WHERE THE WEST BEGINS

NEBREASKAland

May 1972 50 cents 1CD 08615 Nature's Patterns A Boy's first hunt Bison Close-ups

No Place To Go With the benefit of hindsight, the tragic history of the North American bison and the struggle to preserve the species are explored

They're at the Post The sport of kings is centuries old, but through modern regulations, its popularity in Nebraska ranks it among our most exciting pastimes

Nature's Patterns Mother Nature's designs, from twisted cottonwoods to dewdrops suspended in space, are examined in photographs and prose

Dlme-a-Dozen Gun Nostalgia of a lad's first solo hunt recalls, for every sportsman, the memory of his own initial sojourn afield with a gun

Cover: Prairie spiderwort, also called trinity, is native across entire state. Pair of pelicans takes off into flight near Hyannis on page 3. Both photos were taken by NEBRASKAland's Greg Beaumont.

Boxed numbers denote approximate location of this month's features.

LAKEVIEW ACRES

ON BEAUTIFUL JOHNSON LAKE LAKE ACCESS IN FRONT OF YOUR LOT FOR DOCK OR RAMP CABINS WILL BE BUILT THIS SPRING FOR SALE FOR LEASING BY OWNERS FINANCING AVAILABLE ON LOTS OR HOMES. ALL LOTS ACCESSIBLE BY PAVED ROADS COMPLETE SUPPLIES AVAILABLE IN BAY AERA AT MARINA-BAIT-BOAT DOCKS-RAMP-GROCERY AND BEVERAGE SUPPLIES HOME OR CABIN LOTS NOW AVAILABLE Lots are ready now for building your cabin or home. Or buy lot complete with a Mobile Home ready to move in and enjoy. Private property area-regular home loans can be obtained. Restricted building codes to insure like quality for entire area. All Utilities are in and ready, Electricity-Gass-Water and Telephone. All lots have concrete retaining wall and shoreline. Protected cove area. FINANICING AVAILABLE Or call Bob Cupp, Mgr. Lexington, Nebr. 30/324-2678 Write For Free Color Brochure To LAKEVIEW ACRES, INC.For the record... Conservation Unity

A decade ago, the field of wildlife was assumed to be the sole province of sportsmen. Recently, however, those in the hunting and fishing ranks find that they no longer occupy an exclusive position. They are being joined and even jostled by new groups claiming concern for wildlife. In fact, controversies are erupting between established and somewhat complacent hunters and fishermen on the one hand, and the so-called protectionists on the other. Protectionists have probably been around for as long as sport hunters, but until recently, they have been relatively obscure. It is not surprising that in recent years there has been a sharp rise in both numbers of protectionists and their visibility. We are in a period when people feel keenly and sincerely their responsibilities for the preservation of natural things, and they are eager to make themselves heard by those in policy-making positions.

I do not feel seriously threatened by this controversy because I see in it the potential of an urgently needed coalition of interests. I seriously doubt whether protectionists alone can protect the interests of wildlife and habitat just as I also feel that sportsmen cannot do the job by themselves. In recent years, sportsmen have taken considerable pride in noting that licensed hunters and fishermen constitute about 20 percent of the nation's population. But the other side of the coin, which shows that non-hunters and non-fishermen make up 80 percent of our populace, has been consistently avoided. As long as the 80 percent remained disorganized and passive, hunters and fishermen presented an impressive force as wildlife protectors. But today the protectionist faction is neither totally disorganized nor passive. The 80 percent poses a powerful voice which is being heard by increasingly sympathic ears.

In the controversy, I see a possible change in the adoption of new yardsticks to measure wildlife values. I believe we are at last realizing that the universal use of economic criteria to define values cannot, in truth, fix the long-term priorities of today's society. The ultimate test is what people enjoy the most. This is a valid yardstick with which we must measure many of our wildlife resources. This is the yardstick that lends itself so admirably to the strength of diverse groups having a common concern for wild things.

I firmly believe that from the controversy now going on will come new public support and reshaped philosophy that will equitably embrace the full spectrum of ecologically sound interests in wildlife. The early 1970's will be recorded as an important transition period in conservation —hectic, but essential to the attainment of a new and broader perspective of popular appreciation for wild resources.

Our central concern, then, must be the perpetuation of a rich diversity of wild animals and environments, and the utilization of them for the betterment of present and future societies. The ecologically sound wildlife interest groups, whether they be sportsmen or non-sportsmen, have identical objectives. Collectively, we are indispensable allies capable of accomplishing our goals. But as separate, quarreling, go-it-alone interests, the prospect of success is dim indeed.

help pheasants have a population explosion!

Hold off mowing until July 15th. Early mowing of road sides, dry water basins, and odds-and-ends areas will cut the pheasant population.

For further Information write to: Acres for Wildlife Nebraska Game and Parks Commission P.O. Box 30370 Lincoln, Nebraska 68503Ecology for tomorrow's sake

JET FRONTIER Look what you've been missing

Only Frontier gives you first - class leg room plus twin-seat comfort at coach prices.Some airlines give coach passengers extra leg room and others offer a fold-down seat that provides extra elbow room when the plane isn't full. Frontier has taken these two popular features and combined them to offer our customers the ultimate in passenger comfort... at a price equal to coach fares in most cases

First class leg roomup to a big 39 inches to stretch in, front to back on every Frontier jet.

Twin seat comforta center table for your snacks, or puzzles or your elbow, folds up to form a seat only when the passenger load requires it.

Standard class fares... equal to coach prices in most cases but eliminating the multiple choice question when you buy a ticket on Frontier.

It all adds up to a lot of extras at no extra cost.

But you've come to expect that sort of thing from Frontier. The airline that offers first-class leg room plus twin-seat comfort at coach prices.

Next trip, give Frontier a try.

NEBRASKAland invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to SPEAK UP. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters. — Editor.

REPRINTS-"Do you have reprints available of the article Conflict in the January 1972 issue of NEBRASKAland? I would be interested in obtaining a number of them for distribution to local members of Prairie Audubon Society in Hastings. It is an excellent, impartial coverage of the three projects." —Elsie Rose, Hastings.

Mrs. Rose's letter prompted reprints of the article and they were sent to her. These are now available to other readers, free of charge, by writing to NEBRASKAland Magazine, 2200 North 33rd Street, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. — Editor.

REMEMBER WHEN- The article The Mill at Champion in January, 1971, recalled many memories for me. I was familiar with the mill many years ago and remember one incident well.

"My sister, Pearl, was a tall, skinny girl of 13 when she had a near-tragedy on the iron rods which ran from the mill to the big wheel. At the time, there were no coverings over the rods, but they were between large planks and rolled very rapidly. One day I was in my usual place by the big wheel, fishing with my younger sisters. Two neighbor girls and Jay Hoke were playing farther on. All at once we heard awful screaming and when we arrived there, Pearl stood in her long, white drawers, trying to hide herself behind her hands. Fortunately, she had on separate skirts, or she might have been drawn into the rods. Even at that, it took super-human strength to hold on until her skirts ripped off. When the miller stopped the wheel, and her skirts were unwound, they were all in tiny shreds. Someone ran up to the miller's house and borrowed a dress for Pearl to wear home. She was so embarassed at others seeing her in her drawers tbat shame dulled all sense of fear and tragedy, and the experience was seldom mentioned. Pearl would turn over in her grave if she knew the scarcity of pants on girls today. I mean underpants —I do not like pants on women."—Gladys Schaefer, San Francisco, California.

LOOK ALIKES- 'We thought you might be interested in the similarity of the enclosed snapshots. One is Hole in the Rock near Honolulu, Hawaii. The other is a point at Lake McConaughy." — Robert Osborn, Sidney.

Honolulu

Lake McConaughy

OLD PERMITS-"Recently, I came into possession of Nebraska hunting and fishing licenses dating from 1916 through 1958, with only 1954 missing.

"From 1916 to 1927, these read 'license' to fish and hunt. Those from 1928 to 1958 read 'permit' to fish and hunt with 1954 missing. I also have a 1923 license to trap.

"If there is any historic value to these, I would gladly part with them." —K. B. Mellman, Gothenburg.

