NEBRASKAland

February 1974 50 cents 1CD 18615

NEBRASKAland

VOL. 52 / NO. 2 / FEBRUARY 1974 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Fifty cents per copy. Subscription rates $ 1 for one year, $6 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. commission Chairman: William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Vice Chairman: Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-central District, (308) 452-3800 Second Vice Chairman: James W. McNair, Imperial Southwest District, (308) 882-4425 Jack D. Obbink, Lincoln Southeast District, (402) 488-3862 Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-central District, (308) 745-1694 Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 Director: Willard R. Barbee Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, Jr. Assistant Director: Richard J. Spady staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: Ken Bouc, Jon Farrar, Faye Musil Photography: Greg Beaumont, Bob Grier Layout Design: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: C. G. Pritchard Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1974. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Lame and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska Travel articles financially supported by Department of Economic Development Ronald J. Mertens, Deputy Director John Rosenow, Travel and Tourism Director FEBRUARY 1974 Contents FEATURES CAMP-OUT AT SOLDIER CREEK PADDLEFISH WHAT ABOUT TOMORROW? 12 SNAKE RIVER IMPRESSIONS 14 PLATTE VALLEY SPECIAL 18 A SUMMER REMEMBERED 36 LEARNING TO CARE 38 PRAIRIE LIFE/MIGRATION 42 DEPARTMENTS SPEAK UP TRADING POST 51 COVER: Surrounded but not caught in winter's grip, Snake River Falls creates frosting on adjacent trees. Photograph by Bob Grier. OPPOSITE. Always severe in appearance, the skeletal formations at Toadstool Park seem an appropriate setting for the rigors of winter. Photograph by Lou Ell.

Speak up

He Has PhotosSir / I would like to respond to a letter in the November 1973 issue of NEBRASKAland from Mrs. B. K. Kruse titled "No Chicken Photographs".

First I would say that although Mrs. Kruse is obviously anti-hunting and anti-hunter, I certainly respect her right to feel this way and give her opinion as she sees them. I do feel, however, that since she has given her opinion I too should have a right to mine.

I am proud to say that I am one of the sportsmen with a high-powered gun, in fact several of them. In your letter, Mrs. Kruse, you say that you object to pictures of dead birds and animals in NEBRASKAland, also that your husband has killed many farm animals but has never taken pictures so that he could brag about it.

I would like you to know that I have shot and killed several deer and antelope, untold numbers of squirrels, rabbits, quail, grouse, pheasants and even now and then a fox or coyote.

About three years ago I shot an Alaskan brown bear, not because I hate bears but simply because I wanted his skin, and I didn't know how to get it without killing him, but more important, I enjoy the chase. I enjoy the challenge. The killing of a bird or animals is the climax, the end of the hunt.

The hunt itself is the stalk, the matching of wits with Mother Nature. Let me assure you many times Mother Nature wins. I don't consider myself a killer — maybe some do, maybe you do. It is most difficult to explain why some of us enjoy hunting. But most of the hunters I know respect wildlife much more than non-hunters or indoor type people.

Oh yes, I have many pictures of myself and my friends taken on hunting trips, and I am happy to say that there are some with propped-up animals on them. There are also many more without animals. These pictures too, are just as valuable to me as the ones in which I was successful. These pictures are not for bragging, as you say. They are for remembering.

My license fees for the year 1973 are over $220. As you may know, this money is used by the various states for management of game. Certainly money well spent, money that is used for maintaining a healthy deer herd or antelope herd or maybe releasing a flock of wild turkeys. Money that is an absolute necessity so that those of you who do not approve of hunting may also have the enjoyment of an occasional fleeting glimpse of a deer or the chance to see a family of pheasants.

In closing, I would ask those of you who do not care for hunting, not to deny the sportsmen of our right to do so. We support our wildlife through hunting permits and donations. You need not help if you so wish, but remember that without the hunter, there would be fewer birds and animals. Wildlife that we can all enjoy in any way we like, both hunter and non-hunter alike.

Robert Alberts Hooper, Nebr. Kill The TameSir / Not all people can agree with Mrs. Kruse's line of reasoning (Nov. Speakup) concerning hunting.

Since man evolved as a hunter (as did the coyote and wolf and other predators) it is impossible to argue logically that hunting is not natural, especially when many scientists agree that this instinct to hunt is still present in our genetic makeup. Or perhaps Mrs. Kruse believes in the Creation theory as I do, but there again, man was created a meateater and hunter. ('We don't have a stomach in four sections like a cow!) Regardless of which theory you believe, man is by nature a hunter.

I will remind Mrs. Kruse that those hogs, cattle and chickens she mentioned were once wild, and then man domesticated them so as to have an easily available food supply so that all his time did not have to be spent afield in pursuit of meat for the family's survival.

Hunting and fishing are beneficial sports. As a den mother, I became aware that Boy Scouts of America has long recognized this fact, and they do help turn out some pretty good citizens. (Hunting and fishing are two sides of the same coin: the act and the end result are the same, only the "weapon" is different.)

Under the careful supervision of our Fish and Game departments, legal hunting is an asset to our wildlife, and also provides the necessary funds for study, care and enhancement of our wildlife resources.

Not being a golfer, batting a silly ball around with a stick seems a ridiculous pursuit for an adult, but to many, it is recreation and necessary. Just recently, I watched a bulldozer clearing land for a new golf course, uprooting the beautiful old trees that Dame Nature had spent 100 years fashioning. She spends only 2 to 10 years producing most mature big game animals, and a year or two on game birds!

Perhaps Mrs. Kruse should go back to Arizona Highways as she suggested, if she cannot recognize that there are two sides to every human endeavor and every argument.

Mrs. Lucille Harris Santa Ana, Cal. Small Farms GoingSir / First I want to say how much I enjoy NEBRASKAland and look forward to each issue. When I would go home on vacation I would dig out all the issues around the folks' home and take them back with me. So one day while there my dad had me drive him to Lincoln and he took out a two year subscription for each of his children (six total), so we have them as they come out.

My real purpose in writing this is to ask why you don't put more in about people. You cover hunting, wildlife, etc. but I feel we also have a vanishing breed, the small American farmer. When I go home each year there is another missing.

My great grandparents, grandparents and parents were all farmers near Walton. My parents were married over 55 years ago and moved on their farm near Walton and are still living in the same house. Many of the furnishings are the ones they first got. Round oak tables, oak chairs, beds, etc. Dad is now 80 and mother 75 years of age, but both are in good health, and I hope to be able to visit them for many years to come. So, before it is too late, please cover the vanishing American family farmer.

Philip Faulhaber, Lennox, Cal.Sir / Why was there no events listing in the December issue of NEBRASKAland? I had to sit home all month with nothing to do because I thought nothing was going on? What's the scoop?

Bored ReaderAs NEBRASKAland is gradually phasing out of the tourism business, due to several factors, we are no longer publishing an events listing or activities page. All such material should be directed to the Tourism Division, Department of Economic Development, 1342 M Street, Lincoln, Nebr. 68501. Anyway, people could well spend more time with their families, or staying home to read NEBRASKAland. Editor

NEBRASKAland Magazine invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to Speak Up.

Management studies brought us to the area, but any excuse was welcome. Fall weather appeared risky, but the terrain posed our biggest obstacles

Camp-out at Soldier Creek

SPOOKS SUDDENLY shoots away from us like an arrow from a 40 1 pound bow. Down the meadow he goes, into the shallow draw and up to the ridge line of Ponderosa pine. Seven mule deer rise from the grass, bound in a disordered scatter, then stand to stare. Only at the last moment —with the dog closing fast do they turn their heads disdainfully and dance over the crest.

Standing under a load of full packs, we are annoyed by the delay, yet glad at the first sight of deer.

"Spooks, get back here!" Carl at last shouts.

Hot after the deer, the dog disappears.

The sun is going down rapidly now. The evening wind has taken an edge, reminding us that this is after all the last week in October, however kind the afternoon sun has been. Standing still, we begin to shiver. To make camp before nightfall, we will have to hurry the last mile. Carl looks at his watch.

"Spooooks!" ring the canyons again.

