NEBRASKAland

December 1974

NEBRASKAland

VOL. 52 / NO. 12 / DECEMBER 1974 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Fifty cents per copy. Subscription rates $5 for one year, $9 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. commission Chairman: James W. McNair, Imperial Southwest District, (308) 882-4425 Vice Chairman: Jack D. Obbink, Lincoln Southeast District, (402) 488-3862 Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-central District, (308) 745-1694 Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-central District, (308) 452-3800 Director: Willard R. Barbee Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, Jr. Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: Jon Farrar, Ken Bouc, Faye Musil Photography: Greg Beaumont, Bob Grier, Steve O'Hare Eayout Design: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1974. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska Travel articles financially supported by Department of Economic Development Ronald J. Mertens, Deputy Director John Rosenow, Travel and Tourism Director Contents FEATURES THE LAST WEEKEND 8 OLD-TIME CHRISTMAS 10 COLD COUNTRY 14 QUACKER BOXES 20 SPIDERS 24 THE BIG BULLS TRENDS IN LAND USE 32 34 PRAIRIE LIFE/PLANT MIGRATION 36 A QUIET GREATNESS 40 NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA/BLUE-WINGED TEAL . . 50 DEPARTMENTS SPEAK UP TRADING POST 49 COVER: The fox squirrel is a familiar sight to most residents of the state, as it can be found wherever trees provide cover and food for the rambunctious, bushy tailed acrobat. Photo by Jon Farrar. OPPOSITE: In a winter setting, coralberry or buck brush appears as pure decoration for the landscape, but is also a good wildlife food source. Photo by Jack Curran.

Speak up

AdulationsSir / I'm writing because I thoroughly enjoy your magazine! I moved to Florida the year Nebraska blitzed Alabama 38-6 in the Orange Bowl. I come from Atkinson, Nebraska and I must say I do miss it a lot. The people in Nebraska have a sincere quality that you will find nowhere else.

I also dearly miss the excellent hunting that the state affords. I come up every fall to take advantage of that. But most of all I miss Big Red. I don't think Nebraskans realize how much that team has helped our state gain recognition. Everywhere I go people say to me, "Oh, Nebraska, the state with the football team!"

I grew up on a cattle ranch that my parents still own. As a child I thought I was being deprived of something but did not know what. I have traveled throughout the United States and lived in five different states. I have come to the conclusion that Nebraska is one of the better places to live. Why don't I move back you ask? As soon as those winters warm up I will. Keep up the good work NEBRASKAland.

Gerald D. Greger Fort Lauderdale, Florida More AdulationsSirs / On vacation in Nebraska several years ago to visit relatives, I was spending some leisure time sitting around and found an issue of NEBRASKAland. I picked it up and started to thumb through it and was very impressed by the interesting articles and the fantastic photography. I was so delighted by this magazine that I sent in for a subscription and now I receive it in my home in Illinois. I would like to com mend the NEBRASKAland Magazine on its fine photography and stories.

Patrick Breyne Romeoville, Illinois CastigationSir / I am very disappointed with your magazine, especially because you seem to take such delight in seeing animals suffer or be killed. The picture of the antelope with the arrow in him (September issue), lying in pain, with that fellow seemingly enjoying it all, as he stands over him and smiles, is the last straw. Please cancel my subscription immediately because I don't enjoy seeing animals suffer.

Ann Delmastro Wethersfield, ConnecticutNEBRASKAland magazine is the official publication of the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, an agency supported to a large part by monies collected from the sale of hunting and fishing permits and indirectly by federal taxes levied on arms and ammunition. Were it not for this agency's antelope restoration program in the 50s and 60s, ongoing management programs and day by day protection afforded by conservation officers, it would be unlikely that anyone, hunter and non-hunter alike, would be fortunate enough to see dead or alive, a pronghorn in Nebraska.

Extensive agriculture is a fact of life in Nebraska and unlimited growth of big game populations is simply not in the cards. We are faced, then, with the need to maintain game populations at a level within landowner tolerance. Since hunters have made the greatest contribution to ward the proliferation of wildlife it seems only logical that the surplus should be harvested by them, a state of affairs that I might add has existed since our earliest ancestors raised up from all fours.

As for the young hunter's smile. Though the man in the slaughter house that sledged the cow from which your last steak came may not have been smiling, I would imagine that you did not grimace as you savored the end product of his killing. Killing is a fact of life. Some of us still live close enough to the land to recognize that. The term is perhaps blissful ignorance, when one can condemn legal hunting, and simply overlook all forms of com mercial killing. And, your subscription is herewith killed, although we hate to see that. Editor

More CastigationSir / Please say it isn't so. The saddest day I have had this year was the day I received my copy of NEBRASKAland (Post with a Past...and Future, June NEBRASKAland, Editor) that tells of the future rape of beautiful Fort Robinson. If you must have a Coney Island please go out and buy land at least ten miles from this wonderful spot. The Fort and surrounding land should have become a national monument many years ago and should have been kept out of the greedy hands of fun promoters. Have you people not learned of the turn around of the U.S. Park Service by trying to stop the desecration of our National Parks and Shrines. Please take another look at the decision to alter this last outpost and your best attraction out of the past. This is the only place that is genuine, the others are all fakes.

Peter J. Conroy Greensburg, PennsylvaniaFort Robinson would very likely not be in state ownership today if it were not for the long and dilgent efforts of this agency in obtaining title to it. That dates back to 1951, at which time we pointed out the advantages of acquisition and develop ment of the entire Fort Robinson Complex as a multi-use public area for wildlife management and as a terminal vacation park for the public.

Part of the Fort Robinson acquisition was a gift under the President's Legacy for Parks program. The larger portion was purchased for a nominal price. This transfer is based primarily upon civil rights compliance, and the use of the land to be "for public park and public recreation area purposes". The public purposes were for development and operation of a major state park as basically set forth in the Wilcox-Cummins Plan. This comprehen sive plan was prepared by public park experts at Colorado State University.

To dwell briefly on the Plan, it is based on three fundamental considerations:

(1) To so arrange facilities as to protect historic, scenic and natural history resource values while making them available for acceptable public recreation use in the most efficient and enjoyable manner possible.

(2) To provide a combination of facilities and services which will make it possible for the park to draw visitors from a wide enough area and from a broad enough economic population to justify the investment necessary to take full advantage of its resources for the good of the state. This includes service to residents directly, and indirectly to the state's regional economy and reputation by providing service to tourists.

(3) To design the area and a supporting recreation program to produce optimum recreation enjoyment at minimum cost. This includes significant income-producing services as well as traditional low-cost public recrea tion services. Especially, it requires efficient use of many existing structures over the period of time neces sary to change existing undesirable patterns of use into an effective park operation.

The State Game and Parks Commission is dedicated to building an outstanding State Park at the Fort based upon sound park resource and historic concerns. (Dale Bree, assistant director).

NEBRASKAland Magazine

and Nebraska Afield & Afloat

One Year $5

Two Years $9

The ideal combination for every

Nebraskan...whether at home or

far away. A new tabloid newspaper

joins NEBRASKAland Magazine in

keeping readers abreast of all the

latest in outdoor happenings.

Take NEBRASKAland and get

AFIELD & AFLOAT free every month.

NEBRASKAland

Calendar of Color

Only $2

plus tax

Back by popular demand, the Calendar

of Color is better than ever. The

only all-Nebraska calendar, it boasts

the old favorite features and a few

new ones, too. It's just the right

gift for those folks on every list

for whom a card is not quite enough.

