Nebraskaland

December 1972 50 cents 1cd08615 decorate with nature ten wildlife originals the history of Fort Robinson walleye of Mac Season's Greetings

For the record...

THE ONUS IS YOURS

Fish and wildlife management could be defined as planned husbandry of our fish and wildlife resources to prevent exploitation, destruction or neglect. This is the definition from which the Game and Parks Commission draws its purpose. It manages the state's fish and wildlife, and in doing so it is equipped with better management techniques and methods than ever before. Years of research and experience have seen to this. At the same time, the public interest in wildlife is at an all-time high. We are, however, entering a period characterized by unprecedented declines in fish and wildlife populations, and all the increased public interest will do us little good except to stretch a thin resource a little farther.

To understand why, look at what has happened to agriculture during the last 10 years. Nebraska has more than doubled its grain sorghum production, increased corn production 65 percent, boosted its wheat production 36 percent, upped its soybean production 114 percent and increased its calf crop 21 percent. In the past 10 years, we have increased our irri- gated acreage 54 percent and the use of fertilizer 173 percent. The statistics go on and on.

Although these increases enamour the agriculturalist, they are bought at the expense of wildlife and environmental quality. What is frightening to the fish and wildlife enthusiast is that the drive to further increase agri- cultural production is stronger than ever. Nothing succeeds like success. Wildlife is a product of the land, and its needs from the land are measured in terms of acres of habitat needed for food, safety and reproduction. This is where agricultural statistics have meaning. Each additional acre of corn, each additional cow on pasture, or each additional steer on feed means a loss of wildlife habitat and an added burden on the environment. If the hunter, the nature lover and the environmentalist want to continue enjoying wildlife, one or both of two things must happen. The agriculturalist must stop increasing his corn and cattle crop, or the hunter, the nature lover and the environmentalist must stop eating beef. Unfortunately for fish and wildlife, the prospects for either happening are slim. If the consumer wants more beef and the agriculturalist wants more profit, there will be less wildlife and more environmental problems. It's that simple.

An alternative that is still open is to give wildlife and environmental programs more support. When you look around you and wonder why game isn't as abundant as it once was and the land is more run down, it isn't because the Game and Parks Commission is doing a poorer job of management. The reason is because we are continually being forced to do more with less. And it's beginning to show. Your legislature meets again this year to allocate money for various purposes. I suggest to you that if you want to give wildlife a better chance in the face of rapid changes on the land, make your feelings known to your legislator. Give your support to wildlife conservation programs, for at no other time in our history has wildlife needed more help.

Speak Up

NEBRASKAland Magazine invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to Speak Up. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters. — Editor.DO I? — "As the hunting season approaches, please consider a hunter safety article in one of your autumn issues. Most farmers are quite liberal in granting hunting permission on their land, but in return would appreciate sensible and considerate behavior from the hunter.

"When hunters go out to the country, it would be well for them to review their habits and ask themselves a few questions:

"Do I ask permission before tramping through the fields?

"Do I fire from the road?

"Do I park in the lane of traffic on country roads? (If you park in the center of the road just over the crest of a hill, it is very hazardous.)

"Do I take careful aim, noting farmsteads and livestock?

"Do I close gates upon entering and leaving fields?

"If you have been denied hunting privileges, the farmer, no doubt, has experienced some careless hunters' activities.

"Hunting is a wholesome sport and most hunters are alert, but a safety article would help keep it foremost in their minds." — Mrs. Francis Schmidt, Howells..

NEBRASKAland carried an article on hunter safety in the September 1972 Special Hunting Issue, and sensible and considerate behavior from the hunter was the subject of an editorial in the October 1972 issue. Such story recommendations from readers are always welcome. — Editor.

BAD NEWS —"For the past three years, my son, two of my brothers and I have hunted pheasants in the Fairbury-Jansen-Beatrice area, and enjoyed our hunting very much. We always looked forward to the next trip — up until last year, that is.

"We have always asked permission before hunting, but in 1971, we were turned away by the landowners and could not think of a reason for their attitudes. Later, we started asking questions and were told by different people that some hunters had let their dogs chase livestock, left gates open and threw beer cans out in the fields. We also were told that more wealthy hunters from the Omaha area were paying land-owners to keep out-of-state hunters off their land —all of which is wrong.

"Therefore, we will not return to Nebraska until these conditions change. This year we are planning on going elsewhere to hunt, and we are not happy about it because we really did like hunting in Nebraska.

"I believe the Game and Parks Commission could control these few hunters who have no respect for the land. A few hunters with these attitudes can ruin the sport for many who enjoy hunting. And, when these conditions change for the better, I would like to know so that we can start returning to Nebraska." —Robert L. Browner, St. Louis, Missouri.

PLACID PLUCKING- In the story Snipes Turned Ducks, August 1972, you show a picture on page 41 of two big game hunters placidly plucking their big bag of ducks, polluting and littering the land with their offal. Where was the conservation officer mentioned earlier in the story? He should have been there to make the justifiable arrest.

"The city slick gunners too oft encroach upon private property with or without permission in their quest for our wildlife. "In their wake, they are generous enough to leave behind their bottles, cans and other lunchtime refuse for our livestock to graze around; our tires to get cut by. Disgusted, we pick up this trash in remembrance of our doddamed city cousins." —Ron Blaser, Columbus.

The photo, as was mentioned in the story, was taken on private land while hunting at the owner's invitation. The Nebraska Game Code states: "It shall be unlawful for any person to place, throw, scatter ...any garbage, cans, debris, refuse... upon any lands, premises or property not belonging to, or under the control of such person. The provisions of this section shall not apply to any person who shall place, throw, scatter, or deposit any such material upon lands, premises, or property, with the permission of the owner of such lands... Clearly, field dressing game birds or animals on private land is, in fact, legal with the owner's permission, as was the case here.

Under conditions where game will be transported any distance, proper field care is an absolute necessity. Wildlife hunted, negligently cared for, and as a consequence later discarded, is certainly a greater misuse of a resource than feathers and offal returned to the soil. In this case, the offal was disposed of some distance from the windmill in the photo, precluding any possible contamination of the water supply. Even this action seems somehow superfluous considering that cattle using the windmill are less tidy. Still, though, such practice is a goodwill gesture toward the landowner and should be observed. -Editor

JUST ONCE MORE- "Must you take up an entire page of your magazine to advertise the curves, charms and bare behind of this female? (NEBRASKAland Hostess, August 1972). No part of her body is covered except the most secret parts, and I dare say a slight breeze could carry away even that half-ounce of nylon.

"I just want to tell the leg watchers that they will be obliged to get along without my support of this form of entertainment. More such pictures and I am through with NEBRASKAland"-Mrs. Kathryn Haglund, Ponca.

LOFTY LINES-"The following lines came to mind recently when I was on a flight over Nebraska."—J. F. Anderson, Harrisburg.

I love to fly in winter When the ground is white with snow. And watch the pretty landscape So very far below. Now great white fleecy clouds We've all watched up in the sky, Are this day far below us And slowly passing by. By day we see the winding trails And crooked little streams. Each one means much to someone In their work or in their dreams. The farms all look so tiny And the towns are little too. And down there unseen people Each with his "thing" to do. At night we faintly see the light From someone's home down there. Are the people inside happy Or is there tension and despair? If we could look down on our troubles From a distance in the sky. Maybe they would look much smaller And would sooner pass us by. This scene should make us thankful For our lives in this great land. And to know that our Creator Holds it all within tfis handUNFAIR-"! would like to register a complaint! I feel that it is unfair that at 16 I have to buy a hunting license, and can't buy shotgun shells. I wonder if anything can be done about it." —Jeff Vojtch, Ralston.

Thousands of young hunters are in the same position due to the 1968 Gun Control Act passed by Congress. The only recourse is to contact your senators and representatives to try to initiate counter legislation for the repeal of that act. - Editor.

