NEBRASKAland

April 1974 50 cents

NEBRASKAland

VOL. 52 / NO. 4 / APRIL 1974 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Fifty cents per copy. Subscription rates $3 for one year, $6 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. commission Chairman: Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-central District, (308) 452-3800 Vice Chairman: James W. McNair, Imperial Southwest District, (308) 882-4425 Second Vice Chairman: Jack D. Obbink, Lincoln Southeast District, (402) 488-3862 Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-central District, (308) 745-1694 Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 Director: Willard R. Barbee Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, Jr. Assistant Director: Richard J. Spady William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: Jon Farrar, Ken Bouc, Faye Musil, Tim Hergenrader Photography: Greg Beaumont, Bob Grier, Steve O'Hare Layout Design: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: C. G. Pritchard, Duane Westerholt Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1974. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska Travel articles financially supported by Department of Economic Development Ronald J. Mertens, Deputy Director John Rosenow, Travel and Tourism Director Contents FEATURES SCALE DOWN FOR ACTION FANATIC FOR FLIES 8 GUNS AND GUNMEN 12 HARDWOOD LEGACY 14 BASS FORMULA 16 FISHING NEBRASKA 18 BASICS OF FISHING 35 STRIPER TIME 36 PRAIRIE LIFE/MECHANICS OF VISION 38 FAUNA/RACCOON 42 DEPARTMENTS SPEAK UP TRADING POST 49 COVER: Boating on Lake McConaughy. A special on Nebraska's fishing begins on page 18. Photo by Lowell Johnson. OPPOSITE: One of the first flowers of Spring, the pasqueflower, Anemone patens, brightens the dry prairies and plains. Also called wind flowers, they grew in such profusion the pioneers referred to them as "prairie smoke". Photograph by Greg Beaumont.

Speak up

How Many Hooks?Sir / I enjoyed the article by Steve Olson on Pumping up Pike. As an avid ice fisherman, I would like to know how many tip ups one man can use. I've read the 1974 Nebraska Fishing Guide and the hook-and-line limitations. In stream and ice fishing, no more than 5 hooks on a line or 15 hooks in the aggregate are allowed. Would you please make this clear to me and many other ice fishermen on exactly how many tipups to use?

Gary Self Omaha, Nebr.What the regulations state, in somewhat technical terms, is that when river fishing (one-half mile or more above the inlet of a lake or reservoir) and when ice fishing, anglers can use up to 15 lines if they have only one hook each. However, any combination can be used —five lines with three hooks each, etc., but no more than five hooks can be tied to one line. Therefore, the maximum would be three lines with five hooks each, (editor)

Save the YoungSir / Whoever was responsible for the article on pages 32 and 33 of the January, 1974 NEBRASKAland (Holding the Peaks) is to be congratulated and thanked warmly. It has been a long time since I wondered why the largemouth bass were not protected up to the time they were large enough to smell up a frying pan. It has always irked me to see grown men as well as kids yanking 3 and 4-inch bass out of our gravel pits, taking them home and probably destroying them knowing they would be of very small value in a frying pan. I hope this new rule can be pounded into the heads of those who deliberately destroy small bass. There are a lot of little ones in our gravel pits but they stand little chance of ever growing up if they are not protected in some way. I am for the person or persons who got this rule into motion. Thanks.

F. J. Otradovec Pilger, Nebr. Early StockerSir / Listening to Jack Curran and Lowell Johnson being interviewed about NEBRASKAIand on "Conversations" today, I recall vividly the earliest days of the magazine.

It was then little more than a mimeo graphed sheet. Being an avid hunting and fishing outdoorsman myself, and living in a rural community, I took it upon myself to sell 150 subscriptions in the neighborhood. I believe the price was 75 cents or less.

To reward my efforts of stirring up interest in the Game Commission's projects, a great many pheasants were consigned to the Oakland area. I was asked to select the spots to release them.

When I visited the Game Commission's office in the State House (a cramped and crowded area on the 10th floor) concerning my big desire to stock our part of the state, I conferred with an unusually tall man whose name I cannot fully recall —but think it was a Mr. Gilbert.

This man was the first head of the Commission to be actually educated for the job. Prior to this the job was more or less a political football and many were not educated in game management or conservation.

I am now disabled but enjoy the big interest my grandchildren have in fishing, hunting and camping.

Edward W. Jensen Oakland, Nebr. An Angry HunterSir / The January 22 Omaha World-Herald devoted considerable coverage to Jack Cramer of Omaha who had the dubious honor of killing one of the few lynx in our state. I'm angry! Why, why, why must everything be hunted to extinction? Many people would thrill to seeing such a rare animal; Mr. Cramer killed it-the Herald made his act an act of heroism.

Since the state seems reluctant to protect our few remaining big cats from the predation of thrill-seeking hunters, at least the press should refrain from glamorizing the act.

I might add that I am a hunter; I always have been, and hopefully always will be. However, I cannot understand why something must be killed merely because it is alive.

Robert Heckathorn Rosalie, Nebr.The Game and Parks Commission has for years been attempting to obtain jurisdiction over all wildlife in the state, in order to develop sound management principles. Without this authority, management of predators such as the lynx, bobcat, and coyote, among others, is impossible.

The Commission feels that because predators and prey exist in harmony within our ecosystem, this authority is required both to protect the predator and properly manage the prey (pheasant, quail, rabbit, etc.). Unfortunately, predators are classed as non-game species and remain unprotected.

The legislature retains control over these predator species. One thing concerned people such as yourself can do is to contact your legislative representative and in form him or her of your thoughts.

There are private individuals and organizations who are concerned with this problem and are pressing for legislation giving the Commission the needed jurisdiction; perhaps joining forces with one of these groups would be a good move because numbers of voters impresses legislators. Conversely, there are large groups opposed to giving the Commission this authority.

We agree with you that wildlife shouldn't be killed merely because it is alive. We also agree that publicity for improper actions is at best dubious; the improper action in this case was shooting something without first properly identifying the animal, (editor)

Likes photosSir / The beautiful pictures that I find in your publication are used to make posters that I use to decorate the bulletin boards of my 8th grade science class. Not only are they decorative, but show the interdependent relationship of the many forms of life that we know. We also enjoy the many articles on wildlife. Thank you for such an enjoy able and useful publication. You've sold me on Nebraska as well as NEBRASKAland. Hope to visit your state soon.

Mrs. Lydia Norsworthy Oklahoma City, Okla. Homecoming (purple martin)Six thousand miles off to Brazil, then back to the same old gourd hung on the same old cabin; for though he may have toured two continents, he comes right back each year to last year's spot: humble gourd or grand apartment it's forgotten not.

Doris Wight Baraboo, Wise. History BuffSir / As a transplanted Nebraskan (health reasons) I still enjoy knowing what is going on in Nebraska. I still have many friends and relatives in Nebraska, Lincoln to North Platte, and at one time knew quite a lot about the state having covered a good portion of it, but find that by reading your fine magazine from cover to cover, these past 10 years, I have learned a great deal more.

How about some stories about Nebraska history like those written by your famous writers Nellie Snyder Yost, Mari Sandoz and others.

Olin Waddill, Gordon, Nebraska, spent several winters here and I am sure he is good for a few stories about the Nebraska Sand Hills.

Keep up the good work as I love every issue of NEBRASKAland.

James A. Cope Wickenburg, Ariz. Ode To The Ringneck He struts with his majestic and Oriental grandeur Flowing about his presence. Mingled are his colors, giving him an armor Unmatched by his proteges. His ability to evade the mechanical-like actions And the persistence of his stalking enemies is uncanny And he guards his domain with the Utmost precision and dignity. His pre-warning of flight from his pursuers Only accentuates his elusiveness and distinct pride. He is truly, The King of the croplands! Collyer D. Cronk Seward, Neb. The vote's inSir / A great big vote of appreciation for the picture of the coyote on the cover of the January issue of your magazine, and for the landscape scene on page 2 by photographers Greg Beaumont and Bob Grier.

To those of us who are interested in the conservation of wild life, the article "Prairie Life/Role of the Predator" as well as the excellent photographs that are a part of this article, by Jon Farrar, we offer our thanks for a job especially well done, timely, interesting and factual.

L. D. and Ethel Fairbairn Hemet, Cal.NEBRASKAland Magazine invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to Speak Up. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters. — Editor.

BITE DETECTOR Huck Finn never had it so good! This rod holder signals you with a loud, clearly audible buzzing alarm at the slightest nibble. Its sensitivity is fully adjustable in case you don't want to be disturbed by anything less than a good, solid strike. This new BITE DETECTOR has been used successfully and enthusiastically by fishermen for the past 3 years. It is now being offered for the first time to the general public. Pat no 3707801 UNCLE LOUIE'S BITE DETECTOR BOX 37 DELL RAPIDS, SOUTH DAKOTA 57022 Please Rush Bite Detectors $7.95 Each, Two for $13.50 DMONEY ORDER DCHECK DC.O.D. (Postage Paid if payment is enclosed) Name Address

Scale Down for Action

Our first use of ultra-light gear shows it to be an effective and exciting angling weapon

Photograph by Ken BoucEVERYTHING'S been getting bigger and bigger over the years, and the Madison Avenue boys would like us to believe that automatically means better. But, fishermen have always been a bit contrary by nature, and so development in the opposite direction seemed only natural.

