WHERE THE WEST BEGINS

NEBRASKAland

Febuary 1972 50 cents 1 CD 08615 A 12 FULL-COLOR GUIDE TO DUCK IDENTIFICATIONNEW LOOK AT AN OLD FRIEND, THE OWL CRAPPIE FISHING, THE WAY YOU LIKE IT NEW HOPE FOR HANDICAPPED OUTDOORSMEN

Egg of Rocks Gem-quality rocks are found in all parts of Nebraska, and looking for them is as much fun as working on them.

Phenomenon of Migration Even though the phenomenon of migration has been observed for ages, its causes still remain a mystery to man.

A Spirit Unique Despite a handicap many other people fail to overcome, Bill Gilmore enjoys outdoor hunting with seasoned veterans

Cat with Wings Death rides the wind when the great horned owl is on the wing in a world of wildlife where might makes right.

One of many migrating duck species, the redhead appears on this month's cover. The majesty of a Nebraska winter sunset is portrayed on page 3. Both photos were taken by NEBRASKAland's Lou Ell.

Boxed numbers denote approximate location of this month's features.

NEBRASKAland

FISHING AND HUNTING BACKWATER CRAPPIE Jon Farrar 16 PHENOMENON OF MIGRATION 22 A SPIRIT UNIQUE W. Rex Amack 38 TOURISM NEST EGG OF ROCKS Lowell Johnson 20 OUTPOST OF EXPANSION Warren H. Spencer 34 TRACTORS OF TIME 52 ROUNDUP AND WHAT TO DO 59 WHERE TO GO 55 GENERAL INTEREST SPEAK UP 5 FOR THE RECORD: NATURE CONSERVANCY Willard R. Barbee 8 PRAYER FOR GRAY DAWN Alice J. Shooter 10 HOW TO: TUNE UP CAMPING TOOLS 12 COVER COME LATELY Clarence Newton 42 CAT WITH WINGS Steve Olson 44 NOTES ON NEBRASKA FLORA: NEW ENGLAND ASTER 50 OUTDOOR ELSEWHERE 66 Art Director: Jack Curran Art Associates: C. G. (Bud) Pritchard, Michele Angle Photography Chief: Lou Ell Photo Associates: Greg Beaumont, Charles Amrstrong, BobGrier EDITOR: DICK H. SCHAFFER Managing Editor: Irvin Kroeker Senior Associate Editor: Warren Spencer Associate Editors: Lowell Johnson, Jon Farrar Advertising Director: Cliff Griffin NEBRASKA GAME AND PARKS COMMISSION: DIRECTOR: WILLARD R. BARBEE Assistant Directors: Richard J. Spady and William J. Bailey, jr. COMMISSIONERS: James Columbo, Omaha, Chairman; Francis Hanna, Thedford, Vice Chairman; Dr. Bruce E. Cowgill, Silver Creek, Second Vice Chairman; James W. McNair, Imperial; Jack D. Obbink, Lincoln; Gerald R. Campbell, Ravenna; William G. Lindeken, Chadron. NEBRASKAland, published monthly by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. 50 cents per copy. Subscription rates: $3 for one year, $5 for two years. Send subscriptions to NEBRASKAland, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Copyright Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, 1972. All rights reserved. Postmaster: If undeliverable, send notices by Form 3579 to Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Box 30370, Lincoln, Nebraska 68503. Second-class postage paid at Lincoln, Nebraska. Tourism articles are financially supported by the Department of Economic Development.

Speak Up

NEBRASKAland Magazine invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to Speak Up. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters. —Editor.

RAW DEAL-"Last August, I visited the Gretna State Fish Hatchery where I was employed from 1933 to 1935.

"When I worked there, the facility was thriving. Thousands upon thousands of trout fry and fingerlings were produced and planted each year. Great numbers of largemouth bass, bluegill, sunfish, and channel catfish were also bred there.

"Gretna was a showplace, a place where people could take their families or friends for a day's outing and also learn of the intricate process of artificial fish production. A complete and fine exhibit of many fish species was in the hatch house, and qualified men were on hand to answer questions.

"There was a beautiful, well-kept park and recreation area on the hill, with tables and benches for picnic lunches and swings for the young to enjoy.

"Last August, I found nothing but depredation. The ponds were nearly all dry. The hatch house was locked and boards covered the doors and windows. There seemed to be little activity anywhere on the place.

"Fishermen of Nebraska, I'm sure that the cost of your fishing and hunting licenses has increased considerably over the years. I am also certain that you are getting a very raw deal for the money you are paying to the Game and Parks Commission." —Cecil A. McDaniel, Paradise, California.

LOU WHO?-"Writing fan letters has not exactly been my ilk, but I feel Lou Ell should get one.

"I have long admired and enjoyed his pictures in NEBRASKAland, but he outdid himself with Birches and Waterfalls in the November, 1971, issue. Those will be clipped and saved.

"You might be interested to know that I sent eight subscriptions to overseas friends. Four of them wrote letters and mentioned the waterfalls. I suspect the reason the others did not is because it takes some time for the magazine to arrive by surface mail." —Ralph Baird, Blue Hill.

BOAT ON WHEELS-"Wherever I go with my 14-foot boat, it seems to create quite a bit of interest in how I load and unload the car-top rig. I have secured wheels for the rear of the boat, making it a one-man operation to take it off the car, put in all the fishing gear, put the motor on, and push it into the water. I then remove the wheels. The whole process is simple." —Harold Morrison, Papillion.

Wheels make unloading easy

DAFFY INDEED-"A male prairie chicken on our place used to follow the tractor and plow back and forth across the field during spring plowing. Then, he tried to challenge a truck. And when the men didn't go to the fields, he came up to the place, booming and charging, and chased the grand-children around the yard. We named him 'Daffy' and made a film of his antics. But, the next day he disappeared and we have not seem him since." —Inez Loseke, Ericson.

RECIPE NEEDED-"Can you obtain a recipe for summer sausage using either venison or beef?" —Matt J. Simmons, Omaha.

None of our staff is familiar with such a recipe. Perhaps, however, some of our readers might have one. Any help would be appreciated. — Editor

WHODUNIT-"On page 51 of the October issue of NEBRASKAland is a picture of a marker of the spot where Buffalo Bill and Yellow Hand fought. Could you tell us who built that monument?

"I have seen it and I am positive Jacob A. Rainey of Ardmore, South Dakota, put it up. If so, the large rock was one a Mrs. Konrath used when she made kraut each year. She used it to hold the cabbage down in the brine.

"Also, if Mr. Rainey built the marker, it was a lookout station, and east of there a short distance is another marker he built at the same time. It was in a low spot and was the actual spot where Yellow Hand was killed." —Mrs. Izora Rainey, Valley Mills, Texas.

After considerable checking, the origin of the marker remains a secret to us. Perhaps area residents would be so kind as to fill us in. — Editor.

GREAT BUT GONE-"The water colors illustrating The Girls Went Canoeing in the July, 1971, issue were superb. I would love to have mountable prints of all three. Is there any chance that NEBRASKAland could reproduce them for sale to its readers?" —J. B. Baumann, Denver, Colorado.

Unfortunately, no such possibility exists. Since the art was original, we do not have photo transparencies of it. And, the watercolors themselves have been disposed of. — Editor.

GET INVOLVED-"As a resident of Miller, I feel that I must answer Mr. Lowry's letter in NEBRASKAland's November Speak Up Column.

"Mr. Lowry, have you studied the pros and cons of the Mid-State Reclamation Project thoroughly? Are you aware that now, instead of diverting water from the Platte, that it is rumored that they have proposed to fill the dam with water from 600 wells? This gets the National Audubon Society out of the way, and saves the Platte. But what, pray tell, will these 600 wells do to the water

Amazing New SUPER AEROSOL Bait MAKES FISH BITE or NO COST

Look at 1,295 lbs. of fish landed by Roy Martin party, Destin, Florida. Gypsy Fish Bait Oil used on every bait. Hundreds of letters of praise on file.

More lucky fishermen proudly displaying their catches. So, no matter what type of bait or lure you use, one spray of Gypsy with "SPF 83" from Aerosol can should produce "magic-like" results.

