NEBRASKAland Magazine Photo Contest

designed to let you interpret Nebraska as you see it. Here are the rules: 1. The contest is open to all persons except employees of the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission and members of their immediate families. 2. All photographs must be taken within Nebraska's borders. 3. Entries must be submitted in one of the following five categories: A. Scenery; B. Conservation; C. Wildlife; D. Outdoor Recreation; E. People. 4. Submissions may begin at once. The contest closes at midnight, December 31, 1972. Winners will be announced in the May, 1973 issue of NEBRASKAland Magazine. 5. Only color photographs may be submitted as original color transparencies 35 mm or larger, or color prints 5 x 5 or larger. Negatives should not accompany color prints, but they must be available upon request if the photograph is chosen for publication. 6. Each picture must be accompanied by an official entry blank or facsimile. In addition, each transparency or print must be identified on the mount or on the back of the print with the entrant's name and address. 7. NEBRASKAland Magazine shall be given publication rights for each picture submitted in the contest. The name of the photographer will accompany each contest photograph published. 8. All winning entries will become the property of NEBRASKAland Magazine. Non-winners may have their submissions returned by enclosing a stamped, self-addressed envelope with each entry. 9. Entries will be judged by members of NEBRASKAland's staff. Decisions made by the judges will be final. 10. There will be first, second, and third-place winners in each category. In addition, there will be first, second, and third-place over-all winners. First-place winners will each receive a bound volume of NEBRASKAland's 1972 issues plus a two-year subscription to the magazine. Second-place winners will receive a two-year subscription and third-place winners will receive a one-year subscription.This photograph is submitted with the understanding I agree to be bound by the rules of the NEBRASKAland Color Photo Contest as published in NEBRASKAland Magazine. For additional entry blanks include above information or write NEBRASKAland Photo Contest, P.O. Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503.

SignedFor the record... WHO OWNS WILDLIFE?

There was a time when it didn't matter whether a hunter could think or not. All he had to do was find his game, get it in his sights, and haul it home after the shooting. Now, however, things are different. With the point system for ducks, each gunner must identify the species and sex before he shoots. And, with more and more hunters in the field, big-game hunters must be dead sure of their targets before they squeeze off their shots. With hen pheasants on the protected list, scattergunners must know what their speeding targets are even before they begin their swing. So, more than any other sport, hunting has become a game of clear thinking and accurate identification.

With that trend in hunting, some weighty questions have arisen. The moral issue of hunting is constantly questioned, and the right of landowners to restrict hunting inspires heated discussions. And, from all concerned with the sport comes a most oft-asked question —who owns wildlife?

Hunters indicate that it is impossible for the farmer to own other than his own property and the crops on it. How can one lay claim to a population that runs wild and free, they ask. Landowners, on the other hand, frequently note that they provide cover, feed, and shelter for animals that roam their land. The mere fact that wildlife carries no brand deters very few, if any, of them.

Such rationalization puts the two factions at loggerheads.

I personally feel that the farmer has a certain priority, not only to defend the game on his land, but to take a fair share as a sort of payment. After all, his crops are the nourishment which keeps the wildlife alive, and it is he who allows acres to become habitat for the animals which frequent his fields. For many, wildlife has an aesthetic value with which they are not willing to part for the sake of the hunter.

But, sportsmen must be understood, too. Simply to let the resident game populations multiply themselves into oblivion is a cruel course, indeed. Starvation will run rampant through populations that are allowed to continue uncontrolled. And, farmers' yields will feel most acutely the pressure brought on them from mushrooming generations of wildlife.

The battle lines are drawn and each faction deems wildlife its own, but this is no more valid than each person laying sole claim to all the earth. Instead, there must be some middle ground, an area in which landowner and hunter learn to co-operate, to live side by side in a give-and-take situation. Who owns wildlife? We all do, and it seems that the best avenue toward better understanding is for each faction to take the desires of the other into consideration and strike a happy medium for the good of all—even for wildlife.

Who's who in water pollution?

65 percent industrial 20 percent municipal 15 percent agriculturalWe've used our nation's waterways as sewers for 200 years. Now we have dirty rivers, dying lakes, and fouled seashores. Our clean up plans are mammoth, but our progress is slow.

Speak up for Clean Wafer!Ecology for tomorrow's sake

Speak Up

NEBRASKAland Magazine invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to Speak Up. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters. —Editor.WHOOPS-'I'll bet Sam Bass never used a High Standard .22 revolver to do his evil work as you did for the historical marker on the inside back cover of the February NEBRASKAland. And, he surely didn't have a zipper on his coat.

"I loved your February hostess, but you'll probably get a lot of mail on that one.

"Regardless of your faults, I still enjoy NEBRASKAland and recycle it by sending it to a teacher friend in India where it is read by hundreds."-Allan Skinner, Oregon, Wisconsin.

UNIQUE SCHOOL-"I have been a rural school teacher for several years now, and would like to tell you a little about the present school in which I am teaching.

"It is called the Burr Oak School, District 63 in Custer County. It has been in continuous operation for almost 100 years, but we cannot be certain how long it has been open because the Custer County Courthouse burned down in 1910, destroying all early school records. There is one individual, however, who is in his 90's and says the school was there before his birth. Some of the children now attending the school are the fourth generation of families who have gone there.

"I am certain many changes have taken place within the past century in the school. In fact, it has not always been known by that name, but has had two others that I know of. The oneroom school became a modern one just five or six years ago, and this past year new carpeting has been installed. Modern teaching methods such as the use of tape recorders have also been introduced."—Jean Marshall, Eddyville.

RECOLLECTIONS-"This poem, in memory of Charles Simmons, Scottsbluff artist, was written by Susan Skorupa of Denver, Colorado. She lived across the street from Mr. Simmons from the time she was four years old until his recent death." —Vilma Toufar, Columbus.

CHARLIE Mazes of childhood dreams Unraveled in all their grade-school glory On concrete steps and wooden bannisters — Six-shooters strapped to seven-year-old hips, I could sit wide-eyed for hours Listening to stories of real gunfighters, Of wagon trains and trappers. Then Ed run off to "injun territory'' again, So innocent, yet wiser in a way. Little hurts, big disappointments, Shared in quiet confidence Through a lifetime of July's. And unknowingly, his rough but gentle ways Taught me to "bend with the wind, Skipper". Winds for him blew hard But he bent with them like the old cottonwoods Across his beloved prairies. I like to think That we two were something alike— He, yearning to be free again To pace old riverbeds known only to his past. I, to find reality amid the turbulence Of my thoughtless youth. He gave me of himself. More than historical facts. He gave me his time, an exceptional gift To give to me one so many years away. Someday, I hope, when I'm old and worn, And I've walked all my prairies, Even if they're only in my mind, Perhaps there will be someone Who needs my understanding As much as I needed his. And I pray that I can take them by the hand And give them the understanding he gave me. Too late now, I wonder If he realized how much I loved him— Charlie, my greatest teacher.ONE STEP FURTHER-"In regard to the article, On the Trail of the Kiowa, December 1971, Samuel Davis Sturgis not only attained the rank of brigadier general during his military career, but was promoted to the rank of major general of Volunteers on March 13, 1865.

"Having been given the permanent rank of full colonel following the Civil War, Sturgis assumed command of the Seventh U.S. Regiment of Cavalry on May 6, 1869. Contrary to popular belief, it was Sturgis who was the regimental commander, not George Armstrong Custer, when the Seventh Cavalry rode out of Fort Lincoln, North Dakota that foggy morning of May 17, 1876, in an attempt to link up with the columns of General George Crook and Colonel Gibbon.

"Colonel Sturgis, getting on in years and disenchanted with the bleakness of frontier duty, absented himself from Fort Lincoln whenever he could. He was in the east during the Centennial of 1876, and because Custer, a lieutenant colonel, was the ranking officer of the Seventh Cavalry at Fort Lincoln, it was he instead of Sturgis who finally was permitted to lead the ill-fated troops out of the fort to their destiny. This came after Generals Terry and Sheridan interceded in Custer's behalf in Washington, since the brash, flamboyant Custer, in President Grant's opinion, was nothing more than an unreliable 'troublemaker'.

