WHERE THE WEST BEGINS

NEBRASKAland

March 1972 50 cents 1CD 08615 THE HISTORY OF ARBOR DAY COLORFUL SONGS WITH WINDS CREATE GOOSE HUNTING WILL IT EVER BE THE SAME? CATCH A RECORD FISH VOL. 50 / NO. 3 / MARCH 1972 / SELLING NEBRASKA IS OUR BUSINESS

VOL. 50 / NO. 3 / MARCH 1972 / SELLING NEBRASKA IS OUR BUSINESS

Under Sail No sputtering engines disturb the silence of sailing. Man hears his environment as never before, and his surroundings smile upon him

Passion for Tradition A few idealists still cling to old standards, worshipping goose-hunting traditions. The Goldens of North Platte are such sportsmen

Songs of the Wind The wind is the oldest poet. He delivers the seasons, then whispers through the grass, gently scattering the chorus of springtime geese

Story in the Snow From the safety of the trees, what must have been a big deer had walked out into the clearing. His tracks were evenly spaced in a straight line

Boxed numbers denote approximate location of this month's features.

Land of the Prairie Pioneer

A memorable way to relive the past!Great family entertainment on 265 acres. See the Main Building on the Island, Outdoor museum with 57 buildings, Henry Fonda's birthplace, extensive farm machinery collection. Recreation and camping facilities adjacent. Summer hours: 9-7 Monday-Saturday, 1-7 Sunday. Admission: $1 Adult, 50 Student, 35 Children. Write for complete brochure and special tours:

Stuhr Museum / Box 637 / Grand Island, Nebraska 68801Speak Up

NEBRASKAland invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to SPEAK UP. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters. — Editor.

PICKLING PLEASE- I would like very much to have the fish-pickling recipe mentioned in Speak Up in the January 1972 issue of NEBRASKAland." - Orvin Gold, Table Rock.

A copy of the recipe has been sent to Mr. Gold. For others who might be interested, instructions follow: Cut fish in pieces and soak in half-vinegar and half-water overnight. Then, combine three cups of vinegar and one cup of water, add a sliced lemon, allspice, mustard seed, pepper and salt, and bring the mixture to a boil. Put in three or four pieces of fish and let them heat through thoroughly, but not until well done. Place fish in jar and slice an onion over it. Then add more fish and repeat, pouring boiling vinegar over the meat.

Skin should not be removed, and spices and onions may be added to taste. — Editor.

THANK YOU- I wish to express my personal appreciation for the Reverend Edward R. Baack's article, Chrismons, in the December issue. Christ has become all but lost in that festive month, and it was even hard this winter to find Christmas music, let alone the traditional carols, over Minneapolis radio stations.

"Then, the December issue of NEBRASKAland arrived and there was a refreshing Christian article of Christmas. Thank you for not forgetting and making this inclusion."—Charles Phenicie, Dickfield, Minnesota.

COMMENDATION-"! just had to write to commend you on your fine December issue. NEBRASKAland has remembered the ladies this holiday season. You have remembered the true meaning of Christmas with your fine article on Chrismons. Our ladies made them for our church last year.

"I also enjoyed the information on geneology and the Indian crafts in Premise for Survival." —Mrs. Alvin Bohling, Auburn.

BETTER LATE THAN-"Enclosed is a photograph of my wife and her first deer, taken in 1971. At age 68, she decided to try for a deer, and downed this one with a 150-yard heart shot!"- Nick Carter, McCook.

Mrs. Carter and First Deer

WRONG SALT-"One problem Mr. Minser (Speak Up, January 1972) had is that he may have used the wrong salt. Place a spoonful of pickling salt in a glass of warm water and let it stand overnight. At the same time, do likewise with ordinary salt. The next morning, you will find that the pickling salt is almost all dissolved. The ordinary salt will be only about 90 percent dissolved. The reason is that pickling salt is natural, and store-bought salt is processed."—Hugo E. Schmidt, Wichita, Kansas.

HARD TO BELIEVE- Regarding the article, Conflict, in the January 1972 issue of NEBRASKAland, I find it hard to believe that the Norden Dam project or the Mid-State project are needed. My family and I visited the Niobrara River this past summer and took a liking to this unique (Continued on page 8)

A Case for Cover!

HABITAT CONSISTS OF: Cover, Food, Water, and Living Space, which are provided by Sunlight, Soil, Rainfall, and Plants. NATURE did a fine job of providing HABITAT until man began needing room for "improvements," such as Homes, Factories, Highways, Cities, Golf Courses, Airports, Pastures, and Crop Fields.

WHAT CAN YOU DO?Join forces with your buddies or act on your own, but do it now. The cover you save today will be more important than what you build next year.

Unless the cry is raised to stop it, thousands of acres of cover, road-sides for example, will be burned, sprayed, or mowed this year. Much of this destruction serves no real purpose.

You can also help a farmer return some land to permanent cover.

You can speak up in favor of programs to retire unneeded agricultural land, like the soil bank program.

Provide Habitat... Places Where Wildlife Lives Join the ACRES FOR WILDLIFE PROGRAM For suggestions on how to take action, Write to: Nebraska Game and ParksCommission P.O. Box 30370 2200 North 33rd Street Lincoln, Nebraska 68503

We've been doing a lot of things to make you want to fly Frontier. Big things, like Snow Club Service on many flights. Better schedules. And being on time. Little things like warm hellos to go with your Irish coffee. Fly Frontier. And see what you've been missing.

We'll help make arrangements for you. A rented car. A lift on a ski bus. Or, a room at a ski lodge. Just ask.

In-flight, up-to-the minute area weather reports and snow conditions.

Your skis go in a speical protective bag. Safe and sound...and free.

Frontier's Snow Club Service will fly you to, or near, more snow spots than any other airline.

Thirty-two great skis areas in Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, New Mexico, Montana and Arizona. Places like Aspen, Vail, Taos, Jacksons Hole and on and on.

Our Sever-Day-A-Week Family Plan and Group Fares are real money savers.

Take advantage of our sepcial ski tour fares. Or buy a standby ticket. We'll get you or your whole family to the slopes a little richer.

Call any Travel Agent or Frontier Airlines.

If you haven't been flying Frontier to where the snow flies, look what you've been missing.For the record Ecology- A Wild Idea

Ecology: A Wild Idea! That is the theme selected for Nationa Wildlife Week, March 19 through 25. Give it some thought. The connotations are broad indeed-wild because wild things are a part of ecology and a part of life as we know it, or wild to many, perhaps, because few concepts such as this have caught the imagination of so many people or challenged so many status-quo programs, actions, and values.

We live in a period of social unrest, particularly evident among young adults who are questioning the ''establishment" as never before because they are vitally concerned about the social, cultural, and natural environment they will inherit. They care about environmental problems which will continue destroying the natural environment. Although these concerns are more loudly proclaimed by the young, they are not youth's exclusive domain. Adults, including many in the establishment, are also concerned.

Values are changing, and perhaps it is not so wild to imagine that we can correct the mistakes that have been made through the years. The coyote and prairie dog of yesteryear were appreciated very little. And yet, today, these two and many other wildlife species are valued much more than their counterparts of pioneer days when the primary concern was to conquer the natural environment.

Today our concern is for restoration, perpetuation, and husbandry of a healthy, natural environment which is capable of sustaining desirable populations of all forms of wild animals. Why? A healthy, natural environment, including all wild creatures, contributes to our quality of life and is essential for our own survival. An environment which does not support diversified wildlife cannot provide the ecological support which is necessary for the meaningful survival of man.

"Ecology" was not a part of our common vocabulary a few short years ago. Today, however, it is a household word. It designates the science which deals with the inter-relationships of organisms and their environments. It provides the foundation for modern-day management of renewable natural resources, including fish and wildlife. The scientific study itself is the province of the professional ecologist, but each of us must practice the principles of ecology if the science is to make its greatest contribution to society. We must develop our ecological conscience. We must be able to recognize the effect of our individual and collective actions on the environment. Conflicts, both personal and public, will arise, but we must be able to resolve these conflicts in ways which will best serve the interests of the world in which we live.