NEBRASKAland Magazine

and Nebraska Afield & Afloat

Please Christmas Express Subscriptions to:

One year $5 Two year $9 Name

New Renewal Address

City State Zip

One year $5 Two year $9 Name

New D Renewal Address

City State Zip

One year $5 □ Two year $9 Name

New D Renewal Address

City State Zip

One year $5 Two year $9 Name

New Renewal Address

City Sign gift card or envelope with: State Zip

Compute Your Own State Sales Tax

Omaha and Lincoln 31/2% Outstate 21/2%

SALE TAX SALE TAX

2.00 .07 2.00 .05

4.00 .14 4.00 .10

6.00 .21 6.00 .15

8.00 .28 8.00 .20

10.00 .35 10.00 .25

12.00 .42 12.00 .30

14.00 .49 14.00 .35

16.00 .56 16.00 .40

18.00 .63 18.00 .45

20.00 .70 20.00 .50

No sales tax required on NEBRASKAland magazine

No sales tax required on calendars sent outside Nebraska

Christmas Express Order Form

Calendar of Color

Please Christmas Express Calendars to:

Quantity Name

Address

City State Zip

Quantity Name

Address

City State Zip

Quantity Name

Address

City State Zip

Quantity Name

Address

City Sign gift card or envelope with: State Zip

CHRISTMAS EXPRESS TOTAL

No Stamps or Cash Please

CALENDARS ARE MAILED AT

NO EXTRA CHARGE ON THIRD

CLASS BULK RATE. HOWEVER,

ORDERS RECEIVED AFTER

NOVEMBER26ARENOTGUAR-

ANTEED TO ARRIVE BEFORE

CHRISTMAS.

CALENDARS @ $2.00 $.

SALES TAX $_

SUBSCRIPTIONS $_

GRAND TOTAL $_

NEBRASKAland* P.O. Box 27342* Omaha, NE 68127

6

NEBRASKAland

Gifts

from

NEBRASKAland

NEBRASKAland Magazine

and Nebraska Afield & Afloat

One Year $5

Two Years $9

The ideal combination for every

Nebraskan...whether at home or

far away. A new tabloid newspaper

joins NEBRASKAland Magazine in

keeping readers abreast of all the

latest in outdoor happenings.

Take NEBRASKAland and get

AFIELD & AFLOAT free every month.

NEBRASKAland

Calendar of Color

Only $2

plus tax

Back by popular demand, the Calendar

of Color is better than ever. The

only all-Nebraska calendar, it boasts

the old favorite features and a few

new ones, too. It's just the right

gift for those folks on every list

for whom a card is not quite enough.

NEBRASKAland Magazine

and Nebraska Afield & Afloat

Please Christmas Express Subscriptions to:

One year $5 Two year $9 Name

New Renewal Address

City State Zip

One year $5 Two year $9 Name

New D Renewal Address

City State Zip

One year $5 □ Two year $9 Name

New D Renewal Address

City State Zip

One year $5 Two year $9 Name

New Renewal Address

City Sign gift card or envelope with: State Zip

Compute Your Own State Sales Tax

Omaha and Lincoln 31/2% Outstate 21/2%

SALE TAX SALE TAX

2.00 .07 2.00 .05

4.00 .14 4.00 .10

6.00 .21 6.00 .15

8.00 .28 8.00 .20

10.00 .35 10.00 .25

12.00 .42 12.00 .30

14.00 .49 14.00 .35

16.00 .56 16.00 .40

18.00 .63 18.00 .45

20.00 .70 20.00 .50

No sales tax required on NEBRASKAland magazine

No sales tax required on calendars sent outside Nebraska

Christmas Express Order Form

Calendar of Color

Please Christmas Express Calendars to:

Quantity Name

Address

City State Zip

Quantity Name

Address

City State Zip

Quantity Name

Address

City State Zip

Quantity Name

Address

City Sign gift card or envelope with: State Zip

CHRISTMAS EXPRESS TOTAL

No Stamps or Cash Please

CALENDARS ARE MAILED AT

NO EXTRA CHARGE ON THIRD

CLASS BULK RATE. HOWEVER,

ORDERS RECEIVED AFTER

NOVEMBER26ARENOTGUAR-

ANTEED TO ARRIVE BEFORE

CHRISTMAS.

CALENDARS @ $2.00 $.

SALES TAX $_

SUBSCRIPTIONS $_

GRAND TOTAL $_

NEBRASKAland* P.O. Box 27342* Omaha, NE 68127

6

NEBRASKAland

Gifts

from

NEBRASKAland

Scarcity of pheasants had us wondering if they had migrated, then we found them by the score

The Last Weekend

Photograph by Lowell JohnsonIT WAS A COLD, blustery day with a chilly wind that continued to move recently fallen snow into drifts which closed sheltered spots on county roads, and it would mean several detours trying to get from one place to another. But, it was the last weekend of the year, and conditions were good for pheasant hunting.

The ringneck season continued into 1974, but the final weekend of the year seemed like an auspicious time to seek out a few birds before they got any older and wiser. I had gone to my old stamping grounds at Holdrege, and it was no difficult task to talk a couple of cronies into a few hours afield. Thus it was that with only a feeble light of dawn competing with streetlights, I pulled into Danny Jordan's yard, hoping he would be up so I wouldn't have to ring the bell. He was, so we proceeded to round up the third member of our party, Orval Harms, just a few blocks away.

After comparing snow tires to see which vehicle offered us the best chance at negotiating the roads we expected to encounter, we loaded gear into Orval's station wagon and sneaked out of town.

Living and hunting amidst some of Nebraska's prime irrigated farm country since they were sprouts gave both Danny and Orv a real advantage in select ing hunting spots, but the cold and recent snow had prompted changes in the habits of the birds. So, many of the dependable areas earlier in the season were now avoided in favor of different cover types.

So-called canyon country begins just a few miles south and west of Holdrege, and as the driver always has his first option, that was where we appeared to be gravitating. The most exciting thing that happened for quite a while, however, was figuring out a route through the drifted-over roads. Never having been fond of standing in snow up to my navel trying to extricate a bogged-down vehicle, I urged utmost caution when approaching a choked road. Orval, how ever, seems to find all such situations challenging and would only back off and go around if getting stuck was an absolute certainty.

After several episodes which included my squashing the top of the front seat between whitened knuckles, we found an open road and some likely looking cover in reasonable proximity. It was a distance out to the cover, and it was really tough to hunt because snow had drifted in around it to a depth of several feet, but the complete absence of any birds was perhaps its most notable feature.

Trudging back to the car, attempting to follow our same deep footprints, at least took our minds off the lack of other action, and conversation was light because of the heavy breathing.

Within a few minutes, though, Danny was back in a jovial mood and quickly took up on my innocent comment about all the rabbit tracks and a road-killed jack. Wherever the wind hadn't obliterated them, the tracks were abundant. My comment brought to mind a story about some relative of Danny's who one time was also in a car when road-killed rabbits had come up. "Those are valve-jacks," his relative had said.

"Valve-jacks," responded the other innocent person —"what are those?"

"Well, they are a breed of rabbits around here which lie in wait for unsuspecting motorists, and when they pass by their lair, they dash out and bite the valve stems on the wheels. Of course, it's like the bee that dies after stinging you-they are killed in the process."

Fortunately, another likely looking pheasant hangout appeared before we had to make any comment on the rabbit story. It was a large corner plot of federal waterfowl production land, with signs that proclaimed it as public hunting.

"Now, there will be birds in here," Danny prophesied, opening his door to let in a gust of frigid air.

With nothing to do but follow, Orv and I put on grim expressions and gloves. Numerous bird tracks along the edge of the field, amid short plum brush and the adjacent corn (Continued on page 42)

Old-Time Christmas

Prints courtesy of the State Historical SocietySEASON BY SEASON, the years slip into decades and decades into centuries. The world or man changes at an ever faster pace. And yet, whatever the outer trappings, some things never really change. Christmas is like that. It was, is, and hope fully ever will be that very special time when the inner spirit seems to glow with good feeling. Church bells still ring the call to worship a Babe in a manger. Children still painstakingly pen their letters to Santa and carefully hang their stockings in anticipation of his visit. Clans gather and the warmth of family banishes the howling north winds. Holly wreaths, yule logs, Christmas trees, caroling, a fire in the hearth, roast goose and all the trimmings, and gifts lovingly wrapped and tied . . . all this and more we share with our pioneer forebears. When times were lean, the extras were sparse, but the spirit of Christmas was ever there. Even the stars seem to shine a bit brighter as the yule season approaches. For a glimpse of Christmas past, NEBRASKAland borrowed from the pages of Harpers Weekly to bring you a nostalgic glimpse of yesterday. Was it real ly so very different? Styles have changed, but overall Christmas is still that very special time.