We were in the Soldier Creek Special Use Unit, a 10,000-acre box of land just north of Highway 20 and 7 miles west of Fort Robinson. Formerly known as the Fort Robinson Wood Reserve, this area is now under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Forest Service. Slated to be come a primitive recreation area, open to hiking, horse travel and backpack ing, this near-wilderness will offer the outdoorsman an opportunity to hunt, fish and explore the habitat of deer, turkey, bobcat and beaver.

Larry Robinson, a wildlife biologist with the Forest Service and Carl Wolfe, a research biologist with the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, represent the joint endeaver of these agencies to prepare and develop guide lines for wildlife habitat and species management for this area. They would descend into the middle fork of Soldier Creek, establish a camp, and from there hike the unit to determine the effect of grazing on the creek bottoms.

Along with Carl was his 12-year-old son Jeff. As yet, all the survey work had been handled by Jeff's two-year-old black Lab.

At last Spooks reappeared, prancing proudly back. "Like a trooper strutting to rejoin the line after a successful foray," noted Carl. That light which excitement fires in a Labrador's eyes quickly faded, however; as he came up to us, his tail lowered with the reprimand not to chase deer.

Since the area we will explore lies in the west-central portion of the unit, we have entered the area not at the main entrance at Fort Robinson, but from the southwest corner, leaving our cars in a pasture near the highway. An old lumber trail takes us quickly to the main valley of the South Fork. In places, erosion has sunken the road so severely it looks like a dry irrigation ditch snak ing into the canyon. Along the embank ments grows a thick stand of young Ponderosa. A flock of pinon jays drops into a grove of nearby pines, chattering and mewing. We leave their quarrel behind, beginning the steep descent into the valley.

As we drop below the level of the sun, the wind hisses in the pines along the ridge above us. In this first shadow of night the air is already cold. At every turn, great windfalls of trees have been swept down or snapped mid-trunk, grim reminders of the wind which winter must chase up this slope.

It has become uncomfortably dark before we break out into the flat, surprisingly broad creek bottom. The pines give out abruptly to cottonwood, elm and boxelder. The stream itself has cut a narrow, deep trench in the valley. It meanders erratically, here and there impounded in long, deep pools, else where running noisily like a dog's impatience to be on, ever on.

At last we reach our campsite. Our rush to get set up produced a rattle of cook-kits, the hurried snapping of fire wood, a swish and billow of bright nylon as tents blossomed beneath the growing army of stars. Finally a fire danced before us, water was heating for the making of supper, and we were too busy to properly welcome in the night. Looking at the bright risen moon, I knew the night would be cold, but the clear sky promised good prospecting for tomorrow.

Morning coffee is never cooked soon enough. Jeff is down by the water examining the skim ice and having no success whatever in urging Spooks in for a morning dip. Sleepily, the three of us stare into a pan of water, waiting for it to boil.

Very slowly the sun climbed, as reluctant as we had been to face the morning frost. But with the activity of making breakfast, boots warmed and the smell and sight of eggs sputtering on a hot grill put a better prospect to the day's hike.

With Jeff detailed to rinsing the scoured dishes, and lunches stowed in a pack, we could sit down with a final cup of coffee and arrange a route down the valley. Carl pulled out the map.

If we traveled down the South Fork for several miles, we would pass the ruins of an old Boy Scout camp and the remnants of picnic stops used by of ficers from the fort. Then, leaving the valley and heading north, we would intersect "Trooper Trail," a newly constructed horse and foot path. This trail links the east entrance to an old access road which had dead-ended in the middle of the reserve. We would follow the trail for a mile or so, then drop back into the valley and head back to camp.

On the map all this proceeds quickly enough. I found myself wondering why we even bothered to pack a lunch. What I was not yet seeing, of course, were all the impediments: the contorted, deeply cut stream bed, the leaf ridden pools of quiet water and their stop-and-go traffic of water striders; and the heavy arms of cottonwoods which held a last gold fringe of leaves against the shadow of the canyon's cliffs. In short, nobody with a camera could walk those four miles in less than a day.

Spooks was after more exciting game. He nosed the brush for anything that might move. Having flushed a mouse, the fever was on him, and soon, with Jeff in train, they were lost to sight downstream. The sounds of rushing feet through collected leaves and breaking twigs drifted back to blend with the soft voice of the creek.

With so many spider webs against the morning sun I was finding it difficult to pay any attention at all to Larry and Carl, who were already conferring over a clump of wild plum.

"This whole area has taken some pretty extensive browsing," Larry said.

Carl was noting the location on his map. The condition of the banks and the converging cow tracks showed it to be an area of heavy use.

"Here's a good example of problems we want to overcome. The trouble with cow/calf grazing is that they never get out of the stream bottoms. These areas are abused while the higher grasses are never touched."

A possible solution, Carl went on to theorize, would be to modify grazing practices, either through use of different time periods or different modes of grazing. Steers, for example, tend to exploit the high ground and range farther afield.

After examining the sorry condition of some chokecherry and snowberry, we were again on our way, soon fining Spooks, who now thought he was a sheepdog, trying his best to round up a straggling of cattle.

I know of no pleasure that can quite compare to looking at a brilliant sky through closed eyelids while lying in a pile of dry leaves. Patterns of stars dance across my eyelids like visions of water striders. Even the wind seems to doze with the noon sun. Our sand wiches of jelly and peanut butter, and water from the stream make the best feast for such a day, and seem to drug the blood with peace. What must the trout see, looking up at the brilliant air, motionless in their bright pool until a wind gust wrinkles the surface and sends them shooting beneath the bank?

A box elder bug lands on my nose. So I sit up, letting go of such late October reveries, and find both Larry and Carl sound asleep. Jeff has buried Spooks completely in a pile of leaves; only his tail protrudes, wagging occasionally under Jeff's soft teasing.

NEBRASKAland FEBRUARY 1974

Hearing my camera shutter click, Carl asks without opening his eyes what I'm shooting.

"A couple of old porcupines I found sleeping in the sun."

"Really?" He sits up to find my lens pointing in his direction.

The valley is becoming narrower and the north outcroppings steeper. About a mile from the east boundary, we leave the creek and start north to intersect Trooper Trail. We cross a broad grassy 8 NEBRASKAland slope, largely undisturbed by grazing, before coming into broken stands of pines. Almost immediately we notice bird sounds and flights. Flickers, nuthatches, chickadees and jays abound, a contrast from the mostly silent creek bottom.

In less than half a mile we have crossed three life zones. The riparian stream course, with its hardwoods and understory of flowering shrubs, yielded abruptly to the terrace slope. This transition zone, mostly open grassland, exhibits a few mixed patches of shrub species. As we approach the bluffs an overstory of Ponderosa becomes dominant. Climbing briskly for 200 feet, we gain the upland zone. Here there is little protection from the wind and the pines show dramatically the effects of exposure; contorted and stunted.

From this upland zone we can sense the severe nature of the open plains, the great domes of mixed grassland rolling away unprotected from the harsh extremes of the continental climate. The wind dissolves the warmth of the sun, forcing us to put on our jackets.

Larry explains that the wind and rain sculptured formations along the ridge and outcrops of the Arikaree for mation, a hard clay substance which forms the dramatic bluffs and buttes of the Pine Ridge.

From our vantage point we can see

to the east the confluence of the south

and middle forks of Soldier Creek. Fort

Robinson, its water towers gleaming in

FEBRUARY 1974

Up the middle fork runs the old Hat Creek Military Road, which at one time connected Fort Robinson to Dead wood, S.D. The ruins of the Wood Reserve's caretaker's cabin lies up this valley near the north border of the unit. It is well worth a visit, according to Carl, so we plan that as our destination for tomorrow.

Providing the weather holds, that is. The wind has brought in a front of clouds which threaten to blight the rest of the afternoon. The gentle fall quality of the air this morning has rapidly deteriorated; the pines drone with a warn ing that the season is late, the coming days bleak. Our confidence in a clear tomorrow weakens.

Spooks, ranging far ahead of us, has flushed another herd of mule deer. This time, however, the dog is called in and the animals hold their stand, giving us good opportunity to glass them with Carl's binoculars. They had bedded on a timbered knoll below our ridge and separated from it by a sharp saddle. Obviously they feel secure in the gulf of open space which divides us. Slow ly, as if bored by the show, they walk off, two fine bucks among them.

After a mile of this excellent trail, of fering as it does far views across both valleys, we drop back south toward our campsite, rapidly recrossing the habitat zones until we are again in creek bottom. The temperature is bearable once more, the cloudy sky not so forbidding. Hunger takes us swiftly back to camp.

