NEBRASKAland

January 1974 50 cents 1 CD 08615

NEBRASKAland

VOL. 52 / NO. 1 / JANUARY 1974 Published monthly by the Nebraska Came and Parks Commission. Fifty cents per copy. Subscription rates $3 for one year, $6 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. commission Chairman: William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Vice Chairman: Gerald R. (Bud) Campbell, Ravenna South-central District, (308) 452-3800 Second Vice Chairman: James W. McNair, Imperial Southwest District, (308) 882-4425 Jack D. Obbink, Lincoln Southeast District, (402) 488-3862 Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-centra! District, (308) 745-1694 Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 Director: Willard R. Barbee Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, Jr. Assistant Director: Richard J. Spady staff Editor: Lowell Johnson Editorial Assistants: Ken Bouc, Jon Farrar, Faye Musil Photography: Greg Beaumont, Bob Grier Layout Design: Michele Angle Farrar Illustration: C. G. Pritchard Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1974. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska Travel articles financially supported by Department of Economic Development Ronald J. Mertens, Deputy Director John Rosenow, Travel and Tourism Director JANUARY 1974 Contents FEATURES PUMPING UP PIKE "SIT DOWN AND SHOOT" 8 HOUSES OF HISTORY12 THE ROLE OF THE PREDATOR 14 NEEDED... NEW SYSTEMS & ETHICS OF HUNTING 18 WONDER OF LOOKING CLOSE 20 STRAW-BALE PHILOSOPHY 30 HOLDING THE PEAKS 32 FISHING BAD? GO HUNTING 34 BOBBING FOR LIFE 38 DEPARTMENTS SPEAK UP 4 TRADING POST 49 COVER: While snow may help some predators more than the coyote, this shrewd hunter readily adapts to almost any situation or condition. OPPOSITE: Snow and cold also influence the landscape, making it stark or scenic. Photographs by Greg Beaumont and Bob Grier.

Speak up

Calendar GiverSir / We're always in the market for news, but the news we heard today was very disappointing. It went as follows: "No, we're sorry there will be no NEBRASKAland Calendars this year". "What? No NEBRASKAIand Calendar? But we use them as Christmas gifts to last all year with happy birthdays, anniversaries, and special days noted on them," I said. Anyone, just anyone from here to Florida or California or anywhere would be proud to have it hanging anywhere, as not only a reminder of dates and special days, but of the beauty of Nebraska.

Suppose it is too late for this year, but what can be done to help prevent this occurrence again next year? You just can't imagine how many disappointed people there are going to be. We've kept ours since 1967 because they are too nice to throw away. Please explain via Speak Up why discontinuation has become necessary.

Mr. and Mrs. Joe Booth Walton, Nebr. Calendar WatcherSir / I am extremely distressed at your decision to discontinue publication of the NEBRASKAland Calendar. I would appeal to you on behalf of all displaced Nebraskans to reconsider. Everytime I look at my calendar I come home again. If you have to, raise your price. Double it if necessary. I want to come home a little bit every day.

Val Schmiedeskamp Inglewood, Cal.The Nebraska Game and Parks Commission only reluctantly decided to discontinue the NEBRASKAland Calendar. It is NEBRASKAland merely a case of economics where increased printing, paper, mailing and handling costs would have forced prices all out of reason. Unfortunately, our general public does not feel as you do about prices and this agency can no longer subsidize the product as it has in the past.

The Game and Parks Commission has a long history of being one of the most starved agencies in Nebraska government and is facing fish, wildlife and recreation management problems of unparalleled proportion. Therefore, we must put our budget to other purposes.

Jim Wofford, chief, Information and Education Bird WatcherSir / Following is a poem about the yellow warbler and the brown-headed cowbird:

TWO MOTHERS One lurks about the other's tender nest in wait until that trusting owner leaves. Mother warbler, ignorant of thieves and murderers, her pure heart never guessed. Unconscious, then, of deep plans to molest the sweetest treasure that a bird conceives, the warbler goes...and cowbird, comes, achieves within a moment her malicious quest: One precious egg of four there warm she throws outside the nest, and lays instead her own among those left; then off she flies again; Soon her hatched offspring's larger beak will groan with food this parasite will snatch from those whose rights are crushed and future prospects dim. Ms. Doris Wight Baraboo, Wis. Flying ReadersSir / Our friends fly out for pheasants every fall-your NEBRASKAland has been read by many as I take it to the office and then on to the hospital-all are complimentary. Friends far away in South Carolina commend you on your articles and pictures.

Dr. and Mrs. J. E. Jacobs Myrtle Beach, S.C. Likes RingnecksSir / I have always felt the NEBRASKAland Magazine to be among the very best of its kind in the nation. Your October issue certainly was no exception. The article on "The Ring-Necked Pheasant in Nebraska" was a masterpiece.

It's seldom one sees such an in-depth study of a given game bird or animal as you have presented to the reader. This, coupled with the high degree of excellence in JANUARY 1974 photography, made it a most valuable piece of literature, I felt.

The excellence of your magazine compliments what I feel to be one of the better game commission agencies in our country.

Fred Lambley Albion, Nebr. Kind WordsSir / You have many fine issues of NEBRASKAIand. Your October 1973 "Pheasant Special" is one of the finest pieces of work that I have observed in any state publication. It is one that our Game Commission, our Governor and all sportsmen of Nebraska can be most proud of.

Jack Cole, President Wildlife Development Federation of North America Lincoln, Nebr. Follow the SmellSir / I would like to find out what the ingredients are for shad gizzard. The stinkier the better. I would like to try my luck at preparing some bait of my own. Would be pleased to hear from some old timer on this subject. I have been a NEBRASKAland customer for years.

Samuel Schleicker 2232 W. 11th St. Grand Island, Nebr. Little Log SchoolSir / This last summer I visited in Nebraska, my home state, and found in a number of homes the NEBRASKAland Magazine. I thought it a great magazine. In the July 1972 issue on page 18 there was a picture of a log building near the Niobrara River. You referred to it as an old settler's home. It was built before the turn of the century as a school house and was used as such for many years. I attended school there in 1904 and 1905 then later taught two short terms of school there in 1911 and 1912. It was used as a school house up until the early 1920s. I was born and reared 6 miles down stream from this building and visited in the area the past summer. My father, Wilhelm Anderson, deceased, was an early pioneer settler to that part of Nebraska.

Emma Schilling El Cajon, Calif.NEBRASKAland Magazine invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to Speak Up. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters. — Editor.

Using a windmill to move bait to attract fish was a logical innovation for a Sand Hills rancher. The results have been good, and he figures most days angling are successful, even if the catching may be slow.

pumping up PIKE

IT HAS TAKEN Ron McConkey many years of ice fishing for northern pike to discover one essential truth—"About the time you think you have the pike figured out hell prove you wrong. That's the only thing I'm certain about."

A Nebraska Sand Hills rancher, Ron speaks with a smooth, Western accent and moves slowly with no wasted motion. From his ranch, located in the rolling hills 12 miles north of Oshkosh, it's only a 16-mile jaunt to the Crescent Lake National Wildlife Refuge. Sprawling over 46,000 acres of sandhills and encompassing more than 20 lakes, the refuge is a mecca for migratory waterfowl, deer, antelope, and a host of smaller birds and animals. Far removed from the beaten path, the refuge is little known and visited by few persons. However, the refuge provides Ron and other area residents with some prime pike fishing.

If any day of fishing can be called typical, February 9, 1972 was a typical day for Ron. By 8:30 a.m. his ranch chores were done and he was heading north and east for Island Lake on the refuge. The previous evening Ron had seen Alvin "Curley" Krajewski, a local carpenter and avid ice fisherman, in town.

"You should have been at the lake today," Curley had said. "Bob Miller from Lisco got an 18 1/2 pounder. Measured 39 inches." "Where did he get him?" Ron asked with interest.

