NEBRASKAland

July 1974 50 cents

Speak up

Bridge is FoundSir / When reading "Speak Up" in the May issue of NEBRASKAland, I was interested in the inquiry from Longmont, Colo, about the Nebraska covered bridge, and the fact that the lady's information had come from a Boston newspaper. I am enclosing a notice of the dedication, which took place Sept. 2, 1972, and also a photo of the Ginger Cove area where the bridge is located. You may want to forward this to your Colorado subscriber.

Robert Foster Valley, Nebr.A sincere thanks to Mr. Foster and to several other readers who informed us and our readers of the location of "Nebraska's only covered bridge", which connects Nutmeg Island to the mainland in the Ginger Cover area, a residential park development near Valley. The information has been forwarded to Ms. Haubold. (Editor)

Captive AudienceSir / Ran across your magazine NEBRASKAland and was wondering how to get on your mailing list. I am a native Nebraskan, but in prison here at San Luis Obispo. My home is at Decatur, Nebraska and I am a full-blooded Omaha Indian. Any information you can forward to me will be deeply appreciated.

Samuel Fremont 3-33103 San Luis Obispo, Cal.Due to postal and internal regulations, we are unable to offer free subscriptions. Perhaps a reader out there somewhere might be willing to provide you a copy —or check with the prison library to see if they can subscribe. (Editor)

Things ChangeSir / I went back to my old home state again in November. Although a non-resident for 50 years, each year when I return to Nebraska I see so many interesting changes. The weather this year was beautiful, although the pheasant hunting has been better. Did get to travel over some country in central Nebraska that I had not seen in many years. Beautiful crops... and while hunting in the canyons south of North Platte, noted the great increase in cedar trees. I was told this was not a man made job, but due to birds dropping seeds. Nature will renew herself if given half a chance.

There are some changes that are hard for an old-timer to accept...practical though they may be. I visited a cousin near Paxton. They were about to round up stock from summer range. With great an ticipation...! thought, "gee, maybe I'll get to ride a horse. Well, to my disappointment, they hooked a trailer behind a 4 wheeler and we were off to the range. But horses? No! Out came a couple of motorcycles. I will have to admit they had all the stock in the loading corral in short order. I think the manufacturers of these vehicles are missing an opportunity to stress the therapy treatment in this operation over the prairies. But I hope to be there when a cowpoke can lasso a critter and see that motorcycle lean on the rope while the rider leaps off and takes care of the duties as in past times.

H. C. Latimer Modesto, Cal. Photography ProjectSir / In the May issue of NEBRASKAland, I was interested in the letter from Mrs. Mayle of Long Lane, Mo. who collects pictures of court houses.

Four years ago we decided to take color slides of all 93 county courthouses in Nebraska, and at the same time visit our state, of which we are proud. It was an interesting hobby, but before we got through, it turned out to be a big project.

We noticed an article about Phillip Gardner of Broken Bow, clerk of the district court and secretary of that county's historical society, who had undertaken the same project. We are probably the only ones who hold the distinction of this interesting project.

Mrs. Darrol Baker O'Neill, Nebr. Remembers HuntsSir / I'm 81 years old and my hunting days are over, but I remember with pleasure many good hunts around Emerson, Wayne and other places in that area, so I decided I would renew my subscription. I still get pleasure from reading your wonderful magazine. I pass it along to my two grand sons who are hunting nuts like I used to be. Keep up the high standards you have always followed.

Clarence Peters Pasadena, Cal. List of WinnersSir / I have a suggestion! I would like to see you print a list of the Master Angler fish caught each month, with name of angler, species, weight, location and bait used. I think this would be of much interest to many readers, and be a big help in promoting the Master Angler awards program. Each year I run into many anglers who have caught big fish but knew nothing about the program.

Jim Maxon Kearney, Nebr.Several years ago, we did send out a weekly list of Master Angler winners to newspapers. However, the list became quite lengthy (over 1,600 names last year) and takes considerable time and expense to compile. Marina operators around the state, plus other sources, are now relied upon to inform anglers of the award. Applications are available at permit vendors, from conservation officers and other places, but preparing a list of the winners would now be a very large task. (Editor)

Theater SearchSir / As your wonderful magazine is sent all over the U.S., it might just reach a person I need to contact. I am a UNL Theater major involved in a primary research project on professional theater in Lincoln from the 1880s to 1930s and want to speak with people who were involved with Lincoln Theater during that era. If any actors, musicians, stagehands, attendants, popcorn sellers or audience during those years will contact me, I would appreciate it. Mementos of that era are fading quickly. Before it is all forgotten, please help by remembering.

Carolyn Hull 3023 Arlington Lincoln, Nebr. 68502NEBRASKAland Magazine invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to Speak Up. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters. — Editor.

INDEPENDENCE DAY CITY

Seward has the title and a "hometown" celebration to observe the Fourth in grand tradition. Residents and visitors are treated to fun and frolic, but there are solemn moments, too

Photographs by Lon SlepickaSPEND THE FOURTH in Seward!, stickers plastered around the state say. Anyone who has accepted the invitation to come to this town, 25 miles west of Lincoln, and Nebraska's official Fourth of July City, will tell you that they'll be back. Growing each year, the celebration now attracts nearly 15,000 visitors who nearly quadruple the town's population when they gather for the "hometown" day.

Ask any of the rows of people sitting on the curbs waiting for the parade to pass by, why they came, leaving their patio parties and backyard fireworks in the city. They might have trouble expressing it, but it seems that Nebraska's "Good Life" has been distilled down to its very essence in Seward that day, and you can see in the eyes of visitors, local residents, kids and old folks, that they have each tasted a pleasant sip.

So what is it about such a traditional, patriotic holiday that can involve even today's young people? Ask Paula Blomenberg, 29. A Seward native, she now teaches in Hong Kong, but she made certain that she got home for the Fourth during her vacation last year. Ask Bob Gleisberg, 27, one of the many servicemen who arrange their leaves to get back in July. Or ask any number of Seward's past residents who have moved to residences in other parts of the country, but who are "home" in Seward for the Fourth.

Ask Wendell Rivers, a 1946 graduate of Seward high school and star athlete, who was a prisoner of war in North Viet Nam for seven years. Released in February of 1973, he received a special invitation to bring his family back to Seward where he was honored with the Nebraska's Friend Award and rode on a float in the parade.

Although a special guest, he'd be able to explain a little of what all visitors feel about how the little town opens its arms and makes everyone feel welcome. They find that Seward has the loud fun-making and the bright sights that are part of a Fourth anywhere. The day starts with the art show and flea market in the square. Area artists show their work and take time to show how others, too, can create their own. The flea market has an appeal all its own for those looking for the odd, the old, the unique. Some find enjoyment in watching those who are looking at the wares.

Each year's celebration has its solemn moments, too. Last year the Jaycees asked veterans to help in dedicating war memorials to the men from Seward County who had died. Even the youngsters seemed to feel the impact of the moment.

But the moment passes, and everyone's thoughts turn to the parade which is soon to begin.

Only someone who has lived in a town with a volunteer fire department can understand the excitement as firemen from throughout the area compete on the streets, aiming high-pressure fire hoses at a barrel hung high above. An occasional accidental spray does nothing to dampen the enthusiasm shared by the spectators.

Then the faraway sound of the parade begin, and soon the clowns burst into view showering candy, and kissing unsuspecting onlookers. They are followed by the horses prancing on the cobblestones; the floats full of children and lovely girls; red, white and blue bicycles; and the school bands setting the beat from blocks away for the 200-unit parade.

Wendell Rivers rides by in one of the cars, and in another, a "highjacked" tourist family. Each year the town kidnaps a tourist family off the Interstate and

invites them to Seward to enjoy the events of the day and free meals and motel. Last year the amazed guests were the Husaks and their two girls from Michigan.

Then comes the pet parade! Puppies, raccoons, rabbits, even a skunk, all fancied up and carried down the street by their young owners. Parents watch proudly and agree that this newest attraction of the parade is the most popular — with possibly everyone except the Irish setter at the end who seems to think that his crepe-paper costume is an affront to his pedigree.

