WHERE THE WEST BEGINS

NEBRASKAland

April 1972 50 cents ANGLING EDITION COLORFUL CLOSEUP OF TROUT & BASS AT CLEAR LAKE PIKE PRODUCTION

LAKEVIEW ACRES

ON BEAUTIFUL JOHNSON LAKE LAKE ACCESS IN FRONT OF YOUR LOT FOR DOCK OR RAMP CABINS WILL BE BUILT THIS SPRING- FOR SALE FOR LEASING BY OWNERS FINANCING AVAILABLE ON LOTS OR HOMES. ALL LOTS ACCESSIBLE BY PAVED ROADS COMPLETE SUPPLIES AVAILABLE IN BAY AERA AT MARINA-BAIT-BOAT DOCKS-RAMP-GROCERY AND BEVERAGE SUPPLIES HOME OR CABIN LOTS NOW AVAILABLE Lots are ready now for building your cabin or home. Or buy lot complete with a Mobile Home ready to move in and enjoy. Private property area-regular home loans can be obtained. Restricted building codes to insure like quality for entire area. All Utilities are in and ready, Electricity-Gass-Water and Telephone. All lots have concrete retaining wall and shoreline. Protected cove area. FINANICING AVAILABLE Or call Bob Cupp, Mgr. Lexington, Nebr. 30/324-2678 Write For Free Color Brochure To LAKEVIEW ACRES, INC.For the record... Bounty of Trees

"The woods are lovely, dark, and deep." So said poet Robert Frost in verse, but a few decades ago.

And, what school child has not committed to memory the immortal lines penned by Joyce Kilmer: "Poems are made by fools like me, but only God can make a tree."

How many of us realize the value of a tree? Just where does it fit into man's scheme of things?

Throughout the centuries, man has looked to the tree for a multitude of his needs. It is a haven for birds, other wildlife, and small boys. It gives us timber for houses, paper products, and even the first synthetic fibers. Trees provide cool respite from the burning rays of the sun; fuel for the fire. It bears fruits for food and even gives off the oxygen vital for man's very survival. It fills so many of man's needs and demands that it is all but impossible to enumerate them.

Almost from the time man learned to walk erect, he has depended on the bounty of trees. Somehow they have always been there, but will that be true for the generations to come?

When European man came to the New World, he was confronted by seemingly endless expanses of forests. During the relatively short span of time from then to now, man, the exploiter, has diminished those great timbers at a precipitous rate. Gone now are the days of unlimited cutting.

Statistics indicate that unless we recycle, use substitutes, and simplify construction, lumber needs will skyrocket to 18.8 billion cubic feet by the year 2000, and they will be 2.2 billion cubic feet more than the anticipated growth. For example, today's paper needs in the United States average 560 pounds per person each year. By 2000, that figure will reach half a ton for each man, woman, and child.

What can be done? Steps are being taken to conserve our woodlands, to develop substitute materials, and even to plant "super" trees that will mature in about half as many years as presently required. Even so, man must take stock of his resources and act. But what of the national forests? These woodlands offer hope, and they represent what government can do. That is not enough, though.

This then presents an opportunity for each and every citizen to do his part. In this the Centennial year of the first Arbor Day, Nebraska's own holiday, the "Treeplanter State" can again take the lead. We can plant a tree for the future, so generations to come will know the simple joys of a tree.

While planting for tomorrow, today's citizens can also step up their contributions to the recycling effort. The U.S. now reuses only 20 percent of 12 million tons of paper annually. Other tree-short nations reprocess 35 percent. So, there's ample room for improvement.

Nebraska is No. 1. Let it then lead the way for others to follow.

April 22 is Arbor Day. Founded a century ago by Nebraskan J. Sterling Morton, this day for planting trees is now observed in 49 states and many foreign countries. For further information contact your area County Extension Agent or local Garden Center.

Speak Up

WATCH OUT- I sincerely feel all field-dog owners should be warned and a plea should go out to all landowners. I fully realize that coyote hunting can be a great sport, and man holds the vital key to our wild kingdom, but gas bombs are dangerous.

"I am not fully aware of how they work, or much less their purpose, except that they kill all that tamper with them. They are baited, gas charges hidden in the ground for the purpose of killing coyotes.

"I know the Nebraska laws on trespassing, but even a well-trained Vizla like my Gomer couldn't be taught the fence-line boundaries. After walking a milo field and coming to the end with no success, Gomer wandered into a completely unmarked pasture and was killed by one of these gas charges.

"I would like to make a plea to all farmers that feel they must use these charges to kill come what may. No warning signs will bring back Gomer, but they may save someone else's hunting partner and family pet."—James Benedict, Omaha.

WHAT PRICE WATER- I am one Niobrarian that will say Amen to Norm Hellmers' January article Conflict. The truth shall be known.

"By now the Norden Dam is supposed to cost the American public $92 million to irrigate 77,000 sandy acres. That, ladies and gentlemen, is almost $1,200 per acre. Add what the Keynesian pros call land development, then override, and your cost rises to $1,500 or $2,000. Compare this with $300 to $400 for pivot irrigation systems, and $200 or $300 for other systems. The economical structure of the O'Neill Unit would be like pouring water down a rat hole. Of course, the fast-buck clan would be there to pick it up —or dig it out.

"Dig deeper and you will find that the underground water in Holt County is being contaminated with nitrate. A nitrate hazard does not exist within the 69,000-plus acres considered for development under the O'Neill Unit. No doubt Holt County's sprinkler irrigation has helped create this problem. Now is the time for the state to deal with it —not add 69,000 highly irrigated sandy acres to intensify the situation.

"The recreation anticipated with the Norden Dam construction would not be an even standoff to the type of enjoyment we have on the Niobrara as it is. God forbid if we should destroy this. People from eastern Nebraska and throughout the United States almost run over each other come hunting time. And, canoeing the Niobrara is like being next to heaven, especially with children."—Martin A. Peterson, Bassett.

GREAT FUN-"I enjoyed Irvin Kroeker's article in the December 1 971 issue of NEBRASKAland (Genealogical Fun) very much. I've been a rather ardent genealogy fan for quite a few years, and am presently working on a genealogical index." — Kermit B. Karns, Kansas City, Missouri.

CURE MADE EASY-"Enclosed are six suggestions for 'curing' the problems of our youth. Sometimes it seems we plan our problems ahead rather than trying to head them off." —Roy A. Speece, York.

CURE 1. Take from your youth the privilege to roam the fields and creek banks by posting NO TRESPASSING signs, and they will roam the streets and alleys of the cities. 2. Take from our youth their love and respect for wildlife through lack of firsthand education, and they will learn on their own of marijuana and booze. 3. Take from our youth the joy of their sporting arms by gun control laws, and they will play it safe with smuggled arms and concealed weapons. 4. Take from our youth their interest in hounds, retrievers and bird dogs because dogs are nuisances, and they will calm the neighborhood with loud mufflers and screeching tires. 5. Take from our youth the thrills of their trap lines and hunting trips to prevent cruelty to animals, and they will be kind to their fellow man with riots and gang fights. 6. Take from our youth the sensible harvest of feathers and fur at the insistence of amateur ecologists, and they will reap their grim harvest on late nights with cars. SAUSAGE RECIPE-"This recipe is being used quite a bit around here:" 48 pounds beef 10 pounds bacon (not cured) 4 cups salt 8 tablespoons pepper 4 tablespoons allspice 1 clove 2 tablespoons saltpeter Some mustard seed."We use Wright's liquid smoking on the outside." —John D. Friesen, Henderson CRANES —"I found a picture and description in a 100-year-old book of a bird that you are protecting each year. Maybe you can use this historic information." — Lawrence Dokulil, Omaha.

THE AMERICAN CRANEThe crane, of which our engraving represents a fine specimen, is a large wading bird of the order Grallatores, and different genera of the species are found in Europe and America. The American crane (Grus americanus) furnishes a good typical example of the whole class. Its long bill is dusky, turning yellow toward its base; the top and sides of the head are of a brilliant red; the feet are black, and the plumage white, except the primary and adjacent feathers, which are brownish black. The length of the full-grown bird, from the bill to the tip of the tail is often 34 inches, and to the end of the claws 65 inches; the young birds are of bluish grey color, with the feathers tipped with yellowish brown.