Ecology: A Wild Idea? Perhaps not. Any society which can bring species such as the whooping crane, the trumpeter swan, and the buffalo back from the brink of extinction has a lot going for itself. But we must not relax, not until each one of us is willing to help lick the problems confronting us.

There is no better time than National Wildlife Week to reaf firm our stand, to strengthen our goals, and to plan for the years ahead.

How will you Celebrate National Wildlife Week?

March 19 to 25 has been set aside to recognize established goals for preserving natural habitat and improving the quality of man's enviroment.

What will be your personal commitment?

Write for information: National Wildelife week Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, P.O. Box 30370 Lincoln, Nebraska 68503Ecology for tomorrow's sake

Speak Up

(Continued from page 5)environment. It was wild and beautiful, and I would be saddened to hear that it had been covered by water.

'That part of our state isn't, and never has been, farming country, and there would be little to gain by putting in an irrigation reservoir. We certainly don't need the reservoir to attract attention to the area's recreational potential. With a little more publicity for its unique ecology, there would be an increase in visitors. I want to be able to go back and take a canoe float trip down a portion of the Niobrara, and would not be much impressed by a man-made lake after knowing what the area had been/' —David Hohbein, Tobias.

APOLOGIES-"In the February issue, two photos used in the Phenomenon of Migration color feature were not credited. Both were the property of Dr. Paul A. Johnsgard, Zoology Department, University of Nebraska. We hope Dr. Johnsgard will accept our heartiest apologies. —Editor.

GOOD JOB-"I want to thank you for the wonderful Article pertaining to crafts Necessity To Novelty, December 1971. I know that Tom Jacobs, broom maker; Maggie Benson, loom operator; and Lois Nelson, spinning wheel operator; enjoyed the article." -Harold Warp, Chicago, Illinois.

OLD FRIEND - I have enjoyed NEBRASKAland for many years, especially since I retired 12 years ago. The picture of an old neighbor of mine on page 46 (Notes on Nebraska Fauna) in the March 1971 issue was very lifelike and accurate. But I have never heard the coyote called either a 'yodle dog' or 'Ki-O-Tee'. I believe this item warrants some further discussion. I have a great deal of respect for a healthy coyote, and don't want to be guilty of calling him some strange name."—Alf Reslock, Omaha.

Both alternate names for the coyote were intended as explanation. The former is a dialectic pronunciation common to many westerners, and the latter was a pronunciation guide. We are sorry if either of the usages caused confusion on the part of our readers, and welcome comment on any such misunderstandings in the future. — Editor

NEBRASKA CITY

where there's something doing every month of the year!

A Flood of Calls

Despite rising water, Mrs. Lothrop insists on staying at her switchboard.

LIFE AS A small-town telephone operator in 1920 was usually pretty routine —a matter of knowing everyone in the area and keeping tabs on people's calls. Interesting calls to faraway places were rare in a quiet community like Homer with a population of less than 400 people.

Mrs. Mildred Lothrop was chief operator in Homer back in 1920, and her residence in a small, wooden, downtown structure was also the telephone office. So, it was natural that she received the distress call at 2 a.m. that May 31. The frantic caller may have had to repeat parts of his message due to his own excitement, but a sleepy Mrs. Lothrop got the idea.

Homer would soon be inundated by raging floodwaters pouring down Omaha Creek on the heels of a cloudburst. Well over four inches of rain, possibly closer to six inches, fell in a matter of about two hours over a wide area, including Walthill and Hubbard. With no place to go but downhill, the water covered the valley. The earth was saturated as the area had suffered a minor flood just weeks before, but this one would be much worse —the worst in the community's history.

Quickly responding to the approach of peril, Mrs. Lothrop went to work. Sending the youngest of her five sons out to sound the fire alarm, she began ringing up all subscribers in the area. Between outgoing calls, she answered those coming in from people inquiring about the fire alarm. As the town stirred into activity, she urged rescue crews out to warn those people without phones.

Eventually, water rose to a depth of 8 feet in town, washing about 20 homes off their foundations and demolishing some, flooding all banks and business places, drowning many cattle, ripping out railroad tracks, and destroying much other property. Around the middle of the next morning the water began to recede, but it was a long time before any semblance of order was restored in the uprooted community. Damage ran high, affecting almost everyone in town and the surrounding area. People came from all over the county to help, and hundreds of workmen were trucked in from Sioux City to help clean up. But no lives were lost due in large part to the early warning of the fire bell and the phone alert by Mrs. Lothrop.

Homer's streets were already under three feet of water and the level was rising quickly. Soon the main part of town was under several feet of muddy, roiling, destructive current, with still no end in sight.

Sending four of her children to safety, Mrs. Lothrop insisted upon remaining at her switchboard to handle messages. Due to the earlier flood, she found it necessary to contact many people twice to impress upon them the seriousness of the new threat.

Harried townspeople, despite their own worries, tried to get the dedicated woman to leave the endangered building. Among them was the mayor. But Mrs. Lothrop continued her vigil, placing and answering calls until, at last her switchboard went dead.

Then, with water swirling up to her shoulders, she and one of her sons who had remained with her, struggled through the debris-laden torrent to a nearby store where they climbed to safety on the second floor.

For her valiant service to the community, Mrs. Lothrop was later named winner of the gold medal award and received $1,000 from the Theodore Vail Memorial Fund. The fund was established in 1920 as a means of recognizing public service by employees of the Northwestern Bell System.

Mrs. Lothrop's heroic efforts did not end with that one deed, however. She was again on hand to lend invaluable assistance on June 3, 1940, when a similar flood struck Homer. With the telephone office then located on the second floor of a brick building, she was able to perform a more organized rescue program. She called fire and police crews from neighboring communities, dispatched rescue boats which were brought to her office window, and served as a co-ordinator while rushing water damaged or destroyed most of the homes and businesses in Homer.

Again, she remained at her post even though water rose to within a few feet of the second floor. Her efforts were credited with saving many lives during both disasters, and she earned immeasurable gratitude from area residents because of her concern for their welfare. THE END

Get aboard Kawasaki's all new Mach II, the 350cc, 3-cylinder TriStar from Kawasaki's galaxy of superstars for 1972. Then sit back and hang on while the Mach II happens to you! Outperforms any other 350cc motorcycle made, and most 500cc. Great acceleration, 45 hp, top speed over 100 mph. The styling is unique, with striking spoiler design of seat and rear section. It's tomorrow's machine, built for today's moving generation.

Mach II —first supermachine in its class. First in power. First in speed and acceleration. And first in the race for space. Take-off time is now. See Mach II now. Then join the set.

•Kawasaki launches another first: the TriStar Triple 350 •45hp-maximum thrust for its class •Turbine smooth —with rocket thrust acceleration year of the KawasakiHOW TO: Make a Deerskin Vest

A stitch in time may save nine, but a patch here and there can be added with ingenuity to make attractive garmentsBITS AND PIECES do not make a whole, unless you happen to be Mrs. William Rochford of rural Kearney. For the past few years, she has performed the magic of fashioning custom-quality leather goods from furriers' scraps. With ingenuity and a touch of Scottish frugality, she has every member of her family decked out in patchwork leather that would make many a garment designer green with envy. A seasoned seamstress with 13 years of experience teaching young 4-Hers the fading art of fashioning their own clothes, Mrs. Rochford believes that most tailors can stitch up a patchwork garment with only a bit of patience and a sewing machine. Starting with a basic item like a vest eliminates problems with collars, sleeves, and zippers. Here are her tips for would-be-tailors on making a patchwork vest.

Most required materials can be obtained from a local five-and-dime store. Finding tanned, scrap, deer hide, though, may require a bit more searching. A trip to the local furrier or tanning plant will usually produce a low-cost, abundant supply of oddly shaped scraps. If scraps are not available, a full deerskin can be cut into unusual and interesting shapes.