The Game and Parks Commission is gathering such permits for a display which will ultimately be placed in the new headquarters complex in Lincoln. We are missing permits only for the years 1901 to 1906, 1909, 1910, 1963, 1967, 1968, 1969, and 1970, and would (Continued on page 8)

NEBRASKAland Days

June 18-25 NORTH PLATTE For Family Entertainment:RODEO Buffalo Bill Rodeo, Believed to be world's first and oldest rodeo started by Buffalo Bill Cody. Miss Buffalo Bill Rodeo Queen crowned.

PARADES! NEBRASKAland Parade. Floats, bands, marching units, outstanding riding groups, Antique and Classic Car Parade, plus the Best Dressed Western Kids Parade.

PAGEANT! Miss NEBRASKAland Pageant. See 1972's Miss NEBRASKAland crowned and scholarships awarded.

AWARDS! Buffalo Bill Award. Presented in person to a famous TV or movie star for "outstanding contributions to quality entertainment in the Cody tradition."

CARNIVAL! One of the largest carnivals in out-state NEBRASKAland

FRONTIER REVUE! Fun - Frolic - Songs - Dancing Girls - An era of the Old West comes to life!

OTHER EVENTS Art Shows - Square Dances - Shoot Outs. Tickets and information available from

NEBRASKAland Days, Inc. 100 E. 5th Ph. (308)"532-7939 p North Platte, Nebraska 69101

Speak up

(Continued from page 7)appreciate having them for our office collection. Also, permits for 1932, 1934, 1937, 1939, 1946, and 1947 which we have are in poor condition and we would like to replace them. Should readers have any of these in good condition which they might wish to contribute, they can do so by contacting Miss Elizabeth Huff, Chief, Special Publications Section, Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, 2200 North 33rd Street, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. -Editor.

In the February 1972 Speak Up column, a reader requested a recipe for either beef or venison summer sausage. Another subscriber responded, but did not sign his or her name. Here, then, is the recipe from a reader in Seward. —Editor.

SUMMER SAUSAGE RECIPE 2/3 beef or venison 1/3 pork shoulder Salt PepperGrind meat, mix together, and season. Then, take a patty of this meat and fry it —this way you can test the seasoning. Stuff seasoned meat tightly in casing and tie off at intervals to form sausages. Smoke for 10 to 1 5 days, depending on the heat inside the smoker.

MORE SAUSAGE- "I saw in the Speak Up column in February's NEBRASKAland that you are asking for a summer sausage recipe, so I am sending you one that I have used for years.

"We enjoy your magazine very much. When we have read it all, we send it to our son and family in Kansas '-Fred Bortz, Weeping Water.

SUMMER SAUSAGE 25 pounds beef 25 pounds pork 1 level teaspoon salt 1/2 teaspoon pepper 1 cup light brown sugar 1 teaspoon whole pepper 2 teaspoons saltpeter in a little warm waterGrind meat twice and add salt, pepper, and sugar. Add saltpeter to sausage. Stuff in beef casing about 18 inches long, then let stand in 10-gallon jar and pour on fairly strong salt water until sausages are covered. Let stand for seven days, then remove and retie each casing. Hang sausages for one day, then smoke to desired taste. If garlic flavor is desired, soak four cloves in a cup of hot water overnight and mix in with meat during initial steps.

FEELING AND LOVE-"The following poem and photograph are submitted with great feeling and a special love for the state of Nebraska.

"This poem is in no way a condemnation of the fine people in the eastern part of the state. I was prompted to write it after a recent visit to Omaha. A lifetime native of that city asked me where I was from and when I answered, his reply was, 'Chadron where?'" —N. Henry, Chadron.

THIS NEBRASKA I LOVE

This Nebraska I love. No, not "Go Big Red," nor Lincoln, nor Omaha, but this, the west of the state, the forgotten end of the state. I love the people of my small town, their faces tawny in summer from hours in the sun, rosy from winters cold. I love their conversations, "Tried a great new chicken feed. Sure hope it don't hail." And their innocence and astonishment as they openly stare at a daring lass in hot pants, but in low voices comment, "Them crazy shortshorts."

This Nebraska I love.

I love the highways, narrow and twisting through the ever-changing hills; the hills sometimes warm yellow, or cool green, or cold, brown, and barren. And the bluffs which suddently erupt but confine themselves to God's chosen area; beyond the bluffs, more and more hills.

This Nebraska I love.

I love the history. A place where I can stand and know that on this very site, in centuries past, walked the giants of creatures; a world so long ago and yet so present. I love the fort where a ghostly bugler still sounds taps from another time. At sundown, the proud silhouette of an ancient Indian, long gone, little remembered.

This Nebraska I love.

Yes, let "Big Red Go," and all the east of the state be content in pollution and confinement. May this, the west of the state, the forgotten end of the state, always remain so, for...

This Nebraska I iove.

Surplus Center

Mai! Order Customers Please Read

• We are happy to fill orders by mail. Please use the item number and title of item you desire. Weights are shown to help you determine shipping costs. Include enough money for postage. We immediately refund any excess remittance. Including money for shipping costs lets you avoid the extra expense of C.O.D. and other collection fees.

NOTE: Nebraska customers must include Sales Tax on total purchase price of items.

Saying "Trees" will bring a smile to your face. Even if you try not to smile. Seeing trees. Climbing in them (if you're a kid). Using them or just enjoying them, trees bring a lasting satisfaction. On this 100th anniversary of Arbor Day...the Conservationist's Holiday, bring joy to your little corner of the world. Plant a tree for tomorrow.

bring joy to your little corner of the world... Plant a tree for tomorrow!Ball of Trouble

Summer beach party almost transforms itself into tragedy as teenagers find themselves in deep water

Two of us could swim well, but the third in our trio sank beyond the shelf

DANGER WAS the farthest thing from our minds that fine spring day two years ago. We were just a typical bunch of frisky teenagers kicking up our heels at a class party planned to celebrate the end of our freshman year at Maywood High School.

About 20 of us were cavorting on the banks of Medicine Creek Reservoir north of Cambridge, trying to set up a picnic. But, when interest in that project waned, attention shifted toward the lake and a stretch of inviting and apparently shallow water nearby.

Although it was not an authorized swimming area, about a dozen of us waded into the shallows. Soon a redhot game of keep-away developed, pitting the boys against the girls. As the little white tennis ball zipped between us, no one ever imagined that disaster was stalking two of our number, waiting to mar our frolic. The game grew more boisterous, when suddenly the soggy ball zipped into untested water a bit farther from shore. That skittering ball set off a chain of events that led to near tragedy and would be a lesson to all of us for years to come.

Almost without thinking, we churned out after the ball. With just a few strokes, I passed two of the boys who seemed to have paused after going only a few yards. I remember wondering why they stopped. Apparently I was the only strong swimmer in the little group pursuing the ball, so I won the race.

As I made my way back to the game, I again approached the same two boys. One was clinging to the other, and he yelled "Help!" just once. But to me it

NAFW invites youth to join as Cover Agents. Enroll an acre of cover and help the landowner save that cover. There is no age limit. You are only as old as you feel. Anyone can enroll. Ask for your enrollment form and your copy of How You Can Add An Acre.

NAFW invites adults to serve as Volunteer Sponsors by actively recruiting Cover Agents in the local community. Ask for the NAFW Sponsor's application kit. Win your certification and be equipped with tools for the task.

Write to: ACRES FOR WILDLIFE Box 30370 Lincoln 68503

appeared as if they were just clowning around, so I continued toward them without changing my pace.

Within a few seconds, the truth of the situation dawned on me. Intense panic gripped one of the boys as he struggled in the water. As I swam within reach, he grabbed me and pulled me beneath the surface. Only then did I realize that the three of us were in very deep water, apparently beyond a shelf that dropped off sharply only a few yards from where we had been wading a few seconds before.

One of the fellows could swim well enough, but he was helpless with his buddy clinging desperately to him, for the second boy couldn't swim a stroke.

My reaction to the situation was almost automatic. There was not even time to consciously form a plan. After shaking off the first compulsive grasp, I began pushing them toward shore.

Although I'm fairly small—only about 5 feet, 2 inches-I am a strong swimmer. I can usually go a considerable distance without tiring. But propelling two flailing classmates through the water was quite another matter. When we finally passed over the edge of the shelf within the reach of a companion standing in shallow water, I was exhausted. By that time, I needed help myself to make it the rest of the way to shore.