Cranes are common in our Southern and Western States from October until April, when they retire to the North.

Their hearing and vision are very acute, hence they are diffcult to approach. They roost either on the ground or on high trees. Their nests are usually built of coarse materials, and are placed in high grass; the eggs are two in number, and are hatched by the alternate attention of both birds. They are easily tamed when captured, and may be kept on vegetable food.

GRAB A COMET THEN HANG ON!

Are you ready for the most powerful of Kawasaki's magnificent 3-cylinder Tri-Stars? It's here-the mighty Mach IV 750 CC with pure, screaming power waiting to be harnessed. See it. Ride it —the most exciting motorcycle in this or any other world, the meteor of Tri-Stars. Mach IV is designed to be the brightest star in the Kawasaki universe. The acceleration is phenomenal, unquestionably the machine of the future, engineered for the astro-generation. The Mach IV is just one of Kawasaki's many Super Stars for 72. See the 500 CC Mach III, 350 CC F9, 350 CC Mach II, 250 CC F8, 175 CC F7, 125 CC F6, 100 CC G4, and the 90 CC G3 at the dealers below today.

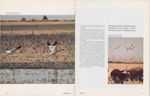

They Tarried a While Last year, a trio of migrating whooping cranes stopped near Minden, offering a unique opportunity to observe them

Refuge for Bass Originally after northern pike, a fishing party ends up with a trunkful of bass at the wildlife refuge near Valentine

Forts Kearny The first Fort Kearny lasted only two years until 1848 when it was moved 150 miles west to its present location

Concern for Tomorrow Young students portray with art what they think should be done about the destruction of wildlife habitat and about pollution

Boxed numbers denote approximate location of this month's features.

NEBRASKAland

Outdoors FOR THE RECORD: BOUNTY OF TREES Harold K. Edwards 3 HOW TO: FILET, CLEAN, AND SMOKE FISH 11 CALLING ON THE BROWNS 16 TREE-CLIMBING LUNCHBOX 20 THEY TARRIED A WHILE 22 REFUGE FOR BASS Lowell Johnson 28 SECOND TIME AROUND Irvin Kroeker 34 SPECTRUM IN THE STREAMS Greg Beaumont 36 CONCERN FOR TOMORROW 42 NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA: FLATHEAD CATFISH Larry Messman 48 WHERE TO GO: NEBRASKAland FISHING 57 Travel FORTS KEARNY Warren H. Spencer 30 ROUNDUP AND WHAT TO DO 60 General Interest SPEAK UP 4 'POSSUM SNAKE 8 OUTDOOR ELSEWHERE 66 EDITOR: DICK H. SCHAFFER Managing Editor: Irvin Kroeker Senior Associate Editor: Warren H. Spencer Associate Editors: Lowell Johnson, Jon Farrar Advertising Director: Cliff Griffin Art Director: Jack Curran Art Associates: C. G. (Bud) Pritchard, Michele Angle Photography Chief: Lou Ell Photo Associates: Greg Beaumont, Charles Armstrong, Bob Grier NEBRASKA GAME AND PARKS COMMISSION: DIRECTOR: WILLARD R. BARBEE Assistant Directors: Richard J. Spady and William J. Bailey, Jr. COMMISSIONERS: Francis Hanna, Thedford, Chairman; Dr. Bruce E. Cowgill, Silver Creek, Vice Chairman; James W. McNair, Imperial, Second Vice Chairman; Jack D. Obbink, Lincoln; Gerald R. Campbell, Ravenna; Wiiliam G. Lindeken, Chadron; Art Brown, Omaha. NEBRASKAland, published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. 50 cents per copy. Subscription rates: $3 for one year, $5 for two years. Send subscriptions to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, 1972. All rights reserved. Postmaster: If undeliverable, send notices by Form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second-class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska. Travel articles are financially supported by the Department of Economic Development.

'Possum Snake

"Let sleeping rattlesnakes lie" is my motto now. It only took one time of handling a live one for me to learn

As I played with the rattler, I didn't know that he would soon spring back to life

RATTLESNAKES are a curiosity for most people—aimost any snake is, I suppose. Some folks are downright afraid of them, others think they are interesting, and still others can take them or leave them. I am one of those who would rather leave them.

Several years ago, in the early spring of 1968, a neighbor, Delbert Kent of rural Holbrook, stopped by my farm. He had been checking his cattle, and because of wet ground, used his tractor instead of a pickup. Now, Delbert has killed a lot of rattlesnakes, and he claims it's easy. He has often told me: "Why, you can kill one with a fly swatter."

Anyway, he had killed one that morning. I don't remember what he used, though I guess there was a wrench or something on the tractor. No, I guess he worked it over with a sunflower stalk. Anyway, he didn't beat it up badly or anything-it just had a little blood on the head. When he drove into the yard, he started to tell me about the snake even before I could say hello. It was draped across the tractor's transmission.

I had never killed a rattler, nor seen one for that matter, so I was sort of interested. I asked him at the time if he was sure the cussed thing was dead, and he answered that it didn't take much to kill one. Well, I took the snake from him and inspected it. The kids were home, so of course they, and the cat and dogs had to see, too. I remember opening the mouth so they could look at the fangs with the little holes where the venom comes out. And, we rattled the tail and examined the scaly body. The snake was not a large one, only average size, probably 26 or 27 inches ong.

Well, you only look at a snake so ong, so after a while I handed it back to Delbert, and he again laid it across the transmission. He said he was going to stop by another farm and show the snake to Art Mock on his way home. So we said goodbye and I didn't think much more about it until later. I don't remember exactly how much later it was when I heard the rest of the story, but I have been reminded of it quite often since then.

It seems that when Delbert drove into Art's yard, Art was up on the porch. Delbert went up to the porch and said, "Hey, come out here and see the rattler I just killed."

Art, who had the advantage of facing the tractor, answered just about as enthusiastically. "Nope. I'm not going out to look at any snake you killed until you go out and kill the one that is crawling up on the seat."

Sure enough. There was a live rattler crawling around on the tractor. The heat and jostling had revived Delbert's recently killed reptile, so he had to dispatch it again. That was cutting it pretty close, for if the snake had revived a minute sooner, that tractor seat would have gotten a little crowded.

A day or two later, I heard about the revived snake, and then I really got to thinking. Here the kids and I had played with that rattler, and all that time it had only been asleep. It gave me a funny feeling just thinking about it. People asked me later what I would have done if it had come to life in my hands. I always told them that I would have uncoiled long before the snake, and I sure would have given it quite a toss.

I haven't grown any fonder of snakes since then, and I don't know if Delbert still believes he can kill rattlers with a fly swatter, either. Whatever he uses now, I'll let him continue to work them over, but I'm not going to go out of my way to look for those rascals. THE END

Two Zebco reels for the bass fisherman who wants to be better

ZEBCO CARDINAL 4

ZEBCO 802

Any fisherman knows that success comes from being where they are, when they're hitting, with equipment you can depend on to get 'em in the boat—the kind of equipment Zebco makes. Like our newest bass reel, the 802.

The 802 is a tough, nine-ounce spin-cast reel that has all the features you could ever want, like Teflon-treated internally expanding clutch rings that assure the smoothest drag performance you ever experienced. Its low profile design fits every rod better and puts you just a finger away from effortless feather-casting for accuracy—whether it be worm'n dropoffs or buzzing spinner baits in the brush. And, it comes loaded with the best line money can buy—DuPont's Mod II Stren®fluorescent monofilament.

What do you do when the wind blows north or the water's clear enough at ten feet to read yesterday's calendar? Check the records of bass anglers across the country who load up a Zebco Cardinal 4 with six-pound Stren line and go to the small, lightweight jig'n reels. It's tough to beat success. That's why it's hard to beat a Zebco Cardinal 4 for open-face spinning. It's the finest spinning reel in the world for some mighty good reasons—like ball bearing drive, totally corrosion-proof construction, dual bail springs to make it virtually failure proof, and its exclusive stern mounted drag control. Other reasons will be obvious the first time you pick up a Zebco Cardinal.

Take your pick or pick 'em both, whatever your fishing style demands. Then take a good look at the rods Zebco makes to go with these reels. For balanced performance, they're the best.

