NEBRASKAland

for the record

The Winds of Change

Throughout the United States, things are changing. That is a well-worn statement by now, but it is true —in just about every phase of American life. Change has come, too, to the land. Since the homesteader days in which Nebraska began, the land has undergone almost constant alteration at man's hand. Some of this change was for the good; some for the bad. But land-use has reached a stage today where a broad, sweeping program of regulation has become more than just an idle thought.

There was a time when landowners considered their domain to extend from the core of the earth to infinity above it. Such no longer holds true. There was a time when what a man did with his own land went beyond the bounds of control. That time has passed, and more and more regulations are being imposed on property owners. The land —even minute parcels of it —has become too valuable for any one individual to own completely. Like many of our other resources, land is finite; it has its limits. And now the nation faces the problem of managing that resource to meet the demands of people for more and better goods and services. Such is not an easy problem to solve.

Perhaps more than any one factor, urbanization has focused on the recognized need for wise management of our earth. One means of treating the problem has been to zone parcels for specific purposes, similar to the ways towns and cities zone areas for manufacturing, commercial building and residential use. That approach has had difficulty in wide applications, however. Often, zoning must deal belatedly with a hodge-podge of living areas and commercial regions in a given area. It is too often a stepchild of urban sprawl rather than the offspring of wise planning, and can become the tool for retaining predisposed organization. For zoning to work, it must be preceded by thorough planning, implemented prior to establishment of conflicting uses, and subject to fair and equitable landowner reimbursement.

The point remains, however, that something must be done to wisely manage and conserve the space left to us. In a state like Nebraska, where private ownership consumes 97-percent-plus of the area, relinquishing even a small amount of control over property will be a bitter pill. Our state was literally carved from a wilderness by homesteaders who, once they tamed the land, held it for their own and no one else's. Their pioneering spirit has lived on, and Nebraskans traditionally take great pride in their land ownership. It has been considered almost a sacred institution. Yet most landowners don't realize that they have never owned all the sticks in the bundle known as ownership. The federal government retained the right of eminent domain from the homesteader. Reservation of mineral rights is quite common, and it's a rare parcel that does not have some type of easement on it for public or even private purposes.

In the end, it comes down to the fact that the land belongs not to a man but to mankind, and it is everyone's responsibility to wisely manage it. And in the next five years or 10, a National Land Use policy will surely be formulated to work toward that goal as things continue to change.

NEBRASKAland

VOL. 51 / NO. 2 / FEBRUARY 1973 Published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Fifty cents per copy. Subscription rates $3 for one year, $5 for two years. Send subscription orders to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. commission Dr. Bruce E. Cowgill, Silver Creek, Chairman Northeast District, (308) 773-2183 William G. Lindeken, Chadron, Vice Chairman Northwest District, (308) 432-3755 Gerald R.Campbell, Ravenna, Second Vice Chairman South-central District, (308) 452-3800 James W. McNair, Imperial Southwest District, (308) 822-4425 Jack D. Obbink, Lincoln Southeast District, (402) 488-3862 Arthur D. Brown, Omaha Douglas-Sarpy District, (402) 553-9625 Kenneth R. Zimmerman, Loup City North-central District, (308) 745-1694 Willard R. Barbee, Director William J. Bailey, Jr., Assistant Director Richard J. Spady, Assistant Director staff Irvin J. Kroeker, Editor Warren H. Spencer, Senior Associate Editor Lowell Johnson, Jon Earrar, Associate Editors Greg Beaumont, Bob Grier, Photographers Michele Angle, Designer C. G. Pritchard, Illustrator Cliff Griffin, Advertising Director Juanita Stefkovich, Circulation Manager Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission 1973. All rights reserved. Postmaster: if undeliverable, send notice by form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska Travel articles financially supported by Department of Economic Development Stan Matzke, Director John Rosenow, Tourism and Travel Director Contents FEATURES GRAND NATIONAL: A MYTH EXPLODED 8 THE LAND AND WATER CONSERVATION FUND 12 DEER BY PERCUSSION 14 RIVER RAT 18 THE FISH OF LEWIS & CLARK 20 THE PARADOX OF HUMAN ECOLOGY 24 JOSLYN ART MUSEUM 26 FOUR FEET TROTTING BEHIND 34 BENCH SHOOTING 36 ALMANAC PIKE 38 HOW TO BOIL FISH 44 DEPARTMENTS FOR THE RECORD 3 SPEAK UP 7 NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA 42 WHERE TO GO 47 TRADING POST 57 OUTDOOR ELSEWHERE 58 COVER: Cottontail, photo by Bob Grier LEFT: Hoarfrost, photo by Greg Beaumont

Speak Up

NEBRASKAland Magazine invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to Speak Up. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters. — Editor.

WHO OWNS A RIVER?- I read Who Owns a River? in your November 1972 issue with special interest. The writer, who prefers to remain anonymous, is duly concerned about the channelization of the Missouri River between Yankton, South Dakota and Ponca. The more I read the article, the more I found the word channelization used with reckless abandon. Certainly this is an unimformed person, at tempting to distort people's minds. He fails miserably to differentiate between channelization and stabilization.

"How could a reputable magazine print an article like this without checking all the facts? Considering the kind of magazine you publish, I will be expecting to see a retraction, or certainly at least a modification of the article." —Mrs. Ruby Rahn, Newcastle.

I'LL TELL YOU-"I'll tell you who owns a river! The federal government or 'we the people' own the water and such being the case, should be responsible for the damage it does. The landowner bordering the water owns the bank and also the islands, and the land under the water to the middle of the channel.

"This family has owned and paid taxes on the Ellyson farm for over a hundred years. During my generation my husband has paid thousands of dollars and many hours of back-breaking work getting the river bottomland ready for cultivation. I taught school for 20 years and applied my wages on this work. We have maintained approximately 15 acres of beautiful campsite which people of the surrounding area have enjoyed free of charge. We have lost all that now.

"If people like you get your facts correct and we can overcome the opposition, perhaps in a few years' time, we can save what we have left. Now, I am no engineer, but this I know. The meandering river is not to be stopped, merely controlled enough to preserve its natural beauty and protect the landowners. A plan has been carefully worked out. The present meandering course is not to be changed or destroyed. Channelization is not our object, merely stabilization.

"If you anq other misinformed sportsmen will learn the facts before you condemn our cause, we may get something accomplished."—Mrs. Faye Ellyson, Newcastle.

WHO OWNS A RIVER - The article Who Owns a River? is very misleading. The author appears to know very little about the Missouri in this vicinity.

"'Channelization still threatens to deface the last stretch of the Missouri.' Channelization of the river is not being considered. That plan was thrown out about two years ago. Approximately one year ago, a task force was set up with representatives from both Nebraska and South Dakota to find a plan that would be agreeable to everyone, to protect the high banks from further erosion, but allow the river to meander between them. The Nebraska Game and Parks Commission was represented on this task force, so they should know there is no question of the river being channelized.

'"Only from Yankton to Sioux City does the river resemble the unbound days.' From Yankton to Ponca is the 'unbound' stretch. From just below Ponca to Sioux City the river has been stabilized (not channelized) for approximately 15 years." — Harold Hoesing, Newcastle.

WE DO —"Who is responsible for the gross misinformation concerning the article Who Owns a River? The first bit of misinformation: 'Channelization still threatens to deface the last wild stretch of the Missouri.' No one wants or wanted channelization! It is high bank stabilization or bank protection which is needed.

"Second: 'The wild stretch of the Missouri' is not from Yankton to Sioux City, but is, in fact, from Yankton to just below Ponca State Park.

"Third: 'Who will be responsible for the fish and fowl that disappear with channelization?' Once again —no one wants channelization! We want high bank stabilization and with that the back-waters and sandbars will still be there. Do you honestly think game fish can survive the constant erosion of at least 320 acres of land per year? What about the loss of the trees, grasses, underbrush andcroplands that are being used by deer, pheasants and other wildlife as feeding and nesting areas? Are these animals to be sacrificed to maintain a 'wild stretch of river?' How about the loss of land by the landowners, tax money to the states and beautiful recreational areas? Who will pay the bill? Incidentally, some of the best game fishing and goose hunting is found below Ponca State Park, where it is channelized.