Science has just developed a sensational new substance called "SPF 83-" which throws off a pungent odor that all fish love. It is now blended exclusively with GYPSY FISH BAIT OIL and put into AEROSOL cans to make it America's most powerful and easiest-to-use bait for all kinds and types of fish. ""SPF 83"' has the magnetic power that attracts fish from great distances through thousands of smell organs which cover their bodies. They fight like mad for your bait and the biggest ones usually get there first. New GYPSY with ""SPF 83" in Aerosol cans is so easy to use, it makes fishing more fun than ever. No more messing with eyedropper, no more spilling on clothes or gear—just a press of one finger on the stem and "swish" your live bait or lure is "loaded" and ready to catch your limit in half the usual time. So, whether you're a novice or an "old timer" get the new SUPER AEROSOL GYPSY today.

POWER IN A CANNEW GYPSY with "SPF 83" has been packed in Aerosol spray cans to take all the work and mess out of "doping" your bait. Here's how easy it is. Shake can once or twice, point hole in stem toward bait, press stem and watch the fine vapor spray cover your bait with the most amazing fish bait odor ever. If you cast or troll, repeat as often as necessary to keep your bait power-packed. Each Aerosol can contains a full season's supply of GYPSY with "SPF 83". You'd better order several for your party .. . they'll all want to try it.

There's nothing in Aerosol Gypsy with "SPF 83" to pollute water or harm fish so it's legal in all states including Alaska and Hawaii. No matter if you're a guide, a beginner or an expert, new Aerosol Gypsy with "SPF 83" is a must for your next fishing trip.

FISH GO CRAZYNo matter if you still fish, cast, spin or troll ... if you use live bait or artificial lures ... if you fish rivers, creeks, lakes, ponds or the ocean you'll he thrilled with the fast action you get with "SPF 83" fortified Aerosol spray Gypsy. One whiff of "SPF 83" and fish streak toward your bait, fighting mad and you'll soon have them in your creel.

Here's our daring get-acquainted offer . . . try new Aerosol Gypsy with "SPF 83" at our risk. Order today. On arrival pay postman only $4.98 for 1 can plus C.O.D. charges, 2 cans for $7.50, 5 cans for $15. Save high C.O.D. charges and remit with order, we ship prepaid. So new, Gypsy with "SPF 83" is not yet sold in stores. Order by mail and get a FREE copy of "99 Secrets of Catching Catfish". Rush order to:

WALLING KEITH CHEMICALS, INC., DEPT. 36-B P.O. Box 2005, Birmingham, Alabama 35201 CLIP AND MAIL THIS COUPON TODAY Walling Keith Chemicals, Inc. Dept. 36-B P.O. Box 2005, Birmingham, Alabama 35201 Send me the GYPSY FISH BAIT OIL with "SPF 83" I have checked below: 1 Aerosol Can Gypsy with SPF 83 @ $4.98 plus FREE BOOK 2 Aerosol Cans Gypsy SPF 83 (5 $7.50 plus FREE BOOK and 2 Black Shadow Bugs Bonus. 5 Aerosol Cans Gypsy with SPF 83 @ $15. plus FREE BOOK and 2 Black Shadow Bugs Bonus. Enclosed find $ship postage paid. Ship C.O.D. I will pay cost plus C.O.D. on arrival. NAME ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIPSUPER BONUS Order two Gypsy at $7.50 today and get 2 Black Shadow Bugs, the frightful bug for surface action.

Ecology, Environment and Ducks Unlimited.

How More Than 200 Wildlife Species Have Benefited From DU's Environmental ManagementThis is the story of a pioneer achievement in the business of ecological management.

It started 35 years ago.

At that time a group of American conservationists banded together to organize a nonprofit organization designed to help protect and increase the supply of wild ducks on America's flyways. Today you know this organization as Ducks Unlimited.

The efforts of DU and its companion Canadian counterpart have resulted in the creation or restoration of over 1,000 "duck factories" covering some 2,000,000 acres of waterfowl nesting habitat. Geese and ducks and over 200 species of wildlife now live in areas developed by DU. This includes birds of all kinds, various species of grouse, deer, fox, beaver, moose and, in some areas, even whooping crane.

Recently DU, in cooperation with Canadian governmental agencies, activated a new master plan which must be completed by 1980. A key part calls for turning another 4,500,000 acres into drought and flood-proof duck factories. Each project will be located strategically in crucial duck producing areas—will vary in size from a few acres to several thousand—and will make these areas ideal for waterfowl breeding.

Perhaps DU's single most important achievement has been the solid awareness it has instilled in civic and government leaders on both sides of the border of the urgent need for prudent conservation programs.

If you have a deep concern for ecology and environment, perhaps you, too, will conclude that the work of Ducks Unlimited truly merits your annual financial support.

Send your tax deductible check for $10 or more to Ducks Unlimited, Dept. F014, PO Box 66300, Chicago, Illinois 60666.

Join Up Today Send NEBRASKAland to a Faraway friend or relativeThey'll appreciate your thoughtfulness, and you'll know you've done your part to promote NEBRASKAland outdoor recreation!

One year $3; two years $5. Send your subscription orders to: NEBRASKAland-2200 No. 33rd St., Lincoln, Nebraska 68503level? This not only affects us in the immediate area, but the entire state.

"I can see both sides in the matter, but let's take a good look at the long-range aspects before we say, 'Oh well, let somebody else take care of it, we're not involved'. Like it or not, all Nebraskans are involved in this project. After all, we're all paying taxes for it." — Anonymous, Miller.

RARE FIND-"Enclosed is a photograph of the American flamingo seen from October 20 to 26, 1971, on Cresent Lake, Garden County, Nebraska." — Ronald L Perry, Refuge Manager, Crescent Lake National Wildlife Refuge, Ellsworth.

Details on where the bird came from are nonexistent. However, speculation is that it escaped from a zoo, and hunters were cautioned not to shoot it — Editor.

American flamingo

DUCKY DECOY-"Who made the decoy on the cover of December's NEBRASKAland? It is an excellent specimen and I would like to obtain one." - James Sheridan, Anchorage, Alaska.

JUST THE THING-"On the cover of your December issue is a wooden decoy that would be just the thing for my fireplace mantel. Any information as to where I could buy one would be greatly appreciated.'' - William Sulesky, Euclid, Ohio.

Information on the decoys may be obtained by contacting Ralph Stutheit, 6000 Colfax, Lincoln, Nebraska 68507 — Editor.

NEBRASKAlandPollution can be taxing

Some people oppose polluiton stopping measures because they may increase taxes.

The problem of polluition can only be conquered when we, as citiziens, recognize that it costs money to fight pollution.

Support goverment efforts to replace open dumps with sanitary landfills, efficient incinerators, or modern recycling facilites. Urge local officals to provide adquate litter receptcales. Encourge community action for a new sewage treatment plant if it is needed. Support sensible ordinances to govern installtion of commerical and industrial signs.

Find out wht else you, as a local citizen, can do to fight pollution, then do it.

Keep America Beautiful Advertising contributed for the public good People start pollution. People can stop it.

WILDLIFE BY THE ACRE

Just because you don't own any land doesn't mean that you can't do something about wildlife's most important need —habitat.

By serving as a Cover Agent for the NEBRASKAland Acres For Wildlife Program, you can help people who own land preserve valuable cover.

You can be a Cover Agent by enrolling and preserving at least one acre of cover on any ranch or farm in Nebraska.

To find out what NAFW is all about, ask for a copy of "HOW YOU CAN ADD AN ACRE".

Write to: Nebraska Game and Parks Commission P.O. Box 30370 Lincoln, Nebraska 68503Ecology for tomorrow's sake

For the Record . . . Nature Conservancy

One of the most pressing problems facing any government agency which deals in real estate is the spiraling price of land. Even though the cost of most everything is going up, land values are soaring.

Thus, it has been a practice of the Game and Parks Commissioners to occasionally postpone development on property already owned by the state in order to purchase other new areas which may soon drift beyond the Commission's financial reach. However, when suitable acreage becomes available, it is not possible for the Commission to simply go out and buy it. Approval of the Commissioners, the Legislature, and the Governor must be obtained and funds must be appropriated. It is a necessary but time-consuming procedure which can result in loss of opportunity.

The problem isn't unique to the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. It is a nation-wide dilemma. A group which has recognized this situation and is attempting to do something about it is Nature Conservancy of Arlington, Virginia. A nonprofit, privately supported environmental organization, Nature Conservancy works to preserve areas throughout the country which are ecologically or environmentally significant. By using private funds, Conservancy buys land when it is available, then holds it in trust until the interested agency has the authority and money to buy it at original cost.

