NEBRASKAland

January 1975

Speak up

Thanks But NoSir / I was overwhelmed with the response I received from native Nebraskans. I can't find words to express my thanks except to say "Thank you".

To Mrs. S. E. Salzman, I'd like to thank her for her generosity. I know it makes life easier to have such thoughtful persons as Mrs. Salzman. Maybe someday I can in turn help someone, like she helped me.

To the people who responded to my plea, I can only say that it was not I who returned your magazine or books you have sent me. I only received a notice stating I couldn't have them and they were being returned to the sender. Institutional rules, they say.

I want to send my hearty thanks to each and every one of you. May the Great Spirit watch over you and yours.

Samuel Freemont B-33103/2370 San Luis Obispo, Calif. 93409Mr. Freemont is an Omaha Indian, a former Nebraskan, now in prison in California. He had written Speak Up earlier asking for a subscription to NEBRASKAland, and several people responded. Now, he apparently cannot receive it for some reason. We will mail the magazine to the library there, as one of the donors was anonymous and we cannot refund the money. (Editor)

Fish Near HomeSir / I am writing this letter to accompany my application (for Master Angler Award) because of the circumstances surrounding the fact that I was fishing at Branched Oak in Nebraska on October 15, 1974. It will tell you that your efforts to improve fishing in Nebraska are bearing fruit. I am recognizing that I can stay home and enjoy consistently better fishing.

For several years we pulled our trailer to Minnesota in September. This year we were near Alexandria for five days. During that period because of windy conditions I managed about four or five hours of fishing. My reward was two small walleye, one small northern and one perch. Although we planned to remain longer, I decided to take my chances at Branched Oak. We arrived there after noon on Friday, and after about one hour of fishing and a couple of nice fat bluegills, I got blown off the lake. Saturday morning I got in about one hour of fishing before the rains began. It was at that time that I caught the 10!/2-pound northern that produced this letter and application.

The facts that impress me are the comparative fishing results. Four or five days versus two hours and the results are certainly favorable to our Nebraska fishing. No one can control the weather, however successful fishing first requires that there be fish in the lake.

I might add that I caught a four-pound walleye at Branched Oak in early September, plus some crappie and fine blue gill. My fishing success tells me that your people are doing a fine job. I suspect that I shall devote more time to fishing here than in Minnesota.

Ralph Thornton Omaha, Nebraska Beauty and BullheadFollowing is a short story by Bruce Condello, a 6th grader last year at Kahoa school in Lincoln, pupil of Mrs. Connie McElvain.

In the kingdom of Holmes Lake there was a beautiful channel catfish. Her parents wouldn't let her go out on dates because all the men were too soft. Once the pretty fish went out to eat and saw a beautiful worm. The only thing she could do was eat it. All of a sudden she felt a barb and knew she was being caught. Right before she was landed, a handsome young bullhead saved her. The bullhead was so strong and handsome it was love at first sight-he was more irresistible than the smelliest dough bait. Even though she knew her parents wouldn't like it, she brought him home so he could meet them. She was right-her parents didn't like it at all, and they kicked him out. The beautiful channel catfish couldn't take her mind off her love, and all day she cried. Finally her parents gave in and gave permission to date him, and finally they got married and had a honeymoon at Lake McConaughy and had many channel cat-heads and lived happily ever after until the beautiful catfish ran away with a handsome young muskie.

SOLO FOR SQUIRRELS

Tactics of patience and stealth pay off when after bushytails—if you can hit them when seen

THE WARMING RAYS of the mid-morning October sun felt good as I stepped out of my car and walked the short distance to a brushy draw. A hard freeze a few days before appeared to have set the trees in the creek bottom on fire. The reds and yellows of the oaks, cotton woods and ash presented a spectacle unmatched by anything man-made.

It was good to be out but I knew the colorful leaves would work against me in my search for fox squirrels. Anyone who has seriously hunted them knows how they can disappear in a hurry when they reach the safety of a tree. This problem was compounded by the fact that I was hunting alone.

The weather person was cooperating, providing clear skies and warm temperatures —the only thing to spoil an otherwise perfect day was a strong south wind. I felt this might make my quarry jumpy, but it would also help cover my approach, giving me some much-needed help since at this point the squirrels had all the advantage.

I had purposely gotten a late start, knowing that fox squirrels also like to sleep late in the morning. The creek bottom northwest of Seward where I was hunting was choked with weeds and brush. I was glad I had brought my 20-gauge pump instead of a .22, the standard medicine to cure a squirrel-hunting itch.

A movement off to my right startled me just as I entered the draw leading to the creek. A flash of red told me that here was my first squirrel of the day. I waited for a clear shot as it ran through the brush ahead of me, then it broke into the open and I vainly threw a load of No. 8s at it before it disappeared around a small hill. I fought my way through the underbrush to where I had last seen it, but all I could find were a few broken branches.

I knew there wasn't much chance of seeing that one again, so I continued moving. Several large oaks in a wooded area ahead looked promising, so I cautiously headed toward them. A number of leafy nests in the trees looked like home base for quite a few squirrels. My suspicions were confirmed when I found an abundance of shelled acorns under the trees. Since this appeared to be a popular local dinery, I sat down to wait for lunch time.

Through experience, I've found one of the best ways to hunt squirrels is to do nothing and let them come to you. Of course, this only works when there are plenty of them in an area and you are patient enough to play the wait ing game.

Leaning back against a large oak, I remembered with a hint of nostalgia my first hunt almost 20 years before. A wooded area like this had provided a young farm boy his first hunting experience. A collie dog named "Laddie", my almost constant companion, and a .410 shotgun had combined to bag my first game, a fox squirrel.

All my hunting memories were not so enjoyable, though, as I remembered the frustration of hunting pheasants for three years with that same .410 double-barrel and never downing one, finding out years later that it threw its pattern low and to the left. I can still recall the excitement the next year after bagging my first two ringnecks with the first two shots from a 20-gauge Ithaca double.

Many birds later, I still remember those days as though they were only yesterday. I don't have as much time to hunt now as I did years ago, and some of the fervor I once hunted with is gone. The desire is still there, but I am no longer disappointed when the bag is not full at the end of the day. Now I measure success by the per sonal satisfaction from the hunt rather than the amount of game killed.

I had almost dozed off when I was alerted by the chatter of a squirrel almost above my head. I looked up to see it watching me from its leafy perch in the oak tree. About this time it decided to head for safer parts, but a shot from my 20 gauge brought it crashing to the ground.

After retrieving it, I worked my way down to the creek bottom. Since it was warm, I decided to follow the meandering course of the creek hoping to find a thirsty squirrel. After some distance I spied one of the bushytails sitting on a log across the creek. He hadn't spotted me, so I tried to work closer for a better shot. That was a mistake. He ran across the log and disappeared into underbrush on my side.

He was headed my way when I last saw him, so I waited to see if he would show again. A rustle of leaves to my left and the flash of his red tail told me he had slipped by. The last I saw of him was when he ducked into a lofty hollow in the side of a large cottonwood.

The way he gave me the slip reminded me that fox squirrels are deserving of their name, as the little foxes are indeed crafty.

The snapping of a twig again alerted me. Looking around, I studied the area, trying to find the source of the noise. A flickering white tail was a dead giveaway as I spotted a white tail doe and a pair of nervous fawns watching me from a thicket only 20 yards ahead. Cussing myself for leaving my camera in the car, I watched them disappear from view as they slowly ran ahead of me.

Figuring the deer had probably spooked all (Continued on page 42)

Through the Ice

Here's some tips that should help even a rank amateur get warmed up to that cool sport of winter fishing

OF ALL THE things I have ever read on ice fishing, few have ever told me much. There fore, I intend to expose every thing learned during my experiences, step-by-step from making a hole to landing the fish, in hopes it will be in structive to others. This is meant to get the newcomer started in the right direction so he or she will have a chance to get some enjoyment out of this fine sport, even the first time out on the ice.

