Where the WEST begins

NEBRASKAland

January 1972 50 cents

TWICE THE ACTION!

Fly-casting a stream for the biggest rainbow trout or stalking the corn rows for the wily cock pheasant, you can enjoy it all with a combination hunt-fish permit It entitles you to a full year of all-around action in NEBRASKAland, the "Nation's Mixed-Bag Capital". For just $8 and a small issuance fee, the combo permit is every Nebraskan's ticket to recreational activity unequalled anywhere. It's available from over 1,200 permit vendors across the state, so get yours today. Get your money's worth and more, for whatever your challenge you'll be sure to find it astream or afield in NEBRASKAland.

For the Record... TIME TO ACT

Citizens again have the opportunity to let their views be known as the Unicameral convenes this month. Several bills pending before the Legislature have the endorsement of the Game and Parks Commission and merit passage.

With the current concern about the state of our environment, Senators George Syas and William Hasebroock introduced LB 247 during the last session. It provides for a vote of the people to amend the state constitution, thus directing the Legislature to enact necessary legislation to guarantee a wholesome environment. Senators Syas and Hasebroock also joined Senator Ramey Whitney on LB 123 for a constitutional amendment to insure a citizen's right to bear arms.

Another bill dealing with the environment, LB 439, would require the licensing of custom applicators of pesticides and fungicides. Applicators would also have to take an examination to determine their qualifications before a license is issued. Since it is becoming apparent that the federal government will step into this field if the states do not act, it behooves Nebraska to initiate a program that provides for the needs of our state before federal legislation is forced upon us.

The Nebraska Game and Parks Commission has consistently supported legislation which is geared for the preservation of wildlife, and wholeheartedly endorses LB 619. This bill provides for the control of prairie dogs where necessary, but it also repeals previous harsh legislation calling for the extermination of these colorful creatures. Prairie dogs are part of our Western heritage and deserve some protection. In fact, their disappearance from large portions of their range prompted the U.S. Department of the Interior to place them, for a time, on its list of rare and endangered species.

Some extremely important measures are contained in LB 777. 1 he act updates the law dealing with the regulatory powers of the Game and Parks Commission as they relate to game and fish, lowers the age to hunt deer to 14 provided the youth is accompanied by a permit-holding adult, limits antelope permits during the initial application period to those who did not have a license the previous season, expands the Commission s powers to open or close a season in an emergency, and raised the cost of a nonresident annual fishing permit to $10.

Finally LB 864, like its predecessors, will again stir considerable debate. This is the "dove bill." In effect, this legislation would remove the mourning dove from the protected list thus allowing hunting seasons to be set. Amendments to LB 864 would provide a $5 dove stamp for hunters. This provision however, should receive a long, hard look, as it may weaken the intent.

These are a few of the bills which the 1972 Unicameral will consider this session. The Game and Parks Commission is working for their passage, but you, too, can help. A letter to your state senator might make the difference between failure or new law.

HABITAT CONSISTS OF: Cover, Food, Water, and Living Space, which are provided by Sunlight, Soil, Rainfall, and Plants. NATURE did a fine job of providing HABITAT until man began needing room for "improvements," such as Homes, Factories, Highways, Cities, Golf Courses, Airports, Pastures, and Crop Fields.

WHAT CAN YOU DO? Join forces with your buddies or act on your own, but do it now. The cover you save today will be more important than what you build next year.

Unless the cry is raised to stop it, thousands of acres of cover, roadsides for example, will be burned, sprayed, or mowed this year. Much of this destruction serves no real purpose.

You can also help a farmer return some land to permanent cover. You can speak up in favor of programs to retire unneeded agricultural land, like the soil bank program.

Provide Habitat... Piaces Where Wildlife Lives Join the ACRES FOR WILDLIFE PROGRAM For suggestions on how to take action, Write to: Nebraska Game and ParksCommission P.O. Box 30370 2200 North 33rd Street Lincoln, Nebraska 68503 JANUARY 1972

HUNTERS... ALWAYS ASK PERMISSION BEFORE YOU HUNT!

Remember that Nebraska State Law requires that you have the landowner's permission to hunt on his property. Take the time to ask for that permission. He will feel better knowing who his guests are and you will feel better too, knowing you are welcome.

Speak Up

NEBRASKAland invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to SPEAK UP. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters.-Editor.

BEAUTIFUL LAKE-"Thank you for the beautiful picture of Cottonwood Lake in the November issue of NEBRASKAland. We lived in Merriman from 1912 to 1926. Then, in 1919, we moved up to a Kinkaid claim 3 1/2 miles north of town.

Through the years, fishing was good in Cottonwood Lake. One year was the exception, though. An early freeze came and a heavy snow carpeted the lake. No one cut a hole through the ice and the fish smothered. That spring dead fish lined the banks of Cottonwood Lake. The lake was restocked, but there was no more good fishing for a couple of years or more. When it improved, we caught bass, crappie, and bullhead. We sorted the bass for size and salted down the larger ones for use in winter." —Mrs. J. M. Dart, Concord, California.

DIRTY WORDS-"Concerning Mr. Barbee's column entitled 'Why Hunt' (For the Record, September 1971), he used the words 'instant ecologists and protectionists' as though they were dirty words. If it were not for these so-called instant ecologists and protectionists, environmental protection would not be an issue today, Mr. Barbee would not have written his column, and his conscience would not have been aroused." —Kurt Ellison, Modesto, California.

WILD RIVER-"Recently John Grace and I took a canoe trip on the wild portion of the Missouri River between Yankton, South Dakota, and Sioux City, Iowa. Our trip lasted 2xh days and was a real pleasure. At least it was until we reached the congestion of speedboats from Ponca to Sioux City. We were also disappointed to see that many junked cars are still used to 'stabilize' the river banks — especially on the South Dakota side.-Tom Fitzsimmons, Omaha.

OOPS-"In 1904-05,1 was a cadet at the now-defunct Kearney Military Academy. My ambition was to be a bugler, but since the school had four very competent buglers who alternated their duties, there was no chance for me to be appointed. However, I did have an opportunity to perform one day when all four were off.

"I asked T. H. Elson, commandant of cadets, if I could play the calls the following day. He readily granted permission, and I was in seventh heaven. I had no alarm clock, but felt sure I would awake in time.

"Next morning, I looked at my watch and discovered it was just five minutes until reveille. Throwing on my clothes, I paraded up and down the halls of the dormitory and felt that never before had reveille sounded so beautiful. Then I proceeded to the main building, ready to shatter the morning air with my rendition of reveille again.

"To my surprise, a window raised in Old Main and the Head Master himself called out, 'Bugler, what time is it?'

"I replied, 'Why, it's a little past seven, sir.

"'You had better look again, bugler, then go behind the barn and kick yourself,' he said.

"To my chagrin, I then noticed that it was only a few minutes past six, and I had let loose with reveille a full hour ahead of time. I never lived down my blunder as long as I was at the academy." - Julius Festner, Phoenix, Arizona.

PICKLED-"We followed the directions published in one of your fish-pickling recipes exactly, but the bones did not soften. We used a six-pound carp —not scored - and vinegar bought in Nebraska City. We want to try again, so we would appreciate knowing where we went wrong."-C. E. Mincer, Hamburg, Iowa.

There were not enough details in the letter to pinpoint the problem. However, we imagine that the fish was not left to cure long enough. Like pickles, carp must remain in the brine for some time if it is to turn out. — Editor.

YOUNGTIMER- "I have read many letters in NEBRASKAland relating to early settlers. I sometimes think a person shouldn't write of his early days until he is old enough to have something to tell. Since I am only 75 years old, I will not dwell upon my experiences other than to say(Continued on page 12)

4 NEBRASKAlandWe've been doing a lot of things to make you want to fly Frontier. Big things, like Snow Club Service on many flights. Better schedules. And being on time. Little things like warm hellos to go with your Irish coffee. Fly Frontier. And see what you've been missing.

We'll help make arrangements for you. A rented car. A lift on a ski bus. Or, a room at a ski lodge. Just ask.

Frontier's Snow Club Service will fly you to, or near, more snow spots than any other airline.

Thirty-two great ski areas in Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, New Mexico, Montana and Arizona. Places like Aspen, Vail, Taos, Jackson Hole and on and on.

