NEBRASKAland

March 1974 50 cents

NEBRASKAland

VOL. 52 / NO. 3 / MARCH 1974 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Fifty cents per copy. Subscription rates $3 for one year, $6 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. commission Chairman: William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Vice Chairman: Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-central District, (308) 452-3800 Second Vice Chairman: James W. McNair, Imperial Southwest District, (308) 882-4425 Jack D. Obbink, Lincoln Southeast District, (402) 488-3862 Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-central District, (308) 745-1694 Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 Director: Willard R. Barbee Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, Jr. Assistant Director: Richard J. Spady staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: Ken Bouc, Jon Farrar, Faye Musil Photography: Greg Beaumont, Bob Grier Layout Design: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: C. G. Pritchard Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1974. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverabie, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska Travel articles financially supported by Department of Economic Development Ronald J. Mertens, Deputy Director John Rosenow, Travel and Tourism Director Contents FEATURES THE 21st DAY FISHING MAN-MADE WATERS 8 SELLING SAFETY 12 SICKELBILL!. 14 S.O.S. FOR WILDLIFE 26 LEARNING TO LIVE 28 A NEW AWARENESS PRAIRIE LIFE/TERRITORIES 32 38 DEPARTMENTS SPEAK UP TRADING POST 49 COVER: A long-billed curlew incubating her eggs. A photo story on the curlew begins on page 14. OPPOSITE: Sunset over Merritt Reservoir. Photographs by Greg Beaumont.

Speak up

Energy-Crisis HunterSir / The enclosed picture was taken of my father, banker and mayor of Petersburg, Nebr. in 1922. It might well be captioned "Road Hunter During The Energy Crisis".

Anthony Barak Associate Professor Univ. of Nebr. Medical CenterSir / Just a note to tell you how much I enjoy your magazine. In December's issue I especially enjoyed the story by Willetta Lueshen and the very beautiful color photographs by Jon Farrar and also story about how to feed birds in winter. You have a lot to be proud of.

Betty Hansen Racine, Wise. Down on DogsSir / It was the unfortunate timing of my four-year-old son, my father-in-law and my self to actually see dogs, turned loose by hunters, chase, catch and kill a coyote in south-central Nebraska.

I am an avid hunter, including coyotes, but to watch these people turn dogs loose on a cornered coyote is beyond my comprehension of hunting. Then try to explain this act to a four-year-old.

If these people are allowed to do this, can we also use dogs for deer hunting?

Why can't the State Game Commission tax each dog owned by a person hunting in this manner. $10 per dog could reduce the dog hunters and turn it back to the hunters who are willing to work for their trophies.

Dale Daake Milford, Nebr. Where is Calendar?Sir / The pictures in the NEBRASKAland Magazine are really great —the closeups in the January issue were really something. We enjoy the magazine so much and have all issues for several years back.

Disappointed about your not having the calendar this year.

The Dale Craigs Brady, Nebr. No Coyote LossSir / Thank you for the wonderful article on the "Role of the Predator"-also for the beautiful cover of the January issue show ing the coyote.

I have raised livestock near wooded creeks and draws and in the last 15 years have never lost any to the coyote. In some cases some farmers did.

To combine the two good articles on the Predators and "Needed- New Systems and Ethics of Hunting" I must say there must be a change. There are many young sportsmen who would like a chance and that chance would be a cherished one, to shoot but one coyote in a sporting way. Instead we have three airplanes in our area sweeping the countryside, disregarding the rights of land owners, 16 to 20 carloads and pickups of drinking hunters littering the roads. Some coyotes have had as many as 14 men firing at least three rounds each at them. This is certainly no sport and it deprives the hunter who would go out alone to track and get a coyote. Also the prices paid for pelts would surely help some young lad trying to save money for a cherished new gun. Why give it to the gun-toting, drinking hunters?

I've written to many sources trying to stop the bad sport of spotting coyotes with airplanes and got no results.

Marcel Kivar David City, Nebr. Orange For AllSir / I am 61 years old and have fished and hunted all my life. This year I had a deer permit (rifle) and was required to wear 400 square inches of fluorescent orange for safety. That's O.K. But squirrel, pheasant, quail and rabbit hunters came sneaking through the brush, none wearing it. I was in a tree-blind out of danger, but these hunters could very easily have been taken for deer by an inexperienced hunter. Three came through the brush making just the right noise to be a couple of deer. Fifteen bird hunters came by my blind in three days. By the third day, no more deer showed. I believe these hunters should have a break in the season, same as the bow-hunters. If not, they surely should have to wear the protective orange.

Also, lots of hunters are trophy hunters, and if a choice were given, would prefer a buck license. That would leave more any deer permits for the hunters who are just starting and not able to get a buck. Also, on an any-deer permit, I would like to see it changed to any adult deer. I think too many button bucks and young doe are being killed. I have seen deer brought in that would only weigh 70 or 80 pounds —not much more than fawns.

Herbert O. Blackwell Peru, Nebr. Tanning RequestSir / Do you have anything available on preserving and tanning of small skins, such as rabbit or squirrel. My young grandson who likes to hunt, is becoming interested in trying to preserve some skins, and we haven't found much about it. Interested just in something quite simple, and a home-type way that could be done. Anything on use of such home-tanned or preserved skins? Any way to make them into mittens or anything?

Mrs. Richard Poch Milligan, Nebr.Tanning a small animal hide is not difficult, although it requires a little work. And, some are trickier than others because of the thinness of the skin, such as rabbits. However, this method will work on almost anything including deer if you take care.

Scrape all flesh and fat from the hide with the back side of a knife or with the edge of a piece of wood or anything that will scrape without cutting. Then, into 1 1/2 or 2 gallons of water, slowly pour I ounce of concentrated sulfuric acid. Be sure not to pour the water into the acid! Also, use only a glass, plastic or crock container, as the acid will eat through any metal.

Place the hide into the solution so it is totally immersed, cover with wood or other non-metal lid, and let soak for 10 days or a little longer. The acid will "set" the hair so it will not pull out. Then, remove from the acid, rinse thoroughly in fresh water to remove the acid, and rub over the edge of a board. This takes quite a while, and is done to break down the fibers in the skin. When the hide is flexible even when dry, it is ready, and all you have to do is rub in some neatsfoot oil. You can then use it for almost any purpose, including mounting on a board or on cloth as a rug.

Your library should have additional in formation, and there is a taxidermy supply house in Omaha —Elwood Taxidermy Supply. They have kits available for tanning small animals, (editor)

the 21st Day

THE FIRST TIME I heard the tom gobble, he sounded a quarter-mile up the ridge. I cut the distance between us in half, nestled down in some good cover, and gave a hen call. For the next ten minutes we traded calls. Each time I offered the cluck of the hen, the tom responded with his most seductive gobble. Finally, I caught a glimpse of him moving through the Ponderosa pines about 150 yards away. He seemed to be moving toward me without hesitation. To get to me, he had to leave the creek bottom he was following and come up the ridge I was sitting behind.

I eased up to have a look over the ridge. I wanted to know the terrain well enough to guess where he might come out. As I raised up from my kneeling position I caught a movement out of the corner of my eye about the same time a hen let out a perk and started running. She had worked in behind me while my attention was concentrated on the tom. The hen ran about 20 yards or so, then flew off across the canyon. From about 75 yards up the creek, the tom also exploded into the air. Both birds flew off into the bluffs half a mile away.

That was the fifth day of the 1973 Nebraska spring tom turkey hunt, but my first morning out. I'd hunted turkey in the Black Hill region of South Dakota for three years before going to work for the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission as a Conservation Education Coordinator. I was yet to shoot my first turkey.