The community as a whole feels a deeper pride in the young people who are responsible for the entire celebration. Visitors are always surprised to learn that the day —from recruiting parade entries through the grandstand show in the evening —has always been organized by Seward's young people. Starting several months ahead last year, chairman Kevin Keller came home weekends from college for committee meetings with the 30 different organizations in volved, just as the chairmen before him had done. The local newspaper starts the countdown: "Only 149 days left until the Fourth." Now in its seventh year, the committee has to admit that some of its original members are only "young at heart."

Last year the committee came up with another bit of tradition that it plans to continue at this year's celebration —old fashioned games and contests. Nothing can match the crowd's involvement as Sewardites and guests gobble up as much apple pie as they can (no hands, mind you) as fast as they can, the winner grinning with a genuine apple-cheeked countenance.

The young emcee barks, "Step right up, join the fun," and a new contest begins. This time the crowd watches as contestants "inhale" crackers and spit crumbs at the laughing onlookers, each trying to be the first one to whistle Yankee Doodle. More fun lovers get up their nerve and join a relay, each shuffling across the grass trying to keep a raw egg balanced on a spoon extend ing from their mouths. Or try kicking shoes the farthest. Or racing in a gunny sack.

Although many of the spectators find they have to take short breaks from the strenuous business of games and parade watching to visit the crowded taverns, most everyone waits for the big barbecue in the park. After heaping their plates with baked beans from giant, steaming kettles, and with hot beef sandwiches, families and friends settle down on the park grass to rest up for the evening's show.

Later, the bleachers fill with old friends and new, who show a brand of patriotism in their good-hearted love of their fellow citizens. Rivalries and doubts about their country forgotten, they join in singing of being "crowned with brotherhood."

Then the fireworks! On their side of the fence, the audience watches the 30-minute show, sighing in unison their appreciative "oohs" and "ahs" for a spectacular fluorescent flowering in the sky. Pink spiders with hundreds of legs! Glowing giant mushrooms! The accompanying booms frighten little ones, to their delight, and they snuggle closer in mothers' or fathers' laps.

Parents are genuinely uneasy if there is an unexpected flare at ground level since they know it's a crew of volunteer firemen from Seward who are out there on the other side of the fence, amidst all the showering sparks. The firemen never have let a big company take over the treacherous work of put ting on the fireworks show. The local fellows can personalize it a little, too. Like the "Welcome Wendy" letters that blazed against the night sky last year, delighting P.O.W. guest Wendell Rivers and his friends.

Nobody feels much like a stranger after spending the Fourth in Seward — whether it's a faithful public servant from Seward or someone visiting from Lincoln or Grand Island or even New York. Ask 12-year-old Tammy MacLeod. She stood on the stage with the rest of her "kidnapped" tourist family two years ago, her eyes wide in astonishment as 2,000 "strangers," thousands of miles from her home in New York, sang "happy birthday" to her from the Seward grandstand.

Upper two layers of a stratified lake have enough oxygen to support fish. Decomposition of plant and animal matter in the bottom layer depletes oxygen there, and fish are unable to survive.

Physics and Phish

AT LEAST HALF of the difficulty of catching fish lies in locating the critters. An angler simply must put his bait or lure where the fish are if he's going to be successful — it's as simple as that.

It would seem, then, that anything which concentrated fish, sort of corralled them into a predictable location, would be a boon to anglers and boost their take of fish. The fact is that such a phenomenon is at work each summer on many Nebraska waters. But, many anglers find fishing tougher then than ever, at least partly because they do not understand what is going on beneath the surface.

The phenomenon they're dealing with is stratification, a situation where warm, richly oxygenated layers of 10 water are stacked atop cold, dense, oxygen-deficient water. With this deep water hostile to fish because of the lack of oxygen, nearly all of a stratified lake's fish should be in shallower water where an angler can get at them. Knowing this, a fisherman can confine his efforts to those parts of the lake that support fish.

However, many summertime an glers simply chuck a bait or lure to the deepest part of the lake, reasoning that the fish will be in the coolest, darkest, deepest water available. But often there's no oxygen at those depths, and consequently, no fish.

With just a little understanding of stratification, a summertime fisherman can avoid mistakes like this and improve his chances considerably. But first, he must know if the lake he's fishing is prone to stratification.

It's almost a sure bet if it's a sand or gravel pit. These waters stratify earliest and most markedly. Very seldom is there any dissolved oxygen in a sandpit below 12 feet, and some pits are devoid of oxygen from as little as six feet on down. At the other extreme are natural Sand Hills lakes, which almost never form these layers.

Stratification is also fairly predictable on some other Nebraska waters. Lake McConaughy experiences this phenomenon, as do Merritt, Red Willow, Enders and Medicine Creek reservoirs. On the other hand, Harlan County and Swanson reservoirs stratify very little, and the same is true of waters like Grove and Arnold state lakes. In some waters, like the Salt Valley reservoirs around Lincoln, only small portions of the lake will stratify.

Cause of the phenomenon lies in the physical properties of water. Everyone remembers from his first basic physics class that most forms of matter expand as they get warmer and therefore become less dense than at cooler temperatures. For the most part, this applies to water, too.

As spring progresses and the water at the surface of a lake gets warmer, it also becomes somewhat lighter. Thus, it tends to stay on top of the cooler water below. As spring gives way to summer, this difference in temperature and density becomes more and more pronounced, and the layers are even less prone to mix.

Oxygen is fairly evenly distributed at all depths when the process starts. But, as the layers form, only the warm surface waters are exposed to the air and agitation of the wind, which replenish oxygen supply. More importantly, sunlight penetration promotes the growth of aquatic plants, and their process of photosynthesis yields a good deal of dissolved oxygen.

In the colder, darker waters trapped below, however, none of these things take? place. There's no wind, no exposure to air, and little light to support plant growth. Instead, dead plant and animal matter settles to the bottom, NEBRASKAland where it decomposes, using up what ever oxygen that is there. By the time July arrives, many Nebraska lakes are strongly stratified, and only the upper layers have enough oxygen to support life..

In a typical case, there are three distinct layers of water, and each should mean something special to the fisherman. The uppermost —the warmest and richest in oxygen —is called the epilimnion by scientists. It might be only 6 feet deep in a sandpit, or go down as far as 40 feet in Lake McConaughy. An unmistakable characteristic of the epilimnion is its fairly constant temperature. Usually, water temperature there drops at the rate of about one-half degree per foot of depth. This layer has oxygen, and it has fish.

The thermocline lies next below the epilimnion. It contains less oxygen than water above, but generally has enough to support fish. Its main characteristic is its large variation in temperature. Thermometer readings in the thermocline often drop at the rate of one degree or more per foot.

Below the thermocline is the hypolimnion. This water is almost devoid of oxygen during summer and has an almost uniform temperature, usually in the neighborhood of 54 to 56 degrees. Due to the lack of oxygen, it is definitely not the place to fish.

Temperature readings are the best clue to locating the various levels of stratification. But, before an angler goes to work with the thermometer, a quick check of the bottom profile and a look at the topography around the lake will give him an idea of the presence or degree of stratification he might expect.

Agitation by the wind tends to minimize this phenomenon. Thus, if the banks slope gently both above and below the waterline, and if the surrounding country is fairly level, chances are there will be little stratification. That's why all but the old creek channels of the Salt Valley lakes remain unstratified.

If a lake lies parallel to the direction of prevailing winds, its chances of escaping the layered effect are also increased.

On the other hand, impoundments in deep canyons such as Medicine Creek Reservoir are protected from the wind, and stratification is very pronounced.

Once the rapid fluctuations of the thermometer tell the fisherman the depth of the thermocline, a good fishing strategy can begin to take form. Combining this new information with a bit of knowledge about the fish he seeks should put the fisherman on the right track.

A walleye fisherman, for instance, would know that his quarry likes a clean, hard bottom or a rocky or steep dropoff, and fairly cool water. Know ing the depth of the thermocline, he can avoid all such areas below that level, and concentrate on likely spots in that layer or slightly above.

