NEBRASKAland

November 1972 50 cents 1CD 08615 Who owns the Missouri? Turkey tests archer's skill How to improve your garden with compost

For the record... The Giveaway Game

Hunting and fishing are privileges to be enjoyed. They are not inalienable rights. As privileges, these sports are financed by special taxes and permit fees assessed directly against those who pursue these activities.

It was through the efforts of hunters and fishermen themselves that permits came into being. Dedicated sportsmen saw the need for management programs for wildlife. They responded by requesting, in essence, that licenses be mandatory to finance that management. As a result, state fish and game agencies came into being and assumed the caretaker role over wildlife and the things that wild creatures need to survive. It was a farsighted and selfless thing that those sportsmen of yesteryear implemented.

These license fees pay for a lot more than meets the eye. They finance all wildlife management, except that performed by the landowner on his own land. But, they also pay for a vast variety of other projects not directly related to fish and game. These fees underwrite the costs of a range of ac- tivities from protection of the state's waterways from pollution to banding projects on such species as sandhill cranes.

A broad segment of society benefits from the dollars contributed by sportsmen. Many non-consumptive users, such as bird watchers, hikers and shutterbugs ride the coattails of the permit-buying sportsman. Their hobbies are enriched as a direct benefit of the dollars spent on fish and game management, and yet they bear no share of the financial burden.

Now, however, the good that has evolved over the years is threatened. The American idea of handouts to a variety of worthy causes has encroached on much-needed, fish and game revenues. There is an alarming trend toward giving free hunting and fishing privileges to more and more people, with no allowance for replacement of lost funds.

Every time another group is added to the growing list of eligible recipients of free permits, money available to carry out needed conservation projects declines. In reality, then, such permits are not really "free." The cost lies in projects not completed, work left undone.

There are hidden costs as well. Who can assess the intangible cost of opportunities that go undeveloped? What is the cost of the inability to introduce a new species of game because of lack of funds? What is the cost of the failure to build and maintain adequate fish hatcheries? What is the cost in respect for the law when there are not enough funds to hire conservation officers?

If Nebraska is to manage its wildlife as it should be managed and explore its opportunities, someone must pay the bill. It is not really fair to shift the burden to other sportsmen who must still buy permits through an increase in their fees.

What, then, is the answer?

If the granting of free hunting and fishing privileges to the elderly, certain veterans and others is worthwhile, then those privileges should be the gift of all Nebraska citizens, not just hunters and fishermen. Revenue lost through free permits should be replaced with dollars appropriated from the general fund. In that way, all Nebraskans would have a part in honoring their aged and their veterans. Now is the time for action. If Nebraskans would like to see this imple- mented, they should speak now. We would like to hear from you. Send your comments to me at the Game and Parks Commission, P.O. Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503.

Speak Up

NEBRASKAland Magazine invites all readers to submit their comments, sug- gestions, and gripes to Speak Up. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters. — Editor.

PROBLEM PEOPLE-"Hitler killed the Jews; terrible some of the ways he did it, and some were killed for the enjoyment of his men. Nero killed Christians; terrible, the way he did it for pure enjoyment. People kill animals. Terrific! Run them down and shoot the best of the herd.

"Now if it were in defense. ..but what do animals do to hurt us? (Farmers: I understand to a point the troubles with animals eating your livestock and crops.)

'The article Zigzag Zonk in the June issue of NEBRASKAland is pathetic. Anyone who can laugh till tears run down his cheeks while a rabbit is run down by a runaway tire is a person who would have been a German or a Roman.

'"Man's new devices,' the poor rabbit must have thought! Tragedy is always funny as long as it isn't ours. People, some no more intelligent than the animals they kill, are the ones who are slowly killing off their own species. Realize it or not, life works in cycles. Why is it, then, that people laugh at the death of a completely pacifistic animal? Now there is the tragedy —people." —Tim Fickenscher, Gothenburg.

HUMORLESS-"l could find no humor in the article Zigzag Zonk written by Donna Lu Dufoe and published in the June 1972 issue of NEBRASKAland. The idea of writing a story on such an unfortunate incident for the sole purpose of getting a good laugh from it is, at best, gruesome. I am one who loves all animals, and to witness the painful death of one would not prompt me to laugh and joke about it. Mrs. Dufoe undoubtedly feels nothing for defenseless animals, illustrated in the way she enjoys hunting antelope. I wonder, did she also enjoy pulling the wings off flies when she was a child?

"Nebraska is fortunate to be blessed with abundant natural resources: a good rich soil which produces fine crops, many clear lakes and streams, and a thriving wildlife population —at least up to now. Long ago, settlers shot any wild animals they could find to make a meal. This was excusable. They needed the meat to live. Today, our hunters gun down ducks, deer, antelope, rabbits and so on for the sheer sport of it. There is no need for it. But it goes on. And now, I look out my window to see young boys, nine and 10 years old, smiling and laughing as they knock sparrows and robins out of the trees with their BB guns. Looks like a great future for our wildlife, doesn't it?" —Betsi Coughenour, Grand Island,

NO APOLOGIES-"l don't think NEBRASKAland owes Mr. Wooster an apology (Speak Up, June 1972). If I were gifted enough to do beautiful work I ike the wooden duck decoy, I would be honored to have it in a magazine, not worrying whether I got glory for it. I think Mr. Wooster acted or sounded a little immature in his thinking." — Hubert McClory, Jr., Waterbury.

THE WHOLE THING - "During World War II, it wasn't easy to give elaborate dinners because of meat rationing. Dr. Edwin Davis, professor of urology at the University of Nebraska College of Medicine in Omaha, accomplished it in a unique way.

"He gave a large dinner party at his lovely home in honor of his brother, a naval admiral, and Colonel Al Gordon, who was supervising the building of the B-29s at Wichita, Kansas. A beautiful buffet dinner with mounds of broiled fowl was served. Not identified, I guessed they were pigeon and many of the guests returned for seconds. At dessert, the waiter in charge showed each table the head, wings, and tail of a crow. We all ate crow and enjoyed it.

"Dr. Davis, an avid sportsman, had been shooting a few days before with a champion crow caller. They killed several hundred crows which made for a very successful dinner party."-Dr. A. E. Bennett, Berkeley, California.

WRONG STATE-"The article, Fort McPherson, in the July issue of NEBRASKAland is very interesting, but there is a slight geographical 'goof on page 63. You wrote: 'finally reaching the Arkansas River in Texas.' "The Arkansas crosses part of Oklahoma and then goes into Arkansas until it empties into the Mississippi. It does not touch Texas '-W. R. Johnson, Ardmore, Oklahoma.

RED AND WHITE-"I see that once again the July issue of NEBRASKAland has an Indian theme for its hostess of the month. I am very unhappy to see that we have to use a white girl dressed up to look (?) Indian. In August 1968, I found that you had done the same thing, but the following August, you chose to put a real Indian girl, who was quite lovely, into the magazine. Why the backslide to the fakey Indian and the fakey clothes?" —Christine Shell, Grand Island.

GET IT RIGHT-"We are writing this letter in regard to your article Anthology in Acetate, in the July issue. We were very displeased at the way the author presented only one side of the story. All he could write about was the death of a wild river, and about all the fauna that would be destroyed. Granted, there will be some life destroyed, but not to the extent that the author portrays.

"We have lived here all our lives—18 years—which is not too long compared with some of the people; but until the past 10 years nothing was known of this parade of photographic possibilities' except to the people in the area. We feel that the proposed dam will not destroy all of the beauty of our canyon, but will make it all the more beautiful. Beauty is not worth anything unless it can be seen, and that is what the dam will do. It will bring people to the area to enjoy its beauty.

"And lastly, the author is somewhat misinformed. The picture showing Jim Longman standing on some rocks is not the real Rocky Ford. Its true name is Mill Dam. Rocky Ford is located about three miles upstream. And we would also like to point out that the spelling of our town is not 'Nordon' but 'Norden.' We feel that in order for a person to speak of an area, he should at least know the correct names and spellings of the various points included." — Neil McCormick and Audrey Frauen, Norden.