I drove out from Lincoln the day before. More than anything else, I wanted to get into the hills and enjoy the country by myself, so I waited until after the opening days of the season. That way, I would have the 36,000-acre Ponderosa Special-Use Area south of Crawford pretty much to myself. Lon Lemon, the area manager, had invited me to stay with him, so I would be hunting right out of the headquarters.

I crawled out of the sack at 3:30 a.m. that first morning and walked quite a ways up the road into the area. I had made a couple of peanut butter sandwiches, and intended on staying in the timber all day. The weather was more than cooperative —it must have been about 45 degrees by mid-day, and clear.

After cussing myself for fouling up on that first tom, I started walking the ridge of Hell's canyon. It was about 10 o'clock and the morning's gobbling activity was pretty much over. From my experience in the past, I found that the best chances of hearing a bird during the spring season is from dawn until about one or two hours after sunrise, and then again during the corresponding period in the evening. The rest of the day, unless you're lucky enough to stumble onto a bird, you might as well take it easy doing what you want. Generally what I did was to find some good cover, sit down and call. If nothing happened in 20 minutes or so, I'd sleep for a while, then maybe call again before moving on. Most days I was running on very little sleep, so I would try to pick up what I could during the day in the hills.

It must have been warmer that first day than I thought because I remember lying down in the sun and waking up after a while roasting hot. I'd roll over in the shade for a while and wake up about a half-hour later chilled to the bone. Most days I succeeded in mashing my two sandwiches down to about a quarter-inch wafer.

Not much happened the rest of Wednesday. Mostly, I just tried to be come familiar with the area. I heard birds gobble twice during the day, but couldn't get them to respond to me.

The next morning I was up by 3:30 a.m. again, gorged myself with food and slipped my sandwiches into a coat pocket. It looked like the good weather was over —on my way up to Hell's Canyon it started to spit snow.

I heard only one tom gobble that day and couldn't get him to answer my call. I'm not an expert caller by any means, but my usual tactics are to give the hen call, three or four chirps, then wait at least 15 minutes before calling again. Sometimes I'll rattle the call to imitate a gobbler. If there are any toms within hearing distance they'll generally gobble back. Once I get a tom to answer, the only call I use is the plead ing hen call. Sometimes I get antsy, though, and probably over call. You practically have to look at your watch to be sure of how much time has passed. Whenever there's a tom around, you're always afraid that you're going to lose him, and end up calling too often. More turkeys are lost, I'd guess, because of over calling than not calling enough.

The snow turned out to be the wet stuff that soaks you to the skin in about 30 minutes. It was good for tracking, though. By reading the turkey tracks I got a pretty good idea of where the birds were and what they were doing. I found one fresh track that looked larger than most and followed it for a mile or better before giving it up. After leaving the canyon, the turkey climbed some country rough enough for mountain goats. I decided that probably wasn't the most efficient technique to way-lay a gobbler.

By noon my clothes were thoroughly soaked so I hiked back to the cabin and changed into dry ones. I pulled on a white parka, too, hoping to blend in better with the terrain, but I never saw nor heard another turkey that day. Lon had told me about a hunter who shot three toms and one hen on opening morning. A conservation officer had made the arrest, but it made me burn to think about it. It was my 18th day of hunting turkeys and I hadn't fired a shot. It just didn't seem right.

The weather was a little better Friday -warmer and clearing. The snow started to melt and it got to be sloppy, so it was tricky finding a dry place to sleep.

About 10 o'clock I was sitting on a stump in Hell's Canyon watching the snow crash down from the trees. About 250 yards below me was an opening 50 yards or better across. From farther up the ridge a gobbler came gliding down and dropped right in the center of the opening. He stood there for a minute and kind of looked around like he owned the canyon. I hit my hen call. No response. I hit it again, louder this time. Still (Continued on page 50)

FISHING MAN-MADE WATERS

WITHOUT A DOUBT, fishing has gotten better in Nebraska since the day our first pioneer ancestors arrived. And, the main reason is, of course, the availability of man-made fishing water resulting from irrigation, power, flood control and other developments. While this type of project is open to question on environmental grounds, there is no doubt that such developments have provided some mighty fine fishing as a by-product.

The reservoirs did not present much

of a problem to the state's anglers. They simply dusted off tactics used on natural lakes, modified them some what, and started hauling in fish. But, for the canals, checks, tailwaters, and tailraces associated with these projects, some different wrinkles were necessary.

Each of these features has some characteristics that makes them fish concentration points. Inlets, for example, are an important source of food for shad, minnows, and other small fish. The resulting congregation of bite-sized baitfish, plus worms, grasshoppers and other forms of terrestrial life picked up by the canal, are an irresistible magnet for gamefish like walleye, white bass and catfish.

The current at inlets also attracts fish instinctively looking for a feeder stream at spawning time. But quite often, the inlet itself, or a check farther up the canal, acts as a barrier, concentrating fish until the spawning urge is past.

In some places, the canal itself provides fine fishing, mainly for catfish, but also for walleye, sauger and white bass. Fish in these waters live much as those in a natural stream, although there is less bottom cover, no sandbars, and little shallow water. The current keeps fish well supplied with food, though, and some grow to monster proportions.

The checks in some canals are good places to catch fish. These structures act as baffles to slow the water flow. In doing this, they provide a place where fish can rest without fighting the current, and also serve as barriers to upstream movement. In Nebraska, the only major canal systems that hold fish in any number are operated by the Central Nebraska Public Power and Irrigation District (also called Tri-County), and the Loup Power District. These hold water all year long, while others in the state are dry part of the year and therefore do not produce fish.

Among the most productive man-made features in Nebraska are the tailwaters of large reservoirs. Fish congregate there, again because the dam constitutes a barrier to upstream movement, but also because of the abundant food they provide. Baitfish that plunge through the spillway from the reservoir above are often stunned or crippled, making them easy pickings for big catfish, walleye and other predators and scavengers.

Inlets have always been favorites of fishermen "in the know". Among these is Ron Meyer of Lexington, who runs a bait and tackle shop on the road leading to Johnson Lake. Meyer has fished all over the U.S., but the Tri-County canals and reservoirs have been his home fishing grounds for about 15 years. And since his business hinges on fishing, he's made it a point to learn the secrets of the local waters.

Meyer fishes at the inlets and outlets most of the time, going after walleye, white bass and catfish. But he also takes a few largemouth bass and walleye at the diversions, and catfish where the canal water re-enters the Platte.

"The Johnson Lake inlet is probably my favorite fishing spot, and June is about the best time. The white bass are in the middle of their spawning period, and the walleye are just finishing theirs," Meyer said.

"I use medium-weight spinning gear and line no heavier than 6-pound test when fishing for walleye or white bass. The best lure is a jig. When I go after catfish, I switch to a heavier outfit with 20-pound test line, and use shad or cut bait."

According to Meyer, the manipulation of water level influences fishing more than weather or other factors.

"Fishing is best when the water level changes rapidly, either rising or falling. It ends almost entirely when the flow reaches its peak and the water gets murky, and is real slow when the water is low."

Another good time to fish the inlet is spring, sometime around April. Meyer ties two jigs on his line, one about 18 inches above the other.

"I let this rig sink all the way to the bottom, then use a slow, steady retrieve. The most effective jig for me has been a Vs-ounce red-yellow-green pattern, or one that's black and white. Sometimes this tandem setup is the only method that will take fish."

Meyer's catfishing tackle includes a heftier pole and 20-pound-test line to handle the heavy weight needed to hold the bait in the current where the big cats lurk. In swift water at the inlet, this might require as much as V/a ounces of lead.

He now uses rather conventional still-fishing methods for catfish, but he tells of another that some times provided hot angling years ago. It involved a float which could slide freely up and down the line, and enough weight to carry a gob of worms to the bottom.

