NEBRASKAland

June 1974 50 cents

NEBRASKAland

VOL. 52 / NO. 6 / JUNE 1974 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Fifty cents per copy. Subscription rates $5 for one year, $9 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. commission Chairman: Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-central District, (308) 452-3800 Vice Chairman: James W. McNair, Imperial Southwest District, (308) 882-4425 Second Vice Chairman: Jack D. Obbink, Lincoln Southeast District, (402) 488-3862 Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-central District, (308) 745-1694 Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Director: Willard R. Barbee Assistant Director: William j. Bailey, Jr. Assistant Director: Richard J. Spady Assistant Director: Dale R. Bree staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: Jon Farrar, Ken Bouc, Faye Musil Photography: Greg Beaumont, Bob Grier, Steve O'Hare Layout Design: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1974. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska Travel articles financially supported by Department of Economic Development Ronald J. Mertens, Deputy Director John Rosenow, Travel and Tourism Director Contents FEATURES CAT & MOUSE BASS CORMORANTS POST WITH A PAST AND FUTURE 8 16 OUTDOOR RECREATION SPECIAL 18 BACKPACKING BASICS 35 IRISH DEATH DOG IN THE SAND HILLS 36 PRAIRIE LIFE / SKELETAL ADAPTATIONS 38 NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA / GADWALL 42 DEPARTMENTS SPEAK UP TRADING POST 49 COVER: A common resident of Nebraska, yet one who rarely permits himself to be seen by most people, is the deer. Here, a mule doe poses amidst a Sand Hills creek bottom. OPPOSITE: Another common resi- dent, but one not very highly regarded, is the dandelion —here ready to quietly explode upon the surrounding territory. Photographs by Greg Beaumont.

Speak up

Likes UsSir / As a former Cornhusker, may I express to you how much my family enjoys NEBRASKAland. We have been subscribers for the past seven years and look forward to each issue. Since my wife and I are both teachers, we find the photography and articles invaluable as classroom instructional aides.

I have not seen any periodical that would equal the interest or beauty of your magazine.

Don Stroh Jacksonville, Ore. Doesn't Like Us So MuchSir / We have taken NEBRASKAland for years, but have become quite disappointed in the magazine since you have changed it. We hope you will reconsider your decision, and put back in the column carrying the dates of things to do, and the articles on history and places to go in Nebraska.

After all, many Nebraskans are not avid hunters and fishers, but LOVE the state for its many other advantages, and are proud of our state. You have taken away a great deal from us by leaving out much of these types of articles.

I realize hunting and fishing to many are great sports, but that is not Nebraska's only advantages, and NEBRASKAland should be for ALL Nebraskans. I have saved every NEBRASKAland magazine we have received, and have several published when there were only four a year.

Mrs. Everette Helfiker Mead, Nebr.We have made changes in our format and content at different times, and realize we cannot please everyone. However, we still continue carrying historical stories, and attempt to get in some scenic photos. Our direction has been altered because as an agency, our responsibilities have changed — just as the times keep changing. We are attempting to carry more meaningful material, as such things as overpopulation, pollution and environmental degradation are matters that concern everyone, and to a degree that cannot be ignored. As our major concerns are with outdoor recreation in nearly all its diverse forms, the environment is naturally a prime consideration. I'm certain that our hunting and fishing readers feel we do not carry nearly enough stories of direct interest to them, but we keep trying. We are as proud of Nebraska as anyone, but we also find our selves highly concerned about many things. We want others to be more concerned so that we can all have much more to be proud of. Please bear with us. Editor

Catfish MemoriesSir / Thirty years haven't dimmed my memories of what I regard as the finest cat fishing place in Nebraska. So it was with distress that I noted (in the April issue of NEBRASKAland) that this place was rather loosely referred to as "NW of Genoa" on the Beaver Creek.

Let's be specific. That place is called St. Edward, and some of the best tasting catfish ever to hit the frying pan came from down behind my granddad's barn, and just below the Old Mill, both inside St. Ed's city limits.

Oh, what fond memories.

Dr. Jerry Lightner Washington, D.C.We were not attempting to hide St. Edward's identity under a bushel, and the general directions were given because a longer stretch of the creek could thus be included in a brief reference. We hope the fishing is still as good, and the catfish still as delectable as your memory recalls. Editor

Farmers Pay DoubleSir / The raise in deer and antelope permits turned me a little bit on edge because these animals do more than $15 worth of damage to farmers and ranchers' property, and also eat more than $15 worth of the feed the farmers and ranchers have stored away for other purposes. Farmers provide all of the food for these animals and get nothing in return, and also have to pay the same amount to hunt as everybody else, I also think there should be some female only permits issued and that a few more 1 does should be taken.

I hope this letter gets published in your Speak Up column as I feel many others feel the same way as I do.

Ronald Cox Purdum, Nebr.

CAT & MOUSE BASS

Knowing how to bait a wise tabby is often just the ticket for landing largemouths

IT MAY SOUND strange, but I've probably learned more about catching big bass by playing with a house cat than from anything else! It all started years ago when the family raised a cute little kitten into a big old tomcat.

Now when he was little, "Blackie" as we called him, had a favorite toy mouse. We would tie it onto the end of a string and have hours of entertainment watching that little guy tear into his simulated game. It was great sport for us and the kitten.

But, when "Blackie" grew into an adult tomcat, he frequently had his mind on other things such as catching real mice, attacking neighborhood dogs, or resting after a night out courting lady cats. Although he slept with one eye open, as the saying goes, to get him interested in playing with his artificial mouse after he was fully grown required altogether different tactics than it did when he was a kitten.

For one thing, if he was lying around in the center of a room, I could pull that mouse by right under his nose and he would hardly give it a second glance. At first we thought it was just because he was older and wiser and knew the mouse was a phony, but then I discovered there were other things that contributed to his lack of interest. First of all, he could see me, string in hand, and he was really more in terested in my actions than those of the mouse. Then too, he was right out in the middle of the room, not hidden beside the couch or up on the arm of a chair where his attack would be more like a real live mouse ambush.

In any event, I found a couple of approaches that were always necessary before I could get him to play. First, I had to keep myself pretty well hidden around a corner or behind a doorway so that he would give full attention to the "lure". Secondly, he also had to be partially concealed somewhere, apparently so that he felt the toy mouse couldn't "see" him. Then, most of the time he would come out of his hiding spot and pounce on the mouse, but there were still times when he would completely ignore it. Through such trial and error, I finally learned a method that nearly always worked for getting action out of the cat —we both still had to be largely hidden, and then I would toss the mouse out near him and simply let it lay.

He'd eye it, but not make a move. Then I'd jerk the string just enough to make the mouse wiggle. Old Tom would crouch down and lay his ears back. I would let the mouse lay perfectly still once again. Tom's tail would start to twitch. One more little jerk, and WHAM! The cat would be all over that rubber mouse, biting and kicking and throwing it around!

Now, the cat knew perfectly well that thing was not a real mouse, but there was something about the way it was presented to him that made it irresistible. It was almost as if something inborn forced him to go after that thing on the string.

But, you ask, what's all this cat-and-mouse business got to do with bass fishing? Well, it took me quite a few years before I had sense enough to apply those same cat-teasing tactics to catching fish, but once I did, it has been a rare day when I can't catch large or smallmouth bass on artificial lures!

With "kitten" bass, those little six to eight inchers, if you locate where they're working in a lake, there's generally no problem in catching them using almost any method. It's those adult bucketmouths that usually give the trouble, but if you'll apply the "cat-and-mouse" technique, you'll score much more regularly, I'm sure.