"Fourth: 'Who will tell the children that once there was a wild Missouri?" Are you prepared to tell the children that the wide, muddy, swamp, invested with dangerous snags, unfit for boating, fishing or swim ming—which it soon will be —could have been a still beautiful expanse of river with bank protection?

"Yes indeed! Who owns a river? You do! I do! Everyone does! But who is responsible for the vast destruction of a river? Everyone is!" —Darrel and Betty Curry, Newcastle.

THAT'S WHO-"In Who Owns a River?, I think you have written the most biased article with the least true facts I have seen in quite some time. In the first place, there is no plan for channelization —it is for stabilization. If you would have read the engineers' report on this plan you would know that the river would have an average width of 2,500 feet and would be allowed to meander back and forth between the high banks. In the report it states that nothing will be done without the full approval of both states, and your Game and Parks Commission is one of the representatives for the State of Nebraska.

"You talk about the perennial flooding replenishing the sandbars. There has been no flooding and will not be since the dams were built and closed on the upper reaches of the river.

"You talk about ruining the fishing on the river. The fishing is already suffering with out any stabilization due to the excessively high flows from the dam each summer.

"I feel that for you to give a fair story on this you should obtain and read the engineers' report on bank erosion problems between Gavin's Point Dam and Sioux City, Iowa, prepared in conjunction with the task force appointed by the governors of South Dakota and Nebraska, and consisting of representatives of the Nebraska Department of Water Resources, the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission and the farmers in the problem area." —Earl Rowland, president, Missouri River Bank Stabilization Association, Newcastle.

BIG ONES —"In regard to your asking readers to report sites of large cottonwood trees (Speak Up, November 1972), I would like to report that in Carter Canyon, 10 miles southwest of Gering, there are many of these huge trees still living. These trees were full-grown 62 years ago when my father, Emerson Ewing, homesteaded the land on which they were growing. I live on the land now, and from my back door I can count 10 of them. One is a rare species not found anywhere else in the United States. It was discovered by a Nebraska State University [sic] naturalist 60 years ago, and is named for him —the Rydberg cottonwood." — Mrs. Goldie Wilson, Gering.

Grand National: a myth exploded

Unlike so many celebrity hunts, this one places the emphasis on conservation

8 NEBRASKAlandA FUNDAMENTAL rule of education is that information must be presented palatably. To get a point across a teacher must capture and hold his students' attention. For 36 years, Dr. Bruce Cowgill has been a professional educator, so it seemed natural that when he decided to call public attention to a serious threat to wildlife, it came in such a savory form. Dr. Cowgill, using Nebraska's mixed-bag diet, attracted celebrities like Roy Rogers, Bob Feller, Harmon Killebrew and Fred Bear. Lacing this attraction with an unusual assemblage of outdoor events, from falconry demonstrations to muzzle-loader competition, the educator captured the public's eye, ultimately focusing it on the wildlife-habitat dilemma. The result was Nebraska's first annual Grand National Mixed-Bag Hunt and Conservation Day. And, as a FEBRUARY 1973 premium, Cowgill's message went out—if wildlife is to flourish, habitat must be preserved and in creased, and hunters must Teach the way.

Silver Creek, straddling U.S. Highway 30 west of Columbus, had been bustling for months. As Dr. Cowgill put it: "When you have 490 people work ing in a town of 480, that's total involvement." Every storefront in town was festooned with a conservation theme.

Officially, the hunt wasn't to kick off until Friday morning, November 3. Unofficially, though, the core of the Kansas City Royals' pitching staff Roger Nelson and Tom Bergmeier —kidnapped a local duck hunter on Thursday, sweeping him off to his willow-and-reed establishment on the Platte River. Roy Rogers and Harold Ensley (outdoor radio and television personality from Kansas City)

launched into the hunt early, too, with a bit of waterfowling on the ponds near Petersburg.

Originally, guest hunters were grouped by teams. The "Moon Boys," composed of astronauts Wally Schirra, Deke Slayton, Stu Roosa, Charlie Duke and Joe Engle were forced to cancel the day before the hunt because of a moon shot rescheduling. Fred Bear, Roy Rogers, Bob Feller and Harmon Killebrew formed the "Big Wheels" team. State governmental figures manned the "Red Tapers." Nebraska's Game Commissioners were represented on the "Poachers" team and various outdoor writers made up the "Propaganders." Each team was issued one box of shotgun shells and one box of rifle shells, and various game species were assigned point values. Cowgill's plan called for team competition, but sometime during Thursday night's pre-hunt gab session many units fragmented and regrouped in a less orderly fashion. As a result, ballplayers hunted with game commissioners, movie stars with archery greats and outdoor writers with state dignitaries. A relaxed atmosphere where hunters of different back grounds and philosophies could share experiences as well as duck blinds was the result.

Come 4 a.m. Friday, the Grand National stirred to life as hunters, guides and dog handlers met over healthy portions of ham and eggs. Before predawn light, duck blinds on the Platte River from Richland to Central City, and northwest of Silver Creek were manned and ready.

Like a week of mornings before it, the Grand National opened with heavily overcast skies and threats of rain —exactly the doctor's prescription for good waterfowling. While every blind had a good supply of ducks around, most were high and snub bing decoy spreads.

With Harold Ensley's convincing calls, Roy Rogers dunked a white-fronted goose that drifted in on cupped wings. Mallards and bluebills that had moved in with the wet, cold weather provided most of the action though. Bob Feller, baseball Hall of Famer, downed a few mallards. Harmon Kille brew, the slugging first baseman of the Minnesota Twins, demonstrated that reflexes are the prerequisites for zippy bluebills as well as sizzling fastballs.

As hunters warmed up with steaming cups of coffee and a hot meal, Dr. Cowgill opened the afternoon's activities with his slide presentation of "Acres for Wildlife." Cowgill initiated the Acres for Wildlife program in 1969 to help preserve cover, the foundation of the wildlife resource, and to instil a conservation conscience in the general public. Since then more than 150,000 acres of habitat have been set aside in Nebraska alone and more than 2,000 individuals have become actively involved.

An abandoned farmstead hosted the after noons' first event, one usually not seen at one-box, one-shot or mixed-bag hunts. While most promotional hunts place the emphasis on the harvest of game, the Grand National proved an ideal matching of conservation activities and hunting.

"We wanted to get away from the blood and guts of hunting," Cowgill pointed out, "and present hunting in a different light. We wanted to involve hunters in the conservation picture, too."

Teams pitched into the task at hand with gusto. If the myth that hunters are interested only in game harvest was in anyone's (Continued on page 50)

the story behind the Land and Water Conservation Fund

Under this cost-sharing program, everyone in the state can be a constant winner

A BANKER in a northeast Nebraska community leaned back in his chair and lamented, "If I had to go through it again, I wouldn't do it." This man, project liaison officer for a recently completed Land and Water Conservation Fund (L&WCF) park development in his town, was referring to the "red tape" associated with obtaining federal and state financial assistance.

The L&WCF program has been active in Nebraska for about seven years and, while there is some red tape involved, it has been an extremely popular grant in-aid plan. Under it, funds are provided for outdoor recreation developments or park-land acquisition. It is interesting to note that the liaison officer/banker has since made application for an additional development project, and work on it is now under way. Such is the case with approximately 150 political subdivisions of the state which have projects completed or in progress.

The Land and Water Conservation Fund began with a study by the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission in 1958. In 1965, a federal act creating the fund went into effect. Since then, some $10 million in federal funds have been made available to Nebraska. State legislation was subsequently passed, delegating the Game and Parks Commission as the administering agency on the state level, with the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation administering the federal level. All federal money made available to Nebraska communities must first be allocated to the state as directed by state and federal law. Federal-Aid Division personnel of the Game and Parks Commission work closely with representatives of the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation, not only in processing applications, but recommending program changes which hopefully will keep documentation and other paper work to a minimum. Most programs involving federal or state grants have a certain amount of so called red tape associated with them. Constant review of the program facilitates putting the emphasis on physical facilities, rather than bogging down the projects with paper work.