The rig was cast into swift water at the inlet, and enough line was released through the float to let the bait reach bottom. Then, by taking in just a little line, the fisherman could let the current carry the bait along, tantalizingly close to the bottom-hugging catfish. By constantly checking the depth and adjusting for changes, a catfisherman could walk along shore, following his rig while it effectively covered a large part of the most productive water.

Today, however, such outfits are seldom used. "There are too many people fishing there most of the time these days. You could only let your float travel a few yards before it hangs up on some still-fisherman's line," Meyer said.

Meyer sometimes fishes the outlets below power houses and just below the canal's outlet into the Platte.

"I use the heavier gear there, and use minnows almost exclusively for bait. In the river, especially, minnows are about the only thing that works, while shad and cut bait seem best for most of my other catfishing, such as at a lake's inlet."

While walleye, white bass and catfish share Meyer's attention, catfish are the nearly exclusive target of anglers along another man-made fishery in Nebraska, the Loup Power Canal. One of these fishermen is Ralph Schmidt, who works at the power plant on the canal near Monroe, and who has fished the canal for over 20 years.

"Some of the equipment you see being used here is a lot heavier than you'd find in other parts of the state," Schmidt said. "But the heavy gear comes in handy because the current is swift and the catfish here get pretty big." Another reason for the heavy gear is a multitude of snags, especially where the canal has been stabilized with rock rip-rap and cement-filled tires.

It's not unusual for fishermen to use a big Calcutta rod, which Schmidt describes as "something like an overgrown cane pole with line guides." These are fitted with deep-sea reels loaded with 50-pound-test line and tipped with at least four ounces of lead, a big hook, and a king-size helping of bait.

Usually, the bait is a big minnow, but small sunfish, crawdads and frogs also work well. One of Schmidt's favorites is a small sand toad, especially when he goes after cats with bank lines.

Usually the weight is put at the end of the line, with the hooks on "dropper leaders" above the weight. Others use slip sinkers, which allow line to pass through the weight so the fish doesn't feel resistance when he runs off with the bait. The closer to the center of the canal these catfishermen can put their offerings, the better they like it.

Schmidt agrees with Meyer on the importance of water level. "When the water is coming up, the fishing gets good. But, when its all the way up, the fishing's over," he says.

The outlets of the two powerplants on the canal are probably the favorite angling spots, and for good reason. These areas attract lots of fish, and the biggest ones in the whole system seem to be among them. Schmidt can testify to that, having retrieved a 79-pound flathead cat a few years ago that was trapped in the trash racks.

He feels that the fish are attracted by stunned and crippled baitfish that come through the plant's turbines, and also by the richly aerated water that the turbines createe.

"The plant at Monroe is probably the better of the two, since it operates almost constantly. The plant near Columbus (Continued on page 44)

Selling Safety

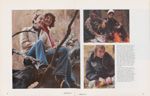

Thus far, 611 volunteer instructors have certified over 3,000 residents in the proper procedures for the field

ON SEPTEMBER 1, 1972 the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission took on an additional responsibility —one that will continue to grow in importance each year. This new endeavor is known as the Nebraska Hunter Safety Program. As of January 1, 1974, 611 voluntary hunter safety instructors had certified 3,000 Nebraska Safe Hunters. There were approximately 400 additional youngsters who received hunter safety training, but who could not be certified due to a minimum-age require ment. Students must have reached their 12th birthday by the end of the calendar year in which the class was taught in order to be certified.

The 611 Hunter Safety instructors throughout the state received their certification by attending classes which were conducted by conservation officers. Officers have worked with individuals, civic and outdoor groups, and many schools. The most active area of school participation has been the Lower Platte North Natural Resource District. Al Smith, manager of the District, has been most influential in getting the Hunter Safety program introduced into the schools throughout his area.

The outstanding instructor in the state the past year was Keith Kyser of Alliance, who certified 200 students. All those interested in the shooting sports owe a debt of gratitude to men like Keith who have volunteered their time to the Hunter Safety program.

Individual efforts through the past year were not confined to the men, however. An outstanding job of instruction has been done by Jan Bohaty of Bellwood, who held several classes in the Columbus, Schuyler and David City areas. She has worked through schools, Boy Scout groups and even conducted hunter safety classes for a National Guard unit. Several other women have been certified and have been active in their respective areas.

In looking at this past year's computerized data, it is evident that a large percentage of students certified were exposed to the Hunter Safety course through their school systems, primarily because a school's hunter safety classes are more readily accessible to that age group. Individual instructors some times find themselves in a bind when organizing a class. They may find it difficult to obtain a place to hold classes, or may experience difficulty acquiring classroom aids such as slides or movie projectors. Because of these obstacles, they are often discouraged from initiating a class. It is also necessary that potential students know of the existence of a Hunter Safety program and instructors in their area before interest can be generated to start a class.

We have attempted to make the teaching of hunter safety as convenient as possible for all the instructors, but it is easy to see that teachers (by profes sion) have an advantage. They have the facilities at hand —the classroom, the blackboard ind the visual-aid equipment, such as the slide and movie fa cilities. Mini-courses and physical education periods have been ideal times for the hunter safety course. And, an already established classroom rapport with students is also advantageous to the teacher.

The Nebraska Hunter Safety program is not complicated but can be highly effective. Anyone 19 years of age and older who is interested in becoming an instructor should contact his local conservation officer. Classes involve eight hours of instruction, normally given in two separate sessions. All instructional materials are furnished by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission free of charge.

Student classes take a minimum of six hours, in at least two separate class room sessions. This time is spent on the following topics: Responsibility in hunter safety; game laws and game management; knowledge of firearms and ammunition, and safe gun handling and storage. Stressing hunter ethics, or good behavior in the field, is a mandatory and increasingly important part of the instruction.

When the student is certified, he receives from the Game and Parks Com mission a billfold identification card and a State of Nebraska "Safe Hunter" patch. Instructors also receive cards and patches.

All information from the identification cards, both student and instructor, is recorded on computor. Thus, a permanent record of each completion is established. With more and more states going to mandatory hunter safety programs, this factor becomes important to the Nebraskan who wishes to go hunting out of state. For example, Kansas and Colorado have mandatory programs, and both honor a Nebraska certificate. But, prior to purchasing a non-resident permit there, hunters must provide proo( that they have successfully completed a Hunter Safety course. In the event of a destroyed or lost Nebraska certificate, the computor makes replacement a push-button operation. Quickly, replacement identification number and certificate are provided and you are on your way.

Although instructors are becoming more evenly distributed in the state, there are still some void areas. In most of these areas, the reason is simply a lack of awareness that the program is available. Once an active program is begun in a community, interest is generated in surrounding areas.

In an effort to eliminate void areas, the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission's Information and Education Division, with the cooperation of the state's news media, is going to sponsor a campaign to promote awareness of the Hunter Safety program. Our purpose will be to encourage statewide participation at both student and in structor levels.

This year, March 17 marks the beginning of National Wildlife Week. Because Nebraska's Hunter Safety program stresses a deeper respect for the out-of-doors and for wildlife, it is only natural that this week of observance be used to emphasize hunter safety train ing. Hopefully, National Wildlife Week will spark many training programs for both students and instructors.

It is evident that the most effective statewide educational program that will improve hunter attitudes is the Hunter Safety program.

The very future of hunting depends upon more appreciative, respectful participants. We must insure this hunting privilege by educating the coming generations of hunters in the ethics and responsibilities they shoulder along with their guns. There is no better way to do this in our state than through the Nebraska Hunter Safety course.

Sicklebill!

THE WIND in mid-March is not yet kind, and the potholes and lakes throughout the Sandhills lie strewn about like bones of the former summer. The valleys are vacant of song; no fragrance rides this wind; no motion save the stooping of old grass. Over and over the wind repeats its whisperings in dry grass, dead stalks, open sand —the stiff, monotonous voice of a winter-suffered land.