GOOD CHOICE- "I think the recent selection of the cottonwood as the state tree was a good one.

"Not long ago, my husband and I, our grandson and a friend had the opportunity to see a very large cottonwood on the Falkington property five or six miles south of Inavale. It measures 38 feet around the trunk and is truly a beautiful tree. I would like to know if there are many large cottonwoods in Nebraska."-Mrs. Otto Betke, Ravenna.

Rather than listing locations which might be antiquated, NEBRASKAland would very much like to hear from readers who know of sites which have large cottonwoods. — Editor

ANOTHER OPINION-"If we had to depend on Glenn Bauer's brand of hunting (Speak Up, July 1972), there wouldn't be many coyotes killed. In the last five years, we have killed around 700 in northern Gage and southern Lancaster counties. Some of us hunted with dogs, while another bunch chased them down and shot them with high-powered rifles.

"If Mr. Bauer had a farm and let his chickens run loose, he would have a different NEBRASKAland opinon of the coyote. I know I've lost a lot of chickens and ducks to them and raccoons, so please don't run down the way farmers have of keeping these chicken, duck and calf killers under control." —Walter Moser, Hickman.

WHY? After reading Mr. Lawrence Hel busch's letter in the July 1972 Speak Up column, I wondered why anyone would kill a nice wild animal like the albino skunk. I am sure the skunk was doing no one any harm.

"Perhaps Mr. Hellbusch can explain why this animal was killed, since anything so rare should have been saved." —Jesse E. Dixon, Emerson.

GOOD LUCK-"On February 20, Hap Tur- ner and I caught several large northern pike from Pelican Lake on the Valentine National Wildlife Refuge. In the enclosed picture, I'm the one on the left. The fish I'm holding weighed 131/2 and 12 pounds after nearly two hours out of water. Hap is holding a total of 25 pounds of fish." —Ivan Roth, Valentine.

DOG FOOD —"Since my parents were pioneers in Nebraska, they learned early how to keep eggs, vegetables, and meat during the winter.

"One thing that father became famous for was his dried beef. After killing a beef, father would cut choice chunks from the bones —50 or more pounds of the lean meat. This was put into a brine for so many days and then hung in the smokehouse. Finally, the meat was ready to be hung from rods above the cook stove. Soon it would be ready for us children to sample.

"One winter father had a horse die of distemper and since it was a problem to feed the hounds he kept for coyote hunting, fa- ther strung the horse meat on a wire and threw it over the hay rack to freeze and dry.

"One day, some high-toned men from NOVEMBER 1972 town came to see father and while they waited for him to come from milking, they not only spied the horse meat, but sampled some of Murphy's famous dried beef.

"They were chewing on the meat when my sister happened to go by, so one of the men said, 'I hope you don't mind us sam- pling your father's dried beef. We have heard about it for years, but this is the first time we've had a chance to taste it

"Have all you want,' my sister replied.

'That is dog meat from one of the horses which died.'

"My sister went on her way. The next time she saw them they were at the well washing out their mouths." —Mrs. J. L. Armold, Callaway.

TOP CALLER —"I have been an avid reader of NEBRASKAland for several years and have been wondering if you would like to give some recognition to a young Nebraska man.

"The winner of the 1971 World Championship Duck Calling Contest at Stuttgart, Arkansas, was a Nebraskan. Larry Largent, representing Nebraska, and his brother Rod, representing Missouri, placed first and sec- ond respectively in the competition." — Mrs. E. Dale Largent, Overland Park, Kansas.

VERY INTERESTING-"The March 1972 issue of NEBRASKAland was my introduction to your magazine. I found the articles to be very interesting, especially Partner In Destiny by Leonard Sisson. It bespeaks the serious truth and urgency of man's realization that he does share the destiny of all nature and that he must move soon to halt destruction and to restore and perpetuate mankind's wonderful gift of nature before it is too late." —Grace M. Peters, Portland, Oregon.

HOW ABOUT THIS-"In the March 1971 issue of NEBRASKAland, I noticed a statement on page 66 (Outdoor Elsewhere) about how a hiking trail had been closed because trail bike riders had been using it. Since the trail crossed private properties, landowners most likely didn't like the racket, and I can't say that I blame them. But, it seems hardly fair that Nebraska doesn't provide some trail somewhere for bike riders and snowmobilers.

"How about beside the Interstate highways? Trail bikes, snowmobiles, bicycles, go-carts and other slow-moving vehicles could use one side while horses, horsedrawn carts or wagons, or oxen-powered vehicles could use the other.

"Don't tell me it will cost too much money —I already know that. There would have to be double fences on both sides so some fool horse didn't wander out onto the highway. But the noise is already there, so it wouldn't bother anyone that much. And the rest areas could benefit although a few more outhouses might have to be set up here and there. Cafes and service stations could start (Continued on page 12)

SHOW YOUR COLORS

Nebraska law requires that, while hunting deer or antelope with a firearm, you wear at least 400 square inches of hunter orange on your head, shoulders and chest.Simple yet phenomenal, this procedure will rescue bad soil

How to: Compost

WHAT YOU EAT is what you are. Much of the time, though, you really don't know what you're eating. Concern over the effects of pesticides, herbicides, growth stimulants and other chemicals has been growing in recent years, and with good reason. Many people have decided that ingesting even small amounts of these poisons should not be required as a penalty for living in an age of technology.

Demands for pure food have been heard for quite a while and, despite assurances from chemical companies, an increasing number of growers are beginning to listen. Thus, organically grown foods are appearing in greater amounts everywhere. Perhaps a totally organic concept is too extreme, but soil experts claim a lot of lost ground must be regained to restore the health of the nation's soil.

Despite what is done in the agricultural industry, there is something the home gardener can do to insure uncontaminated fruits and vegetables in his own plot. Organic gardening practices can easily be carried on at home, enriching the soil while also improving plant growth. Nowhere, it seems, is there soil which cannot be improved. And, the most dire need is that for humus.

Ideally, the usual variety of vegetables can be sown, grown and harvested without using chemical poisons, yet without heavy damage from disease and insects. Vigorous, healthy plants are actually avoided by most insects, as bugs prefer weaker greens which are higher in carbohydrate and lower in protein content. And, in plants just as with people, diseases befall healthy specimens less frequently than puny ones.

Composting and mulching are two basic elements of good gardening, though these two practices can be one and the same. O. A. Moore of Lincoln, who is an avid organic gardener, per- forms what is termed sheet composttngr This is a year-round project, yet involves little actual labor.

In the summer and fall, grass clippings, twigs, stalks, leaves and other such material is gathered and piled in a bin where it is kept throughout the winter. If ground up, so much the better. In spring, after plants have come up, this material is spread over the entire garden surface to a depth of several inches. It serves to retard weed growth, preserve moisture and provide nutrients to the plants. In fall, the garden is thoroughly plowed or rototilled, mixing the mulch into the soil, and completing the cycle.

In addition to this process, Mr. Moore also has a compost cabinet into which he dumps all food scraps. These are covered with dirt and allowed to break down by bacterial action, then taken out the bottom by means of a shaker. This operation is continuous, adding to the top and removing from the botl with the extra being a rich, nourishing food for the yard.

Some stubborn, hungry insect pests NEBRASKAland In sheet composting, summer mulch is turned under in fall for humus may still attack prized plants regardless of their condition, but there are means of getting rid of them safely. Several preparations on the market will kill or discourage foliage-eating critters without any danger to humans or the environment.

Growing plants without depleting the soil, without contaminating the air, ground or water, and without any extra effort may seem like a pipe dream, but proponents of ofgame^afdening say it is routine. On top of all that, it is cheaper. Adding the satisfaction of doing things right, it is hard not to be a convert.

Mr. Moore is still convinced after 20 years that organic gardening is the answer. His garden plots have what he terms good sponge. This means the ground is not hard and compacted, but loose and porous, capable of holding maximum amounts of rainwater. Chock full of earthworms and humus, the soil is so loose that an iron rod can be easily shoved 1Vi feet into it. Try that in your average garden —poking a rod in just three or four inches would be an accomplishment. Yet, Mr. Moore's soil is not boggy —it is firm to walk upon and firm enough for any type of crop, including tall corn.

