Ice Fishing Issue

NEBRASKAland

January 1973 50 cents 1CD 08615 Special 10-Page Section on Hard Water Angling Hunting with a Camera Late-Season Ducks

Speak Up

NEBRASKAland Magazine invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to Speak Up. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters. — Editor.

NICE, BUT-"In your September 1972 issue, the article Four Feet and a Cold Nose by Jon Farrar stirred me to write. First, I want to say that I was very impressed with the layout of the article. It was done with great taste and beautiful pictures. I note that in most all of the national sporting magazines that I have read in the past few years, there seems to be some definite lack of interest in writing stories or articles regarding the English Setter. It seems that every hunter in the country either uses pointers or some other breed. Evidently, Mr. Farrar has begun to believe all of these stories about pointers and other dogs and has come to the conclusion that the English Setter should now be grouped with the Gordon Setter and Irish Setter as an almost non-existent field dog.

"I would like to point out that in my past experience, the English Setter is still one of the greatest upland game dogs in the country. It may be well to state at this time that out of the 24 Grand National Grouse Championship Field Trial dogs, pointers have taken 11 titles and English Setters have taken 13. I have seen many dogs in the field and at home and never have I found a dog that would be so anxious to hunt, retrieve, play, lay by a fireplace and treat children as gently as a kitten as the English Setter does.

"If these articles continue referring to the English Setter as a 'bench dog', ignoring him in the field and hunting magazines, I am sure that it will not be too long before all the bench people start feeling that the JANUARY 1973 dog really is better for the bench than it is for the field. Please let us give the English Setter a chance to remain in the field where he belongs and works so well." —Lloyd J. Dowding, Omaha.

PUBLIC SHOULD KNOW- It is with keen interest and appreciation that I observed your television promotion for preservation of wetlands. We are falling rapidly behind in promoting and asking public awareness for just those things that make our wetlands a cherished heritage that should be preserved. They have never been presented to the public in this manner, and we should continue to promote the values of wetlands. The abundance of shorebirds and waterfowl in a good marshland is beyond comprehension; and we should bring this to the attention of our youth.

"There is much work to be done in eradicating rough fish from our larger lakes and marshlands —and I don't mean reservoirs. This would double the waterfowl population in the Sand Hills area and improve shooting along the tributaries bordering the lakes area." —Spud Kapustka, Chairman, Citizens For Wetlands, Elyria.

MULTI-SUBJECT-"The article, The Cedars Are Coming, (May 1972) is extremely well written and so true. The statement: 'They have come, they have conquered, they claimed the land it is theirs' is true. The cedars have taken half of the pastureland in Jefferson and Gage Counties, and are taking the other half faster than the bankers and loan companies did in the 1930s. There is no grass under the cedar trees, so what are the cattle expected to eat?

"Since the lawmakers put high-powered rifles in the hands of 16-year-olds, they try to cover up their mistake by telling us we must wear 400 square inches of hunter orange material which a deer can see for two miles. Now don't try to tell me deer are color blind, because I don't believe it. "I hope those city people who gripe about feedlot pollution end up eating imported kangaroo meat. I think half of the cattle feeders will get disgusted and quit, making a real shortage of meat. I would rather see feed lots waste going down the rivers to the sea (since God made rivers for that purpose) than to have my neighbors dump it on the fields where it can soak down to our drinking water."—Archie Anderson, Odell.

BENCH VS. FIELD-"ln Jon Farrar's article Four Feet and a Cold Nose, he states that certain breeds have lost their hunting characteristics by being bred by 'bench-competition fanciers.'

"The breed standards used by so-called bench-competition fanciers are designed for maintenance and improvement of the dogs, not to lessen or destroy the natural instincts of the particular breeds. Just as 'beautiful but dumb' does not apply to all pretty girls, it also does not apply to all good conformationed dogs. In fact, the better body construction should improve the ability of dogs to move well and there fore their hunting ability. Having parents of field background, or 'good hunters' does not insure that the offspring will be good hunters, nor does bench champion parentage insure a champion in the show rings.

"The two springers pictured in Mr. Farrar's article are of bench breeding, and although not used or trained for hunting, they still show their natural instincts when taken to the field. It is a wrong conception for hunters to think that you can destroy a natural instinct by improving the body structure of any breed. This natural instinct will always be there." —Mrs. E. B. Roche, Lincoln.

NEVER AGAIN-"I have been a hunter for several years, but no more! Now, every year about this time, I get a sick feeling in the pit of my stomach, for it is at this time the slaughter of wild animals begins.

"In your July 1972 issue (Speak Up), there was a letter from an 'irate sportsman' who complained coyote hunting from the air was unsportsmanlike, but claimed using a rabbit-squeal call was. I don't see the difference in slaughtering an animal driven to you by fear and noise, and one driven by hunger. Indeed, I question that killing a wild animal is sportsmanlike! It is distressing to see an 'intelligent, civilized' man take up a high-powered rifle or shotgun to fight his own inadequacies by killing an irreplaceable resource. It might be more in vogue to just mail your favorite game a bomb letter.

"A hunter often tries to justify his 'sport' by saying that bag limits are set, and he is helping to control the animal population in an area. I would point out that there are plenty of under-populated areas left, and populations could easily be controlled by transplanting the overflow. Contrary to popular belief, wanton slaughter by man can only be an upsetting influence on the 'balance of nature' (a phrase with which the hunter often shoots himself down).

"Hunters point out that license fees go for conservation. How utterly inconsistent! Why not just contribute to conservation? Why ruin that which your fees are trying desperately to save?

"In the book African Genesis by Robert Ardrey, evidence is presented that man is a descendant of a race of killer apes. Haven't come very far, have we? No, I don't have much respect for the man with the bigger, more powerful gun; the he-man who uses his brains and technology to eradicate less fortunate species. If a man must prove that he is, indeed, a he-man, let him grab a duck from the air with his bare hands, let him run down a deer in the open field, let him wrestle a bear to the death. Then he might have, just might have, proved himself to be superior, if he is so unsure of his own abilities.

"In closing, let me ask hunters what their reactions would be if we ever encountered a superior species (a not altogether impossible situation) who decided that to control the population and prevent overcrowding- for our own (Continued on page 6)

SPEAK UP

(Continued from page 3)good —would declare open season on man for a Sunday afternoon sport? 'Remember, boys, the young ones are the most tender, but the old bucks make fine trophies for your wall.'

"In the age of ecology, hunting is no longer a tenable 'sport'. The man who wishes to eat wild meat should raise two of the species; slaughter one and release the other. " — Dr. J. G. Spangler, Rochester, Minnesota.

HELP! —"The Nebraska legislative session of 1921-22 approved two bills, one creating a state park board and another setting aside a section of school land in Dawes County as a state park. The state park, of course, is Chadron.

"Initially, the park board was part of the Department of Public Works. The next session of the legislature, however, placed the board under the Department of Horticulture at the University of Nebraska.

"From 1923 until 1929 the board remained there. In 1929 the Nebraska Game, Forestation and Parks Commission was created by the legislature.

"No reports can be found of the actions of the park board from 1923 to 1929. All attempts to locate them have failed. The board was required to provide an annual report but these cannot be found.

"We would like to know if any individual has a copy of any of the annual reports for these years that we might duplicate for our records. -Robert N. Killen, Chief, His torical Parks.

POETRY —"Enclosed is a poem my aunt wrote. It brings sharp memories of times of haying down on the meadow, the ice-covered, winding slough, the wonder of waving, smooth wheat fields, white-faced cattle peacefully grazing along the Platte River '-Miss Luella Potter, Colorado Springs, Colorado.