Prints Courtesy of Nebraska Historical Society

Prints Courtesy of Nebraska Historical Society

Cold Country

OLD MAN WINTER showed he still had some of his vigor left as he brought winter back to Nebraska this year. With a roar and a fury, he stacked snowflake upon snowflake until the once flamboyant colors of fall were left standing bare in winter's grip. Even the cold, crisp dawn was late in coming, almost as if the old man would yield to no one once he had found his might. When the sun's rays did pick their way over the brim of winter, they brought with them not only false hopes of warmth, but also a strange sort of light a light which was reflected into the very darkness of the mind to yield new thoughts and patterns of life and nature. A cold, crisp beauty burned the lungs with pain but warmed the body with wonder, and prevailed over the land. Common-day scenes became things of beauty no longer resembling their past or their future. With this blanket of snow and the cold, winter gave us a rare opportunity to see as the artist— when only the beauty and form are observed and felt.

Even with the old man's ability to hide the ugly and bring forth the beauty which was hidden, some people still envision winter as cold, harsh and unyielding as spring is warm, soft and forgiving. They dream warm thoughts and complain of the boredom winter brings. Ah, but to walk in the crushing cold of a pre-dawn winter morning when the very act of breathing reminds one he is alive! And, to witness the sun rising over the horizon giving the mystic, golden light of dawn the King Midas's touch. Who has not experienced the beauty of a tree, not clothed in green or yellow, but by the very heavens which surround them? One can see the little things which are hidden from man all but once, as icicles changing from day to day as the sun, like a sculptor, adds to or takes away from his creation. Or, a weed that overnight acquires a bejeweled crown, transforming the commonest of life to regal status.

In the deathly quiet of winter's grip, objects take on a solitude

and loneness, but in so doing they stand out even more. The fence

row, once busy amid growing things, now seems to need the snow to

support it. Perhaps the battered decoy, lost from some great hunting

expedition, will gradually return to the earth now that it is as free as

14

NEBRASKAland

DECEMBER 1974

15

Maybe old man winter was not such an ogre as we thought when

we were afraid to venture out into his world. Sure its cold, and even with heavy mittens one can still feel his nip, and there's all that snow to be shoveled. But there is such a vastness of power in the old man's hand; how he can change the ugly into beauty, the simple into grand, the boredom with life into enjoyment of living and seeing. If one can just venture out and really understand the old man, then it is to know that winter means more than tired backs and vague thoughts of far away lands where winter never shows his hand, nor his magic.

Quacker Boxes

...are wire cages to trap ducks in frigid January

ALL WE COULD hear was the crunching of snow underfoot as Dan Rochford and I plowed our way through 10 inches of the frozen powder. We were heading for the Republican River and the duck traps we had set the night before. A cloudless January dawn was broken only by the misty steam rising from open water which left the dam and splashed its way over the broken shale bottom. Each degree below the zero mark seemed to take its toll on my fingers; 1 degree, 1 finger. With the thermometer stuck on 10 below, my pinkies didn't stand a chance.

The ducks looked rather chilly themselves. They rested in six large rafts of nearly solid bodies. Each group resembled a barge made of tiny bar rels tied front to back and side by side.

Our steps seemed to get louder and louder as we approached the river. We stopped a few feet from the water and watched as the ducks removed their bills from the warmth of their wings, and as if by some command, began peeling away from the rest of the sleeping squad.

It didn't take long before we be came the main attraction. Suddenly the air was full of quacking, flapping creatures. Exploding from the water in a continuous rhythm they seemed to use each other as stepping stones towards greater height and its result ing safety.

As a new employee of the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, I didn't realize the sight would become such a familiar one during the next few days. To Dan it was old hat. My part ner, a wildlife biologist for the Game and Parks Commission, was making his third trip in as many years to the tailwaters of Harlan County Reservoir south of Republican City. Our goal was to trap and band 400 mallard ducks. This number consisted of 100 adults and 100 adolescents of each sex.

With the water and air now unoccupied, my attention turned to the thrashing and splashing of captured ducks. The seven traps looked like tiny ice castles scattered randomly down the river. The trapped ducks only showed themselves during futile attempts to escape as they came in contact with the wire trap tops of the frozen fortresses. The confines of the trap grew smaller and smaller as the splashing ducks added extra coats to the icy, wire walls.

As we made our way to the first trap my thoughts drifted back to my first day in the office. Jim Wofford, Division Chief of Information and Education, told me as part of my on-the job training, I should stick my nose into everyone else's business and be as inquisitive as possible. A few weeks later my snooping led me to Dan's office in the Terrestrial Wildlife Division. Before I knew what had hap pened, I was trying on breast-waders, insulated coveralls and a wide assort ment of gloves.

"Try one of these rubber surgical gloves on your left hand. That's the one you'll be handling the birds with the most, so it'll get the wettest", Dan instructed.

I watched now as water swirled around our legs and splashed onto our waders. As it turned to ice the moment it hit, those rubber gloves inside jersey gloves and those inside leather gloves, were rather comforting.

Upon reaching the first trap, it was obvious what Dan was trying to prevent as he backed in the last few feet. It was already too late for me. A watery spray hit me square in the face. All I could think of was my black lab returning to the blind after a retrieve and wringing out every hair on his body. If you are anywhere close when the shaking begins, you've had it. As I turned a tardy and useless about face, I heard Dan laugh and mumble something about live and learn.

Shelled corn we had used for bait was gone. Every crack and crevice of the shallow river bottom was empty where the evening before it had been covered with golden nuggets.

The catch box we carried resembled a large wire footlocker. It had a slid ing door which seemed to freeze shut every time we reached a trap. A tire iron was used to break the ice coat ing from the traps, revealing their small doors. After hitting the catch box a few times to loosen the door, the mouth of the box was placed against the opening and the ducks herded in. A good shove on the catch box door insured their capture.

We then hauled the ducks out of the river to a comfortable working area on the bank. Five or 10 ducks to a load wasn't too bad, but our record haul of 37 barely made the trip with out mishap.

We took the ducks from the catch box and inspected each one. First we checked for previous bands. Ducks wearing old bands are called "recaps," and these numbers were re corded, along with the age and sex, before the birds were released. Ducks not wearing previous bands were checked for age and sex. These were recorded alongside their new band numbers as the shiny strip of alumi num was attached. The duck, wearing its new ankle bracelet, was then released to rejoin the other free birds.

One recap, a mallard drake banded in an earlier project, passed through our catch box three times during our five-day visit. He knew the ropes by then and probably thought a free meal was worth the brief hassle.

Aside from being an excellent biologist, Dan is one of the better teach

ers I've seen. He knows his work

completely and is able to operate

under extreme conditions. The cold

weather and my constant barrage of

dumb questions certainly created

some extreme conditions for him.

What's this? What's that? How can

you tell their age? How many are

20

NEBRASKAland

DECEMBER 1974

21

there? Where did they come from?

Where are they going? The list was

endless, but Dan answered them all.

there? Where did they come from?

Where are they going? The list was

endless, but Dan answered them all.

As we banded, he explained the purpose behind our task and the part it plays in the overall project. "Our site here below the dam at Harlan is only one of six banding locations we use in the state. Nebraska, along with many other states, works with the Bureau of Sport Fish eries and Wildlife on a federal duck banding program. With the majority of our waterfowl being produced in the south-central pothole sections of Canada, the birds must travel across many states and national borders as they make their yearly migration. The 400 ducks we band are only a fraction of the total number of ducks and geese that receive bands across the United States, as only about 17 percent of the birds are banded in Nebraska. From the bands returned by sportsmen in the U.S., Canada and Mexico, we can determine the migratory flight patterns of our waterfowl.