The end result is another kind of fishing called "ultra-light."

Ultra-light has been around for several years, so it can't really be called new. For the most part, it is just open-face spinning equipment scaled down to the point that it feels like a child's toy. But, in addition to amplifying the sport of catching fish, the gear can be an extremely effective weapon in the hands of someone with angling savvy.

Hauling in hefty stringers of white bass and hand picking limits of walleye showed NEBRASKAland photographer Bob Grier and me that ultra-light gear is anything but a toy.

We had gotten the ultra-light bug mainly because it was the one basic type of fishing paraphernalia that was not already included in our equipment inventory. I had given up on the "bass stick" school of fishing earlier in the year, mainly because the rod with the pool-cue action made casting more work than recreation, and using one to winch in fish was somehow short on excitement. Besides, picking backlashes from a free-spool casting reel all afternoon was not my idea of fun.

Flyrodding had also been ruled out, since heat and bright summer sun had pushed most fish out of range, into deeper water. And, Bob didn't want to think about regular spinning gear for a while. He had just lost an expensive outfit at Pawnee Lake when a backrest failed, sending him toppling backwards to the bottom of the boat in the "dying cockroach" position while his rod and reel flipped overboard.

On Friday morning, Bob, armed with about $20 worth of new rod, reel, line and a few lures, and I, with a combination of new and not-so-new ultra light gear, loaded up to cover a series of assignments in the western part of the state.

That same afternoon we were scheduled to photograph and gather information on the arrival of striped bass fry, flown from Virginia on the Commission's plane, and introduction of the fish into the North Platte Fish Hatchery system. But, a blown tire on our rig near Lexington and trouble finding a replacement, ate up the one-hour pad in our schedule. And, unexpected tailwinds all the way from the east coast put the Commission's plane in North Platte in record time. By the time we arrived, the whole process that we were to photograph and observe had been completed.

Our next commitment was in Scottsbluff, where we were to cover an archery fishing tournament and appear as guests on a local television program. But we didn't have to be there for some 18 hours, giving us ample opportunity to test our dainty new fishing gear at Lake Maloney.

As we circled the lake, things looked slow at the outlet, so we continued on to the inlet. A few anglers were on hand and no red-hot action was apparent, but we elected to try it.

Bob was a bit quicker than me in shedding his shoes and donning breast waders, and his little jig had been dragged through the water a couple of times before I managed to tie on a small spinner. The half dozen or so other fishermen standing on either side of us did double takes and sprouted amused little smiles at the sight of our flimsy tackle, but continued flinging their minnows or tandem jigs into the current without a word.

Bob struck paydirt first, tying into a white bass of just over a pound after about a dozen casts. His next three or four tries showed that he had hit upon the right combination, as he landed several more keepers.

He would cast his jig just slightly upstream, then let it settle as the current carried it along. Just before the lure touched bottom, he would begin a slow retrieve, bringing the rod tip back slowly, then keeping the line fairly tight while cranking in. This method gave Bob four or five nice white bass and a crappie, while I took a few runty whites on my spinner, and the other anglers (Continued on page 44)

FANATIC FOR FLIES

Pitting tiny 'dries' against stream-bred trout brings out the best in angler and fish, and is the ultimate water sport

TROUT WATERS, regardless of the time or place, hold a mystical influence over fly fishermen, their fascination for the sport taking them great distances to pit their skill and experience against a fish at least equally skilled and cunning.

For Dick Nelson, Conservation Education Coordinator with the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, fly fish ing is a way of life —almost a religion. A native of South Dakota, Dick has followed the meandering flow of most trout streams in the midwest and mountains.

He was a natural to ask for guidance when I first began thinking of fly fish ing, and after some preliminary discussions, we found ourselves overlooking a trout pool on Cherry County's famed Snake River.

Sitting on a beaver-dropped log above the pool, we discussed the trout, his lifestyle, and what it would take to out-smart him using natural fly imitations.

Talking in low tones, Dick told of the trout's ability to sense even the slight est error on the fisherman's part, and he outlined his feelings and experiences on trout waters.

"Presentation of the fly rates about 50 percent of the battle, with water conditions, weather and light also play ing a role. The naturalness of the fly, how it is delivered onto the water and the current's draw on the line—it's all very important."

Pointing to the swirl of water left by a feeding fish, he continued as he tied a two-pound-test leader to the fly line.

"The trout is an indicator of the water quality of a stream. With the so-called progress of man on the increase across the country, the trout echoes the rise in pollution —he's always among the first to go!

"Knowing you can drink right from a trout stream is reason enough for travel ing a long distance to fish it," he added.

With the last rays of a dying sun draping the steep canyon wall above us, Dick finished the leader knot, and carefully watching the rising fish, he selected a number 20 Brown Bivisible fly from his vest.

"Here is one of the most satisfying aspects of fly fishing —being able to tie your own fly patterns. I spend many

Trout enjoy shaded, cooler water during the hot summer months, and may be found where grassy banks overhang portions of the stream. After giving startled fish time to calm down, approach the prime hide outs carefully from downstream. Each type of stream may be fished using a different method, but by matching the natural bait trout are hitting, then dropping it lightly on the water just upstream of any activity, chances for a strike are good.

A starting selection of patterns should include those shown here. Each pattern comes in different sizes, and experience will eventually show the most popular patterns and sizes. Fly tying is yet another rewarding aspect of fly fishing, and many enjoy tying their small insect imitations as much as fishing for the wily trout.long winter nights at the bench every year, getting ready for the upcoming season."

Sitting there watching him tie the small insect imitation to the leader, I could sense the purpose in his move ments. It was only after the fly and knot met his close inspection that he started moving toward the pool.

This stretch of the Snake is filled with quiet, deep-running pools, with areas of swift moving water between. Like most, this pool was blocked on one side by a fallen cedar, and the far bank showed evidence of being undercut —a prime lair for waiting trout.

Half crawling, half stooped, Dick eased his way to the lower end of the pool and began moving the fly rod back and forth, stripping line from the reel to lengthen the cast. After several seconds, he dropped the fly onto a fast moving riffle at the head of the pool.

A perfect presentation, but the little fly drifted over the pool without so much as a bump. The second cast fared no better, although a rising fish near the fly dispelled my doubts that the fish had somehow spooked and quit feeding.

On the third cast, a swirl of water met the fly and the action began as Dick set the hook, not knowing what size fish had taken the fly. With one powerful leap, a silver-gray trout began a short tail walk across the pool, break ing the two-pound leader as if it were made of spider web.

Dick quickly dropped back into his stooped position and began crawling away from the side of the pool.

"He was a good one —might have gone four pounds," was all he said that is repeatable, his shaking fingers giving away his excitement of the moment.

"You'll never get over that moment when a nice fish hits the fly. That moment makes the long evenings preparing gear and the long trip to get here — everything —worthwhile."

"Your success can never be measured by the number offish you take," he added. "I'm sure that most natural bait or spin fishermen might sometimes take more fish from a stream like this, but I get just as much enjoyment catch ing a few with the fly rod."

Continually watching the pool for renewed feeding activity, Dick began a short checklist of the equipment necessary to begin fly fishing.

"The two most important items are the fly line and rod. You don't need to spend too much on a reel, as it only serves to hold the line. A vest to store flies and related gear comes in handy.

In response to my question about flies, Dick mentioned that there are several patterns that seem to be useful throughout the year, and that a basic kit should include dry flies, wet flies, and both streamers and nymphs.

"The drys I seem to use most are the Brown Bivisible, the Adams, the Irresistible, and the Light Cahill. Wets needed might include the Gray Hackle, Coachman, and March Brown. For streamers, the Muddler Minnow, Black Ghost, and White Bucktail seem to be the most popular. For nymphs, Caddis and Quill Gordon patterns are probably my favorites.

After putting a stronger leader on the fly line, Dick returned to the head of the pool and began casting. After a couple of missed strikes, he set the hook on a nice 14-inch brown.

Fighting like one twice his size, the trout required a good five minutes to land, stripping line from Dick's hands and attempting to tangle itself in the fallen cedar at the end of the pool.

"All you can do," Dick said as he finally brought the fish from the water, "is apply whatever power to the rod that you think the leader will take. In this case I was lucky. Had he gotten into that cedar, it would have been all over."

The brown was completely spent from the fight. Thinking that the fish might not survive, Dick cleaned it and placing wet grass inside the body cavity, dropped it into the creel.

"By gilling and cleaning the fish right away, you avoid that job at the end of the day, and besides, it improves the table quality of the meat."