Perhaps knowing that the soil is being enriched even more each year is the best argument in favor of the mulching-composting method, but there are many. Hopefully, more people will adopt these principles of conservation and ecology to help reverse the modern trend of taking from the land without giving back. Instead, it should be treated as a partner. It is, after all, the reason life can exist.

NOVEMBER 1972

SPEAK UP

(Continued from page 5)selling oats, hay and a little harness repair and blacksmithing like snowmobile repairs and parts.

"The trails should be just left bare so people could rough it in the true pioneer spirit. Besides, it's cheaper."—Mrs. Larry Crouse, Aurora.

PAINTINGS SOUGHT-"Could you please tell me if you have ever used any of Andrew Standing Soldier's paintings in NEBRASKAland. I saw quite a collection of his work at the Chevrolet garage in Gordon and would like to know if there are any for sale or if there are prints available." —Lucille R. Lewis, Ulysses, Kansas.

To date, NEBRASKAland has not featured Andrew Standing Soldier's artwork, and the only collection with which we are familiar is the one Mrs. Lewis saw in Gordon. Anyone with knowledge of others may contact her at 614 North Sullivan Street in Ulysses. — Editor

BIGGER THAN LIFE - The spring of 1964 was filled with showers, so by mid-summer, field corn was waist-high, and our sweet corn was just about ready. As usual, we were beginning to have trouble with raccoons in our large sweet-corn patch, which fed most relatives and friends. The trouble meant that it was once again time to set out our three raccoon traps. We set the traps in an open area of a row, tying down the trap to the bottom of a sturdy cornstalk with bailing wire. As bait, we simply used aluminum foil spread over the trap.

"For about the first week, we caught 1 or 2 raccoons each night. Then, one morning, my older brother and I got to the third trap and ran into some corn that was completely flattened in an area about 10 yards square. We looked around for the trap for about 15 minutes, but were unable to find it. We were both a little excited, so we went back and told the rest of the family. After some discussion and evaluation, the decision was that whatever was caught in the trap was big enough to tear down part of the sweet-corn patch to get loose, and finally dragged the trap, wire, and cornstalk away with it. After following the path of knocked-down corn and weeds for about half a day, we decided to give up.

"Talk went on about the incident and several other times the next day we tried to track down the missing trap. On the second day, our dog, a sandy cocker spaniel, began barking at something behind our machine shed. Tangled under a pile of old boards behind the shed was the trap, clinging to one of the biggest raccoons anyone in the area had ever seen. The granddaddy raccoon was in very bad shape and near death. After putting it out of its misery, we weighed the raccoon at just short of 25 pounds."-David Dent Otradovsky, Valentine.

Parasites, Predators and Pathogens

For decades, man has been pouring deadly chemicals into his environment, and now the dangers are coming home. But a lesson taken from nature could stem our tide of extinction

BEFORE MAN BROKE the sod to sow his crops, the prairie was at equilibrium. Organisms of decay and prairie fires returned to the soil what grasses had taken from it. The prairie was a community of mixed composition; no species of grass or herb held domain and insects that lived at the expense of a plant were scattered randomly with their hosts. No part of that community gained ascendancy over another. When one organism flourished its natural enemies also increased and balance was restored.

Man changed that, though. His plow broke not only the sod, but the equilibrium as well. Unlike other plant and animal populations, he had yet to establish his bounds. His numbers spread over the land and became increasingly dense. The mixed grasses and herbs of the prairie were not suited to his agrarian background, so he planted the prairie to grains and fruits to support his kindred.

Acre after acre he planted to one grain or fruit. Within this monoculture, insects thrived, too, and made vast inroads on his crops. Soon it was a simple matter of survival of the strongest—insect or man.

For decades, man had little success controlling the insects' burgeoning numbers and destruction of crops. But then came the 1940s and chemical insecticides. The synthetic age of chemical farming and the control of cropland pests had arrived. Within a relatively short span of years, the environment showed definite signs of stress. Now, once again man seems threatened, this time by the monster he created.

Wildlife was the first to show the ailments of a diseased environment. Birds of prey began declining. Isolated reports of fish kills became more common. Insecticide- resistant strains of cropland pests developed. All were early signs of imperfect and dangerous use of chemicals- many of them insecticides.

Newer, reportedly less-harmful chemicals were produced and employed with success. But now, even the safety of these newcomers is in question. Armchair ecologists began to demand overnight discontinuation of all chemical pesticides, regardless of the effect on agriculture. To these people, economic chaos is a reasonable price to pay for a restored and chemical-free environment.

On the opposite end of the spectrum is agri-business, a less homogeneous group than the former. Most would give up the use of chemicals if an alternative control were offered —one that would enable them to maintain high yields and continue to compete on the market. Some chemical manufacturers realize high profits from the chemical industry, and change would be expensive —development of new controls would mean declining their profits.

And so the state of affairs stands today. Some ecology interests demand the (Continued on page 50)

The Strategy of Strunk

Flood, drought ravaged the Republican River Valley for years. Then McCook newspaperman stepped in

DAMS HAVE ALWAYS been surrounded by controversy. Rare indeed is the impoundment whose waters have not been troubled at some point in its planning, construction or use. Dams face many foes. Property owners in the affected areas regard with suspicion the autonomous outsiders who have the authority to usurp their carefully nurtured lands. Preservationists argue for the integrity of the scenic countryside scheduled to become the lake's bottom. Taxpayers, with an eye on the project's finances, dispute the often marginal cost-benefit ratios.tFactlons clash over the uses of the water —power or irrigation, navigation or recreation.

Dammers have always been damned. Today, criticizing the Corps of Engineers or the Bureau of Reclamation or similar dam-building agencies has become a national pastime. Neo-conservationists deplore dams regardless of the issues, and wage campaigns just short of militancy with anyone who even suggests rearranging a part of the landscape.

Yet in southwestern Nebraska a series of dams have been constructed over which there was relatively little wrangling. Somehow the need for these impoundments was apparent to almost everyone. What was unique about the Republican River Valley which made possible the creation of these reservoirs? Who or what made the critical difference in this particular area's accomplishments?

The success of the dam-building programs of Nebraska's Republican Valley came from the fortuitous combination of two different factors. One was the valley's intimate relationship with the twin terrors of the 1930s —drought and flood. The people were ready for positive action. Dams which could provide water for irrigation and at the same time prevent floods could hardly be con- demned; they were welcomed. Opposition from area residents was virtually nonexistent. Indeed, most were enthusiastic. One valley farmer stated at the time: "I don't want to continue to live here if the river isn't fixed." And another: "The sooner they get water over the top of my house, the better I'll feel."

The other vital factor was Harry Strunk and the Republican Valley Conservation Association. "Conservation" is not a new word to southwestern Nebraska. Farmers and ranchers of the prairies learned their environmental lessons the hard way

during the 1930s. While nature's harsh tutelage could have easily broken the spirit of lesser men, Harry Strunk was an apt pupil who toughened under the challenge before him.

Strunk was a newspaperman, a fighting journalist who knew how to get things done. The lean, caustic founder of McCook's Daily Gazette had picked up the theme of conservation early in his career. His paper was started in 1911 when he was but 19 years old. And, it was also in 1911 that Harry Strunk resolved to start the fight to control floods and bring irrigation to the arid areas of the Republican Valley region.

A survey was made that year to study the feasibility of diverting water from Frenchman Creek, a tributary of the Republican River, to irrigate dry land north of McCook. The project fell through. But Strunk had had his revelation of what was possible, and his crusade began.

In 1928, the Twin Valley Association was formed. Strunk organized citizens of the Republican and Frenchman valleys, who then pressed for the kind of programs they knew were needed. A year after its formation, the association sponsored in McCook one of the largest flood control congresses ever held. Governors and officials of 14 states attended. Soon thereafter, laws began to come from the capitols which laid the groundwork for water use and control projects.

