NEBRASKAland

November 1974

for the Record

Farewell to a Great Nebraska

Mel Steen was Nebraska's greatest public figure since George Norris.

No governor or congressman or senator, with the possible exception of Norris, has ever accomplished so much or had such far-reaching impact on the state.

Melvin O. Steen was only the director of the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. He held that job only 14 years, and almost half of those years he was past the age when most men retire. But what years they were!

And what benefits accrue to us today because Mel Steen was here.

The interstate lakes were his idea —an idea greeted with skepticism, apathy and opposition from various sources as were most of his ideas. Yet somehow Mel could whittle away at the opposition until it became support, and somehow the things he saw to do managed to get done.

Significantly, when he left office, the development of additional lakes in the chain came to a stop.

The Wild West Arena at North Platte was pushed through in the last year of Steen's Game Commission career. If it had been postponed a year, it never would have been built. And there would be no Wild West Show.

There would be no Nebraskaland Days, either, except for Steen; no Fort Kearny; no Fort Robinson park development; no Buffalo Bill Historical Park; no wild turkey season; no antelope hunting revival; no Two Rivers Recreation Area; no Salt Valley lakes system; no Indian Cave Park....

Mel Steen, a newcomer to the state when he took over the Game and Parks department, saw recreation and tourism potential in Nebraska that Nebraskans couldn't see.

And much of what he envisioned became reality to our enduring benefit.

Mel Steen died Monday at 77', his work finished. It was a great work. Nebraskans owe him a fitting memorial, as well as a continuing respect for the "Good Life" he taught us to appreciate and to claim with pride.

This editorial appeared in the North Platte Telegraph-Bulletin and is reprinted here with permission.

Resolution

BE IT RESOLVED by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, duly convened in the City of Lincoln, Nebraska, this 16th day of August, 1974:

THAT we individually and collectively mourn the passing of a truly dedicated conservationist and honorable man in Melvin O. Steen;

THAT during his tenure as director of the Game and Parks Commission, outstanding strides were made in all phases of the Commission s responsibilities;

THAT this uncommon man attained uncommon achievements during his 14 years at the helm of this Commission and his nearly 50 years in the conservation field;

THAT Nebraskans will long remember and benefit from his far sighted accomplishments in wildlife management and outdoor recreation;

THAT his unswerving dedication to the principles of conservation represented a life-long personal commitment to wildlife and the outdoors;

THAT his determined efforts enhanced and will continue to enhance the quality of life for all people and particularly the State of Nebraska for generations to come.

THEREFORE, we order that this resolution be spread on the minutes of this Commission and that a copy thereof be forwarded to the Steen family as an expression of our deepest sympathy, but also our sincere appreciation that he came our way.

In memory of M.O. Steen, his work and all he stood for, the November issue of NEBRASKAland Magazine is dedicated. He will not be forgotten.

Bobwhite by the Acre

IT ISN'T OFTEN that you shoot a bobwhite and catch it on the way down, but that was the way it went the day we hunted quail in a strong wind. Trying to keep a covey from breaking with the wind, we had pushed up a hedgerow into the wind, but when the birds flushed, they broke up and over our heads and streaked away like miniature jets.

Jim Slominski was on the far side of the hedgerow laughing and hollering over how he had caught the quail he shot when it fell. I just stood and lamented the fact that I was out of shells —and I had brought a full box.

Jim, Dan Wright, Paul McLlnay, all of Falls City, and I had started hunting early that December, 1973 afternoon, and the sun was settling behind the horizon when we finally limited out. In between, we saw more quail than I thought a section of land was capable of supporting. We also shot more shells than I thought four people could carry.

I had met Jim once before on a fishing trip and thought he complemented the rest of us well; he incessantly chattering about something or other, Paul saying little if anything, Dan more vociferous than Paul, and me —I could keep up the talk to fill the remaining slot. Between us we managed to keep up a steady conversation, without the usual lulls and dead spots like those when four quiet people converse, yet without the competitive jabber of four talkers.

Dan and I had hunted the section in Nemaha County when we were kids, but it was many years since I had been back in Nebraska's prime quail country. We reminisced about the nights we spent in the now abandoned house trying to keep warm with only a cook stove to heat the place.

Weeds had taken over the yard and the buildings were in dire need of repair, but the rest of the farm looked the same. Corn, milo, soybeans, weeds, natural grasses, hedgerows, timber, thickets, brush piles, two creeks and every other conceivable type of quail habitat covers the land. We hadn't walked more than a few yards beyond the yard when a cry went up: "Quail ahead."

The dogs, fresh and full of run, were working too far out and were pushing the birds up ahead of us. Finally, after some frantic yelling and considerable cussing, the dogs stayed in closer and we could see the bobs running through the snow in the hedge.

"Look at this —here I am with two shots, birds everywhere, and Tim's playing in the snow," Jim laughed.

Working my way toward the birds, I had broken through the snow crust and sunken in up to my waist just as the birds broke cover. From my lowly position, I managed to throw out three rapid shots but didn't pull a feather.

We continued to work the hedge, pushing toward a creek at the far end. At the end of the hedge, pine trees, heavy weeds and milo offered the birds several escape routes. We figured we would have to jump another covey if we were to get more shooting. We weren't disappointed.

After reaching the creek, Jim and I were trying to find a way down the bank when another covey broke from under some pine trees. Jim fired twice at the fleeting targets and I (Continued on page 46)

Strong winds and spent shells mark southeast quail hunt, giving us a full day of exercise and fun as reward

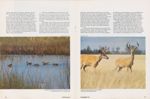

Ducks had been scarce, as mallards stayed north in mild weather. But, a twilight vantage point in a deer blind told me they had come. Next morning, I gladly traded bow for scattergun

THE DAY THE DUCKS CAME IN

THE DUCK SEASON was several weeks old, and all the hunters had been asking the same question: "Where are all the birds this year? Like everyone else, Jerry Erickson and I had discussed the tardy migration when we had planned our hunt a few days earlier.

But, we finally decided that you don't really need ducks to go duck hunting. Frosty-fresh air, a quiet stretch of woods and water all to your self, some good hunting partners with fresh yarns to swap, and all the other intangible rewards of duck hunting seem reason enough to go.

Until the eve of the hunt, I had no more idea of the whereabouts of the big mallards than the next guy. But that Saturday night, I set the alarm for a sleepy 5:30 a.m. wakeup with unaccustomed confidence, because this time I knew where the ducks were.

I had seen them that evening as I lowered my bow and quiver of arrows from a deer blind by the last dim light of day. Great black clouds of newly arrived mallards boiled over the Platte River a mile or so behind me, and a chilly breeze brought me samples of their scolding and chattering as they competed for airspace in the holding pattern over the river.

The geese had come, too. Several bunches of the big birds were circling the river, and others were making scouting trips over the countryside before settling in for the night. In fact, I might not have glanced toward the river at all that evening if one of those reconaissance flights hadn't passed low overhead, rudely jarring my at tention from the silent, earthbound world of shadows and deer sign, with the whistling of their wings and raucous honking.

Jerry and I both called Wahoo our home, but a considerable gap in years had kept us from knowing each other very well until a couple of years before. His son, Edd, and I shared a couple of apartments until he had deserted me the preceding February to commit matrimony. During those years, I had been invited out to "The Puddle", a tract of timber Jerry and some partners had along the Platte River, with a sandpit lake and summer cabins.

I had caught bass and crappie in the pit, explored the woods and gone for spins on the Platte in the airboat they kept there. Now, I was invited to use the duck blinds on the lake. The stars shone clearly that morning in an otherwise black sky. The cold snap that had pushed the birds to us was just bearable, but the chilly north wind that accentuated it must have sent less confident hunters back to their electric blankets. However, knowing the birds had come seemed to blunt the barbs of the breeze.