"One of the officers who rode with Custer was one of Colonel Sturgis' sons, Second Lieutenant James Garland Sturgis. He died with the rest of the troops at the Little Big Horn River in Montana on June 25, 1876, and for that, Colonel Sturgis maintained a neverending hatred for the memory of George Armstrong Custer." — H. M. Mateja, Honolulu, Hawaii.

RELOCATION PLEASE- I was born and raised in Fort Calhoun, and have noticed that whenever mentioning Fort Atkinson as in the February issue of NEBRASKAland (Outpost of Expansion), you place it '9 miles south of Blair' or '15 miles north of Omaha'.

"Actually, it is on the outskirts of Fort Calhoun which, incidentally, has a new museum with very many interesting things found around the site of Fort Atkinson.

"Please have pity on Fort Calhoun and put it on your map— it is on others." — Donna Kruse, Kansas City, Missouri.

We couldn't have put it better ourselves. From now on, we'll try to include Fort Calhoun as one of the jumping off points for those wishing to visit Fort Atkinson State Historical Park which is now under construction.— Editor.

The Forest Is Alive Showered during a pre-dawn hush, the Missouri bluffland erupts in color and cacophony with the sun's first rays of warmth

White-water Wipeout Four professional canoeists become entangled in a mixture of humor and pain during their attempt to conquer the Snake

The House of Brownville Uncertainty about the future reigns supreme in a community with a rich heritage, but fraught with divided loyalties

Snipes Turned Ducks Quest for waterfowl at Ballards Marsh becomes a lesson in duck identification for a pair of inveterate hunters

Cover: The Larson and Sedlacek families, and Mary Nickels, all of Columbus, enjoy a day of camping in Ponca State Park. On page 7 is a scenic view of the Seven Sisters near Fort Robinson. Photos by NEBRASKAland's Lou Ell

Boxed numbers denote approximate location of this month's features.

NEBRASKAland

Outdoors FOR THE RECORD: WHO OWNS WILDLIFE? Francis Hanna 3 THE BIG HAUL John W. Ross 9 HOW TO: WATERPROOF A MAP 10 WHITE-WATER WIPEOUT W. Rex Amack 14 PREDATOR CONTROL SIN OR SALVATION? Ross A. Lock 24 THE FOREST IS ALIVE 26 HOOKED ON CARP George F. Ruppert 36 SNIPES TURNED DUCKS Jon Farrar 38 NOTES ON NEBRASKA FLORA: BUR OAK Clayton Stalling 50 OUTDOOR ELSEWHERE 66 Travel BE PREPARED 12 THE HOUSE OF BROWNVILLE Warren H. Spencer 20 ROUNDUP AND WHAT TO DO 52 WHERE TO GO 55 General Interest SPEAK UP 4 PONCA CURES Faye Musil 18 SHADES OF GRAY 42 Managing Editor: Irvin Kroeker Advertising Director: Cliff Griffin Senior Associate Editor: Warren H. Spencer Art Director: Jack Curran Associate Editors: Art Associates: Lowell Johnson, Jon Farrar C. G. (Bud) Pritchard, Michele Angle Photography Chief: Lou Eli Photo Associates; Greg Beaumont, Charles Armstrong, Bob Grier NEBRASKA GAME AND PARKS COMMISSION: DIRECTOR: WILLARD R. BARBEE Assistant Directors: Richard J. Spady and William J. Bailey, Jr. COMMISSIONERS: Francis Hanna, Thedford, Chairman; Dr. Bruce E. Cowgill, Silver Creek, Vice Chairman; James W. McNair, Imperial, Second Vice Chairman; Jack D. Obbink, Lincoln; Gerald R. Campbell, Ravenna; William G. Lindeken, Chadron; Art Brown, Omaha.NEBRASKAland, published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. 50 cents per copy. Subscription rates: $3 for one year, $5 for two years. Send subscriptions to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503.

Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, 1972. All rights reserved. Postmaster: If undeliverable, send notices by Form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second-class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska.

Travel articles financially supported by DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT Director: Stanley M. Matzke; Tourism and Travel Director: John Rosenow.

NEBRASKAland

What a Lineup!!

GLEN CAMPBELL

JIMMY DEAN

DAVID CASSIDY

ROY RODGERS & DALE EVANS

Surplus Center

Mail Order Customers • All items are F.O.B. Lincoln, Nebraska. Include enough money for postage to avoid paying collection fees (minimum 85d. Shipping weights are shown. 25% deposit required on all C.O.D. orders. We refund excess remittances immediately. Nebraska customers must include the Sales Tax. BENJAMIN Single Shot AIR RIFLES Choice .177 or .22 caliber $31.95 • ( sON-082-BAR ) - - Safe, accurate, powerful, economical. Shoot indoors, outdoors, anytime. Use for target shooting, pi inking or small game. Pump action, rifled barrel, Monte Carlo style wood stock. • Penetrates up to 1" in soft pine. Muzzle velocity up to 750 FPS. Single shot. Adjustable rear sight. Choice of Model 342 for shooting .22 cal. pellets or darts or Model 137 for shooting .177 col. pellets or darts. ( 6 lbs. )(A) Bag $58.50

(B) Bage $54.95

Cold, numb, and exhausted from their ordeal, our "catch" is landed in boat

The Big Haul

I REALLY don't know just where this story should begin, but I do know that the events touched the lives of several people, and will probably be remembered for a while by most of us.

My wife, Ruth, and I love camping and fishing, so from our home in Omaha we visit many of Nebraska's lakes and streams. From early April to late October in 1971, we spent 16 weekends outdoors, from the Brownville State Recreation Area on the Missouri River to Merritt Reservoir near Valentine.

But, it was November 1 3 that year I remember so well. We had returned to Branched Oak Reservoir near Raymond that Saturday because my wife had landed an 11-pound, 4-ounce northern the day before. We couldn't get a Master Angler application then, so had obtained one in Omaha and returned to have it certified at the store where we had the fish weighed.

Not wanting to waste the day, even though the weather had turned nasty — cold and windy —we decided to go fishing. So, about 10 or 11 a.m. we were sitting in my 12-foot boat fishing off the face of the dam. Then, we heard some young people out on the lake yelling "Hey, hey, hey!" I thought they were either horsing around or calling to someone on the bank. They were quite a distance from us, so it was difficult to see them clearly or make out what they were doing.

After about five minutes of yelling, my wife said she thought she heard the word "help", so we immediately started taking in our poles (four of them), and the two anchors we had out. Of all times, the anchor lines were tangled so that it took several more minutes to work them loose and get them into the boat.

While I untangled the lines, my wife had been yelling and waving her arms at three men in another fishing boat north of us. She told them to follow us as someone needed help.

The young people were still shouting and my wife was yelling back that we were coming. Finally, we got underway.

When we got nearer, I saw four young men and one girl in the water. The long, narrow racing shell they had been rowing was swamped beneath them. The other fishing boat was still some distance away and moving very slowly, so the only thing to do was load them all into our boat. I was a little leary, because our boat is only 52 inches wide, 19 inches deep, with a 7 horse motor. It is just a nice size for 2 people.

The youngsters were so cold, numb, and exhausted from the ordeal that they could hardly pull themselves aboard, but at last we were all crowded together. I was even going to pull their shell in, but by then the other boat arrived, so I asked the operator to tow it.

Heading for the south shore as fast as my small motor would go, I watched the youngsters shiver uncontrollably. Suddenly Ruth shouted that we were taking water. I immediately throttled down and took stock of our situation. There were seven people in a boat meant for no more than four, only two life jackets, five people so cold they couldn't swim five yards, waves kicking up from a strong, cold wind, about three inches of freeboard left, and quite a distance yet to shore.

We were so jammed together that I soon felt the water from their clothing getting me wet.

We finally got to shore safely, and the other boat brought the shell in. I helped the boys get it out of the water and onto the bank. Then I noticed that the other fishing boat was much larger and roomier than mine, but it had only a three-horse motor, which explained why it was so slow.

During all this confusion, no one had been introduced, so I only know that the young people were students at the University of Nebraska and that the other three anglers were from Douglas County.