Our skis go in a special protective bag. Safe and sound...and free.

Our Seven-Day-A-Week Family Plan and Group Fares are real money savers.

Take advantage of our special ski tour fares. Or buy a standby ticket. We'll get you or your whole family to the slopes a little richer.

Call any Travel Agent or Frontier Airlines.

If you haven't been flying Frontier to where the snow flies, look what you've been missing.

Call of Winter The crunch of ice-webbed grass beneath a boot and the echo of expanding ice cracking across a vast and silent lake is portrayed in photography and prose

Critter Capers The antics of animals are caught on film, sometimes by design, but more often by accident. It proves that what a camera captures is not always what an eye sees

The Sky Is His Home Charles Carothers specializes in aerial gymnastics with his Pitt, biwinged plane barely 15 feet long. Mere flips and rolls are old hat—he does much more

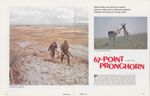

67-Point Pronghorn Two veteran hunters, having set their rifles aside, pursue wary antelope armed with bows and arrows. Long, wearisome stalks seem endless, but patience pays off

Cover: The Niobrara, one of the most picturesque rivers in Nebraska, wends its lazy way through the McKelvie National Forest at Nenzel. A bobwhite quail descends into brush on page 7. Both photos were taken by NEBRASKAland's Lou Ell.

Boxed numbers denote approximate location of this month's features.

BLITZ BLIZZARD

A hunter recalls unusual and unexpected visit to farm on first anniversary of storm

Fighting a blistering wind, we have no idea how far the distance to shelter

I WILL NEVER forget it. That blizzard during the New Year's Day weekend last year was the worst I have ever experienced. It was bad enough for people snowed in at home, but Gene Modugno, my hunting partner, and I were caught afield.

After pheasant or quail, we arrived at Pawnee Lake, four miles northwest of Emerald, Sunday at 7 a.m. There were already 2 inches of snow on the ground and the wind was whipping to 15 miles per hour. A pheasant burst out of a draw less than five yards from the car just as we got out, so we expected a good hunt. Weather forecasts had predicted no more than four inches of snow.

We started hunting north across a field. The snow cover made walking tricky and I stumbled over a hidden rock, sending 4 quail into the crisp, 23-degree air. They darted away before I regained my balance, and Gene was 200 yards west, too far away for a shot, but the small covey promised better things to come.

Wind velocity increased. We had been out only an hour, but during that time the gusts grew stronger, hitting 30, maybe 35 miles per hour. Reaching the end of the field, we worked our way back along a fencerow, hoping to flush a pheasant or two from under the cedars. No luck.

Crossing the section road, we continued south past Pawnee Lake's dam, disregarding the weather for the moment in our eagerness for success. Little did we realize that the wind was growing ever stronger, pushing us farther from the car.

Visibility dropped to an eighth of a mile. We suddenly realized our hunt was finished and turned back, upwind, toward the car. Coming to an abandoned shack near the dam, we rested for about 10 minutes on the leeward side, reaching the car half an hour later to find the motor packed with wind-driven snow. It wouldn't start. Wires must have shorted and the battery died with a forlorn groan.

The wind howled ferociously. We knew we must find shelter. Bracing ourselves for the worst and hoping for the best, we bailed out of the car and headed east along the section road. The biting wind cut right through our heavy jackets. Gene had no headgear, so I gave him my wool cap, pulling the hood of my ski parka over my head. My legs were numb and Gene complained of the sting from wind-blown snow on his face.

Covering about a quarter of a mile, we came to a ranch house that suddenly appeared from nowhere in the blinding, fast-drifting snow. What a relief! Marlene MacDonald welcomed us when we knocked on the door, asking what in the world we were doing outside. Severe storm warnings were being broadcast on radio, she said. We borrowed her car, drove the short distance to ours, and tried to start it with jumper cables from her battery, but it was dead.

It was getting to be dangerous outdoors, with winds gusting to 50 miles per hour. We realized that we were stranded and drove back to the MacDonald home. Telephone calls for emergency towing service proved fruitless.

I called my wife, Genny, in Lincoln, and told her of our predicament, and she was glad to hear that Gene and I were indoors and said that she and Ricky, our two-year-old son, were O.K.

But Gene's wife, Kay, was worried. Little Katie, their two-year-old daughter, had developed a cough and there was no way to get to the doctor's office. Fortunately Gene's mother was visiting. A registered nurse, she offered advice. The best thing Gene could do was tell Kay to call the family doctor and follow his instructions until after the storm passed.

There was nothing to do but wait. We couldn't move and the storm was getting worse. By mid-afternoon it NEBRASKAland became national news. Cars were ordered off all roads and motorists were advised to find shelter. The wind was blowing well over 50 miles per hour and more than 10 inches of snow had fallen. The temperature dropped steadily.

Our hostess was very kind and told us to make ourselves comfortable and stay until it was safe to go out again. Her husband, Larry, was stranded in downtown Lincoln only 10 miles away. The Dallas-San Francisco game was on television, so we watched the Cowboys take the National Football Conference title from the 49'ers, 17 to 10.

The world closed in when darkness came. There was nothing for Marlene to do but put us up for the night. The wind raced across the prairie until dawn, shaking the house continuously, and freezing the outdoors to a sub-zero chill.

Monday morning a neighboring farmer arrived with a blade-equipped tractor, opened the road to our car, and towed it to Emerald, leaving us there at noon. With no chance of getting the car serviced, we left it and hitched a ride to downtown Lincoln in a pickup after snowplows cleared one lane along the 6V2 miles of West O Street. It was 3 p.m. when we arrived. Traffic was at a standstill except on a few main arteries that had been cleared. Taxis and buses were inoperable.

Gene called home. His 65-year-old mother offered to try to make it downtown to pick us up —she's a spunky one —and by 4 p.m. she was there. She dropped me off two blocks from my house. I finally reached home by 5 p.m. The wind had died, and the only sounds in the ghost white city came from distant snowplows snarling their way through six-foot drifts.

My neighbors, of course, had talked with Genny and knew of my unexpected overnight stay at the ranch. They greeted me with questions and what they thought to be very funny remarks (I guess they were funny) about winter vacationing at Emerald, as they shoveled snow from their sidewalks and driveways.

Traffic began moving Tuesday morning, so Gene took me to Emerald to get my car, which started right up after a bit of defrosting. We got back to Lincoln none the worse for wear but much wiser in the ways of prairie storms. Both of us were raised in the North and are accustomed to driving in deep snow, but certainly not used to such wind. Next time we'll know better, even if the weatherman predicts only four inches of snow.THE END

JANUARY 1972 9

HOW TO: COOK WITH A THERMOS

Supper from a jug can be a mighty intoxicating experience, especially after long day afield

Brought to rolling boil, food then is quickly served from the bottle

DON NORTON set his bow in the corner of the pickup camper and shrugged off his camouflage jacket. "Tonight," he announced, "you get your supper out of a jug."

Tired and chilled, despite a beautiful, two-inch tracking snow that lay over the Pine Ridge, we had returned to camp empty handed after a day of deer hunting and I was in no mood to argue. "Suits me," I replied, jerking at a bootlace. "Go easy on the mix."

"That's not what I mean," Don countered, unscrewing the caps of a gallon-size, insulated jug and a quart-size vacuum bottle sitting on the fold-down table. "You need solid food."

"I'm ready for that, too," I grumbled, "What's with this jugbit?"

"The jug cooked the rabbit stew, and the vacuum bottle cooked dried fruit for dessert while we were ridge running," Don smirked. "Hasn't an old camper like you ever heard of cooking in a vacuum bottle?"

Up to that point I hadn't, but it was three bowls of stew later before I got around to asking the question: "How?"

"It's an adaptation of the old fireless cooker principle," he explained.

"Fresh food brought to a rolling boil on the stove, slapped into the jug fast, and capped quickly, continues to cook in the trapped heat. High-quality jugs work best because they retain the heat much longer than cheapies covered with only a thin layer of styrofoam. My cooking jug has an enameled liner, three quarters of an inch of firm foam insulation, and a metal jacket. It loses very little he^t in 6 hours, and remains steaming hot for 24."