Dan went on to explain how the hunters, whose license fees finance such banding projects, profit by returning the bands. With data provided from band returns, reseachers can figure the present condition of a population of waterfowl. In many cases, this brings about more liberal hunting regulations rather than more restrictions. In some areas, hunters will not return bands thinking a high harvest of recorded birds in one area will bring about smaller limits in subse quent years. This practice only back fires on them. Failure to return bands results in a lack of population infor mation.

Therefore, the existing population appears slim, forcing biologists to impose more restrictive hunting seasons in the form of smaller bag limits. This measure would protect the seemingly sparse resource —waterfowl.

Wildlife biologists throughout the nation work in the interest of sports men and the resource. Without a working relationship between such projects as ours and the hunting public, waterfowl management would be nonexistent.

At the end of the first day I lay in bed and thought about all the time and effort people put forth in such projects as ours. Hunters everywhere profit, yet how few are really aware of what goes on before a duck reaches their dinner table. As I drifted off to sleep I wondered if my feet would ever warm up.

It was apparent after four days of trapping that the females were harder to trap than males. For all you women's libers—they are probably smarter, but they did seem less aggressive and were outnumbered 2 to 1 by drakes. These factors entered in, I'm sure.

With all the males banded the first three days, the little brown females became our main concern.

The severe weather conditions, sub-zero temperatures and a heavy snow cover resulted in only a limited amount of open water and available food for the wintering flock of approximately 7,500 ducks. These factors made trapping the best it had been in three years. With only 44 females to go we decided to run the traps twice a day instead of just once.

On the morning of the fifth day we trapped, banded and released 18 females. We also released the males after checking and recording recaps. After five frozen days of trapping, only 26 bands remained unused. I was enjoying the job, but the possibility of wrapping it up that afternoon was rather appealing. Compared to the 400 we started with, 26 bands didn't seem like much.

When we entered the river that afternoon the traps were loaded with mallards and there seemed to be a lot of brown. Only after working all seven traps did we realize we were three females short.

We decided to clean, reset, and bait the two most productive traps. The rest were placed on the bank to be picked up later. With the number of ducks circling the open water, we figured we should be able to easily trap three females in the remaining hour of sunlight.

Dan decided to spend the time doing another sex-ratio count from atop the dam. His count ended up about 2.3 to 1, males over females. I grabbed

From his vantage point, Dan could see there were ducks in our traps, so he honked the horn and started his descent. The beam of headlights illuminated falling snow as the truck rounded the last bend in the road.

We met at the first trap; five drakes. I could see it now —another whole day for three little hens. After releasing them, we carried the catchbox to the last trap of the day.

"Look at the clucks in that trap!" Dan said as we approached the splashing mass of ice, wire, and feath ers. The line of ducks entering the catchbox just didn't quit.

"Looks like a lot of green to me," I said. Dan's face showed agreement.

We checked and released all the males and still had four brown beauties in the box. One was a recap, and then there were three. With the next two bands snuggly in place and the ducks on their way, the last band slipped off the tube. The special little hen was taken out of the box. As I recorded, Dan reported, "mallard, female, adolescent."

Dan seemed to be extra careful not to pinch the band too tight. As I looked at her, I realized that once she flew away our river visit would be over.

All I had learned and seen the last four days seemed to be reflected in her shiny black eyes, She was part of a wonderful natural resource that needed our help. It was strange, but all the discomfort, frozen fingers and all, seemed worth it.

Dan set her gently on the snow. Her new band reflected what little light there was left in the sky. She stayed only a moment, then lifted off and flew silently into the snowy dark ness.

It was really kind of sad until Dan said, "Bet I catch her next year!"

Drakes we captured in droves. But, we needed hens. In waning bit of sunlight, we found a leg for last band

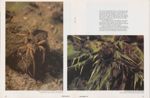

Astounding in number, these creatures are mostly beneficial to man

SPIDERS

SPIDERS BELONG to the phylum Arthropoda (a Greek word meaning "jointed foot"). Also included in this huge phylum are the lobsters, crabs, crayfish, shrimps, barnacles, water fleas, centipedes, millipedes, insects, scorpions, ticks and mites. Of all the known animal species, 78% fall into Arthropoda, making it by far the dominant animal group on earth.

Although spiders share the same phylum with insects, they are placed in a separate class because of several important distinctions. Among the more conspicuous differences; spiders have only two body regions instead of three, lack antennae, possess four instead of three pairs of legs, have no wings and do not go through the various distinctive stages of development that characterize insects. Together with harvestmen, ticks, mites and scorpions, they belong to the class Arachnida. Spiders alone comprise the order Araneae.

An ancient lifeform, spiders as we now know them were in existence in the Carboniferous Era. The ancestral stock from which spiders evolved is unknown; there is no evidence that spiders evolved from any particular group of arthropods or that they are descendents of any living or extinct group of arachnids. It is therefore possible that they are a derivitive from the very ancient trilobite that ruled the Cambrian seas.

Of the 30,000 known species of spiders, about 2,000 are found in the United States. Spider densities tend to be high and account for a large proportion of the animal population of any given area. Estimates put spiders at about 14,000 per acre in temperate woodland and 64,000 per acre of meadow. Such numbers indicate the contribution spiders make in controlling insect populations.

While some species possess powerful jaws, allow ing them to crush their prey, none has mouthparts adapted to chewing or swallowing flesh; as a result, all spiders must subsist by sucking the body juices of their prey. Small or weak-jawed spiders rely on their venom to subdue victims while at the same time injecting digestive fluid; after the body tissues of the prey are broken down and predigested, the liquid mass is sucked out by the spider's powerful muscles. Large-jawed spiders will crush the bodies of their prey while bathing the pulp with large amounts of digestive fluid; as the prey is turned and crushed and the liquified tissues drawn off, it rapidly dwindles to a mass of dry, empty shell.

As a group, spiders have adapted to almost every ecological niche. Found in caves, under water, even surviving the extremes of climate found on mountain tops, they represent one of nature's most successful and durable experiments in specialization.

Some species, such as the wolf and jumping spiders, rely on keen eyesight and swift movement to secure their food; others, such as the flower-hidden crab spiders, rely on camouflage and patience, await ing the opportunity for ambush; some construct simple and haphazard snares, rushing upon whatever might become momentarily entangled; others lay down a sheet web in the grass or corner of a building and bide their time, concealed in a tunnel of protective silk. It is the orb-weavers, however, that labor the hardest for their meals and have most captured the awe and admiration of man.

Folklore is replete with the web-making spider a model of industry, patience, skill or treachery. It is not surprising that such a creature found a prominent place in the myths of many primitive peoples. The Pueblos attributed to the spicier a main role in creation. In many cultures, man was supposed to have learned the art of weaving from benevolent gods appearing in the guise of spiders.

Superstitions still surround the spider even among civilized peoples —sightings of spiders at certain times of the day will bring good or bad luck; killing a spider brings rain; clear weather will follow if cobwebs are sighted on the grass in the morning; black spiders are evil and portend disaster, etc. Spiders are oviparous; reproducing by laying eggs which hatch outside the mother's body. The eggs are placed in an egg-sac, which affords the eggs protection

until the spiderlings hatch. In some species, the sac may be nothing more than a few strands of silk to bind the egg mass together; in others the sac is thicker but still a poorly defined fluff of silk, looking like a spot of cotton. In most, however, the shape of the egg sac is distinctive and the species of spicier may be identified from it.

Since spiders possess exo-skeletons, the young must molt in order to grow; the number of molts determined by the adult size of the species. After the final molt, the spider is sexually mature.

Males in most species are smaller than females, sometimes drastically, so as to bear little resemblance to the female. Constitutionally, males also tend to be weaker. When an orb-weaver leaves his web to

seek the web of a female, his chances of survival are greatly reduced. Exhaustion often leads to predation by other animals. Since he has forsaken his web, and thus his ability to capture prey, the male may starve before discovering the goal of his wanderings, or be so weakened by the ordeal that he fails at "courtship" and mating. At such times he may actually fall prey to the very female he is trying to court, giving rise to the myth that the females of all species tolerate mating only to obtain an easy meal.