"Right where we've been fishing. What do you say we try it for a while?"

"I couldn't make it today, but I think I can slip out for a while tomorrow." Ron said.

"I'll see you there then."

A whirlwind of dust ran down the road ahead of Ron as he topped the rise and looked down on Crescent Lake. Although bearing the same name as the refuge, the big lake actually is located a mile south of the refuge boundary. Minutes later he arrived at Island Lake and spotted a lone ice fisherman at the extreme south end of the lake. Proceeding on for three-quarters of a mile, he pulled off the road and followed a trail down to the east edge of the lake. There he unloaded his ice-fishing sled, a conventional snow sled with a permanently mounted plywood box. Easing the sled through the rushes that fringe the lake, he stopped where the vegetation ended and open ice began. Strung out along the edge of the reeds were a series of holes which Ron had been using all winter. The ice auger bit through the newly formed ice in each hole quickly and soon fifteen were open. Returning to his sled, he began rigging his tipups. They were tipups like few people have ever seen. Ron had designed them, built them, and even obtained a patent on them.

Hours on the ice and long winter nights at the ranch had given him time to think about ice fishing for pike, and to analyze conventional tipups. He had decided the conventional models had some major shortcomings. First of all, they relied on the fish to hook himself, or for the angler to race to the hole in time to set the hook before the fish figured out something was wrong. The second problem came after the fish was hooked. The free-wheeling reels on conventional tipups often allowed a fish to get slack line, and once a big pike gets slack he can often part even the stoutest of lines. When Ron heard of the automatic reel, he knew he had the answer. Widely used in the South for catfish bank lines, the reel works on the same principle as a window shade, allowing line to be taken out but keeping tension on it, and retrieving line when the fish turns back. Incorporating these reels, Ron had an effective tipup.

However, fishing on the refuge posed one additional problem. Most anglers ice fishing for pike prefer live chub minnows or bluegills for bait. The baitfish swims about and attracts northerns from a distance. However, life fish cannot be used for bait on the refuge. A strip of liver on a treble hook with a Colorado spinner above it had proven to be the most effective bait. Unlike live bait, though, it hung motionless in the water and did little to attract pike. Jigging helped, but it was impossible for a fisherman to wiggle 15 tipups at one time.

Ron doesn't remember when it hit him. Maybe it was one night while driving home from the refuge when he saw the windmill atop the hill —why not put the wind to work to jig the bait? Experimentation paid off. The six-inch fan blades from old car heaters proved ideal. With each revolution of the blades, the Colorado spinner flashed up and down. Collecting more fan blades, he soon had all of his tipups equipped with the "miniature windmills".

Island Lake is shallow and the water along the reeds averages only three to four feet in depth. Ron drops his bait to the bottom and then raises it about six (Continued on page 47)

"sit down and shoot"

THE EASTERN SKY was barely beginning to glow with the approaching dawn as ! stopped the car in front of the Monty Weymouth residence in Chadron. It was the opening morning of rifle antelope season, and the first big-game hunt for Monty's wife, Glenrose —Glen to all who know her.

Photographs by Bob GrierMonty had mentioned his wife's growing interest in hunting earlier in the year, and the invitation to join her first hunt was gladly accepted.

Monty and Glen could easily be described as an outdoor couple. They've hiked, camped, and canoed over most of the country. Monty runs the sporting goods section of the family store in Chadron, and besides hunting, takes an active interest in photography, archery

Glen, besides her outdoor activities and three children, is one of the finest cooks this side of the Yukon. No trip to the Weymouth home is complete without a meal of sourdough pancakes topped with homemade syrup.

Monty has been hunting since child hood, but for Glen, this would be a new experience.

Ask everybody what they think of sport hunting, and in most cases their responses and opinions can be traced back to their early experiences. The first hunt goes far toward shaping ideas and gaining satisfaction in the sport. It was the opportunity to record such a first hunting experience that had brought me over 400 miles from my home in Lincoln.

Chadron is in the center of prime pronghorn country. Bounded on three sides by rolling hills of prairie grass and endless stretches of ranch country, only the rocky buttes of the Pine Ridge south of town are without the fleet, sharp eyed antelope.

Herds of antelope can be found south of the ridge, though. Here the prairie meets cultivated farmlands and the large alfalfa and wheat fields attract the feeding animals.

After a hearty breakfast of sourdough pancakes and later a quick stop to pick up young Mike Schuhmacher, we started bouncing across a well-worn cattle trail into the back reaches of the Schuhmacher ranch.

For someone not familiar with the country or antelope habits, the quick est route to success is to have a native of the area ride along. Besides his knowledge of the antelope and their whereabouts, Mike knew the roads and fence gates that would have to be crossed to get there.

"Glen and I scouted this area last week," Monty said. "There are some pretty good heads in this pasture."

That brought Glen's attention back from the now-red eastern skyline.

"I'm after one that will fit in the freezer," Glenrose said. "You fellows can hunt for a trophy all you want, after we get one for the freezer!"

As the first crimson rays of sunshine skimmed over the sage and grass be low us, Monty brought the vehicle to a stop and began a close inspection of the rolling hillsides with his spotting scope.

10 NEBRASKAlandHere and there a lark broke the silence with an even-spaced musical call. Below, a large skunk ambled across a sage-dotted flat, his black coat in glistening contrast to the magenta tinted ground cover.

"Just getting out on a morning like this makes the trip worthwhile," Glenrose said. "I love the outdoors. I guess that is the most important thing about hunting to me —having a reason to get out and enjoy the outdoors."

Scanning the far hillside, the spotting scope proved me wrong several times after I pointed out what appeared to be antelope standing in the distance. Relegating the search to Monty's superior optics, Glen and I discussed the several months of preparation that had gone into today's hunt.

"I started out shooting a .222 caliber rifle, which didn't have much kick," Glenrose said. "From there, I went to the .243, both for targets and later at varmints."

"I like to feel somewhat independent," she continued. "I didn't want to feel that I'd be a handicap out here. Monty is a hunting safety instructor for the Game Commission, and I learned quite a bit about guns from my dad too, and it all helped me get ready."

The spotting scope soon found the real thing, as Monty pointed out a doe and fawn antelope feeding more than a mile from the vehicle.

"I think we'll head over that way," Monty said. "Usually where we see a few we don't have to go far to find others. We've seen several good-sized herds in this area, and if we're lucky we might just stumble across the one with that big buck in it."

Again this brought a reminder from Glenrose about filling the freezer before looking for horns. It was plain that she wasn't nervous about her first hunt. In fact, she appeared to be the least excited of the four of us as we slowly bounced over the sod toward the feeding antelope.

The topography of the area made it fairly easy to remain hidden from the antelope's vision as we advanced. Hunting antelope with a car or jeep has led to great excesses. We saw several vehicles attempting to chase antelope to get within rifle range fortunately, the rough hills gave all the advantage to the antelope.

The thrill of stalking antelope on foot —matching stealth against speed, competing with the alert animal on his own ground —is the real sport of antelope hunting. Running a tired buck into the ground with a vehicle proves nothing and is only a problem that the consciencious hunters can help curb. While the actual chase is exciting merely because of the speed and pursuit factors, there should be little or no satisfaction* in such methods. To be called sport, there must be sportsman ship involved.

Snaking our way through gullies and across sage flats, Monty pulled the four wheel-drive rig onto a high, saddle-like ridge and we again glassed along the far hillside.

This time, picking up the tan colored animals was relatively simple, and it wasn't long before Glen spotted two young bucks lying against a small hill, unaware that we were already planning a stalk that would bring us within range.

"They're far from being the biggest bucks," Monty said, "but they appear to be in good condition, and that gully below them offers the opportunity for a close stalk."