Financial difficulties spelled the end of the Twin Valley Association in 1930. But in the dust-bowl years that followed, Harry Strunk continued to use his paper to advocate reclamation and irrigation. His belief that the famine-feast cycle of 18 NEBRASKAland prairie weather could be broken was the keystone of his conservation philosophy.

But Strunk's words went unheeded. The ruinous drought of the early '30s was matched only by the devastation of the 1935 flood. The untamed river roared through nine counties of the Republican Valley, claiming rich topsoil as its own, along with more than 100 lives. For a few brief weeks, the nation's attention was focused on the stricken area. But as quickly as the flood waters came and went, so did the sympathy.

Outraged at the apathy and casual acceptance of the tragedy by federal agencies, Strunk renewed his campaign. In October, after the flood, he organized a Reconstruction Jubilee. Dignitaries at the three-day program included then vice-president Charles G. Dawes and the governors of Nebraska, Kansas and Colorado.

In the late '30s, Harry Strunk continued to plug for the development of irrigation in his valley. Finally, in April of 1940, things began to happen. But from the standpoint of landowners in the upper Republican Valley, they were the wrong things.

The announcement that a Corps of Engineers dam was authorized for the Harlan County area was met with little enthusiasm by upstream residents of the valley. While the $22 million dam would certainly benefit a portion of the Nebraska-Kansas area, it offered nothing in the way of protection for that part of Nebraska west of the proposed dam —the area which suffered most in the 1935 flood. The dam, to be located at Republican City, would leave the upper Republican as vulnerable as ever to (Continued on page 55)

Lakes which devoted editor pushed today host thousands of visitors

The Unrock Festival

FROM THE BEGINNINGS of civilization until the Industrial Revolution, man's culture was primarily agrarian; his sustenance dependent on the things he grew. Land was his prime possession and all other acquisitions related to how well it produced. From the earth he gathered materials to make tools which he used to build houses. Gradually his tools became more sophisticated and the things he made more decorative. Artisans and craftsmen emerged from this culture, but man still worked, basically, with his hands.

Then came the Industrial Revolution, and man learned to work with machines instead of tools. The scythe gave way to the threshing machine and then the combine. Spinning moved from jennies and mules at home to the mill. Mass production took over where individual handiwork had been before. Calculation developed from hand-operated adding machines to modern computers which work too fast for comprehension. Emphasis shifted from rural to urban life —from agricultural to industrial, and then technological life.

But throughout this development there has remained an awareness of early times when man was self-sufficient. Even (Continued on page 56)

Though furor has subsided, de facto channelization still threatens to deface last wild stretch of the Missouri. Only from Yankton to Sioux City does river resemble unbound days. Man's progress may claim this remnant, too.

Who owns a river?

DOES THE PERSON whose land is on its border own it? Can one man own a river? Can a state own a river? Does any government have the right to own a river? Or does it belong to the people? And who is to decide if a river is to be changed? Who dictates the destiny of a river? A landowner? A group of landowners? A state? A governmental agency? Or the people?

Who will be the one to decide if a meandering strand of water will be stabilized into a ditch to drain innumerable watersheds? And who will tell the children that this river, the route of our country's explorers and frontiersmen, a historical legacy, was channelized for profit? Does a man build on the beach and expect

NOVEMBER 1972 23

the tide to cease? Should we expect a river to stop washing its flood plain because man chose to farm it?

Who will be responsible for the fish and fowl that disappear with channelization? Can we expect a channel to support the game and nongame birds that the backwaters and sandbars now hold, or fish to reproduce and thrive in a tube of turbulent water? Who will explain to the fishermen where the bass and bluegill have gone, or why they catch fewer walleye and catfish? Will waterfowl rest or feed in nine feet of water? Will shorebirds choose a tangled mass of undergrowth over sandbar shallows? Who will answer the sportsmen and naturalists?

And who will pay the bill? Will a handful of landowners pay for channelization? Will the towns that are periodically flooded pay? Or will the taxpayers feel the gouge? Are governmental agencies self-perpetuating and perhaps self-serving now? Is it their river, a plaything to be manipulated, a force to be tamed, another identity to be impersonalized? When the river is gone who will answer these questions? After all, who owns a river?

Haunted

There is no such thing as a ghost, we say, refusing to admit that there might be some things that man was not meant to know

IN THE MORNING of October 3, 1963, Mrs. Coleen Buterbaugh hurried across the campus of Nebraska Wesleyan University in northeast Lincoln. At 8:50 a.m., the university was already bustling with students moving from one class to another and employees going about their business. Mrs. Buterbaugh paid little attention though, focusing instead on the task at hand. She had been dispatched to find Dr. Tom McCourt, a guest lecturer at Nebraska Wesleyan. She was on her way to his office.

Entering the C. C. White Building, Mrs. Buterbaugh made her way through the corridors to the office door and stepped through. She later recalled a smell of.very strong, stale, musty air that hit her in the face "as if someone had turned on a gas jet and let the odor escape," according to later newspaper accounts. All windows in the office were open, though, and Mrs. Buterbaugh had the feeling she was not alone. It was then that she saw a very tall, slender young woman with black hair wearing a long-sleeved white blouse and a long, ankle-length brown skirt. With her back turned so that her face was not completely visible, the woman was reaching into a drawer of a filing cabinet, Mrs. Buterbaugh recounted.

Feeling that there was a man sitting at a desk to her left, Mrs, Buterbaugh turned, but saw no one. She did, however, glance out a window, noting that the landscape outside seemed very old. None of the familiar landmarks or buildings she knew were to be seen. It was as if Mrs. Coleen Buterbaugh had stepped back into a period that had long since passed.

Bewildered if not frightened, Mrs. Buterbaugh retreated to tell her story to others. Though no one else had seen the tall woman, her description was relatively familiar to the older members of the faculty. Finally, a photograph in a Wesleyan yearbook provided the figure's identity. Mrs. Buterbaugh was sure that the figure she had seen was that of Miss Clara Mills. Records indicated that Miss Mills had been a music teacher at Nebraska Wesleyan University for 28 years, beginning her career in the days when University Place was still a town separate from Lincoln. She lived alone and walked to the campus every day, just as she had on April 12, 1940 —the day her students found her dead in her classroom.

On the morning of October 3, 1963, Mrs. Coleen Buterbaugh and Miss Clara Mills met, despite the fact that the latter had been dead for more than 23 years. Mrs. (Continued on page 57)

Unwary Quarry

Fleet of foot but short of memory, turkey offers ideal subject for sneaky hunter

GLOOMY, OVERCAST skies and periodic spurts of light snowfall surrounded Gary Galloway as he crept nearer the silhouetted tree which had to contain dozing turkeys. Two inches of fresh snow cushioned his steps, making it almost easy to approach the big birds. But the poor morning light on opening day of 1971 's fall wild turkey season left something to be desired. '

Only a few hundred yards from the Niobrara River near Valentine, Gary had scouted the area the evening before and knew the birds would be roosting in the trees next morning. Now, the tall, rangy, left-hander fingered a readied broadhead as he drew even closer.

There were the birds, and Gary's stalk had ended. He was still a good 40 yards from the nearest of the now-restless birds, so the time had come.

Drawing the arrow, the 50-pound-pull bow arched familiarly. Picking one of the plumper birds, hopefully a torn, he let the arrow fly. Although it was an inches-near miss, the critter was startled into action, and in seconds the entire mob was in noisy, confused flight to safety. Mumbling rather discourteous reprisals to himself, Gary walked quickly to retrieve his arrow now jutting from the snow.

"Til give them a few minutes to round up the foot soldiers," he mused to himself, although he was anxious to take up the pursuit. The new snow would simplify trailing once the birds' landing area was located. They might not all put down in the same spot, but they would bunch up in a few minutes, and go about the daily task of grazing. It was always fun to watch turkeys stroll along, picking up goodies on the way, similar to the way cows would do —picking and poking around, lowering their heads often for grass or seeds.

Once moving, they might cover ground rapidly or they could dally along, depending on the availability of food. The snow had covered a lot of feed, so today the turkeys would probably set a faster pace than usual. Even so, Galloway should be able to keep close tabs on them.

