NEBRASKAland

August 1974 50 cents

NEBRASKAland

VOL. 52 / NO. 8 / AUGUST 1974 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Fifty cents per copy. Subscription rates $5 for one year, $9 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. commission Chairman: Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-central District, (308) 452-3800 Vice Chairman: James W. McNair, Imperial Southwest District, (308) 882-4425 Second Vice Chairman: Jack D. Obbink, Lincoln Southeast District, (402) 488-3862 Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-central District, (308) 745-1694 Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Director: Willard R. Barbee Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, Jr. Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: Jon Farrar, Ken Bouc, Faye Musil Photography: Greg Beaumont, Bob Grier, Steve O'Hare Layout Design: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1974. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska Travel articles financially supported by Department of Economic Development Ronald J. Mertens, Deputy Director John Rosenow, Travel and Tourism Director Contents FEATURES IT'S THE BERRIES THE PRESSURE IS ON WHAT'S BUGGING THAT FISH? TOO RICH TOO SOON YOUR WILDLIFE LANDS/THE PANHANDLE PRAIRIE LIFE/PASSING OF THE BUFFALO . PUMPKIN RUN. NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA/COMMON SNIPE . 8 12 16 18 36 40 42 DEPARTMENTS SPEAK UP TRADING POST 49 COVER: With a somewhat limited range in Nebraska, primarily in the northwest corner, the porcupine enjoys a relatively tranquil existence, worrying mainly about which tree to eat next; photo by Bob Grier. OPPOSITE: Easily recognized by its grayish-white, fuzzy appearance, woolly plantain is an annual forb that is conspicuous through the summer. Common to the dry plains and prairies, woolly plantain shows up most often on overgrazed land, especially around windmill sites; photo by Jon Farrar.

Speak up

Old Fish TaleSir / Back in 1924 my brother and I lived in Stanton County, and we always had an idea there were large catfish in the Elkhorn River. Many times we had setlines out, and used all kinds of bait —dough balls, liver and such. One morning early in June we looked at our lines and behold, we had a large one. He was everywhere trying to get away, but the water was shallow and he couldn't go anywhere. My brother and I dragged him to the bank with help of a neighbor who had a rope. The fish's mouth was large enough you could put two fists into it. We had to half carry and half drag him home, where we weighed him — 48 V2 pounds and 4 feet from nose to tail. It was a blue channel cat, probably came up from the Missouri River when the water was high.

Paul Print Denver, Colo. Plastic Junk Sir / I liked the article "Learning to Care" (February NEBRASKAland). Educational programs on the environment are long overdue. It is ironic that government, business and the public give lip service to ecology but still continue to abuse their environment. I think it is a form of hypocrisy to encourage people not to litter and pollute our world, yet condone the use of certain disposable materials that are, in fact, in disposable. In particular I am speaking of the various plastic-type cups, bottles, forks, spoons, etc. This stuff that people are throwing away is collecting in our lakes, rivers, and countryside. Also, no one has proven that plastic residue from hot containers is not harmful to body tissue. If we must have disposable consumer products, let's return to paper and wood. Concerned sportsmen and the public can help solve the problem by refusing to buy the plastic junk on the market. Stan Novak Omaha, Nebr. Storm King (lark bunting) They will fly into a gale, battling their way along, and in the midst of their travail, all burst into song; they sing through storms as they sang below, as if life exists for this: as if in the grip of the worst that blows — singing, one can capture bliss. Doris Wight Barbaboo, Wise.For the benefit of those who have acquired the mysterious skills of knitting, Mrs. Paula Robinson of Lincoln has provided the secrets for manufacturing a "Go Big Red" poncho. While readily admitting it is a beautiful creation, as well as being practical and "patriotic", we are uncertain that the following little numbers and symbols are anything but a coded message to some alien forces —possibly the coach of an opposition football team supplying him with all of Nebraska's plays. However, because of our faith in Mrs. Robinson, and in hopes that others will benefit from her efforts, we will pass the message along. So, here are her directions. (Editor)

"GO BIG RED" PONCHOMaterials Required: Four 4 oz. skeins red orlon knitting worsted yarn and two 4 oz. skeins white orlon yarn. One pair Size 11 knitting needles and one Size G crochet hook.

With red yarn — cast on 106 sts. P one row. Dec'ing 1 st each side every other row 3 times, work in St St, end on wrong side.

Then begin Go Big Red as follows:

Row 1-Right side: With white-K 2 tog, k to last 2 sts, K 2 tog. Row 2 - P. Row 3 — K 2 tog, work row 3 on chart from right to left. Row 4 —P row 4 on chart from left to right. Continue to dec 1 each side every other row, working to top of chart and making rows 13 and 14 white only. Break off white and continue with red only. Continue to dec 1 each side every other row until 22 sts remain on needle. Bind off.

Make 3 more pieces the same. Sew seams, matching pattern.

With red —crochet 2 rows of sc around neck, holding in to fit.

Fringe: Wrap yarn around a 6" cardboard. Cut at one end. Fold 4 in half and draw loop through st at lower corner, then draw ends through loop. Make fringe in every 3rd st around lower edge. Trim fringe evenly.

Poncho is machine washable and dryable if orlon yarn is used, and therefore can't be hurt if you're caught in the rain at one of the games.

Paula Robinson Lincoln, NebraskaNEBRASKAland Magazine invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to Speak Up. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters. — Editor.

It's the Berries

Wild fruits offer a mind-boggling array of taste-tempters for table and pantry

I GUESS I'VE BEEN looked upon as a little crazy for a long time, but in the last few years I've become a home canning nut. "It's so easy to go to the store and buy it," folks say, but I just go about my business, pickling beets and crabapples, brandying peaches and apricots, freezing cherries and mulberries, and making rhubarb jelly.

Then in the summer of 1973, with food prices sky rocketing, I got hooked on wild fruits, as well. It started one day when some friends and relatives drove out to pick sweet corn for our freezers.

Driving back from the field, we came upon a wild plum thicket along an overgrown country road. I'd never been big on wild plums, but I was almost out of jelly, and they looked so enticing, that I voted "yes" when someone suggested stopping to pick some. Besides, they were ripe, and free.

At the welcome conclusion of an 8 p.m. to 3 a.m. corn-processing session, I gained custody of almost all the plums.

Well, the next thing I knew I was pouring a rather thin butter into jars. That was about midnight the follow ing night. I figured it would thicken as it cooled; and I was tired. But, I was wrong. It was good syrup consistency though, which led me to another idea.

I decided plum pancake syrup might be good, so I reprocessed only about half of my butter for bread spreading purposes. (I just hadn't cooked it long enough). The rest became the most kid-pleasing pancake syrup that ever graced a pantry shelf, or breakfast table.

As a person who takes the specific and makes grandiose generalizations, I decided then and there that all wild fruits must have fantastic flavor and offer a mind boggling plethora of varied and tasty uses. So, I determined to pick everything I could find (that the birds and animals didn't get first) and make something out of it, whatever it was.

My second experiment was with elderberries. To begin with, I was a little disappointed with elderberries. I found a clump of them along some old railroad tracks and immediately sampled them. Couldn't say enough things about their unaltered, natural flavor; most of them bad. Then I thought about picking them. One at a time, that could take a considerable while. So I dropped that project.

When I walked into the office next day and mentioned my experience with that particular wild fruit, and my impressions, I got two reactions. The first was: "You dummy, they don't taste like anything by themselves, but spruce 'em up a little with some sugar and lemon juice and a little pectin and they're the best tastin' wild thing you'll ever find. They'll beat those plums you're so proud of ten times runnin'". The second reaction was a third degree on the location of my hunting spot.

That did it. I decided to go back out and pick elder berries. By this time someone had tipped me off that you cut off the entire fruit-bearing head, and I did notice that all recipes called for so many pounds of elderberries—with stems. You cook them with the whole head intact, I was told.

I subsequently picked 16 pounds of elderberries with stems, then started wondering what I would do with that much jelly. Even Christmas gifts wouldn't take up the slack. That's when I started thinking about elder berry wine. I'd heard it was really good.