"They look fine to me," Glen added, already taking her rifle from the rack. With hurried instructions to Mike to drive the vehicle back into the distance where he could sit and distract the antelope while we continued the stalk, we dropped into the gully and began hiking toward the two bucks.

Because we were out of sight of the two, we took our time crossing the quarter-mile to the hill we had them marked against. Antelope are not noted for a keen sense of hearing; fantastic vision being their primary defense, backed up by a sensitive nose.

To go with his vision and other senses, the antelope is also one of the fastest animals in North America. According to some reports, adult antelope have been clocked at 55 miles per hour, possibly approaching 60 miles per hour for short sprints. Week-old antelope are able to outrun a man, at taining speeds near 25 mph for about a mile, while two-week-old fawns can reach 35 mph.

The wind was in our faces though, and as we moved the last 100 yards I could sense the excitement picking up as Glen readied her rifle. With whispered instructions from Monty, she moved ahead cautiously, stepping slowly toward the crest of the hill.

The two bucks hadn't moved from their beds, but I could see them come to their feet not 75 yards from Glen as she reached the ridgetop. Her first shot, fired offhand as the bucks stood watching, was a high miss, the flying sand where the bullet struck clearly visible over the top of the near est buck.

Her second shot, also offhand but this time at a running animal, connected. The buck was hit just behind the heart-lung area, not sufficient for an instant kill.

"Sit down and shoot from a rest," I heard Monty call as the two bucks ran against the far hillside, the wounded one moving slowly now about 125 to 150 yards away.

Quickly dropping to a sitting position, Glenrose's third shot put the young buck down for good.

Monty, also in a sitting position, brought the other buck down with his first shot, and it fell not more than 40 yard from the other animal.

"I hadn't planned on finishing the hunt this soon," Monty said, looking at his watch. "It looks like we can get the field dressing finished and be back in town before nine."

"I hadn't figured it would be this quick either," Glen commented. "I was ready to hunt at least all day."

"There is still a lot of work ahead be fore you get those two in the freezer," I cautioned. "You do have room for two don't you, Glen?" I chided. "And, before we forget, you two had better tag those bucks."

Mike joined us as we started the field dressing. Glen excused herself from that portion of the hunt, but Monty explained everything as we worked, preparing her for the day when she might have to field dress a deer or antelope on her own.

With the guns back in the car gunrack and the two antelope loaded for the short trip to town, we started back across the rough cow trails.

"Now how do you feel?" Monty asked as Glenrose passed us sand wiches prepared for just such a moment.

"Well, she quickly replied, "now I think I'll start shooting your bow. May be we can get a deer to go with the antelope."

Houses of History

THERE WAS SOMETHING faintly frightening about the officious, three-story building that dominated an entire city block. Its sobering qualities were most apparent at night when black, hollow windows gazed across an ebony lawn and a single, naked bulb illuminated an idle door whose sagging screen rattled like muffled chains in the wind. Even in daylight, with the clacking of myriad typewriters rattling through its ancient halls and into the deepest recesses of its portly bulk, the structure cast a foreboding image. Musty odors of more than half a century of service emanated from who knows where to bexataloged simply as municipal scents.

Still, that curious edifice was a place to be revered. Etched in stone above its ornate entrance, a venerable date testified to the year of its commence ment. The building was a hub of activity as, each day, the business of a bustling Nebraska county was carried on in its multitudinous offices. The courthouse was the place where "they" lived, collecting taxes to support dozens of unnamed agencies and meting out justice to those who crossed county canons. Yet seldom did those who passed consciously regard the building as anything more than a functional, if a bit dowdy, part of government.

Ancient courthouses are virtually disappearing now, replaced by gleaming examples of artistry in concrete, glass and steel. But, there are courthouses in some of Nebraska's 93 counties that still stand un touched by the wrecking crew's bulldozers.

There were courthouses in Nebraska even before it was a state. In 1854, the Territorial Legislature established eight counties to help administer the tasks of government. Each division chose a central location where county board members carried on their duties, frequently using a residence of one of the officials. As time passed, though, special offices were erected. Perhaps the only surviving relic of those early courthouses is still in use at Nebraska City in Otoe County. Built in 1864 —three years before statehood —it is today the oldest functioning courthouse in the state.

Since homes were frequently used as courthouses, it follows that little attention was paid to the type of construction. Architecture ranged from austere to ornate, and building materials ran from masonry, such as at Nebraska City, to rough wood. One of JANUARY 1974 the best examples of the latter stood in Arthur until 1962, when it was replaced with what is reputed to be the smallest courthouse in the United States.

In the early years, Nebraska's population grew from southeast to west, thus establishing an older-to-newer trend in construction dates. Courthouses, it seems, are predominately older east of a north-south line along the western borders of Knox, Antelope, Boone, Nance, Merrick, Hamilton, Clay, and Nuckolls counties. Those west of that line are generally newer, although there are naturally exceptions. In the east, Lincoln boasts a modern sandstone building holding combined Lancaster County and city offices. Built at a cost of about $6 million, the structure is now entering only its third year of service despite being located east of the line. West of the barrier, Kearney's Buffalo County Courthouse was built in 1887, laying low any attempt to categorize eras. Regardless of when a structure was built, though, each has a story all its own.

Trenton, in southwestern Nebraska's Hitchcock County, boasts a modernistic building erected in 1969 without a cent of indebtedness for county residents. What many don't know, though, is the story behind the courthouse it replaced. Culbertson was the original seat of Hitchcock County, and the move to Trenton came in 1906. Residents didn't have a place for governmental agencies. So, until a courthouse was built, offices and records were distrib uted about town in several stores. When the new courthouse was finished, county offices moved in and one of the temporary buildings became a museum of the Hitchcock County Historical Society.

Architectural styles have changed over the years and the towering structures of the. past have been replaced with sprawling, modern buildings. Yet, courthouses at Rushville in Sheridan County, Aurora in Hamilton County, Nelson in Nuckolls County, and many more still rise from the prairie like prehistoric fossils returning to life. Few mortals will think of them as anything more than seedy old office build ings. But, there are a select few who know and appreciate their historic and aesthetic value. They watch the county courthouses of Nebraska most care fully, knowing full well that these stately edifices are vanishing, and with each passing, the remaining few become more singular.

Prairie Life / Role of the Predator

LIFE FEEDS on life. All life on this planet can be traced back to the conversion of light energy from the sun into plant tissue. Herbivores, ranging from microscopic zooplankton to white-tailed deer, graze or browse on plants, and in turn become the food of carnivores. Biologists call this energy transfer from plants to plant eaters to animal eaters the "pyramid of numbers." Although the food chain is longer with some than others, all have a common denominator —the original food is plant material and the animal at the upper end of the chain is a carnivore. Northern pike, red-tailed hawks, coyotes and most significantly, man, are all at the end of a complex food chain.

Predation is commonly associated with the idea of the strong pulling down the weak, of a blood-thirsty animal attacking a helpless or meek one. Probably no other type of animal interaction is more misunderstood or hotly debated.

Few of us feel sympathy for a worm pulled from the ground by a robin, or a mouse captured by a cat, but the sight of a coyote feeding on a deer carcass repulses us. Though all three are one and the same —simple transfers of energy along a food chain —our vision is clouded by social judgements and prejudices.

Paul Errington, one of this century's foremost authorities on predation, made the following comment regarding man's view of the predator:

"...I do not see that predation is anything to be judged by human moral standards at all. As a way of life, it reflects adaptations of animals for living, and it is the only way that countless species of animals can live. There is little nonhuman predation that is deliberately cruel. What we call cruelty in these relationships is far more likely to be manifestations of...animals living their lives in their own ways."