"Isn't your phrase 'cooking in a vacuum bottle' a little loose then?" I asked. "What you've used is just a well insulated jug."

"Perhaps," he conceded. "Actually, when one wants smaller quantities of food, conventional wide-mouthed vacuum bottles should be used. Of course, the container should be completely filled so that no air space remains to bleed off the heat."

"What's the advantage, really?" I frowned. "Wouldn't it be simpler to open a can of beans and heat them?"

"Don't forget, rabbit stew doesn't come in cans," he said. "Fresh meat and vegetables always taste better than canned stuff. Just because we are camping doesn't mean we have to give up good food. Then, too, think of all the cooking fuel a camper can save by using the jugs. Take that stew for instance. In top-of-the-stove cookery, it would have to simmer for two or three hours. With the jug, it is simply brought to the first rolling boil. Then the stove can be shut off. We can hunt or fish without having to worry about the food being overdone, the pot cooking dry, or a fire breaking out. And, we have a hot meal ready for us the minute we get back."

Don shoved a knife and a small chunkof smoked ham across the 10 NEBRASKAland table toward me. "Cut this into half-inch-square pieces," he instructed. "We'll have jug-cooked ham and beans tomorrow night."

"Why the small pieces?" I asked.

"They need to be small to reach cooking temperature by the time the water boils. Both meat and vegetables should be diced for jug cookery. If the interior of the chunks are not up to boiling temperature, which they would not be if they were too thick, they simply keep absorbing heat after being transferred to the jug. That lowers the overall temperature below cooking level, and you end up with a raw dinner."

He emptied a cup of dry navy beans into a pan, added the diced ham, some ketchup, seasoning, and water to cover, and set it on the little stove. He filled the jug with hot water and capped it.

"The hot water heats the jug liner," he said, "so that no heat is bled from the food to be cooked."

"It's easy to see that jug cookery is limited to food that is boiled. What foods lend themselves to it best?" I asked.

"There's little limit," he answered. "Macaroni and noodle mixes are a cinch. Cooked breakfast cereals, rice and potato dishes, dried fruits, and the like are all candidates. Most of these absorb a lot of water, and may need a little room for expansion within the jug or bottle. Only experience enables you to judge the amount of space needed. I experiment with various foods at home to determine this, and of course another trick is to learn just how much water to use with each type of food so the proper consistency is achieved in the cooked product. In jug cookery, no water evaporates as it does from an open kettle, so this must be taken into consideration. Dried fruit, for example, must fill only half of the vacuum bottle, with water to the top. While cooking, the fruit absorbs the water and expands to fill the container. Stew, on the other hand, expands very little and needs no headroom. In fact, stew should be covered with as little water as possible to prevent it from turning into thick soup. At the outset, I always add what thickening agents are needed for body."

The beans and ham on the stove broke into a vigorous boil. Don dumped the hot water from the jug, quickly poured in the food and its liquid, and capped the jug. The whole transfer took less than 10 seconds.

"Those are the basics of jug cookery," he concluded. "Now, while tomorrow evening's meal cooks, let's talk about tomorrow morning and where to look for that five-point buck." THE END

Make Every Day a Little More COLORFUL!

POLLUTION

A not-so-pretty picture. Who causes it? Who is willing to help fight it? The Answer Is In Your Hands Nebraska is beautiful. Every litter bit destroys that beauty.SPEAK UP

(Continued from page 4)that I was born in a dugout on a homestead southwest of McCook.

"When I was 4, my Dad built a covered wagon and we traveled to North Platte, better than 100 miles by trail road. We more or less camped on the outskirts while Dad built a sod house on a lot he bought nearby. Times became very hard and he was out of work most of the time. Knowing Bill Cody, he got a job on the ranch in 1902. I was six and walked to the North Side school from the Buffalo Bill Ranch when I was in the first grade." —A. J. Stenner, Powell, Wyoming.

HERE'S HOW —"I am enclosing an article on how Nebraska City got its name. I hope you can use it in NEBRASKAland. — Eugene E. Lutz, North Bend.

How Nebraska Got Its Name It was many moon ago, and I was a small boy in a far-off country on the blue Mediterranean. One day as I lay on the beach watching the surf break on the shore, an old man came along, crying, "I need 20 men to go new world with me." Pretty soon 20 men came. Old man say to men, "Get axes and go to forest and cut down many trees to make big raft with mast for sail on it so we can go to new world.

Men say, we do.

Then old man goes to bank (he owns bank, is very rich) and says to man in bank, "Get me big sack of mullah to buy much land from Indians in new world." Then old man goes to grocery store and buys barrel of caviar, six bottles of wine, and many sandwiches, so will not get hungry.

Raft is all done. Men say to old man to get young woman for cook—is long voyage to new world. He do.

Old man say to me, "Boy, you be our cabin boy."

I say, I do.

Men load up barrel of caviar, six bottles of wine, and many sandwiches on raft. Old man, young woman who is cook, and me, who is cabin boy, and all men get on raft. East wind blows strong on blue Mediterranean, raft goes fast. Pretty soon see big mountain by sea. Old man say is Rock of Gibraltar. Pretty soon come to big ocean. Wind blows stronger, raft goes very fast. Pretty soon come to new world. See sign on beach—say is Miami, but see no hotels, only fat man on beach. Fat man say name is Jackie. Old man say he makes funny talk.

Old man say, keep going, soon get to smaller ocean. Men do. Old man say to men, look for big river. Men say, O.K., we do. Pretty soon men find big river. Old man say, take a right so we get on big river. Men do. But young woman, who is cook, says is afraid of big river. Old man say to men, look for smaller river. Men say, O.K., we do. Pretty soon men find smaller river. Old man say to men, take a left, so we get on smaller river. Men do. But old man don't like smaller river, is very muddy. Say to men, look for clean river. Men say, O.K., we do. Pretty soon men find clean river. Old man say, take left, so we get on clean river. Men do. Men take big drink, but water is very shallow. Pretty soon raft get stuck on sandbar. Old man say to men, carry six bottles of wine, barrel of Caviar, and many sandwiches to land. Men do. Old man say to me, cabin boy, take mullah to land. I say, I do. But young woman is afraid she get miniskirt wet. She say to old man, carry me. He do same.

Then old man say to men, build igloos, maybe bad winter is coming. Men do. Then old man say to men, plant potatoes for food. Men do. Old man likes French fries. One morning Jackie (that is young woman's name) is digging potatoes for dinner. Pretty soon see many, many Indians coming. She runs to old man's igloo. Ari (that is old man's name) she cries, many, many Indians coming, better hide mullah, and bring Tommy gun, maybe Indians scalp us—is very painful, then will have to wear wig. He do right away.

Indians stop, say "how" to Jackie. Jackie say, I don't know you fellers. Big Indian on spotted horse say, me is Chief Sitting Bull. Jackie say, who is Indian on yellow horse. Chief Sitting Bull say, is Chief Rain-in-the-Face. Then Jackie say, who is man with Stetson hat and white beard on big white horse. Chief Sitting Bull say, is Buffalo Bill, is Indian trail boss. Indians get lost without him, is very good man.

Ari comes out of igloo, say to Chief Sitting Bull, what you Indians want. Chief Sitting Bull say, see sign, say is Paradise. Indians don't like name, say should be Nebraska. Ari say, we vote. Buffalo Bill counts votes, but many, many Indians. Indians win. Chief Sitting Bull pull up sign, say Paradise, and put up big sign, say Nebraska.

That's how Nebraska get name. For me, will always be Paradise.

JOURNAL —"I have recently come into possession of a journal of a trip to California's gold fields via the Oregon Trail. The journal is by a group from Ray County, Missouri, who started from home on April 16, 1850.

"The party was composed of 15 men, wagons, and oxen, though others joined this train as it moved west. They traveled up the Missouri River to Iowa Point, and then westward through Fort Kearny and on to Fort Laramie. Approximately 50 miles west of that point, the journal becomes illegible." —Lester L. Joy, Stafford, Kansas.

Get aboard Kawasaki's all new Mach II, the 350cc, 3-cylinder TriStar from Kawasaki's galaxy of superstars for 1972. Then sit back and hang on while the Mach II happens to you! Outperforms any other 350cc motorcycle made, and most 500cc. Great acceleration, 45 hp, top speed over 100 mph. The styling is unique, with striking spoiler design of seat and rear section. It's tomorrow's machine, built for today's moving generation.