After releasing several more fish in the one-pound class, Dick hooked an other nice brown and the battle was on. But, it lasted only briefly. This time the fish broke the hook at the bend in the shank. The incident brought to mind a remark made earlier by the landowner.

Bill Powell, the owner of the section of stream we were fishing, had told us of several tackle busters that seemed to inhabit this pool—fish that he had hooked on several occasions but was unable to land.

Releasing another trout back into the pool, Dick talked about the importance of releasing fish. "That's one thing nice about fly fishing," he said. "The fish can be released because they aren't in jured. This is very important where the stream can't support heavy pressure, and few of them can. Probably any stream can be over harvested, so many concerned fly fishermen put back most, and sometimes all the fish they hook.

All in all, we had caught and released more than a dozen fish before starting upstream to check other pools and explore that part of the river.

Each year the water running from Merritt is diverted through the Ainsworth Canal to irrigate crops in the eastern portion of the Sand Hills. This leaves the summer Snake but a skinny relative of the powerful winter river. In most places, the water flowing over the stream bed was less than knee deep, but there were many excellent pools each looking like trout lairs.

Although a handful of ranchers own or lease portions of the Snake, including Les Kime and Powell, permission to fish is usually given to the considerate angler. Kime charges a small trespass fee of all anglers and sightseers interested in the waterfalls on his land. The fire hazard during the hot summer months requires caution on the part of fishermen, and each rancher is quick to relate any regulations he might main tain on his property.

The falls are beautiful indeed, but for the fly fisherman, the brown and rain bow trout are the main attractions. The browns outnumber rainbows, but what he lacks in numbers the rainbow makes up for in fight. Usually aerial in his resistance to the hook, the rainbow provides a different type of fight than the usually deep-running brown.

Finding another pool of rising fish, Dick quickly caught and released several more trout, and then we added some nice 12 to 15-inch browns and a rainbow to the creel before beginning the long climb out of the canyon.

Reaching the top in the last glow of evening light, we agreed that fly fish ing, especially on the Snake with it's tackle-busting trout and beautiful canyon country, was an outdoor experience of the highest order.

And for me, this trip had shown why fly fishermen will travel clear across the country in quest of the hard-fighting and always exciting trout.

Guns and gunmen

Frontier tough guys with quick hands and tempers proved the undoing of many a quiet, reserved settler or cowboy during barroom arguments. While not professionals, shooting other folks before they could get to them was a serious hobby for many. Some, like this picture of "Old Jules", father of novelist Mari Sandoz, either went out of their way to look for trouble, or at least made little effort avoid ing it. Perhaps they, more than the hired gun, were actually the more dangerous of the twoIF IT CAN BE pinned down, the modern cinematic image of western gunfighters probably dates to "The Great Train Robbery", but it's been going great guns ever since. From the jangling spurs and 10-gallon hats of the 1930s and 40s to the ultrarealism of today's oaters, the gunmen of the Golden West are heroes of the silver screen. However, their feats of gunmanship often meet heady resistance in theaters and living rooms across the nation.

Two lean, mean and lanky cowpokes meet in a showdown on a dusty, dilapidated frontier street. Both men make a play for their "irons". The hero, with the speed of an attacking mongoose, draws and plugs his adversary despite the bad guy "pulling leather" first. Across America, elbows burrow between ribs as bleary eyed spectators, in bursts of supposedly expert knowledge, proclaim, "Theycouldne'eradonthat".

Poppycock.

Hollywood stretches the truth a bit. Well, let's face it, Hollywood lies a lot. But movie makers are often correct about the gunfighters they portray, and the razzle dazzle of frontier pistolmen. Those old-timers were killers, paid or freelance, who had one thing in mind during a showdown —to do unto others before they can do it unto them. They were fast and deadly. But, they were not the supermen we see portrayed today. Far from it. So, the trick is to separate fact from fiction on the sliver screen.

As the flickering tube drones on into the night, some "gun nut" nudges his wife and scoffs at a 500-yard shot made by a cowboy from the saddle of a horse at a wild gallop. The viewer's doubt may be well-enough founded, but the fact remains that such a feat was possible under the right conditions. During the Civil War, some sharpshooters picked off canoneers at up to 1,000 yards —with muzzle-loaders. Television and movies may go out of their way to make the cowpuncher look silly or heroic, but at the same time, they usually stay within the realm of possibility.

Take, for instance, the "never-need-to-reload" sequence where a rifleman snaps caps from dawn to dusk without ever feeding the piece. A bit farfetched, perhaps, but keep in mind that the old lever-action rifles were reputedly loaded on Sunday and fired continu ously all week. Maybe not, but 13 shots as fast as you could throw the lever and pull the trigger caused a hectic killing zone compared to the laborious, tedious task of reloading a muzzier. As fantastic as some of the long-gun shooting may appear, though, it is the hand gun and the men who used it for business that created most of the stir.

Maybe one of the wisest moves that film producers ever made was to avoid pinpointing dates. All the viewer knows is that the setting is in the Old West, which has since become a world-famous tradition. Judging from most of the gun rigs the heroes sport, keeping TV fans in the dark is probably wise. In the first place, it's pretty hard to imagine all the action taking place after the 1880s. Still, the buscadero belt (the fancy, low-slung holster rig that ties down to the thigh) manages to find its way into every western flick. Problem is, the outfit keeps showing up in Nebraska in the 1870s and 80s, but it wasn't even developed until the 1890s, and then was confined to Texas for the most part. So, gun toters on the Nebraska plains had to be content with shoving their irons into their belts or using a military type holster.

Carrying a firearm often posed problems for would be gunmen. Since the fancy holsters not only cost a lot of money but weren't even in existence until the latter part of the 19th Century, most of them had to make do with what they had. Necessity being the mother of invention, a good share of gunmen who needed a sheath for their weapons created carriers. After the Civil War, military hardware and leather goods started filtering into civilian hands. A military holster, with its protective flap, kept a handgun securely in place, but cut down on speed of withdrawal. So, someone deciced to lop off the flap. Speed went up and more than one man went down as a result of the innovation.

Slinging the whole affair low on the hip and tying it to the leg wasn't the normal thing to do. Sitting astride a horse with a hogleg tied (Continued on page 45)

Trees are a living heirloom, a reminder from generation to generation of a continuing commitment to the future

Hardwood Legacy

MY FATHER had a dream. It was about trees and grass. That's all, just trees and grass. In the late 1940s, during the last days of World War II, he moved a little house and a new wife onto a quarter-section of his father's land, and he closed his eyes and saw the day when the entire section could be turned over to prairie grass and hardwoods.

They tell me he worked like a man possessed those first years planting trees —Chinese elm and poplar, pine and cedar, and a few fruit trees, cherry and apple. Cottonwood, boxelder and ash volunteered. He carried hundreds of buckets of water to his little saplings, and he babied them as much as he could between haying and plowing.

It wasn't long before his small daughter was racing into the house on a sum mer evening with a leaf in her clenched fist, demanding excitedly, "What kind of a tree did this come from, Daddy?" There was always a grin and a reply, and I'd run back out to find another leaf I didn't recognize.

My sister and I climbed trees like squirrels during our childhood. When we had a difference of opinion, I'd hide in the top of a tree until the fight blew over. I learned about birds as I swung from the limbs of our front-yard ash.

The cherry trees yielded many quarts of sour pie cherries, and the first thing I learned to bake was a cherry pie. I can remember my sister and I running into the house, pudgy fists full of bing cherries, to announce the ripeness of the sweet fruit.

I remember quiet walks on shady trails through the trees, following the wild things that made the trails, and daydreaming adolescent dreams.

My father dreamed of replacing his original trees, as they died and decayed, with hardwood trees —walnut and hickory and oak. He died when I was 16, though, leaving half a legacy for some one else to build on.

The years have passed and the trees remain, but one by one, they're dying. The fruit trees need to be replaced. Still my family shelters behind the trees. When a north wind blusters across the prairie, and the wind chill is -40°, the chill factor in the yard is approximately the same as the temperature registered by a thermometer. In summer, the 14 house and yard are cooled by the breath of the trees.

They have been neglected these 10 years. There is just no time to tend them, and maybe something that has been neglected that long deserves to die. But it's time now to plant the hard woods, time to revive tender care and expand the legacy my family has been harboring for three generations —my grandfather's, when a dream was born; my father's when a dream began to take root and grow; and mine, when more needs to be done to perpetuate it.

But why all the preoccupation with hardwood trees? Perhaps it's like a living counterpart to family heirlooms. To begin with, they're beautiful. Like fine silver or china or hand-crafted brooch, they are a reminder from generation to generation of a commitment made to the future. And, like the heirloom, they are valuable. They can be sold for timber to stave off want.

Once an heirloom is gone, it's gone, but the hardwoods, if used wisely in lean times and replenished in fat ones, can provide a pocketful of security generation after generation.