Certainly the male must use caution in approach ing his prospective mate, and must clearly identify himself and his purpose so as to short-circuit the female's instinctive aggression. In the family of spiders which rely on keen vision to obtain prey, the male employs a particular dance or distinctive posturing to serve notice to the female. A different tactic is required with the web-makers, whose vision is generally poor and who depend instead on a highly developed sense of touch to locate prey. When a male web spider discovers the web of a female of his species, he will begin plucking the strands of her web in a distinctive manner, continuing to do so as he advances; in effect, he is using the female's web as a telegraph, and her sensitive feet receive a message which in no way resembles the frantic SOS of a snared insect.

In the United States, the life span of most spiders is about a year, usually governed by the seasons. Many species possess the capability to over-winter, either as young or adults, if adequate protection is secured. The iarge wolf spiders, which become conspicuous in the fall around buildings as they seek a winter retreat, may survive several years.

All but a very few of the most primitive spiders utilize silk. Even those which do not construct snares will make use of a dragline; this "safety rope" permit ting a spider to escape a predator and then quickly return to its original position, bridging gaps between plants, and allowing ballooning, a unique process whereby a spider lets out a dragline into the wind until the force is sufficient to carry it away. We all know the "gossamer days" of spring and fall when millions of newly hatched spiderlings go ballooning and the sky rains silk.

More unfortunate than the superstition and misinformation which still cloak the spider with mystery is the general aversion most people feel toward any thing "crawly" or sinister-looking. Though aggressive

carnivores, spiders are nevertheless shy and retiring in the presence of larger creatures since they them selves are heavily preyed upon by birds, amphibians, reptiles, many mammals, certain wasps and other spiders. In North America, man need fear the bite of only two species—the legendary Black Widow, Latrodectus mactans, and the more formidable Brown Recluse or "Fiddleback," Loxosceles reclusa. While the venom of these spiders is fantastically potent many times moreso than rattlesnake venom —the amount injected is normally quite small and prompt medical attention will usually nullify its effects. Wasp and bee stings represent a much greater danger and are responsible for more fatalities in the United States than snake, scorpion and spider insult combined.

When a housewife is introduced to the sport of goose hunting, she thought it would not be important. "The hunting bug will never get me," she said

THE BIG BULLS

Photograph by Greg BeaumontTOWARD THE END of July, the Canada Goose, also known as the "Big Bull," works his way into the summer fishing conversation. Anticipation builds as everyone waits for the hunt ing dates and bag limits to be announced. Phone calls for reservations in my husband's goose pits (since everyone wants to be first) start early. Hunting stories unwind, complete with exciting sound ef fects and appropriate animation. Everyone has his eyes on the sky, hoping to catch a glimpse of the first formation winging its way south.

My indoctrination to hunting began slowly enough; Bill and I were married three years ago, be fore the hunting season. Conversation, and my will ingness to learn, were the only educational factors carrying me into my first hunting season. Sometimes I felt a little left out as the great hunting stories unfolded. Coming in as a "city dude," which is what Bill calls anyone brought up among city living, my only experience with a goose was the one we ate for Christmas dinner. It took a few weeks just to learn the hunters' language: "snow" is not always on the ground; "blues" are not part of a Navy wardrobe; and the "Big Bull" was not out in the pasture.

Under the verbal direction of my husband, my introduction to a gun, a 12-gauge, full-choke pump obviously built for someone with very long arms, was a painful and angry one. My arm was not black and blue —just black.

"That is not a broomstick! Keep your eyes open or you'll never hit anything! Get that safety on!" Bill would shout.

Irish stubbornness saw me through, somehow, and graduation day finally arrived. My "diploma" was a 20-gauge, double-barrel for someone with short arms. But, I later became mighty grateful for all the pre-season lessons I had received.

Like any new eager beaver, it was not difficult to enlist my help to get the goose pits ready. Little did I know what was involved. "Double disc" and "double drill" the field to make a "good looking pad," were new expressions to add to my hunter's vocabulary. Instead of implying that I was ignorant, Bill explained it was necessary to have a solid green field in front of the pits to show off the stuffed decoys and encourage the geese to come in. In order to do this, it was double disced and drilled, and then hand sewn where the rough spots still showed through.

Cleaning the pits after they had been filled with rain and lived in by assorted animals, didn't seem to have anything to do with hunting. I was beginning to wonder, by this time, if it all was worth the goal. When we hooked up the butane heaters and put cushions in, I was at least assured of comfort and warmth. Covering the pits to disguise them was another chore that did not lead me to believe hunting would ever be my cup of tea, but the "G-onk" of the home flock spurred us on toward being ready for the big day.

When the big day arrived, I met the challenge of 5 a.m. reveille, but not very enthusiastically. The only thing that had ever gotten me up before 10 a.m. was work. It still seemed like a lot to go through just to shoot a bird! I was positive the hunting bug would not bite me!

The object of going so early was to be in the pit, loaded up, decoys set, and mentally attuned to listen ing and watching for the birds as daylight broke. There is no way to explain the sounds and commotion on a game reserve when every species of goose gets up and starts out to feed, but try to imagine 50,000 birds talking to each other.

When the flocks return from feeding, hearing them long before seeing them gives one the opportunity to identify the "G-onk" and bawl of the Canada, the jazz-band sound of the specks, radar beeps of the snow and teasing "Ha, Ha, Ha" of the mallard ducks.

Bill spotted a flock coming our direction and started calling. The tension began to build-sitting there not daring to breathe, listening to the special communication between the caller and the "big goose". We watched the lead goose coming high over the top, his head down, turning and looking, checking out our spread. The goose called; Bill answered; back and forth they talked. Will he turn and let down?

"They're coming," he whispered. "Get ready." Everyone grabbed a gun, waiting for the moment when they seemed suspended in air, as if hanging on a string; wings outspread, bodies buckled, feet down. "Get 'em," shouted Bill.

Get up and out, ready to shoot, without hesitating! Learn that quick, or end up with an elbow grow ing out of each side of your head. Being female doesn't count; if anything it makes it more difficult. The excitement during that first round was at its peak. One guy leaped right over the top of the pit, leaving his gun behind, to rescue a winged bird. Everyone was proudly announcing: "I got mine," when Bill pointed out that there were 4 downed birds and 10 shooters.

Everyone reloaded and settled down for the next bunch, ready to down the one they didn't get the last time. My decision was to keep my eye on Bill and be the first one out this time. Bill spotted a loner and began calling.

This goose is a permanent hole burned in my memory. He turned and came in so close, I could swear I saw his eyes blink, just a little to my left. Bill finally said, "Take him." I jumped up, fired, and the goose dropped. Looking around to see who was going to claim him, I was surprised to find no one else had fired. I had shot my very first goose! "Well, guess who killed that one?" I challenged. I was beside my self with excitement, doing something I was not sure I could do.

As we waited for the next bunch, and the next, each shooting different from the last, I still felt tomorrow would be just another day. The hunting bug would not bite me, even if! had shot my first goose. "The Big Bull" would not obsess me like most hunters.

On the way home that evening, Bill asked what I thought about the whole hunting business.

"Could I learn to blow a call? Can I still hunt when you're booked up?" I asked. "Can I clean up the pit that's not in use and shoot out of it?" I rambled on. We both started laughing. "Guess who just got bit by the bug?" Bill teased.

Three years of hunting have not dimmed the thrill for me. This year, like everyone else, I'm wait ing; telling my own stories, practicing on the call, polishing my new 12-gauge automatic and readying for opening day, my hunting buddies, and shooting the "Big Bull."

TRENDS IN LAND USE

Oren Long is a Kansas farmer with degrees in philosophy, political science and a master's in environmental science, and also employed as an agricultural specialist with the federal government Now 50 years of age, Mr. Long grew up on a Missouri farm, served in the U.S. Navy during both World War II and Korea and now farms in Kansas. He is also pursuing a B.S. degree in systematics and ecology, and this article came about as result of a six-nation European tour he made in 1973I RECENTLY COMPLETED a 2,000 mile back-pack and bicycle tour through the rural areas of Luxembourg, France, England, The Netherlands, Belgium and Germany to discover how effective the various agricultural land uses found in these countries were in controlling nonpoint pollution and in providing a good rural environment. It was my hope that the European experience could assist this nation in its efforts to do a better job in controlling agricultural land uses.

