NEBRASKAland

May 1973 50 cents 1CD 08615 Sand Hills Special: Prairie Grouse Geology Irrigation 1973 EQ Index

NEBRASKAland

VOL. 51 / NO. 4/ APRIL 1973 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Fifty cents per copy. Subscription rates $3 for one year, $6 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. commission Chairman: William G. Lindeken, Chadron Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Vice Chairman: Gerald R. Campbell, Ravenna South-central District, (308) 452-3800 Second Vice Chairman: James W. McIMair, Imperial Southwest District, (308) 822-4425 Jack D. Obbink, Lincoln Southeast District, (402) 488-3862 Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 Kenneth W. Zimmerman, Loup City North-central District, (308) 745-1694 Don O. Bridge, Norfolk Northeast District, (402) 371-1473 Director: Willard R. Barbee Assistant Director: William J. Bailey, Jr. Assistant Director: Richard J. Spady staff Editor: Irvin J. Kroeker Editorial Assistants: Ken Bouc, Jon Farrar Lowell Johnson, Faye Musil Photography: Greg Beaumont, Bob Grier Layout Design: Michele Angle Illustration: C. G. Pritchard Advertising: Cliff Griffin Circulation: Juanita Stefkovich Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1973. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Came and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska Travel articles financially supported by Department of Economic Development Stan Matzke, Director John Rosenow, Tourism and Travel Director Contents FEATURES AVOCET SPRING 14 COWBOY COUNTRY 24 PRAIRIE GROUSE 26 Sharptail 28 Prairie Chicken. 36 Management 39 Hunting 41 1973 ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY INDEX 43 THE DUNES 51 SAND HILLS WATER 54 DEPARTMENTS SPEAK UP FOR THE RECORD 10 WHAT TO DO 59 TRADING POST 65 OUTDOOR ELSEWHERE 66 COVER: American avocet over nest; photo by Greg Beaumont. Documenting the six-week period of nest-building and incubation required steady observation and endless hours of confinement to a blind, an experience Photographer Beaumont describes as having been "at once exhausting and exhilarating." His photo essay "Avocet Spring" begins on page 14. MAY 1973

Speak Up

The Giveaway GameSir / I read with interest your editorial with which I heartily agree. I am referred to as elderly, age 69. For some time, I have been of a mind to express my views on free hunting and fishing privileges extended to certain groups, such as myself. I am not in favor of passing on the cost of the privileges I enjoy so much to another group, nor am I in favor of seeing these services or privileges curtailed or discontinued because of lack of funds that would be a certainty if I and my group were to quit sending your office our meager hunting and fishing permit fees.

Because many of us elderly have more time to enjoy fishing and hunting, we get more benefit than the rest, and certainly I feel thankful for the fish, game, facilities and privileges that are available because of permit fees. A resident permit, when figured over a period of one year, costs about three cents per day, including federal and state bird stamps. It is the cheapest and best and healthiest pastime we have. I feel so strongly about this that I would buy a permit even if a free one was available.

In my lifetime, I have seen hunting and fishing access areas diminish to almost zero and return to special-use areas. Hunter and fisherman and farmer cooperatives are so abundant that few if any of us can find time to take advantage of all of them. The pheasant has come from zero to abundance, geese from the danger point to literally thousands, and mallards from danger to flocks that all but blacken the sky in December over corn fields just out of Omaha. Deer that we had to go to Wyoming or Colorado for now are a menace at our Omaha Airport and have been seen from our backyards in Omaha. Need I say more?

A. E. Harpster Omaha, NebraskaSir / As a World War II veteran over 65 years of age, I had planned to obtain a free hunting and fishing license until I read your article. You convinced me that I should pay the regular fee, which I have done. I agree with your statement that it is unfair to shift the financial support of the Game and Parks Commission to other sportsmen who may be subjected to increased fees to compensate for funds lost by issuing free permits to special groups.

I do not believe there is such a great majority of disabled veterans and/or elderly sportsmen unable to pay their own way to justify free permits, or even permits at a reduced rate.

Frederick W. Bentley Lincoln, NebraskaSir / I would like to be counted as one who thinks the free permits are so much hogwash. I have been able to purchase hunting and fishing permits, along with upland game stamps and federal duck stamps since I was 16, all with money I earned through my own efforts. When the day comes that I have to depend on the state's general fund for my permit, I'll sell my guns and give my flyrod away.

I have every respect for old people. My grandfather lived to be 101. With luck, I'll be hunting and fishing up to my dying day, but I'll pay for it myself, thank you.

Carlee P. Mathis O'Neill, NebraskaSir / I am opposed to free licenses for any one under any circumstances. I know it takes a lot of money to hire wardens, and we need more money for research. We have made progress under the present program. Making radical changes might cause us to lose all we have gained.

Charles M. Adcock Kearney, NebraskaSir / During the past decade, and more, we have seen the quality of hunting and fishing increase to a marked degree in our state. The credit must go to competent and long range planning by the Game and Parks Commission, and the willingness of sports men to pay the price.

If we were to go to a program of state funding, the pressure of politics would make a shambles of all that has been accomplished during the past 20 years. I would suggest a program of education through your fine magazine, and speaking engagements by members of the commission and wardens to slow down and stop this growing movement, and to try to get these free privilege laws repealed.

Ed Nickel Palmer, NebraskaSir / I don't believe that a few free permits given to aged people and veterans would make much of a difference in your budget. For the most part, these people don't hunt. Some fish, but then just from the banks of ponds. As for lost funds, most of these people wouldn't have bought a permit any way.

Clarence Whitmer Beatrice, NebraskaSir / I think we should be allotted money from the general fund to make up for lost revenue from free hunting and fishing permits.

Daniel E. Anthony Wisner, Nebraska HostessSir / I have subscribed to NEBRASKAland since 1963. In the many years of enjoyment from each issue, I always thought the hostess of the month was one of the main features of the magazine. Why has this feature disappeared? Many people in this area feel the magazine is not the same without the hostess of the month.

Dave Dent Otradovsky Program Director, Radio KVSH Valentine, Nebraska Future Of FarmingSir / Robert Steffens's article did well in presenting the problem and challenging the individual to change, but legislation is the key to change. I'm not an ecology freak, nor have I ever been instrumental in the passage of legislation, but I am sincerely interested.

Bill Heine Seward, NebraskaSir / It seems to me that this article and the concept it conveys must not go unanswered. I am sure others are more capable of this than I, but I will at least try to express my thoughts on this subject and my objections to the thrust of Mr. Steffen's message.

I believe that his theory of a return to organic farming is no more than an impossible dream. Anything that is harvested from the soil and removed from the farm depletes the soil. In time, these withdrawals must be replaced. Of course it is accelerated under modern farming techniques due to much higher production, but it is not idle talk to say that if the population of the world is to be fed, it cannot be done with the production expected under crop rotation, crop diversity, low energy, farming-is-a-way-of life theory espoused by Mr. Steffen.

NEBRASKAlandNaturally we must use the techniques of modern agriculture wisely, just like almost everything else in life, but I am firmly convinced that, where properly used, the commercial chemical fertilizers, herbicides and insecticides are a real blessing not only to agriculture, but to the entire population. I have lived nearly all my life on one section of land. I can well remember under some thing similar to Mr. Steffen's organic farm ing system yields of 40 or 50 bushels of corn and 25 bushels of wheat some years, and complete failures other years. These crops produced very little organic matter and the soil washed away in rains and blew away in the wind. We had insect problems, severe at times, and we always had weeds. Because of uncertain production, livestock numbers were low and fluctuated with the seasons.

Now we irrigate, fertilize, use herbicides and insecticides according to the best recommendations. Our yields of corn approach 1 50 bushels year after year and that is the only crop we raise. The organic matter in our soil is much higher than it ever was before. Erosion by water is much reduced, and by wind is almost nil. I have no counts of microbial activity before or now, but with the higher organic matter content and the good decay of it, I feel certain that the soil biology is much improved. We have continued to have our well water tested and the results are zero ppm nitrogen. I agree that it is desirable to feed back as much of the production as possible onto the farm, and we are attempting to do this, but more from an economic point of view than from an ecological one.