Many men have dreamed of hardwoods, I suppose, and some have dreamed in them. Oak and pecan, walnut and hickory, and some kinds of cherrywood have become fine furnishings in the hands of craftsmen. The hands of men have carved their visions in the dark cores of ebony.

It seems almost that the legacy of trees is a way of life, a different sort of feel for the world. Building and creating with living things feels different than with concrete and steel. It's a bobwhite quail whistling in the morning brush at the trees' edge, a quail whose home you unconsciously engineered. It's a squirrel scolding from a nut-laden branch, whose daily bread you've provided. It's the mourning dove cooing peacefully, perfectly at home in your orchard. It's dozens of songbirds nest ing in your trees and shrubs. It's a white-tailed deer browsing the edges.

According to one observant old man, plants and animals are companions. They do have preferences of "who" they like to live with. Plant a new community of trees on your land, he grins earnestly, and their friends will follow. Turkey, ruffed grouse and chipmunks like oak and nut trees. Some dreamers dimly suspect that Nebraskans could have plenty of all three, and many others to entertain them, if there were hardwood trees.

Dreamers see feed lots, see cattle suffering on "clean" land in glaring summer and harsh winter, and they envision trees. Maybe a clump of trees could provide life-saving protection to the cattle and diversion to the cattleman, a break in the harsh sameness of flat tened hills. Here could be a legacy of concern for the animal, for tomorrow's world, a vision of kindness and value to be reaped tomorrow.

But where can a dreamer start to build his house of comfort and kind ness for the future —his heirloom? A man named Caha found diversion in his orchard. He began by planning an intermixture of pecan, black walnut, hickory, chestnuts, persimmon, apricot, hazlenut, apple, peach and grapes. He looked at a slightly eastward-hang ing slope and saw trees laden with fruit and nuts, birds and animals to share them with him, and he saw timber.

He began 30 or 40 years ago with some knowledge of trees and made his orchard his classroom. Like other visionaries with less experience or knowledge, he sought professional advice occasionally on where to plant what and which varieties are friendly to one another. He kept in touch with his trees, giving them attention when they needed it.

He planned around some little known secrets of plant life, placing more than one individual of each variety in close cohjunction and catering to the plants' preference for intercross ing. He recognized that trees frequently refuse to self-pollinate through such mechanisms as differing maturity. He knew the progency of intercrossing are stronger than those of the same individual just as inbred animals are weaker.

He made his orchard an interesting multi-culture. His wide variety of trees prevented epidemics. If disease and pests attacked one species of plant, those surrounding it, immune to the at tack, prevented its spread. He knew his dream couldn't be wiped out through one onslaught of cedar rust or apple worms or Dutch elm disease. His trees NEBRASKAland

Caha's orchard was the child of his mind and his hands, and like other parents, he sought to make it self-sufficient so it could survive without him.

Caha is dead now, but most of his original trees are still there, almost 20 years later. The hickory, pecan, walnut and persimmon are in good condition. All the plants had a good start. It seems they grew and grew. Most of them survived Nebraska summer and Nebraska winter — heat, drought, blizzards, frost....

APRIL 1974Through all this time, they have adapted themselves until today the or chard grows wild but luxuriantly, with little or no human help. Sumac, elm, boxelder, and mulberry have moved in and intermixed with volunteers of the seedlings from Cahan's trees. These seedlings are descendants of valuable parent plants. They carry the parental genes, but also genes with character istics that have been influenced climatically.

The new seedlings are the result of natural intercrossing of quality parent plants in a new territory. They are hybrids with their parents' characteristics uniquely adapted to the new territory. Apple varieties that are susceptible to cedar rust are about gone now, but it is no matter. There are plenty of other varieties remaining, and they are immune to the disease.

There is another man, a living man with a dream. His dream encompasses more than one orchard. It extends across an entire state, perhaps farther.

He sees trees, hardwoods, in every logical nook and cranny of land, making waste corners into beautiful, profit able sidelines for their owners. He sees farmers and ranchers working their one-man orchards, harvesting fruits and nuts and fine timber. He envisions these small orchards serving as classrooms for the men who work them. "Men should not be afraid to work," he says, "to sweat."

Men can learn about themselves, and about life by planting trees, he thinks. "Men are children, children," he says. "All the time they push over trees with their bulldozers crying, 'See what I can do!'"

"Plants are alive," he says. "Some how they want to stay al ive... they fight for life...they forgive you for the mistakes you make." He believes that it would be easy for any Nebraska landowner to plant an orchard. "It is simple," he remarks, "anyone can do it."

He sees Nebraska's natural clumps of trees and brush and envisions a few oak or nut trees in their midst. They would not replace the natives, only enhance them. He envisions landowners making their own experiments with new species, planting them along with tried and true varieties. If they thrive, then perhaps they are suited to Nebraska. Those that do well add just a little bit more to the fascinating mosaic of Nebraska vegetation and animal life.

But he sees beyond the trees. He dreams of families living with the trees and sharing the fruits of their orchards — the apples and pears and peaches, the squirrels and deer, the shade, the shelter from winter, and the peaceful ness of a cool summer evening under whispering leaves.

"Some men," he says, "risk nothing and ask only 'when do I get my money back?' Others, they risk, and they make something."

When after largemouths, silence and accuracy are golden

Bass Formula

THE LARGEMOUTH bass is one of the most sought after game fish in Nebraska lakes. More time is probably spent trying to put bass on stringers than any other fish. There are good populations of them in most lakes, yet very few good catches come to the docks after a hard day's fishing. Why? I will try to tell you why, and also show you what to use and how to use it to improve your bass fishing.

I am primarily a bass fisherman, and when I come home with a fine string of bass, it is no accident. Each year I land over 500 largemouths, and just as I learned to do this, just about anyone should be able to.

Let's start off with the proper tackle. A good rod 16 NEBRASKAland with plenty of backbone is a must in most bass fishing. This rod doesn't need to be as stiff as the so called worm rods, but it must be able to throw a 1/2 to 3A-ounce lure on 20-pound-test line into the wind. It must also have the strength to horse a good bass 8 or 10 feet after the strike. The shorter rods are my pick, say 5 1/2 to 6 feet, as you often will be casting at tight spots from tight spots, and longer rods are awkward to operate under such conditions.

A good reel is also a must, and in my opinion, the free-spool casting reel cannot be beat. Some spin-cast reels are alright, but I feel the open-faced spinning type has little to offer. But, whatever type rod and reel you have, it must be filled with at least 20-pound-test line. My choice is braided line, but there is nothing wrong with monofilament. In any case, even braided line should have a monofilament leader. If you insist on using light tackle, you'll lose many fine bass before you decide you cannot handle large fish in close quarters.

Whatever type tackle you start with, you must use it properly. This means being able to put your lure into a tight spot at distances of from 25 to about 60 feet. You should be able to cast along a narrow path of open water to the spots where the fish are, under low-hanging limbs or brush, to within a foot of a single stump or stick. Casting accuracy is very important in bass fishing, so practice, practice, practice.

Some anglers think that working the shoreline is all there is to catching bass, and lots of them are caught there. But, hundreds of bass are caught away from shore for every one taken along it. Even working shorelines is easier with a boat, so I think a boat is desirable. I like one that will ride rough water, for safety sake, but also one with low sides for easy casting. A low-sided boat also will not blow around in the wind as much, but I use two anchors to hold the position I want.

Most boat owners have motors, which they use to cover lots of water in a short time. This is fine, but always shut off your motor and either drift or paddle into position to avoid spooking the fish. Be as quiet as possible at all times. Never drop or drag anything around inside your boat, as any noise puts the bass on guard. I carpeted the floor of my boat to deaden sound. Quiet is very important in any fishing, but especially so in my technique because I do most of it in from three to seven feet of water.

Electric motors are great labor savers and quiet enough for maneuvering, but even they should not be operated right over the area you plan to fish. Another thing, in my opinion —no boat is large enough for more than two bass fishermen under any conditions.

As to when is the best time for bass fishing, I would have to say there is no set best time. I go whenever I have the time and feel like going. And, I've caught good strings of bass under all conditions from clear to over cast, from hot to cold, in rain and shine, with no wind to over 60 mph gales, in evenings and every hour of the day. No one knows for sure when the bass will hit unless he is out there when they start hitting. My personal choice is a day suited for comfort and ease of handling the boat —either cloudy or clear with pleasant temperature and with little or no wind. I also iike early mornings because traffic on the lake was nil all night and things have settled down from the day before.

When fishing a typical warm-water lake, you can see spots which look good such as weed beds, brushy areas and such. These areas are good places to throw a lure. Most of the bass will be back in such cover, not just close to it, and you must be able to get your lure into the small areas of open water if you are going to score regularly in this game.

I have worked such areas and nearly had the rod taken out of my hands when the lure went through a small opening. The bass was there all the time, but refused to come after my offerings until I put the lure with in his range. You will find that most good bass (over three pounds) will be caught in places where your lure must be cast to an exact spot that most other anglers never come close to. That is why accuracy is so important, and also why you must have heavy enough line and rod to be able to horse that bass into open water before he can take a few wraps around a branch.