Mach II —first supermachine in its class. First in power. First in speed and acceleration. And first in the race for space. Take-off time is now. See Mach II now. Then join the set.

• Kawasaki launches another first: the TriStar Triple 350 • 45hp-maximum thrust for its class • Turbine smooth —with rocket thrust acceleration year of the Kawasaki

THE SKY IS HIS HOME

When not in the confines of his office, this Lincoln dentist can probably be found drilling holes somewhere in the air

MAN HAS come a long way since the day he stood atop a cliff, wistfully watching birds soar overhead and wishing there were some way to free his featherless frame from terra firma.

Nowadays, children seem surprised when they learn that man had so much trouble in those struggling, early years. In this age of supersonic jets and journeys through space, those puny efforts, when a man leaped off a cliff with a pair of wings strapped to his arms, seem almost unreal. But now, even the birds stare in disbelief as they watch man perform fantastic maneuvers in their domain.

One of those who specializes in such aerial gyrations is Dr. Charles Carothers, a Lincoln dentist. After a stint in military service, Dr. Carothers

It's a topsy-turvy world from the cockpit of a spinning, tumbling, competition airplane

Plane twists so fast, smoke trail is helpful in tracing aerial action

Small but potent, plane cranks

out moves that would

rip normal craft to pieces

Small but potent, plane cranks

out moves that would

rip normal craft to pieces

Including pilot and fuel, plane weighs 1,000 pounds

Ed Mooring, Wahoo mechanic, tends to repairs, checks, and maintenance

Takeoff requires only few hundred feet with thrust from 180-horsepower engine

found he didn't want to be totally earthbound, even after returning to civilian life, and there was little enjoyment in merely flying a light aircraft from one place to another. As a result, he eventually became interested in aerobatics, the performance of spectacular airborne acrobatics.

Now, using the third airplane he has bought for this purpose, Dr. Carothers is convinced he owns the best. Although small, the craft has amazing capabilities. It is a Pitt biwing, barely 15 feet long, with a 17-foot wingspan. At first glance, the bright red plane, with white stripes on the wings and along its fuselage, appears to be a novelty.

That impression doesn't last long, though, when seeing it perform. For precision flying, the diminutive one-seater really shines. It goes through snap rolls as quick as the snap of a finger and withstands stresses that would rip the wings and tail from inferior craft. The pilot, of course, must also withstand these stresses while putting the plane through its paces.

The image of a stunt pilot is that of a loud-talking, swaggering, scarf-swinging, devil-may-care rascal with dark, wavy hair and an Errol Flynn moustache. Dr. Carothers is different. He is tall and thin, speaks softly, is cleanshaven, and doesn't even wear a scarf.

"I want to stress that I am not a stunt pilot," he insists. "Basically, I perform specific aerobatic maneuvers or routines. It's precision flying at safe altitudes. Stunt flying includes dangerous, even foolhardy tricks, and I consider it stupid. Pilots who do that sort of thing don't live long, which speaks for itself, I think."

Many people consider all flying dangerous. Any time you can't step out and walk when the engine quits is dangerous, they say. Professional flyers, however, insist that flying is safer than driving a car. They claim that a light plane can land safely on almost any terrain in case the motor dies. Dr. Carothers is one of (Continued on page 54)

Rapid sequence of aerial gyrations is a startling sight for earthlings

Paper Chief

A half-breed never adopted by tribe, Logan Fontenelle still ruled behind the scenes

HE DIED too soon. Logan Fontenelle may have gone on to greater things, but his colorful, 30-year life was snuffed out in 1855. Half Omaha and half French, he was killed by warring Dakota Sioux, archenemies of the Omaha, while hunting in what is today northeastern Nebraska.

During the past century, history has treated Logan unfairly, calling him chief of the Omaha, a position he never held in the eyes of his mother's people. He was one of their leaders, true, but in order to be a chief, he would have had to be the descendant of an Omaha chief, or would have had to be a formally adopted heir. Logan missed out on both counts.

While the chief's title attributed to him is a misnomer, the title United States Interpreter is correct in all its implications, but this position is probably what led those who knew him well to call him chief after his death. While the image of this half-breed has been obscured so as to elevate him to a higher position than he actually held, there is no doubt he was an extremely influential person within the nation even to the point of being a de facto ruler of the Omaha after the 1846 death of Chief Big Elk, his maternal grandfather.

Son of Lucien Fontenelle, a French fur trader, and Meumbane, Chief Big Elk's daughter, Logan was born with a dual heritage. His grandparents were French. Members of high society in Marseilles, they left Europe after the French Revolution, arriving in New Orleans in 1800.

Living with relatives at first, they soon established a plantation near the city and became part of French society in the New World, living comfortably in the aura of New Orleans aristocracy at its height. Logan's father was born into this environment in 1803, the year Louisiana Territory became United States land through the Louisiana Purchase ratified by Napoleon Bonaparte, emperor of France, and United States President Thomas Jefferson. Then tragedy struck. The Fontenelle plantation was wiped out by a hurricane which took the lives of both grandparents. Young Lucien, however, and a baby sister were visiting an aunt in New Orleans at the time. This aunt was left with the responsibility of raising the two children. She must have been a dictatorial woman, one Lucien disliked, because at 16 years of age he ran away, leaving New Orleans for good. Accounts say he argued with her one day, got his face slapped, and decided to leave.

Working his way up the Mississippi and Missouri rivers on paddle wheel steamboats, he arrived at Fort Atkinson, an early military post 16 miles north of present-day Omaha, and soon discovered the value of fur. It didn't take long until he became a shrewd and highly successful trader between Fort Atkinson and St. Louis.

In 1823 an Indian agency was established at Bellevue, and the Omaha moved downriver to get farther away from northern, Dakota-dominated territory. Lucien mixed with them and two years later took Meumbane as his wife, thus bringing together under one roof two widely opposed life styles and setting the stage for Logan's birth in 1825.

The 1,500-strong Omaha were peace-loving, their warriors preferring to fight only in self-defense. Big Elk was a diplomatic chief, wise in Omaha tradition, but increasingly aware of the fact that his people must contend with the white man's influence. When Meumbane gave birth to his half-breed grandson, he envisioned the infant as a future mediator who would help the Omaha through their transition from outdoor, prairie existence to civilized life, and taught Logan accordingly.

Meumbane was intelligent and fond of her husband, but never forgot her Indian origin. Although she agreed to live in Lucien's house rather than in a tepee, she favored her people, (Continued on page 54)

18 NEBRASKAland

CONFLICT

Change for profit's sake or stability for survival's sake. These are issues over which factions are divided and the battle lines drawn

Preservation vs. Development The Environment vs. The Economy

EVEN THOUGH NEBRASKA lies in the heart of the United States, for the most part it has been on the fringes of environmental conflicts raging through the nation.

Today, however, the state faces three environmental issues which have become the object of considerable contention. They are popularly known as: 1. The Mid-State Reclamation Project; 2. The O'Neill Unit or Norden Dam, and 3. The Missouri River Channelization Project.

Although these projects are located in different parts of the state, they share common features. Each calls for alteration of a Nebraska waterway — the Platte, Niobrara, and Missouri rivers. The primary purposes of all three programs are basically the same—to benefit the state's agricultural community through irrigation and bank stabilization.

The three projects share the notoriety of controversy as each faces opposition from environmental groups which generally urge that the rivers and adjacent areas be left alone.

Only a few years ago, propositions such as these may have proceeded unopposed. But the words progress, change, and development no longer have the magical power to sway the public toward acceptance of environment-disturbing proposals. No longer are the pronouncements of federal and state agencies or industry-sponsored experts accepted without debate.

But the questions which these issues raise are not easily answered. Often, the facts which both sides espouse conflict with each other and with reality. Occasionally, emotion takes precedence over accuracy. Both factions feel they are absolutely right, with little thought given to opposing arguments.

Certainly these proposed projects are serious enough to deserve the careful study of everyone in the state. All three call for decisions—decisions which involve large amounts of money; decisions which may affect the lives and livelihoods of many citizens, and decisions which, once made, may be irrevocable.