Most fishermen, when starting ice fishing, do so with whatever kind of tackle they have used in warmwater fishing, such as rods and reels for panfish. This is called jigging. The other main type of ice fishing is done with tip-ups, which you will most likely end up using; if you stick with the sport and your state allows enough tip-ups to make it worthwhile.

Whatever you use, you will first need to get a hole through the ice. If you plan to use only a couple of lines, a spud bar will do, which is a piece of pipe with a chisel-type head for chop ping through the ice. If a spud bar is used, be sure to tie a rope from it to you, so that when you finally get through the ice, the bar does not keep going and end up on the bottom of the lake. With cold hands, this happens many times each winter. If you plan to do much ice fishing, a hand auger is really worth the money. One that cuts a 6-inch hole is usually plenty. I have seen 15 to 20-pound northern pike come through a 6-inch hole. Also, a 6-inch auger bores a hole several times easier than an 8-incher. I like the Snabb auger best, a spoon type, as I can cut a+iole through 16 inches of ice in less than 30 seconds with it. The only thing better in my opinion is a power auger, and these are expensive—over $100 for most.

You will also find a strainer, used to remove slush ice from the holes that you have just bored and to help keep them open throughout the day, a mighty handy item. But, now for the fishing.

As most fishermen usually start out small, jigging for panfish, this may be your cup of tea and I advise you to have a thermos of hot tea or coffee along. Jigging can be done with any rod and reel, but the small, simple jigging rods are best. These should be rigged with 2 to 4-pound-test monofilament line and a teardrop or fish eye-type hook (a small spoon) and baited with a wax worm, mousies or some other type of grub that might be found locally. I personally like wax worms best. Use a small bobber, just barely large enough so it does not sink. I mean just big enough so some small part of the bobber stays above water. This should put you on a par with most ice fishermen trying for bluegill, perch and crappie. Small minnows will usually catch the most crappie and perch in our area, so keep this in mind. Bluegill, crappie and perch can be caught all day, but at times crappie fishing does not start to get good until just before sunset, but it continues until way after dark. The first time you go out on the ice, look for other anglers, as a bunch of fishermen usually means a hot spot. If the lake you plan to fish has no other fishermen on it, you will have to find the fish yourself. A good place to start is where you caught them in the summer, but usually in eight feet or more of water around brush, snags, weedbeds or other type of vegetation.

Panfish of all kinds, including bass, can be caught this way. At times a still bait will catch fish, but as the name implies, this type of fishing is called jigging and usually working the bait up and down (jigging it) is by far the best. Jig the bait a few times then let it come to a stop for a short time. Watch your bobber very care fully, as the slightest movement means a fish is taking the bait. In winter the bites will be very light, so watch very closely and pull at any unusual move ment of your bobber.

Jigging is also done with heavier line and a stiffer rod, minus the bobber, with a jigging lure or spoon for walleye, northern pike, bass, and in our area, catfish.

The best days to go fishing are probably those you couldn't go; but, if you keep at it, you will hit some of the good days and be an ice fisherman from then on. Personally, I like a little snow cover on the ice as it makes the footing better and much more quiet. Remember, fish feel sound, and on the ice, as on the banks or in a boat, don't make any unnecessary noises around your lines. I also like the barometer to be steady and quite high for several days, then be on the ice as it starts to fall. However, I have done quite well on all sorts of days, so be on the ice whenever you can.

Northern pike, walleye, bass and catfish are generally caught on tip ups because more lines can be set over a greater area of the lake and still be watched. A flag warns the fisherman of a bite. Whether you make your own tip-ups or buy them, it is a good practice to number them; from 1 to 15 in Nebraska. The reason for number ing them is simple: if number 7 keeps giving false flags, (a flag but no fish) you will know that one needs fixing when you get home. Also, if number 7 always seems to catch fish, you can check to see if it's not a little different from the rest of your tip-ups. Some times you will be surprised at what you find. Be sure to check all the tip ups you plan to use before you go ice fishing, as even the ones you buy have flaws which may need correcting be fore you use them. See that the reels turn freely, the flags go off as they should, and the tripping mechanism works properly. Then, after you have used them recheck them and make sure that they still work properly. Many times tip-ups with wood frames will swell and jam up. There are many types and sizes of tip-ups. Those with 8 NEBRASKAland JANUARY 1975

Tip-ups should be filled with 50 to 75 feet of 35 or 40-pound-test line. My choice is braided line as it is not as stiff and kinky in cold weather as monofilament and handles much better. A steel leader should be used for northern pike, and if the pike are large, a leader of at least 18 to 24 inches should be used as a good pike can swallow a 12-inch leader and cut the line above. I also take all snaps off the leaders and use an "O" ring for fastening the hooks to the leaders, or make my own by tying the hooks on, as snaps have a way of catching on the edge of the hole and coming undone. I use a treble hook and no weight with this setup, and fish it any where from a few feet under the ice to a foot off the bottom. Bluegill, large chubs and frozen smelt are all good baits, but the 3 to 5-inch bluegill has been the best for me. In areas where fish or parts of fish of any kind are not allowed for bait, pieces of jack rabbit, beef melt and steak are used; and, yes, northerns will hit dead baits. Generally, due to the larger live baits used for northern pike, the tip-ups must be made to trip harder than those used for walleye and bass so you won't get a lot of false flags from the bait setting off the tip-ups. For wall eye and bass, the tip-ups should work freely, as the small minnows used for 10 NEBRASKAland bait cannot trip the tip-ups as easily, and either of these fish will leave the bait if much drag is felt. For walleye and bass, use a single hook or a very small treble hook connected to a 3 to 5-foot monofilament leader of 8 to 12-pound test, and just enough weight to carry the bait to the depths.

In tip-up fishing, don't be in a hurry to set the hook. Be sure the fish has taken the bait and is making a good run with it when you set the hook. You don't need to set the hook too hard on walleye and bass, but on northerns really sock it to them to get the hooks through the larger bait and into his hard mouth.

When setting your tip-ups out, never set them so close to each other that if a fish takes all the line off one tip-up, he can tangle it up with others. I set my tip-ups (15 of them) in a staggered line about 250 to 300 yards long and I sit near the middle of them. An alternative is to set them in clusters of five or more to the left, front and right of the place I am sitting. By doing this and not scattering them out all over the ice, you can watch them better, especially if other fishermen have their rigs in the same area.

The best places that I have found to fish for northerns seem to be in 5 to 12 feet of water just off old weed beds, creek channels or dropoffs. As Spring nears, large, shallow flats are good in most lakes, especially when vegetation starts to grow on the bottom. If the water gets smokey from Spring runoff, it seems better to fish the top half of the water, say 3 to 6 feet under the ice. Bass are caught in about the same type water as northerns, and a good set is right in the weed beds if they are not too thick. Walleye will be where you find them; but, generally out in the open water and just off the bottom. Anywhere they were caught in warm weather is a good bet when ice fishing. Lots of walleye are caught after 5 p.m. and all night. In some lakes, that will be when nearly all of them are caught. They also seem to do well just before ice-out, and this is also the best time to fish catfish, and if a dead bait is used, use it right on the bottom.

When fishing where large fish are expected to hit, never go without taking along a gaff. Always carry it with you so that in the excitement of seeing a flag go up, you won't for get it. Many good fish are lost because the fisherman forgot his gaff.

Always keep your holes as open as possible by going around and chip ping out ice that has formed, and straining out the slush. As you will notice in cold weather, your holes will get smaller as ice forms on the sides. When they get to where you are in doubt of getting out one of the larger fish, get up off your knees and re bore them. Clever let your holes get where you cannot get a really good fish through them. But, if you do get a fish that won't come through the hole, gaff the fish, then take a stringer (which I keep tied to my gaff) and string the fish so you can get a spud bar and enlarge the hole to get your prize up.