It seems to me that your magazine would serve a much more useful purpose if it would point out specific problems that face modern society and concentrate on finding answers, rather than publishing stories which make sweeping condemnations of what is being done and suggest that the only answer is to return to former times, which I feel is impossible. You have published articles finding fault with almost any suggestion to more fully utilize our water resources.

Robert L Johnson Hastings, Nebraska More For Dr. SpanglerSir / Dr. J. G. Spangler's letter in the January issue of NEBRASKAland practically demands a rebuttal. I'm going to do it by asking Dr. Spangler some questions, and then let his conscience guide him.

Do you eat meat of any kind? Have you ever visited some of the commercial slaughterhouses where little lambs, bleating to tear your heart out, are often callously butchered? Isn't it wonderful to be able to drive in solid comfort to the nearest super market for some choice lamb chops? Do you really know why some areas have an under-population of wild game, and why it would not be feasible to try restocking these areas? Could it have some

NEBRASKAland

DATS

JUNE 17-24

NORTH PLATTE

For Family Entertainment:

Buffalo Bill Rodeo,

Believed to be world's

first and oldest rodeo

started by Buffalo Bill

Cody. Miss Buffalo

Bill Rodeo Queen

crowned.

PARADES!

NEBRASKAland Pa-

rade. Floats, bands,

marching units, out

standing riding

groups, Antique and

Classic Car Parade,

plus the Best Dressed

Western Kids Parade.

ANT!

Miss NEBRASKAland

Pageant. 2 days of

all new musical pag

eantry climaxing with

the crowning of Miss

NEBRASKAland, 1973.

AWARDS!

Buffalo Bill Award.

Presented in person

to a famous TV or

w movie star for wout

J standing contributions

to quality entertain-

ment in the Cody

tradition."

CARNIVAL!

One of the largest

carnivals in out-state

NEBRASKAlandl

Fun - Frolic - Songs

Dancing Girls - An

era of the Old West

comes to life in an

all-new Western Mu

sical Show.

OTHER EVENTS

Art Shows - Square

Dances - Shoot Outs

and some new, and

added attractions.

Tickets and information

available from

NEBRASKAland Days, Inc.

100 E. 5th Ph. (308) 532-7939

North Platte, Nebraska 69101

NEBRASKAland

DATS

JUNE 17-24

NORTH PLATTE

For Family Entertainment:

Buffalo Bill Rodeo,

Believed to be world's

first and oldest rodeo

started by Buffalo Bill

Cody. Miss Buffalo

Bill Rodeo Queen

crowned.

PARADES!

NEBRASKAland Pa-

rade. Floats, bands,

marching units, out

standing riding

groups, Antique and

Classic Car Parade,

plus the Best Dressed

Western Kids Parade.

ANT!

Miss NEBRASKAland

Pageant. 2 days of

all new musical pag

eantry climaxing with

the crowning of Miss

NEBRASKAland, 1973.

AWARDS!

Buffalo Bill Award.

Presented in person

to a famous TV or

w movie star for wout

J standing contributions

to quality entertain-

ment in the Cody

tradition."

CARNIVAL!

One of the largest

carnivals in out-state

NEBRASKAlandl

Fun - Frolic - Songs

Dancing Girls - An

era of the Old West

comes to life in an

all-new Western Mu

sical Show.

OTHER EVENTS

Art Shows - Square

Dances - Shoot Outs

and some new, and

added attractions.

Tickets and information

available from

NEBRASKAland Days, Inc.

100 E. 5th Ph. (308) 532-7939

North Platte, Nebraska 69101

thing to do with loss of proper habitat, like poor farm practices and bulldozing for urban sprawl and superhighways?

Which is worse, outright killing of surplus game or allowing it to slowly starve to death, homeless and lost?

Where and how have you hunted in the past? Have you ever gone into the wilderness where your very survival might hinge on your ability to cope with some of the most arduous tasks demanded of man?

How much closer can we come to a so called "superior species" considering what is now occurring in Southeast Asia, where thousands of human beings are being slaughtered in the name of I don't know what?

Where do you propose that the "two of a kind" wild game be raised for the man who wishes to eat wild meat? In his back yard? Where would you release the other, now nearly domesticated animal, if it were possible to raise it at all in captivity?

Do you drive an automobile? Did you know that in some areas more game is killed by cars than by hunters? And that the occupants of the autos are also often injured, sometimes killed? Did you know that the automobile does not discriminate against killing songbirds, too?

In closing, I do not mean to be disrespectful of Dr. Spangler. If, on moral grounds, he chooses not to hunt, that is his privilege. On the other hand, his letter seemed all out of proportion to known facts, and appeared to be an unjust vilification of the true sportsman who finds hunting a vigorous, demanding and rewarding sport.

If he hasn't already done so, I'd like to suggest that Dr. Spangler read the article by William G. Lindeken, "Curbing The Vandal," on page 7 of the same issue. Mr. Lindeken tells of the kind of hunters we can well do without.

George L. Marzeck West Burlington, IowaSir / We people here in Pennsylvania are glad that Dr. Spangler expressed his views on hunting. We have barred the roads and are keeping watch for him at the border.

Out here we people are hunted by deer. The first day of the season a deer hooked a woman on her fanny and tossed her into a ditch, and she wasn't even hunting.

In my state, in 1972, 26,435 deer were killed by cars; hunters took over 107,000. If we take Dr. Spangler's suggestion to raise two and eat one, we add 107,000 to the deer population to die of starvation, and if we could raise them, they would not be wild.

Come on, Doc, and say you are just kidding. Your letter is the funniest I have read since they printed Captain Billy's Whiz Bang.

Peter J. Conroy Greensburg, PennsylvaniaSir / Would you, Dr. Spangler, like to see hundreds of thousands of pheasants killed by starvation and winter kill? I imagine it would give you "a sick feeling in the pit of your stomach." The pheasant harvest in Iowa for the 1971 season was 1,700,000. If these birds had not been harvested, the natural mortality rate would have been high.

Gary Gaiser Creston, IowaSir / You [Dr. Spangler] have fallen hook, line and sinker for one of our nation's latest fads. As usual, this fad was started by a few individuals who know only enough about the subject to sound educated. I have seen very few cases of wanton slaughter, and those who commit these acts cannot possibly be classified as hunters.

As for the possibility of encountering a superior species, I only hope that species will have as much concern for our welfare as the true hunters and sportsmen of this world have for the welfare of wildlife.

Richard L. Stephens Waco, Nebraska Plum CreekSir / Thanks for your fine article on the Plum Creek Circle Tour. One spot you missed is the historical Evergreen Cemetery. The cemetery will be 100 years old this year. I am trying to catalog the original lot owners and to bring the Lexington records up to date on burials. The records I have are first dated August 8, 1873. Perhaps you might like to do a story on it some day.

Mrs. N. E. Hollingsworth Lexington, Nebraska Pritchard's PaintingsSir / Your December issue contained some great copies of C. G. (Bud) Pritchard's paintings. In the past, you have reprinted pictures such as these for framing. Will you be doing that again? If so, I would like a set of them.

W. R. Petenman Dallas, Texas Gems In The RoughSir / The article "Gems In the Rough" was truly a gem. Old houses are topical sub jects for those with divergent interests.

Lester Goiter Wilcox, NebraskaSir / Warren Spencer's article was one of the most interesting I have read in many a year. Being a native of Nebraska, I enjoy every trip back — several since I left York in 1935.

Years ago, around 1910, my father had a farm on the Blue River about five miles below Hebron. Our home was between the Rock Island railroad and the river. That's where I spent my boyhood days, hunting, fishing and swimming.

Your article brought back many old memories, including one about an old mansion about four miles southeast of Hebron, at that time known as the "Lake Mansion." I remember it as an enormous house with several large chimneys, a 2 1/2 story affair appearing to have many rooms. We were told that a family from the East Coast had become quite wealthy from a patent on evaporated milk, had bought the land, and had built the mansion in real Western style, but I cannot verify this legend.