Administering a program such as the has many rewards, not the least of which is the gratitude shown by benefiting communities. To see how they benefit, let's follow an actual small town from application to dedication. In FEBRUARY 1973 citing this Nebraska village, it will be necessary to cover two stages on the road leading to a completed park.

Application for 50 percent federal and 25 percent state funds was made by the village to purchase a small tract of land to be developed as a park. The application was duly considered, along with all other, similar requests received by the Game and Parks Commission, and this town was one of those recommended to the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation for funding. Ultimate approval comes in the form of a binding agreement between the federal government and the State of Nebraska, plac ing the latter in a position of prime responsibility for the money and the tangible property, in this instance a park, for which it will be expended. However, the state immediately "shares" this responsibility by consumating a state-local agreement and the action part of the project is under way.

As required under the program, this village hired an appraiser who determined the market value of the land by acceptable procedures. With state approval of the appraisal, the village paid for and took title to a 2.3-acre tract of land. Finally, the village board placed some assurance on the future use of this acreage by endorsing a formal resolution dedicating it to outdoor recreation in perpetuity. The project was audited by the Game and Parks Commission and a billing was filed for reimburse ment of the state and federal money to the local sponsor. However, this was only the beginning for this community, and before the acquisition project was completed they had made application to develop their new park.

Again, the new application went through the priority assignment and competition with other Nebraska municipalities, to ultimate approval by the state and federal government. This project, involving complete develop ment of the park, required expertise in the areas of design and construction. To satisfy this requirement, the village employed a consulting engineer. How ever, the final decision on what facilities would be included in the development was made by the people living in the community. Furthermore, the only way that this improvement would be sanctioned by the people was with the provision that the finished product include facilities for all ages.

With all possible interests of the community expressed, the park developments were designed, and in cluded a lighted baseball field, watering system, parking lots on the perimeter, playground equipment, horseshoe courts, lighted tennis court, basketball goals, croquet court, flower gardens, lighted flagpole, concession building, picnic tables and fireplaces. Construction plans were approved by the Game and Parks Commission and contracts were let to develop the park. At approximate 30-day intervals, the village billed the administering agency for 75 percent reimbursement of documented development expenditures. This project, as with the land acquisition, was audited upon completion and closed out. The paper shuffling stopped and plans were laid for a formal dedication.

If you have followed the story of this community, you have learned the basic procedures of a Land and Water Conservation Fund project from start to finish. Many Nebraska communities have gone this route in utilizing the $1,500,000 plus in federal money and $750,000 in state money annually, which is made available by national and state lawmakers. But let's return to our demonstration village project.

A dedication ceremony for Unadilla's Eastview Field took place on a sum mer evening in the park in the presence of state senators, village officials, project contractors, the project engineer and the real benefactors of the new park — people of the community. This is the moment of truth and the appropriate time for bouquets. This is when the emcee, who has worked as liaison of ficer with the Game and Parks Commission all through the project, expresses sincere gratitude for the fed eral and state financial help in bringing their park to reality.

As a representative of the administering agency hearing these words, one feels a warm sense of satisfaction and accomplishment. However, the words that ring louder and longer in this community, as well as most others across the state, are those which express thanks to members of the village for donated labor, material and equip ment, special board meetings, extra work by the city clerk, and above all else, the unanimous backing and official action of the governing village board. It is only through such dedicated effort and total community involve ment, however, that the Land and Water Conservation Fund program can be utilized.

Deer by Percussion

OFTEN, A MAN'S hobbies stem from his work, but conversely, hobbies frequently influence the type of work people go into. For Monty Weymouth of Chadron, the two interests —his vocation and his avocation — have been linked for most of his life; so much so that it is hard to tell where one ends and the other begins.

Hunting and target shooting with bow and gun and gun collecting are important pastimes, but they also play a part in Monty's work in a sporting goods store in Chadron. He and his father run the business, and Monty's knowledge of archery and firearms stands him in good stead both on the job and off.

Normally, Monty hunts deer only with a bow, having laid aside his rifle several years ago. This, despite the fact that he has a tremendous firearm collection. A few years ago, however, he did take to the deer woods with a gun —a muzzle-loading rifle. Joining him at that time was Joe Brickner, and they would hunt together again during the 1971 season.

Joe, a native Nebraskan from the Chadron area, now lives in California where he is president of an electronics firm. A skilled amateur gunsmith, collector and avid shooter, Joe was torn between using a muzzle loader and a recently completed, custom 7 x 57mm Ruger. Like all his other guns, it was a single shot. So, he settled on a suitable compromise by using each rifle on alternate days.

Hunting deer with a muzzle loader isn't too different from bow hunting. Although the effective range is greater, it does not equal a modern weapon. So, the same sneaky, cautious tactics are necessary. Mule deer are considered longer-range prospects than whitetails, but they offer counter ing advantages. They are not, for instance, as devious and flighty. Still, taking a poke at any deer with a black-powder burner at much over 100 yards is a little shaky. Joe may have even put him self at a disadvantage by swapping weapons daily, for his scope-equipped 7 x 57mm could be lethal at perhaps 300 yards, while the following day he was limited to the shorter range of the percussion gun.

On Saturday, the opening day of the 1971 deer season, Monty could hunt only for a few hours in the morning and again late in the after noon. Joe, however, would devote most of the day to strolling the hillsides and canyons with his 7mm. Monty passed his alotted time without a shot, but Joe fared better.

About 4:30 he eased around a bend in a canyon and saw a deer. A check through the scope revealed a rack, and he touched off a round. From 75 yards away, it didn't take him long to reach the fallen animal, but then he was in for a shock. There was no sign of antlers. He grabbed an ear and lifted, and there the antler was —but only one. The four-point antler on one side had been lost some where along the line, and the other one had been hidden in a bush. After the moment of anguish, he was relieved that the shot had not been an error.

With a second buck permit to fill, Joe voted to carry his muzzle loader on Sunday. His rifle was a twin of Monty's, a Navy Arms copy of an early percussion-cap Remington Zouave. Both were .58-caliber, but Joe was shooting round balls, while Monty went with 510-grain mini-balls which expand into the rifling upon firing. The two hunters separated, with Monty sneaking slowly along a canyon while Joe worked a ridge about a mile north. He was keeping slightly ahead so any deer that spooked might eventually move toward Monty.

The tactics worked, too, for midway through the canyon Monty heard a twig snap in the brush to his left. He stopped, looking and listening, and soon spotted a three-point, white-tailed buck skulking through the timber toward him.

"I would rather have gotten that whitetail than the biggest mulie in the Pine Ridge." he later admitted.

The buck paused frequently, testing the air and peering to his left. He was only about 60 or 70 yards away —a simple shot. Easing back the hammer as noiselessly as possible, Monty dropped the iron sights onto the chest area and fired. Quick as a bullet himself, the buck leaped into action.

Joe, who heard the first shot clearly, was still

trying to figure out where it had come from when

he heard a second. Monty must have set a record

for reloading, because his second shot erupted

just as the buck dropped behind a ridge. Another

clean miss. With a combination of good luck and

bad, he got another chance less than half an hour

FEBRUARY 1973

15

later. A mule doe standing quietly on a slope about

140 yards ahead possibly was suspicious of his

presence, but she wasn't alarmed. And there, not

far away, stood one of the biggest mule bucks

Monty had ever seen.

later. A mule doe standing quietly on a slope about

140 yards ahead possibly was suspicious of his

presence, but she wasn't alarmed. And there, not

far away, stood one of the biggest mule bucks

Monty had ever seen.