Tanned scraps, interfacing; lining material, and sewing supplies are the basic components

This unique and attractive patchwork vest is one of many garments that can be made

Newspaper patterns are traced into interlacing

A wide zigzag stitch is used to sew patches onto the interfacing

After leather patchwork covers material, trim away any excess

Mrs. Rochford uses a zigzag stitch to join the lining and patchwork

The finished vest is not only attractive but economical, too

Other basic materials needed for the vest include several yards of interfacing, lining, and a strong polyester thread. If buttons or ties are to be added, appropriate materials for them will also be needed. Required equipment includes a sewing machine, pins, and scissors.

A bit of a traditonalist, Mrs. Rochford likes to start her cakes and her coats from scratch. For the vest pattern, she pins newspaper to an old shirt and cuts the form. The pattern is a three-piece affair. The back covers everything from the shoulder seams down and from the side seams back. The left and right front pieces cover from the shoulder seams down and from the side seams around to the buttons. For the less adventuresome, storebought patterns are available.

After the pieces are cut, pin them to the interfacing and trace the pattern onto it. Turning the interfacing over, copy the pattern on the reverse side. This will show where to cut excess material from the other side of the interfacing when leather patches cover the first line.

Now patch the leather pieces together. Patches usually need some preliminary trimming and shaping, and imagination is the only limit to the patterns and shapes. All torn, scarred, or frayed pieces should be trimmed. Begin with 2 pieces of leather on 1 end of the interfacing. It may be convenient to anchor 1 piece with straight pins. Pinholes can later be rubbed out. Place the 2 edges of leather flush and check to see that they will fit exactly for the full length of their union. With the sewing machine set on wide zigzag for about 15 stitches per inch, run a seam up the union of the 2 pieces, keeping them flush. When the end is reached, break off the thread on the underside of the interfacing, leaving a long piece trailing.

When the interfacing is entirely covered with a patchwork of leather, turn it over and sew with a straight stitch along the pattern line, then carefully trim the excess off along the line that marks the border. Do the same with the other two pieces, and the most difficult part of the vest is done.

Join the shoulder seams and the underarm seams. To accomplish this, lay together the two edges that will be the seam, leather to leather, and sew them together a quarter of an inch from the edge. After the seam is sewn, flop the two pieces right side out and work the seam down flat with the fingers. After the two shoulder seams and the two underarm seams are joined, the vest should be almost in finished form.

Cut the lining from the desired material according to the same pattern. Mrs. Rochford cuts hers from the fleecy lining of an old jacket. Seam the lining pieces together in the same way as the leather interfacing patchwork.

Now sew the lining to the vest. With the outside of the leather lying flat against the front of the lining, run a seam that unites the two along the entire length. The lining and the leather will, in effect, be inverted while this seam is sewn. Invert the two segments and the leather will be on the outside and the fleece lining on the inside. Press this seam flat with your fingers and tack the lining to the leather from the inside to make the edge lie flat.

The next task is to edge around the arm holes. Here Mrs. Rochford simply folds the lining and the leather inward and anchors the fold with a decorative, zigzag stitch.

The edge along the bottom is handled much the same way. Fold the lining and leather in about five-eighths of an inch and run a zigzag stitch along the entire length.

The vest is essentially done at this point uniess buttons or pockets are to be added. Buttons and holes are added in the traditional manner but the density of the stitches around the button hole should be loose because threads too close together will sometimes cut the leather.

Mrs. Rochford has not stopped with just vests but has made jackets and gun cases with zippers from the same basic patchwork idea. The possibilities are unlimited. Her newest project is a handbag for her daughter.

While the garments can be cleaned commercially much the same as suede jackets, Mrs. Rochford has found that the leather can be cleaned and revived by using a warm solution of biodegradable cleaning solvent and a rough cloth. She then rinses the leather with clear water and dries it with a towel. When the leather dries it will be stiff but working it with the hands will again make it pliable.

Mrs. Rochford estimates that the full jacket can be made for less than $10. A commercial jacket of comparable quality would run closer to $100. The gun case was created for around $8, and the vest for less than $6.

A stitch in time may save nine but for Mrs. Rochford a patch here and there saves not only dollars, but also a time-honored art. THE END

CONGRESS INN

One of the Capital City's finest Motels Deluxe units Sample room Swimming pool Television Room phones Restaurant and Lounge Meeting and Banquet Rooms 2001 West "O" St. Lincoln, Nebraska 68528 Call 477-4488 NEBRASKAland Calendar of color $1 12 Beautiful pictures grace each month, plus: • Sample Sunrise-Sunset Schedules • Hunting and Fishing Information • Duck Identification Guide • Space for Reminders • Outdoor Events • Moon Phases • Five-Year Calendar ONLY plus sales tax $1 Please send orders to: Calendar of Color P.O. Box 30370 Lincoln, Nebr. 68503 Enclosed is a check/money order for $. for calendars. This (quantity) includes sales tax on all calendars sent to Nebraska addresses. Name Street Address City State Zip

STORY IN THE SNOW

Complex web of trails in powdery white becomes a tale of life in wintery world when its mysteries are followed to sourceTracks in snow may lead to a majestic find

CAUTIOUSLY, I moved toward the sound of the nervously pawing deer. All morning long I had been tracking this crafty critter. Soon, hopefully, I would catch a glimpse of him. I assumed it was a wise old buck I was following, for the tracks were large and deep. Crisscrossing his were the imprints of at least two other deer, but I wasn't sure if all were traveling together. Now I would find out, for the sounds were but a few yards away — just beyond some heavy brush. I paused and thought about the events which had brought me to this point.

The challenge which had been given me was to see if I could find the tracks of a deer, follow them, and move in close enough for a good look, maybe even a photograph. Of course the sleuthing in the snow that I would have to do is old hat for any experienced hunter. But the same techniques which the nimrod uses, apply to whoever chooses to pursue game, regardless of their purpose. As a matter of fact, many families are now going afield in winter —to track and maybe see a fox, a raccoon, or a deer. But even though snow tracking is an ideal family activity, this was going to be my own personal adventure.

All night long it had snowed. Wet, sticky gobs of white stuff clung to every twig and branch, to every piece of fencing, to anything which offered a resting place for the heavy flakes. Early light revealed a winter fairyland in ice. Several inches of snow had painted a scene rivaling that on any Christmas card. Even though winter's official beginning was still a month away, the air was cold, hinting of harsher days to come. With the temperature around the freezing mark, I made sure I was adequately prepared with longjohns, lots of layers of clothing, and my trusty knit cap.

I began my search in wooded bottomland belonging to a farmer friend in south-central Nebraska. If all you want to do is hike, it's the easiest thing in the world to find a cooperative landowner. As I first started to walk through the snow, I realized it was ideal for tracking —not too wet and not too much of it, just a couple of inches.

I found what I was looking for, deer tracks, along the edge of the woods. Such areas between woodlands and open fields are often most productive for finding wildlife of all kinds. The signs I found there told a story.

Under a large tree, something had been rooting through the snow. Apparently two, maybe three deer had been looking for a bite to eat. Then I spotted the larger tracks. From the safety of the trees, what must have been a pretty big deer had walked out into the clearing, perhaps to check on some tastier-looking shrubs. His cloven tracks were evenly spaced and formed a straight line, the hind hooves always falling right where those in front had been. About 40 yards out he had stopped.

Certainly the best time to look for tracks is soon after a snowfall. That way all of them are fresh. Several days afterwards, it becomes harder to tell if the animal has just passed that way or if it was there three days ago.

All the while I followed his tracks, I imagined how he would look, and guessed how big he might be. Then the picture changed. The next prints were all four together, then all four together again, back'toward the trees.

The deer's casual stroll had been interrupted by something, for he had stopped abruptly, then bounded back to the protective woods. Here, then, was my challenge. I would have to find out if this deer was really the handsome buck I imagined him to be.

I wondered how much of a head start my quarry had. I knew it couldn't be much, since the snow had stopped falling only a few hours (Continued on page 55)

Area where woods and fields join is ideal for finding the initial trails

Songs of the Wind

Acknowledge the wind, the oldest poet, the maker of images...Because I deliver the seasons upon you and give the skeleton grass familiar songs and wires, sand, and windmills various voices, you are mindful of me, knowing by heart the dirge of the frozen land; you wait the sudden chorus of geese and new songs I scatter with the spring.