Most bass caught by the average fisherman are one pounders or under. These bass haven't gotten smart yet and will chase anything that comes close to them. Big bass are there and waiting, so it's up to you to get your lure right into their dining room. Sure, some lunkers are taken by random casting, but the really good bass fish erman comes home regularly with beauties by being able to cast accurately, being quiet, and having the right tackle to handle them when they are hooked.

I compare bass fishing to the young lad who pest ered his mother so much she finally gave him a salt shaker and told him to go out and try to catch birds by putting salt on their tails. After several hours, the boy finally got smart and figured that was not the way to catch birds. And, the same thing happens to large bass. They refuse to chase anything all over the lake. Instead, they lay in the cover and let the food come to them. When a small fish, frog, or your lure happens by in range, watch out! Whenever you hit one of the right spots, the bass will strike if he is there. The strike will come the moment the lure hits the water or with the first couple turns of the reel handle. So, be prepared at all times to set the hook and get that bass out in open water.

Brush and weed beds give you targets to throw your lure at, but there is also underwater brush and other good cover. When you spot these underwater bass magnets, remember exactly where they are. Brush is good wherever you find it, and it will be the easiest fishing areas you can find. Whenever you go after bass, remember such spots and try them throughout the season. The one you catch there liked that spot, so it makes sense that others will like it too. Good areas do not remain vacant long.

As the sun starts to climb, I have found that it is best to fish the shady side of cover, as the bass will most likely be there, out of the direct rays of the sun. And, if good areas fail on the first try, don't give up on them. I keep retracing my fishing patterns every couple hours, and sooner or later it generally pays off. Perhaps a boat came too close or (Continued on page 46)

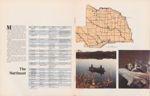

Variety is the spice of fishing for many, while others like to concentrate on one species. Regardless, there should be some helpful information here to spice up any angling

Fishing Nebraska

Fishing Nebraska

FEW ANGLERS have time to be come familiar with all the many kinds of fishing Nebraska has to offer. Anyone who tried would be very busy indeed.

The Panhandle offers flyrodding and spin-casting for trout in the area's many streams, or casting and trolling for rainbows and walleye in reservoirs. In the Sand Hills, there's a bit of stream and reservoir fishing, but the main attractions are natural lakes offering northern pike, bass, and panfish. The big sport in the southwest is trolling or casting on reservoirs for walleye and white bass, while the southeast offers opportunity to plug for largemouths in farm ponds, sandpits and reservoirs, to dabble bait for panfish, or go after catfish in warm-water rivers and creeks. And, northeast Nebraska provides a blend of many of these. A "Chain of Lakes" adjacent to Interstate 80 even offers a sporting interlude for those on the move.

But, while one or two types of fishing might predominate in a region, a fisherman cannot assume that another sort of sport is not available nearby. Nebraska has some 11,000 miles of streams plus about 326 public lakes and ponds, which total some 140,000 acres, and reservoirs. In addition, private ponds and natural lakes total about 18,000 in number, making up some 56,000 acres. A look at the charts on the following pages shows the variety each region offers.

Other information on fishing Nebraska is available locally from Game and Parks Commission offices in Lincoln, Omaha, Bassett, Norfolk, North Platte, and Alliance, and from conservation officers throughout the state.

Included are pamphlets that explain Nebraska's angling regulations and others on a variety of related subjects.

Conservation officers and Commission offices, as well as some 1,200 permit vendors throughout the state, are also sources of fishing permits. Permits are required for all nonresidents, except those under 16 years of age who are ac companied by a parent or guardian who has a valid nonresident permit. Residents 16 or older must be licensed. Permit fees include:

NONRESIDENT ANNUAL $10.00 NONRESIDENTTHREE-DAY $ 3.00 RESIDENT ANNUAL $ 4.00 RESIDENT COMBINATION FISH-HUNT $ 8.00 (Permit fees are subject to change by the State Legislature)

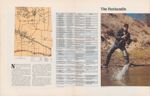

The Panhandle

NEBRASKA'S Panhandle is primarily an area of stream and river fish ing, and trout are the major attractions.

Streams of the North Platte Valley offer excellent fishing in late fall and again in early spring, as chunky rainbow trout from Lake McConaughy migrate on spawning runs. Many of these rainbows scale 5 pounds or more.

Peak activity there is seasonal, since the big fish return to Lake McConaughy when spawning is completed. Brown trout, year-round residents, provide action at other times of the year, however.

Streams of the Pine Ridge and Niobrara Valley offer both browns and rain bows, and the fish are there year-round.

All trout streams are a valuable resource and are closely managed. Special regulations are in effect for some areas, such as bans on possession of landing nets, a ban on archery-fishing, and complete closure, in some cases. Anglers should check regulations closely.

Nearly all are on private land, and permission of the landowner is required both by law and by rules of good sports manship.

Major impoundments in the area are Whitney, Box Butte, Minatare and Kimball reservoirs. All are used to store irrigation water, and heavy summertime demand can cause extreme drawdowns. This can affect fishing success and make launching of boats difficult.

NO. NAME LOCATION SPECIES REMARKS 1 Monroe Creek* 4.5 N of Harrison Brown and brook trout 2 Sowbelly Creek* NE of Harrison Brown and rainbow trout 3 Hat Creek* NE of Harrison f Brown trout both branches 4 Soldier Creek* 3 W of Crawford Brown and rainbow trout middle branch 5 White River* Crawford area Brown and rainbow trout upper 15 miles 6 Larabie Creek* NW of Gordon Brown trout lower 3 miles 7 Chadron Creek* S of Chadron Brown and rainbow trout upper 9 miles 8 Bordeaux Creek* SE of Chadron I Brown and rainbow trout upper portion 9 Beaver Creek* N of Hay Springs Brown trout upper portion 10 White Clay Creek* NW of Rushville Brown and rainbow trout upper 8 miles 11 Niobrara River* North part of district Brown and rainbow trout state line to Box Butte Reservoir 12 Pine Creek* SE of Rushville Brown trout 5 miles below Smith Lake 13 Dry Sheep Creek* W of Morrill Brown and rainbow trout 14 Sheep Creek* W of Morrill Brown and rainbow trout upper 10 miles 15 Spotted Tail Creek* W of Mitchell Brown and rainbow trout upper 5 miles 16 Dry Spotted Tail Creek* W of Mitchell Brown and rainbow trout 17 Silvernail Drain* E of North port Brown trout 18 Lawrence Fork* W of Redington Brown trout 19 Tub Springs* E of Mitchell Brown and rainbow trout upper 5 miles 20 Winter Creek* NE of Scottsbluff Brown and rainbow trout upper 5 miles 21 Nine Mile Creek* E of Minatare Brown and rainbow trout portions closed to fishing Oct. 1-Dec. 31, as posted 22 Wildhorse Creek* W of Bayard Brown and rainbow trout both branches 23 Red Willow Creek* E of Bayard Brown and rainbow trout 24 Greenwood Creek* SE of Bridgeport Brown and rainbow trout upper portion 25 Pumpkin Creek* E of Bridgeport Brown and rainbow trout lower 2 miles 26 Lodgepole Creek* South part of district Brown trout upper portion 27 Stuckenhole Creek* W of Bayard Brown and rainbow trout 28 North Platte River* Central part of district Rainbow trout, white bass, walleye, channel catfish rainbow trout in winter and spring, rest in spring or early summer; all boats allowed 29 Smith Lake 23 S of Rushville Lm. bass, channel catfish, bullheads, pike camping available; boats restricted to 5 mph 30 Crescent Lake Refuge 22 N of Oshkosh no live minnows allowed; no camping; no power boats except electric motors Island Lake __ Pike, Lm. bass, perch Hackberry Lake renovated 1973, should provide fishing for Lm. bass, channel catfish in 1975 closed during 1974 Crane Lake Pike, Lm. bass, perch, bluegill 31 Walgren Lake 5 SE of Hay Springs Bullheads no power boats allowed; camping available 32 Chadron Park Pond 9 S of Chadron Lm. bass, bluegill, bullheads power boats not allowed 33 Box Butte Reservoir 10 N of Hemingford Pike, walleye, Lm. bass, Sm. bass, white bass, bluegill, channel catfish all boats allowed; camping available 34 Whitney Lake 1.5 W of Whitney Pike, perch, walleye, white bass, crappie, channel catfish all boats allowed 35 Bridgeport Pits N edge of Bridgeport ___ Lm. bass, Sm. bass, channel catfish, bluegill camping available,- all boats allowed 36 Chadron City Reservoir 5.5 S of Chadron Rainbow trout, Lm. bass, Sm. bass, spotted bass 37 Government Dams NE of Crawford Lm. bass, bluegill, bullheads, channel catfish 38 Isham Dam* NW of Hay Springs Lm. bass, perch, bluegill, bullheads all boats allowed; private property, permission required 39 Terry's Pit Gering __ Trout power boats not allowed 40 University Lake 7 SW of Scottsbluff^ Pike, Lm. bass, bullheads all boats allowed 41 Cochran Lake 2 SW of Melbeta Lm. bass, bullheads, bluegill, channel catfish all boats allowed 42 Lake Minatare 12 NE of ScottsblutT i Pike, walleye, perch, crappie, channel catfish closed during waterfowl seasons; all craft allowed; camping available 43 Kimball Reservoir 4 E of Bushnell Walleye, Lm. bass, Sm. bass, bluegill, channel catfish, rainbow trout all boats allowed permission required