"He must have had 13 points on a side," he exaggerated after Joe joined him. "I took good aim, knowing he was going to collapse in a heap. But almost as soon as I fired I heard the bullet smack a tree and go whistling off somewhere."

What finally brought Joe was a fourth shot which Monty fired at a lone doe within easy range. Again, he had his sights right on her, fired, and expected her to drop. But almost like a TV rerun, she dashed away, and no amount of searching turned up proof of a hit.

When Joe arrived a few minutes later, Monty explained that he was convinced something was wrong with his sights. His earlier sighting-in had put the bullet about an inch high at 100 yards.

"Let's head back to the house," Monty suggested. "I have to zero this thing again."

"With all the shooting you were doing, I thought you were being overrun by deer and needed some help," Joe chuckled. "You think you're shooting where you're not aiming?"

"One or two of those may have missed anyway, but I'm sure my slug hit well above that big mule buck."

A session on the range near the ranchhouse proved Monty right. The bullet hole which appeared in the paper target was almost a foot high. Subsequent shots were consistently high, apparently due to a change in bullet lubricant, so a sight-alteration job was called for. Joe's brother, Wayne, corrected the fault, and a three-inch shot group in the bull followed. Monty and Joe were satisfied the next 60-yard opportunity would succeed.

Early Monday morning, the two hunters were back in business. In the crisp-but-calm twilight, they worked around a rambling wheat field, and hadn't gone half a mile when a sizable deer herd appeared, their bodies silhouetted against the slowly brightening eastern sky as they nibbled wheat. Still a distance away, the hunters huddled behind a field terrace and whispered plans. They decided to work around the field on the left, try ing to keep out of sight behind trees in the gullies, or below the terraces.

Midway in the stalk, about 30 wild turkeys erupted from the edge of the field like a covey of giant quail.

"Boy, that really snaps you awake in a hurry, doesn't it?" Joe whispered.

Pushing on toward the next gully, they slowed to look for the deer through openings. The herd was still there, at least most of it, and another wooded draw about 200 yards away might provide shots. They picked up the pace, stopping again behind the row of trees in the draw. To Monty's surprise, Joe raised his rifle, aimed into the draw, and fired. A mule doe dashed up out of the ravine, and the object of Joe's attentions, a forkhorn buck, bounded down the draw to the left.

"I don't know how I missed him," Joe half apologized and half complained. "I suppose I must have overshot him shooting downhill like that. I guess that spooked the rest of our deer."

It had. While Joe reloaded, poking powder and ball into his weapon, the pair discussed the next move. They decided to move south and work a ridge that was outside hearing range of the disturbance. Cutting across the wheat field, they were in fresh country within 30 minutes. About 200 or 300 yards apart, they started the slow, tedious trek east.

Both moved with a quiet that comes only from long hours of practice, pausing often to glass the terrain ahead. Monty had kidded his companion about his diminutive binoculars, saying they looked like a pair of fancy opera glasses. So, Joe kept them stuffed inside his jacket whenever possible, but defended them as practical enough in terrain where long-range scanning was seldom necessary.

About 10 a.m., after they had covered perhaps half a mile of good deer country, Monty's next chance came. As he eased onto a hogback from which he could check small ravines on each side, he spotted three deer on the next ridge. A quick glassing showed a buck and two does, but they were as interested in him as he was in them. As he lowered his glasses and brought his rifle to bear, the buck slipped down the bank and out of sight. Estimating the range at well over 100 yards, Monty held his shiny new front sight about four inches high, touched the trigger, and dropped the hammer onto the percussion cap.

As the noise died away, Monty watched the doe skip off the ridge and out of sight. Immediately he knew he had (Continued on page 55)

Using muzzle-loaders for big game requires archery stalking techniques, but still puts a big bang into those final moments

River Rat

Ed Hashberger may be a little older than most active sportsmen. But give him half a chance, and hell talk an arm and a leg off

PULL UP A STOOL, and Ed Hashberger will tell you about the time he shook hands with Teddy Roosevelt, or arrested a popular clergyman for shooting pintails in the spring. Or, if you get to know him better, hell tell you about his horse-and-buggy court ing days along the Platte River.

"You don't learn anything with your mouth open," he'll say, so lend an ear. You don't learn anything with your eyes closed either, so watch closely while he skins a coyote with surgical precision. He makes the familiar cuts with unencumbered ease that give no hint of his 90 years or failing eyesight.

"Back in 1925 when I was a game warden," he leads as a prelude to longer yarns, "there were only 16 of us in the entire state. Some mighty amusing things happened then.

"I remember once when I got a complaint about someone running a hoop net on the Loup River near Fullerton. Well, I found the net, sat in the bushes to wait for the owner to check it, and then arrested him when he came. I took him to town where the judge fined him $100 and costs. He wasn't sore, though. 'How come you arrested me?' he asked on the way back home. I told him about the complaint.

"Next week I went back, and there in exactly the same place was another net. I waited until morning when I picked up its owner. Well, it was the same guy who had filed the complaint on the fellow I had arrested the week before. In fact, they were neighbors. I asked him why he had turned in his neighbor and then put his own net out.

"Well, he told me he had been wanting to put his net under that big old Cottonwood log for six years. It was the best darn spot in the entire river, he said, but his neighbor always beat him to it. So, he had decided that the only way to get his chance was to turn the neighbor in. I arrested him, too, of course."

Ed's parents moved to the Platte Valley near Schuyler during the 1880's. Exposed to river life during youth, Ed never strayed far from the Platte he grew to know so well. During those years, hunting and trapping were not sports as we know them today —they meant meat on the table. One fall, Ed's father shipped 936 mallards and 1,200 prairie grouse, salted in kegs, to the Omaha market. Canvasbacks were not abundant and represented top table fare, but even mallards, which were in good supply, brought $7.50 a dozen. Shot purchased in 25 pound bags, powder bought in bulk, and a double-barrel muzzle loader provided his father with the tools necessary to supply his family with meat.

Honing his skinning blade to a razor-sharp edge, he continues trimming the pelt from the coyote and digs into his bag of old warden stories for the next yarn.

"One day a fellow stopped me on the street and asked me to investigate a section of land north of Fremont. Well, I went out there. The cornstalks were cut, raked, and windrowed. I couldn't see anything wrong."

"The next time I went out there I took along Everett (Pappy) Ling, the warden at Lincoln. We went to the same section and found ducks circling over a cut cornfield. Then we saw a head come up out of a cornstalk blind. Remember this was in spring. Well, I happened to be driving and the rule was that the driver stayed with the car while the other investigated. Pappy went out to the blind. I could see he was having trouble, so I went to help. Well, I looked the culprit over from top to bottom. He said there was nobody in the world who could take him in. He was a huge specimen, now that I look back on it. I kind of pulled in my neck and said, 'You're just about my size.' I told him he could either walk peacefully with me to the car or come along over my shoulder. Well, he took a swing at me, so I grabbed him by the arm and pinned him down with my elbow. I brought him out of the field, threw him in the car, and took him to court in Fremont. That was when I found out he was a respected clergyman in the community.

"I figured that was the end of it, but more was to come. A few weeks later, when I checked the area again, the decoys were set back out. I didn't know it then, but the clergyman had cabled a prize fighter from Idaho to come out.

"I went over and told them they were in the field at the wrong time of the year. The fighter had a sheepskin coat over his shoulders so when he jumped up it fell off. He told me I was in the wrong field (Continued on page 52)

the fish of Lewis Clark

Construction of a new reservoir generally means good fishing at first, then a drop. Now we know why

Excerpted from an address given at the Second Annual Central Students Wildlife Conclave, St. Paul, Minnesota, March 31, 1972.SINCE THE 1930s, construction of reservoirs in the United States has accelerated. At present, total surface area of reservoirs greater than 500 acres exceeds that of natural lakes in the contiguous 48 states, excluding the Great Lakes. The justification for building reservoirs generally falls into three categories; water supply, flood control and hydroelectric power. When reservoirs are constructed, fishermen expect fishing success in these waters to be at least comparable to that of natural lakes. Usually fishing in a new reservoir is excellent, at least for the first five or six years. Then success declines and, in many cases, eventually becomes poor.