Trout fishermen at Lake McConaughy know that rainbows spend most of their time in the thermocline because they prefer its cool temperatures. Although the rainbows rise into warmer waters to feed, a trout angler will run his lures by a lot of rainbows if he keeps it in that cool, middle layer.

In sandpits, stratification tends to severely limit possible hangouts for fish. The banks of most of these lakes drop sharply into deep, unoxygenated water. Most of the floor of the lake is well out of reach of fish, being under 40 feet or more of dead water. The only "bottom" available with oxygen bearing water is that close to the shoreline, and this slopes rapidly. Thus, bottom-feeders like catfish will probably do most of their food shop ping close to shore.

Species that are object-oriented, such as largemouth bass, are also easier to pinpoint in sandpits because of stratification. Thedropoffs, trenches, ridges, rocks and other features of bot tom "structure" that attract bass in impoundments, are under dead water in the pit. Thus, submerged tree roots, fallen trees and other debris that collects along the shoreline are about the only features available to bucket mouths, and should therefor be a good place to toss a bass plug.

The same is true for the brushpiles that draw crappie. Those in the middle of the lake will be too deep, so the most productive ones are most likely near shore —usually the only shallow spots in such lakes.

On occasion, stratification may affect fishing in many ways, especially when other factors are involved. A knowing fisherman will keep his eyes open for these things and try to tailor his fishing tactics to fit them.

For example, some irrigation reservoirs are drained from near the bottom, sucking out the oxygen-poor hypolimnion. At first glance, this would not appear to affect fish, since the oxygenated waters of the thermocline and epilimnion are left in the lake. But as the level of the lake is lowered, larvae, nymphs, midges, and other forms of bottom-dwelling organisms are left high and dry. And, none exist on the bottom that was once dead water, even though oxygen bearing water has now dropped to that level.

Some of these "food" organisms can migrate to some extent, but they are extremely vulnerable when thiey leave their bottom hideouts. For this reason, they just might be the main course on the menu of game fish during the summer fishing slump, at least in those lakes which experience such drawdowns. One of these species used as bait, or one that is in short supply, or imitations of either, might be just what it takes to fill a stringer. It is certainly worth a try.

To some anglers, thermoclines and hypolimnions and dissolved oxygen counts seem like just so much scientific mumbo-jumbo to complicate fishing and ruin its simple pleasures. But, science can help the fisherman without blunting his pleasure with cumbersome gadgets and complex calculations. By combining a bit of old-fashioned fishing savvy, some understanding of phenomena such as stratification and a bit of ingenuity, Nebraska anglers can devise tactics to beat the summer "dog days" and have a ball in the process.

HERE WATER meets land is where I want most to be. There the wide-ranging creatures collect to wade and drink and leave their tracks —the coon and deer and mink. Along the shorelines of river and lake, J like to think, windfalls of life wait to be discovered. Here is the dragonfly perched on a broken reed against the dawn water, its wings dew-stressed and sparkling; and the low, rapid flight of a kingfisher, scolding its way upstream.

It is the images of the birds which I remember best; the grace of mallards on calm water, that rare, brief moment of harmony in a confusion of gulls. The mind has the facility to isolate what is important, to remove from the distracting, changing background what the eye recognizes as profound: the lift-off of an egret, perhaps, or a crucial pause in the stalking gait of a heron.

But what is easy for the mind is difficult for the camera to learn. Most such moments are lost. Therefore, you must be patient and persistent. For only the camera can hold these eagles to the sky, forever with us, while the water below slips on and on.

Mallard pair JULY 1974 13

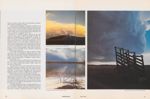

Fire in the Sky

Pretty soon it darkened up, and begun to thunder and lighten; so the birds was right about it Directly it begun to rain, and it rained like all fury, too, and I never see the wind blow so. It was one of these regular summer storms. It would get so dark that it looked all blue-black outside, and lovely; and the rain would thrash along by so thick that the trees off a little ways looked dim and spider webby; and here would come a blast of wind that would bend the trees down and turn up the pale underside of the leaves; and then a perfect ripper of a gust would follow along and set the branches to tossing their arms as if they was just wild; and next, when it was just about the bluest and blackest — fst! it was as bright as glory, and you'd have a little glimpse of treetops a-plunging about away off yonder in the storm, hundreds of yards further than you could see before; dark as sin again in a second, and now you'd hear the thunder let go with an awful crash, and then go rumbling, grumbling, tumbling, down the sky towards the under side of the world, like rolling empty barrels down-stairs where it's long stairs and they bounce a good deal, you know. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain.OF ALL THE natural spectacles which awed and threat ened early man, perhaps none was as frequent and bewildering as the sudden violence of a thunder storm. Thus in the shadow of towering cumulus did dieties come to be born, and in thunderbolts were the judgments of divine wrath delivered.

Even scientific man, who knows better, may find a thin trace of that old fear reflected in some dark corner of his mind when lightning splits the night and clouds begin to speak. Yet, he understands such phenomena as the inevitable conclusion of a predictable chain of events; he knows that one of the

ironies of a stable, natural order is that it demands a frequent,

often violent, reckoning of its forces.

ironies of a stable, natural order is that it demands a frequent,

often violent, reckoning of its forces.

Developing thunderheads vary greatly in appearance. In the semi-arid climate of Nebraska, the billowing up of a huge cumulus cloud can often be observed against a clear blue sky. A large system may boil upwards to 60,000 feet where the upper reaches of the cloud encounter strong winds that carry it away, producing a flattened "anvil" top.

Referred to as "weather factories" because of the wide range and often severe conditions associated with their development, thunderstorms are produced by localized, unstable air masses. Thunderheads begin as cumulus clouds; these clouds signifying a convective overturning in the atmosphere, that is, an air cell which is rising because it is warmer and therefore more buoyant than the air around it. The summer sun beating down on an open field will produce a column of superheated air. If this cell of heated air is large, and if in rising it passes through a deep layer of moist air, conditions will be favorable for this convective overturning to develop into a storm cell.

The average thunderstorm consists of several of these convective cells. Each undergoes a definite life cycle. In the initial stage, strong updrafts move upwards through the cloud. After several minutes of this updraft, in which the rising air is rapidly cooled, precipitation is triggered, creating a down ward movement of air.

When both upward and downward air movements are active, the cell has passed into its mature stage. At this point the cell is highly unstable and produces violent winds, rain and electrical discharges.

The downdraft, at first small and located to one side of the updraft, gradually enlarges and moves across the cell, shutting off the updraft. Now the storm cell rapidly weakens and enters its final stage of dissipation. The rain may end abruptly or continue for hours as light showers, depending on conditions of the air masses in which the cell formed.

Each of the three to five cells within the average thunder storm has a life of about 45 minutes. Since each cell develops independently of the others, there is seldom more than one cell at violent maturity at any one time. When you observe the lessening of lightning activity in one area and an increase elsewhere, you are watching the dissipation of one cell and the maturation of another.

The most spectacular product of the thunderstorm is, of course, lightning. While the causes of lightning are complex, the actual bolt is nothing more than a natural process of equalization between unbalanced electrical charges. The

turbulence of a thunderstorm displaces electrons from air molecules, resulting in a deficit or surplus, thus creating concentrations of negative or positive charge. Lightning is the adjustive mechanism whereby the natural electrical balance is restored.

Of the many identifiable forms of lightning, the ground discharge is the most fascinating, and most dangerous. The expression, "inviting disaster", is literally true for an exposed person during thunderstorm conditions. Since negative and positive charges are mutually attracted, an electrical leader will be "invited" upward from the ground when an oppositely charged leader leaves the cloud. Naturally, this leader will travel upward through the path of least resistance. In open terrain, if there is not a windmill, high hill, tree or any other convenient conductor, a cow or person will suffice.

In open country, the union of these two leaders occurs several feet from the ground. Most ground discharges carry negative electricity from the cloud to earth. Once joined, these relatively weak leaders convey a massive surge of current. Termed a return stroke, this 30,000-amp bolt causes in tense heat (over 53,000° F.) and luminosity.