Rejoice in the cycles of life. With them I construct the lyrics of change, blossom to seed, seedling to chaff, the hawk in his chase, all blowing by. In such metaphors as these are you discovered, growing old. You listen harder.

Sand against tin is a ceaseless song, small sounds children never hear.

You have always loved my many moods of loud storm and bright days, delighting in the glad noise of wind put to purpose.

Or the roar you think is freedom which the willow bears on mindless afternoons.

Title Bouts

One that got away may make for exciting listening, but it's record catches anglers take home that are real storymakes

ONE COULDN'T have asked for a more perfect day. It promised to be bright and sunny with only a hint of breeze for opening day of the sagging season. Fall (1971) had been pleasant, and Octber 1 found three long-time fishing firends together once again

After loading gear into their boat just as dawn broke, Vincent Prazak, Albin Stodola, and Louis Psotta headed for deep water. They were in the tailwaters of Lewis and Clark Lake in northeast Nebraska, and were going after spoonbills. Action came regularly for this trio of Clarkson anglers, who try to get out fishing at least once a week.

But something unusal was about to happen. Prazak was using 50-pound-test line with a hefty lead weight just above fishimitation lure. A largue, ocean-type casting reel allowed him plenty of footage for the long-distance retrieve they often made.

Shortly before noon 60-year-old Prazak felt a soild connection. With success running high, the latest fish on his line created little excitement in the boat, but the battle continued longer than usual. The critter seemed full of fight and didn't want to move toward the boat. It pulled and burrowed and shook the line, and Prazak figured it would not pay to force its hand. More than 15 minutes passed and still the fight went on.

Snagging is a tricky sport. Normally, only catfish and spoonbills are caught since the hook is dragged along the bottom or just above. Once in a while another species like walleye is taken, but that is rare. The bottom dwellers, those which siphon food from the mud, are major targets.

In the murky depths of the Missouri River, fish feed by sound or feel more than sight. A snagging hook, however, does not need to attract a fish. It can grab from behind or from the side without the fish having any appetite at all. Sangging is hard wor, though, and requires strong arms and back to stand hours of labor. Almost half an hour had elapsed since the strike, but now the fish was coming in towards the boat. Finally it was pulled up over the side with a net. Lo and behold, it was no paddlefish or catfish. In fact the fish had not been snagged at all. This time, the fish had fallen for the funny-looking hook. The mevement of tackle through the water had attracted its attention, and it had just glommed on. I langing on the line was a drum - a great, big one. It must have pushed the 30-pound mark soeaking wet. Not wanting to break their run of luck, the three men continued (Continued on page 62)

Average in apperance, Morton had an uncommon dream about his trees

On the day they were wed, Morton and his wife, Caroline loy French, left Michigan for Nebraska

Gospel of Trees

Greening of America fell to Nebraska editor and statesman 100 years ago. Now, J. Sterling Morton's Arbor Day is entering a new dimension

by Elizabeth HuffYears were good to Morton. His cabinet post was state's first

Trees Nebraska Citian planted tower over statue at his home

NO, THE GUN did not win the West, popular as that legend has become. Two major forces brought civilization to the vast frontier —the cow and the plow. Sheer force of numbers tamed the plains as more and more ranchers and sodbusters planted their roots. As those roots took hold and probed deep into the prairie sod, pioneers were acutely aware of the primitive nature of their surroundings.

Perhaps no man sensed the bleakness of the seemingly limitless expanse of treeless plains more than did one from Detroit by the name of J. Sterling Morton. This singular individual did more to bring beauty to the raw wilderness than any other.

Johnny Appleseed of the West, Morton gave Nebraska and the world an idea that fired the imaginations of those pioneer settlers a hundred years ago and all generations since.

"Plant trees/' he said, and through his efforts, Arbor Day came into being. Today it is a legal holiday in four states —Nebraska, Florida, Utah, and Wyoming. And, in this the centennial year of its founding, Arbor Day is observed in all states except Alaska and in countries through-out the world.

In an address delivered at the University of Nebraska on Arbor Day in 1887, Morton commented: "Arbor Day — Nebraska's own home-invented and home-instituted anniversary-which has already transplanted itself to nearly every state in the American Union and even been adopted in foreign lands is not like any other holidays. Each of those reposes on the past, while Arbor Day proposes for the future."

An inspired idea, Arbor Day did not come about on the spur of the moment. Morton preached his gospel of tree planting for many years.

An average man as far as looks go, Morton was born

on April 22, 1832, in Adams, New York. His family moved

to Michigan during his youth and there he attended university

at Ann Arbor, completing his degree at Union College

in New York. At the age of 22, he married the sweetheart

of his teens, Caroline Joy French. On their wedding

day, October 30, 1854, the young couple left Detroit to

start their life in a new land —Nebraska Territory.

day, October 30, 1854, the young couple left Detroit to

start their life in a new land —Nebraska Territory.

The newlyweds first settled in Bellevue, but within a year they moved to Nebraska City where they began building their life, one that in time would have an impact noted around the world. The Mortons' first land holdings comprised a pre-emption of 160 acres filed in 1855. They selected as the site of their home one of the highest locations in the area that gave them not only a view of the fledgling community, but the Missouri River as well. There they built a 4-room house that over the years became the 52-room colonial mansion known as Arbor Lodge.

On arriving in Nebraska City, Morton made a contract with the townsite company for 5 town shares and 70 lots on the townsite. Being a journalist by profession, he became editor that year of Nebraska's first newspaper, the Nebraska City News. And, he received the grand sum of $50 a month as editor, a post he held for about a year. Morton resumed the editor's position for a time in 1857 and did editorial work for the News at intervals until 1877.

Barely had the young couple settled into their new life when the first of their four sons, Joy, appeared on the scene. And, in that same year, 1855, the 23-year-old Morton was elected to the Territorial Legislature. Again a candidate in 1856, he was defeated by just 18 votes.

In 1857, he was reinstated as a member of the Legislature and his second son, Paul, was born. A year later, his third son, Mark, appeared on the scene. The Democratic nominee for Congress in 1860, Morton apparently won the seat by 14 votes. However, his opponent was certified as the winner, evidently because the Democrats were in the minority in Congress and secession was imminent.

Both Morton and his wife loved nature and soon adorned their new home with a variety of trees, shrubs, and flowers. By 1858, they had started an orchard along with their other plantings, making Arbor Lodge one of the earliest attempts at home landscaping in Nebraska. Zealous in his advocation of tree planting, Morton stumped for his program through his writings and speeches.

A man of great ego, Morton possessed that quality that is today called "charisma." He was also a determined man with talents and dedication to achieve his goals.

Now a State Historical Park, Arbor Lodge has grown from 4 to 52 rooms. Each is jammed with memorabilia of triumphs a way of life attuned to the planting of trees can bring

He urged all individuals and organizations to plant trees not only for practical reasons, but to commemorate visits by dignitaries, special events, and memorials. It was but a prelude of things to come.

In 1858, Morton was appointed Territorial Secretary and, upon the resignation of Governor Richardson, became acting Governor. In this position, Morton took advantage of the opportunity to stress the importance of agriculture and the value of rural life. At a meeting in Omaha that year, a Board of Agriculture was formed, with Robert W. Furnas, a Brownville orchardist, as president. In his speech at the first Territorial Fair held in Nebraska City in 1859, Morton urged the farmers in his audience "to be proud of their calling, for in it there was no possibility of guile or fraud." Later, the State Horticultural Society was organized during the third State Fair held in Nebraska City in 1869.

Morton's fourth son, Carl, was born in 1865, and the following year, Morton was defeated in his bid for governor by David Butler. Undaunted, he continued his campaign for trees. The time was almost ripe.