So, after making all the jelly I thought my family could eat in the next generation, I started working on the wine. Jelly and syrup, I found, are as simple as plum butter. Just follow the recipe on the commercial pectin package, then use only half as much pectin for syrup as you would for jelly.

But jelly and syrup were nothing compared to wine making. Wine-making is a family project. First you find an old oaken bucket (any modern plastic substitute will do, as long as it's big enough). Then you locate a couple of kids —your own are a good choice. Then all you do is climb into the bucket with your bare feet, preferably clean, and start stomping. I had a slight elderberry stomping accident. An old friend dropped over while I was in the bathtub, enthusiastically treading on my dark purple fruit (the kids had already been stomped out and had stomped off to bed).

Try to imagine the effect on a conservative old friend, of being met at the door by a purple-footed person, grinning from ear to ear, and asking if he'd like to join her in the bathroom because she has this project that needs to be finished immediately. By the way, elder berries do stain porcelain, but the blue wears off in time. I realized later I could have used a wooden masher instead of feet, but tradition suffers. Anyway, that can wait until next year.

It wasn't long before my reputation got around. Soon I was finding wine-making cartoons posted on my door, and people would come to the house to sniff the fermentation in the crock in my kitchen, then gratefully race home to the tuna or onions or liver in their own kitchens.

The wine? Well, it was really nice, dry wine. I suspect any wine recipe will do, but be sure to bottle it sometime. Don't forget and let half of it sit with fermentation caps on once you've sampled the first batch — I can almost promise it will eventually turn to vinegar. Of course, if you're out of vinegar.

Seems I spent so much time making the wine that I forgot to check for other fruits, and I was too late getting started for others. This year, though...well, first there are strawberries, then chokecherries, and elderberries (we really did go through that jelly), and plums, and wild black cherries, grapes, sand cherries, mulberries, goose berries, raspberries, and currants —I bet dried currants would be neat....

Salt Valley Lakes around Lincoln provide 300,000 angler-days of fishing every year

THE PRESSURE IS ON

THE COMPLETION of 13 flood control reservoirs in the Salt Valley watershed system near Lincoln in the mid 1960s brought an unprecedented opportunity for fishing and outdoor recreation to the densely populated southeast area of Nebraska.

Prior to completion of the reservoir system, fishermen were limited to warmwater rivers and streams, and the occasional private sandpit or farm pond they could get permission to fish. The lakes opened over 4,000 water acres to the public and almost over night became a mecca to the fishing enthusiast.

Today, the Salt Valley system handles nearly 300,000 angler-days annually, and almost 80 percent of all fishing by area residents takes place on waters of the 13 lakes.

The new waters brought a greater variety of fish to anglers, as well as expanded opportunity. Where catfish was once king, now largemouth bass, walleye, northern pike and panfish like the crappie and bluegill have become available and popular. The lakes did nothing to hurt catfishing, though, and several of the reservoirs quickly established an excellent catfish population, with good natural reproduction.

The lakes also presented a good opportunity to fisheries biologists with the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, who began to stock each of the impoundments even before work on the dams was completed.

Salt Valley waters were quick in establishing good populations of panfish, with bass and catfish taking somewhat longer.

Branched OakLargest of the Salt Valley lakes, Branched Oak Lake has 1,800 water acres available to the fishermen. Because of its size, the lake rates high in the variety of desirable fish populations, and that attracts anglers.

This lake is one of few Salt Valley impoundments that has a reproducing population of walleye. Anglers fishing from the face of the dam during this spring's walleye spawning period, when the water reached 45 to 50 degrees, took a good number of fish. Because of the nature of the spawning run, fishing was good for only a two-day period, however.

Later in the summer, anglers fish ing deeper, open water began picking up the walleye again, usually in the 10 to 12-foot depths. Nightcrawlers and minnows fished slowly on the bottom produced well. Walleye avoid structures, such as heavy tree beds and brush, preferring underwater sand banks and fiats with dropoffs and ledges to hide under.

Branched Oak is also one of the best largemouth bass lakes in the Salt Valley, and is getting good natural reproduction in the spring. Structure fishing — locating underwater brush and ledges —and fishing among the stands of trees in the west end of the lake, have been very successful. Spinners and rubber worms are the most productive lures.

The white crappie is Branched Oak's "bread and butter" species. This year most crappie average from 9 to 12 inches in length. Crappie are cyclic, and have "year classes" where

Photograph by Bob Grier

Photograph by Bob Grier

most fish are the same age and same size.

Another popular panfish, the bluegill, is not faring as well in the large lake. Branched Oak's bluegill are good size, but numbers have declined the last few years. Fish caught this year average up to 9 inches in length.

The Game Commission stocked nearly 300,000 catfish in Branched Oak between 1968 and 1971. Biologists have been unable to determine if the lake has natural catfish reproduction, but a maintenance stocking program can provide catfish to the sportsmen if the lake is not able to establish a reproducing population.

Like many other Salt Valley lakes, northern pike stockings have not taken hold in Branched Oak, although there may be some 20-pound northerns lurking in the lake from original stockings.

Another popular panfish is the bullhead, and fishermen this spring caught nice stringers of 14-inchers using worms fished on the bottom.

PawneePawnee Lake, near Emerald, is an other Salt Valley lake with natural walleye reproduction. The lake is 740 acres in size and perhaps best known for its crappie. Pawnee crappie average between 8 and 9 inches, but what they lack in size they make up for in numbers. The popular panfish can be caught off the dam year around, with excellent ice fishing in February. Crappie fishermen also do well during the spring and summer working the standing trees and brushy areas.

Pawnee has a strong population of larger bass, with several in the 7 pound class caught this spring. Again, structure fishing around sunken trees and brush produces best.

The lake is blessed with large blue gill populations, and ice fishing in the trees produces well. The scrappy blue gill can be caught almost anywhere in the lake during the summer months.

ConestogaThis 230-acre lake 3 miles south of Emerald appears best for largemouth bass. It has good-size fish, and good populations. Biologists believe Conestoga will be a good bass producer for several years.

Bluegill are another reliable fish at Conestoga, with tremendous numbers and good size. Although the bluegill situation is presently strong, biologists believe it will decline in the next few years.

Conestoga once had the largest number of crappie, but their numbers have declined since 1973. There are keeper-size fish present, however, and while their numbers are dwindling, there is still good crappie fishing there.

Catfish were stocked in the fall of 1972, and these fish are presently in the 12 and 15-inch range. The lake also has a number of catfish surviving from the first stockings in the mid-1960s, and biologists have seen a number of fish up to 20 pounds.

Management of the lake indicates a need for continued stocking of walleye, with good walleye fishing still years away.

BluestemPrimarily a largemouth lake, Blue stem has 320 acres of water with good bass and large crappie populations. The lake also has good reproduction of catfish, but most other species show little size.

Killdeer, Hedgefield, and Lake 57A

These smaller lakes are good for largemouth bass and bluegill, although 57A has numerous small crappie. Hedgefield and Killdeer have some catfish, and biologists hope to maintain the catfish through stocking programs.

Olive CreekWith 145 acres, Olive Creek is surprising because of its naturally reproducing walleye population. Besides walleye, biologists hope to get good crappie fishing within the next two years. Olive Creek is a fair largemouth fishery, with some bluegill and catfish.

Walleye dominate the lake's predator population, and while a stocking of 150,000 northern pike did succeed, the lake remains marginal for that species.

Yankee HillWith 210 acres available, Yankee Hill's most important fish has been the crappie, although biologists have watched their numbers dwindle. The lake also has good-size bluegill, large bull heads and a fair number of walleye.

StagecoachSouthwest of Hickman, Stagecoach comprises 120 acres and has good populations of catfish and white perch. For the angler who knows how to catch white perch, Stagecoach has the greatest numbers, although they do not grow much beyond 12 or 13 inches.

The white perch looks much like a white bass, and is considered a top notch sport fish and table fare. It appears that bottom fishing in the shallows with worms in May is the most productive combination.

Catfish were stocked in the spring of 1973 and now run from 12 to 14 inches in length. There are a few remaining from past stockings, and these are in the 16-pound range.

