was standing still as Bob "one-shot" him.

One of the nicest game wardens I have ever met came to our motel room Sunday night and brought Clyde's hunting license. He stayed and visited awhile and told us of an area that was primarily for waterfowl, but due to lack of rainfall, most of the area was out of water and pheasants had rather taken over. We headed to the area and found the largest concentration of birds I have ever seen. A milo field running along the road and adjacent to the waterfowl area was our starting point. Burlison, Clyde, and I started through it with the dogs. Bob drove the station wagon down the road to a point where we would end. He and Daryl positioned themselves where they felt birds would fly out as we pushed through the milo. The dogs struck immediately, but the birds were apparently running. However, when they got nearer to where the blockers were standing, they started veering off in other directions. Pam finally pointed, and soon a young rooster got up. He didn't bother to cackle, and with the sun shining on him, I almost let him get away before Daryl yelled for me to shoot. When I dropped him, another rooster got up behind me and was heading to Kansas when Clyde winged him. It took both dogs quite a while before they finally found and retrieved him. Bob had dropped a long shot, and so had Daryl. I got an other one that was trying to sneak into the grass along the road, but Duke cut him off, made a nice point, and finished the episode with a good retrieve.

We hunted four days; Saturday, Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday. We did not limit every day, but could have if we had tried harder. The dogs needed some rest, so Tuesday and Wednesday were mostly early morn ing and late afternoon hunts. We had some excellent shooting Wednesday morning in a large cornfield. Clyde and Daryl were at the end of the rows; Bob and I and the dogs worked toward them. Each of the four of us got a bird. They downed theirs with no difficulty, but again, the dogs had to work for a good half-hour before Duke routed my rooster from a drainage ditch and brought him to me.

Another of our many experiences which I feel was unusual happened in a cornfield which looked good, so Bob and I started through it toward the blockers. There was a man-made lake of about a half-acre at the edge of the field with heavy weed growth all around about 20 feet wide. The dogs worked toward the lake and we knew the birds had made their way to the water and weeds. They pointed, and a big rooster got up. Bob and I doubled on him and thought he was dead, but to our surprise, when the dogs should have retrieved him, they started trail ing instead. About halfway down the lake our doubly winged rooster jumped into the water and started swimming across. I never knew until then that a pheasant could swim. Pam jumped right in after him, but decided better when she discovered the water was cold and deep. Bob sent Duke around the lake and soon had a wet rooster in his bag.

We always enjoy our pheasant hunts, but Nebraska is by far the most cordial state in which we have hunted. The citizens go all out to make visitors welcome. They will gladly tell you where birds are and it is no trouble to get permission to hunt.

So, to you Wilcox Lions —be sure to reserve two pieces of that wonderful apple pie for next opening day; Bob and I will be there. On second thought, better make it three, as my wife says it sounds too good to miss and she'll be there also.

YOUTH CONSERVATION CORPS

(Continued from page 8)ecologically and recreationally. But let's go back more than three years....

Public Law 92-597 established in the Departments of the Interior and Agriculture a program designated as the Youth Conservation Corps. The purpose of this act is to further the development and maintenance of the natural resources of the United States by the youth, upon whom will rest the ultimate responsibility for maintaining and managing these resources for the American people. The Departments will stress three equally important objectives as reflected in the law:

(1) Accomplish needed conservation work on public lands.

(2) Provide gainful employment for 15 through 18-year-old males and females from all social, economic, ethnic and racial classifications.

(3) Develop an understanding and appreciation in participating youth of the nation's natural environment and heritage.

And so it started —a three-year pilot program that has been so successful that it has been continued. Three years ago the Bureau of Reclamation contacted McCook Community College officials to inquire if the college would like to sponsor a YCC camp for the summer of 1972. The program sounded exciting and the challenge was readily accepted by the college.

A busy time —contracts to sign, plans for the camp operation, staff to hire, corps men to recruit, food planning, recreation, dormitory facilities, transportation, safety planning, and above all, planning work projects.

All work has to be accomplished on federal lands, and in southwest Nebraska we are lucky to have four federal reservoir areas that are controlled by the Bureau of Reclamation. The Nebraska Game and Parks Commission manages these areas for maintenance, wildlife management and recreational facilities, there fore, the Game and Parks Commission became the third factor or partner in the establishment of the camp. It is called the cooperating agency, and as such has helped plan the work projects, supplied materials and equipment such as tractors, trucks, etc., and have supplied technical assistance. The man involved the most has been Mel Grim of McCook, who is the park superintendent for the southwest reservoirs. Our direct link to the Bureau of Reclamation is a permanent employee who is called the project coordinator, whose name is Charles Pilcher.

These two men have been largely responsible for the planning of all of our work projects in Nebraska. These areas 42 are Enders Reservoir, Swanson Lake (Tren ton Dam), Hugh Butler Lake (Red Willow Dam), and Harry Strunk Lake (Medicine Creek Dam). We also travel to Norton Reservoir in Kansas and work with the Kansas State Park and Resources Author ity and the Kansas Forestry, Fish, and Game Commission.