In 1871, Morton was appointed by the State Horticultural Society to write and publish an address to the people of Nebraska, setting forth all important facts relative to fruit growing in the state. He closed the address with a comment that has been quoted and misquoted throughout the years since:

"There is beauty in a well-ordered orchard, which is a joy forever. Orchards are missionaries of culture and refinement. If every farmer in Nebraska will plant out and cultivate an orchard and a flower garden, together with a few forest trees, this will become mentally and morally the best agricultural state in the Union."

The stage was set, and at the annual meeting of the State Horticultural Society in Lincoln on January 4, 1872, Morton read his famed "fruit address." That same day, he presented his Arbor Day resolution to the State Board of Agriculture. The board adopted it, and prizes were offered to the counties and individuals who planted properly the largest number of trees on that first Arbor Day, April 10, 1872. Early records claim that "somewhat over a million trees were planted" that day as a result.

Two years later, Governor Furnas issued the first Arbor Day proclamation, officially recognizing the second Wednesday in April as Arbor Day. Finally, in 1855, the Legislature declared it a legal holiday and made Morton's birthday, April 22, the official date.

Nebraskans were so caught up in the tree-planting fever that even prior to the action by the Board of Agriculture or the governor, the Legislature came up with a special inducement for settlers to plant trees. It passed an act which granted tax exemptions of $ 100 worth of property for every acre of forest trees planted. Money being scarce, settlers jumped at the chance to pay their taxes with trees planted on theirown claims. While itseemed likeagood ideaatthe time, a flaw soon became apparent. As a result of the law, nearly all claims had enough trees growing on them to exempt the owner from paying any taxes at all. So little money came into the state treasury that there was not enough to pay expenses and the state was compelled to borrow. The law was repealed in 1877.

Throughout the years, until her death on June 29, 1881, Caroline Morton bolstered her husband's efforts. She beautified their home and raised their sons, instilling in them a love for nature. They would spend days in the woods together, even giving pet names to trees to commemorate familiar household events. A skilled artist, she worked to capture the joy of life around her with hand and paint. And, her guiding hand was evident in the early remodelings of Arbor Lodge in 1871 and 1878. The last changes in the mansion were made by son, Joy. In 1922, he gave the Lodge to the state as a park.

Continually in and out of politics, Morton ran for Governor again in 1882, 1884, and 1892. Then in 1893, he became the first Nebraskan to hold a cabinet post, when President Grover Cleveland appointed him Secretary of Agriculture. In his Arbor Day address in Washington, D.C., in 1894, Morton closed his remarks with an enduring quote:

"So, every man, woman and child, who plants trees shall be able to say on coming as I have come toward the evening of life, in all sincerity and truth: 'If you seek my monument, look around you'."

This year, as Nebraskans observe the centennial of that first Arbor Day, they, too, look forward to the future. Not only will there be the special observances at Nebraska City, where it all began, but a non-profit foundation, the Arbor Day Foundation, has been organized to carry on the traditions that Morton began. What better monument could any man ask?

Mexican Leon

Nebraska's wandering vaquero has been dead for a century, but his troubles are far from over. Seems every time he settles down, he won't stay put

ON THE OPEN frontier, the gun was law. Few men, after coming out on the wrong end of a .45-caliber verdict, appealed to higher authority. In the squeeze of a trigger, gunmen blasted out their own brand of justice and it was final. Putting an adversary down, however, was only part of the problem in at least one instance. Keeping him there was another matter.

The year was 1876, and things were rough in Texas. The cattle business was ebbing for Print, Bob, and Ira Olive. Tough characters were muscling in on their markets and lead poisoning was a common malady with everyone concerned. There was an out, however. Gold had been discovered in the Black Hills of South Dakota, drawing dust diggers like flies to honey. Slaving over a hot claim all day left the men hungry enough to eat their shovels. Instead, they devoured beef as fast as it could be acquired. Then there was the Indian situation. Northern reservations were crying for meat as more and more Indians were moved in. All in all, it was a seller's market for the Olives. All they had to do was get their longhorns to that market.

Who came up with the trail drive solution first isn't clear. The point, though, is that Ira and Print agreed that taking the cattle north could turn'a handsome profit. Bob wouldn't hear of it. He had spent his entire life in the Lone Star state, and he wasn't about to move. Hours of hard sell proved useless and, almost in desperation, Print announced he and Ira would make the drive alone. Besides, there were the Texas holdings to look after. Bob could manage them.

It was spring before the Olive brothers began pushing north. How many head they had in tow is unknown. But chances are there were quite a few, because they headed for Ogallala and the railhead, a point usually reserved for large consignments.

Other than eating dust day after day on the long trail, things went smoothly. Through Texas and Oklahoma, the drovers put out a full day's work for a full day's pay. Even when Print was called back to Texas because Bob was having trouble with the opposition, everything went like clockwork. Ira kept the beef on the trail and the men in the saddle. Still, as days wore into weeks and weeks into months, even Olive, never a timid soul, became irritable. And, as the herd moved into southwestern Nebraska, even the little things in life were cause for heated dispute.

Evening was coming on as the Olive herd moved into what is now the Haigler Parks area of Nebraska. Trail Canyon, sometimes called Corral or Sand Canyon, was a convenient place to bed the cattle for the night. A box with only one entrance and exit, the canyon was ideal for transient drovers and their charges. Consequently, Ira figured it would make a good stopping place. Wranglers hazed the cattle into the natural corral and began making camp. It was common practice to ride night herd over trail cattle. But whether that was what Ira had in mind or not is speculative Some said he wanted a rider near the mouth of the canyon to make sure none of the steers knocked off their horns on the way out. At any rate, he stationed a vaquero, Mexican Leon, near the canyon entrance.

As they had been throughout the drive, things were peaceful that night. It was only three days, at the most, to Ogallala and payday, so breaking camp was leisurely the next morning. All of the cattle were out of the pen and on the trail by the time Ira checked with Leon. No one knows for sure what started it. Some say there was a small stampede and Ira blamed Leon. Others contend (Continued on page 55)

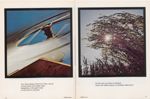

Under Sail

On lakes and ponds across Nebraska, mariners with bent for solitude find the ultimate in satisfactionWhether running before the wind or watching from shore, summer sailing regatta is something special

RUSHING WIND fills billowed sails, sweeping away worldly cares as it meanders across open expanses of water. Lapping waves lick the hull, spewing past the stern to slide silently into a mirror surface behind the ' craft. Polished decks reflect shimmering rays as sacrifices to appease the gods of water, wind, and sun. Suntanned hands steer the craft through intricate maneuvers with staccato rhythm on the tiller. This is sailing, NEBRASKAland style, key to adventure and relaxation on the state's waterways.

Among man's most primitive forms of water travel, sailing craft have been refined and have come into their own on myriad lakes and rivers throughout the state. Superimposed on tree-studded bluffs at Lewis and Clark Lake in the northeast or sprawled across a watery horizon at Lake McConaughy in the southwest, sailboats of all classes create a not-to-be-forgotten beauty under summer's azure skies.

Even beached, sailboats of any class look graceful. Underway, they are beautiful to behold and great fun to navigate, creating a feeling unlike any other type of craft

No sputtering engines disturb the silence of sailing. Man hears his environment as never before. And, his surroundings smile upon him. NEBRASKAland skies unleash gentle breezes to fill his sails. Inviting water abounds to quench the thirst of his wanderlust. And, from novice to seasoned sailor, he is master of all he surveys. A fluid horizon is his goal, just out of reach with each tack into the wind, yet as desirable as any siren. And, though each maneuver changes the geographic goal, the ultimate remains —tranquility.

The thrill of sailing goes beyond the man and his boat, however. Sailors and hundreds of spectators, be they judges or happenstance observers, marvel at the beauty of a regatta. Whether afloat or landlocked, bystanders revel in the magnificence of man, boat, and water. Settings may change, but the thrill of boats under canvas never alters.