Known officially as the Mid-State Division of the Missouri River Basin Project, the Mid-State Reclamation Project has been on the drawing boards for about 30 years now. As in other irrigation works in the state, it would consist of a diversion dam, storage reservoirs, and a system of canals. Located near Lexington, the dam would divert a large portion of the Platte River's waters into reservoirs from which it would be made available for irrigation.

In 1967, Congress passed the authorizing bill. Advanced planning has not been completed, however, and funds have not been appropriated for construction. At 1967 prices, the estimated cost exceeded one hundred million dollars.

According to promoters, including the Nebraska Mid-State Reclamation District, the

benefits would include the capability for irrigating 140,000 Platte Valley acres, some of the

nation's finest agricultural land. It is also believed the plan would help stabilize the water

table which, in some areas, has reportedly declined from 5 to 20 feet. Thus, the project would

offer opportunities for increased crop yields on

newly irrigated lands, and theoretically insure

that yields will not decrease on acres where

the water table is dropping. Proposed works

would also bring flood protection and recreational benefits similar to those now offered by

other Platte Valley lakes.

newly irrigated lands, and theoretically insure

that yields will not decrease on acres where

the water table is dropping. Proposed works

would also bring flood protection and recreational benefits similar to those now offered by

other Platte Valley lakes.

It is difficult, especially in Nebraska, to argue with any proposal which might improve the lot of the state's farmers. However, it is obvious that not everyone involved sees the project as a needed improvement, since a group which claims to represent the majority of the concerned farmers, Mid-State Irrigators, Incorporated, opposes the project. The argument has also been presented by project opponents, such as the National Audubon Society, that it seems inconsistent to spend millions of dollars to increase productive areas when the government continues to pay farmers to keep thousands of others idle.

Yet primary opposition does not concern agricultural or economic aspects of the project. Rather, it is what will or could happen to the Platte River and its associated wildlife habitat and recreation resources that bothers the majority of those who would like to see the scheme discontinued.

The portion of the Platte which would be affected, from 50 miles east of Lexington to perhaps the entire river, is a special part of Nebraska. The wide, shallow, multi-channeled river is a unique natural area of islands, sandbars, woods, and wetlands. Though the Platte is subject to natural fluctuations, it is feared that diverting its waters would leave it essentially dry for extensive periods throughout the year. The bars would grow up in willows and cottonwoods and thus reduce the channel's capacity to pass flood flows. This would so drastically alter the environment that it could seriously jeopardize the many forms of wildlife which depend on the river and its adjacent habitat.

Every year, more than 200,000 sandhill cranes, a wildlife resource of international significance, use this portion of the Platte Valley as a staging area in their migrations. If the Platte River were dry or greatly changed, the cranes might not stop, and Nebraska would lose wildlife assets which cannot be measured in dollars.

The area is home, temporary or permanent, for many other kinds of wildlife, according to the Wildlife Management Institute. Large numbers of ducks and geese use the shallow waters. Shorebirds and songbirds, deer and beaver, and a host of other species could suffer if the river were changed.

To the north, another controversy has taken shape. The O'Neill Unit, sometimes referred to as Norden Dam, is another Bureau of Reclamation-administered plan which brings up the same sort of conflict, with irrigation boosters on one side and defenders of the natural environment on the other.

The project calls for a dam near the town of Norden which would back up the Niobrara River, forming a reservoir 19 miles long. The pre-authorization plan for the O'Neill Unit, part of the Missouri River Basin Project, has been essentially(Continued on page 63)

Irrigators say Mid-State Project is a big factor in stabilizing ground water

Wild portion of Missouri River below Gavins Point Dam could be channelized

Proposed Norden Dam would inundate an area ecologically unique to Nebraska

The eye does not always see what the camera captures. Odd things sometimes happen when creatures are involved

Critter Capers

LOOK AT A spectacular wildlife photograph—the owl, wings outstretched and talons set, about to seize upon an unsuspecting mouse. Or, note the regal pheasant bursting from brush cover, head erect and wings straining for the sky. Such subjects, it would seem, can be portrayed in no way mother than as sculptured, elegant, and breath-taking poles. No way, that is, until you try to take such pictures.

Now you see me, now you don't says playful, great-horned owl

You don't think they originated the term "goose step" do you?

Lanky avocet thinks there's a snake in the grass somewhere

Or perhaps it is a great-horned owl, returning to his nest one dark night, who spots the waiting camera and demonstrates his imitation of Count Dracula.

Up, up, and away—those helicopters do no better than this old chukar

Photographer didn't hear patter of little feet inside his camera

With disappointment the normal fare for wildlife photographers, it is a wonder that so many people become enslaved in such pursuit. There mu|t be a reason. Perhaps it is thai nobody really likes easy success. Or it mm be love for an especially cantankerous camera. And, there is always the hope for a smashing failurfe. After all, one Count Dracula is worth a dozen wise, respectable owls. THE END

Necessity to Novelty

Pioneer Village at Minden still carries on crafts that settlers termed a drudgery

A century-old stitching clamp is part of Tom Jacob's shop

Faggie Benson's ancient loom is made of sod-house timber

HOUSEWIVES NOWADAYS may complain bitterly when their automatic dishwashers go on the blink, or when their fancy clothes dryers blow a fuse, but they certainly would get no sympathy from their pioneer counterparts.

About three-quarters of a century ago, there really was a need for women's liberation, but no amount of ballyhoo or sign waving helped. Self-sufficiency back then was a way of life rather than a motto for women's libbers, and it took a few inventors and mechanical dabblers to relieve them of their hardships.

What was done out of necessity then would make modern women blanch in agony, yet those old ways are not entirely forgotten. Lois Nelson and Maggie Benson are cases in point. Men are not totally out of the picture either, as exemplified by Tom Jacobs. These people are employed at the Harold Warp's Pioneer Village in Minden as colorful reminders of a day when money didn't grow on trees, and clothing wasn't bought in stores.

Amid thousands of pioneer curios, these three people bring to life an era nearly forgotten and little appreciated when common household items were made, not purchased. Lois operates a spinning wheel —that strange machine which turns wool into yarn. Processing a heap of raw wool right off the sheep's back into a sweater for an active pioneer lad required many tedious hours, but her efforts now amuse thousands of tourists.

Maggie pulled a lot of strings to arrive where she is — on the business end of a loom. What is now a pleasant job for her was once an almost formidable but everyday challenge for frontier mothers. Wearing apparel which could not be knit or crocheted had to be woven, and the family loom was the answer. While it did provide a sitting-down job, which (Continued on page 62)

Area wool becomes useful yarn with Lois Nelson at the wheel

Dick Turpin, left, trails after Clyde Storie over rugged ground

67-POINT PRONGHORN

Game warden and sheriff form search party for trophy buck in Nebraska badlands. Antelope wins Pope and Young rewardYoung bucks like these are forced from herds by old males during rut

Clyde's 13-inch-plus pronghorn won him national as well as state recognition

It was a mile or more from their position on top of the rim to the buck in the rolling basin below. Browsing on sage and other herbs, the pronghorn showed every indication of working the ravine long enough to permit a stalk and a shot from the ridge 20 yards above him. It looked promising —at least worth the effort.

A wide arc behind the unsuspecting pronghorn took the two men over rolling grassland that flowed away from the rocky rim they had just descended. Fields of exposed agate tempted the hunters, but antelope was the order of the day. The carefully planned route of the stalk was much more of a test after being viewed from another position. Every hill resembled the one that hid the buck. Several sterile stalks preceded the approach to the ridge above the feeding pronghorn. Spaced 40 yards apart, the bowmen crawled to the lip of the ridge. The accelerated pace of the stalk and the anticipatory flow of adrenalin quickened the pulse and heightened the excitement. Easing forward, inches at a time, through clumps of Western wheatgrass and over what seemed to be a carpet of prickly pear, they reached the top. With arrows nocked and mental reminders to pick a spot, the bowmen slipped into a crouch, then finally stood upright, ready to let fiberglass and feather fly.

Like so many stalks before, the episode ended without a drawn string. The buck had vanished, either spooked or lured another way by better browse.

Dick had hunted the Oglala National Grasslands north of Crawford for pronghorn with a bow several consecutive years. While shots had been plentiful, he had yet to tag an antelope. Last year was Clyde's first hunt for pronghorn in that area as well as his first outing with a bow.