Earl B. Mitchell Long Beach, CaliforniaSir/ As a born and raised Nebraskan, I have enjoyed reading in NEBRASKAland about things that used to pass me by. I must say I loved this issue [March] the best. The pictures were gorgeous (any Texan would have to agree) and I can't tell you how much I loved the article "Gems In The Rough." It could have been longer with more pictures. Thanks for bringing back happy memories of tramping around lovely old houses myself.

Roxie Bronstad San Antonio, Texas Who Owns A River?Sir / I was impressed with your brief, but worthwhile article in the November 1972 issue of NEBRASKAland entitled "Who Owns a River?"

"Having grown up in Nebraska, now living just across the Missouri River in Vermillion, South Dakota, I can thoroughly appreciate what a river should look like. And, being an ecologist in a position to teach, I can only hope that it is possible to instill in younger people the real need for wild rivers, as well as other wild natural areas. There is so little of what is really natural left in man's progressive world that when we have something as natural as a stretch of river, it demands that people speak out to help keep it that way if possible. Who Owns a River? may be a question which only the courts can answer. Justice William O. Douglas, in an article in a recent issue of The Living Wilderness, points out that inanimate objects (if they are indeed inanimate) must have advocates for their survival, for they are unable to speak for themselves. To quote Justice Douglas in his article:

"The river, for example, is the living symbol of all the life it sustains or nourishes- fish, aquatic insects, water ouzels, otters, fishers, deer, elk, bear, and all other animals, including man, who are dependent on it or who enjoy it for its sight, its sound or its life."

Additionally, we have a responsibility to the future, and keeping a part of our landscape in its natural state is part of that responsibility. Too little is yet known about the ecological functions in natural systems to destroy them at will. Indeed, there will be future generations of people who for one

MUTCHIE'S Johnson

Lake RESORT

Lakefront cabins with swimming beach

• Fishing tackle • Boats & motors • Free

boat ramp • Fishing • Swimming • Cafe

and ice • Boating & skiing • Gas and oil

• 9-hole golf course just around the corner

• Live and frozen bait • Pontoon, boat &

motor rentals.

WRITE FOR FREE BROCHURE

or phone reservations

785-2298

Elwood, Nebraska

LIVE-CATCH ALL-PURPOSE TRAPS

Writ* tor

FREE

CATALOG

Low as $4.95

Traps without injury squirrels, chipmunks, rabbits, mink, fox, rac-

coons, stray animals, pests, etc. Sizes for every need. Also traps for

snakes, sparrows, pigeons, crabs, turtles, quail, etc. Save on our low

factory prices. Send no money. Free catalog and trapping secrets.

MUSTANG MFG. CO., Dept. N-34, Box 10880, Houston, Tex. 77018

GUN DOG TRAINING

All Sporting Breeds

Each dog individually trained on

pen-reared quail, pheasant, pigeon,

and also worked on native game.

Ducks for retrievers. Obedience

training is a part of the gun dog

program.

Midwest's finest facilities.

Pointers and Labradors for sale:

pups and young dogs with training

started —$75.00 and up.

WILDERNESS KENNELS

Henry Sader-Roca. Nb.

(402)435-4212 68430

Browning

Our EXCLUSIVE DISCOUNT PLAN on all

BROWNING products will save you up to 20%.

This includes guns, ammunition, archery, cloth-

ing, boots, tents, canoes, gun cases, rifle scopes

and fishing equipment. Inquire ... it will save

you $$$. Big discounts on other sporting goods.

PHONE: 643-3303 P. O. BOX 243 SEWARD, NEBRASKA 68434

Remember Mom

on Mothers Day

Give her A

Beautiful

Red Pump

For A Yard

Ornament or

for her Flower

Garden.

#110 Pump $19.95

Wt. 4 Lbs.

+ Ship. + Tax

Karedon Ltd.

2711 No. 19th, Lincoln, Ne 68504

MUTCHIE'S Johnson

Lake RESORT

Lakefront cabins with swimming beach

• Fishing tackle • Boats & motors • Free

boat ramp • Fishing • Swimming • Cafe

and ice • Boating & skiing • Gas and oil

• 9-hole golf course just around the corner

• Live and frozen bait • Pontoon, boat &

motor rentals.

WRITE FOR FREE BROCHURE

or phone reservations

785-2298

Elwood, Nebraska

LIVE-CATCH ALL-PURPOSE TRAPS

Writ* tor

FREE

CATALOG

Low as $4.95

Traps without injury squirrels, chipmunks, rabbits, mink, fox, rac-

coons, stray animals, pests, etc. Sizes for every need. Also traps for

snakes, sparrows, pigeons, crabs, turtles, quail, etc. Save on our low

factory prices. Send no money. Free catalog and trapping secrets.

MUSTANG MFG. CO., Dept. N-34, Box 10880, Houston, Tex. 77018

GUN DOG TRAINING

All Sporting Breeds

Each dog individually trained on

pen-reared quail, pheasant, pigeon,

and also worked on native game.

Ducks for retrievers. Obedience

training is a part of the gun dog

program.

Midwest's finest facilities.

Pointers and Labradors for sale:

pups and young dogs with training

started —$75.00 and up.

WILDERNESS KENNELS

Henry Sader-Roca. Nb.

(402)435-4212 68430

Browning

Our EXCLUSIVE DISCOUNT PLAN on all

BROWNING products will save you up to 20%.

This includes guns, ammunition, archery, cloth-

ing, boots, tents, canoes, gun cases, rifle scopes

and fishing equipment. Inquire ... it will save

you $$$. Big discounts on other sporting goods.

PHONE: 643-3303 P. O. BOX 243 SEWARD, NEBRASKA 68434

Remember Mom

on Mothers Day

Give her A

Beautiful

Red Pump

For A Yard

Ornament or

for her Flower

Garden.

#110 Pump $19.95

Wt. 4 Lbs.

+ Ship. + Tax

Karedon Ltd.

2711 No. 19th, Lincoln, Ne 68504

reason or another will want, or need, to have natural areas. This generation certainly has not the right to take away the opportunity for future generations to observe, enjoy, study and understand nature as it has been for hundreds, perhaps thousands, of years.

George R. Hoffman Professor of Biology University of South Dakota Vermillion, South Dakota BrownvilleSir / The article on Brownville was extremely accurate. I have been through the town many times during the past five years and have seen the problems mentioned. I didn't interpret the article as being one of attack, but one of criticism — very fair, justified criticism. We read this kind of truth occasionally to put everything in perspective, as your beautiful photography and stories would have most people believing Nebraska is perfect. This might be the motivation which brings Brownville around to what it could be.

Jeffrey Pokorny Schuyler, Nebraska Winter CoverSir / Having read your article on "Winter Cover" in the January issue, I am very impressed, yet know how true it is what the article brought out — the fact that good cover is a vital element for many animals to survive through the winter. Where I live, it is very easy to tell which fields hold pheasants. Some farms around us don't have one pheasant because of fall plowing, ditch mowing, fences and excessive use of sprays.

We have suitable places for pheasants on both my farms. Every year we set aside idle land which is sowed for pasture to give pheasants good cover. Also, we avoid excessive spraying. We mow no ditches and let waterways and fence lines go.

Sig Boschelman Fordyce, Nebraska How To Boil FishSir / We have been to several fish boils in Wisconsin's Door County. They took place outdoors and we found them to be most interesting. The fish were delicious. Little did we dream we would be able to enjoy such a specialty in our own home. Recently, we boiled some coho salmon our son had caught in Michigan. Thanks for sharing the recipe with us.

Mrs. Lester L. Ellison Holmesville, Nebraska Roundup Of FortsSir / Warren Spencer's article in the March issue was very interesting. I note that Fort Kearny is marked inland from the Missouri River, about in Pawnee County. Recently, I read an article in the Montana Historical Society's magazine that spoke of the development 8 of the original Fort Kearny on the Missouri River at the point where Nebraska City is now located.

It is interesting to note that there was a Fort Kearny No. 3 that was erected in Wyoming, according to this historical review of frontier forts, but that it was abandoned when the Indian uprising became so intense that those far-distant forts could not be supplied.

