WHERE THE WEST BEGINS

NEBRASKAland

December 1971 50 cents

For the Record... GENTLEMEN OF CAP

The irate hired man fumbled with the broken strands of wire as he sought to fix blame for his extra duties. He had found the gap in his employer's fence when he was rounding up cattle which had found the opening. All he could do was repair the damage, but under his breath he offered a blanket indictment: "Must have been those damn hunters!" It mattered little that all game-hunting seasons were closed. Hunters were easy targets for the hired man's wrath.

Though such accusations frequently are exceptions rather than rules, this hypothetical illustration does point out isolated instances where hunters are unjustly blamed. The question remains, however: How do hunters conduct themselves on private land when they are allowed to hunt without being required to ask permission? In an effort to answer the query a card survey was launched this year by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. George Nason, district game supervisor at North Platte, contacted landowners co-operating under the Cropland Adjustment Program (CAP), which provides public-access hunting areas across the state. Some of the replies at least partially answer this question.

Of the total 485 cards returned by farmers, slightly more than half admitted they had been concerned about hunter behavior before enrolling in the program. Of these, 80 percent reported they experienced less trouble than expected, with only 10 percent announcing more.

Another measure of hunter behavior is whether landowners signed up for the program would do so again. Of those who experienced less trouble than expected, 96 percent indicated they would. Only three percent of the group said they would not re-enroll and the rest were undecided. The negative side showTed a turn for the better, with 48 percent of those who received more trouble ready to enroll again. Another 36 percent indicated they would not sign up again, and the rest were undecided. It must be pointed up, too, that those who would withdraw their land had other uses in mind for it.

Despite the high population of the eastern third of Nebraska, that area showed no more concern about hunter behavior than those out west. In the east, the poll showed, 80 percent of concerned owners had less trouble than expected and 10 percent had more. The concerned western group reported 75 percent of their ranks had less trouble and only 15 percent had more.

All these percentages are nice, but what do they mean? First, they show landowner-hunter relationships in Nebraska are quite good. Second, they indicate the CAP program could well be a continuing success. And lastly, they show that there is room for improvement. The poll does not totally absolve hunters of problems resulting from using land open to hunting. But, it clearly shows that the majority of hunters behave like gentlemen when afield.

LUCKY IS THE HUNTER

IT WAS CLEAR, cold, and dark that morning in November of 1964. A sophomore at Chadron State College from North Platte, I hauled out of bed and dressed as quickly as I could, trying not to disturb my sleeping roommates. In only a few minutes, I would be on Nebraska National Forest lands in the Pine Ridge Division for a crack at a big buck during the archery deer season. As silently as possible, I scooped up my 49-pound-pull bow and 30-inch hunting arrows and slipped out to meet my partner Art Halfhide.

Art picked me up right on schedule, and after breakfast, we were off to the Deadhorse Road area southwest of Chadron. We had many places to hunt in the National Forest, but our chosen spot seemed the most likely to pay off. Headed south from town, we estimated we had about two hours before Art would have to start back to the drugstore where he was and is a pharmacist. My first class wasn't until after 11 that morning.

Frequently, we had seen deer in one particular pasture along the road and figured we stood a good chance of a shot that morning. Possibly 8 a good four-point buck that we had seen would still be there. It was just legal shooting time when we pulled into the area and the deer we had seen before were there. We weren't sure whether the buck was among them, though, since they blended into the background.

Plotting quickly, we decided one of us would get out while the other would drive to the other end of the pasture. We hoped to get the deer between us as they worked into the timber for the day. Art stepped out of the car and I drove to the other end of the pasture, got out, and attached my bow quiver.

Working my way slowly back into the timber, I tried to keep an eye on the deer as I moved over the frost-covered ground. I was about 200 yards from the car when I was confronted by a small bank —maybe three feet high. Reaching up to grab a small, frost-covered tree for leverage, I curled the fingers of my right hand around it and placed one end of my bow on the ground with my left. With my foot jammed into the dirt about halfway up the bank, I was suspended when my grip on the tree began to slip. There was nothing I could do and, almost before I NEBRASKAland knew it, I was lying on the ground at the foot of the bank. I figured I might as well try again, but as I got up, I noticed my right hand and arm were tingly and sticky. More puzzled than hurt, I slipped off my glove, and that's when the whole affair hit me. I had fallen on the unprotected broadheads protruding from my bow quiver.

There were two holes in my arm where the arrows had gone in. The pain was lessened only by the fact that my arm had instantly gone numb. I needed help! As I clamped my left hand over the wounds, trying to form a compress with my fingers, I began yelling for Art. It seemed like an eternity before he arrived, though it couldn't have been more than a few minutes. Maybe he wasn't in as big a hurry as he could have been, because, as he said later, he thought I had downed the buck we were after. He didn't know I was hurt. When he found me, though, he went into action. Using both his handkerchief and mine along with my sweatshirt, Art fashioned a compress to try to stop the bleeding. Securing the improvised bandage with his belt, he helped me back to the car and we headed for town.

Though I was a little light-headed, I still remember one ironic aspect of the trip. Art suddenly slowed down and told me to look out into the pasture we were passing.

There —within easy bow range — stood a big buck and four or five does. All we could do was look. That trip to town and the hospital seems like one of the fastest I've ever made. When we arrived, Art called the doctor, who was on his way immediately. After he cleaned and dressed my wounds, I found out how lucky I had been. Had the arrows gone in a bit higher and at a slightly different angle, they would have severed the major artery in my arm. As it was, they only cut a vein. So, I was ordered home and to bed.

Unfortunate accidents have a tendency to leave us much wiser. This one did just that for me. I look back now and think of things that would have prevented the whole affair. First, I should have worn boots that would have gripped instead of sliding on the frost. Second, I should have used a protective cover over my broadheads. And, third, (not so much preventative as just plain common sense and the only rule I followed) I wasn't hunting alone.

Later in the season, we both managed to fill our permits, testifying to my complete recovery. But, I still carry the scars of potential tragedy that day. THE END

This hobby is fun in the doing and the proving. Start your "bug" collection

HOW TO: Tie Flies

FLY SEASON means different things to different people. To some, it is time to pick up a swatter and head for the rocking chair on the porch. But for an angler, it is a magical moment devoted to seeking out that certain trout stream, or possibly settling down at the workbench with a fly tying outfit.

Creating a beautiful, never-fail enticement in feather and floss, then using it to land a hook-nosed trout is an accomplishment too few anglers enjoy. Yet, all it takes is to give fly tying a try. Many enjoyable hours may be spent hunched over a hook vise, thread spool in hand. And, as a bonus, homemade specimens are generally much more durable than their commercial cousins.

Assuming that many anglers don't have a friend who can demonstrate such techniques, NEBRASKAland prevailed upon an authority to show the proper method. J. G. (Jake) Geier teaches the subject at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, and also 10 uses his products on the trout stream, so he knows they work.

There are three basic fly types — streamers, nymphs, and flies, (wet or dry). While design, color, material, and size vary, procedures for making each are basically the same. Body, wings, hackles (those whiskery things protruding from around the fly's collar), tails, or legs are attached by winding thread around them.

To start fly tying, it is advisable to buy a kit containing the basics. These include a vise, small scissors, hackle pliers, bobbin, whip finisher, and sundry thread and feathers.

With the necessary ingredients spread before you, clamp a hook in the vise jaws. For practice, start with a No. 10 hook and put on a single foundation wrap of thread using the bobbin, which keeps the thread on the spool until you pull it off. End this, and all other steps, with a half hitch in the thread.

Leave the filament hanging, and tie on half a dozen spines of small feather. This "tippet" can be fashioned from many different plumes, but Jake prefers breast feathers of the golden pheasant. Wrap the lower end of these spines securely, leaving the upper ends projecting.

Next, cut off several inches of black yarn, tinsel, and red floss or silk thread. The yarn is secured with thread, then wound around the hook, working it down the shank, then back over itself toward the eye. Repeat this back-and-forth wrap again to produce a heavy body. When satisfied with the size, wrap the upper end of yarn with thread and cut off any excess. The same procedure is used for tinsel and red thread, using only enough of these to create a barberpole effect on the black body. Tie the upper ends securely, and trim off excess.