Shakily, we clambered onto dry land. A serious accident had been averted, and the drama was over. It seemed eerie, but that little stretch of water looked just as innocent and inviting as it did when we first arrived. The gradual slope of the bottom near shore still disguised the dropoff and the deep water that had clutched at my friends and me just minutes earlier. But, that shelf is still there, a potential hazard to any swimmers or waders that might give in to the tempting waters on a warm day.

Now I understand the reason for clearly defined swimming areas, and the regulations that prohibit swimming anywhere else in large reservoirs. Good swimmers, as well as non-swimmers, can be taken by surpirse by underwater hazards in unfamiliar waters, especially when involved in what would normally seem to be a harmless game like tag or keep-away. Approved swimming areas are free of these dangers.

Swimming is still one of my favorite pastimes, but that experience at Medicine Creek Reservoir two years ago has made me realize what hazards to avoid. THE END

The "Executive" Funmobile: You can travel anywhere in an easy-driving "Executive"... the truly magnificent motorhome. It's your portable apartment for a lifetime of carefree living. Contact us for a demonstration appointment or for more information. We'll show you the difference that quality makes.

Exclusive dealer for this 3-state area EXECUTIVES' CAREFREE VACATIONS, LTD. 427 S. 13th St. Lincoln, Nebr. 68508 (402) 432-0203

DISCOVER MORE with the all new COMPASS TREASURE FINDERS!

"YUKON" SERIES T-R INDUCTION BALANCE DESIGN DOESN'T MISS WITH OUR REVOLUTIONARY WIDE-SCAN SEARCH LOOP! COVERS 300% MORE AREA IN A SINGLE SWEEP THAN ALL CMPETITIVE T-R INSTRUMENTS AND WITH PRECISE "OBJECT" PIN-POINTING CAPABILITY. IMPROVED DESIGN FEATURES Advanced solid-state circuitry with superior sensitivity, waterproofed search loops, exclusive ground condition adjustments plus our meter-zero control makes COMPAS the most dependably accurate detector available! SEND TODAY FOR FREE BROCHURE DESCRIBING COMPLETE LINE OF 12 LB AND BFO MODELS! YUKON 94-LB $124.50 8" loop (waterproofed) built-in speaker headset input telescoping shaft volume control YUKON 71-LB $189.50 8" loop (waterproofed) indicated meter metered batter check built-in speaking telecoping shaft padded headphones volume control YUKON 77 LB THE DETECTOR DESIGNED FOR THE PROFESSIONAL! $249.50 8" loop (waterproofed) 12" loop (waterpoofed) ground condition adjust indicated meter padded headphones metered battery check built-in speaker volume control telescoping shaft meter zero adjust (allows a pegged needle to be returned on scale) ORDER YOURS TODAY...OR... write for free colorful brochure on the complete lin of COMPASS TREASURE FINDERS when ordering, please include sale tax SOLD REGIONALLY BY: LIGON SCRAMBLERS SALES 6500 No. 7th, Route 5, Lincoln, Nebraska 68531 Phone (402) 432-2336How to: Boat in Rough Weather

If a storm is imminent, stay at home. But if you should be caught out, follow these rules WINDHead craft into wind, keeping the bow angled into the waves

If boats should capsize, hang on; stay with it for buoyancy

Should motor fail, rig a pair of pants to make a sea anchors

Approach dock from leeward side to avoid nasty crash

During daylight, warning is a red, triangular pennant

After dark, warning is red light displayed over white

A GREAT DEAL has been written about what to do in stormy weather when on the water, ' but by far the best advice is to stay home. If there are any misgivings lurking in your mind, listen to them and don't go near the water. Your new boat may be tempting, the sun may be shining brightly, and the water may be smooth and blue, but if you have reason to believe that there will be troubled waters in the not-too-distant future, drop anchor in a quiet, sheltered cove and prepare to ride out whatever nature sends your way.

There are several ways of obtaining information about weather conditions, some of them reliable, others less valid. The most dependable source of such information is the local National Weather Service. Contact with this bureau before a voyage, no matter how short, may spare the sailer a great deal of grief.

Listening carefully to the weatherman on radio or television can also be of great benefit. If rough weather is on the way, then follow the same advice — stay home and don't go near the water. Storm-warning signals are given in case of approaching foul weather at weather stations, Coast Guard stations, yacht clubs, ports, and large marinas. Flags are used during the day and lights at night. If any of these weather signals are displayed, stay home —and stay off the water.

Whatever the weather for your voyage, be sure to take certain precautionary steps before departure: 1. Be sure your boat is fully equipped and in seaworthy condition; 2. Be sure you have plenty of fuel; 3. Don't overload your vessel; 4. Notify a responsible person of your estimated time of return and the area in which you will be cruising so that if you don't return on time he dispatch a search and rescue team.

There are, too, some natural indications which an observant old salt may generally rely upon. Some useful tips are: 1. Bright blue sky —fair weather; 2. Red sky at sunset —fair tomorrow; 3. Red sky at sunrise —foul today; 4. Grey sky at sunset —foul tomorrow; 5. Cloudless sunset —fair tomorrow; 6. Ring around moon —storm coming; 7. Weak sun —possible rain; 8. Diffused, glaring sun at sunset —storm coming; 9. High clouds going in direction opposite to that of low clouds — unsettled weather; 10. Fleecy, light clouds —fine weather; 11. Small, dark clouds —rain; 12. Large, dark cloudsstorm; 13. Streaks and patches of white clouds on horizon after nice weather-change of weather with wind or rain; 14. Wind before rain —mild storm; 15. Rain before wind —rough storm; 16. Rising barometer —fair; 17. Falling barometer — storm.

If, however, you are caught on water during a severe blow, there are several steps you should take, depending on the circumstances. First of all, if possible, head rapidly to shore. Beach your boat and head for shelter.

If the storm is electrical, take cover in a draw or low spot and lie flat. Another safe place is in the center of a group of trees, but avoid isolated trees, posts, or walls, since lightning has a tendency to strike the highest spots.

If the storm builds up to a tornado, head away from it at right angles and, again, seek the lowest spot available, ideal shelter being a road culvert.

If you can't make it to shore, then head your vessel into the wind angling into the waves. Have all persons either lie down or sit on the bottom of the boat. If your motor fails or if you have no motor, use a sea anchor which may be a bucket, a shirt, or a pair of pants knotted at the ankles. This sea anchor should be tied to a line over the bow of the craft so that it drags in the water, keeping the boat facing the wind.

All boaters should remember that state law requires all youngsters under 12 wear life preservers at all times. It's also not a bad idea for adults.

If your boat capsizes or swamps, stay with it, since most boats float. It may be a lot farther to shore than you think. If you have a radio, signal Mayday. If you have a sound-producing device or a light, flash either the emergency distress signal, which is four or more short blasts or the same with lights, or the internationally known distress signal SOS consisting of three short, three long, and three short blasts or flashes of lights.

Remember, as the saying goes, there are many bold sailors and many old sailors, but only very few bold, old sailors. THE END

NEBRASKA-NUMBER ONE

by Francine Skorka, Omaha. This poem, excerpts of which appear here, was judged winner of the 1971 Mari Sandoz Essay Contest sponsored annually by NEBRASKAland Magazine. The 1972 contest, open to all 7th through 12th graders in Nebraska schools, is presently underway. Rules are available at schools or by writing NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebr. 68503. Deadline for entries is May 12.