HOW TO: Fillet, Clean, and Smoke Fish

Catching fish is only part of the problem, as any angler will tell you. There are lots of secrets and tricks involved in enticing a fish to the hook. But, cleaning those critters after a day on the water is far less enjoyable and almost as time-consuming as catching them.

There are a few tricks to cleaning fish, though, which take much of the drudgery out of the task. Many anglers (or their wives) know these secrets, but some folks still operate on their catch with old-fashioned, and mostly unnecessary techniques.

For the benefit of those still clinging to the "good old way", but who are open to suggestion, here are several good ideas for cleaning. And, if you want to prepare a delicacy, try smoking a fish.

As with other fish, make first cut on catfish behind pectoral fins, then along the backbone toward tail

Slice down to rib cage, work blade around bones to belly, freeing meat

FOR SOME REASON, catfish and bullheads are usually processed in the most cumbersomemanner. The fish is awkwardly grasped by the horned head, a cut is made around the skin behind the head, and pliers are used to peel the rubbery hide off. Then fins and other protrusions are removed, then the intestines.

All this is pretty tough work, and it leaves all those bones inside to be picked out and piled in a heap somewhere around the dinner plate. Although it may come as a surprise to many, catfish, too, can be filleted, removing bones and skin with a few swift cuts.

Just as with most other fish, make a cut behind the gill cover down to the backbone. Then, cut along the backbone about two-thirds of the length of the fish. Cut deeply, clear down to the rib cage. The back meat can then be pulled away from the bone and the knife can be worked around the rib cage to the belly, freeing the fillet from the carcass. Behind the ribs, move the blade parallel to the backbone and cut clear to the tail, but leaving the skin attached.

Flop the meat back so the skin is down. Start another cut between meat and skin, making a slight, slicing motion, and the fillet will come away with nothing left on the skin.

Wash the meat, blot it dry with a paper towel, salt it lightly, and refrigerate it until dinner time. Not only will the boneless pieces be more pleasant to eat, but they allow the fish to be prepared in many different ways. With large catfish, the fillets should be cut into smaller pieces for convenience. Whatever the size, however, the proof that this method is best is in the trying. Put away the pliers and bring on the skillet. (Continued on page 12)

Next, lay blade flat against backbone and cut to tail, but leave skin "hinge"

Starting at hinge, slide knife between skin and meat. Result —a boneless steak

ENJOY FONNER PARK

RACING EVEN

MORE THIS YEAR...

STAY AT

OUR 1-80

LOCATION IN

GRAND ISLAND

US 281 & I-80

Grand Island (68801)

Near Stuhr Museum, Fonnor Park,

House of Yesterday in Hastings. Lounge,

Suites, 152 Rooms, and beautiful new dining

facilities for your convenience.

WEEKEND RACING

FRIDAYS & SATURDAYS

March 3 & 4, March 10 & 11,

March 17 & 18

RACING MONDAY THROUGH SATURDAY

March 21 through April 29

Phone: 308-384-7770

HUNTERS-TRAPPERS

Trap furbearers for bounty and fur "TRAPPER'S GUIDE"

tells how, 32 page booklet containing trapline methods,

trapping stories, hints, tips, current issue $1.00 ppd.

Hurry, order today-supply limited.

HAROLD BOSLEY, Trapline Publications

2115 NL Seventh Street

Moundsville, W. Va. 26041

AUTHORS WANTED BY

NEW YORK PUBLISHER

Leading book publisher seeks manuscripts of all

types: fiction, non-fiction, poetry, scholarly and

juvenile works, etc. New authors welcomed. For

complete information, send for free booklet R-70.

Vantage Press, 516 W. 34 St., New York 10001

SELL NEBRASKA!

All Nebraskans should help sell our state, especially as an exciting place to spend a vacation. One

of our major attractions is fine fishing. If you want

to sell fishing licenses, apply to the Game and Parks

Commission in Lincoln.

NEBRASKA ADJUSTMENT CO.

CLEANING TROUT

ENJOY FONNER PARK

RACING EVEN

MORE THIS YEAR...

STAY AT

OUR 1-80

LOCATION IN

GRAND ISLAND

US 281 & I-80

Grand Island (68801)

Near Stuhr Museum, Fonnor Park,

House of Yesterday in Hastings. Lounge,

Suites, 152 Rooms, and beautiful new dining

facilities for your convenience.

WEEKEND RACING

FRIDAYS & SATURDAYS

March 3 & 4, March 10 & 11,

March 17 & 18

RACING MONDAY THROUGH SATURDAY

March 21 through April 29

Phone: 308-384-7770

HUNTERS-TRAPPERS

Trap furbearers for bounty and fur "TRAPPER'S GUIDE"

tells how, 32 page booklet containing trapline methods,

trapping stories, hints, tips, current issue $1.00 ppd.

Hurry, order today-supply limited.

HAROLD BOSLEY, Trapline Publications

2115 NL Seventh Street

Moundsville, W. Va. 26041

AUTHORS WANTED BY

NEW YORK PUBLISHER

Leading book publisher seeks manuscripts of all

types: fiction, non-fiction, poetry, scholarly and

juvenile works, etc. New authors welcomed. For

complete information, send for free booklet R-70.

Vantage Press, 516 W. 34 St., New York 10001

SELL NEBRASKA!

All Nebraskans should help sell our state, especially as an exciting place to spend a vacation. One

of our major attractions is fine fishing. If you want

to sell fishing licenses, apply to the Game and Parks

Commission in Lincoln.

NEBRASKA ADJUSTMENT CO.

CLEANING TROUT

WHEN YOU PULL a lunker rainbow trout from Lake Mac's cold water in early spring, the sooner your catch is cleaned and iced down the better. You can perform the chore in seconds once you get the hang of it. While cleaning a rainbow (or any trout, for that matter) is not much different than cleaning other fish, there is little necessity for scaling rainbow because the scales are so small. Cleaning trout is probably the angler's easiest and least time-consuming job.

Use a knife with a thin, keen blade. Split the belly of the fish from vent to throat, avoiding the viscera, and stop the cut at the throat bone just behind the gills.

Now run the knife through the lower jaw plate ahead of the gills, and cut the jaw plate free. Run your thumb inside this last cut, down the throat so you can grasp the gills and lower throat bone, and peel downward, following the belly slit. The gills and all other viscera come out in one lump.

Use your thumb to remove the dark material, which is the kidney, running the full length of the fish's backbone. Rinse the fish with clean water, and it's ready for the cooler or frying pan.

First step on trout is long, shallow cut from vent to throat behind gills

Knife is now inserted in slits on lower jaw plate, and an upward cut severs it near lip

Now, use the lower jaw as a handle while inserting thumb over jaw plate

Steady pull will remove plate, fins, and empty body cavity in one lump

Scrape out dark kidney strip with knife or thumbnail, wash, and job is finished

SMOKING FISH was originally a method of preserving a part of the catch for future use, but the wonderful flavor of fish so treated has spread into the realm of gourmet foods and commands a premium price at modern food stores.

The smoking process is not difficult, and almost any fisherman can produce acceptable results on his first try. If he is camping out during his fishing foray, part of the catch can be smoked on the spot, or brought home and done on the back porch.

While many devices, from' the pioneer-type smokehouses to oil drums and old refrigerators, have been employed by many smokery enthusiasts, commercial, portable units provide a more practical approach for those not wishing to jump into the craft on a wholesale basis. These units consist of a metal box approximately 18 inches square and 24 inches high. There is a removable wire rack inside which holds the meat to be smoked. In the base of the unit is a small, low-power electric hotplate and a metal pan. The pan is filled with hardwood sawdust or chips, usually hickory, from a supply furnished with the smoker, and this is set on the hotplate where it is slowly "fried" to produce the smoke necessary to cure the food. The device is small enough to takeon fishing-camping trips, and will work wherever electricity is available. It can be stored by hanging it from a nail in the garage.

Various fish are good for smoking. Carp and drum are delicious when smoked. Smoked rainbow trout is an epicure's delight.

Preparing fish for smoking is an easy but important step. Remove the scales from large-scaled fish. (Scaling is not necessary for trout.) Wash the fish well in cold water. Remove any bloody flesh, and be particularly sure to remove the dark kidney strip from along the backbone. Fish weighing no more than 21/2 to 3 pounds can be smoked whole, though larger ones should be reduced to more manageable chunks. Pack the pieces in a glass, earthenware, or porcelainized container —never in bare metal. Using the proportion of threefourths of a cup of salt to a gallon of water, prepare enough brine to completely cover the fish. Depending on the size of the chunks, the fish should soak from 18 to 48 hours. Oversoaking is practically impossible, so if you're in doubt, use too much rather than too little time.