The birds would not be overly alarmed —they seldom were. Compared to stalking a skittish whitetail, turkeys were child's play. Although their eyesight was plenty good, they didn't seem to be extremely wary, 34

Following quickly now, Gary saw his quarry on a hillside ahead. Hurriedly, but carefully, he worked toward an opening in the trees. Through it he could see some of them passing. At about 45 yards he saw his chance and took a shot at a running bird. Another miss. There was still no indication that they were spooky; not nearly so much as had he been using a shotgun.

Following their trail along the canyon, the archer caught up with the turkeys as they moved slightly below him, going up the far side of a gully. Brush sprinkled the hillside, putting individual birds in, then out of sight. Now between 30 and 40 yards away, he hurried a shot-another miss. Nocking another arrow, he snapped off a second shot. It was nearly a clincher, skinning feathers from a bird's breast. But it was simply a closer miss and the birds were off again.

Though he was out of sight, Gary knew the time had come to ease the pressure. So, he picked out a dry-looking spot and started sharpening the used broadheads. For about 15 minutes, he worked the cutting edges with a small pocket stone, then slipped the arrows back into his quiver and took up the trail.

Dropping into the canyon to look for tracks, he had covered perhaps half a mile when he heard the birds talking amongst themselves. Circling to the left, he sneaked into a draw which led up toward the birds. Heavy cover allowed him to creep within 30 yards of them, but the brush that concealed him prevented a shot. There was just no way to get more than a fleeting glance at the mulling turkeys. Rather than spook them with an uncertain shot, he passed the chance. Kneeling quietly behind a bush until he (Continued on page 58)

36 NEBRASKAland

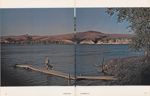

With trepidation, we were going to try fishing in August. The water was low, activity slow, but surprises lay in store

Ebb Tide at Enders

THINGS STARTED off slow, but still they looked promising. Only minutes after we launched our boat onto the receding waters of Enders Reservoir in southwest Nebraska, white bass started hitting. But despite their hearty appetites, they seldom ran more than seven inches in length. They bolstered our hopes even though we knew a number of things could keep our foray from becoming a red-hot excursion.

First, we were on the lake at the wrong time of year. It was mid-August, and the weather was sultry-dog days had burst forth in all their low-key glory. Then, too, Enders' 1,707 surface acres of water had shrunk in proportion to the needs of irrigators farther down the Frenchman and Republican River valleys. Local fishermen estimated that the water level was 23 feet below normal, leaving many boat ramps high and dry. Some, we thought, resembled lumpy airport runways which had just been hit by a twister. One, though, had been extended so that it reached the water even at its present low level. That's the one we headed for.

Dr. Don (Doc) Morgan of McCook and 13-year-old Rick, the youngest of his four sons, were my hosts for a few hours of fishing at the impoundment some 48 miles west of their home. Most of our gear had made the trip in the Morgans' 18-foot inboard-outboard, so all Doc had to do was negotiate 100 yards of ramp to put us in business. Consequently, only minutes after our arrival we were trolling toward the dam, staying fairly close to the bank. It seemed as if we were barely under way when I had a strike. From the tension on the line and the way the fish moved, i could tell he was small, but I just wasn't prepared for what I finally maneuvered into the boat. There, dangling from the treble hook of my silver spoon, was a tiny white bass which only a fertile imagination could stretch beyond six inches. Small fish often grow into big ones, though, so I tossed him back and again dumped the spoon over the stern only to retrieve his twin.

'They sure act hungry," the elder Morgan offered. "Now, if we can just get into the larger ones."

We had the only boat on the lake, but a number of other anglers were clumped along the shoreline, and their presence and quarry touched off speculation among our crew members. Enders is noted for walleye in April, May, June and October, but action is extremely light in August, so that pretty much ruled them out. Northerns are hot over the entire lake in April and May, and shoreline and bays are both productive then, but again it was the wrong time of year. Crappie are good from April to June, but August is a slow time indeed. The fishermen obviously were too early for yellow perch which move into the picture throughout September and October. And, since they were working gently sloping banks instead of dropoffs, their activity left us at a loss. Most of them were standing instead of sitting, and minnow buckets were much in evidence, but those clues didn't help either. Then someone mentioned that we were after bass in August when the best times are April to October with a lull in —you guessed it—July and August. That thought squelched further guessing games.

We were just coming up on another bunch of bank fishermen when a keeper slammed into my spoon and ended up in the boat. About 14 inches long, he put up a pretty good tussle before I hoisted him up past Rick who, by then, was contemplating changing lures. So, as a pall settled over our fishing again, we dived into our gear looking for something with which Rick could catch up. Then we settled back to watch the scenery and wait for something to happen.

"That boat ramp sure looks funny," Rick observed, pointing to a facility which sat high and dry on a hillside rather than at waters edge.

"About the only benefit a fisherman will get from low water is that it may concentrate hungry fish in a smaller area," I mused. But there are a lot of people who are mighty glad to have Enders here to draw from during dry spells.

Nebraska depends on water the way some highly industrialized states rely on coal and petroleum. This particular area is something of a breadbasket, with wheat and cattle the major products. Farther down the Frenchman and along the Republican, corn takes over and Enders provides a part of the water it takes to produce the crops. !t hasn't always been that way, though. In years past, farmers were at the mercy of nature, with flood and drouth very real threats. In 1934, things were so dry there were almost no crops. Then, a year later, floods nearly tore this part of the state apart. That's why Enders and a number of other nearby reservoirs are here (Continued on page 59)

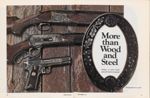

More than Wood and Steel

Artistry in arms holds special brand of appeal

NOVEMBER 1972 41

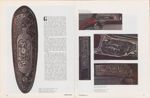

GUNS ARE COLD, impersonal objects. In the past, a gun was a tool to eke r out a living from an unyielding land, much the same as an axe or a plow. But times have changed. Guns, for the most part, are no longer simple tools. Too often, nowadays, guns are associated with how people have used them. More than ever before, wars and myriad crimes have cast an unfavorable light on guns and their owners. Even the time-honored sport of hunting has fallen on dark days in some circles. But guns, like blocks of marble, become good or bad only when associated with man's experience.

When Sol Levine of Columbus displays his gun collection to house guests, all view them with appreciation. But then, his collection of firearms is more than the usual assemblage of wood and steel — they are works of art. Custom stocks of the finest hardwoods and steel engravings by the world's most revered craftsmen distinguish these guns from assembly line products. To a gun connoisseur, they are a delight.

A sportsman for many years, Mr. Levine began his collection more than 25 years ago. Though he owned several custom-made guns then, his first adventure into the realm of one-of-a-kind firearms came as the result of a friend studying international law in Austria. When his friend wrote back, raving about the exquisite engravings he had seen in Ferlach, a city recognized for centuries as the leader in metal engravings, Mr. Levine commissioned work on four custom guns. Albin Obiltschnig, already recognized as one of the world's finest, completed the work. When they arrived, Mr. Levine became an addict. After owning those first ornate shotguns, all others seemed naked by comparison. That marked the beginning of a long and rewarding friendship with Austria's Meister Graveur, and formed the nucleus of what would become one of

Since then Herr Obiltschnig has engraved nearly all of the Levine guns. Most are stocked in the United States though.

"Austrians are unexcelled engravers of hunting scenes and game animals and the British are probably the finest craftsmen when it comes to scroll work and filigree. But we have the most proficient stockers right here in the United States he said.

The late Bob Owen of Port Clinton, Ohio, and Hal Hartley of Lenoir, North Carolina, have fashioned and checkered most of the stocks in Mr. Levine's collection. Mr. Hartley visits Mr. Levine each fall. Also included in the collection are the work of Lenard Brownell of Sheridan, Wyoming, and Dale Goens of Cedar Crest, New Mexico, all peerless in their fields.

Friendships developed with engravers, stock makers and other collectors have been as rewarding for Mr. Levine as the actual gun collection. In order to correspond with Herr Obiltschnig, he has taught himself to read and write German. A few years ago the engraver spent a week with the Levines while visiting in this country. Different stock makers drop in from time to time, too. This close comradeship that develops among hunters or gun fanciers is perhaps the most valuable part of the total experience.