It's New Year's Day, nineteen seventy-one, Ask a crowd "What's the noise about?" "Nebraska's Number one!" they cheer. Do you mean they've just found out? I've known Nebraska was number one for a very long, long time And I'll give you just a few reasons why In the following little rhyme. Centuries and centuries and centuries ago, On what is now Nebraska, would roam Ancestors of elephants called woolly mammoths The first to call Nebraska their home. The Otos looked upon it as paradise Filled with crops of platinum corn. They called it Nebrathka ("flat river" it means) And that's how our state's name was born. Since this land is located on the Central Plains, The Indians would constantly go To Nebraska, for hides and meat because It was a center for buffalo. One thing was missing in Nebraskaland, It seemed forgotten by its Maker. "Trees!" J. Sterling Morton cried. They now cover two million acres. In the year, nineteen hundred thirty-three Power and irrigation districts were permitted That is when the name "The Nation's only Public Power State" was fitted. We are the "Beef Capital of the World" Does Nebraska proudly proclaim. Being the world's greatest livestock market, Is the city Omaha's great fame. "Equality before the law" our motto states And that we believe is true. We carry this motto in our hearts And in all we say and do. There are dozens of lists of people Who many great deeds have done Which really shows that her people Make good 'ole Nebraska number one. So now when you" hear those great screaming mobs, Shouting "Nebraska is number one!" Take some time to think it's not just a game, But a whole "way of life" we've won!Crappie Cradle

Milton Ross, left, and Irvin Schmidt find crappie in beds, but not asleep

STAY IN YOUR bed and catch fish? It sounded like fantasizing by a lazy fisherman, but this was actually Irvin (Smitty) Schmidt's advice on how to creel Midway Lake's crappie.

Two days on the lake with Smitty and his fishing partner Milton (Ross) Ross, convinced me that "bed" fishing leisurely and productive, but definitely not for the lazy. The fruits of hard work lay, literally, beneath the surface, and we were reaping the rewards of past efforts.

Despite the weatherman's prediction that the skies

would clear, a cold, mid-May rain was still falling when I

arrived at Smitty's home in Cozad. He informed me that

Ross wouldn't be able to get away until the next morning,

but suggested we give it a try later in the afternoon if the

rain let up. By five o'clock we had convinced ourselves

that the weather was improving, so we loaded our fishing

gear in the car and headed south on Highway 21. Four

miles south of town we turned west on a county road.

Several consecutive days of rain had turned it into a quagmire,

and for several miles we slipped and slid along, trying to stay in the ruts. Finally, turning south again, we

climbed the bluffs and headed toward the lake.

arrived at Smitty's home in Cozad. He informed me that

Ross wouldn't be able to get away until the next morning,

but suggested we give it a try later in the afternoon if the

rain let up. By five o'clock we had convinced ourselves

that the weather was improving, so we loaded our fishing

gear in the car and headed south on Highway 21. Four

miles south of town we turned west on a county road.

Several consecutive days of rain had turned it into a quagmire,

and for several miles we slipped and slid along, trying to stay in the ruts. Finally, turning south again, we

climbed the bluffs and headed toward the lake.

Donning rain gear, we backed Smitty's 16-foot craft from the boathouse at Midway Resort and headed slowly out onto the lake, taking a random, zigzag course.

"The lake used to be deep here," Smitty pointed, "but it has silted in badly and now you have to be careful to stay in the channel. I marked the channel several weeks ago, so we shouldn't have any trouble."

As we entered deep water, Smitty opened the throttle and the boat leaped forward. A light rain was still falling, and the boat's speed turned the drops into tiny bullets that stung our faces. After five minutes of this pelleting we turned into a cove and idled slowly toward the bank.

"We'll try a few of these areas close to home and save the rest for morning," Smitty said, as he pulled out his spinning rod.

I watched slyly as he rigged up —a No. 4 hook baited with a 2-inch minnow, a pair of split-shot weights, and a bobber set for a depth of just under 3 feet. He advised me that the beds extended three feet down from the surface and that fishing any deeper almost always results in snagging. Following Smitty's lead, I set up my outfit and cast to a spot about 10 yards from the boat's stern where he said there was a good bed. Meanwhile, Smitty had rigged up a second rod with a heavy sinker and larger minnow, and had cast it into deep water at the mouth of the cove.

"I always fish my second line on the bottom," he explained, "and sometimes I come up with a good catfish or walleye."

With clear skies second day, Carina Pettersson, Swedish exchange student, joins fishing session

Planning, work in winter yield crappie in spring

Continued fishing success reflects value of habitat-management plan

Raindrops were still marking the surface of the lake when I saw my bobber dip quickly several times in succession. Instinctively, I set the hook but succeeded only in sending my bobber, weight, and hook flying into the air.

"Let them work on it a little longer," Smitty suggested. "A crappie will usually bump the minnow several times before inhaling it. Wait until the bobber goes completely under and then set the hook quickly but gently. Crappie have tender mouths and if you set the hook too hard you'll rip it out."

Minutes later, Smitty demonstrated his advice. His bobber dipped cautiously several times and then lay still. Waiting patiently, Smitty watched the float. Seconds later it dipped again several times in succession and began moving slowly away from the boat. Playing out line, he continued to wait. Finally, the bobber disappeared completely and Smitty lifted his rod tip smoothly, hooking the fish. The light rod bowed sharply as the crappie bored for deeper water. Smitty, obviously enjoying the fight, let the fish wear itself out, then led it to the boat and lifted itaboard.

"They put up a good fight for their size," Smitty said, unhooking the nine-incher and dropping it into the fish basket hanging over the side of the boat.

My attention had been diverted by the action, and when I looked up my bobber was gone. Lifting the rod tip carefully I felt the hook drive home and the fish dive. In a minute I was lifting the scrapper aboard.

"Looks like a twin to the one I just caught," Smitty observed, as I unhooked the fish and dropped it into the basket.

For the next hour, the crappie bit well. The action wasn't furious, but it was fast enough to keep it interesting. Most of the fish measured from 6 to 10 inches. Smitty, however, landed one — more than a foot long — which topped the pound mark.

By 7:30 p.m. the muddy sky was turning dark as the hidden sun sank lower. A few drops of rain still splattered down, but it was obvious that the brunt of the strom had passed.

"Let's give it about 15 minutes more and then head in," Smitty suggested. "We've (Continued on page 64)

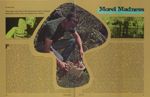

Morel Madness

When May rolls around and mushrooms begin emerging, Nebraska's fields, glens are flooded with huntersLew Hamner's grand discovery is bragging stock

PICKUPS LINED THE river roads and hunters swarmed the fields. It was late in the season and competition had grown keen. Morning dew swept across the grassy river bottoms in twisting trails. The first hunter to that special area would be the one to return with his bag filled. But what was this madness? The woods had just greened and it was only May.

With orders to seek out and discover what all the excitement was about, NEBRASKAland photographer Bob Grier and I were dispatched to the Columbus area to search out the elusive morel mushroom. Bob, a greenhorn as far as mushroom hunting goes, and I were both determined to sample the gustatorial pleasures of this delectable wild fungus. I had reached that awkward stage in a mushroom hunter's life, when he knows what the spongy little devils look like and starts to formalize his own theories on when, where, and how fo find them.

Light of heart and short on mushrooms, we set out to tail the mushroom purists, the veterans in the field.

An earlier conversation by phone with Max Wunderlich, Jr., of Columbus, was somewhat less than encouraging. The tail end of the season was at hand but he volunteered to serve as host for our expedition. It being mid-week, Max could not get away from work until five, so we agreed to meet in Columbus then. That would still give us threeor four hours of daylight, hopefully enough time to do some good.

We were approaching the Columbus area by mid-morning. That left almost half a day to kill before our meeting with Max and his crew. A self-guided expedition was soon launched and we headed for the Loup River south of Monroe. The Platte River was an ominous sign of impending failure, since muddy water boiled from bank to bank, and in spots spilled over onto the surrounding flatlands. Those flatlands were our mushroom grounds-the situation was not at all encouraging. "Won't have to wash them off that way," Bob quipped.

An eastern extension of Sand Hills country glided by us as we traveled through undulating pastureland between the Loup and Platte rivers. Timbered suggestions of the Loup rose ahead of us. A pickup off on the side of the road hinted that we had reached our destination-mushroom country.

Parking opposite the pickup, we plunged into the green mass of cottonwoods and rank, herbacious undergrowth. Trampled grass and trails through the weeds told of many feet and eager hands that had probed the ground in quest of the fleshy fungi. Three days had elapsed since the weekend rush, and new, pear-shaped delicacies had forced the moist earth aside.

My minesweeping technique was interrupted as Bob plucked the first prize of the day. "Is this what we're after?"

"That's our baby," I confirmed, moving closer to his area.

For Keith Bruhn, Monroe, the best way to locate mushrooms involves liberal dose of luck

Max Wunderlich, jr., Mel Kampschnieder, both of Columbus, navigate water barrier. Paul, Max's son, rides high, dry on father's shoulders

A dozen more were added to our bag before we decided to head for town, grab a sandwich, and hunt the same territory that afternoon.