Walleye were stocked in Stage coach in 1973, and biologists hope that this species will provide good fishing by 1976. Some maintenance of the lake's white perch population is being contemplated, because like crappie, white perch tend to overpopulate and outrun the available food supply.

Wagon TrainThis 315-acre lake east of Hickman underwent partial renovation in the spring of 1974. Biologists feel that the largemouth bass will do well after the removal of gizzard shad, perch and carp, and that bass reproduction should be strong.

Holmes ParkLocated on the Southeast edge of Lincoln, Holmes Park Lake has large mouth bass, catfish and crappie. Most of the lake's fish are stunted, however, with vast numbers of small bluegill and crappie showing up in survey nettings.

Catfish in Holmes are stunted and only 1 out of 300 is keeper size, with the majority running from 3 to 7 inches in length.

East and West TwinTwin Lakes near Pleasantdale has 255 acres, with northern pike the main attraction. The two connected lakes are one of the few Salt Valley impoundments with natural northern pike reproduction, providing good ice fishing.

The lake also has walleye, large mouth and catfish. Game Commission biologists plan a maintenance stock ing program to maintain these popuar species.

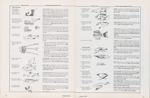

WHAT'S BUGGING THAT FISH

FISHING IS one of the most popular participation sports in Nebraska, with close to a quarter million fishing permits issued to residents and visitors each year. And, the anticipated outcome of any fishing trip for novice or veteran is a lip-smacking fish fry.

Occasionally, though, anglers may hook fish that show signs of infection or parasitism. Before throwing the fish away, check it carefully. Most are healthy, and studies have shown that very few fish diseases can be transferred to man. Virtually all fish are okay when thoroughly cooked, smoked or frozen.

This article should help identify most of the conditions of those occasional fish that show signs of disease or parasitism. Generally, a fisherman will see the results of an infection or parasite rather than the organisms themselves. Consequently, these visual characters or signs are cited to assist in identification of the infective agent.

Parasitism is a way of life. It exists in the plant kingdom and in practically every major group of the animal kingdom. A parasite is an organism that lives in or on another larger organism of a different species (the host) from which it derives nourishment. Depending upon the particular parasite, the relationship may be temporary or permanent. Some parasites can cause disease, and thus become economically important. Damage can be caused in a number of ways —by blocking passages, by penetrating walls, by diverting part of the food supply, by allowing secondary infections, and by other means.

There are nine major groups of parasites and disease-causing organ isms found in Nebraska fish. Parasites seldom harm their hosts, except when they are quite numerous or the fish is under stress from some other cause.

Viruses and bacteria cause several diseases. While these minute microorganisms cannot be seen with the naked eye, an angler can spot the symptoms, which range from "pop eye" to swollen, bloody fins.

Commonly found in fresh water, fungi are thread-like plants that lack chlorophyll. These parasites do not attack normal, healthy fish. However, if a fish is injured and its protective mucous coating is removed, a fungus growth could eventually cause death.

Small, single-celled organisms called protozoa may cause a variety of fish diseases. They can be found in cysts on the gills, embedded in the flesh, or free on the surface of the body. Some protozoa can be seen with a magnifying glass, while others necessitate the use of a microscope.

The larval stage of several trematode worms or flukes is usually found in cysts in the flesh or on the internal organs. However, they can also occur in the eye and other parts of a fish. Although potentially harmful to some fish-eating animals, flukes are not dangerous to man if the fish is prepared properly. Adult flukes can also be found in many organs of a fish, but they will seldom be seen unless one specifically looks for them.

A variety of larval and adult cestodes or tapeworms infect many Nebraska fishes. Larval tapeworms are found in cysts on or in the internal organs or free in the body cavity. Adult tapeworms inhabit the intestines, and the white worms may be seen when an intestine is accidentally slit in cleaning.

Fishermen will seldom see an acanthocephalan or spiny-headed worm. The adults normally live in the intestine, although one species may some times be found in the body cavity with its head buried in the intestinal wall. Larval acanthocephalans occur as white cysts attached to the internal organs. While not harmful to man, spiny-headed worms may cause in jury to the intestine of a fish if present in large numbers.

One of the most common parasites found in fish, nematodes or round worms sometimes occur in great numbers. The larval stage may be found in cysts or coiled on or in the internal organs. Adult roundworms generally attach themselves to the intestine, although some may coil

Leeches may be external, blood feeding parasites. They may adhere to almost any part of the body, but seem to prefer the fins. Leeches will leave small circular wounds, which may become infected with bacteria or fungi. They do not harm the flesh and can simply be discarded when a fish is cleaned.

A highly diversified group of parasites, copepods (small crustaceans) are found embedded in the flesh, attached to the gills or mouth, or moving freely over the surface of the body. If they occur in large numbers, some species can kill young fish. Other

After examining a fish and removing the useable flesh, care should be taken in disposing of the remains. Don't throw the body back into a lake or stream. Some parasites can continue their life cycles if they are returned to water. If fishing on a state-operated area, follow posted in structions or place the remains in drums supplied for waste. On private land, ask permission to bury the remains. If the fish is cleaned at home, dispose of the fish in the normal manner.

HANDLING FISHFish secrete a protective mucous coating which helps prevent fungal and bacterial infections. If this mucous is damaged, the fish becomes much more susceptible to infection.

Size limits are now in effect on some fish species in Nebraska, and it behooves anglers to take extra care when returning under-size fish to the water. The mucous coat probably will not be harmed if a hook is removed while the fish is still in the water or if the angler wets his hands before handling the fish. In addition, the fish should be released gently after the hook is removed, rather than tossed into the water.

The true sportsman always utilizes fish he catches, even those that be come little more than pieces when trimming is done. However, this practice looms even more important in this time of shortages.

Found Externally

Found Externally

Various Bacteria (such as Aeromonas sp.*). Commonly found in water, Aeromonas normally does not infect fish, unless they have undergone some stress. Fish with severe popeye or dropsy probably will not bite, but can be seen dead or in distress along the shore. In some cases, open bloody wounds can result from the bacterial infection. Edible, if wound is superficial; remove infected tissues and cook well. If popeye is indicated, destroy fish.

Anchor Worm (Lernaea sp.). This copepod buries only its anchor-shaped head into a fish's flesh. The remaining portion will hang free from the wound, where a red inflamed pustule may form. This parasite may drop off, leaving only the inflamed area. Edible. Removed inflamed area; clean and prepare as usual.

Fish Louse (Argulus sp.). This rarely seen copepod leaves a fish soon after it's removed from the water. It feeds on the blood by piercing the skin, destroying the protective mucous coat in the process. Thus, secondary infection from bacteria or fungus can result. Edible. Clean and prepare as usual.

Ich (Ichthyophthirius sp.). The most common protozoan encountered by fishermen, Ich appears as mobile white spots or clusters on the skin or gills. It burrows under the skin and may cause surface lesions. Individuals can be seen with a magnifying glass. Edible. Clean and prepare as usual.

A. (Ergasilus sp.). When numerous, these copepods can kill young fish. Their presence is indicated by V-shaped white egg sacs on the inner edges of the gills. Edible. Clean and prepare as usual.

B. (Achtheres sp.). Larger than Ergasilus, this copepod attaches itself in the mouth or to the inner surface of the gills. Achtheres has a short plump body with armlike appendages that cling to the fish. Edible. Clean and prepare as usual.

C. Yellow Grub (Clinostomum sp.). This larval fluke forms cream-colored cysts on the gills and under the skin in the mouth. It can easily be seen with a magnifying glass if cyst is broken. Edible. Clean and prepare as usual.

(Myxosporidia). The white cysts created by Myxosporidia hold thousands of the microscopic protozoans. While certain species cause some important diseases in fish, none have been found in Nebraska. Edible. Clean and prepare.

Water Fungus (Saprolegnia sp.). Usually found on fish in jured by improper handling or other cause. When established, Water Fungus can kill a fish by completely covering it. Edible. Skin fish; remove infected area and adjacent flesh; prepare as usual.

Columnaris Disease (Condrococcus columnaris). This bacterial infection may be found on catfish, trout, and possibly other species. Frayed fins and bloody wounds are other indicators. Edible. Clean and prepare as usual.