NEBRASKA Lora Bostwick, Oshkosh Land of prairies and wide valleys Of meadows and low hills Of rivers and slow streams Of lakes and sloughs and rills. growing corn and wheat and hay And cattle on the plains With trees and flowers and growing things And sun and wind and rains. A state that's filled with birds and game A place to hunt and fish for all Where winter's cold and summer's heat Fade into spring and fall. Where sunrise in the morning Gives each day a fresh new start And the sunset is so lovely That its beauty fills your heart.for the record

Curbing the vandal

When a vandal tears down a fence, drives across a greening field or plows through a farmer's back yard, he is branded for what he is —a vandal. But when a road sign is peppered with buckshot, a barn falls victim to a load or two of No. 6s or livestock is maimed or killed by a rifle bullet, the person responsible is tagged as a hunter. None of these incidents are unknown, and each is, in fact, becoming more and more common. But the terminology is wrong. A man who thoughtlessly destroys another's property is not a hunter. He is a criminal, pure and simple; he is a vandal with a gun.

As the state agency most closely associated with sportsmen and hunting, the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission annually receives hundreds of complaints from landowners who have had bad experiences with "hunters". In most cases, there is little that can be done about the situation. Seldom is there anyone to testify to what happened, and the person responsible for the incident is long gone. And so the situation stands. Farmers face a problem with those who would violate their property, and the Game and Parks Commission is virtually powerless to act.

There may be a new angle to this old problem, however. There just may be a way to curb this trouble afield through proper legislation. In the months to come, a method by which the inconsiderate, even dangerous, minority can be removed from the sport will be studied, evaluated and proposed for action. Through such legislation, the Commission would be empowered to suspend the hunting privileges of those convicted of misdeeds afield. Here, in a nutshell, is how the system would work.

First, the regulations of other states would be studied to determine if there is a precedent for such a law, and if so, how it has worked for others. Second, there would be a provision for licensing every person who ventures afield with a firearm, regardless of what species is being hunted. The permit would be a token issue, but would serve as a control measure of those in Nebraska's outdoors. Then, a comprehensive record-keeping system would be initiated to provide information on offenders. This would closely resemble the informational banks presently employed in motor vehicle code offenses. And, the cooperation of other states would be sought in an effort to exchange information on known or potentially habitual violators.

The present system of fines would surely be retained for some of the less-serious violations. But now, such a system is little more than a slap on the wrist, and is frequently discounted by the "hardened" game of fender. Augmenting the fine system would be the provision under which the courts could revoke or suspend the permit held by those brought before them. Length of the suspension would vary with severity of the violation. Such a system is now simply conjecture, but it may soon become reality. And it just might be the answer to the continuing problem of how to remove the potentially dangerous, always-disturbing vandal with a gun from Nebraska's hunting lands.

Heritage of Honor

Fort Robinson: Part II

IN THE MID-1870s, Nebraska's Pine Ridge was a festering sore, threatening to burst and send its poison coursing throughout the West. Repeated incidents contributed to mounting pressure amongst both Indians and whites, and at the Red Cloud Indian Agency on the White River, it was felt that the only safe way to handle the situation was to call in the army. So, in 1874, Camp Robinson appeared on Nebraska's plains —a deterrent, or so it seemed, to open hostility on either side. But that goal was long in becoming reality.

By late 1874, Camp Robinson's tent quarters had been replaced, for the most part, with permanent buildings, and it became evident that the army was in the Pine Ridge to stay. Still there were problems. The Indians knew that military opinion was divided sharply on the issue of the Great Peace Plan of 1868, and frequently approached the soldiers with complaints of how Indian Agent Saville handled matters at the Red Cloud Agency. Sympathy for their point of view was evident as indicated by one anonymous officer's comments that the Indian agent and others like him were determined to civilize the Indians whether they were willing to be civilized or not. That might have been good church practice, he said, but it was very impractical. The Indians should have been left alone at their agency, he continued, rather than being forced into hostilities by accepting civilization and a religion they neither wanted nor understood.

Hunting was the only way of life the nomadic Sioux and many of their neighbors had ever known. Yet the Indian agents felt they should forsake their heritage to become farmers. Another officer was quoted: "...it is not easy to see how they are to become farmers when they have no good farming land to work —' Perhaps such feelings and statements were contributions to Saville's undoing, for an investigation was launched into his actions. And, although he was exonerated, he was removed from his post and replaced by J. S. Hastings.

The slender wire separating peace and war had been walked many times at Camp Robinson, yet all-out hostilities had been avoided. In the not-too-distant future, though, that wire was to be snapped. It was George Armstrong Custer who would at least indirectly bear the responsibility. In 1874, the Custer Expedition stumbled onto gold in the Black Hills of Dakota Territory, and word spread like wildfire. The Black Hills, however, were sacred to the Indian; off limits to the whites. Nonetheless, the trickle of prospectors into the area soon became a raging torrent. The Indians protested. Either the army find some way to keep the whites off their land, or they would. Assuming that meant bloodshed, Uncle Sam fell back on his old remedy for such problems. He would buy the Black Hills-never mind that they weren't for sale. And once again Manifest Destiny steered onto a collision course with Indian heritage.

On September 17, 1875, the first negotiations were slated for the council room at Red Cloud Agency. The Indians refused to attend. Give or take, bicker and barter, the meeting was moved to a spot eight miles east of Camp Robinson, a (Continued on page 63)

Cold-country Caravan

Snow is common bond for snowmobiling clan

FLITTING ACROSS new-fallen snow like tiny flying carpets, more than 20 gleaming snowmobiles were patterned against the expanse of the rolling Sand Hills in north-central Nebraska. Trailmaster Herb Newman eased back on the throttle and his machine glided to a stop. Tugging at the bill of his red cap, he squinted into a bright January sun while the other riders darted effortlessly across the hills.

Unlike most trail rides the rancher heads up, horses had been replaced by snow mobiles for this particular excursion. A gregarious fellow with boundless love for the outdoors, Herb had designed his mid-January excursion to cover the 17 miles between Stuart and his ranch.

"Most folks don't think of a snowmobile as a cross-country transportation vehicle," Herb countered a remark concerning the distance to be traveled. "The ride will take only an hour or so, and will cover some mighty beautiful country."

Herb knew only a few of the other riders. Most had responded to invitations carried by area newspapers and radio stations and they hailed from surrounding towns. Some, though, were on hand from as far away as Lincoln, Omaha, and Wahoo.

"Watch this!" the voice echoed from deep inside a blazing-yellow, nylon suit. Seconds later a screaming machine shot full tilt over a large embankment. "Kerthump." The jump was perfect, and rounds of cheers exploded from (Continued on page 52)

Snaggers endure winter's harshest to reap paddlefish limits at Gavin's Point

Trebled Waters

LIKE SOME preposterous fraud perpetrated on nature, the slate-gray form rolled to the Missouri River's surface. To the uninitiated it would have been a worthy puzzle to piece together —a long spatulate bill, shark-like tail, and an absence of bones in the body were all keys to the solution. To a veteran fisherman like Willie Kubicek of Shelby, it was no surprise; in fact he had driven 125 miles hoping that's what he would find on the other end of his 40-pound-test line.

Snagging was the means and paddlefish were the objectives. A rugged pastime plied by the hardiest of outdoorsmen, snagging demands the utmost of its participants. There is no room for those of frail constitution.

12It was midweek between Christmas and New Year's, and Willie, along with fishing cronies Lee Glatter, LaVern Boss and his son Mike, were pursuing a favorite midwinter activity. The location was the stilling basin below Gavin's Point Dam in northeast Nebraska. The weather was miserable, the fishing good.

Willie finally urged the 15-pounder close to the houseboat and unceremoniously hoisted him aboard without benefit of gaff or net. The large treble hook, with three ounces of lead molded in the center, had sunk solidly into the tail muscles and there was little chance of losing the fish.

It was the snaggers' second try for the long snouted fish since the season opener October 1. NEBRASKAland The previous week everyone had taken their limit of two apiece, but Willie had copped all honors by hauling in a 72-pounder. Large as that paddle fish was, it was still shy by 15 pounds of the state record taken the April before near DeSoto Bend.