HOW TO: Make Venison Burger

Running a deer through a grinder yourself allows variety of mixtures for special uses

WHEN A HUNTER returns from the woods wearing a smile of satisfaction as he hauls home his deer, he is often confronted with a problem altogether different from the one he took afield. Now he is not concerned with out-smarting his quarry, but how to get the fresh meat out of the hide and into the pot.

Not many people, even experienced hunters, have the time or inclination to convert a big-game animal into meal-size chunks of meat even though the task is relatively easy. But, for those who wish to try their hand at preparing their own game, here are some hints for making venison burger.

The taste of meat varies, depending on the deer's age, eating habits and the care it received after the kill. But, even so-called "strong" venison can be processed so that it will taste finger-licking good.

Grinding venison into burger is an ideal way of using all but the choice cuts. Seasoning can be added as desired and the meat can be packaged in various sizes. A distinct advantage is that the finished product can be used many ways. Prepared as venison loaf, or spaghetti sauce, or just grilled outdoors and slapped onto buns, ground venison fills the bill in many ways.

You can have the meat ground by a butcher, but that is not necessary. One spare evening after the meat has been aged from a few days to a week can result in a neat pile of packages for the freezer.

There are several tasty recipes, and the following (Continued on page 12)

10 NEBRASKAland

VENISON BURGER

(Continued from page 10)year, if you do it again, you can repeat your favorites.

A regular-size home grinder does the trick. The only problem you encounter is running beef tallow through the grinder. Tallow tends to work its way toward the outer edges of the tunnel, gumming up the works. It is best to buy tallow which is already ground and then work it by hand into your venison after it is chopped.

But, first things first. Assuming you have already skinned, boned and set aside the choice cuts, trim the rest of the meat into pieces that will fit into the grinder. Grind it twice with a medium plate or once through a coarse plate and then again through a fine one. About 30 pounds of venison can be ground in 10 minutes, depending on who is working the handle.

Among the most popular mixtures is the one in which you use one part beef tallow to five or six parts venison. Another requires three parts fresh pork to seven parts venison. Yet another requires one part seasoned pork sausage to nine parts venison. If you add your own seasoning, it can be worked right into the mixture, but some people prefer leaving it unseasoned until it is to be fried or cooked. Adding a bit of pepper while blending your mixture won't hurt a thing. Using commercial, packaged seasoning is another possibility.

All the above mixtures have their own distinctive tastes, and all serve different purposes. The one with seasoned pork sausage, for example, makes excellent meat loaf. For grilled venison burgers, the one with beef tallow is probably the best. And, the one with plain, lean pork added lends itself to dishes requiring milder flavoring, thus making it more versatile than the others. This last mixture, incidentally, costs a little more because of the amount of pork in it.

Butcher shops and lockers capable of handling wild game will prepare your meat for you according to the recipe you provide, but these establishments are usually very busy during big-game seasons. Besides, doing the work yourself is cheaper and gives you the satisfaction of a do-it-yourself project. The above three methods have been used for many years. So, next time you have both a deer and some time on hand, go the home-grinding route. You'll be pleased with the results; so will the dinner guests you invite.

Fort Robinson: Prelude

Out of troubled times sprang a famous Nebraska post

LIEUTENANT H. Robinson stood on the brink of the immortality on February 9, 1874, but m there was no way he could have known about it. At 34 years of age, Robinson was a junior officer in the United States Army, and was stationed at Fort Laramie, Wyoming. Of average height and dark complexion, the lieutenant looked every inch a career soldier, what with his tidy moustache, close-cropped beard and a piercing gaze that must have cut right through the ranks of enlisted men when the need arose. That particular day, though, Lieutenant Robinson was not planning his future, nor was he involved in any great military decisions. Instead, he and two enlisted men were making a mistake that no white man could afford in Indian country. Robinson, Corporal Coleman and a private named Noll had strayed from a guarded wood train on the Little Cottonwood Creek about 12 miles east of Laramie Peak. That tactical error cost the lieutenant and the corporal their lives when some 40 to 50 hostiles swooped down on them. Only Noll escaped to recount the happenings.

So, Lieutenant Kevi H. Robinson missed the frigid morning of March 2 when 547 cavalrymen under a Major Baker rode out of Fort Laramie. Nor was he on hand when, the next morning, 402 infantrymen commanded by a Captain Lazelle took (Continued on page 58)

A World Apart

Our globe is in ferment, and this remnant of our past may be a grotesque prophecy of our future

WE ARE a people in turmoil! Within recent years, mankind's attention has been focused on a situation few outside the technological clan even knew existed a decade ago. "Preserve the ecosystem, " has become the cry of millions, a large portion of whom cannot even define the term, yet who join in the wail for the sake of social acceptance. Tethered to the coattails of bona fide researchers, though, they become knowledgeable and correct to some extent. They note that our globe is in ferment; that our rivers and lakes have become communal sewers; that our air grows thicker by the minute. They deride noise, another product of our progress, which threatens to overpower even the most audible alarmist cries. We sit and wait, and wonder at what end we do not know.

Nebraska, unlike many of its continental neighbors, remains on the fringes of congenital contamination. There still is fresh air and there is still pure water. Locations remain where the solitude of the ages reigns supreme. Granted, these things are not the ideal of everyone, but there are those who savor such things. For them, there is a remote, even desolate expanse in northwest Nebraska called Toadstool Park. Here nature plays her game with

Officially Toadstool Geologic Park, the area is named for sandstone and clay formations within its boundaries. In the dimness of prehistory, the earth beneath massive stone slabs began.to erode through the actions of wind and water. The process took on strange dimensions, however, as columns of clay remained to support smoothed tabletops of stone.

Toadstool Park is more than its name implies, however. Towering buttes reach to the sky in virtually every corner. Twisting canyons weave back and forth in a seemingly endless maze. Some have likened the park to a lunar landscape, and with good reason. Colored yet colorless, the park stretches out like a giant relief map to confound even the most competent of pathfinders. One can easily become lost amidst these corridors and spires-not only physically, but mentally as well. Little, after all, has changed here since time began, a premise which easily eludes comprehension. There is, too, another aspect to the experience of Toadstool Park. Indeed, the region remains much as the world may have looked eons past, but might not its bleak and bizarre facade predict how it might look in the years to come?

Instant ecologists they are called-those who have recently adopted the credo to save the earth. They are not totally right, nor are the giant manufacturers who are their chosen foes totally right. But they do see much more clearly what could lie ahead for humanity if nothing is done now to halt the rape oh Mother Earth. And Toadstool Park, a direct link with a world long gone, could well be the beacon of the world yet to come.

the Future of Farming

From organic agriculture we have come, and to organic agriculture we must return to survive

ONE OF THE characteristics of modern society is that it is constantly changing. We feel change is inevitable and a sign of progress. We must go "forward." Just where this leads us no one really knows, but everyone assumes that surely tomorrow things will get better and that the "good life"-the world of beautiful, happy, smiling faces; never-ending backyard picnics; walks through primeval forests; sailing across blue water; riding through miles of uncluttered rural landscapes filled with trees, hedges, grass and picturesque farmsteads-is out there someplace.

Slowly but surely we are realizing that what we are really finding "out there" are artificial dentures, plastic flowers, rubber turf, decaying cities, sprawling suburbs, traffic jams, polluted streams and a countryside covered with the monotony of a single crop while the contrasts of color and shape that were created by agricultural diversity have all but disappeared. We find a people tired in spite of easy life, sick in spite of all our hospitals, bored with their jobs, forever seeking the "good life" but never finding it. The unvarying monoculture one finds in the country seems to be complemented by decaying culture in the cities.

Migration of people from the countryside goes on. Everyone agrees cities are too large but they keep on growing. The countryside is dotted with abandoned homes and schools. Cities abandon their centers and simply move out into the country and start anew, using up more good land. No one seems to realize that someday this new suburb or shopping center will be old. Where to then?