When landing a fish, I always stand so I can see right down the hole, and when I can see the fish's head coming up, I put a little more pressure on him to start his head up through, and just keep him coming —flipping him out on the ice. On northerns, using a treble hook, I never use the gaff on any thing under 10 pounds if I can see that they are hooked good. On larger northerns, you can gaff them or grasp them using the thumb and middle finger in their eyes. Bass can be picked up by their mouths if there is any doubt about flipping them out of the hole safely. Walleye of good size should be either gaffed or lifted from the hole, as their tender mouths cannot stand as much as northern, bass or catfish, and the hook could tear out.

By now you should start to get the idea and start thinking of a good way of getting on and off the ice with all the gear you have. A sled is good, with a box large enough to hold all your gear, which by now might in clude such things as ice creepers, several pairs of gloves, scales, long-nose pliers, a spring device for holding a fish's mouth open while you remove the hook, sunglasses, a lantern, heater and whatever else you might think of. When making your rig, make it large enough to do the job; but, also try and make it as light as possible so you can pull the thing through snowdrifts and even mud for a considerable distance.

When going out on strange ice, watch for bubbles and cracks; this way you can see how much ice is under you and if it is safe to be on. If you cannot see cracks or bubbles, as in very clear new ice, STOP and bore a hole; check its thickness and make sure it is safe. Never take it for granted that you can go anyplace on ice just because you got where you are. The next step might be cold and wet. A good length of light rope tied to a life preserver cushion is a good combination to have with you on strange ice or on old ice in the Spring.

In ice fishing, everyone seems to be more interested in the success of others, and is more helpful than in warm-weather fishing. No matter who catches a good fish, everyone in the area wants to get in on the act. They will holler "Flag" as loud as they can, and more than likely will go along with the owner to help in any way they can. Sometimes there is too much help and the fisherman has a problem with everyone crowded around the hole looking. It is fine to be helpful, but give the owner a chance to move around and get the fish in position to come up through the hole. Once the fish is lying on the ice, so is his line. A good way not to make friends is to walk through his line and tangle it all up or step on it with your ice creepers and damage it so that the next time he gets a fish, it can break his line. So use your head, be helpful, but also give the fellow a chance to do his thing —however he does it —and you will be a welcome addition to this fine gathering of hardy sportsmen.

When you are not familiar with an area, look the road over as you drive down to the lake. Remember that most likely in the morning the road will be frozen and passable, but as the day warms and you get interested in fishing out on the lake, it has been thawing and getting sticky. One of the worst things after a good day's fishing is getting stuck —unable to get home to the little wife who in most cases cannot understand what you are doing out there in the first place, and why you never want to stay home with her and the children or go to her mother's.

Well, that is the way it is —catch as catch can, cold, sometimes wet and a lot of hard work. Anyone going out in these elements has to be a little strange. But, if there are fish to be caught, you will have plenty of company on almost any day you choose to start this fine sport.

Winter Survival

Nebraska offers recreational fun for the knowing, prepared cold-weather camper

SOMEWHERE AT THE ends of my hands and feet were toes and fingers; at least I thought they were | still there. It had been hours since I lost the feeling in my extremeties, and my hands and feet numbed to icy lumps. The wind howled outside, and my hourly chore of pounding on the tent to dislodge the drifting snow was getting to the point of futility. I realized that I must do something soon. After some delirious and unorganized thinking, I opened the tent flap to confront a solid wall of white. I clumsily dug through with chilled hands. Breaking into the open air, a 60-mile-per-hour gust nearly knocked me down. Everything was white around me. The only evidence of the tent was six inches of poles sticking out from a huge snow drift. It dawned on me then that lack of air was the cause of my headaches and muscle cramps, and it had been a close call with death from suffocation. A two-day ordeal of blizzard, cold and exhaustion followed, as I tried to escape Mother Nature's show of icy fury.

That was my first go at winter camping in Nebraska. And, as it so often does in January, Nebraska's weather decided to have a full-blow blizzard for my "maiden flight." Escaping only with the help of a hospitable small-town innkeeper who graciously put me up, I vowed then and there never again to invade the wintry domain. I knew then that winter camping was a recreaction reserved for masochists, ascetics, and an assort ment of generally insane individuals. To tell me at that point that I would one day be an avid member of the winter camping crazies would have been absurd.

That was several years ago. Now I reserve winters as my prime camping time. I like to backpack with light weight equipment and meet the natural world on its own terms. Several considerations for this type of winter recreation were "left out" of my novice preparations. Involved were equipment, physiology, and general cold-weather living that enable one to survive comfortably even under the most severe winter conditions. No matter the type of winter sport, be it cross-country skiing, hunting or ice-fishing, there are some potentially life-saving informational tidbits to be learned.

There are many degrees of winter weather hazards or hardships that people tend to ignore. However, one must realize that all stages, no matter the severity, will eventually culminate in two major cold-weather sicknesses, both of which are serious and can result in death. The most common malady is frostbite. One often associates frostbite only with mountaineers, but it is a problem to be dealt with by all winter sport enthusiasts, and even outdoor workers.

The body regulates and maintains its temperature by circulating warm blood to all points. There are priorities for this heating system, and if a shortage of heat occurs the body will concentrate blood around the body core where many of the important organs are, and where major body functions take place. This internal survival procedure maintains vital functions and keeps the proper operating temperature for the body organs and the head, but it leaves the extremities wanting for heat. When met with this situation, the body actually constricts or closes blood vessels to the hands, feet and skin surfaces. The absence of warm, circulating blood to the fingers and toes simply means they begin to freeze like sausages in an icebox. With the absence of life-giving blood, nervous systems to the fingers and toes also shut down, causing a cold numbness that grows into a complete lack of feeling.

There are stages of frostbite. The least severe, often called "nip", is usually due (Continued on page 45)

Photographs by Jeff Kincaid

All Things that Love the Sun

MAN'S PERSPECTIVE is always changing, as situations arise to spark his curiosity, his inventive capabilities or his anger. Competition from many sources may mean a race to develop a faster vehicle or a bigger something, yet man is still a simple being, easily confused or angered by trivial matters that are totally unimportant. And, he is also pleased by simple things, such as a sunset, though he has seen thousands before; or a drop let of water poised on an autumn leaf as it prepares to fall somewhere on the vast expanse of earth, unheard and alone, yet one of billions which fell before. It is perhaps man's ability to see and appreciate these simple factors that keep him from destroying all around him. Mankind must always be aware that just as the plants need sun and rain, humanity needs the plants. The proper perspective will also point up that no amount of technology can substitute for what nature has wrought, for the beauty and functional design of a leaf and a plant cannot be replaced by plastic. To pump moisture from the ground to a height of over one hundred feet, and convert man's pollution back into healthful oxygen, are tasks too difficult for man's engines and adding machines to tackle. It is the basics of life —the air, water and sunlight —that are important and which man must make every effort to understand and preserve. The frills of modern society are only to dazzle those less fortunate, yet without the proper perspective, they can become necessities if people become too dependent on them. Here, then, are some examples of what is available to be relished by those with the perspective, or the desire to learn, to appreciate the simple beauties.

Photos courtesy Wapiti Wilderness Project Photograph by Peter Amburg 14 NEBRASKAland JANUARY 1975 15 Photographs by Vincent Kershaw

JANUARY 1975

17

Photographs by Vincent Kershaw

JANUARY 1975

17

Photographs by Vincent Kershaw

18

NEBRASKAland

JANUARY 1975

19

Photographs by Vincent Kershaw

18

NEBRASKAland

JANUARY 1975

19

Tough Times for Pheasants

WHEN IT'S 13 below zero and that's as warm as it's likely to get all day, chances are that hikers won't walk, pilots won't fly, ice fishermen will find an excuse to stay home, and skiers will head for the fireplace and a cup of hot chocolate.

And, when you add even a small breeze to the sub-zero reading, most pheasant hunters hang up their scatterguns for a while. But not Nick Lyman of North Platte, a Game and Parks Commission wildlife technician whose work takes him out doors the year-round.