The flash rate of a cell begins at one or two discharges per minute, increases rapidly to an average of five per minute, and is quickly exhausted. Should the storm develop at high altitude, most electrical exchanges will be from cloud to cloud.

Thunder is produced after the electrical channel displaces air, creating a compression wave. The characteristic rumbling of a distant storm is caused by sound waves reaching an observer from different origin points. Since a bolt may be miles in length, and since sound waves are emitted at every stage of the bolt's development, they do not reach the observer at any one time or from a single source. The commonly observed "heat" lightning of a summer evening is simply a thunder storm in progress at a distance too great for thunder to be heard.

While thunderstorms occur everywhere on earth, they develop most readily along the equator, becoming infrequent beyond the 50° North and South latitudes. In polar regions, conditions are seldom present for thunderstorm propagation.

It has been estimated that at any one moment there are about 1,800 thunderstorms in progress around the earth. Since a mature cell will generate approximately five flashes a minute, we can estimate 150 flashes occurring every second.

As a violent and dramatic natural force, a thunderstorm, like a volcano or an earthquake, can be seen as necessary chaos to maintain established order —a ritual of instability to insure the long-term equilibrium of this changing, yet change less, planet.

The Setting of Seasons

Many factors are involved before gunners go afield. Management of various species is primary criteria

THE LAST OF Nebraska's hunting season regulations finally take shape in mid-August, the apparent result of a public hearing and meeting of the seven-member board of Game and Parks Commissioners.

But while the discussion, testimony and other aspects of this meeting are a necessary part of the process, a whole lot more goes into the making of sound hunting regulations. Through July and into August, biologists are still counting and calculating game populations and considering the probable effect of various combinations of bag limits, shoot ing hours and season lengths.

(Continued on page 45)

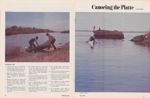

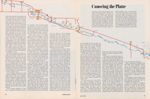

Canoeing the Platte

Photograph by Lou Ell CANOEING TIPS1. Careful planning can eliminate unnecessary weight which can make the difference between pleasure and labor when portaging.

2. Beginners should practice on a lake or pond before attempting a river, or choose an experienced partner.

3. Respect the rights of others and maintain high levels of thought fulness and courtesy. Leave all campsites clean and property undamaged.

4. Know, understand and practice the spirit of the law. Get permission before you camp on private property.

5. Be careful with fire. Use only small fires made from dead, dry wood. Utilize bare earth or sandbars instead of killing vegetation. Drown out all fires thoroughly before leaving.

6. Lash in any item you do not want to lose. Place sleeping bags and extra clothing in plastic bags and tie them shut.

7. Carry a spare paddle. On longer trips, a 100-foot length of strong rope can be useful.

8. Use 10-foot ropes with knots at three-foot intervals, tied on the bow and stern to assist when pulling the canoe.

9. Do not bury trash; carry out all non-biodegradable items in plastic bags.

10. Always wear life jackets, and carry a first-aid and snake-bite kit.

11. Platte River water is safe to drink after five minutes of boiling and/ or after the recommended amount of halozone is added.

12. It is difficult to swim wearing heavy boots or hip waders.

13. Correct weight distribution makes a safer canoe.

14. An inexpensive camp stove is much quicker, cleaner and safer for cooking than an open fire.

THERE ARE many rivers in Nebraska suitable for canoeing, with some easily navigable for only a portion of the year, but the Platte River via the North Platte is the only river to run the entire length of Nebraska —meandering more than 600 miles.

The Platte was an important river in the Midwest even before the westward movement, when the river was relied upon for water and game, and when its adjacent plain made an excellent road for the many settlers passing through Nebraska in the mid-1800s.

The Platte still serves the needs of modern Nebraskans. There are 30 to 40 dams between the Wyoming border and Kearney, used for farmland irrigation, livestock watering, flood control and recreation.

Even though the Platte was termed "unsuitable" for the exploits of Lewis and Clark, it was the river that my partner, Dave Kasl, and I wanted to use because we wanted to traverse the length of the state by canoe —a feat never before recorded. We wanted to leave behind the hurried life in Lincoln, the traffic and the acres of concrete. We wanted to see the soil, water, vegetation and wildlife of Nebraska. And, we would have a chance to test our skills of survival and endurance.

The Platte is not needed now as a highway for westward expansion, but it can still be utilized in developing a spirit of adventure, exploration, self sufficiency and survival through the use of a canoe. The Platte and a canoe can help our youth experience the strength and spirit that were trade marks of the first men to explore west ward and open our country to settlers. The river can humble the canoeist, can teach him a respect for nature, and can foster a sense of co-existence between man and his natural environment which is so needed today.

Known to most Nebraskans as being "a mile wide and an inch deep", the Platte is a sleeping giant that can swell to great dimensions during a wet spring. Usually slow moving, with fingers of water wandering within the sandy-bottomed river bed, the Platte can be transformed into an angry, rampaging river a full mile wide or more in places, flooding the many flatlands surrounding it and leading the amateur canoeist far from the channel through woods and farm lands. The Platte in the spring of 1973 was such a river.

Dave and I began our trans-Nebraska voyage on May 14, 1973 just inside the Wyoming border, west of Henry, Nebraska, and completed our three-week trek at Plattsmouth, Nebraska on June 3.

We felt frustration long before we began our journey when we tried to gather data on the speed of the current, mileage charts, hazards and procedures for dealing with hazards. Much of the information we sought was either unavailable or contradictory. We acknowledge that without information and advice from many men, our trip would have been much more difficult and very possibly disastrous.

Two months were spent collecting gear, researching the river, planning meals and making other preparations, which included attaching a spirited "Iowa or Bust" sign to our canoe.

We chose a 17-foot aluminum canoe with a padded carrying yoke and heavy duty paddles suitable for river travel. As much lightweight gear as possible was selected, including dried food, plastic food containers, a one pound stove, a nylon backpack —almost anything that would reduce weight but maintain quality. In order to further reduce weight, we left food, and stove fuel cached in Grand Island and North Platte at points near the river to be picked up later. We didn't expect to be quite so weather-beaten and bearded when we picked up these supplies, but we were a lot smarter.

Even with careful planning and the information Dave and I accumulated during our preparation, there were hazards that were yet to be discovered. Our lone upset occurred on the first day of our trip, about one mile downstream from Scottsbluff. We had made over 30 miles before mid-after noon, and we momentarily letdown our guard while relaxing. Dave spotted what I at first thought was a fallen tree across the river, and from a distance it appeared as though we could pass safely under. The river began to narrow, increasing our speed. Before we gathered our wits, we realized we could not pass under, and we were too far from shore to avoid what we could now identify as a pipe about a foot in diameter that crossed the river a foot and half above the surface. We clashed with the pipe, and the canoe overturned and was swept out of sight, and we were left clinging to the pipe in 40-degree water. After crawling along the pipe to shore, we ran downstream in knee-deep mud and water through tall willows hoping to catch sight of our canoe. Exhausted after several hundred yards of pursuit and with still no sign of our canoe, we stopped to get our bearings. Extremely disspirited, we trudged through swamp lands, sometimes walking, sometimes swimming until we arrived back at Scottsbluff. We then hired a plane and pilot to search for our lost canoe. We spotted it lodged between two logs on an island, about a half-mile down stream from the pipe. Our pilot returned to the airport, then drove us to the river in his car to try and recover our canoe before nightfall. We shivered uncontrollably while discussing our predicament through chattering teeth, and finally concluded that we were too tired and cold, so we spent the night in a Scottsbluff motel. We returned by taxi to the location the next morning with a loaner paddle, another one that we purchased, and 200 feet of rope. The canoe still remained snug in its unusual perch between the logs on the island.