A couple of setbacks loomed early, but I hoped that they wouldn't set a pattern for the day. First of all, I was forced to go into the chilly world of the waterfowler without the bacon and eggs and hotcakes that I had planned on. At that early hour, my sleepy mind simply couldn't comprehend the complex rules set by the local beanery which, I believe, had something to do with the phase of the moon multiplied by the square root of the Dow Jones average the preceding Tuesday. At any rate, these regulations boiled down to the fact that I had to wait for a vacancy at a crowded counter, while behind me stood a row of empty booths and an almost empty row of tables. The tables' only occupants were three waitresses, drinking coffee, smoking cigarettes and loudly reciting the lit any of rules that allowed them to do that while their customers had to claw for a space at the counter. I chose, instead, to grab a big bag of dough nuts and a jug of coffee.

The second bit of bad news was that our other hunting partner for the day couldn't make it because of a fire at his business the night before.

We arrived at The Puddle with first light. Our party included Dixie, Jerry's 8-year-old springer spaniel. She wasn't exactly your classic waterfowler's dog, but she took her place in the blind as if she knew what she was doing.

The lake was rectangular, about 70 by 100 yards, and rimmed on three sides by a thick stand of cedars. In its northwest corner floated some 50 decoys within good scattergun range of a half-dozen new one-man pits and a four-man blind.

With a pink tint on the horizon to our left promising sunrise, we sat down to await shooting time and the first ducks. The wind had died for a bit, and the tiniest sound rang on the cold air like the hammer on a smithy's anvil. A cow bellered somewhere across the river, and a church bell in the distance announced the approach of first service.

When our watches told us we were 15 minutes from legal shooting time, Jerry dug out his trusty old duck call. "I'll just give 'em a couple of toots to kind of wake 'em up", he said. "Be sides, ! could use the practice. I'm not even sure this old thing still works."

That first brassy highball shattered the silence like a bomb, and the cedars around the lake hurled the echo back into our faces before Jerry took the call from his lips. But it jarred us from our pre-dawn dream world into the practical realm of duck hunting. I pulled my old duck horn from under several layers of clothing and tried a couple of squawks myself, stuffed some No. 4s into my old 12 gauge and settled back to wait.

It didn't take long. In fact, it didn't take long enough to suit us. With perhaps 10 minutes to go before legal shooting time, a bunch of about 2 dozen mallards came winging over the Platte River Refuge, spotted our decoys, and began to circle.

They acted as if they were really interested in our little lake, making a wide turn that must have taken them over the river some 400 yards behind us. They made a swing to the east, gave up some altitude as they passed south of us, and headed toward our setup.

"Let's just dummy up. Maybe they'll land and stick around until we can shoot," I suggested. But almost as I spoke, the plan blew up in our faces.

Almost in unison, those mallards put on the brakes, swapped ends and high-tailed it out of there. At first we thought they might have picked up a movement in the blind or been spooked by something we couldn't see, like a deer or coon nearby. But, when a second flock turned in a replay of that incident just after shooting time, we knew something was terribly wrong.

We were sure that the blind was

10 NEBRASKAland NOVEMBER 1974 11 Photographs by Bob Crier

Photographs by Bob Crier

well camouflaged, and we had been careful to make no extraneous noise or movements. It was only after considerable squinting and neck stretch ing that we spotted the trouble.

The decoys had picked up just the slightest bit of frost, which we could barely see from the blind. But, when we looked at them from the west, with the low sun behind them, they glistened like mirrors. No self-respecting mallard would sit around looking like that, and those birds knew it. The glare from that little bit of frost immediately told both bunches of birds that the creatures below them were phonies.

I happened to have my waders along, so I was elected to remedy the situation. During the process, I was quickly reminded of the little pinhole I had administered to the left boot during my last fishing trip. A cold, soaked sock goaded me into high gear as I gingerly dunked each decoy, trying to keep my fingers out of the icy water, at the same time fighting to keep my balance and watching the water level and the top lip of my waders converge.

I was so engossed in my work that I didn't hear Jerry's hoarse whispered warning: "Ducks!"

I glanced up at Jerry, who was just standing in the blind staring at us all in bewilderment. His jaw hung so wide ajar that I could just about count the fillings in his lower molars. In a second or two, the mallards realized their error and took off, showering me with a cold spray. Their departure finally jolted my partner into action, and he threw up a couple of hasty and ineffective shots at them after I was out of the line of fire.

By that time we were both getting tired of all those ducks and all our blunders. We settled down for some serious duck hunting, encouraged by the number of birds and their apparent lack of sophistication. That part of the country was full of mallards, and most of them were not at all shy of decoys like they would be after a few days of hunting experience.

But we had blown the best of our opportunities by that time, as most of the birds had already left the river and were filling their bills in cornfields several miles away. We lured a couple of small bunches later in the morning, and Jerry managed to scratch a drake from one flock. A bit after that, a lone hen materialized among our decoys and came tumbling down after a small volley from our scatterguns.

The little springer spaniel endured our sorry shooting and tactical boners with remarkable patience, but the whole thing finally got the best of her. During one of many lulls in the action, Dixie put aside all the canine rules of waterfowling etiquette and went hunting on her own. After a perfunctory check of our lake, she disappeared into the woods and headed toward another sandpit where she would have little effect on our efforts.

We gave little thought to the dog until we heard a scratch and a low whimper at the door of the blind a half-hour later. I scanned an empty sky while Jerry let her in.

At that moment, I became low man on the totem pole because now even the dog was ahead of me in hunting success. She proudly carried a crippled hen gadwall that she had some how captured on her wanderings.

Duck hunters seldom pass up such a golden opportunity to goad their cronies —it's as much a part of the sport as decoys and shotguns. And, it didn't take Jerry long to formulate his attack, which he thereupon executed masterfully.

"You know, I wouldn't feel too bad about this, Ken. Lots of guys have been skunked while all the others in the blind scored. I s'pose there've even been guys who had their black Lab or Chesapeake bring in a duck when they didn't get a bird. Of course, Dixie's just a spaniel, not exactly a duck dog—"

I drowned Jerry's ribbing in a chorus from my duck call. It didn't bring in any birds, but it got his mind off my embarassing situation and back to the business at hand.

About 12:30, we decided that a bit of chow was long overdue. My run in with the waitresses that morning not only cost me my breakfast, but also lunch. I had planned on ordering a couple of sandwiches to take along, but nev^r got the chance, so I was forced to choke down my umpteenth doughnut as an excuse for lunch.

"I probably should call it a day," Jerry said after soaking up some warmth from the afternoon sun. "If we assume that I shot that hen, that's 70 points, and that drake makes 90. I suppose I should claim that gadwall Dixie brought in, since she's my dog. That puts me at my limit. Besides, I'm expecting some company later today, and I should be home when they arrive. Why don't you stick around and see if you can somehow get a duck?"

I decided to do just that, and switched to one of the pits on the west shore. Just before he left, Jerry offered a bit of advice and encourage ment:

"Watch out for the 1:30 flight," he said. "I know it sounds like a lot of hooey, but we've noticed over the years that the birds seem to follow some kind of schedule. We almost always get some good shooting in the afternoon, and it's almost always right around 1:30 and then again about 3:30."

With a mixture of mild hope and strong skepticism, I settled back to continue the vigil. I had more than five hours of duck hunting under my belt by then, and I had enjoyed every minute of it. But, I would have felt even better with something in the game bag besides an empty coffee jug, and something in my stomach besides those lumpy doughnuts.

It wasn't more than a few minutes past the magic 1:30 mark when sure enough, a batch of ducks showed up. About 15 mallards worked their way up the river perhaps 400 yards to my left. I let them get downwind before I called, but the first notes got the at tention of three or four birds in the flock. They turned for a look at the setup, and the others followed them in like they were on a leash.

When I popped up to shoot, the birds were so close that they startled me. My first shell did nothing but blow a big hole in the air about two feet below a rapidly departing drake. But my second load dumped him neatly on the outside edge of the decoys, and the third shot knocked another greenhead over just at the edge of the timber to my left.

I didn't really need to go after the dead bird in the water, because he would soon float out of sight in the weeds along shore. But the one that came down near the timber merited attention. The duck had been well centered in the pattern, but it fell as if it might still be able to hide, and I wanted to get to the spot before I lost him.