Now, thanks to Nature Conservancy, the Game and Parks Commission may add 320 acres to the existing Pawnee Prairie Special-Use Area. These 800 acres of virgin prairie provide a key island of habitat for prairie chickens in southeast Nebraska's Pawnee County. At the turn of the century these square-tailed prairie grouse ranged over much central prairie, but farming operations have reduced the vital grassland portion of their habitat and almost eliminated them from all tillable acres, leaving them only in the more remote areas, such as Nebraska's Sand Hills.

But, with better management during the last quarter of a century, a slow reversal of this trend has restored some of the grasslands in southeastern Nebraska and the chicken is responding. Since there are not many tall-grass habitat areas remaining in Nebraska —or anywhere else for that matter —the Commission feels that these 320 acres would be a valuable addition to Pawnee Prairie.

In January of 1971, the Game and Parks Commission sought the assistance of Nature Conservancy. Recognizing the site's importance, Conservancy purchased the tract in March 1971, after receiving a letter of intent from the Commission. Now, necessary approval and funds are being sought from the Legislature.

This is Nature Conservancy's first undertaking in Nebraska, although it has been involved in setting aside natural areas in 43 other states. Support for Conservancy comes primarily from the public, whose contributions to the organization's general fund make projects of national significance possible.

With the continued co-operation and assistance of private organizations like Nature Conservancy, the Game and Parks Commission may be able to save much-needed wild areas before they become financially untouchable.

8Get aboard Kawasaki's all new Mach II, the 350cc, 3-cylinder TriStar from Kawasaki's galaxy of superstars for 1972. Then sit back and hang on while the Mach II happens to you! Outperforms any other 350cc motorcycle made, and most 500cc. Great acceleration, 45 hp, top speed over 100 mph. The styling is unique, with striking spoiler design of seat and rear section. It's tomorrow's machine, built for today's moving generation.

Mach II —first supermachine in its class. First in power. First in speed and acceleration. And first in the race for space. Take-off time is now. See Mach II now. Then join the set.

• Kawasaki launches another first: the TriStar Triple 350 • 45hp-maximum thrust for its class • Turbine smooth —with rocket thrust acceleration year of the Kawasaki

Who causes it? Who is willing to help fight it? The Answer Is In Your Hands Nebraska is beautiful. Every litter bit destroys that beauty.

Even though Gray Dawn was on the brink of death, I refused to give him up

Prayer for Gray Dawn

THE AUCTIONEER pleaded with the crowd: "I'm bid $5-how 'bout $6 —gimme $6, gimme $6 — over there —how 'bout $7?" But no one bid higher for the little, grayroan, weanling colt with its black mane and big, frightened eyes.

"Dad, couldn't we get him? I'll take care of him," I pleaded. I was a young married woman with children of my own, but I loved animals. It was 1932 and my husband and I farmed together with my parents at Ralston three miles southwest of Omaha's stockyards. The auctioneer droned on.

At first, Dad demurred. We had no time for a colt with all the chores and planting to be done, but finally he gave in.

Our $7 bid was accepted. Now we faced the task of getting the little fellow home, so we took turns leading him and driving the car. We bedded down a very weary little traveler in the barn that night after his three-mile walk.

Almost a year passed, and the ugly little wean ling grew into a sleek-limbed, graceful yearling. He raced across the pasture at my call, head high, black mane and tail flying in the breeze, and reddish-gray coat gleaming in the sun. He often walked behind me, nipping at my shoulder or purposely stepping on my heels. Then, when I turned in anger, he gleefully raced away. We called him Gray Dawn because his coat was like the grayish red of a morning sky.

There were many animals on the farm, but Gray Dawn was my favorite. I loved him as a pet and spent many mornings grooming him, wondering what I would do if I ever lost him because of a nagging premonition I had that this might happen.

Then tragedy struck. A sleepin-sickness epidemic swept across the Midwest in 1933. Farmers, already fighting economic depression, were losing valuable horses. Wesympathized with our neighbor across the road when he lost his black Morgan mare.

Then it was our turn. Jack, our stot-hearted mule was first to go, followed by Bill, the big Clydesdale with the blaze down his face and the funny, long white hair on his legs. Teddy, the brownish-black, short-tailed hackney pony was next. We found him in the south pasture.

Fear—black fear—entered our hearts. We grieved for our workers as we stood by helplessly and watched the animals die. There was no cure, they told us, nothing we could do.

One morning Gray Dawn didn't get up. "Oh no, dear God, not Gray Dawn,' I moaned as he struggled to stand. He just couldn't die, too. Finally, gaining his feet, he seemed to fall asleep and dropped like a log. In vain, I coaxed him to eat. With wild, rolling eyes he banged his head against the stall's sides. All that day and through the following night he fought what seemed to be a losing battle. I padded his stall with straw and old blankets, refusing to give him up.

I prayed for Gray Dawn. "Dear God, if we but trust in thee, no harm can come to us or any of thy creatures." On through the long, lonely night I stayed and prayed. I pried his mouth open and filled it with oats. He chewed fiercely for a moment, then fell asleep again. I prodded him to his feet. Standing spraddle-legged for a moment, he dropped. Again and again I urged him up, forcing water from an old pop bottle into his mouth. A lot of it spilled, but he drank some.

On his way to church next morning, Dad stepped into the barn and looked down at my poor yearling. Gray Dawn's eyes were glazed with approaching death. I couldn't prod him to his feet anymore.

"I wouldn't give you a nickel for him. He'll never last the day," Dad said sadly, and left.

I sat on a milking stool with my back to the wall. Thoroughly exhausted, I must have dozed off. How long I slept I don't remember, but a faint nicker woke me. Dazed, I saw Gray Dawn standing on trembling legs, nibbling at his pan of soaked oats. The wildness had left his eyes. Battered and bleeding, he swayed a few times, then finally stood firm. I put my head in my hands and sobbed with happy relief. The battle, with God's help, had been won.

Several weeks later I watched him race across the pasture again, his beautiful coat glistening in the sun. Again he mischievously nibbled at my shoulder and stepped on my heels. It still annoyed me, but never as much as before.

I can honestly say that I feel my prayer was answered. THE END

TWICE the action!

Fly-casting a stream for the biggest rainbow trout or stalking the corn rows for the wily cock pheasant, you can enjoy it all with a combination hunt-fish permit It entitles you to a full year of all-around action in NEBRASKAland, the "Nation's Mixed-Bag Capital". For just $8 and a small issuance fee, the combo permit is every Nebraskan's ticket to recreational activity unequalled anywhere. It's available from over 1,200 permit vendors across the state, so get yours today. Get your money's worth and more, for whatever your challenge you'll be sure to find it astream or afield in NEBRASKAland.

HOW TO: Tune up Camping Tools

Midwinter hours are good time to get those all-important cutting implements into prime shape for next summer's outings

TOOLS USED in the preparation of camp firewood invariably end the season in deplorable condition. Blades are dull, handles are splintered and rough, saws have broken or bent teeth, and a sheath knife looks barely sharp enough to cut butter. Should you store the tools in a dull state, you'll likely take them back to the woods on your first scheduled campout still bearing the scars of the previous year.

Such dull tools, along with their poor performance, are dangerous to use. A dull axe, glancing off a hard log, is not too dull to bury itself in the flesh of a leg or foot.

To avoid this, an excellent time to put new edges on steel, refinish handles, and replace worn protective sheaths, is a midwinter night, possibly one when the wind rushes past the windows and snowflakes build on the panes.

Painted or scarred hatchet handle can be refinished by scraping with broken glass

Combination of holding jig and new file makes axe sharpening quick job

Protection for saw blade can be fashioned from hose, wood, leather

Heat linseed oil and rub into handle until it will absorb no more. Sand and oil again

Light on knife edge means dullsville. Hone with slicing action on stone

To completely replace an axe handle, get a new one from a hardware store. Full-size axe handles end in a "fawn foot". Saw a half-inch piece from the toe of the fawn foot to prevent splitting. Dress the blade end of the handle with a wood rasp until it fits in the axe's eye. Mix some epoxy cement and coat the wood before driving it home. It is unnecessary to wedge the handle to the head, as epoxy literally welds the wood to the metal.

To sharpen an axe, make a holder from scrap lumber, such as the one shown in the illustrations. Get a new, 10-inch mill file, and fit it with a handle and a leather safety guard. Lay the axe in the holder and place one foot on its handle. Dress the cutting edge of the blade with the file, angling the strokes so the file barely scrapes up across the bulge of the eye. Such filing, using long, straight strokes, gives the correct taper to the cutting edge. If there are nicks in the blade, continue filing until the worst ones are removed, turning the blade frequently so that both edges are dressed equally.