Mushroom hunters must think on similar wavelengths. The fellow with the pickup across the road was just coming out of the timber with a sack full of mushrooms when we reached the road. "Didn't do too badly for just being out an hour or so," Harley Bruhn responded to our query. "First time I hunted over on that side of the road."

"You've got enough there for several good messes," I guessed, after looking into the wrinkled paper sack. Most were two-inchers, nice and fresh. He culled a few of the old, dried ones while we talked.

"If you fellows want someone to go out with this afternoon, try checking at the gas station. They were talking about going out at noon to pick a few. I'm going there now to fill up.

You can follow me if you want," Harley offered.

Thoughts of a noon break and chow were dispelled at a moment's notice with that statement, and we headed for town.

Gas stations are a bit like the old general stores. Hunters, fishermen, and sportsmen at large gather to rehash old times, plan new ones, and check on their cohorts' success. An attentive ear often pays big dividends for the tinhorn.

"We got about a peck of mushrooms down in one pasture south of the river last Sunday. There was a scad of little devils around all the fallen cottonwoods. They should be ready by now," Keith Bruhn thought aloud, as several locals came out to check the results of Harley's efforts.

A hint of opening-day deer season — small-town style —lingered strong in the air. Hunters come and go regularly and a group is usually on hand at any given time to peer into the pickups, checking on the other fellow's fortunes. The game may have changed, but the rituals were the same.

"I was figuring on going out for a while during my lunch hour," Keith led with an inviting tone. "You guys are welcome to come along if you want. There will be plenty of mushrooms if all those little ones are any size by now." A second invitation was unneeded. Bob and I loaded into Keith's "bush" car and were being taken to his mushroom grounds a minute later. A glance into the back seat confirmed that we were dealing with an optimist of the highest order. Three large, plastic buckets and one plastic basket, washtub-size, were stored in the back seat. Expectations for the noon hunt looked bright.

Mushroom grounds are something like favorite fishing holes or reliable brush piles that foster a covey of quail — they are to be guarded with the deepest confidence. Keith's mushroom ground was no exception, though he did forego the formality of blindfolding Bob and me as we wound through the greening pastures to the river's wooded edge.

"They cut some large cottonwoods here a year or two ago hoping to encourage a denser grass stand for pasturing cattle. Most trees were left to rot where they fell. That makes for prime mushroom country," Keith explained as the car ground to a halt at the edge of a passive slough.

Moist, warm weather and decaying humus are prerequisites for the mushroom fruits to force their way to the surface. The week preceding was spotted with gentle showers. Humid, warm weather had followed. The area was covered with a deep accumulation of leaf litter and newly fallen cottonwoods. The weather had been ideal and the location looked perfect. Everything promised mushrooms, even though it was late in the season.

"Doesn't that beat all!' Keith said, looking over a bed of mushroom (Continued on page 55)

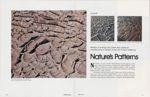

Nature's Patterns

Like curled shavings from a carpenter's plane, crusted mud shows nature's design

In whimsy of remorse the designer heals her scars

Warming sun draws moisture from polished earth

NATURE is a clever woman who fashions myriad patterns as she goes about her business of tending the great outdoors. Some patterns stand out in bold challenge against a stark, cloudless sky, while others melt shyly and unobtrusively into the camouflaging blotter of forest, field, and hill.

Finally exposed in death, the roots appear in gnarled, confused mass

Water and broken roots form fearsome masks to stare back from the shallows

Ultimately designed to supplant their protectors, small hints of life emerge

A single leaf, stripped of its covering, leaves a naked skeleton that gives it form

Blazing stranger is engulfed in whirlpool of bisqu it-colored leaves

Crimson-lined pod, spiral snail shell complement each other

The cottonwoods scattered along a shoreline sit in stoic acceptance of their immobility, their wrinkled legs and arthritic knees incapable of extracting their feet from the binding soil. Farther away, serving outpost duty for a field, another stands in battle against lightning bolt and pummeling gale, its spidery outline always crouched against renewed attack. Despite its rough, no-nonsense character, the tree is ornamented with a useless loop, a toy through which squirrels or mice may dart and play.

Woody fragments retreat to earth in stony dignity

Swelling, brawling streams display brilliant patterns

The gnarled limbs of distant oaks release biscuit-colored leaves that swirl together in a brazen whirlpool wjth a flaming ivy leaf at its vortex. A seed pod husk, crimson lined, falls wearily beside a spiral snail shell, where for a time they lie together, each accenting the other's beauty. In a matter of days, all these will crumble and sink into the anonymity of dark humus.

Drained of their strength, streams are embraced by crystal caskets of winter

The designer's signature is of earthly form, its creations of delicate beauty

Each new spring calls for sharp acceleration. Swamp grasses spear green exclamation points from the warming earth, the swelling, brawling stream displaying brilliant foam patterns. Greening earth builds swiftly, and in secret places, rich verdure frames velvet shadow boxes in secret places that hold dewy rhinestones suspended from cobweb strands.

Again the rain mixes with the earth. Nature's patterns build, destruct, and build again according to the expansions and contractions of the cosmic forces that measure the heartbeats of eternity. The only changeless thing is change itself. THE END

Like rhinestones, the dewy drops of morning cling to thread-thin strands

They're at the Post

Each year, a pulse-pounding action reigns supreme as the sport of kings takes throne

THE SNOW IS hardly off the fields when Nebraska starts to buzz. Names like those of the late M. H. Berg, all-time dean of horse racing in the state; Rose's Gem, said to be the greatest racehorse ever to come out of Nebraska; and Fonner Park, the track that starts it all each year, replace everyday language all across the state. And, a host of hard-core racing fans settle down with last season's racing programs to chart this year's path to success at the track. Some call such goings-on symptoms of spring fever, but there are those who know that it goes much deeper than that. They are members of the cult whose racing interests never die, simply lying dormant throughout the winter to be reborn in spring.

Horse racing in Nebraska has long since lost the stigma of gray, pin-striped, double-breasteds and broad-brimmed fedoras. It is good, clean family fun —a close relative to football in the crowds it draws each year. In fact, 1971 saw more than a million in estimated attendance pass through the turnstiles at Nebraska's six tracks. And, native horses are again expected to dominate Nebraska turf in all-or-nothing runs for the money. That in itself would seem enough to generate fever-pitch excitement among those who frequent the state's racing plants, but the $2 bets are the ones that really bring on the screams and shouts. Maybe, though, the simple fact that man is a competitive animal is the clinching factor. After all, the whole thing started long before modern currency was born, and the history of horse racing fits into the development of Nebraska's pulse-pounding sport.

Omaha's Ak-Sar-Ben draws honors as state's biggest racing plant

Glass-enclosed grandstand at Fonner Park allows early runs

Fans flock to Lincoln's State Fair Grounds for third opening

In the puritanical view of several of the American Colonies, pitting two horses against each other was sin personified. Others, however, adhered to the royal scheme of things, and horse racing was among the traditions they were reluctant to relinquish. So, the sport of kings essentially became the sport of everyone and racing had a foothold in the Americas. As time passed, the sport spread westward onto the wild plains of the West with a new twist on ancient competition. Probably the first horse race in Nebraska was between two weathered cowpokes and their wilder-than-tame mustangs. Stakes ranged from a month's wages to a slug of redeye, but the premise was the same: "My horse can beat yours". Time has a way of changing things, though, and the thinking along racing lines took a more organized course. It is that course that brought Nebraska to the stature it enjoys among racing buffs of today, and in its development was born one of the most unique success stories in the annals of the state.

To control and regulate the sport in Nebraska, a three-man commission was established within state government. Each member is appointed by the governor for a three-year term during which the prime responsibility is running the tracks of Nebraska. The phenomenal thing about the Nebraska State Racing Commission, though, is the revenue the agency generates. The smallest of state organizations in manpower, the commission is the largest moneymaking group in that structure. Last season, the Nebraska State Racing Commission poured more than $2 1/2 million into the state coffers. That's not bad when it is considered that the whole affair is governed by such a small group and the money-making season was only 171 days long last year. Obviously, there are ways such feats can be accomplished, and the racing structure of Nebraska is just one of them.