Of course, there are a lot of variables such as water depth, temperature, vegetation, clarity of water, wind and weather conditions, and most of all, the bass population of the lake you're fishing. No body is going to catch bass in a lake where there are few or no catchable-size fish. Fortunately, nearly all sandpits and 1-80 lakes in Nebraska have good fish populations. The other side of the coin is that they are also among the most difficult to catch fish from because of the clear water and lack of natural, under water obstructions —fish habitat.

Particularly if you really enjoy the sport of fishing top-water lures, there are three major ingredients to success. First, keep yourself out of sight of the fish as much as possible. This means avoiding casting from high banks where you present a very clear out line of yourself. Generally, (Continued on page 44)

CORMORANTS

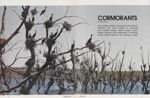

Long necked, somber in appearance and unloved, America's only inland species of cormorant finds suitable nesting habitat acutely scarce. Sizable rookeries have disappeared in midwest, making Merritt Reservoir tree sanctuary unique 8 NEBRASKAland JUNE 1974

MOST OF THE world's thirty species of cormorants have a sorry history of persecution by man. Perhaps because of its sinister, reptilian appearance on the one hand and its awkward, sometimes clown like actions on land, the cormorant in Europe and America has never enjoyed a popular sentiment. Often called "crows of the sea," they are certainly not endearing creatures; a large rookery presents a vile smelling uproar of croakings, tics, gargling noises, and very realistic vomit sounds. Because the cormorant is an efficient fish-getter, fishermen have long regarded it with suspicion; also it has the bad habit of becoming ensnared in commercial fishermen's nets while attempting to raid the resulting concentrations of fish. And since the bird is strictly a communal nester, preferring to colonize a promontory or island, man's revenge is often simple and complete.

Of the many species of cormorants, only the double-crested, Phalacrocorax auritus frequents the inland continental United States and Canada. Overt persecution and the disappearance of suitable nesting habitat have greatly reduced the numbers of this species; a 1928 estimate totaled only about 70,000 individuals. (Continued on page 15)

14

14

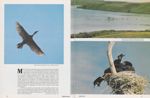

Among the few rookeries found in Nebraska, the most conspicuous and easily approached (by boat) is located at Merritt Reservoir in Cherry County. Near the south shore midway on the long, central arm of the reservoir stands a line of flooded trees. Almost every crotch and limb holds a nest.

If suitable ground nesting sites are not available, these birds are quick to appropriate trees, even though this makes life more difficult for them since they are not well adapted for perching or landing in trees; as a result, many attempts are sometimes required to effect a successful landing.

Wintering in the lower Mississippi River Valley and the Gulf and At lantic coasts (efficient salt glands allow double-crested cormorants to feed on salt-water fish as well as their preferred freshwater prey), the birds begin their northward migration in March. Arriving at the rookery sometime in April or early May, the males select a territory, which, in the case of a tree site, includes a nest and whatever defendable space may surround it. From there, they woo passing females with their "songs".

When a female is sufficiently enchanted by her suitor's grunts and croaks and serpentine neck display, she responds with a similar weaving of the neck, and accepts occupancy of the nest. The birds then set about the business of rebuilding the nest to make it fit for another season's use.

Incubation of the three to five-egg clutch, four being the average number, begins before the final egg is laid, resulting in nests containing young of varying stages of development. The chicks at hatching are blind, helpless, and naked. After about four days they can lift their heads. By two weeks they are active and alert and almost completely covered with a coat of black down, which falls out or is plucked by the chicks when feathers appear.

Dutiful parents, cormorants feed their young by regurgitating partially digested fish. At the approach of a parent, the young birds make a great outcry and engage in a begging contest to determine which chick will be allowed to feed first, the winner thrusting its head into the adult's mouth for the waiting feast.

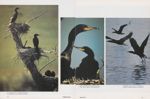

Although they are strong fliers and excellent swimmers, cormorants walk poorly and take to the air laboriously. When taking off from the water they are obliged to run a considerable distance over the surface before gaining sufficient lift. In jumping off a low perch, they lose altitude before their wings "take," often touching water with their wing-tips and giving rise to the popular notion that a cormorant must get its tail wet before it can fly.

Another difficulty cormorants face is a striking maladaption for a species of bird which must secure its food from the water— its feathers are so poorly protected against wetting that the bird becomes soaked and must dry its feathers after each plunge. This unfortunate condition is responsible for the often-observed spectacle of the birds standing with wings spread wide, a rather bedraggled imitation of the heroic eagle pose.

Making use of its excellent vision, a cormorant will swim on the surface of the water with head submerged, searching for fish. In diving, it kicks up a jet of spray with its powerful legs. When chasing down a fish, the bird relies on its feet for propulsion, kicking them in unison, and keeping its wings closed. Out-swimming most fish with ease, it reaches out to grasp its prey with its powerful, hooked bill. Having made a catch, it surfaces to position the fish for swallowing. Unless the fish is small or eel-like, it will always swallow its prey head first to take advantage of the fish's stream lining and avoid erected spines.

After the young gain flight at eight weeks, the colony begins to disperse. Some individuals will begin a leisurely migration southward in August; others wait out the season and leave just before the lakes freeze.

During September and October, when the geese begin their noisy flights south, the sky will also bear lines and chevrons of black crosses, high, swift and utterly silent. Unlike the geese, these flights suggest a certain hopelessness. Inevitably the storms and ice of winter will bring down a few more of those old skeleton trees at Merritt Reservoir, a small but perhaps important loss to the dwindling shadow of double-crested cormorants.

Post with a Past ... and Future

Steeped in history and nestled among some of the midwest's most glorious scenery, this former military post is destined to become the grandest of state's parks

FORT ROBINSON...the outstanding state park in the northern plains region— That statement is not exactly an accomplished fact today. But, it could be an accurate one in a few years, if the areas's obvious state park, historic, and outdoor recreation potential is carefully preserved.

Few places in the West offer a background as historic and colorful as does Fort Robinson. Its troops fought in the same campaign that led to the Custer Massacre. The Sioux war chief, Crazy Horse, was killed there, and the Cheyennes fought and died for freedom on the post and in the surrounding hills.

With the Indian Wars over, the frontier post continued as a military installation, sending cavalrymen to the Spanish-American War, serving as a remount station after World War I and functioning as a war-dog training center and prisoner-of-war camp during World War II. And all of these historic events took place in one of the most beautiful settings on the plains-the buttes, forested hills and grasslands of the Nebraska Pine Ridge.

To make the most of anything requires careful planning. And, a comprehensive plan of action is absolutely imperative when working with something as irreplaceable as the places and things that link us with a colorful history.

You just don't rush in and start building thoroughfares to historic sites. You might bury more history under asphalt roads and parking lots than you would preserve. And, it would make little sense to restore buildings of the main post area and install museums and displays, if the area were disrupted by the noisy and hazardous traffic of a major highway cutting the post in two. Nor would it make sense to lure travelers several hundred miles, then offer them only one or two types of recreation. Most vacationers like a little variety and action along with their history and scenery, and a top-rate park would offer this to them.

The Game and Parks Commission has long realized Fort Robinson's potential, and has also been aware of the complex factors involved in fully developing that potential. That's why the agency aggressively pursued acquisition of the area and commissioned a renowned expert on recreation planning, Dr. Arthur Wilcox of Colorado State University, to make an extensive study of Fort Robinson. And that's why the Commissioners endorsed his recommendations, now known as the "Wilcox Plan", this past February.

At best, development of the fort according to the Wilcox Plan is at least 10 years and perhaps some $10 million away, depending on legislative funding. But, when completed, Fort Robinson will be what recreation planners call a "resort park". This simply means that attractions at Fort Robinson will be attractive and varied enough to warrant a stay of several days to two weeks, rather than just day-use or over night stays.