Black Spot {Neascus sp.). The easiest disease to recognize, Black Spot is caused by larval flukes burrowing under the skin. Appearing as small round black spots, the cysts may also be found in the flesh. Edible. Skin and prepare as usual.

Eye Fluke {Diplostomulum sp.). These tiny larval flukes will not be seen. They live in the fluid of the eye and eventually cause blindness. Eye may be opaque or shrunken. Edible. Clean and prepare as usual.

Leeches. Conspicuous, blood-feeding, external parasites, eeches produce a small circular wound that remains even though the leech moves or drops off. Edible. Clean and prepare as usual.

Round Worms (Camallanus sp.). Various roundworms are found throughout the intestine. The species that lives in the ower large intestine will occasionally extend from the anus. Edible. Clean and prepare as usual.

Round Worms {Philometra sp.). Normally found on carp, buffalo, and suckers, this adult roundworm lives just under the skin. Edible. Clean and prepare as usual. sp. = species

Yellow Grub {Clinostomum sp.). Cream-colored cysts found in many parts of the body contain larval flukes that become adults in birds. Numerous at times, the Yellow Grub will emerge if cyst is broken in water. If practical, remove cysts from flesh; clean and prepare as usual. Otherwise, discard entire fish.

White Grub (Hysteromorpha sp.). Smaller and lighter colored than the Yellow Grub. These larval flukes are most often found in catfish. Use same as above.

Unknown. An unusual problem apparently found only in walleye. Fish show no external symptoms or abnormal be havior. The rough, sandy flesh is found in varying intensity when fish is filleted but the flesh is always somewhat discolored. DO NOT EAT. Wrap fish in plastic or foil (do not freeze) and notify nearest Game and Parks Commission office.

Tapeworm (Ligula sp.). This larval tapeworm is found free in the body cavity of minnows, carp, suckers, and some other fish. It is uncommonly large and may create an abdominal bulge. Edible. Clean and prepare as usual.

(Contracaecum sp.). Found on the internal organs or the wall of the body cavity, these larval roundworms are immobile. They become adult in fish-eating birds. Edible. Clean and prepare as usual.

White Grub {Neascus sp.). These larval flukes occasionally occur in quite large numbers. Edible. Clean and prepare. Larval Spiny-Headed Worm or Larval Tapeworm. These cysts are larger, whiter, and not as round as those described in No. 18. Edible. Clean and prepare as usual.

Larval Tapeworm. Some tapeworms are not found in cysts. Numerous worms may infect the ovaries of bass. Edible. Clean and prepare as usual. Roe can be cleaned by removing worms with tweezers before preparing.

Larval Roundworm. Often found in great numbers, these cysts will give a sandy appearance to a fish's innards. Edible. Clean and prepare as usual.

Spiny-Headed Worm {Pomphorhynchus sp.). Since most adult acanthocephalans live inside the intestine, they are not seen by fishermen. However, this species can be found lying in the body cavity with its head buried in the intestine. Edible. Clean and prepare as usual.

Intestinal Worms (Adult Helminths). Adult flukes, tape worms, roundworms, and spiny-headed worms will riot normally be seen by fishermen unless the intestine is accidentally cut in cleaning. Edible. Clean and prepare.

Too Rich Too Soon

Overload of nutrients in river could spell doom for state's major source of water-related recreation

(The following is an abbreviation of Myers' Master's Thesis)AS THE AMOUNT of leisure time available to Americans increases, the role of recreation takes on added importance. Because of this, Lake McConaughy is a vital element to Nebraska and the neighboring region. Originally developed for irrigation, power production and flood control, "Big Mac's" recreation significance is expanding rapidly. Classification of all services provided by the lake is virtually impossible. Swimming, boating, water skiing, scuba diving and leisure relaxation attract thousands each year. Probably the greatest single recreational service is its fishery; the backbone of this activity for the entire state for a variety of reasons. One is the large spectrum of fish species that inhabit the lake. Another is the opportunity for anglers to catch trophy fish, attested to by the list of record fish coming from its waters. The high yield of eggs from resident fish, providing stocking material for reservoirs in Nebraska and other states, is another important contribution. Perhaps the most unique feature of the impoundment is that it supports the favored rainbow trout, and those inhabiting Lake McConaughy represent a high percentage of the state's rainbow trout population. In addition, some upstream tributaries furnish the environment necessary for reproduction, while the lake provides a year-round habitat suitable for growth. The result is that anglers over 100 miles upstream can benefit from the trout production, as well as those fishing the waters of the lake itself.

The many factors responsible for maximum gain from Lake McConaughy can be roughly classified into two major categories: quantity and quality. Until recently, the chief concern was quantity —for irrigation, power production and flood control. As recreation grows in importance, however, more emphasis is being placed on quality. The relationship between water quality and the value of water for sports activities is a delicate one. Any degradation of quality will be followed by a decline in some activity. The reservoir's value for recreation and aesthetic pleasure can best be explained by understanding the term "eutrophication."

Basically, eutrophication is the enrichment or fertilization of a body of water to such a degree that beneficial uses are lost. Under the proper conditions, aquatic plants thrive and promote an increase in numbers of small animals that depend upon them for food. These animals, in turn, become food for small fish which are preyed upon by larger fish. The system can be likened to a pyramid, with the total number of plants as the base, small animals next, and so on until large fish form the pyramid's point. In other words, there are many small plants, but, proportionally, only a few large fish. The factor controlling the pyramid's development is the initial production of plants. If production is high, proportional increases will be noted throughout. However, if plant production is too high or too rapid, it (Continued on page 44)

Your Wildlife Lands The Panhandle

This is the second in a series of six guides to Nebraska wildlife lands. When complete, they will cover all of these unique parcels of land that are scattered across the state. A new brochure will appear in NEBRASKAland every six months as a lift-out Like Panhandle and Platte Valley brochures, they are designed to pull out of the center of the magazine, and might be bound to gether to provide a complete reference on these wildlife homes. "Wildlife lands are the grand and the fine; the buffalo and the pasque flower. They are a prayer for tomorrow..." The wildlife lands, here as

elsewhere across state,

receive very little tending

The wildlife lands, here as

elsewhere across state,

receive very little tending

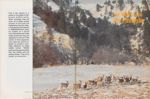

WIND WHIPS through an open valley and whistles down sheer canyons, carry ing snow. Wind tears loose sand from choppy dunes, mixing the driving grains with snow. The sky closes in, obliterating the sun and all the world is white, bitter emptiness.

A too-early buffalo calf takes its first befuddled breath in blizzard air- the late season storm its first sensation and stands on wobbly legs beside its mother to begin enduring the harsh realities of a big country, where home stretches for hundreds of miles.

The Panhandle bred both the raging blizzard and the silent calf—steel and velvet. Wide openness does little to break wind that whips from the mountains to the northwest. Settlers and immigrants, ranchers and farmers have alternately cursed and blessed this country where wind blows free and for as far as the eye can see stretches many, many miles.

Buffalo did indeed roam the Panhandle 150 years ago, by the thousands, but the deer and the antelope's play was probably more like a struggle for survival —at least in winter.

Yet the Panhandle can be gentle, and in spring, at calving time, tender new grasses and delicate wildflowers people the hills and valleys with color and fragrance. Perhaps Indian children noticed them as they romped in the grass. Perhaps pioneer children wore them in their hair.

There was a natural balance in the Panhandle once, though it wasn't a Panhandle then. It was just an expanse of land where Indians depended on buffalo; depended on grass; and a thousand other interdependencies were interwoven.

But men came to slaughter the buffalo—almost to extinction —and the Indian was crippled; without food, clothing, shelter. He was settled on reservations, but not without a fight, and some of the last battles of the Indian Wars took place in the Pine Ridge. According to one armchair his torian, "still there were deer, antelope, elk, bear and other big game to feed them, along with various kinds of smaller game. The streams were still alive with fish, the marshes with wild fowl." That was true for awhile.

Today the wide Platte Valley, where

The buffalo are nearly gone, and so are the elk. A bear hasn't been seen there for many decades, but in Wild cat Hills is a big-game refuge where buffalo and elk remain.