January, for example, usually finds Lyman somewhere around concentrations of wintering ducks, trapping and banding birds to gather manage ment data. It's not a warm job, by any means, and it usually demands seven days-per-week attention many miles from home. But there's sometimes an hour or two at mid-day when there's nothing that can be done at the traps. So, put yourself in Lyman's shoes. Those few hours are likely to be the only time off you're going to get for a while, you're in the middle of some good country, you're already bundled up against the cold and numbed to the sting of the breeze. And besides, your fine draathaar pup, Fritz, is whining and begging for a workout. There's little else to do but go pheasant hunting.

During the drive to the chosen hunt ing spot, talk comes easy for Lyman. "I've worked with wildlife for 14 years now, and I've been up to my elbows in stocking, trapping, banding and all the other game management activities the Commission is involved in. I learned a lot about wildlife in that time, but the thing that sticks with me the strongest is something I knew before I took the job. I learned young that wild things have to live out there all year round, and they've got to have the things they need for survival 12 months a year.

"Being out here in this kind of weather makes you realize what wild life goes through in the winter. It's tough on me and Fritz, and we can get warm in the pickup in an hour or two. The next chance a pheasant has to get warm might be two or three months away. A fair-weather, open ing-day hunter should be out with us today. He would see that stocking game-farm birds out here is not the way to boost pheasant numbers.

"And neither is cutting off hunting. If the self-proclaimed naturalists would poke their noses out of their offices on days like today, they would understand why we say that winter cover, not the hunter, determines just how many birds and animals survive to reproduce next spring. Just look out there. If you were a pheasant, where would you go?"

Lyman gestured toward a bleak landscape that appeared as if it couldn't harbor a single living thing. Entire fields had been turned to absolutely featureless deserts of snow, reflecting the stabbing rays of the sun. The only movement was provided by the breeze, as it skated a broken tuft of weed across the frozen surface or rearranged drifts around fenceposts.

The conversation ended abruptly as Lyman and Fritz stepped from the pickup. It was too cold to talk. The frigid air burned throat and lungs, and the sting of a gentle breeze made eyes fill with tears. Lyman was joined by Don Studnicka, a wildlife technician at the Sacramento Game Management Area. Studnicka had been helping Lyman work his duck traps the past few days, and decided to come along on the pheasant hunt.

Lyman slipped a pair of high-brass 12-gauge No. 4's into a side-by-side double that gracefully bore the scars of many similar campaigns, while Studnicka did the same to a shiny over-and-under.

Fritz frolicked to the edge of the field, a quarter-section of CAP land, even before the hunters were ready. He waited impatiently until Lyman and Studnicka waded through the snow-filled ditch to join him. Even though the breeze was only a few miles per hour, the hunters avoided it whenever possible. The plan was to work the west boundary of the field with backs to the wind, then turn east along a canal where a small berm offered a bit of protection. That wind break also held promise of some birds.

Most of the half-mile walk to the corner of the field was just plain work. The snow was a good 18 inches deep, and kicking through it made the lungs smart from pumping in the frigid air. Most of the way, there wasn't even a sign of pheasants —nothing but the tops of grass stalks surrounded by snow.

Then, in an area of a bit heavier cover, some hemp stalks blown full of fireweed, Lyman announced that Fritz was acting "birdy". The yearling German wire-hair methodically worked down a narrow finger of heavier weeds with Lyman and Studnicka in tow. Suddenly, the little pointer slammed on the brakes and froze on point, staring at a clump of grass just to his left.

Lyman and Studnicka were approaching the rigid pointer when four or five birds boiled out of the snow. The farthest one was a cock, and he immediately drew all the hunters' at tention. Studnicka's shot didn't touch a feather, but Lyman dumped him neatly.

Both hunters relaxed a bit as Fritz romped through the snow to retrieve the downed bird. Studnicka opened his gun to replace the spent shell, while Lyman watched his young dog work. Then, (Continued on page 44)

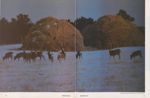

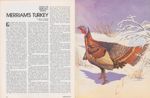

Rim of the World

Nebraska's northwest corner is a colorful wilderness. Absent are the sounds of traffic, of radios shouting. Nature's noises echo across the grasslands and pine

Photographs by Bob Grier 22 NEBRASKAland JANUARY 1975 23

FINGERS OF MIST caress the canyon floors and touch the buttes like a loving, velvet-gloved hand.

A pastorale of tree frogs awakens a reluctant sun as the first lustrous hint of light softly gilds the fog. Then, frogs yield to the lighter melody of bluebirds and tohees.

A camper, his tent facing east to capture the first warming rays of the sun, looks out from his canyon-rim lodging to the fog-silvered canyon floor and the mist-shrouded valley beyond. It seems that he stands on the rim of the world.

Deer and turkey are moving now; bobcats prepare to den up for the day.

A light morning breeze whispers through acres and acres of ponderosa pine, yet the sound accentuates the silence — the absence of man noises. There are no machines, no buzzes and roars and beeps; only stirring pine needles and frogs, beginning again as warmth silences the birds.

But the ridge is not always silent, and the velvet glove of mist sometimes

A rain-smell builds with the clouds, and the Ridge seems to hold its breath. Birds are silent, awaiting the shattering crash of thunder. Rain spatters on dusty roads in huge, cold, springtime drops, pounding on the tender yellow petals of lupine.

As spring turns to summer, the rain diminishes; the Ridge dries; sun bakes the towering buttes. But along the creek bottoms, cold spring water refrigerates watercress and cools shimmering trout. Cottonwoods and ash steep their roots in the streamside dampness of dark earth. The pines endure.

Hillsides of scattered wildflowers change their colors as the tiny plants take turns blooming in orderly succession. First the clumps of white mountain phlox, and the pasque flowers, then milk vetch and sego lily, then yucca.

Fall brings haze and mist to the Ridge and golden strips of Cottonwood and ash trees along the bottoms of pine-timbered canyons. Deer begin antler polishing on the shrubs and brush that line clearings.

Creek bottoms become strips of yellow and gold, touched with flames of sumac and Virginia creeper. A hunter glasses the canyons, then stalks deeper into the Ridge, rifle slung on his back. A clear shot at sundown will mean carrying his deer out after dark, yet the sights and sounds of approaching evening draw him on.

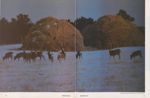

Time brings snow. Three deer pick their way across a silent, frozen hill side, pawing up last night's snow to graze. Ice is a crystal in blue-white shadows and on smooth, sunlit hillsides. Sharp clumps of green yucca leaves pierce the snow, disdaining its protection from the wind and ice.

Snow weighs heavy on ponderosa pine, bending boughs to the earth. Creeks trickle between icy banks and frozen meadows. Summertime silence is accentuated with a bleak afternoon sun teasing with the warmth it's sup posed to provide.

Silence. Only wind in the pines. The sharp crack of a deer's hoof on rock.

Over History's Hill

A possibly unique and highly valuable "buffalo jump" of plains Indians, unearthed at Crawford, is now being researched by Dr. Larry Agenbroad

Photographs by Bob GrierTHE YOUNG Indian boywatched quietly from tall grass on the side of the hill, ready to learn the hunting techniques of his civilization. A seemingly solid herd of black, shaggy buffalo grazed in the shallow valley between low hills. He watched as older boys jumped out of hiding, shouting and waving robes at the stragglers. The startled cows dashed into the rear of the main herd, which began to lope down the valley. More men appeared on the hillsides, frightening the herd into a stampede.

The lead bull did not see the drop-off into the ravine and plunged to his death. Half the herd filled the ravine before the last animals escaped over a bridge of broken bodies. The Indians moved in from the hills to begin the butchering. They young boy helped drag the carcasses to a flat, grassy place near the stream, a few feet from the ravine. The Indians skinned the animals, butchered and stripped the meat, and dried it for pemmican or jerky. Some of the meat they stored. It would soon be winter, and they easily had enough meat to last over the cold plains winter. The buffalo fur and hides would make robes and shelter. The buffalo hunt provided all they needed.