The bulk of attractions will still center around the park history and the outdoors, the fort's major assets. This will mean more and better accommodations, camping facilities, hiking trails, museums and interpretive centers. Natural environment areas, backcountry camp grounds, scenic corridors, horse and jeep trails and scenic lookouts will be improved.

If the plan is followed, Fort Robinson will also boast a golf course, field archery range, swimming pool, (Continued on page 46)

Outdoor Recreation in Nebraska

Photograph by Greg BeaumontBarring love and war, few enterprises are undertaken with such abandon, or by such diverse individuals, or with so paradoxical a mixture of appetite and altruism, as that group of avocations known as outdoor recreation. It is, by common consent, a good thing for people to get back to nature. But wherein lies the goodness, and what can be done to encourage its pursuit? On these questions there is confusion of counsel, and only the most uncritical minds are free from doubt.

Public policies for outdoor recreation are controversial. Equally conscientious citizens hold opposite views on what it is and what should be done to conserve its resource-base. Thus the Wilderness Society seeks to exclude roads from the hinterlands, and the Chamber of Commerce to extend them, both in the name of recreation. Such factions commonly label each other with short and ugly names, when, in fact, each is considering a different component of the recreational process.

Aldo Leopold A Sand County Almanac 18 NEBRASKAland Photograph by Greg Beaumont

Photograph by Greg Beaumont

RECREATION is big business. In 1972 alone, tourists spent over $236 million for camping, fishing, sightseeing and other outdoor diversions in Nebraska. That figure alone is indicative of Americans' preoccupation with getting the most out of their leisure hours. Out door recreation has become an integral part of the lifestyle of Americans, and, Nebraskans are no exception. Fuel shortages may change those off hour habits somewhat, but outdoor recreation will undoubtedly continue to increase with climbing incomes and shorter work weeks. We may, though, be spending more of our long week ends and vacations closer to home in upcoming years. If Nebraska is to meet existing and expected demands, long-range, statewide planning is mandatory. This is where the State Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP) comes into the picture.

Since 1965, the Federal Bureau of Outdoor Recreation, a branch of the Department of Interior, has provided grants-in-aid to state and local governments, from the Land and Water Conservation Fund program. This program, administered in Nebraska by the Game and Parks Commission, provides money for 50 percent of the cost of acquiring and developing out door recreation areas and facilities. Nebraska receives about $2,000,000 annually under this program, of which 60 percent goes to cities and counties, and 40 percent to the State for acquisition and development. State funds provide another $600,000 an nually into this outdoor recreation coffer. To be eligible for this program, a state must prepare and maintain a comprehensiveoutdoor recreation plan to assess recreation demands and supplies, to point up areas of critical deficiencies and to insure that the highest priority programs will be implemented first.

Nebraska's first comprehensive out door recreation plan was formulated in 1965, with revisions completed in 1968 and again in 1973. The list of projects partially financed under this project since 1965 is both diverse and extensive; swimming pools, ball fields, tennis courts, shelter houses, picnic facilities, golf courses, camp grounds, trap ranges and hunting, fishing and nature areas, just to cite a few. While the amount of money allocated annually may seem large, the demands for that money are even larger. Because there are so many hands reaching for the same dollars, it is mandatory that orderly plans to best meet priority recreational needs of the people of Nebraska be implemented. This is the purpose of SCORP — to determine the current supplies of recreational facilities, the current and projected demands for these facilities, and to recommend the proper actions to alleviate shortages.

Fundamental to the implementation of any plan is the necessity for establishing firm goals and objectives at the outset of the planning effort. All who are involved or have an impact on outdoor recreation management in the state must know which direction we're going and which policies and precepts will guide us along the route. A Technical Advisory Committee (TAC) under the chairmanship of the State Office of Planning and Program ming, was established to provide concerned agencies and interests with the opportunity to review and comment on all sections of SCORP, including the goals and objectives. Over 20 agencies or special-interest groups serve on TAC.

For general outdoor recreation, four major objectives have been delineated in SCORP and approved by TAC:

(1)To develop a balanced state park system by providing non-urban park areas for the inspiration, recreation and enjoyment primarily of resident populations; wayside parks for picnic areas or rest stops to accommodate the traveling public; and historic parks to offer representative interpretation of the rich Nebraska historical heritage for the education and enjoyment of Nebraskans and visitors to the state.

(2) To manage and preserve those public areas which are primarily of value for wildlife habitat, public hunting or fishing, and with natural or scenic features unique to a region.

(3) To enhance the quality of life and physical environment in Nebraska by encouraging the development of adequate out door recreation opportunities by political subdivisions to meet primarily identified regional, county, municipal or local needs through funding assistance from the Land and Water Conservation Fund Program.

(4) To encourage the development of improved parks and recreational facilities and programs through inter-local cooperation involving municipalities, counties, school districts and other relevant governmental units.

Since the Game and Parks Commission

Outdoor Recreation planning for future needs

is the agency administering the Land and Water Conservation fund and bears the responsibility for a wide range of outdoor recreation and resource management, its purpose and objectives as outlined in 1973 are also reflected in SCORP planning. The overall purpose of the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, as out lined in that report, is the "Husbandry of the state's wildlife, park and out door recreation resources in the best long-term interests of the people".

Within the guidelines of this over all purpose are specific goals toward which all agency efforts will be directed: (1) to plan for and implement all policies and programs in an efficient and objective manner, (2) to main tain a rich and diverse environment in the lands and waters of Nebraska, (3) to provide outdoor recreation opportunities, (4) to manage wildlife resources for maximum benefit of the people, and (5) to cultivate man's appreciation of his role in the world of nature.

Nebraska is a large, diverse state the eastern half supporting a relatively dense population, the western half only sparse populations; the southwest with many reservoirs, the northeast with few; the northwest with many acres of public land, the south east relatively poverty stricken in its supply of public land; the west devoted to beef and wheat production, and the east to more intensive agriculture. To best analyze each section's problems and assess current and future needs, SCORP planners divided the state into seven regions.

Region One is a four-county area including the Omaha metropolitan area and is characterized by high population and resultant deficiencies in outdoor recreation resources and facilities. In contrast, Region Seven is a sparsely populated region dominated by sandhill ranchlands. It covers the most land area but has the lowest population. The other five regions range between these two extremes in population density and resource availability. One of Nebraska's major recreational dilemmas be comes obvious —the four eastern regions have three-fourths of the state's population, the three western regions have 85 percent of the non-urban recreation lands. Or stated simply, the recreators are in the east, the recreation areas are in the west. To recommend and assist in imple menting programs to correct or at least minimize this disparity and many others like it, became one of the major roles of the State Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan.

Certain preliminary surveys and data bases are required prior to any actual planning. Planners had to determine existing supplies of federal, state and local outdoor recreation resources. Over 500 Nebraska cities, towns and villages were polled, along with those state and federal agencies which owned or administered lands available for outdoor recreation.

A survey mailed to 16,000 Ne braska households, and a follow-up telephone survey to some 500 house holds, served to determine current outdoor recreation participation rates and patterns. Existing use levels were linked to predictable socio-economic projections to arrive at expected 1990 levels of participation.

Having determined existing supplies, and both current and projected demands, planners were in a position to pinpoint and quantify many of the land and facility deficiencies across the state. Established guidelines of desirable levels of land and facilities per capita were related to the situation in Nebraska communities, and planning regions and deficiencies were thereby identified.

Also presented in SCORP were several recommendations for actions needed to overcome these deficiencies. Presented on the following pages are some of the findings.