Big-game hunting can be found on the Pine Ridge areas. Deer, both white-tailed and mule, along with wild turkey, roam the Ridge.

And at Smith Lake are waterfowl hunting and lake fishing. Here, on what was a great desert during past eons of geologic time, is now a grass frozen sand sea, interspersed with little lakes that sit on the top of a high water table. Smith is one of those lakes. Marsh and wet meadow are home for water-loving animals and birds not found commonly in the high Pine Ridge, or dry Wildcat Hills, or along the meandering Nine Mile Creek that wanders through the midst of an agricultural region.

Trout fishing has been restored to the Panhandle, mainly for rainbows, using such nursery streams as Nine Mile to manage spawning and rearing.

Wildlife Lands, here as anywhere in the state, receive a minimum of 'Tending", and it's best that way. As much as possible, the lands owned and controlled by the Game and Parks Commission as wildlife areas are permitted to "go their own way". It was, after all, in their own way that they former ly produced an abundance of wildlife — hills and valleys teeming with buffalo and elk, deer and antelope, waddling porcupines and raccoons, streamlined waterfowl, and all the snakes, and frogs, and eagles, and songbirds that made the Panhandle a living land.

It can never be the same again, "for time moves not backward, nor tarries with yesterday...." Yet, the wildlife lands are places to preserve the valuable things of yesterday —and of today—until maybe tomorrow their value will be better understood and appreciated.

It is said that the "cow and the plow" were the undoing of Indian and buffalo. The harmonious balance of the two kinds of free beings died with the coming of the farmer and rancher and their many tools and new ideas.

The cow and plow are not permitted on wildlife lands —except in special instances. Cultivation is used very sparingly to provide food plots of oats for turkey, and maybe a little alfalfa for deer. A little grazing or prescribed burning may be used someday to prevent vegetation from reaching a climax stage of succession —a stage that might also crowd out wildlife. Pines in the Ridge are a good example. The meadows are covered with tiny seed lings. In time they may take over and crowd out all other plants. The beautiful diversity of the Ridge could suffer then. And, without browse, the deer would go; the small meadow creatures would disappear. The forest would be silent, except for the few creatures that depend solely on pines.

But that's tomorrow, and today, wildlife managers are turning a concerned eye to the possibilities of that tomorrow.

There are 8 Panhandle wildlife areas, encompassing more than 20, 000 acres. Included in those 20,000 acres are a 418-acre, spring-fed Sand Hill lake, a meandering trout nursery stream, a refuge for the massive beasts of yesteryear, and an unequalled hunting area where deer and turkey wander through rough canyons and pine trees.

There are no facilities to speak of, but tomorrow holds promise for those wild animals that are disappearing elsewhere, and for the wild flowers and plants that both support them and add a bit of contrast and color to the lives of men.

A guide to the Panhandle wildlife areas follows. It is in no way complete. It is up to you to make your own guide somewhere in your mind's library where you catalogue the experiences that have made your life a good one.

Smith Lake Wildlife AreaTENSE EXCITEMENT vibrated in the man's voice as he drove along the lake's marshy shore with his son. "There's a pair of pintails back in that little patch of water...I'll back up slow...see 'em? There they go! Did you see 'em?"

Ducks seemed to be everywhere. Spring plumage flashed in brilliant sunlight. The 5,000 or more ducks that had concentrated on Smith Lake were gone, but they had left many lingering pairs behind. Here a couple of pairs of mallards paddled around, there a shoveller or two scrounged snails from the lake-bottom muck, and in another spot a hooded merganser fished for minnows while some blue

The boy was fascinated by a flock of coots. Their improbable-looking bodies and bobbing walk made them a source of amusement between father and son as they had for many generations.

Tramping up a sandy knoll to glass the far shore, the boy nearly stumbled on a nest filled with a half-dozen olive colored eggs. "Probably mallard," his dad commented. Then the boy's attention was quickly diverted elsewhere.

He was pulling a weed. "What's this?" he wanted to know. That answer didn't come easy, so the sample was taken along to check later. But already the boy was on hands and knees, following a leaf-hopper, which led him to the grass. A dried clump of bluestem was shooting up its first new blades....

Suddenly he pointed to the lake. "What's that?" A willet had just landed in the water. "It looks like an Indian warbonnet!" he added. The upstretched wings did indeed flash black-and-white for a moment like the headgear.

Great blue herons and American bitterns, too, slowly work the shore line. A variety of shorebirds and marsh birds use the shallow lake for their insect-grubbing. Avocets stir up the water with long bills, disturbing bottom sediment, then take their pick of the goodies that roil up because of the churning water.

Killdeer and plovers nest in nearby meadows, doing their broken wing act whenever someone approaches too close. Bobolinks and robins and mountain bluebirds use the meadows, trees and hollow cavities for their nurseries.

A grassy knoll might be covered by a flock of yellow-headed blackbirds in the spring, like a crop of sunflower heads resting on the ground. Early on an April morning, sharp-tailed grouse will come a-courting on some hilltop where vegetation is short, while pheasant cocks strut their stuff, replete in their most colorful and iridescent feathers for attracting hens.

Hunters at Smith Lake have their choice of pheasant, grouse, cotton tail, ducks and a few Canada geese, and both mule or white-tailed deer. Trappers will find a good population of muskrats.

Kangaroo rats and deer mice will share grass seed with rabbits and pheasants. Coyotes are attracted to the meadows by the rodents and birds. Several thousand red cedar and pine trees also provide food and cover for birds such as brown thrashers and American goldfinches.

Smith Lake is a fishing lake, too. It was stocked by the Game Commission

The 640 acres of the Smith Lake Wildlife Area includes 418 land and 222 water acres. The lake is bordered all around by wet and dry meadows. Upland prairie and choppy sand dunes in their turn surround the meadows and marshes.

Photographs by Gene Hornbeck"These sandhills, the choppies... you just can't express them. There's nothing like them anywhere in the world... there's the isolation... you stand on top of a dune, feel the wind blowing grass, and you can see for ever. But there's not another person. Maybe there's an antelope miles away, feeding on another dune, but all you hear is silence...it's almost as though you turn into sand, and the grass is your hair. You feel the wind stirring it, and maybe taking away a bit of you, and you're just a grain of sand-light and moving and ethereal -and maybe you drop into a little, hidden lake...."

Photograph by Lou EllA gift provided the original acreage at Smith Lake; then the Pittman Robertson, Dingell-Johnson programs provided 75 percent of the purchase price and the Game Commission supplied the other 25 percent, for another parcel of land.

The gift and subsequent purchases provide a place for learning and observing. Excitement echoes on Smith Lake in a lot of little ways. The voices of two old fishermen on a spring morning echo those of father and son, as one reels in a hefty northern pike. "Bet he'll go five pounds," is the laconic remark that conceals crafty pride.

"Naw," is the kidding reply; "you'll never see a five-pounder!" Humor glints in both men's eyes. They have been fishing adversaries and partners for years....

Pine Ridge Wildlife AreasI DON'T KNOW anything-but I want to learn... I want to hear a wild turkey's gobble echoing across the canyons...I want to know the sun on my back and a horse

Rocky buttes shoulder out of pine

clad hills I ike the craggy-faced soldiers

and settlers who have lived among

them. Their faces and clefts are impassive. On any one of five wildlife

areas among them are the grand and

the common. Bobcats stalk the ridge;

wild turkeys pick up pine seeds that

drop from the cones; rodents rend

the cones for the tenacious remaining

seeds that cling to their shelter. Prairie

golden-peas blow lightly in sunlight

and shade, and delicate pasque

flowers dot the sidehills, peering out

from pine shade.

areas among them are the grand and

the common. Bobcats stalk the ridge;

wild turkeys pick up pine seeds that

drop from the cones; rodents rend

the cones for the tenacious remaining

seeds that cling to their shelter. Prairie

golden-peas blow lightly in sunlight

and shade, and delicate pasque

flowers dot the sidehills, peering out

from pine shade.

"Used to just set here like this and watch the deer come out of the canyons in the evening...mist settles down in the valley there where the farms are....

Photograph by Lou Ell"We planted these oat plots for the turkeys, but I guess they weren't hungry enough .. .they didn't get much use. The bird I got had pine seeds and a couple of pasque flowers in his crop."