24 NEBRASKAlandThe sense of community that helped build this civilization is disappearing from both rural and urban cultures. The concentration of people creates ecological imbalances that nature cannot cope with and it may very well be that man will never really adapt to the urban life this technological revolution is thrusting upon him.

Man is a biological creature whose physical requirements are wholly and entirely found in the good earth. He must, of necessity, remain close to this source of his sustenance. Many young people feel that they want to take a more active part and become more intimately involved in the production of their daily bread. Perhaps they realize this is the only way to give life some meaning and attain some self dignity. One is often reminded of the millions of people who have lost their identity and self-respect after moving from the country to urban environments.

The migration of people from farms to cities is the inevitable result of the forces of technology. Technology has developed techniques both in industry and in agriculture which demand the substitution of the stored energy of fossil fuels for that of human energy. This, of course, is what is really bringing on the energy crisis which we read about and, in fact, see developing around us. It is estimated that each of us uses the energy equivalent of 500 human slaves during one day's living and the end is not yet in sight. There is much evidence that the efficiency of both agriculture and industry, in terms of energy input and what we produce, is going down. In agriculture we have probably reached the point where we are using more energy than we are producing. When one studies (Continued on page 62)

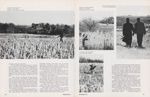

A pleasant fall day, a dependable dog and a group of friends make for a memorable outing in quest of Nebraska upland game

Sally was a good old girl

PRANCING THROUGH high brome, the Brittany was eager for action. The 1971 pheasant and quail seasons were already 14 minutes old, and Sally had yet to produce even a cackle for her master and his California hunting friends. "Easy Sally," Merlyn called out in an attempt to calm his nervous pointer. Merlyn's words were hardly out when Sally locked into a point. Seconds later, a squawking rooster pheasant rocketed from the frost-covered grass directly in front of Dr. Larry Paben. Instinctively, he shouldered his scattergun and touched off a load of shot that folded the fleeing ringneck. Sally raced for the retrieve.

"Thanks Sally." The affable dentist patted the enthusiastic dog softly and pocketed his bird.

"Nice shot, Doc," his hunting companions chimed in unison—

"Wouldn't you know it? The old tooth carpenter bags the first bird" Ellis VanDeburg said.

"Let's work on through this grassland and then walk the corn to the milo field," Merlyn suggested, offering his ringneck strategy to the trio of California hunting guests, Dr. Larry Paben, Dr. Bud Webb, and Ellis VanDeburg, all from the Los Angeles area.

Small plot of ground on very outskirts of town holds promise of action behind each stalk

For the most part, their annual hunt is a reunion for Larry and Ellis, since both are Talmage natives. Merlyn Osborn was the sole "current" Nebraskan on the opening-day outing. Owner of a local Talmage Insurance Agency, Merlyn has never missed the hunt. Bud Webb fit into the picture as a Californian originally from Illinois and a long-time personal friend and hunting companion of both Larry and Ellis.

"These fellows first brought me back here to hunt five years ago," Bud began, carefully tamping tobacco into his favorite pipe. "The first year I came out, I wondered about all the fantastic hunting Larry and Ellis always talked about. But, seeing is believing, and doing is even stronger proof. I don't think there's any better pheasant and quail hunting anywhere. Everybody willing, I hope to be coming back again and again and again."

As the foursome began working through the recently harvested cornfield, Sally continued to work with "show-through" enthusiasm. It was a perfect November morning-clear skies, crisp air and the temperature somewhere around 30 degrees. The ideal hunting weather mocked the weatherman who, the night before, had predicted freezing rain and strong winds for the November openers.

"Look at that," Ellis said, shattering the stillness as he pointed off toward the eastern horizon. "A beautiful sight. Pintails I would guess from here," he concluded. In the distance, a long line of ducks moved toward the hunting party.

Suddenly, the whir of wings and the flurry of small brown birds jetting from the cornfield preempted further discussion as the hunters were quick to aim and fire. When the shooting was over, Sally retrieved two bobwhites, and Ellis picked up a third.

"Pretty sharp, fellas," Merlyn congratulated. "Who would have ever guessed those bobs would have been out here this time of day?"

The hunters worked on through the cornfield without further action. As they regrouped back at Merlyn's station wagon, an inventory of the first field hunted showed one ringneck and three quail.

28 NEBRASKAlandA short drive to the next area put the hunters at the beginning of a mile-long hedgerow-prime cover for ringnecks and bobs alike. The car had scarcely stopped when Sally leaped from only a slightly cracked door and began preparing for the next hunt. The sun was climbing rapidly and the golden rays felt good as the crispness of the fall morning pinched at the veteran hunters' noses.

"Remember this hedgerow from last year, Larry?" Merlyn asked. "We knocked three roosters out of it on opening morning. Let's see about this year."

Forty-five minutes later, the question was answered as the hunters returned and climbed back into the weathered station wagon —empty handed. "I can't remember the last time I walked that hedgerow without scoring," Merlyn lamented. "Oh well, it's probably a good thing. I'd hate to see us all have our limits this early in the day."

A few minutes later, the quartet was enroute to the next area. "Let's try the multi-flora back south of the house," Merlyn (Continued on page 53)

Kuhlmann- Cattle King

Cattle thrive on Nebraska grass, and so has the business prowess of North Platte beef empire

FAMILY TIES being what they were in the early years of this century, it was only natural that, when grassland became scarce in Thayer County, Henry Kuhlmann, Jr., started looking for another ranch. He had seven sons and there just wasn't room for all of them on the southern Nebraska place, so he headed west. It took several trips before he found a suitable spread just west of Brady, but still it wasn't exactly what he wanted. Then, in 1927, the William F. (Buffalo Bill) Cody ranch near North Platte went up for sale and Henry latched onto it. In the years to come, that 1,157- acre ranch was to become a showplace of the cattle industry, retaining, at least in part, much of the glamor it knew when the great Western showman called it home.

Some of Henry Kuhlmann's boys drifted out of ranching, but others stayed —among them was Orvil. Today, the name Orvil Kuhlmann rings loud and clear wherever prize polled Herefords are shown and sold. From his headquarters on the original Cody spread where he grew up, Kuhlmann rides herd on a world-wide reputation as one of the top men in the livestock industry. It's been a long road to his present status, and a lot of hard work went into building the Kuhlmann name.

"I raise polled Herefords largely because my father raised them," Orvil said, "even though his introduction to them was pretty much a fluke. He was feeding horned Herefords near Chester in Thayer County in 1917 when he took a shipment of market beef to a sale, intending to pick up a load of feeder cattle for the return trip. He sold those he had brought and outbid everyone else for what seemed a likely bunch of Hereford heifers. When the sale was over, Dad was talking to the previous owner when the latter asked if he wanted to have the papers transferred. It seems those cattle were registered Herefords, but it didn't seem too important at the time. My father intended to feed them out and sell them just like the others he had. A little conversation convinced him to take the registrations, though, and he was in the polled Hereford business."

Henry had the heifers, but he lacked a polled bull. Money was scarce in those days and even then registered sires came high. So, he paired his females with a horned male. The result was a crop of 80 percent polled calves. A few years later, he invested in a polled bull to really put the registered breed business on its feet. Caution usually comes with handling high-priced stock, and such is the case here since without a certain amount of prudence, all could easily be lost to myriad dangers.

The Kuhlmann legend began with Henry, Jr., but Orvil is the man who really got it going. He worked with his father until, some 33 years ago, he broke into the breeding business on his own.

"When I decided to try for myself, I already had 20 females and I was using my father's bulls. Later, he gave me the pick of his herd bulls. Those heifers, a single bull, and a sizable mortgage on the place were all I had, but the animals paid off. When I dipped into Dad's herd, I took Advance Domino 30. A bull is usually good for about eight years and I used him for all of that before I sold him for $12,000," Orvil explained.

From raising and selling, it was only a short step into the show arena. For a man whose first memory was of haltering a Hereford calf, cattle were in the blood to stay —win or lose.