We sat on the river bank a couple of hours and deliberated on the best way to go about retrieval. We borrowed a saw from the resident of a nearby cabin, and Dave cut an eight foot length from a fallen tree which was to be my temporary craft. We dragged the log to the river's edge where I slowly entered the frigid water trying to accustom myself to it, while the saw's owner pessimistically observed. Astraddle the log at last, I took several deep breaths which, at the time, I sincerely thought might be my last, and struck out across the river. Wearing two life jackets, and paddling frantically first on one side then the other, meanwhile trying to keep the log from rolling, I finally abandoned it after about 60 yards and swam the remaining distance to the snagged canoe. With a little struggling, I freed the canoe with its contents still lashed in, bailed it out, and paddled to the opposite shore to take Dave aboard. Dave had been standing ready with the 200 feet of rope in case I under shot my target or got into trouble. About a mile downstream we spread out all our dripping-wet gear on an island that soon resembled a flea market. While wringing out our sleeping bags, we discussed our procedures for dealing with future hazards.

We were lucky. At least three persons drowned in Nebraska due to boating and canoeing accidents on the Platte during the time that Dave and I were on the river.

For safety on the river, planning is a must. Equipment, supplies and knowledge of the Platte are absolutely necessary for a "successful" trip, whether it be an afternoon of canoeing, a weekend or a trip of greater duration.

Several stretches of river varying in length and difficulty are suitable for canoeing. Personal interest and ability, accessibility, and the season are factors to be considered so that you may choose the adventure best suited to you.

In the spring, the North Platte, South Platte and Platte rivers usually provide sufficient water for canoeing. The South Platte is the least dependable of the three, while the Platte from Columbus downstream to the Missouri River is the most reliable.

The farther west one travels in Nebraska to begin a journey, the more wildlife he will see. Deer and water fowl are more abundant in western Nebraska, particularly in the spring. The North Platte, fed by mountain snow-melt and springs, is a winding river that looks much like a mountain stream. White bass, channel catfish and walleye can be found in the spring and early summer.

There are many diversion dams on the North Platte that are extremely hazardous even for a rugged and experienced canoeist. One should al ways be on the lookout for uncharted or newly constructed diversion dams. There are several methods of locating dams before it is too late. There is usually a roar of water similar to that produced by rapids. The sight of a canal gate (see sketch), catwalk, cement forms or pilings protruding from the water, should stimulate immediate caution. Once the dam is sighted, the canoeist must make a decision very quickly as to which bank to portage. Usually the bank opposite the canal is best because the water there flows much slower than that rushing through the canal, therefore allowing more time to maneuver to the bank. To get the canoe as close as possible to a dam, a 50-foot length of rope can be utilized. One man can hold one end

Photographs by Dale Hausserman

of the rope with the canoe tied to the other, and allow the unmanned craft to drift downstream where his partner can secure it at the bank. In heavy brush where the canoe can't be led along the bank, this procedure is particularly useful, and can be repeated as necessary to minimize portage distance and maximize safety. The spring months through July are best for canoeing on the North Platte. It is sometimes navigable in the fall, though this varies from year to year. For the wildlife enthusiast and bird watcher, an exciting and fulfilling day of activity is in store in far-western Nebraska. The 19 miles from Bridgeport to Broadwater can offer numerous opportunities, especially in the spring, to observe many species of waterfowl, shore birds, cranes, herons, owls, small game, and an occasional turkey vulture, coyote or fox. One's success in encountering wildlife depends on acuteness of senses and quietness in handling his craft.

Between Bridgeport and Broadwater, Dave and I encountered several barbed-wire fences, with only one strand above the water, that we had to either go over or under. Dave made the decision to push the wire under the canoe with his paddle, or to flip it up as we glided under. We used this procedure many times, always in the kneeling position. If time allows, it is advisable to maneuver an unmanned canoe through a fence from shore, and a shore manuever is required for two or more strands of wire.

For the fishing enthusiast or lake canoeist, Nebraska's Lake McConaughy offers a full day's challenge. Walleye, white bass, smallmouth bass, channel catfish, rainbow trout and other species are available from spring through fall. Or, one may choose his own "fishin' spot" and plan a day of relaxing on the lake from a point other than the western reaches of the reservoir.

In the western shallows of Lake Mac, I caught a five-pound carp for our breakfast. After struggling about 30 minutes to clean it, it slipped through my fingers back into the river while I was giving it the final rinse for the frying pan. Dave, half entertained and half-disgusted, began to prepare our usual ration of bacon and eggs.

Three miles across at its widest point, Lake McConaughy could be disastrous for any canoeist unaware of its dangers. Wakes from power boats and winds are the two most dangerous forces on the lake for the ca noeist. The inexperienced should be aware that a canoe can cut through a moderate wave if encountered directly into the bow or stern, but if a wave takes a canoe broadside, it can easily swamp or upset it. If, while navigating to offset the waves created by the wind, the wake from a large power boat should take the canoe broadside, there is real danger. Since storms may come up quickly on the 35,000-acre lake, it is never advisable to venture far from the protection of shore.

To portage Kingsley Dam, the bay at the south end of the dam is most desirable, wind permitting. U.S. high way 61, telephone service, food and supplies are easily accessible from this bay. Dave and I paddled steadily for five and a half hours along the 27 mile length of Big Mac under ideal conditions. Sun-blistered, sore and weary, we slept soundly at the Lake Ogallala State Recreation area which lies just below Kingsley Dam.

Canoeing on Lake Ogallala is quite enjoyable and the water is usually clear. However, the canoeist should not venture near the dam on the east end of the reservoir. Keystone Dam, which retains Lake Ogallala, spans the entire width of the river. As one approaches the dam, it is very difficult to see because of the water flowing over the spillway. The increasing swiftness of the water makes it nearly impossible for the canoeist to ma neuver to shore in time to avoid a 12 to 15-foot drop over the edge. A portage is necessary. Dave and I portaged Keystone Dam and the three small breaker dams below it at the same time for a total of a half-mile of gear lugging. The north bank provides a good path for the portage.

An intriguing day's journey begins at Hershey and ends 18 miles away in North Platte and offers a number of channels from which to choose. Large islands add to the mystery and surprise of the adventure. This section of river requires four to six hours paddling time, and only natural hazards are found, which increases its desirability. The day's-end camp can be made at Cody Park immediately adjacent to the south bank, 100 feet east of the Highway 70 bridge at North Platte.

Between North Platte and Kearney there are several dams that are dangerous and require long, difficult portages. The most notable of these is the Tri-County Dam located two and one half miles downstream from the High way 30 bridge east of North Platte and just below the convergence of the North and South Platte rivers. The dam is 12 to 15 feet high with a high sand bank on the east side reaching upstream about 100 yards. The South Platte converges on the west bank about a quarter-mile above the dam, making it difficult to cross to the west shore where one would have to portage the canal as wel I as the dam, Dave

Hazards are many along the Platte, especially in the western section. Structures are perhaps most dangerous, but fences are most numerous. Major travel restrictions shown on the map are: 1, located between large sandbars near western edge of state, is a diversion dam. Diversion dams are also located at all other numbers on the map with the exceptions of Nufnber 4, which is a large pipe about 1V2 feet above the water surface, and Number 14, which is an electrical fish weir operated by the Game Com mission on the south channels of the river. When portaging a dam, it is usually advisable to go to the opposite side from the canal as the water is slower there, and the canal then needn't be traversed, as well. Pinpointing the hazards is difficult due to lack of permanent landmarks along the river. This map can only give approximate locations, and canoeists must then be prepared for them as they arise. The same is true of fences, which must all be handled individually depending upon the height above water; as to whether to go under, over, around. When near any obstacle, get to nearest shoreand I portaged on the east side, lug ging our canoe over a scorching sand dune. Since the scenery between North Platte and Kearney is very similar to the safer stretches of river up and downstream, this segment is not highly recommended forcanoeing.

During high water, it is hard to stay on the main channel because side-channels are then carrying water, and may lead one to fenced pastures, flooded sandpits or simply nowhere. Large islands can add to the confusion, sometimes offering up to six different channels from which to choose. The rule of thumb that we used was to follow the fast water, choose the largest channel, or avoid the channel near the shore unless one can see that it returns to the river. Even after much practice at this, we spent half of our day from Lexington to Kearney off the main channel. That day we found our selves in pastures, fields, wooded areas, canals-almost anywhere but on the river.