Food and cover plots of oats and rye, along with alfalfa, serve to concentrate deer and turkeys. Some timber thinning may be done to provide more open space for shrubs. In a few areas, the dense canopy of pines shades out the shrubs that deer prefer

"We called up a gobbler this morning. Had a nice chance at a shot, but I couldn't get him close enough to get a picture. Guess I got a little excited when I heard him, and moved a bit too fast. They seem to be answering the gobble instead of the hen's squawk now. I sometimes amuse even myself with these toys...."

A turkey call probably wasn't a toy to the settlers who retreated into the Ridge. The remains of their old cabins and corrals give character to meadows on Metcalf, Ponderosa, and Gilbert Baker areas. Ranchers disappeared into the hills with their cattle for months at a time, where they killed an occasional rattlesnake, built fence, branded and helped their cows with calving. Some of them grew big out there; some of them disappeared.

But before the ranchers could raise cattle, the Indian Wars had to be ended. Fort Robinson figured prominently in the close of hostilities, and surrounding canyons and buttes provided overlooks and hideaways for fighting Sioux and Cheyenne. Whispering pines and fragrant needles seem to speak of cold camps and huddled forms hidden among them.

Though man's history has been made in the Pine Ridge, the pines and rocks have a character of their own, formed by the eons of their past. A deposit of sediment on the bottom of an inland sea, the Ridge was slowly thrust above its adjacent land area by forces within the earth's crust that pushed in from the east. Meanwhile, wind and water covered it with silt, sand, clay and volcanic ash from the west, and began the erosion of its own territory. Gradually, wind and water chewed and gouged the land layers, forming canyons and ridges.

Finally, pines moved in among the rocks, and porcupines followed to eat the pine bark. Some say that turkeys were native, too, supporting them selves on pine seed, insects, grasses and other seeds. But the turkeys disappeared, if they were there. The Game and Parks Commission planted Merriam's wild turkeys in 1968, and they have now replaced the lost birds.

Through its past, the Ridge has built a log book of events to be noted. The familiar is repeated each year with inevitable constancy.

"The swallows came into Ponderosa this morning...every year about this time they come flyin' in... swoop around the old nests a few times to kinda look things over....

"Every year there's an ol' turtle

Photographs by Bob Grier Photograph by Lou Ell

Photograph by Lou Ell

dove nests right in that pine tree....

Spring thunderstorms come up quickly in the big country. It's exhilarating to stand squared against a beginning storm and watch thunderheads pile their dark threats atop frowning buttes. The rain begins in huge drops, and anyone off the blacktop roads may curl up for the night to listen to the fury of an angry sky. Natives seem to always have blankets in their vehicles. And in the lightning-flashes, a mule deer is silhouetted against a tiny knoll just above the car...."

In the summer, yucca blooms. Waxey white petals seem to suddenly flut ter away as a white pronuba moth inside the cup moves off. The yucca's cup-like flowers hang upside down on the stalk; pollen cannot travel from one flower to another without the pronubas, which lay their eggs in the flowers and carry pollen from one to another on the brush-like tentacles of their jaws. Young pronubas feed on developing yucca seeds.

Naturalists will find an interspersion of western and eastern birds in the Pine Ridge. Here mountain blue birds, Clark's nutcrackers, pinion jays, gray jays and red crossbills intermingle with such eastern species as broad winged hawks, brown creepers and white-breasted nuthatches.

Golden eagles nest in the rocky crags, soaring above their homes, black against the sky, wheeling over the ridge, seeming to see all, know all. A red-tailed hawk will suddenly stop his soaring wheel to hover over some hapless but unaware chipmunk before plunging toward the grass.

The Pine Ridge wildlife lands are also a mixture of ponderosa pines and broadleaves. Creek bottoms support the more delicate cottonwoods, willows, boxelders and green ash. Deer browse on buckbrush and service berry and chokecherry. Pocket gophers aerate the soil of the grassy meadows, tunneling under smooth stands and chewing off roots. Cascades of wild grape vines enclose some of the trees and shrubs like nets.

Under a gnarled treeroot is a deep pool where trout hide....

"You should see that trout down there! He's laying there in that pool under the bank. And he's hungry... he bit twice for me, but I couldn't

Many yesterdays are gone from the Pine Ridge; many memorable trout and echoing turkey's calls; but to morrows promise crystal pure water to drink and a million things to learn.

"I watched a bumblebee today down on Monroe Creek. He was working over some kind of woody stuff with yellow flowers... Never saw that plant before...."

Photographs by Faye Musil Plant, animal communities are complex. Song birds use fruits which depend on bees or wind for pollination, while bees need the wild blossoms Photograph by Jon Farrar

Wildcat Hills

Photograph by Jon Farrar

Wildcat Hills

YOU GOTTA rope 'em around the horns. A buffalo has a weak windpipe and you can crush it if you jerk him around the neck...."

Where buffalo roam —that's Wildcat Hills Wildlife Area near Gering. There a 385-acre enclosure is home for a herd of some 8 buffalo and about 12 elk. There the Game Commission attempts to preserve a part of Nebras ka's wildlife history.

Millions of buffalo once roamed the plains at will. They were, and are, good-sized critters, with cows aver aging between 800 and 900 pounds and bulls more than double that. The average buffalo is about 5 to 6 feet at the shoulder.

Animals that size pose some problems for managers. Buffalo must be blood tested and branded, and horses are used to do the work. Hence, the roping. But here a difficult art be comes doubly difficult because the target is narrowed from head and neck to the horns on a galloping animal. A roper must be well mounted, too, for despite their tremendous size, buffalo can really move.

Corrals have been built to handle the buffs (again, quite an undertaking because they must be sturdy) and the animals are now only herded into the corrals on horseback.

Elk pose a simpler problem. Tranquilizer drugs make their handling easier. The buffalo are just too big and too resistant to most drugs.

Back when buffalo and elk roamed the plains in vast herds, inbreeding was no problem. But today, with small numbers of animals carefully confined, the herds' health is constantly at stake, resting on breeding stock. Various federal refuges have given surplus animals to the Game Commission—which poses still another problem. How do you transfer a ton buffalo bull from one range to an other?

Buffalo make use of wallowing areas to dust for flies, and they rub on trees, especially when shedding.

Wildcat Hills seems to be a perfect place for buffalo and elk, though. There they are isolated from farms and ranches where they could do a

Small mammals, lizards and turkey vultures share the Hills with the elk and buffalo. White-tailed and mule deer, along with a few wild turkey, range the area. Bobcats, too, wander the Hills, seeking their dinner by night.

Separated from Pine Ridge only by the Platte Valley, part of the same original formation, the Wildcat Hills still wear a different complexion than their cousin, the Ridge. It is drier, less forested, less diverse and smaller. But it's home for small populations of unusual animals that once roamed the state as lords of a vast domain.

An aloof-looking elk steps out of a pine grove, wearing his antlers back like a crown —nose up. This was all his once; all his to wander....

Nine Mile CreekHOW DOES A wild goose know when it's time to fly south? Why does a salmon seek out a special fresh-water river to lay its eggs and die? How do trout choose the same nursery stream they were hatched in to spawn? How do they know what the eggs need to survive? Who taught them to dig their redds, their nests?

None of these questions have complete answers yet and maybe never will, but fisheries biologists know that trout need clean gravel and cold water to reproduce —and the trout seem to know it, too.

Nine Mile Creek Wildlife Area is an attempt to provide the essentials for rainbow trout migrating from Lake McConaughy to spawn. It is the delivery room and nursery for rainbows.

It seems that a spawning trout is a bit like a woman. When her time comes she seeks familiarity —her own

Being hatched in Nine Mile imprints something about the stream on the baby rainbow's "memory". The tiny trout, looking more like minnows than game fish, flash in the sun and disappear whenever anyone approaches too closely.

They feed on microscopic insects from the watercress and gravel —until they are large enough to follow their parents that returned to the lake the last spring. How do they know when to make the journey?