Here and there a horned lark skips across the ground, uncrouching from months of this long ordeal. In the shadow of a distant slope a coyote noses snow for mice, impatient with hunger. But the land belongs to wind, and the mule deer which stands like a statue on the farthest, tallest hill regards a desolation most profound.

But then one day the sun is somehow different, the shadows less total. The wind becomes confused, gusting at times from the south, erratic and insincere, but blunting the knife-wind of the north.

A shape will be seen some afternoon on the crest of a low hill amid the ragged flags of last year's grass. Grouse like, it will stand for a moment motionless and erect, then disappear into the contour of the ground. Suddenly, five birds will spring into the air, fantastically long bills agape with alarm, and slide quickly into a sidelong line, slipping over the hills and away.

That is the passing front of spring in the Sandhills, the leading edge of the storm gathering to the south, and the ranchers know the sign. For soon after the sighting of a sickle bill, the scattered green that spots the wetlands will spread out and upward to the hills, infecting all the land.

That first glimpse of the long-billed curlew, and the loud, ringing notes of its cry, remain stirring in your mind long after the bird has gone. You try to imprint that voice-the call of Spring itself-but to such a task the memory is help less. You must hear it again and again.

In March the uncertain sun brings into the Sandhills strong wings and this cry: "The Sicklebills are in!" 14 NEBRASKAland MARCH 1974 15

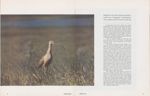

By mid-April, most of the curlews have moved into Nebraska. They arrive in small flocks, remnants of the once great wedges which broke the winter silence of the prairie and plains. When the white man came west, so came the guns, and the curlews, like most of the plentiful birds, suffered. The Eskimo curlew, a smaller relative of the longbill, fell to extinction. This following account, from a report is sued by the Committee on Bird Protection, describes an episode of the spring migration:

...But the greatest killings occurred after the birds had crossed the Gulf of Mexico in spring and the great flocks moved northwards up the North American plains.

These flocks reminded the prairie settlers of the flights of passenger pigeons and the curlews were given the name of "prairie pigeons." They contained thousands of individuals and would often form dense masses of birds extending half a mile in length and a hundred yards or more in width. When the flock would alight the birds would cover 40 or 50 acres of ground. During such flights the slaughter was almost unbelievable. Hunters would drive out from Omaha and shoot the birds without mercy until they had literally slaughtered a wagon load of them, the wagons being actually filled, and often with the side boards on at that. Sometimes when the flight was unusually heavy and the hunters were well supplied with ammunition their wagons were too quickly and easily filled, so whole loads of the birds would be dumped on the prairie, their bodies forming piles as large as a couple of tons of coal, where they would be allowed to rot while the hunters proceeded to refill their wagons with fresh victims.

The compact flocks and tameness of the birds made this slaughter possible, and at each shot us ually dozens of the birds would fall. In one specific instance a single shot from an old muzzle-loading shotgun into a flock of these curlews, as they veered by the hunter, brought down 28 birds at once, while for the next half mile every now and then a fatally wounded bird would drop to the ground dead. So dense were the flocks when the birds were turning in their flight that one could scarcely throw a missile into it without striking a bird....

16 NEBRASKAland MARCH 1974 17

Perhaps because the longbill proved not as delectable, or not as unwary, it escaped the fate of its cousin.

But with man also came agriculture, and by the 1930s, the longbill, along with many other shore birds, was pushed to the brink. Yet the bird persists, thanks largely to the open ranges of grazing land.

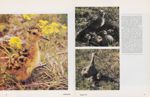

A giant shorebird, the long-billed curlew (Numenius americanus) attains a weight of over two pounds and possesses a wingspread of up to 40 inches. The sexes are alike, but the female is usually larger, with a longer bill. The bill may be over 8 inches long; when not feeding on berries or insects, the bird uses it to probe deeply into wet sand or mud, hunting grubs, worms and crustaceans.

Since curlews generally prefer dry highlands for their nest sites —often a mile or more from water — they are forced to feed at this time on grasshoppers and other available insects, deftly plucking them up from the grass as they walk along.

Usually shy and secretive, the curlews become noisy and conspicuous during courtship or when disturbed on their nesting grounds. Having staked out a territory, a pair will engage in aerial courtship displays, often interrupting feeding to sail upward to gether, calling loudly, then glide back to earth on set wings.

Nests are simple depressions in the sand, lined with grass, large enough to hold the usual four eggs.

Once egg-laying has begun, curlews become outspoken defenders of their territory, rising from the ground with wild alarm at the first sign of intrusion. Should the trespasser persist, moving in the direction of the nest, the birds become progressively more frantic. The male, especially, exhibits aggression, boldly challengingthe intruder with high-speed dives.

Should the hen be incubating, she will not flush at the approach of danger but crouch low over the nest, relying on camouflage for protection. So effectively does the bird blend with its surroundings that detection is extremely difficult, even at close range.

Because this urge to remain on the nest is strong, the bird, if approached cautiously, can even be touched. If flushed, it will burst away in a fluttering run, feigning a broken wing to draw the surprised attention of the intruder away from the location of the nest. Coyotes are led off in this manner, the bird managing to maintain a discrete distance from its pursuer. (Continued on page 23)

18 MARCH 1974 NEBRASKAland 19 "I can remember old fellows speaking

feelingly of an evening spent on the

big empty plains. It had taken the

shrillness out of them. They had

learned the trick of quiet "

Sherwood Anderson

"I can remember old fellows speaking

feelingly of an evening spent on the

big empty plains. It had taken the

shrillness out of them. They had

learned the trick of quiet "

Sherwood Anderson

After a month of jealous parental care, in which the adults have attacked passing hawks, the eggs hatch. Since incubation starts only with the laying of the final egg, the chicks hatch within a matter of hours of one another, an important factor in their survival.

To protect their new brood, the adults redouble their efforts, nervously patroling the surrounding territory. By this time most of the other birds of the region are just beginning to settle down to the quiet business of incubation, but the peace which has returned to the landscape is once again shattered by the loud cries of curlews. A single alarm note will send several males into the air, a single intruder draw ing a distressed company of birds from all the adjacent territories, the air ringing with their complaint. The determination of the male to protect the brood becomes frantic, his fury vented in Kamakaze-like attacks, coming in fast, scolding flights which are broken off only a second before collision. So persistently are these attacks pressed, the bird soon be comes hoarse and exhausted.

Nature has bestowed upon many ground-nesting birds two important gifts to offset the months of trial egg and chick must endure to survive their exposure to the ground's host of predators. One is the coloration of the egg itself, making it difficult to see in its surroundings. Secondly, the chicks are precocial: their strong legs, sharp eyesight, and coat of warm, camouflaged down helping the birds quickly adapt to their severe world. Within hours of hatching, they are mobile, capable of feeding on their own, and responsive to the commands of their parents. This self-reliance, plus their ability to "disappear" in the grass, permit enough of these "downies" to survive their flightless weeks to insure the species.

Perhaps more than any other creature of the plains, the curlew embodies the spirit of an open land. More than its audacious bill or the sight of it rising to hover above the earth, is the quality of its voice, a clear, long, inexplicably lonely curl-e-e-e-u-u-u, a cry which is like a song of human need sent out into the empty hills.

S.O.S. for wildlife

Game abundance can't be realized in face of habitat destruction

HABITAT IS a place where a plant or animal species naturally lives and grows, and even such a short definition holds the key to perhaps the single most important factor of wildlife abundance. What effect, then, will the U.S. Department of Agriculture's mandate to farmers "to plow up the fencerows" have on wild life? The push for even greater farm production could mean severe "housing" problems for wild life. Recent declines in pheasant populations, for example, can be attributed in large part to the demise of programs like Soil Bank, with a corres ponding loss of those diverted acres.