The preparation of supper is made an ordeal by a high wind. Whirlwinds of leaves speed past and the cottonwoods groan. This will be no evening to sit around the campfire.

By seven we are in our tents, listen ing to the fury of the wind against tree and tent, cold again despite protection, vaguely uneasy at the possibility of snow. Morning is a long way off.

What I thought at first was snow, up on sticking my head out of the tent, proved only a heavy blanket of frost. During the night the wind had subsided and the sky had briefly cleared, allow ing a bright moon to stare through the nylon cloth. But there was no sun at dawn, the sky filled again with gray, ominous clouds.

The weather made us a little more proficient at organizing breakfast and NEBRASKAland preparing our lunch, eager to begin the hike and stoke some heat in our bones. Both Carl and Larry mentioned hearing a bobcat scream during the night. I must not have been awake as much as I thought.

As we head west up the valley, we pass a succession of wide pools in the stream. Large rainbows are abundant, and we plan to attend to this matter on our return.

A steady, cold wind pummels us as we break out of the creek bottom, heading northwest. Spooks has become more businesslike, his attention not so far-flung and indiscriminate. Perhaps the drab, inhospitable weather has made him, like us, more aware of the goal of the day's hike; unlike yesterday, there is not much pleasure in loitering along.

We pick up another wagon trail which takes us up the long, steep slope to high ground. It's difficult to imagine anything shy of a four-wheel drive negotiating this sheer, broken, twisted road. A half-hour of steady climb puts some color in our cheeks.

Finally we achieve high ground, the pines thinning out, the dry grassland leaning under the wind. This land is pleasingly eroded, an arrangement of swales, gentle gullies, meandering crests, all grass covered. Here is a taste of the old magnificence of the Great Plains. We must all be thinking of the suitability of a high camp-to watch the sun go down and come up from such a place-for Larry mentions that campsites on high ground are being planned in the development of the area.

Leaving the old road, we cross a fenceline and strike out across the open land, heading toward a windmill which stands on the highest point. Everywhere are mounds of earth, the diggings of pocket gophers. We discover coyote scat on a cattle trail, pass a large excavation on a hillside —probably a badger hole. Spooks is a little too interested. Close inspection reveals a rim of frost around the hole, probably breath condensation. Jeff takes Spooks by the collar and we continue on.

At the windmill we call a rest. The machine had been shut off and the stock tank was half empty. Scores of waterboatmen oared through the green water. In trying to reach a drink, Spooks perched himself precariously on the tank edge; naturally this proved too much for Jeff to resist. But the dog real ized what was coming in time and bounded backward before Jeff could push him in.

Carl released the windmill's brake and the mahine groaned at being awakened, caught the brisk wind, and squealed to life. The first rusted gushes we let go by before taking mouthfuls of the jaw-numbing water.

Jeff's incessant urging of the dog to get into the \vater —bodily lifting its forelegs over the rim of the tank —continued until Carl called a halt.

That boy will do anything to get you to take pictures of his dog."

"Well," I said, "maybe we can get a shot of them swimming yet."

Just then it began to spit snow.

Larry tugged at the hood of his blast jacket. "Let's get down to the valley."

"How far yet?" I asked Carl.

"A quick mile —let's go." He pulled hard on the windmill brake wire, dangled for a moment like a bell-ringer in his contest with the wind, and the blades began to spin slower, the brake screeching the machine's momentum to a halt.

We picked up another old road and were soon down among the pines.

The ruins of the caretaker's cabin are located beside the stream below a tremendous cut in a bluff. All that remains is the fireplace, a part of the north wall and a woodburning cookstove dated 1923. The log cabin had been quite large.

Having just sat down to lunch, Spooks came whimpering back from some cottonwoods upstream; from his mouth dangled several quills. Wearily, Carl put down his sandwich. "That," he said, "had to be inevitable."

Finding the porcupine, finishing our lunch, and exploring the area consumed the better part of two hours. Under the thick canopy of trees, we had not noticed how completely the clouds were breaking up. As we packed to head back out of the valley, the sun came out. Since the wind had also died, the temperature soared. Soon we were sweating. By the time we reached the windmill, all agreed that snow in the air makes for better hiking.

The sudden return of warm weather brought out a rash of grasshoppers in the long grass. We all had the same idea at once. Scrambling to capture a film-can full, our minds were on the pools of trout that awaited us near camp.

Even Spooks made a try at this game, snapping his jaws at the flying bugs.

We decided to break camp before trying out luck with the trout. Since the sun was getting low, we would have no more than an hour's fishing if we were to reach the cars by sundown.

Larry and Carl readied their lines and soon the water was broken by snapping trout. Unfortunately, we soon discovered the big ones weren't doing the snapping. Uninterested, they lay in the water like spent torpedoes while swarms of six-inch offspring raced after the bait.

Carl decided it was too close to fall spawn for the big trout to be interested in food. It looked like a lost cause, frustrating because the enterprise had appeared so easy.

Spooks was intently interested in this procedure, lying on an outcrop and watching the fish below. Jeff took great care in stalking him this time. When he got close enough, I called out to push him in and I'd get a picture.

The dog instantly rose to a crouch as Jeff's hands touched his back. For a second the two were locked in balance. Then, predictably, Jeff leaned too hard against the dog and Spooks laid down, causing Jeff's hands to slide up and over the dog's head. One precious second of horror crossed the boy's face as he grabbed for air. Beneath his feet the bank crumbled and with a shout he slid into thigh-deep water.

"Serves you right," said Carl, making one last cast.

The face of a black Labrador is most expressive. Sometimes —many people will swear— it can even manage a grin. The rest of us managed one without trying.

Paddlefish... what about tomorrow?

THROUGHOUT HISTORY, in our dealings with wild animals we have taken while the supply was plentiful, and in turn bemoaned the inevitable scarcity that followed. Nebraska Game and Parks Commission biologists hope to reverse that regretable tradition in the case of the Missouri River paddlefish.

Cooperative studies with the South Dakota Department of Game, Fish and Parks over the last two years should insure that the abundant supply of paddlefish we now enjoy will still be available in future years. On-the spot creel censuses, tagging operations and a snagging mortality study were designed to determine the degree of the current harvest, the status of the paddlefish population in the Missouri River and ultimately, the fishing pressure that the species can withstand.

Paddlefish feed on microscopic floating or swimming animal and plant life called plankton. Because this is their only fare, traditional hook-and-line rigs are useless in catching them. The only way for fishermen to catch a paddlefish is by snagging-the jerking of large treble hooks through the water until they imbed somewhere in the fish's anatomy. From that point on, fighting the snagged fish is much the same as other types of angling.

While this may not be fishing in the sense that Izaak Walton had in mind, and may not require the skill and patience of more conventional methods, it is the only means of harvesting paddlefish. Without this form of regulated harvest, paddlefish would be an unutilized resource at a time of burgeoning recreational demands.

Information resulting from the paddlefish study will help determine management policy, aimed at maintain ing the fishery at a constant, harvestable level.

Creel censuses at the Gavins Point tailwaters have yielded information, not only valuable to the fisheries manager, but to the snagger as well. For example, the census showed that approximately 4,500 paddlefish were taken in the tailwaters during the 1972-73 season. Roughly 1,500 of these were caught during December, the most productive month. January and February were the next best months producing 988 and 832 fish respectively. The study showed that the first two months and the last two months of the legal snagging season are by 12 far the least productive times to fish. Though snaggers are present in good numbers, the paddlefish harvest averages less than 50 for either the first or the last month.

Not only did December produce the most paddlefish, but it also produced the largest fish. Paddlefish taken by snaggers from boats in the tailwaters averaged 26 pounds, while those fishing from shore caught fish aver aging just over 18 pounds.

Creel census information not only aids biologists in estimating the annual harvest, but also yields other more valuable data that when compiled and analyzed, gives them a good indication of the population's status.

Whenever possible, biologists collect the lower jawbone from the catches of cooperating anglers. By slicing a thin section from the jawbone and examining it under a microscope, biologists can read the growth rings, much the same as foresters do with trees, and calculate their ages and rates of growth.