Photograph by Lou Ell Photograph by Steve O'Hare

Photograph by Greg Beaumont

Photograph by Steve O'Hare

Photograph by Greg Beaumont

VOLUMES HAVE been written in attempts to describe and predict those factors which affect the demand for outdoor recreation. Anyone who has been us ing parks for several years can attest to the fact that visitation is up and use patterns are changing. State and federal agencies concerned with recreation have noticed these changes too. That is one reason that comprehensive outdoor plans such as SCORP exist. They have realized that sound planning was an absolute necessity if we hope to catch up to, and then keep pace with, these ever-increasing and changing recreational demands.

A fact of life in our state and in the nation as a whole is that populations are becoming more concentrated in urban areas. These urban dwellers have more leisure time, which compounds the demand for outdoor recreation facilities. Then, too, surveys show that the recreational tastes of urban dwellers are quite different than those of rural Nebraskans.

This disparity of outdoor recreation al interest coupled with the uneven distribution of Nebraska's natural resources and recreational facilities made it advisable for recreation planners to deal with the state region by region. This system permits planning for specific demands and shortages, area by area, rather than shotgunning proposals that would work for some regions and fail for others.

Omaha dominates Region I. No survey was needed to verify that the recreational demands of this area generally surpass existing supplies. This four-county region occupies about 2 percent of the state but contains about 34 percent of its total population. Because of this concentration of people in such a small area, there are definite needs for additional facilities.

The most critical need in Region I is for additional boating and fishing

Outdoor Recreation the supply the demandfacilities. Today there is an estimated deficiency of 18,000 acres of water suitable for fishing, skiing and power boating. The Papillion Creek Water shed reservoirs, now under construction, will relieve some of this pressure but must not be viewed as a cure-all for recreational shortages. When completed, this project will provide 20 lakes totaling some 4,000 surface acres suitable for water-based recreation. Some will be too small for power boating and skiing but will provide needed areas for fishing.

Much of Region I's current recreational demands are being met outside of its four-county area. Planners anticipate that the Papio project may change this use pattern somewhat, but it will never be possible to meet the demands of such a large number of people in such a restricted area.

Recommendations for the establishment of a major non-urban park between Lincoln and Omaha were also presented in the 1973 SCORP plan. This, it is suggested, would go a long way toward meeting the recreational needs of eastern Nebraska.

Region II is made up of 17 south eastern counties. It contains approximately 3.5 percent of the state's public lands and 24 percent of its population. Lincoln is the region's population center. This region's recreational shortages are similar to those of Region I but not nearly as severe.

The 1973 SCORP plan indicates

that the greatest deficiencies for recreation in Region II are for lakes suitable

for power boating, skiing and fishing.

Even though the Salt Valley Lakes provide over 4,400 surface acres, the de

mand still exceeds the supply. Part of

the reason for Region IPs shortage is

explained by the large number of

Omaha boaters and fishermen that

use the Salt Valley Lakes. The need

for additional rural parklands, municipal parklands and picnicking areas

also exists in Region II.

that the greatest deficiencies for recreation in Region II are for lakes suitable

for power boating, skiing and fishing.

Even though the Salt Valley Lakes provide over 4,400 surface acres, the de

mand still exceeds the supply. Part of

the reason for Region IPs shortage is

explained by the large number of

Omaha boaters and fishermen that

use the Salt Valley Lakes. The need

for additional rural parklands, municipal parklands and picnicking areas

also exists in Region II.

Region III is composed of 16 northeastern counties and could be char acterized as a transition zone from intensive cropping and feedlot operations to ranch and grazing lands. About 12 percent of the state's population resides here with 2.5 percent of the supply of non-urban public recreation lands. The recreational problems here are similar to those of Regions I and II and characterize the situation in eastern Nebraska as a whole —the bulk of the population with easy access to only a small percentage of the public recreation lands. The great est recreational deficiencies in Region III are for rural and municipal park lands. Additional camping areas are needed on these parklands to meet current demands.

Region III does have the potential for satisfying some of the recreation demand from the Omaha area. The Missouri River blufflands are not suited for intensive agriculture but do provide a wide range of recreational opportunities. The Omaha, Winnebago and Santee Indian reservations in Thurston and Knox counties occupy relatively large natural areas and would be well suited for some recreational development. Facilities in these areas would not only meet some of the needs of eastern Nebraska but could also bolster the economy.

Lewis and Clark Reservoir and the Missouri River provide enough water to meet the current and projected needs for power boating and water skiing in this region. And, if surface acres were the only standard, Lewis and Clark Reservoir would easily satisfy the region's lake fishing needs. Lewis and Clark, though, is a rather poor fishery, largely because of the rapid turnover rate of its water. As such, it does not provide the attraction for fishermen that might be expected. Accessibility is also a problem since the reservoir lies at a con siderable distance from population concentration.

The Devil's Nest development on Lewis and Clark Reservoir, when completed, will provide a wide range of recreational opportunities including golf, tennis, horseback riding, snow skiing and marina facilities for this area.

Planning Region IV includes much of south-central Nebraska. It is a 14 county region, most of which is under intent cultivation. It contains about 12 percent of the state's population and 6 percent of its non-urban public recreational land. Grand Island, Hastings and Kearney are this region's population centers. All are showing steady growth.

The supply of rural parklands is currently adequate to meet the demands of this region. Federal and state owned rainwater basins offer some 10,000 acres of wetland for consumptive and nonconsumptive use. Harlan County Reservoir provides an additional 30,000 acres of land and water within easy driving distance of the population centers. The greatest needs in Region IV are for municipal park lands and facilities such as golf courses, tennis courts and swimming pools.

Recreation in Region V is dominated by Nebraska's southwest reservoirs. The public water acreage in this region is over three times that of any other region. Though constructed primarily for irrigation and flood control,

Irrigation reservoirs provide opportunities for boating, water skiing and other water-based forms of outdoor recreation. Late summer drawdowns preclude some of these activities, but such areas provide high-quality sites through much of the peak season.

The Panhandle region has more than enough raw recreational resources to offset many of the deficiencies of other regions in the state. The problem, though, is how to get the recreators from the east to the recreation in the west. Omaha and Lincoln are a full day's drive. One long-range solution to the problem might be an increased emphasis on intra-state air and rail travel. This would permit better use of the large western park lands while taking advantage of the fuel savings of mass transit.

The last planning region, Region VII, is made up largely of the Nebraska Sandhills. Like the Panhandle, the Sandhills have an abundance of public land and a relatively sparse population. Over 20 percent of the state's recreation lands are in this unit and only 4 percent of its population.

The current and projected recreational needs of this region are primarily for developments to permit camping, picnicking, hiking, etc.

There is also a shortage of water suitable for power boating in the Sandhill region. The many small lakes and potholes adequately meet the needs of local and visiting fishermen. Small, but comparatively expensive, deficiencies also exist for municipal parks, tennis courts and swimming pools.

The bulk of Region Vll's public land is within the boundaries of two National Forests and two National Wildlife Refuges. These areas offer good opportunities for hiking, nature study and wildlife observation. Fishing is excellent on the Valentine National Wildlife Refuge south of Valentine and hunting is good on both National Forests and the Valentine Refuge.

The Niobrara River flows through the northern portion of the Sandhill region. Because of its high esthetic and recreational values it has been proposed for inclusion in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Now largely under private ownership, the Niobrara could be an important recreational asset in future years.

The Nebraska Sandhills are a unique resource, both on a state and federal scale. Total recreational use of this region, like the Panhandle, is far be low what it could support. Planners caution, though, that the Sandhill ecosystem is a fragile one and over development could destroy the very features that make the region unique and interesting.

All of these factors, region by region, were analyzed in the SCORP document and will be used as a basis for decision making. In addition, plan ners have the necessary data to examine individual community, county and other regional needs and deficiencies as called upon and to advise decision makers at all levels. The goal is to improve the balance between the supply and the demand of outdoor recreation opportunities for Nebraskans and nonresident visitors.