All of the guns in the Levine collection are in firing condition and some have been used on the range. No matter how beautiful a gun might be, Mr. Levine wouldn't want it if it weren't fully operative.

With the cost of quality engraving climbing sharply, his collection will probably level off. Now, it is enough just to have the handsomely adorned arms where he can appreciate them in spare moments and share their exquisite detail with those who drop in from time to time.

Bass in the Bayou

We knew that we needed a boat. But hauling it into our remote area was an unexpected hassle

WE HAD OUR backs to the water, fishing rods folded and empty stringers tucked in our closed tackle boxes. After hours of hard fishing, we were ready to concede that there wasn't a bass to be had.

Suddenly, the twilight stillness behind us was shattered by a commotion that could have been only one thing —a big fish breaking water.

"Was that a bass?" blurted one of my companions. "There aren't any bass here. It was probably just a carp," the other said dejectedly. While my cousin, Don, and my brother, Roger, were wasting breath on conversation, I was rooting through my tackle box for a surface plug.

Just a minute before, the water of this Niobrara River bayou was like a mirror, broken only by ripples from the barrage of lures we had thrown. Now, 70 yards to our left and 40 yards to our right, fish were churning the surface. And, their almost black coloration told us that they definitely were not carp.

But, the fish might just as well have been tuna cavorting in the Pacific Ocean for all the good they did us. Those on our right were just beyond a clump of bushes that would grab any lures thrown that way. And, an (Continued on page 62)

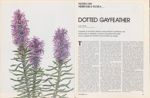

NOTES ON NEBRASKA FLORA... DOTTED GAYFEATHER

Capable of surviving nature's most adverse conditions, this hardy plant is relatively common throughout the state and is praised by farmers and ranchers as forage

THE DOTTED GAYFEATHER'S name is an attempt to describe this pretty prairie flower. Many glands covering the leaves do indeed give the appearance of dots, while the lively purple flowers resemble gaily colored feathers. The same dots or glands that give the plant its common name are referred to by the botanical name Liatris punctata.

Luxuriant patches of gallant purple spikes identify this flamboyant native of Nebraska. It is desired by ranchers for its commendable grazing qualities, sought after by flower arrangers for winter bouquets and praised by all who know it for its enchanting loveliness. The dotted gayfeather may well be our most desirable wildflower.

The dotted gayfeather is found from Alberta to New Mexico east to Wisconsin, Michigan, Iowa, Missouri, Arkansas and Texas. In Nebraska it blooms from late in August to mid-October. The dotted gayfeather is usually found in dry, light soil on native pasture and prairie. It is sometimes found in richer, more moist soil, and when it does grow under these conditions, the quality and size of the blossoms are increased. The tops of rolling hills or upper parts of south-facing slopes are the sites where the flower is most likely to be found.

Drought has little effect on established plants. Large woody roots adapt well in dry conditions. The famed prairie ecologist, J. E. Weaver, relates an example in his book, Prairies, NOVEMBER 1972 Plants, and their Environment. During a period of extremely dry, hot weather, "nothing but false boneset and blazing star (dotted gayfeather) could endure The large root which makes the plant so drought-resistant also makes it possible to age the plant by counting its growth rings. Some dotted gayfeather plants have been reported to be 25 to 30 years old. The tap root of such a mature plant may be four inches or more in diameter and extend to a depth of 15 feet or more. A first-year plant, which may be only five inches tall, has been known to develop a tap root 33 to 38 inches long.

Numerous stout, erect stems arise from the root crown. The stalks may vary in length from six to 30 inches, depending upon soil and moisture conditions, and terminate in crowded leafy spikes of flower heads. Flower heads are composed of from three to six purple flowers densely crowded on the upper half of the stem. Hundreds of seeds result from these flowers and are dropped in late September and October.

Dotted gayfeather is a desirable forb in pastures for both livestock and wildlife. Cattle take the plant in the early growth stages and the large number of seeds produced later serve as food for small mammals and seed-eating birds. Dotted gayfeather is considered to be a decreaser on native range and disappears with palatable grasses under excessive grazing.

Many local names have been given the flower. Dotted-button snakeroot, button snakeroot, devil's bite and rattlesnake master are some which refer to the plant's fame as an antidote for rattlesnake bites. Some people believe that when a person is bitten by a rattlesnake, the bulbs of the plant should be bruised and applied to the wound, while at the same time a decoction of the bulbs in milk should be taken internally. The names throat-wort, sawort and backache-wort are further testimony to the medicinal properties claimed by the dotted gayfeather. Indians used the carrot-flavored root for food in early spring, accounting for the names Indian carrot and rough root. The Omaha Indians also used dried and powdered blossoms. This preparation was blown into the nostrils of a horse to give him added endurance, longer wind and more speed.

The dotted gayfeather adapts well to survive the worst test nature can put a plant through. Its survival as one of the truiy beautiful elements of our environment depends upon man, for it is at the mercy of overgrazing and the mowing machine. Anyone who appreciates the natural beauty of the prairie or is fond of wildflowers is sure to be impressed by the sweep of color provided by the dotted gayfeather. Its important role in the natural plant community, its natural beauty and its benefits as food for wildlife and cattle all make the dotted gayfeather a wildflower worth knowing and protecting.

PARASITES, PREDATORS AND PATHOGENS

(Continued from page 15)abandonment of all pesticides and those in agri-business are unable or unwilling to discontinue their use.

Somewhere between these extremes lies the answer to both insect control and environmental purity. Theoretically there are three different approaches to insect control — chemical, cultural and biological.

Chemical control, as we know it today, is generally effective, but at a price costly to the environment. Low cost, ease of application and initial effectiveness are the advantages. Development of resistant insect strains, removal of beneficial, non-target species and the accumulation of persistent residues in the environment are strong points against continued use of some chemical controls.

Insect populations can also be managed to some extent by different cultural practices. Basically, this involves the manipulation of insect habitat. Strip farming, use of resistant varieties and destruction of over-wintering sites are examples of cultural controls.

Biological control is not a new approach to reducing insect populations, but is one of the most interesting and probably the most promising.

Biological control has been defined as "the direct and indirect use of living organisms to control pests and reduce damage below economic levels." The living organisms suggested here are either parasites, predators or disease-producing microorganisms called pathogens. All insect pests have their natural enemies, and biological controls simply make use of these enemies to reduce undesired insect pests. Such control simply utilizes natural controls already present by manipulating them to increase effectiveness.

Entomologists utilize three basic biological controls: (1) searching for natural enemies in the country where the pest originated and introducing them into the area where the pest now occurs, (2) the conservation of existing natural enemies of the pest, (3) mass rearing and periodic release of large numbers of the pest's natural enemies when it is most vulnerable.

The first widely recognized and successful use of biological control was in the late 1880s in California. The developing citrus industry was seriously threatened by a cottony-cushion scale that attacked the fruit trees. As a result, many growers were being forced to abandon their plantations. At that time, no chemical methods were known to control the scale. An entomologist discovered that a small lady beetle, known as vedalia, was attacking and controlling the scale in Australia. The first shipment of vedalia reached California in 1888. Within two years, control was effective and the citrus industry was saved at a cost of less than $5,000 dollars. Today, 84 years later, 50 NEBRASKAland this method of control is still effective.

While insects are usually thought to be one of the most efficient animal groups in controlling undesirable insects, other animal groups are also effective. Bats, moles and shrews feed almost exclusively on insects. Under certain conditions they can be important agents in pest control. It is ironic that the controlling influence of mammals was dramatically illustrated in the 1940s, about the same time that chemical pesticides were first coming into general use.

Forest-related industries have been of primary importance to the economy of Newfoundland. During the '40s, severe outbreaks of the larch sawfly were making serious inroads on commercial timber. At the invitation of the Newfoundland government, an entomologist studied the problem and made recommendations. His report noted that the absence of shrews and insect-feeding mice on the island might have some effect on the runaway sawfly. Shrews and mice were plentiful on the mainland, and no sawfly outbreak had occurred there. Following his recommendation, 22 shrews were released in 1958. By 1960 the shrew population had increased to an average of six per acre, and shrew predation of sawfly cocoons was reported to be an effective control measure in the release areas. Though researchers hesitate to say that the introduction of shrews has eliminated the sawfly problem, they feel confident that further studies will prove this to be the case.