At the end of the brining period, any scum that has formed on the pieces can be washed away with cool water. Dry the chunks with a clean towel and arrange them on the smoking rack, taking care that no piece touches the one next to it. This will allow free circulation of the smoke. Let the smoking rack, with its load of fish, sit out in the open air for the pieces to dry about two hours while you prepare the smoker itself.

Place one of your self-smoked fish on a snack tray and get ready for compliments

Only smoker, wood chips, and a few household items are needed to turn raw fish into true gourmet delight

Place the smoker in an open area where breezes will carry away any odor. Run the power cord to a suitable electrical outlet. To prevent any possibility of shock from damp ground, set the smoker on bricks, stones, or a table. Fill the smoke pan with sawdust from the supply provided with the kit. You can also use green apple wood, cherry wood, or, believe it or not, ground corncobs. Sprinkle a little water on the sawdust and stir until the moisture is evenly absorbed. Bone-dry sawdust has a tendency to smoulder too rapidly and may even flare up. Blazing should be strictly controlled, as a whole batch of meat can be ruined in a few seconds.

Load the rack into the smoker and turn on the heating element. In a few minutes the sawdust in the pan will begin to char. Convection currents carry the smoke up to fill the smoker, and excess smoke and heat escape through vents at the top. A large volume of smoke is neither necessary nor desirable. If the amount of smoke escaping from the contraption resembles a factory chimney, your smoke-producing material is being consumed at too rapid a rate, and it can cause a bitter flavor in the final food product. Some of these smokers have a built-in rheostat and the heat can be reduced. With those that do not, blockage of some of the lower air holes, or sprinkling a little water on the sawdust in the fuel pan, will help. Maintain a thin, constant volume of smoke, replenishing the saw dust whenever necessary for about six hour . you want a lightly flavored product. For a really pronounced flavor, smoke about 12 hours.

Brine is first step. Add 3/4-cup salt to each gallon of water, or dissolve until solution floats raw egg. Mix enough to cover fish.

In crockery, glass, or plastic, "brine" fish for 18 to 48 hours

All during the smoking cycle, brush the fish very lightly, interior and exterior, with cooking oil on a pastry brush at half-hour or hourly intervals. It is important to be sparing with each application of oil, as too much will seal the meat, thus preventing it from absorbing the smoke as it should.

At the end of the smoking period, the fish should have a warm, brown color like worn saddle leather. The small amount of heat generated by the smoking element has cooked the flesh, and it can be eaten right from the smoker. The fish will keep well in the refrigerator for two or three weeks, or it can be packaged, frozen, and stored indefinitely.

As with all unfamiliar processes, practice and experimentation adapt the smoking technique to an individual's preference. Ultimately you will produce smoked products done exactly to your own taste. So, have at it, and good eating! THE END

After rinsing, blot fish dry, put on wire racks, and air dry for an hour

At half-hour intervals, brush oil on inside and outside of the fish

You can't buy a better Cottage Dock!

LONGER LASTING, United Flotation Systems docks are the most economical...strongest ..most stable...most versatile...maintenance-free docking equipment available. Advanced engineering and modular design make it possible for you to install the same type of dock used in many of the country's leading commercial marinas.

Docks can also be left in the water year-round when there are no moving ice conditions.

GOES TOGETHER EASILY...No other flotation system goes together so easily and so quickly! Docks arrive completely assembled, ready to slip into the water. Unique unitized structural design and rugged construction permit easy installation and removal without damage to the system.

UNSINKABLE PONTOONS...Outperform all other types of flotation-metal drums, exposed foam billets, plastic tubs, etc. Withstands the most rigorous water and weather conditions...punctures...fuel...heat...sunlight...erosion...non-moving ice...rust...burrowing animals...floating debris...temperature variations. Provides unequalled maintenance-free service life.

DESIGN YOUR OWN DOCK LAY OUT! Now you can select the exact dock to suit your individual requirements or add on dock sections as your needs change. Where straight dock is desired, use finger dock. These can be connected to each other (end to end) to make practically any length flotation platform. "T". "U" or "L" dock connections are made to the base dock at any location desired. To make any configuration, use a base dock with the desired number of "finger" docks.

for more information write or call United Flotation Systems, by: LINCOLN MANUFACTURING CO. 4001 Industrial Avenue Box 30303 Lincoln, Nebr. 68503 Phone (402)434-7418

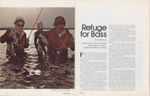

Refuge for Bass

Pelican Lake south of Valentine yields sagging stringers, satisfied appetites for anglers

FOR A FEW lucky (or determined) Nebraska anglers, there is no end to their efforts because of the weather. They reason that if the season is open year-round, they should be out there all the time. For most, however, fishing comes in short snatches when time and pleasant weather permit.

Probably because of these limiting factors, the change from winter to spring is a nebulous one, and the angler is often overanxious at the first signs of good weather. He wants to go lakeside and try out all his new lures even though the fish are still undecided as to whether they should lie low, move around and start eating, or take up the seasonal rituals of spawning.

Second-guessing fish is never sure-fire, especially by infrequent guessers. But this time, the weather was great and it just might be the time to cash in on northern pike. So, on the basis of the elements and with high hopes, a trip was arranged in mid-April, 1971, to the Valentine National Wildlife Refuge; Pelican Lake in particular.

Dick Schaffer, NEBRASKAland Magazine editor, was planning a trip in that direction to do some radio tapes, so I loaded my fishing gear into the trunk of his car. He allowed he might find time to wet a line, too, so we set out from Lincoln.

Nearing our destination toward sundown, we noticed a lot of wildlife, so naturally we began a tally which grew steadily. By dark, 16 deer, a roadside covey of quail, and scores of pheasant and grouse had been under our scrutiny —all within a few hundred yards of the highway.

"My neck is going to be sore tomorrow from all this gawking around," I jokingly told Dick when darkness finally brought a halt to our tabulations. Unfortunately, those words came back to haunt me during the next few days.

At the breakfast table next morning, Corky Thornton joined us. He sipped coffee and agreed to go fishing, too, with very littie coaxing. "I really shouldn't, but I haven't been out for several days,' he said.

One of the most avid anglers in the Valentine area, and completely familiar with fish habits and lakes on the refuge, Corky was just what we needed. We reached Pelican Lake about midmorning just as several large flocks of pelicans flew overhead, causing us to stop several times en route for pictures of them in flight. The day was ideal—clear and sunny. Although reports of fishing success were not overly promising, our crew was confident of good action.

Driving clear to the east end of Pelican, we donned waders, rigged steel leaders and a selection of lures, and splashed into the frigid water. Then it came. With each passing minute my back ached more until I felt as if one of those big northerns had sunk his teeth into my spine. Sloshing around among the clumps of reeds didn't help, and since I wasn't getting hits anyway, I retired to shore after an hour or so to watch Dick and Corky operate.

They were not having much difficulty. Although a few other anglers on the lake were having no luck, both my partners were catching fish. Dick landed three, but returned them all to the water because they were only pounders. Corky caught a small one, then latched onto what must have been at least a four-pounder, but he let him slip out of his hands as he fiddled with the stringer. He didn't bat an eye or come up with any appropriate words over the incident, however. After about four hours of fishing, their take consisted of two keepers, each weighing between two and three pounds, which Corky had taken near a finger of land a short distance up the shoreline.

Insigificant in the Sand Hills' expanses, trio of anglers revels in its singular solitude.

A heavyweight largemouth yields to Dick's enticing spinner

Dick tries for one more bass as Corky, his guide and companion, guards day's weighty stringers.

"It might be a little early in the season for northerns, but I have taken some good bass at Clear earlier than this before," he offered in way of persuasion.

"O.K., let's give it a try," Dick and I chimed in unison, at the same time shuffling through our tackle boxes in search of bass-appealing stuff. When I saw Corky snapping a plastic worm onto his line, I chose one, too. Dick, however, elected to use his Mepps spinner, or an Oriental imitation of one.