Information derived from jawbone cross-sections have shown that paddlefish are relatively fast growers. Two-year-old fish averaged about 5.2 pounds each, 3 year-olds averaged 9.8 pounds, 4-year-olds weighed 12.4 pounds and at five years, paddlefish averaged 16 pounds. The 40 to 50-pound paddlefish occasionally caught are likely to be from 13 to 15 years old.

In addition to information gained from creel cen suses, much valuable data is being compiled from paddle fish previously marked with bands through the lower jaw and then released. When these fish are later caught and the bands returned, biologists are better able to calculate fish movements, harvest, and in some cases, growth rates.

Tag returns have revealed some long-range paddle fish movements. One large fish snagged below Gavins Point dam last year had been tagged 200 miles upstream in the Big Bend tailwaters near Chamberlain, South Dakota in 1969. Another fish, tagged below Yankton, was caught near Sibley, Missouri a year later. All indications are, though, that these long-range movements are exceptions rather than the rule for paddlefish. Most fish are recovered within a few miles of their tagging site.

From information gathered by creel census and band returns, biologists have gained a fair idea of the paddle NEBRASKAland fish's status in the Missouri River below Gavins Point dam. In general, it could be described as very good. The fish show rapid growth and good numbers seem to be present. The balance between the numbers of young and old indicates that production is good.

Unfortunately, the outlook for paddlefish is not so optimistic in other areas of the Missouri River. Downstream, below Ponca, the paddlefish's spawning areas have been seriously altered, perhaps irretrievably lost because of channelization. No reproduction has occurred upstream from Fort Randall dam since the filling of the last reservoir.

Paddlefish taken in the Gavins Point tailwaters may seem to be coming from an endless supply, but fisheries biologists caution that most are spawned in a relatively short stretch of river between Lewis and Clark Lake and Fort Randall Dam in South Dakota. The area from Gavins Point Dam to Ponca may provide some limited spawning habitat. Together, these two stretches of river provide less than 100 miles of water suitable for paddlefish reproduction. Any drastic changes in this last remnant of natural river will likely spell the immediate end for paddlefish snagging as we know it today.

Another study conducted last winter by the South Dakota and Nebraska biologists was initiated at the encouragement of both states' law enforcement officers. According to officers' observations, the practice of "high grading", which is the returning of injured fish to the water when larger ones were caught, had reached epidemic proportions.

Most snaggers guilty of this offense probably do not intend to return injured fish to the water when they first arrive. If they have driven hundreds of miles, though, and happen to hit one of the good days, they may find the temptation to toss back small ones in hopes of hooking larger ones, irrepressible. Unlike most fish, paddlefish do not have swim bladders to keep them afloat, so once kicked overboard they simply sink to the bottom and be come food for scavengers.

During a recent test, twenty-two paddlefish of various sizes were snagged in the tailwaters of Gavins Point using standard tackle. These injured fish were then transferred FEBRUARY 1974 to a pond at the Gavins Point Fish Hatchery for two and one-half months. When the pond was drained, it was found that the wounds often fish had healed cleanly and they were found to be in normal health. Nine fish had badly infected wounds, covered with heavy fungal growths. The remains of three fish were found on the bottom of the pond, presumably victims of the snagging injuries.

These results indicate that the number of fish removed from the tail water population as a result of snagging, far exceeded the actual 4,500 that went home with fishermen last year. Some snaggers have been observed returning as many as 40 paddlefish per day when fishing was good. Many of these never lived long enough to spawn or to be caught by other fishermen. They may just as well have been dumped on the shoreline as be thrown back into the water.

Based on information derived from these studies, the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission initiated new regulations the first of this year designed to insure the continued viability of the Missouri River paddlefish populations.

The most significant regulation change requires that "any paddlefish caught must be counted in the bag." Hopefully this requirement will stop the practice of high grading and insure the efficient use of a limited resource.

A second regulation reduces the possession limit from four to two fish. The daily bag will remain at two paddlefish. This will make Nebraska's limits the same as South Dakota, whose anglers fish the same waters.

While these regulations may seem restrictive, they are designed with the snaggers' long-range benefit in mind. Through careful management, paddlefish populations can be maintained at a level where sport harvesting will always be possible. Snaggers have everything to gain by observing them, and, everything to lose by not. The choice is entirely theirs. A few violators in the limited areas involved can have a tremendous impact on future populations and regulations. Legitimate sportsmen, there for, should be especially watchful for persons ignoring the new regulations, and report violations immediately to authorities.

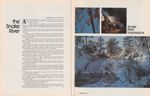

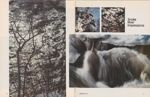

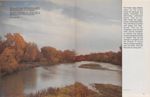

the Snake River

A RIVER CALLED SNAKE. It is a powerful, rushing water that cuts at the very earth, etching out a valley as wild and beautiful as the waters that are its creator.

Sheer canyon walls are witness to the years of the Snake. The Valley of the Snake between Merritt Reservoir and the river's joining with the Niobrara is an open wound, revealing the centuries-old struggle between water and soil.

More a canyon than a valley, layers of bleached gravel and stripes of varying densities on the vertical walls chronicle the river's time-machine workings.

Cutting back into unwritten history, the River is a scholarly archaeologist, revealing the remains of a prehistoric bird or animal. Calcified with an ivory beauty, the bones shine in the sun after their long entombment by layer upon layer of soil and rock.

Yesterday's river witnessed the life-death struggle daily, as the large and the small, the strong and the weak, came to their final rest by the river bank. Wood, turned to stone, and opalized ivory litter the gravel under the swift flowing water.

Here a glint of sunlight shows a finely chipped flint point, proclaiming the artistry of early man. A delicate object with pepper-like black markings on a field of orange, its esthetic appearance belies the utility and deadliness of purpose. What stories of human endeavors has it witnessed?

The River's rushing course slows here and there to accommodate the widening influence of deep pools. The clear water reveals even more of the past. Still intact, the skull of a long-dead bison stares up through the passing water with empty sockets, the only visible clue to the great herds of such animals that once watered at the banks of the Snake.

The River was then as it is today —a Valley of Life running through a vast stretch of semi-arid sandhills. Today's animals drink its waters, treading in the footprints of now extinct relatives.

Man, too, has changed from the days when the Indian found a safe haven along the Snake, but the River remains a Vein of Life, and wild grape and rose tangle the stream's banks.

As timeless as the rocks and bones, the first warming rays of morning sunlight outline frost-ringed leaves. The silver-thin needles of pine begin to redden as the sun hurries its climb. A well-orchestrated dance is unfolding. The stage is set before a red curtain of light bouncing from white rock and frost-laden grass.

Shadows move to nothingness in step, and the undulations of water over rock lend a musical cadence.

Here and there is the morning cry of wildlife and birds that populate the River's canyon country. A startled magpie chatters off into silence, leaving only a lingering impression that something is beginning to move with the morning's first light.

Layers of mist entwine in the limbs of an overhanging pine. Its arms, gloved in white, wave slowly with the freshening breeze.

It's been thus since the dawn of time.

The Snake is a River of Life, and to hear the song it sings is to reach out and touch Nature. Hold close those impressions, for the untrampled realm of Nature is the everlasting salvation of lesser spirits.

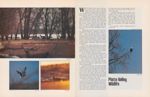

Your Wildlife Lands The Platte Valley

A fine, sand bottom makes the Platte River an always changing braid of sand-bars and water. Today, sun glints on sand that may be gone tomorrow. But sometimes an island stays long enough for wind-blown willow seeds to sprout; and their roots will stabilize the shifting sand. Grasses and cottonwoods follow. The sandbar becomes island. The river continues to wind between, always a threat to the serenity of wooded bars. Meanwhile, wildlife rests; a few ducks here, some cranes there, an eagle, a beaver, a deer... Photograph by Greg Beaumont

Your Wildlife Lands Growth and Change in the Platte Valley

A mile wide, an inch deep; the Platte has never been first choice for navigation. It has offered a broad, flat valley that's rich in plant and animal life. A path to the never-never land of the West, the river is now a westward trail studded with many little lakes and myriad wildlife species. From fur trappers in bull boats to vacationers on the bustling interstate, its cool waters have supported generations of seekers after the many wonders nature offers them.

THE PLATTE would be quite a river if you could stand it on edge." - Washington Irving once remarked.