My suspicions proved correct—Europe does have much to teach us in the techniques of good farming and constructive land uses.

I first began to think about a grass roots tour through the rural areas of Western Europe when land-use legislation began to be seriously discussed. I realized that controls on how farm ers could use their land was closer than most people realized, and the nature of those controls was going to be extremely important to every land owner. And, when the Environmental Protection Agency began to suggest that states seriously consider ways of controlling stream pollution from soil erosion, I felt it was important to learn as much as possible about what other countries have done in this area. So, I sold a couple of cows to cover my travel expenses and set off for Europe. I wanted to do everything possible to see that land-use regulations are both reasonable and justified. After all, these regulations will affect my farming operation too.

My trip plan was to find out what was actually going on in the country side and not what the government said was happening. From personal experience, I knew that conflicting views often existed. So, during my trip, I spent a (Continued on page 46)

Prairie Life/ Plant Migration

INDIVIDUAL PLANTS are rooted in one spot, but there is one time in their life history when they can be very mobile. During their reproductive stage, plants, just as surely as the wild goose, can migrate.

This change of location is accomplished in a number of ways. Buffalo grass sends out ground runners that anchor periodically to the prairie soil and start new plants. The wild raspberry of the flood-plain forests sucker profusely, or, when the tips of their canes dip to the ground, may root and establish daughter plants. The brittle twigs of sandbar willow start new plants if they fall on moist, favorable sites. These are examples of plants reproducing vegetatively, without benefit of seeds.

More common, and certainly more spectacular, are the modes of travel exhibited by a plant's seeds or fruits. Plant seeds move from place to place by using forces of nature like wind, water or gravity; by catching rides on passing animals; and in some cases by propelling themselves.

The most ubiquitous force of nature, especially on the prairie, is the wind. It is little wonder that many plants have specific adaptations permitting them to tap this reliable source of power. To ride the wind, plants needed only to evolve seeds that exposed a great surface area relative to their weight.

One of the most efficient of these wind-catching structures is the pappus or "parachute plume." About one sixth of all American plants, the composites, have evolved this simplistic yet functional design. The plumes of the dandelion, and other herbs such as the false boneset or yellow goat's beard, are spread horizontally to catch and hold updrafts. Cottonwood, willow and milkweed seeds have tufts of silky fibers attached to their seeds that help them drift with the wind. Collectively, these plants are the masters of the air within the plant kingdom.

To further enhance travel by air, many plants, over millions of years of development, have replaced the bulky starches in their seeds with lighter oils. Oils provide as much nourishment to developing plant embryos and at the same time help lower the seed's weight-to-surface area ratio.

Other plants have flat, sail-like wings attached to their seeds. The shower of seeds that drift from trees like the American elm, green ash or soft maple, demonstrate the effective ness of seed dispersal by gliding.

As a rule, trees have winged seeds and herbaceous plants have plumed seeds. When the growth habits of these two groups of plants are considered, the reason for this segregation of seed types becomes obvious. Plumed seeds are designed to catch and ride up-currents, while winged seeds are best designed to make whirling or gliding descents. Seeds launch ed from a tree's great height drift a sufficient distance to reach favorable sites. Heqbs, on the other hand, are relatively low growing and require the lift of the wind to carry their seeds to new locations.

Some botantists, convinced of the plume's superiority as a mode of seed dispersal, have suggested that plume seeded plants appeared later in the evolution of plants than did trees. The winged seeds of trees, they believe, are a less efficient, more archaic means of plant travel.

Tumbleweeds utilize the wind to spread their seeds in yet another way. Throughout the growing season, these plants are anchored to the soil by the most minimal of roots. As their season ends, the plants dry into brittle balls, heavy with seed. The first wind strong enough to rip their roots from the soil sends the plants bouncing across the prairie, disseminating seeds as they go. Man and his fencerows have unwittingly aided the tumbleweed by stopping whole drifts of plants at the very sites best suited to their colonization—undisturbed roadsides.

Some plants, rather than evolving specific structures to drift in the wind, have made use of the physical law that states: as a rounded body decreases in size, it exposes more sur face relative to its weight. Primitive plants, such as the molds, yeasts and fungi, liberate large numbers of tiny spores that drift in the slightest of breezes. These minute "seeds" are so small that they can remain suspended indefinitely, and they are always in the air around us.

Moving water —be it a flowing

Photographs by Jon Farrar

stream, runoff after a rain or wind blown waves sweeping a lake's surface—is a good agency for the transport of seeds, plant parts and occasionally entire plants. Much of this plant movement by water is accidental and occurs only as a result of dramatic water movement such as floods. In these cases, transported plants have no special adaptations to enhance their migration.

Other plants, especially true water plants such as the water lily and the pondweeds, have forms that definitely favor their movement by water. Duck weed is typical of these plants, having thin, floating leaves and dangling roots that drift wherever wind and water currents carry them. High waters may wash them into isolated oxbows or sloughs where they quickly colonize and proliferate.

A third force of nature that operates in plant migration is gravity. This seems rather obvious, but many plants have no other apparent adaptations to disperse their seeds. Their fruit merely ripens and drops to the ground. Gravity can also move rounded seeds by rolling them down slopes until they are lodged in place. These generalized plants seem ill-prepared to compete with more specialized types, but they have attained large geographical ranges nonetheless. In a sense, they are the opossums of the plant king dom; unspecialized and slovenly, yet successful competitors for the necessities of life.

Although not a force of nature, animal carriers are one of the most efficient transporters of seeds. At one time or another, most species of animals help move seeds from one place to another. Plants have insured their portage via animals by evolving specialized structures that cling to fur and feathers, or edible fruits that encourage ingestion. A significant amount of seed hitchhiking also occurs incidentally. Charles Darwin, noted zoologist of the 19th century, found more than 500 seeds in the bits of muck adhering to the feet of wild ducks, thus assuring their transport to other marshes.

A significant number of plants, collectively called the stick-tights, have evolved seeds with hooked hairs or spines that attach themselves to near ly anything that brushes against them. Meadow voles, raccoons and even the pant cuffs of autumn hunters, are agents for their dispersal. Eventually the seeds are torn away or dropped in a ball of fur, many on a favorable enough site to start a new plant.

The hooks and spines of the stick tights come in a variety of forms. The rapier-like spines of the prickly pear cactus, in addition to providing protection for its palatable tissue, imbed readily in the hide of a wallowing bison or the foot pad of a passing coyote, and insure its transplant. The sandbur travels in similar fashion. Cockleburs and buffaloburs, viewed microscopically, exhibit hooks on the ends of each spine that insures their sticking fast when brushed by a pass ing animal. The long strings of tick clover, that plague riverbottom hunters each fall, are veritable mats of clinging, microscopic hooks.

Stick-tight seeds seem to be best adapted to grasping the hair of mammals, but rarely succeed in attaching to the slick surface of a birds feathers. Bird-carried seeds are more commonly coated with an adhesive muci lage that sticks to feathers. These slimy coated seeds are most prevalent among the water plants.

Perhaps the most ingenious means to effect seed dispersal is by "sugar coating" them in fleshy fruit. Few of us would be so naive as to suggest that the world's vast array of sweet, fleshy fruits were put on this earth for the pleasure of man and his little animal friends. If that had been the case, we could have done well without those annoying seeds found within the watermelon, apple or choke cherry. The sweetmeat of wild fruits can be nothing other than bribery; offered by plants so that animals will carry their seeds to new locations. The bright colors that advertise fruits add further support to this line of reasoning—in effect, plants are saying: "come, eat my fruit and spread my seeds."