Arriving at the isolated Clear Lake several miles north and a bit east of Pelican, everyone piled out but me. I came out slowly, by now almost crawling on hands and knees and feeling ridiculous doing it. So, Corky and Dick were up to their armpits in water and busily engaged in checking out the new location before I even got to the shoreline.

The wind was at our backs and had picked up somewhat as we cast north into deep water. I moved to Corky's left and watched him operate for several casts, then tried to duplicate his efforts. His worm was rigged with a single hook right near the front end so that his retrieve —fairly slow but steady along the bottom —made it look like an inactive worm heading for sanctuary on land.

Corky had caught three fish already. He held them up for me to see. They looked like two pounders. I paid little attention to Dick, who was working his spinner down the lake a ways.

With cold water occasionally slopping over the tops of my waders because of the gusting breeze, I moved as little as possible because of my ailing back. After perhaps a dozen laborious casts and retrieves at various speeds, I felt a taker nibbling at the bait. Letting the line go slack for a few moments, I reared back and felt a telltale weight still hanging onto the line.

Laughing excitedly, yet finding time to brag loudly in Dick's direction, "Hey, I got one," I worked the bass in and finally got him in hand. He was about a pound (Continued on page 55)

Tree-climbing Lunchbox

Forest Ranger Dick Korbel encourages hunters to harvest porkies at Halsey

Skinning prickly critter is fairly simple task

Without hide, porcupine carcass has plenty of bone, little meat.

Otherwise harmless, porcupine incurs wrath (or damaging forest

First step in cooking is stewing to tenderize stringy, sinewy meat

Already dark, meat gets a final browning over grill

Belying his looks in the wild, porky proves to have pleasant, mild taste

ONE MIGHT SURMISE, after considerable time and effort, that the dull-witted, slow-moving, and downright homely porcupine is actually a shrewd, sneaky, calculating creature. At least that might be the opinion of anyone hunting them.

Certainly, some porcupines are killed in Nebraska each year, but most are chance encounters. While going about their business, hunters or ranchers come across a porcupine waddling across open spaces, or they spot one in a tree. In many cases, the porcupine's demise follows.

This may seem like senseless killing, but actually, there is little that can be said in the porcupine's favor. He has, to say the least, few saving graces. He is relatively innocuous, but that hardly outweighs his bad points. And bad points do not mean his many barbed quills. No indeed! The porky is basically an undesirable, or so it would appear.

Anything that trudges around the territory eating tops off trees cannot be classified as neat. Operating in much the same manner as a huge termite, the porcupine ascends the most classic and attractive coniferous trees and nibbles bark off the trunk and sometimes off side branches not off the entire tree, mind you, but only from a narrow strip, and usually entirely around the trunk or branch.

Whether this is by design or merely because of convenience—the porcupine being rather lazy and short-legged —is not known. But the results are consistently predictable. From where they nibble on up dies, leaving a weakened and crooked tree. It is no longer of value as lumber even if it survives. And, chances of survival are considerably lessened after the tough-toothed porky has a snack. With trunk and limbs bared, those portions of the tree (Continued on page 51)

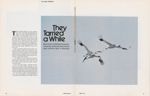

They Tarried a While

Best-known endangered species, whooping cranes are becoming a more common sight in Nebraska

THERE NEVER WERE very many whooping cranes, and today the population remains at a low level. But thanks to the efforts of many people, they have recovered from near extinction. Thus it is significant to observe these rare birds in the wild. But rarity alone does not convert what would ordinarily be a mundane event into a special occasion. What does make the sighting of a whooping crane significant is the unique relationship which has developed between Americans and their great American crane, Grus americana.

There is something about this enormous, elusive bird which creates awe and concern. Perhaps these feelings stem from a feeling of regret resulting from what happened to the passenger pigeon and the slaughter of bison. In that vein, we have made the perpetuation of this species a national conservation priority.

Or, perhaps, we are awed by their beauty. These cranes have pure-white plumage and black-tipped, seven-foot wings. They are tall (five feet or more), and have noble, crimsoncrowned heads.

Their rarity, their beauty, and their elusiveness are all factors which continue to elicit emotional reactions from the fortunate few who witness the whoopers. Last fall, a few Nebraskans had the rare opportunity of watching cranes and experiencing the mixtureof emotions they evoke.

For more than a week in mid-November of

1971, a trio of whooping cranes lingered here.

A flooded field southwest of Minden became

their resting spot where they recreated a scene

now all but vanished.

their resting spot where they recreated a scene

now all but vanished.

While it is unusual to see whooping cranes in the wild, they often stop at sites along the Central Flyway to feed during migration, occasionally in Nebraska as this trio did. They have sometimes been observed traveling in company with sandhill cranes.

These three cranes were a family unit —a male, a female, and one offspring. Almost as tall as its parents, the young bird could be identified by its brown, mottled plumage. The adults would scan the water, then deftly spear small carp, offering each fish to the youngster or dropping it on the ground. While feeding, the cranes slowly worked their way around the pond. After eating, the birds lined up in preparation for flight, the youngster taking its place between the adults. With slow, but powerful strokes of their huge wings, they rose quickly into the air. Their destination was a stubble field several hundred yards away. There they sought more food —grain—and gravel to grind it down in their gizzards.

Flights both north and south are closely monitored to insure the safety of once-doomed speciesMature crane may stand tall as a man, have seven-foot wingspan

Flooded field near Minden has special attraction for family

Seemingly ungainly on ground, birds find element in the air

The three cranes soon left Nebraska to join others of their kind in Texas for the winter. Now it is spring again and the birds are winging northward to their breeding grounds in Canada. There they will remain until the following autumn when they will begin their flights southward once more. Yet, in their native habitat, they will not lose the uniqueness, nor will they be forgotten.

Throughout their stays in both Canada and Texas, whooping cranes are studied in hopes of furthering their recovery from the brink of doom. In them, we may well find the key to survival for other species which face extinction. Perhaps, one day, man will be able to sit back and admire his handiwork of preserving species previous generations nearly annihilated, and find solace in the fact that, despite eons of meddling in the ways of nature, he has restored that precarious balance. Success is a long ways off, however, and for the moment, modern minds must seemingly content themselves with helping the species which shows the most success—the whooping crane. In that effort, the flock's movements will be closely monitored.

And so, as they travel, their safety is our concern. Their flight is being closely followed. Perhaps they will tarry again and offer chance for another rare encounter. THE END

Whooping cranes have become the conscience of our nation. In them we see the sins of ecological pastRested and nourished, flight to Texas forms in Nebraska

Calling on the Browns

Brown is color angling for Dick and Paul Roberts

Trout will hit anytime, say these two Sidney anglers. Spring-fed feeder streams provide the area

Dick Dougherty fishes upstream, concentrating on fast stretches

FOR MOST PEOPLE, fishing is a sport for leisure hours in late spring, summer, and early fall when the weather is clear and warm. Of course, there are those who go out on the ice during mid-winter to dangle a line through a hole, but there is yet another kind of angler.

"Trout will hit any time of the year," sums up Dick Dougherty, a big, rugged Irishman from Sidney, who knows as much about fishing as anyone. "There may be times when they hit better than others, but with the right approach and patience, you can take trout in winter or summer."

Paul Roberts, director of the Nebraska Oil and Gas Commission and also of Sidney, backs up Dick's contention. Dougherty is an inspector with the Oil Commission following a good many years in the field as a driller. But, besides their mutual concern with the oil business, the two men share an interest in fishing.

Living in the western part of the state, they are particularly interested in trout, but largemouth bass, crappie, and almost any other species except northern pike lure them to lake or streamside throughout the year. Paul is a native Nebraskan, originally from Albion, so in a way he broke Dick in on Nebraska fishing. Dick was an apt pupil, and is now a downright avid angler, so Paul is not surprised that Dick outfishes him on occasion.

One of those occasions came early last January when the two men braved (Continued on page 50)

Forts Kearny

Such notables as Buffalo Bill called second post their home

Named for colonel of note, first post dwindled only to be reborn on the banks of Platte River

IT WAS 1861 and Fort Kearny was in big trouble. The South had started something President Lincoln figured could be nipped in 90 days, but he would have to use everyone to do it. So, the Nebraska outpost was making do as best it could. The installation's commander, an ardent Southern sympathizer, took little time to decide where his allegiance lay, and headed south to become a colonel. The Union War Department, feeling that Fort Kearny's troops could best be used elsewhere, ordered the entire garrison of regulars to Fort Leavenworth. Fort Kearny even lost its artillery to the Civil War effort. Nebraska and Iowa volunteers moved into the post to keep the peace in the West, but Indians, who evidently had little respect for the citizen soldiers, began acting up. All in all, 1861 was a very bad year at Fort Kearny.