In addition to the loss of retired lands, many thousands of acres of generally unused areas are destroyed annually as potential habitat in what are primarily "housekeeping" measures. Such locales include roadsides, culverts, weedy fence rows and the like. Just leaving these basically untillable areas alone would mean much in wild life's struggle to survive and multiply.

Studies by Nebraska Game and Parks Commission researchers show that more than 25 per cent of the annual pheasant crop is produced along country roadsides, and about 10 pheasant chicks are produced for every mile of road. Unfortunately, much of this valuable nesting habitat is mowed or burned each year. Removal of this cover, accompanied by other intensive farming operations, can destroy sorely needed wildlife habitat.

The agri-business manager looking over his farm acreage makes important decisions every day that have far-reaching, and many times adverse, effects on wildlife. At a time when every additional acre under cultivation can bring greater profits, the well-meaning farmer, who would like to provide habitat for wildlife, is caught between the proverbial rock and hard spot.

To increase acreage under the plow means areas such as weed-filled draws and field corners are utilized. Marshes are drained and small creek bottoms and drainages are removed. Even long established shelterbelts are being uprooted to make way for greater cultivation.

Disappearance of long-established wild areas, coupled with the mowing and burning of valuable nesting cover along roadways, means wild critters are the big losers, for without protection, animals perish. What, then, can be done to insure adequate habitat for wildlife?

While every farm and ranch operation is different, there are a number of important steps that can be taken to ease the crunch on wildlife. Individual operators can help by simply not doing normal spring "tidying up" projects, such as burning and/or mowing ditches and other "waste" spots. This is also true of those boards and agencies responsible for maintaining public roads.

The fate of each year's pheasant crop hangs in the balance each year during a few short weeks in May and June. Pheasant hens need this time in an undisturbed nesting site to incubate their eggs. Peak hatching comes during the first two weeks of June, but between the time the eggs are laid and hatched, about 85 percent will be lost. Most of the nests fail because they are destroyed by agricultural operations or pedators.

Almost everywhere, farmers and road crews start their spring working season by performing such "cleanup" jobs as spraying and burning of roadside ditches. A close examination of such operations could show them to be most uneconomical, especially considering the long-term impact of the fuel shortage being experienced in this country.

The Nebraska Department of Roads has real ized major savings by cooperating with the Game and Parks Commission's Acres for Wildlife program, and mowing only up to 1 5 feet of the right of-way. That means some 150,000 to 175,000 acres retained for wildlife —acreage that had previously been mowed twice a year. At a cost of from $3 to $4 per acre, that diverts approximately one million dollars per year for other useful purposes. While safety is an obvious factor, a prime reason for burning or mowing ditches has been to cut down the fire hazard that might exist in a stand of taller grasses. However, experts at both the University of Nebraska and the Roads Department have concluded that the natural stands of unmowed grass would not be as easily ignited as dry mulch remaining on mowed rights-of-way.

Wherever tall stands of grass pose a traffic hazard, they are mowed, but such mowing really isn't a problem, since wildlife nests are generally found between the middle of the ditch and the fenceline.

If roadside ditches and the odd areas that can not be farmed were returned to native grass, both the farmer and wildlife would benefit.

By establishing a good stand of native grasses, noxious weeds such as musk thistle and field bind weed can be deterred. Although it would be impossible to eliminate the taller weeds altogether, stands of native grass require less maintenance, thus saving time and work for the farmer, while also providing cover and food for wildlife.

Grass species such as blue gramma, buffalo grass, western wheatgrass or crested wheatgrass could eliminate the need for mowing roadsides altogether if seeded immediately adjacent to the road surface. Tall fescue, intermediate wheatgrass and switch grass can be used for short-term ground cover where more expensive varieties of grass would be prohibitive.

If field corners and odd, unfarmable acres are plowed but left unseeded, a thriving population of

Prescribed or controlled burning does just that —it initiates the first stages on overgrown and thick stands of grass. However, it is a technique that should be utilized only with management guidance. For the farmer, discing and grazing in certain areas can replace fire as a succession initiator.

If not overgrazed, healthy stands of grass continue to thrive even though cattle use the area regularly. The stability of grass in favorable conditions in the sandhills region is due to wise use of the resource by ranchers who understand that the carrying capacity of the land cannot be exceeded.

Along with native grass, weedy fencerows and brushpiles provide a much-needed wildlife requirement. Brushpiles provide homes and winter protection, and fencerows are natural escape and travel lanes for pheasants and other game.

None of the habitat management techniques need clash with successful farming. The man who leaves grassed waterways and provides brushpiles and weedy fencerows is not violating sound business practice. Eliminating short rows (farming only the long rows) and leaving odd areas to revert to native grass are better techniques for successful farming and will promote thriving wildlife populations.

LEARNING TO LIVE WITH THE ENERGY CRISIS

"I find myself spending time, not killing it, with books and grass and bugs; with kids and sleds and an old cane pole carefully rigged with a grasshopper."

ENERGY CRISIS has gripped the country, and with gas rationing looming, people with more leisure time than ever before are looking for vacation alternatives. The long, extended tour of vast sections of far country becomes more and more an impossible dream, while people jaded by crowding and pressure seek ever more fervently for brief escape from metropolitan areas.

What's the solution? Some people suggest that we all take up knitting. Perhaps that's not a bad suggestion we're all going to need more sweaters if fuel supplies continue to decrease and thermostats are continually turned down.

There are, perhaps, some other solutions which just might provide added depth of perception, and a better understanding of those things close to home. How long has it been since you visited your back yard? No, I don't mean sitting in shirt sleeves on the patio sipping a tall, cool one. That's good, too, but what I mean is really looking at those things you planted there-or should have planted.

Have you ever watched small children playing in the grass? They're likely to sprawl full length on the lawn, absorbed in a single blade. Unfortunate ly, it doesn't take them long to find out that that is a weird thing to do, and they become too sophisticated to look anymore. Remember all those questions they asked, though? They're the same ones you probably asked, driving your parents to distraction because they didn't have the answers any more than you do. Why is grass green? Why does crab grass always get mixed up in the bluegrass? How does grass know when it's spring so it can start growing? How come it doesn't grow in the winter? Where do the seeds come from for the new grass, when we cut it off all the time? Where does the green go in the winter?

Photograph by Greg Beaumont MARCH 1974Have you ever tried to answer those questions? Or do you dismiss them with a mumbled "I don't know"? Not long ago my three-year-old started asking the unanswerable questions, all with a slight lisp and big blue eyes. It almost looked as if he were laughing at me, knowing I couldn't answer him. In a few amazing seconds I looked at that child and at myself, and I couldn't help asking, "but couldn't we teach each other something!" So I answered, "I don't know, but I'll bet we could find out."

Then we introduced each other to questions (which I had forgotten) and to books and libraries. I fail him often. When he asks a question while I'm absorbed in getting dinner, I give him an 'I don't know". But he never fails me. The questions are always ready —and almost always logical, at least after I call my older son in as interpreter. Grand Canyon? We vacation every time I can drag myself up to their level.

I'm a country kid, and it seems as though the shortage of energy might bring Nebraskans like me back to some of the things I enjoyed before I left home. I remember when I couldn't wait for a rain. Rain to me meant that dad couldn't get into the field to work. That almost always meant fishing, and that meant one of two things, depending on the amount of rainfall.

If it rained a little and dad figured on farming the next day, we'd fish the farm ponds on our land. My sister and I were the official "bait dealers". We almost always kept a can of worms in the basement, but we often forgot to supply them with their ration of coffee grounds to keep them alive. It was more fun to catch grasshoppers anyway. We got a little cranky when they spit tobacco juice on our hands, but it was a minor insult.