By seven that morning the foursome had been busy breaking the houseboat free from ice that locked it securely in its berth. A two-hour drive had preceded their arrival, which meant a 5 a.m. departure time and a 4 a.m. reveille. It was a typical routine for the anglers, characteristic of their dedication to the sport.

Temperatures in the teens, cloudy skies and a potent northwest wind had welcomed them to the state's north border. It would be less than JANUARY 1973 balmy on the open water.

By nine the houseboat was navigable. Like most, it was a homemade affair. They had built the craft in Shelby back in 1964, completely disassembled it and hauled it piece by piece to Gavin's where they reassembled it. Perhaps no showpiece, she was a practical and reliable old gal.

Easing the craft toward the dam's base, Lee, the craft's navigator, cook and keeper of the ship's log, lowered the 150-pound tractor flywheel that served as anchor.

Like a well-organized assault force, the anglers readied equipment, each suiting his own styles and theories. Willie used a two-hook system -a number 6/0 or 7/0 treble hook with a three

13

ounce lead center at the end of his line, and an other treble hook about two feet higher. The second hook was held parallel by a couple of wraps of line around the shank. Some of the others used only one weighted hook and others varied the distance between the two hooks. Like all fish ermen, each had his own "perfect" rig.

Pool-cue-like rods about four feet long with heavy, salt-water casting reels were the universal choice and monofilament line of 40 to 50-pound test was the rule.

Snagging can be a sport of frustrations at times. The first hour was like that. Snags were common on the rough bottom and leaden hooks were lost by the dozens. The agony of tying and retying hooks on cold, wet lines in a raw, cutting wind was a task accomplished with much difficulty and little joy. Pauses were frequent to free the eyelets of ice that built in concentric layers as dripping line was retrieved.

Action was in short supply that first hour or hour and a half. Lee's rolling pot of homemade chili and Vern's pan of prune cake sliced in over sized portions were big attractions. When the fish weren't in, the fishermen were —in the cabin eat ing, that is. It may have taken a stranger a while to determine just why anyone would go to all that trouble. Was it fish or food? Boiling hot water was dumped into an old tub every now and then, and each rubber-booted fisherman took turns warm ing his feet in the home-designed thawer.

Another houseboat was in the area, and several small, open boats were working nearby. As a rule, the fishermen in the open boats didn't last long, though. The wind and chilling temperatures were too much to contend with without a cabin to retreat into. Nobody seemed to be hitting spoonies, each fisherman passed the slack with his own amusements. Lee dragged out a water-stained old notebook that served as the craft's log and reminder of other days. Lee amused not only him self, but the rest of the crew as well with the humorous entries in the book.

"Here's one from May 29, 1961. It sounds like that was a better day than we're having so far," Lee rambled, thumbing through the battered book.

"Many snags. Lots of lost hooks and sinkers, probably 100 pounds of lead. Fished overnight and filled two coolers with fish. Caught three yellow cats, 16, 12 and 9 pounds, probably 100 pounds of crappie and the rest big sauger and small catfish."

Jabs at one another's fishing ability and some good old fisherman kibitzing constituted the bulk of the entries. May 1 7, 1961 was a good example.

"Willie snags 'til he's blue in the face, sleeps awhile then goes back at it. I picked up his pole and on the third jerk hit a 23-pound yellow. I gave the pole back to him and let him play it 'cause I'm all tired out from all the big fish I've been catching. Willie's mad, throws out and gets an 18 pounder. Has the nerve to say it doesn't take any brains to hook a catfish. Good bunch of eaters but no cooks."

An ecstatic whoop from 14-year-old Mike Boss initiated mass evacuation of the cabin and announced the youngster's first spoonbill.

"Keep the line taut," Vern coached. "If the line slacks up he may throw the hook, and that's no way to begin a snagging career."

Mike heard plenty of advice as he reared back on the rod, took up (Continued on page 52)

the case for Winter Cover

Spring is the time to consider the cold-season habitat which may mean life or death for wildlife

MANY NEBRASKANS enduring another winter realize their comfort is proportionate to the degree of the previous season's preparation. This is particularly evident to self-sufficient farmers whose crops were raised and stored, livestock fattened and butchered and surpluses sold to provide cash for things the land did not produce. Farm business in winter is mostly a matter of waiting and of planning spring and summer tasks to make the next winter as comfortable as possible. Preparations for winter start with the growing season; some as annual tasks, others as permanent, long-range developments. At least one of the latter, a farmstead windbreak, requires years of development to become effective.

People who are most comfortable today and best prepared for tomorrow may well be concerned for other, less-fortunate beings. It is well, then, for them to consider how wildlife could survive really rough winters. The most logical answer is that animals native to this area have adapted to recurring conditions. Those that did not adapt perished long ago, since winter weather is a critical test for survival. Winter is a hold-over period when wild creatures use various methods to carry on until reproduction time in spring. Amongst those species which are now successful, individual members compete for limited living facilities, a contest which dictates the survival of the fittest. The result is a base of hardy parents producing offspring likely to persevere.

Only the best-protected pheasants will survive the roughest winters. In milder winters, marginal habitat will (Continued on page 53)

FOCUS ON WILDLIFE

JACK, THAT cheapie lens isn't much better than a coke bottle, one of NEBRASKAland's photographers belched for the 374th time that week. "And as for your claim about being able to photograph a good assortment of wildlife in a few days, I'll just say that you've been sitting behind that desk too long. Besides, all your wildlife photos come from city parks. Hunted game animals just aren't that easy to locate, much less to photo graph."

Before I knew it, I found myself aboard a gear-laden yellow van, heading west with our art director Jack Curran. After two years with the magazine, such assignments had lost their luster for me. Threats and challenges over coffee too frequently end up as story ideas, and my main task was to see that Jack played according to rules —stayed out of city parks and zoos —and to record his trials and tribulations.

Jack would be using two reflex cameras, a twin-lens Mamiya and a single-lens Pentax. The 35mm Pentax boasted 50 millimeter normal, 135mm optical and 500mm mirror lenses. Telephoto extenders which fit between camera and lens could double the magnification of each. The most power he would have was 1000mm or 20 power.

Big game or small, intrepid photographers seek them

out in their favorite habitat. Goal of expedition is to

capture critters on film, but many of shots are misses

Big game or small, intrepid photographers seek them

out in their favorite habitat. Goal of expedition is to

capture critters on film, but many of shots are misses

The Mamiya used 120, 21/4x21/4 film, a larger format than 35mm, and came with normal, 180mm and 250mm lenses, the latter roughly 4-power magnification.

I was using a Pentax with 200mm, 300mm and 500mm lenses, the last roughly 10 power. Although Jack had twice the power of my 500mm, he would lose some quality. Photos taken with extenders are usually a bit mushy. Jack, though, felt doubling the magnification and recording a larger image on film would yield photos equal to those shot on a lens half the power and enlarged to the same size.

Loaded to the roof with camera gear, camping equipment and chow we headed for Monroe and the Loup River. Whitetailed deer, the most wary and unphotographed big-game species in the state, would be our first quarry.

By the time we opened innumerable gates and swept around a shrinking slough, it was late afternoon. I dropped Jack at a tree stand between the Loup's floodplain forest and a maturing corn field. An elliptical plot of plowed land would have sunlight until late, so if the deer behaved normally and crossed it to feed, Jack should have some action.

I walked deeper into the timber and climbed into another stand. Light there wouldn't last as long as where Jack was, but deer in the timber would start mov ing earlier. In theory we had the area covered.

Rowdy, feeding blue jays were Jack's only companions for an hour or so. He hung his gunstock-mounted Pentax with the 500mm mirror lens on a branch and nestled down, his twin-lens around his neck. Tree stands aren't super comfortable, but in a pinch they'll do for a nap.