Fred E. Bodie Lincoln, Nebraska Bad ExperienceSir / Like many other sportsmen of my acquaintance, I had heard stories, and read advertisements about the wonderful pheasant hunting in the state of Nebraska. At last the financial means and time were there for me to make a trip to your state to hunt pheasants. To say the least, the hunting was very disappointing. This was not because the birds were absent, but because it was almost impossible to find a place to hunt. I spent nearly one week driving around eastern Nebraska asking one farmer after another for permission to hunt and getting refused time after time after time. In addition, I would estimate that 70 to 80 percent of the land was posted with "No Hunting" signs, and, of course, in these instances I did not inquire at all.

I did not ask to hunt around buildings, in standing corn, milo, or soybeans, or around cattle. I specifically asked to hunt stream bottoms, fence lines and shelterbelts. I have hunted for many years in a number of states, and I have never been subjected to such a barrage of verbal abuse on the part of farm people as I was in Nebraska. Instead of a simple no to my inquiries regarding permission to hunt, many times I had to listen to farmers launch an emotional attack on me personally as a hunter. I'm no different than any other white middle-aged man of moderate means, and I was trying to be as much a gentleman as possible, so I must assume that this sort of behavior on the part of Nebraska farm people is not unusual. The only conclusion I can arrive at is that a very significant percentage of Nebraska farmers are a very ill-mannered, ill-tempered, sour, sorry lot of people. The first few times I was treated this way, naturally, I reacted with some anger, but after a while, when I began to see this type of behavior present as a pattern, I began to feel sorry for these people. Any group of people that are that untrusting and sullen and have that much hate in their hearts deserves to be pitied. I saw many churches throughout the Nebraska countryside as I drove around. One has to wonder what is being taught in those churches.

I am only one individual and I only spent around $250 while I was in Nebraska, but you can be sure that I won't spend $250 in Nebraska again. I also have a number of friends who are hunters who will hear of my experiences, and, of course, so will the outdoors editor of my local newspaper.

NEBRASKAlandBefore the farmer says to himself 'Great, he won't be back again to hunt,' let me remind him of a few facts of life. I am just as capable as he of writing to my elected federal representatives. I can write and say that perhaps the federal government should provide more recreational opportunities for the average family by forcing farmers, by financial means, to open up their lands. I can write and say that perhaps the individual private farmer is a thing of the past and that more and more American farming should be taken over by government bodies or large business concerns. I can write and state my opinions on such things as beef import quotas, foreign grain deals, leather import quotas and grain price supports. You can bet my opinions won't be stated in favor of the farmer. And, let me remind the farmer that in terms of numbers, he is by far the minority.

Let's hope that the next time a hunter drives 700 miles to Nebraska after pheasants, he leaves for home with less of a bitter feeling toward Nebraska than I did. —

James R. Sommerville Toledo, Ohio Good VisitSir / After two years of planning, we finally got to hunt in Nebraska. Everything was perfect except the weather. We hunted two days of the five we were in Oxford because of an early storm. I saw more game than I had seen in my entire life. We would like to thank everyone in the Oxford area for making ours a memorable experience.

Jack Mariner Jack McKinn Camden, New Jersey Zigzag ZonkSir / As a displaced Nebraskan in Michigan, I too found the article "Zigzag Zonk" in the June issue of NEBRASKAland distasteful. However, I find the responses of two readers in the November issue (Speak Up) even more so.

I find it difficult to understand the 'Johnny-come-lately' ecologists who find it necessary to castigate the true sports hunter who, through self-imposed taxation, license fees and outright donations, has been the prime financial support of land acquisition, law-enforcement programs, research, reintroduction of species and introduction of new species of wildlife by various game commissions. It would seem appropriate if, indeed, they would join forces to combat the real despoilers of the earth's ecosystem, namely the agri-industrial complexes and governmental agencies that show so little regard for the earth.

Might I also suggest that they employ themselves in educating the young in true sportsmanship and sensible ecological control of the environment, as hunters and fish ermen have done for years. Should they find it impossible to do these things, then the least they can do is to keep their mouths shut and permit those of us who have been engaged in this work in the past to continue.

Hugh R. McGhghy Warren, Michigan It's Bad Out ThereSir / Pollution has been growing worse since I came to this country in 1912 and liked what I saw. What has caused it? Well, man's greed for money has had much to do with it. Now, there will be much shout ing through the news media, and I hope they can get something done.

During every broadcast, radio station KFAB in Omaha, and others like it through out the state, is telling farmers just what poison to use. Every farm paper does the same thing. Our once-rich black soil has turned gray and won't stay in the fields any more. It washes away or blows out.

Nature is the only thing which can do something about our situation, and it is working on the case. I am 82 years old and would like to do a littie more fishing before I sign off, but it looks doubtful. Even the trout streams in my area are polluted.

Tom McCann Bayard, Nebraska

for the Record

the purpose of the Game and Parks Commission

commission administrationEvery entity, be it an individual, a corporation or a government agency, must have a reason for being —a purpose. The Nebraska Game and Parks Commission is no exception, and in 1972 the department undertook a program to re-examine and re-evaluate its role in state conservation.

To serve a stated purpose, goals must be set as a basis to chart the direction of progress. For goals to be valuable, they must be broad and far-reaching. They must be forward or future-oriented, with the recognition that the future moves toward the present whether or not we move toward the future. As we set goals, therefore, our view should be as wide as the horizon, but with our course directed toward meeting the light of the approaching sunrise, rather than in chasing shadows of the retreating sunset.

The Nebraska Game and Parks Commission has widened its perspective through the following purpose and goals.

Purpose: Husbandry of the state's wildlife, park, and outdoor recreational resources in the best long-term interests of the people.

Goals: (1) To plan for and implement all policies and programs in an efficient and objective manner. Basic to the approach must be the commission's formula tion of policy which takes into consideration the concerns of the citizens of the state and the viewpoints of the staff. Only through a team approach can the complex task of wildlife conservation and outdoor recreation management be accomplished.

(2) To maintain a rich and diverse environment in the lands and waters of Nebraska. This agency is charged with the welfare of wildlife resources in Nebraska and must be concerned with the maintenance of entire plant/animal communities and the basic resources such as soil, water, air, land forms and gene pools, which constitute the foundation of these wild communities.

(3) To provide outdoor recreation opportunities. The commission must develop and maintain park and wildlife areas, and provide for the use of other public and private lands and waters for both the consumptive and non-consumptive user.

(4) To manage wildlife resources for maximum benefit of the people. While it may be necessary to take reasonable steps to manipulate wild animal population levels or to remove nuisance animals, the commission should first seek an ethic among land and water users that will insure a pattern of land use compatible with the many resident and migratory forms of wildlife.

(5) To cultivate man's appreciation of his role in the world of nature. Conservation of the wild community and its components ultimately rests not in the authority of the commission, but in the attitude of citizens and the values they place on wild things. Well-placed attitudes and values can come only from an understanding of the natural world, how it works, and man's role in it. The commission must provide the means by which Nebraskans can see themselves as a part of a total community of soil, water, plants, and other animals which make up our life-support system.

With the adoption of this purpose and these goals by the commission, the agency staff can now develop program objectives as yardsticks of progress. The questions are many. Why are we engaged in various activities? Are they bringing us any closer to our goals? Are they the best and most efficient ways of achieving our goals? What other programs could better accomplish these ends? We hope and expect that this effort will help us all pull together-public, commission and staff, in an attempt to reach the same ends and to better understand our reason for being.

THE LURE OF THE SAND HILLS

From a photo essay on the thin-legged avocet to a glance at what lies underneath, this issue focuses attention on

Our minds are attics cluttered with images we collect, sort through and save. Some tarnish and dim with years. Others stay clear and hold to life. Hazy and distant is the coyote which wanders still through a dusk-filled ravine; yet it persists today as strong a symbol of all that is wild and free as it did to your boy eyes. And forever quick and sharp is the sudden startle you shared with a bullsnake, surprised in the short grass. Some images remain hidden and dormant but then, like a jackrabbit, kick to life and run again across your mind when December stings, or perhaps the wind in April is right and leans the land to spring.