Any duck hunter will tell you that the best way to get birds to come in is to leave your shotgun in the blind and go wandering around. True to form, another two dozen mallards touched down momentarily just as I picked up that duck.

I hustled back to the blind, much more confident now in Jerry's flight schedules. Another flock came along a few minutes later, but they touched down a bit out of range and left an instant later. That didn't bother me, though, because I was sure that I would get another go at the green heads a little later.

By 3:20, I was again in business. A big bunch of perhaps 30 or 40 mallards was circling, although they seemed suspicious and stayed just on the edge of pellet range. Finally a few crossed within range, and I collected another greenhead.

In 10 minutes, I was working on another bunch. But, my shooting eye failed me, and I got nothing but a lot of loud trigger-finger exercise. More ducks were around, though. A small bunch of about a half-dozen came along and tried to settle among the decoys, and I collected my fourth duck.

I only needed one more bird to fill my limit, but I decided to fold up operations. I had enough mallards to last me a while, and my shooting was getting a bit wild, so I elected to get out of there before I spooked every duck in the country.

Besides, I was getting hungry again, and I was out of doughnuts.

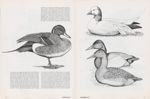

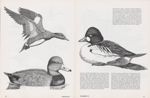

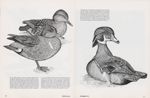

Waterfowl Portraits

SINCE HIS days as a boy on the North Dakota prairies, Paul A. Johnsgard has "measured his winters, not by conventional time units, but in the days it took for the snow geese to return from their wintering grounds" The author of five books: Song of the North Wind—A Story of the Snow Goose; Grouse and Quails of North America; Waterfowl —Their Biology and Natural History; Animal Behavior; and Handbook of Waterfowl Behavior, and of numerous articles in national magazines and over 40 tech nical papers, he is eminently qualified to capture in pen and ink the very essence of Nebraska's wildfowl. The line art on the following pages are but a few of the illustrations to be found in his forthcoming book, Waterfowl of North America.

Dr. Johnsgard received his Ph.D from Cornell University, Ithaca, N. Y., and a postdoctoral fellowship with Bristol University and the Wildfowl Trust, England. Currently he is Professor of Zoology in the School of Life Sciences at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, a position he has held since 1961. His teaching responsibilities in clude ecology, animal behavior and ornithology.

His life-long love for wildfowl is best described in his own words when speaking of his early years on the prairie-pothole country of North Dakota: "The annual spring ritual of meeting the geese on their return from the south was more important to me than the opening day of hunting season, the beginning of summer vacation or even the arrival of Christmas. The spring return of the geese represented my epiphany —a manifestation of gods I could see, hear, and nearly touch as they streamed into the marsh a few feet above the tips of the cattails and phragmites___During the drive home my ears would resound with the cries of the wild geese and, when I closed my eyes that night, I saw them still, their strong wings flashing in the sun light, their immaculate bodies projected against the azure sky."

Currently, Dr. Johnsgard has two books in preparation: American Gamebirds of Uplands and Shores, to be published in the fall of 1975 by the University of Nebraska Press, and a book on the ecology and behavior of the sandhill crane and trumpeter swan.

14 NEBRASKAland NOVEMBER 1974 15

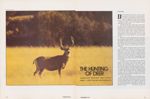

THE HUNTING OF DEER

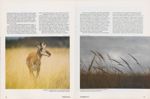

Hunters who 'Wink deer" lead "cushion riders" in both success and enjoyment

Photograph by Roger BoucDEER HUNTING know-how is not as easily acquired as it once was. In the old days, a young man absorbed just about every thing he needed to know from hanging around a few old timers who knew their business — listening to their yarns, and, perhaps hunting with them a time or two.

The deer hunter of a century ago usually knew all about trail watching, still hunting, tracking, shooting, field care and the like. He could probably tell the age of a track in hours, estimate the size of a buck by his antler "rubs", and accurately forecast its daily routine just by checking a few trails and glancing at the countryside. And, he could probably do all of that before he was old enough to vote.

But today, anyone depending on such on-the-job training would probably be nearer retirement age before he knew his way around deer country. In Nebraska, deer hunters have only about nine days afield each year, unless they hunt with bow and arrow. That's not much time to learn a whole lot.

And, people nowadays spend a lot less time in the outdoors, so chances of picking up some deer savvy in the off season are limited. Also, Nebraska is a bit short on deer hunting tradition. The state's deer herd was nearly wiped out by the settlers, and no deer hunting was allowed in Ne braska from 1907 until 1945. Consequently, there are few real gray-beards in the ranks of Nebraska's deer hunters.

Of course, it would be tough for any one Nebraska deer hunter to become an expert on the subject in the truest sense of the word, simply because the state offers quite a bit of variety. In the east, the gunner will be going after some awfully shifty whitetails. The deer might be holed up in rugged Missouri River bluffs or in dense timber of Platte Valley lowlands. Or, they might be found skulking around farmlands, using shelterbelts, wooded draws and creeks for bedding areas, travel lanes and escape routes.

In the west, mule deer are usually the quarry, and they are likely to be found in a bit more open country. Mule deer do not require the heavy cover that the whitetail seeks. He is perfectly content to use broken terrain and a few brushy "pockets" for his cover requirements, although the muley also thrives in some (Continued on page 43)

Wipiti Wilderness

IN WILDNESS is the preservation of the world said Thoreau more than a century ago. At last we are beginning to sense his wisdom. Wildness is the essential characteristic of wilderness. Now, the tensions of the technological world battle man's instinct, for wilderness and civilization are opposites. A brief reflection reveals that man benefits from a mixture of the two, for either pure wilderness or pure civilization by itself would be intolerable.

If man completes his conquest of the natural world, he will find himself the captive. Arrogance and presumption have led man to believe that he lives apart from nature —to forget that he is only another of its creations. Awe at the wonder of nature should cause man to respect it; his instinct for self preservation should move him to save it.

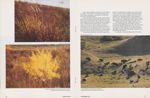

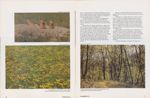

Today, reservoirs of wildness remain in some of the national parks and forests, and in a few state parks. Remnants representative of essentially all areas of North America have been set aside, with the exception of the tall and mid grass prairies. The Wapiti Wilderness Project was created to promote the restoration of such an area —an eastern Nebraska prairie. It is an attempt to reach back into time to grasp something of value before it slips away forever.

The vast prairie lay between the Appalachians and the Continental Divide. It extended from Canada to the fringes of the deserts of old Mexico. Its temperature ranged from bitter cold to intense heat, yet it supported a great variety of life.

The prairie was many things —grassland, woodland, marshland, and freshwater lakes and streams. Even within these areas, diversity was great. Some grasses, for example, were only a few inches high while others were as tall as an Indian on his horse. Such diversity 24 NEBRASKAland of habitat insured a diversity of animal life. More than 100 different animals and over 350 species of birds were found in Nebraska.

One of the most majestic of the plains animals is the American Elk, the wapiti. Wapiti were once common over much of the United States, and records describe the "magnificent herds" along the Niobrara and Elkhorn rivers in Nebraska as late as 1867. Some species became extinct shortly after the turn of the century, and the tule elk is at this time an endangered species. The Rocky Mountain Wapiti, which once roamed the prairies, survives now in mountain and refuge areas.

The prairie was also the home of the buffalo. These animals were so numerous that they formed herds that stretched from one horizon to the next. In the early 1800s their numbers were estimated to be more than 50 million, but by 1894 there were fewer than 40 animals in the entire United States. At the very last moment, conservationists secured legislation to save them from extinction.

The swiftest long-distance runner of the prairie is the pronghorn antelope. Pronghorns lived alongside the buffalo and Wapiti, feeding on succulent forbs.

The prairie dog was another important grazing animal of the prairie. He was small, but there were a lot of him. He prospered in spite of his many predators, but his social structure was so complex that an entire town might die if the population density dropped below a critical number.