Before man exerted such a strong influence on the environment, before the cattle ranches and cornfields, the predator's role was well defined. The predator then was a necessary link in a complex natural system of relationships and inter-relationships. For a large part of our own species' history we were the same; another predator. Roles have changed; though the wolf and man are still both predators, we call ourselves civilized now. No longer do we hunt bison with bow and arrow. Now we raise corn to raise cattle which in some obscure way that is best overlooked, end up attractively packaged in the supermarket. Man has changed the environment and thereby changed man's role in the environment. The basic conflict in the predator question today grows out of this change —we no longer seem to have room for other predators.

Perhaps, though, our disdain for an animal that lives by killing, the same as we do, is held over from our not too distant past when some nonhuman predators were potential threats to our very survival and all were competitors for food. We are no longer threatened by other predators, and most reliable information indicates that there is no serious competition for food. Yet, in many minds, the predator remains a threat to be eliminated.

To better understand the role of the predator in the complex ecology of the prairie we must first know how they live, what they prey on and how they influence prey populations.

One ecologist proposed that there are five basic types of predation. He used "chance" predation to refer to an accidental meeting between predator and prey. "Habit" predation results from chance predation being reinforced often enough so the predator begins to take that prey species regularly. "Sucker list" predation is the taking of unwise, careless prey. Culling the unfit, crippled or diseased members from a prey population is called "sanitary" predation. And, the fifth type of predation he itemized was "starvation" predation, which is the killing of prey forced into the open by inadequate habitat or food.

Sanitary predation, he suggested, had a beneficial effect on the prey population in that it prevented in ferior individuals from breeding and weakening the genetic quality of the population. Elimination of the unwise and those forced into the open by starvation is likewise desirable since the hardiest and most clever prey individuals survive and pass their traits on to future generations. Chance predation is an uncommon form of predation and the number of prey taken is generally insignificant. Habit predation, on the other hand, can have a deleterious effect on a prey population, but it, too, is generally of a local nature. Overall, then, it would seem that natural predation plays an important role in maintain ing the quality of a prey population by weeding out the inferior in dividuals.

Among many vertebrate populations, predators take most or nearly all the individuals of the prey species once they exceed a certain minimum number, generally determined by the quality of the habitat or social tolerance. This type of predation is commonly called compensatory predation since prey populations compensate for their losses by in creased litter sizes and greater survival of the young.

A typical example of this form of predation might be red fox preying on meadow voles. As the meadow vole population grows beyond the point where there is sufficient cover to provide escape, fox skim off excess individuals. When vole numbers have been reduced low enough so that more energy is expended by the fox to capture additional voles than is gained in eatingthem,thefox must either move to a new territory or switch to a new prey species.

To simplify things, we could think of predators as being of two types — generalized and specialized.

The red fox and the great horned owl are generalized predators. They are capable of capturing many types of prey. When the usual prey species becomes so scarce that it is no longer profitable to capture it, they simply switch to another prey. The original prey generally responds with increased litter size and survivability until its population again commands the predator's attention.

Specialized predators, on the other hand, have specific adaptations for capturing certain types of prey. The osprey is a specialized predator. It has evolved into a form specialized for diving into water to capture fish. If for some reason all the fish disappeared from a lake it was feeding in, the osprey could not adapt to capture field mice. It would be forced to move to a new territory where fish were more abundant.

Many variables go into determining the odds that a prey animal will be taken by a predator. Availability of food and cover, movements, habits, size, strength, age and season are but a few.

Probably the single most important factor in determining prey susceptibility, though, is quality of habitat. In general, losses to predators of a well-fed prey population in a suitable environment will be negligible. Predation is heaviest on the fringes of the prey population's ranges. This would mean that predation could be expected to be more of a factor in influencing the number of quail in central Nebraska, where the habitat is poor, than in southeast Nebraska where the quail habitat is excellent.

Where escape cover is adequate and in close proximity to food and water, mortality from all factors, including predation, will be reduced to the point of having little effect on the prey population as a whole. Research has indicated that with most prey species, especially upland birds like the pheasant, attempts to in crease game numbers are more likely to meet with success if habitat is improved, rather than predators being controlled. Controlling predators in this type of situation is like trying to cure a disease by treating the symptoms rather than the cause.

Factors other than habitat, though, are at work making certain species or individuals more or less vulnerable to predation. Periods of courtship and rearing of young are times of high predation. Grouse displaying in the spring or cottontail rabbits on a nest are more likely to be discovered and taken by a predator than

they would be in the fall. Birds that

flock in the winter, like the bobwhite

quail, are more susceptible to predators than during the summer when

cover is heavy and the birds are dispersed. Animals that blend with their

surroundings are less subject to

predation than brightly colored ones.

Young and immature animals are

taken by predators more regularly

than are adults, and larger animals

generally have better chances of not

becoming a meal than small animals.

they would be in the fall. Birds that

flock in the winter, like the bobwhite

quail, are more susceptible to predators than during the summer when

cover is heavy and the birds are dispersed. Animals that blend with their

surroundings are less subject to

predation than brightly colored ones.

Young and immature animals are

taken by predators more regularly

than are adults, and larger animals

generally have better chances of not

becoming a meal than small animals.

While it is obvious that predators kill other animals in order to survive, and that they occasionally take game animals and livestock, the degree and effect on prey populations is a hotly debated subject.

Perhaps the best known example of predator effect on prey populations was provided by the Kaibab deer herd of New Mexico in the early years of this century. Because of a desire to protect the deer on this newly established preserve, cougars and wolves were largely eliminated by shooting and poisoning programs, and deer hunting was prohibited. When the preserve was established, it supported a herd of approximately 4,000 animals. After 17 years of extensive predator control and no hunting, the deer population was estimated at 100,000. The range was incapable of carrying so large a population, and within two years it was severely overbrowsed. In just six years, over 80,000 deer died of starvation. Another 10,000 died before the population leveled off at 10,000 animals —a population compatible with the range. The role of the predator in maintaining prey populations at a level in balance with environment was clearly illustrated.

A research study during the 1930s in New York state shed some interesting light on the predator's effect on populations of game birds, in this instance ruffed grouse.

Grouse populations were studied for two, two-year periods; one when grouse were in an upward trend and one during a general decline. In one area predators were killed out and in another they were left at their normal levels. During the period when grouse were on the upswing, the area with a full complement of predators showed a greater increase in grouse than the one without predators. During the second period, a time of grouse decline, the areas without predators experienced a greater decline than the areas with normal predators present.

The results of this study indicate that grouse not only failed to benefit

A more recent study on the effect of predators on game birds was just completed in South Dakota. Four, 100-square-mile study areas were established across the state and divided into units of varying degrees of predation. In some only fox were reduced in numbers, in others predator populations were left at normal levels, and in a few units, all predators were reduced.

Results of the study showed that in areas where the red fox was the only predator controlled, the in crease in pheasant numbers was in significant, only 19 percent. In units where all predators were reduced substantially, pheasants showed a dramatic increase of 136 percent.

From their data, South Dakota biologists concluded that an intensive fox-only control program held little promise as a means of increasing pheasant numbers. On the other hand, a multi-species predator control program could be highly effective.

They also concluded though, that the cost of controlling all predators, $41 per square mile per year, would far outweigh the increased return realized from more pheasants.

While the effect of predation on game populations is a much debated subject, it is largely an academic one. Little has been done one way or the other except for those of oppos ing views to shout at one another. The same is not the case for the dis pute over predation and its effect on the livestock industry. Though little has been done to investigate the actual effects, largescale programs aimed at controlling predators on livestock raqge have been with us since the early part of the 1900s.

In this country, the first large, government-sponsored predator control program came into existence during World War I in an attempt to increase food supplies to meet the needs of our armies and allies. The war lasted but a few years, governmental predator control is still very much with us. The operation grew during the 1920s and the 30s into the Division of Predator and Rodent Control in the Department of Interior. In the 1960s it was reorganized, in name at least, as the Division of Wildlife Services under the Department of the Interior's Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife. Today, this division employs a staff of over 600 and operates on a budget of some $8 million, of which over three-fourths is spent on predator control in the western states. Predator control is still a very big business, a tax supported business.

