Where the West Begins

Nebraskaland

November 1971 50 cents

For the Record... RECREATIONAL VEHICLES

The 1971 Legislature downgraded minibikes from the motor vehicle classification, ruling them off the road, and enacted legislation providing for the regulation and registration of snowmobiles. These actions have focused attention on all powered recreational vehicles, including snowmobiles, trail bikes and other cycles, all-terrain vehicles, and four-wheel-drive units.

These devices have several common features: they are designed for offroad use; they are noisy; they are deleterious to the environment in varying degrees; they are within the means of most families; and last, but by no means least, they are a lot of fun. Properly used and controlled, they contribute to the "good life" in outdoor recreation.

Growth of the popularity of these devices has been sensational. Between 1960 and 1962 annual sales in America were calculated at only 155,000 units, but by 1970 annual sales skyrocketed to 1,800,000 units, with gross sales reaching almost a billion dollars.

As in all aspects of outdoor recreation, this growth is the product of higher personal income, vastly increased leisure time, and a continuing shift of population from rural to urban areas. These and related factors are projected to result in annual sales of 2.5 million units by 1980 with the end still not in sight. The industry is busy searching for new enticements to offer an eager market, which took a look at the snowmobile to the tune of 10,000 purchases in 1960, liked what it saw, and by 1969 was buying snowmobiles at the rate of 317,000 units a year.

Standing in the wings are air-cushion, all-season, and electric-powered recreational devices, along with whatever else designers can come up with.

Because of the unpredictable snow cover over most of Nebraska, we will escape most of the snowmobile boom that has taken over the winter outdoor scene in the snow-belt states, but all Nebraskans would do well to concern themselves with the impact of recreational vehicles that are practical here.

Upon the purchase of a recreational vehicle, the new owner is immediately confronted with the problem of where to operate it. Understandably, his first thoughts are likely to turn to public recreational lands. Administrators of such lands, universally beset with funding problems, recognizing the owner as a minority user, deriving no direct revenue from the licensing or operation of these devices, and recognizing the potentially deleterious environmental impact, just as understandably take a very dim view of the whole situation.

In Nebraska there are some public lands where some classes of recreational vehicles could probably be operated under supervision with controls adequate to protect the environment, other visitors, and wildlife. At this point in time, however, this commission does not have the financial or manpower capability to develop and mark trails, designate and improve special-vehicle areas, or enforce essential control measures. Therefore, the development of a recreational vehicle program in the Nebraska State Park System must be predicated upon the development of funds.

Many administrators, including this one, believe that the ultimate future of recreational vehicles in general public-use areas will be determined by public tolerance of the sound levels produced by these devices. Noise is the single intrusion that directly and adversely affects other visitors. We are convinced that manufacturers and owners of recreational vehicles would be well advised to concern themselves, and deal decisively with this problem before noise places the kiss of death on the entire sport.

Jack Strain Chief, Bureau of State Parks

Speak Up

NOT FORGOTTEN-"I would like to take this opportunity to say your staff does an outstanding job publishing NEBRASKAland.

"Being stationed in Korea for a year is a long time to be away from 'Good Old NEBRASKAland', its people, and our way of life there.

"Since I've been overseas, my wife has been sending me your magazine every month. There's really no way of putting into words how much this means to me, being able to read about back home." — LeRoy Vanek, Silver Creek.

SOMEONE NOTICED-"I have just received my August NEBRASKAland and am very disappointed in the new style cover!

"The cover on the past issues has always been so distinctive with its colorful NEBRASKAland nameplate. One could always pick it out from all the other magazines. But, now it looks just like the common movie magazines that the kids buy.

"I do hope you will seriously consider returning to the distinctive cover you had and keep NEBRASKAland No. 1 - Sharon A. Smith, Schuyler.

STORY TO TELL — "I was very much interested in Warren H. Spencer's article Profiles of the Past in the August issue of NEBRASKAland. Old cemeteries do have a story of interest to tell.

"I would like to mention a cemetery which to me is as lovely as any I have NOVEMBER 1971 seen. It is not only old, but beautiful and well kept. It is the Oakdale, Nebraska cemetery just a short distance south of town. You enter up a long gravel drive to a flat area with beautiful pine trees. To the north and east of this part are rolling hills which are included in the cemetery.