The filed edge will feel ragged to the touch, so hone it with a hand-held, round, sharpening stone. Apply the stone to the cutting edge with a circular movement until all burring is removed. The axe is now sharp enough for general use. Too much work will draw the edge too thin, and the blade may chip if you chop into a hard knot.

After filing, a circular motion of stone will hone final cutting edge

Make paper pattern for sheath, then transfer onto leather, cut, and lace

For safety's sake, and to protect a good blade, no axe should go unsheathed. If the sheath for your axe is worn and ripped, open the seams and flatten it for a pattern. Cut a new one from heavy saddle leather and fasten it together with copper rivets. Install a heavy-duty snap fastener on the flap.

Most campers use an axe only for splitting wood. A box saw is satest for reducing logs and limbs to fire length, and replacement saw blades are inexpensive. Measure the length of the old blade, and obtain a new one at a hardware or sporting goods store. After installing it in the frame, take a blade-length piece of garden hose and split it lengthwise. Slip the cutting edge of the blade into the slit. Hold the hose onto the blade with two or three pieces of heavy string. Another good protector is a piece of 1x2-inch wood, with a deep sawcut running lengthwise in the 1-inch edge. Drop the blade into the slot, and tie together with a pair of leather thongs.

You can make a heavy saddle-leather protector for the saw which will match your axe sheath. If you make another sheath for your belt knife, you'll have an entire matched set. Get as fancy as you want with such sheaths; try your hand at some simple tooling to really dress them up.

Your sheath knife needs regular touchups to keep it the sharpest of all your edged tools. Hold the knife, sharp edge up, under a good light and sight along the blade. If there are shiny spots, or a continuous shiny line for the length of the cutting edge, the blade is dull. A sharp edge will always appear as a dark, thin line.

You need a two-sided carborundum stone of finer grit than you use for your axe, and a round, palm-size stone is the best choice. Lay the knifeblade flat on the rough side of the stone, then lift the spine of the blade about 20 degrees. Draw the cutting edge across the stone toward you, as if you were shaving a thin layer of the stone's surface. After several strokes on each side of the blade, repeat the operation using the smoother side of the stone. Again examine the blade under the light. Any shiny spots will tell you where more stonework is needed. When the shiny spots are completely eliminated, the knife is sharp. For an extra keen edge, obtain an "Arkansas stone"; a very fine grained stone nearly marble smooth; and hone the blade on it.

As a final test, hold a piece of fairly heavy paper with its edge toward you, arid slice into it with the knife. If the knife glides easily toward the center of the paper, cutting instead of tearing its way, the tool is sharp enough for any general use — except to shave your face. Further light honing will even achieve this degree of keenness.

By the time you've finished all this, the winter snowstorm will likely have blown itself out, and you can store the sharpened tools with your other camping gear. THE END

This is the Old West Trail country, big and full of doing. Stretching from one end of the setting sun to the other, this inviting vacationland will ever be the place for your family to go adventuring. Here, the horizon-wide scenic vistas defy description. The trail is a series of - modern day highways, mapped out by state travel experts. Look for the distinctive blue and white buffalo head signs which mark the Old West Trail. Sound inviting? You can bet it is! Go adventuring on the Old West trail!

For free brochure write: OLD WEST TRAIL NEBRASKAland State Capitol Lincoln, Nebr. 68509 Name Address City State Zip 14 NEBRASKAland FEBRUARY 1972

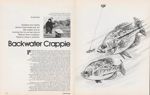

Backwater Crappie

by Jon FarrarWayne Steinbraugh, foreground, and son Roger know ways of river coves. But trickery of crappie is mystery as bait disappears

Exploding from starting blocks of wind-swept port, two Blair anglers race an Incoming front for one last crack at Missouri River's scrappers. Result is a foray to remember

PRISMATIC REFLECTIONS from a brilliant, noonday sun danced impishly across the choppy bay despite bitter cold and a healthy northwester. The sky was clear, but Wayne Steinbraugh and his son Roger were working against time as a threatening cloud bank appeared on the northern horizon. It was a race with the weather. For the Steinbraughs of Blair it was a last chance at what had been two weeks of unusually good crappie fishing. The 25-horse engine spurred to action, and pushed the 18-foot flatbottom boat toward the pilings protecting the bay from the rolling Missouri River beyond. Canting to port, Wayne swung the craft upstream. Years of hard-earned knowledge of the river's ways made the operation routine.

Eyes watered and faces burned as the father-and-son team sped into the wind. Four more miles separated them from the protected backwater. Duck and goose blinds dotted every likely looking spot along the shore. A deep-bowed boat moored on the opposite side of the half-mile-wide bay suggested that at least one bunch of sportsmen had ducks-not crappie —in mind. There was little doubt that ducks were more likely choices, but this would be the last chance with the rods. Duck hunting would have to wait.

The water was choppy in the wide bay, but the narrow neck beyond appeared reasonably calm as the craft gobbled up the distance to the crappie hole. Then the whole operation went amuck—literally —as the boat drove solidly onto a hidden mud flat. Wayne had suspected the river had dropped since his last trip a few days earlier, but there was no way of knowing just how far. During other trips, the boat had slid smoothly over the bay, but now the water was only inches deep in places.

Breaking out oars, the determined anglers pried their way off the flat and, for the next 15 minutes, poled their way back into the deepwater neck. Finally, the outboard roared to life again and they covered the last stretch.

An 18-foot boat and a 25-horse engine put together basics for cane-pole adventure. All that remains for success is a lot of luck, a bit of savvy

Even though Wayne, a sporting-goods dealer in Blair, had a storeful of fishing tackle available, both he and Roger used the most basic, and for crappie the most effective, gear-a cane pole. Rigged with nylon line slightly shorter than the pole, a No. 4 hook, split shot, and a pair of small bobbers, they were ready for action. Since any point in the hole could be reached from the boat, the nine-foot poles worked well.

Action raged the first 15 or 20 minutes, even though the sizes of the fish were disappointing. During the previous two weeks, Indian-summer crappie fishing had been excellent. Wayne and several of his fishing cronies had made numerous trips to the same 3 or 4 holes, and each time had returned with 20 to 30 crappie running from 1 to 1 1/2-pounds. Anything below the pound mark was unceremoniously returned for another year of growth. But now the action tapered. Whether it was because of the lateness of the season or a slacking off of recruitment from other parts of the slough was anyone's guess. Most of the crappie hit three-quarters of a pound, with only a few weighing more than a pound. Wayne held the edge as the two battled in unspoken competition.

Occasional flocks of mallards milled overhead, and the anglers enjoyed a ringside seat as they watched hunters in action. A twinge of envy hit the anglers as they watched several flocks of mallards circle and set their wings over the convincing spread. At the last minute the birds flared, two or three dropped, and seconds later, the reports drifted back. But, before long, the crappie-feeding spree erased all thoughts of hunting. Smaller crappie in the half-pound class became a nuisance as they consistently robbed minnows. Finally, the hole petered out and Wayne cranked up the outboard. A quarter of a mile away he cut the engine and let the boat drift into a second, promising hole.

Tying their boat to the leeward side of a beaver dam which extended to the middle of the channel, the pair baited up and tossed out. But success was not theirs this time. Trying various depths and locations, they enticed not a single fish.

Wayne broke out his bait-casting rig, tied on a silver, weedless minnow with a pork rind trailer, and flailed (Continued on page 60)

Fish are where you find them. For Roger, opposite page, Wayne, above, dank depths are bonanzas

Calm water of sloughs, above, is an idyllic setting. But best part is threading fish

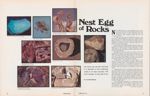

Nest Egg of Rocks

Fortification agate under black light

Lake Superior agates

Blue agate with common botryoidal (grape) surface

Blue agate slabs with red and black internal markings

Slabbed blue agate showing typical coloration and matrix

Dendritic (moss) opal

Opalized and silicified wood

Fairburn agates

No stone can be left unturned if a devotee of this collecting craze is to reap success. The hunt, though, is only half of fun

NOT EVERYONE gives a lot of thought to rocks, but to some people—those initiated into the fine but often strenuous hobby of rock collecting —they are among the most notable features that this old world has to offer.