They return when they've grown;

to reproduce themselves. The shiny female digs a redd, deposits a few eggs which the male, his appearance totally altered now, fertilizes. Then the female moves upstream to dig another hollow, at the same time cover ing the first. How does she know the eggs will be safe there? How does she know the movement of water will keep her eggs oxygenated? How does she know the eggs would smother in the still waters of the lake?

It's not enough to set aside a parcel of land with a clear, cold stream running through it and say: "Now the trout are provided for." That stream has to be maintained — protected from bank erosion and siltation.

Game Commission personnel keep a close eye on the trout. Silt might smother eggs, so no cattle are permitted on the area, and bank erosion is carefully controlled with rock riprap. No fishing is permitted on Nine Mile Wildlife Area during the spawning runs, and trout fishing in Lake McConaughy is good because of nursery streams such as Nine Mile.

All kinds of nets are forbidden on Nine Mile and in other Panhandle streams —even landing nets. Unfortunately, they have been used to take an unfair advantage in the past.

Grass and sweet-clover meadows surrounding Nine Mile are a tiny haven for small game, and also for the day's supply of grasshoppers, taken in an early dawn chill when they're still sluggish. Pheasants nest in the cover there, and deer browse the area.

The shade of a willow or elm over hanging the bank provides a sanctuary for trout. A fly fisherman —a purist gracefully arches a line toward the hole, a carefully tied bivisible on the end. Meanwhile, a local kid with a cane pole leans against a tree trunk, munching a candy bar, casually lay ing his pole on the bank for a second, allowing his grasshopper to do all the work. A line jerks taut....

A bubble drifts downstream, reflect ing a rainbow from its curved surface, and lodges on a clump of watercress. Trout flash back and forth over a clean gravel bed. Tomorrow they will be the spawners; the males, shining red, working a hooked, underslung jaw. Tomorrow there will be trout.

Suggested ReferencesGrasslands of the Great Plains, J. E. Weaver and F. W. Albertson, Johnson Publishing Company, Lincoln

Wildflowers of the Northern Plains and Black Hills, Theodore Van Bruggen, Badlands Natural History Association, South Dakota

Handbook of Trees of Nebraska, R. J. Pool, Conservation and Survey Division, University of Nebraska

Taxonomy and Distribution of Nebraska Mammals, J. K. Jones, Univer sity of Kansas Museum of Natural History

Peterson Field Guides, available through most bookstores

This publication is made available through funding supplied by the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act, project W-17-D and by the Nebraska Game and Parks Gommission. Extra copies of "Your Wild life Lands-the Panhandle" can be obtained from the Nebraska Game and Parks Gommission, P.O. Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska.

by Faye Musil

THE NEED FOR WILDLIFE LANDS

WILDLIFE LANDS are an attempt to secure a tomorrow for wild plants and animals, and for the people who find value in them.

In the midst of an increasing land-use problem, managers must project future needs of additional wildlife areas. But the managers cannot make their projections in a vacuum. Increasing world population brings increasing needs for food, living space and resources. All those things put a strain on present land-use patterns. The phrase "everybody has to be somewhere" starts taking on added significance when we project standing-room only.

Within the state and nation, and even the world, wildlife does not win many battles when considered on the economic priority scale. Wildlife managers have long known that a given tract of land could be used primarily for agriculture, yet still produce a good variety and number of game species. They also know that certain tracts can be intensively managed for given game species when the land is devoted primarily to that purpose. Even though publicly owned wildlife lands cannot serve all of the needs for fishing and hunting in Nebraska, it certainly makes sense to add to our wildlife-land owner ship as we can afford and arrange it. It promises with reasonable certainty that some of the land will be held from other uses and devoted to wildlife.

At present, all of the prime lands for agriculture in the state are being used for food production. More of the factors of production are being applied to these lands — water, fertilizer, and so on. Those lands less desirable for agricultural use, sometimes called marginal lands, are being brought into production. Of course, the battle is being waged daily between urban-industrial-highway versus agricultural uses. In this battle, wildlife tends to come in a poor third or fourth. But, to lose some is bearable, if some can be won and preserved into the future for wild life. The same priority scheme that determines that high ways will be built, that housing developments are needed, and that food must be produced, can determine that selected tracts among our hills, plains, valleys and streams shall be preserved for wildlife.

The need for these lands will not diminish, but rather increase. The man or woman whose very being is jangled by waking up to automobile horns and jackhammers will need, literally need, to listen to a cacophony of morning frogs yielding to dawning bird calls, as a simple matter of health. Studies have already shown the relationship of sound levels to tension levels to physical and mental well being or the lack of it.

Over-changed, over-choiced human beings will need ever more frequently to enter a world where change is a matter of biological evolution; where decision-making consists of choosing when to eat the next meal. To provide this escape, river and stream access will be neces sary. To provide marsh habitat, wetlands will be needed.

One of those activities which takes people close to the out-of-doors is hunting. Even though public lands cannot be expected to meet the need for a major portion of public hunting, efforts must be made to add tracts that can be managed to produce maximum game numbers.

Strong need also exists for adding several sizable waterfowl management areas. These would benefit ducks and geese and people; providing public hunting opportunities as well as partial sanctuary and feeding. Certainly the addition of woodlands wherever found is desirable. It is almost a case of any land available having some value for wildlife.

Lands may be acquired by direct acquisition. This would, of course, be accomplished on a willing-seller basis. Or, oftentimes, the Game and Parks Commission may take under long-term license the management of lands for wildlife and recreation purposes from other public entities such as the Bureau of Reclamation or Corps of Engineers; Even quasi-public entities such as public power and irrigation districts may be a source of wildlife lands. This allows and provides for reasonable public use in many instances, while still giving the prime purpose first priority.

Hopefully, citizens of Nebraska will see fit to grant by gift, oftentimes in wills, land for wildlife and public use —this has been done in the past. Some feel that with all the demands for land for food production, housing development, highways and so on, that we cannot afford to set land aside for wildlife. No better statement applies than that "man cannot live by bread alone". Your Game and Parks Commission feels that it must ever seek to provide the public it serves with an opportunity for an out door experience, and fish and wildlife are a necessary part of this experience for many people.

With the land price spiral as a constant problem, a need exists for a ready reserve of funds for acquisition of valuable key tracts when they become available. Certainly legislative agreement would be needed, not only in budgetary terms, but in spirit and intent.

The future of "wildness" is not promising, and wild life lands may be among the very few partial answers to its continued existence.

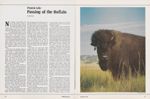

Prairie Life / Passing of the Buffalo

NO ANIMAL EPITOMIZES the life of the prairie as well as the American buffalo. Before the westward migration of the white man, his steel tracks and breech-loading rifles, their numbers tested the most descriptive of writers.

"...I reached some plains so vast that I did not find their limit anywhere that I went...and I found such a quantity of cows (buffalo)...that it is impossible to number them, for while I was journeying through these plains, until I returned to where I first found them, there was not a day that I lost sight of them." That account, written by a Spanish explorer in 1530, is the first written record of the American bison.

Years later, one zoologist, skeptical of such reports of vast herds of buffalo, wrote of his "...slight misgivings in respect to their thorough truthfuIness.'' Later, after traveling extensively on the plains, he reported that buffalo were "numerous as the locusts of Egypt. We could not see their limit either north or west... the plains were black and appeared as if in motion... the country was one robe."

Most estimates of the number of buffalo that once roamed the North American continent are around 60 to 75 million. Some have suggested that there once may have been as many as 125 million but no writer on the subject has estimated the number to be below 50 million buffalo.

To the American Indian, these end less herds of bison were a way of life. One early explorer reported in his log that the buffalo were "the food of the Natives, which drinke the bloud hot, and eate the fat, and often ravine the flesh raw." They were "meat, drink, shoes, houses, fire, vessels and their Master's whole substance."

As long as there were buffalo on the plains, the Indians prospered. So completely did they utilize the buffalo that one observer remarked that nothing but the bellow was discarded. As the Indian braves or squaws, depend ing upon tribal custom, butchered the animals, they often snacked on raw horsd'oeuvresof bison —slices of cold tongue, pieces of liver or even the gristle from the snouts. John James Audubon, after watching several of his Indian guides devour such tidbits with enthusiasm, reported in his journal: "This gluttony excited our curiosity, and being always willing to ascertain the quality of any sort of meat, we tasted some of this sort of tripe, and found it very good, although at first its appearance was rather revolting."