"We've shown in Portland, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Fort Worth, Houston, Jackson [Mississippi], Chicago, Kansas City and everywhere in between. Our peak show years were in the 1960s when my son-in-law and oldest son traveled with the stock."

From his years on the show circuit, Orvil has naturally chosen some top bulls from among his prize winners. His first bull, Advance Domino 30, heads the list with Gold Mine and Diamond running close seconds. He also feels Golden Diamond should go right in there with the rest since the bull topped the Register of Merit, the bluebook of the cattle industry, and was the product of all three of the other champions. Competition and excitement are only part of the overall aura of the ring, however. There is much more to winning than just taking home a platter or cup.

"The prize is the least important. Taking a top place really points up accomplishments in breeding programs. In a business like ours, where cattle are a livelihood, wins mean sales. Everyone wants stock bred by a champion, but there's not much market for a loser's offspring. Consistency is another important factor. You might get lucky once or twice, but when you win regularly over 20 or 30 years as we have, breeding, not luck, is the factor," the 62-year-old cattleman explained.

To call the Kuhlmanns successful and consistent is an understatement. In 1963, they built a 34 x 24-foot building (Continued on page 57)

30 NEBRASKAland

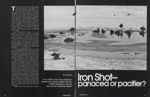

For a century, lead shot scattered in marshes has caused wildfowl die-offs. Federal regulations may ban lead, but are substitutes better?

Iron Shot - panacea or pacifier?

THIS YEAR, one to three million ducks, geese and swans will die in the wetlands. They will not die because of some natural catastrophe and they will not land in a hunter's game pouch. They will succumb to a slow, lingering death from lead poisoning. Their loss will mean fewer ducks over hunters' blinds, fewer geese to stir the soul and a dramatic reduction of breeders to return north to the nesting grounds. Lead poisoning has become an environmental problem of national importance; next to hunting, it is probably one of the most important unnatural causes of waterfowl mortality. Far-reaching changes in waterfowl regulations seem inevitable. Duck and goose hunters not now aware of the problem may soon be jarred from their complacency with the possible elimination of the 1973-74 waterfowl season, unless a non-toxic substitute for lead shot can be found.

Lead poisoning of waterfowl is not a new problem. For more than a century it has been known that lead shot, discharged over feeding grounds by hunters, can be picked up by fowl and result in poisoning. In 1842 a paper was published in Berlin on the effects of lead upon animals. An 1894 issue of Forest and Stream carried an article by hunter and naturalist Dr. George Bird Grinnell, dealing with the lead poisoning of waterfowl. Investigations on western duck sickness and lead poisoning in waterfowl were already being conducted in 1919. Though we understand the problem now, a solution eludes us.

It has been estimated that 6,000 tons of lead pellets are discharged over waterfowl-use areas in the United States every year. Fortunately most of this potentially toxic lead falls in deep water, flowing streams or soft-bottomed lakes or ponds, and remains unavailable to feeding waterfowl. Some, though, accumulates on hard, shallow bottoms and remains available to ducks and geese for years.

Lead pellets picked up by a feeding bird are retained in the gizzard and subjected to its grinding action and digestive juices. As the lead is eroded from the surface of the pellets, soluble lead salts pass into the digestive tract and ultimately through the entire body. Partial paralysis of the gizzard results in a decreased food intake with starvation the ultimate fate. Anemia and emaciation as well as muscular and tissue atrophy occur. The characteristic "razor-keel" or "hatchet-breast" results from the loss of tissue in the flight muscles of the breast. Birds suffering from late stages of lead poisoning swim in a hunched position, have difficulty walking and fly unsteadily. Wings begin to droop at the sides and float loosely on the water. Inflicted birds find it increasingly difficult to hold their necks erect. Usually they seek isolation on shore or in dense cover where they die. Most deaths from lead poisoning are unspectacular and unreported.

Estimates of the actual magnitude of lead poisoning NEBRASKAland DECEMBER 1972

vary, but even the lowest figures are alarming. Frank C. Bellrose, a wildlife specialist with

the Illinois State Natural History Survey, an acknowledged expert on lead-shot poisoning in waterfowl, concludes that for all waterfowl species in

North America, the annual loss because of lead

poisoning is between two and three percent of the

fall population. With a population of more than

100 million ducks, geese and swans, the annual

loss would be between two and three million birds.

According to Bellrose, the annual loss is averaging

close to the total number of ducks produced in the

states of North and South Dakota, the two most

prolific waterfowl-producing areas in the United

States. Other estimates range lower in the neighborhood of one million birds.

vary, but even the lowest figures are alarming. Frank C. Bellrose, a wildlife specialist with

the Illinois State Natural History Survey, an acknowledged expert on lead-shot poisoning in waterfowl, concludes that for all waterfowl species in

North America, the annual loss because of lead

poisoning is between two and three percent of the

fall population. With a population of more than

100 million ducks, geese and swans, the annual

loss would be between two and three million birds.

According to Bellrose, the annual loss is averaging

close to the total number of ducks produced in the

states of North and South Dakota, the two most

prolific waterfowl-producing areas in the United

States. Other estimates range lower in the neighborhood of one million birds.

The frequency and extent of lead-poisoning outbreaks in influenced by many factors —the size of late-fall and winter populations, the type and amount of food available, the amount of lead shot present and the availability of shot as determined by bottom conditions, water levels and ice cover.

Most waterfowl deaths resulting from lead poisoning occur during the late fall and early winter. Hunter activity during early fall months generally precludes waterfowl use of areas where high concentrations of shot are likely to be present. Deaths in the spring are not common but do occur. Early winter, immediately after hunting season and before a freeze, is the critical period.

The type of food available and used by waterfowl is significant. Feeding habits seem to dictate the likelihood of ingesting lead into the body. Some disagreement exists as to whether lead is sought out as a grit substitute or accidentally taken while feeding. Most authorities now believe the latter to be the case. Consequently, if a bird's feeding regime places it in areas of shot concentrations, it is more susceptible to lead poisoning. Duck species, their respective feeding habits and the incidence of lead poisoning in those species are closely related, suggesting that this is the actual case. Dabbling ducks, especially pintails and mallards, encounter shot more frequently while feeding than deep divers such as the scaup, which feeds in aquatic areas of low shot accumulation. The low incidence of lead poisoning in baldpate and gadwall can probably be attributed to their inclination to feed on the foliage of plants instead of bottom muck. While such species as teal and shovellers feed on mud flats —areas with high concentrations of shot—they tend to be surface, rather than bottom feeders, and are generally not seriously threatened by lead poisoning. Divers, like the redhead, canvasback and ring-necked ducks, customarily dig for seeds and tuberous aquatic plants, in areas where expended shot abounds. Their more vegetative diet, however, as opposed to the grain diet of mallards and pintails, seems to lower occurrences of lead poisoning.

Some researchers believe a corn diet has a more direct effect on the occurrence of lead poisoning by increasing gizzard activity and hastening wear on lead shot and, consequently, speeding absorption into the body. One group of researchers in Canada now theorizes that this is not the case. They believe that the low amounts of selenium in a corn diet may be the actual cause of lead poisoning in species that are extensive grain feeders. Selenium, researchers have found, tends to counteract the effect of lead salts in the body, and birds on selenium-rich diets are less prone to succumb to lead poisoning, even though shot was picked up. As a possible corrective measure, the possibility of alloying trace amounts of selenium in lead shot is receiving further research.

In Nebraska, and generally in the Central Flyway, the problem of lead poisoning is not as significant as in the other three North American flyways.

"There is not a large loss because of lead poisoning in Nebraska/' George Schildman, waterfowl specialist with the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission believes, "but some does occur every year. Last year we had an actual count of approximately 50 ducks, mostly pintails, lost on Hansens Lagoon in the Rainwater Basin area of south-central Nebraska. Correlating that count to the entire area, the loss could be estimated at from 200 to 300 birds."

Schildman believes there is not a significant problem elsewhere in the state, such as in the Sand Hills or along the river systems.