As with any other type of hunting, the quarry is the thing. And, whether digging in a quarry or sandpit, through glacial remains, or surface collecting along stream bank or hillside, the quest is much the same. A wide variety of gemstones, ornamental stones, and other attractive materials are here for the taking.

Some rocks were formed within the state, but these are of fairly recent origin. Several million years ago, however, Nebraska was the recipient of huge shipments of older rocks. These came from deep within the earth after mountain-forming upheavals.

Mountains to the west were one source, with rivers washing rocks down into valleys here. Glaciers were another source, pushing and carrying debris in from the north and east. These latter deposits, however, are restricted much to the eastern third of the state, while all sections received the influx of the water-borne materials.

Comparatively unexplored by rock collectors, Nebraska now has areas virtually statewide where fossils, minerals, petrified wood, and gemstones are abundant. High-quality specimens are liberally sprinkled on the ground in some areas, and are pumped up by the ton at sandpits. They also appear in excavations in much of the state.

Although some sections of Nebraska offer better pickings than others, there is potential almost everywhere. Among the most productive are the far northwest corner, belts along most rivers, especially the North and South Platte drainages, and rock quarries and other diggings in the east. Locations of the glacial deposits are less predictable and stones are generally of mixed sizes, but they include Lake Superior agates, which are usually distinctly banded in bright colors.

Few rockhounds specialize in a particular material. In fact, the opposite is usually the case —they seek as many different kinds of rock as possible. Indeed, many rocks are beautiful things, with fantastic design and coloration. Few have high (Continued on page 57)

FEBRUARY 1972 21

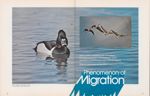

Phenomenon of Migration

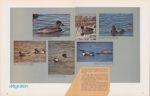

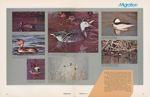

Drake ringneck, unlike lesser scaup, has white rings on bill and dark back

Throaty voice, large size, and unique markings are Canada goose characters

The Missouri River draws thousands of snow and blue geese during the autumn

HONKING AND QUACKING as if there were no tomorrow, thousands of ducks and geese descend on Nebraska. They come like crimson sumac leaves on a fall breeze. Sailing out of the northern or southern skies, depending on the season, they migrate along the heavily traveled Central Flyway.

The ancient mysteries of waterfowl migration fascinate the mind of man. But, for the most part, reasons for this age-old spectacular remain secrets.

Nebraska's fall migration kicks off during the dog-hot days of mid-August when blue-winged teal and pintails begin moving into the state. With the crispness of fall just a few feedings away, thousands more ducks and geese soon follow. In all, 21 species of ducks travel over Nebraska during their annual, southward treks. And, one webfoot— the mallard —often terminates its journey here.

Nebraska is host to six species of geese on the migratory trail. These are the snows and blues, the common Canadas, the lesser Canadas, the white fronted geese, and Hutchinson geese. Ross geese are also sighted from time to time.

While migration itself remains a puzzle, origins and destinations of many waterfowl species have been confirmed by game specialists.

Theories on how waterfowl finds its way run the gamut from claims that they travel by way of landmarks to flying according to the stars. Whatever the case, most waterfowl begins its southward flight from Canadian Provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta, terminating in the southern gulf states and Mexico. An exception to this general rule is the blue-winged teal that wings all the way to South America for its winter vacation.

Black wing tips of snow goose mark it from swan, its smaller bill from pelican

White around eyes and behind the bill mark this immature as a ring-necked hen

Male's white cap and both sees' white patch on forwing mark the widgeon

Our smallest dusk, the green-winged teal is not so colorful and the fall

Not a true duck, the coot or mudhen is marked by black body, white bill

This redhead's more rounded forehead differentiates it from the canvasback

Sometimes called spoonbills, shovelers are noted for their Durante-size bill

Like most things, waterfowl identification is easier said than done. While goose identification is less complicated, few sportsmen can quickly memorize the identifying characteristics of 20 or more duck species, and then apply this knowledge in actual hunting situations.

Probably the most important factor in duck-identification proficiency is a bona fide desire to attain it. Nebraska's colorful migration lends itself perfectly to an attack on this challenging task. Thousands of pintails and mallards, as well as many other species, are easy prey for the viewer. The sheer number of ducks, coupled with the fact that they are not scattered by hunters, simplifies observation.

Barred belly, light patch at base of bill distinguish white-fronted goose

White bars bordering blue wing patches and orange feet characterize mallards. Redheads, below, are in short supply

Since the mallard and pintail are the state's most populous ducks, the beginner is well advised to master these two first. Dedicated field study, complemented by book study, will soon pay dividends as the novice learns flight characteristics, feeding habits, landing and takeoff mannerisms, and other telltale hints for each species.

It will soon fall upon the newcomer to differentiate between diving ducks (those who frequent large bodies of water and dive deep for food) and puddle or dabbling ducks (those that frequent shallows water and literally dabble or bob for food). The observer will automatically begin to watch for habitat, color, action, shape, and even voice of all the waterfowl he observes. Each is a great step in its own toward becoming proficient in duck identification.

With this information, the new duck enthusiast is on the road to success via the process of elimination. Upon sighting a flock of ducks, he will immediately know if they are mallards or pintails. If they are neither, nor divers, then he has automatically narrowed the field to a few remaining puddle-duck species.

As more and more hours are spent afield, the duck observer will gradually become more adept at differentiation. The speculum, or colored wing patch, is generally iridescent and bright on puddle ducks, a telltale field mark, while the diving ducks' speculums are less brilliant.

Eclipse plumage on waterfowl often sends even old-timers of the know-your-ducks club into a tizzy, and rightfully so. After breeding, drakes of almost all species moult and lose their colorful attire. Consequently, for about a month, drakes strongly resemble the females. Generally speaking, scattergunners afield will find the majority of adult drakes in full color by the time shooting seasons are underway in Nebraska, while many of the juvenile drakes will still be awaiting full-color dress. It is virtually impossible to distinguish a drake in juvenile plumage from an adult female in flight.

Spring migration begins with pintails which flock into Nebraska, eagerly awaiting winter's release on lands farther north. They gather wherever open water is available. By late March, the spring migration peaks with a tremendous population. Then, as cold weather subsides farther north, the waterfowl moves on to breeding grounds. By the first week in May thespringshowisusually finished.

Drake goldeneye has a distinctive white patch in front of eye. Hens are usually with drakes

The white-eyed, hen wood duck seems drab in comparison with the multi-colored drake

Pintail to some, sprig to others, its streamlined profile is one of a kind

Crescent marks blue-winged teal in spring, blue wing patch in the fall

Not a duck, the pied-billed grebe or hell-diver is protected from hunters

Shoveler, front, canvasback, center, and cinnamon teal share same waters

Dark colored body and white head are obvious features of blue goose

Though often called fish ducks, these mergansers are not in the duck family

Drake buffle head is striking black and white is its nuptial plumage

Not so colorful in their fall plumage, ruddy duck's behavior is clownish

However, many ducks as well as a few geese stay on in Nebraska to raise their families. Blue-winged teal are most partial to the state, with up to 50,000 birds remaining here to nest in a prime year. All species included, Nebraska's breeding population often surpasses 125,000. Other species choosing to nest here in order of frequency include the mallard, gadwall, pintail, and shoveler.

Nebraska's spring migration is a spectacular phenomenon. And, while waterfowl faces a rocky road for survival, mankind's concern for these majestic birds offers strong assurance that they will never be lost. THE END

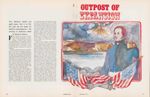

Outpost of Expansion

Fort Atkinson lasted just eight years. But in its life, the post set the stage for history's extravaganza — the winning of America's West

FORT ATKINSON was first. And, like many things examined in retrospect, it could probably be called a mistake —a fluke in which passion pre-empted reason. Neverthelsss, the post was the only military reservation west of the Missouri River in 1819 and, as such, constituted the first community in what would ultimately become the state of Nebraska.

Congress defended the fort's establishment as a means of keeping warring hostiles at bay and of asserting American influence in the West's British-dominated fur trade. But the soldiers stationed there must have berated the project as simply an experiment to find out whether white men could survive on the fringe of civilization. With Fort Atkinson's record, both factions were right to an extent. The military presence kept Indian trouble to a minimum, and etched the United States mark in the West while the officers and men of the new fort died like flies.