All plant fruits are of a basic design — seed or seeds covered with a hard, indigestible covering, surrounded by a nourishing, appetizing pulp and a bright covering. Such fruits make up a regular part of many a wild animal's diet. The seeds succeed in passing through digestive tracts unscathed and in some cases are even stimulated to germinate by the action of gastric acids. Ultimately they are deposited at a new site in a natural ball of fertilizer. To assure that fruits are not picked until the seeds are mature and viable, most fruits characteristically have sour or astringent pulps until ripe.

Other plant fruits, especially the nuts, would at first appear to be adversely affected by the foraging of hungry animals. Generally, though, these plants produce an abundance of mast, more than the local rodent population can consume. Some of the nuts squirreled away in the soil are never recovered and sprout new trees the following growing season. Even though most nuts are consumed, the percentage that sprout into new plants is high because they have actually been carefully planted by hoarding rodents.

Self-pnopulsion of seeds, though less effective than other means of dispersal, is an interesting technique found in some species. The propelling machinery comes in various forms, but most utilize pressure created by differential drying of the seed pods. Members of the bean family are typical of this technique. The seeds of these legumes are produced in a pod divided lengthwise into halves. As the pod dries, each half tries to twist but meets resistance from the other half. As more and more moisture is lost, considerable tension is created. Finally, the bond ruptures and the exploding pod shoots out seeds in all directions.

The aptly named squirting cucumber, found along many Nebraska streams, provides another example of self-propelled seeds. The fruit of this vining plant ripens so turgidly within its spiny skin thatthe seeds are actually shot from the pod when it breaks away from the vine. Other plants, like primroses and bergamots, have fruiting structures that take advantage of other forces to toss their seeds about. The seeds of these plants lie loosely in open-topped capsules. When the plant's stalk is bent by passing animals or gusting winds and snaps back, seeds are thrown out several feet. Typically, seeds of "propelling plants" are smooth, rounded and hard —efficient shapes for any projectile.

One biologist, noting the modes of travel that plants have adapted, commented on their similarity to the ways that man has found to move from place to place:

"Man cannot swim far, but he can provide suitable appliances to make the winds carry him over the broad ocean; he cannot fly at all, but he can place suitable appliances in front of certain explosive forces and make these drive him triumphantly through the air. The difference between the Dandelion plume and the ship's sail, or between the explosive capsules of Witch Hazel and the aeroplane engine, is merely one of detail and degree. Man and plant are doing the same thing in essentially the same way, the chief difference being that man knows what he is doing while the plant does not."

A Quiet Greatness

HISTORY HAS MADE many a man immortal his deeds oftentimes larger in word than in in fact. The character and detail of both man and times may or may not be correctly represented, but the fact remains that here and there a man (or woman) has survived time.

Buffalo Bill, Wild Bill Hickok, Crazy Horse and Standing Bear are some of the epic heroes associated with Nebraska. But, the state has had many others. Their press agents may not have been as effective, but their memories are just as clear to friends and acquaintances, and to respective children of friends and acquaintances, as those of the so-called Greats. Perhaps theirs was a more quiet greatness.

George McAnulty of the Loup Valley was such a man; his deeds part of the history-making events that went into building a "civilization'' in central Nebraska. He was part of the history of Fort Hartsuff and the Loup Valley.

He was an eastern "dude", orphaned at 16 years of age and transplanted in the West where he became a trail rider, then an Indian fighter, then a pioneer set tler, always being an example of fairness and honesty. And, he left a lasting impression on those around him. That impression, and his own words in describing the Battle of Pebble Creek, provide an insight into the man, the events he participated in, and the way people thought about each other in those days.

McAnulty fought Indians with General Crook at the Rosebud, participated in the Battle of Pebble Creek that helped prompt the founding of Fort Hart suff, and the Battle of the Blow-Out, where three soldiers won Medals of Honor. His own discussion of Pebble Creek fills in a few details of what it was like to be an Indian fighter:

"On the evening of Jan. 18, 1874, a cold, stormy Sunday afternoon with the wind driving the snow in blinding sheets over the wild, unbroken prairie, in a lull in the storm, some hunters...beheld a large party of Indians surrounding the residence of Richard McClimans, near Willow Springs...."

The Indians looted several homesteads that night, and settlers held a meeting at a trapper's shanty to decide what to do.

"No one slept in the frontier settlement that night," McAnulty continued, "for it was known that in the morning the Indians would be asked to return all the stolen goods and pay for the property taken and destroyed, and if they refused, then, large as the party was —about 40 in number—it would mean a fight, even though we could muster only 16 men.

"The next morning, Jan. 19, 1874, was the cold est morning of the year, but in spite of this, bright and early we were on the way to Pebble Creek under the command of Charley White (Buckskin Charley). Charley, who knew a little Sioux jargon, talked with the chief who emerged from the tepee, took a cartridge from his belt, held it above his head, summoned his followers, and standing in their midst in the gray light of the morning uttered the Sioux war chief's battle cry, always terrible in character.

"White rejoined his little command and ordered us to seek shelter under the bank of the Loup River. The Indians opened fire as we reached the bank. It was promptly returned, and for 10 minutes the roar of musketry was like that in other days experienced at Rosebud Creek.

"It was soon discovered that owing to the extreme cold the shells were sticking in our guns, retarding our fire; and right here I must mention what I believe was the coolest act I ever saw a man do in time of extreme danger. Steve Chase, a little in advance of the rest of us, finding the cartridge stuck in his gun, sat down and coolly opening his pocket knife, proceeded to pick the shell out while the bullets flew so thickly around him that to this day it is a mystery to what strange providence he owed his escape....

"Marion Littlefield arose to fire. He exposed his head to the enemy and just as he pressed the trigger of his needle gun there was an answering report and he fell dead on the bank of the river. The shot that killed him was almost the last of the fight. The Indians withdrew....With heavy hearts we raised our dead comrade and carried him farther down the river to a place of safety. Here we kindled a fire to warm our guns, expecting every moment to be again at tacked...."

The attack never materialized, but McAnulty became active in seeking protection from Washington for the Valley. It eventually came in the form of Fort Hartsuff, which he helped build, then volunteered to serve in as a soldier.

McAnulty's strength of character left a lasting impression on his friend Thurman A. Smith who wrote of him: "Carousals of cowboys and border outlaws, gun-slinging when men shot to kill, night life at its worst in the raw towns-all this was of passing interest to the clean-minded youth who had promised his dying mother to beware of the evils of strong drink and bad women'. He kept his promise inviolate through all those years when drunkenness and dissipation were unbridled on the frontier".

Smith saw his friend as a dreamer, too. "In his vision were rich fields of growing crops, a snug log cabin, leaping flames in the fireplace against another winter's cold...He married Lillian Moore of Scotia and became a tiller of Nebraska's rich soil a decade after his vision of the log-cabin hearthstone where later four children gathered to pop corn and pull taffy...."

Biographer H. W. Foght in Tra/7 Of The Loup also expressed the dreams: "Mr. McAnulty is a believer in the North Loup Valley. Never, even during the darkest years, has his faith in it faltered...."

McAnulty was a family man, Smith said. "For 54 years George and Lillian McAnulty were wedded sweethearts, then death parted them."

"Six years later he joined his wife in another New Country, fairer far than their beloved valley." Smith also saw him as an inspiration to others, and expressed that inspiration in the following poem, part of his obituary for his friend:

"Comes the long rest —a narrow bed within The North Loup Valley's clean embrace, Where night falls softly as silken curtains From the starlit sky. Winds gently pluck Harpstrings of prairie bunch-grass; Sighing, sobbing, singing a requiem. Against the silver hills the yucca's pale Waxen tapers glow like blest funeral candles; Their perfume like sweet incense interceded. The soul, triumphant over death, Wings its joyful way to Heaven and God And those he 'loved and lost awhile.' And, we who weep and mourn his going On before, resolve to pledge to carry on His work, unfinished, but so well begun."According to Smith: "George W. McAnulty departed from this planet on January 25, 1940. In his passing this Valley lost its richest source of authentic pioneer tradition and history; the Pioneer Settlers lost the president who had given many years of faithful service; and the Historical Society, one of its oldest and most active members. Beyond all, we are bereft of a high-minded, well-loved and able fellow citizen who has been active in the affairs of our valley for nearly three-quarters of a century."