More suburbs are dotted with purple martin houses each year, attesting to public acceptance of the importance oi birds in controlling insect numbers. Many bird species are entirely insectivorous, and others feed heavily on insects during certain seasons. Examples are numerous.

Cuckoos habitually feed on hairy caterpillars, such as tentmaking species that attack various trees. Woodpeckers, as a family, comprise a very useful group, feeding upon the larvae of woodboring insects. Flycatchers, meadowlarks, orioles and blackbirds consume enormous quantities of insects. All swallows are exclusive insect feeders, capturing and consuming their prey on the wing. Flickers are known to eat vast numbers of chinch bugs, and the diet of the kingbird, or bee martin, is made up of nearly 85 percent insects.

Research studies documenting the importance of the insect-feeding habits of birds are also abundant. A study in Nova Scotia, Canada, showed that the northern downy woodpecker was an efficient enough insect predator in most fruit orchards to preclude spraying. Wisconsin studies indicated that the tiny kinglets and warblers were important controllers of insects that damage plantations of larch. As many as 100 to 400 insect pests were found in the stomachs of individual birds. Research in Mississippi illustrated that the yellow-shafted flicker is the most important bird predator of the southwestern corn borer. Flickers, it seems, can sense corn borer larvae in overwintering stalks and feed effectively on them. The downy woodpecker helps control the European corn borer. Grouse, turkey, quail and pheasants have been proven to be important controllers of grasshoppers, locusts, crickets, caterpillars and similar insects during certain seasons.

While some mammals and birds are recognized as important agents in reducing insect numbers, many entomologists believe that the greatest single factor in keeping plant-feeding insects from overwhelming the croplands of the world is predation by insects themselves. When we consider the use of non-selective pesticides that destroy*all insects in the sprayed area, it seems as if these beneficial insects aid man's interests in spite rather than because of him.

The use of one insect to control another is perhaps the oldest form of biological control. Since the lady beetle proved effective in controlling scale in citrus groves, many different species of insects have been used in attempts to reduce injurious insect populations. Though many species exert some measure of natural control over other insects, some are outstanding examples. Larvae and adults of most ground beetles rank among farmers' best friends. They are voracious predators of many noxious insects. In fact, one species was imported into England to control the gypsy moth. A single larva of this predacious beetle will destroy 50 or more gypsy moth larvae during its two weeks of development.

Aggressive insect predators like robber flies, praying mantes, parasitic wasps and dragonflies consume large quantities of other insects, mostly pest species. Tillyard, a respected entomologist, was so impressed with the dragonfly's feeding habits that he said: 'They are the most powerful determining factor in preserving the balance of insect life in ponds, rivers, lakes and their surroundings." In the stomach of one dragonfly he found over 100 mosquitoes. Another time he fed 60 mosquito larvae to one dragonfly in less than 10 minutes.

Closer to home, an insect with the impressive name of Lysiphlebus testaceipes, Lysa for short, is currently being watched closely by entomologists at the University of Nebraska. Lysa is a gnat-sized, parasitic wasp that, according to Bob Roselle, extension entomologist, "is keeping us in the milo growing business." In July, he found that from 20 to 80 percent of the greenbugs present in some sorghum fields were parasitized and held below the point of economic importance by the Lysa wasp. The Lysa controls infestations of the greenbug aphid by laying eggs on individuals it encounters. Eventually the aphid is killed and serves as a host for hatching wasps. Someday the Lysa may be introduced into infected fields for greenbug control.

Another insect is currently under study that may some day provide effective control of musk thistle. Dr. M. K. McCarty with the U.S. Department of Agriculture is researching the possible use of a weevil which may offer some control of the noxious weed by destroying seed heads before fruiting. Releases of the insect were made at two sites in the state this summer.

Dr. McCarty has also been studying the roles of two native species of fruit flies for control of some pasture thistles. Platte thistle, limited primarily to the Sand Hills and western areas of the state, has been held in check by these flies. Yellowspine and wavyleaf thistles would also, undoubtedly, be more of a problem without the presence of fruit flies.

Microorganisms offer yet another alternative. Microbial insecticides are pathogenic microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, protozoa, fungi or by-products of these organisms. Currently, only two microbial insecticides are registered for use, compared with several hundred chemical insecticides. (Continued on page 55)

where to go... Scottsbluff Circle tour

SCOTT is a name which cannot be easily overlooked in Nebraska's Panhandle. Scottsbluff is the largest city west of North Platte. Scotts Bluff County's western border is one with Wyoming. And, Scotts Bluff National Monument is perhaps the most imposing landform in the Wildcat Range, an escarpment which is the east's first hint of Western mountains. And, 'all three are named for a single individual whose misfortune turned him into a folk hero in some of Nebraska's most beautiful country.

Hiram Scott and a party of trappers were returning from rich Western fur areas when they were attacked by Indians. Scott, or so the story goes, was wounded before his companions could reach safety atop a high butte. Unable to travel overland, Scott was a burden to be reckoned with. So, the other NOVEMBER 1972 trappers had to decide whether to try to fashion a raft and float him down the North Platte River, or abandon him and save their own skins. They opted for the latter. The wounded trapper, however, did manage to crawl some distance, but his remains were discovered the following spring.

In the years that followed, the story of Hiram Scott grew into a legend so prominent that the name became synonymous with that part of the Panhandle. Today, it remains something of a symbol for the area, but the city of Scottsbluff has gone far beyond its namesake in establishing the Scotts Bluff National Monument Circle Tour.

Riverside Park Zoo (No. 1 on the map) offers an urban safari in the lap of comfort. The largest free zoo in Nebraska, Riverside houses animals from around the world. Some 40 campsites, several with utility hookups, and picnic and playground areas are also available.

The Scotts Bluff Country Club (No. 2) is reserved for members and their guests. However, members of other clubs may also use the nine-hole, grass-green course. City officials point out, too, that there is an 18-hole public course (Riverside Golf Club) located in Scottsbluff.

Travelers on the old Oregon and

Mormon trails used the bluffs in the

region as guideposts on their epic journeys. And, today modern travelers still

set their course by Scotts Bluff National

Monument (No. 3) just south of the city.

Rising some 700 feet above the North

Platte River, the monument affords fantastic vistas on clear days. Points as far

as 125 miles away are visible from the

summit, while the Oregon Trail

Museum near its base recalls the days

53

More than 1,500 historical artifacts are on display at the North Platte Valley Museum (No. 4), telling the story of the valley and its people from the first whites to present. An information booth offering free maps and brochures designed to provide better understanding of the area is located in the museum.

Southwest of Scottsbluff, Robidoux Pass (No. 5) remains today much as it was from 1843 to 1851 when westward traffic passed through. A longer route, Robidoux Pass was the only path through the Wildcat Hills prior to 1869 when the army cleared out Scotts Bluff Pass. Hardships of yesteryear's travelers are exemplified by the Robidoux Blacksmith Shop site and pioneer graves (No. 6). On the north side of the road, wagon ruts carved by fur traders and emigrants headed for the Rocky Mountains and the West Coast are still very much in evidence (No. 7), and Laramie Peak is visible some 114 miles west (No. 8).

The Old Pioneer Trail (No. 9), a local highway for settlers in the area, once passed through this region, carrying traffic from the Pumpkin Creek Valley to the North Platte River Valley in the days before superhighways made the trip much faster and a lot more comfortable. Life was simpler then, but it was definitely harder. Supplies were hard to come by, and area residents were dependent upon the second Robidoux Trading Post (No. 10). Robidoux, somewhat of a legend himself, chose a site where an old Indian trail entered Carter Canyon and where the Indians camped on their treks through the hills. The area is tamer now, but the wild beauty of the setting and spirits of the past still bring history vividly to life.