Rooster neck feathers make good wings. Select four, two-inches long, and strip away two-thirds of the webbing, leaving only the shiny part near the tip. Put several loose wraps of thread around the quill, then adjust them so the curve of the feathers enclose the hook. When in place, wrap them tightly and trim away extra stem.

Hackles are the last addition, and can be made from rooster feathers similar to those used for the wings. Slide a thumb and finger along the feather to spread the spines, theirtlcr onto the hook with thread.

Hackle pliers now come into play. Clip them onto the tip of the feather and wrap sideways around the shoulder of the fly so that half the spines fan out, sticking up away from the body. They look just like long whiskers if done properly. When only the tip remains, tie with thread and trim.

The finishing touch is to wrap the head of the streamer. Wind on 15 or 20 turns of thread between the hook eye and the hackles, but not enough to form a lump. When it looks right, get out the whip finisher. This tool helps tie the final knot, one which won't unravel. Holding it in place string thread between the points.' Spin the tool, between thumb and forefinger, around the hook four or five times, tilt, pull out, tighten the thread, and cut off. Daubing on a little clear fingernail polish or cement will seal the wrap, and the creation is ready for the water.

The art of fly tying is so intriguing that many people cannot decide which is more fun — manufacture or use. If you have only done the latter until now, head for your workbench and really tie one on. Then make a comparison. With practice, you can become an expert. THE END

NEBRASKAland

Speak Up

WAY OUT BACK-I am a SeaBee from Nebraska and have just received my first two issues of NEBRASKAland. I noticed an ad in both issues that said 'Delivered to your home or even your deserted island'. You don't know how true that is. I am with NMCB40 on Deago Garcia located in the Indian Ocean. And, it is deserted except for 700 SeaBees." — Richard L. Neuse, FPO, New York, New York.

BLUE RIVER FLOATS-"One of the prettiest events I have ever seen, and one I will always remember, took place several years ago on the Big Blue River near Beatrice. It was called Venetian Nights and consisted of floats made on boats and barges. All were hooked together and pulled down the river. The event I saw was in 1927 and the entries were made to depict special events such as Christmas. The people on board sang carols as they floated by and people came great distances to watch the display." — Mrs. Brock Smith, Memphis.

This is the first the editors of NEBRASKAland have heard of such an event. We would appreciate any further information or photos readers might have. — Editor.

HOT SHOT-"While attending the National Rifle Matches at Camp Perry, Ohio, as a member of the Nebraska Civilian Team many years ago, I was firing in the Wimbledon Cup match, 20 12 shots at 1,000 yards. I was lying on the firing line right beside Dr. Lincoln Riley from Wisner, who was the team captain. The doctor was hitting the bull's-eye right along, one shot after another, a rare feat. By the time he had scored 15 straight bull's-eyes, shooters all along the firing line were watching alertly. Shot No. 16 was also a bull's-eye. Then came No. 17 and the marker was a red disk signifying a score of 4. Phoning to the targets, the range officer asked if that were correct, and learned that it was a 'wart four' just outside of the bull. Dr. Riley finished his string with three more bull's-eyes for a score of 99 — 1 less than a 'possible' and was close to the top man in this famous match." —Julius Fester, Prescott, Arizona.

HEAP SMART - "No doubt you have heard of the white man and his Indian friend going deer hunting. The white man was armed with bow and arrows, while the Indian carried a rifle. After the white man's deer got away with two or three arrows stuck in him, the bowman turned to the Indian: 'You people are experts with bow and arrow. I'll trade mine for your rifle.'

" 'Uh, no. Bullet better,' came the reply.

"From the humane angle, I agree with the Indian, and hats off to him." — A. J. Stenner, Powell, Wyoming.

EXECUTIVE TIPS-"Steve Olson's article, Hooked on Browns, in the September issue of NEBRASKAland, brought back some great memories. Earlier this summer, my family and I camped on the Snake River in Les Kime's back yard, our trailer parked somewhat precariously on the canyon's rim. The absolute beauty of the place is something we will never forget!

"For your readers who prefer to fish with flies, I am happy to report that Snake River trout find them attractive. A 22-inch rainbow gobbled up one of my black gnats (wet, size 12) while a black woolly worm fetched an assortment of nice browns and rainbows. I found a small split shot a couple of inches above the fly necessary to get down where the fish are. This makes fly casting a little clumsy, but it is well worth the trouble." -Jack Scott, Administrative Assistant to Senator Roman L. Hruska, Washington D.C.

UP WITH REASON-"I read with interest and appreciation the letters from George H. Burnett of Omaha and Donald L. Hayes, Hopkinsville, Kentucky, on the Speak Up page of the September issue. It is gratifying to note that a few people still have the level-headed outlook on the events and ideas that so many anti-firearm and anti-hunting fanatics are coming up with these days. These letters and the editorial by Mr. Willard R. Barbee in the same issue should be read by those so-called anti-crime and wildlife protectionists.

"I am a former Nebraskan who is nearing 81 years of age. I am in excellent health and still go hunting every chance I get. I think I owe a lot of my good health to the many days I spend in the great out-of-doors." —Ramon Harding, Portland, Oregon.

WE'RE THE BEST-"I was really glad and proud to see your article, Legend in Red, in the September issue of NEBRASKAland. Yea, that's all right! But, I would like to see more pictures and write-ups on our No. 1 team. (Many more.)

"Let's really inform the folks in other parts of the country about our No. 1 team and the great people of the state behind it. Don't let them forget that we're No. 1 and proud of it."-Lynette Marshall, Verdigre.

WOOPS-"The article, Profiles of the Past, by Warren H. Spencer in the August issue of NEBRASKAland is very interesting. It does, however, contain an erroneous statement which I wish to call to your attention.

"Ami Ketchum is buried at Kearney. The grave of Luther Mitchell is in the cemetery at Central City-marked by a simple stone marker." —Mrs. Rexford Ferris, Central City.

With such stationary subjects, it is hard to get them mixed up, but we did so at any rate. Our apologies to our readers for the misinformation. — Editor.

BARBED MEMORIES-"A few years ago, as my father and I began to set a new fence, I recalled doing the same thing with him in Nebraska when I was very young. I usually ended up tearing my shirt or hooking a bit of skin on the barbed wire. So, this thought came to me and I thought I would share it." —Mary Graham Saunders, Lebanon, Oregon.

RANCHER'S WISH by Mary Graham Saunders, Lebanon, Oregon I wish that I should never mend Fence with wire too stiff to bend. Wire with hook and sharpened barb To catch and tear my rancher's garb. Digging and setting twisted post Lining each up...half straight at most Tightening the crooked, prickly cable Hoping to make it firm and stable. Withstanding pressure of wild-eyed cow Until it breaks, who knows how? I wish that I would never mend That fence, with stiffened wire to bend. Wire with hook and sharpened barb To catch and tear my rancher's garb! NEBRASKAland

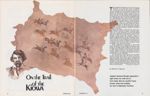

On The TraiI of the Kiowa

14 NEBRASKAland DECEMBER 1971TRAVELERS ON THE Santa Fe Trail in Kansas Territory in the fall and winter of 1859-60 were far from safe. Every journey entailed an element of danger few were willing to accept. In the autumn of 1859, large numbers of Comanche and Kiowa had moved into Texas, hoping to come to terms with the U.S. government, thus ending years of warfare between the two worlds. All seemed ready for a lasting peace and a treaty the Red Man could live with. But both would have to wait — immediate prospects felled to the report of exploding gunpowder. Kiowa Chief Big Pawnee was shot to death September 22, 1859, by a Lieutenant George D. Bayard in what could be termed as less than a diplomatic disagreement. In those tense times, the incident was enough to touch off wholesale slaughter along the trail. By November, perhaps 13 travelers had been murdered.

Despite the killing of Big Pawnee, the government couldn't sanction "savages" running roughshod over a white population. So, that next spring what was to be known as the Kiowa-Comanche Expedition of 1860 was formed. The force was a two-pronged assault group, the southern pincher of which jumped off from Fort Cobb, Chickasaw Nation. While a northern arm swept down out of the northwest under the command of Major John Sedgwick, it was the southern column, headed by Captain Samuel D. Sturgis, that was to go down in history as the campaign's most important element.