Fort Atkinson's story actually dates to some 15 years before it was founded. In 1804, Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark pushed up the Missouri River to explore the newly acquired Louisiana Purchase. Clark, in his journal of that year, commented on a site in present Nebraska "well suited for a trading establishment or fortification". But, for more than a decade thereafter, Council Bluffs, so named because of the explorers' meeting with area Indians, lay idle. The fledgling nation, less than 50 years old, was too busy fending off the British in the War of 1812 to worry about protecting the Western frontier. Besides, with nearly 300,000 men committed to that conflict, there probably weren't enough soldiers left to garrison a distant post. Three years after the war ended in 1815, however, America began to make plans for westward expansion. So it was that in 1819, Secretary of War John C. Calhoun cut the orders which created the Yellowstone Expeditionary Force.

Calhoun and Congress envisioned a string of three forts from the Yellowstone River in Montana to the Mandan Village, now Bismarck, North Dakota, and Council Bluffs about 15 miles north of the presentcity of Omaha. With such installations, Indian movements could be monitored and the British would know that the United States was in the West to stay. It was a grand plan and no expense was spared. Two crack army units, the Rifle Regiment and the Sixth Infantry, were selected. The former was composed of first rate marksmen, and the Sixth, recruited primarily in North Carolina, had earned the sobriquet "The Fighting Sixth" for service in numerous engagements. They were the best the army had to offer and they were to carve a niche for the United States in a West that had formerly belonged to trappers, Indians, and the British. Selected to head the expedition was a war veteran, Colonel Henry Atkinson, who, though he was not a West Point graduate, was rapidly establishing himself as an officer of note. So, when Atkinson took command of his troops at Plattsburg, New York, it seemed the venture couldn't fail. What lay ahead, though, was far from the expected glory. Unknown to Atkinson and his troops, starvation, disease, and utter discomfort lay ahead.

34

Slowly, the past is coming to light as relics like brass eagle, spoon, padlock, and flintlock are turned up after being buried for a century

Historical Society crews continue work at site. Discoveries like a brick basement are vital if model is to become accurate reproduction

Everything went smoothly from Plattsburg to St. Louis. At the Missouri community, well laid plans felt the jolt of things to come. The quartermaster was deeply in debt to the Bank of Missouri for supplies he had purchased for the trip and the new post. His position was so precarious that when the stores were to be put ashore for inspection, he anchored the boats on the Illinois side of the river and refused to move, fearing attachment if the provisions touched Missouri soil. The army wasn't happy about the situation, but its inspectors finally crossed the river, completed their task, and returned, grumbling all the way. So far, the expedition was still intact.

In the rough-and-tumble military of yesteryear, soldiers usually got where they were sent on foot. For the Yellowstone Expedition of 1819, however, steamboats were provided in keeping with the grand scale of the venture. They were fine as long as they lasted. In July, the troops were not far out of St. Louis when their two steamers cashed in. All that was left was to transfer the supplies to keel boats and cordelle them up the churning Missouri.

It was the fall of 1819 when the troops finally arrived at Council Bluffs. Immediately, they set about establishing a post where they could spend the winter. Their stores were soon depleted, however, and as cold and wind pounded the post again and again, more than 160 men died of assorted diseases —scurvy and fever claiming most of them. And, if winter was bad, spring was worse. As the weather warmed, snow melting at the headwaters of the Missouri and along its tributaries turned the already cantankerous waterway into a raging giant. What had become known as Cantonment Missouri was built on the flood plain, and soon became just so much driftwood as the river ripped it apart. Desolated but determined, the troops picked up what they could and looked around for a new, safer place to relocate. A rise about 11/2 miles south of the first location was selected, and the troops set about rebuilding their home.

It may have seemed so, but the men of Cantonment Missouri were not forgotten in Washington, although it may have been better if they had been. In 1820, a Congress faced with depleted funds took a second look at the Yellowstone project and scrapped all but the existing post. Then it cut appropriations, leaving the venture high and alone on a bluff overlooking the Missouri River, its destiny extremely uncertain.

Colonel Atkinson, in the meantime, had been kicked upstairs to Brigadier General in charge of the northwest frontier. Filling his post as commander at Cantonment Missouri was Colonel Willoughby Morgan, though in the years to come, command was to change frequently. Morgan soon found that the troops had a lot of free time on their hands and ensuing boredom led to trouble. So, with stores short and a lot of labor on hand, Morgan decided the post should try its hand at farming. What was perhaps the area's first serious effort at farming began on the alluvial heights of the Missouri River banks. In January 1821, the post had progressed sufficiently to be renamed Fort Atkinson, and part of the reason was probably its agricultural statistics. By the end of the first growing season, the troopers had shucked 12,000 bushels of corn and had more potatoes and garden vegetables than they could eat. The second season yielded 15,000 bushels of corn and the third produced 20,000. Agriculture proved so lucrative that before long the soldiers were also running 300 head of beef cows and 100 milkers. All in all, life on the frontier was looking up, but not necessarily militarily. One visiting officer, of which there were many, reported to Washington that too much time was spent cultivating crops and too little was dedicated to military pursuits. That communique diminished agrarian zeal only a little, but it did return the garrison to the straight and narrow of military practice.

After its original washout, Cantonment Missouri's life as Fort Atkinson began to take on the lackluster doldrums of typical military life on the plains. Duties and formations began with reveille at sunrise and continued until eight o'clock in the sumner and nine o'clock in the winter. Just to insure that none of the men decided to seek excitement (Continued on page 54)

A Spirit Unique

Handicapped Lincolnite calls his set of wheels a glorified wheelchair. Whatever it is, rig provides new lease on outdoor life

LINCOLNITE BILL GILMORE is an outdoor fanatic. Fishing, boating, hunting, camping—Bill loves them all. Bill is an ordinary Joe in the fraternity of outdoor buffs except for one thing —he's partially paralyzed from the waist down.

A native Cornhusker, Bill grew up on generous servings of outdoor fun. As a youngster, he was just the type to fall in love with squirmy worms, cane poles, and red-and-white bobbers. The romance of the great outdoors imprisoned his heart forever. But then, in his early teens, Bill was afflicted with polio and lost the use of his legs.

"I guess it's how you look at it," Bill says. "A guy in my situation could just give it all up and forget it. You can bet that would be the easiest thing. But that's not for me, not in a million years. I love the outdoors —boating, fishing, camping. I haven't missed a pheasant season since I don't know when, and I go rifle-deer hunting, too."

How does Bill participate in so many outdoor activities when he can't walk? It's a delicate combination of desire, determination, and action. Stubby, concrete-gray crutches provide mobility.

A close friend of Bill's confides that 99 percent of Bill's outdoor activity is accomplished through sheer determination. Without this honest desire to be involved, Bill would probably never breathe fresh, country air.

Two years ago, an acquaintance of Bill's suggested he look into the possibility of buying an all-terrain vehicle in order to give him a better shot at the outdoors. Bill took the advice and began checking into various ATV's on the market. The looking led to buying when he found one he thought would serve his needs. According to Bill, the all-terrain vehicle, a Scrambler, is one of the best investments he ever made.

While most ATV's increase man's outdoor pleasure and add to his convenience, Bill's machine provides him with the very basics of mobility in the field. The ATV has reopened his personal relationship with nature.

"The Scrambler has really been a blessing for me," Bill emphasizes. "Before, when I went pheasant hunting I could only block. But now, I can really get in there and participate. It puts me so much more in touch with the sport as well as with nature itself."

An attorney employed by the Nebraska Department of Agriculture, Bill spends most every free weekend hunting during the pheasant season. The first year he owned his Scrambler he bagged more than 20 pheasants, an impressive record under any circumstances. And, even though he doesn't always score, Bill enjoys each outing thoroughly. To be afield is a reward in itself. Whether he gets one bird or his limit, you can bet he'll be right back with the same enthusiasm the very next chance he gets.

Bill's six-wheel ATV takes him almost anyplace he wants to go. He tows it behind his car on a nifty, tip-bed trailer and can unload and load the machine in seconds. Pulling a pin at the front of the trailer makes it tip backward, and the Scrambler rolls off onto the ground. The Scrambler is loaded by simply driving it back onto the trailer. When the bed tips forward the pin is replaced.

For years, Bill Gilmore hunted and fished on crutches. Then, an ATV game him new dimensions

Whether hunting with companions, as in above photo with writer Amack and friend Charles Gove, or alone, Bill has a new freedom with motorized mule. He worried about vehicle's effects on environment, but six wide tires distribute the weight

"At first I was skeptical of what the vehicle might do to the countryside from an environmental point of view," Bill adds. "I am aware that many types of recreational vehicles are hard on the environment, and I wanted to be certain I picked a machine that would not damage the land. In giving the Scrambler a test drive I discovered that it scarcely left a track. This is because the vehicle's weight is distributed over a large area and doesn't dig into the ground."