Few dispute the fact that large predatory mammals, primarily coyotes, do occasionally kill do mestic livestock. The extent of these depredations, though, is generally believed to be overrated. Because predators are quick to find dead animals and most make little distinction between freshly killed meat and carrion, they are often unjustly accused of making kills that they merely happened onto.

With the awakening of an environmental awareness and growth of appreciation for all facets of the wilderness has come a questioning of the ecological, economic and ethical justification of predator control, as well as many other practices that have too long been accepted as necessities for this country to grow bigger and stronger. Values other than dollars are now beginning to influence policy making. But that is another, larger story.

With few exceptions, predatory animals in North America are not in danger of extinction. Not because we haven't done everything imaginable to bring that about, but largely because of their adaptability and tenacity. The entire question of predator control should not be one of economics but of morality. Is the indiscriminate poisoning of predators morally right? What price will we pay for the senseless or selfish disruption of the environment's delicate balance?

The role of the predator in the environment does not need to be justified, only understood. The predator, in his natural role, should be thought of as an ally— occasionally as a competitor—never as an enemy.

NEEDED ... NEW SYSTEMS ETHICS OF HUNTING

RECENTLY I received from Czechoslovakia a large, well-illustrated book called The Beauty of Game Management. It has dozens of superb photographs of wildlife, dogs, and hunters that illustrate in an inspiring manner the Old World atmosphere of hunting. Of particular interest is a street scene in a fairly large town where hundreds of animals have been placed with precision, side by side, and a crowd has formed to pay respect to the harvested animals. It is "Game Management Day".

Can you imagine such a scene in Vancouver, or Victoria, or anywhere else in British Columbia, or the rest of Canada? What would the press and the public have to say?

Why the difference? What have we done to create increasing disrespect for our sport, lose confidence of landowners and be held in low esteem by the public? Well, for one thing, we have allowed a communication and credibility gap to develop with the non-hunting public. We have a lot of fences to mend. Many hunters are sitting back, assuming that their game department will take care of their interests when, in fact, every single hunter must assume this serious responsibility.

The people who criticize us for hunting appear only to see the irresponsible acts of a small minority of hunters, their understanding of the contribution we make is sadly lacking in most cases. They do not realize that if their children are to enjoy the beauty of wildlife and a healthy outdoor environment, they must stop thinking about the comparatively few animals the hunter shoots. Instead they must focus on the thousands of animals that die from damaging changes to their environment, changes such as power dams, poor logging practices, indiscriminate use of pesticides, urban sprawl, and over-grazing, to mention a few. For years hunters have fought to prevent such damage, and when prevention isn't possible, to at least lessen its effects. But often they get little or no support from their critics and no appreciation of the vital importance to wildlife conservation of the millions of dollars that come from their pockets.

As a professionaJ conservationist and ecologist, my reaction to well-meaning people who write letters to news papers and to game departments and who exploit the emotions of neutral people against hunters ranges from amazement to utter disgust. This is aggravated by the fact that we hunters are incredibly reluctant to speak up and tell people about game management, why we hunt and what we are doing to preserve wildlife. In telling people what we do for conservation we must remember, however, that many people care more about how we behave than what our dollars will do.

For this reason there is a need for us to stand back and look at our ranks, because in these ranks are hunters who are damaging our image. Let's go back to that street scene in Czechoslovakia and see how we compare, as a group, with hunters whom people appear to respect. Our European counterparts achieve the privilege to hunt, not by money alone, but through a degree of physical work, a personal interest in game management and through the priority they place on hunting in comparison with other choices for their leisure time. We, on the other hand, seem to take hunting more as an inherited right rather than a privilege.

This attitude is particularly noticeable in that minority element that causes us the most trouble. These slobs (as they are often called) complain about the license fee, display their guns like bandits, all too often act as if they're a part of a New Year's celebration, then drive home with a carcass prominently draped over their vehicle. Some image! The fact that only a handful of hunters behave this way is of no special consequence. One example of bad behavior is all that is needed to develop a case against every hunter, particularly when the listeners are receptive to the idea that hunting should be prohibited. One offensive act becomes magnified out of all proportion, especially to some sensitive person in a highrise apartment, or the lady across the street. They are easy converts for the crusader who, for varying reasons, may benefit from identifying us as murderers.

The lack of support for the North American hunter is undoubtedly associated with the common property attitude and tradition we have grown up in. On this continent we are all free to hunt with few obligations. As a consequence, we probably have many thousands of hunters whose desire to hunt is (Continued on page 48)

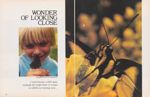

WONDER OF LOOKING CLOSE

I must become a child again, unsheath the bright blade of wonder to whittle my learning away...

20

The ancient Chinese went to the mountains to contemplate man's place in nature. Greeks philosophized among their students in Athens. But Joe Hyland and I test our theories of the universe in a duck blind north of Edgar.

HOW YOU FEEL about doing certain things depends a whole lot on how you feel about the people you do them with. I guess that is why I've always thought hunting ducks was some thing special. Over the dozen or so years I've spent crawling up on pond ducks and making rather primitive attempts to call in river ducks, I've been luckier than most in the company I've kept.

Opening day of the 1973 duck season was no exception. Come 7:20 a.m. I was sliding off the corner of a straw bale in a nifty homemade blind just north of Edgar in south-central Nebraska. Sliding off the other end of the bale was Joe Hyland, and sitting high and dry on the middle three fourths of the bale was Joe's son, Eric. Joe's six-month-old black lab pup was alternating between snoozing at the side of the blind and retrieving an inflatable decoy it had taken a liking to.

I had left Lincoln at 4 a.m. that morning in on-again, off-again rain. As I wove in and out of the showers the radio was still echoing weather forecasts issued the day before — sunny on Saturday with highs in the lower 80s, becoming cloudy Saturday night with a 30 percent chance of light showers; Sunday clear with the highs near 80. As I pulled up to Joe's inlaws' house I chuckled to myself at the inaccuracy of the report — bluebird weather it wasn't going to be.

When I walked in I could see that Joe was a bit antsy; looking like he was on his 14th cup of coffee. Eric looked a bit too awake for a seven-year-old at that time of the morning, too.

The day was starting to break as we drove north to the pond. The skies were heavily overcast, yet high, and a brisk enough wind was pushing out of the southeast to make the ducks hang (Continued on page 40)

holding the peaks

Size limit on bass maybe key to sustaining good lake angling

OVER THE YEARS, outdoor writers, field testers for tackle companies and a number of other fishing pros appeared as fountainheads of authoritative angling advice by spouting truisms like "fish the hot lakes, the new reservoirs that are just reaching their peak."

And for a long time this was good advice. But, these sages may soon have to come up with a new "pat" answer, because the fishing "peak" they refer to could become a thing of the past in lakes which support a basic bass and bluegill fishery.

Their advice was based on a long-accepted premise that all new impoundments reach a peak in sport fishing, a sort of golden age, a few years after initial stocking. After that, a nosedive into irretrievable mediocrity seemed to be the lake's inevitible fate.

However, fisheries biologists now believe that such drastic fluctuations are not inevitable, and that new management techniques can keep certain impoundments producing well long after they would have been written off under former management procedures.

The first of these management practices is already with Nebraska anglers in the form of a 12-inch minimum size limit on largemouth, smallmouth and spotted bass, effective January 1, 1974. It applies everywhere in Nebraska except the Missouri River. The new size limit is expected to provide the most benefit in heavily fished waters like eastern recreation areas, the Interstate 80 lakes and the impound ments being built in the Papio Watershed, although other waters including private ponds should also benefit.