Today, during the centennial of Fort Hartsuff's establishment, Loup Valley residents discuss the 100 year-old events of Loup Valley history. And, George McAnulty's name still comes up.

STATEMENT OF OWNERSHIP, MANAGEMENT AND CIRCULATION

(Act of August 1 2, 1970: Section 3685, Title 39, United States Code).1. Title of publication: NEBRASKAland

2. Date of filing: October 1, 1974

3. Frequency of issue: Monthly

4. Location of known office of publication: 2200 N. 33rd Street, Lincoln, Lancaster Co., Nebraska, 68503

5. Location of the headquarters or general business offices of the publishers (not printers): Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, 2200 N. 33rd Street, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503.

6. Names and addresses of publisher and editor: Publisher: Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, 2200 N. 33rd Street, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Editor: Lowell Johnson, 1945 S. 26th, Lincoln, Nebraska 68502.

7. Owner: Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, 2200 N. 33rd Street, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503

8. Known bondholders, mortgagees, and other security holders owning or holding one percent or more of total amount of bonds, mortgages or other securities: None

9. The purpose, function, and nonprofit status of this organization and the exempt status for federal income tax purposes have not changed during pre ceding 12 months

10. Extent and nature of circulation: A. Total no. copies printed: Average no. copies each issue during preceding 12 months, 61,181; single issue nearest to filing date, 55,000. B. Paid circulation: 1. Sales through dealers and carriers, street vendors and counter sales: Average no. copies each issue during preceding 12 months, 2,550; single issue nearest to filing date, 50. 2. Mail subscriptions: Average no. copies each issue during preceding 12 months, 52,654, single issue nearest to filing date, 52,218. C. Total paid circulation: Average no. copies each issue during preceding 12 months, 55,204; single issue nearest to filing date, 52,268. D. Free distribution by mail, carrier or other means: 1. Samples, complimentary, and other free copies: Average no. copies each issue during preceding 12 months, 728; single issue nearest filing date, 1,732. 2. Copies distributed to news agents, but not sold: Average no. copies each issue during preceding 12 months, 5,007; single issue nearest filing date, none. E. Total distribution (Sum of C and D): Average no. copies each issue during preceding 12 months, 60,939; single issue nearest filing date, 54,000. F. Office use, left-over, unaccounted, spoiled after printing: Average no. copies each issue during preceding 12 months, 242; single issue nearest filing date, 1,000. G. Total (Sum of E & F — should equal net press run shown in A): Average no. copies each issue during preceding 12 months, 61,181; single issue nearest filing date, 55,000.

I certify that the statements made by me above are correct and complete.

(Signed) Lowell JohnsonTHE LAST WEEKEND

(Continued from page 8)stubble, showed that at least quail were using the plot. Periodic thickets and snow mounded woodpiles urged us onward, and finally the bobwhites jumped.

Danny dumped one neatly, I missed twice, then Danny barely dropped another which was out just a little far for his 20-double to reach firmly. The bird ran into a log jam and disappeared, and several minutes of dropping into snow-filled crevices produced nothing. The remainder of the fenceline also came up empty, so we still hadn't seen a rooster.

From that point on we should have been bunny hunting, but for some reason we passed them all up. Almost under every bush and in every ditch, bunnies sat quietly watching us pass, and not one dashed out to snap at our tires.

Several miles passed thus, with lots of bunnies, several detours due to deep snow, and only distant patches of cover offering much in the way of ring neck prospects. Either they were too distant or the landowner was not known, so it was not until we saw three pheasants sitting in trees in a draw below road level that our excitement became evident.

Our pleading to Orv to take us to the pheasants had finally paid off, but only barely. There was no opportunity to surround the thicket, so Danny slipped and slid down into the area and downed the most tardy of the three roosters as it tried to negotiate its way through the branches. Despite the fact that it was again Danny who scored, we felt our luck was changing and we had found the right combination — all we had to do was look into the trees.

It was a small canyon that produced the next pheasant, though, with no trees around. And, it was because we saw the pheasant, not because we nosed him out, that he came to hand. To help even things out, Danny hung around the background, thus allowing Orv to work around in range and clobber the cock when he finally decided to get his wingpits exposed to the cold temperature. And, he got air borne only because he didn't have any where to run.

When again underway, we discussed the lamentable fact that each year it is tougher to find time to get in much hunt ing. This is a subject that most hunters cover at some time during an outing, and there always seem to be more projects each year for each to do that take priority. We wondered if pheasant populations had much to do with it, as the "down" years must influence one's enthusiasm.

As several hours passed on both sides of lunch without our seeing another pheasant, despite several long, chilling walks, we wondered if the pheasants had migrated south. Then, along about sun down we found where a great number of them were. And, it was another public hunting area that answered the dilemma.

About a half-mile away was a weedy field, across from an abandoned farm with a healthy windbreak beside it, and above it we saw thousands of crows lazily cruising.

"Now, if we were crow hunting, we would have found a bonanza," someone offered. And, while our attention focused on the rafts of crows, we saw a couple dozen pheasants fly into the very field be low them. The pheasants were coming from behind the trees in the windbreak, or out of it, and they just kept coming. They glided across the road and plunked into the weeds, apparently planning to settle in for the night.

Orval stopped the car about halfway to the trees and we fidgeted with our shot guns, watching as perhaps 100 or 150 pheasants made the passage.

"We'll never be able to get close to

them, but let's walk among them anyway," I suggested, still being pheasantless in the shooting department. The CAP land was nice and level except for a hill on the far side of the field, perhaps 200 yards away.

As we separated a distance to cover as much ground as possible, Danny continued telling about a friend of his who grew up on a farm with a similar situation. Each afternoon, he said, his friend would slip out into the weed patch and wait for the pheasants to return to their beds. He had only a single-shot shotgun, but he made the one shell count as he always met one of the first arrivals on its glidepath into the weeds. We theorized whether ringneck decoys would work in a case like that, but they probably wouldn't be needed.

Due to our clumsy walking, the birds were taking off in big bunches just as they had arrived, and well out of range. Although difficult to estimate under such conditions, I know there were well over 125 birds rudely kicked out of the weeds, in an area of not over 25 or 30 acres. Only one of those settling in took to the air again too late, and I nailed him neatly where he could be easily found atop the snow in an open area near the base of the hill.

Removing ourselves quickly from the field in case the birds wanted to return, we congratulated ourselves upon getting one bird apiece for the day, but feeling best about seeing that multitude of pheasants in the closing half-hour.

Although Orval couldn't hunt the next morning, I told him I would bring along my nine-year-old son, Kurt, and the team would not miss him. And, Danny was going to bring a .22 rifle because of the number of bunnies encountered during the day.

Actually, things went well the next morning, although we spent at least as much time rounding up cottontails as we did pheasants. Hitting some of the same spots as on the previous day, we saw at least as many bunnies, and brought seven of them home. Another three ringnecks also came to hand during three separate sessions. Kurt was first to score, downing his very first bird as we moved in on a ringneck peering at us from behind weeds atop an irrigation ditch.

After a shot rang out and the bird dropped, Kurt asked each of us if we had shot. Neither of us had, so it was a surprise to all three of us that he dropped the rooster on a fairly long shot with his .410. He was tough to live with the rest of the day, and he later put a ring into one foot and wore it on his belt like some scalp hunter.

My bird was less spectacular, as I saw a lone bird in a bushy draw and merely slipped in to investigate. Within a few feet, about two dozen pheasants flushed in all directions, and I was very lucky to knock one down from among the branches.

44The weather was much more pleasant that morning, and walking out small plots was easier to take. And, each time we saw one bird, there would be several, but they seemed a little more skittish than they should have been, and usually exited quite a distance away, before we were ready or within range.

During one of the lulls between fields, Danny for some reason brought up the subject of fish, which didn't seem to have much bearing on our pursuits, but it turned out to be highly enlightening.