The Sandhills

Photograph by Bob Grier NO. NAME LOCATION SPECIES REMARKS 1 Fairfield Creek* N of Wood Lake Brown trout 2 Coon Creek* NE of Bassett Brown trout 3 Long Pine Creek* N and W of Long Pine Brown and rainbow trout Public access at Long Pine Recreation Area on U.S. 20 and at Pine Glen Wildlife Area 2 E, 8.2 N of Long Pine 4 Plum Creek* N and W of Ainsworth Brown trout 5 Schlagel Creek* S of Valentine Brown trout 6 Snake River* NW portion of district Brown trout 7 Gracie Creek* NW of Burwell Brown and rainbow trout 8 Middle Loup River* W of Mullen Milburn to Boelus Brown trout, channel catfish Milburn Diversion stocked experimentally with catfish in 1973 9 Niobrara River* North part of district Channel catfish, sauger, carp sauger below Spencer Dam 10 Calamus River* NW of Burwell Pike, channel catfish 11 North Loup River* SE of Purdum Channel catfish 12 Dismal River* W of Dunning Brown trout channel catfish stocked experimentally in lower portion in 1973 13 Shell Lake 6 NW of Irwin Pike, perch, bluegill all boats allowed 14 Cottonwood Lake 0.5 E of Merriman Pike, Lm. bass, bluegill, bullhead camping available; all boats allowed 15 Schoolhouse Lake* 18 S of Cody Perch all boats allowed 16 Round Lake* 31 N of Whitman Walleye, Lm. bass; rock bass permission required; contact Stan Huffman, Whitman, NE. 17 Merritt Reservoir 26 SW Valentine Rainbow trout, walleye, Lm. bass, Sm, bass, crappie, bluegill, perch, white bass, bullheads all boats allowed; camping available 18 Valentine Refuge 28 S of Valentine camping prohibited; live minnows prohibited; power boats prohibited except electric motors Watts Lake Pike, perch, crappie, bluegill Hackberry Lake Bullheads Dewey Lake Walleye, Lm. bass, rock bass, perch, pike Duck Lake Bluegill, Lm. bass, bullheads, crappie Rice Lake Bluegill, Lm. bass, bullheads, crappie Clear Lake Sacramento perch, walleye, Lm. bass, yellow perch Pelican Lake Pike, bluegill, yellow perch West Long Lake Lm. bass, yellow perch, bluegill 19 Big Alkali Lake 20 S of Valentine Bullhead, Lm. bass, pike, white bass, bluegill, perch, walleye camping available; all boats allowed 20 Clear Lake 23 SW of Johnstown Bluegill, Lm. bass, bullheads all boats allowed 21 Long Lake 20 SW of Johnstown Renovated 1973; should provide fishing for Lm. bass, perch, bluegill in 1975 camping available; power boats restricted to 5 mph 22 Fish Lake 25 SE of Bassett Pike, Lm. bass, yellow perch all boats allowed 23 Atkinson Lake 0.5 W of Atkinson Pike, Lm. bass, channel catfish, carp, crappie, bluegill camping available; power boats not allowed 24 Overton Lake 23 SE of Newport Lm. bass, bluegill, rock bass, walleye power boats not allowed; minnows not allowed 25 Victoria Springs Lake 7 E of Anselmo Winterkilled in 1972-73; should provide fishing for Lm. bass, rock bass, and channel catfish in 1975 26 Arnold Lake S edge of Arnold Lm. bass, rock bass camping available; power boats not allowed 27 Frye Lake* 1 N, 1 E of Hyannis Lm. bass, crappie, bluegill, yellow perch * permission requiredSAND HILLS anglers have a few very good trout streams, and a fine lake in Merritt Reservoir. But, their biggest fishing opportunity comes from the many natural lakes in the region.

Some of these are under public ownership, such as those of the Valentine National Wildlife Refuge. Others are privately owned, but open to the public through access agreements with the Game and Parks Commission, while still others are in private hands and open only to those with permission of the landowner.

Some, however, are extremely alkaline, while others are subject to periodic winterkill. Neither support good populations, so an angler might avoid wasted effort by inquiring locally on a given lake's condition.

Important game species in these lakes are northern pike and largemouth bass, plus panfish such as yellow perch, blue gill, and crappie. Other lakes are excellent for bullheads, and a few support good walleye populations.

Ice fishing is very popular and productive on these waters, especially for fishermen after big northerns or panfish. Northern pike fishermen also do extremely well in early spring, only a few weeks after the ice melts.

The Northeast

MAIN FEATURE of northeast Nebraska fishing is the Missouri River, especially the unchannelized portions between Gavins Point Dam and Ponca, and the stretch above Lewis and Clark Lake.

This is the last of the Missouri that remains in anything like its natural state. Its meandering channels, shallow bars and undercut banks offer fine habitat for walleye, sauger, catfish, white bass and paddlefish.

Other important rivers in the northeast include the Niobrara, Elkhorn and Loup systems, where catfishing predominates. Other important water is the Loup Power Canal, which is called home by some of the biggest catfish in the state.

The northeast also offers a bit of trout fishing in the Verdigre and Steel Creek drainages. Some public access is available on the East Branch of Verdigre Creek, but the rest is under private own ership and permission is required to fish there.

That is also the case with many farm ponds in the area, although the fine bass, panfish, catfish and occasional trout make asking permission well worth the effort.

NO. NAME LOCATION SPECIES REMARKS 1 Lewis and Clark Lake 15 N of Crofton Crappie, white bass, walleye, sauger, channel catfish, drum, carp camping available; all boats allowed 2 Cottonwood Lake 15 N of Crofton Lm. bass, pike, walleye, crappie portions under South Dakota jurisdiction; observe signs for areas open to Nebraska permit holders; power boats not allowed 3 Gavins Point Dam Tailwaters 15 N of Crofton Channel catfish, drum, flathead catfish, carp, crappie, white bass, walleye, sauger, buffalo, paddlefish all boats allowed; life jacket must be worn by boaters at all times in tailwaters area 4 DeSoto Refuge Lake 4 E of Blair Carp, buffalo, Lm. bass, channel catfish, crappie open from January 5 through February 28 and from April 15 through September 15 during daylignt hours unless otherwise posted 5 Pilger Lake 2 NEof Pilger Lm. bass, bluegill, channel catfish power boats not allowed 6 Skyview Lake in Norfolk Lm. bass, bluegill, channel catfish power boats not allowed 7 Fremont Lakes 3 W of Fremont Lm. bass, bluegill, channel catfish, bullheads; carp in Lake #5 camping available; power boating on Victory Lake and Lake #20 only 8 Dead Timber 5 N, 1.5 Eof Scribner Bullheads, carp camping available,- power boats not allowed 9 Lake North 3 N of Columbus Crappie, drum, walleye, channel catfish all boats allowed; camping available 10 Lake Babcock 3 N of Columbus Carp, catfish power boats not allowed 11 Pibel Lake 4 S, 1 E of Bartlett Lm. bass, pike, bluegill, bullhead camping available,- power boats not allowed 12 Lake Ericson 0.5 SE of Ericson Lm. bass, Sm. bass, rock bass, pike, bluegill, channel catfish boats limited to 5 mph 13 Grove Lake 2 N of Royal Bluegill, Lm. bass, channel catfish, bullhead, walleye, crappie camping available; boats limited to 5 mph 14 Oept. of Roads lake 1 E of Burwell Channel catfish power boats not allowed 15 Missouri River Northern and eastern border of district Channel catfish, flathead catfish, drum, carp, crappie, white bass, walleye, sauger, paddlefish, pike all boats allowed 16 North Branch, Verdigre Creek* W of Verdigre Brown trout 17 East Branch, Veridgre Creek* S of Verdigre Brown and rainbow trout public access available as posted 18 Middle Branch, Verdigre Creek* SW of Verdigre Brown trout upper 5 miles IS Steel Creek* NW of Verdigre Brown trout upper 8 miles 20 Beaver Creek* NW of Genoa Channel catfish, carp most power boats not practical 21 Cedar River* NW of Fullerton Channel catfish, carp, Lm. bass, pike most power boats not practical 22 Elkhorn River* central part of district Channel catfish, flathead catfish, carp, Lm. bass, pike most power boats not practical 23 North Loup River* SW portion of district Channel catfish, carp most power boats not practical 24 Loup Canal Genoa to Columbus Channel catfish, flathead catfish, drum, carp, crappie Farm ponds and sandpits* entire district Lm. bass, bluegill channel catfish, crappie