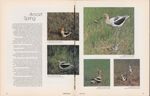

IN THE VAST, treeless sweep of Nebraska's Sand Hills, spring is prickly pear and spiderwort and yucca, and the land is fragrant with a desert scent. Where groundwater seeps to the surface, the sand supports oases of green meadow and teeming marsh, and the wind can be discovered in cattail and willow. Here, where water and land intertwine, the water birds come to construct their summer lives. Amid the prattling killdeer and busy, comic phalarope stands a surprising elegance. Like a badge of wilderness itself, with its striking shape and coloration, the American avocet strides conspicuous and bright along the shorelines of pond and pothole.

Even if it were not aggressive and bold, the avocet would find it difficult to conceal itself. It is a tall bird, standing up to 20 inches. Its blue legs, buff head, and flashing white and black body markings veritably propel it from its green and gray surroundings.

Intrude upon their nesting and feeding grounds, and the sky around you fills with avocets, circling and diving, the air ringing with alarm. Kleek, kleekf ple-eek, ple-eek come the cries of the plunging, darting birds. Ahead, closer to the nests,

more avocets stand as sentinels. When the inner defenses are penetrated, the protest becomes shrill, more urgent; the dives closer, faster, more reckless. Suddenly across your path flutters a "wounded" bird, "broken" wing trailing, its pathetic mewing promising an easy kill if you will but follow. Be careful now, for a nest is very near.

Examine the ground closely, for you will look right at a nest and for a moment not see it, so well do the eggs blend with the sand and stubble. Although no attempt is made to conceal them, discovering nests is a surprisingly difficult task. The shallow depression, about four inches in diameter and ringed with loosely woven bits of reed and grass, holds three to four olive-dappled eggs.

While there appears to be no ritualistic courtship display, elaborate posturings are often observed. One bird may open its wings and dance about, or teeter back and forth in the shallow water as if walking a tightrope. A deserted pond may suddenly fill with avocets in a procession of follow-the-leader or an exciting game of tag. Then, just as suddenly, the birds disperse. Prior to mating, a pair was,observed striding through the

Avocet

Spring

Avocet

Spring

water, occasionally pecking and caressing each other on the back with their bills. Then the hen assumed a graceful crouch in the shallow water, neck extended. The drake responded to this attitude of invitation with pretended reluctance, performing a charade of feeding and preening, occasionally tossing water with its bill. For several long minutes the hen remained motionless, ignoring the commotion of a parade of Wilson's phalaropes which paddled past on either side, busily feeding. Mating accomplished, the drake strode upon the shore and assumed a strange, deliberate pose —wings stretched straight up and neck extended —an attitude which lasted several seconds and was never witnessed again.

During incubation, the parents alternate between sitting on the eggs and feeding. Many nests are lost at this time to predators, bullsnakes taking a heavy toll in meadows densely colonized. Nests in low areas are often lost to flooding after severe rains. Once a nest is destroyed, no further attempts will be made that season.

Within hours of hatching, the chicks are mobile and expert at hiding in even the sparsest cover. Their juvenile plumage provides them excellent camouflage.

Taking to water immediately, the chicks show no hesitation, and are soon leisurely swimming and tipping up to probe for food.

Perhaps the most interesting feature of the avocet is its method of feeding. Dipping its long upturned bill below the surface and using it as a scythe, the bird sweeps its head from side to side, harvesting insect larvae, small crustaceans, even fish.

Once common to the eastern United States, the avocet proved too easy a target and was soon eliminated. Lack of habitat curtails its range today, but it is fairly widely distributed in the western United States and Canada. Avocets prefer alkaline water. Because of the many such lakes found on the Crescent Lake National Wildlife Refuge and Valentine National Migratory Waterfowl Refuge, these preserves provide the best avocet habitat in Nebraska.

To live a succession of long days amid wild song in a season when sun and grass increase, allowing the shell of human concern to shed itself moon upon moon, is to drink the finest wine. Voices you hear in the grass at dawn sing in the forenoon wind. Afternoon thunderheads build up and defy you to tarry. Nothing goes unnoticed then, nothing on land or water or in the sky.

The fourth chick to hatch was weaker than the rest. From the nest it frantically peeped, struggling to follow the others that ranged farther from the nest to seek their parents and the saving water. Finally it was alone. There was no protection now as the rain spattered down, then beat hard, smothering the calls of the parents and the pipings of the other chicks. When I brought the weakened chick to the water's edge, the parent avocet raised up from its feeding and stared, bill

dripping. We were very close and in the rain it showed no fear. We stared at one another. Here I was, no longer concealed by the blind, the mysterious presence it had known these many days. For a moment I thought I could see behind its stare and read — discern something that was not just instinct, not just the old circuitry of a machine. This foolish moment ended abruptly. The bird blinked, stretched, scratched the feathers of its breast, shook itself and turned, dropping its bill into the rain-disturbed water again. It stepped slowly off. Its nesting duty was done. I released the chick from the protection of my hands, setting it on the shore. Immediately it struggled to the water, swimming toward the other chicks which bobbed nearby, its purpose to escape, to swim, to live. It never looked back.

The nest disintegrated in the rain. Now my season here was finished. Reluctantly I began to pack my gear, dismantling the blind and shivering in the cold, wind-swept rain. I will be left with a tapestry of images which the years will disassemble and fade. But each spring from the clutter will rise the bright image of blue legs and impossible bill, standing above a nest, an apparition which is really undefined, knowledgeless and wild, a construction of wind, sun, rain, and the continual buzzing of water bugs. Let that suffice.

From the Pine Ridge to South Sioux City, this unique tour covers state's Sand Hills

NEBRASKA'S Sand Hills are unique unto themselves, offering hundreds of thousands of acres of stretch-out space for those with a yen for something a bit different from the humdrum, ordinary things in life. Scenic highways lace this land, opening special vistas to those who elect to probe the expanse. Crossing the wide Missouri at South Sioux City, U.S. Highway 20 meanders across northern Nebraska, giving travelers the option of a slower-paced, picturesque route. It provides a close-up look at this unusual land that becomes but a blur past the side window for those choosing the speed of the superhighway. From the horse races at Atokad Park in South Sioux City, this "Trans Western Route" offers interesting scenery and a saddlebag jammed full of activities. The lilt of Irish laughter seems to echo across the hills, as you enter O'Neill. At Valentine, you reach the "Heart of the Hills" and the hub of some must see attractions. En route, you may wish to pause awhile at Spring Valley Park at Newport to stroll through its elms. (Continued on page 64)

Prairie Grouse

Sharptail

Once more plentiful than the bison, encroaching agriculture reduced this "prairie hen" to remnant populations

THE PROMISE of a great network of fur-rich waterways beckoned 18th-century trappers into this nation's interior and led to white man's first encounter with the "hen of the prairie." At that time, sharp-tailed grouse seemed as inexhaustible as the great herds of bison blanketing the plains. ". . . and we put up grouse in such numbers that scarcely had laggers from one flock disappeared from sight before another covey rose," one early account read.

During lean years, while settlers adapted to prairie life, sharptails provided victuals for many a hungry family. Grouse were shot and trapped for home use, for sport, and for commercial marketing, but the sharptail's range spared them the carnage that had blighted the prairie chickens in heavily settled regions to the East. The uncompromising perversiveness of Nebraska's Sand Hills repulsed early settlement and provided sanctuary for the sharptail, while in other parts of their range they were forced to extinction.

The sharptail's original range was expansive, extending from Hudson Bay on the northeast and northern Kansas and eastern Iowa on the southeast, west across the plains and intermountain region to north-central Alaska and south to northern New Mexico. Pushed from much of that range by in tensified agriculture, sharp-tailed grouse extended their range into new regions as farm ing ventures failed, leaving more favorable habitats in their wake.

One of several subspecies, the range in Nebraska of the plains sharp-tailed grouse, Pedioecetes phasianellus jamesi, is confined largely to the 20,000-square-mile Sand Hills region.