A see-through ripple, stretching a mile across, an inch deep; that's the Platte of the past as well as the present. Sun glints on moving water as shouting, perspiring men finally admit it —their journey has come to a grinding halt. "If we'd only started a week earlier," they mutter darkly, surveying the load of hides in the grounded bullboats. With only 200 or 300 miles remaining to traverse before reaching the Missouri, the trappers curse their bullboats, the shallowest craft in existence, a contrivance of buffalo hides stretched over willow frames.

Stomping sand and less-than-ankle-deep water, they expand their bad humor to include the Platte River and the entire West and the hulking buffalo that look on. "Why, this God forsaken river won't even float an Indian canoe at full flood," they growl coarsely.

Throughout its history, the Platte River has wandered and meandered as it pleased across the Nebraska landscape, never caring that man might want to ford it or float it. Its fine-sand bottom has offered little resistance to constant and erratic changes in its course. It is even today ever changing.

Yet, while trappers in bullboats cursed it, some settlers who came later, hungry for land, home and future, compared its environs to the Nile Valley. "A fertile oasis," they enthused. Others condemned it. "A desert," they said. But rich prairie sod presented an existing model of natural balance and the infinite variety of plant life that could grow there.There were few wooded areas, though, partially because prairie fires came frequently to gobble up all green things, and stopped only at the cool waters of the river —only inches deep, but wide enough to provide a fire break. The prairie grasses and wildflowers, how ever, survived to sprout and bloom again from the roots. It was as though the land had an urge to live, and the prairie vegetation was its manifestation.

Cutting west as it did, the Platte Valley was a flat, relatively easy corridor to the gold fields and the never-never land of farms and orchards in California and the Pacific Northwest. The river it self provided water and the timber of its always changing islands.

Early day travelers added their curses to those of the trappers as they crossed buffalo trails. Running perpendicularly to the river's course, and to the wagon trail going west, the eroded ruts resulted in broken axles and mired wagons. Herds numbered not in the hundreds nor even in the thousands, but tens of thousands, and a wagon train might travel through a congregation of the beasts for an entire day before getting out the other side. It was a spectacular sight, but a grueling experience not much appreciated by road-weary immigrants trying to find home.

Wolves, too, took the travelers' imagination and attention. Their early morning howling and their habit of downing livestock made them none too popular with those who crossed their domain.

Prairie dogs offered comic relief to saddle weary migrants. Their villages stretched for miles across prairie grasslands. The 49ers were some times amazed at the strange bedfellows that the prairie made. They discovered rattlesnakes and owls were not only comfortable, but also permanent residents in prairie dog burrows and communities.

Today the wildlife of the river has changed, but is is no less spectacular than in the past. The buffalo are gone, but the spring migrations of Sandhill cranes remain, demonstrating the primitive urges of wildlife to follow ancient patterns. The migration has probably existed since the glacial age when cold drove them south for winter.

Bald and golden eagles roost quietly high in the cottonwoods, surveying the territory they claim as home. Thousands of migrating ducks and geese stop over in the Platte Valley to rest. Songbirds, deer and many small mammals use the valley now as in the past.

Today, a modern interstate highway replaces wagon ruts, and that highway is responsible for wildlife and recreation areas along its expanse. Lands purchased to provide fill material for the highway have been turned over to the Game and Parks Commission as public-use areas.

And today, the Game Commission controls these small wildlife areas, dedicated to preserving, as much as possible, the wildlife that now use the river and its surrounding land. There are 36 parcels of land between Grand Island and Big Springs. In cluded in these areas are 3,526 land and 661 water acres for a total of 4,187 acres.

Along these tracts are also 1 7.5 miles of Platte riverfront. Here a man can build a temporary blind, either facing the river or looking onto one of some 49 lakes set into the Platte Valley wildlife areas, and from that blind he can count on some of the finest waterfowl hunting in Nebraska.

All sorts of outdoor enthusiasts are drawn to the Platte areas. There are no sophisticated developments, no playground equipment, no modern restrooms, no camping pads, and no electrical hookups for camper-trailers. There are birds and beavers, deer and ducks, trees and prairie grasses and wildflowers. There are sandy beaches and grassy shorelines, there are clear, sand-bottomed lakes and a flowing, ever-changing river.

A guide to the Platte Valley wildlife areas follows. You will find a description of recreation possibilities, management philosophies, and the wildlife and plants that you will encounter as you explore the valley of the Platte.

Platte Valley Recreation

SHIVERING leaves drift into a quiet pool and float on cold waters. Heavy skies rest in the tops of cottonwoods, turned shimmering gold when touched by dawn light. A man sits alone, lulled into a sense of peace by the breaking dawn when his senses explode with the faraway sound of quacking mallards....

All along the Platte, on wildlife areas dedicated to "primitive" outdoor experiences, this scene and many others are repeated throughout the year. Each season brings a wide variety of solitary and family outdoor experiences to be savored.

Unlike the state park and recreation areas, wildlife lands offer few developed facilities. They do, on the other hand, provide visitors with an assortment of contacts with a natural world that cannot exist alongside extensive development and heavy use. The charm and beauty, and sometimes the harsh reality, of nature on its own are the basis for keeping these areas as nearly as possible in their natural state.

The quiet flow of a broad Platte River sweep ing across Nebraska touches these wildlife lands, scattered in rustic parcels along Interstate 80. River fishing is good, with catfish as the major objective. Carp and an occasional bass are also part of the river fishing fare.

The many sandpit lakes that garnish Platte Valley areas also offer the angler many hours of sunshine and glittering water, and fishes to satisfy his appetite for sport as well as nourishment. Smallmouth, largemouth and rock bass, bluegill and catfish offer a variety of sporting opportunities.

Camping on the areas is primitive; a bedroll beneath whispering willows and cottonwoods, a tent on a grassy lakeshore, a campfire under the canopy of stars and glowing moon. For those prepared to meet the elements on their own terms, such camping is a year-round means of unwinding and testing their understanding of nature.

The silent thrust of paddles brings canoeists gliding down the Platte or around lakes that stud the lands. There are dozens of willow-covered islands for camping or just landing for a break or a picnic lunch. Majestic trees and thick shrubby growth line the banks of the lakes and river on these special wildlife lands. Man becomes just a part of the variety of plant and animal species that live in the midst of these natural plots. Here he can be himself, alone with his thoughts and aspirations and imaginings.

Or a family might choose to strap on back packs and hike throughout the wooded flatlands bordering the waters. There are game trails to be located and insects to observe. Silence and alert ness might be rewarded with a glimpse of a white tailed deer returning to its daytime resting place. There are all sorts of signs left by the animals that have been through the sand and grass of undisturbed lands.

Songbirds by the dozens build nests and raise young in the trees, shrubs and grassy depressions of the Platte Valley. Birdwatchers can observe the courtship rituals of Sandhill cranes. In spring and fall, thousands of ducks and geese stop briefly on the river, which is along a major flyway. Eagles, both bald and golden, overwinter along the river, and heronries provide a glimpse of another large bird species.

Some of the finest waterfowl hunting in Nebraska belongs to the Platte River Valley. Upland hunters will find squirrels and rabbits, along with quail and pheasants utilizing the heavy, wooded cover of these wildlife areas. White-tailed deer, too, and an occasional mulie, wander through the wooded river areas.

For the nature buff, the entire system offers a contrasting progression of plant and animal communities throughout the length of the 1-80 complex. Starting at the eastern end, near Grand Island, observers will find mature riparian forests. One can discover the cycle of life nature provides through the death of old vegetation and the renewal of species through natural genetic selection and crossing. As one moves up the Platte, a change can be observed from dense woody cover to the more primitive shrub and willow growths which gradually give way to even more sparse vegetatation. The developing ecology of a river forest is there to be seen.

Animal life abounds, to be noted and studied. From insects to birds to reptiles to mammals, and the plants that support them, the interrelationships among the various species of plant and animal life can be traced throughout the wildlife areas along the Platte. Tiny communities demonstrate in a micro-view, the beauty of interdependence, with brilliant red and orange bittersweet and twining grape vines growing together with white-berried dogwood, all providing their fruits for birds and mammals.

Photographers will find brilliant color and fantastic vistas of rippling water and stately trees intermixed with tiny flowers. There are mirror pools and tangles of vines and shrubs growing over the fallen and decaying trunks of dead trees.