Such things as the current fuel shortages will almost certainly have an impact on recreational patterns and may result in a need for changes in priority of funding for state areas and programs. Only time will tell, but planners and administrators will be closely observing recreational demands in the months ahead to determine how best to cope with any new problems.

Some trends, such as the recent up surge in popularity of off-road vehicle use, have caught local, state and federal recreation agencies unprepared. The need for motorcycle, snowmobile and jeep trails is real, and apt to in crease even more dramatically in the years ahead. Ways are being sought to provide such opportunities while protecting the enjoyment of others.

Conflicts between users of recreational lands are inevitable. The word trail means different things to differ ent people. The naturalist with an interest in the native plants and animals of a public area is understand ably upset by the presence of loud trail bikes. Solutions are available but require cooperation from all users and an effort on the part of managing agencies to plan properly in the acquisition and development of new and existing areas.

The list of conflicts between users could go on and on. Suffice it to say that such conflicts are symptomatic of the general problem of insufficient land and water resources to meet all the demands placed upon them. It is the role of the State Outdoor Comprehensive Recreation Plan to aid in pin pointing these areas of need and to promote the implementation of programs to overcome them.

Outdoor Recreation

the outlook?

Outdoor Recreation

the outlook?

ALMOST EVERYONE agrees that planning is a good idea. But planning without implementation accomplishes about the same as no planning at all. Reams of proposals are of no use unless functional, on-the-ground action is taken to improve the outdoor recreational opportunities for Nebraskans.

SCORP provides a wide-ranging summary of the outdoor picture in Nebraska. It contains many recommendations for action needed to take advantage of existing potential and to overcome the shortages identified. These recommendations are far too lengthy to print in this short treatment of the SCORP plan but some of the more important ones warrant mention. Only about 1.5 percent of the state's area is available for public outdoor recreation; and much of this 759,000 acres is located in the western portion of the state while population centers are in the eastern portion. The SCORP plan recommends that to help ease the impact of this problem, the purchase or leasing of additional recreational lands in eastern Nebraska be increased. Private concerns that would derive benefit from the development of recreational areas should be encouraged. Access easements to en able public use of private holdings and tax incentives to landowners who retain natural features should be implemented. Also, the initiation and completion of additional major park developments in eastern Nebraska, such as the Missouri Riverfront in and near Omaha, should be endorsed and encouraged. Public access to rivers, streams and small watershed structures such as farm ponds should be implemented wherever existing conditions permit.

Based on current studies, camping space to accommodate some 5,700 additional camping units is needed now. About three-fourths of this total deficiency centers around the Omaha region. To increase camping facilities the SCORP plan recommends a closer look at the significant potential for recreational use of the lands along the Missouri and Platte rivers. Access sites to the Missouri River, proposed by the Corps of Engineers, should be pursued and complementary facilities to allow camping, picnicking and other outdoor activities should be developed. All types of camping needs, from primitive to highly developed facilities, must be provided.

Water has traditionally been the number one attractant for recreation, either as a resource on which to boat, swim and ski, or, as a scenic backdrop for other outdoor activities such as picnicking, camping or hiking. Because of the uncertain status of many of the proposed multipurpose water resource development projects—projects similar to those that created Lake McConaughy, Harlan County Reservoir or Branched Oak Reservoir —the state should find means for making better recreational use of its existing waters. More intensive management of existing water bodies, including rivers, natural lakes and reservoirs, may be a means of improving the quality and quantity of water oriented recreation.

The number of fishermen is increasing, and pressures exerted on existing waters are often in excess of the biological capabilities of those waters to support a viable population. To increase opportunities for fishermen in the state, SCORP planners suggest efforts to improve access to rivers and streams that are now largely hemmed in by private land. It is also suggested that less desirable species of fish may hold significant potential for meeting fishing demands in some areas. Species such as the carp and bullhead may be a potential source of fishing sport in areas where habitat conditions preclude the establishment of more traditional sport fish species.

Boat registration more than doubled between 1960 and 1972, indicative of the popularity of this sport. Eastern and southeastern Nebraska show the greatest deficits of boating waters. It is unlikely that water resource developments in eastern Nebraska will be implemented in the number or size sufficient to meet the growing demands for water based sports. Construction of Papillion Creek sites will provide Omahans with the opportunity to participate more frequently during evenings and week days, help ing to reduce some of the peak day demands in the Salt Valley Lakes near Lincoln. Ultimately, though, there may be a need for zoning or other restrictions to spread the pressure more uniformly throughout the week.

Also urged in the 1973 SCORP plan is the inclusion of a portion of the Niobrara River in the National Wild and Scenic River Act. Protection under this act would insure that part of this unique, prairie river system would always be preserved in its primitive form.

Bicycling activities accounted for the highest number of total outdoor recreation days in the 1972 SCORP survey. Health, environmental and energy concerns are increasing the demands for bike trails every season. Implementation of increased bike trails funded from every level of govment is recommended. Local governments should be encouraged to establish appropriate bikeways within their areas and a statewide system of trails is proposed. Bicycling should be given high priority in future recreation developments as the activity demands continue to outpace facility develop ment.

Motorcycle registration has also grown dramatically in recent years, increasing five fold during the last 10 years alone. Motorcycle and other off-the-road vehicles are often incompatible with more traditional forms of outdoor recreation and present special problems for multiple-use areas. The irritation resulting from noise pollution and the potential damage to the environment preclude the setting aside of portions of existing state recreation areas in most instances. The SCORP plan suggests that this interest group rely more upon local develop ments or private enterprise to meet much of their recreation needs.

The opportunity for hunting in Nebraska is provided largely by the private landowner. Much of the 759,000 acres of public non-urban land in Nebraska is not suitable for hunting and falls far short of meeting the demands. Wildlife populations for the hunter, as well as the nonconsumptive user, are dependent on habitat which is in turn largely determined by land-use practices. To encourage the preservation and restoration of wildlife habitat in the state, SCORP planners recommend the implementation of tax in centives for those landowners who leave riparian habitat, woody cover, marsh areas or other marginal lands out of crop production. Farm programs that allow for longterm diver sion of croplands, with provisions for the maintenance of cover on the land, should also receive support.

Competition for the state's resources is fierce. No one suspects that recreational interests will always get every thing they ask for. However, by documenting the needs and deficiencies that exist, and by cooperation with other agencies who can implement programs affecting recreational opportunities, planners are in a better position to compete in the decision making. Competition is equally strong within the various recreational interests. This was well illustrated during the 1973 SCORP programming session when nearly 10 million dol lars worth of city and county projects were competing for the three million dollars available for Nebraska. Whenever demand exceeds supply, the need for priorities arises. Guidelines were established by SCORP planners under which priority recreation projects would be given first consideration. Under these guide lines, priority classifications will be given to: (1) areas and projects that conform to existing local or regional comprehensive plans, (2) to projects that assure the preservation of open space in the state's urban centers, (3) projects which benefit society as a whole rather than a limited group of specialized users, (4) projects of a basic nature rather than those highly specialized or elaborate, (5) to acquisition rather than development in areas where shortages of recreational land exist, (6) to those projects that put emphasis on participation sports or activities as opposed to spectator type, and (7) to projects that will alleviate existing deficiencies as opposed to those designed to meet projected shortages.

The optimum goal of SCORP planners, and all agencies concerned with outdoor recreation, is to provide enough public land and facilities to satisfy all users, regardless of the particular philosophy to which each may adhere.

Dr. Frank Tysen described the public's craving for outdoor recreation like this: "Regardless of whether they live in the suburbs or the central cities, Americans of all ages consistently demonstrate their craving to surround themselves with a bit of nature".