Fully expecting to encounter at least 3,000 Kiowa along their route, Sturgis and some six companies of mounted troops headed out of Fort Cobb in what is now Oklahoma, and turned north on June 9, 1860. Ahead of them lay the largely uncharted reaches of Indian Territory, a hostile Kansas, and a running fight in the sprawling expanse of what is now Furnas County, Nebraska.

For the most part, their march was uneventful as they covered more than 700 miles in 44 days. Their only break from tedium came in discovering deserted Indian camps and ogling thousands of buffalo which literally carpeted the plains. The only members of the expedition who encountered any hostiles were Delaware and Tonkowa Army trailers, about a hundred strong; though for some time, even they saw their quarry (Continued on page 53)

by Warren H. Spencer Captain Samuel Sturgis expected a fight when he rode out of Fort Cobb. But he couldn't have known what was waiting for him in Nebraska Territory

Running the Shallows

With an airboat, deep water is unnecessary. In fact, sandbars are as much fun and even more adventurous

A STEADY DRONE of propellers filled the morning air as three pilots maneuvered their craft along the winding river course. Heavy foliage lined the banks, concealing whatever resided there. Only tracks, crisscrossing occasional sandbars, told of life's existence.

On this mission, no guns protruded from the cowlings, however. And the formation was not made up of World War II fighter planes ranging after enemy installations. Instead, the pilot trio helmed three airboats as they skimmed the tricky channels of eastern Nebraska's Platte River.

Airboats, those amazing shallow-draft hulls pushed by airplane propellers, have found a real proving ground on the Platte. Indeed, they are about the only powerboats practical on the seldom-deep, always-twisting waterway.

After running airboats several years for pleasure, and building a few for his own use, Duane Shunk of rural Valley decided on a deeper involvement. Experimentation led to his discovery of a special mold for fiberglass hulls, which must be sturdy enough to bump over sandbars, logs, and other obstacles.

Duane's airboats zip along at about 40 miles per hour, which seems much faster as trees on the riverbanks blur by. Even so, speed is secondary to the main benefit — their unique ability to flit about in exceedingly shallow water. With neither rudder nor drive unit protruding below the hull's surface, airboats skim along in only an inch or two of water, gliding even better across reeds or grass. Sandy stretches pose problems only if they are extremely high or wide.

Late last summer, Duane and two friends spent a day island hopping on the river — a fairly common practice for them. Three of Shunk's products, one with him at the controls, another piloted by Gary Dahlgren of Valley, and one he sold to Larry Peck, also of Valley, formed the trio. And, an impressive fleet it was, breezing along the river between home and Fremont. A distance of about 15 river miles, a round trip should have taken less than an hour. But, there were many pauses in the river run.

There was an island to visit where, in loose sand at one end, turtles laid eggs. Nearby, shade trees formed a favorite picnic spot, and Larry often spent several summer days loafing there.

A short distance upriver, heavy equipment moved dirt and sand along an embankment between the With an airboat, deep water is unnecessary. In fact, sandbars are as much fun and even more adventurous DECEMBER 1971 17 Instant acceleration brings

noise and motion that can

be duplicated only in an open

plane or on a motorcycle

water and a new house, offering

unending possibilities for exploring.

Instant acceleration brings

noise and motion that can

be duplicated only in an open

plane or on a motorcycle

water and a new house, offering

unending possibilities for exploring.

And, in mid-summer the water level was down considerably; at least four feet lower than earlier in the year. Such depletion offered ample opportunity for sandbar hopping.

One more mile, and a fisherman caused another stop. George Arps of Fremont, all alone in his airboat, was just starting to check his setlines and was unhooking his first catch of the day — a nice three- pound catfish.

"Stop by on your way back, and I may have a nice stringer to show you," he shouted over the idling prop's growl. "I'll be out most of the day; either here or over by that island across the way. If you guys do any fishing, get into the deep holes where the water moves fast. That's where the big ones are. I caught a 19 1/2-pounder here a few weeks ago." With a wave, and a promise to drop by later, the airboaters moved on.

It's tricky leaving, because prop wash throws a lot of air and water. Anyone standing astern gets a good shower if a boat is not maneuvered right. And, starting out in shallow water sometimes requires a lot of throttle before the craft begins to move. Gary was the victim on that start, getting a good drenching as Larry gunned back into the main channel.

Dwayne's boats are 8 feet wide, 16 feet long, and almost flat on the bottom. Peculiar steering characteristics mean that edges must be more critically contoured than most other boats. In a sharp turn, a fan boat slips sideways. So, at a good clip, the rig could capsize should it ram a sandbar. Sideslip is fun, though, and there is plenty of it because of the river's winding course. Knowing when to start a turn and when to apply power takes practice — more so than in a regular boat.

Power is never lacking. Two of the boats have Pontiac engines, and the third boasts a big Chevy, giving each around 400 cubic inches of throbbing power. Auto engines are used because they are more dependable and much easier and cheaper to service than the aircraft types used in many such boats. At a flick of the throttle, they accelerate 18 immediately and noisily. That noise, and motion combined with the rush of air, provides an exhilaration that compares with an open plane or motorcycle.

Because the bow of the boat is normally used for entry and exit, Duane puts no windshields on his models. The resulting rush of air adds to the feeling of freedom. While obstacles in the river are avoided whenever possible, there is little concern if they are hit. The heavy hulls can even skip over steel girders with barely a scratch. Gary Dahlgren knows.

Just beyond a railroad bridge south of Fremont, his boat scrunched into a piece of submerged steel. "I saw the thing coming when your wake pushed water away, but by then it was too late. I thought it would come right through the bottom, but we just bounced over. Bet there's a long scratch down there, though," he grinned. Duane's two sons, 17-year-old Don and Brad, 12, were with Larry in the trail vessel, and they skittered through the same stretch of water without touching the obstruction.

Carol, Duane's wife, was to be picked up on the return from Fremont. She had foregone the upriver stretch, opting to fry a batch of chicken and prepare other goodies for a noon picnic. Prior planning called for a swing downriver to Two Rivers State Recreation Area for lunch later in the day. Then, they would continue on to the confluence of the Platte and Elkhorn rivers where Don and Brad planned some late-season water skiing.

"I think I can smell that fried chicken from here," Gary quipped almost as soon as the bows of the three boats settled onto a sandbar just below the Fremont Airboat Club. "I also got kind of thirsty a while ago -I think it was when Larry sprayed us with water back there. Throw me some of that pop you're hoarding in your cooler, Larry, or I won't help shove you off when we head back," he threatened.

"Something is growling inside me, too," Gary returned. "I think I may look for some shortcuts."

Duane just shook his head and grinned, (Continued on page 55)

NEBRASKAland

HEP FOR BEAVER

Clarence Sanders traps for just one reason. He loves it

FOLLOW HAP SANDERS for one day when he's running his traps, and you'll wish you had his energy. You'll tramp through weeds, ford creeks, slip down muddy banks, and stumble over beaver-gnawed stakes.

At 59, Clarence (Hap) Sanders farms 400 acres and is caretaker of the Memphis Lake State Recreation Area near Ashland. But, winters are as busy as summers for Hap— an ardent beaver trapper.

"I've done it ever since I was a kid," Hap explained, as we left the cafe in Union where we met. Despite a cool breeze, it promised to be an unusually warm February day. In the back of his pickup was an impressive load of fur— 6 beaver and about 50 muskrat, all taken the previous day.