The temperature hovers near the 50-degree mark as a motorized pleasure craft slips away from a dock on a Nebraska lake. Bucking ever-growing waves, the launch

Wind-driven craft differ from motor boats in many respects. Angling into the wind and turning are not done merely by a twist of wheel or push of accelerator

heads west toward the end of the lake. With the far shoreline nearing, the helmsman brings the bow about for a run back up the lake. But as he comes about, billowing clouds that shroud the eastern horizon break away like curtains on a stage. Sunlight spills through the breaks, forming golden blankets over a dozen gleaming white sails flitting across the water surface. The power boat draws nearer, allowing a view of sailors nestled in the cockpits, dodging the boom as they jocky for position and a favorable wind. A boat corners too sharply, spilling its occupants overboard. Two others sweep in to pick up the crew and right the craft. While the accident is not uncommon to small boat regattas, it provides a chuckle for the power-boat skipper as he threads his way past others of the flotilla.

This then, is sailing in NEBRASKAland. At various regattas across the state, similar scenes are common. From Lewis and Clark, to Holmes Lake in Lincoln, to Johnson Lake near Lexington, to Harlan County Reservoir near Alma, to Lake McConaughy near Ogallala, the scenes are the same, only the boats and the men change. Numbers may vary from east to west, but a man can become a sailor overnight, and a single sailboat can become a fleet. Sailing is growing across the state. And the sight of white sails backdropped by blue sky and water will continue to stir the blood and imagination of he who searches for beauty or longs to go down to the sea again. THE END

Partner in destiny

Man studies grouse for better management, but also because both have similar problems

by Leonard Sisson Senior BiologistTHE STATION WAGON pulls off the gravel road onto a sand trail and comes to a halt. Two men climb out and stretch, taking deep breaths of the fresh, Sand Hills air. After a long drive during pre-dawn hours they had arrived at the Nebraska National Forest near Halsey in time for the opening of prairie-grouse season. The 100 square miles of Sand Hills prairie in the forest is sharptail country. As these veteran hunters let their anxious dogs out of the car, they know they may have to walk most of the morning before flushing a grouse.

Sportsmen like these harvested approximately 650,000 sharp-tailed grouse in the United States and Canada during 1969. To the hunter, the sharp-tailed grouse is most important as a game bird.

As the first rays of light announce the dawn of a still and clear spring morning, we find another type of "hunter" on the national forest. Armed with binoculars and a camera with telephoto lens, this "camera hunter" sits patiently in a plywood blind situated at the perimeter of a sharp-tailed grouse "dancing ground", awaiting the spectacular courtship activities of the male grouse. To this amateur naturalist, and many like him, thesharptail is important.

The same spring morning in a different part of the forest, a four-wheel-drive pickup winds its way carefully along a ridge and, descending into a flat valley, rolls to a stop about 100 yards from a motionless windmill. As the driver rolls down the window and glasses the knoll adjacent to the windmill, several crouched forms appear in the sparse vegetation which look like gray statues in the early morning light. The observer quietly counts the motionless forms. They are sharptails on the same dancing ground he has watched in past years. He then takes the air temperature with a pocket thermometer; a small instrument called an anemometer he holds out of the window to determine wind velocity and direction; and finally, he measures the light intensity in foot-candles with a light meter. All of this information is recorded in a small notebook and the time is noted. After several minutes of patient waiting, the knoll comes alive with activity as the male grouse begin to "dance". The observer again checks the time, light intensity, and number of birds, recording this additional information. After a few minutes of activity, a few more birds appear at the outskirts of the display area. These birds seem unconcerned about the whole affair, and do not display, indicating they are females. With the number of females and males recorded, the observer gathers up his recording instruments and prepares to depart for another display ground.

Dancing ground is courtship arena as males compete for attention of hensThis observer is a biologist for the Research Division of the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. He is one of the investigators in a long-term project initiated in 1958 to study the ecology and management of prairie grouse in Nebraska's Sand Hills.

Prairie grouse in Nebraska include the sharp-tailed grouse and greater prairie chicken. Most of the work on this study has focused on sharptail, the more abundant of the two species. This biologist recognizes the importance of sharptails as a game bird. In fact, a large portion of his work is supported by revenue from tax on firearms and ammunition. One of the objectives of his research is to gain knowledge necessary to keep the harvest by hunters in balance with the number of grouse. He also sees the importance of the grouse for "camera hunters". However, his knowledge of the history and ecology of wildlife demands that he look at the importance of the sharptail from a different perspective.

He sees the sharptail as one of the few survivors of the life cycle, supported by the vast grasslands which once clothed much of the central portion of North America. He sees the sharptail as belonging to the larger life system of the entire earth which he calls the biosphere. He sees man as a part of the same community of life upon which both man and the grouse depend. The importance of this bird is in the destiny it shares with man.

To understand the sharp-tailed grouse, we must look at its relation to the prairie community in which it developed. As other species in the community, the sharptail had to qualify for membership. One of the important qualifications is a means of population regulation.

Sharptail mating takes place during spring at specific locations several acres or less in size called dancing grounds. The same site is often used year after year. Male sharptails display on these sites and females come to the grounds for breeding. Studies have shown that the number of males on a given ground may vary from year to year but that only one or two males on each dancing ground do ali the breeding in a given year. Each male grouse on a ground defends a small plot a few square yards in area by displaying and intimidating cocks holding adjacent territories. The cock which can outdo his rivals takes a dominant position on the display ground which is usually near the center of activity. Females enter the display area amidst the displaying cocks, which causes increased tempo in the activity of the males. If a female is receptive, she will approach the territory of the dominant male and allow copulation. Thus the number of females bred is more or less independent of the number of males on a ground.

The number of dancing grounds is also limited. Studies on the Nebraska National Forest, for example, indicate an average density of about one dancing ground per square mile. Ecologists believe such behavior evolved because it can regulate numbers of grouse produced which is of benefit to the total community. This means of regulating numbers is self-perpetuating, as those males which display most avidly contribute the most, genetically, to the next generation.

As are all members of a community, the sharptail is dependent on a variety of other species. Another requirement for membership in the community is that this dependence is one of mutual benefit. After mating, female sharptails establish a nest in dense grass, usually on a north-facing slope of a dune, which normally has denser grass cover and provides protection from the hot afternoon sun and southerly winds. The eggs usually hatch in mid-June during a two- or three-week period, well synchronized with insect abundance which will (Continued on page 53)

Passion for tradition

Winter's sun captures hunters sweeping night's frost from each of the decoys

Larry Golden and wife, Pat, share most of their leisure hours in a goose pit west of Oshkosh, honoring a family heritage and preserving a tradition

In a hurrying world, discipline and love of sport combine to preserve elegant days gone by

PASSING TIME is distasteful for most everybody, but forwaterfowlers it is especially lamentable. Memory hearkens back to good days on the marsh when skinosed canvasbacks lay back into gusty headwinds before settling down among hand-carved blocks; days when phalanxes of greenheads twisted their long necks in response to the chuckle of an experienced call; when that incomparable tingle ran a waterfowler's spine as the gabber of big honkers pierced the pre-dawn darkness.

Those days seem all but gone now. Waterfowlers are left with only the sport's remnants and fireside sagas. Victims of unplanned progress, die-hard duck and goose hunters are left with the short end of a cause-and-effect catastrophe —more people, more wheat, less marshland, fewer waterfowl. Man's swelling numbers seem to have brought the death of an era, and the passing of a certain breed of outdoorsman.

Hand-crafted arms have been replaced by mass-produced hunks of metal. Hand-carved decoys have been supplanted by styrofoam hoaxes. Goose hunting has been reduced to a dogmatic regime of disciplined gunning. The taking of a honker or a brace of ducks has become impersonal. Success is all too often measured by how little time or effort it takes to fill a limit. The aesthetics of hunting are all but lost.

But amid this world of mechanized madness and gadgetry, a few idealists still cling to old standards, honor old customs, and worship waterfowling traditions. The Goldens of North Platte are such sportsmen.

For members of this family, and others like them, the grand old days of waterfowling are more than just memories or tattered photos resigned to the family scrapbook. For them those grand old days are still alive.