The State Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan is Nebraska's at tempt to guide programs aimed at providing the public with adequate lands and facilities to meet this basic desire.

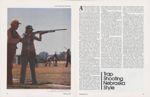

Trap Shooting Nebraska Style

A TRAPSHOOTER'S WIFE once described trapshooting as a game involving a shotgun, a round, clay saucer called a target which sails through the air, and a glassy-eyed shooter with a permanent bruise on his shoulder from recoil. His milieu is a trap range, which consists of a half-buried outhouse and a fan-shaped series of five little sidewalks marked off from 16 to 27 yards from the little house. The shooter, equipped with shotgun, earplugs, vest, shells and shooting glasses, moves from one little sidewalk to the next, shooting at the targets which fly from the buried outhouse every time he calls "pull". The object of the game is to hit as many targets as possible. Not to be confused with a dice game, trap shooting has little to do with luck.

An upswing in trapshooting popular ity in Nebraska began in the early 1960s as the result of a growing need for additional outdoor activity without age, sex or physical-ability restrictions.

Trapshooting is one of the oldest of sports, having originated in England in 1793 where live birds were released from a small box or "trap". In 1866, clay pigeons, similar to the ones used today, and the means to propel them, were invented by George Ligowsky of Cincinnati, Ohio. No one knows whether his creation was the result of a shortage of live birds or whether he had the unenviable task of cleaning their cages. Regardless, his invention was the forerunner of today's electric traps and fluorescent clay pigeons.

In 1900 the first trapshooting championships were held under the guidance of the newly formed Interstate Trapshooting Association. In 1923 the Interstate Association became the Amateur Trapshooting Association or A.T.A., and a permanent home was established in Vandalia, Ohio. The A.T.A. is still the governing body of registered trap shooting and keeps the records of every score fired by over 80,000 members across the country, including nearly 1,000 from Nebraska.

Trapshooting events are divided into three categories; singles, doubles, and handicap. The singles and doubles events are shot from a distance of 16 yards and as their names imply, one target at a time is thrown in the singles event while the doubles are thrown in pairs. The handicap event is shot from distances of 18 to 27 yards at a single target. Yardage is assigned by the A.T.A. and is based on each shooter's average, known ability and wins, thereby making the 27-yard-line the goal of every competitor.

Trapshooters are family people participating together in a sport that offers them exercise, comradeship, competition, sportsmanship, an opportunity to see old friends and make new ones, and a good excuse to go someplace on a beautiful Nebraska weekend.

It's been said that shooting doesn't start in Nebraska until a log chain will stand horizontally when attached to a fence post, yet trapshooters are unqualified optimists when it comes to their favorite sport. A shooter will leave Omaha in a blizzard expecting the sun to be shining when he gets to the gun club in Lincoln; and when it isn't, he will still take to the range with visions of "100 straight" behind his name on the scoreboard.

Each June this optimistic group converges on Doniphan in central Nebraska to decide the Nebraska State Championships. This year marked the 95th annual meeting and tournament of the Nebraska State Sportsmen's Association. In addition to 78 registered trapshoots held in Nebraska in 1973, there were many leagues and trophy shoots held each weekend statewide, with millions of targets shot annually.

In 1972, the first shooters were in ducted into the Nebraska Trapshooting Hall of Fame. The first inductee was Bueford Bailey of Big Springs, followed by Floyd Daily of Fremont, Dayton Dorn of Big Springs, Marion Ingold of Fremont, Bud June of Scottsbluff, Wayne Kennedy of Kimball, James McCole of Gering, Edwin Morehead of Falls City, and Cal Waggoner of Diller in the men's category. The ladies inducted were Blanche Bowers of Benkelman, Carol Estabrook of Omaha, Ruth Justice of Wauneta and Doris Voss of Omaha. Associate members include Harry Koch and Gregg McBride of Omaha, and Frank Middaugh of Fremont.

Trapshooters come in a variety of shapes, sizes and backgrounds. To see one on the street you wou Id never know he was any different from anyone else; an 11-year-old girl, an 85-year-old grandfather, handicapped men in wheelchairs and with only one arm. A trapshooter is a farmer from Ashland, a housewife from Gothenburg, a construction boss from Omaha, a rancher from Big Springs, a conservation officer from Gering or a student from Lincoln. Collectively, these shooters are responsible for channeling millions of dollars into the nation's economy as they travel to distant ranges to compete. They are the outdoorsmen who have imposed themselves an excise tax on sporting arms and ammunition earmarked for conservation use by the federal government. They are among those who make the Grand American Trapshoot in Vandalia, Ohio the largest participation tournament of anv kind in the world with everyone competing for one prize. They devote their time to the teaching of safety as well as the skillful use of a shotgun, and their efforts have paid off. There has never been a fatal accident in the 180-year history of trapshooting.

In 1922, Annie Oakley attended a Surgical Association meeting in Pine hurst, New Jersey. There she was greeted by Dr. Edward III a surgeon who had treated Miss Oakley after a serious injury she received in a trainwreck 19 years prior. At that time his prediction was that she would never be able to shoot again. Miss Oakley enter tained the members of the association

Irish DEATH DOG in the SAND HILLS

I SEE old John Daws only at dog shows, and every time is once too often. Fortunately, he doesn't at tend all shows, but he wins the ones he hits. Old John shows wire fox terriers and white bull terriers —he owns some o\ the best in the country. He says he keeps wires for their spunk and bulls for their sweet dispositions. The truth is that both breeds have temperaments like his own —alert and crafty. One seldom puts anything over on old John Daws. The reverse, how ever, is sometimes the case.

I won't say old John pulls fast ones. It's just that he is very cagey about setting the scene for his dogs to win. A friendly guy, he always comes around just when I'm grooming my terrier in preparation for competition. Exuding good cheer and amiability, John chatters a blue streak, making sure he distracts me. We wire exhibitors usually assemble in the grooming areas at dog shows, and old John usually involves us all in his stories. He has dozens of them, all good, and each designed to absorb the attention we should be giving our dogs.

It was St. Patrick's Day, and we were at the Douglas County dog show, John with a beautiful young male and I with Rayburn Wendigo, a good little fellow just one point short of championship status. I was combing and brushing him diligently, getting him ready for his stint in the ring.

Then old John came by.

"It being St. Patrick's Day, I'm reminded of the pooka that used to haunt Nebraska," he said.

"Pooka, my foot," said I. "They're all in Ireland."

"Oh no, there was one in Nebraska. Oh yes, a long time ago. Like a great black dog, he was, heavy and yellow eyed and grim."

"Sure, sure, John," said I.

"You mean you've never heard of Wen Cwrko and the pooka?"

"Can't say that I have."

"Well, it was back in the days of the sod house when homesteading in the Sand Hills was just beginning," said John, settling in to tell his tale. "That's what Wen Cwrko was, a homesteader. Now Wen was a sturdy guy and sullen. He didn't take any lip from anybody. His place was way out in the Sand Hills.

"Now, about this pooka. He came over from Ireland when the family he had haunted decided to emigrate to America to get away from him. He followed them onto the ship, scaring the iving daylights out of everyone. And, he followed them all the way across country, loping long-tongued and eager behind their covered wagon. It seemed there was nothing they could do to rid themselves of the pooka.

"But, when they reached the Sand Hills, they found their chance.

"Going along one blasting, bright, July midday, they found themselves ahead of the pooka by quite a ways. Sneaking around a sandhill and back behind another, skipping a third, they wound their trail, hoping to confuse the beast and make him lose his way. All of a sudden, a windstorm rose, and in the Sand Hills in those days, when a windstorm blew up it was a sandstorm, too.