Things hadn't always been so bad, though. There was a day when the post on the Platte was indispensable. It was the guardian of travelers on the Oregon Trail and a supply depot for freighters who pushed across the Missouri River and headed west. Troops stationed there, though perhaps a bit rough, were among the best in the army. The fort was the backbone of western defenses, holding raiding hostiles at bay during the years of national expansion. Nestled in the sprawling Platte River Valley south of present-day Kearney, the fort was about as much as anyone could have wanted in a military reservation in the mid-1800's.

Actually, Fort Kearny was the second post in Nebraska to bear that name. The first was the brainchild of Colonel Steven Watts Kearny of the First U.S. Dragoons. In 1838, a betting man who wagered he could find humans other than Otoe, Pawnee, and Omaha Indians in what is now Otoe County would probably have lost. But westward movement was just a matter of time, and Colonel Kearny knew it. On April 2, he and Captain Nathan Boone authored a letter to the War Department recommending establishment of a post at the mouth of Table Creek on the Missouri River. Some said the site had been recommended by Lewis and Clark in 1804, but there is no evidence to support such a claim. But then, it takes some looking to find Washington's authorization for the project, too. It took eight years for Kearny's superiors to act. On March 6, 1846, notice was sent to proceed with establishment of the second military post west of the Missouri River.

With the go-ahead in hand, Colonel Kearny moved much faster. On May 12 he sent word that he had ordered a Lieutenant Smith and 30 dragoons of a Captain Moore's command to proceed to Table Creek. He noted that they took only 20 horses with them, since he felt more would just be in the way. Kearny and Moore stayed behind, waiting for supply boats to arrive from St. Louis. Then the two set out with the rest of the troops and a Major Wharton whom Kearny planned to put in command.

Wharton was in for a blustery time, however. First, he had a

post, but he didn't know what to call it. No one had bothered to

name the fort, so the major sent in a list of ideas. Washington

rejected them all and told the major to call it Fort Kearny after

the man whose idea had fostered the project. Secondly, most of

the men of the expedition fell ill as soon as they crossed the

Missouri. At one point, it became so bad that only one soldier

was well enough to pull guard duty. Wharton wanted out. He

beseeched the War Department to call off the project, and since

the United States had declared,war on Mexico that spring, his

recommendation did not go unheeded. On June 22, 1846, a halt

was called to the experiment and the troops were ordered to fall

back to Fort Leavenworth. With a war underway, manpower

levels throughout the nation were feeling the drain, and the First

Dragoons would be welcome at the front.

rejected them all and told the major to call it Fort Kearny after

the man whose idea had fostered the project. Secondly, most of

the men of the expedition fell ill as soon as they crossed the

Missouri. At one point, it became so bad that only one soldier

was well enough to pull guard duty. Wharton wanted out. He

beseeched the War Department to call off the project, and since

the United States had declared,war on Mexico that spring, his

recommendation did not go unheeded. On June 22, 1846, a halt

was called to the experiment and the troops were ordered to fall

back to Fort Leavenworth. With a war underway, manpower

levels throughout the nation were feeling the drain, and the First

Dragoons would be welcome at the front.

What Wharton and his men left behind on Table Creek wouldn't be much by modern standards, but in the face of all their troubles, they had done quite a bit in a short span. Though many of the buildings were not ready for occupancy, the garrison had begun a block house; the post's main fortification; a log house for officers; and a hospital. In the months to come, building would stop completely only to spring to life again later.

When the First Dragoons pulled out, custody of the buildings fell to William English of Glenwood, Iowa. He looked after them until the fall of 1847 when five companies of Missouri Volunteers under the command of Colonel L. W. Powell moved in. Before long, temporary housing disappeared and log buildings popped up while the reservation expanded. But even with the resurgence of activity and building, Fort Kearny was dying.

Despite the fracas between the United States and Mexico, people still streamed into the West. Trouble was, the troops at Fort Kearny seldom saw them. While Colonel Kearny thought the site he had chosen would be the jumping-off point for immigrants, they actually chose several spots farther south for crossing the Missouri River. About all the soldiers at Nebraska City had to do was ride herd on Otoes, keeping their thieving and drinking to a minimum. Then there were the dances across the river in Missouri, but they could hardly be called military tactics. So, Fort Kearny's abandonment was recommended. It was clear, though, that military presence beyond the Missouri River was a must, and in the fall of 1847 an exploring party was launched. They found what they were looking for. In the spring of 1848 the post was moved to the edge of the Platte River some 1 50 miles west.

When all was said and done, the actual garrison at the first Fort Kearny lasted only about a year. With the troops gone, settlers began to prey on the deserted buildings and, one by one, they disappeared. For a time, the block house, bastion of defense on the frontier, served as a cow barn for an area farmer. By 1854, only memories remained of the first Fort Kearny —civilization's second attempt at military security west of the Missouri. But, hard by the mainstream of coastal traffic, its successor on the Platte was faring much better.

Somehow it seems ironic that a regular military post in what was to become Nebraska Territory was first garrisoned by volunteers from Missouri. But that's what happened when the first post was moved to the second. Not (Continued on page 62)

Nebraska City re-creation is copy of town's first outpost

For years, only lone marker stood at site of second post

Post on Platte today is part of State Historical Park system

Despite remote location, post had its share of military pomp

Second Time Around

Dike construction is completed in 1970, enclosing a 3.4-acre area for hatching

THE TALE will begin unfolding this summer when anglers throw small northern pike they catch in Bluestem Lake back into the water, and the more they toss back the better. While fishermen will not realize the full benefit of an experiment to stock Bluestem with northerns until 1973, the number of fish they catch and then return to the water after carefully removing the hooks will give an indication of the project's success.

Built in mid-1970, a marsh at the northeast corner of Bluestem, located 10 miles south of Lincoln near Sprague, was filled to an average depth of 4 feet in February, 1971, and stocked with adult northerns. Given a month to spawn, they produced thousands of fingerlings which were released into the lake later that spring.

Jerry Morris, senior biologist with the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, spearheaded and supervised the project. Although no official survey will be taken, he will be spending a lot of time at lakeside this summer, checking to see how many of the northern yearlings are biting. They will have to be thrown back, though, because they will not be much longer than 15 inches, and the legal 34 requirement in Nebraska east of U.S. Highway 81 (excluding the Missouri River) is that northerns beat least 24 inches long before they can be kept.

In removing the hook from a northern's mouth, anglers should try to bring out the barb the way it went in. Ripping it out may cause fatal damage.

This experiment —a first in Nebraska —began eariy in 1970 when Morris visited several artificial northern-pike spawning marshes in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area. Based on the success of the Minnesota marshes, his recommendation was that one be built in southeastern Nebraska. The goal was to increase the northern population in one lake with the long-range objective of doing the same in others if the project proved successful. Although northern fingerlings were stocked directly into eastern Nebraska lakes several years earlier, populations dwindled because there was not enough spawning habitat for them to reproduce properly.

It was also discovered that fish hatched in a marsh have more chance for survival than those raised artificially in a hatchery. Natural habitat, it (Continued on page 53)

Still too small this seasons, northern pike hatched last year will be fair game in 1973

Fingerlings measured on way to lake show 3 1/2-inch growth during two months in marsh

Biologist Jerry Morris (left), project supervisor, Ross tock check conditions

SPECTRUM IN THE STREAMS

Rainbow stripe is a dominant feature giving fish its name

Closeup reveals identifying black spots of rainbow

Brown's gill extracts life-giving oxygen from water intake

Pectoral fins of brown correspond to animals' forelegs

SPRING WE ASSOCIATE with new life. That is when the gray bonds of winter break and we witness the bright spring plumage of the earth. But in late autumn, when Nebraska falls into freeze, and again in February, when the land is galvanized by winter, an unseen ritual runs through the clearest and coldest of Nebraska's streams.