If it looked like a long drying period was in store, we'd pack up a ring of baloney and a ioaf of bread and head for Harlan County Reservoir (about an hour's drive) and fish there. A blanket on the ground always seemed enough during those long, hot summer nights. I'll have to admit, my sister and I did more swimming and hunting arrow heads than fishing. But we parked near dad's favorite fishing hole, called "Becker's Deep Freeze" after the man who always managed to bring a walleye or two from its depths, just to keep up appearances. It was from those excursions I learned to find the North Star and the big dipper. Seemed important things to know then.

Vacationing in those days required little energy —mostly kid power to dig fire rings and erect a tent composed of an old blanket to keep mid-afternoon sun off people. We didn't even think about survival training, just kind of thought we could get by with a minimum of equipment.

Sometimes we even used Uncle George's "baby boat". He had a tiny motor on it, just enough to get us to the middle of the cove where fishing might be a little better. As kids, we rowed it as much as motored. It was a good chance for George's adolescent sons to show off their muscle power, anyway. Our favorite craft was an old log we floated back into the coves where the boat wouldn't go. The exciting thing about the log was the danger. We never knew when we might be rolled into the waist-deep water.

Perhaps the energy crisis will bring back some of those simple vacations.

How long since you walked down

the street where you live? I always get

the mail on my way home from work. I

just park the car by the post office, walk

in to get the mail, then tramp back to

the car and go home. One day I got

distracted in other errands and forgot

the mail. My older son had been nagging me for some time to go for a walk

with him, so I thought to kill two birds

with one stone. The three of us (my two

sons and I) walked to the mailbox.

Sean was skipping ahead and Jason

29

was holding my hand and chattering

unintelligibly.

was holding my hand and chattering

unintelligibly.

Then I heard them —the gabble of geese. Excitedly, I knelt on the ground and gathered my boys, pointing to the wavering V overhead. It was an interesting experience. We became the catalyst for drawing several families out of their mobile homes to look at geese. Canada? Why not wait for it to come to you?

Winter sports have become popular in recent years, and many, many Nebraskans go skiing in Colorado each winter. A lot of college kids have already discovered one way to conserve energy on those trips. In their case, it was probably financial necessity, but the favorite way to travel is by the carload. It seems nobody goes skiing by himself. Well, that might be an exaggeration.

Another way to enjoy winter sports is right at home. First, find a hill. Some of my friends discovered I had one right behind my house, and the festival began. Sleds had waned in popularity by then so no one had one, but being inventive, the group found plenty of scoop shovels. "What you do," they told me, "is sit in the scoop, lean back against the handle, and have someone shove you off. If you fall off, you haven't far to fall." It's been a long time since I heard such a bunch of community whooping and hollering as I did in that winter twilight. Now, I have to admit, we consumed a lot of energy using our novel toboggans. There were a lot of people with stiff muscles the next day to prove their energy expenditure.

If you can't afford a scoop shovel, I suggest you improvise your own snow gear. Many of the stores now have real live toboggans and sleds and snow discs. All you really need is a hill and some ambition.

Nebraskans are probably some of the most fortunate people in the country, though many of them don't realize it yet. How many of us can't be out in the

When my sister and I were kids we used to squish through mud puddles catching tadpoles. There's nothing quite like squishing around like that with the sun shining on your back, and all those tadpoles slithering around in your loosely-clenched fist. One year we discovered that tadpoles grow up to be frogs. The day we finally realized that was really unusual. My sister wanted to know, "If frogs come from tadpoles, do cows come from pigs?" I told her, no. But she pursued the idea — if frogs come from tadpoles, it seems logical that maybe pigs come from tad poles, or maybe horses —or maybe US! Somehow we got a feel for evolution and for fetal development from a mud puddle. The Science Fair? We're all scientists.

How long has it been since you watched something grow? My son has a thing about pumpkins, so one week end we cancelled a trip so we could turn over the sod for a garden plot. We made our hills, and he poked some seeds into them with his own hands. Then we watched. We'd go out there every day to see if they had sprouted. We even talked to them-lovingly. Trailer lots are not overlarge, and soon my whole yard was overgrown with pumpkin vines. But we had pumpkins. Took another weekend to prepare them for the freezer, but oh, the pumpkin pies! My son? He learned what it means to eat a pumpkin pie. Maybe that's as important as learning how frequently Old Faithful blows off.

But perhaps you need to REALLY get away. I remember when we were kids. We used to pack as many bodies as possible into a car and go swimming, or roller skating, or dancing, or to a movie. Anyone who went alone or as one of a couple was either a snob or in love. Ron Kurtzer of the Sierra Club tells about an outing he had with a bunch of other club members. They packed three canoes on the top of their car and about six people inside, and they spent a few days away from jobs and pressure.

I've got a friend who likes nothing better than taking several canoes, a couple of guitars and camping equipment in and on his auto and taking off with a group of friends to the river — any canoeable river. I don't think I know anyone who has more fun on his vacation. And I don't think I know of anyone who has gone along without putting in his bid for the next trip.

I guess the foregoing doesn't contain much in the way of tips for conserving energy while you take your vacation. Those tips can be summed up as follows: slow down, use fewer pieces of equipment which require power use, stay closer to home, use public transportation-buses and trains. Ride a bicycle rather than a motorbike, paddle or sail rather than motoring, ride a horse rather than a camper.

I reckon what I'm suggesting is that you might not really need to travel far from home at all. I'm drawing upon a few very pleasant moments from my own recollection, and all the things happened within an hour's drive from home. Anyone can improvise his own good moments from the raw materials around him —mostly leisure time and friends. Nebraska is full of parks, recreation areas, and wildlife areas. I'll wager many of you have never seen them.

What I'm suggesting is that anyone can engineer a fantastic vacation for the whole family— out of nothing but a whimsical imagination. If you can't seem to do it, ask a kid. He'll think of something.

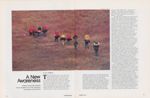

A New Awareness

Outdoor encounter program moves students out of the classroom into natural environments

THE WIND BLEW sand in quiet swirls that gently attacked my face and hands. The panorama of sandhills and pines spread before me and let my mind float gently downstream. The tidal wave of solitude crystalized my plans and I knew that the stage was set and ready. In two weeks, Dick Nelson, a group of high school students and I would be exposed to a new awareness, new experiences and a lifestyle different beyond our wildest expectations. We would back-pack, camp, eat and just plain live together for eight days in the more remote areas of Halsey National Forest. We would encounter the outdoors on its own level and would encounter ourselves and the group on many levels. The purpose of such a program? Simply to allow the participants to become more aware of their total environment. To foster understanding and caring within the group. To see the natural world in all of its varied simplicity in order to formalize good attitudes concerning the total environment. To have a good time and mellow out, or as one student put it..."just get it all together." One could say that the outdoor encounter would be a tool to be used by all those involved in order that we could see... believe...and realize.

The idea for the outdoor encounter program started in the Game Commission's Education section. Dick Nelson, Conservation Education Coordinator, and myself were just talking of how we could, as a Game Commission entity, best reach and serve the high school students of Nebraska. Education is our major emphasis and we feel that public schools are a good "common denominator" when dealing with youth education. It seemed to both of us that what we should offer the high schools in the way of conservation and environmental education should be a little different—innovative, and an alternative to traditional educational methods. One thing led to another and it came on us like a hot flash! What better way to learn about the natural environment and the outdoors than to experience it? What better way to learn about "human ecology" than to live as a group for a prolonged period? So the idea gradually took form and after much talk, we decided that the Game Commission should offer the schools an alternative way of learning for their students. We would combine several aspects of such outdoor experiences as Outward Bound and National Outdoor Leadership School, along with some of our own ideas, and would offer an outdoor encounter in the form of an eight-day backpack in a substantially wild area, in this case, parts of the Halsey National Forest in north-central Nebraska. We would assess this first venture and if all went well, would implement the program as an on-going project in both the GameCommission'sand public school's structures.