"In marshes with clay, hard-pan bottoms, like the Rainwater Basin or a small area north of Lincoln, lead does not work into the muck and is available to waterfowl. Lead poisoning can occur. The Capitol Beach area, before development, had substantial kills due to lead poisoning. As many as 2,500 to 3,000 snow and blue geese stopped there every spring, when it was especially bad. I collected the gizzards from 60 to 70 of the more than 200 sick and dead geese. Each had died from lead poisoning. Later we tried to haze them with an airplane to move them on, but we had little success."

Schildman sampled the top two inches of the lake's bottom and discovered expended shot, expanded to nearly twice its normal diameter. The outer layer had oxidized and become flaky, indicating that the shot had accumulated on the bottom for some time, perhaps years. Within 14 days after the geese arrived, sick and dying birds were noticed.

Jack Sinn, while manager of the Sacramento Game Area in the heart of the Rainwater Basin, also noted waterfowl deaths due to lead poisoning. In fact they were common. (Continued on page 57)

Next to hunting, lead poisoning is the major unnatural cause of waterfowl mortality. This year one to three million ducks and geese will die 34 NEBRASKAland

Christmas trees have become traditional, but what is a tree seems undecided. Weeds and plastic vie with the real thing

Fir & Such

PERHAPS the oldest custom still observed by modern people is the adorning and lighting of homes during the Christmas season. This ceremony originated so long ago —sometime between the fourth and eighth centuries A.D. —that the beginnings are noticeably hazy.

Both pagan and Christian influences mingle in the various facets of yule festivities, and certain aspects were adopted over an extended period from many different areas of the world. Even now there is no specific way of celebrating the Christmas season, al- though it is generally agreed that the majority of people do respond to or help spread the aura of goodwill generated at this time of the year.

The tradition of the Christmas tree, notably fir, can be traced back well over 1,000 years. At first it was probably a mere branch or undecorated tree, but eventually this (Continued on page 52)

All in a month's work

Artwork on deadline is a precarious balance. Bud Pritchard, though, takes it all in stride

38 NEBRASKAlandNEBRASKAland's C. G. (Bud) Pritchard and his artwork are certainly not strangers to regular readers. This is the third consecutive holiday season in which we have featured collections of his art. There is a reason for our selection. Bud is talented! But, too, we feel that there is something festive about the way he treats the world of wildlife which has become his stock-in-trade.

The selections presented here were originally published in the Game and Parks Commission's Hunting Map of Nebraska. They were produced after one month's effort and are designed to acquaint everyone with the major game species within the state. We like them, and we're sure you will too.

Walleye at Mac

There are certain tricks which make fishing the state's largest lake just a little easier for this Omaha couple

A CHILL October wind carried a crisp reminder of fall as it whistled across the sandy beaches of Lake McConaughy to sweep out over dark blue water. Small, white-capped waves were slowly building as Paul Krajicek, his wife Mary Lou and I launched their 16-foot fishing boat from the northeast side of Martin Bay.

McConaughy never fails to stir me with its beauty, even though I've lived near the lake most of my life. For Paul and Mary Lou, who live in Omaha, it was the fifth trip of the year to Big Mac.

The rising sun was just skimming its welcome warmth over the top of Kingsley Dam as we rounded the first sandy point west of Martin Bay and headed for Paul's favorite fishing spot.

"This is where we seem to catch the most fish," Paul pointed out. "The area runs along the north shore from the first bay west of Martin, and continues on for about five miles." As Paul slowed the boat to trolling speed, he explained that his fishing equipment and methods had changed a great deal after two unsuccessful trips to Mac several years earlier.

"Our standard fishing outfit for Mac is a seven- to eight-foot trolling rod rigged with a heavy-duty casting reel and more than 100 yards of lead-core trolling line. With the light spinning rods we used, we could never get the lures down to the feeding walleye. We could pick up surface-feeding trout and white bass, though.

"For lures, we have pretty much settled on silver shad imitations and pearl flatfish. These seem to match the feeding fish's diet, and we have had very little luck using other types of lures."

"Another item we've found indispensable is the depth finder. Unless you know the depth, you can waste hours and even days trying to find the right feeding shelves. By using the fishscope, and keeping good records of where most fish are caught, it's fairly easy to return to feeding beds where the fish hang out.

"The underwater topography has a lot to do with a feeding area, because walleye seem to lie close to dropoffs, waiting for unsuspecting minnows and shad to swim over. The bait fish can't see the waiting walleye because he hangs in close to the side."

With a final adjustment in trolling speed, and a quick glance at the bright depth indicator on the finder, Paul and Mary Lou began paying out their multi-colored lead-core line. The colors, changing every 10 yards, provided yet another aid in getting the lure down to a known depth.

"How much line will you have to let out to put the lure on the bottom?" I asked, noting that the indicator was reading about 45 feet. "Figuring the boat speed and the depth, we (Continued on page 62)

48

NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA...

ORANGESPOTTED Sunfish

Small or medium-sized streams are preferred homes for this colorful resident. Rarely taken by anglers, once seen this fish is not soon forgotten because of its brilliance

THE ORANGESPOTTED SUNFISH is one of Nebraska's most brilliant, multi-colored fish. Small in size, the fish seldom exceeds four inches in length, and some as small as one inch in length have been found to be mature adults. The orangespotted sunfish is a member of the scientific family Centrarchidae and goes by the scentific name Lepomis humilis. The avid fishing enthusiast also knows this fish by such names as redspotted sunfish, pumpkinseed, dwarf and pigmy sunfish.

The fish is found in lotic watersof low gradient streams and lakes. The orange-spot prefers small and medium-sized streams to larger ones. It survives best in a slightly turbid to turbid environment, whether it be a pond or stream. The fish also enjoys a scarcity of aquatic vegetation. In lakes and ponds, it is found mostly in the warm lowland areas; very few have been found in cold-water lakes.

Orangespotted sunfish, like other fish, are most brightly colored during the breeding season, at which time it is very easy to distinguish between the sexes. The male is vividly colored, with body color an opalescent green, shading into a greenish blue toward the dorsal fin. This greenish-blue background is scattered with eight indefinite bands of distinct orange spots extending from the dorsal fin ventral to about the mid-belly region. Bellies of sexually mature males are light orange, blending into white. There is a small black spot above the eye, and traces of orange can be found on the dorsal, pectoral and caudal fins.

The body color of the female is olivaceous green and the spots are not as distinctly orange. The black spot over the eye of the male is not as prominent in the female. The dorsal, pectoral and caudal fins lack the orange coloration and are more transparent. The immature fish has a light olivaceous body coloring. The fins of the young fish are of a viridescent cast and do not have much color until they reach maturity. The eye of the immature fish is large.

The orangespotted sunfish is capable of reproducing from about mid-May until late September. The nest of the orangespotted is like that of other sunfish except that it is somewhat smaller. The nest is excavated by the male which, by using its tail and fins, removes small pebbles and sand to form a bowl-shaped pocket. The nest is approximately seven inches across and one to two inches deep, and is usually under one to two feet of water. The number of eggs laid depends on the size of the female. Females have been known to produce 50 to 4,700 eggs. Fertilization of the eggs is external. Once the eggs are deposited, the female leaves the nest and does not return. The male remains on the nest, continually fanning the eggs until the young are hatched. Fanning keeps the eggs from being covered by silt which would kill them. Also, the male is willing to fight any intruder that ventures too close to his nest. The eggs hatch in about five days, depending on water temperature. Due to the small size of this fish, predation is high and very few of these fish survive to become adults. Even as adults, they still are easy prey for piscivorous species such as pike and bass.

The diet of the orangespot consists primarily of small crustaceans and insect larvae. Approximately 50 percent of the diet is made up of insect larvae. Occasionally, small fish are eaten and some algae has been found during stomach contents analyses. The orange-spotted sunfish has been found to be very effective in the control of mosquito larvae when they happen to occur in its habitat.