"I do not know how many prominent people lie at rest in this spot, but one I can mention is the late A. J. Leach, a pioneer of Antelope County and author of Early Day Stories, a history of Nebraska written in 1916. His grave lies on the side of a hill at the northeast corner. The monument is a huge boulder with his name and dates carved on it. I do not remember where it came from, but there are those in or around Oakdale who no doubt could tell about it." —Mrs. E. R. Carpenter, Chambers.

WE NEED WATER-"So, the National Audubon Society wants to destroy Nebraskans'

"I refer to NEBRASKAland's For the Record (June 1971) which describes efforts being made to destroy us Nebraskans who are dependent upon the agricultural industry.

"In the 1930's, I helped my father dig an irrigation well here on our land in the Platte Valley near Cairo. He dug that well so that he could stay in Nebraska, so I could stay here, and so my children could stay here. Ours was not the first well in the Platte Valley and probably the last one hasn't been dug. However, all of us farmers must have an adequate water supply to keep ourselves and our families in Nebraska and to support the largest industry of our country — farming. Now, we're not trying to put more land under cultivation; we're trying to use the resources that we have with the best technical and professional skills in maintaining the social wellbeing of ourselves and the rest of the Nebraskans who are dependent upon us. To do this, we must have a dependable water supply.

"When my father dug that well in the 1930's, the aquifer was full of water. This summer I measured the depth of water in the well. Half the aquifer contained no water. If I am to stay in business and to maintain quality of life for myself, my wife, my children, and the rest of the Nebraskans, I've got to have that water supply replenished. Precipitation alone is not sufficient to do it. This is really what the Mid-State Project is all about — stabilizing the ground water and assuring an adequate water supply for the area.

"I have learned from records of the United States Geological Survey that they measured 261 wells in the Mid-State Project area. From their records, they tell me that from the fall of 1969 to the fall of 1970, 254 of these wells showed declines in the water table. The maximum decline was seven feet. Only 7 of these 261 wells showed increases in the depth of the water table. The average decline of these wells was 1% feet. Rainfall for 1970 was less than normal, but no drought.

"My father was an avid hunter, and so am I. In my early days, we did our waterfowl hunting along the Loup River. In more recent years, we have moved to the Platte River. So, I appreciate the efforts to maintain adequate wildlife facilities to provocate the species and to assure a wholesome life around a body of water. However, I feel that we human beings have a certain right to live in this environment; that we are part of the environment and adequate consideration must be given to facilities to protect us." — Bob Lowry, Cairo.

TWISTED TOPICS-"After reading the SOS poems in NEBRASKAland, (Speak Up, April 1971 and July 1971), I realize the endless number of topics these three letters could inspire.

"In all good humor, I earnestly hope some cleaning enthusiast doesn't come forth with 'Scour Our State, use SOS soap pads'."—Mrs. Lorene Moranville, Bayard.

Mrs. Moranville's contribution, S.O.S. — Sell Our State, was later interpreted as S.O.S. — Save Our State by Mrs. Vilma Toufar, Columbus. — Editor.

SAND HILLS SONG-"Enclosed is a poem our daughter wrote in high school this year. We live in the middle of the Sand Hills and the ranch is her whole life." — Mrs. Orville Conner, Gordon.

Looking and Listening by Cameon Conner Gordon Sitting on a big tall hill in the evening dusk, Overlooking the rows and rows of rolling sandy peaks. Listening to the wind brush through the grass. As though it is trying to tell you something. Nothing that's real important, but just something. Watching a hawk with its wings spread wide, Gliding through the sky, with the gracefulness And ease of a feather floating in the wind. A feeling comes over you, too wonderful for words to express, As though everything around you is alive, talking And free as the wind that whispers by. No worries, no troubles, just letting things come And go as they please. Being alone but not alone; just looking and Listening and being there.

HOW TO: BUILD A GUN RACK

Prized weapons deserve display, and this project does that proudly

TO MOST OUTDOORSMEN, owning a fine shotgun or rifle brings a feeling of enjoyment surpassed only by long hours spent in pursuit of fast-flying gamebirds, or watching through the rifle scope as a small, tan spot on a far hillside becomes a majestic, eight-point mule deer.