First of all, no private individual can own a horse-racing track. Each must be established by a non-profit, civic organization and revenue is channeled into community benefits and upkeep for the track. The first $1 million to cross the betting boards is tax-exempt, so this money can be used for both city and plant betterment. Thereafter, however, 4 percent of every dollar is scraped off the top as a mutuelhandle tax which goes into the state's general fund. At the end of the year, commission income, after expenses, is divided equally 93 ways and distributed among Nebraska's counties without regard to population or size. There are no strings attached, except that, once again, the revenue must be spent for qualified county fairs or 4-H shows. At the end of the last racing season, the racing commission had $177,978.75. Divided by 93, that meant each county, whether a track was located within its boundaries or not, received $1,913.75, seemingly out of the blue. So, while the areas that boast tracks would seem, on the surface, to be in fat city as far as revenue is concerned, it just isn't so. Everyone gets a fair share, and the racing fans who bet are the ones who control the amounts.

There are probably only a handful of bettors in the state who know they are wagering in a rather unique way. Most fans know it is called pari-mutuel, but they would be hard pressed to explain the process, though it is one reason for the success of horse racing and the tracks in Nebraska. Since no one individual owns the facilities, pari-mutuel betting is ideal. In essence, the track is only an agent for the money that passes through the betting (Continued on page 55)

Municipal money rides along as ponies explode from gate

Some say that they can pick a winner just by watching

Last year, Columbus handled more than $4 million in bets

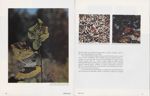

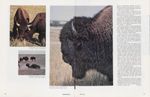

No Place to go

ONCE FREE to roam across the plains, the American bison is today a humbled creature. Confined by fences, he contents himself with an existence only vaguely and wistfully reminiscent of days long gone. With head slung low from massive shoulders, he stoops like a statue commemorating the wanton slaughter of his species, yet appearing to be ready to charge at a moment's notice in anger of defeat.

But why should he charge? He has no place to go. Once he was part of a handsome herd that grated the grasslands of the West, or loped wifn a rolling motion along the horizon —part of a North American population estimated at 60 million just a century ago. Today, however, his numbers are down to 20,000, primarily in captivity.

Humpless and helpless at birth, the young bison seeks maternal protection

Youngsters retain light pelages through their first summer season

Youthful calf's exuberance requires a seemingly constant replenishment

The bison's posture was always the same — his shoulders were always huge and his head was always below them. But his stance is strangely symbolic of his tragic history. Never, on the face of the earth, was there such a collection of large animals belonging to the same species as on the North American continent, and never was there so much wholesale massacre.

As white men moved in, they brought the bison to his knees. Although his range had stretched from coast to coast, the bison was forced beyond the Mississippi River by 1820. And, when the railroad fingered out across the West toward the Pacific Ocean, it brought white men who cared not a hoot about the bison's future.

Supportive nutrients that enrich grasslands attract bison to licks

Mock battles of calves are prelude to future, serious confrontations

Wallowing in dust rids the beasts of insects, forms future potholes

Surviving a century of persecution, the bison's future now seems secure

The "great slaughter" continued for more than a decade so that by 1889 it was estimated there were less than a thousand bison left alive on the entire continent.

In 1902, Congress earmarked $15,000 for the protection of a bison herd in Yellowstone National Park, and then set aside other sums for herds to be established in wildlife refuges elsewhere in the West. One of them found sanctuary in the federal government's wildlife refuge at Valentine.

The trend caught on. State governments, too, began taking notice and established their own wildlife refuges. As a result, a second bison herd was established by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission during the 1930's in Nebraska's Wildcat Hills.

While the bison is also called buffalo in North America, the name is zoologically incorrect. The bison — Bison bison — should not be confused with the European wisent — Bison bonasus — or the distantly related buffalo species. All, however, are members of the Bovidae family.

Vicious when vexed, yet capable of domestication, bison cannot be trusted. Sportsmen know they can walk to within 100 yards of a herd without spooking it. More often, though, the herd will gallop away in a stampede at speeds up to 40 miles per hour upon seeing an adversary as far as half a mile away.

Bulls are larger than cows, their horns spreading wider —sometimes to three feet — and their weight much greater. They are also more vicious. Cows are relatively calm, aggressive only when chaperoning a newly born calf, and even then charging a foe only when provoked. Bulls, on the other hand, may charge at a moment's notice for no apparent reason, and the foe might be a youngster from the same family who shows a bit too much competitive spunk.

A calf is born with almost no hump. He scampers about through the grasses, running to his mother when danger approaches or when he is hungry. Only when he grows older does his hump become larger, thus telling year by year and with increasingly obvious symbolism, the tragic story of his species.

Once he was free to move from range to range across the prairie's expanses, but today the bison is penned inside small sanctuaries. Although he is free from wanton waste, it is only because he is now protected by man — his killer a century ago. THE END

Hens in a pen

Although far from new, the concept of breeding game-farm birds to wild ones may someday prove workable to boost state's ringneck crop

Marking each nest with a flag makes spotting easier

A six foot fence is the first step in project that will run for months

Researchers use both wing, leg tags to identify project birds

THE HEADLIGHTS of the pickup swept across the dew-laden alfalfa, paused briefly on the mulberry tree ahead, and faded. In the west was darkness, but from the east came a faint glimmer of light along the horizon. Time: 5:09 a.m. Temperature: 47 degrees Wind: 5 miles per hour. Skies: clear. Slowly, the sky began to brighten, colored by hues of pink and gold, as the sun inched its way above the horizon. A slight breeze stirred Suddenly, the two-syllable crowing of a cock pheasant echoed across the field. A hurried grab for the spotting scope and some fast focusing soon brought the gaudy, ring necked pheasant into view. Encounters such as this were to become quite routine during the next few months.

Farm hens are used since they will tolerate higher per-acre densities

Bill Baxter, left, and Carl Wolfe take data from a deserted nest during study

The initial proposal called for tracts of one to five acres of acceptable nesting cover inside predator-proof fencing to be stocked with wing-clipped, game-farm hens. Breeding or insemination of the hens was to be dependent on the resident population of wild males. This "wild breeding" concept (use of wild cocks with game-farm hens) was not new. The method was first adopted in 1932 by B. K. Leach, a private game breeder, who perfected and used this system for wild turkey in Missouri. The wild breeding system with pheasants had not been tried, though, until now.

In certain areas of the state, such as the central Platte River Valley, the problem of deficient nesting cover is compounded by intensive agricultural operations which doom not only the nesting attempts but often the hens as well. Confining production to small, protected acreages would reduce these losses and partially compensate for the lack of nesting cover. Game-farm hens were used in the experiment because of their ability to nest under high-density conditions. Previous studies had shown that wild hens seldom nest successfully in high-density situations.

Field work began in the fall of 1970 with selection of the Cornhusker Game Management Area near Grand Island as the study area. Cornhusker included 815 acres with the majority of them managed for wildlife.

Because of abundant cover, choosing pen sites was not difficult. Six plots, each an acre in area, were selected with three plots in the northern half of the area and three in the southern half. Each pen was divided in half to facilitate statistical analysis. Fence trenches 8 to 12 inches deep were dug around each pen that fall.

During the ensuing winter months, conferences were held, materials were contracted, and plans for project implementation were studied. By late February, field work resumed. Between snowstorms, an effort was made to count the cocks in the study area—10 to 15 were sighted.

Adverse weather delayed pen construction until late March. Then two-inch mesh wire six feet high, and buried in trenches to discourage (Continued on page 54)

the cedars are coming

Unbroken expanses suddenly come alive with juniper armyLIKE EMERALD SOLDIERS their columns marched the ravines, ragged ranks conquering naked expanses —a battle locked in time. Trees braced against the emptiness, against the elements, and against the hostile plains suited only for grasses green, their needled legions amassed for the assault.

The first of many to follow, the parent tree clung stubbornly to a mere foothold on some neglected corner. Stoically it bore the attacks of its adversaries, its body ripped by menacing livestock, stunted by toxic sprays, and mutilated by cutting steel. Its badgesof courage were many.

The attack was imminent. Strategy was drawn from countless conflicts. Silently, the charge began.

Hardly an imposing force at first, the potential giants, guised as seeds, swarmed the battlefield, brought by way of earthly elements, fowl of air, and creatures of land. Unnoticed, they assumed their stations, awaiting individual tests. Years passed, and still they held their lines.