One thing I do know. Despite our several good fishing days, that was definitely our biggest haul of the season, and I'm glad that my wife and I were there to help. THE END

HOW TO, Waterproof a Map

Plastic coating now could well keep you from singing backwoods blues later onANYONE WHO has devoted much time to reveling in the back country far from civilization or hard-surfaced roads knows the value of a good topographic map. But, even a good map can become worthless. It can dissolve into a handful of pulp after a river dunking or become a mass of tattered shreds after repeated use. Here, then, are some ideas you would trade your best knife for, should your map be rendered useless in strange surroundings.

Although an extremely simple process, few people ever take the time to waterproof a map. Yet, there are materials on the market which make it a task lasting only a few minutes and costing only a few cents.

First is the matter of getting the map. There are offices throughout the state which make them available. Every county in Nebraska, for instance, has an Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service office, which provides them. They have a sample copy on hand for you to look at, but additional copies must be ordered, so plan ahead. If these maps do not suit your purposes, there are other sources. The Conservation and Survey Division, University of Nebraska, 113 Nebraska Hall, Lincoln, Nebraska 68508, is a good bet. They have topographic maps on file of most sections of the state. These are detailed enough for almost any excursion, whether it be a wandering trek over rough terrain or a canoeing trip along a strange river.

An index showing the mapped areas is available free of charge. From it, you can determine the areas you wish to traverse. Maps can then be ordered for 50 cents each, including tax and postage. Also, the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission recently printed a map of the Pine Ridge area which can be obtained free by writing to the Commission office at Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503.

Now for the protective coating. Perhaps the best method is to cover the map with special plastic sheeting. One of these is known as "Seal-Lamin", a thin, transparent material sensitive to heat. You simply lay it on the map, cover it with a piece of heavy paper, and run a medium-hot iron across. The heat from the iron laminates the plastic to the map. You should be careful to work outward from the center of the map to prevent bubbles, and it is best to experiment before tackling your main project.

Roll of plastic, knife, and iron are all needed to provide protection. Simply measure, cut, and apply

Sheathed in plastic, a field map will survive water and heavy use

Then, avoiding bubbles and wrinkles, work hot iron out from center, join seams with transparent tape

Also, you might want to cut your map into smaller sections, allowing narrow spaces between them so that after lamination you can fold the map without actually folding the paper. Or, you can cut the map into sections and put them together in book fashion in a sequence according to how you will travel the area.

The lamination plastic is available in cut sheets or rolls and costs roughly 10 cents a square foot. The rolls are 11 1/8 inches wide, but the shortest length is 50 feet. Once you use it, however, you may think of other projects needing protective covers, so the length may not be a drawback after all. The narrow width of the roll will almost certainly require seams, so unless you work it out so that the seams coincide with the cuts in the map, it is then best to overlap the edges slightly to insure a watertight seal. Directions on how to use this material come with the packages, which can be obtained from school-supply firms.

Another method is to use adhesivebacked plastic, such as clear contact paper. With this type, you simply peel off the backing and place the plastic over the map and press it flat, again being careful to avoid bubbles and wrinkles. This material is a little more costly, but for the small amount necessary, it might be worth it. This, too, comes in sheets or rolls.

Remember that both the front and back of the map must be covered to make it waterproof.

Perhaps the easiest method, but which offers the least protection, is to spray your map with aerosol waterproofing. Most spray-paint manufacturers have products on the market known as clear plastic, clear lacquer, or silicone. Give both sides of the map one or two coats of this spray, and it will last fairly long.

Another process used to make a paper map more-or-less permanent is to give it a cloth backing. Again, the map can be left in one piece or sectioned, so that when you fold it, only the backing is creased. This cloth backing is available complete with adhesive backing for easy application. Or, you can use any light cloth, such as cotton muslin, and apply it with waterproof glue. Then the cloth-backed map can be sprayed with waterproofing for additional protection. Seal, Inc., of Derby, Connecticut 01648 is a source for plastic and self-sticking cloth.

Regardless of which technique you use, you'll head into the boonies feeling much more secure knowing that your map will last the outing none the worse for wear. THE END

Be Prepared

Safe vacations are no hit-or-miss affair. Certain precautions will assure a happy journey

ACCIDENTS AND ILLNESSES don't take vacations. People do. Whether you're taking a weekend jaunt along the Blue Valley Trail or a several-week trip to the Pine Ridge, the Nebraska Medical Association suggests forethought and planning to prevent illness or an accident from tagging along. Plan ahead to leave home with peace of mind. Take your time in traveling, and pace yourself throughout the trip.

Longer trips take more planning. Before you leave home, make a list and check off such items as canceling milk, newspaper, and bread deliveries. Notify your post office to hold your mail. If you can arrange to have a few lights go on and off with electric timing devices, your home will look lived in and discourage prowlers or vandals. Arrange to have the lawn mowed. Leave your key with a friendly neighbor or relative so you can relax and travel without worries about your home. And, you should notify the police department that your house will be unoccupied. Valuables should be stored atyour bank.

Before you leave home, have your car thoroughly checked, including brakes, battery, tires, headlights, tail and stop lights, directional signals, steering mechanisms, exhaust system, horn, and emergency brake.

Up-to-date family immunizations mean worry-free travel, too. If your family has a regular health checkup program, your immunizations will be current, including diphtheria, tetanus, polio, and measles.

One disease which is often vacation-related and which can be prevented with immunization is tetanus, or lock jaw as it is commonly called. Lockjaw is a vicious killer, striking down more than half its victims. Many adults forget to get a tetanus shot, but they should have a booster every five years.

If a member of your family requires special medication, make sure you have an adequate supply for your whole trip. Ask your physician about any special protection you may need for traveling into certain areas. You may wish to take an extra pair of prescription sunglasses and allergy medicines if the vacation climate requires them.

There are 40 million people in the United States who have medical conditions which need some special attention in emergencies. When traveling, the Nebraska Medical Association urges use of medical identification that communicates this information.

In 1961, the American Medical Association and other interested organizations discussed ways to identify a person's medical needs in emergencies. The AMA designed a symbol and offered it to all who publish cards or make signal devices. Whenever the emergency symbol is seen, it is an indication that there is important information regarding the wearer's health somewhere in the victim's clothing.

The symbol is a six-point star of life with the snake-entwined staff, symbolic of the medical profession, framed in a hexagon. The symbol can be used on pendants or bracelets.

Unfortunately, many people who may need special help do not wish to be identified as having a problem. For instance, some epileptics may be torn between the need for identification during a seizure and the fear of social stigma by identifying themselves as epileptics.

The association suggests that young children wear identification tags, particularly if they do not talk yet. Identification is suggested not only during travel, but also at home in case the child gets lost.

Free medical identification cards and signal-device information are available. The cards give name, address, physician's name, some basic medical information, and the name of the person to notify in an emergency. The cards and signal-device information are free upon request from the Nebraska Medical Association, 1902 First National Bank Building, Lincoln, Nebraska 68508.

Be sure to pack first-aid supplies last in your travel gear, so you can reach them first when you need them. Small first-aid kits are acceptable for minor scratches and burns, but not for major injuries.

Pack an American Medical Association, American Red Cross, or Boy Scout first-aid manual. Add bandage or blunt scissors, fever thermometer, one or more enema packages, one roll of one-inch finger bandages, one roll of twoinch roller bandages, one plastic bottle of tincture of green soap, a package of double-ended cotton applicators, a package of cotton "pickers", and a package of sterilized gauze squares in envelopes.

Your kit will need a roll of one-inch zinc oxide adhesive plaster, a plastic bottle of eye drops (prescribed by your physician) for use after a sunny, dusty drive, and an eight-ounce plastic bottle of isopropyl alcohol (70-percent grain alcohol) for skin disinfection.

Once assembled, it's easy to replenish your first-aid kit as needed. Plastic bottles are safer than glass.

Emergency equipment for car travel includes at least six triangular bandages. You should store some pieces of wood in your car trunk to be used as splints. Pack a blanket, too, for emergency care.

Your automobile should carry a flashlight with fresh batteries and highway warning signals or warning lights for emergencies. When you're on the road, pace yourself and your family for a comfortable journey.

Check the food and lodging on the road by the overall cleanliness you observe for yourself. A good restaurant needn't be fancy or expensive, but cleanliness is an important factor in maintaining good health standards.

When you're traveling in a strange community and an emergency health problem arises, the emergency room of the nearest hospital is a safe place to find treatment or advice. You can call the local medical society, if the town is large enough to have one, or the public health department. These organizations are available to help you find a physician in an emergency.