Shouldering your favorite gun leaves warm and memorable feelings long after the day's hunt has ended, and proper storage and display of these guns require little more than a small place on the wall — and this easily made gun rack.

Using easily obtained materials, a unique display rack can be constructed using tines from a set of deer antlers and a small board of walnut or other fine wood.

The first step in construction requires the selection of evenly matched tines, two for each gun. The tines can be selected from more than one set of antlers if unbroken or matching horns are hard to find.

After the proper tines have been found, they should be cut to approximately five or six inches in length. Sharp (Continued on page 12)

BUILD A GUN RACK

(Continued from page 8)points and blemishes can be removed by using a small grinding wheel first, and then fine sandpaper. Little else need be done with the tines, although personal preference might call for final polishing and a light coat of varnish.

Any type of easily worked wood can be used, but for lasting enjoyment and good looks, fine-grained walnut was chosen for this working model.

Five small boards, two measuring 25 x 4 x 1/2, and two measuring ll x 3 x 1/2 are needed. The fifth, 20 x 3 x 1/2, can be used as an optional shelf. Sizes may have to be changed, depending on the type of guns to be displayed.

Arrange the two longer pieces so they are parallel and approximately ll inches apart. These form the uprights.

Proper placement of the protruding tines can be measured by laying the guns on the uprights in the most satisfactory arrangement. Positioning marks should be made, being careful to center holes, allowing for the horizontal difference between stock and forward hand rest.

Holes should be drilled at the marks, allowing for any difference in size of the tines. A hand drill is

After the holes have been bored and shaped to allow the tines to fit snugly, the wood should be sanded smooth. Start with medium-grade paper if the surface has been scratched or dented. Standard gunstock finishing methods can be used, including wetting the wood between final sandings. A highly polished gun rack is not desired, though, because of a possible conflict with a finely finished gunstock.

Next, glue the two 11 x 3 x 1/2 crossbars between the uprights. This can be done by forming a simple rectangle, or moving either the top or bottom crossbar to find the most pleasing arrangement. A high-bond wood glue should be used and heavy clamps attached to hold the wood in position while the glue dries.

Corner L and T braces, available in most hardware or lumber stores, are used to strengthen joints. These are arranged on the back of the rack, using a drill to make starting holes for the wood screws.

Arranging small L braces to form a triangle with the point toward the top makes a sturdy hanger for the finished gun rack.

Once the glue has set, remove the clamps and touch up the sanding job by removing excess cement. At this time the optional shelf at the top of the gun rack can be attached. The proper shelf length is determined by measuring the distance between the outside edges of the uprights. Fasten the shelf with glue and long wood screws from the back through the uprights to give the shelf strength.

After the shelf is in place, go through the sanding procedure again and prepare the holes for epoxy by taping the backs shut.

After sanding, apply either linseed oil or a standard stock-finishing oil. Some hand rubbing is required to bring out fine grain. Next, glue the tines into the holes, using leather discs or stars to hide finished joints. These must be slipped onto the horns before gluing.

If small children will have access to the gun rack, remember to lock the firearms. Trigger locks or wooden dowels running through the centers of the tines can be used.

Other personal touches, such as carving or shaping the wood or using other common furniture ideas can be added.

All that is left is to hang the finished gun rack where your cherished weapons can rekindle memories of those pleasurable hours spent hunting the wild game of NEBRASKAland. THE END

ICE DOWN THE VORTEX

IT WAS AN early autumn morning in 1935 and my father-in-law, Bob James, and I planned a day of duck hunting on the Missouri River. Long before dawn, we loaded his 15-foot skiff onto his truck in Nebraska City, arriving in Plattsmouth in darkness some time later. Our plan was to float back south toward home.

Bob, a mason and lifelong resident of Nebraska City, was an experienced river hunter. He had made this 30-mile trip many times and liked to float in on large congregations of ducks on the river's sandbars, often easing within 50 feet of thousands. When the time was right, he would pop up, empty his semi-automatic, reload, and row downstream to await any crippled or wounded birds that might float by. There was no limit then, and he often took home several dozen birds. Hunts like those are no longer possible, though, due to the absence of sandbars, eliminated to make the Missouri more navigable, and, of course, regulations have lowered take-home numbers in the interest of conservation.