Come spring, cedar becomes a remote recess for robin and her tiny brood

Cedar waxwing seeks cedars' safety and abundant fruit during winters

Freckling hillside, pastures, these junipers contrast grassland expanse

knee-size cedars converged and conquered.

Not to be routed, the land is now theirs!

knee-size cedars converged and conquered.

Not to be routed, the land is now theirs!A conifer by heritage, juniper by title, the cedars have come to stay. Freckling hillside pastures, filling river-bottom voids beside fallen elms, and clinging tenaciously to rocky canyon walls they stand. Garbed in irregular uniforms, they are prostrate creepers veiling rolling hills, or twisted mutants of infinite variation, or massive giants of river forests.

Lineage mixes and mingles in the Midwest. Hybrids emerge from crossings of the Eastern red cedar and the Rocky Mountain juniper of the West, muddling any attempt at lucid classification.

Ornamental junipers adorning homes, commercial varieties like Blue Heaven, Chandler, or Pathfinder little resemble the Rocky Mountain juniper from which they originated. Nor do the striking Canaerti, Dundee, or Glauca resemble the Eastern red cedar.

Dioecious, as botanists say, the sexes are born on separate plants. Bronze redness of the males and the bluish tinge of the females suggest the gender at a distance. Fruit-like berries, each containing several nut-like seeds, unmistakably brand the female. A blue, waxy coating on the berries retards water loss, protecting the fruits similar to the function of wax on plums and grapes.

The knotty red wood, locked tightly within the cambium layer, is prized for its aromatic quality. Hewn by craftsmen, it is used for those traditional high-school-sweetheart hope chests.

Mushy brown globes adorn the cedar during the dampness of spring. Not the poison spheres imagined by youths, but growths of cedar fungus, they alternate their parasitic cycle between the junipers and apple trees.

Regarded by many landowners as pasture pests, cedars are mere reflections of poor land management. Overgrazing of desirable grasses and forbs by livestock, and avoidance of the unpalatable cedars accentuates their spread. Man's suppression of periodic rangeland fires, that had maintained Nebraska's grassland biome by burning away young tree seedlings, promotes the cedars' spread.

Gnarled and twisted by winter wind, an ancient cedar frames its progeny

Many early homesteaders build their cabins near protective cedar stands

They have come. They have conquered. They claimed the land and it is theirs

dime-a-dozen gun

A time must come for every boy, if he is to hunt, when he learns that his sport means much more than simple killing

THINGS WERE DIFFERENT that day. I had wound through that tall brome behind Morris' battered old house ever since the first time I snuck away to the spring. Old Morris never cut that patch of grass — just let the pheasants and field mice have it. He was kind of a singular old cuss, and nobody ever did figure out why he never planted it to corn like the fields all around it. Just liked to see the pheasants fly in at night, I reckon.

The little spring always popped out sudden-like. All those old, twisted willows gave it away, but nobody ever took time to really look for it. I used to wade there when I was just a boy, crunching empty snail shells between my toes.

But it was different this time. I was hunting on my own. Guess that made me almost a grown man. I had been out with older folks before, but this day was different. They had finally let me go off on my own.

The spring had water clean enough to drink. It was quite an adventure, lying down on your belly and drawing in the fresh, cold water on a hot summer day —just like old trappers must have done.

My new gun was slick and smooth, the steel cold, not a scratch or mark anywhere. It hadn't come easy either. It took a lot of digging for fishing worms in the mushy old swamp. Twenty-four fifty didn't come fast at a dime a dozen. Didn't make enough selling them that summer to buy my gun for the hunting season—just kept ogling it in the hardware store until after Christmas. I knew exactly where that $5 bill was going when I got it under the tree. Guess someone else did, too.

It was the prettiest gun a boy ever had, specially if he was only 11 years old. Felt real good in the hand, and deep down inside, too.

It was a right nice day for January, with the sun out warm and the breeze not too stiff. Dabbles of snow hid in the north shadows, but mostly it was just a brown-grass day.

The covey of quail wasn't under the plum thicket like it should have been. Can still remember earlier thatfall when we busted into them. I used that heavy old gun Dad borrowed for me. It didn't feel good at all like mine did now. We walked right into the whole shebang! Came up so tight and all fluffed out it seemed like the whole bunch should have fallen when I shot.

Wasn't seven a feather floating, though, when it was all over. Guess that's when I learned you can't kill them all at once. You have to pick one.

I figured there might be a rabbit down in the tall weeds where the spring ran into the creek. We found that nest of young ones there under the clay bank one year. Didn't even have their eyes open yet. Thought a rabbit might move into the open if I sat there on the hill long enough.

The frost worked right out of the clay through a fellow's pants back then. Didn't seem cold at all until you sat down. Remember thinking that some day I would own a pair of those waterproof pants like city hunters had. Remember thinking, too, that Dad would probably laugh at me —call me a dude.

I didn't want to go home without something to show for the day, had to prove something to myself I guess. Even a rabbit or squirrel would do.

Sure was cold there all alone. Hungry, too. Was wishing I had brought those cookies Mom had wanted me to take. She sure did fuss over everything before I left.

Unload your gun when crossing a fence. Don't go too far. Come home early. Be careful.

Gee whiz. I was old enough to know all that. You'd have thought I was just a boy.

A pair of gaudy blue jays made quite a ruckus in a cedar, but little else was about. They would have been an easy mark just sitting there plucking away at the waxy berries. Remembered, though, when Dad took my air gun away once for shooting them.

We don't shoot anything we can't eat.

Guess that little fuzz-tailed bunny didn't know that he was about the biggest thing that would ever happen to me when he sniffed his way out from behind that soggy old log. To a fellow out on his first hunt all alone, he looked about as big and important as that buck deer Dad had brought home once. Now that I look back after shooting a whole scad of rabbits and other bigger critters, he wasn't much, stature-wise that is. Probably didn't even mingle socially with the other bunnies, him having that droopy, frost-bitten ear and a dull coat and all.

Of course, I wasn't noticing those things then—just how much I wanted to take him home in my game pocket and how darn stubborn that new safety was.

It seemed as if I would never get it over to fire, and get that cool wood up against my cheek. Seemed, too, now that I look back on it, I didn't even look down the grooves to find the bead before it exploded and set me back a-pace.

Awkward as all get-out I was, but when it was all said and done, I was still intact and the rabbit was lying in the grass.

Reckon I cried a bit when I ran my fingers through its fur. Don't know if it was because I was so darn happy or so all-out sad. Guess it was a touch of both, now that I think back.

I was proud of the first real game I had shot on my own, but couldn't get that lifeless ball of fur and flesh out of my mind as I trudged on home with him. Guess I've had that feeling ever since in varying degrees every time I hunt. You know it's right —things were just made that way. But still you feel a bit sorry. Guess that's what hunting is all about, man or boy.

I can still close my eyes and see Dad too, standing at the edge of the field with a smile about to cut his face in two. Didn't seem like I could move one foot ahead of the other fast enough to show him. Reckon I'll never forget what he said, either.

That's a fine adornment forahasenpfeffer stew you got. I suppose you think you're about the best hunter around right now, and I guess maybe you are at that. You'll shoot a lot more rabbits and other things before you're grown. )ust remember how you feel right now, busting out with pride and still a little sad. As long as you hunt, remember those feelings and the woods will be good for you. Forget them, and you might as well hang up that gun right now. Those animals don't owe you a thing, but you owe them a whole lot for what they'll teach you about living. Reckon he was right. THE END

Notes On Nebraska Fauna Giant Canada Goose

Once considered an extinct race, handful of these birds were rediscovered in 1962. Captive flocks like one near Wilcox are contributing to their recoveryCANADA GEESE, because of their beauty, their sounds, or legend, stir the emotions. The sight of a travelling V in the sky, or the distant honking of geese in the night always stop us. Recent publicity about a large goose has generated even more interest. Numerous inquiries about what he is like and how he can be recognized have arisen.

Taxonomists have divided Canada geese into a dozen or more subspecies. At least four of these subspecies commonly migrate through some part of Nebraska each spring and fall. A fifth form known as the giant Canada goose, Branta canadensis maxima, used to breed in Nebraska and still frequents the state in limited numbers.