Turpin claims the credit for sparking the sheriff's interest in hunting Indian style for pronghorn. Dick put his big-game rifle aside in 1957, but he has yet to miss a deer season, nor has a season passed without fresh venison in his freezer. While he prefers bow hunts because of the challenge of hunting at close range, Dick confesses that his main reason for hanging up his rifle was to avoid the crowd during the short firearm seasons.

This time the pair had borrowed a four-wheel-drive pickup and camper. Other years they had camped in tents on the Gilbert-Baker Special-Use Area just north of Harrison, but the camper allowed them now to stay right in the area from one day to the next.

It was their third day out when that small buck gave them the slip. Marked with numerous promising but unsuccessful stalks, enough acceptable shots to keep spirits high, and an abundant supply of flighty pronghorn, it was proving to be a good hunt.

In years past, Pasture No. 1 had been their traditional ground, not necessarily because it is better than other pasture units, but because it is as far away from civilization as possible. They were like that, just as interested in the quality of their hunt as in the outcome. An extended dry spell during the previous month had changed their plans this season, though. Dry conditions had forced the antelope into the southern pastures nearer Crawford and into the Pine Ridge where irrigated pastures supplied moisture requirements. Even though a liberal shower had swept across the entire corner of the state a few days before, the antelope were just beginning to move back north into their normal range.

Through the years these hunters have developed and refined different approaches and techniques which they prefer for hunting the wary pronghorn. Perhaps the simplest, 34 NEBRASKAland yet most effective technique they know well and like to employ is to locate and stalk a lone, young buck. As small summer groups are absorbed into a larger harem controlled by a mature, vigorous buck, young males that for the first time are large enough to be considered competitors by the herd patriarch are driven out and forced into solitary life. These orphaned, small bucks are susceptible to the hunters' tricks until they adjust to their new way of life. Dick, if given his choice, favors stalking such individual animals. Eager to join any herd that will have him, the young buck often responds to doe-like bleats, and is thus drawn into bow range. A bit indecisive and unaccustomed to making decisions on his own, he often makes mistakes that become the bowman's boon.

This same dislike for competition can sometimes be used to bring a herd buck within bow range. Last year, Turpin and a partner exploited a unique set of circumstances with success. After locating a mature buck and his jealously guarded harem, they would sneak up the hillcrest or ridge nearest the herd. While one archer would raise a pronghorn silhouette in full view of the herd buck, the other bowman would prepare for a shot. In theory, and occasionally in practice, the buck, eager to protect his does from challengers, would investigate the intruder, intent on running him off. In the process the buck would sometimes come close enough to afford the hunters a shot.

Another tactic they have found to be successful is a modified drive. After spending several days in the same area, each herd takes on a personality of its own, watering at the same hole, bedding down in the same general area, and crossing fences at the same point. Once these crossing points are established, hunters can rely on continued use. Placing a bowman at one of these slides while the other spooks the animals in that direction often provides a close shot for the concealed archer.

Dick and Clyde used this strategy about midweek.

Glassing from a towering rim that offered a wide view over several miles toward the Pine Ridge, they spotted a herd of 15 or more pronghorn. Held (Continued on page 55)

Indian artifacts and agate are added attractions during lulls in stalking

Big Mac's narrow west end provides the setting for angling adventure. Paul Temple spreads one stringer while Ace Erb dangles a hefty cat. Later, Paul admires a red-finned, two-pounder

that's what it's all about

BITES, MISSES, NIBBLES, and snags are tough customers to bring into a frying pan. But each occupies a strategic position in the army of obstacles between anglers and the resident channel catfish of giant Lake McConaughy, located northwest of Ogallala. The art of enticing Big Mac's cats from their comfortable, watery homes onto a dinner table was exemplified a year ago in an early May campaign waged by two veteran anglers Paul Temple and Ace Erb.

"For starters, it takes a little luck, some patience, smelly shad, fairly good weather, more patience, and a touch for catfish. Mix all these ingredients together in precisely the right amounts, and you've got a decent chance of landing those sneaky catfish," Paul expounded, as he kept a keen eye on the tip of his rod.

Retired from the judge's bench at Lewellen, Paul is a lifetime area resident and has fished Big Mac for more than 30 years. His angling experiences leave a listener open-mouthed as he relives excursion after excursion.

Paul reached to tighten his line. "I guess cats are my favorites," he continued. "The rascals are hard to catch. It seems as if they come up with a new trick every day. If there's a way to fish for them that I haven't tried, I'd be darned surprised."

"Paul and I spend a lot of hours out here," Ace followed, breaking the peaceful silence that engulfs fishermen on any huge expanse of water. "During the off-season, and especially now that Paul is retired, we really invest a lot of time in these fish. Around the first of April, catfish here generally get right with it, keeping up the action until mid-May when it tapers off. But, how many or few we catch is irrelevant. I've never fished with Paul without having a boatful of fun."

Ace, too, is far from being a stranger to the mysteries of the big lake. Since he is proprietor of Ace's Cedar View, Big Mac has been at his doorstep for the past 12 years. And, prior to becoming a concessionaire beside the lake, Ace called Lewellen home. Like Paul, he has been fishing the lake since its beginning. Ace keeps busy during summer months providing fishermen with bait and tackle, and handling trailer rentals on his area. Even then he always manages to sneak in a bit of fishing.

A misty, cloud-covered morning greeted the pair, along with a stiff, westbound breeze. An early suggestion to scrap the excursion was put aside by the dogged determination of the two outdoorsmen. The fishermen got aboard Ace's 14-foot boat and headed west into the choppy, wind-whipped water. Paul was in the bow. Ace was in the stern, steering. Even though prohibitive swells laced the sprawling lake, they hoped to find some protected waters in the far western reaches. As planned, they motored to a relatively quiet area behind a large grove of partially submerged willows and tied up. Both soon cast baited offerings into the water. They fished in about 2 1/2 feet of water.

At exactly 9:45 a.m., Paul started the action. He caught a snag. After due joshing from Ace, he finally snapped the line, calmly rerigged it, threading on a shad, and sent it back into the water.

"Sometimes I wonder if Paul will eventually pull all the snags out of this lake," Ace continued his gentle ribbing.

At that moment, Ace's line went taut as the tip of his rod swooped down. With the cool of a true pro, Ace played the hit. Wham! He heaved back, hoping to set the hook into whatever was nibbling his bait. Preparing for victory, his jaw fell.

"Miss him?" Paul asked nonchalantly. They both laughed.

"Ace, are you still rolling those bites and misses in flour before you fry them?" Paul asked innocently, his eyes beaming. Ace rebaited and cast back to the same spot.

Dash... dot... dit... Paul's rod tip began dancing with a telegraphic beat. The pole shivered with short choppy action. "Those rascals are just mush-mouthing it," he whispered. "They've (Continued on page 64)

NEBRASKAland Mammoth Lake McConaughy provides an ideal setting for early May catfish foray. Judge and angling ace utilize their years of fishing savvy to entice a super-hefty stringer of reluctant cats

Photographs by Lou Ell, Greg Beaumont, and Charlie Armstrong

Nebraska National Forest near Nenzel is guardian of an ice-locked Niobrara River

Call of WINTER

Snowbound roots elude sun at Toadstool Park

Excitement rides the wind as cold invades the state

PITY THE POOR unfortunates who have felt neither the bite of swirling snow nor the sting of a howling north wind. Weep for those who have never heard the crunch of ice-webbed grass beneath a boot or the echo of expanding ice cracking across a vast and silent lake. Lament their deprivation, for here passes perhaps the most beautiful of all seasons—winter in Nebraska.