Rustling leaves snapped Jack to at tention as a doe stepped into a small, grassy (Continued on page 55)

The Great Urban Escape

The hustle and bustle of city life has placed a pox on all our houses. There are, though, oases of calm amidst the furor

GONE FOR AN ever-increasing number of people are six-day work weeks; 12-hour days are things of the past. And, on the not-too-distant horizon lies the siren of the working class —the four-day work week —promising a whole new spectrum of leisure time.

But time can become a curse, too. Idle hours trail into boredom with little or nothing to do. Hobbies and home projects now fill many such voids, yet there are only so many cars to repair, basements to modernize and lawns to mow, so listlessness becomes an epidemic.

There are many cures for such disease, however. Virtually every city boasts a number of parks. Wilderness areas are constantly set aside to provide respite from the doldrums of life amidst the concrete canyons. Noon hours provide time for picnic lunches in lush parks only a stone's throw away from towering office buildings. Wildlife sanctuaries lie in the shadow of the city and are no more remote than the neighborhood shopping center. Verdant golf courses sprawl through city hearts, providing exercise and relaxation for an ever-expanding cult of devotees. Prospects for city dwellers' leisure time are almost boundless, and in many respects enrich their lives.

The great urban escape goes on, and in an age of personal, cultural and ecological awareness, it will surely continue. Where else can places with power to lift the spirit and calm the troubled soul be found so easily?

24 NEBRASKAland JANUARY 1973 25

Forlorn call of wild goose

or majestic silhouette of a bull elk,

the lure of the great outdoors

beckons harried urbanites from little

more than a minute or a mile

Forlorn call of wild goose

or majestic silhouette of a bull elk,

the lure of the great outdoors

beckons harried urbanites from little

more than a minute or a mile

A guide to ICE FISHING in Nebraska

TWO basic methods of ice fishing are popular in Nebraska —hand lines and tip-ups — probably because they are the simplest and can be used for taking any kind of fish that hits here during the winter. Generally, both types of fishing produce best around dawn until mid-morning and again from late afternoon to sundown. Keep in mind, though, that fish become sluggish during the winter and move around less than in the summer. So, the more holes you cut and try, the better your chances of locating them.

GearTO GEAR UP, you'll need a three- to five-foot rod. A limber rod is usually preferred for panfish and trout while a stiff rod will allow firmer setting of the hook for pike and wall eye. When ice fishing, regulations permit no more than five hooks per line or a total of 15 hooks. Double or treble hooks are counted as one hook.

If you're going after big fish, a good free-running reel, instead of the usual line-winding cleat, is a must. It will permit you to play the fish better. Also, when used without a bobber, this reel will let you change your fishing depth with the twist of a finger. Some fishermen substitute for the bobber by curling part of the line around a finger to get the message when they have a bite. Anglers who don't care for reels keep their excess line from freezing and out of the way by winding it around two L screws, placed about 12 inches apart on the wooden handles.

Choice in the strength of line also varies, with not over four-pound-test recommended for best action on bluegill, other panfish and trout. Some sportsmen, angling specifically for pike, prefer lines as tough as eight- to 20-pound-test. Using too heavy a line is perhaps the most frequent mistake of unsuccessful fishermen. Occasionally, fish break a lighter line, but with some finesse you can land most of them, and you will certainly have more bites. Ice fishermen are almost unanimous in their choice of transparent monofilament line.

When it comes to the bobber, the smaller the better, as long as it's big enough to stay afloat. Fish generally don't bite as eagerly as during the summer. Therefore, the float buoyance and the lure weight should be balanced so the slightest nibble will sink the bobber and offer minimum resistance to the fish. If the float is too buoyant, fish often spit out the bait. Assuming that you've picked the right baits and hooks, the strategy in hand-line fishing is pretty simple. Just bob or jig your line with a short up-and-down motion to at tract fish to your bait. Stop every few minutes. This will let you feel a bite and give fish a better crack at your offerings.

Shelters

Shelters

SHANTIES are welcome on raw, windy days. If you don't own one, there are several fairly simple and inexpensive rigs you can make for protection from the elements. One is the familiar lean-to, which is generally made like an Indian tepee with three round poles about six feet long and 116 inches in diameter. Tack canvas or other windbreaking material to them. Spikes at each end of the poles can be driven into the ice to hold the lean-to in place.

Another portable windbreak can easily be made by hinging a pair of two- by four-foot sheets of quarter-inch plywood together. The whole thing folds flat. By adding runners, it can double as a sled. Place one- by two-inch horizontal braces slightly below the middle and at the bottom of each sheet. Each should have four de-headed nails driven in vertically, so they will slip through positioned holes in two triangular boards to serve as a portable seat and floor. When not in use, the seat and floor are stored inside the two folded sheets. Remember, though, that shelters taken onto the ice must be removed when you leave.

ALL OTHER PLANS and preparations-no matter how well laid out —can go for naught unless the fisherman dresses for the weather. The important thing is not the amount, but the choice of clothing. Instead of wearing heavy, bulky garments, slip into several thin layers of loose clothing which will let you adjust to the weather. On some sunny days, you may get too warm and need to peel off a few of the cold-weather duds.

Your feet are the most important things to keep warm. Many ice fishermen rate insulated, waterproof boots as No. 1. Felt liners worn inside rubbers are good. With them, wear one pair of light socks and a pair of medium-heavy wool socks. Your feet will also stay warm if you put on a pair of light wool socks under and over wool slip pers and top this off with four-buckle arctics.

Some type of windbreaker is a must as an outer garment. Parkas are strong favorites because of the hood. What goes underneath can vary. One good combination includes thermal underwear, wool shirt and pants and insulated coveralls. For the hands, wear plastic gloves to keep dry. If you don't, be sure to carry a spare pair of gloves or mittens. For some reason, the first pair always seems to get wet. Hand warmers are high on many fishermen's lists, as are gas lanterns and small burners (oil and charcoal). One final item for many anglers is a vacuum bottle of hot coffee. But now, it's time to actually get to where the fish are.

BEFORE you test any of these techniques, there is the job of making a hole in the ice. Many veteran ice fishermen swear by the Swedish type auger, especially when the ice is 12 or more inches thick. Others stick with their trusty spuds, conventional augers or drills. Whatever tool you pick, keep it sharp. Otherwise you may be too tuckered out to enjoy fishing by the time your hole is cut.

With a spud, attach a rope to the handle and wrap the loose end around your arm or wrist so you won't lose it on that final jab through the ice. In chopping or spudding the hole, taper it like an inverted funnel. Many a big fish has been lost because the hole was too small at the bottom. Remember, too, that a hole with sharp or jagged edges may cut your line. Too large a hole could later endanger a life, so an eight- to 10-inch diameter is enough.

It's a real nuisance when ice keeps forming in your fishing hole. To avoid this problem, add a small amount of common salt, glycerin or vegetable oil to the water. When the weather isn't too cold, some anglers sprinkle graphite powder on the water to keep it free of ice. Also, you can build a small mound of snow around the windward side of the hole and use a small skimmer to scoop away slush from time to time. To prevent snow from filling holes, take a small cardboard box and tear off the top and one side. Then place it over the hole, bottom up, so your line is protected from the three worst sides and from above. The one open side will let you watch the bobber for action.

For even better protection against freezing wind and drifting snow, you can use a box enclosed on all sides except the bottom. On the top, punch a very small hole and run a light line through it with the bobber set to float in the water. Outside the box, this line is extended some 30 feet and another bobber is attached to it so you know when there is a bite. As ?. smart bit of strategy when angling for perch and walleye in very shallow water, place snow or a cover over the hole to hide the light which often spooks the fish.

There are several ways to lick the problem of freezing bait. Place minnows in a styrofoam bucket which has been painted black to absorb the sun's rays, or keep them under the ice in a perforated can which allows water to flow through. You can also tuck bait inside your clothing where it will stay warm. Still another way is to pack snow around the minnow bucket as insulation.