Photograph by Lou Ell

Many other mammals were found on the Nebraska prairies. Among them were bighorn sheep, gray wolf, bobcat and beaver, porcupine, and mountain lion, black and grizzly bear.

More than half of the bird species in the United States may be found on the prairie. Besides the native birds, many of the eastern and western species have their distributional limits in the grasslands. In addition, many northern birds migrate through or spend the winter on the plains. Prairie chickens and sharp tailed grouse may still be found where the plow has not buried the sod. Magnificent birds of prey such as the prairie falcon, the red-tailed hawk and the golden eagle still ride the thermals in their search for food.

For diversity of plant life, go to the tropical rain

In the eastern prairies, timber stands of bur oak, ash, elm, Cottonwood, red oak, hickory and bass wood often extended fingers miles from the flood plains of the rivers into the rolling hills. In the west, pine and redcedar were common on the bluffs and buttes. Box elders, willows and cottonwoods were generally found along the streams.

In early fall, sumac provided some of the most

Photograph by Vincent Kershaw

brilliant reds found in all nature, while the oak and elm-covered hills presented the effect of a tapestry.

The prairies are an immensely important part of the history of our country. We have saved the areas of the Mountain Man and the Voyageurs, but where is there a reminder of the lands of the Plains Indians, the fur traders, and the land that the sod pioneers moved onto? One of the exciting ideas connected with the Wapiti Project is the planning of an authentic Indian village within its boundaries. It will be complete with buffalo-hide teepees, sweat lodges, and Indians living as they did before their conquest. The village would provide not only a place for campers to spend the night, but also a natural setting for the perpetuation of Plains Indian culture and philosophy.

With the re-establishment of the lush grass and tree cover, the area will increase its value as a source of oxygen for our atmosphere and pure water for many uses. It will become another excellent entry-way for precipitation into Nebraska's underground water supply, as well as a watershed giving runoff water with a low silt load.

The greatest appeal of the area will be simply that it is a big, open, clean outdoors like we've heard and read that it used to be. There will be hiking and camp ing in an area that just hasn't existed in our time. It will be a place of unsurpassed high adventure for outdoor people, and for the discovery of the joys of backpack camping. This experience leads you to the basic pleasures and satisfactions that come from simplification, resourcefulness and the use of your own two feet. Now you can go slow enough to see, to smell, to hear and to touch things. Imagine the thrill of waking some morning to look past clumps of trees and rolling grassland to see a herd of buffalo feeding. Would you secretly find it a pleasant task to have to protect your boots at night to keep a porcupine from chewing on them? Would you feel fortunate, some pink and violet dusk, to hear the singing of the coyotes? If yes, then camping in the Wapiti Wilderness is for you.

Fishing in the Wapiti Wilderness may offer some pleasant surprises. At the same time that Nebraska has continued to have better trout fishing than many realize, there are those of us who have seen the general decline of stream fishing in our own lifetime due to such problems as channel modification and the various kinds of water pollution. We have forgotten the fun of catching crappies and sunfish in running water. Prairie ponds and small lakes have also demonstrated their ability to produce the bigger game fish.

Imagine the rich opportunities in this area for photography, drawing and painting. Not many have had the opportunity of seeing the prairie grasslands in bloom, the dancing of the prairie chicken, or an Indian village at sunset. Many of the wilderness animals will be easily seen. Some others will take all the patience and skill of the scientist-naturalist to observe. In any case, this will be a place to study nature whether your interest is just awakening or you're a biologist

Photograph by Jon Farrar Photograph by Lou Ell Photograph by Harvey Gunderson

Photograph by Vincent Kershaw

Photograph by Harvey Gunderson

Photograph by Vincent Kershaw

with a research project. The great laboratory value of the area will be due not only to the reassembling of the prairie habitat, but also in the changes occurring during the transition back to wilderness.

Visitors during the early years will experience a special sense of change as wildness reclaims the area. It will be like a time-lapse movie of the all tpo familiar destruction of a natural area, only shown back wards!

Stimulation, fascination and beauty —spring, summer, fall and winter. Wilderness is our tie to the past. It is our place of origin. It affects us with a kind of home sickness that leads us to find reasons and excuses to take vacations back to the sea, the forests, the meadows and the mountains. We sit in front of fires and remember things we don't understand. We are soothed by the gently falling snow and are made absent minded by the sound of water running over stones. We can sense the change of seasons before they change and are invigorated by contact with the elements.

People cut off from their past run the risk of losing their sense of direction and of developing a cuitura loneliness.

Wilderness is another world. In it, time is not an hour or a day or a month, but sunrise and sunset, moon changes and seasons. There man can see him self in relation to the overall scheme, the strength of life and the purpose of death. The loss of any wilder ness, even though we might never have been able to be in it, makes us the poorer, just as the destruction of an art treasure in a museum which we would never be able to visit.

Spaciousness and isolation from civilization are inherent in the concept of wilderness. Wild animals require it if they are to find their own food and reproduce naturally. The project goal is a minimum of 64,000 acres. There are potential areas in northeastern Nebraska of sufficient size without railroads, towns or major highways which also have the needed natural features.

It will be necessary to remove all roads and

Photographs by Vincent Kershaw

buildings from the area, and to replace certain plants and animals which were once native. Trails will be established, and travel will be by hiking and snowshoe ing, and by gliding, as in crosscountry skiing. Unimproved campsites will develop, but in essence, the earth, plants and animals will be allowed to re-establish their natural relationships with only a limited in trusion from man.

As part of the wilderness preservation system, it will have the protection of federal law as a refuge for wild animals and prairie plants so that our children and the generations after will not be denied their right to see how it was. It will be a sanctuary for many of the endangered species of North America. It will provide a source of breeding stock for plants and animals which will be kept vigorous in the contests of survival.

A wilderness like this will become a reality only when enough of us want it to. A great number of people already desire such an area, but their feelings, their opinions, have not been brought together so that they can be effective. The organization of this existing desire and the stimulation of new interest is the first function of the Wapiti Wilderness Project. This interest must then be demonstrated to our legislators, and here we need the strength of numbers. The Wapiti Project can provide the organized support that our Congress men will need in order to obtain the necessary legislation so that the wilderness can be set aside and funded.

Photograph by Lou EllAnd now to be specific —what can you do?

First of all, we invite you to become a member.

We are an incorporated, non-profit, membership organization whose only purpose for existing is to work for the restoration of a prairie wilderness in the east ern half of Nebraska. Your influence can be magnified working within the framework of this group. Your dues and contributions are needed to continue the effective presentation of the Wapiti story —in our Own region and in Washington. Funds are needed to begin to buy the land; this could begin at any time. Your vote as a citizen is equally as important as your financial help, for without governmental assistance, it is not likely that the Wapiti Wilderness will ever be more than a dream. There are always opportunities to encourage others to become members.

Photograph by George GrubeBut YOU are the first essential! Take advantage of this moment. Give yourself the opportunity to be a part of this effort. Together we can be an effective force in the preservation of the quality of our lives.

An ambitious, commendable effort is being made by the Wapiti Wilderness Project to establish a tall-grass prairie wilderness area in eastern Nebraska before such a concept becomes totally impossible. The project is of such magnitude that it may become necessary for the National Park Service to complete it, but all groundwork must be done beforehand. Dr. Kershaw, an Omaha physician, and the many other dedicated persons involved, need public support, both vocal and monetary, to make a go of the venture. Few concepts could have such broad and lasting benefits to the people of Nebraska in the years to come. A special slide presentation is available for group show ings, through Dr. Kershaw at Wapiti Wilderness Project, 10914 Prairie Hills Dr., Omaha, Nebr. 68144, 402-393-5666. (Editor)

TIGER ON THE HILL

The late director of Game and Parks Commission, M.O. Steen was a dreamer and a doer, able to see problems and move to solve them

MEL STEEN is gone now —the dynamo has been put to rest. But, the fruits of his labor will long be with Nebraskans, and he won't be forgotten.