Your general health and the way you feel probably have as much to do with a successful, fun-filled trip as anything else. Regular health checkups and preparation before you leave home, are the first steps to happy traveling.

But, remember that even good preparation is not a substitute for careful driving. Add planning and preparation to a careful driver, and you're on your way to a happy, healthy Nebraska vacation. THE END

Wipeout

With a stretch of the Snake River unexplored, this intrepid team sets out to chart its rapid stretches. But, even professionals have their limitations, it seems white waterCANOE EXPERTS STRONGLY agree that white water is for experts only. The amateur, they preach, is heading straight for trouble when he tackles a stretch of rough, white water. This sageness takes us back seven years to adventure on the thundering current of Nebraska's Snake River.

The story really began when veteran outdoorsman Lou Ell, NEBRASKAland's chief photographer, challenged a stretch of the Snake River below Snake Falls in Cherry County. Lou had planned to ride the river from the falls to its confluence with the Niobrara, a distance of about eight miles, but the river was too spirited for him, so after several dunkings, he gave up the mission.

Canoeing enthusiasts from across the state had prompted the attempt with inquiries to the Game and Parks Commission about the navigability of that stretch of the Snake. The Commission was unable to respond because no one had traveled that portion of the stream. Then the experts appeared.

We pick up the action of the Snake River Canoeing Expedition on a clear morning in mid August, 1965. Assembled on the east bank of the river, fully equipped and ready for anything, are Dudley Osborn, Boating Chief of the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission; Jim Nelson, Midwest Regional Boating Co-ordinator for the American National Red Cross; Ted Dappen, Director of Public Health and Safety with the Nebraska Department of Health; and Ted's son, Leon. All four are certified small-craft safety instructors, certified Red Cross first-aid safety instructors, Red Cross approved lifeguards, and veteran canoeists. Photographer Lou Ell looms in the background loaded with cameras and memories of his earlier, unsuccessful attempt to conquer this portion of the Snake.

Lou's warnings about the river's treacheries and the difficulties the expedition will encounter fall on deaf ears.

As Dudley says: "There isn't much luck involved in mastering a fast bit of white water. It's their knowledge and experience that take good canoeists through safely."

The early morning sun sets fire to the crimson sumac dotting the rolling Sand Hills as the foursome unpacks gear. Talk about thorough preparation. Nothing has been overlooked. The canoeists have extra clothing, food, water, matches, first-aid equipment, blankets, and ropes. All supplies are stored in waterproof, steel canisters.

The fellows unload two 17-foot aluminum canoes together with their paddles. The superb organization and teamwork of the expedition is obvious as the unloading process is rapidly completed. Next, they launch the canoes. Most outdoorsmen would have been stumped, but not this team. It is about 100 feet from the top of the bank down to the water —straight down. Leon calmly opens one of the canisters and removes a rope. Within minutes the canoes are down on the water and ready for the journey.

With all the equipment, it looks as if the trip

will last weeks, but the experts estimate they will

cover the eight-mile stretch in about 4 hours. It is

0800 hours when the expedition takes off. Dudley

Lou runs along the cliffs shouting: "Wait, dammit! Wait up!"

The Snake is running full guns as the water churns through the 15 to 20-footwide rocky riverbed.

Then it happens.

Canoe No. 1 rounds a bend in the stream about 400 yards from the starting point. Canoe No. 2 falls behind. When it follows round the bend, Dudley and Jim are struggling to drag themselves out of the river. Canoe No. 1 is upside down and trapped by the pressure of current against a rock.

Ted and Leon quickly land and help the drenched pair get ashore.

Wet and cold, Dudley holds his right leg below the knee, a horrified look of anguish on his face. Dudley's leg swells to horrendous proportions and everyone, including Dudley, is certain the leg is broken.

While Jim explains what happened, Ted splints the injured leg. The leg is not cut open, but it is the worst contusion Ted has ever seen.

"We hit a rock," Jim says. "The canoe glanced off the rock and we lost control. The current smashed us into that windfall. Dudley stuck out his leg to avoid it and got his foot tangled. That upset the canoe."

Ted knows the twosome must have been moving very fast to be thrown like that, since Dudley tips the scales at 275 pounds and Jim at 200.

"We'll have to get Dudley to a hospital," Ted announces after splinting the leg. "I'm afraid it's broken."

Dudley's leg continues to swell unbelievably as the men make plans to get him to a doctor. But, in escaping from the grip of the powerful, cold current, Dudley and Jim have crawled onto the west bank while the cars are on the east, so they have to get Dudley across the river. And, once they get him across, they have to, somehow, get him up a steep embankment.

A plan is quickly put into action. Leon ties one end of the rope to a tree on the west bank and swims across the stream with the other end. He makes it across, but the current has washed him downstream. Finally, he works his way back to a point straight across from his companions and secures the rope to a tree on the east bank. Ted has emptied canoe No. 2 by now, so he and Jim load Dudley into it. The plan is to take the canoe across, hand-over-hand on the rope.

Everything is set. Dudley lies sprawled in the middle of the canoe, half unconscious from pain. Ted is in the bow and Jim in the stern. They cling to the rope and begin pulling the canoe across the stream. Things go well for the first three seconds, but when the canoe goes into the current broadside, the water threatens to upset the craft. To counteract the water's force, Ted and Jim lean upstream. But the counteraction is too much. Water washes in and sweeps the canoe away from under the trio of sailors.

Leon gasps.

The cold water brings Dudley around just fast enough for him to grab Ted's belt. Ted clings to the rope for his life. Jim reacts too slowly to catch the rope, but manages to catch a hold on Dudley's left, uninjured leg. Like a kite in a gale, Ted is the kite, hanging onto the stretching rope with Dudley and Jim awash in the current.

It is a life-or-death situation. If Ted lets go of the rope, the water will dash the trio against the rocks. Ted and Jim might live through it, but Dudley's chances are slim.

Ted gives his all to pull himself and his 475-pound cargo to shore. By this time Lou has caught up on shore by running along the bluffs. Leon and Lou then plunge into the stream and help tug Dudley and Jim onto the bank when they come within reach.

Heaving a giant sigh of relief, Ted gets to his feet. Thinking out loud he says: "If anything worse could happen today, I don't know what it could be."

The crew ties a rope to the trapped canoe, trying to pull it off the rock. All pull on the rope, fighting a tug of war with the current.

The rope breaks suddenly and Ted falls. A piercing groan indicates that the fall is a hard one. He struggles to stand, holding his side with both hands. The hatchet secured to his belt has come up against his ribs. Its sheath has prevented a serious tragedy, but the ax has, nonetheless, delivered a painful blow to Ted's ribs, and the injury takes its toll by reducing his strength and output for some time.

Hospital staff treats injuries but chuckles into sleeve while doing so

Leon retrieves the rope by taking himself, hand-over-hand, to the other side of the river, untying it, and swimming back to the east side. He climbs the bank and ties it to a tree. Ted, Jim, and Lou then get Dudley onto his one good leg and the four of them start up the incline. Fortunately, the bank is loose enough for them to dig toeholds as they go. Also, the bank is covered with bushes for them to grab for support. As they go up the hill, Dudley pulls on the rope, Ted pushes Dudley's right hip and Jim the left, and Lou pushes from behind.

Everything goes smoothly until Jim reaches for a wild rose bush. As the thorns dig into his fingers, he hollers and lets go. All of them tumble down.

There they are, all in a heap about halfway up the hill, but there is no time to commiserate. The only thing to do is pick up and keep going. Ted climbs to his feet and starts pushing Dudley. Jim doesn't move. "Get up!" Dudley yells.

"I can't," is Jim's muffled response. "You're sitting on my head."

With Ted's help, Jim finally squirms loose. Then, after much ado, they continue up the hill.

About 10 minutes later, the bedraggled foursome reaches the top. By this time, Lou goes after one of the cars and brings it as close as he dares, but that is still 200 yards away. Rough, Sand Hills terrain prohibits him from driving any closer.

So it's off to the races again. Leon and Jim hook hands and Dudley plops down on the chair they form. Away they go. Just walking on such terrain is a task in itself, but for Jim and Leon, carrying a 275-pound cargo is something else. Those 200 yards are the final test on their endurance.