Throughout the Platte Valley complex of wild life areas, visitors can find a view of life in its most simple, but most complex forms. It is primitive life, the wonder of ecological change and growth, the dynamic world of nature. It is there for the asking and the looking. There are opportunities to participate in these natural communities with shotgun and rifle, with fishing rod and binoculars, with camera and backpacks and tents, or only with eyes to see and ears to hear, and the senses to taste, touch and smell.

Platte Valley Management

AND WHEN the hills are flat; when the corn stands in present 'waste' areas and people crowd by the thousands into overdeveloped park areas to stand on tiny patches of grass, where are my children going to see the hawks and the gulls and the free-roaming deer, and the muted colors of fall trees?"

Perhaps the wildlife areas provide a corner for eagles, a small island in the inundation of burgeoning civilization. These small plots along I-80, on the great, historic Platte River Road, are managed to protect their primitive integrity as much as possible.

Here nature is retained as landscape architect, but with a little help from concerned men. Here a tree dies and is left to rot, and to provide nourish ment for coming generations of trees and flowers and grasses. Here the harsh/smooth texture of wildlife —animals and plants —is left to develop its own shades and hues.

Trees and shrubs, mammals and birds are free to find their own "friends", to establish their own communities, to discover their own comforts. And the rich tapestry of the areas lies in the infinite variety of mixtures and dependencies with which the wilderness protects her own.

Man comes face to face with natural realities in the Platte Valley. A serene riparian woods or a river sandbar is in drastic contrast with the busy, noisy thoroughfare only several yards distant. Area managers are not concerned with providing the conveniences of life that too often overcrowd and spoil beautiful landscapes. Rather, they try to make available for enjoyment the basic resources of nature. For those who need facilities for modern camping, for power boating, for picnicking, other public recreation areas can be found not far from these wildlife areas.

An unspoiled wildlife area must remain relatively untouched by the machines of man. Vege tation must remain uncut to provide for wildlife needs. Trees and shrubs are allowed to "go their way". This is not to say that plants may not be added to areas, or that mowers are never used.

Vehicle access is usually limited to a perimeter parking lot, and the wonders of most areas will be discovered only on foot. In most cases, primitive campers must carry in their water and carry out their garbage. Bassway Strip will be the site of a formal primitive camping system, where sites will be designated along a system of foot trails. On certain other areas, hikers will be free to select sites.

Wildlife management efforts are directed chiefly at allowing vegetation to remain in its natural state. Squirrel trees will be preserved, shrubs will be encouraged as habitat for rabbits and deer. In addition, however, the Game and Parks Commission uses selective planting to add value to the areas.

The planting program, which involves thousands of trees, shrubs and wildflowers, is not an attempt to replace native vegetation. It only supplements existing species. Clumps of cottonwood, boxelder and ash are enhanced, for example, by the addition of hardwoods such as walnut, oak and pecan.

A few of the Platte Valley wildlife areas appear on the north side of I-80, with the highway between them and the river. In most cases, these areas are just small lakes surrounded by narrow bands of land with little or no natural vegetation. Here Game Commission plantings are aimed at providing "fisherman shade", protection from glaring sun along the shoreline, and herbaceous cover to stop erosion of the sandy soil.

Flowing through a broad, flat valley, the Platte River has been known to change its bed with little provocation. In flood stage, the river can wreak havoc on the tiny sandpit lakes adjacent. Over the years, Game Commission personnel have sand bagged and diked to protect these lakes from flooding, but some have been irretrievably lost and others damaged. New and repaired dikes are expected to help preserve those remaining.

And in those remaining, stocking efforts have provided a fine fishery. Dozens of lakes have been stocked with largemouth, smallmouth and rock bass, catfish and bluegill, in various combinations, and a few have received walleye and Kentucky spotted bass. Some have been renovated and restocked—replacing rough fish with game species. Each time a lake floods, rough fish are washed in and game fish disappear from its waters. Often, repair of even minor flood damage includes overhauling the lake's fish population balance as well.

Vegetation, wildlife and fish management are only the initial problems on the Platte Valley wild life areas, or any areas designed for public use. People-use creates the most difficult problems to be solved. Only people take truckloads of house hold trash to the wildlife areas and dump it; only people drag crumpled car bodies to graves on quiet sands; only people become vandals and maliciously destroy facilities provided for their use. It is people who tear out guard rails and drive through grassy lowlands. Through carelessness, humans take their fires into silent wilderness and destroy trees that have decades of life behind them. Be sure you are not the destroyer who defaces these small wildlife areas and deprives your children.

"Where are my children going to see the hawks and the gulls and the free-roaming deer, and the muted colors of fall trees?" Wildlife man agers of the Game and Parks Commission hope that some of those things will survive this generation, and those to come on these Platte Valley areas —and others like them —managed with the same philosophy and care throughout the state. A philosophy of man in harmony with nature.

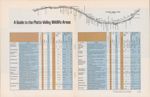

A Guide to the Platte Valley Wildlife Areas

Area Name Location Big Springs Big Springs Interchange, 0.5 north, 0.75 east. N&S 8 Ogallala Strip Ogallala Interchange, 1.5 miles south, 4 west, 0.5 north over overpass, 1 east-foot access across irrigation drainage ditch. N 293 R East Sutherland Hershey Interchange, 0.2 mile south, 3 miles west, north 0.5 mile, south 0.1 mile N 27 8 F L WestHershey 1-80 milepost 164, Hershey Interchange, 0.5 west N 6 16 G Hershey Hershey Interchange, 0.2 miie south, 0.2 mile east S 53 70 G L East Hershey North Platte Interchange, 0.4 miles south, 7.8 miles west, 1.6 miles north across 1-80 overpass, right turn, 0.2 mile south, 0.2 mile east N 20 20 G L Birdwood Lake North Platte Interchange, 0.4 mile south, 3.6 miles west, 0.9 mile north across 1-80 overpass left turn 0.1 mile south N 20 13 G L Fremont Slough North Platte Interchange, 1.5 miles south, 4.8 miles east, 0.3 mile north, 0.1 mile east across canal, 0.2 mile north under 1-80 overpass, 0.3 mile east, 0.1 mile north N 30 11 G L West Maxwell Maxwell Interchange, 0.7 mile north, 0.8 mile west, 0.3 mile south N 7 6 G L West Brady Brady Interchange, 0.8 mile north, 0.4 mile west. 0.1 mile north, 1.6 west across 1-80 overpass S 5 10 G L Brady Brady Interchange, 0.3 mile south S 25 16 G L West Gothenburg Brady Interchange, 1.5 miles to Brady, 3.5 east, on Highway 30, 0.2 south across R.R. tracks N&S 15 36 0.3 G L East Gothenburg Gothenburg Interchange, 0.4 mile south, 0.4 east, 0.1 mile northeast, 3.4 east, 0.1 mile north S 13 24 F a L Willow Island Cozad Interchange, 1 mile north to Cozad, 5.2 miles west on Highway 30 to Willow Island, 0.8 mile south across R.R. tracks left turn, 0.1 mile north s 30 45 F L East Willow Island Cozad Interchange, 1 mile north, 1.7 west on Hwy 30, 0.8 south over 1-80, 0.5 west s 16 21 0.5 F L&R West Cozad Cozad Interchange, 1 mile north to Cozad, 1.7 miles west on Highway 30, 0.8 mile south across R.R. tracks and over 1-80 overpass, 0.1 mile east, 0.1 mile north, 0.1 mile east s 18 29 G L Hunting Other Activities Fishing Area Name Location Cozad Cozad Interchange, southeast quadrant S 1 16 182 0.5 G L&R EastCozad Cozad Interchange, 0.1 mile south, 1.5 miles east s 4.5 Small Wildlife Production Area Darr Strip Cozad Interchange, 0.3 mile south, 2.5 east s 767 2.5 Darr Darr Interchange, 0.5 mile north, 0.3 mile west N 1 10 21 G L East Darr Darr Interchange, 0.1 mile south, 0.5 mile east S 14 0.1 G Lexington NE quadrant Lexington Interchange, 0.2 mile north, right turn at Dept. of Roads office, 0.2 mile south N 1 13 26 G L Dogwood Overton Interchange, 1.5 miles north, 5 miles west, 1 mile south over 1-80 overpass, turn left, 0.1 mile north S 1 5 264 1.5 G R&L Overton Overton Interchange, northwest quadrant N 1 5 14 West Elm Creek 1-80 milepost 252 N 1 8 24 Sandy Channel Elm Creek Interchange, 1.3 miles south S 11 47 133 F&G L Blue Hole (2 locations) Elm Creek Interchange, 0.3 mile south, left turn, 0.1 mile north, right turn. SW quadrant, Elm Creek Interchange S 2 37 538 2 F&G R&L Blue Hole East 2.5 miles east Platte River Bridge S R 86 0.25 Coot Shallows Odessa Interchange, 0.7 mile north, 1.7 mile west, 0.1 mile south N 1 13 30 G L East Odessa SE quadrant, Odessa Interchange, 4.5 miles east S 1 10 121 0.5 G R&L Kea West Kearney Interchange, 1.1 miles north to 11th Street, 1.3 miles west, 0.9 mile south to overpass approach, left turn, 0.1 mile south N 1 7 4 G L Kea Lake SW quadrant, Kearney Interchange, 0.1 mile south, 0.1 mile west S 1 15 12 G L Bufflehead Kearney Interchange, 1.1 miles north to 11th street, 3 miles past, 1 mile south, 0.6 mile east N 1 13 27 G L Bassway Strip Minden Interchange, 0.4 mile south, left turn, 0.4 mile across Platte River bridge. S 8 90 635 7.0 G R&L Wood River West Wood River Interchange, 0.4 mile south, 1 mile west, 0.1 mile north across overpass, 0.2 west N 1 15 13 G L Loch Linda Alda Interchange, 1 mile north, 2 miles east, 0.5 mile south, 1.5 miles east S 1 20 50 0.5 F R&L G- Managed, good game-fish population F=Floods periodically, mostly rough fish L=Lake R-River