Just south of the trading post, the Wildcat Hills State Game Reserve (No. 11) rounds out the tour. Here, many animal species which once called Nebraska home, still stalk the land. Elk and buffalo roam the plains their ancestors knew, and provide hours of enjoyment for all who visit the refuge. In the summer visitors may enjoy theater productions in a natural amphitheater in the hills.

Hiram Scott may be gone now, but his spirit remains to watch over a land he knew so well. And, today that land draws thousands each year to rub shoulders with history and drink their fill of beauty.

PARASITES, PREDATORS AND PATHOGENS

(Continued from page 51)Microbial diseases, unlike chemical controls, occur naturally in the environment, are biodegradable, and are generally nontoxic to other life forms. The major drawback to the use of microbial insecticides is that many are costly to produce. Perhaps, though, we have reached the point where the aftermath of uncontrolled application of chemical insecticides is proving to be even more costly than the initially more expensive biocides.

Biological controls have three distinct advantages over chemical controls. First they are relatively permanent. Once established, their numbers will fluctuate with the pest populations. Secondly, biological controls pose no threat to the environment or other life forms. Finally, except for microbial controls, they are less expensive.

Biological controls are certainly not a panacea for every insect pest. And they won't be available tomorrow to replace today's environmentally dangerous chemical insecticides. But with our ailing ecosystem, biological control of insect pests is a potentially valuable direction in which to look. What is needed now are fewer alarmist cries from armchair ecologists and an end to feet dragging by some insecticide producers and researchers. More research funds and efforts must be channeled toward the rapid replacement of chemical controls with environmentally safer measures. For, if in the process of suppressing insect pests we destroy other segments of the environment, we have gained little.

STRATEGY OF STRUNK

(Continued from page 18)the valley's unpredictable floods. Despite the spending of millions of dollars, these people would be no better off than they had always been.

Angered and embittered, Harry Strunk again went into action. Within a few days, he called together representatives from towns in the Republican Valley drainage area from Haigler to Oxford. At the meeting in McCook, 40 men expressed their shock concerning the Washington announcement. For 15 years they had advocated a series of small dams in the upper valley, dams which would give them flood protection, irrigate more acres, and cost $8 million less. They also argued that the series of upstream dams would also protect Kansas City, one of the major reasons for the proposed dam.

More meetings followed —60 men, including representatives from Colorado and Kansas, attempted to form a Republican Valley Basin Reclamation Association (RVCA). While they were not against the Harlan County dam, their fear was that this proposal would ruin chances for further projects upstream. It was for the purpose of presenting the upper valley's case that the Republican Valley Conservation Association was organized in May, 1940. With representatives from 26 communities, the group elected Harry Strunk as its president. One of Strunk's first acts was to go to Kansas City to ask the Corps of Engineers why something could not be done to control the upstream waters of the Republican, too. When he was told that preliminary investigations showed that the cost of flood control upstream would greatly exceed the benefits, he produced affidavits from hundreds of landowners testifying to the property damage they had sustained. As a result of this meeting, the district engineer promised a second look at flood damage upstream.

To the delight of the RVCA, the new survey justified their claims. The report indicated that dams on the Republican's upper reaches would result in three-to-one benefits over cost —an exact reversal from the conclusions of the original survey. With these new findings, the Corps of Engineers began to make plans for the entire Republican watershed.

Concurrent with the Corps' investigations, the Bureau of Reclamation was making similar studies regarding the feasibility of irrigation in the valley. Out of the surveys of both agencies came the Pick-Sloan plan of development for the Missouri River basin, of which the Republican Valley is a part.

But before work could be undertaken in the valley, it was necessary that legislation be passed which would provide for an equitable division of the waters of the Republican River between Nebraska, Colorado and Kansas. Thus the Tri-State Water Compact was enacted, practically eliminating the possibility of future litigation over water rights and permitting the orderly development of irrigation and power.

The Republican Valley Conservation Association had a role in all of these negotiations, and the 1940s witnessed a host of additional accomplishments by this precedent-setting organization. Through its Washington D.C. lobbyist, M. O. Ryan, it urged necessary legislation and was primarily responsible for the formation of the Nebraska Reclamation Association, now the Nebraska Water Resources Association. They helped form the first seven Soil Conservation Districts in Nebraska in the lower southwest tier of counties and promoted the building of hundreds of small earthen dams throughout the watershed. The dams, built across dry gullies and canyons, served the two-fold purpose of halting erosion by run-off and providing watering ponds for livestock. They worked ceaselessly toward making their valley one in which "every drop of water that falls will be conserved and utilized for the benefit of the greatest number of people."

Finally, persistence paid off. On June 13, 1946, ground-breaking ceremonies took place for the huge Harlan County dam. Later that summer, the Enders dam was begun

and the next year saw the start of the Medicine Creek dam. The years since have seen additional projects. Today the lakes that have formed behind these dams are serving the tri-state area well. There are more than 27,500 surface acres of water, 225 miles of shoreline, and more than 24,000 acres of public-use and recreation land. The multiple-purpose lakes now give to a vast area flood protection which cannot be measured in dollars and cents. The waters are utilized for irrigation and improved reclamation practices, bringing annual increases in crop valuations. The names of these lakes are known well by anglers and other sportsmen: Harlan County, Swanson, Enders, Hugh Butler (or Red Willow) and Harry Strunk (or Medicine Creek).

Yet the work of the RVCA is not completed. Floods still occur on some of the streams and more dams are planned for the Republican River's headwaters. Harry Strunk died in 1960, but the RVCA's programs continue under the leadership of Don Thompson of McCook, who was secretary of the association from its earliest days. The Unicameral, during the 1950s, saw Senator Thompson sponsor and promote legislation that was vital for the RVCA's programs and similar water conservation work.

No longer is there poverty within plenty in the Republican Valley. The famine-feast cycle of available water has been changed to an orderly cycle of storage in winter and release in summer when it is most needed. The dreams of Harry Strunk have been realized.

Throughout all the years, Strunk published column after column in his newspaper, constantly pushing for the RVCA's programs. Always he was cajoling politicians, pressuring governmental agencies and persuading the public. After the devastating droughts and floods of the '30s, many people abandoned,southwestern Nebraska. But those who stayed met the challenge, led by Harry Strunk and the Republican Valley Conservation Association.

UNROCK FESTIVAL

(Continued from page 21)though mass production today provides him with household furnishings, man still remembers when things were made by hand, when time meant less and individual workmanship was significant. He remembers that time long before production records moved from kitchen scribblers to ceiling-high charts in corporate offices.

Lasting awareness of folklife is evident in the fact that the people are preserving not only handmade antiques, but also the methods whereby they were made. Each July the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. stages the Festival of American Folklife. Representatives from all states are there, bringing old crafts to life. Albert Fahlbush of Scottsbluff, who builds dulcimers, accepted the Smithsonian's invitation to participate in its 1971 exhibit at Montreal in Canada. It gave Ruth Fletcher of Elkhorn an idea. Why not do it in Nebraska? It led her to a meeting with Nancy Greer, also of Elkhorn, and together they talked about the idea with neighbors, friends and the Douglas County Agricultural Society. Then she and Nancy decided to put the show together. With newspaper and television publicity, they asked interested persons with handcraft hobbies to join the first folklife festival they planned to stage in August at the Douglas County Fair in Waterloo. It didn't take long until they had the names of several dozen people who promised they would come, and others from outside the state who asked to participate.

Arriving in Waterloo, the folk artists brought everything with them and set up shop in sweltering, mid-August heat under two tents provided by the fair board. Dave Jensen of Bellevue brought blacksmith's coals for heat to make square nails like those forged 100 years ago. Unusual? You bet, especially in view of the fact that Dave is only 15 years old. Despite his youth, he has built a smithy in his father's garage where he spends much of his time filling the air with the clanging of hammer on anvil.

Sister Raphael de N. D. of Omaha's Notre Dame Academy used a wood stove and lye to make her 595th batch of lye soap according to the recipe her ancestors had used. Dressed in black habit, she stood in the heat explaining for onlookers —just for the fun of it —what she was doing.