Muskrats find shelter in houses, above, while grasses, below, brave the elements

Only earth remembers oldest of winters as at snow-flecked quarry near Lincoln

Frosty panorama portrays winter on Middle Loup River in Halsey Forest

Sheathed in ice, rose hips must rue the season that brings such torment

Simplistic beauty lies in suspened snow, above, and calm of reflected rays, below

Snow runs down to the Platte River's edge as if afraid to venture farther

Skeletal remains of a leafy giant of summer strains rays of a frigid sun

Winter's Midas touch turns leaky water tank near Ogallala into ice

vitality amidst an elegance that those of warmer

climes may never know.

vitality amidst an elegance that those of warmer

climes may never know.Many subtle scenes which strike deeply into the memory are most imposing. Along any country lane, even casual observers find a charm which only winter can bring to the land. Wind-packed snow, lashed into a fencerow, sparkles under a sun which illuminates, but does not warm. And those who abandon the security and warmth of vehicles find a whole new vantage. Clustered in the lee of a skeletal elm, a tiny clump of grass recalls distant spring. To the eye it seems as though growth goes on, but to the touch, the knife-edge of winter rises again as brittle blades shatter under the gentlest of prodding. The search through a wonderland of winter continues, each explorer finding something new to treasure, something which must forever remain intimate and silent.

Pity those who will never know the limitless tract of wintery Nebraska. Weep for those who have never trod the fields of virgin snow. Lament their deprivation, for here passes perhaps the most beautiful of all seasons.THE END

Fencerow near Cairo seems to run to nowhere in ice, snow, and fog

Nebraska's winter is most alive amidst ponderosa pine and buttes of Pine Ridge

STAMPS OF STATE

People, places, and events of past come alive in these commemoratives of NebraskaEven school children can lick history as they delve into cachets which portray many events out of state's development and growth

IF STAMPS interest you, and if you enjoy Nebraska history, it follows that you should be fascinated by postage stamps depicting the state's colorful past. One need not be a philatelist to collect these miniatures of history, a veritable picture gallery of Nebraska's greats. Yet knowing what to look for is an important part of such a hobby.

Six stamps were issued for the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition held in Omaha in 1898. Maize and wheat designs fill the lower corners and upper areas. The scenes shown are Marquette on the Mississippi, farming in the West, Indian hunting buffalo, Fremont on the Rocky Mountains, hardships of immigration, Western cattle in a storm, the Mississippi River Bridge, troops guarding a train, and the Western mining prospector. The last two were taken from paintings by Frederic Remington, noted Western artist. Since Omaha was the site of the exposition, it was only fitting when these stamps were placed on sale there for the first time June 10, 1898.

Although the U.S. Postal Service, the issuing agency, was founded in the late 1700's, commemorative stamps frequently appear long after the events they picture took place. Three such were issued to recall the Louisiana Purchase, and were placed on sale 101 years after the land was obtained from France. When they appeared in 1904, these cachets portrayed Robert Livingston, U.S. minister in charge of negotiations; Thomas Jefferson, then President of the United States; and James Monroe, special ambassador to France in the matter of the purchase, and who, with Livingston, closed the deal. The 10-cent stamp showed a map of the territory.

Several events pictured in these Nebraska commemoratives occurred outside the state. Yet, one was as much a part of Nebraska as the man who originated it. Sixteen years after Arbor Day was begun at Nebraska City, the Postal Service issued its salute to the day. The stamp, which first appeared for sale in that southeastern Nebraska city April 22, 1932, depicts the planting of a tree on what was the shadeless prairie of Nebraska. Perhaps it is most fitting, since the issuance also came on the hundredth birthday of J. Sterling Morton, the man who originated the idea.

Two stamps which bring back the days of thundering hooves and brave young men deal with the epic journey of the Pony Express across Nebraska. One, a three-center, was issued in 1940, 80 years after the fastest mail run of its day began. Found in many collections across the nation, it shows a mounted rider leaving a relay station with his consignment of mail. Twenty years later, another stamp drew from the same basic theme to show a rider racing from St. Louis to Sacramento, a map of his lengthy route laid in behind him.

Though the Pony Express lasted less than a year, its successor was destined to become a vital and lasting part of American transportation and communication. On the 75th anniversary of the driving of the last spike in the trans-continental railroad, stamps were 48 NEBRASKAland offered at Omaha, headquarters for the Union Pacific, and San Francisco. The date was May 10,1944.

Long before the railroad made its debut, hordes of travelers used Nebraska as a highway to the promised land of the West. As these immigrants trudged along myriad trails, the United States Army took up the role of protector, establishing many frontier outposts to offer security against the Indians. One such was Fort Kearny, which served as the "Guardian of the Pioneer" after its establishment in 1848. On September 22, 100 years later, the Postal Service released a commemorative at Minden, a re-creation of the post surmounted by a sculpture of pioneers on their journey taken from the facade of the State Capitol.

Two commemoratives dealing with Nebraska were issued in 1954. One, boasting the Sower standing atop the State Capitol as the central figure, recalled the organization of Nebraska Territory in 1854. The other depicted the 1804 journey of two of the best-known explorers in history. Meriwether Lewis and William Clark were pictured with their Indian guide, Sacajawea, and the keelboat they used on their trek to explore the vast interior of a nation in the making. This stamp illustrated the exactness with which likenesses were reproduced, since the boat was drawn from John Bakeless' book Lewis and Clark.

Nebraska has had its share of men and women who have made outstanding contributions to history. Two such men have been featured on postage stamps. They are General John J. Pershing and Senator George W. Norris. General Pershing was Commander-in-Chief of the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe during the First World War, and was also a Reserve Officer Training Corps instructor at the University of Nebraska. And, Senator Norris has been described as one of the great independent statesmen of American public life. The stamp, which bears his likeness, also carries this tribute from former President Franklin D. Roosevelt: "Gentle knight of progressive ideals." In the background is a view of the Norris Dam north of Knoxville, Tennessee, named in honor of the senator for his part in bringing the Tennessee Valley Authority Act of 1933 into being.

A stamp commemorating the centennial anniversary of the Homestead Act was first placed on sale at Beatrice, Nebraska, May 20, 1962. The act, which played a major role in the settlement of the West, was signed into law by President Lincoln exactly 100 years earlier. Shown on the stamp is a sod house, typical of the early homestead dwellings, with a man and woman standing in an illuminated walkway. The bluish-gray color of the stamp represents a late-evening scene, and emphasizes its bleakness.

Perhaps the most important commemorative among the Nebraska stamps is the one issued in 1967. It honored a century of statehood and recalls the agricultural pride of a people. An unhusked ear of corn and a fat Hereford set the tone for a people tied to the land, and a state which prides itself on farming prowess. But it is people who make the state great. THE END

NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA. . . BURBOT

Eel-like predator, member of cod family haunts Missouri River

THE BURBOT, Lota lota lacustris, is a strange-looking fish that resembles a cross between an eel and a catfish. A sure way to recognize the burbot is to look for its single barbel, or whisker, near the tip of its chin. Other characteristics that identify it are two separate dorsal fins and an anal fin with more than 60 rays.

The color of the burbot is olive to dark brown on the back and sides with a white or yellowish-white belly. The long dorsal and anal fins are the same color as its body. At first glance, the burbot appears to be a scaleless fish like the cat, but close examination shows that it is actually covered with very small scales.

In areas where the burbot is common, it has several names including eel pout, pocket eel, lawyer, and ling cod.

The burbot is a cold-water-loving species that inhabits the depths. It is found in great abundance in waters such as the Great Lakes and the deeper lakes of Minnesota and Canada. This species is distributed over an extensive area of the North American continent. Its range includes all the area north of a line from southern Oregon on the West Coast through central Missouri to northern Virginia on the East Coast.

Within Nebraska, the burbot is found in the Missouri River, most frequently in the tailwater area of Gavins Point Dam. The species is not prevalent enough to justify fishing specifically for burbot. But, when they are caught, they are usually picked up by fishermen using minnows, crayfish, or worms while fishing for some other species. Commercially, they are often caught in traps.

The cod family, of which the burbot is a member, is an important commercial and sport fish in both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Some of the Atlantic species reach a weight of 70 pounds. There are seven species of saltwater cod which are economically important.

The maximum size of the burbot is 14 pounds and a length of 34 inches. However, the average is smaller —6 to 8 inches at 1 year of age, 10 to 15 inches at 2, with a weight of 1 pound or more at this time.

In lakes, burbot live in the deep, cold parts during hot summer months. In winter, they move to the shallows for spawning. According to observations, burbot concentrate in high numbers during the spawning season. Females produce large quantities of eggs, as exemplified by one measuring 27 1/2 inches which contained 1,153,000 eggs. Spawning usually takes place in streams over sand or gravel. The young hatch in May or June.