SledsWHEN it comes to lugging your gear, a five-gallon bucket or old wooden box are handy. Use a gas lantern inside the bucket for heat. With the box, add a piece of wood to cover half of the open side, leaving enough room to get at the gear stashed inside. Cut a small notch on the top of the box for poles to stick through and tack on a piece of foam rubber to make sitting more comfortable.

Sleds and cut-off skis are often rigged with boxes, so they double as seats and for carrying gear. Usually a gas lantern is placed inside the box and lit for warmth. Going a step further, you can convert a toboggan into a combination equipment carrier and windbreak. This is done by fixing a long box on the toboggan with a hinged topside. Pins are placed on the top of the box and the bottom of the toboggan. These hold the top com pletely open when the toboggan is tipped on its side to form the other part of the windbreak. A regular pop case can be carried in the box and used as a seat and container for fish.

Bluegill

Bluegill

OVERALL, you'll find bluegill in the same areas during winter as in summer-over weedy mud flats and at inlets and outlets. Early in the ice season, fish near the bottom at depths from 10 to 20 feet, generally late in the afternoon. Jig your line about once a minute. Every few minutes, raise your rod about four feet and let the bait settle again. If nothing happens in 20 to 30 minutes, make another hole 10 feet or more from where you've been fishing.

After a month of ice and snow cover, bluegill may start swimming higher off the bottom and they become increasingly sensitive about biting. Your success may then depend on locating the fish at lesser depths and going to smaller lures and a lighter monofilament line. For a good combination, try a small ice fly, a teardrop or a small flasher blade with a grub or wiggler on it. Grubs sold by bait vendors are usually mousies, wax worms or corn borers. They are all good. Since winter blue gill lures are all weighted, extra shot is seldom necessary.

Northern PikeFAVORITE winter haunts for northern pike are along dropoffs in or near weed beds and brush shelters in water from three to 12 feet deep. Pike seem particularly susceptible to large minnows four to five inches long, fished from one to four feet off the bottom. Late in the season, it sometimes pays to offer one bait at this depth and another about four feet under the ice. Try the same bait depths as for walleye.

Pike are fierce fighters, so use a strong line (up to 20-pound-test) and a wire or heavy gut leader. The leader should be weighted with two No. 4 split shots and should feature a large treble hook (1/0 or 2/0). When pike grab bait, they usually make a run, rest, and then run again. As soon as they start the second run, set the hook with a solid jerk and then pull the line in rapidly, hand over hand. Take the hook out of the landed fish with a pair of pliers or be prepared for tooth acerations!

ICE FISHING tackle for bluegill and perch serves nicely for most trout. As in panfishing, a limber rod is used to lessen the chance of breaking the line or tearing the hook from the fish. The line should be monofilament of about two-pound test. Lures are as variable as the angler, but here again there is quite an overlap with panfishing. Trout will hit on most natural baits —corn borers, wigglers, minnows, crayfish or salmon eggs. Often, these baits are more effective when used with bright ice flies, small spoons or spinner attractors in sizes eight to 12. They should be offered within six feet of the bottom.

Trout don't generally congregate, so you'll have to move around to find them. While they can be found in shallow water at times, they may range to depths of 30 feet. When fishing over shallow water, stay well back from the hole and move as little as possible, or you'll scare the fish away. Bob the bait a lot in the water, but let it rest for a few seconds. Although trout are attracted by the movement, they usually don't take the bait until it is almost motionless. If you don't get a bite in 15 minutes, move on and make a new hole. One last word about trout fishing—it's most productive just after the ice forms, but slackens progressively through the season.

PerchLOOK FOR PERCH in the same haunts favored I by bluegill. Halfway through the winter, they | are generally found in the deeper pockets of ^™ deep lakes during mid-day and closer to shoals early in the morning or evening. Generally, they stay from six inches to two feet off the bottom. If the barometer is dropping, go all the way down with your bait. Sometimes, you have to move it four to six feet off the bottom to get action. Probably the best hookups for perch are Russian spoons baited with perch eyes or minnows, a plain hook baited with a wiggler, or one of the numerous commercially made ice spoons with a grub on the hook.

Perch move in schools, so you should catch them hard and fast when you locate them, for they may soon move on. Plain brass and silver spoons may also be used with other baits already men tioned for bluegill, since they work equally well on perch. Other good bets are mousies, flicker spinners, French spinners, red yarn or even a shiny bare hook. As an added action-getter, place a swivel about three feet above the end of your main four- to six-pound-test line and attach a drop line to it. Next, put a rather heavy sinker about eight inches above a No. 6 or 8 hook on the main line. Do the same to the drop line and you'll have doubled your chances for success.

WalleyeWALLEYE locations are the same as those for perch. Here again, jigging is effective using a six- to eight-pound-test line. Russian spoons, Swedish pimples and Rapala spoons baited with minnows are good examples of proven jigging combinations. It's a good practice to let your baited spoon hit the lake bottom to disturb the sand or mud, thus attracting fish attention.

With larger fish, such as walleye, tip-ups come into play. These devices, equipped with reels and flags, are cheap to buy or easy to make. Most of those on the market are made to fold for easy handling. There's no big trick to operating tip-ups. They are merely baited and set out. When a fish bites, the flag flies up and the fun begins. The rest is up to the fisherman, and he goes to it by giving his line a solid jerk, setting the hook, then pulling in the line rapidly, hand over hand. When the fish is near the hole, it's time to play it carefully. Haste loses many catches at this point, when an angler tries to get a fish onto the ice before it's ready. Be prepared for surges and let the line slip through your fingers, but always keep some ten sion. As you may have guessed, tip-ups are especially nice for use in colder weather when it's hard to stand guard over fishing holes for a long time. Once they are set, fishermen can retire to a warm shanty and wait for the action.

The best places for walleye are over reefs and near the edges of shoals where the water is 15 to 30 feet deep. For bait, take a two- to three-inch minnow and hook it just behind the dorsal fin so it will be free to swim. The livelier the bait the better. Use light tackle, about a six-pound test leader and small hooks. Dusk hours or cloudy days are usually best.

Tread Safely

Tread Safely

THE CLOSEST some people ever want to get to ice is arm's length in the bottom of a cocktail glass, while others wade around on it regularly during the coldest part of the winter in the routine of chasing fish, game or fun.

Each of these may be an extreme, but most people are exposed to icy conditions at least occasionally, and it is the infrequently exposed folks who most need cautioning. There are, after all, inherent dangers connected with any extremely cold environment, for there is the possibility of freezing, and or falling through ice.

Winter activity is actually increasing nationally, with growing interest in such sports as skiing and snowmobiling. Weather conditions can change rapidly during winter, so extra precautions must be taken to avoid discomfort and possibly death.

Common sense usually insures survival, but there are times when even this rare human attribute cannot cope with the conditions at hand. Anticipating all possibilities may not be possible, but at least the most likely situations can be guarded against.

Pain and peril are ever present in our hectic life, but they are compounded or multiplied in frigid weather when simple exposure to the elements can spell death. Each winter, persons are stranded by blizzards; fall through ice and drown or subsequently freeze because of damp clothing; are injured and unable to reach shelter; or suffer heart attacks through over-exertion.

Each person must evaluate his capabilities and limit his activities accordingly. Carrying ample clothing in the field in the event of a mishap could prevent freezing if you are forced to stay out overnight. Venturing out alone should be avoided if at all possible, for if one person is injured, there should be another to go for help.

Anyone driving in winter should carry an emergency kit in the car. In cluded should be basic first-aid supplies, a blanket or two, some food stuffs, canned heat, matches, gloves and a flashlight. Such things as a compass, a few tools, a knife or hatchet and a shovel are also recommended. Being stranded for a day or two in a car is bad enough even with such provisions, but being without them could spell disaster. Snow would provide drinking water, but shoes and belts are not very palatable, even to the very hungry.