There was a crisp chill in the air and fallen leaves crunched familiarly beneath our boots as we made our way toward the riverbank. As we slid the boat into the water, we had to give it an extra shove to get it through slush ice that had formed near the bank, but soon we were on our way.

We had gone some distance, waiting for signs of game, when we noticed the boat slowing and grating sounds coming from its sides. Lying flat in the bottom, we could not see, so Bob rose slightly for a look. There was slush and ice across the entire river now, separating here to skirt a sandbar just ahead. It felt as if the boat were riding on ice. By then, we were both up, glassing the river ahead for ducks.

Slowly, an autumn sun topped distant hills and a quiet, misty light played across the colors blanketing both banks.

After a long look, Bob handed the binoculars to me and casually remarked that there was no ice beyond the sandbar we were passing. Still caught in the flow of slush, our speed began to pick up. Suddenly, Bob grabbed the binoculars. Scanning ahead again, he became frantic. That pleased me at first, because I thought it meant ducks.

Then he shouted: "Look!" Fear filled his voice. We zipped along with 14

We immediately knew what to do to avoid being swallowed. I grabbed the front oar and Bob snatched up the rear. A combination of adrenalin power that comes with fear and a good bit of rowing experience edged us slowly, laboriously away from the whirling water. From well to the side of the whirlpool, we looked back to study the phenomenon. There didn't seem to be any visible sign of the ice resurfacing. Where was it going?

From time to time, stories cropped up to support a theory that fast currents surged through the Missouri, in some places forming rivers beneath the sand and mud of the main channel only to emerge into the mainstream at various points along the waterway.

What we were watching seemed to support that theory. Ice was disappearing, seemingly gone for good. We searched for signs of it resurfacing farther downstream, but found none. Maybe there really was an underground flow. Or, maybe, the force of swirling water simply disintegrated the slush. We never found out.

Although that autumn trip turned out to be an unsuccessful hunt, a certain exhilaration surged through us when we had solid ground beneath our feet again. And, the trip home was silent as we both pondered what could well have happened to us that day on the mysterious Missouri. THE END

For Jerry Gamster, pilgrimage from Chicago's concrete canyons to Nebraska's northwest pays off

Panhandle Ringnecks

DESPITE THE MANY self-made promises after the close of pheasant season to get in more time afield next year, it seldom happens. Each year seems to bring more hectic schedules, denying more gunners the simple pleasures of chasing those sneaky, Oriental birds.

Such was the case when the 1970 pheasant season rolled around. Sure, like most other hunters, I managed to get away for a few hours on opening day, but that looked like the end of it for some time. Then Jerry Gamster came on the scene.

Jerry is advertising manager of Fishing and Hunting Guide, and like many other staff members, is an avid hunter. Several weeks before the season he had left his Chicago office to come to Nebraska on business. Hunting was mentioned only briefly at that time, but a later phone call firmed up a date for him to come out for some ringneck shooting.

Airline personnel may have been nervous when they saw him climb aboard bearing two sheathed shotguns, possibly expecting a detour to Cuba or somewhere, but Jerry was perfectly content to head for Nebraska. When he climbed off the plane in Lincoln on November 20, it looked as if he meant business.

Our plans were to hunt in the Panhandle, where some good pheasant hunting had been reported during the first two weeks of the season. It was a long drive from Lincoln, but hopefully it would be worth it. Bright and early the next morning we departed and were ready to hunt all the way out to Crawford.

Early Sunday morning Jerry and I gravitated toward Hemingford. Shelterbelts in that area were touted to be loaded with birds. They were, but that didn't help an awful lot. Shortly after we arrived in the territory, the wind came up like a small tornado. At one place so much dirt was blowing across the road from plowed ground that we had to stop the car. Visibility ended at the end of the (Continued on page 60)

NEBRASKAland

Shoot-out at Sheridan

In backwash of Indian Wars, doldrums often led to discontent. At Pine Ridge post, grumbling exploded into gunfire

BETWEEN INDIAN engagements, soldiers at Camp Sheridan in northwest Nebraska were hard pressed for excitement. A long 40 miles from Fort Robinson and farther still from the saloons of Crawford, the troopers had no way to break routine, and boredom was their daily bread.