The sharptail is known by many names, all descriptive, pin-tailed and sprig-tailed grouse, prairie hen and wild chicken being some of the more common ones. Early accounts often used prairie chicken and sharp-tail interchangeably, leading to considerable confusion in historical literature. After once holding a bird in the hand or watching its an tics oh a display ground, though, it is difficult to think of it as anything but a sharp-tailed grouse.

The two central tail feathers are about two inches longer than those on the side, giving rise to the sharptail's name. The sharp-tail's general appearance is that of a grayish brown, chicken-like bird. Adults weigh up to two pounds, with males slightly heavier than females. Pronounced, V-shaped markings cover the upper breast of both sexes. Super

SHARPTAIL RANGE

The sharptails' original range (top) was expansive, but as more brush land and prairie was cleared for agricultural use, they declined both in number and distribution. In isolated areas, though, they expanded their range as land-use changes created favorable habitats.

In Nebraska, the 20,000 square-mile Sand Hills region meets the sharptails' basic habitat require ments—unbroken expanses of grassland with small pockets of brushy cover. The expansion of irrigation will probably have a long-range, detrimental effect on grouse.

ficially, male and female plumages are identical. The tail is customarily spread in flight, revealing white feathers along the sides. Typical of all grouse, legs are feathered nearly to the toes with modified feathers along the toes forming natural "snowshoes" for winter.

Sharptails are strong fliers, often covering two or three miles in a single flight. The flight pattern, which cannot be noticeably distinguished from that of the prairie chicken, consists of a series of short bursts of strong wingbeats, interspersed with periods of gliding. While some band returns in Nebraska indicate movements up to 40 miles, most sharptails carry out their yearly activities within a radius of several miles.

Sharptails begin an elaborate courtship display in late February or early March that peaks in activity during late April and early May, although males may visit the grounds through much of June and occasionally into July.

Display grounds are usually from 100 feet across to an acre or more in size. These "dancing grounds" are generally located on a small hill or rise with little standing vegetation. Only the males dance, striving to claim small portions of the display ground, called territories, by intimidating other males with vocal and visual displays. Males begin arriving on the grounds about 45 minutes to one hour before sunrise and at the height of the breeding season display for as long as two or three hours, barring disturbances and depending on the weather. Activity is intense on bright sunny days and somewhat languid on cloudy, stormy days. Soaring hawks or passing coyotes may end the day's meeting early. Males also dance in late afternoon, but with reduced enthusiasm. While some display grounds may host as many as 50 or more males, an average ground in Nebraska holds about 10 birds. The same grounds are used year after year.

Early display activity consists of sparring and bluffing to determine individual territories on the dancing grounds. The most aggressive males usually command the center of the display area since it is preferred by the hens when they appear on the scene.

The actual sharptail display is an elaborate, somewhat comical combination of cooing calls (accomplished by the deflation of purple-tinged air sacs on the neck), rapid stamping of the feet, a mechanical clicking of the tail and headlong charges with wings drooping and tail erect.

Dr. D. G. Elliot, in 1897, provided an apt description of the whole affair.

The males, with ruffed feathers, spread tails, expanded air sacs on the neck, heads drawn toward the back and drooping wings (in fact the whole body puffed out as nearly as possible into the shape of a ball on two stunted supports), strut about in circles, not all going the same way, but passing and crossing each other in various angles. As the dance proceeds the excitement of the birds increases, they stoop toward the ground, twist and turn, make sudden rushes forward, stamping the ground with short quick beats of the feet, leaping over each other in their frenzy, then lowering their heads, exhaust the air in the sacs, producing a hollow sound that goes reverberating through the still air of the breaking day. Suddenly they become quiet, and walk about like creatures whose sanity is unquestioned, when some male again becomes possessed and starts off on a rampage, and the attack from which he suffers becomes infectious and all the other birds at once give evidence of having taken the same disease, which then proceeds with a regular development to the usual conclusion.

While the noises of an individual bird probably cannot be heard much more than 200 yards away, the combined din of a group of males displaying may be audible up to a mile away on a calm morning.

When hens visit the grounds, often in small groups, the males set up a terrific clatter of greetings. Seemingly unimpressed, the females wander coyly through the grounds, occasionally nipping at grass and seeds. At the female's pleasure, a male is selected and mating is accomplished with little show or fanfare.

By late May or early June, the hens no longer visit the grounds and males disperse, becoming quite inactive as if recuperating from the strenuous dancing chores. Much of their time is spent loafing in shady spots and browsing for insects and greenery.

By the end of April, most hens have sought out protected areas and have begun to fashion unpretentious hollows in which to lay their eggs. Thick clumps of grass or shrubby cover, on the cooler north- and east facing slopes, are preferred areas. The sharp-tailed grouse is not much of a nest builder, settling for a rough depression in ground vegetation, lined with whatever materials are readily available, usually grass, leaves and some feathers.

As soon as the clutch is complete, the hen assumes incubation duties. Clutch sizes range from seven to 17 eggs, but average

How They Compare

Feather patterns mark the species, sex and age

Species Characteristics

Sharptail Display

For several months during the spring male sharp-tails gather on dancing grounds for complex and ritualistic displays to attract hens for mating. The rapid, high-pitch cackling of the females, as they approach the grounds, is countered with leaps into the air by the males to advertise their exact location. Displaying cocks not only attract females, but maintain individual territories on the dance grounds. One of the most remarkable displays is the "tail-rattling" (center left). With neck extended, tail erect and wings held out from the body, the male begins his dance by rapidly stamping his feet. While dancing, either in place or on headlong runs, he produces a loud series of clicks with his tail feathers. At the height of the "cooing" display (bottom left) males inflate their purple-tinged air sacs while bowing to utter throaty calls. At the termination of that display air sacs deflate and the bird often assumes an alert posture (top center). Aerieal battles (bottom center) sometimes result over territorial disputes, but more commonly they are just "ritualized fight ing" (bottom right), where males try to intimidate each other. By the end of June, only tracks in the sand mark the site of one of North America's most remarkable phenomenons. Though comical, the sharptails' display is an integral part of its ecology.

about 12. The eggs are protectively camouflaged in olive, dark buff, or brown, usually with dark brown speckling, and measure about 1-4/5 by 1-1/5 inches.

Hens follow a regular routine during incubation. In the early morning the hen leaves the nest to feed for a short period, returning to spend the entire day on the nest until another short feeding period before dusk. Hens are easily flushed by disturbances early in the incubation period but as hatching time approaches they hold closely to the nest.

Finally, somewhere near the 23rd day, the eggs begin to hatch. In Nebraska, most sharptail chicks hatch within a short space of time, generally during the first three weeks of June.

Because most grouse nest during such a restricted period, heavy rains or other adverse weather can drastically affect hatching success and the population entering the fall. Unlike the bobwhite or pheasant, renesting is less persistent among sharptail. Generally 50 to 60 percent of the nesting hens bring off broods, that by late summer will number only six to eight birds.

The downy young are grayish yellow, with black and buff markings above and a pale greenish yellow below. Chicks are precocial and roam about the nest to feed soon after hatching.

Adult grouse are primarily vegetarians, especially during the spring months before abundant insect hatches. Fruits that cling to the shrubby and herbaceous plants over the winter months make up the bulk of the sharptail's food through the breeding and nesting period. The fleshy red "hips" of the wild rose are the most abundant fruit during this period and make up much of the sharp-tail's diet. Seeds from the different varieties of goldenrod also figure prominently in the diet. Wormwood, sedges, spurges, clover and bluegrass are taken later in the spring. Juniper berries and agricultural grains are used when available. Grasshoppers and leaf beetles are taken at every opportunity as the season warms.

Soon after hatching, the brood is led away from the nest. Characteristic of gallinaceous birds, only the mother provides parental care. Brood cover is not appreciably different from nesting cover; consequently summer territory rarely extends beyond a half-mile radius. Much of the brood's time is spent foraging for insects.

The young chicks grow rapidly. By 10 days they can fly a little and by four weeks are well feathered and proficient on the

wing, though they continue to react to danger by freezing in place.