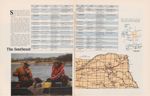

The Southwest

Photograph by Bob Grier permission required NO. NAME LOCATION SPECIES REMARKS 1 Lake McConaughy 10 N of Ogailala Walleye, white bass, rainbow trout, Sm. bass, channel catfish, pike, crappie, yellow perch, bullhead, striped bass camping available; all boats allowed 2 Lake Ogallala 10 N of Ogallala Sm. bass, rainbow troi^t, channel catfish, yellow perch excellent for yellow perch in winter; all boats allowed; camping available 3 Enders Reservoir 5 E, 4.5 S of Imperial Walleye, channel catfish, crappie, yellow perch camping available; all boats allowed 4 Swanson Reservoir 2 W of Trenton Walleye, crappie, channel catfish, white bass camping available; all boats allowed 5 Rock Creek Lake 4 N, 1 W of Parks Bluegill, Lm. bass, pike, channel catfish, bullhead, walleye camping available; power boats not allowed 6 Red Willow Reservoir 11 N of McCook Lm. bass, Sm. bass, pike, bluegill, crappie, channel catfish, walleye camping available; all boats allowed 7 Hayes Center Lake 12 NEof Hayes Center Lm. bass, catfish, pike, bluegill camping available; all boats allowed 8 Medicine Creek Reservoir 2 W, 7 N of Cambridge Lm. bass, drum, white bass, walleye, crappie, channel catfish camping available; all boats allowed 9 Wellfleet Lake 0.5 SW Wellfleet Lm. bass, bluegill, channel catfish, green sunfish, bullhead, pike, walleye camping available; power boats not allowed 10 Harlan County Reservoir 2 S of Republican City Walleye, white bass, crappie, channel catfish camping available, all boats allowed 11 Sandy Channel Wildlife Area 2 S of Elm Creek Interchange, 1-80 Lm. bass, Sm. bass, channel catfish, rock bass 8 lakes on area, camping available; power boats not allowed 12 Kearney County Recreation Area 1 N Ft. Kearny State Historical Park Lm. bass, bluegill, channel catfish, bullheads camping available; power boats not allowed 13 Ansley Lake West edge of Ansley Lm. bass, bluegill, channel catfish 14 Ravenna Lake 1 SE of Ravenna Channel catfish, Lm. bass, sunfish, carp, bluegill, bullhead camping available; power boats not allowed; heavy aquatic vegetation 15 Bowman Lake 0.5 W of Loup City Lm. bass, rock bass, channel catfish camping available; power boats not allowed; heavy aquatic vegetation 16 Sherman Reservoir 4 E, 1 N of Loup City Walleye, crappie, channel catfish, bullheads, Lm. bass, pike 17 Johnson Reservoir 7 S of Lexington Walleye, crappie, channel catfish, white bass camping available; all boats allowed 18 Gallagher Canyon Reservoir 8 S of Cozad Crappie, drum, pike, channel catfish, white bass, yellow perch, walleye, Lm. bass, bluegill camping available; all boats allowed 19 Midway Canyon Reservoir 6 S, 2 W of Cozad White bass, crappie, channel catfish, pike, yellow perch, drum, bluegill, walleye, Lm. bass camping available; all boats allowed 20 Jeffrey Canyon Reservoir 5 S, 3 W of Brady Walleye, crappie, Lm. bass, white bass, drum, channel catfish camping available; all boats allowed 21 Maloney Reservoir 6 S of North Platte Walleye, channel catfish, white bass, crappie, drum camping available; all boats allowed 22 Sutherland Reservoir 2 S of Sutherland White bass, channel catfish, yellow perch, crappie camping available; all boats allowed 23 Platte Valley Canal central part of district Rainbow trout, walleye, white bass, yellow perch, channel catfish boats limited to 5 mph 24 Otter Creek* 12 E Lewellen Brown and rainbow trout 25 North Platte River* North-central portion of district Channel catfish, white bass, pike, rainbow trout excellent above Lake McConaughy for catfish and pike in spring and early summer; most power boats not practical 26 Red Willow Creek* N of McCook Channel catfish, Lm. bass, Sm. bass, pike, bluegill, crappie 27 28 Medicine Creek* NW of Cambridge Channel catfish camping available; all boats allowed Republican River* South part of district White bass, channel catfish, flathead catfish all boats allowed 29 South Loup River* NE part of district Channel catfish, Lm. bass bass limited to backwatersFISHERMEN in southwest Nebraska are almost certain to find themselves on some sort of man-made water, either reservoir, spillway, or canal.

The big reservoirs are by far the main attractions, offering walleye, white bass, catfish and, in the case of Lake McConaughy, rainbow trout. May, June and September are peak months for walleye fishing on these impoundments, and May and August are best for white bass. The same usually applies in canals.

The late-summer white bass fishing is an especially exciting sport. On many lakes, white bass schools on feeding sprees drive shad to the surface, where they attract flocks of hungry gulls. By homing in on the gulls, anglers can pinpoint the bass and quickly fill a stringer by casting flashy artificials.

Another annual event on these reservoirs is the spring catfishing flurry. The upper ends of these reservoirs are the first to warm up as the ice melts, and this draws hordes of catfish. In some years, the catfish are biting enthusiastically while ice still lingers on the main part of the reservoirs.

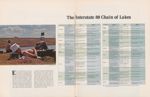

The Interstate 80 Chain of Lakes

EVEN THE fisherman on the move can find sport in Nebraska, especialy if he is crossing the state on Interstate 80. All along the super highway's course between Grand Island and Sutherland, there stretches a "Chain of Lakes" offering largemouth, small mouth and rock bass, catfish, bluegill, and an occasional walleye. Ranging in size from 1 to 53 acres, the lakes were formed as fill material was removed from the floor of the Platte to build the road way. The exceptionally high groundwater table of the area soon filled the pits. Many ot the lakes were stocked with game fish, and some were developed as state wayside areas, offering camping, picnicking and a number of other facilities. Others were purposely left in a natural state, providing habitat for wild life and a haven for the angler who prefers a bit of solitude. Some of these lakes are in private hands, while others are publicly owned. All are visible from the highway, and some are located at or near interchanges. Others, however, can be reached only by county roads, with nearest exits off I-80 listed.