Basic to warmwater fisheries management in many Nebraska lakes is the predator-prey relationship between largemouth bass and bluegill. Other species such as the northern pike and walleye are considered temporary bonuses, while crappie, bull heads and some other species are often a threat to good angling.

Years of research and experience in a number of states have demonstrated that bass do not fare well in the long run without a good bluegill population to feed on, and that bluegill only do well when there is a good bass population to constantly thin their ranks. Thus, the average size of bluegill in a lake is a good indication of its overall status, with relatively large individual bluegill pointing to a healthy balance of both species.

When a new impoundment is first stocked, usually in the fall, the bass have no competitors for food, and no larger fish to prey upon them. They grow remarkably well, averaging 8 inches at the end of the first year, 12 inches the second year, and 15 the third year in Nebraska waters. Later generations of bass in the lake will not be able to match this growth rate because of the head start the original fish had.

While the bass are packing on the pounds, the bluegill stocked with them are also growing well. There is little competition for the food they eat, especially with bass thinning their numbers. During their next summer, bluegill are large enough to reproduce, yielding a good crop of forage for the bass.

These first years of growth of both bass and bluegill represent the uphill portion of the reservoir's fishing curve, and fisheries biologists observe this phenomenon with delight. But, to be called a "peak", a lake's angling curve must also have a downhill side.

Most noticeable symptom of this downhill trend is overpopulation and stunting of the bluegill. In other states, several factors can cause this, but in Nebraska, the major cause is excessive bass harvest.

On a heavily fished lake, most of the aggressive largemouths can be removed in a fraction of one fishing season, leaving the bluegill population largely unchecked. More heavy angling the second and third years adds to the overharvest of bass and compounds the stunted bluegill problem. When the bluegill get out of hand, they attack bass spawn and fry, making it impossible for the predators to replenish themselves and restore the lake's balance. In the end, the only solution appears to be poisoning all the fish in the lake and starting over.

If the harvest of bass were limited to a reasonable level, where the surplus could be taken without losing control of the bluegill population, the lake could remain productive for years. Instead of a sharp nose dive, the lake's fishing would go down only slightly from its highest point, then level off.

In Nebraska, angling overharvest has been most apparent at the heavily used sandpit lakes such as those at Louisville and Fremont state recreation areas. There, overfishing has meant that only about three years of every six would provide any fishing at all, and only one of these seasons would offer quality angling. During the other three years of the cycle, the lake would be closed for renovation and to allow newly stocked fish to grow. About the same thing might have been the fate of the new Papio Water shed lakes now being built in the populous Omaha area.

The newly enacted size limit will obviously result in fewer bass being taken, but in terms of total weight of bass, the harvest should actually increase. Taking only fish 12 inches or over allows them to reach a heavier weight and provides sufficient predator control over bluegill.

But why a 12-inch minimum? Why not 10 inches or 8 inches or 15 inches?

Fisheries biologists answer the question by saying that this size will allow a maximum harvest of bass while providing bluegill control, and will also allow for maximum usage of the lake's fish-raising potential. They calculate this in a rather interesting fashion on the basis of past experience and research dealing with unfished lakes.

Consider the life history of a group of fish the biologists call a "year-class," that is, all the fish of one species hatched in one particular year. The growth rate of individual fish represents several thousand percent gain in weight the first year, going from nearly microscopic right out of the egg, to four or five inches in a matter of weeks. Mortality is also fantastic, with the several thousand eggs laid by one bass being reduced to perhaps a few dozen finger lings in short order.

Forgetting the growth and mortality of individual fish, a look at the total effect on that year class shows a remarkable growth rate. After the first year, the growth rate of individuals drops to perhaps one or two hundred percent, and continues to drop even more each successive year. Mortality, however, levels off to a constant rate of about 40 percent.

Thus, the total weight of the year class continues to rise as long as the growth of the surviving fish keeps up with or surpasses the weight of the 40 percent which die. However, at a (Continued on page 46)

32 NEBRASKAland 33

fishing bad? go hunting!

FISHING ANY of Nebraska's big reservoirs is often a shaky proposition. Many a three-or four-day trip has turned into wasted effort when bigthunderheads move in bringing rain —buckets of rain —enough rain to send the most avid fisherman heading for cover.

But the worst thing about the weather in Nebraska and its adverse affect on fishing is the wind. The kind of steady, hair-twisting, skin-burning wind that makes your heart drop a couple of hours after sunup, shattering dreams of a glorious day on the lake. Dreams based on the vision of a mirror surface and the gentle rustle of cottonwoods along shore early in the morning of a late September day.

Lake McConaughy's wind has probably caused more fishing gear to be put away, never—at least anglers say it when they put it away-to be picked up again. I imagine most of the gear has been stored in the eastern part of the state, because that's the maddening thing about Big Mac the round trip runs about 600 miles from Lincoln. Six hundred miles of hope and a week of fitful sleep dreaming of lunkers and stringers of fish, all shattered by a low pressure system.

I've been to Lake McConaughy several times in recent years but never for more than three days including the drive to and from Lincoln. In all those trips the weather has never been good. Always, as if to say "don't come back", the weather has ruined the trip. This time I hoped the high pressure area the weatherman predicted was, in fact, there.

Dan Wright and Paul McLlnay, both of Falls City, Ray Gans of Lincoln and myself headed for McConaughy, all thinking the same thing-this time the weather would be good. Of the group, only Ray has been successful on the big lake. He is a story in his own right, and he'll also tell you a few. Fishermen's tales all, but with one slight difference-they're true and he has pictures to prove it. Pictures of stringers full of white bass, walleye, and trout. He and his wife have probably caught as many Master Angler award fish as anyone, save a few local residents of the lake who can pick their days.

Dan and Paul are among the most avid walleye fishermen in the state. They both have caught more than their share, and among them have some of the biggest I've heard about. One trip this year to Brady totaled 18 big ones-the smallest 6 pounds and the largest over 13. But they, too, have had their troubles with the big lake.

We left Lincoln late Friday and arrived at the campsite at Martin Bay on the north shore about 3 a.m. Ray rattled our cages about five, but by the time we launched our two boats and drove the vehicles around to Arthur Bay it was after six and the steel dawn had turned to pink. Only a few light clouds showed in the east, and the lake was indeed calm. My heart jumped for here it was; a perfect day for jigging with virtually no wind-just enough for the slow drift necessary to keep lures moving along the bottom.

Dan and Paul headed for deep water where they had enjoyed limited success on walleye two years before. Ray and I headed for Thies Bay to try our luck with the newest of the lake's game fish, striped bass.

When we got to the point offshore where some people had been picking up stripers, several boats were already there. Ray chose a spot where he had caught some small stripers and we began our drift over about 40 feet of water. Not being too familiar with the art of jigging, Ray explained

"You release the slab and let it settle on the bottom. Take up the slack in your line and with a quick jerk of the pole, raise the lure off the bottom and let it settle back."

He told me the lure settles back in an erratic manner and is supposed to look like a wounded shad. "The way I figure it, the white bass hit the shad, and cripples go to the bottom where the stripers and walleye have easy pickings".

Ray chose a white slab and I hooked up one with a basic white color but with a scaled effect. Having observed crippled minnows in the water, I decided to try short, rapid "jigs" because such minnows have an erratic behavior, and often their frantic thrashing has brought predators to end their misery.

We hadn't been at it ten minutes when I felt a tap, but my startled attempt at setting the hook failed. Almost before

In the fall, both of the state's favorite outdoor sports can be combined in one trip and if one doesn't work out, try the other 34 NEBRASKAland JANUARY 1974 35

the lure had a chance to settle back on the bottom, I felt a tug on my line. Having learned my lesson, I tried to jerk the fish's head off. This one was hooked, and from the looks of the worm rod it was a big one, because it takes a good-sized fish to bend one.