Trout run then, brown and brook in fall when the days grow short, and rainbow in spring (except in Lake McConaughy, where for some inexplicable reason they run in October). Commanded by their own season, the colors of the males gaudily intensified, they obediently ascend streams to spawn, scouring their saucer-shaped nests from the sand.

Trout belong to the salmon family. They are slender fish characterized by

fine scales, naked (scaleless) heads, and bright coloration. Brown and rainbow trout

are capable of reaching a whopping, 40-pound weight under the most ideal

conditions, although even a 12-pound trout is rare in Nebraska. Limited space and

heavy fishing pressure prevent the development of such giants. Thus, a five-pounder

is considered a trophy. Trout have

always been favorites with fishermen, as shown by the estimation that

more money has been spent nationally on their propogation than on any other fish.

None of the three trout species found in Nebraska are native. The brown was

introduced to the United States from Europe late in the 19th Century. The

rainbow is native to the Pacific Coast, and the brook was brought to Nebraska from

the East Coast. (There is evidence that cutthroat trout, not presently found in

Nebraska, were present before 1900).

always been favorites with fishermen, as shown by the estimation that

more money has been spent nationally on their propogation than on any other fish.

None of the three trout species found in Nebraska are native. The brown was

introduced to the United States from Europe late in the 19th Century. The

rainbow is native to the Pacific Coast, and the brook was brought to Nebraska from

the East Coast. (There is evidence that cutthroat trout, not presently found in

Nebraska, were present before 1900).

The limited trout range in present-day Nebraska —the north-central region and the Panhandle—is due to their exacting water requirements. Trout need water that has a high oxygen content and does not become warmer than 70 degrees Fahrenheit. The brook trout, especially, is very sensitive to higher temperatures. Farming, resulting in siltation, and the removal of shade cover along streams, has degraded much trout water in Nebraska.

But where conditions are favorable, trout continue their ancient ritual. The agate-like beauty of the males at these times provides added pleasure for anglers and invites close inspection.

The three species of trout are readily distinguished from each other. The brook, very limited in Nebraska, is quickly identified by its white markings on the leading edges of the lower fins. The brown, as the name implies, is predominately olive to greenish brown. It resembles the brook except that it does not possess the mottled coloration on the dorsal fin and back.

The rainbow is greenish-blue to olive on the top of its body and silvery below, with a conspicuous horizontal red band on the side. Among larger fish the males are easily distinguished from the females by the large cartilaginous "button" on the tip of the lower jaw.

At any time, but especially when the trout are running, a close look at these living spectrums will reward and surprise —as nature always does —all those who take notice that such an assemblage of pattern and color can freely run beneath the white stance of winter. THE END

Brown's teeth, above, are larger than rainbow's. Both develop hooked jaw. Gill cover is at right

Avid anglers know a siren song sounded from icy streams

Concern for tomorrow

In their own charming way, both urban and rural kids tell grownups to clean up the earth before messing up the moon

EARLIER THIS YEAR NEBRASKAland staff members presented two films to second and third-graders at Custer Elementary School in Broken Bow and Meadow Lane Elementary School in Lincoln to discover how the children felt about the way their world is being managed. Second-graders viewed the film Cry of the Marsh, an ecological movie telling how a young duckling loses its home to progress. As more marshland is being lost to agriculture, waterfowl populations are diminishing. This film dramatizes the draining of a marsh with cranes and bulldozers, and the loss of a nest of young pheasants and ducks as vegetation is burned to prepare land for farming. Third-graders saw The Gifts, a film dealing with pollution on a nationwide scale, including a scene of blood and animal wastes being dumped from an Omaha slaughterhouse into the Missouri River. Third-graders at Axtell Elementary School also saw The Gifts. After viewing the films, each group drew their impressions and discussed their ideas as presented here.

If any one lesson can be singled out from this experience, it is the children's sincere concern for what is happening to their world, and what type of environment they, as adults, will inherit. Perhaps the answer to the environmental problems confronting us today lies in their simplistic approach. Our capitalistic drives and desires for more comforts at an ever-increasing cost to the natural world have yet to entrance them.

Another trend was obvious after visiting first a rural, then an urban classroom. Wildlife was a day-to-day experience for the children of Broken Bow but pollution was an unfamiliar concept. The reverse was evident in the Lincoln classrooms, illustrating the strong influences society exerts.

Perhaps our lesson for today, to be learned from these school children, is that we are not only exploiting natural resources for our own selfish desires, but that we're doing so at the expense of future generations. The decisions are ours, but their outcome will belong to the children of today.

Donna Pirine, Third Grade, Custer School Broken Bow

Mike Myers, Third Grade, Meadow Lane School, Lincoln

Jaime Bryant, Second Grade, Meadow Lane School, Lincoln

What's happening to our World?

NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA... Flathead Catfish

Deep pools in slow-moving rivers are home for this species. As for chameleon, habitat dictates its color

THE FLATHEAD CATFISH, Pylodictis oiivaris, has been variously known as the yellow river cat, shovelnose cat, Mississippi cat, and mud cat. It is present throughout the Mississippi River drainage system and in certain rivers which empty into the Gulf of Mexico. In Nebraska, the highest flathead populations are found in the lower reaches of the Platte, Loup, Niobrara, Republican, Missouri, and Blue rivers, as well as the Loup Power Canal.

The flathead is distinct among the other members of the catfish family, Ictaluridae, in that, except for the bullhead, it has a rather square or slightly rounded tail—not forked like those of the others. As the name implies, this fish has a large, flat mouth and eight thick whiskers, or chin barbels, and a short powerful body. Like all members of the catfish family, there are no scales, and the flathead has sharp spines on its fins for protection. Another characteristic is that the lower jaw extends beyond the upper and both jaws contain rough, pad-like areas that act as teeth. The band of teeth in the upper jaw has backward extensions.

The flathead is like the chameleon. Where it lives in the river determines its color. It can have a deep yellow belly with an olive back or a white belly mottled with browns and blacks. Regardless of what it looks like, it grows to tremendous size.

The flathead primarily inhabits large, slow-moving rivers. Deep pools with minimum currents and fairly hard or rocky bottoms are ideal. Fallen trees or other obstructions in deep holes provide excellent habitat.

Nocturnal feeders, flathead catfish characteristically move into shallow water for food. Daylight feeding is limited and restricted to deep holes or secluded areas. Vision plays only a limited role in nocturnal feeding habits, since sensory barbels and areas of skin pitted with taste buds are used to feel or smell out prey. During the day, large flatheads lie motionless on the bottom for long periods of time with their mouths wide open. Careless fish seeking a hiding place are promptly swallowed.

Insects, crayfish, molluscs, and fish provide food for the flathead. Immature aquatic insects are the most important diet items for young flatheads. Fish and crayfish are the two most important items for yearlings and adults. Originally, it was thought that this catfish was an omnivorous feeder, that is, it ate anything. Recent studies, however, have indicated that the adults feed primarily on live food.

The flathead reaches sexual maturity at the age of 4 or 5 years and at a length of 15 to 20 inches. The female requires a year longer to reach maturity. Spawning takes place during the spring, the exact time depending upon water temperature. Optimum water temperature for this species is between 65 and 70 degrees Fahrenheit. Flatheads pair off and build nests in secluded areas such as undercut river banks or holes. The eggs are laid by the female and are fertilized externally by the male. The male then carefully guards the nest. During this period the male becomes quite aggressive. The eggs begin to hatch about two weeks after fertilization. After hatching, the young form a school and remain in or near the nest for 2 or 3 weeks. After leaving the nest, the young are found mostly in shallow riffles beneath stones or other forms of cover.

The flathead is valuable to commercial fishermen. On the Missouri River, the only area where commercial fishing is allowed in Nebraska, the flathead is of major importance. It has been reported that flatheads consistently bring high prices in the fresh-fish markets of St. Louis and Memphis. Their flesh is firm and delicious, but may be somewhat coarse and oily in large specimens. Unfortunately, flatheads prefer deep, snag-filled holes and limited movement greatly decreases the volume of harvest in commercial nets.

The mere bulk of adult flatheads make them enticing targets for anglers. Fish weighing 10 to 15 pounds are not uncommon in Nebraska, and even larger specimens are creeled annually. The present hook-and-line record is 76 pounds. A 115-pounder was found in a Texas lake. Because of the flathead's nocturnal feeding habits and its method of lying motionless with open mouth, it is difficult to catch. The major prerequisite for catching a large flathead is patience.