The purpose of the National Reservoir Research Program of the U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife is to determine causes for fish population changes in reservoirs, and to suggest management measures to maintain good sport fishing in these waters. There are six main stem impoundments on the Missouri River: Fort Peck Reservoir in Montana, Garrison Reservoir or Lake Sakakawea in North Dakota, Lake Oahe in North and South Dakota, and Lakes Sharpe, Francis Case and Lewis and Clark in South Dakota. Fort Peck, the first reservoir constructed, was completed in 1940. The last reservoir completed was Lake Sharpe in 1964. Water elevations in the six-reservoir system reached full operational levels in the fall of 1967. The capacity of these reservoirs is 76 million acre-feet or three times the average annual flow of the Missouri River past Sioux City, Iowa. Garrison Reservior and Lake Oahe have the largest surface areas of any hydroelectric reservoirs in the United States. They are exceeded in volume only by Lakes Mead and Powell on Arizona's Colorado River.

20 NEBRASKAland FEBRUARY 1973 21

The purposes of the six main stem Missouri River reservoirs, which are a portion of the Pick-Sloan Plan for the economic development of the Missouri River Basin, are: flood control, hydroelectric power, irrigation, navigation and recreation. All are operated as a single system by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

The North Central Reservoir Investigations began studies on the South Dakota reservoirs in 1962. Fish, plankton and bottom fauna have been studied intensively, especially in Lewis and Clark Lake, the smallest and most downstream impoundment. The State of South Dakota studied the reservoir fish populations prior to 1962 and fish populations in Fort Peck and Garrison Reservoirs are being studied by the States of Montana and North Dakota, respectively.

The history of the fish populations in the six main stem reservoirs has been generally similar. In the first several years after impoundment, the fish population increases tremendously as all species present in the old river expand their numbers to occupy the waters created by the new reservoir. Trees, brush and grassland are flooded by rising waters and spawning conditions are excellent for most species. However, when the reservoir reaches full pool and water levels annually fluctuate over planned elevations, spawning conditions are no longer ideal for many species. Stable shorelines are established in many areas as silt is washed into the reservoir, leaving behind sand, gravel, rubble and boulder. Water levels no longer rise in the spring to flood the prairie grasses, but only rise and fall over an established shoreline. In some instances, water levels may actually decrease during spring and early summer because of the flood control function of these waters. Aquatic vegetation is scarce because of steep, sloping shorelines, fluctuating water levels and wave action caused by heavy winds common to the prairie. Protected areas adjacent to the reservoir accumulate silt from eroding hillsides. Because of the radical change in spawning conditions between the early years of impoundment and the later years we find a decrease in species numbers as well as overall fish abundance as the reservoir ages.

Fish population changes in Lewis and Clark Reservoir have been greater than in any of the other main stem impoundments. Systematic annual sampling of young-of-the-year fish during summer months was begun in 1965 using seines and bottom trawls. Annual sampling of adult fish was begun in the fall of 1966 using experimental gill nets and Lake Erie-type trap nets. Forty species of fish were sampled from this reservoir during the early years following impoundment. In 1971, 24 were collected and only 12 of these could be considered common. They were carp, river carpsucker, smallmouth buffalo, bigmouth buffalo, channel catfish, white bass, white crappie, sauger, walleye, freshwater drum, emerald shiner and gizzard shad. Fishes that could not adapt to a reservoir environment included mostly sunfishes and minnows.

Over the period of our studies we have observed changes in fish abundance, growth, reproduction and movement. Between 1966 and 1971, the estimated biomass (the amount of living matter in the form of one or more kinds of organisms (Continued on page 49)

HOMO SAPIENS, THE FORCE TO CHALLENGE NATURE, HAS DOOMED ITSELF

Man first? Man last? The paradox of human ecology

Scientist-ecologist Dr. litis is with the biology department of the University of Wisconsin, Madison

Reprinted by permission from BioScience, July 1970. 24THE UBIQUITOUS conservation speeches and environmental panels of today are dealing mainly with urgent problems of population, pollution and crowding. That the priorities are given to these big-city, strictly human, homocentric syndromes is obvious and understandable. People die of pollution, people go crazy with crowding, people starve and lay waste the lands through overpopulation.

Hopefully, we may yet solve the pollution crisis; we can, I think, clean up our polluted nests. But if, in cleaning up the cities, we forsake the rest of life, if we in our human preoccupation, let all but corn and cow slide into the abysmal finality of irreversible extinction, our species indeed will have committed ecological suicide.

NEBRASKAlandHowever, there is no cause for optimism in the broader environmental crisis, for the specters of ecosystem collapse, of catastrophic extinctions of most living animal species and of a vast number of plant species, are on the horizon.

Three percent of the world's mammals be came extinct in historic times, not counting such prehistoric wonders as the Irish Elk or the Mammoth, and most of them during the past 50 years! Today, 10 to 12 percent can be considered endangered, extrapolating from the conservative eight percent of species and subspecies listed as periled in the Red Data Book for Mammals of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, and perhaps 130 of the 400 United States mammal taxa (groups) are believed to be threatened with extinction. Birds are faring no better! S. Dillon Ripley of the Smithsonian Institution recently estimated that a majority of animal species will be extinct by the year 2000! And, Kenneth Boulding suggests that, with the present rate of human reproduction, in another generation, it may be economically impossible to maintain any animals, except domesticated ones, outside of zoos.

Butterfly and wild flower, mountain lion and caribou, blue whale and pelican, coral reef and prairie land —who shall speak for you? My grandchild may need to know you, to see and smell you, to hear and feel you, to be alive, bright and happy!

Yet among all the many programs of the recent "teach-ins" at the University of Michigan and at Northwestern University and 1,000 other campuses, few spoke for the wild environment, for nature, for a Morpho butterfly in a Peruvian valley, for a timber wolf chasing caribou in Alaska.

This lack of concern is understandable, because man now occupies every bit of the earth and like a dictator, controls, or thinks he could control, if he wished, every living thing. As some see it, except for a few primitive tribes, "Man has ...broken contact almost entirely with the ecological universe that existed before his culture developed. He no longer occupies ecological niches; he makes them."

But have our genes ceased to need the environment that shaped them? If we destroy ecosystems and species with abandon-ecosystems to which we are adapted, species whose values we do not yet know, and cannot predict - we surely do it at our own peril.

Thus, the lack of focus on the natural environment, on the wild animals and plants, on the woods and streams, is frightening.

Who defends wilderness, the natural unspoiled environment? Who defends the environment in which we evolved, and which we still need in all its purity? Who, except for a vociferous but ineffective minority?

The ultimate question one has to ask is this: Shall man come first, always first, at the expense of other life? And is this really first? In the short run, this may be expedient; in the long run, impossible.

Not untfl man places man second, or, to be more precise, not until man accepts his dependency on nature and puts himself in place as part of it, not until then does man put man first! This is the great paradox of human ecology. Not until man sees the light and submits gracefully and moderates the homocentric part of himself; not until man accepts the primacy of the beauty, diversity and integrity of nature and limits his domination and his numbers, placing equally great value on the preservation of the environment and on his own life, is there hope that man will survive.

If we are to usher in an age of ecologic reason, we must accept the certainty of a radical economic and political restructuring as well as ethical and cultural restructuring of society. No more expanding economics. No more expanding agricultures. No more expanding populations. No new unnecessary dams. No new superfluous industries. No new destructive subdivisions. We must stop and limit ourselves —now.

Let the archaic power structures of the tech nologically intoxicated cultures of the USA, USSR, Japan and others listen, and listen well to the winds of change: The earth and the web of life come first; man comes second; profits and progress come last. Man now is responsible for every wolf, as well as for every child, for prairie and ocean as well as for every field.