Last fall, Bill tackled his first rifle-deer hunt utilizing the Scrambler. Everything came up roses as he successfully filled his permit with a nice two-point, white-tailed buck. Bill hunted in the Sand Hills region south of Valentine bordering the Niobrara River with rancher-host Neale Perrett and long-time hunting companion Victor Romans, both of Fremont. Neale and Victor also scored on hefty bucks. Because of his disability, Bill, like all other handicapped persons, can obtain at no cost a special permit from the Game and Parks Commission which lets him hunt and fish from a vehicle. However, the permit does not allow shooting from any public highway.

"I wondered if the vibration of the Scrambler might interfere with my aim while shooting a high-powered rifle," Bill explains. "I was shooting a 30/06 with a 4X scope. But, when I finally saw my buck, I guess I forgot about the vibration. The deer was standing in a neat little meadow about 160 yards away. Anyway, I took careful aim, fired, and killed the buck with one shot." Again, Bill gives credit to the large balloon-type tires, contending that they absorbed the vibration of the running motor, allowing him to aim accurately.

Bill's deer hunt last fall strengthened his appreciation for the Scrambler. The ability to enter woods, travel over hill and dale, or go anywhere else he wants opened the outdoors for him. While hunting the Niobrara, Bill flushed practically every type of game species that Nebraska offers the hunter, including both white-tailed and mule deer, antelope, wild turkey, pheasant, quail, ducks, geese, squirrels, and rabbits. He hunted the tops, bottoms, and middles of canyons —areas he (Continued on page 57)

With shelter dwindling before the march of progress, much wildlife is left out in cold

Cover come lately

All too often, wildlife perishes through man's apathy. But a chance is at hand to make amends

Since at least one blizzard will strike phesants, cover is vital

Tracks tell of life that goes on. One way to insure it is to provide habitat

Limp grass lying flat under snow will not help. Vegetation must create roof

NEBRASKANS have seen the appeal: "Wildlife needs your help...join the Acres For Wildlife program". You may have wondered, though, what the program is all about. Briefly, it was developed three years ago to involve everyone in the preservation of wildlife cover. In Nebraska, landowners determine what cover conditions will be like. Non-land-owning individuals, however, are also encouraged to play a big part in Acres For Wildlife, with the emphasis on youth. Young people are asked to become "cover agents"-to enroll plots of valuable wildlife cover by selling landowners on the idea of preserving habitat for at least one year on a minimum of one acre. Some areas like shelterbelts have been protected for 20 or 30 years, and would continue to exist for years even without the program. In such cases, Acres For Wildlife agents use the program to express appreciation to landowners. In other instances, a good agent may be able to prevent needless burning or mowing, thus protecting some of the most vital areas —those offering good winter survival and nesting cover.

Why emphasize these types of cover? Most pheasants in Nebraska must endure at least one blizzard, and protective cover is the key to their survival during these critical periods. The disappearance of undisturbed nesting habitat is a limiting factor for the pheasant population in many parts of Nebraska.

In the fierce, white world of a blizzard, little of the pheasant's habitat is suitable for survival. Snow blankets everything except windswept hilltops and barren fields where birds cannot exist. Deep draws and smaller plots of heavy brush are clogged by snow that has blown in from the fields, closing such (Continued on page 62)

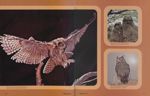

Cat with wings

LIKE THE SHADOW cast by a cloud sliding across the moon, so moves the great horned owl. On broad, powerful wings, he glides over the landscape, his oversize, yellow eyes piercing the darkness.

Suddenly and silently he swoops. A muffled squeal, and again he climbs skyward, a white-footed mouseclamped in his talons.

Cat with wings, winged devil—these names and worse have been applied to the horned owl. Even the mention of his name invites controversy. The issue is not new, for the Bible speaks of owls as unclean and associates them with death and destruction. Poets and writers have echoed this reference in literature of the past.

On a somewhat kinder note, owls have also been associated with wisdom. One anonymous writer expressed that idea m a brief poem:

A wise old owl sat in an oak. The more he saw the less he spoke; The less he spoke the more he heard. Why can't we all be like that bird?Eyesight 100 times better than man's aids largest of North American owls in sighting prey

Tawny-brown to buff plumage makes the bird appear much larger than he really is

Purloined nest is sanctuary for two offspring until their nineth week

Horns for which bird is named are really erectile feathers on head

Despite rumors, owl cannot see in total dark nor is he blind by day

Feathers of powerful wings muffle sound, giving almost noisless flight

What has caused man to fear and respect this predator? The horned owl is likely the ultimate winged hunter, as close to perfection as can be found in nature's chain of evolution.

Measuring 18 to 24 inches in height, his wingspan occasionally exceeds 4 feet. Soft, tawny-brown to buff plumage makes the bird seem much larger than he actually is—a mature horned owl weighs only two or three pounds.

Soft wing feathers muffle sound and allow the owl almost silent flight. This fact, together with acute eyesight and hearing, a powerful beak and sharp talons, make the horned owl the hunter he is.

With eyesight 100 times more acute than man's, the horned owl is especially adept at seeing in darkness. Tests have proven he can capture prey in light equivalent to that of a single candle burning nearly half a mile away. Despite rumors, however, he cannot see in total darkness, nor is he blind in daylight. In fact, he often hunts during overcast days.

With eardrums larger than those of any other bird, the owl's hearing equals his superb sight, often allowing him to locate prey by sound alone.

As if his physical superiority were not enough, the horned owl nests late in winter, months ahead of most other species. Often selecting a hawk's or crow's nest abandoned the previous year, the owl lays an average of 2 eggs which are incubated for 35 days by the female. The young remain in the nest for 8 or 9 weeks. During this period the owl takes advantage of early nesting. With wildlife populations mushrooming m the spring and the young of many prey species especially vulnerable, the owl is able to feed the owlets with ease.

Like other predators, the horned owl is an opportunist and readily takes what is available, including an occasional game bird or animal. This fact has made him a target for protest from many farmers and sportsmen. However, studies have indicated that 90 percent of his normal diet consists of rodents, making him a valuable servant of man.

Mystical and misunderstood, the homed owl still hunts in a cloak of darkness across almost all of North America. His faraway hoot and scream return even urban woodlots to wilderness. And, he waits for man to recognize his worth. THE END

NOTES ON NEBRASKA FLORA...New England Aster

Named for the Greek word meaning star, these garden plants gone wild annually decorate woodland edges, waterways, and roadsides across state

THE NEW ENGLAND ASTER is only one of approximately 200 different aster species in the United States. And, as if that were not enough, estimates range from 250 to 600 on species found throughout the world. Although they grow primarily in North America, they also appear sparsely in Asia, Europe, and South America.

Blossom size distinguishes the New England variety from its multitude of cousins. While those of its kin are generally smaller, the New England's flower grows to 1 1/2 inches in diameter. Color variation, however, is as wide as those of other asters in the Compositae family, ranging from blue to purple to crimson to red to pink to white, and all shades in between.

Scientifically known as Aster novaeangliae, the New England aster was brought to North America by European immigrants, and is probably a runaway from the first garden plants brought to this country. It adapted well to conditions here and is now a wildflower.

In North America, the New England aster is found from Quebec in Canada south to South Carolina and west to Colorado. The plant flourishes in rich, moist soil and a lot of sunlight, growing at roadsides, in open, undisturbed areas alongside streams, and along the fringes of woodlands.

The New England aster stands supreme amongst its cousin species. Its deeply colored petals with a primarily yellow center make the flower strikingly attractive. Its head has a radiating fringe of 40 or more colorful, strapshaped petals with the flower forming a dense cover over the upper half of the plant. Left to compete in grassland, however, the plant shrinks and may not flower at all. But, with no vegetation nearby, it grows to an average height of three or four feet, sometimes stretching six feet high. Tall as it is, it stands out like a beacon in the night. The plant is stout and shrub-like with small branches and single, lance-shaped clasping leaves.

A perennial forb, this aster overwinters as a stout, crowned rootstock with numerous, fibrous, branching roots. Since it is herbaceous, all parts of the plant above ground die in winter. New stems grow from the crown of the rootstock each spring. When warm weather arrives the plant produces myriad achenes. These are small, dry fruits with one seed each. The achenes hang from pappi which are downy or feathery tufts of bristles that act as parachutes for the seeds to be distributed far and wide by autumn winds.