"I trap for one simple reason. I love it. Beaver hunters are like coyote hunters, you know. Everybody says you have to be nuts to be a coyote hunter; absolutely no gain in it. You ask a man why he's a coyote hunter and he'll say he loves (Continued on page 55)

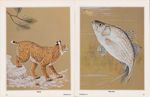

Craftsman of Fauna

A master in his own right, Bud Pritchard picks his best from over two decades of excellence

DURING the past 21 years, NEBRASKAland Magazine, has from time to time, changed its appearance to stay abreast of advancing trends. Artists, photographers, and writers have come and gone, bringing, then taking their individual styles with them. In 1964 the magazine's title changed from Outdoor Nebraska to NEBRASKAland, coinciding with the addition of color to 10 center pages. And, in 1966, color reproduction spread throughout the magazine. From 28 pages in 1950, the publication expanded to its present 68. But one monthly feature —Notes On Nebraska Fauna— remained constant. So did its artist, C. G. (Bud) Pritchard. Bud joined the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission in 1948 at the age of 38. Still an unestablished artist, he had yet to develop the realistic style for which he is now noted, but it soon became evident that his talent should not be wasted. Late in 1949 he was assigned a black-and-white watercolor illustration of a mule deer to be published as part of Outdoor Nebraska's first formal fauna feature in January of 1950. That artwork launched what had been designed as an experimental series into the longest, uninterrupted run of monthly features still being published in NEBRASKAland. The only basic change came with the expansion of color in 1966 when Bud switched to color from black-and-white illustrations. Popular since its inception, the series is, without doubt, the most notable, artistic documentation in existence of Nebraska wildlife. Although Bud has used all materials during his painting career, he prefers tempera for both practical and artistic reasons. Compared with oil, tempera dries rapidly, allowing him to work within the monthly schedule of publication deadlines. It also offers a wide range of hues, providing every muted or lustrous shade he needs.

With the exception of a two-year correspondence course in art instruction during the early 30's, which offered a bit of formal training, Bud is a self-taught artist; craftsman of a mature, realistic, and well-developed style mastered through hours upon hours of wildlife observation and many more at his easel. He is a courteous, soft-spoken gentleman. Quietly, without influence except that which emanates from his own love for wildlife, he produces paintings noted for their accuracy and detail. He spends much time outdoors, sometimes hunting in season, but mostly observing the animals that eventually appear in his illustrations. His wife, Mary Lou, often accompanies him, especially during bird-watching walks. Both are members of the Audubon Naturalists Society.

Bud won national honor three years ago when the U.S. Department of the Interior chose his illustration of the hooded merganser (see Notes on Nebraska Fauna, NEBRASKAland, October 1964) to be used on Federal Migratory Waterfowl Stamps for the 1968-69 season.

Reproduced here are 10 fauna paintings he himself chose from his 62 color illustrations published continuously in NEBRASKAland since February of 1966. Some of them are among his favorite animals (small mammals, songbirds, and waterfowl) and represent a selection based on reproduction potential, composition, and harmony. They demonstrate his unique achievement as an outstanding, nationally recognized wildlife artist. THE END

22 NEBRASKAland

SEA HORSE OF PRAIRIE CREEK

Horns and pearly tusks were all Lynk Phelps saw, but he wasn't waiting for a better look

LYNK PHELPS MUST have cut a crazy figure that day in 1870 when he exploded from the swimming hole on Prairie Creek. Grabbing his clothes, he headed — stark naked — for the wagon and team tethered nearby. Hurling his duds into the wagon bed, Lynk hustled around the side and beelined for the traces which held the horses. But his nude body startled them and they reared, cinching the halter knots so tight that Lynk couldn't get them loose. Instinctively, he reached for his knife only to realize that his pocket was in the wagon, so he clawed at the reins until they came free. Then, heaving himself onto the seat, he ran the team all the way home and into the barn. Bursting into the house, he bolted the door, ordered everyone away from the windows, and was still babbling when Uncle Lyman Balcom walked in.

Lynk sputtered his story about a monster in the swimming hole, slowing down only when he remembered he had left one of his boots behind. He offered $10 to anyone who would go after it, but when Uncle Lyman volunteered, Lynk wouldn't let him out of the house. It was early the next morning when Uncle Lyman finally sneaked out, made his way down to the creek, and returned some time later carrying a well-scarred boot.

Lynk, Uncle Lyman's hired man, was on the job when the whole episode occurred. He had been sent to Grandpa Rose's cheese factory near the Balcom farm to deliver a load of milk. It was customary that after the milk was delivered, several of the men got together for a quick dunking in the creek. On that particular July 3, Uncle Lyman told Lynk not to go in until he 32 arrived, but when the sun began to sag in the west, they all decided to go swimming anyway. That's when it happened. One of the men noticed something floating downstream toward them. Its horns and pearly tusks stood out against the dark water. Not sticking around to investigate, Lynk lit out.

The next day, Lynk drew more of a crowd than any exhibit at the Clarks Fourth of July celebration. There had been several rumors of a water monster stalking the Prairie Creek-Platte River area near Silver Creek, and Lynk said he had seen it. He told and retold the story until what he described as a "sea horse" was 40 feet long, and his tale made the whole thing seem so real that a group of local hunters decided to go after it. They asked Uncle Lyman to help and he agreed.

The day of the hunt came and the men arrived at the Balcom farm aboard a spring wagon. Uncle Lyman took them up the creek to where the hunt was to begin, passing one place where the rushes were tramped down. That was evidently where the sea horse had slept. Suddenly, not far ahead, the monster poked its head over the riverbank, scanned the approaching hunters, and disappeared. Guns at the ready, the party converged on the spot, expecting to find the creature. He was nowhere in sight. Still, things were so tense that if anyone had thrown a hat in front of them, the hunters would have blown it to shreds. But the uncertainty of the moment was enough to deter even the best-armed of the group and all decided they should return to town for reinforcements.

Days passed before another hunting date was set, and stories of the first foray grew all out of proportion, NEBRASKAland and one man, a professor in Clarks, showed a lot of interest in being the one to kill the monster, and that, too, got around. By the time the hunt was rescheduled, it was pretty much agreed that he would have the opportunity to do the beast in.

The night of the big hunt was at hand. Men from throughout the neighborhood and from Clarks arrived that evening. They came in wagons, spring wagons, and on horseback; some even brought lanterns in hopes that the light might attract their quarry as it swam along.

It was late dusk when the sea horse came floating down the river. All agreed that the professor should have the first shot, so when the monster came within range, he began shooting. All of his shots missed their mark, though, and as the target moved closer, he dropped to one knee for a better aim — still he missed. Finally, Uncle Lyman said he would have a go at it. He took careful aim and, sure enough, his shot sent the monster to the bottom of the river.

Everyone was ready to retrieve the kill. Everyone, that is, but the professor who feared that the beast might only be wounded. He wanted no part in bringing it out of the river. So, several of the older men waded out to where the monster had gone down. They found the sea horse and managed to get a rope around its horns. As it was hauled ashore, one of the men grabbed the carcass, heaved it onto a horse, and headed for town with the rest of the company close behind. When they arrived, they found bonfires already blazing and the townspeople all set for a feast of roast sea horse. Their expectations were short-lived, however, when DECEMBER 1971 they began to examine the animal and found that it wouldn't make good eating at all.

It seems that the whole thing was a great ruse concocted by Uncle Lyman after many people had seen a log of about the same shape floating down the Platte River. The monster's neck and head were made from burlap sacks stretched over barrel hoops. The horns were long cow horns and the tusks were willows stripped clean of bark. The beast was constructed so that a man could carry it on one arm while swimming, thus giving it a rocking motion as it moved through the water. Shooting posed another problem, though, since no one could safely swim with the beast. So, bottles were installed to keep it afloat and when Uncle Lyman shot them, it sank immediately. Of course, he wasn't in it alone. Lynk, after his first scare, was let in on the gag. And, several townsmen were enlisted. They made sure the professor couldn't kill the monster by removing the shot from his shells before the hunt.

Clarks residents evidently took the whole joke in good humor. They hoisted the "sea horse" to the top of the Union Pacific Railroad water tower where it remained for quite some time. All in all, the professor probably got the worst of the deal. Each time one of the kids in town saw him, they would call out "sea horse", and he would chase them. For him, the torment of the hunt was to last for quite a while. In time, the monster disappeared. Some said it was last seen headed west on an outbound freight train. But, whatever happened to the sea horse of Prairie Creek, it was cause for considerable stir and a host of chuckles for Uncle Lyman, Lynk, and the hunters from Clarks. THE END

Chrismons

Festive decorations are a part of the holiday season. But these ornaments go even deeper with holy significance all their own

CHRISTIANS worship and express their love for the Christmas Child in many ways. Hymns and anthems laud him. Special services are leld in his honor. Homes and rches are decorated during the Christmas season with lights symbolic of the light he brought to the world.