The Cheyenne outbreak of early 1879 was over, and Indian action was at a standstill. Located one mile south of the Spotted Tail Agency, the soldiers couldn't find enough hostiles to break the routine, and the agency Indians didn't seem to need the "protection" the soldiers were there to provide. The big excitement of the year came in the fall when prairie fires threatened the post. Then the soldiers were ordered out, armed only with wet gunny sacks, told to burn a fire ring, and see that the onrushing flames did not jump the barrier. The activity was one of great hilarity for men who seemed constantly immersed in monotony.

An early resident of the post described the firings as follows: "Between thrashings at the fire which they had set, several of the men would rush upon some victim and smack him from all sides with the slimy, wet gunny sacks and then, just like children, scream with glee and go back to their chore."

After the fire, lonesome isolation was punctuated only by the yelps of coyotes that sneaked about at night and, in mid-winter, packs of great grey wolves that prowled the region. The men poisoned many of them for skins with which to make carriage robes.

Down by Beaver Creek were hundreds of dogs that had been abandoned by the Indians when they left for the Missouri River. They lived in holes dug in the creek banks and had become as wild as wolves.

Before cattle were brought in, black-tailed deer were plentiful and could be hunted close to the post, providing some sport for the men— but the cattlemen's arrival put an end to even that entertainment.

With the relocation of the Indians, cattlemen drove their herds in and assumed control of the ranges, bringing with them some desperado drovers. There were frequent shootings from then on, keeping the post surgeon busy.

Horse thieves came along with "civilization", and so did road agents, but the Cavalry was not told to 18 NEBRASKAland chase such outlaws, and they provided little break in routine for the troops.

For the entertainment of the soldiers, a kindly man named Sol Martin established a "road ranch" for the cavalry's recreation. Despite Martin's generous assistance, however, the soldiers' boredom finally led to a bloodbath one evening when troopers joined an assorted group of cowboys at Martin's place for a Saturday night get-together. The men were drinking and dancing with Martin's "hostesses" when violence erupted.

There seems to be no verified report of exactly how it happened, but the Pawnee Republican of Pawnee City printed the following details, garnered from a special report sent out from Fort Robinson, in its November 4 issue.

"It began by a drunken Mexican brandishing a revolver and threatening to shoot the bartender for swindling him. A dozen cowboys drew revolvers...."

The roar of a single gunshot erupted amidst the general uproar and Ed Collins lay dead, shot by his own revolver as he drew it. Undaunted by Collins' death, the revelers returned to their dancing and merry making a scant 20 minutes after the unfortunate cowboy was dragged out.

"Jim Joyce and a desperado named Page soon got into a rough-and-tumble fight, however, over the proprietorship of a girl known as Beaver Tooth Nell [one of the hostesses] and it ended by Page shooting Joyce fatally," the report continued.

According to the Republican, Corporal Martin V. Green of the Fifth Cavalry attempted to disarm Page, and was shot in the leg for his efforts. The soldiers then retaliated by firing into the Page crowd, as they retreated into the night.

At this point, the Fort Robinson release stated, women rushed out of the rooms to which they had withdrawn (so as not to be mistakenly injured in the scuffle) and ran screaming about the place. The scene then degenerated into a "general brawl which was said to be dangerous to life and health."

Apparently Martin's "lovely assistants" were caught in the middle of the action anyway, for the report says that (Continued on page 56)

Frothing waters of spillway are not for faint-of-heart or inexperienced, but they challenge this daring crew

20 NEBRASKAlandRiding Super Surf

SLAVES TO THE call of adventure and its mystical song of danger, Mike McAllister, Frank Siedlik, and Arnold Bueoy stood ready to make the death-defying jump. Dedicated drifters on open water in search of the unknown, the trio faced a totally new challenge.

Unlike the wandering cowboy of yesteryear, these highly trained "Drifters" take their name from a closely knit scuba-diving club to which they belong. Experts of the silent world and seekers of all its mysteries, the trio of Omahans leaves no rock unturned in the quest for diving knowhow.