A few minutes later the foursome is on its way to Valentine's Sand Hills Hospital.

Here ends the action of the Snake River Canoeing expedition, but there is an epilogue. Upon arrival at the emergency entrance, (Continued on page 61)

Rabbits Foot

Wild Four-o'clock

Sumac

Wild Raspberry

Coralber

Gourd

Wild Licorice

Honeysuckle

Spurge

Blue Flag

Wild Sage

Milkweed

Ponca Cures

Indians knew nothing of white man's medicine, but kept healthy for eons on concoctions provided by natureTHE CORNER DRUGSTORE was the medicine lodge; the pharmacist a medicine man. His pharmaceuticals included herbs of every sort for every purpose, and a series of mysterious incantations and spells to ward off disease, carry away spirits, or induce the presence of benevolent powers. The Ponca, living near present-day Niobrara when the whites arrived, had access to numerous wild plants. Already cultivating crops for domestic use, the tribe was able to supplement its wild diet with such things as corn and pumpkins. But, with incomplete scientific understanding of their world, the Indians found various supernatural explanations for natural phenomena quite reasonable. While white doctors practiced "scientific" bleeding and leeching, the Ponca used herb cures together with burning and cutting to take care of their sicknesses.

The Ponca recognized two types of illness, one resulting from natural causes, and the other caused by sorcery or the displeasure of the spirits. Natural illnesses and accidents were treated therapeutically with splints and herbal concoctions. But illnesses caused by supernatural powers could only be treated with stronger counter-magic. To the Ponca, magical methods were as reasonable as dressings for burns.

When a Ponca was bitten by a snake, he sent for a member of the Snake gens. When the "doctor" arrived, he dug a hole beside the fire with a stick, then sucked the victim's wound to draw out the poison. The purpose of the hole is a mystery.

While modern medicine is still searching for a remedy for the common cold, the Indians had cures that, if not effective, were at least enough to keep the patient busy until the cold went away. "Cedar eggs", the fruits and leaves of the cedar tree were boiled together into broth designed to penetrate the body to cough-control centers. To clear up sinus congestion, there was the smoke treatment—cedar twigs were burned and the smoke inhaled. A blanket was draped over both fire and patient to keep medicinal fumes enclosed. Calamus root was chewed as a cough-drop substitute, and a decoction made from the rootstock was drunk as a cough syrup. After it conquered the cold, calamus doubled as a perfume.

Yucca was also used in smoke treatment, and Jacob's ladder provided relief for hoarseness when eaten. The prairie ground cherry, too, was used in smoke treatment, as well as the rootstock of the cup plant.

In addition to other cures, a cold sufferer might burn sweet grass as incense to induce the presence of healing spirits.

For general debility and languor, the Indians took the lower blades of beard grass, which they called red hay, chopped them fine, and boiled them to form a broth.

To cure fever or headache, the Ponca crushed seeds of columbine. They placed the resulting powder in hot water and drank the infusion. Beard grass was used for bathing in case of fever, and a cut was made in the top of the head to which a decoction was applied. A fluid prepared from calamus was drunk for the same purpose. A decoction made from blue cohosh root also brought down fever.

Prairie dog food, called vile weed because of its odor, was another headache remedy. It was reported to cause nosebleed, so the leaves and tops were pulverized and inhaled to cause the nose to bleed and thus relieve the headache.

It appears that the Ponca recognized pediatrics, as they listed different treatments for children's illnesses. The Indian equivalent of liquid baby-aspirin was wild licorice. The leaves were steeped and the resulting fluid drunk to relieve the child's fever. Root bark from the bur oak was scraped off and boiled, and the liquid given for bowel trouble in children. Wild raspberry root was similarly prepared and used.

Ponca children probably never faked a stomach ache to avoid distasteful chores, for the cure was stringent. Spurge was used as a remedy for dysentery and abdominal bloating in children. The leaves were dried, pulverized, and applied after crosshatching the abdomen with a knife and abrading it with another plant. The Indians said it caused a painful, smarting sensation in the tissue.

Cattail down was used as talcum on babies, and wads of it were used as diapers.

Puffballs were a styptic, especially for application to the umbilicus of newborns. To keep infants healthy, the mother needed to have sufficient milk, and to stimulate lactation the spurge was boiled to make a decoction that was drunk. An infusion made from the stems of skeleton weed was used for the same purpose.

A rudimentary obstetrical practice also showed up within the tribe. A root decoction made from the four-o'clock was drunk by women after childbirth to reduce abdominal swelling. Smooth sumac was used in a (Continued on page 60)

Cedar

Yucca

Beard Grass

Cattail

Leadplant

The House of Brownville

Efforts to revive a dying town are divided, and may be futile because of it. But, perhaps it is not just a local problem

WHAT MARVELOUS stories are told of Brownville; of its founding and growth; of the gentle men and genteel women who overlaid America's outback with a veneer of culture; of the bawdy houses and of rugged freighters who supplied an opening West; of a steamboat era that brought both commerce and romance. They tell of great men who called this southeastern Nebraska community home; of Robert Wilkinson Furnas, second elected governor of the new state; of T. W. Tipton and Richard Brown, who served in the political ranks of a state just born; of Captain Benson Bailey whose ghost still haunts the halls he knew so well. How grand it must have been when Brownville was a thriving metropolis. And, what a sad experience it is today to see it the way it is, knowing all the while what it might have been.

Time has told on Brownville. It has become, instead of a cultural and historical center, just another small town in the throes of ebbing life. Many old houses, most of them dating back more than a century, still stand. There is a meager movement to bring Brownville back to life —to restore the dignity it once knew. That effort, though, may be not enough come too late, and Brownville is a town divided.

Some good, some bad greets the visitor. Goal is to eventually restore all buildings with taste

John Rippey heads struggling historical society's promotions

McKinley Kelley has watched town's life slowly ebb away

Although an improvement, new bridge is not a tourist treat

Tranquility and trash seem to coexist because of unconcern

The town has made some inroads to helping itself, according to Mrs. C. M. Miner, clerk of the town board, and John Rippey, president of the Brownville Historical Society. Installation of running water has made the town more livable, and a sewer issue was recently bonded. The local volunteer fire department has provided public trash containers, and halved barrels accommodate flowers annually. A modern, steel bridge has replaced a wooden structure which once spanned Whiskey Run, a stream running parallel to Main Street. Water, sewers, trash barrels, bridges, and flowers, however, are not the reasons Nebraskans stream to historic sites; cleanliness, organization, enjoyment, and a chance to see things the way they were in a pleasant atmosphere are. These things Brownville does not offer. Yet, amazingly, the town continues to advertise for visitors to come and see the place.

"Tourism today is considered one of the top businesses in the country," John Rippey said. "Tourism is big, and Nebraska has done very little about it. We have probably done more about tourism in eastern Nebraska —more than anybody else. According to the State Historical Society, we're the most active and productive [local] historical society in the state."

Active the historical society may be, but that is in spite of holdings that leave much to be desired. The park, ironically, was presented to the society rather than the town by the late George W. Boettner, a move which created considerable antagonism amongst the townspeople. It has become a flourishing dandelion nursery, and removal of dead trees and debris was a half-year project, a time span which resulted in a number of complaints from visitors. The society owns an entire block facing the south side of Main Street in the business district. And, it has the Wheel Museum, a shabby storefront, which also houses the society's headquarters. Besides that, there is the Carson House, an 1880's-vintage home which is slowly being restored and is one attraction on the abbreviated tour of homes. Then, there is the Captain Bailey House which serves as a museum. Given the historical significance Brownville has to offer, these properties aren't much for the town's major historical organization to control. They are, however, a sizable chunk of real estate for only a few people to maintain. The town, it seems, won't cross jurisdictional boundaries even in the name of civic pride —to lend a hand in keeping Brownville clean. Everyone points the finger at someone else and tries to rationalize.

"Brownville needs the historical society if they would keep up their property," Mrs. Miner offered. "But we don't like trouble. I certainly would like to make Brownville more palatable for the general public. We're trying to beautify it. We'll get our flowers out in our containers and do what we can."

Simply planting flowers won't overcome many of Brownvilie's shortcomings, though. Mrs. Miner explained that the town won't go into the park or any other of the historical society's properties to clean them up, and she indicated that the society wouldn't like it if they did.