As one moves east on the Platte, the scenery gradually changes in many respects in addition to a steady widening of the river. One does notice an increasing number of towns, bridges, cabins and other signs of civilization. All bridges downstream from Overton to the Missouri River allow plenty of clearance even during flood stage. There is also more opportunity to summon emergency help if needed.

Dave and I encountered some difficulty indirectly due to the widening of the river during what began as a routine day on the stretch from Grand Island to Central City. Rain and cold north winds up to 50 m.p.h. sweeping across the flatlands and open river forced us to paddle hard to even main tain current speed. We covered a meager four miles the first hour and a half, and we were already cold, soaked and miserable. We fought our way to the north shore which gave us some relief from the wind, and by nightfall we had struggled the 37 miles to Central City, but were on the verge of collapse. A local farmer who was parked on the bank fishing from the comfort of his pick-up offered us a ride to town. Needless to say, we eagerly accepted and proceeded to dry-dock our canoe at a motel where we took our first showers since North Platte. Already grateful to the farmer, we became more indebted when he offered to take us the four miles back to the river the next morning.

Many campsites are available along the Platte (with landowner permission), and during summer and fall months many sandbars are suitable for camping. In the spring, potential campsites may be flooded or wet. However, in Eastern Nebraska there are several trips that may be taken where public campgrounds can be utilized.

The stretch of river between Fremont and Plattsmouth may be divided into sections for one-day trips, or combined. The sections are:

Section one: Highway 77 bridge at

Fremont to Two Rivers State Recreation Area, 23 miles, one day. The two

Rivers campground is actually about

nine miles above the convergence of

the Elkhorn and Platte rivers. To locate the campground, one should pass

28

NEBRASKAland

JULY 1974

29

Section two: Two Rivers to Louis ville Lakes State Recreation Area, 25 miles, one day. It is easy to overshoot the Louisville Recreation Area as it is not clearly visible from the river. Therefore, one should stop on the south bank about a mile upstream from the Highway 50 bridge at Louis ville and walk inland about 100 yards to locate a campsite. There is also a daily fee of $1.50 at the Louisville State Recreation Area.

Section three: Louisville Lakes State Recreation Area to Highway 73-75 bridge, 17 miles, one day.

Dave and I made camp at Louis ville where we prepared a large supper

for ourselves and friends from our still-abundant supplies. We were in good spirits as we savored our final evening campfire of the trip. The next morning we rose early to clean up and select our least-dirty clothing for a reception that was planned for us on the banks of the Missouri. We coasted the 20 miles to the Missouri, saving our strength for any unforeseen hazard since neither of us had canoed the Missouri before. When we reached the mouth of the Platte, we sensed a feelingof accomplishment and longed to linger at the spot. We couldn't cherish the moment for long, how ever, because now we were on the Missouri, and we did not intend to "bust" before we reached the Iowa bank. We angled our canoe to the Iowa side where we pulled up on a serene sandbar. We sat in the hot sun and shook sand from our shoes and talked about the many things we had seen and done during the three most memorable weeks of our lives. After an hour, we pushed off for the Nebraska bank where we met our families, friends and news media at a reception organized by Rober Belohavy, our dedicated friend who drove us to Wyoming and kept us constantly informed of outside developments. At that time, we were awarded Admiral ships in the Nebraska Navy by John Rosenow, Director of Nebraska Tour ism, and Wayne Ziebarth, then chair man of the Nebraska Bi-Centennial Commission.

After you whet your appetite on one or more of the trips outlined here, you can begin planning your Trans-Nebraska trip for 1976, the nation's Bi-Centennial year.

Detailed maps for the previously mentioned trips on the Platte, and for other sections of the Platte, may be purchased at the University of Nebraska Geological Survey Depart ment, located on the city campus in Lincoln, Room 113, Nebraska Hall. If you purchase maps, ask the Geological Survey Department for the free Platte River Hazard Check-list.

For specific information on canoe ing the Platte, write to: Canoeing the Platte, Pfeiffer and Kasl, c/o NE BRASKAland Magazine, Box 30370, 2200 North 33rd Street, Lincoln, Ne braska 68503.

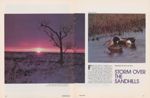

STORM OVER SANDHILLS

FROM THE AIR it is a wedge of grassland hemmed in by a patchwork of floodplain farmland. The converging Platte and Loup rivers form its borders. The circular paths of pivot irrigation systems eat into it from the north. As land goes, it is not especially valuable; most would bring less than $150 per acre. But there is another, far more significant side to this easternmost extension of "sandhills" in North America.

In the spring, when the green crawls up from the lowland meadows, this miniature sandhills is alive with the sounds of wildlife;

not the chatter of fox squirrels or the morning whistle of the bobwhite, sounds common to the neighboring farmland, but the boom of prairie chicken, the assembly call of a brooding teal or the cackling alarm note of nesting burrowing owls, These 12 or so sections of undisturbed native grassland are unique they are a microcosm of the 20,000-square mile Sand Hills region of north-central Nebraska. In its core, one is surrounded by the prairie; emersed in a land where yucca, prickly pear, Indian grass and sand cherry have held silty sands for thousands of years. Perhaps this area's greatest value, though, is its closeness to eastern Nebraska's population centers. It is a miniature Sand Hills within a 100-mile radius of 75 percent of the state's population.

The fall of 1972 was extremely wet and a 3,000-acre area west of this block of sand hills was plagued with fields too wet to farm. Landowners in that area requested assistance, and within a short time initial survey ing, mapping and planning for a drainage project were underway by the Central Platte and Lower Loup Natural Resource Districts. To this point, nothing seemed out of the ordinary. In December of 1973, however, land owners in the sandhill region, some living as far as five miles east of the high-water problem area, received a letter from the Central Platte Natural Resource District. That letter stated in part that: "Within the next 90 days contour mapping should be complete. Design work for the drainage system can begin even before all maps are completed." The same landowners received another letter in January of 1974 that said: "Hopefully, in the spring we will be able to approach you people in the area with a flood control and drainage plan for your consideration".

(Continued on page 48)

chaise lounge TROUT

IN 1968, my husband, Jack, and I found ourselves with the first four days of August open, so we headed for Merritt Reservoir to get in some fishing. We knew success had been slow, but we enjoy the Sand Hills and the Snake River Valley, and they always made a trip worthwhile.

We arrived at the face of the dam in the evening. We always parked at one end and fished off the rocks. As it was late, we only had time to level the camper before bed time. It was hot and humid, and even hotter and "humider" the next morning. Jack got up early and started fishing, but I decided to sleep in as I knew it wouldn't get any cooler.

I finally arose about 9, made break fast, then cleaned the camper. About 11,1 decided to fish. The temperature had reached about 100° by then, and the lake was, as they say, like a piece of glass. Surprisingly, though, trout were jumping up all over. Several old men were fishing from the face of the dam, but no one had caught a fish in quite a spell.

I was still getting my gear together when another camper parked beside us. It was a retired couple from California who had been traveling for about four months.

I like to be comfortable when I fish, so I carry a trusty aluminum lounge chair at all times. I stuck it under my arm, gathered my spinning rod and tackle, and headed for the lake.

The place we were fishing was excellent—the water tapered out about 15 feet then dropped off abruptly. At the last minute, I decided to put on my bathing suit so I'd be cooler, and also to take an umbrella for shade.

So finally, here I come loaded to the hilt with gear. I knew the four old men fishing a short way up the lake had never seen a lounge-chair fisher woman before, by the look of disbelief or disgust on their faces.

I tested the water to see how deep it was, and finally selected a spot that seemed perfect for what I had in mind. I laid my rod down, then carried my lounge chair and umbrella into the water. Now that lounge chair is obstinate. I mean it's one of those creatures that when you finally untangle it and get it all straightened out and set up, it hunches up in the middle. Well, it had taken me a week to master the art of stretching it out by plopping one foot on the middle to hold it down, then giving a little hop to land on it square before it folded up.