Symbols and word pictures are used in the Bible to glorify God. Christ used parables, such as the one about the good Samaritan, to demonstrate divine love. He used representative characters like the good shepherd to describe himself and his work. In the Old Testament, sacrificial acts of worship foretold the coming sacrifice of Christ. Numbers and symbols are used to convey divine truth.

Throughout the centuries, man used symbols. The scroll is symbolic of the written word and prophecy. The six-point star identifies the Creator.

Christians use symbols to demonstrate their faith. The five-point star represents Christ's Epiphany. The rose symbolizes Christ's birth, the shell his baptism, and the butterfly his Resurrection.

During the last 14 years, members of the Lutheran Church Of The Ascension at Danville, Virginia have used Christian symbols to decorate their Christmas trees. In 1940, an elderly Lutheran pastor visited the home of Mr. and Mrs. Harry Spencer in West Virginia. He saw some unused Christmas wrappings in their home and asked if he might

have them. He wanted to use the colorful paper and ribbons for decorations

on the tree in his little church because

his congregation had no money to buy

any. Mr. and Mrs. Spencer were deeply

impressed by this pastor's devotion to

his work, and even more impressed

when they saw what he did with the

colorful wrappings.

have them. He wanted to use the colorful paper and ribbons for decorations

on the tree in his little church because

his congregation had no money to buy

any. Mr. and Mrs. Spencer were deeply

impressed by this pastor's devotion to

his work, and even more impressed

when they saw what he did with the

colorful wrappings.

In the years that followed, the Spencers made their own decorations for their own trees at home, styled after those first ones made by the pastor they knew. They felt a Christmas tree should portray a Christian message, but did not know just how to convey it.

The family moved to Danville, and in 1957 Mrs. Spencer volunteered to decorate the tree in the Lutheran Church Of The Ascension. She thought of different ways to emphasize the Christian message and researched the history of Christian symbols. She eventually came across some historic designs, called them Chrismons, and chose them as her theme. Chrismons is a combination of two words — "Christ" and "monograms".

There were only a dozen Chrismons on the tree, but that was the beginning. From that time on, new decorations appeared each year, incorporating the same symbols, and the idea spread to other churches, including some in Nebraska.

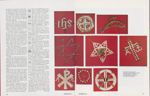

In May of 1970, the American Lutheran Church Women of Our Saviour's Lutheran Church expanded on the idea, gathered the necessary information, and organized themselves for the task of making more. They made several different kinds, but carefully preserved the historic design and significance of each.

Chi Rho with Alpha and Omega is the next symbol. Chi Rho, which looks Iike XP put together, are the first two letters of the Greek word for Christ. It is a monogram representative of his office. Alpha and Omega are the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet. Added to Chi Rho, they indicate that Christ is the beginning and end of life.

The third symbol, lota Chi (IX together), combines the first letter of Jesus' given name with the first letter of his title —Christ. It is sometimes called the Saviour's Star. The fourth Chrismon is the Saviour's Star in a circle, symbolic of eternity.

The Son-of-Righteousness symbol is Chi Rho on a globe from which a 12-point star radiates, representing the 12 apostles.

The cross with Chi and roses tells of the risen Christ with the first letter of Christ's name on the cross. The roses represent rebirth brought about by baptism.

The crown is another. It is simply beautiful. It means the newborn babe of Bethlehem is King of Kings, Lord and Ruler of all.

The Greek cross, with four equal-length arms, tells of Christ's love for mankind, which was so great that it led him to death on the cross in atonement for all of mankind's sins.

A cross with Alpha and Omega on it symbolizes the man who died, and his divinity as the eternal Son of God.

The lota-Eta-Sigma (IHS) symbol includes the Greek alphabet's first three letters of the name Jesus, which means "the one who saves". This is the name of the Infant who lay in the manger.

The butterfly on the cross together with Chi in a circle are symbolic of Christ's Resurrection from death and his power to forgive sins. The butterfly is the symbol of Resurrection because it emerges from a cocoon, just as Christ emerged from his tomb at Golgatha.

The eight-point star is the symbol of rebirth through baptism. Man, who was dead in sin, is brought back to life through this act.

The orb, a cross set on a globe, means the entire earth is Christ's domain. Artists often depict Christ holding the earth.

The fish is the symbol of Christ himself. It comes from the word FISH made up of the first Greek letters of the phrase 'Jesus, Christ, Son of God, Saviour".

Variations of these symbols are used to point out the meaning of Christ in the lives of humans. These symbols and monograms are visual expressions of faith in the Child of Bethlehem. They strengthen belief in the saving power of the Child God gave to man as a gift, and enrich the lives of people during this season when they celebrate the birth of Christ. THE END

36 NEBRASKAland

Destiny of the Goose

Hunting Sand Hills honkers hangs in balance. Success of project could spell future for these majestic birds

SINCE TIME eternal, Nebraska's Sand Hills have fulfilled the needs of nesting Canada geese—at least until this century. The last known nesting in the Sand Hills was seen by a group of bird watchers early in the 1900's. Until the past few years, no successful goose nests have been reported in the wilds of Nebraska. Recent developments, however, promise to change all that and offer Sand Hills gunners unprecedented opportunities to down more of these magnificent birds and still leave a healthy population.

Restoration and release programs sponsored by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Montana, North Dakota, and South Dakota, as well as state-sponsored programs, are largely responsible for an upswing in dark-goose activity. Nebraska's recently initiated program to reintroduce nesting birds to the Sand Hills will hopefully help bolster the Canada population within several years. South Dakota's highly successful program operates just across the boarder and is a (Continued on page 63)

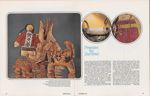

Indian artworks and crafts, once cherished by a proud people, are now residue of ravaged race

Premise for Survival

IT WAS A BLEAK land, this Nebraska before the coming of the whites. Thousands of square miles stretched to distant horizons, halted only by nature's boundaries. And, across this land walked a singular man— the first American.

Neither Sioux nor Cheyenne, Arapahoe nor Pawnee were alone. Their beliefs reflected natural surroundings and their tools, arts, and crafts fitted the wild plains which they roamed. Much of that simple existence, though, was destined to fade as years crept into centuries. Religions were inundated by the flood of Christianity and life-styles were altered by the dogged pursuit of white progress. Now, only remnants of their skills and artwork linger for 40 NEBRASKAland

Arrow points and stone axes, once tools of survival, rest in the florescent glow of display cases. Buffalo-hide tepees and earthen lodges which once sheltered families whose lineage stretched to the dawn of time, remain today simply as curiosities. Ceremonial garments, once raiments of noble tribesmen, adorn lifeless mannequins in pseudo recreations of the majestic heritage of a proud people.

Superficially, fragments of a civilization, whose basic precepts have never been completely assimilated by the prevalent society, seem a bit sad. Deeper, though, lie the cornerstones of a culture attuned to a primitive land and the environment from which they sprang. Amidst the artifacts of such ancient societies lie some clues to understanding the Indian way DECEMBER 1971 of life. Paramount among them are the arts and crafts practiced to perfection, rivaling modern man's in their beauty. Yet, they are often paradoxical. Vestiges of an advancing people mingle with original objects, often obscuring what is Indian and what is not.

Plains tribalism dates to prehistory with recovered objects tracing both its growth and location. Diminutive clay pipes and tiny statuary portray, for the modern scholar, a way of life long since past. And, among the artifacts is the evidence of change. Before the white incursion, objects were rough-hewn and elemental. But, as trappers and traders crept into the region in ever-increasing numbers, the artifacts became more refined. Herein lies much of the difficulty.

Beadwork has long been associated with

the Indian culture. Yet, it was not until the

43

The Indian also took the white man's trade goods and fashioned them for his own uses. Toward the end of the Eighteenth Century, metal trappings began to appear on Indian clothing. From precious metal to tin, objects were cut apart and used to sheath sinue thread from which hung horse-hair bobbles.