Propagation may be accomplished with little difficulty. Ripe seeds may be gathered and planted. This method — generative propagation —may not produce the same colors as those of parent plants. Asters are insect-pollinated and cross easily. This is the reason for the large color and color-shade variation of the blossoms.

Another method —vegetative propagation — results in flowers which resemble the colors of parent flowers more closely. Plants with desirably hued flowers should be marked while in bloom. Since the crown grows side roots, it can be divided in early spring or late fall. The side shoots can then be used to produce flowers similar to the parent plant.

Attempts to establish the New England aster can be successful if careful attention is paid to suitable conditions— rich, moist soil and abundant sunlight. Once established, no maintenance is required. This perennial, whether in the garden or part of the natural landscape, greatly enhances its surroundings.

Asters are relatively unimportant as food for wildlife, although there are a few reports of mammals, songbirds, and upland game birds eating the leaves and seeds.

Often called starworts, asters derive their name from the Greek word aster, meaning star. They bloom in fall at the end of the growing season. In Nebraska they are found throughout the state, although they are slightly more prominent in the Elkhorn River's valley.

Merritt Fernald, in his book Edible Wild Plants of Eastern North America, published in 1958, states that asters are considered to be a palatable potherb for European tables. Young, tender foliage is cooked in two or more waters to bleed the bitter juices, and the resulting taste of the dish is similar to that of spinach.

Indiscriminate use of herbicides has hindered the growth of the New England aster to some degree, especially in roadside ditches. The use of plant-killing chemicals should be restricted to areas where their application is only absolutely necessary, thus allowing this species, as well as other wildflowers, to beautify the landscape. THE END

Collectors come and collectors go, but should rural Bladen hobbyist ever decide he wants out, he will need train to haul massive Deere herd away

From time to time, Ken Berns stokes up this oldsters, plows a bit

THERE'S AN OLD farming adage that goes something like this: Use it up, wear it out, and make it do. Seemingly, food producers around the world have been following that credo almost since time began. A dilapidated building, evidently unfit for further use, can always be revamped and pressed into service. Or, equipment that looks as if it won't make another trip around the field can be wired together and used. Sooner or later, however, all things come to an end. When that happens, all the farmer can do is invest in new equipment and relegate his older stuff to the junk pile. That's where Ken Berns of Blue Hill comes in.

To look at Berns, it's pretty hard to tell him apart from normal people. Yet, he has a hobby that sets him apart from most other farmers. He collects tractors; not any tractors, though-just John Deeres.

"I suppose I stick to Deeres because I'm interested in them. I grew up on one around the home place and when I started farming, I bought an old J. D. for my own use," he explains.

Berns began collecting the relics in 1961 when he broke into farming as a landowner. He was just out of the University of Nebraska and had settled on what is now a 600-acre spread between Blue Hill and Bladen. Augmenting his agribusiness, Ken began teaching in the Blue Hill public schools, then moved to Bladen where he still teaches math, science, and shop. About that time he began to take a further interest in tractors, and that interest was to take up a good share of his off-duty time in the years to come.

"I guess I really started collecting about 10 years ago, but it's only been during the last 3 years that I've really gotten into the swing of things." Berns' eyes fairly twinkle behind his glasses as he talks about his collection.

To date, Berns has some 52 John Deeres, ranging in vintage from 1923 to 1941, sitting in his farmyard. The 37-year-old teacher has another which he has bought but hasn't hauled home yet. That will bring the total to 53, not much of a record by most collection standards when other accumulations run into the thousands of items. Ken, however, has the edge on most collectors in that most of the tractors he owns actually run. A pretty fair country mechanic in his own right, Berns sees to that.

"To look at most of the tractors sitting in farmyards across the country, you'd swear they will never run again. You have to scour all the parts houses for miles around to find one that keeps outdated parts. Most shops, when a part sits for any length of time without moving, simply write it off and dispose of it. Either that, or they return it to the factory. What I need is an owner who hoards that stuff and who will part with it when I need something. That's the only way I can get my tractors to run."

Today it is almost taboo for a farmer who is changing tractors to discard the old one. Most newer models are (Continued on page 57)

OUTPOST OF EXPANSION

(Continued from page 37)elsewhere, five daily roll calls were routine. Those who didn't answer when their names were called —and there were quite a few —were usually AWOL. Desertion was so bad that 1 sergeant, 2 corporals, and 20 privates were on constant alert to retrieve strays. And, the troops went as far as necessary to carry out their assignment. In one instance, a Sergeant Ceders and his party were sent to Santa Fe to apprehend seven fugitives. Besides the military "police", any soldier, citizen, or Indian was in line for a $30 reward for bringing in a deserter.

Going over the hill was a good way to lessen the tedium of army life, but it was dangerous. Alcohol was much safer and, though there were many instances when both officers and enlisted men were censured for its use, it seemed to be the rule rather than the exception, for both to appear for duty soused to the gills. At one time or another, Captain J. S. Gray, Captain Charles Pentland, and Lieutenant Joseph Pentland, to name only a few, were all hauled up before the commanding officer for going on a spree. Excavations at Fort Atkinson have indicated that spirits were so important to the frontier military that a special building was given over to storing liquor. With alcoholism on the rampage, liquor rations were governed. Hoarding was against policy and he who received had to drink right then and there or reject his issue for the benefit of the company. There was little prudence in such an edict, however, since any trooper with the wherewithal! to quench his thirst could buy a jug at either the sutler's store, which was legal to a point, or at Welch's cabin or the dairy, both of which were highly illegal. Illicit sales slowed somewhat, though, when dairyman Ashael Savery and Welch of cabin fame were ordered away from the post.

On a brawling frontier, there was little attention paid to refinement, except for officers. Yet, the regimental band was on call for not only military serenades, but for company parties as well. The band was such an important part of post life that a special building was constructed a short distance from the cantonment proper so the musicians could practice without disturbing regular troop activity. Bandsmen awakened troops in the morning, signaled their work and breaks throughout the day, and put them to bed each night. A day without the regimental band would have meant mass confusion. But there was at least one aspect of Fort Atkinson in which the band did not participate. It came in 1823.

For years, Indians who called the midplains region home, had kept a careful watch on the whites, who, to them, streamed into the area. On June 18, 1823, word reached Fort Atkinson that a trapping party headed by William H. Ashley had been attacked with 1 3 of his men killed and 10, including Hugh Glass, wounded. Colonel Henry Leavenworth, post commander since 1822, closed the upper Missouri River to travel and mobilized his men. Companies A, B, D, E, F, and G were alerted and the command headed up the river toward the Arikara villages just above the Grand River in what is now South Dakota. Supported by some 400 Sioux allies, the approximately 200 men of the Sixth finally tracked the hostiles down in their own land. Then, the first military expedition against the Western Indians became somewhat of a farce. The Sioux began making raids on Arikara cornfields, and despite repeated pleas by Ashley, who had accompanied the command, lost interest in fighting. On August 9, regular troops skirmished with the Indians, but the only real action came the next day. Artillery fire raked the village, killing one chief—Gray Eyes —and cutting away the staff of the Medicine Flag. The Sioux continued their raids on the cornfields and on August 11 departed for home. Next day, the Arikara made peace and the expedition headed for Fort Atkinson, at least partially successful.

The Arikara attack heralded things to come, however, and the post was strengtnened. Throughout the summer and fall of 1824, unrest reigned and there were numerous reports of Indian murders. But the military reaction was conciliatory rather than aggressive, and orders came down to engage in (Continued on page 57)

Surplus Center

Special Note To Mail Order Customers All items are F.O.B Lincoln, Nebraska. Include enough money for postage to avoid paying collection fees (Minimum 85c). Shipping weights are shown. 25% deposit required on all C.O.D orders. We refund excess remittances immediately. Nebraska customers must include the Sales Tax. "Thin-Fin" Artificial LuresWhere to go

Fontenelle Forest, Canaday PlantTHE TRAIL affords a panoramic view of the Missouri River and its valley to the bluffs on the other side. Recently named one of 27 National Recreation Trails, and one of 11 National Environmental Education Landmarks, the Fontenelle Forest has the only nationally recognized trail in Nebraska.

In 1964, the forest was designated as one of the top 7 Registered Natural History Landmarks in the United States.