For 14 years Melvin O. Steen headed the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, and in that time he made many friends —people who knew he was doing the right thing —and many enemies, for few people who take firm stands on issues can avoid incurring someone's displeasure. And, in the field of conservation, Steen was a mover and a shaker—able to see what had to be done, figuring the best way to do it, then going ahead.

Some toe stepping had to be done in the process of carrying out some of his plans, but either people had to step aside or be stepped on. He didn't earn the title of "tiger on the hill" for nothing, as the short, chunky, white-haired man was a battler all the way.

One of the most flamboyant characters to grace the Nebraska scene, Steen was the first to admit that he could not have achieved his goals alone. He not only got the backing of the commissioners, but the aid of governors, state senators, other agency and department heads, and many influential people in Washington. He was a determined man who never learned to take "no" for an answer, and it was this bulldog tenacity which brought him success when others would have given up.

It was his belief that "Whether a project is popular or unpopular is beside the point. That is no criteria. There is nothing that cannot be changed if it is the right thing to do. It might take 25 years, but I'm not going to quit just because of rules, procedures or red tape."

Steen retired as director of the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission in 1970 after serving 14 years. Prior to that he had held conservation posts in North Dakota, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Missouri Conservation Commission, for a total of 50 years of public service.

It was his accomplishments in Nebraska, however, that caused the most furor and that have the most last ing value. During his tenure, which started in 1956, he added about 75,000 acres of public-use land to the ledger, in the form of 22 wayside areas, 5 historical parks and 22 recreation areas. He spent money to do this, including nearly $11 million in federal monies.

A list of other projects reads like a history book, al though some stand out as particularly beneficial. The

Such was his philosophy and so his efforts were directed —to get the most benefit for the least cost, and to do it despite opposition or apathy. Many areas at tracted Steen's attention and stirred his interest. What he saw was a tremendous potential, and the challenge to move Nebraska forward in all areas of the Commission's responsibility, whether it be parks, fisheries, game, land management, or the supervision of boating and tourism, which the legislature turned over to his leadership. In this latter area he also saw much potential, and did much to stir the state's sense of pride and get things moving. He knew the state's image must be changed, as he said: "Tourists avoid Nebraska. They feel there are no roads, no accommodations." It was then the idea for developments along Interstate 80 began to crystalize. "I realized that the great Platte Valley always had been and would continue to be the natural pathway for East-West travel." But, he felt, no one had told them about the state's magnificent western heritage.

So, people who once had laughed at his idea of creating the little oases along 1-80 found themselves pointing to them with pride, once they were created. And, so it went with many other of his projects. Stubborn opponents, either from listening to one of his discourses or seeing the results, became his supporters and staunch defenders in other battles.

Under his guidance, Nebraska pioneered in the field of pheasant management, innovating a program now being followed by many other states. He knew that the ringneck was a creature of heavy cover, which was gradually being eliminated. Thus, the Commission undertook two major steps: attempting to hold the line on the environment through the maintenance of permanent cover through programs such as the soil bank and Cropland Adjustment Program, and by providing trees and shrubs to farmers for conservation practices.

Steen was a motivating force behind both the soil bank and CAP, and he was the first wildlife man in the nation to espouse the soil bank. CAP came about as a result of another proposal he made to the American Association of Fish and Game Commissioners when he was chairman of the committee on land use.

Even those programs were too limited in scope, he felt. "Our ability to put cover on the land falls far short of any substantial accomplishment," he said at the time. "At the present time, CAP has enrolled 198,000 acres in Nebraska, which costs the federal government $4 million a year. To restore cover as it was in the late 1930s, we would have to retire between 5 million and 8 million acres, for that was the amount that lay idle at the peak of the pheasant's heyday.

"I get the feeling of a little barefoot boy with a wooden sword trying to stop a 40-ton tank, when I think how the cover is disappearing. We ate losing it eight 36 NEBRASKAland times faster than we could ever put it back," he ad mitted. He believed we must work through the farmers and make it economically feasible for them to preserve cover.

He also tried to develop better use of the resource by encouraging hunters to work harder, and by establishing a cocks-only season, but having it longer and with fewer regulations.

Many other programs worked, some with tremendous success. The stocking of Merriam's turkeys in the Pine Ridge was one of them. He, himself, termed it the most outstanding success he had ever seen in such a program. From 28 live-trapped, wild birds released in 1959, the turkey population literally boomed so that a hunting season could be held in 1962, with about 3,000 birds available to hunters.

Deer management also produced a tremendous population; through his efforts, the federal government began its wetlands acquisition program; Nebraska held its first special mallard drake season; the Commission undertook the trapping and transplanting of antelope, with 1,200 animals trapped in one winter.

"That was the largest single transplant of big game in this country in so short a time," Steen said at the time.

And in the fisheries area, the story was much the same. New species were introduced through his efforts, with the introduction of coho and kokanee salmon, the sacramento perch, the striped bass, the white perch, spotted bass and redear sunfish. But, the waters receiving these fish were in the west, and the people in the east, so Steen supported construction of new reservoirs like the Salt Valley lakes.

"I scraped the bottom of the money barrel until I got slivers under my fingernails to get development of the public-use facilities on these areas," Steen recalled later. At that time, $2 million had been so spent, and looking forward, he had added that: "We propose to do the same with the Papio watershed.

Looking back now, Steen's accomplishments seem as if they had always been a part of the overall scheme of things, yet few saw the potential except him. The development and expansion of Fort Robinson State Park, the chain of lakes and Salt Valley developments, acquisition and development of Ash Hollow State His torical Park, the Rock Creek Pony Express Station, Indian Cave State Park, Two Rivers and its fee trout fishing, developments at Lake McConaughy and the southwest reservoirs, Scouts Rest Ranch, now also a state historical park, development of Fort Atkinson, Fort Hartsuff, Ft. Kearny, acquisition of the Aerospace Museum, recreation of Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, and bringing into reality in Nebraska the Land and Water Conservation Fund, and a long list more.

But, perhaps when everything is considered, his major accomplishments were awakening a statewide interest in game and fish management and tourism, along with historical preservation, interpretation and restoration, and showing what could be done with some enthusiasm and know-how. He considered the decade of the 1960s as one of planning and preparation in all phases of Game and Parks Commission activity. "The real developments," he claimed, "will come in the 70s."

M.O. Steen was a dedicated and dynamic public servant with the ability to dream and make those dreams come true.

Prairie Life Animal Camouflage

MOST ANIMALS, to some degree, resemble their natural environment. Some are true masters of the art of camouflage. A walking stick hunts through the twigs of trees and bushes for smaller insects to feed upon. A snapping turtle is a fair facsimile of a moss-covered rock or log, and the mottled browns and buffs of a sharp tailed grouse are not unlike grass patterns.

The bush katydid on the grass stem (opposite page) is a good example of an animal that blends into its surroundings. Because the katydid spends much of its life foraging among grasses and forbs, it seems more than mere chance that it has a delicate green coloration closely matching its habitat. The katydid's wings wouldn't necessarily have to be shaped and veined like a leaf, and its slender, grass-like legs would be just as functional if they were short and stocky. But the natural world has provided for its own, and the katydid blends in well. When moved from its natural environment in the grass to an unnatural environment, like the bark of a cedar tree (also opposite page) the katydid stands out like a neon sign advertising a free meal to the first passing bird.

Animals blend with their surround ings by matching their habitat's color, pattern or form. Many species of animals rely on all three techniques. Biologists refer to this animal camouflage as cryptic concealment.

Cryptic coloration has grown out of the need of animals to be inconspicuous in their environment. It is nearly universal in the animal king dom. Only in the arctic are animals commonly white, while the predominant color of grassland animals is brown and creatures of the woods are usually green or brown. Even within a particular species of animal there are often color variations that match different environmental set tings. For example, deer mice that live in regions with clay soils have more reddish coats than those that live in regions with sandy or loamy soils.