Thirty-five years ago, rancher Albert Meng was inspecting his grazing land northwest of Crawford, Nebraska, on the edge of the Nebraska Badlands. Meng discovered some bones in the ground that he knew were too large for cattle. He and a friend, the late Bill Hudson (former mayor of Crawford and avid amateur archeologist), determined that Meng had found a bed of bison bones. During the next 30 years, the two men asked seven university and museum institutions across the country to look at the site.

Finally, in the spring of 1968, Meng contacted Dr. Larry Agenbroad of the Earth Science department at Chadron State College (CSC). A permit in hand from the U.S. Forest Service, Dr. Agenbroad began test digs. The site is 23 miles northwest of Crawford, on Forest Service land in the Oglala National Grassland. After prospecting the site each fall for three years, Agenbroad and several of his Chadron College archeology students discovered a spear point. The evidence linked the bison bone bed with man, and strong ly suggested a major kill site.

"What kept spurring us on was the fact that we could find no hooves or skulls among the bones," Agenbroad said. It suggested that man was in volved in the kill; that it was not a natural occurrence. "Once we found the spear point, we knew we had a big deal."

In the summer of 1972, the Chadron State College Research Institute gave Agenbroad $1,900 for a 5-week excavation. The archeology teacher and a crew of 16 students uncovered 119 square meters of the bone bed. At the end of the summer, the crew had unearthed the bones of 118 complete bison, and 14 human artifacts, including spear points, knife blades and hide scrapers.

"It appears that we've got a transition not only in point styles (of spears),

but also in the animals," Agenbroad

said. From the size of the bones it appears the bison were in an intermediate stage of development between

33

modern bison (Bison bison) and an

cient, extinct bison (Bison antiguis).

modern bison (Bison bison) and an

cient, extinct bison (Bison antiguis).

Carbon-14 analysis and metric measurements will tell if the bones are indeed an intermediate stage, or if they are one of the known species. Agenbroad feels "either case would be equally exciting." He said all preliminary data confirms that the bones are 9,000 years old.

The spear points are more closely related to the Alberta point found in Canada, both in style and the way they are made, than to the more modern Cody complex, found in the Scottsbluff area. Carbon-14 tests will help the experts decide if the points are a transition from the Alberta to the Cody style.

"This appears to be a missing link," Agenbroad said, "at least in the tech nology of the Paleo-lndians." He dates the points chronologically in the Piano period, about 9,000 years ago.

An analysis of the stone used to make the weapons and tools shows that there are two distinct kinds: one from the Canadian border along the Knife River, and the other from near Flint Hill, S.D.

"If these findings are in fact transitional," Agenbroad said, "then it's the only site of its type...to be discovered."

Until the summer of 1972, the mystery of the kill was the absence of skulls and hooves. In 1973, however, the crew uncovered 46 skull portions.

"The skulls are desirable for us to find since that is where most of the diagnostic data has been worked up," Agenbroad said, adding that in order to identify the exact species, the archeologist needs skulls with horns. To date, only one horn core has been found.

"One reason this site is so important is because we really don't know anything about these people. It would be great to find a campsite." A camp would yield tools other than those used for butchering the bison.

"From all we know, they were migratory big game hunters," Agenbroad said. Indians had hunted the mammoth elephants until they died out, then they turned to the bison and smaller game. The Hudson-Meng site tells much about the Indian hunting and butchering techniques.

"I think they worked this thing very efficiently, and butchered very expert ly," Agenbroad said. The Indians lived in the pre-arrow and pre-horse age. Using only spears for weapons, driving the bison over a cliff or into a ravine was the fastest and most effective way to kill a large number of animals.

"Every indication says the site was used once and that's it. The spring and stream bed up here is the key to why they (both man and animal) were here at the same time, and the Indians made it work for them."

The kill took mostly cows, although several calf skeletons were found one summer. Agenbroad said the bison teeth show the kill occurred in late October or early November. The animals ranged in age from 6 months to 10 1/2 years old. Agenbroad estimates that 68 per cent of the animals were about 4 1/2 years old.

Less than half the site has been excavated, but about 200 complete animals have been sent to the lab. Agenbroad estimates that fewer than 75 people butchered about 400 animals at the site. If the average cow yielded 100 pounds of meat, the Indians would have at least 15 tons of jerky, most of which they probably cached nearby for later use. There would be no way for them to transport such a quantity of meat.

The full size of the Hudson-Meng Bison Kill Site, named in honor of the men who first discovered it, is not yet known. The west and south bound aries have not been located. The actual kill site has not been found either; where there should be skulls with horns, possibly capable of pro viding much information. About a third of the site was destroyed 13 years ago when a dam was built on the small, meandering stream. So far, the only real boundary is on the east.

Excavation began in 1972 on June 20. The National Science Foundation granted the archeology teacher $8,600. He then recruited students from Chadron State College and universities in South Dakota, Wyoming, Arizona, Minnesota, Oregon, Utah and California. The crew averaged 20 persons for the 7 weeks the site was open.

The volunteers paid a course fee to cover food expenses, and received one college credit for field work on the site for two-, five-, and seven week periods.

The work in the summer of 1973 netted an additional 6 spear points, 2 stone butchering tools, 1 bone butch ering tool, and more than 350 stone flakes. Agenbroad said some hooves and skull portions were found at a rough butcher area to the west of the main site, and he hopes to find the kill site next summer, to search for skulls with horns.

"One of the reasons I came into this country (Nebraska) was because nobody has really done any work in the eastern high plains," Agenbroad said, although he had predicted the geographic area would be rich in artifacts since it is in the logical area for big game hunting and Indian migration from Canada.

His theory is that the Pleistocene Indian came across the Bering Strait through the Yukon to central Canada, and then into Montana and North Dakota, before coming south to the high plains.

One intriguing discovery at the site was evidence that one man sat in the middle of the butchering area making weapons and tools. About 1,750 flakes of stone used to make the tools, have been uncovered. Conclusive proof that the tools were made on the spot: Two flakes fit exactly into one of the spear points. That point was found within three feet of the cleared spot where the tool-maker sat.

"I think that's pretty exciting from the standpoint of visualizing what was going on," Agenbroad said. "I think it's the discovery that keeps the students going," meaning the tedious work of digging, scraping and sifting the many tons of dirt. Each member of the crew is assigned a square meter (39 inches) in which to dig, Agenbroad explained, and "he is the person who is opening it up for the first time in 9,000 years."

"It shows we're doing some competent research up here," Agenbroad said, adding that competency in field research was hardly the image that state colleges have had, "up 'til now."

Students from many states are helping with excavation. They pay tuition and get credit hours for field work. Over 200 animals have been uncovered, but only one horn core, needed to identify bison

Prairie Life/ Energy Flow

Photographs by Jon FarrarAN OLD BIOLOGY text of mine introduced a chapter on animal interactions with a quote by a contemporary of Charles Darwin suggesting that the glory of England was due to its old maids. The argument went like this: "The sturdy Britons were nourished by roast beef from cows, which ate clover, which was pollinated by bumblebees, which were attacked in their nests by mice, which were kept under control by cats, which were raised by old maids/' The argument, presented tongue in cheek, illustrates several relationships found in all natural com munities. Britons eating cows and cows eating grass is an example of a food chain, whereby energy is transferred within a natural community. Mice eating bees and cats eating mice is another food chain; one illustrating increasing levels of predation. And, the relationship between the old maids and the cats was sighted as an example of symbiosis, an arrangement between two species of animals in which both benefit. These same relationships are found in natural ecosystems, but in infinitely more complex forms. The meshing of a number of food chains into an elaborate system of interrelationships is called a food web.