Though it was far from a white innovation, war took on a new spectrum with the white man's arrival. Weapons which had been made of flint and sticks, bone and stone, were suddenly embellished with metal spikes and blades; brass tacks embedded for adornment. And, of course, firearms crept into the Indian arsenal. Still, in comparing the most primitive of clubs with later versions, a whole vista of armament improvement unfolds.

And, so it went. Pottery, once so important to the farmer, was replaced with ironware. The nomads' baskets and bags, crafted from native grasses and colored with clay and berry dyes, gave way to commercial varieties bought with pelts or an occasional curiosity. Two worlds met in the castoffs and misplaced articles anthropologists now call artifacts. It is the way of things that the fittest survive. In the wild, the process serves to improve the species. In the repression of a race, its art, and its crafts, the premise is not so beneficial. THE END

Genealogical Fun

Libraries, museums have much to offer, but building family tree must begin at home. Elders are great help

DURING THE LAST decade there has been a tremendous surge in the search for authentic, historical material. Old furniture, once destined for farm junkyards, is snapped up by collectors, refurbished, and placed in homes as valuable antiques. Dog-eared documents, forgotten in dusty attics, are discovered by history buffs, carefully flattened, and framed to be hung in prominent places.

Along with this fascination for ties with the past has come another interest — the family tree. Profession for some, hobby for others, genealogy has become a household word where once it could hardly be spelled. Formerly reserved for the elite, collecting documented family history is now a common pastime at every level of the social structure. With the slow disappearance of snobbery concerning ancestors, it's fun when a black sheep can be found somewhere in the annals of a clan, adding color and spice to an otherwise dull inventory of names and dates.

Genealogy is a fascinating hobby which lures enthusiasts into periods of history previously unknown to them except as vague recollections from school days. For the serious buffs, it becomes a fetish, always in the back of their minds, making them ever alert to new discoveries.

The trick is how to start.

Without question, the beginning of a family tree must be in the home. Historical societies, libraries, and museums are co-operative, but people familiar with material available in their institutions can do nothing unless they have something to work with. Their help really comes in the final stages of research.

Three basic steps must be followed. First, collect as many names and dates as possible from family records. Second, obtain documents which give authenticity to this initial material. Then, research it further to add color and life to the bare structure of your family tree.

For the beginner, the best place to find names and dates of immediate ancestors is in the family Bible. Although this custom has diminished to some degree, it was common until early in the Twentieth Century for family information to be recorded on 46 NEBRASKAland special pages inserted between the Old and New Testaments. Other sources are elderly relatives.

Time and again, disputes arise about dates pertinent to the family's history. "Just ask Aunt Sarah — she'll know," is the usual solution. It's a good idea to stay in Aunt Sarah's good graces in order to be able to tap her memory whenever possible.

Diaries and journals often kept by pioneers, particularly those with a better-than-average education at the time, are especially valuable references. They are also great items for your collection. Letters, identifiable photographs, account books, newspaper clippings, or even needlework attesting to the lineage are other materials from which information can be gleaned. Family legends, although their credibility must often be questioned, usually have at least some truthful basis.

Jotting down every bit of information you collect is essential. This prevents duplication of effort when you refer back to what you have done. Also, keep a detailed list of resources that prove fruitless to avoid looking there again. Such documentation will prove invaluable for future generations who may carry on with what you started.

A lineage chart is necessary for arranging data. At a glance, a specific ancestor's position on the tree can be determined. This chart, incidentally, can be decorated with suitable sketches relating to periods in which the ancestors lived and it may be used as an attractive wall decoration.

An accompanying record book should list the father and mother of each family at the top of an individual page. There should be a separate page for each married child.

Names and birth, marriage, and death dates are essential before moving to the second stage.

Having organized your information, you are ready to write to various places for documents, depending on where your ancestors lived. The U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare is a good place to begin. The department publishes booklets listing places throughout the United States where to write for the certificates you want. For instance, to get a reproduced birth certificate in Nebraska, the booklet tells you to write to the Bureau of Vital Statistics, State Department of Health, State Capitol, Lincoln 68509. A small fee is generally charged in each state. Cost in Nebraska for a birth certificate is $2. An additional notation in the booklet states that available birth records date to 1904. If the needed certificate is for someone born before then, write to the State Historical Society for suggestions. Other publications prepared by the department list sources for obtaining marriage and divorce certificates.

Once you have obtained these booklets, your next step is to write to the appropriate office, enclosing the correct fee.

Other valuable sources of information are wills or probate records filed in the county court where a person died, tax and assessment lists in the city or county clerk's or treasurer's office, and naturalization records in federal district offices, although these tell little about a subject. Land records, usually filed in the county clerk's office, are helpful. They range from homestead certificates to military bounty lands and private claims. Property deeds list both grantor and grantee, and show the duration of ownership, thus suggesting the length of a person's residence in any one place unless, of course, he dealt in real estate. Cemetery records have tombstone inscriptions which can provide missing details.

The State Historical Society has Nebraska census enumerations, lists of people who lived in certain areas at the time, for the years 1860,1870, and 1880 on microfilm. The 1890 list, however, was destroyed by fire in Washington D.C. in 1921, and the 1900 census has not been released. From 1910 to the present, census enumerations are not public, and to get information from them involves a complicated procedure through the Federal Census Bureau of the U.S. Department of Commerce at Pittsburg, Kansas. For information write to Immigration and Naturalization, 215 North 17 Street, Omaha.

In addition to the federal enumerations, there is also a state census list for 1885 on film. As far as the Nineteenth Century U.S. mortality schedules are concerned, you have a 10-percent chance of finding information about an ancestor if you do not know the exact year in which he died. If you know the year, and it is 1859, 1869, or 1879, you are in luck, since federal marshals were required to list the names of all people who died in their areas before June 30 of the following years. Information gleaned from these lists can be helpful in correctly linking your lineage. Mortality schedules include the age, sex, freedom or slavery status, marriage date, occupation, length of illness, and cause of death. The 1880 mortality schedule also lists the birthplaces of the parents of the deceased.

Whenever you build a family tree, you work back from the present. More often than not, this method will take you to some date when your ancestors were European or Oriental immigrants. Consider yourself extremly lucky if you can find the name of the ship on which they crossed the Atlantic or Pacific oceans. Passenger lists for many of these vessels, although certainly not for all, have been compiled and can be valuable sources of information about the voyage. Names of publications which include such passenger lists are available in city libraries. If your ancestors came from Africa as slaves, your chances of finding information about them are one in a million because their names were not recorded.

Although your research may already have taken you to the museum or historical society, you now should begin earnest consideration of what they have to offer. Sometimes you'll be lucky; other times your search for more information will fizzle out. Mrs. Louise Small, librarian at the State Historical Society, points out that genealogists face numerous difficulties. For one thing, the society does not have the personnel to do the research that is often requested. All she can do is tell genealogists what is available, and let them dig on their own. Another thing is that it is very difficult to find additional information on people who came to Nebraska during the second half of the Nineteenth Century.

"You had to be either famous or infamous to (Continued on page 62)

Journey with a Mission

Taunts become test as state's angling forecaster takes up rod and reel to defend the validity of his own reports

48 NEBRASKAlandFLAILING TYPEWRITER KEYS and a cold shoulder did little to spare Ken Bouc from his cohorts' taunts. Ken, special-publications writer for the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, is the middleman between the commission's field personnel and the biweekly fishing reports sent to newspapers across the state. Over the years, Ken has become the scapegoat for every unsuccessful fishing trip launched and sunk by office personnel. This particular day was no exception, and the harassment came to a head when one disgruntled angler put the value of Ken's fishing reports on the block.

"You've been sitting behind the desk so long you probably can't tell a kokanee from a red snapper, much less catch one or the other. Furthermore, by the time those reports come out they are outdated and only tease anglers by telling them how fishing was last week. Why don't you put your money where your mouth is and follow your own reports for a few days, then come back and tell us how you did. And, just to be sure you don't stretch the truth, we'll send a writer and photographer along to document the whole episode." While Ken was more than eager to get out of the office, he was a bit reluctant to accept the challenge. A few well-aimed jabs, however, finally forced his hand.