Perhaps even more remarkable are those animals that change color to match the seasons. This phenomenon occurs in many animal groups, but it is most common with insects. Biologists have noted that the color of some insects varies markedly with the time of season they are hatched. Early broods may be green, but as summer progresses and the vegetation dries, subsequent hatchings are more yellow or brown. Individual grasshoppers show much the same pattern as they molt, turning from green to brown as the season progresses. One species of crab spider that preys on flower-frequenting insects has a fair range of coloration and can nearly match the season's predominant flower hue.

However, insects go far beyond matching their colors to those of their environment. It is extremely common among butterflies and moths to have disruptive patterns on their wings that conceal their true body contours from predators. In numerous instances, these patterns mimic the insect's background. For example, some tree roosting moths have color patterns on their wings that resemble patches of lichen on bark.

Other insects have ragged borders on their wings that simulate bark or leaf edges. The imitation of plant patterns is so advanced in some species that as the season progresses, succes sive hatches have more curved wings to better match the curled leaves of drying plants. Some insects are even reported to have hooks and bristles on their bodies that retain sand, soil or other materials native to their environment.

Reptiles, amphibians, birds and mammals have also evolved body colors and patterns to harmonize with their environments.

Some biologists have suggested that snakes can even be categorized according to their body patterns. Those that actively pursue prey, such as the blue racer, are generally of a uniform color or longitudinally striped to make them as inconspicuous as possible while moving. More sluggish snakes, as the pygmy rattlesnake, that are slow hunters, are apt to be mottled in blocks of earthy colors. These snakes are quite inconspicuous when resting, but become obvious as their rows of differently colored blotches flash by.

A good illustration of cryptic color ation is found in aquatic turtles, such as the Western painted turtle. The upper shell of this strikingly marked turtle is dark brown or olive, and the lower shell is a patchwork of bright red, yellow and black. Predators approaching from above the water see a mud-like block against a back ground of mud. Predators that approach from beneath are presented with light colored spots that resemble bits of water weeds or sun flecks on the water. A similar dark "upper" and light "lower" is also typical of most frogs and toads.

An animal's eye has a well-defined, distinctive shape and consequently is the most difficult of all body parts to conceal. Some species of snakes and frogs have evolved dark blotches or streaks that pass across the eye to mask it. In these cases, the iris is pig mented to match the surrounding skin color. The result is that the eye no longer appears as a circle, but blends in with two larger color patterns.

Some animals, like the Western painted turtle, have dark, longitudinal stripes that run from the tip of the nose, across the yellow iris, through the pupil and along the side of the

neck. Yellow stripes parallel it above and below so that the overall pattern of the head and neck is like that of stems of grass or pond vegetation.

Birds, likewise, are quite adept at the camouflage game. Among grass land birds there is great uniformity of feather color and pattern. The striations of brown and black found on the song sparrow are not unlike those of the sharp-tailed grouse or upland plover. The background against which prairie birds are seen is more uniform than most environments, so it is not surprising that many resemble brown sweeps of grass with occasional spots of white burning through.

One of the masters of camouflage in the bird community is the American bittern. This wading bird often stands among dense patches of reeds and rushes, its neck and head extended and erect, but is seldom seen. There can be little disagreement over the purpose of this pose, for the plumage of the neck and breast and even

Camouflage among the birds be gins in the nest. The eggs of many birds, especially ground nesters, are mottled in colors and patterns that mimic the light and shadow areas of the nest site. The sharp, circular lines of a bird's egg, much the same as an animal eye, are distinctive shapes in a natural setting, and difficult to hide. Colors and patterns that visually break up the eggs' shape contribute greatly toward their escaping the attention of predators. The eggs of waterfowl and shorebirds are good examples of cryptic coloration and pattern.

Most young birds that leave the nest immediately after hatching are covered with downy coats of mottled colors and patterns. Bristly down conceals their sharp body lines, and spots of brown and black further help the young dissolve into their surroundings. So specialized is this camouflage that the color and color patterns of young birds can sometimes be matched to the plant material used in their nest and to surrounding vegetation. A good example is young horned grebes that are vertically striped in brown and buff and hatched in nests of reeds floating in stands of reeds.

Mammals, on the other hand, are mostly flightless and tied to earth. Their lives are spent among surround ings of brown, gray and black —mud, sand, forest duff, rocks, tree trunks and the light and shadow patterns made by them. It is not surprising that most mammals are colored in shades of brown and gray. Gaily colored mammals are oddities.

Concealment, among mammals, is largely accomplished by the principle of "similar colors"; that is, of match ing their coats to their environment's color. Some mammals employ color patterns to match specific back grounds, but they are few. The bobcat and the deer fawn both wear dappled coats that blend perfectly with the spots of sun falling on a forest floor. Striping on animals, like the thirteen-lined ground squirrel, probably evolved to help them disappear in stands of grass. Indeed, when stand ing erect, "picket pin" fashion, they are quite inconspicuous.

In addition to wearing colors similar to their surroundings, mammals also rely on obliterative shading to blend with their environment. To a biologist, this term means that an animal is darker on the upper part of its body than on its underside.

When any object is viewed out-of doors, with overhead light, the upper surface is more brightly illuminated than its underparts. The effect is to lighten the top and shade the bottom. This light and shade pattern identifies an object as three dimensional. If animals were an overall, uniform tone they would stand out in any setting.

Elimination of body shading, then, is a serious matter to an animal if it is to survive. Natural selection has favored animals whose tops are darker than their undersides because this pattern counteracts the effect of over head light and makes them less conspicuous to other animals. The prevalence of obliterative shading in the animal kingdom demonstrates its usefulness to a predator stalking prey or prey attempting to elude a predator.

In the past, some biologists believed that the large, white patches on mammals such as the striped skunk, white tailed deer and pronghorn, functioned in concealment. Their theory suggested that when viewed on the horizon, the white blended into the sky and thus broke the animal's recognizable body outline. The bold, white coloration of these animals is now believed to function in just the opposite way —by advertising them. A skunk's bold coloration announces to others that he is not to be bothered. The white rump patch of the pronghorn almost certainly serves to warn others of the herd that danger is near, and at least one function of the white tail's white rump is to give pursuing predators a target to center their at tention on. Once the deer gains some distance on its attacker, the tail can be dropped and the predator's focus point literally melts into the woods.

Anti-evolutionists argue that an animal's coloration has nothing to do with camouflage; that particular animals are just coincidentally colored the way they are. They say that it is mere chance that in many species of birds the females are protectively marked and the males not. They ignore the vulnerability of the females while on the nest and their special need for camouflage. They ignore the fact, too, that in the few cases where males stay on the nest and incubate rather than the females, such as the Wilson's phalarope, he is more drab than the female. If color were mere chance, why are polar bears and arctic foxes not black, or buffalo and prairie dogs not white?

There can be little doubt that animals matching the pattern and color of their natural environment are better competitors, and that more of their young make it to maturity and bear young themselves. Those individuals that stand out become easy meals for a legion of hungry predators. Animal camouflage makes prey species less conspicuous to would-be attackers, and predators less conspicuous to potential prey. To animals on the prairie, or in any ecosystem, the value of being obscure can mean the difference between life and death, survival and extinction.

Photograph by Lou Ell

HUNTING DEER

(Continued from page 23)fairly heavy evergreen forests of the Pine Ridge, and is not averse to using river bottom trees, either.

Going after deer in one of these situations would take some specialized techniques, but a lot of deer-hunting lore applies to just about all situations. The lifetime whitetail hunter in heavy timber country might feel a bit out of his element hunting Sand Hills mulies, for example, but he would still have the jump on a first time greenhorn.

"Think Deer"The most valuable asset of any deer hunter is an ability to "think deer". A few gunners get reputations of being lucky, and chance probably plays a role in some cases. But in many instances, these hunters are "lucky" simply because they consciously or subconsciously "think deer" when in the field, and this puts them in the right place at the right time.

Book learning alone will not give a hunter this uncanny ability, although it can be of considerable help. It will take several seasons in the field, preferably in the company of experienced deer hunters, before someone begins to get the feel of his quarry.