The makeup of an outdoor experience such as this is mind boggling. The logistics alone would terrify any sane individual. Despite all of the hassles, we proceeded to tie up all the loose ends and were finally on our way! The first day proved to be bright and warm. After shouldering our packs and saying final goodbyes to the civilized world, we began our trek across the hills in the southeast corner of the forest. We entered a world of packs that spoke in creaking language, and of wind that provided an "internal' rhythm in your mind. We were suddenly a part of an avalanche of silence that kneaded our whole beings. It seemed that everybody was just kind of adjusting their "mind set" in order to deal with the coming week. We hiked too quickly, as far as I was concerned, and possibly missed much as a result. But, I thought, "Whatever, we've got a week, why make 'appointments' so

32 NEBRASKAland MARCH 1974 33

soon?" Everyone seemed to need to walk fast. We reached a spot on the Dismal River late in the afternoon and set up camp behind a sheltering group of trees. Camp chores ranged from patching up blisters to setting up tents in the sand (a lesson in frustration and the acceptance of futility). Camp was finally respectable and we settled into our "ritual-to-be" of grouping together after supper and just plain getting it straight. I'm sure that the discussion that evening solved at least nine world problems and paved the way for future crisis solving.

We turned in that night after contemplating the milky way, along with other celestial and terrestrial mind bogglers. Some of us decided to brave the threat of rattlesnakes and sleep out on the open sand (rattlesnakes were a danger to be considered at the time. The Forest Service warned us of the unusual number of snakes around that year. I was struck at twice during my reconnaissance for the trip, once when I frightened a big prairie rattler that tried to curl up to the warmth of my ensolite pad for a night's sleep). We all slept that night away without experiencing any significant occurrences, however.

The days passed, some being times of dry windmills and miles of waterless hiking, some being times of meaningful reflection and introspection. As I watched our progress, it became evident that we had come a long way from the first day, both as an efficiently working team of backpackers and also as "real people." We became attuned to the sound of the outdoors. We talked with each other openly and interacted with nature on its own level. We were more

We not only experienced as a group but as individuals. One of the more meaningful experiences was what we called "solo." Supplied only with a plastic tarp and sleeping bag, each participant was placed in a different area of the forest separated from everybody and everything for two days. Company consisted only of pine trees, sky, ground and an occasional coyote howling in the night. I think that we all learned something about ourselves and our place in the world in those two days. Dick and I checked on the students once a day and spent what portion of the day that was left eating granola cereal and talking. That night I didn't sleep well. Kind of like losing touch with close friends who are out all night, you see.

To try to explain what happened in that one week is like attempting to quantify a thing like emotion, or explaining beauty and cosmic reality in 30 words or less. The week was full of learning —reality learning and education. Presently, much of education is bogged down in accountability and evaluation. In this experience, all questions of accountability were answered by that quiet yet vibrational smile that was a part of all participants. We experienced a change, all of us. We saw, believed, realized and became. I'm sure we all will remember the quiet lessons of nature, and that's about all that one could ask, isn't it?

Prairie Life / Animal Territories

BEFORE THE LAST of winter's snow has melted from the north slopes of the grass lands, a male meadowlark returns from its wintering grounds in the south. From the same song posts he abandoned the previous October, he announces his arrival. Soon he is joined by rival males and the meadows ring with their songs.

For the meadowlark, this is no song of joy or melody performed for our pleasure. It's not even a love song for the females soon to arrive. Rather, it is a hostile threat issued to other males to stay clear, that this territory is taken.

As the days grew longer and the breeding season approached, the male had undergone a remarkable change. The drab, gray-brown bill of winter was now a striking blue black. His yellow breast appeared brighter than before and his singing became more frequent and intense. More and more he fluffed his plummage and postured with his bill pointed upward, his wings and tail spread. If neighboring males ventured too close they were driven away by a blitzing aerial attack.

For the meadowlark and his mate, this elaborate ritual will assure them 20 to 25 acres of grassland in which to feed, mate and rear young. Through this complex arrangement of visual and vocal displays, the meadowlark establishes his realm with never once resorting to actual fighting.

The concept of bird territorialism is not a new one. It can be traced back to the time of Aristotle (350 B.C.) who noted that "Each pair of eagles needs a large territory and on that account allows no other eagle to settle in the neighborhood."

Since that time, numerous definitions have been put forth to describe animal territories. Though some are lengthy, and qualified to cover specific examples, all have two ele ments in common; the compulsion of an animal to occupy space and to defend that space against other members of the species, excepting the mate. A concise yet workable definition is, "any defended area."

A common feature of most territories is that they are defended most often and energetically against members of the same species and sex. As one zoologist phrased it, "A robin's worst enemy —his greatest competitor—is not a hawk or a cat. It is an other robin which seeks from the environment exactly those kinds of food, those nesting sites, and that kind of a mate, that all robins seek."

The territorial instinct probably did not evolve to meet any one need; rather it was tailored to fulfill specific requirements in different species. Perhaps a territory's most common function, though, is in isolating animals from others of their kind. Once established, a territory provides a place where the male is unchallenged in his courtship activities. Less time is spent competing with other males. Later, the mates have a base where they can continue their courtship rituals, nest or den, and rear their young. With the territory providing the basic require ments of life, individuals can give their full attention to the delicate process of reproduction.

Another advantage of maintain ing a territory is that animals have a complete familiarity with their surroundings. A minimum of time and energy is expended in finding food or nesting materials, and escape routes are well known should predators threaten.

Territoriality not only benefits the individual but is of a long-term advantage to the species. Dispersion of individuals over all of the suitable habitat insures the most efficient use of food, nest sites and the other requirements of life. It seems plausible, too, that by avoiding a concentration of animals in one area, the opportunity for disease to prosper is reduced. Should some pestilence break out in a particular species, the number affected would probably be small. Also, when the individuals of a species are spread thinly, the loss to predation is lowered substantially. In a way, territoriality is nature's way of not putting all her eggs in one basket.

Likewise, any behavioral mechanism that encourages, in fact de mands, dispersal of individuals is of an evolutionary advantage to the species. Animals pushed from their optimum range by territorial disputes are forced into nontypical habitats, where, to subsist, they must utilize different foods, nesting conditions or climate. Some, albeit few, may possess the adaptations necessary to exploit the new range and thrive. Such is the way that new lands were first occupied throughout evolutionary history, and new species split from old.

To be precise, there are probably as many types of territories as there are number of territorial animals. Though breeding territories are by far the most common, animals defend space for almost every reason imaginable. Most, though, fall into several generalized types. Seven have been described for birds but they can be applied to other groups of animals as well.

Territories used for mating, nest ing and feeding are probably the most common. Under this arrange ment all of the life functions are performed on the territory. This type is characteristic of most passerine birds, such as flycatchers, shrikes, blackbirds and sparrows.

Some territories are used only for mating and nesting. Food is generally obtained outside of its perimeters. Many birds of prey establish this type of a territory. Eagles, for example, defend the air space in which they conduct their nuptial flights as well as the area immediately around their nest site, but may feed miles away.

Some animals, like members of the grouse family, maintain areas for courtship displays and mating. In the case of sharptail grouse, males congregate on a common display area but vigorously defend a small piece of those grounds against other males. When females visit the grounds and are sufficiently wooed by the displays, they will mate with the most successful sharptail male on his territory.

A fourth type of territorial be havior is found among species that defend only the immediate area around their nest. This is character istic of colonial nesters, like many Arctic sea birds, or wading birds like the great blue heron. The size of these territories is small, sometimes

only the distance that one bird can

strike at another.

only the distance that one bird can

strike at another.