"A man who works for both the historical society and the town does the mowing down there [the park]," Rippey explained. "The town doesn't move in on our property just as they don't on anyone else's. For instance, we [the town] have a piece of property where we've talked to the owner to get it disked and the weeds mowed and he does nothing."

"Of course, the town did pay to have weeds cut there, and he [the owner] refused [to reimburse us]," Mrs. Miner put in. "We are such a small place that it isn't recommended that we bother them [taxpayers] with a small item on the taxes."

There is no way to implement some of the zoning this town has unless the town board calls in a particular person and talks to them —which they have done on various occasions. But some offenders simply mouth them [the board] back, and give them a bad time," Rippey noted.

Words, rather than action, seem to have found a comfortable home in Brownville. The local volunteer fire department provided litter barrels around town. Then the trouble began. No one showed up at the appointed time to set them out, so one man painted and placed them. Barrels are fine and a (Continued on page 62)

Predator Control ... sin or salvation?

When and how to disturb nature's balance is management challenge

A PREDATOR is any creature that has beaten you to another creature you wanted for yourself. That definition probably won't appear in any dictionary, but it's an accurate description of how many people think of predators. Although it is true, it isn't the whole truth. From a broader view, "predation" is getting food by killing other animals, and any animal that does so is a predator. Many creatures must get their food in this way to survive. Examples are bass eating minnows, swallows catching flies, coyotes killing rabbits, and hawks taking mice. Predation is, therefore, a way of life that is both natural and necessary.

The predator "problem" has to be as old as man himself. Initial forms of humanity probably exhibited some kind of resentment as they watched a large carnivore carrying off a highly prized food animal. Even worse, man was once the prey. Primitive man was as much a predator as the other wild animals around him, and his modern descendant is still a predator although probably not in the same critical way. Eating beef and chicken or hunting a wild animal is actually a form of predation. But, when a hawk catches a chicken or a coyote takes a lamb — that's different. The difference is that the creature killed was one we wanted for ourselves, and that is what many consider predation.

It is important to recognize these two views and the difference between them. Both are right, as far as they go, but neither ventures far enough to form a good basis for predator management. Both views have to be considered before an effective way of managing predators can be worked out. It is impossible to do justice to all man's interests, or to the animals themselves, by managing on the basis of either viewpoint alone.

Probably no topic in the wildlife field is more controversial than that of predator management and control, due largely to the wide variance of viewpoints. Some sportsmen resent the competition of predators for game or fish. Some farmers and stockmen whose cattle, sheep, or poultry losses are a direct economic liability become disturbed. There are people who believe that nearly all animal species should be given complete protection, whether they are predatory or not. The game manager's job is to provide the greatest possible number of various species for recreational purposes. The ecologist looks at all possible effects of predation, beneficial and harmful, in an attempt to establish the economical status of the species involved. There are people who believe that predator control is necessary in some cases, but disagree with the methods and techniques being used. There is a group of people that can be considered indifferent since they never hunt, fish, raise livestock, or commune with nature, and care little one way or another whether predators are killed.

One of the most widely used arguments opposing predator control is that these animals are essential in maintaining a "balance of nature". Proponents of this concept feel that without a balancing effect many injurious animal forms would increase to the point of being detrimental to man. They also contend that unless beneficial forms are held in check, they will outgrow their food supply and eventually starve.

Predators perform a valuable sanitation service to some prey species by eliminating the crippled, diseased, and unfit, thereby contributing to the health, physical condition, and perhaps the survival of the species. It is possible that the elimination of the unwary, slow, and stupid individuals by predators will improve or maintain the sporting qualities so desirable in a game species. Predators also kill and eat many harmful rodents each year, and in so doing perform a vital service to humanity. The total dollar-and-cent value of this accomplishment has been placed in the millions of dollars.

An argument that is being used against predator control to a greater extent these days is one that can be termed as aesthetic appeal and recreational (Continued on page 64)

The Forest is Alive

Ecologically unique, Indian Cave State Park pulsates with life as spring is ushered inLIKE A SWEEPING WIND caressing a meadow, the crescendo spreads, engulfing the humid woodlands. In eerie chorus, the melodious proces-sional of Indian Cave's arboreal frogs usher in the darkness. Though near, whip-poor-will calls maintain a distant quality, though intense, a sound of solitude. The decadent sweetness of moist earth permeates the twilight, vagrant scents offering no hint of their origin.

Sleep comes easily.

A spring shower intrudes on the predawn hush, erasing all tracks the night creatures left. But then, glazed, greening herbs greet the sun; refractive prisms cling to blue-eyed grass.

In the Missouri bluffland it is a time for proliferation —the season to replenish. Flower tendrils drop from huge oak limbs and pollen-laden catkins of the black willow thrust bold yellow into deciduous green. Rust-colored sheaths peel away as lobate hickory leaves reach for the forest's canopy.

Vibrant forms spring from the earth's richness. Pantalooned Dutchman's breeches hang pendulously like Monday

Flicker is a noisy member of the forest

Rich in bird life, the Missouri biuffiand entertains species that are unusual in the rest of Nebraska's flood plain forests

Foggy shrouds nourish luxuriant foliage

From the top of the highest tree, a dickcissel announces morning

The mew of catbirds is common in bluffs

Numerous turkey vultures ride the rising air currents

Showy orchis is an uncommon find

Golden ragwort is common

Phlox and jack-in-the-pulpit dot woodlands

Papaw tree has unusual bloom

Drooping bells and recurved spurs help identify the columbine

Amphibians and reptiles occur

along the Missouri River in variety

of forms, and in abundance

A vast reservoir for wild

things, a river's forested fringe

harbors the inconspicuous

and obvious on equal basis

Amphibians and reptiles occur

along the Missouri River in variety

of forms, and in abundance

A vast reservoir for wild

things, a river's forested fringe

harbors the inconspicuous

and obvious on equal basis

Decayed wood hosts delicate fungi

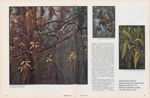

Oaks and hickories crowd the bluffs

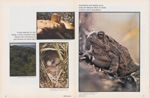

Meadowlark incubates not only its own eggs but a cowbird's as well

Toads, like this Rocky Mountain, prey upon multitudinous insect forms

Like falling rain, the oaks shower their progeny upon the earth

Hickory leaves emerge from sheath

morning labor. Shin-high blankets of Mayapple and phlox cover the forest's floor. Spiraling cones of compressed petals, sheathed in pubescent sepals, promise sweet William blossoms tomorrow. Plumb-bob buds foretell white disk flowers to adorn the Mayapple's foliage veil. The delicate charm of a yellow lady's slipper or showy orchis clashes with the massiveness of hardwood giants overhead.

Shagbark hickories slough their ragged bark while red oaks tower nearby with skin as smooth as a baby's cheek. Papaws stand naked, their fleshy red blossoms ornamenting their leafless forms. Wild crab apple, Kentucky coffee, and redbud complement the rugged bluffland.

Oak leaves rustle in an abandoned orchard. Grosbeaks, towhees, and oven birds probe for last autumn's seeds. Woodpeckers shatter the noonday lull as they fashion accommodations for squalling clutches while turkey vultures soar overhead. Even woodcocks and ruffed grouse occasionally inhabit this untouched backland.

A gray squirrel issues a boisterous challenge to intruding neighbors and a flying squirrel touches treetop after treetop. Whitetails nibble on flowering heads.

Circular land snails pass the day, unmindful of the life around them.

Clouds build. An afternoon shower nears. The Missouri bluffland pulsates.

The forest is alive! THE END

Willow catkins hang like golden pennants

Hooked on Carp

Long ignored, these fish deserve more respect They grow big and tough, yet come to hook easilyTHE CARP, a member of the Cyprinidae family, is a freshwater fish now acclaimed in all parts of the world. It is an Asiatic minnow, one of more than 200 species found throughout the world. The National Wildlife Federation acclaims it as a monstrous minnow. Europeans breed the carp for gourmets, and in the Far East it is an important food.

According to the National Association of Angling and Casting Clubs, the world's all-tackle fishing record for a carp caught with rod and reel in fresh water is 50 pounds, 6 ounces; length 46 inches; girth 35 inches; taken in 1951.