The flesh was used fresh, both cooked and raw, immediately after the hunt. The day of the kill was accompanied by lavish feasts. Some hunters were reported to stay up the entire night and consume several pounds of the choicest cuts. Most of the meat, though, ended up dried. After slicing the meat across the grain, in inch-thick cuts, the Indians would hang them in the sun to dry and mummify on racks made of slender poles. The resulting jerky was the main staple of the plains Indians, often sustaining them for months at a time when the buffalo herds were impossible to find. Some jerky they ground with stones and mixed with grease to make an Indian specialty, pemmican. Occasionally wild berries were mixed in to make a "winter pemmican." Although these additives greatly improved its rather bland taste, it also caused premature spoilage during warm months. Plain pemmican, it was reported, would keep for as long as 30 years and still be as good as the day it was mixed.

Next to the edible portions of the buffalo, the hide or robe was the most important. Over half of an Indian's personal possessions were products of the buffalo's hide, so it is little wonder that they were the measure of individual wealth.

In every Indian culture, the dressing and tanning of the robe was done by the women. Serrate scrapers from the buffalo's leg bone were used to gouge flesh and fat, flint tools to plane the surface to an even thickness, and brains to oil the hide before smoking. Hides taken during the winter months were generally tanned with the hair on for outer garments, and those taken when the buffalo were shedding were stripped of their hair and made into thin, pliable summer clothing. Buffalo skins were also the Indian's "lumber". Depending upon the size of the lodge, as many as 7 to 20 hides went into each family's abode. Green leather, or rawhide, was used for a variety of things, including dippers, cradles, bridles and drumheads.

The remaining parts of the bison were put to good use, too. Hair was used to make earrings and lariats, for insulation in moccasins, and stuffing for children's dolls. Horns, in addition to their ceremonial uses, were fashioned into handles, ladles and boiled to make glue. Bones ended up as saddle frames, war ciubs, pipes and knife handles. Rib bones were used as runners of sleds. As one recent writer said: "The total array made the buffalo a tribal department store, builder's emporium, furniture mart, drugstore, and supermarket rolled into one...."

The complete dependence of plains Indians on the buffalo for their existence was, at least in part, a contributing factor to the fall of both. By the 1870s, the great herds of bison were gone from much of their range. Legislation was introduced in Congress that would have afforded the buffalo some protection. The bill passed the House and Senate and in 1874 reached the desk of President Ulysses S. Grant.

There, under the influence of Secretary of the Interior Columbus Delano, it remained unsigned. Only a year before, Delano had remarked: "I would not seriously regret the total disappearance of the buffalo from our western prairies, in its effect upon the Indians. I would regard it rather as a means of hastening their sense of dependence upon the products of the soil and their own labors." Thus, as a means of crushing the rebellious Indians, the slaughter of the buffalo by tongue and hide hunters, was permitted to run its course without governmental interference.

East of the Mississippi River, the buffalo was nearly exterminated as early as 1830. Most had been shot by early settlers to tide them over until they could till the soil and produce crops for their families and livestock. West of the Mississippi, though, the grasslands were still "covered with an innummerable multitude of buffaloes." By the late 1830s, the future of these buffalo was threatened, too, as hide hunters swarmed onto the plains and returned with wagons stacked above the sideboards with woolly hides. One company alone shipped over 200,000 hides during the 1872-73 season. Another, in addition to its hide shipments, noted that two carloads of nothing but cured tongues were put on the rails, bound for lucrative eastern markets.

It was the railroads, perhaps more than anything else, that made the slaughter of the buffalo possible. When the steel rails severed the Great Plains, the mid-continental herd was broken into smaller north and south herds. Cured tongue and ham became the rage of eastern cuisine, and a new technique for tanning dried buffalo hides into the finest leather was discovered in Germany and found its way back to the United States. The accessibility of rail transportation made possible the connection between the supply in the west and the demand in the east.

Until that time, the hide market had been small and local. Overnight, it boomed. Well equipped caravans of hide hunters streamed out from the cowtown railheads. Buffalo robes brought $1.25 apiece. The number of hides that accumulated at shipping

Those putrefying remains soon turned into a graveyard of bleached skeletons and yet another group of human scavengers, the bonepickers, moved out in long wagon trains. Depending upon the market, buffalo bones would bring as much as $22 per ton or as little as $2.50. Generally it averaged around $8 per ton. As a lot, the bone pickers reaped greater profits from the buffalo than did the hidemen. Tremendous mounds of bones accumulated at railside awaiting shipment east. Weathered bones ended up as fertilizer, and fresh bones were ground and used to purge raw sugar of its brown color, or in the manufacture of the finest bone china. Hooves and horns were aiso salvaged and commanded comparable prices in the manufacture of combs, buttons and glue.

The era of the buffalo was drawing to an end. Except for a few specimens in Texas, the southern herd was gone. In 1875, Kansas and Colorado passed laws affording the buffalo complete protection-two years after their last herds had disappeared.

Until this time, the northern herd had escaped the buffalo hunters, largely because treaties with the plains Indians forbade such activity. The Northern Pacific Railroad, anxious to expand its rails, ignored the treaties and sent surveyors into the new country. Most of that first party never returned, and General George Custer was sent to investigate. In spite of the massacre that followed at Little Big Horn, the new country was opened up within two years and the northern herds then became fair game for hide men.

This was by no means the first time that the herds of Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota and northern Nebraska were subjected to hunting pressure. During the early decades of the 1800s, the traffic in buffalo robes along the Missouri River had been regular. Indians, eager for the white man's tobacco, blankets and trinkets, shipped as many as 80,000 hides a year to markets in St. Louis. When the white hunters moved into the north, though, the slaughter was much like that of the southern herds, perhaps even a bit more efficient. No longer were the shipments made up of tanned hides from the Indians. Unlike the Indians who utilized the buffalo thoroughly, the hide hunters seldom saved more meat from the carcasses than they needed to eat that night. The Sioux City Journal reported the passage of the steamboat C. K. Peck with over 10,000 hides. In just three short years, from 1881 to 1883, the northern herd was virtually eliminated.

In 1886, William Hornaday, chief taxidermist at the U.S. National Museum, organized a party that traveled west into Montana in hopes of securing "presentable specimens". He was unsuccessful in locating a single bison on his first foray. A year later he resumed his search and after eight weeks of combing the plains, follow ing one report of a sighting after an other, he succeeded in collecting 25 buffalo.

In 1907, poachers located and killed a calf, a cow and two bulls in Colorado; the last wild buffalo in North America. During the darkest days, there were probably fewer than 541 living bison on the continent, of which only 300 were free-ranging, and most of these were in Canada. A handful of buffalo had managed to escape the constant pursuit of poachers in Yellowstone Park, and the remainder were held in private herds. By 1900, the bison was gone from the plains and the Congress of the United States was yet to enact legislation that would protect them.

During the first two decades of the 1900s, the American buffalo began making a comeback, largely through the actions of preservation groups like the American Bison Society.

In 1906 the army abandoned its Fort Niobrara Military Reservation near Valentine, Nebraska. A Presidential decree followed, and the entire area was set aside as a refuge for the preservation of native birds. Several years later, members of the American Bison Society visited the area and found it exactly suited for a small herd of buffalo. In 1912, a Nebraska citizen, J. W. Gilbert, donated to the American people his private herd of six bison, and the establishment of the refuge seemed assured. Before the gift could be accepted, however, adequate fencing would be necessary. The citizens of Valentine, the Chicago and Northwestern Railway, and the National Association of Audubon Societies came up with the money, and on January 21, 1913 the buffalo again made its home in Nebraska. Today, there are approximately 300 buffalo at the Fort Niobrara National Wildlife Refuge and over 30,000 in the United States and Canada. In 1930, some surplus animals were moved from the Fort Niobrara herd to the newly purchased Wildcat Hills Recreation Area near Gering. In the spring of 1973, surplus buffalo from the Wildcat Hills herd were used to start a new herd at Fort Robinson State Park near Crawford.