Broods seem to prefer to roost in the heavy cover of hill country. At daybreak they move to wetland meadows to spend the entire daylight period. Most of the early morning hours are spent feeding. During the day they rest, preen, dust on pocket gopher mounds, mock display and feed sporadically. Late in the day the broods begin to feed actively again before moving back into the roosting cover.

When eight to 10 weeks of age, the chicks resemble small adults and begin to show some independence from the mother.

Food habits change markedly during the summer, both for adults and the young of the year. The adults' diet is primarily made up of clover found in meadows and wetland range sites. As the young grouse mature, their consumption of insects drops from a high of over 90 percent of their total diet at three weeks of age to a low of eight percent when they are 12 weeks old.

Leaves and flowers of succulent plants, dry seeds, and fleshy fruits are important food items for adults and are used more by the young as the summer passes. Although the diet of the sharptails may include 200 or 300 different items, the great bulk of their food is composed of less than a dozen.

Sharp-tailed grouse, young and adult alike, seem to have little need for open drinking water. Dew meets some of the water requirements, and the insect diet of the young, and the fruit and green vegetation taken by all age groups provide moisture when free water is not available. Except as water abundance affects plant growth, it does not seem to be an important feature of prairie grouse habitat, even though some observers have reported grouse using windmill overflows. Ranchers often mention that they have seen grouse perched on the edges of stock tanks.

Flock size increases in the fall, and a rather loose social structure is maintained. Young male grouse of the year, virtually identical to the adults by September, gather with adult cocks to frequent the display grounds. Though no mating occurs during the fall, males congregate on the grounds and participate in a half hearted version of spring activities.

Food is abundant during the autumn months and little time need be spent to sustain sharptails. Birds near agricultural lands may take to foraging in the grain fields while those on wild lands feast on the natural crops of summer. Greenery, such as clover, and insects become less important in the fall diet. The fruit of the wild rose is again the most common food, along with the fruits of plum, poison ivy, ground cherry, nightshade and snow berry. Smartweed and dandelion are also important crops for the sharptail.

By late fall and early winter, sharptails gather into large flocks. Some research indicates that flocks are still segregated by sexes. Groups of 50 to 100 are not uncommon. Winter snows change their sedentary life of autumn as abundant food and cover diminshes. More time must be spent search ing for food and desirable roosting sites.

Seton, in the late 1800s, noted this change in grouse habit and wrote: 'They now act more like a properly adapted perching bird, for they spend a large part of their time in the highest trees, flying from one to another and perching, browsing, or walking about among the branches with perfect ease, and evidently at this time preferring an arboreal to a terrestrial life."

Night roosts on the ground are still used by the sharptails, though, the heaviest of cover being sought for this purpose. When deep powdery snows cover traditional roost ing sites, sharptails bury themselves in drifts, roosting in ruffed-grouse fashion. There may be some local movement to the more protected wood and shrub-lined rivers and streams during severe winters.

During the winter months, sharptails subsist mainly on the buds of the poplar and fruits of the wild rose. Grain is taken when ever available. Plum, goldenrod, poison ivy and juniper berries are consumed in substantial quantities.

While most authorities agree that predation is not an important limiting factor for sharp-tailed grouse, they are taken by flesh eating mammals and birds. During the winter months when sufficient food and satisfactory habitat are in short supply, some grouse are victims of predators as well as disease and parasites. These mortality factors are probably most prevalent when birds are stressed by the natural elements.

Cooper's and sharp-shinned hawks are probably the greatest avian threat to the grouse, but most research indicates predation by raptors is uncommon. Grouse may be more vulnerable when snow roosting or displaying. Foxes and coyotes occasionally take adult birds but are not significant predators. During the nesting season, skunks, crows, bull snakes and ground squirrels destroy some nests.

Sharptails, like most domestic and wild animals, are host to a number of diseases and parasites but rarely are any of them significant

"An obvious fact about both hunted and unhunted species is that there is a limit to the population level that may be reached. This level is almost always controlled by available habitat. The excess life produced is lost to such direct decimation factors as predators, disease and parasites, weather and accidents. Predators will take whatever prey is available. The factor controlling prey availability is habitat. It is common knowledge among anyone concerned with wildlife that the way to fight predation is by improving the habitat—not by killing predators."

Sharp-tailed grouse have been with us for millions of years, and have weathered the worst of the elements and natural enemies pitted against them. Only man seems capable of deciminating their numbers. If we can only realign our values and priorities to include the preservation of sharp-tailed grouse habitat, each spring will ring with their frantic dancing just as surely as the Sand Hills around them will flow green again.

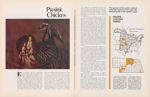

Prairie Chicken

This grouse of the prairie suffered under the market hunter's gun and spreading bite of the settler's plow

EARLY colonists became acquainted with the heath hen, an Eastern subspecies of the prairie chicken, as soon as they arrived in Massachusetts and Virginia. As pioneers filtered over the Eastern mountain ranges and onto the plains, they encountered prairie chickens in numbers as abundant as "the sands of the seashore." Early literature abounds with accounts of tremendous prairie chicken populations. Predictably, man moved hastily to utilize and abuse the plentiful fowl. Reports from market hunters' day books are striking. In Iowa, three men killed 410 prairie chickens in three hours on one 80-acre field. Roosts in Missouri were reported to extend for more than a mile. Other accounts tell of birds in trees as thick as blackbirds, their weight often breaking the branches. In Nebraska, one early writer recalled that 300,000 prairie chickens were shipped out of the southeastern and eastern part of the state in 1874 alone. The demand for grouse in Eastern markets, the development of efficient railway shipping, and the willingness of individuals to pillage a seemingly unlimited resource were factors that combined to dramatically reduce the prairie chicken population. Encroaching agriculture, resulting in the reduction of suitable grouse habitat, proved the final blow. By the early years of the 20th Century, prairie chickens had declined to only remnant populations.

The original breeding range of the greater prairie chicken, Tympanuchus cupidopinnatus, occupied an area bounded on the east by western Pennsylvania; on the north by southern Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota; on the west by eastern Nebraska, Kansas and Oklahoma; on the south by northern Texas, southern Arkansas, Missouri, Illinois and northern Kentucky. Present distribution in the original range includes only isolated pockets in Missouri, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, Kansas and Nebraska. Following the plow west and north into once unsuitable areas, the chicken's range expanded and substantial populations are now found in other states, including Nebraska. While limited agricultural production proved beneficial for prairie chickens in these new areas, extensive conversion to crop production in former range reduced the grassland habitat below the level required for their survival.

In Nebraska, insufficient winter food seems to limit prairie chicken expansion. Its primary range is located on the southern and eastern borders of the Sand Hills where grain is available. In areas where the conversion from grass to cropland exceeds 60 percent, the chicken has been almost entirely eliminated. In southeast Nebraska, several isolated flocks of prairie chickens continue to survive where small pockets of grassland exist among the rolling cropland.

There are three living prairie chicken subspecies. The greater prairie chicken, which occurs in Nebraska, is the most abundant. The other two subspecies, the Attwater's prairie chicken of southeastern Texas and the lesser prairie chicken of the south central states occur in restricted ranges and limited numbers.

The greater prairie chicken is slightly larger than the sharptail. Males average a little over two pounds and females about one pound, 10 ounces.

Males are predominantly rufous brown, broken by cross-barring over most of the body. The breast and belly are uniformly barred with brown and white. Males have tufts of stiff, elongated, dark-colored pinnae, or ear feathers, that stand erect during spring displays. Under each pinnae is a loose patch of brightly colored orange skin called an air sac, or tympani. These sacs are capable of

PRAIRIE CHICKEN RANGEOnce there were four North American subspecies of prairie chicken (top). The heath hen of the northeast is now extinct. The Attwater's and lesser subspecies occur only in limited areas and decreasing numbers. For now, the greater prairie chicken seems secure.