It was a normal Wednesday morning for the rest of the

world, but for Larry Golden and his wife, Pat, it was one

of those days cut from the early 1900's. The sport had

changed since then, but the same intrinsic emotions were

still woven into these hunters' makeup. A modern trailer

sat where the old hunting shack had been just a few years

ago. Most of the memories of past hunts and people long

gone were centered around that crumbling shack. Fire

had consumed its old wooden frame, but the memories

had survived.

had consumed its old wooden frame, but the memories

had survived.

The 12-gauge Parker broken over Larry's arm and the 20-gauge that Pat carried attested to the tradition and pride of former days. For Larry, a man's shotgun was more than just a gun. It represented the pleasure of owning a hand-crafted, quality arm.

Like a molten globe, the sun broke the horizon, silhouetting the hunters as they brushed night's frost from their decoys. It was a traditional scene, one Larry had been a part of many times before. The wooden bridge that crossed the slough, the mass of decoys clustered together, and the strings of ducks trailing off the river to feed were all close acquaintances. They had met many times.

Its brief moment spent, the sun slipped behind a blanket of clouds as Larry, Pat, and the other hunters slid back the doors of the pit. Cushioned benches, heaters, and the comfort of warm, dry feet were new additions to the pit—luxuries that seemed essential with youthful exuberance left behind. Not long ago there had been only one pit where now there were three. Wet, cold, and uncomfortable it, too, had done its job.

The sliding doors snapped shut as the first flock of honkers lifted off a sandbar roost and worked its way west toward the pits. The geese would pass over many a convincing spread of decoys before reaching the Goldens' pits. They had crossed this area many times during their days of resting on the Platte's shallows. Each flock had its wise old birds that knew the dangers of the large spreads of decoys in the lowland meadow. A good thing, too, for how many birds would survive the season if they decoyed easily? What challenge would that be for the hunter?

A dome of wire fencing loosely thatched with native grass topped each sliding door, permitting full view of approaching geese without revealing the hunter. At first, each pit had had only one dome, but the brothers had decided that watching the geese decoy was just as important as shooting. Now, each hunter had a clear view of the action.

Some 15 Canadas beat their way rhythmically along the river's edge toward the sunken pits. Still several hundred yards away, four or five set wing and began a graceful glide that would take them to the decoys. Wildfowl wisdom soon revealed itself, though, as the flock's sage old matron whipped the eager juveniles back up into formation and away from the enticing spread. Here was the hunter's real test —to lure even the experienced goose into range. It was an old story for the hunters in the pits.

Flock after flock left the roost area and moved out to feed, some north to the grain fields, but mostly west along the river and past the decoys. At no time during the morning were the skies void of ducks or geese. Every time a cup of coffee was poured, geese came encouragingly close, making the hunters abandon their warm brew. As if by biological clockwork, the birds played games with the sportsmen, entertaining them just long enough for the coffee to chill, then winging away down the river.

Ducks pumped in and out of the warm-water slough with regularity, but no one even considered jump shooting mallards with honkers in the sky.

Lulls in the flights encouraged mental meanderings to days gone by. Memories about clearing the meadow of its tangled undergrowth were fresh in Larry's mind. Blisters from cutting the maze of roots, and black smoke curling skyward as burning tires dripped flaming streams into brushpiles had left their marks. It had been backbreaking work, but work with a goal.

Some days see many geese fall, some see few. Success is not measured in numbers

Each decoy carried a story, and each had a unique history. There were the six hand hewn from old railroad ties with a draw knife, and those old papier-mache dekes assembled in haste the year opening day had crept up faster than expected. And then there were those old canvas honkers which Larry's father and grandfather had used, probably crafted in some dim little cellar. All were special in their own way; all performed their task well.

Another 20 geese lifted off the roost and pumped their way over the slough's meandering course. They were low enough, in good range, and heading directly toward the pits. It seemed unlikely that the urgent, enticing sounds coming from Larry's call were in any way linked with the spasmodic convulsions he went through to produce them. But the educated birds, well versed in the eternal test between man and fowl, swung abruptly up, fully understanding the association between decoys and gunpowder.

The geese came, Larry's call inviting them. They twisted their necks and then flew on down the river. It was a familiar scene —an expected one. Each hunter accepted it as part of the game.

Then they came from the west, gliding in on arced wings. Rocking from side to side like playful gliders, they drifted into marginal gun range. A last-minute mix-up in ground rules, however, ended the hunters' chances. As the birds flared, changing direction to come into the wind before dropping into the spread, a hunter in another pit slid open the doors and tried the birds. He thought they were winging away. It was an honest, but regrettable mistake; one seldom tolerated by these exacting waterfowlers. After thought, in any case, was of no use. The geese were not going to come back. But it wouldn't happen again. Sky busting has always been taboo from these pits. The occasional bird that is pulled down with such tactics just isn't worth the ones that fly away carrying a load of No. 2 shot under their skins. Honkers deserve a better fate than that.

With wings set in ballet of flight, a flock of Canadas drifts downward

Action waned and thoughts wandered again. Goose hunting seemed so neat and easy now. The meadow was clear, pits were dug, and decoys were in good shape, but things hadn't always been that simple. It has been many years since Larry's grandfather had bought and farmed the land. He had passed it on to Larry's folks with the stipulation that, at all costs, it stay in the family so the children and grandchildren would have a place to hunt. It was a heritage passed on from one generation of hunters to the next. Offers to buy the land or lease the hunting rights had been numerous and generous since then, but the Goldens have never considered selling, even though it is costly to maintain. Regardless of the scrimping it has often taken to maintain the family's hunting tradition, not a single person has ever been charged to hunt there. Numerous invitations to come and hunt go out to friends and acquaintances. All are treated with hospitality unique to the waterfowling fraternity. Nights before the hunt are characterized by crowds of hunters jamming the trailer. Bunks line most every wall to accommodate all, and pitch games and stories run late into the night.

While a commercial goose-hunting operation would probably support the entire family, it is unique that these people are so dedicated to providing sportsmen with the benefits of this area. The only charge to guests is that they share this passion for tradition.

The morning was almost over and the geese were showing little promise of heeding Larry's call, but no one moved from the pits or even suggested going to the trailer for lunch. Strange assortments of snacks appeared from every niche and corner of the pits to satisfy the hunters' hunger.

And then they came —like flights of bombers —from every quarter. Some weather change, some innate sense of time, or some biological catalyst had triggered mass movement. In flocks of 4, 20, or 80, they were everywherecoming, going, landing, rising, circling. Heads pivoted in the thatched domes like radar scanners trying to follow all the birds.

First came 10 on set wings from the northeast, gliding directly into the decoys without even circling. Like miniature blimps they settled down, their creamy breasts flashing in the sun. Rocking back and forth with oversize black webs extended and long necks turning, they plummeted into the decoys.

Then 4 more glided in from the south. Finally, 30 or more swung from the north into the wind and began drifting down toward the pits. This must have been how it was in those early days of supreme waterfowling. Admiration for the giant geese filled every hunter as the birds drifted down. Perhaps each sportsman doubted momentarily if he could slide back that door and kill one, but it had always been like that. Man was the hunter and the goose the hunted. It was a natural relationship, but so was respect for the quarry. If that should ever be lost, hunting would become primitive gunning. There was no such gunning from the pits that day. There was sorrow for the death of each majestic bird, yet pride with each goose that fell to their guns.

As Larry walked back to the trailer he wondered if there would be more days like this. Or was it one of a numbered few? THE END

Johnson Lake

Central location makes this a popular spot for anglers and other water-sport bluffsCOME SUMMER, and any given Friday evening will find Interstate 80's westbound lanes jammed to near capacity. Many of those on the road doubtless are tourists headed for destinations outside Nebraska. A good share of them, though, are natives, bent on a weekend of fun on any number of the state's large impoundments. And, because of its convenient, central location, chances are good that a high percentage of these fun-seekers are bound for Johnson Lake, an offer-everything, do-anything reservoir some seven miles southwest of Lexington on U.S. Highway 283.