Very little is known about the life history of the burbot in the Missouri River. Such things as specifically where and when the fish spawn, what the fish eat, and factors affecting their reproduction and abundance are all relatively vague.

In the 1800's, the burbot, commonly caught by sport and commercial fishermen in the Lake Erie area, were considered a trash fish with little or no economic value. However, in the 1900's, the burbot became a valuable commercial fish. In a 10-year period from 1939 to 1949, the commercial catch in Lake Erie within the state of Ohio was 180 tons per year. The burbot is caught commercially in the Missouri River as far north as North Dakota, but the commercial catch in the Missouri River bordering Nebraska is almost negligible.

During the mid-1950's, the burbot was a common catch for people fishing below Gavins Point Dam, but since then the catch has dwindled to only a few per year. It is assumed they spawn in cold-water tributaries running into rivers such as the Missouri. The burbot is known to be a predatory fish, one that feeds on other fish. The burbot in Nebraska feeds mainly on minnows and other small species.

While the burbot is not a common fish in Nebraska, it is the only freshwater cod in existence and adds to the variety of species found in the state. THE END

HEAT, GLASS, AND BREATH

Basic ingredients of ancient trade are unchanged. Modern craftsmen keep art alive

RAINBOWS OF COLOR encircled the glistening glass tube as it slowly rolled in the hissing burner's intense heat. With ease and precision, the long shiny cylinder was turned and turned again by fingers familiar with the task. One end of the tube was sealed. From the other end, a length of slender rubber hose ran to the puckered lips of Lloyd J. Moore.

Moore is the University of Nebraska's glassblower. His lab is a small office in Avery Hall on the Lincoln campus. The doorway is flanked by an assortment of green and red tanks, like those used by welders, and a dusty showcase holding some of Moore's artistic creations, as well as paraphernalia of the glassblowing trade.

The cramped and cluttered lab holds a conglomeration of equipment and materials. An annealing oven, a cutting wheel, and a stout wooden rack holding an assortment of glass tubing and rods take up much of the room's already scarce floorspace. The tables and benches are littered with tools and miscellaneous scraps of glass. But the disarray is not reflected in the quality and quantity of the work which daily flows from this lab.

Orders are received every day from many different branches of the university. The laboratories of the chemistry and physics departments, as well as different divisions within the School of Agriculture, all need his specialized services. Because of the heavy work load, the university recently added another glassblower to the staff, Tim Grauer. Grauer now shares the diminutive quarters with Moore. Both are members of the American Scientific Glassblowers Society, and both put out work every day that meets with the highest standards of their profession.

Moore has now been at the university for more than 10 years. Though very well established in his trade, he followed a rather circuitous route to reach his present position.

Born in the midwest, Moore has strong ties with the land and the earthy elements of rural life. His parents were ranchers, and young Lloyd became a good horseman, breaking and training horses.

52 NEBRASKAland"Rural life was the only life I really knew, recollects Moore. "When school was out for the summer I would work in the hay fields."

Hard work has always been part of his life. After the death of his father, Moore was able to continue his schooling, but the burden of supporting his mother, two sisters, and six brothers became part of his responsibilities. Throughout his high-school years, Moore worked part-time before and after classes at a variety of chores, including milking cows, planting crops, and similar farm tasks.

Refusing an offer to become a partner with the farmer for whom he worked during the summers, Moore attended the College of Emporia on a track scholarship. He originally intended to study for the ministry, but events during the summer after his freshman year forced changes in his plans Deciding that being a minister would not be to his liking, he again worked in the fields when a fall from a truck injured his back. The athletic scholarship was lost, and Moore had to look elsewhere for his education.

Lawrence, Kansas became his new home, and after working for a time at a lumber company, the ambitious youth enrolled at the University of Kansas. There he took a job working in the Chemistry Department, and eventually began glassblowing.

Glassblowing is not an easily acquired art. Only so much knowledge can be gleaned from books or even from a good teacher. The rest must be learned from experience. Moore was intent on becoming a good glassblower.

"It took 3 1/2 years of constant trial and error and continuous practice just to learn the basic fundamentals before I felt I was able to seek a job as a scientific glassblower," he recalls.

Moore remembers his initial failure when he sought a position at the University of Nebraska. "After the first interview, I (Continued on page 63)

JANUARY 1972 53

THE SKY IS HIS HOME

(Continued from page 17)these believers, despite the fact that he has experienced 12 engine failures during the past year, although none of them occurred during an air show, and he got the engine started again every time without having to make a forced landing.

"You really start grabbing for things in a hurry when it dies," he admits. In his cockpit, there are only a few essential instruments, a far cry from commercial planes equipped for instrument flying. In fact, the panel looks more like an automobile's dashboard. Fancy equipment is unnecessary and its absence keeps weight down. He flies visually, and his maneuvers happen too fast for a dial to keep up with them.

Without doubt, the most spectacular and difficult gyration Dr. Carothers performs is the Lomcevac, which is appropriately named because it is Czech for "headache." While it takes only a few moments, this single maneuver puts more stress on plane and pilot than any other. It is a combination of motions in which the plane climbs steeply, then tumbles in spiral, end-over-end flips.

Some maneuvers are solo exercises; others a series of different flights. A combination of light weight, small size, and high horsepower enables his plane to move quickly, sometimes faster than the eye can follow. To help spectators appreciate just what it does, an oil-injected exhaust system leaves a trail of smoke. In calm weather, Dr. Carothers often fills the sky with a maze of crisscrossing, white corkscrew stripes.

There are literally thousands of distinct moves he has had to learn, many of them included in aerobatic competition. Dr. Carothers enters national matches each year, as well as regional contests. Winning a meet brings honor, but hardly compensates for the amount of expense, practice time, and work involved. Despite all this, he attends as many as possible. The biggest obstacle is getting there if it's far away. He flies every day, except when the weather is bad or the plane is dismantled. If repairs are necessary, the plane is put together again within a day or two because skipping even a few days of flight can cause a loss of timing — perhaps the most important aspect of precision flying.

"I can tell when I have had an interruption in practice," Dr. Carothers says. "That is why I try to fly every evening after office hours. My routines go in sequences, and a few seconds here or there make a lot of difference. Miscalculation means the plane covers more ground than it should, and the smoothness is gone."

"My flights require a lot of split-second timing in just the right order. The plane, of course, must be in top condition, and that takes a lot of time, too. My mechanic, Ed Mooring of Wahoo, keeps it in good shape. Experimental planes like mine fall into a special category, and the stresses created by this kind of flying cause problems. The propeller flange, for instance, must be checked frequently. Flying upside down as much as right side up requires a special fuel system. And, the small size of the airplane means there is no room for conventional equipment. In theory, my little plane should not even be able to get off the ground, yet it does — very easily.

"For its weight and size, this is perhaps the most powerful propeller plane made. The Lycoming engine cranks out 180 horsepower at 2,700 rpm's, and I usually keep it turning a little faster than that. Empty, the plane weighs about 750 pounds, so with me and the fuel, it still weighs only about 1,000 pounds. Once aloft, there is little it cannot do."

Watching him perform at an air show confirms that statement. There are few contortions the plane is not put through. Twists, loops, rolls, spins, dives, climbs, glides —all are there. Sky-gazing spectators hold their breath in wonder and delight during his aerial antics. And, the more familiar a viewer is with flying, the more he appreciates the difficulty of such feats.

"At air shows, I usually perform the first half of the routine I use in aerobatic competition. It is new and fresh for the audiences, but I have it down pat and it's comparatively easy for me."

Dr. Carothers performs at an increasing number of shows each year. His 1971 schedule included 12 shows in Nebraska, 10 in Kansas, and several in Iowa and Missouri. A busy dentist during the week who is willing to perform almost every summer weekend, he is a rare one indeed.

Watching a performance of the little red-and-white plane leaves little doubt about the value of dedicated practice. The 15-minute demonstration is startling. A spectator is not concerned with the tremendous forces the pilot is fighting, or the stresses on his plane. He is only amazed at the spectacular end result—loops, upside-down or knife-edge flight, and a multitude of tumbles and flips. He wonders why the pilot doesn't fall out, although there isn't much time to think about such things.