A hunter must learn what the deer needs and wants in day-to-day life; seasonal factors that drive him; and the places he goes to meet these wants and needs.

These needs are food, a place to bed during the day and a place to hide from intruders. They are the same for whitetails and mulies, although each species might seek them in different kinds of terrain.

Weather conditions and time of year might also influence deer activities. Different foods might come into season, crop harvests and falling leaves might remove protective cover or preferred foods, and varying temperatures and winds might influence the deer's selection of a bed. The rut, or fall breeding season, and heavy hunting pressure also influence the deer's daily routine, often scrambling the pattern.

Book learning and story telling are good ways to learn the things that motivate deer, and to pick up a few hints on how to in vestigate an area for sign of deer activity. But there will be no feel for deer, no "thinking deer", before several seasons of field work have passed. Just one minute spent looking at and touching a fresh deer bed, noting its size, location relative to the wind and the warming sunshine or cool ing shade and the view it commands, is worth a dozen chapters written on the subject.

Deer SignAfter inspecting a few beds, the hunter NOVEMBER 1974 will see that deer pick warm, sunny beds on a cool day and shady beds when it's warm. They also like to have the wind behind them to bring scent and sound of an intruder, and a good view in front to see trouble approaching.

The comfort and safety factors apply equally to whitetails and mule deer, but the two species generally bed in different terrain. The mule deer is often bedded at the upper end of a canyon, lying behind a light screen of buck brush or weeds just below the crest of the ridge. Usually, the wind is sireh that it will carry him news of an intruder approaching from behind, and he can easily see a good distance down the canyon.

The whitetail prefers a spot in heavy cover. He might trade a heavy thicket for a good view and depend on the crackling and crunching of an enemy moving through the tangle to warn him. Other approaches would most likely be covered by the wind.

The hunter might note other things just from inspecting a few deer beds. An area with three beds, one just barely larger than the others, is very likely a doe with her two nearly grown fawns. A large, solitary bed pressed into the grass some distance away from a spot used by a large group of deer is probably that of a buck.

Any hunter who is at least half awake when moving through deer country should notice other deer sign. Droppings, for instance, tell a hunter with certainty that deer have been in the area. And, if he is observant and applies a little common sense, these little heaps of dark, slightly elongated pellets will tell him considerably more.

If, for instance, they still appear shiny and moist on the outside, they are probably no more than an hour or two old. Droppings a couple of hours old have a dull appearance, but are still soft when prodded with the toe of a boot. Generally, those older than a day are rather crumbly, and at several days, they begin to get downright hard. Of course, this varies considerably with weather. Temperature and humidity could speed or delay the drying process considerably, so the hunter should take recent weather conditions into account.

It might seem that a hunter would be interested only in the freshest sign, but that's not necessarily so. If a particular area has some fresh droppings, some a day or so old and others even older, it means that deer use the area quite regularly. However, nothing but day-old drop pings in one area, for instance, probably means that a fair-sized bunch came through there, but that particular spot is not part of any deer's daily routine.

Other sign in deer country is more specific, tattling on the presence of a buck. Nearly every hunter would like to take a brawny trophy animal, and a good share of deer permits in Nebraska are valid for bucks only.

One sure sign of a buck is a "rub" —a branch or sapling stripped of its bark by a buck knocking the velvet from his antlers. Later in the fall, as the rut approaches, fresh sign of this antlerwork may appear on larger, harder trees, as restless bucks shape up their fighting skills.

An even better sign of a buck, especially in whitetail country, is an active "scrape." This is where a buck has pawed the leaves and grass away, exposing a patch of bare earth from one to three feet in diameter. He generously applies his scent and tracks in the scrape, which serves as a signal to does that he is in the area and available, and warns other bucks that this is his territory and they'd better stay out, or else.

A buck fully caught up in the fever of the rut may have several scrapes which he checks frequently, or he may post just one and stay nearby. Whichever the case, the scrape that is being renewed and maintained is a sure sign that a buck will be along sooner or later, and it merits careful consideration.

Of all the sign a hunter is likely to come across, deer tracks are the most obvious and are also the most misused and misunderstood by the novice. A lot of green horn deer hunters are likely to latch onto the first set of tracks they find and spend the rest of the day following them, almost invariably without seeing the deer.

Tracks are a valuable sign to the hunter, chiefly as an indication of the frequency and direction of travel. They might also give an indication of the size of deer using an area. Generally, they provide a lot of the same information as do droppings.

Some hunters claim they can distinguish tracks of bucks from those of does, but other experienced hunters discount this. Generally, tracks of large does and bucks look identical, although a hunter tracking a deer might surmise he's on the trail of a buck if it is travelling alone and sticking to more secretive haunts.

Following a set of tracks in hopes of getting a shot at the critter making them is an iffy game, and is a tactic mastered only by a few specialists. Most hunters follow a trail too slowly or make too much noise to be successful. And, a lot of hunters cannot distinguish a really fresh track, and thus may take up on a trail half a day old or more.

Most hunters following deer tracks pay way too much attention to the impressions themselves and almost forget to look for the critter standing in the tracks. Experienced trackers look for the most distant visible sign, giving it just a glance while keeping their eyes on the cover ahead, ready for a shot. They also look behind, because deer often double back on their trail to see if they are being pursued.

About the only time most hunters will need to track a deer is after they have

43 MANUFACTURE YOUR OWN

WATERFOWL DECOYS

SAVE ON THE HIGH COST OF TOP

QUALITY GUNNING DECOYS. Manu-

facture your own tough, rugged, solid

plastic decoys with our famous cast

aluminum molding outfits.

We are the originators of this unique do

it-yourself decoy making system. Over a

half million of our decoys now in use. No

special tools needed. Just boil 'em and

make 'em.

We have decoy making outfits for all pop

ular species of ducks and geese, both

regular and oversize. Also for field geese

and ducks.

Write today for colorful catalog of decoys,

paints, and other decoy making acces

sories. Please send 50y (applicable to

first order) to cover handling.

DECOYS UNLIMITED, INC.

CLINTON, IOWA 52732

GOOSE AND DUCK HUNTERS

SPECIAL-

$10.75 PER DAY

PER PERSON

ELECTRIC HEAT

3 MEALS AND LODGING

MODERN MOTEL • TV

OPEN 4:30 A.M. FOR BREAKFAST

Jay & Julie Peterson

J'S OTTER CREEK MARINA

NORTH SIDE LAKE McCONAUGHY

PHONE LEMOYNE 308-355-2341

P.O. LEWELLEN, NEBR. 69147

PALMER GUIDE SERVICE

Pheasants - QuaiI - Ducks - Deer

Home Cooked Meals

Ranch Style Hospitality

Tommy Palmer

Brady, NB. 69123

PHONE

Home (308) 584-3411

OFFICE (308) 584-3437

GUARANTEED TROPHY HUNTING •"NO GAME-NO PAY"

WILD GOAT • WILD SHEEP • RUSSIAN BOAR

For Reservations or Brochure,

Write or Phone:

WOODCLIFF BIG GAME

RANCH

Fremont, Nebraska

Phone: 721-7616

MANUFACTURE YOUR OWN

WATERFOWL DECOYS

SAVE ON THE HIGH COST OF TOP

QUALITY GUNNING DECOYS. Manu-

facture your own tough, rugged, solid

plastic decoys with our famous cast

aluminum molding outfits.

We are the originators of this unique do

it-yourself decoy making system. Over a

half million of our decoys now in use. No

special tools needed. Just boil 'em and

make 'em.

We have decoy making outfits for all pop

ular species of ducks and geese, both

regular and oversize. Also for field geese

and ducks.

Write today for colorful catalog of decoys,

paints, and other decoy making acces

sories. Please send 50y (applicable to

first order) to cover handling.

DECOYS UNLIMITED, INC.