The trip was agreed upon, and I drew the honor of recording the event. A minimum of ground rules were laid: Ken could fish any body of water for any species with any gear, providing he followed the tips of his last news release. The entire state and three full days were at his disposal.

We were slated to pull out of Lincoln and head west before noon just after the Labor Day weekend, but Ken's cantankerous superior put a damper on that. The clock marked six as we grabbed a hamburger for supper on the way out of town.

Ken's assorted equipment bristled from the back window of our station wagon as we whipped down Interstate 80 toward Harlan County Reservoir just southeast of Alma, since

Ill winds blew over our junket from the very beginning. As if a six-hour delay in departure were not enough, all accommodations in the bustling little resort town were occupied. An impassioned discussion on the merits of motel reservations ended with condemnation of my let's-look-them-over-when-we-get-there attitude. A receptive motel operator in nearby Republican City saved us from sleeping in the car.

The night was young as far as catfishing went, and that seemed a good way to make up for lost time. A local information dispenser, also a short-order cook and bartender, equipped us with life jackets we needed to fish the spillway, a handful of locally recommended silver spoons for the next day's white-bass outing, and enough shad gizzards to entice a limit of cats, or at least give us that instant fisherman's smell.

Before long, we were wading darkened shallows to the boiling basin below the dam where one other fisherman was trying for cats. We rigged up with about three ounces of lead and some of the most foul-smelling shad gizzard ever to decorate a hook. Leaky waders dampened our legs, and our companion dampened our enthusiasm. Flatheads had been hitting well a few days earlier, but the action was tapering fast, he told us. His offering of salamander and shad had yet to entice any customers.

He retreated to his camper and a warm sleeping bag to wait out the early evening doldrums as we added more weight in an attempt to keep our lines in the turbulent water. We passed the time of night swapping old fishing yarns while waiting for action.

I wasn't quite sure about Ken's jinx. Office ribbing sometimes must be taken with a grain of salt. He told me about a trip he and some cronies had made to Harlan for white bass. After 20 minutes on the lake, the wind came up and kept the whole outfit off the water for the rest of the weekend. It seems the same thing had happened once at McConaughy. It still wasn't bothering me that much, though, even after he told about a spring trip to Red Willow for bass. That was the time the temperature shot up to 106 degrees and the fish, of course, did not bite. My mind was still open to give him the benefit of all doubt when he told about a fishing trip to Minnesota where his two buddies caught their limits of walleye while he drew a blank from the same boat with an identical rig. But, I suddenly knew we were in trouble when he reeled in to check his bait and snapped his rod into two neat pieces.

I said not a word as we drove back to town, hoping that what I was beginning to suspect would prove to be a series of flukes. After all, Ken couldn't be a voodoo. Or could he?

We were up with the first hint of dawn the next day, eager to sample the piscatorial pleasures of Harlan's white (Continued on page 59)

50 NEBRASKAland

ON THE TRAIL OF THE KIOWA

(Continued from page 15)only from a distance and failed to make contact. That left plenty of time for troopers to dwell on the march. By July 22, they noted that the column, 44 days out of Fort Cobb, had marched for 41, laying over in camp to rest for only 3. In that time, they covered 743 miles with the longest day's push being 50 miles and the shortest 2 for an average of 18 miles per day. Virtually sailing across the landscape, the troops were tired, their mounts exhausted, and their ranks dwindling. As they moved, soldiers whose enlistments were up simply split off and headed for home with no one to take their places.

By August 1, though, the men were on the Big Saline Fork of the Kansas River in northern Kansas. Signs indicated the Kiowa band they were after was no more than seven days ahead —their first contact was close at hand - perhaps just over the border of Nebraska Territory. The exhilaration of impending battle seemed even closer when an advance party of Indian scouts swooped into camp brandishing three Kiowa scalps —the blood still dripping from them. Camp was struck immediately and the column surged ahead to find only one other dead Kiowa in their path. But toward sundown, a band of some 50 enemy braves appeared on the horizon. Sturgis ordered his men into pursuit, the contact was lost without conflict, and the first real Indian scare of the expedition dwindled.

Three days later, danger reared its ugly head again. On August 4, 6 Indian trailers were ambushed by Kiowa. Capt. Sturgis later wrote that two of his trackers were killed on the spot, one lingered for a time, then died, and three others were wounded. Three enemy braves were killed in the skirmish and several others were wounded. To close the gap between his column and the fleeing Kiowa, Sturgis quickened the pace.

By August 5, the First Cavalry was camped on Sappa Creek in southern Nebraska Territory. The next morning, they were on the move again when they crested a small knoll not more than two miles from camp. Only a few rods ahead were 30 Kiowa, armed and ready for battle. Without so much as a command, the advance guard for the military and a detachment of 30 men lit out after the Indians. Evidently, the Kiowa got the better of their warlike instincts in the ensuing chase, because they dropped everything from lances to rifles to pistols to bows and arrows. Even a few primitive saddles were tossed aside as they lightened the load in hopes of escape. Their tactics paid off, too, because as Indian and trooper pulled out of a choppy stretch onto level plains, the Kiowa easily outdistanced their pursuers. The bluecoats rejoined the column.

The same cat-and-mouse episode seemed inevitable some 15 miles farther along when about 50 Kiowa warriors popped up before the command. They were about two miles away, but Sturgis decided to try for them anyway.

A company of troops and about a hundred Indian trackers were ordered to move on the enemy. As they did so, what had been 50 Kiowa suddenly multiplied into more than 500. Still, the die was cast.

The trackers were first into battle and two of their number were killed almost instantly. Three others were wounded. Estimating enemy dead and injured was a bit more tricky, though, since one observer noted the majority were strapped to their mounts. Kiowa casualties were put at three dead with hopes for more.

By then, the main military force was advancing on the Kiowa and, as the charge was sounded, the enemy began to fall back. They weren't quite quick enough to escape the fast-moving First and Third Squadrons. Though the First didn't get close enough to inflict much damage, the Third poured volley after volley into the fleeing Indians and several fell while others reeled in their saddles and rode off. When the main body of cavalry arrived on the scene, however, there were no Kiowa bodies anywhere in sight. Nevertheless, pursuit continued and as the bluecoats topped the last rise above the Republican River, they saw their quarry escaping on the far bank. Hoping for another, more decisive encounter, the cavalry gave chase for some eight miles before turning back when their mounts proved too slow.

In his report to the War Department, Capt. Sturgis later recounted the battle: "In our front lay a level plain-say a mile wide —intersected by numerous ravines and contained between a low ridge of hills on the north and a heavily wooded stream on the south. As we approached, the enemy poured in from every conceivable hiding place until the plain and hillsides contained probably from 600 to 800 warriors, apparently determined to make a bold stand." The ensuing charge dispersed what must have seemed a wall of Indians. "The whole scene now became one of flight and pursuit for 15 miles, when they scattered on the north side of the Republican fork, rendering further pursuit im- possible."

While the main column was engaged in a deadly game of hide and seek with the Kiowa, the supply train, left behind in the heat of the moment, was having its own problems. A small band of Kiowa swept down on it, intent on killing as many of the whites as possible and making off with both stores and stock. They did manage to take eight ponies belonging to the Indian scouts, but left four dead and five wounded on the Nebraska sod for their trouble.