Another potential hazard encountered in winter is weak ice which claims a sizable toll of unwary victims each year. Hunters, fishermen, trappers, skaters and any other people who venture out onto ice should be able to recognize bad spots and be able to extricate themselves if they do fall through. It is always advisable to carry a long, solid stick when crossing ice. It can be used to distribute weight over a wide area and give a gripping point to pull yourself back out if you are alone. In a river, the current poses the worst problem, pulling a person under unbroken ice. Panic and shock may come immediately, but the victim must either try to reach the original hole or make another one downstream.

Thickness and quality of ice are difficult to determine, but solid ice usually has a blue cast while weak ice tends to be whitish. An individual should not traverse less than three, preferably four inches of good ice. A group needs six inches of solid ice unless well separated. If, while walking on ice, a series of cracks and snaps sound out, lie down immediately and work back wards. This may not look very sophisticated, but it should keep you from going through for a cold bath. The long stick is also welcome at this point, keeping your weight distributed over a wide area. A stick is also a nice handle for other people to pull you out of the drink if that mishap occurs. It is frustrating if you drop through the ice and then someone has to go looking for a pole.

A fairly common torment of winter, although varying in severity, is frost bite. This scourge creeps up slowly, creating more numbness than pain. The ears, nose, fingers and toes are first affected. In extremely cold weather, measures should be taken to protect against freezing. Exposed areas of the skin should be warmed frequently to maintain feeling in them and to keep blood circulating. Any rubbing should be light to prevent further damage to already injured tissue, and it is best to agitate the hands or feet to force blood into them. Extended exposure can mean permanent damage.

Mild winter weather can be exhilarating and refreshing, yet a pleasant outing could suddenly change into a struggle for survival. Then a few precautions could be critical-making the difference between mere discomfort and death.

Your Game Commission in Color

Something more than just a state agency, the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission is people and their purpose is serving you

TELLING the story of the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission in the pages allotted here could be likened to engraving the entire Old Testament on the point of a pin. There is just too much to say and too little space in which to say it. That then, is the premise under which we present the accompanying photographs. Each represents an area of responsibility within the commission's structure. All individuals shown are affiliated with the agency and are among some 350 full-time employees who serve the public throughout the state.

We have taken this opportunity to give you a glimpse of the commission as something of an introduction. As with any first meeting, you probably wouldn't remember the names even if we gave them now, but remember the faces because you will be seeing more of them in NEBRASKAland articles on what these people do for you on a day-to-day basis. That's when we'll supply the names, and that's when you'll remember them.

40

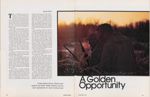

A Golden Opportunity

A late season bonus, liberal point system and North Platte brothers are the main ingredients for duck hunting finale

TAKE A SEASON that runs into January, add 250,000 over wintering ducks and three brothers who I ive to hunt water fowl, and you've got the formula for some of the hottest cold-season shoot ing in North America. Such were the elements that had provided the basis for many a late-season duck hunt for Duane, Larry and Tom Golden of North Platte.

Ever since the late-season experimental trial of 1969-70, hunters west of U.S. Highway 83 have had the opportunity to tack on a few extra days in the blind and harvest some of the surplus mallards overwintering on the Platte River and other open water in western Nebraska. The 1971-72 season was designed with the same goals in mind, but with bigger limits.

Working for the railroad had its advantages. The brothers' days off fell in midweek when the fields were usually devoid of other hunters. Strange as it seems, though, those circumstances were working against the trio.

"Look at 'em drop in over on the South Platte," Larry observed. "Must be sitting right on the ice or sandbars; the river's all slushed up."

"If it were a weekend, hunters on the river would be keeping the mallards up and milling," Duane added, "and we'd be right in the thick of things. That's the advantage of hunting the point; when river hunters get things moving, the ducks start looking for a more secluded spot to dabble their webs."

The "point" was the marshland peninsula at the confluence of the North and South Platte rivers. Just out side of North Platte's city limits and right next door to the municipal airport, this tundra-like hunk of real estate is a waterfowler's mecca. Low, marshy and webbed with surface and subsurface flowing water, the point is choked with willows and rushes. Spring-fed streams and pools remain open and inviting to waterfowl even when the river is carrying a heavy load of slush and small ponds and lakes are locked tight in ice. Add a high wind to these conditions to move ducks off the large reservoirs, and the protected point waters are irresistible to even the most discerning of water fowl.

But prevailing weather conditions weren't at all like that. The sky was clear and temperatures were expected to climb into the upper 40s or lower 50s. The day before, when the trio had moved in to chop decoys free from the ice, mallards were milling over the point even at midday. Many had decoyed even though the spread was dimpled with ax-swinging hunters. A day earlier the brothers had braved the raw winds long enough to douse 13 drake mallards in several hours, but this hunt showed no indications of being like that.

"Here are four right on us," Tom whispered, then whistled Cocoa, his two-year-old Chesapeake Bay retriever, into the blind.

A chorus of calls drifted sweetly through the frosty morning, and the drake and three female companions swung for another look. The drake's hoarse inquiry elicited a series of gurgling chuckles from the blind. A third swing brought the foursome over the decoys and Tom's Winchester 21, bored for skeet, dropped the green head cleanly. The hens winged off down the North Platte in search of more accommodating companions.

Cocoa's eyes had followed each

swing the mallards had made, but

she remained motionless until the

shot signaled her release. Then water

exploded in icy spray as she spread

eagled into the thawing pond. For a

48

NEBRASKAland

JANUARY 1973

49

Normally the brothers let the birds set wing and begin their drop, but these ducks were spooky. Others before them had responded to the call, circling closer and closer with each pass only to flare off. They would have to take these on the first pass if they were within good range.

"With that bright sun they pick up our movement a long ways off and are just twice as bushy," Duane observed. "This makeshift blind doesn't help any either."

The Goldehs usually hunted from their blind on the river near Sutherland, but for two weeks they had been using a friend's setup on the point. Closer to home, it permitted longer days and less traveling. A permanent blind was only a hundred yards away and was a comfortable affair, but ducks had been showing signs of favoring the wide, pool-like water. In short order, they had thrown together on the edge of the pool a temporary blind of (Continued on page 62)

COLD-COUNTRY CARAVAN

(Continued from page 11)the others. Circling around and out of the valley, Nebraska's Secretary of State Allen Beerman lifted his goggies.

"That was terrific!" Herb shouted.

"Perfect jump!" Hoppy chimed in. Hoppy, more formally Lloyd Hopkins of Wahoo's Hellstar Manufacturing Corporation, had loaned Beerman one of his firm's guttiest rigs, and the machine's performance capabilities were obvious.

"Sure," Herb explained to those within earshot. "Like just about anything, snowmobiles can be darned nuisances, and can cause lots of damage when they are not used sensibly. But, when driven within design limitations, they become great recreational vehicles and offer reliable transportation in heavy snow."

Hoppy ended the conversation, though as he sped by, hurling a challenge to race to the next mile fence. "You're on," Herb returned as he wrenched open the throttle of his rig's German-built engine and disappeared over the horizon.

In theory, the snowmobile can be traced to the 1920s and the work of a Canadian, Joseph Armand Bombardier, whose first vehicle was a sled steered by skis and pushed by an airplanepropeller. A number of other efforts were documented before the machines were finally perfected for commercial marketing in 1959. By 1962, an estimated 300 snowmobiles were in private hands. Then, in 1965 the figure jumped to over 25,000. In 1971, more than one million snowmobiles were in use in North America's snow country, and some 50 manufacturers currently produce variations on Bombardier's basic theme.

Meanwhile, Hoppy thundered across the finish line to win.

"Wait 'till I get you on my private track," was his opponent's only comment.

"You know," Herb reflected on the frequent bad-mouthing his sport takes, "snowmobiles are sorta like guns. In most hands they are really quite harmless; just plain fun plus being ideal for many domestic uses. But, there are those who will misuse them, taking them where they shouldn't, or chasing down deer or other wildlife. Incidentally, those are usually the same people who hit fences and destroy private property."