Almost as quick as it happened, the line went slack and I knew the fish had thrown the hook. I also knew there hadn't been any slack in the line so I brought the lure up to check the sharpness of the hooks. The new lure appeared fine, and I watched it settle back into the deep water in a flighty, herky-jerky motion.

It no sooner hit bottom than I felt the now familiar tug of a big one. This time the hook was set fast and I trembled with anticipation.

"He's fighting like a striper," Ray shouted, reaching for a float to mark the spot.

The big fish doubled the rod over and you could almost hear that 20-pound-test line sing with tension. He made one run and I stopped him, taking up line as the fight continued. Another run and again I turned him. He settled down to a steady pull on the line and ceased his awesome runs, similar to the ones a big carp will make. I continued to bring in line and peered intently into the water, watching for that first glance of the big silver sides of what I hoped was a striper and not the ugly yellow sides of a foul-hooked carp.

Suddenly the fish made another run, straight under the boat, and just as I reached to release the drag I felt the sudden, sickening jerk as the line parted.

"He's gone," I said.

"How's your drag?"

"I don't know if that was the problem or if he cut the line on the bottom of the boat or on the motor," I lamented. If it was the drag, I had learned a valuable lesson —always have the drag set just tight enough to allow you to pull out some line. I knew that, but often it takes an experience like this to refresh your memory. Setting the drag now is always the last thing I do before making the day's first cast.

"They must have been going after color rather than just hitting anything," Ray suggested. "What color did you have on?"

"It doesn't make any difference because I don't have any more of them," I said.

"Take a look in there," he said as he slid a box toward me. There were enough slabs and Lujohns in that box to start a tackle shop. That's one thing about Ray; he has more equipment than 10 normal people and he never forgets which lures produced the best success and he's been fish ing for more than 40 years.

I picked out a couple that came close to the one I had lost, and we hooked up and started for the marker Ray had thrown out. No sooner had we run out line than I again felt the tug of a good fish.

"This one doesn't appear to be as large as the last one, and the way it's fighting I think it's a walleye," I shouted.

Walleye don't have the fast, furious fight of bass or some others. They will hit a lure with as vicious a strike as any fish, but then they just lay in the water and tug on the line. You could tell this fish had some authority, and after several minutes of give and take I saw him break surface a few feet from the boat and turn over on his side-the big, yellow side of a 6-pound carp.

"How many disappointments are you going to have today?" Ray asked. I don't know if my face registered the same as his, but I know the cussing under my breath relieved the impulse to throw the pole in the water.

We hit the lake hard the rest of the morning, but our only success was one small striper that Ray held in the palm of his hand, and one walleye about the same size.

Dan and Paul came steaming up alongside and announced that Dan had landed a 3-pound walleye, amazingly hooked in almost 70 feet of water. Some of the old pros from around the lake later told us they had been taking fish in depths approaching 90 feet.

We spent the remainder of the day working over the lake with only three more carp caught, all of them inadvertently snagged. Some people keep carp, and I have eaten them at fish fries, but they were still a disappointment.

Almost as quick as losing a fish, the wind came up. The big lake had been smooth and calm, but steadily the wind picked up intensity until we were surrounded by whitecaps and heavy swells. Finally we decided discretion was better than swimming and headed toward shore.

One keeper fish in about 48 man-hours of fishing is nothing to write home about, but our spirits weren't dampened and the thought of another day filled us with anticipation.

But, morning dawned miserable. The wind was blowing a gale from the southeast, slamming ever-growing swells onto the north shore right where we wanted to fish. Adding to the trouble were a heavy fog that cut visibility to less than 1/8th mile and a heavy mist that forced us into rain gear.

We hadn't expected perfect weather, and any avid fisherman will do his thing in almost any weather except for that old nemesis, the wind. We stayed out for a couple of hours, but finally, after not even a carp would hit, we decided to load up the boats and go to the south shore, where the bluffs sheltered the shoreline.

Paul and I drove the vehicles around to the ramp at Martin Bay to meet Ray and Dan who brought the boats in. But there to meet us was the owner of Sportsman's Complex, who had received a call at 2:30 a.m. asking him to find Dan because his wife was going to the hospital.

Upon learning that he was the father of a baby boy, Dan exclaimed with a grin, "Well, I suppose I'll have to go home."

After bidding Dan and Paul good-bye, Ray and I loafed the rest of the day waiting for the wind to go down. But nature wasn't on our side, and ominous clouds began building in the southwest. Soon lightning pierced the sky and one of the worst electrical storms I have ever seen tore up the pitch-black night.

Driving across Kingsley Dam, I saw at least four bolts strike the lake, and we wondered how many fish met their maker. We pitched camp knowing the fishing would be next to impossible if this front was like most others. The majority of the time after a low pressure area passes through, the wind shifts to the north or northwest and cold Arctic air flows into the state. However, this trip we had planned to go grouse hunting the first day that the weather wouldn't allow fishing.

Monday dawned less foggy than the previous day, but low clouds and mist didn't offer any bright prospects for grouse hunting. We met Ken Kolsrud of Ogallala early and loaded up his four-wheel-drive pickup for a jaunt into the Sand Hills north of the lake.

Ken is an avid outdoorsman and appears to know the rugged, expansive country very well. He scouts the country all year and knows where the big herds of antelope and deer, as well as grouse, can be found.

We drove off on a public road just north of the lake through verdant pasture land. The rolling hills were shrouded in mist, giving them an eerie quality. You could almost hear the sounds of thundering herds of bison from years gone by pierced by the warwhoop of a band of Sioux or Cheyenne on the hunt. (Continued on page 44)

bobbing for Life

IT TOOK 40 years of duck hunting on the North Platte River to teach me the real meaning of the old saying "familiarity breeds contempt."

It was a chilly November afternoon. I had invited my brother-in-law, Don Howard of Fort Collins, Colorado, to join me for a couple of days at our duck lease between Bayard and Bridgeport. We have one of the nicest spreads on the river —two miles of good water be tween Belmont Dam and the Camp Clarke Ranch, water that remains open year-round and a nicer-than-average cabin.

I was hunting from a blind on the river bank about midway in our lease. My brother-in-law had gone on to the east end to prowl the tow heads, hoping to find some pheasants or perhaps to get some jump shooting on mallards clustered close to the banks. A cold wind was blowing, but it was a clear day and the water was blue and inviting. From where I sat, you'd never have known there was any pollution in the world. Contrails from a dozen jet planes had formed in the sky overhead in the short time I had been in the blind, and that was about as close as I had come to anything flying.

About an hour before sundown, a lone greenhead came sailing along and responded to my call. I dropped him about halfway between the bank and a large island 40 yards away. It looked like an easy retrieve as I eased myself down the slope of the river bank and began my venture into the swift water. I had been there a hundred times before in water that ranged from knee deep to my waist. It was no problem, or so I thought, because I had retrieved many downed ducks at this location and knew every square foot of the river bottom.

JANUARY 1974That's where I made my mistake.

As every veteran river hunter knows — or should know —the shifting sand can create holes in the riverbed over night. One day you have solid footing at a shallow depth; tomorrow you can go out of sight if you step into a hole. I had just reached the center of the channel and was reaching for my green head when I took a step and there was no bottom. Before I could get straight ened out I was in water over my head and bobbing around like a cork, my waders full to the top, my eye glasses floating down the channel and my heart beating like a trip-hammer.

They say your entire life flashes be fore you in an instant when you think you are going to die. Mine didn't. All I could think of was how Don would react when he came back to the cabin and I was missing. The river is swift as it rolls out of Wyoming into western Nebraska and on for many miles into Lake McConaughy. I had visions of my brother-in-law searching frantically for me, then sounding the alarm in Bayard and Bridgeport. I also had visions of coming up from under the ice some where in Lake McConaughy the follow ing spring.