This singular area, nestled above the Platte River Valley, hasn't always been so booming, though. In fact, the ground that the lake covers was just so much farmland until the early 1940's. But there were dry years in the 1930's, and agriculture was on the ropes in a 10-rounder that looked like a sure victory for nature. The regulatory reservoir of the Central Nebraska Public Power and Irrigation District put an ace in the farmers' hands, though. And, when the lake reached its usable level in 1941, things began to happen fast. Some people say, in fact, that they have happened much too swiftly for the good of both Johnson Lake and its recreational potential.

The story of Johnson Lake as a leisure-time attraction actually began in earnest when the reservoir, boasting approximately 1,200 acres of surface area and 50,000 acre feet of water at capacity, was full. The year was 1941, and almost immediately an organization called Johnson Lake Development, Incorporated, began negotiations to open adjoining land to private housing. Controlled by the Central Nebraska Public Power and Irrigation District, Johnson's shores were off limits to settlers. But before the end of the year, they had secured lease-type permission to develop the shoreline. Though (Continued on page 53)

When not in a boat, residents at lake can putter around on grass-green links

Boating is main pursuit, and marinas are keeping pace with growing demands

Somehow, near-capacity use of lake by craft in summer works smoothly

Notes On Nebraska Fauna Meadowlark

Western variety is Nebraska's state bird. But there are two species of this flamboyant songster in the countryside and telling them apart is a job only for experienced experts

THE MEADOWLARK is the most characteristic bird of the Nebraska farm. It is valued by the farmer not only because of its charming simplicity and its cheerful, spirited song, but also because it eats insects and weed seeds. The coming of the meadowlark in early spring while the fields are still brown is a thrilling event. It announces its arrival with a song as it stands on a fence post, with its bright, yellow breast gleaming in the morning sun.

The meadowlark is a member of the family Icteridae which includes black-birds and orioles. The scientific name of the Western meadowlark, Nebraska's state bird, is Sturnella neglecta. It is considered a common resident and breeder throughout the state, but is most populous in the western half. The Eastern meadowlark, Sturnella magna, is also found in Nebraska, primarily in the eastern portion. The two species are almost identical and are extremely difficult to distinguish from each other except by song. Both are chunky, brown birds, showing a conspicuous patch of white in flight on each side of their short, wide tails. Other flight characteristics are short, rapid wingbeats alternating with short periods of sailing. A bright yellow breast is crossed by a black V. When walking, it nervously flicks its tail open and shut. The song of the Eastern meadowlark is a series of slurred whistles. The Western meadowlark's song is made up of 7 to 10 flutelike notes.

In spring and early summer, Western meadowlarks travel chiefly in pairs but throughout the fall and winter they forage in flocks numbering anywhere from 10 to 75. The flock organization is loose. In fleeing from danger each bird takes its own course, remaining with or leaving the flock at will. As fall approaches, flocks begin migrating. These migrations are not greatly extended or very conspicuous, though, for the bird is a resident of most of its breeding range. It amounts to a gradual withdrawal from the northern, summer haunts, or from regions where feeding grounds are covered with snow.

Soon after its arrival at the nesting area in early spring, the male selects a territory. Size of the territory varies from 6 to 20 acres. By intimidating songs and alarms, displays and disputes, the male defends his domain. Very seldom do competing birds come to blows. The arrival of the females on the breeding territory stimulates the males to courtship. The courtship is featured by elaborate displays, spectacular flights, and intensive singing. Males have been known to mate with up to 3 females, with all the females nesting at the same time. Females are not hostile to one another as they are in many other species. They feed together, associate with the male together, and often nest within 50 feet of each other.

The meadowlark nests on the ground beneath a thick tuft of grass or weeds. Nests are usually placed in meadows or pastures, but some have been found in corn, alfalfa, and clover fields. The nest is usually made of dry grass lined with finer materials and may have a tunnel of grass leading to it. Often this tunnel, or runway, is the only clue to the location of the nest. From 3 to 7 eggs are laid, but sets of 5 are most common. They are white and spotted all over in varying shades of brown and purple. Both male and female assist in the construction of the nest, which usually begins in April, and also in incubation, which lasts about 15 days. The young leave the nest in about 11 days after being hatched when they are able to fly, depending for safety on hiding themselves in the grass. They are cared for by the parents until they can provide for themselves. When they become independent, they are chased out of the territory by the male. Sometimes 2 broods are raised in a season. The first brood is usually hatched by the end of May and the second by the end of July.

Few birds are liked as well by farmers as the meadowlark. More than half of the meadowlark's food consists of harmful insects. Its vegetable food (27 percent) is composed of noxious weeds, grass seeds, and waste grain. The remainder consists of useful beetles or neutral insects and spiders. Grasshoppers can be the most important item of food for the meadowlark, often amounting to 29 percent of its annual diet and as much as 69 percent in the late, summer months. Beetles and caterpillars are next to grasshoppers in importance. Meadowlarks have been known to eat certain fruits such as wild cherries, strawberries, and blackberries.

Meadowlarks have many enemies, such as the great horned owl, goshawk, red-tailed hawk, skunk, weasel, mink, raccoon, various snakes, magpie, and the domestic cat. Man, directly or indirectly, is responsible for the loss of a great many meadowlarks and probably he is the most important factor in the control of the species. However, the meadowlark's high reproductive capacity and skill in concealing nests serve to perpetuate the species, which is just as well because it is a pleasant bird to have around. THE END

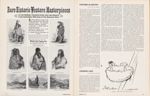

Rare Historic Western Masterpiece

by Carl Bodmer, renown artist, who was featured in the Septermber, 1970 issue of The American West.

Limited Edition of eight of his works reproduced from the Original Edition, 1843...for collectors, historians, libraries, museums... an ideal gift...a qunique "find" for interior decorators.

Style for framing on 14" x 20? select heavy antique paper.

Mailed Flat for Protection$7.50 per print, $35.00 for set of eight postpaid, (in Calif, add 5% sales tax] Order individual prints by number. Send money order or check to:

Western Sky Trading Post P.O. BOX 746 • DEPT NL CLAREMONT, CALIF. 91711 Dealer Inquiries InvitedPARTNER IN DESTINY

(Continued from page 43)form the diet of the young chicks. Such synchronization is not by chance, but results from the fact that grouse broods hatching at such a time stand a better chance of surviving, thus perpetuating the good timing with insect abundance.

As the young develop, their diet shifts to plants and by the time fall approaches, and insects are less abundant, weed seeds on disturbed soil make up much of their food. A staple food of sharptails in the Sand Hills are rose hips, which are abundant and remain on the roseplantthroughoutthe winter. By developing this characteristic, the rose plant insures its own dispersal and survival by way of such gourmets as the sharptail. Thus, the grouse fits well into its community on which it is both dependent and depended upon. Such dependence is seldom obvious and is still not completely understood, for its study —ecology —is still young.

The sharptail is a survivor, present only where its community has not been destroyed by man. The Sand Hills form one such community. Man tried to farm the Sand Hills, but was unsuccessful because the disturbed soil was susceptible to erosion by wind. He replaced part of the community —the bison, elk, and their predators, the plains grizzly and wolf—with the cow. Man often fails to control the abundance of this domestic grazer, resulting in damage to the plant life and animals such as the sharptail which are dependent on it. Now the technology, of which man is so proud, has given him the ability to irrigate the Sand Hills for production of more grass for his cattle and more acreage for his corn.

Man continues to justify his destruction of natural communities by the need for more food for a growing population, but he is now beginning to realize that his inability to control his own numbers is disqualifying him for membership in the community of life in which he developed and upon which he depends. Man has long been saddened by the loss of wildlife, but only now does he realize that he shares its destiny. THE END

JOHNSON LAKE

(Continued from page 48)some of the people in charge may have had a hint of what was in store for the lake, probably few dreamed their development would reach the extent it has. When the new residents at Johnson Lake moved onto their land in 1941, they were there to stay, and most still maintain a cabin on the shores of Johnson Lake after more than 30 years, though many live elsewhere in the winter. All of them, however, have watched Johnson Lake grow over the years.