A carp's color is brassy olive above, yellowish on the sides, and yellowish-white on the belly with the lower fins tinged red. From its upper jaw protrude 4 barbels, which are sensitive tactile organs. The skin texture varies widely. In addition to the ordinary scaled carp, there are two other varieties —the mirror carp, which has only a few patches of scales, and the leather carp, which has no scales at all. Some carp in certain areas lack pelvic fins. Also, in some areas, the carp may be confused with the goldfish and the buffalo fish. Carp can reach prodigious size and may live for 200 years.

Female carp mature in about 3 years. Spawning takes place in spring where conditions are such that the eggs can be laid and fastened to aquatic weeds. The eggs are small and number between 300,000 and 750,000 a season. The carp can endure extreme weather conditions and temperatures. During the winter months it hibernates and does not take food. So hardy and rugged is the carp that it may be kept alive for days in moist moss if properly fed.

Carp are omnivorous, in that they will eat anything animal or vegetable. They feed on insect larvae and aquatic plants, worms, (Continued on page 58)

Robin's-egg-size doughball is dependable bait. Carp nuzzles it, then heads out, promising angler battle

Snipes Turned Ducks

THE GRAVELLY RESONANCE of mallards filtered through the golden willows like a chorus of hoarse baritones. A false dawn spread in the east; the windless air hung listlessly. Had the pond's water remained high, our stalk would have been as easy as falling off a log, but now open sand flats ringed the water's edge for 30 feet or more, lowering our odds of working within shotgun range. Even that was not as much a hindrance as the carpet of snail shells that blanketed stubby grass around the pond's edge. Every hand and knee, however carefully placed, crushed hundreds of the crusty bodies. Every crunch seemed amplified by the dead-still morning. Most of the mallards were on a sandy peninsula that jutted from the bank: some were feeding in the lush aquatic growth, others were preening, and some were just resting in the typical head-back position. Thick willow growth would conceal us to within 25 or 30 yards of the unsuspecting ducks if we were "Indian" enough to work in that close.

But patiently waits on the bank as I retrieve mallards jumped in the reeds

and we were trying to decide how we had spooked the mallards when

more birds struck up a conversation of their own just in front of us.

and we were trying to decide how we had spooked the mallards when

more birds struck up a conversation of their own just in front of us.The first bunch had probably moved out to feed, and our flock would likely follow any time. We pressed ahead faster —too fast!

The birds left the water low, arrowing toward midlake. By the time we could see the flock above the willows, the birds were well beyond range. We had bobbled our morning jump action, it seemed.

The ducks had been there, the terrain was perfect for a stalk, but the lowly snail and a calm morning had defeated our ambitions.

Bud Pritchard, NEBRASKAland artist and illustrator of the fauna/flora series since 1949, Greg Beaumont, magazine photographer, and I had made the 5-hour trip to the Valentine area early in the week, hoping to take enough Wilson snipe for a story. Some 10 years earlier, Bud's snipe hunt at Ballards Marsh had been featured in NEBRASKAland. What we planned was a nostalgic return to sample the snipe hunting and record the changes, if any, that had taken place over those 10 years.

Bud had wanted to hunt in early October, since that's when snipes peak during their holdover stint in Nebraska's marshland. Assorted delays and unplanned assignments, however, delayed our trip and we didn't get to Valentine until October 19, three weeks later than planned.

We stopped at Ballards Marsh, a state special-use area 20 miles south of Valentine, on our way into town. Our first survey of the wetland was disheartening. Late summer and early fall had been dry. As a result, the mowed-grass fringe that bordered the rank growth of cattail and hardstemmed bullrush was barely moist. Where this lush, short grass is slightly flooded and trampled by livestock is prime snipe country. Here the birds feed on insects and small crustaceans, and generally loaf during their southward migration, but the dry spell had wiped out most of that habitat as well as our chances for snipe. That, coupled with the fact we were three weeks late, put the kibosh on our return to Ballards Marsh.

A call to Elvin (Zeke) Zimmerman, conservation officer in Valentine, confirmed suspicions that our snipe hunt had gone down the drain. But, it also suggested an alternative we hadn't considered. According to Zeke's report, there was a substantial supply of ducks on the potholes that sprinkled the area, mostly mallards reared in the Sand Hills and loafing until colder weather. A few small flocks of diving ducks had moved in from the north, too. So, overnight, our snipe-at-Ballards-Marsh hunt had turned into a ducks-anywhere-we-could-find-them story.

Zeke recommended we check some of the lakes south of Nenzel first thing in the morning, as they had been holding good numbers of divers, mallards, and a few gadwall. Schoolhouse, Two Mile, and Medicine lakes were our morning's objective.

On the way through the Niobrara Division of the Nebraska National Forest, we stopped to talk with John Nollette, the ranger in charge of the area, quizzing him for suggestions.

"You might have a look at some ponds in the eastern part of the forest," John suggested. "Usually they hold a few mallards that rest overnight. If you get there by midmorning, there are usually a few stragglers still in the area. It's only 8:30 now. You might catch a few there yet, if you hurry."

We didn't let any grass grow under our wheels as we hustled over for a look at the area. Our scouting plans were soon adapted to include a short hunt if the possibility presented itself.

Perhaps our eagerness, coupled with visions of greenheads piled at our feet, accounted for the mammoth blunder we pulled, but I would rather place the blame on Greg, a great photographer, but a bit naive when it comes to duck hunting. Of course, Bud and I wouldn't have had to take his advice when he encouraged us to drive closer to the lake before hoofing it. But, wherever the blame should have fallen, the whole raft lifted, circled once, and left high when we drove over a rise in full view of the ducks.

On the eastern side, half a dozen buffleheads were still feeding. A high bank behind them would offer excellent cover. Though neither Bud nor I were especially crazy about eating a bunch of butterballs, I decided to try and take the drake and a hen, both 10-pointers, to add to my collection of mounted waterfowl. Bud passed on the divers and opted instead for a handful of teal that had settled in on the west pond while we were talking. So we split, Bud after teal, I after the buffleheads.

Greg, armed with only a camera, followed me, probably assuming that I was a better bet for a laugh than a salty old hunter like Bud. But whatever his reasoning, we made a wide arc behind the closest hill and came around on the east end of the lake. As I eased up over the bank, I could see that they had moved out about 15 yards. Those 15, added to the 45 or so of sandy bank, put the birds just outside my range. We sat and watched the birds bobbing about, making their occasional dives. I began measuring the length of time they stayed submerged. Usually, they were under for 10 or 15 seconds, sometimes 20 or more. I was more interested in the attractive (Continued on page 57)

Windmill is an ideal site for picking, and for swapping a few hunting yarns

Finally we find small lake loaded with ducks

Dense stands of bullrush provide enough cover to afford Bud some pass shooting

I throw out decoys in vailn effort to attract puddle ducks

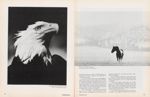

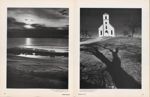

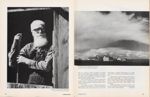

Shades of Gray

Moods of man and beauty of beasts are best captured in spectrum of black-and-whiteBarbra Burch introduces Ogallala's annual Little Britches Rodeo

PHOTOGRAPHY has evolved, step by step, from the first discovery more than four centuries ago that light darkens silver salts to the modern methods of producing color pictures in a minute. In the process, many techniques have been developed for the purpose of duplicating as accurately as possible what the human eye sees, or even capturing what the untrained observer misses.

Open sky will soon be lost as thunderhead builds at Branched Oak

Not bald at all, eagle gets its name from its almost-white hackles

Distance and dismal weather set mood for pinto at Fort Robinson

He uses screens to make stars of streetlights at night; filters to turn ordinary skies bold and blue. He captures lightning by immobilizing his camera on a tripod for minutes, sometimes even hours, or stops the swiftness of a teal on the wing by panning its flight. These and many other techniques he uses to capture on film what the human eye sometimes perceives as only a moving flash.

Other techniques he employs to penetrate haze or, if he wishes, distinctly define a hazy cloud. There is seemingly no end to the list of methods whereby he can enhance what is ordinarily not noticed.

But, while great emphasis is placed on color today, there is still much to be said for black-and-white photography and its mood-capturing capabilities.