Platte Valley Wildlife

WIND RUSTLES willow leaves; wind rip ples tall bluestem; wind touches the tender petals of rose mallow, ruffles the feathers of a golden eagle, skims the fur of a cottontail, and carries scent to a wary deer. It's dawn and life awakens to a Platte Valley breeze.

A fleeting ray of morning sun glints on dew drops, reflecting the outline of a spider web. That same sunlight touches another, far more intricate web as it warms the valley. The web of life along the river is a prism, a delicate piece of glass or drop of dew. Turned to the sun, the white light which is a whole community breaks down into the many colors of wildlife, vegetation, land contours, soil types and water that together make up the valley.

Looking deep into the crystal of land and life, the naturalist becomes a soothsayer. "Here, my children, here is the past, the present and the future" Here in the decaying trunk of a cotton wood tree, here are insects and worms feeding on the death that gives life. But, hush. There's a wood pecker, a flicker pounding out a veritable rhythm of living. He's looking for food —insects —and he's creating a home. A nest in the decaying carcass of a once-majestic cottonwood. There's life in the old giant yet.

And in the topmost branches is an eagle, roosting on a still-sturdy branch where his view of his kingdom is unobstructed by bothersome leaves. Occasionally he reaches back to preen shining feathers, feathers that reflect the sun and refract its rays into rainbow colors, as a prism.

Lazily, he lifts off and glides toward the river, settles on the sand and gives the "eagle eye" to the glistening currents. Yes, there's dinner. He thrusts his beak into the clear water, drawing out ...only a minnow? This requires more study.

But his quarry is in a hurry. There are tiny, life-giving organisms to be consumed. A second thrust and for a moment sunlight flashes on wet scales, separating light....

Sun glints on fine sand. The river has created a sandbar. It's just a pile of sand with water drifting on all sides, but life longs for life, and wind carries winged seeds to the dead sand. If the bar can last but a season, the willows can begin to grow. If time only allows, the sprouts can send down roots, roots to bind the island, roots to make a future for lifeless sand. Willows and cottonwoods are themselves pioneers, facing a harsh and uncertain future so that others may follow.

If they are successful ...but they won't all succeed. The weaker ones will die, thinning the stand and making room for followers that will en rich the island with their own quirks. Ground ivies and shrubs such as dogwood will come, along with sedges and maybe bluestem to provide berries and seeds. Songbirds come to feed on the island; deer come to browse on the tender shoots of young trees and to escape predators that shy away from water; beaver come to chew the succulent young trees.

Growing roots bind sand ever tighter, slow ing high waters and holding even more sand, providing ever more security. Yet, one day, the river grows stronger, washing sand, undercutting the floor of vegetation —or the water level rises and roots, gasping, drown and release their grip. The river has inherited more logs, more carcasses of d^ad trees. And water washes over the sandbar that was, sun glinting on its ripples, separating light....

Just upstream, wind is dropping seeds on barren sand.

But, though the breeze drops its seed indiscriminately, Sandhill cranes cast a discerning eye to the river and alight on a bare sandbar, sheltered from cold March winds. On the sandbar, cranes find safety from predators, a roosting place where they can rest for the night from their hundreds-of-miles-long flight from the south. As dawn touches them, they will fly to surrounding grain fields to feed and to court. The courtship rituals are confined to the Platte Valley, where the birds choose mates before flying north to breed and nest. It is a spectacle repeated nowhere else in the world. For those few weeks in spring, the cry of the cranes tantalizes their land-bound viewers who wheel and mill only in their imaginations.

And sun flashes on outstretched grey wings,

giving them an ethereal white cast, separating light....

Wheeling and milling, cranes drop ever lower, skimming the tops of cottonwoods, casting shadows on tangled underbrush where mice and rabbits hide from hawks and owls. Muskrats dig for fleshy roots along the riverbank, and mink feed on muskrats, mice, and fish. Raccoons calmly wash their clams, catch their fish and pick their berries in full view of the muskrat's tragedy.

Under the open canopy of cotton wood, ash and boxelder, dogwood and sumac tangle with bittersweet, Virginia creeper, poison ivy and wild grape. Squirrels race up and down sprawling trees, gathering buds and twigs to line their tree-top nests. Here a hollow tree may house an oppossum, there a songbird nest. Kingfishers fly back and forth between river and trees, catching their break fast en route.

Sunlight streams through the treetops onto thick grasses and shrubs. Here are the berries, buds, twigs and bugs to feed hungry birds and squirrels and rabbits.

A dragonfly skims the water standing outside the trees, away from the river —a puddle left high, though not dry, by the changing course of the river. Sun glints off his body, reflecting blue and a touch of green, separating light....

Rushes, sedges, cattails and mosses soak their feet in standing water. And somehow, the vegetation is followed by animals. Fish, snails, crawdads and clams discover food essential for their survival.

Beyond the marsh and beyond the trees and shrubs are the grasslands —the prairie with its intermixture of wildflowers. The contour of the land is higher here, the water table lower. Hot winds and sun dry the plants and sap their strength, but again the race for life brings adaptability. Throughout the growing season, prairie flowers, each in their own turn, rapidly thrust up stalk, bloom, develop seed and disappear. Their presence or absence is hardly noticed. Killdeer and doves nest among their tiny blossoms, feeding on the seeds and insects that creep and crawl and buzz between tender stems of grass and weeds.

But look at it from a gopher's eye view. Under ground is a magnificent balance of root systems, intertwined in their reaching for life-sustaining moisture. Some have sturdy tap roots like the compassplant, some spread close to the surface as a blazing star. Others, like Missouri goldenrod, grow and spread on rhizomes and surface roots. Each is in harmony with the other, and with the gophers, badgers and moles that feed on their roots.

Cottontail cautiously peer from brushy cover, then carefully hop onto the grassland, nibbling on dandelions, wild beans, vetch, and white clover along the way. Mice scurry through tall grasses, hidden from predators, chewing grass and wild flowers. Birds and mice are attracted to foxtail, ragweed, sunflower, and hemp seeds, while coyotes and foxes are attracted to the mice and rabbits.

In dawn light, a doe and fawn slip silently through the shrubbery at the edge of the trees. Russian olive, red cedar and mulberry mix with wild strawberry, dogwood and ground ivy. Quail and pheasant, concealed at woods-edge, awaken to the deer's near passage. Gracefully moving through the trees, the fawn breaks a spider web glistening with dew....