I set my chair in about 21/2 feet of water, spread it out, plopped my foot on it and hopped on with a splash. It was sheer delight. The water came about up to my arm pits and was lush and cool! By now those guys had for gotten all about fishing. They were all in a huddle watching and mumbling.

I got up and attached my umbrella on the back of the chair. This takes some doing, what with one foot hold ing down the middle. It took even more doing to duck under the umbrella when I plopped myself into the chair. But, I was settled. Oh no! My gear was still on the bank! Of course, when I got up, the chair folded up and dove under, umbrella and all.

The old guys were in stitches.

I got my spinning rod, tucked it under my arm and returned to the task of getting my lounge chair and umbrella back in shape, plopped my foot in the middle, ducked, and splashed into the chair. Wow, I'm ready! I had rigged up with a small silver spoon, and now I cast out over the dropoff, letting it sink slowly, retrieving in jerks. Zambo! I got a strike. Out of the lounge chair I came, spraddle legged across it. Naturally the darn critter hunched up and hit me on my bottom side, almost knocking me over, then folded up and promptly sank, umbrella upside down full of water. I held tightly to my rod though, and the trout broke water, leaped into the air and came down with a splash. I had him! What a beauty —about 17 inches. You should have seen the old guys then! One fellow went over, pulled in his line, slammed shut his tackle box and left grumbling to himself.

Well, here I go back to the old routine. I emptied the umbrella, spread out the chair, held my rod under my arm, plopped my foot down and splashed in. I'm ready again!

By this time I really had an audience. Jack was about to take up a collection. Everyone had forgotten about fishing. After all, they had a perfect view of the craziest fisherwoman they probably had ever seen, and they were not about to miss anything.

I cast out about four times with no luck, so decided to change my lure. I put on a white doll fly, cast out and wham! Another strike!

I came out of the chair again and up it hunched, hitting me again. This time it accomplished its aim! Down I went, under I went, but holding onto my pole, for I wasn't about to give that fish any slack. I came up sputter ing and spouting, and the chair went down splashing and gurgling. Up came the trout, splashing high in the air; another beauty. I had him. In all the commotion I hadn't lost him.

By now the fellow from California was good-humoredly appalled. He said to Jack: "You know, I've been on the road four months. I've been from California to Florida, from Florida to New Jersey, and from New Jersey to Nebraska, fishing almost everywhere we went. I debated about stopping at Merritt because I had heard it was a new lake and not too great fishing yet. But I tell you, I wouldn't have missed the show your wife put on. By gosh, if she can catch fish in her bathing suit on a lounge chair, I can too".

And, away he went and changed, and even got his chair! Before the morning was over, I had caught four trout, and they were the only four caught on Merritt in four days!

So, if you ever visit Merritt Reservoir and see four old men in bathing suits, reclining in lounge chairs fishing, you'll know why. I think I may have made believers out of them!

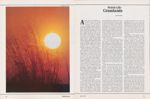

Prairie Life / Grasslands

AS LATE AS the mid-1800s, undisturbed prairie still covered most of North America's heartland. An 1835 entry in Lieutenant Colonel Stephan Kearny's day book noted that his mounted unit often vanished from sight in stands of Indian grass and big bluestem so tall that it could be tied in knots across their saddles. Along the river courses, the stands of grass grew so rank that horsemen were obliged to follow game trails to avoid the saw-edged leaves of the "rip-gut" slough grass. Perhaps the most descriptive account of the windblown prairie came from Nebraska-reared author, Willa Cather, when she wrote: "there was so much motion to it; the whole country seemed, somehow, to be running".

Before John Deere's remarkable plow appeared on the scene, prairie grassland was the most abundant habitat type in North America. Time changed that. The soils are basically the same, but now the cultivated grasses —corn, wheat and sorghum — have supplanted the natives. Only in isolated locations, such as the Nebraska Sand Hills, do remnants of this vast grassland remain. Once this inland sea of grass extended from the Mackenzie River of Canada to the highlands of northern Mexico, from the Wabash River of Indiana to the Rocky Mountains in the west.

This grand sweep of grassland was far from uniform, though. It has been divided into as many as five types or as few as two. Most ecologists agree that there are probably three distinct grassland zones (see map).

The easternmost of these is the tall grass prairie, an area that covers most of Iowa and Illinois, the western half of Minnesota, northwestern Missouri and the eastern edge of the Dakotas, Kansas and Oklahoma. The western edge of the tall-grass prairie thrusts deep into Nebraska, ending roughly at the 100th meridian, a line that passes through Ainsworth and Cozad. As Its name implies, this type is made up of the tall grasses —big bluestem, cordgrass and Indian grass. Where precipitation is 35 inches or more on the prairie, tall grasses are the native vegetation. The Nebraska Sand Hills are an exception to this. Most of north central Nebraska receives less than 30 inches of rain annually, but abundant surface water, fed by a vast under ground aquifer, supports luxuriant stands of tall grasses.

Just west of the tall-grass prairie is a 50 to 100-mile-wide band called the mixed or mid-grass region. Tall and mid grasses claim the moist lowlands, and the more drought resistant short grasses, the arid uplands. Essentially, this is a transition zone between tall and short-grass prairies, and some grassland ecologists question whether it deserves separate consideration or not. Unlike the tall-grass regions, the vegetation cover is spotty and plant composition varies greatly with fluctuations in the annual precipitation. In moist years, the mid grasses prevail; during dry years, short grasses and wildflowers are the dominant soil cover.

South and west of the mixed-grass prairie, in the rain shadow of the Rockies, lies the short-grass plains. This is a land of the sod-forming grasses, the gramas and buffalograss; country too dry to support tall-grass communities but not arid enough to be considered desert. Rainfall is light and infrequent, ranging from 17 inches annually on its eastern margin to as low as 10 inches in the west. The humidity is low, the winds unrelenting and the evaporation rate high. Plants of the short-grass plains are shallow rooted to best utilize infrequent rains. Deep-rooted plants are uncommon since there is a permanent dry zone in the lower soil layers. Some of the mid grasses — switch grass, Canada wildrye and western wheatgrass — manage to hold their own on the wet bottomlands. Just as the plow has destroyed most of the tall grasslands, overgrazing and tilling of the soil for wheat farming have been the ruin of much of the short-grass plains. The dust bowl of the 1930s laid to waste mile upon mile of short-grass sod that had been turned for marginal farming operations.

Regardless of the specific type of grassland being considered, all have certain characters in common —high rates of evaporation, periodic droughts, rolling to flat terrain and animal life made up largely of grazing and burrowing species. An element common to all grasslands is fire, and its role in the grassland ecosystem has been a subject of much speculation.

Almost every authority on grassland ecology agrees that repeated and extensive burning has been part of the prairie for thousands of years. When the first settlers left the eastern forest and ventured out onto the prairie, they thought that the land was just too poor to grow trees. The few who decided to stay invariably made their homes along wooded riverbottoms and cleared timber for their farms, while all around grew luxuriant stands of grasses; grasses not unlike the domestic varieties they hoped to sow.

After years on the prairie, it became clear that the raging infernos that swept through the grasslands, not soil infertility, prevented trees from establishing.

Grasses, unlike trees, die back to ground level each autumn and sprout anew from the soil each spring. Also, grasses grow not from the tips like trees, but from the base, pushing new blades up from the protected soil en vironment. Because of these growth characteristics, grasses were better equipped to recover from the fast moving fires that periodically swept across the prairie, and have thus retained their dominance over the trees.

JULY 1974 39

Lightning has always been a natural source of fire on the prairie. Indians probably accelerated the occurrence of grass fires, accidently by the care less use of camp and signal fires, and intentionally because it aided them in hunting and warfare. Grass fires probably became even more common on the prairies with the first appearance of the white man. But, as more farmers settled in the rich grasslands and turned the sod for their crops, the naked fields, void of combustible material, acted as barriers to the fires that formerly ran unchecked for hundreds of miles. With the absence of fire, woody shrubs and trees began their colonization of the prairie. Photographs of the Platte River in eastern Nebraska, taken at the turn of the century, show a prairie river as early settlers must have first viewed it devoid of trees except for the grass like clumps of willows that choked the sandbars. Today, those same stretches of river are bounded by stands of eastern cottonwoods that tower 70 feet or more; living proof of man's influence on prairie ecology.