Take, for example, a pinto pony in a winter storm. Its black-and-white markings stand out against the muted background of snow-covered hills rolling away to a horizon obscured by distance and dismal weather. It evokes a mood that would surely be lost in color.

Big Mac's breaking ice asks waning warmth of setting sun to stay

Inert Cottonwood's shadow reaches out like sinner seeking solace

Active as ever at 69, Bill Gronewold of Blue Hill still works his spread

Promising rain as a premise for survival, clouds hover over Chadron farmstead

The eerie shadow of a dead cottonwood creeps toward a deserted country church like a sinner seeking salvation, but the symbolism would be lost in color.

A formation of stratus clouds hovering over an abandoned farmstead is an omen bespeaking the burdens of the small-time farmer in an era of urbanization. Colorful surroundings in a photo such as this would destroy its atmosphere of loneliness.

Ultimately, the choice between color or black-and-white photography is a matter of personal taste. One person responds to the brilliance of a sunset, while another prefers the subdued shadows of a fallen log barely visible beside a lake in twilight.

Color photography certainly has its place, but the art of black and white with its varying shades of gray must not be forgotten. THE END

NOTES ON NEBRASKA FLORA... Bur Oak

Giant in stature, tenacious by nature, these Titans were among vanguard of trees on the plains. Found along state's larger streams, they may reach 80 feet in heightTHE EXPRESSION "solid as an oak" is a very appropriate phrase. The bur oak, Quercus macrocarpa, is a good example of strength and solidness. It is a pioneer in the advance of the forest upon the prairie. The bur oak is distributed along practically all the larger streams in Nebraska and is often found surviving under conditions which would seem too severe for tree growth.

The bur oak, sometimes called mossycup oak or overcup oak, is a sturdy tree with large, heavy branches and stout, somewhat sparse branchlets. In close stands of timber, the tree is irregular in shape and has fewer and smaller branches. Isolated trees develop a more rounded top and are often broad rather than tall. It commonly reaches a height of 60 to 80 feet with a trunk diameter of 2 to 4 feet.

The bark on mature trees is grayish or reddish brown in color. The surface of the bark is flaky and deeply cut into wide fissures dividing broad, straight ridges with flat surfaces. Large trees have bark about 1 1/2 inches thick which make the trees fairly fire-resistant.

Another distinguishing feature of the bur oak is the corky wings frequently found on young branches. These wings, or ridges, usually begin to form the third or fourth season and remain for several years. As the branches become older, these ridges gradually disappear.

The bur oak is slow to leaf out in spring. But, although so slow to bud, they are also slow to die and may live three centuries. Leaves of this tree, largest of all the oaks, are normally 6 to 12 inches long and 3 to 6 inches broad. The thick, firm leaves have a shiny, dark-green upper surface and silvery green and downy lower surface. These leaves characteristically have 5 to 9 rounded lobes which give them a peculiar, unmistakable outline. On each side of most leaves near the middle, a deep, rounded sinus reaches almost to the center, which practically divides the leaf into 2 distinct parts. In autumn, leaves turn a soft, dull yellow. Then the fox squirrels go rippling through the branches, gathering acorns for their winter store. Later, when Indian summer is over, the leaves fall early and the bur oaks take on a closedup, steely look.

Flowers of this and other oaks usually appear in May when leaves are about a third to half grown.

The acorns from which the great oak stems are usually oval shaped and are three-quarters to two inches long. The scaly and hairy cup which normally covers half or more of the acorn gives the name bur oak. The scientific name, macrocarpa, also refers to the acorns and means large-fruited. The exact shape of the acorn is quite variable but the large, fringed cup is unmistakable.

Acorns are commonly found in pairs and ripen in the fall. Acorns drop from the trees as early as August or as late as November and provide a staple food for many forms of wildlife, including deer, squirrel, bobwhite quail, numerous songbirds, and small rodents. Transportation of the acorns by squirrels is one of the primary means of dissemination of the seeds. The acorn is edible by humans and was used to some extent as food by early man. The flavor of the acorn varies, some are quite bitter while others have a sweet, nut-like taste. Good crops of acorns occur every 2 or 3 years with light crops in the intervening years. Although 30 percent of the acorns germinate within 1 month after seedfall, they are often subject to serious depredation by animals, especially rodents.

Root growth of seedlings is very rapid and the taproot penetrates deeply before the leaves unfold. At the end of the first growing season, roots have been found at depths of 41/2 feet with a lateral spread of 30 inches. This strong, early root development explains why a bur oak can be a pioneer tree on dry, exposed sites and can successfully establish itself in competition with prairie shrubs and grasses. The root system of a mature tree resembles a mirror image of the mighty structure above ground.

The use of oak for lumber has had its heyday. At one time it was used extensively for construction of barrels and in the ship-building industry. It is still used in construction of whiskey barrels and in the production of charcoal.

The bur oak is a relatively slowgrowing tree but is capable of withstanding a wide range of moisture and site conditions. It is seldom subject to serious injury by insects or to many diseases. However, livestock browse the leaves of seedlings and their hooves pack down the soil which has an adverse affect on the roots. It makes an excellent shade tree in full sunlight where growing space is not limited and the soil is rich, moist, and well drained. The bur oak is more tolerant of city smoke conditions than most other oak species.

The bur oak is a rugged tree. Its irregular form with rough bark and wayward limbs is picturesque. Like the hardy pioneers of early Nebraska, the bur oak, a pioneer of the forest, is a shining example of solidness, strength, and greatness. THE END

AUGUST 1972 50 51 NEBRASKAland

Roundup and What to do

AUGUST is traditionally a lazy time, with people seeking refuge from the summer sun at a shady fishing hole or in a breezy back yard. But, judging by this year's schedule of events for August, Nebraskans have livelier things in mind.

The August agenda includes all the action of rodeos, motorcycle rallies, horse racing, shooting events, and baseball. The lighthearted, gregarious nature of the state's citizens will be apparent, too, as Nebraskans gather for dozens of county fairs.

Standing guard over Nebraska's summertime fun is Tammy Hatheway of Lincoln, NEBRASKAland's August hostess. Tammy is a freshman majoring in speech therapy at the University of Nebraska and is the reigning Miss Nebraska Air National Guard.

She lists swimming as one of her favorite activities, and has served as a lifeguard at a Lincoln country club. Among her other favorite pastimes are golf and horseback riding. Tammy is the daughter of Mrs. Marge Hatheway of Lincoln.

Every weekend during August will find Nebraskans flocking to county fairs, with more than 40 of these events scheduled during the month. All this will lead to the biggest of them all, the Nebraska State Fair, opening August 31 in Lincoln.

Another August tradition, the Nebraska Czech Festival, will keep the town of Wilber hopping for two days, August 6 and 7.

August is a top month for fishing, if anglers are willing to switch tactics a bit. Lunker bass can still be coaxed from farm ponds and sandpits, provided fishermen are patient. And, rivers offer good cat fishing.

But the most successful fishermen will concentrate on the state's big reservoirs to capitalize on the fast and furious whitebass action.

Another form of fishing, one that is unfamiliar to all but a few citizens of landlocked Nebraska, will be underway during the month. Fishermen will don diving gear and take up spearguns to pursue their prey. Underwater spearfishing is new in Nebraska, but growing numbers are taking up the sport. Private lakes are open to the sport, along with 15 of Nebraska's reservoirs.

At Macy, the 105th annual Omaha Indian Powwow will bring to life the old days when the Indian was the master of the prairie. Some of the Omahas' ancient ceremonials will be relived during the 6-day celebration.

At Brownville, the Nebraska Wesleyan Players will provide another month of summer theater with some of the best student acting talent available. Meanwhile, in Lincoln, Theatre Incorporated will present another season of mellerdrammers filled with six-gun heros, lily-pure maidens, and black-hearted gamblers. During the first week of August the feature will include "He Lured Her To The Primrose Path" and "Shootout At Hole In The Wall".

More Old-West entertainment will come with the National Country and Fiddle Music Contest to be held at Ainsworth August 11 through 13.

The Franklin Fall Golf Tournament at Franklin August 20 will climax the season in that area of the state.

Flashing silks and flying hooves spell horse racing at Ag Park in Columbus from August 25 into September. With the experience of the summer behind them, the ponies will give their all to winning the daily heats at the track.

Spectators and participants alike will find August an active month in NEBRASKAland.