Henceforth the laws to govern man must be the laws of ecology, not the laws of self-destructive laissez-faire economics. And what the laws of ecology say is that we, we fancy apes, are forever related to, forever responsible for this clean air, for this green, flower-decked, and fragile earth.

Indeed, what ecology teaches us, what it implores us to learn, is that all things, living and dead, including man, are inter-related within the web of life. This must be the foundation of our new ethics. If you love your children, if you wish them to be happy, love your earth with tender care and pass it on to them diverse and beautiful, so that they, 10,000 years hence, may live in a universe still diverse and beautiful, and find joy and wonder in being alive. 12

Joslyn Art Museum

Dodge Street at 24th has become not just an Omaha landmark, but also a cultural mecca for every Nebraskan

WASHINGTON IRVING once called Nebraska the "Great American Desert," and a great number of his 19th Century contemporaries agreed. There was nothing here, they said, and they were sure the future held little change in store. How wrong they were, of course, as millions of families, fed up with eastern life, packed their wagons and headed west, many of them settling in Nebraska. The state began its evolution, spawning the diversity of city and farm. But there remains, in certain quarters, the opinion that the nation's midsection is still a wasteland, not so much from the population stand point as in the absence of culture. Such could hardly be further from the truth, and a case in point is Omaha's Joslyn Art Museum.

This two-block-long, marble structure neighboring Capitol Hill has be come a mecca for art lovers through out the Midwest. Built 41 years ago as a memorial to George A. Joslyn, a business leader in the area, the museum has become a focal point for cultural life in the community. Here, too, in the 1,200-seat Witherspoon Concert Hall, artistic endeavor comes to life through regularly scheduled concerts, lectures, movies and other presentations of works by world-renowned leaders in their respective fields. There is more to Joslyn Art Museum, however. There is an involvement between the patron and the artist that characterizes the total impact which the museum has had on the city and the state.

Standing and changing exhibits range from old to contemporary masters, providing something for almost every taste. Sculpture is a prominent part of Joslyn, and from time to time ethnic crafts and local artwork are included to hold the interest of even frequent visitors.

Unlike many museums, Joslyn does not stand idle. Nor is it necessarily a showcase of the distant past. Instead, it is a living testimony to refute the claims of the unknowing few who branded this land uncouth. Mere words cannot capture this museum. It takes a look inside, and those who enter are sure to discover a new and livelier in terest not only in the arts, but in Nebraska.

Queenie I led the parade that has entwined our lives

Four Feet Trotting Behind

THERE I STOOD, staring at an empty leash. Deserted again! Kipling and almost 40 years of married life had warned me not to give my heart to a dog. "Go by some other round —somewhere that does not carry the sound of four feet trotting behind."

I recall an eloquent senator who declared that the canine is the only unselfish comrade in a selfish world. Those little creatures are so full of the passionate joy of life, it is no small wonder their candles burn so brightly, and yet so briefly.

"No more dogs!" I tearfully told my husband. "I'll never get involved in this sort of thing again."

When Pixie died two years ago, she was the last of a long line of four-footed house guests to trot through our door and into our hearts since we were married in the 30s.

That was depression and crying time. We both worked that first year skipping a honey moon, saving to move from a dreary attic in Omaha. We wanted a house with a yard. We also wanted lots of babies.

When we found a small cottage to rent, we attended auctions in search of bargains with which to furnish it. People were selling every thing but their children to buy shoes with which to pound pavement looking for jobs.

Those years following the stock-market crash brought not only dust storms, drought and grasshoppers to Nebraska farmers, who saw corn drop from 67 to 29 cents a bushel and wheat from $1 to 27 cents, but they also cut the workweek to three or four days for city dwellers fortunate enough to punch a time clock.

At one outdoor sale, a beautiful and bright eyed, snow-breasted brindle terrier was held aloft by an auctioneer who chanted:

"Whatll ya give for this gen-u-wine pedigreed young female that's lost her papers but likes to sit on 'em. She don't read, but I'll betcha she can do everything else! Haw!"

My young husband and I, separated in the crowd, were so incensed by the public humiliation of the proud, well-bred animal, that we bid against each other to rescue her.

Queenie the First took us home, enthroned herself in our little house, and soon hovered graciously over our firstborn son as if he were her own heir apparent.

Then, 20 months later our blue heaven turned dull gray.

Queenie and I were both preparing for an imminent population explosion; the landlord sold our house; my husband, one of Ma Bell's Bell Telephone Company brood, was transferred outstate; and I moved in with my parents until our second son arrived and the three of us could take to the Sand Hills to join a lonely husband and father.

Two pregnant women in a crowded house was a bit much, so Queenie magnanimously renounced all claim to her domain and departed with dignity to live out her years with delighted friends.

It was a rare period for us —between dogs. But I quickly realized in the years ahead that not only Ma Bell tolled for us. Various and sundry dogs in numerous Nebraska towns beckoned us on.

The dogs we ushered in, time after time, were as different as house-guests: a few were interesting, intelligent and appreciative; many were lovable and full of humor. Some were impossible.

They arrived and departed, all sizes and colors with temperaments ranging from phlegmatic to emotionally uptight. Pups lugged home in eager children's arms left indelible impressions on rug and lawn. Those of quality stamped themselves irrevocably on our memories.

Queenie II was special with her sweet personality, the high value she placed on exclusive fellowship with children and her unusual debut timing.

The day I arrived home from the hospital with a new baby, I was greeted with wild enthusiasm by our three little boys, the eldest 51/2. My husband, who had taken his vacation to care for our sons, had moved into a larger house during my absence. I was overwhelmed by the greater-love-hath-no-man project he had accomplished for my coming-home surprise. But I was baffled and stung by his unprecipitated, door-slamming departure from our boisterous family reunion.

He was not a secretive person. Was he in a state of shock (Continued on page 46)

BENCH SHOOTING

One hole in the target after five rounds is the mark of a lousy shot Or is it?

FOR CENTURIES, firearms have been among man's most important tools. Too often a tool of war, guns were also a means of survival, and were as important for a time as the hoe or plow. More recently, they have become devices for sport and recreation.

Still of primary importance to hunters, the modern rifle also appeals to another type of shooter —the one who seeks accuracy on the target range. Almost since the first barrel was fashioned to bloop a heavy object in a predetermined direction, the quest for greater ac curacy has challenged firearm buffs.

For convenience and efficiency, many improvements in the basic equipment have been developed. Barrel steel, rifling, priming material, powder and bullets all have been, and still are, the subjects of experimentation and testing, both by manufacturers and thousands of shooters.

Military and commercial sporting arms were used by serious target shooters for many years, with modifications made on them to make them shoot better. Gradually, as standards rose, additional refinements were needed. Custom equipment began to appear, and as the ranks of target shooters grew, a few companies began turning out high quality rifles capable of extreme accuracy. International shooting matches helped speed such developments, and also did much to promote wider interest in the sport.

Still, that interest is not what many feel it should be. Dwight Thimgan of Lincoln is one of those, and he believes the lack of interest is due mainly to the way competition has been handled in the past.

"No one likes to enter any sort of contest knowing he hasn't a chance to win," he explains. "But, that has all been changed under the International Benchrest Shooters rules."

He says that all types of guns and all degrees of shooting skill are no longer pitted against each other. A relatively new organization, In ternational Benchrest Shooters has drawn up sensible guidelines to standardize and simplify regulations, scoring and all other aspects of target competition.

"The average hunter, say one equipped with a .243 with six-power scope, can go out and compete against other shooters on an equal basis. He is not going to end up in a match with some guy sporting a $2,000 rig with machine rests, a barrel capable of putting every round through the same hole and a 30-power target scope. But, even such a sophisticated piece of shooting machinery should be able to find competition from other, similar experimental rifles. This can only happen with an organized shooting program —so we need interested people.

"What is really impressive about the IBS program is that taking up serious target shooting requires little expenditure, at least for most people. The average hunter already has a suitable rifle, scope and probably reloading equip ment. A little more care is required in reloading to make each round precise for target work, but the extra effort comes naturally as a person gets more involved."