Standing on the runners of his snowmobile, Herb motioned for the other riders to follow. The entourage was about two miles from Newman's Niobrara-Valley ranch, and Herb was concerned that some vehicles might run out of gas.

The tips of the tallest prairie grasses protruded from the four-to-six-inch snow cover. But, careful examination of the snowmobile tracks revealed that the vehicles dropped through only a few inches of top snow.

"That's because of the wide tracks and the machines' built-in buoyancy," Beer man commented. "It may sound funny, but snowmobiles actually have a built-in float factor similar to that of a boat. Otherwise, they would fall right through really deep snow."

A few minutes later the group was circled on Herb's front lawn. Altogether the original group consisted of 22 snowmobiles, about 7 support groups in pickups or cars with trailers and a spattering of super-enthusastic youngsters had joined the party.

"Anybody hungry?" Herb hollered.

An overwhelming "Yeah" was his an ticipated answer.

"Come on in, I've got a pot of chili brewing," he finished, leading the bundled-up drivers into the house.

At first glance, a stranger might decide that all the heavy coats, mittens, scarfs, caps, hats and earmuffs in Nebraska were right there in Herb's house. It seemed as though everyone who shuffled through the door doffed at least a dozen coats, and that was just a start.

"Warmth is a necessity," Hoppy mused. "Nothing is worse than riding a snowmobile and freezing at the same time. That takes away all of the fun, and you can really get in trouble. When it's cold, that's okay. But when you start churning along at 30 to 40 miles per hour, the increased wind chill can get to you fast if you're not properly dressed."

The group was back outside where Herb introduced those he knew, and the others presented themselves, consumating the camaraderie of those bonded together by a strong interest in a specialized sport. Herb explained the racetrack, which was laid out about a mile east of his ranch house. Oval in shape and marked by up right rubber tires, the course wound through the hilly pastureland bordering the Niobrara River.

While Herb buzzed around the center of the track giving all of the children rides, his son, Butch, guided the racers over the circuit. And then, the racing was underway as machines shot around the 21/2 mile track at speeds ranging far beyond normal cross country fare.

"A lot of these drivers will learn a lot today," Newman offered. "And a lot of what they'll learn will be the basics of snowmobiling."

It was 3 in the afternoon when riders began disappearing. One or two at a time, they loaded up and headed for home. By 4:30, only a few minutes of sunlight remained, and the last of the snowmobilers called it quits for the day, heading back to the ranchhouse.

"I don't race a lot," Herb noted, "but, who am I to frown on it. Man has raced everything from horses to airplanes, so I guess it's only human to expect one snow mobiler to challenge another."

As the last riders hauled their machines out of the driveway, Herb stood on the porch of his home waving hearty good byes, and it's doubtful if any of them over heard when he mumbled to himself: "If there's one thing I like on a sunny Sunday in January, it's a good snowmobile ride. 12

TREBLED WATERS

(Continued from page 15)the slack and then repeated the whole procedure over and over again.

"Doesn't look like too big a one from the way he's bending the rod," Willie observed as he made ready the gaff just in case he might have misjudged the fish.

"Feels like all the fish I want to handle," the youngster replied. "It's plenty big enough for me."

The battle seesawed back and forth for only five or 10 minutes but for a 14-year-old, new to the sport, it seemed like it lasted for hours. The emotional but binding need for a boy to prove his worth on the first fish must have weighed heavily.

Waving off any assistance, Mike hoisted the 12-pounder over the rail, even though it was hooked precariously in the bellowing pouch of skin below the mouth. The moment was all Mike's, and to a family of snaggers it was just as monumental as a lad's first pheasant or deer is to a hunting family.

Other boats in the basin began hitting spoonies with regularity, and the Shelby crew spread out around the cabin and began the pulsating rhythm of the rod. Spoonbills finally had moved in and the excite ment of the excursion grew.

Paddlefish behavior is just as puzzling as its appearance and heritage at times. Just why these fish seem to move in and out of the stilling basin en masse, even though they are not a school fish, remains a mystery. Some believe they are following the cycling water currents that carry microscopic organisms on which they feed. Allan Carson, northeast Nebraska fisheries biologist engaged in spoonbill research, disagrees with that theory.

"The paddlefish definitely moves in and out of the basin as a unit, but I don't think that feeding habits can be attributed as the cause. These paddlefish, while not even in the catfish family, feed very little over the winter, much the same as the flathead and channel catfish," he suggests. "This is part of what we hope to discover with a study we initiated in the fall of 1971. Once common on the Mississippi drainage, from Minnesota south to the gulf, the paddlefish's range is dwindling. It is most abundant below the large dams on the Missouri River now. We hope to determine just what its current status is and something about its life cycle. Perhaps we are overharvesting a resource. If that's true, we hope to find ways to remedy it," he added.

An archaic fish that goes back in a direct line through millions of years of evolution to the Age of Reptiles, the spoonbill is the single representative of its ancient family in North America. Its closest relative in habits the Yangtse River in China where it attains weights of over 200 pounds. Though fearsome in appearance, it is a mild creature with a spatulate bill, small eyes, an enormous mouth and pliable, flapping gill covers. The rostrum, or bill, seems to have evolved as an organ for housing sensory devices that detect plankton swarms which are strained from the water as the fish swims slowly back and forth with mouth agape. It may also serve as a stabilizer and scoop when the fish swims and feeds on the bottom.

The spoonbill is a fairly rapid-growing fish. Those two or three-pounders were probably two or three years old. By the time they are five years old, many have attained a length of three feet or more.

Unlike any other fish in the state, the paddlefish does not have any bones in the body —its only bones are found in its head. Biologists have been aging paddlefish by cross-sectioning the jaw bones and counting the concentric layers of calcium formed annually in much the same fashion as the growth rings on trees. For a backbone, spoonbills have a cartilaginous tube running the full length of the body from brain into tail. A fiuid-filled notochord lies inside this tube and houses most of the nervous system.

The basin seemed suddenly packed with thestrange creatures, and snagging onto one became more frequent.

Lee knew, when his pole came to an abrupt halt halfway through a pull, that he had hooked the largest fish of the day. At first it hung up solid like a hook wedged between broken concrete, but he had snagged too many years to be fooled by first impressions. When the line started singing off the reel, he knew the spoonbill would go over 15 pounds. The paddlefish had his way for a while, and Lee just let him play out. As the fish gradually tired, the angler began gaining, inches at a time.

When the 10-inch snout first broke the surface, Lee thought he had misjudged the size, but when the rest of the fish rolled into view, his first guess was confirmed. It's not uncommon for paddlefish, like this old boy, to break off part of their snout. Usually they heal over neatly, though, and the injury had not hampered this fellow's feeding habits any. He would weigh in somewhere between 20 and 25 pounds. That would be an average size for snagging in January or February, when larger fish are the rule.

Mike was the only snagger left to limit out. And, it was just a matter of minutes be fore he hooked and landed a three-pounder to wrap up the day.

Hard pellets of snow started to pepper the fishermen, and winds were gusting to 30 or 40 miserable miles per hour. There was little disagreement with Willie's suggestion to pass up conventional fishing and call it quits. It had been a good day for that early in the season, but within a month, the average size of fish would increase considerably. Still, there were fleshy, white steaks as a reward for a day of harsh elements. With the fat just under the skin trimmed away, paddlefish is comparable in flavor to flat head catfish, and boneless to boot. Maybe that's what made the whole thing worth while. 12

WINTER COVER

(Continued from page 16)support these birds, and the state's population will grow. But good habitat is needed to block chilling winds and shield birds from smothering ice storms and blizzards. Where it is lacking, a rugged winter may eliminate many birds and the population will drop.