Because of its small size and scarcity, even when full grown the orangespot has little or no value as a sport or food fish. However, when it reaches three to four inches in length, it will readily take a hook. Its primary value in fisheries management is its utilization as a forage food for the piscivorous species such as the largemouth bass and other predacious species. This sunfish has also proven to be a very valuable forage species for subadult largemouth bass when placed in hatchery ponds.

The orangespot is easy to raise in a hatchery environment and is frequently used as a test animal in pollution and other bioassay studies. Because of its small size, it is possible to have a mature fish for use in these studies. This small fish, though rarely taken by the angler, is one that once seen will be remembered because of its brilliant coloring. Although not common, it is found in small numbers in many of Nebraska's warm-water lakes and streams. There is no doubt about it, the orangespotted sunfish is one of the most colorful fish in Nebraska.

FIR & SUCH

(Continued from page 37)simple device became incorporated with an early Roman observance of New Year when candles and oil lights bedecked the homes. Then, exchange of presents, feasting, visiting friends, group singing and many other niceties were adopted from Russia, England, Germany, Scandinavia and numerous other countries.

Thus, many historical factors oi varying importance have been included into this august occasion, but regardless of a person's background, the Christmas tree is certainly a basic part of the American culture. Many forms are now used in addition to the original fir, from elaborately flocked artificial specimens surpassing in beauty even perfectly shaped natural trees to such unusual devices as yucca plants with small bulbs affixed to the end of each spiny branch. Even plain or painted tumbleweeds are placed in positions of honor in some homes, as are nude deciduous limbs and homemade creations fashioned from tape-wrapped wire.

Perhaps the trend away from real trees is good. While artificials may offend traditionalists, they are convenient in that they can be taken down, stored and reassembled the following year. And, they don't necessitate an annual toll on real trees, which are felled in remote areas and shipped months before the December deadline.

Of course, not all trees are ruthlessly ravaged from primeval forests. Many are grown on special plots just for that purpose. So great is the demand for such trees that they can be grown quite profitably. Others are excess growth from reforestation projects, cut and marketed for the Christmas season.

A certain segment of the population has not gone for either of the easy routes, neither buying a real tree each season nor investing in an artificial. They, for one reason or another, have preferred to trek into the wilds and chop down their own. In the old days, such actions were considered admirable, if not necessary. If you wanted a tree then, you just had to cut it yourself. Besides, it was a way to involve the entire family.

Cutting your own tree is still possible in some places, and it does put some individuality into an otherwise automatic seasonal response. After all, it is the custom to have a tree, and youngsters in the family are not about to be denied the fun and beauty when everyone else has one.

However, concern for ecology and preservation of the environment is growing, and chopping wild trees is a matter more apt to draw dark scowls than plaudits, no matter how noble the intentions. Plundering the wilderness for such frivolity can hardly be construed as constructive.

Tumbleweeds and yucca plants, however, elicit no such protectionist response. In fact, most landowners would be happy to lose a few, provided a large excavation is not left where roots used to be.

Cedar trees have lately come into use, too, partly because they are increasing in numbers, but also because they are attractive. One drawback is their similarity to cactus, for they have tiny barbs which become very evident when trying to reach around in them to hang lights or popcorn strings. Other techniques are to bedeck a living tree in the yard, or to fasten lights to the house itself.

Many other lesser forms of native materials also serve for decorative items, such as pine cones, milkweed pods, cockleburs, cattails and various berries. Wreaths are likewise made of unique materials such as computer cards or plastic sheeting. Nebraskans have a tremendous variety of trees and miscellaneous plants at their disposal. In addition to the full array of commercially available trees such as Scotch, Austrian, and jack pine, fir, and various spruces, there are artificial stand-ins made of plastic, wire and foil, or the natural substitutes, limited only by personal taste or creativity.

No matter which type of symbol is used, the Christmas tree and lights will probably be around for a long time to come. These tokens, seasonal as they may be, add considerable color and enjoyment to life, besides upholding a 15-century-old tradition.

GOOD OLD SALLY

(Continued from page 29)suggested, referring to ideal pheasant habitat directly south of his own rural Talmage home. Numerous rose hedges laced the acreage.

Soon on location, the hunters spread out and began working heavy cover to the south. Sally danced about, nose to the ground all the time.

The field ran uphill, and hints of huffing and puffing were evident as the men worked through the thick cover. Two cents would have probably turned the fellows back, but then the sudden, familiar cackle of a breaking ringneck brought things back into perspective. Ellis was quick to shoulder his coveted Model 12 Winchester and true to form for the fine old vintage gun, one booming shot finished the rooster.

"Hey, give em' a chance," Doc Webb hollered. "We've got to save some for seed you know."

Bud moved steadily toward Sally, fully prepared for the anticipated shooting. He was flanked on the right by Larry and on the left by Ellis and Merlyn. Finally, Bud was but a few steps away from Sally. The Brittany was still perfectly frozen. Then, like a dozen mini-explosions, bobwhite quail catapulted from the heavy cover. The covey went up on a perfect rise, and loud boom- ing shots broke the day's silence.

"Yikes!" Ellis shouted. "That quail found the hole in my pattern!"

"Beautiful!" Merlyn spewed after the guns had quieted. "It's not often a person walks into a setup like that. How did we fare?"

Sally delivered one plump bob to Ellis, and Bud leaned over to collect half of the double that he had scored. Larry had cashed in on another double.

"Just right," Larry answered. "It was totally perfect."

On the way back to the car, Ellis suggested they might take a small strip of grassland adjacent to a winter wheat field. "We've hit 'em in here before," he added to spice up his suggestion. As the party threaded through the fence, practicing perfect rules of gun safety, Ellis, a retired real estate man, stopped short. "Look at all the doves," he said, pointing to half a dozen mourning doves flittering ahead of him. "I've never been able to figure out why Nebraskans don't take advantage of such a prime gamester. The funny part is that millions of the birds are raised here, then migrate to Kansas and Texas where they are legal game. A great natural resource just flies out the window."

Ellis might have continued with his philosophy on the mourning dove, but a pheasant jumped up right in front of his nose and headed for parts unknown. Startled, to say the least, Ellis followed the bird and then lowered his gun. "Go on little hen and fly away. And, take good care of yourself and raise a nice big family next year."

As the foursome neared the end of the stretch of grass, the sun was putting out enough warmth messages to make the hunters uncomfortable. It was 11 a.m.; the mercury was at 40 degrees and climbing.

Then, only a few steps away from the fence that separated the grass strip from an adjoining pasture, Bud hollered to Ellis.

"Well, it was a good idea anyway, Ellis. You can't always expect to hit on a winner." Larry, a product of the University of Nebraska dental college who has been practicing in the Los Angeles vicinity since graduation, was just ready to join in when the whir of wings and the raucous song of a rooster changed his mind.

The ringneck lifted off behind the easy-going tooth carpenter, as Ellis and Bud commonly refer to their friend, and was heading straight away on a fence-line path. Larry wheeled and squeezed off a shot, but the pattern was a little behind its intended receiver. Larry pumped another round of his field load No. 6s into the chamber and touched the trigger again. The rooster was only a few yards away from safety, but those few yards decided the issue as Larry's second shot put the beautifully colored ringneck in the bag for keeps.

A mile-wide grin crossed Ellis' face as he politely asked Bud what he had said, explaining that he didn't quite understand him.

"Let's work a secret milo field I've got in mind and then break for lunch," Merlyn suggested. His comment met with zero opposition.

The fellows all loaded up, and with Sally riding shotgun, headed for Merlyn's milo field. The Talmage water tower gleamed in the morning sun a short distance away.

The hunting party arrived at the milo field, and its comparatively small size was probably an indication to its secrecy. Stepping from the automobile, the hunters each carefully chucked shells into their guns and discussed field strategy. "This field hasn't been harvested," Merlyn said. "I guess they're not going to, either, because the snow beat it down too much, and it just wouldn't be worth the effort. Besides, we farmers have to save a little grain for the birds. They should be in here feasting right now."