Handloading is adopted by most bench shooters and many hunters because they can load charges more accurately than factory production lines and develope loads that perform best in their particular rifles. The arms and ammunition industry is also interested in accuracy, and match grade bullets are manufactured for those who need them.

Dwight, an insurance man, became interested in benchrest shooting only three years ago, but now he is an avid enthusiast. He is convinced many other people in the state would also take up the sport if they knew how it is set up, and if adequate facilities were available.

"Unfortunately, there are just not enough ranges in the state. Hunters have no place to sight in rifles, and there is no range adequate to hold registered competition."

The nearest ranges for sanctioned matches are in Illinois and Texas, he explains.

"I don't know, but I would venture to guess Nebraska has more rifle owners and shooters per capita than any other state. Yet there are only a handful of ranges; none of them set up to handle an official shoot. Grand Island has a good setup, and there are others in Lincoln, Plattsmouth, Broken Bow, Scottsbluff, Alliance, and maybe one or two more, but even state troopers and other police officers in the state don't really have suitable ranges.

"The National Guard has a target range at Ashland, but it isn't readily available, and doesn't have the proper equipment for competition."

He explains that a moving paper backing strip is used to record the number of shots fired at each target during a meet. This is especially important in (Continued on page 56)

Almanac Pike

For many, winter is a time to pack away angling gear and wait for spring. But for others, frigid months offer a challenge that would try the patience of even stoic summer fishermen

WINTERTIME is fishing time for Ralph Fleishmann and Norm Henggeler, but such was not always the case. Not too many years ago, Ralph and Norm felt winter was an endless drag between fall and spring when fishermen did nothing more than swap lies and dream about the day the ice would go out. Their opinion of winter was shared by most anglers in southeastern Nebraska.

But things have changed, and to a large degree, the Salt Valley Lakes have brought the shift. Constructed primarily for flood control, the 13 impoundments around Lincoln have opened more than 4,000 acres of fishing water. While the open-water angling value of these lakes was recognized immediately, the ice fishing potential was discovered only in recent years.

Although both Ralph and Norm were experienced anglers, they quickly recognized that ice fishing is another sport requiring different equipment and other techniques. There are many types of open-water fishing, but Ralph and Norm put ice fishing into two basic categories -jigging and tip-up fishing. Jigging is most commonly used for panfish, and the techniques and equipment are fairly simple. Any rod can be used, but a short jigging rod is most convenient and is equipped with light monofilament line and small hooks. In most cases, a single split shot is sufficient weight.

Ralph considers wax worms the best bluegill bait. Other effective baits include small minnows, worms and grubs. Small jigging lures and "ice flies" are occasionally used together with bait.

Mobility is the key to success in panfishing. The old ice spud has been replaced by the ice auger, which makes hole drilling a simple chore. Anglers should move around and try different depths until they score. Where they find one fish there will likely be more.

All the Salt Valley Lakes contain panfish, and ice fishermen have taken good catches from almost all of them. The west end of Branched Oak Lake was a hotspot for large bluegill during the 1971-72 winter. Pawnee Lake also produced many small bluegill and crappie as well as walleye. Fishermen also took some large crappie through the ice at Bluestem Lake near Martell.

While Ralph and Norm still do some jigging, they have turned to tip-up fishing with northern pike their

38 NEBRASKAland FEBRUARY 1973

target. Their interest in pike is not unusual, for they are favorites with many ice anglers. In fact, pike have long captured the interest of man. In early days they were known as Luce, the waterwolf, and early naturalists believed they were bred from water weeds and hatched by the sun's heat. In medieval literature the pike attacks swans, men and even mules. The heart of a pike was thought to abate fevers, the powdered jawbone to cure pleurisy, and the ashes of burned pike were used to dress wounds.

"Pike fishing with tip-ups is a waiting game," Norm explains. "Once you've selected a spot and set up your gear you're committed to stay awhile. You've got too much equipment to move around."

There are many types of tip-ups, but all are designed to serve the same purpose —to hold the baited line with a spool of reserve and to signal a bite the instant it occurs. Depending on design, the tip-up may have the spool of reserve line located above or below the water. Like most pike fishermen, Norm and Ralph prefer the underwater spools. These function even if the hole freezes over. Above-water spools are often preferred by walleye and sauger fishermen who feel they can be more sensitively adjusted for these light biters.

Tip-ups are commonly equipped with 40-pound-test or heavier nylon line. Fishermen after northern pike use steel leaders, hooks to match the size of the bait they are using and only enough weight to take the bait down. "Once we got our augers and tip-ups we thought we were in business," Ralph recalls, "but every time out we find something else we need."

Their gear now includes an ice spud for chipping out frozen-in tip-ups, a long-handled ice skimmer, a gaff and an electronic fish locator for checking water depths. They also carry a tarp which can be erected as a windbreak, a small heater, thermos jugs and other miscellaneous equipment. All the equipment (Continued on page 53)

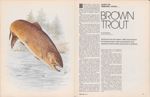

NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA... BROWN TROUT

Introduced into the state in 1889, these elusive fish tolerate higher water temperatures and depleted streams better than brook or rainbows

BROWN TROUT, Salmo trutta, are not native to North America. They were first introduced in 1883 when 80,000 eggs were shipped by ocean liner from Germany to New York State. Brown trout were first stocked in Nebraska waters in 1889.

Several years later a subspecies, Loch Leven trout, were shipped from Scotland. From then on, the two strains interbred until it became impossible to distinguish between them. Now they are classified as one species —brown trout.

Brown trout have been called many names. A few of the friendlier ones are brownie, Loch, Loch Leven, Von Behr and German brown. In fact, during World War I, a group of patriots attempted, without success, to change the name from German brown trout to 'liberty trout."

The brown trout has a wide range of color variations. Usually the dorsal area is green- to olive-brown. The sides are lighter, and the belly region is white to brilliant gold or yellow. The sides are usually bespeckled with black or red spots while the tail usually has none.

Brown trout spawn in fall, usually in the upper reaches of streams where gravel is abundant and clean. Here, a saucer-shaped nest is fanned out and eggs deposited in the bottom of the depression. They are then fertilized by the male, and covered with gravel by the female. The number of eggs deposited varies with the size of the fish. There may be as few as 200 or as many as 6,000.

The incubation period varies with water temperature. Generally, the eggs hatch in about 50 days in 50-degree water. A newly hatched fish is called a sac-fry because of the large yoke sac attached to its belly. These young fish remain buried in the gravel until this sac is absorbed, a process which takes several weeks. When the sac is completely absorbed, the fish emerge from the gravel and feed on their own.

Growth rates vary with the amount and type of food available. Food ranges from fish to insects and from worms to crustaceans. A second factor which influences growth is habitat. Brown trout inhabiting lakes and large rivers grow faster than others living in small streams.

Of the three trout species stocked in Nebraska streams (brown, brook and rainbow), the brown trout adapted best. It can withstand slightly higher water temperatures, is more tolerant of depleted stream environments and reproduces more readily. It also adjusts its feeding habits to what is available better than other trout.

For years, rearing brown trout in hatcheries has been a problem. Hatchery mortality, which is more severe with brown trout than with other trout, is the result of wariness, cannibalism, variable growth rates and disease. However, with the improvement of hatchery techniques these problems are decreasing.

Angling for this species can be both rewarding and frustrating. Although the brown trout will take a variety of baits and lures, it is one of the most difficult trout to catch. After it is hooked, it does not jump like the rainbow. It dives deep and tries to tangle the line around a rock or tree root.

The Snake River presently holds the honor of having produced the largest brown trout in the state. This was a 12-pound, three-ounce whopper taken in 1971. Although most brown trout caught in Nebraska weigh less than two pounds, the ability to outwit these crafty creatures is most rewarding. Catching a brook or rainbow trout is considered fun and sport, but catching a good-sized brown is an achievement.