"That sandstorm shifted all the hills around, like a woman housecleaning and moving all the stuff in the house so a man can't find his way when he comes back at night. That storm confused the pooka so much he just stayed put. If he didn't know anything else, he knew he was there, although he had no notion of what was around him. That storm was hard on everyone —the Irish couple got pushed clear over to Laramie before they knew it.

"And Wen Cwrko? Well, it blew his homestead, sod house and all, right near to where the pooka sat. Wen had never seen a pooka. He didn't know that they were death dogs, that their breath could sear you like a blast of heat from a furnace, that if they're in the mood, they can swallow a grown man in one gulp and a buffalo in three. Wen didn't know all this, and the pooka didn't know Wen didn't know.

"It was just twilight when the storm stopped, and Wen, who had been in side his house all the time it was shift ing, decided to step outside for a breath of hot, humid, July air. He had about made up his mind to see if he could find hide or hair of his cattle. But the first thing he saw ambling to ward him was this great, black beast, with yellow eyes, fangs bared, and hair a-bristling on his back.

"Well, that didn't cut any ice with Wen. He hasn't seen the animal yet that can outface him, thinks he. So, figuring this is some great big black dog, and not knowing it's the pooka, he walked up to him and without an if, but, or by-your-leave, he grabbed hold of that dog's ears, gave him a good shake until he squealed for mercy, sat him down, and said:

" 'No more of that, see?'

"The pooka had never been treated that way before. Every time someone saw him, the (Continued on page 50)

Prairie Life / Skeletal Adaptations

A SKELETON IS a reflection of an animal's way of life. It has i been fashioned by millions of years of environmental pressure to meet the precise needs of its owner. Few could mistake how the prairie falcon (opposite page) earns its living. Each bone is light yet structurally strong; a requisite for flight. Many of the bones have become fused so that compared to other animals, they are few in number. The forearms are specialized to facilitate flight. Be cause of this modification, other skeletal adaptations were necessary. The jaws had to assume many of the jobs performed by the forearms of other animals. The falcon's skull is modified for holding food, building nests and preening feathers. To avoid disaster, a rapidly flying bird, especially one that captures its prey on the wing, must have excellent eyesight, large eyes and the necessary structures to house them. The whole design of the falcon's skull is specialized to support and protect these essential organs of vision. To further widen its visual field, the head pivots on just one ball-and-socketjoint as compared to two in most classes of animals. But, in order for the falcon's head to be mobile, there must be powerful neck muscles to move it. To provide for the attachment of these muscles, each vertebra of the neck has evolved bony spines on the top, sides and bottom. Most of the prairie falcon's spinal vertebrae have fused to form a rigid frame around which the flying machine is built. The breastbone, a poorly developed feature of most mammalian skeletons, is greatly enlarged to provide an attachment for powerful flight muscles. The legs are elongated; specialized for perching. Each bone of the prairie falcon, and indeed of all animals, is specifically adapted —molded by the pressures of natural selection.

There are some 40,000 known species of animals that possess in ternal skeletons. All are members of the family Chordata, and most belong to one of five classes; mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians or fishes. As a general rule, an animal's skeleton is most like those of its class. A robin skeleton, for example, is more like that of a mallard than that of a fox squirrel. On the other hand, an animal like the little brown bat may have more skeletal features in common with birds than with other mammals.

Regardless of the animal group, a skeleton fulfills three primary functions: it provides protection for vital organs like the brain, heart and lungs; it offers a surface to which muscles can attach; and it provides a firm frame that supports the body. The skeleton has an infinite number of other duties in addition to these basic ones. For some animals, bones act as accessory lungs, provide for feather attachment or even serve as transmitters of sound waves in the inner ear.

Bone, the building material of all skeletons, is composed primarily of two materials: a protein called collagen that makes glue when bone is cooked; and apatite, a mineral made up of calcium and phosphate. This mixture is produced by living bone cells. Bones of young animals are made up almost entirely of living cells, but as an animal reaches maturity, more and more of each bone is composed of nonliving cells. Active cells, usually housed in minute spaces throughout the nonliving bone, continue to repair damaged portions.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about bone is its great strength. Unlike many man-made materials, it can undergo considerable pressure and still return to its original shape with out breaking. Average bone can with stand about 25,000 pounds per square inch before it is crushed. By way of comparison, common building brick collapses under a force of about 4,500 pounds per square inch.

The structure of bone, rather than its chemical composition, accounts for its strength. To simplify matters, we can think of bone as being composed of short fibers of the mineral apatite embedded in a matrix of glue like collagen. Thus the structure is comparable to that of "fibre-glass", so that if under stress a crack appears, it has no "grain" to follow.

Even though bones come in infinite sizes and designs, all are probably variations of one of four basic types: long, tubular bones like those of an arm or leg; flat bones like those found in the skull or pelvis; small, compact, pebble-like bones commonly found in the wrist or ankle; and highly specialized bones, as the vertebrae. From bones of these basic types, skeletons adapted for flying, burrowing or supporting a 200-pound mule deer have evolved.

The evolution of fIight was probably accompanied by the most extensive skeletal adaptations. Since the first birds branched off from the reptiles, some 150 million years ago, most of the modifications to their skeletal system have been to enhance their air borne way of life.

One of the first changes that had to be made to permit sustained flight was a lowering of body density. Like an airplane, a large surface area and low weight were necessary to catch and ride the wind. To accomplish this, the number of bones was reduced so that one served the same function as two or three. The evolving wing under went drastic alterations. The number of finger bones was reduced to three in modern birds and the wrist bones to only two. Gradually, the arm and hand changed into a bony beam that provides a base for the attachment of

the secondary and primary flight

feathers. The end result was a structure with a broad surface area and

minimum weight.

the secondary and primary flight

feathers. The end result was a structure with a broad surface area and

minimum weight.

The avian leg also underwent extensive modification. In modern birds, most of the pebble-like ankle bones were incorporated into the lower portion of the shin bone. The remaining bones became fused to form an "extra" long bone in the leg, an adaptation that is well suited for perching, snatching prey from the grass or wading a shoreline in search of food.

A rigid frame is necessary for any thing that flies, be it a kite, bird or air plane. In the bird's skeleton, this is accomplished by the fusion of all of the vertebrae except those in the neck and tail regions. The backbone of the modern bird is made up of two units. The first of these forms a beam to which the ribs attach. Immediately behind this section is the synscrum, a thin, strong shield made up of sev eral fused vertebrae and the hip girdle.

On the underside of the body, the ribs join to another large, shield shaped bone called the sternum, or breast bone. Looking at a bird skeleton from the front, the sternum appears T-shaped with a long keel extending down. The powerful flight muscles are housed in recesses on either side of the keel. In addition to providing a place for attachment of these muscles, the sternum also protects the chest and part of the belly from crash landings and other mishaps. The sternum, together with the ribs, rigid backbone and synscrum, form a flexible but stout box in which the vital organs are housed.

The most remarkable adaptation for flight is seen only when a bone is cross-sectioned. Most bird bones are hollow to minimize weight, an excellent example of the engineering prin ciple which states that if weight and mass are equal, a tube is stronger than a solid rod. Some, though, are trussed internally (see illustration). The net work of struts and braces further reinforce the bones to achieve maximum strength with a minimum of materials. The final product is a structure similar to the internally braced wing of an aircraft.

In addition to providing strength with a minimum of weight, some hollow bones function as accessory lungs. Air sacs extend into the hollows of many of the larger bones and act as "superchargers" to increase the supply and utilization of oxygen. Because there is a regular exchange with at mospheric air, these sacs serve yet another function —temperature regulation. During periods of high activity, the intake of outside air cools the body as well as supplying it with oxygen.