Before the group was even aligned and ready to go, three hens had already flushed. As they began working through the dense, fallen and matted milo, Sally's head could be seen periodically as she bobbed about in the field. About halfway through Merlyn's secret field, two roosters flushed right in front of the Nebraska host. He collected on both birds, as his lightweight automatic earned its keep with two perfect shots-a made-to-order double.

"No wonder you wanted to come here," Larry quipped, working through the heavy cover. "You had those birds planted here waiting for you, didn't you?"

Just then, a hen and two more roosters burst skyward. Larry shouldered his shot- gun and brought one of the birds home and Ellis's gun barked twice before he claimed the second bird for his game pouch. Before the four finished the less-than-five-acre field, two more hens flushed along with one more rooster that kicked up out of range.

"That makes a nice opening morning," Merlyn announced. "How about lunch?" A sandwich and a bowl of soup later, the party was back in the field for one more go at the ringnecks. The first stop after lunch was a cornfield on the very outskirts of Talmage. As the car doors swung open,^f.tie sportscaster came over the radio loud and clear as the "Big Red" University of Nebraska footballers were teeing up the ball for their annual hassle with the Iowa State Cyclones.

"Look at my shirt," Larry gleamed. The doctor's shirt was a blazing red. As Larry stepped into the roadside ditch and began to cross the fence, he gave a booming cheer for his Alma Mater. "Go Big Red!" he hollered. And, just as the doctor ordered, a ringneck sprang from the crackling dry corn. Interrupted and surprised, Larry turned for a shot. But this time he was caught completely out of position, and the bird winged his way to safety.

As the hunters fanned out and began working the cornfield, a noticeable wind came huffing out of the north, but it wasn't strong enough to worry about. The 55-degree weather overshadowed any wind.

Bud was just thinking out loud about how they should have worked the field from the south into the wind when his train of thought was shattered by the wild flushing of three pheasants, two hens and one rooster. His trained eye picked out the brightly colored male. He drew a bead and fired, and the bird folded in mid-air.

On the far left border of the field, another ringneck burst from his hiding place where Ellis was working. Fast on the shot, Ellis made it good. By the time the field was finished, Merlyn, too, had taken one more ringneck and Larry had scored on a pair of quail near an abandoned farm building.

Gathering back at the car, Larry shouted with excitement as Cornhusker speedster Johnny Rodgers had just raced 62 yards with an Iowa State punt —a touchdown and the first score of the game.

"That's some football team," Ellis added to Larry's excitement. "If there are two things this state excells in, they are football and hunting. In fact, now that I'm retired I do a darn lot of hunting, and I don't think any place is better than Nebraska. The football team speaks for itself."

Two milo fields later produced one more rooster pheasant and three quail. It was 3:30 p.m. when Merlyn threw out a suggestion to head back and dress the birds while the football game drew to a close.

The suggestion passed unanimously. The hunters checked in at Merlyn's house with 11 roosters and 12 quail. "You can't beat that," Merlyn beamed.

"No," Bud added, "I really don't think you can. And, you can bet that I'm plenty glad I've had the opportunity to join this Nebraska hunting bunch, because I'm convinced that you can't beat it."

where to go...

Indian Trails Circle tour

EACH YEAR, regardless of the season, healthy numbers of visitors trek to the wild reaches of the Missouri River between Gavins Point Dam and South Sioux City. For them, it is a chance to see the legendary river the way it was when Lewis and Clark used it as their highway on the epic expedition to explore the nation's interior. Those were the days when the Plains Indians could still call what is now northeast Nebraska their homes — ancestral croplands and hunting grounds that would soon host a flood of whites from the East. The memory of those people lives today in and around the small community of Ponca, some 22 miles northwest of South Sioux City.

Ponca residents are conscious of their historical heritage, true, but they are also conscious of the beauty their area of verdant rolling hills holds today. Regardless of the season, a panorama of natural beauty sprawls before the beholder, and there are any number of things to see and do throughout the region. A past so deeply ingrained with Indian lore is hard to ignore, and even a casual visitor will soon find himself visualizing things the way they were when native hunters stalked the ridges and hollows in search of food for the tribe; when squaws tilled the fields and produced precious clothing. Perhaps that is why Ponca's Indian Trails Circle Tour stands as such an attraction for sightseers and history buffs alike.

The tour begins at the Ponca Tourist Information Center in the downtown area. Since a portion of the route is over unpaved roads, travelers should keep a watchful eye on weather conditions. Rain or snow could mean the necessity for mud and snow tires. Otherwise, hinderances are few and far between and the trail will surely make for an enjoyable trip.

Head north on Nebraska Highway 9, the Ponca State Park road, and check your speedometer and record mileage for continuous reference. Two miles north of the Ponca Information Center, you will notice Indian Ridge, a nine- hole golf course on your right (No. 1 on the map) and the Old West miniature golf course on the left. Nestled among the Missouri River hills, both are open to the public daily in season. A sports camp on the bluff offers summer sessions in athletic training.

Just 200 yards beyond Indian Ridge Golf Course, at the first side road, turn left. Follow this well-traveled road for 15 miles and turn hard right where you will see a ranch home ahead on the left. Now traveling north, follow through two intersections. From the second, continue 116 miles and past Woodland School (No. 2) which will be on your left. Still in operation, the school provides elementary education for rural area students and is a prime example of the fast disappearing one-room school. Continue on, crossing through the farm with the home on your left and buildings on the right. Turn right at the fork in the road. Your path has just taken you through Woodland Drive.

Ahead, you will notice the hundreds

Continue along Elk Bottom and into Wildlife Haven (No. 4). There a T intersection will signal a left turn, and you should follow a winding road for 3% miles through this scenic, wooded bluff area. Watch closely for wildlife of many varieties. Wild turkeys and deer frequent this region, so go slow, look carefully, and enjoy the rugged rural drive.

Then, 1 1/2 miles farther on (be sure to keep right at all intersections), you will reach a crossroads. Turn right and go a quarter of a mile until you reach a fork in the road, then turn left. Continue on that road until you reach the first farm on your right —the entrance to Indian Hills (No. 5). You are welcome to follow the private road back one mile to the Missouri River where fishing, camping and guide service are available. Public fish fries and dancing are on tap from seven o'clock to midnight each Saturday in season. Details are available through the Nebraska Department of Economic Development.

Approximately 1 Vi miles north of the entrance to Indian Hills, you will crest a large hill where the 1880s Cemetery is on your left with a turnout to the right (No. 6). More than 100 years ago, the village of Ionia thrived on the lowlands below this bluff. The wild Missouri River cut the original townsite completely away, and today no trace of the village can be found. Cut into the river, too, was the Burning Hill as described in the Lewis and Clark Expedition log. This hill was thought to be a volcano by the early Indian tribes. You can again see the Missouri River with a beautiful view of its meandering nature, giving it a reputation of a monster swallowing farmland in this rich valley. Each year hundreds of acres of farmland are cut into the river. Emergency funding has been requested to halt the mass erosion, but nothing has been done to date.

The cemetery has served the needs of area families for more than a century. Feel free to look, but be careful to preserve this landmark. A number of young children's graves are marked by headstones indicating short life expectancies in the late 1800s. From atop Ionia Lookout, as the bluff is called, continue on the road straight ahead past the first set of farm buildings and through the first intersection to the forked road. Turn left and follow the main road about 3% miles into Newcastle. Stop just southeast of town where the Ionia State Historical Marker (No. 7) is located in Pfister Park. Then, turn left on Nebraska Highway 12 and back to Ponca complete the tour.

KUHLMANN-CATTLE KING

(Continued from page 30)designed to hold their myriad trophies. It has already been outgrown, with a good share of the silver won at the nation's biggest shows overflowing into the house. For many, trophies are just so many mementos to be tucked into dusty closets. For the Kuhlmanns, each trophy holds a host of memories and a lot of meaning, so every piece of silver is used. According to Orvil, it is pressed into service more often than most would think. The building is something more, too, than simply a gigantic sideboard. It represents an ever-growing business. A world map adorning one wall boasts seemingly hundreds of multi-colored tacks which mark locations across the nation and the world.