One straggler was in trouble, or so it seemed, about the same time. The soldier was on his way back to the main column astride a played-out mount when a party of eight Kiowa rode down on him. Ready to give up neither the only horse he had nor his life, the trooper drew his saber and prepared to make a stand as best he could. As the savages rushed him, he hacked the ends off three lances and dispatched their owners. He was still occupied with the fourth when help arrived and drove off the rest. Besides combat experience, all the soldier got were superficial leg (Continued on page 55)

Outdoor Calendar

HUNTING Squirrel-Through January 31, 1972 Cottontail-Through February 29, 1972 Deer-(Archery)-Through December 31 Duck-Through December 20 (east) Through January 9 (west) Goose-Through December 15 Pheasant-Through January 16 Quail-Through January 16 Nongame Species-year-round, statewide State special-use areas are open to hunting in season year- round unless otherwise posted or designated. Hook and Line Snagging Archery Hand Spearing Underwater Powered Spearfishing FISHING -All species, year-round, statewide -Missouri River only, October 1 through April 30 -Nongame fish only, year-round, sunrise to sunset -Nongame fish only, year-round, sunrise to sunset -No closed season on nongame fish. Game fish, August 1 through December 31. STATE AREAS State Parks-The grounds of all state parks are open to visitors year-round. Park facilities are officially closed September 15. Other areas include state recreation, wayside, and special-use areas. Most are open year-round, and are available for camping, picnicking, swimming, boating, and horseback riding. Consult the NEBRASKAland Camping Guide for particulars. FOR COMPLETE DETAILS Consult NEBRASKAland hunting and fishing guides, available from conservation officers, NEBRASKAlanders, permit vendors, tourist welcome stations, county clerks, all Game and Parks Commission offices, or by writing Game and Parks Commission, 2200 N. 33rd St., Box 30370, Lincoln Nebraska 68503.ON THE TRAIL OF THE KIOWA

(Continued from page 53)wounds. His horse, though, was run through with a lance.

An Indian scout fared not so well. When his body was recovered, 21 arrows were counted protruding from it. Having abandoned the chase, the main column headed back to their wagons to set up camp. During their return, Kiowa were seen galloping back and forth on a ridge some three miles away. Fearing a night attack, the troopers spent a good deal of time on alert. The onty alarm came with the discharge of a pistol, however. A quick investigation turned up a soldier seeking solace at the bottom of a bottle. He was promptly disarmed.

The morning of August 7, Sturgis' command, doubting any chance of further contact, headed for Fort Kearny and needed supplies. As they crossed the Republican, several enemy corpses were found along the banks. Shot with poisoned arrows, presumably by the Indian scouts, their bodies were almost twice their normal size. They were unceremoniously scalped and the column continued its march to the Platte. Between August 3 and August 6,1860, Capt. Sturgis estimated that his troops and their Delaware and Tonkowa trackers killed 29 Kiowa. He made no mention of the total First Cavalry casualties.

By mid-August, the First was camped some two miles west of Fort Kearny awaiting orders to move south while they drew supplies. Word at the Nebraska post had it that an estimated 1,500 Indians, herding thousands of horses, had crossed the Platte River a scant 14 hours ahead of the troops' arrival. The consensus was that they were the main band for which Sturgis' command had been searching but never found.

After four days at Fort Kearny, the First U.S. Cavalry headed back for Fort Cobb. Their mission had been moderately successful. They had made contact with the enemy and, though they didn't exactly annihilate the Kiowa nation, they had exacted some measure of punishment on them. It was to be seven years before the Kiowa signed the peace treaty they had been seeking when Big Pawnee was murdered. And, Capt. Samuel D. Sturgis was to become Brig.-Gen. Samuel D. Sturgis. But as the First Cavalry wound its way toward home and the Kiowa band pushed farther north, neither future event seemed very important. Only the deaths of comrades from both sides mattered amidst the trail dust. THE END

RUNNING THE SHALLOWS

(Continued from page 18)but fried chicken must have been sounding better all the time.

"It's getting late. Let's go see how things are coming," he agreed.

"Right behind you," Larry said. "In fact, I may get there before you," he DECEMBER 1971 yelled, his words floundering in the roar of his propeller.

Amidst rooster tails and ruffled water, the trio of hulls skimmed downriver toward Dwayne's home. En route, sure enough, they encountered George Arps, tucked in next to an island, eight channel cats ranging from the three-pounder down decorating his stringer.

"They're taking crawdads," he explained as he plunked the speckled, shiny critters onto the bow of his boat. George, who uses his craft almost exclusively for fishing, has one of many on that stretch of river. Although still not common everywhere, airboats far outnumber their conventional cousins along certain sections of the Platte.

"Airboats really are just coming of age," Dwayne explains to anyone who asks. They have so many advantages in this type of water that they can't be compared to any other boats. We had trouble with the first ones we built, though. They were made of plywood covered with fiberglass for waterproofing. After a while, the plywood joints worked loose, though, and we found them too tough to repair. That's why we went to molded hulls. I had a special form made, and now we produce solid, one-piece shells with four embedded reinforcing braces running the length of the hull. We attach the front motor mounts and storage compartments to them.

"I put bucket seats in some, but prefer to use regular boat seats because they can be folded down to make beds. I also like a foot accelerator better than a hand throttle since river travel requires frequent speed changes."

Large loads do not pose much of a problem, but bridges do. Some of those over the Platte are fairly low, leaving only a few feet of clearance for the protective metal cages which shroud the boats' propellers. When the river is running high, such a close tolerance can put the kibosh on everything by trapping the boats between spans. Luckily, the river is low most of the time, so airboaters are footloose and fancy-free.

Arriving dockside, Carol and her basket of chicken were piped aboard, and within minutes the entourage was cutting wakes toward Two Rivers. No picnic could have been scheduled for a more opportune time. It was one of those ideal days with absolutely clear skies. A bright sun yielded delightful warmth. Beaching the craft right below the pic- nic tables, food was soon being transmitted to the inner reaches of Dennis and Gary's troubled areas.

"Let's take a short run up the Elkhorn to see how the river looks," Dwayne suggested to his boys. "Then we'll come back down and you guys can ski just below the junction. There should be several hundred yards where there's almost two feet of water. Brad, why are you staring into that can?"

There's a bee in there," No. 2 son revealed, easing up to grab a stick. "Is there any more pop? Let's go skiing." All Dwayne could do was agree.

It's always pleasant to remount an airboat. Perhaps the hulls could be fitted with skis or runners for use on ice or snow. Then, the thrill of whipping along the Platte's twisting course could be enjoyed year round. Anyway, during the warm months, few diversions offer more excitement. And, even fewer make it so easy to imagine yourself in the cockpit of a bi-winged Stinson closing in to strafe an enemy airfield. Where's my flying suit? THE END

HEP FOR BEAVER

(Continued from page 21) it. Beaver trappers, too, are nuts like that."As we drove toward the first trap, Hap described his work. He estimated he had about 50 sets for beaver and 200 or so for muskrat. Ideally, the traps should be visited each day, but since he traps in Saunders, Cass, and Otoe counties, it takes two days to check them all. That means he is on the road before dawn and doesn't get back until dark.

"If I get three beaver a day, I call that good. I've taken as many as eight. Of course, some days...." He left the thought hanging.

The season, which runs from the middle of December until late February, usually brings Hap 70 to 90 beaver. An excellent year might bring him 150.

Like all good sportsmen, Hap respects his prey. "I like beaver. I never get tired of watching the way they work and play. They're smart, clean, and, most of all, ambitious. That's what causes trouble.

They don't belong near farmland. They can cause considerable damage, and when they become a nuisance I get a call."

Trappers, he explained, work closely with both game warden and farmer. Together, they decide when beaver should come out of an area.

What damage do they do? We parked the truck and hiked across a cornfield toward the traps. As we neared the stream, damage became obvious. Cornstalks had been sheared off about 12 inches above the ground.

Beaver wait until corn is mature, then shuck it very neatly and stash it in dens along a stream's bank.

"One time," Hap recalled, scanning the stripped corn row, "I caught a pair which had cached away about 15 bushels — almost filled my pickup. They laid it away carefully, too, stacking it up rick fashion."

Not only must the farmer contend with crop loss, but storage dens cause washouts, promoting field erosion.

"A big den can be dangerous to a farmer driving a tractor. Why, just last year a man was killed while mowing. The wheel fell through and the blade got him." A further danger, he added, is that cut trees leave stakes sharp enough to puncture a tractor tire. "No, I love beaver, but they don't belong on farmland. They must be kept near the river."

Our brisk pace was interrupted as we Eushed aside branches and stepped over eaver cuttings. The sun's warmth had softened the stream's bank and Hap momentarily lost his balance, caught himself, and waded into the water where he lifted a sprung empty trap. He examined its jaws, shrugged, and undid the heavy (Continued on page 59)

Where to go

Hemingford Christmas Diorama, Anna Palmer Museum