The most popular method for harvesting flatheads is with set lines. Jug fishing, however, is also popular in the South. The common catfish "stink baits" are not productive when seeking flatheads. As has already been indicated, adults seek live fish. Successful baits used in Nebraska are 3- to 4-inch bluegill, chubs, minnows, 8-to-10-inch carp, and gizzard shad. One angler reported catching a large flathead with a 12-inch channel catfish in its stomach. The angler who wants a new experience should take his set lines and spend a night on the river. Who knows? Maybe he will catch a lunker he never thought existed. THE END

CALLING ON THE BROWNS

(Continued from page 29)near-zero weather to sample trout activity in some of the feeder steams along the North Platte River north of Sidney.

Although most open bodies of water sat like giant ice cubes around the country, spring-fed creeks like Red Willow, Nine Mile, Wild Horse, and others ran merrily, if frigidly, along their way. And the trout in them, mostly German browns, seemed receptive.

It was only a few minutes after leaving the car that the first trout was in hand. Using an ultra-light rod and a diminutive, openface reel, Dick flipped out a small spinner only 3 times before a 13-inch brown spied and seized it. Despite the cold water, the trout was plenty scrappy. While he enjoyed playing the fish, Paul was driving away to work another part of the stream, so he missed Dick's early action.

Slipping his catch off the hook, Dick found another customer several casts later. This one, however, escaped with a quick dash and a shake of his head.

"That almost looked like a rainbow instead of a brown," Dick mused, not overly upset about losing the fish. It had looked somewhat larger than his first catch-probably a 15-incher. Wading down the center of the 10-feet-wide stream, which was perhaps 16 inches deep except in the holes, Dick continued fishing his way upstream. Paul had really missed out on some fun, because within a few hundred yards from his starting point, Dick hooked 4 trout, landed 2 of them, and saw several others flash by his feet. Then action fell off, and he walked half a mile farther without a strike.

The creek looked just as good, maybe better, with more deep holes, yet there seemed to be no fish. Although Dick had hooked all of his in fairly fast water near midstream, he continued to work all parts of the narrow channel just to be sure. His luck, however, seemed to have departed with the fish.

After skimming his lure through dozens of prime-looking spots, Dick came upon a small waterfall created by a log jam and a ridge or rocks. The falls had formed a deep hole on the downstream side, and it looked like a natural haven for lazing trout. Several casts into the deepest part of the pool and retrieves back to the shallows yielded nothing, but the fifth time brought a connection.

"By golly, there's at least one nice one in there," he chuckled to himself.

The brown put on a great show. With speed and enthusiasm that Dick had not fully expected from a fish in such cold water, the trout leaped and shook and carried on. Three times he came out of the water in classic leaps. For the first time that day, Dick realized he could watch and feel the fish, but he could not hear it. When he got out of the car, he had stuffed cotton in his ears to protect them from the cold. The last time he had fished this area in winter, he had temporarily lost his hearing. He had blamed the ailment on the cold and humidity, and didn't want it to happen again.

As the latest trout tired and could be eased into shallow water, Dick scooped him up for inspection. The fish was another fine specimen, more than 13 inches long and plenty plump. After the long inactive spell, it was a welcome change.

Since that stretch of river had been covered with Paul on the upper portion, the pair met at the car and planned the next foray. Paul had come back from his segment empty handed, and was enviously surprised that Dick had encountered so much activity. Paul was also using a little spinner on an ultra-light rod that came apart in about a dozen pieces, none longer than a ballpoint pen. With the pieces spread out on the fender, it had looked as if his rod had suffered some terrible accident, but he had put the short sections together into a five-foot rod that worked like a champ.

Although the sun had come out for a while, there was plenty of snap in the air, and the inside of the car offered comparative comfort. More fishing was just a few miles away, however, as a section of Red Willow Creek looked good. Tackle was again extricated from the trunk and another quest begun. To cover as much water as possible, the two again split up as before.

They fared not too badly this time. Paul covered about half a mile of river upstream, and cashed in with three trout. He concentrated most of his efforts on the holes along the bank where the water was slower, and which are traditional trout hangouts. Paul wore only hip waders, and fished as stealthily as possible. Dick used waders that snugged up at the waist, and joked that with his stomach, he could fall over and no water could get in. He didn't worry about sloshing along, as the noise didn't seem to bother the fish. He believes that fish always lie in the water heading upstream, and noise in the water doesn't carry up to them. It seemed to work, as he caught fish ahead of him only 1 5 to 20 feet. Actually, their systems rather reflected their personalities, as Paul is quieter and more reserved than Dick, who is boisterous and more of an extrovert.

When Paul reached a big bend in the river and encountered another fisherman, he prepared to turn back. But, he delayed for a while because the show was so good. The other angler was having troubles, and it is always interesting to watch someone else in a predicament, especially when you have been in some in the past.

The angler was working a hole, but his equipment was not co-operating. The monofilament on his reel had apparently stiffened in the cold weather, for it kept popping off his spool when he opened the bail. Those funny little coils of line would come off by themselves, and it took only seconds for them to become a snarled, tangled mass of knots and loops.

During a period when no knots appeared, the hapless fellow made a wonderful cast under an overhanging tree right into a good pool. But, his luck was only momentary, as a hidden snag caught the lure and held it. So, he broke it off and fumbled around tying on another. After what must have been 5 minutes, he gnawed off the extra monofilament at the knot and moved about 20 feet to another bend in the river, cast in, and immediately lost that lure, too. Probably a bad knot.

Shaking his head partly in pity but partly in impish enjoyment, Paul retreated, appreciating his equipment more after the episode.

At about the same time Paul was watching the demonstration, Dick was having his share of good fortune. In rapid succession, he hooked four nice browns, all of them around a pound or so, and all taken from the riffles just above or below shallow, fast stretches of water. It seemed as if the fish were on the lookout for appetizers washing down to them. Dick had walked overland about half a mile or more, and was fishing his way back upstream.

The wind had been rising steadily during the afternoon, and it had clouded over. Now almost at a screeching pitch, the wind blew dust and weeds across the countryside, but the pair wanted to try one more spot just a short distance away. Both Paul and Dick were somewhat surprised not to have encountered any rainbow trout, since this species moves into feeder streams in the fall to spawn. They had caught them this far up before, perhaps five miles from the river, but they had not seen any all day this time.

Their fishing techniques may have been the reason. Most rainbows taken in January are caught on heavy line and egg bait. Both Paul and Dick, however, prefer light tackle and artificial lures. Brown trout offer a special attraction anyway, and are worth going after, they feel.

"These browns are mean critters," Dick mused as Paul joined him once again. "I think they eat a lot of rainbows. They eat almost anything else that comes along. I suppose they gobble up snails this time of year. There must not be as much food as in the summer with all the insects, but I think there are bugs around even now. I saw a trout hit something that appeared to be hatching.

Supporting Dick's contention that browns are voracious and predatory, they seemed responsive to artificial lures that day —at least for Dick. He managed to pocket his limit of seven, taken from several different locations. With Paul's three, the day's tally stood at just two under a dozen —not bad for a cool, windy day in January. And, on top of that, a few fish had hit and run, so the potential was even higher than the tally of fish in the creel.

Besides that, there are rainbows in the area which could have been taken with suitable rigging, so all-winter fishing doesn't have to be through the ice. With such streams open all winter, holding trout that are hankering for a snack, it would make an angler uneasy to be wasting his time sitting in front of the fireplace. Catching trout beats eating popcorn anytime—even in January.

Many streams emptying into the North Platte River serve as spawning waters for trout which later move down to Lake McConaughy. Special stockings have been made by the Game and Parks Commission to imprint the streams upon the newly hatched fish. It is then expected that the trout will return to the same stream when they become adults in search of spawning areas. Coho salmon are being initiated the same way, and in a few years the results could have a major influence on the fishing potential of that region.

Being stream fish by nature, and having more tolerance for warmer water, the browns stay in the streams year-round. And, they grow to good size, often three or four pounds, even up to eight or so, but they also become mighty cagey with age. Some stocking of these colorful trout is done and there is natural reproduction in many of the streams, but studies are still being made as to whether fingerlings or adult-fish releases bring the best results.