"Our cattle have gone to every state in the union and to such foreign countries as Canada, South America and South Africa." Impressive it is, and it may soon become more so because the Kuhlmann operation is changing. Shows are still in the picture and they are still important, with special emphasis going to nail the coveted grand champion slot at Denver's National Western Stock Show —the only plum to escape Kuhlmann stock so far. But the North Platters have proven their cattle's worth, and now they are concentrating on putting some of the finest cattle in the state on pasture around the globe.

"More than once, we've had inquiries about large numbers of bulls. Some requests have come in for as many as 100 at one time. Up to now, we haven't been able to fill such orders, but we're trying to build up our herds so that we can. When we were showing, we kept oniy about 125 animals on hand. In the last three years, our herd has doubled in size and we're up to about 250 breed cows right now."

When Orvil Kuhlmann talks cattle, he talks money. An order of 100 head could push the price into the thousands of dollars since the average price per commercial animal is around $750. Herd bulls —breeding stock-run from $1,000 to $15,000 each, with others going even higher. The ultimate coup to date came in 1956 when Kuhlmann sold one-half interest in a single bull for $50,000.

"Since the corporation that bought him was in Mississippi, it worked out quite well for both us and the bull," Kuhlmann grinned. "He spent the winters down south and the summers here with us."

Of course, it takes a great bull to bring that kind of money, and picking a prize- winning animal isn't all that easy. In fact, no one really knows if he'll win until the judge slaps him on the rump during the last go-around. But Orvil has a system and, though others may scoff at it, who can argue with success?

"We select show beeves by the time they are a month old. A lot of people say you can't tell what they will be like later, but a month-old calf is a healthy calf and will usually continue to develop that way. At just a few weeks, their ultimate body makeup is already established and they are unaltered by natural surroundings. They have never been sick and they are not influenced by the elements as they will be later. So, unless some accident causes permanent damage, the adult will come back to look just like the calf did at a month old, only on a larger scale, of course,' the rancher pointed out.

To insure that as little happens to a calf as possible, the Kuhlmanns perform most of their own minor veterinarian work. They are in constant contact with their stock and know how each animal should look and feel. On other ranches, where they rely on calling in a vet for most any problem, the calf can easily die before help arrives. Orvil, understandably, can't afford to count on distant aid when a valuable calf comes down with something and in his preparation lies one possible answer to a successful career —he keeps his cattle alive and well.

The Kuhlmann ranch has changed since the days when Orvil was a youngster just starting out. It is more refined now, and it is smaller. In 1961, he sold 25 acres of the original spread to the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission for a State Historical Park. Then, another parcel of land went to provide facilities for the Buffalo Bill Wild West Show and Congress of Rough Riders of the World when it was recreated. Orvil still has around 800 acres of the original ranch, though, and he is using them to their best advantage. Here, a prize bull can grow sleek on lush pasture grass and his owner can feel secure in the knowledge that his cattle are among the world's finest.

IRON SHOT

(Continued from page 34)"During December of 1969 we had 20 to 30 thousand ducks using the area," Sinn said. "It was unusual that we held so many birds, but the fall was mild and the water stayed open later than usual. That year we picked up 67 mallards and one shoveller that were still alive and attempted to hold them long enough to recover. How many dead ducks we didn't find in the sedge or that predators took I don't know for sure. Of the 67 mallards, only six survived the poisoning and were released."

That marshland on the Sacramento area had been shot over for 20 years or more. The accumulation of shot, coupled with the solid bottom, makes it a suspect area for annual lead-poisoning problems.

"As a rule there is not that significant a problem. Usually the hunters keep the ducks off the area until freeze-up," Sinn continued. "Some small loss occurs most springs, though, when the birds are undisturbed and loaf on the area for any length of time."

As early as 1936, attempts were made to solve the lead-poisoning problem. The failure of a lead-magnesium alloy shot that would disintegrate in water seemed to delay further search for an alternative to lead shot. With the emergence of the public's environmental conscience in the 1960s, the furor surfaced again. This time, though, the flames of concern reached into high places. Change now seems imminent, even though some important questions remain unanswered.

The National Wildlife Federation has filed a petition with the Secretary of the Department of the Interior requesting "regulations prohibiting the use of lead shot in hunting waterfowl and on federal lands under his jurisdiction where waterfowl are likely to ingest it." Essentially this will result in a court test that could ultimately stop the 1973-74 waterfowl season if a lead-shot substitute is not found and in production by then.

Lead has long been recognized as the ideal metal for shot in all respects except toxicity —it has a high density needed for maximum velocity and energy retention, is relatively low in cost, is easily processed and soft enough not to damage gun barrels and chokes.

Three new approaches have been taken in the attempt to find a workable substitute for lead shot: (1) developing a disintegratable lead shot that would fragment in the water; (2) coating the lead shot to prevent its absorption into body tissue; (3) replacing lead with a less toxic metal or alloy. The Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers' Institute, the Illinois Institute of Technology-Research, the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, other governmental agencies and various private organizations have been working on these and various other possibilities.

One test conducted at the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center by the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife attempted to test the effectiveness of various lead substitutes by feeding test mallards controlled quantities of the different alternatives and observing the outcome.

Plastic-coated (Teflon) lead shot proved ineffective in that it could not withstand the grinding action of waterfowl gizzards and the lead was ultimately absorbed. Mortality was nearly as high as with birds fed ordinary lead shot. A substantial portion of those mallards fed a lead-magnesium alloy shot developed typical signs of lead intoxication and died. Mallards fed copper shot did not develop any signs of illness. However, the cost of copper would prove prohibitive.

Soft iron shot was the most promising substitute and further tests were conducted to gauge its effect when ingested by waterfowl and its ballistic performance.

Test results were encouraging in some respects, disappointing in others. Some findings from this research now seem to be in conflict with other work done, and the issues have become the core of the controversy that rages today over the conversion to soft iron shot.

In a unique test where live but tethered game-farm mallards were released along a prescribed course in simulated flight and mechanically shot to insure direct hits, iron shot was found to be ballistically the equal and, in some cases, superior to conventional lead.

Several drawbacks of soft iron shot also came to light, though. Many of the mallards experienced massive hemosiderosis of the liver when fed soft iron shot. The cost of producing soft iron shot would also present some problems. The soft iron used in these tests was produced on a costly laboratory basis from steel wire, a process unsuitable for large-scale production. Development of economical manufacturing techniques for soft iron shot would require techniques not currently available. Rapid barrel erosion and choke deformation also proved threatening. One test conducted in Canada showed a 20-percent increase in the diameter of the choke portion of the barrel after 100 rounds. A similar test conducted in the United States indicated a 10 percent choke expansion after 40 rounds.

The validity of these negative aspects of soft iron shot have been taken to task recently.

Thomas L. Kimball, executive vice-president of the National Wildlife Federation, addressed the question this way. "The information we already have indicates that whatever barrel abrasion and choke damage occurs varies widely between different models oi shotguns. For obvious reasons, the manufacturers are extremely reluctant to identify publicly the models which perform relatively badly. But this is a management problem for the manufacturers rather than a reason to continue using lead shot. Most shotguns used by hunters today could easily be performance-rated for soft iron shot, either by the manufacturers or the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife. If particular models consistently perform badly, the manufacturers should publicly identify them and suggest that owners purchase other shotguns for waterfowl hunting. After all, we gave up Damascus steel when heavy loads were introduced years ago

On the subject of difficulty of producing soft iron shot economically, the Wildlife Federation produced the following statement: "At least one company, the Superior Steel Ball Company, has affirmed that it has the capability of mass-producing soft iron shot to the sporting arms and ammunition manufacturers specifications, both reliably and economically."