It is not known how many of these birds there are, but the total is small compared with other Canada goose populations. Due to protection in some local areas and restoration efforts of various conservation agencies, the giant Canada goose is increasing his numbers.

Formerly, these geese bred over a large area in more southerly latitudes than other species and subspecies of geese. Their breeding range once encompassed the southern half of the prairie provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba as far south as central Kansas and the Ohio River Valley between Ohio and Kentucky. Nebraska records are few and far between, but accounts of nesting Canada geese are existent in the Sand Hills Lakes region and along the Platte River. These records indicate their presence during the late 1800% but one party recording bird observations listed Canada-goose broods on Sand Hills Lakes as late as 1904. These were probably giant Canada geese.

Wintering areas are widely scattered and frequently extend no farther south than necessary for food, water, and security. The Platte River in Nebraska offers these elements most years. Geese in more southerly latitudes remain in their nesting regions and do not migrate except during years when too much snow and excessively cold weather make food and water unavailable. Because of these inclinations, they are late migrants. Fall arrivals in Nebraska generally occur from the middle of November to early December. Data compiled at various federal refuges in North Dakota, where efforts are being made to restore Canada geese to their former breeding ranges, indicates that the giants depart for the south November 15 to 20 most years. In South Dakota they leave around the first of December. Biologists at the Crescent Lake National Wildlife Refuge north of Oshkosh have recorded departures from late November to mid-December.

The Nebraska Game and Parks Commission maintains a captive flock of Canada geese at the Sacramento Game Management Area near Wilcox. The flock contains some giant Canadas now, and the conversion to all giants will be completed in two years when young birds now on hand reach breeding age. This production flock is providing goslings for release in the Sand Hills Lakes region. The first release of 94 goslings was made in 1970 in the eastcentral Sand Hills. These birds will reach breeding age in thespringof 1973.

There is considerable interest amongst hunters wanting to know how they can distinguish these birds from other Canadas, and amongst game breeders wondering about their stock.

Branta canadensis maxima is the largest of wild geese. There are, however, some size gradations overlapping between larger individuals of other species and smaller ones of this species. If your bird weighs 14 pounds or more he is almost certain to be one of this race of Canada geese. Adult males may range from 10 or 11 pounds up to more than 20. The larger males are more apt to fall in the 13- to 18-pound class. Adult females may range from 8 to 12 pounds. They have wingspans up to six feet, sometimes more. They are characterized by long wings and necks. Their bodies are more elongated —less chunky —than those of others. They have somewhat longer legs and larger bills, too. The feet are impressive in size. These are light-colored birds with almost white underparts. There is sometimes a narrow, white ring at the base of the black neck which is not present on other races of large Canadas. White spots over the eyes or on the forehead are common, and are a good characteristic of the giant Canadas. Another common characteristic is a small protrusion or hook at the top and back of the white cheek patch.

In the field, the shallow, slow beat of the long wings, white bellies, and long necks are characteristic. Local flights are generally low, often no higher than 50 feet above the ground and seldom in groups larger than 20 or 25. Groups of 6 to 12 are more common. They are usually silent in flight, but when they talk, their voices are lower than those of smaller birds. They know where they want to go, proceeding directly to their destinations in flight, then set their wings and drop in. Though other geese may be in the area, they stay together and maintain their group. THE END

HENS IN PEN

(Continued from page 43)predators, was erected around the one-acre plots. The tops of the pens were left open so that wild cocks could fly into the pens to carry out breeding. Hundreds of posts and thousands of feet of wire later, the pens were completed. Feeders and waterers were then placed in each pen, making them ready for the hens.

Game-farm hens were stocked in the pens April 19 and 20. The hens were stocked at densities of 10, 20, and 40 birds per acre. Different populations would allow more accurate production analysis. While normal nesting density of wild hens is about one per acre, higher densities would be needed to make the project feasible.

Each hen received a leg and a wing tag to aid in individual identification. Primary feathers were pulled from the untagged wing to prevent normal flight, though it is regained after four to five weeks. Although this method had not been used before, it was chosen for several reasons. The flightless period would allow enough time for insemination, nest establishment, and hatching. The hens would then be capable of flight and could leave the pen with their chicks soon after hatching. The small chicks would be able to exit through the two-inch mesh wire shortly after hatching.

Once the hens had been stocked, it was a matter of waiting to see if the experiment would materialize as anticipated. Pens were watched closely the first several weeks for signs of any sick birds or birds killed by predators. Transects to analyze vegetation were established and searches for dropped eggs and nest forms were conducted during the second and third weeks. After the third week, human activity in the pens was limited to essential feeding and watering.

Since successful mating depended upon wild cocks flying into the pens, it was important that their response to the hens be measured. To evaluate this phase of the experiment, many mornings were spent observing. Response of the wild cocks was positive. The day following stocking, cocks were observed strutting about the pens crowing and displaying for the newly arrived females. Cocks were most readily attracted to the high-density pens (40 birds per acre), but within a week had dispersed to all of the pens. Seldom was more than one cock observed in a half-acre pen. As a result, there were few confrontations between cocks. The boundaries of the halfacre pens appeared to limit the size of the cocks' territory and reduced controntations.

By mid-May, sightings of hens became less frequent, indicating advanced incubation. On the morning of June 1, the first brood of young pheasant chicks appeared a small group of four inside one of the lowdensity pens (10 birds per acre). Observations focused on the number of different broods, their size, and whether they were leaving the pens. Broods ranging in size from two to nine chicks were sighted. Most of them left the pens at one week of age.

The tall, native grasses in the area acquired a hint of fall color by mid-September. The pens were silent now, mere reminders of past events. The breeding season had passed, as had the nesting season, and the sights and sounds associated with these biological phenomena would not return until the following spring.

Time has elasped, and the project is now entering the final evaluation phase. Data must be statistically analyzed before final results will be known. Meanwhile, it has been established that wild cocks respond to penned hens; that at least some of the hens bring off broods; that pulling primaries offers a means of holding the breeding hen in an open-top pen; that the natural replacement of primaries allows the hen and her brood to leave the pen soon after hatching; and that hens prefer cool-season vegetation for nesting sites.

Production was below that deemed necessary to make this method feasible forwide-scale application. The 140 hens estab- lished 210 nests, of which only 23, or 11 percent were successful, while 12 to 15 percent of nests in the wild are successful. These birds produced more chicks on a per-acre basis, but the number of chicks per successful nest was only half of that normally produced by wild birds. Final analysis will determine whether this technique is economically sound. THE END

THEY'RE AT THE POST

(Continued from page 35)windows. It acts in much the same way as a stockbroker when he sells shares in a company, taking a percentage on the transaction as commission. The betting public pays the money in and the winning public takes the money out, with the track taking only a percentage of what it collects. Parimutuel is one of the fairest means of wagering yet devised, since the public makes the odds and each bettor wagers against others of his kind, not against the track. Fairness is one of the cornerstones of the racing industry in Nebraska, and for the future of the sport, it is vital that it remain that way. This is where the majority of the Nebraska State Racing Commission's work comes in.

The commission points out that every facet of track operation is closely monitored. It staffs field offices at each plant, and everyone from the hot-dog vendors to the horse trainers and jockeys themselves must be licensed. Each horse is tested for health and the absence of tampering, which might affect the race, and each track has a three-man board of stewards to keep things honest. Then, there are state and local firesafety regulations which must be met and security rules which must come up to certain standards. The beginning of each race is under the watchful eye of an official starter certified by the racing commission, and even the clerk of the scales is carefully chosen to insure fairness and the ultimate in sportsmanship. All in all, the stigma of cloak-and-dagger mobsterism which sometimes dimmed the image of horse racing at other facilities in the nation is non-existent in Nebraska, and the whole affair spanks of good, clean fun.

Horse racing is far from having no troubles, though. Early this year, the number of tracks in Nebraska was cut from 6 to 5 when Madison Downs cashed in after 36 years of operation. The track had been running in the red for some four years, and dates were withheld, the racing commission said, to provide the strongest racing front possible in the state. Two other tracks, one at Alliance and the other at Mitchell, closed down with the 1963 and 1967 seasons respectively, but the commission denies any sort of a trend despite the fact that these operations were smaller tracks.