Another skeletal adaptation unique to birds is the hyoid apparatus, or tongue bones. This Y-shaped assemblage of tiny bones is buried deep within the fleshy tongue. When the tongue is not in use, the two arms of the hyoid are retracted back and under the jaw.

All birds have hyoid bones, but their utility is best illustrated in the wood

As a class, birds have undergone extensive skeletal change, but it is the mammals that show the greatest skeletal variation. They have adapted to every imaginable habitat. Moles and gophers seldom emerge from their subterranean world, beavers are every bit as at home in their watery world as are the fishes, and bats capture insects on the wing just as effectively as any nighthawk.

Many of the adaptations for flight found in birds are also found in bats, the only mammals that fly. Bat bones are generally reduced in number and hollowed. Unlike a bird's wing, though, a bat's wing is basically an elongated hand with thin skin webbed between the bones. The bones found in a bat's skull, trunk and legs are still mammal-like, closely resembling those of a small rodent. As in the birds, the breastbone has undergone alterations to provide for the attachment of flight muscles.

Fossorial mammals, those adapted for life underground, have also undergone skeletal alterations. Among Nebraska mammals, only the moles and pocket gophers spend most of their time in the soil, but others, such as the kangaroo rat and ground squirrel, spend a considerable amount of time in burrows and may show some fossorial adaptations.

Skeletal adaptations are much more profound in these animals than their external appearances would suggest. Inasmuch as the chief occupation of fossorial mammals is digging, their main strength is concentrated in the forepart of the body, and it is here that the most extensive skeletal changes have been made. Just as the foreparts of birds are specialized for the attach ment of the enormous flight muscles, so too is the forepart of the fossorial mammal adapted ^for the attachment of muscles that power the front claws. The entire shoulder girdle is made up of short, stout bones that provide the mechanical framework for the digging machine. The humerus, the uppermost bone of the arm, is so completely modified in some burrowing mammals that few would guess that it is the counterpart of the more usual long, slender bones. This broad, convoluted bone is a mass of hooks and pits to which thick sheets of muscle attach. The pelvic region of fossorial mammals is likewise specialized for subterranean life, being narrowed and simplified to allow turns in small passageways. The most common adaptations for life underground are a reduction in the length of the limbs, the development areas on the skeleton for muscle attachment, thick short necks, and specialization of the forefeet for digging.

Aquatic mammals, like the beaver, have made adjustments for their way of life, too. Because of the buoyant nature of water, weight is no great problem, and consequently the skeletons of aquatic mammals are generally thick, massive and unsophisticated. Aquatic or semi-aquatic animals generally have fusiform shaped bodies, short, stout limbs, tails that serve as either a rudder or flipper, and, relative to their next of kin, are large in size. These external characteristics are all reflected in the skeleton.

Mammals that live on the land — rather than fly, swim, or burrow — have skeletal systems that are less modified. The most apparent differences among these walking and running animals are found in the bones of the legs and feet.

Arboreal mammals, like the raccoon, possess generalized skeletons but have some specialized adaptations for their aerial life. Generally, the tail and limbs of these animals are elongated to facilitate branch-to-branch move ment. Oftentimes, the fingers are op posable, and both the tail and digits are prehensile to help them grasp limbs or rough tree bark.

Mammals with a more shuffling walk, like the opossum, have more generalized, versatile limbs. They are not highly specialized for any one mode of locomotion and move acceptably well in many different environments. These types of mammals are called plantigrade because they walk on their wrists and ankles as well as their toes.

In contrast, cursorial, or running mammals, like the deer or pronghorn, walk on their toes. Their leg bones are long and strong to permit speedy flight from predators. Generally, the hind limbs are longer and heavier so that the animal can literally push its body into motion. Cursorial animals pay a price for this specialization, though. Since their legs are designed primarily for forward-backward motion, very little lateral movement is possible.

Saltatorial, or jumping animals, such as the kangaroo rat and jump ing mouse, have shortened front limbs and elongated hind limbs and feet. Most of these hopping animals have evolved long tails, often exceeding the body in length, to help them maintain their balance while bouncing across their grassland homes.

So logical are the designs of bones and skeletons that paleontologists, anatomists who deal with life from past geological periods, can often determine the appearance and habits of animals that lived millions of years ago from the shape of a single fossil bone or even a bone fragment. The daily pressure of finding a meal, and avoiding being someone elses, soon weeds out animals that cannot efficiently adapt to their environment. Every species of animal living today has proven itself to be the most efficient at its exact way of life. This jockeying for survival is a day-to-day occurrence, and over millions of years, there are losers and winners. Many adaptations go into molding an animal for its specific way of living, but possibly those of the skeleton are the most basic and decisive.

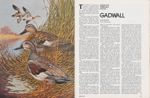

NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA... GADWALL

Art by Tom KronenTHE GADWALL, Chauleasmus strepeous, is perhaps one of the least conspicuous ducks found in Nebraska. The fact that the bird has rather drab plumage when compared to some other puddle ducks could account for his obscurity.

There are a variety of common or local names for the gadwall, including gray duck, chickacock, chickock, creek duck, glisson duck, gray wigeon, prairie mallard, redwing, specklebelly, bleating duck and wigeon.

The gadwall should be one of the easiest puddle ducks to identify as it is the only one with a white speculum. However, it is often confused with female pintails and young male pintails, with which it commonly associates. This indiscriminate error often leads to the common name of "grey ducks."

An adult male in winter plumage appears as a medium-sized, dark grayish-brown bodied duck with a noticeably paler neck and head. A characteristic black rump is a key feature to the gadwall's identification while on the water. The male's bill is bluish-black and usually has a trace of orange at its base and along the edge. The female's bill, in comparison, is a dusky orange with spots. Both sexes have yellow feet, the male's being much brighter and having black webbing between the toes. The female's webbing is a dusky color.

The adult female has a uniformly brown mottled body, the head and neck being somewhat paler colored. When resting on the water, the white on the wing is not always visible. The gadwall sits low and flat, while the baldpate rests buoyantly, seem ingly more alert, with its tail held high.

When in flight, the white speculum and black rump of the gadwall are quite conspicuous. The baldpate, which it is often confused with, has a white wing patch on the forepart of the wing. The middle coverts of the male gadwall are reddish or chestnut colored, looking like a red dish wing patch.

Gadwalls usually fly insmall,compact groups. He is a swift flyer and usually flies on a direct course with out the dipping characteristics of some other species with which he may be confused. He is frequently JUNE 1974 found in association with pintails and baldpates.

The gadwall probably has a wider world distribution than any other duck. South America and Australia are the only two places this duck is not to be found. In Nebraska he is found in the south-central rainwater basins as well as the sandhill lakes. Gadwalls migrate late in the spring and are among the first birds to go south in the fall. Surveys of breeding birds in Nebraska indicate roughly 13 percent to be gadwall.

Vegetable matter such as pond weed, sedges, algae, coontail, grasses, cultivated and miscellane ous grains make up about 98 percent of the gadwall's diet. Water bugs, water beetles, flies, various other insects and larva make up the remaining 2 percent. It might also be noted that the bulk of the animal matter is taken during the summer months when broods are present. The gadwall is essentially a surface feeding duck but will not hesitate to dive to feed when necessary. It walks well on land and will often visitfields of wheat and barley, or whatever grain is available. Gadwalls will also eat acorns and nuts.

Following an elaborate courtship the gadwall builds her nest, preferring sites such as islands, but she will build in meadows or prairies. The nest is a scooped-out hollow lined with material from the vicinity and down from her body. The normal clutch is 10-11 creamy-white eggs but may contain from 7-13. Incubation is from 24-26 days. The young ducklings can swim as soon as they are hatched.