Three other types of territories have been described for a relatively few species of birds. Some birds, like the red-headed woodpecker, maintain winter territories. In the case of this woodpecker, the territory encompasses an area where nuts or other seeds are stored in tree cavities. His winter larder is not only defended against other wood peckers, but also would-be thieves of other species like the bluejay.

A few species of birds are known to actively defend feeding territories. For example, birds that fish for food, like the kingfisher, claim a section of river or lake shore as their own and refuse to share it with other fishing birds.

Still other species maintain roost ing territories. Starlings are known to use the same roosting perch every night and dispute with any other starling that tries to claim it.

When first presented with the concept, it is far too easy to think of a territory as simply a spatial lump of land, randomly staked out and defended by an individual. Rather, researchers have found their size and shape to be determined by what is available within them. They are, in effect, shaped by the animal's biological requirements and by the occurrence of these requirements within the habitat.

This means that a feeding, mating and nesting territory established by a loggerhead shrike must contain an abundant supply of insects, an elevated point for displaying and a suit able nesting site. In a theoretical example, his territory could conceivably be in a triangular shape

The shape of an animal's territory is also influenced by the topography and other features of the environment. Generally, a territory is rough ly circular, but if it adjoins some natural feature of the landscape, such as a river, it may take on an elongated shape. Even in cases where topography is not a consider ation, territories take on irregular shapes as boundary lines are constantly being pushed and bent by rivaling neighbors.

Among birds, territories not only possess width and depth but height as well. The level at which a bird feeds, sings or nests stratifies territories in a third dimension and expands the number of species that a particular environment can support.

Territory size, like shape, varies widely among different animals. At the beginning of the breeding season, territories are generally large, but once competition grows keen they are hacked down to the maximum size that the owner can effectively defend.

The primary requisite of a territory is that it must be large enough to meet the requirements of the owner. It follows, then, that feeding territories would increase in size with food scarcity and decrease with food abundance. It could be said that territory size is responsive to the holder's needs.

As a general rule, the larger the animal the larger the territory it requires to secure a living. A single golden eagle may require as much as 35 square miles of Pine Ridge grass land to meet his food requirements, while some songbirds on the Missouri River bluffs have territories of only one-third acre.

Though territorial behavior is best studied among birds, breeding territories are common among mammals and fish, and occur with regularity among amphibians and reptiles. Rarely do insects or other invertebrates maintain territories.

Whatever the animal group, breeding territories generally have the same basic pattern. As a rule, the males will establish themselves early in the breeding season and defend their areas by display and at tack. Females rarely establish territories but rather visit the male's.

Some studies suggest that territorialism commonly exists in the deer family, especially the elk. Unlike birds, their territories are not defended by the ritualized displays of rivals, but rather are marked by "sign posts," saplings that have bark scraped off and rubbed by the muzzle. These sign posts serve to identify the territorial boundaries in the owner's absence.

In the canine family, these sign posts are commonly marked by scents secreted into the urine. Posts are maintained throughout the individual's home range and serve warning to others of the species that they are trespassing. Members of the cat family are likewise believed to defend hunting and perhaps breeding territories. Other research indicates that mammals such as the cottontail, chipmunk and squirrel may defend certain portions of their home range.

Among reptiles, territoriality is not uncommon. The spotted lizard of Nebraska's sandhills lives in guarded home ranges. An astute observer can readily locate and define the do mains of individual lizards. Many snakes are likewise known to have well defined hunting territories.

The establishment of territories is well documented in many species of fish, especially during the spawning season. Male bass, bluegill and crappie, for example, defend nests or "redds" within a common spawning ground. Females later visit these areas, lay their eggs and then leave the defense of the nest to the male. Many species of predacious fish defend feeding territories throughout the entire year.

One of the most advantageous as pects of territoriality in an animal species —be it a mammal, bird or animal of another class —is that it is a natural regulator of the population size. When all suitable habitat is claimed, the excess individuals generally do not succeed in breeding, or sometimes do not even survive. Because of this self-regulatory nature of territorial animals, they seldom over populate. Rather, their numbers cease to expand beyond the point at which the environment can no longer meet all their needs.

After summing up all the advantages of tern*- al behavior in animals, one zoologist said, "the surprising fact is not that animals own real estate, but that, consider ing the numerous benefits of territory, some species are able to get along without it."

FISHING MAN-MADE WATERS

(Continued from page 11)shuts down periodically," observes Schmidt.

Besides the power plant discharges, other promising fishing features in the area in clude bends in the canals, where Schmidt says a variety of deep and shallow water is offered. Other favorites are siphons, where lighter rigs, smaller minnows, and occasional artificials will take crappie and white bass.

Yet another productive structure on the system is the Loup tailrace, where the canal empties into the Platte River below Columbus. There, anglers have success with a variety of equipment. Artificial lures are used more often, and the catch includes walleye and sauger as well as catfish.

No rundown of man-made waters in Nebraska would be complete without men tioning the Gavins Point Dam Tailwaters in the northeast corner of the state. It is the most popular spot of this type in the state, and it offers the widest variety of fish and fishing methods.

Lee Rupp of Norfolk, the Game and Parks Commission's fisheries management supervisor for northeast Nebraska, has observed angling patterns below the big dam.

"April, May, September and October are probably the best periods for white bass, walleye and sauger fishermen. I'd bet that 90 percent of the fish are taken on bottom-fished minnows. A rocky area about one-quarter to one-half mile below the dam on the north shore is particularly good for sauger in the spring. There, a floating-diving Rapala or similar lure is most effective, particularly in the evening, jigs are not used much in the tailwaters because they hang up on the rocky bottom so easily."

In June, catfishermen score well using an

44unusual maneuver with their boats. They chug up into the powerhouse discharge channel as far as they are allowed, then cut the motor and toss out lines baited with shad gizzards or frozen shad. The strong current then carries the boat downstream over the best catfish water, with their lines in tow.

"It looks like the current carries the boats too fast to be effective, but the catfish don't seem to care. The method sure works," Rupp says.

In the summer, fishermen also take carp by the sackful, especially a bit farther down stream in eddies below the confluence of the powerhouse and floodgate discharge channels. Doughballs, corn and worms work well. Drum are also taken in great numbers. Small crawdads are the best bait, and the best area is just below the flood-gates.

In another part of Nebraska, a man-made feature offers a tempting alternative when fishing wanes on one of the state's major impoundments. At Harlan County Reservoir, many fishermen head for the area below the dam when things get slow on the lake, and some prefer fishing the spillway even when things are going well up above.

Water plunges from the big dam's gates with incredible force, so the engineers built a concrete-lined "stilling basin" more than 16 feet deep at the outlet to absorb the water's fury. Also in the basin absorbing this punishment, as well as the tons of stunned baitfish that pour through the gates, are hefty catfish, walleye and white bass.

A series of platforms have been installed along the downstream edge of the stilling basin, and anglers can wade out to them and fish in comfort. These handy perches allow fishermen to park themselves and their gear comfortably out of the water, yet within easy reach of the best fishing. Just a few feet from the platforms, a cable marks the dropoff into the stilling basin, and no smart angler ventures beyond that cable. But as a safety precaution, the Corps of Engineers requires that all fishermen there wear life preservers.

Don lllian of Republican City, operator of a local bait and tackle shop, has fished the reservoir and spillway ever since his boyhood some 25 years ago.

According to lllian, the catfishing is good in the spillway from spring through fall. The standard catfishing outfit there consists of a medium-heavy baitcasting rig filled with 20-pound-test braided nylon or monofilament line. It takes plenty of weight to anchor a piece of bait in the boiling turbulence of the basin. Illian's line is usually equipped with a 3-ounce slip sinker and a 2/0 hook.