Initially, all energy comes from the sun. Were it not for a thermo-nuclear reaction occurring some 93 million miles away, life on earth would not exist. By it, solar helium is transformed into sunlight. Green plants, and only green plants, convert this solar energy into a form available to other life by the process of photosynthesis. Directly or indirectly, all life depends on the carbohydrates, fats and proteins produced by plants. At the bottom of every food chain is a plant. Fortunately, for us and other animal life, plants carry on far more photosynthesis than is necessary to sustain their, life. These surpluses of energy fuel the fires of all life on this planet.

To an ecologist, plants are the "producers" of natural systems. Animals that derive their sustenance from plant products are either first-order consumers, the herbivores; second-order

Plants are the only organisms adapted to convert sunlight into a solid form of energy, and herbivores are the only animals that can live on a diet high in cellulose. Just as herbivores are dependent on plants to convert solar energy into a form available to them, carnivores depend on the herbivores to transform cellulose into a substance suited to their digestive systems. Some carnivores, of course, feed on plant materials, especially fruits, but this is always secondary to their meat diet.

The chief herbivores on land are the insects, rodents and hoofed animals. Animals of these groups are by far the most abundant and diverse on earth. Hoofed animals are so well suited to a diet of cellulose that they are the dominant large animals of grasslands around the world, be they bison and pronghorn on the North American prairie or the guanacos and pampas

Predators and prey live an uneasy balance in any natural community. Some predators are so specialized that they feed primarily on one particular prey species. If their prey de clines in numbers, the predator must either switch to an alternate food, move to another area or ultimately decline in numbers themselves. Through millions of years of evolution, certain natural controls have emerged to minimize drastic fluctuations. One of the most effective of these controls is territoriality. Most predators maintain as large a hunting ground as they can defend from intruders. It is no coincidence that territory size nearly always matches the amount of area needed to raise the number of prey that meets the predators' food requirements. More simply stated, the predator defends the amount of food it needs to survive.

Occasionally there are carnivores that feed on other carnivores, but in

36 NEBRASKAland JANUARY 1975 37

most natural communities this is a luxury that the system cannot afford. The number of carnivores in any ecosystem are so few, and they are such formidable adversaries, that more energy is lost in finding and killing them than is gained in eating them. Secondary carnivores do exist but they are generally opportunists, not specialists. If they happen on another carnivore that they are capable of killing, they may do so. A golden eagle may take a young coyote or a coyote may kill a long-tailed weasel, but generally it is more economical for both to hunt rabbits.

In the few cases where one carnivore regularly feeds on another carnivore there is generally a substantial difference in their size. Large carnivores seldom attempt to take other large carnivores, but under certain conditions and with particular species, large carnivores may feed heavily on small carnivores. The great horned owl probably makes no distinction between a vegetarian meadow mouse and an insectivorous shrew. Carnivorous dragonflies or robberflies that capture and feed on smaller insects, are common fare for insectivorous birds. Toads, frogs and lizards that feed on insects are regulars in the diet of other animals, especially snakes, which in turn are taken by birds and mammals. In many cases of carnivore eating carnivore, the victim is an in sect eater.

Many consumers do not confine their feeding activities to either plants or animals, and consequently do not fall neatly into one category or another. In one night a red fox may dine on deer mice, wild grapes and a road killed opossum. Thus, it is at one time a carnivore, herbivore and scavenger.

Scavengers are specialized carnivores that have the unique distinction 38 NEBRASKAland of not affecting the dynamics of their prey. Turkey vultures that soar the Missouri River throughout the summer, feeding on the remains of deer, rabbits and domestic livestock, in no way influence the population trends of their prey. Most parasites occupy a similar position. Though they live at the expense of another animal, their affect is minimal. Indeed, the most efficient parasites are the ones that draw nourishment from a host without causing its demise.

The final order of consumers are the decomposers. Decomposers are primarily micro-organisms such as bacteria, yeast and fungi that break down the bodies and wastes of other animals. They are the final arc in a natural community's cycle of energy; coverting organic materials into in organic compounds that can be used by photosynthetic plants.

To graphically illustrate the relationship of these orders to each other, biologists have introduced a concept called the pyramid of numbers. It is a visual way of representing the declining number of individuals at each higher level of a food chain. The or ganisms at the bottom of the food chain, the plants, are the most numerous and the carnivores at the top are the least abundant. This seems necessarily so when we consider that, for example, one prairie dog requires a large number of plants to sustain its life and one coyote requires many prairie dogs to sustain its life. If we were building a pyramid of numbers from this food chain and each individual organism was represented by one building block, the grass blocks would form a large tier at the base, the prairie dog blocks a much smaller tier and the coyote blocks a relatively tiny tier on the top. This same relationship of numbers is true of all food chains regardless of their complexity.

When a prairie grouse feeds on the fruit of the wild rose, or a Cooper's hawk successfully downs a grouse, a transfer of energy is being made from one level of the pyramid to another. In accord with the second law of thermodynamics, this transfer of energy is never 100 percent efficient. Some of the energy is lost. One pound of rose hips does not convert into one pound of grouse flesh, and one pound of grouse flesh does not make one pound of flesh on the Cooper's hawk. It is because of this loss of energy during transfer that pyramids are always sloping. It takes many pounds of rose hips to raise one grouse and many pounds of grouse to support one Cooper's hawk.

A biologist studying the ecology of an abandoned farm meadow was able to put some quantitative values on energy transfer along a food chain. The chain he studied was a relatively simple one: vegetation meadow mouse weasel. The mice ate primarily vegetation and the weasels fed almost exclusively on meadow mice. The study showed that the vegetation converted only about one percent of the available solar energy into plant tissue. The mice consumed about 2 percent of the vegetation and the weasel about 31 percent of the mice. Plants used about 15 percent of their energy in respiration, the mice about 68 percent and the weasel about 93 percent. Nearly all of the flesh consumed by the weasel was burned to capture its next meal. It is obvious that a carnivore that preyed only on weasels could not survive. More energy would be used in locating and killing a weasel than would be gained consuming it.

The inefficiency of herbivores in converting plant tissue to flesh is understandable. Plants, to a large part, are made up of indigestible cellulose or silicious matter. Various trace elements required by herbivores are scanty in plants and may occur in some species and not in others. Consequently, herbivores must consume large quantities of vegetation to meet all of their nutritional requirements. They must consume more vegetation than would be required to simply fuel their bodies.

Carnivores encounter far fewer difficulties in converting their fleshy food into usable energy. But, they must expend a far greater amount of energy to locate and capture their food than does a herbivore. The weasel gained only seven percent of its prey's energy, scarcely enough to perpetuate its kind. Far more energy is available at the lower end of any food chain. Dining on another's flesh, in many cases, is a distinct luxury. The implications of this axiom to man and his burgeoning societies are only too obvious.

In a natural community, such as the prairie, relationships are seldom as simple as mice eating grass and weasels eating mice. The transfer of energy in a natucal system is rarely an uncomplicated food chain. Every chain is interwoven with other chains, and changes in one link may have far-reaching, seemingly unrelated repercussions. Meadow mice not only eat vegetation but bird eggs, insects and young of its own kind, as well. It is fed on by uncounted prey animals in addition to the weasel. Its carcass is attacked by parasites, scavengers and decomposers.

Only in recent years, with the aid of sophisticated computers, has man scratched the surface of the natural world's complexity. Before that, our volumes on natural historv were largely descriptive. Today, but still in the most primitive way, it is possible to feed raw data into a computer and construct a model of a natural system. For the first time we can see the effects of changing part of our world. What will be the effect of pesticide accumulation? How does changing the plant composition of a community such as the prairie, alter the animal life? What organisms are affected by removing one food chain segment?

Only now are we beginning to realize how fragile this web of life is. In the last 100 years we have tampered with our natural environment more than in all preceding history. We have bent, destroyed, altered and rebuilt entire ecosystems. The effects have been far-reaching, touching on life far removed from the point of change. The fear of many is that we will eventually change the conditions on this planet so radically that it will no longer operate in all its intricacy; that we will make it unfit for man and his plant and animal companions to survive. Hopefully, man will learn that he is only one small part of the natural world, no more than the prairie falcon or pasque flower.