The eastern portion of the Sand Hills is the primary prairie chicken range in Nebraska. Isolated populations still occur in parts of the south east and southwest. Over most of the state they are holding their own, but compared with the sharp tail, their future is dark.

great expansion. Males also have fleshy, orange-colored eyebrows. The tail is short and rounded, accounting for the colloquial name "squaretail." The under-tail coverts are white with some brown spots. Legs are feathered to the toes, and feet are more yellowish than those of the sharptail. Females are superficially identical but have shorter pinnae and lack the air sacs and orange eyebrows. The tail feathers of females are barred and the males only slightly barred or solid brown.

The commencement of the spring booming season in late February marks the breaking up of winter flocks into smaller groups of separate sexes. While hens linger on the fringes of display grounds, males begin a most spectacular natural phenomenon. On display areas similar to those of the sharptail, called "booming grounds," each male vies for favorite territory which females will later visit for mating.

Males arrive on the wing or walk to the grounds shortly before sunrise. The morning performance generally lasts 11/2 hours or more. Unlike the sharptail's show, the prairie chicken's display is largely an individual effort unless one bird becomes involved with another in a territorial dispute. The display begins with short, headlong runs terminated with abrupt stops and rapid stamping of the feet. During much of the display, males erect their pinnae like warbonnets and inflate their air sacs until they look like small oranges. With wings drooping and tail spread to its full extent, the male produces a resonant booming sound for which he is known. The call is a series of three notes, each a bit higher in pitch and likened to the sound made by blowing across the open neck of a bottle. The air sacs are then rapidly deflated. At this point the bird may jump a foot or more into the air, uttering hen-like calls and whirling in what has been described as an attack of epilepsy combined with St. Vitus' dance. With heads lowered, they run to in timidate neighboring males and may actually engage in aerial battles, with a few lost feathers the only injury.

By early May, most hens have begun to nest. Heavy grass cover is preferred for the hollowed-out depression. An average of 12 olive- or tan-colored eggs flecked with brown comprise the clutch. The first eggs are pipped on about the 23rd day of incubation. Hens occasionally speed the process by removing bits of shell with their bills. Hatching is well synchronized, the time from first pipping to emergence of the last chick often being less than one hour.

Young spend their first few hours near the nest and begin feeding on insects almost immediately. During their first weeks, more than 90 percent of their diet is made up of insects. The feeding habits of adults are some what similar to those of the sharptail, but they rely more on grass and weed seeds. During the autumn and winter, agricultural grains become important. Shrubby fruits, while important, are probably not used extensively.

When the chicks' aptitude for flying is developed and they are able to feed regularly by themselves, the broods tend to move to higher ground nearer grain fields. At about eight to 12 weeks, broods begin to break up, and by September, the old cocks and the males of the year begin to congregate on the booming grounds again. Flocks made up of both sexes often unite during the day to loaf and feed.

Autumn brings about a great change in diet as animal foods assume secondary importance and grains, wild fruits and seeds be come available and are heavily utilized. Rose, smartweed, wild flax and clover are the most important fall foods of the prairie chicken. Late fall flocks of 20 to 30 chickens are common, and 50- to 100-strong flocks still occur, though they in no way approach their former abundance.

Unlike sharptail habitat, woody cover is important to prairie chickens only during severe weather. In areas where natural shrubs and herbaceous cover are limited, shelter belts become important components of prairie chicken winter habitat.

Winter is a critical link in the prairie chicken's annual life cycle. Cultivated grain becomes a staple food and dense stands of grass a necessity for survival. The prairie chicken's winter regime consists of feeding during early morning and late evening and loafing during midday.

Adverse weather, disease and parasites, predation and natural accidents all take a toll on the prairie chicken's population, but as with the sharptail, land-use practices have ultimate control over their destiny. The decline of native grasslands and shelterbelts, and clean cropping practices often spell the end of local populations.

Since his first meeting with the prairie chicken on the East Coast, man has been the determining factor in prairie chicken abundance, first through direct means by hunting, and now through the indirect way in which he manipulates habitat. If prairie chickens survive, it will probably be in spite of man's actions, not because of them.

Research provided alternatives for preserving prairie grouse; land-use will ultimately determine its destiny

Management

THE MANAGEMENT of any wild species is a discouraging matter at best, normally in competition with other land uses. Even on public lands, the voices of various interests figure prominently in management decisions. Seldom are these decisions based solely upon the most beneficial perpetuation or maximum production of wildlife. The welfare and proliferation of wildlife has all too often been relegated to a position of secondary importance.

If wildlife management on public land is discouraging, its counterpart on private land is disheartening. Though state and federal biologists may advise, the landowner has the final word on how he utilizes his land. His decisions, by necessity, are based on the economics of his operation.

The most serious, long-term threat to existing grouse populations is the secondary resurgence of mass conversion of grasslands to intensified agricultural use. Agriculture's initial surge in the late 1800s proved beneficial to grouse, but as the ratio of cropland over grassland increased, they were eliminated from much of their original range. The development of modern agricultural techniques, such as fertilization and irrigation, make possible the tilling of previously unarable lands and encourage further encroachment on native grasslands.

The long-range effect of pivot irrigation

in the Sand Hills on grouse populations is

being watched with considerable interest.

Though the initial increase in cropland could

provide a valuable winter food supplement,

the removal of large tracts of natural grass

land habitat could be detrimental to grouse

numbers. Development of the Sand Hills

could prove to be a small-scale duplication

of the land-use policies that forced grouse

from much of their range in the 1800s. The

eastern edge of the Sand Hills, Nebraska's

primary prairie chicken range, would be the

most drastically altered.

primary prairie chicken range, would be the

most drastically altered.

The most immediate threat to prairie grouse in Nebraska though, is overgrazing. Most researchers agree that livestock abuse of grasslands can be the major contributing factor to low numbers of grouse in local areas. Overgrazing undeniably reduces the number of grouse an area can support.

Bob Wood, a former Nebraska Game and Parks Commission biologist who studied the prairie grouse, noted that good range management is also good grouse management.

'The primary concern of ranchers is producing cattle for a living and not raising grouse . . . [but] . . . good range management produces more beef and more grouse than does overgrazing . . . range studies and research are providing ranchers with information they can use to produce more beef on their grassland while keeping it in better condition . . . Nebraskans can have their grouse and eat their beef, too," Wood commented.

Prairie fires have always been a natural element of grassland ecology and a significant influence on grouse numbers. When property, livestock or human life is jeopardized, fires must justifiably be considered something less than desirable. However, the vegetative diversity of grasslands, so important to the survival of many wildlife species, has always been maintained by prairie fires. Fire rejuvenates the prairie by encouraging an increase in forbs—important wildlife food. It removes dead growth from pastureland and creates vegetatively diverse islands that meet such life requirements as loafing sites, nesting cover and winter feeding areas. Generally speaking, limited and controlled prairie fires are advantageous to grouse populations.

Hunting, both legal and illegal, can have some influence on grouse populations. The regulation of hunting pressure is basically the only tool that the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission has to encourage prairie grouse proliferation on private land. By manipulating season dates, bag limits, and hunting areas, a renewable resource can be utilized without threatening its viability or continued existence.

Sighting counts made by rural mail carriers as well as data gathered by commission personnel from spring display ground counts, summer brood counts and the previous season's hunter success survey are compiled and used as guidelines in setting the fall season. The primary concern is the preservation of the prairie grouse, and hunter harvest is permitted only after it is determined that no detrimental effect will result.

Most researchers agree that up to 60 percent of the fall populations could be har vested without affecting the breeding core necessary to replenish the population. Estimates in Nebraska indicate that only four to five percent of the population is harvested by hunters each year. Annually, this amounts to somewhere between 40,000 to 60,000 grouse, in a ratio of three sharptails to each prairie chicken taken. Degradation of the grouse's habitat, not managed hunting, will be the factor that determines the future of the prairie grouse.

Diseases and parasites afflicting the grouse, predation, and weather are other factors limiting grouse populations and points to be considered in the mangement of this prairie bird. Under normal conditions, diseases and parasites are of little influence in determining grouse abundance. Predation and adverse weather conditions significantly affect grouse populations only when coupled with inadequate habitat.