INTERCHANGE Grand Island Alda LOCATION S side of 1-80, 3 east of Grand Island Interchange, mile post 315 N side, 1.5 E of interchange, mile post 313 Morman Island Wayside Area, NE quadrant of interchange 1 N, 2 E, 0.5 S, 1.5 Eof interchange, mile post 309 NE quadrant of interchange Wood River Shelton Gibbon Minden (Nebr. Hwy. 10) NW quadrant of interchange 0.4 S, 1 W, 0.1 N across overpass, 0.2 W, mile post 299 NE quadrant of interchange Windmill Wayside Area, NE quadrant of interchange Bassway Strip, 0.4 S of interchange, turn left, 0.4 N across Platte River bridge, turn right, 1 E to first lake, mile post 281 SEquadrantof interchange, access 0.4 S, left turn, 0.4 N across Platte River bridge, mile post 280 Kearney Odessa Elm Creek 6.5 E of interchange, mile post 279 Bufflehead Wildlife Area, 1.1 N of interchange to 11th St.; 3 E, 1 3, 0.6 E, mile post 276 SW quadrant of interchange 1.1 N of interchange to 11th st, 1.3 W, 0.9 S to overpass approach, left turn, 0.1 S, mile post 271 1.8 W of interchange at west-bound rest stop, mile post 271 4 E of interchange on S side of 1-80, mile post 268 NE quadrant of interchange Coot Shallows Wildlife Area, 0.7 N of interchange, 1.7 W, 0.1 S, mile post 261 Blue Hole Wildlife Area, 0.3 S of interchange, left turn, 0.1 N, right turn, 1.1 E on canal road, mile post 259 SW quadrant of interchange SPECIES Em. bass, channel catfish Sm. bass, bluegill, rough fish Lm. bass, channel catfish bluegill, walleye, rough fish not stocked Lm. bass, channel catfish, bluegill, rough fish Lm. bass, channel catfish, rock bass Lm. bass, channel catfish, rock bass Lm. bass, channel catfish, bluegill REMARKS 6 acres; private access 17 acres; private access 46 acres; public access; camping, drinking water, fireplaces, rest rooms available 25 acres; public access 9.7 acres; private access 16.9 acres; public access; drinking water, picnic tables, fireplaces, restrooms available 15 acres; public access; camping, drinking water, picnic tables, fire: places, restrooms available; hunting 12 acres; public access; drinking water, fireplaces, restrooms, picnic tables available Sm. bass, channel catfish, rock bass, rough fish Sm. bass, channel catfish Sm. bass, channel catfish, rock bass flood damaged, fishing doubtful Sm. bass, channel catfish, rock bass, Lm. bass renovated 1973; experimental ^stocking of Lm. bass, channel catfish, bullheads; should provide fishing in late 1975 Spn- bass, channel catfish, rock bass, Lm. bass Srr': bass, channel catfish, rock bass Renovated in 1973; should provide fishing for Lm. bass JLJ-f-channel catfish in 1975 Sm bass, channel catfish, mck bass sm. bass, channel catfish, r°ck bass, Lm. bass Sm. bass, channel catfish not stocked 19 acres-, public access 4 lakes; 13, 13, 8, and 20 acres; public access 8 acres; public access; camping, drinking water, fireplaces, restrooms, picnic tables available; hunting 12 acres; private access 12 acres, public access 16 acres; private access 15 acres, public access 7 acres; private access 7 acres; public access 15 acres; public access; drinking water, restrooms, picnic tables, fireplaces available 12.5 acres; public access 30 acres; public access; fireplaces, restrooms, picnic tables available; rough fish introduced in 1973 flood 28 acres; public access INTERCHANGE LOCATION SPECIES REMARKS Elm Creek (cont.) 0.3 S, 0.3 W of interchange, mile post 258 subject to flooding; carp, catfish, other river species available 40 acres, private access 3 W of interchange, mile post 253 Sm. bass, channel catfish, rock bass 10 acres; private access Lexington NE quadrant of interchange Sm. bass, channel catfish, rock bass 13 acres; public access 5.5 E, 2.5 S over overpass, 0.2 E, mile post 245 channel catfish, Lm. bass 6.5 acres; public access Darr NW quadrant of interchange Sm. bass, channel catfish, rock bass 18 acres; public access Cozad SE quadrant of interchange Sm. bass, channel catfish, rock bass 16 acres; public access 1 N of interchange to Cozad, 1.7 Won U.S. 30, 0.8 S over 1-80 overpass, 0.1 E, 0.1 N, 0.1 E, mile post 221 Sm. bass, channel catfish, rock bass 18.5 acres, public access; subject to flood damage Willow Island Wildlife Area, 1 N to Cozad, 5.2 Won U.S. 30 to Willow Island, 0.8 S across railroad tracks, left turn, 0.1 N, mile post 217 Sm. bass, channel catfish, rock bass 30 acres; public access; subject to flood damage Gothenburg 0.4 S of interchange, 0.4 E, 0.1 NE, 3.4 E, 0.1 N, mile post 215 Sm. bass, channel catfish, rock bass 13.5 acres; public access 0.3 S of interchange, 0.3 WNW, mile post 212 Sm. bass, channel catfish, rock bass 30 acres, public access; subject to flood damage Brady 6 W of Brady interchange at west-bound rest stop Lm. bass, channel catfish, rock bass 5 acres; public access 1.5 N of interchange to Brady, 3.5 E on U.S. 30, 0.2 S across railroad tracks, mile post 203 Channel catfish, rock bass, Lm. bass 15 acres, public access, Lm. bass stocked in 1972, should be harvestable size in late 1974 0.8 N of interchange, 0.4 W, 0.1 N, 1.6 W across 1-80 overpass Sm. bass, channel catfish, rock bass, bluegill 5.6 acres; public access Maxwell SE quadrant of interchange Sm. bass, channel catfish, rock bass 30 acres; public access 0.3 W of interchange Sm. bass, channel catfish, rock bass 4 acres; private access 0.7 N of interchange, 0.8 W, 0.3 S, mile post 190 Sm. bass, channel catfish, rock bass, bullheads 7 acres; public access 0.7 N of interchange, 2 W, 0.4 N, 3.6 W, 0.5 S, mile post 185 Sm. bass, rock bass 6.6 acres; public access; subject to winter kill North Platte Fremont Slough, 1.5 S of interchange, 4.8 E, 0.3 N, 0.1 E across canal, 0.2 N under 1-80 overpass, 0.3 E, 0.1 N, mile post 182 Sm. bass, channel catfish 30 acres, public access 0.3 S, 0.1 E of interchange Sm. bass, rock bass, chain pickerel, channel catfish, striped bass 26 acres; public access 0.4 S, 3.6 W, 0.9 N across 1-80 overpass, left turn, 0.1 S, mile post 174 Sm. bass, rock bass, chain pickerel, channel catfish 20 acres; public access 0.4 S of interchange, 7.8 W, 1.6 N across 1-80 overpass, right turn, 0.2 S, 0.2 E, mile post 170 Sm. bass, channel catfish, rock bass 20 acres; public access Hershey 0.2 S, 0.2 E of interchange Sm. bass, channel catfish, rock bass, striped bass, walleye, Lm. bass 53 acres; public access 0.2 S of interchange, 3 W, 0.5 N, 0.1 S, mile post 162 Lm. bass, channel catfish, bullheads, rock bass 27 acres; public access; good bullhead fishing KEY In areas marked private access, permission to enter must be obtained from adjacent landowners. All lakes open to non-powered boating.

The Southeast

SEVERAL styles of fishing are in vogue in southeast Nebraska, ranging from cane-poling for panfish on small creeks and farm ponds to trolling for walleye on some fair-sized reservoirs.

For years the catfish of the Missouri, Platte, Nemahas, Blues, and Republican rivers were the mainstay of angling in this area, and they still provide good sport. But good lake fishing has also arrived in the form of flood control reservoirs in the Salt Valley around Lincoln, giving anglers very good fishing for bass, walleye and northern pike. And more water of the same sort will be appearing in this part of the state as lakes of the Papio Watershed near Omaha come of age.

Another important source of fishing water in the area is a multitude of farm ponds, especially in the extreme south eastern counties. These waters offer brawny largemouth bass, catfish and bluegill, in most cases. Sandpits, usually found near major rivers, may also yield some fine fishing. Both are generally on private property and permission of the landowner is required to fish them.

NO. 8 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 NAME Verdon Lake Burchard Lake Rockford Lake Alexandria State Recreation Area Olive Creek Lake Bluestem Lake Wagon Train Lake Stagecoach Lake Hedgefield Lake Yankee Hill Lake Killdeer Lake Conestoga Lake Pawnee Lake Branched Oak Lake Twin Lakes Salt Valley Lake #57A Salt Valley Lake #17A LOCATION 0.5 W of Verdon 3 E, 0.5 N of Burchard 7 E. 2 S of Beatrice 4 E of Alexandria NW of Hallam 2 W of Sprague 2 E of Hickman 2 SW of Hickman 3 E, 1 S of Hickman 2.5 E, 1 S of Denton 2.5 N of Martell 2 N of Denton W of Lincoln 1 N, 4 W of Raymond 3 N, 5 E of Milford 5 W, 1 N of Agnew 1 N of Martell SPECIES Lm. bass, bluegill, channel catfish, crappie Lm. bass, crappie, bluegill, channel catfish Lm. bass, walleye, pike, channel catfish, rock bass, bluegill, bullheads Lm. bass, bluegill, crappie, carp in lake #1; crappie, Lm. bass, bluegill, bullhead, and channel catfish in lakes #2 and 3 Lm. bass, bluegill, walleye, crappie, channel catfish Lm. bass, crappie, channel catfish Channel catfish, Lm. bass, bullheads, carp, white perch Lm. bass, channel catfish, walleye, bluegill, crappie, white perch Lm. bass, channel catfish, bluegill, bullheads Lm. bass, bluegill, channel catfish, walleye, bullheads, crappie Lm. bass, bluegill, channel catfish Lm. bass, bluegill, walleye, channel catfish Lm. bass, bluegill, channel catfish, walleye, crappie Lm. bass, walleye, pike, bluegill. channel catfish, crappie, bullheads Lm. bass, bluegill, channel catfish, pike, walleye Lm. bass, bluegill, channel catfish, pike, walleye, crappie Lm. bass, bluegill, channel catfish, pike, walleye REMARKS camping available; power boats not allowed camping available; power boats limited to 5 mph; closed during waterfowl seasons except face of dam camping available camping available; power boats not allowed camping available; power boats limited to 5 mph camping available; all boats allowed camping available; power boats limited to 5 mph camping available,- power boats limited to 5 mph power boats not allowed power boats not allowed power boats not allowed camping available, all boats allowed camping available, all boats allowed camping available; no-wake boating in portions of lake power boats not allowed; closes to all access during waterfowl seasons

Basics of Fishing

Fishing can be complicated, but those who keep it simple enjoy it most

Extra copies of "Fishing Nebraska" may be obtained from the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, P.O. Box 30370, 2200 North 33rd Street, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Prepared by Ken BoucIN CONJURING up an image of the basic fisherman, most people undoubtedly see a Huck Finn sort of character trudging back from the river or creek toting a cane pole, a half-empty worm can and a stringer loaded with a mess of catfish, bluegill or bullheads.