THE HUNTING EXPERIMENT

After seven years' trial, state field laboratory personnel feel that bird hunting has worked well and will be continued

IN 1967, the administrators of the University of Nebraska Agricultural Field Laboratory, with some trepidation, opened approximately one-half of the 9,500-acre Field Laboratory near Mead to public hunting. This public-relations-oriented activity was undertaken on a trial basis. After completing seven hunting seasons, we believe the undertaking is very successful despite some problems.

The Agricultural Field Laboratory is essentially the south half of the former Nebraska Ordnance Plant, Wahoo, Nebraska. The Field Laboratory is in the Todd Val ley, a former course of the Platte River. These are water deposited soils with many basin areas which collect water during wet seasons. The cropping pattern has been a mosaic of alfalfa, warm and cool-season grasses, some corn and milo, with a small percentage of winter wheat and spring cereal crops. Much waste area is undisturbed due to abandoned railroad tracks, former farm site shelterbelts and windbreaks, and superimposed surface drains. This tract of land became available to the University via a 20-year, public-use permit from the Department of Health, Education and Welfare. Agricultural research, because of increasing demand, has first priority on the use of the land with cooperative extension activities and demonstrations being secondary.

Public benefits, in addition to the above, are in creased due to the recreational aspects of the hunting activity. In 1971 the Nebraska Army National Guard was convinced to allow small-game hunting on an additional adjacent 1,200 acres. This area, left in bromegrass and alfalfa, is virtually undisturbed year round except for weekend maneuvers and training sessions by military personnel. What are the results of this activity? First, we find that we are involved with the management of people along with an indirect type of management for the game.

Use of the land for research projects is of prime importance, but our project leaders have been cooperative and tolerant of the hunting activity.

There are no restrictions on the number of hunters and there is no fee for hunting. Hunting pressure is in tense the first few weekends; as many as 30 hunters persection of land per day. In time, however, hunters vol untarily regulate their numbers in a given area at a given time.

Hunters sign in and out at the Field Laboratory headquarters. They are asked to indicate where they live and the game they have harvested. They are also given a map of the area which denotes six sections of land which are off limits to hunters due to concentrations of research animals during the winter months. Also, some areas are closed because of the number of buildings and research equipment. One University employee patrols the area each day.

40 NEBRASKAlandRoving daytime guards are firm and diplomatic but thorough —in acquainting those hunters who intentionally or unintentionally are hunting in a "no hunting" area. Recurrent offenders, through their hunting or auto licenses, are notified by mail that we do not welcome them back. More frequent visits to the area by Game and Parks Commission conservation officers will greatly help in dealing with this type of offender.

We find that many hunters link beer and liquor consumption with hunting activities —an unwise mixture. Drinking alcoholic beverages is not permitted on state property, and in the future this aspect will be emphasized on the hunting brochure, by signs at the check-in station and by signs throughout the area.

Another problem is that we allow hunting solely with a shotgun, but occasionally hunters bring rifles, concealed or not, into the area in their vehicles. The restriction rifles will also be emphasized.

Is too much game harvested? Inspection of data surprisingly indicates that the game count is gradually increasing each year. This past season Nebraska hunters inferred that eastern Nebraska had fewer pheasants to harvest, but at the Field Laboratory the pheasant bag was up'l 4% over the 1972-1973 season.

Indirect management for the benefit of the pheasants is carried out whenever possible. Roadsides are good nesting areas, so roadsides at the Field Laboratory have not been mowed the last few years until the first of July, a date which least disturbs the nests and broods. The late mowing is also a means of conserving energy, and is due in part to a shortage of personnel during the May planting and cultivation of the row crops during June.

The abundance of pheasants can also be attributed to the numerous miles of abandoned railroad right-of way in the area. These tracts are practically inaccessible and thus are not mowed or sprayed for weeds.

Shelter from winter storms is provided by numerous tree plantings; some six miles of newly planted trees for windbreak research, and older plantings that are remnants of the many farms which once occupied the area.

Large acreages of warm and cool-season grasses, most of which are harvested after grazing, provide a beneficial habitat for pheasants.

Overall, the hunting program represents commendable cooperation toward a common goal by three state agencies —the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, the Nebraska Army National Guard, and the Game and Parks Commission.

Rural development for the public's benefit has received publicity recently in national program planning. Hunting at the Field Laboratory is an example of how this objective can be carried out with a minimum of funding.

SOLO FOR SQUIRRELS

(Continued from page 7)the squirrels in the area ahead, I decided to try a new tack. There was a cornfield on the far side of the stream, so I went to where there was a fallen log over the creek and shakily crossed to the other side.

Working along the edge of the corn, I was still looking for squirrel number two when a covey of quail exploded at my feet. Tracking one of the birds with my shotgun, I mentally pulled the trigger and then swung to another as the first fell. I felt a surge of satisfaction knowing that both birds would have been bagged had I really shot at them, but since the quail opener was still several weeks away, they escaped the shot and the pot.

Marking the covey's location in my mind, I promised myself I would return to the spot later in the season. Just a few steps later, a distance ahead, I spotted a bushytail dashing out of the cornfield. Another of my quick shots only scattered leaves and twigs, somewhat noisily, and Mr. Squirrel scampered through a plum thicket. I had been "foxed" again.

The score had now climbed to three to one in favor of the squirrels. It was getting toward midday, siesta time for the bushy tails, and I didn't see any more of them for several hours. Spotting an abandoned farmhouse about a quarter-mile away, I decided to check it out. A lot of farm houses in the area have walnut trees grow ing around them, so it seemed a natural haven for the little tree-climbing nut lovers.

Close scrutiny of the area revealed only one small walnut tree in the farmyard. The broken remains of walnut hulls attested to the onetime presence of a squirrel, but he was certainly nowhere to be seen now.

I couldn't help noticing a few seedling walnut trees growing in the area around the large one. The squirrel's penchant for storing winter food was inadvertently providing for future trees and bushytails. His habit of burying nuts beneath the leaf mold had given a few forgotten, sprouting seeds a firm foothold on which to grow.

I knew it would be years before these seedlings produced a nut crop, if they survived that long. The young trees would have a hard fight to grow to maturity, but nature takes care of its own. Barring man's influence, I knew some of these saplings had a good chance of one day producing a nut crop.

The late afternoon sun was at my back as I turned and headed toward the car. After crossing the creek, I planned silently, I would work the other side back. A cut milo field paralleled the stream at this point, so I didn't expect much action. Farther ahead, though, fingers of timber land extended into the field where ravines had been cut by erosion years ago.

Remembering how the evils of soil erosion had been drilled into my head since childhood, I smiled when I saw how habitat for animals had been created un intentionally when the cropland washed out. Since the gullies could not be farmed, they were left to their own devices and reverted to a natural state. It's a sad fact that habitat is rapidly decreasing across the state and the only cover left in many places is land that cannot be farmed. And much of that is cleared or mowed or burned.

By now I was getting close to the car and the sun was getting low. Since I only had one squirrel, I dropped back into the gully and began to search the treetops again. The limit was seven, but I was will

ing to settle for a pair of the tasty rascals.

I was close to the place where I had shot my single bushytail when a rustle of leaves and the scratching of something told me that I had a chance to improve my score.

I couldn't see him, but I would have bet that he was watching me. I waited a few minutes and carefully scanned high and low. But, he was playing hard to get. Using an old squirrel hunter's trick, I tossed a stick to the other side of the suspect tree. That did it! He gave his position away as he circled around to my side. Realizing his mistake at the last instant, he shifted into high climbing gear. My shot connected and sent him plummeting to the ground, and my self-imposed limit of two was filled.

Tired yet refreshed, I headed back to the car as the sun crept nearer to the horizon. The cackling of a flushing rooster pheasant in the milo field ahead was a perfect end ing to an equally perfect day and reminded me that I had a date with him and a covey of quail in a few weeks.