Cover alone, however, is not enough. Food, too, must be available. But adapted species do not necessarily depend on daily food. Some hibernate for the whole winter, while others sleep through only the worst periods, and all build reserves of body fat. A pheasant, for instance, can go for weeks, in good winter cover, without eating. That is why they can survive a blizzard and wait for food supplies to be exposed. Quail populations, however, may fluctuate more than pheasant numbers, because they can't last as long without food. The best gamebird cover for January, then, must have a food supply nearby, so birds need not expose themselves to hazardous travel for food.

Wildlife cover is provided by plants heavy grass, weeds, shrubs and trees. All, along with food supplies, are produced during the growing season. So, as people plan spring work around their own future comfort, they should also consider winter wildlife needs.

It must be remembered that, while temporary cover on croplands is vital to good wildlife populations, permanent cover in shelterbelts, marshes and any odd areas is the framework of farmland wildlife habitat. The largest shelterbelt or marsh will have little value for upland game birds if subjected to regular grazing, because birds must have cover at ground level. Often, such areas can be protected with a good fence. Plantings, too, often afford good protection. Planning new tree or shrub areas requires careful consideration, because the results require time to materialize. Woody plants take several years to reach useful size. Mistakes in planning are, therefore, quite permanent.

Many ground-cover areas mistakenly are situated so that a storm fills them with drifting snow, seriously limiting their value to wildlife. Windbreaks accomplish the most for wintering wildlife forming living snow fences to protect adjoining ground cover. Probably least valuable to ground-loving wildlife is a solid stand of tall trees, which forms a high, dense canopy of foliage that shades out all ground cover.

In selecting a site to develop for winter ing birds, pick one that will allow the largest acreage of winter cover. It should be big enough so that driving out all the birds would require considerable effort. Several acres might be involved in the best area but, lacking space, the developer could try for two smaller patches. Birds pushed from one site could retreat to the other without being forced to leave the farm. Also, two sites would be safer than one if either were unusually vulnerable to fire, floods or road construction. Plots of one-half acre or less may serve as marginal winter cover through proper placement of a single row of trees.

Few tree plantings in Nebraska are designed only for wildlife. Site selection and design can offer other values, including snow and erosion control, climate modification and screening and beautification. Fruits, Christmas trees and various wood products are also produced and may add to the value of the farm and add variety to wildlife habitat.

Selecting sites for wildlife plantings is usually a matter of using some spot unsuitable for farming or grazing. Such sites commonly range from one acre on up to five or more, and normally border a farm pond. Without such details as soil type, exposure and moisture conditions, only general recommendations can be made on what to plant. The main objective is to add variety to the environment by installing cover which contrasts with the surrounding area. Where the environment is cropland, add grass and trees. In areas of crops and grass, emphasis should be on woody plants. Food plots may be needed if the immediate area offers only pasture and woodlands.

Work for variety within the site, too, us ing trees, shrubs, grasses and legumes, in cluding as many kinds of each as practical. Trees should be of both the evergreen and deciduous groups. Trees and shrubs to be used should be restricted to low-growing types, eliminating types that could not be expected to do well on the site.

Variety is the key in grass and legume choice, too. Take one grass each from tall, short, cool-season and the warm-season growers. Use at least one legume which will cover the ground in a mass of vine and one that can possibly stand erect through the winter.

Plot design will vary from site to site depending on topography, shape and orientation to prevailing winds. The most generally desired feature will be a windbreak, or at least a living snow fence, including at least one row of evergreens on the north and west sides. If there is plenty of room, add a windbreak to the south and east edges to offer additional shelter for wildlife and live stock that may be in an adjoining field or pasture. Scatter clumps of shrubs through the interior for variety, but leave approximately one half of the space for grass and legumes. If the enclosed area includes a farm pond, add a few shade trees for the comfort of the fisherman. Take care not to crowd the fisherman with too many trees. He needs room for casting —lots of it for flycasting. If no fishing will be involved, avoid tall shade trees unless you want a large variety of songbirds. Tall trees com pete with ground cover and may attract birds of prey to the site.

Those who want cover quickly must realize grasses and legumes grow faster than

trees or shrubs, and that annuals are even

better. Therefore, part of the site should be

seeded to domestics or left to nature's an

nuals. These will provide cover and some

52

NEBRASKAland

JANUARY 1973

53

food while long-range developments are

taking shape. A brushpile which will be

ready for use within hours may step up the

process.

food while long-range developments are

taking shape. A brushpile which will be

ready for use within hours may step up the

process.

Most developers will look for all the help they can get. Sometimes volunteer labor is available through local youth groups, sportsmen's clubs and civic organizations while technical assistance may come from the Game and Parks Commission, the Agricultural Extension Service, and the Soil Conservation Service. In most counties, certain practices qualify for cost-sharing funds through the USDA Agricultural Stabilization Conservation Service, and your County Agent can order planting stock at reasonable prices through the Clarke McNary program.

Preparing the ground for seeding or plant ing may be as important here as for a garden or any field crop. Complete seedbed preparation is recommended without risking serious erosion, and may include allowing the ground to lie fallow for a year. Light soils that would blow if left exposed require modified preparation. Tree and shrub rows may be marked by a single pass of the plow to remove the sod, and even heavy soils on steep slopes will be treated this way with the rows following contours to combat erosion. Some sites will be too steep or small for practical machinery use, so hand planting, is required, and preparation, if any, will consist of simply scalping a small patch of sod from individual tree sites. Remember that willows and some other plants are started on wet sites by imbedding cut tings in the mud, while grass, legumes and annuals are established by a varying range of preparation and seeding methods.

Where food is needed on the site, select trees and shrubs that retain their fruits into winter. Include herbaceous annuals that do the same and tend to hold up under heavy snows and ice. Corn, milo and sunflowers are useful, but they may be made available more easily by simply leaving a few rows standing in nearby fields.

Developing new cover is only one answer to the problem of providing habitat. Cover will be available when needed in roadsides, fence rows, waterways and many odd areas if the farmer will simply adjust his haying dates and discontinue clean-up operations for the sake of appearances. Cover thus preserved is cheaper than that which must be established. Sites that are typically subjected to clean-up usually include good nestingcover. Wildlife usually faces two critical periods each year, the winter survival period and the spring reproduction session. Success in either depends on the whims of weather and how man shapes the habitat. Remembering that 70 percent of the pheasants in any fall population are young-of-the-year, we realize that one or two years without reproduction would finish any flock. We must preserve good nesting cover.

Preserving existing cover is the primary objective of the Nebraska's Acres For Wild life. This program offers recognition to cooperating landowners in the form of arm patches, certificates and a free subscription to NEBRASKAland Magazine. A letter to NEBRASKAland ACRES FOR WILDLIFE, P.O. Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503 will bring the needed enrollment form.

Farmers who can keep wildlife in mind as they plan routine operations should remember that permanent cover is only the framework wildlife environment. Crops and pasture hold the bulk of the habitat, and while hundreds of thousands of acres of pasture and range are under good manage ment, much more could be improved. Pastures closely resembling golf courses support less livestock and wildlife than they would under better management.

Croplands generally hold a surplus of cover from early summer through harvest time. Then come combine and picker, closely followed by plow and disc. We know that farmers are on the land to make a living, but we know, too, that some should leave crop stubble standing through the winter to hold light soils in place and catch snow for a moisture reserve. Then there are marginal situations where there is no clear indication of whether fall or spring plowing is beneficial. Forty acres of good milo stubble may be worth a lot more than an island of developed habitat, and the 40 acres may hold snow that would otherwise choke the habitat plot. We want to reach

the man who has no clear economic indication of what crops to plant. If he is con cerned for wildlife, we can throw that weight towards the crop that is best for the pheasant. We want to help the man who can't quite decide whether to cross-fence the pasture to facilitate a rotation program — such contact could result in 100 acres of improved cover.

Every decision made by the farmer or rancher affects the environment. No daily action, nor annual decision will leave the habitat as it was. Who are the real game managers in Nebraska? It is obvious that they are the people who manipulate the environment, the private landowner, the farmer and the rancher.

FOCUS ON WILDLIFE