FEBRUARY 1973 43

Try this old Scandinavian cooking style, and watch your dinner guests come back for seconds until everything is finished

HOW TO: Boil Fish

PEOPLE have been around for a long time, and fish even longer. It would, therefore, be logical to assume that every conceivable method of preparing the flesh of the latter to please the palate of the former is common knowledge.

Such is not the case. Drying, smoking and other primitive methods of preserving fish and meat were born of the lack of refrigeration. These are still popular because they produce tasty meat. Yet, the other old-fashioned methods are not generally known. Take, for example, the simple technique of boiling fish. This has recently started to become popular, although the method has been around for more than 100 years. Granted, boiling a fish sounds about as appetizing as the old Hun technique of inserting meat between horse and saddle, then eating it after several weeks.

But, even though it doesn't sound too great, boiled fish is delicious. The taste varies somewhat with species, butcoho salmon and trout, for example, closely resemble lobster in taste when so prepared. Impossible you say? Try it and see. Even people who normally avoid fish line up for seconds and thirds when big trout are boiled. Just remember, you owe it to yourself to try this recipe at least once.

The fish boil is believed to have originated in Scandinavian communities around Lake Michigan. Only recently, though, because of tourists, has appreciation for the taste and ceremony become widespread.

Performed outdoors, the fish boil is similar to lobster and clam bakes which take place along the Atlantic coast. Preparation is probably simpler, but proper timing is all important.

A pot large enough to accommodate enough potatoes, onions and fish for the dinner is the main item. Inside this pot goes a perforated metal basket. Although amounts vary, a basic recipe would include, for four pounds of fish steaks or filets: five quarts of water, one cup of salt, six medium potatoes and six onions.

Bring water and salt to a boil. In the meantime, cut both ends off each potato, but do not peel them. When the water is boiling, drop in the potatoes and onions, cap with a vented lid and bring back to a boil. Cook for 18 to 20 minutes.

Then, slip the fish into the basket and boil for another 12 minutes. Cook longer only if the fish does not flake when tested with a fork.

Drain the water immediately, top the potatoes with melted butter and have more melted butter on hand to dip the fish. Coleslaw, pickles, lemon slices, garlic or black bread and a thirst quencher complete the menu. Your guests won't quit eating until they finish everything.

When done outdoors, the ceremony includes, after cooking is complete, tossing a small amount of gas or other fuel onto the fire. This causes a violent reaction. The pot boils over. Scum drains away and the fire goes out. This ritual, however, is not recommended when preparing the dinner indoors, for you may have more firemen as guests than you can provide food for. Or, at best, you will be cleaning up while others eat.

During the cooking, a few parsley flakes can be added for flavor. The basic procedure can be tried with any kind of fish, but white-meat fish are traditional. This method produces tender, tasty flesh which holds together without much crumbling. Old hands prefer cooking double the required number of potatoes, then preparing the leftovers as American fries the next day.

FOUR FEET

(Continued from page 35)and disappointment that I had presented him with a daughter? Perhaps he had counted on a baseball team.

I should have known better. He threw his cap through the door first when he returned, pulled a tiny replica of Queenie I from under his jacket and gently laid her in my lap beside the baby.

The eyes of three small boys —and one large one who had never had a dog when he was young —were upon me.

We were between dogs for the moment, but this was ridiculous!

My head went back, my mouth formed a howl, then closed. The picture of an auction back in Omaha wouldn't go away, so Queenie II took over.

She was the vigilant, beloved nanny of the neighborhood until she met a violent death beneath the wheels of a truck before she was three.

Next came the 40s —Pearl Harbor, bond selling, land armies sowing victory gardens, ration-stamp books, war casualty headlines; it was crying time again.

We didn't need Scamp, but we thought he needed us. From him, we learned that degradation and fear, experienced early, builds a protective armor of distrust that rarely can be pierced.

Abandoned by a family that couldn't cope with its own problem —chronic alcoholism—Scamp moved in as a freeloader who sneered at us, snarled at the minister and snapped at policemen. He repulsed all friendly overtures, sulking or stalking about arrogantly, trying to camouflage his own self-hate. When he went too far and bit the hand thatfed him — mine —he was banished. He served a purpose as a horrible example, but we never repeated that mistake. Mike was something else.

A large, handsome, limpid-eyed springer spaniel, Mike's magnificent obsession was us. He dominated with over-protective fer vor. When the master was away (for weeks at a stretch) repairing telephone lines or cable, Mike barely touched his food. He slept fitfully on the front steps, firmly discouraging friend or foe from advancing to ward the children or me.

Woe to anyone who raised his hand outside his home to discipline unruly offspring. Mike always wedged himself between

Mike didn't have a mean bone in his body or a vicious thought in his leonine head. But he was big, and timorous friends and neighbors were not in rapport with Mike's soul as we were.

Our guardian's anxiety syndrome became apparent. His coat lost its sheen; he was thin and out of condition. He refused to leave his sentry post except to sternly nudge toddlers away from the danger of street traffic.

He also refused to make the local scene with other virile four-foot-loose bachelors. He was just too worn and tense from his self-imposed duty to enjoy a night out with the town's shaggy-haired playboys.

We had problems. Friends weren't speak ing to us. The neighborhood was full of spoiled kids who ran to Mike for succor and who rated fathers as "bad guys". We were harboring a displaced, frustrated, country houseguest whose responsibilities were worrying him sick.

He should have been racing the wind, splashing in a pasture pond, or flushing pheasant and quail from chaparral.

A rancher friend, who had coveted Mike for some time, invited him to come and live on his acres of running, hunting space. It required two strong men and a rope to get Mike into the pickup. It took all of the neighborhood mothers to restrain a dozen children —and me —from going along.

The ranch was more than 150 miles away. Still, there was Mike, scratching at our door a week later, cockle-burred and bushed, a chewed-off rope dangling from his collar.

Our pathetic refugee, fleeing from "what was best for him," and his small, frantic pals, milked that tragicomic episode for all it was worth. But back he went, and we never saw him again.

We heard of his eventual adjustment, his prowess as retriever par excellence, and our battered hearts rejoiced. We had had it, however. Where was our perspective? What was wrong with us that we allowed house-guests to usurp our home and disrupt our lives?

With Pixie, our third brindle bulldog, we came full circle. She was our last tail-wagging guest who came to dinner and stayed for 10 years. She saw our youngest child through what might otherwise have been a lonely boyhood. His four-year navy hitch spent aboard a submarine-tender was brightened by one anticipation. (The burden falls heavy on mothers who are reminded through years of servicemen's memos: "Don't let anything happen to my dog, Mom, till I get home.") And, she saw him, with his older brothers and sister, marry and scatter across the country.

My husband and I were back where we started —together without children, with out dogs, without trauma. Ours was an orderly, tranquil year, a crashing bore until a hat tossed under the Christmas tree was followed by the sound of four-feet trotting behind.

where to go...

Toadstool

Park

[image]

Circle tour.

THERE ARE those who consider glorifying the life and times of William F. (Buffalo Bill) Cody somewhat a farce. Cody was, they point out, given to exaggeration, unreliable, a miserable man ager of money, and a heavy drinker. But, those slurs aside, one fact remains crystal clear—Buffalo Bill became a legend in his own time. That legend remains vivid even today, a century after the plainsman, scout, hunter, In dian fighter and showman reached the peak of his career.

Outstanding among the stories of Buffalo Bill Cody is the one about his meeting with Yellow Hand at what is now called War Bonnet Battlefield some 23 miles northwest of Crawford on the Oglala National Grasslands. It is said that Cody and Yellow Hand rode full into each other, exchanged rifle shots, both ending up on foot. Accounts vary, but the upshot is the same. Buffalo Bill Cody killed and scalped a young Cheyenne chief named Yellow Hand, furthering a reputation that was to spiral in the years to come. There are those who say there is no truth whatever in the accounts popularly circulated, and they may be right. Cody, however, relied on the incident to enliven his show business venture on stages throughout the world, and whether it was true or not, the enact ment Buffalo Bill produced kept adoring audiences coming back.