TOUGH TIMES FOR PHEASANTS

(Continued from page 20)another cock, sitting tight through all this, thrashed out of the weeds and struggled for altitude to Studnicka's right.

He slammed the gun shut, swung on the bird, and clicked his firing pin on an empty chamber. The gun had automatically switched back to its No. 1 bar rel when opened, but there hadn't been a chance to reload it. The shell in the other barrel went unused.

Lyman had used his "long" barrel on the first bird, and by the time the second ringneck had crossed into his field of fire, it was out of range of the remaining "short" barrel. The rooster had made good his escape without losing a feather.

Little remained now but to head for the road, and the only logical route was along the canal. It offered the only other cover within sight.

"You know, I heard some guys say this CAP field looked like real good cover this fall," puffed Studnicka, "but they should see it now. The whole works is blown full of snow. The only cover that's lasted is this strip along the canal and that little patch of hemp and fireweed. Out of the 160 acres, maybe 10 acres are still any good to the birds. There's not a nickel's worth of cover left on the other 150."

Back at the pickup, Lyman elaborated on Studnicka's observation along the canal. "It's only luck that there was any winter cover in there at all. If that fire weed hadn't blown in, the hemp would have given the birds about as much protection from the wind as a picket fence. Those little tumbleweeds can turn some thing as worthless as an 18-inch-wide fencerow into good winter cover if enough of them blow in.

"Now, don't get me wrong. A field like that has wildlife value. It might have been pretty fair nesting cover. But, we're concerned with winter cover now, especially here in the western part of the state.

"If you went out on a January day like today and looked at the same fields that held good nesting cover last summer, you wouldn't see much but a few grass stalks sticking out of the snow. Most of those are what we call 'cool-season' grasses, like bluegrass, western wheatgrass, smooth and downy brome and cheat grass. They're essential to the pheasant as nesting cover, but they're usually too short and fine, and mat down under a snowfall too easily to be much good as winter cover."

Lyman went on to explain that another general variety of grasses does the best job of housing ringnecks in the winter. "The 'warm-season' grasses like big blue stem, Indian grass and switch grass are very good winter shelter. They stand thick and high, and even when a bunch is bent over by snow or wind, there's a tidy little tunnel underneath. These grasses don't amount to much as nesting cover, but pheasants sure find them handy in the winter. I guess part of what we're trying to say is that pheasants need a variety of cover types to do well."

With the engine warmed up, the guns stowed and the thermos drained of coffee, Lyman popped the pickup into gear and aimed it toward a roadside diner a few miles away. "You know, during that whole sermon I just gave on winter cover, I'll bet I didn't mention the most important item. That's weeds. A good, thick weed patch is probably the very best winter shelter. And probably the next best is a plum thicket, or maybe a cedar tree. But,

"As far as the grasses are concerned, the pheasant has problems there, too. The warm-season species that provide good winter cover are not as popular among farmers and ranchers because they don't provide the best grazing. And the cool season grasses are needed for pasture about the same time the hen pheasant is nesting. You can't blame the farmer or rancher too much for the pheasant's troubles. That land's his livelihood, and he's got to make it pay. It's just too bad that economic considerations always seem to work against wildlife instead of for it.

"There's one grass that is valuable to farmers and also looks real good as habitat. I don't think this has been researched, but it seems to me that tall wheatgrass might have good potential. The spring growth could be grazed, and might also provide some nesting cover. Then, if the fall growth were left lightly grazed or not touched at all, it could provide cover. While western wheatgrass is undoubtedly tops as nesting cover, tall wheatgrass might function as nesting cover and also stand up well as winter cover."

After taking on a fresh supply of coffee, sandwiches, candy bars and the like, Studnicka and Lyman still had a few details to tidy up before dark at their duck traps.

"Nick, after we finish with the traps, let's head for Sac. We need more bait for the traps, and there's some gear there that I want you to take back to North Platte with you. While we're there, we might have time to check out the management area. There's all kinds of winter cover there," Studnicka suggested.

Two hours later, Studnicka and Lyman were poking around Don's home base, Sacramento Game Management Area near Wilcox. About the first thing Lyman did was roust a dozen pheasants from a batch of knee-high cedars and routinely drop the only cock in the bunch with a blast from his trusty double. Fritz handled the retrieve with the style of an old veteran.

"That was too easy," Studnicka said. "We've got smarter birds than that one. There's bound to be some in a cedar thicket I know about, but we're going to have to to through some deep snow to get there."

Studnicka was right on both counts. It was a long haul through deep snow to the thicket, and it was full of birds. The plan was to "surround" the 40 by 60-yard tangle of cedars while Fritz waded in to flush the birds.

But the shifty ringnecks soon gave the hunters a lesson or two in tactics, showing them that it is impossible to "surround" a four-sided patch of cover with any fewer than four hunters. No matter how they adjusted their positions, the two hunters couldn't corral the birds. Pheasants always managed to find the gaps in the coverage and fly off. When it was over, a dozen or two pheasants had made their exits, and none had given an opportunity for a shot.

"The trouble with this place is there's too much cover," chuckled Studnicka. "There's all sizes and shapes of cedar thickets, some plum bushes, big fields of all kinds of grasses, and some wetlands. There's also combined milo stubble on private land nearby, and that gives the birds plenty of protection."

A hike through a nearby waterway ate up what little time remained, without producing any more ringnecks. "Two birds isn't bad for what little time we had to hunt. But next time, Nick, will you let me shoot a bird? About the closest I came to one today is when you let me carry yours," Studnicka chided.

Back at the management area headquarters, Lyman readied his pheasants for the freezer. "These birds are still good and fat. The weather's been pretty rough lately, but it looks like they've come through it O.K. The ringneck is a pretty tough ol' boy. If we leave him a place to raise his babies in the spring, and a place to get out of the wind in winter, he'll do the rest. We'll have pheasants in Nebraska for a long time."

WINTER SURVIVAL

(Continued from page 13)to a mild freezing of the skin surface from cold winds or touching of cold metal objects. The affected area turns greyish or whitish but can be warmed by a glove or mitten. After the nip is arrested, the skin will sometimes be red and a little tender. It is also highly susceptible to refreezing. If this stage is left unarrested, it will worsen to the second stage, which blisters after warming.

The third and fourth stages of frostbite are extremely serious; the skin turns a dark brown or black and tissue damage results in ultimate numbness. Frostbite should be attended to as quickly as possible. Those out in the cold should periodically inspect the most susceptible areas on each other, including the nose, ears, toes and fingers.

There are some standard treatments for frostbite. First, never warm the "bitten" area until you are sure that you will be out of the weather and the chances of refreezing are low or nonexistent. A refrozen body part is certain to be permanently damaged. Second, never rub the frozen area with anything-especially snow! This abrasion can cause severe harm and could result in permanent tissue damage. One should simply warm the area with lukewarm water (100-105 F.) or better yet, use only the body heat of an other individual to warm the affected area. Never use hot water or a hot fire. Remember, body temperature or thereabouts is the best cure. Never use alcohol on the bitten area or any other substance like iodine or antiseptics, even if blistering is present. Just dress the blisters with gauze and continue warming until the skin is soft, then immobilize the body part and get to a doctor. All of these treatments will work once frostbite occurs, but the best cure for frostbite is prevention by proper cold weather practices.

While frostbite is a serious cold-weather malady, the most devastating cold-related health problem is hypothermia or exposure. Hypothermia is a quiet killer that can claim your life before you know what's happening. As mentioned, your body at tempts to keep the body core and head at proper operating temperature, 98.6° F. If for some reason there is a problem in generating the necessary heat to do this, you fall prey to hypothermia and possible death. Though usually a winter problem, hypothermia can strike in mild weather as well. There are many ways that the body core temperature can get critically low. If you fall into a stream even during mild weather, the heating loss created can easily bring on hypothermia. However, cold weather is the critical time for this hazard.