CLINTON, IOWA 52732

GOOSE AND DUCK HUNTERS

SPECIAL-

$10.75 PER DAY

PER PERSON

ELECTRIC HEAT

3 MEALS AND LODGING

MODERN MOTEL • TV

OPEN 4:30 A.M. FOR BREAKFAST

Jay & Julie Peterson

J'S OTTER CREEK MARINA

NORTH SIDE LAKE McCONAUGHY

PHONE LEMOYNE 308-355-2341

P.O. LEWELLEN, NEBR. 69147

PALMER GUIDE SERVICE

Pheasants - QuaiI - Ducks - Deer

Home Cooked Meals

Ranch Style Hospitality

Tommy Palmer

Brady, NB. 69123

PHONE

Home (308) 584-3411

OFFICE (308) 584-3437

GUARANTEED TROPHY HUNTING •"NO GAME-NO PAY"

WILD GOAT • WILD SHEEP • RUSSIAN BOAR

For Reservations or Brochure,

Write or Phone:

WOODCLIFF BIG GAME

RANCH

Fremont, Nebraska

Phone: 721-7616

taken a shot at one. If the deer doesn't go down, the hunter should check where the deer was standing when the shot was fired, looking for blood, hair or other signs of a hit. If none is apparent, he should take up the track for a few hundred yards, looking for blood on the ground, bushes and trees the deer may have brushed against, or for signs of staggering, limping or other evidence of a hit.

If the deer was hit, the gunner should get help if at all possible before taking up the trail. His helper should then do the actual tracking while he scans the surrounding cover, ready for the shot.

Most deer hunters should avoid the "Davy Crockett syndrome", and give up the notion of sneaking up on a deer by following its trail. For most, it simply does not work.

Rather, the gunner should consider tracks along with all the other evidence of deer sign around him. Combining this with a knowledge of what the immediate area has to offer for food and cover, the hunter who is "thinking deer" should have little trouble in working out a successful strategy.

Putting It All TogetherAfter a season or two of apprenticeship, a deer hunter should begin to get an idea of what he's doing. He will probably know what deer eat in the fall -the weeds, corn, tree leaves and buck brush. He'll probably be able to pick out likely bedding areas and escape routes. And, he'll have an idea how the deer uses his excellent nose and radar-like ears to pick up signs of danger.

The hunter's problem now is to put all of this together and come up with a work able strategy for the particular piece of ground in front of him. If he's hunted with good sportsmen in the past, he's come to appreciate the challenge of finding sign, figuring out the deer's habits, and stalking him on foot. Even if he doesn't bag a buck, the experience of the hunt is reward enough.

In selecting his tactic, he'll have none of the ride-'em-down-and-shoot-'em-up methods that a lot of the four-wheel-drive cushion riders dote on. These guys cover a lot of ground, they bag deer, and they call themselves hunters. But, the only as pect of the hunt they take part in is the kill. They deprive themselves of a great out door experience, and they miss out on the satisfaction that comes from outwitting a deer in his own back yard.

Sporting methods of hunting deer vary according to the terrain involved. In heavily timbered areas like those along the Missouri River or other major water ways, direction of deer movement at feed ing time is fairly predictable. The hunter will be dealing with whitetails, who bed in the heavy cover during the day and 44 NEBRASKAland move toward corn fields and weed patches on adjacent farmlands to feed as dark approaches.

If hunting pressure has spooked them away from the fields, deer will be content to munch on tree leaves, a large variety of shrubs, chokecherry bushes and even pine needles. But even then, they will have to head for the edge of the big patches of timber.

Stands of mature trees offer little under growth for deer to eat, but there is sufficient food along the edges, around clearings, and in the new growth in areas once cleared by fire, logging or clearing.

One good tactic would be to take a position along the edge of the timber or inside the timber near a trail leading from bedding to feeding areas. Chances of ambushing a buck along one of these routes are good around dawn and dusk.

During the rest of the day, a hunter might spend his time still hunting, a tactic where he walks ever so slowly and quietly through deer cover. A good still hunter will spend a lot more time using his eyes and ears than his feet, perhaps taking only one or two steps, then carefully scanning the woods for a minute or more.

Two or three hunters can sometimes team up in cases like this, and can have good success. Some teams have done well with one posted on an escape route while another still hunts in the area. Sometimes, the hunter on the move gets the shot, but more often, the gunner on the stand gets the opportunity while the buck's attention is focused on flanking the moving hunter.

Another tactic is for two hunters to still hunt into the wind along parallel paths, but moving alternately. Hunter No. 1 moves slowly for about 10 minutes, while No. 2 hunkers behind a bush or against a tree. Then, both remain still for 5 minutes, until hunter No. 2 begins to move while No. 1 watches. Chances are good that deer flushed by the moving hunter will attempt to circle him, giving the other a shot.

This tactic works well when covering a ridge with one hunter on each side, as flushed deer will most likely go over the ridge to the other hunter. The moving deer should be easy to spot, especially if they silhouette themselves against the sky for an instant when topping the ridge. Mulies usually stop at the top to inspect their back trail, but seldom does a whitetail.

The well-prepared deer hunter would have spent a day or two before the season scouting his hunting territory before opening day, if at all possible. But, even if he couldn't make an early reconnaissance, his first day of still hunting and stalking would provide much of the same information. Perhaps in following days, the hunter might be able to successfully stake out a scrape or wait out a buck on a well-used trail found while still hunting.

Different and rather specialized techniques might be called for in hunting farmland deer. These critters are virtually surrounded by food, but their cover is limited to wooded creeks, draws and a few shelterbelts. They are used to a lot of human activity and have grown so adept at using the limited cover available that they can exist in a fairly well-populated area almost unseen.

Knowing favorite travel routes pays extra dividends in this situation, especially early in the season before the deer are spooked by hunting pressure. A favorite tactic here, as well as in most other parts of the state, is to set up in a strategic tree or haystack at dawn and dusk and wait for a buck to come along.

During the rest of the day, farmland deer are likely to stay in the wooded areas unless hunting pressure is heavy and the corn is still standing in the field. The corn is doubly attractive to hard-pressed deer, providing both food and an excellent refuge from hunters. A good-sized cornfield can hide a surprising number of deer, and they seem able to give hunters the slip all day long without giving them a shot or leaving the field.

Of course, hunters understand a farmer's reluctance to let them thunder around in an unharvested field because of the stalks and ears they might knock down. In cases like that, the best strategy might be to move on to another area, or help the farmer pick his corn.

In some cases, hunters can get a crack at these cornfield bucks by pussyfooting along the edge of the field trying to spot a deer bedded or standing within range. Deer like to eat corn, but they seem to prefer a little variety in their diet; perhaps a few tree leaves, shrubs or weeds. They might be tempted to leave the field for a little browsing at dusk, especially if things have been quiet for a while. A gunner might have some success waiting for a shot at a vantage point between cornfield and timber.

Farther west, in mule deer country, a

But a lot of hunters do well afoot, walk ing brushy canyons in hopes of finding bedded deer during the middle part of the day. Generally, hunters have the best success moving into the wind, and some say they prefer to keep the sun behind them if possible. Mule deer often bed at the head of these pockets or somewhere near the top of the ridge. From there they can take a couple of quick hops and be out of sight in the next canyon in a split second should danger approach.

Hunting into the wind will deprive the deer of early warning from scent, and the sun at the hunter's back will not flare in his scope when he raises his rifle. Some hunters prefer to stay high on the rims of the canyons, saying that this gives them more of a chance for a shot at a departing deer. Others like to get right down into the cover, feeling that a lot of deer sit tight and let hunters walk right on by. Both philosophies probably have merit.

At dawn and dusk, mule deer begin to move to feeding areas, just like whitetails. Favored spots include both croplands, with corn, alfalfa and winter wheat, and areas of wild forage such as chokecherry, plum, buck brush or some tender grasses.

At this time of day, the hunter on the stand has an advantage. Most often, this stand is the ever-present haystack, which is often located on the fields and meadows the deer visit. Other vantage points might include trees, windmill or strategic knoll; anything that provides a good view, a steady shooting rest and concealment.