All this time —probably not more than a few seconds —I was fighting to get my feet down so I could find bottom. I flailed with my arms as I bobbed and floated, finding nothing but cold water. By some super-human effort, which one would not expect from a man in his 60s, I finally got my feet down at about the same time I came into a shallower area. As I planted my feet firmly into the hard river bottom, I straightened up and cautioned myself not to hurry. First, I had to get my breath and regain some strength, most of which had been drained from me in a surprisingly short time. When I thought I was ready to move, I scanned the bank to see which way to head. I spotted an old dead tree on shore, its wind-beaten branches hanging almost into the water. I told myself that if I could reach that tree, I could drag my self up on the bank. It seemed like an hour, but it probably was no more than four or five minutes before I reached the tree and grasped its bare branches. Then, after resting another minute or two, I pulled myself up on the ground and spread out flat, letting the water drain out of my waders.

My gun, shells, other equipment and decoys were all at the blind, but I wasn't interested in salvaging anything but my life. I began the long walk back to the cabin, actually not much more than half a mile, and when I got there I stripped off the cold, wet clothes and found an old pair of coveralls that looked better than a $300 suit. Once I got dried off, warmed and at least partially clothed, I did what any red blooded duck hunter would do —I poured myself a water glass half full of good old Kentucky bourbon and swallowed it in one gulp. I am not a believer in spirits as a cure for anything physical or emotional but I must say that this seemed like a moment when even a lifelong teetotaler would have welcomed a good stiff drink.

As I look back on it, I realize I broke a cardinal rule of river hunting —never go out in deep water when you are alone. There is too much danger. You could have a fainting spell, a heart attack or, as I did, you could forget for a foolish moment that the river is a good friend when everything is right and a treacherous enemy when something goes wrong. I don't think I will make the same mistake again. The good Lord gave me one chance; I don't want to crowd my luck.

STRAW-BALE PHILOSOPHY

(Continued from page 30)over the decoys. That meant the ducks would be coming out of the northwest and we would lose sight of them until they were right over the decoys.

Joe was still rearranging the decoys when a drake redhead drifted down on cupped wings. His webs barely hit water before he changed his mind and pumped out considerably faster than he had come in. He needn't have worried though. Shooting him would have meant a full limit and it was a bit early in the day for that.

Joe's blind was a well-designed and substantially built portable he'd horse-traded, or stolen, from a friend —which was the case wasn't exactly clear. Joe had anchored it with steel posts on the west side of the smaller of two farm ponds in the middle of a corn and wheat section. About four miles to the north was one of the federally owned rainwater basins.

The location was the real beauty of Joe's setup. It was close enough to several of the public marshes to have lots of ducks around, but tucked away in the middle of the section where there weren't other hunters. As hunters on the basins start stirring up the ducks, they look for more out-of-the-way waters, like those right in front of us.

Shooting from the basins had been sporadic so far, though, not nearly as regular as last year when we opened the season on the same pond. There wasn't much to do but wait for the duck hunters up there to start combing the rushes and run the ducks out, so we made things homey in the blind, tapped a thermos of coffee and began expounding at length on the merits of duck hunting to the inner man.

We were just getting into the core of the subject, about to the point of deciding, as we always did, that what today's society needed was to renew its contact with the natural world, when half a dozen green winged teal zipped overhead. Joe rolled off a couple of the sweetest chuckles ever to pass by a reed and the flock swung to the west, behind the blind. We made ready for them to come scooting in low from the northwest. Just when they were leaning back into the breeze we dropped the shooting board.

Three dropped on the water and Scout, Joe's 65-pound pup, made ready for his formal introduction to real flesh-and-feather birds. One teal, a nicely colored drake, had come down with a broken wing and skittered out into the middle of the pond. The other two had dropped close to the east shore, and with a bit of coaxing Joe enticed Scout to bring them to hand.

Scout developed an instant taste for feathers and plunged back into the pond after the third teal. If we had known that 40 this teal had a substantial dose of diver in his lineage, we probably would have finished him on the water. I don't remember exactly how the old adage goes about hindsight and foresight, but I think it has some thing to do with knowing better after than before. Scout performed like he really knew what he was doing, but the teal like it knew a bit more. Just when the dog closed in, the bird would pop up behind him, to the side of him and beyond him. Never, though, was the distance enough to permit a killing shot without endangering the dog. Finally, after several limits of ducks had passed over our two-man-one-dog-carnival, Scout pinned the drake in the grass and we crawled back into the blind.

We were seeing some big ducks over head-looked a lot like pintails, maybe some gadwall or baldpate. It didn't make a whole lot of difference though, since they were flittering in and out of the clouds. Last year, when we opened the season in the rainwater basin, we'd taken only teal, about half each of the two common species, and one mallard. According to Joe, the preponderance of bigger ducks for the opener would be gadwall, baldpate and pintails. The pintails, he said, would move out about three seconds after the shooting started. There were a few mallards about, but the big push of that species was still several weeks off. A few divers, mostly redheads, were in too, but not many.

A lone bluewing came gliding in from the north without so much as a precautionary circle and overshot the decoys as if it might drift down to the south end of the pond. Joe's first shot was late by a foot, the second knocked the teal cleanly. Scout, performing like a veteran now, retrieved it without fanfare. He was even starting to show signs of preferring real ducks over the inflatable decoy.

Joe and I nestled back down on the sagging ends of the bale, poured a new round of coffee and resumed our quasi-philosophical discussion of duck hunting. I couldn't help but notice Eric examining the latest addition to the bag. Feather lice were carefully picked off and examined, mottling on the bill was noted and commented on, and each bird was identified as to sex and age.

Eric was a good measure beyond the stage of identifying species-a fact that made me a bit uncomfortable to say the least. He checked the completeness of the speculum to identify the sex and then examined the degree of wear on the tail feathers to de termine if the bird was a young-of-the-year or an adult. An unusual kid to say the least. But back to my story.

A pair of teal barreling out of the north craned their necks in response to Joe's highball call, and drifted down to his chuckle. Just about in front of the blind we stood up and touched off, Joe on the right bird, I on the left. Both fell neatly among the decoys. It was a fine display of shooting, no doubt about that. Joe and I were right in there with the best of 'em. Eight shots and we had six birds, all of them zippy little teal. The dog even rose to the standards of his hunting mates and retrieved the two bluewings like a field champion.

Joe was out of the blind, as poised as English gentry, waiting for the last bird to be delivered to hand and I in the blind expounding at length on the quality of our shooting, when a lone bluewing came gliding into the decoys, oblivious to Joe and the lab. Duck soup, I believe, is the appropriate phrase. I sized up the situation carefully. Joe was out of the way to the right and the dog was nearly to him; the bird was coming in from the left. As calculating as Jimmy the Greek, I shouldered my arm, figured the bird's speed, the wind direction and speed, and computed the trajectory. At the appropriate moment I ruled the bluewing as part of my day's bag.

The teal was a bit startled at the shot; I was only minorly annoyed that it didn't fall. The bird quartered back to the northeast, hanging in mid-air while negotiating his turn. Still calm, I considered letting one go as a goodwill gesture, then decided that Joe wouldn't believe that and lowered the bead to just above the teal's head and touched off. Calmly, I opened the door to the blind and strolled over to retrieve my quarry. It was then, as I almost bent to pick up my duck, that I noticed he was still retreating toward the horizon. I fell back into the blind like a wounded eagle. Joe was admirably kind, saying something about vaguely remembering another hunter he saw miss an easier shot once.

A marsh hawk glided over the blind and started hunting the east shore of the pond. We'd watched her for awhile, then Joe turned to Eric, who had been studying the bird of prey without word or expression. "You see son," he began, "if we had shot that hawk we wouldn't have had anything to watch for the last 15 minutes."

Eric sort of squ inted up at Joe and without any pause to mull over his father's words, replied, "We could have hung him with the ducks and looked at him all afternoon." Such are the trials of the teacher.