Revised Check-list of Nebraska Birds, available from University of Nebraska State Museum Handbook of Nebraska Trees, available from Conservation and Survey Division, University of Nebraska Nebraska Wild Flowers, Robert C. Lommasson, available from University of Nebraska Press Nebraska Range and Pasture Grasses, available from the University of Nebraska, College of Agriculture and Home Economics Extension Service

A SUMMER REMEMBERED

Our family had good times and bad, but the disappearing chickens and cows was a matter of special crisis in all our lives THE OLD HOUSE stands west of the windmill. A number of sheds and cribs are scattered about the yard. Lightning had burned the barn many years ago. The screened porch is hang ing by a thread on the decaying house. Weeds and wild flowers are growing everywhere.

Now, I sit here by the old windmill. So many times I drank the crystal clear water. I can still feel its coolness on a hot summer day after I had come in from the fields. The old mares would be as tired as me from pulling that walking plow all day. I remember the summers the most. The hard work, the love, and the heartaches we shared, the folks and us four kids.

Than I'd hear Ma's voice calling me from the porch...

"Lee! Get Pa in here and let's eat. Supper's on. And find Frank. That fool youngin' is suppose to be doing the chores, and he's off on that darn pony of his again."

Frank's my younger brother. He'd of been about six then. I was ten years older than him. And if there was trouble afoot, he'd sure step on it. More'n likely he'd be down by Stoner's Creek catching frogs.

Ma would be standing by the old cook stove. Sweat pouring down her fat cheeks. For the life of me, I don't know how she stood the heat. She never complained. If she wasn't fixing meals, she was washing for the six of us on an old scrub board, mending, and cleaning. In the summer, she'd be canning all day, and storing the glass jars of fruit and vegetables in the fruit cellar for winter eating.

Ma would pause from her cooking and wipe her wet face with her apron, and tuck the loose gray hairs back in the big bun she wore on the top of her head.

"You kids get washed. Just look at you Frank, you're a sight. Mud from head to toe."

"But Ma, I can't sit around the house all day do ing nothin' like ole' sissy Maybelle."

"Oh, shut your mouth Frank! You're just jealous cause you're not a girl."

"You kids quit your fussin' or I'll whip you both." Pa'd say. "May, stop pesterin' Frank and set the table for your Ma."

I liked sitting around the big round wooden table. Ma always had a red and white checkered tablecloth on it. We'd talk about how the day's work had gone, and what needed to be done the next day. But mostly our talk was about the war in Europe, and the United States getting into it. Ma used to worry about my older brother Jess going off to war. He'd have been about twenty then. Most of the time Ma or Pa didn't know where he was. He didn't like farm work. He and Pa had a big fight early in the spring, and he left to work in town. Pa never talked much about him, but we all knew Ma had a terrible ache in her heart worrying about him. My cousin Willy Krause told me he had seen Jess and Herman Kline at the Cedar River when he was fishing one day. They were carrying on with the O'Ryan sisters. There was a lot of talk about those girls. How wild they were and how their poor Ma couldn't do anything with them since their pa died the year before. The girls had long, flaming red hair and blue eyes. Thinking about how beautiful Georgia was, I almost envied Jess.

Ma asked if any of us kids had heard any noise outside last night. We hadn't, but something was bothering her.

"I think somethin' or someone is gettin' my chickens."

Ma and her chickens. Big ole' Plymouth Rocks. She took great pride in those chickens. The eggs she sold were our source of grocery money in the summer. And she had noticed quite a few of her hens were missing.

"I'll tell you Pa, if you hear anybody out there messin' around my chicken coops tonight, you get your gun out, 'cause no damn thief is gettin' my hens."

Pa'd listen to her and nod his head. Everyone around here knew Pa was a crack shot.

Pushing his chair away from the table, Pa said, "Come on boys, gotta get the chores done before it gets dark. Looks like it might rain."

The night was hot and sultry. Just like Nebraska weather when a storm was coming. You could smell it in the air.

"Let the cows out of the barn Frank, and take the harness off those horses," I said. "They've cooled off enough now so you can give them a drink from the water tank."

I can still see Frank waddling toward the water tank. His short legs moving at a snail's pace. The legs of his bib overalls dragging on the pure black earth. The wind was coming up now, and the dust was hitting me in the face as I walked out of the barn. Ma was rushing around shutting up the chicken coops, and Maybelle was taking the clothes off the rusty wire clotheslines. (Continued on page 47)

Because of new environmental education programs, children are

Learning to Care

I am a plant and I have a headache. The way I feel about living here is awful. Today a kid tried to kick me out of the ground. Last night after school about a hundred kids ran over me. A week ago I got cut in half by the lawn mower. About two minutes ago a speeder went up the curb and ran right over me. Two seconds later the police ran over me too. I'm having a hard time with all these humans around. Billy Cleland Hartley Public School, LincolnTHROUGHOUT history, mankind has had problems to face and conflicts to wage, yet they all pale in comparison to a situation that man has brought upon himself and all other creatures of the earth. That is his degradation of the environment to the point where life is threatened for many creatures, including man.

Only a changed attitude can correct this cataclysmic trend, and perhaps only enlightened youngsters can turn the tide. To accomplish this end, environmental education must become an integral part of our lives. But just what is environmental education? To under stand or define its meaning, it may be necessary to find what it is not.

Environmental education is not teaching students to name every plant and animal on the North American continent. It is not strict nature study. It is notthe making of a scientific memory bank out of a student; remember our scientific knowledge doubles every 4 years. We program computers as memory banks, not our young people! Environmental education is not science, art, music, math, social studies or language. It is not a one-day trip to a natural area or a week at an outdoor camp.

Puzzled? Well, let us try to discover what environmental education is. It is a study of man with nature (the "Natural" system), man with man (the "Human" system), and man with himself (the "Ego" system). It is the study of the interdependence of all these systems and how the quality of each of our lives is affected. Remember, nature can live without man, but man cannot live with out nature. Environmental education is the development of thinking skills and processes. It is art, science, math, social studies, music and language —it is multi-disciplinary and must be in all classes. Environmental education is concern with action. Environmental education allows for enlightened deci sion making and problem solving as to the quality of life in the future.

To discover a need for environmental education is to recognize the problem. Are the problems we face today air pollution, water pollution, declining wildlife numbers, smog, pesticides, decreasing habitat, etc., etc? Or, are these just symptoms of the real problem, just as a cough or sneeze is a symptom of a cold? Well then, is the real problem a socio-economic system? It is a fact that we live in the most wasteful nation on earth. We are 6% of the world population but use 30+% of the world's energy. Our standards of living are high! Could they be too high? Our limited natural resources are running low. Our wants seem to be infinite but our needs are finite. When should we separate needs from wants?

But what is a system but a group of people. What guides our behavior? What makes us the most wasteful nation on earth? Do most people care? Now we are beginning to understand the real problem. Most people don't care; if they did our very existence on this planet wouldn't be threatened as it is today. Why are most people apathetic, only a few concerned, and fewer yet follow up with appropriate action. It seems that we are all in this together. We base our decisions on ethics and attitudes that we have developed over time. In simple terms, some people feel it is alright to pollute a river and some don't. Most times the green dollar signs cloud the mind; the "right" thing is not done.

"Now it seems that we have met the enemy, and the enemy is us." We must develop an environmental ethic that will give us that quality of life in the future.

The Game and Parks Commission

recognized many of these problems

and saw the need for environmental education in our public schools and thus

developed a program for middle elementary students (grades 4-6). The program is designed to do many things, the

least of which being the exposure of

the student to stimuli about and from

his environment. This program is not

science limited in scope but is developed to expose the student to integrated and interdisciplinary facets of

the environment he or she lives in. It is

this exposure that will hopefully manifest itself in the conscious development

of an environmental ethic. This program does not stop at the end of packets

and physical curriculum material, but

is designed to instill an awareness and

appreciation of the environment, thus

creating endless possibilities for future

learning activities. The program's purpose is both informational and attitu

dinal in nature in that it does not limit

the student to the stagnation of only

scientifically oriented measuring, observation

38

NEBRASKAland

FEBRUARY 1974

39

and memorization. Instead,

this program attempts to open up new

areas of environmental consciousness

that includes ethics, relationships of

social nature and concepts of self. It is

therefore logical that the scope of the

program be something more than

strictly information.

and memorization. Instead,

this program attempts to open up new

areas of environmental consciousness

that includes ethics, relationships of

social nature and concepts of self. It is

therefore logical that the scope of the

program be something more than

strictly information.