This theory of "fire-maintained" prairie left some questions un answered, though. Ecologists began to suspect that there were more factors at work than fire in maintaining the grasslands. It is now suggested that rainfall, or more correctly the absence of it, was the most important factor in the perpetuation of a treeless prairie. Most North American grasslands are mid-continental and lie in the rain shadow of the Rocky Mountains. Pacific fronts are stripped of their moisture-heavy loads by these lofty peaks, so that by the time they reach the prairie, only enough rain to support grasses, not trees, remains.

Other factors affect the amount of moisture available to plants, too. Any one who has lived in a prairie state like Nebraska knows that windless days are few. The constant buffeting that prairie vegetation receives from

Another significant factor attributing to the dominance of grasses on the prairie is their success in crowding out other plants. Grass roots do not merely take hold and grow down; they infiltrate the soil. The top foot of prairie sod is densely packed with roots that absorb every available nutrient and every drop of water that their tissues can hold. Then, too, thick stands of grass block out the light so necessary for other young plants to start their life in the soil.

Within a grassland there are three distinct layers or strata: the herbaceous layer made up of above-ground parts, the ground layer and the root layer.

Ecologists have recognized three additional zones within the herbaceous strata. The lowest of these, just above ground level, is characterized by low light intensity. Plants that grow at this level, such as the wild strawberry or violets, appear early in the season, mature rapidly and spread their seed before the rank growth of grasses blocks off the life-giving sun light. The middle layer is composed of medium-height plants like the cone flower or daisy fleabane, which appear and mature after the low-growing plants but before the taller grasses form a canopy over them. The upper most layer consists of tall grasses and forbs; plants that begin their growth later in the season and do not mature until late summer or fall.

Light intensity is the lowest at ground level, and windflow becomes negligible. It is at this level that great stores of dead vegetation are converted into nutrients availableto living plants. As this natural mulch is pressed into the mineral soil by the weight of vegetation above it and by the passing of animals, actual decomposition begins. Under normal climatic conditions, it may take as long as three or four years for grass leaves to be broken down into nutrients availableto living plants. The amount of mulch that accumulates on the prairie soil is impressive. In one sampling of climax 40 NEBRASKAland prairie, organic material on the surface of the soil amounted to 9,600 pounds per acre.

The real story of the grasslands takes place in the third zone, the root layer. It is here that plants compete for survival. When drought comes to the more moist prairies, it is the plants with the deepest roots that are best able to survive until life-giving rains come. They penetrate deep into the moist reserves of the subsoil where shallow-rooted grasses and forbs can not reach. In arid grasslands, areas where there is no deep subsoil reserve of water, the opposite is the case. Here, plants with shallow, spreading roots, roots that thread their way into every square inch of topsoil, are the most successful in waiting out the dry spells. During the infrequent showers, these sod-forming roots act like sponges to soak up every drop of water that falls, allowing none to percolate into the deep soil layers.

Prairie plants, unlike woodland plants that grow in moist regions, have more tissues invested in roots than in above-ground foliage. Soil scientists estimate that more than half of all plant tissue found on the prairie is hidden beneath the soil. During the winter months, when the surface of the prairie seemingly turns into a graveyard of grasses and forbs, the entire community survives under ground, waiting for the warming temperatures of spring. The bulk of these plant roots go no deeper than the top foot of soil. The roots of buffalograss are found almost entirely in the upper two feet, but some prairie plants, like cordgrass or dotted gayfeather, may extend to depths exceeding 15 feet (see illustration).

As might be expected, these deep rooted plants are quite long lived. Some individual clumps of grasses and perennial forbs live for as long as 50 years. Cross sections of the roots of butterfly weed or gayfeather reveal annual growth rings similar to those found in trees. Narrow rings tell of dry seasons or years when the plant was burned or grazed off, and little growth occurred. Wide rings document years of abundant rainfall when the plants prospered.

To contend with all the perils of the prairie —fires, droughts and hungryRodents and seed-eating birds are also important sowers of the prairie. Neglected caches of seeds, stowed away for winter by jumping mice and kangaroo rats, spring to life with the first rains of the season. Some seeds have impervious coats that help them survive the digestive juices of birds and to return to the soil in a natural bundle of fertilizer.

Some grass seeds lose their viability after just a few months, but others germinate after lying dormant for dozens of dry years. Once a seed falls on a fertile site, it first sends down a root to anchor it against the wind and to draw in the vital moisture that means the difference between life and death on the prairie. From that point on, competition for the elements of life are keen. Few plants that germin ate survive to produce their own seed, and yet the prairie never seems to want for more plants to fill the crowded soil. From this vast store of plant life the myriad types and numbers of animal life draw their sustenance and make their homes; the subject of next month's Prairie Life.

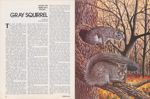

NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA... GRAY SQUIRREL

THE GRAY SQUIRREL is an elusive acrobat of the treetops in southeastern Nebraska. His scientific name, Sciuvus carolinensis, combines the Latin for squirrel, and carolinensis which means "of Carolina," that being the place where this species was first collected.

His home range is closely linked with the eastern hardwood forests, especially oak, hickory and chestnut. They are commonly found in heavily forested bottomlands and big forests of native hardwoods, especially large, relatively unbroken tracts. In general, the gray and fox squirrel prefer the same type of forest, but the gray usually inhabits the dense areas with bushy understory, especially along river bluffs or bottoms. In regions where both species occur, they tend to occupy a separate environment, with fox squirrels in the woodlots and edges and the grays in the deep forest. The two do not generally intermingle.

The modern range of the eastern gray squirrel extends only as far west as eastern Texas, eastern Kansas and Oklahoma, southeast Nebraska and eastern North Dakota. Distribution in Nebraska is limited to the heavily wooded areas along the Missouri River in the southeast corner.

The gray squirrel, as the name implies, is a silver-gray color. It can be distinguished from the fox squirrel by its grayer back, white underparts, white edging of the tail, smaller body size, a more slender facial profile and its ears, which are a bit larger and more pointed.

The average gray squirrel weighs just over a pound. They have an average life span of about 18 months in the wild, with a maximum of six years. In captivity they may live 15 years.

The sexes of gray squirrels are colored alike but the young tend to be grayer than adults. They will appear to be a more silvery-gray in the winter due to slightly longer body fur, and the ears have a projecting fringe of white fur. Black animals may occur in the same litter with gray ones; they may be entirely glossy black or show gradations between black and gray. Albino squirrels occur occasionally, but reddish individuals very rarely.

Compared to most mammals, gray squirrels are very noisy and have an extensive vocabulary. They do most of their calling from the high treetops. One common call is a "chuk-chuk chuk-chuk" given repeatedly and rapidly. This call expresses excitement and is a warning to other squirrels.

Mating takes place in early January. Males are capable of breeding throughout the year but females generally mate only during two periods a year, each about 10 to 14 days duration. The second mating period is in June or July.

Gestation period is 44 or 45 days, and most litters are born in February or March, and July or August. The litter is quite small, with six being maximum and two or three most usual. The female takes entire care of the young. At birth the young are hairless with eyes and ears closed. They do have well developed claws at birth, and weigh in at only about one-half ounce. By the time they are three weeks old, the body is covered with short hair, the lower incisors are appearing and the ears begin to open. The eyes do not open until they are four or five weeks old. At six or seven weeks they emerge from their nest. At eight weeks they are about half grown, fully furred, and have thecharacteristic bushy tail.

Gray squirrels are not seriously plagued by harmful parasites or diseases. Predators, other than man, include dogs, domestic cats, raccoons, owls, hawks, tree-climbing snakes, and occasionally bobcats and coyotes. Predation is of little importance to the success of gray squirrels. They have few young but care fo them well, and adults are strong, shrewd and very agile in their treetop world.