A smiling, have-a-happy-day sun sent golden shafts of light bouncing a million directions off the roaring water below. The divers carefully studied the rumbling current and crushing waves.

Snugging up his jet-black, tailor-made wet suit, Arnold shouted over the roar of rushing water, 'Til go first!"

The scene was at the massive concrete stilling basin of Kingsley Dam, the structure that impounds sprawling Lake McConaughy near Ogallala. The basin was swirling with action that particular late-July day. The basin measures 400 feet long, 106 feet wide at the upstream end, and 250 feet wide at the downstream end. The bowl is 50 feet deep with 24-foot concrete baffles extending from the floor to dissipate the tremendous energy resulting from the discharge of water through the spillway tubes. The frothing water rushes into the basin, primarily from the big lake's control tower, through a tube 20 feet in diameter and 979 feet long.

Arnold looked west toward the howling tube as water swirled into the air, simulating a tortuous, mid-winter snowstorm. The wild spray, laced with colorful rainbows, offered little mental respite as Arnold inched up to the retaining wall's edge. Chilly mountain water boomed from the tube at the rate of 3,800 cubic feet per second, creating several thousand horsepower of energy and shooting from the tube at an initial rate approaching 80 miles per hour. Crushing onto the submerged baffles, the water shot high into the air and sent rolling waves rumbling into the basin wall.

Tugging his hood secure, Arnold flexed his knees lightly and leaped over the side. The fall to water level was about 15 feet. Arnold's entry splash was scarcely noticeable in the confusion of breaking waves. A few heart-pounding seconds raced by before Arnold emerged about 20 feet out from the wall.

The rushing current caught him in full tow as he glided—carefree now—on the wild surf. After a brief ride, Arnold made his move to get back, and a few strong strokes brought the ex-Navy man to the concrete wall.

While the action along the basin wall was rough

and unpredictable, that was where the divers wanted

NOVEMBER 1971

21

to be. Then, at the end of the furious ride, they

would grab the corner of the wall and pull

themselves out of the current to safety. Otherwise, if they missed, the current would sweep

them back into the middle of Lake Ogallala,

meaning a long swim back.

to be. Then, at the end of the furious ride, they

would grab the corner of the wall and pull

themselves out of the current to safety. Otherwise, if they missed, the current would sweep

them back into the middle of Lake Ogallala,

meaning a long swim back.

Arnold made it to the wall, riding high in the rolling waves. In addition to wearing the extremely buoyant wet suit, Arnold and his jumping companions also had on half-inflated life vests. A second later, Arnold reached for the wall's end. He caught it with ease and pulled himself into the subdued backwater.

"Beautiful," he sputtered, gasping for air, "just beautiful."

While it seemed as if Arnold had been in the water for hours, a check with the stopwatch proved otherwise. It was incredible! He had made the watery, action-packed trip in just 11 seconds. The distance back to his jumping-off point was roughly 265 feet. A quick mathematical calculation showed that he had jetted through the water at about 25 feet-per-second.

Climbing up the rocks to the top of the wall, Arnold related his experience to his fellow divers. "Turbulent," he began. "I jumped too far up. The water held me down and I had to swim hard to surface. I think if we move downstream just a bit the water won't hold on so long. It's fast, though, I swallowed my gum."

Heeding their friend's advice, Mike and Frank moved several feet down the wall. Mike was next.

Bewildered, several anglers strained their eyes to see what was going on.

"It would be unnatural for them not to wonder what in Sam Scratch we're up to," Mike pointed out, pulling on his special water gloves.

"But, we love people," he continued. "Sometimes it seems as if we answer millions of crazy questions. This gives us the chance to promote diving, water safety, and interest in our precious natural water resources. This person-to-person communication is actually a big part of diving."

Mike crept closer to the wall's sheer edge and gazed at the roaring water. "Why do we do it?" he asked. "Easy. It's here. It's a challenge, a step into the uncertain. Really, it's just the adventure of it all."

Kersplash! Mike hit the water. He popped up sooner than Arnold had, and wore a mile-wide grin. He bobbed on the waves, looking like a seasoned body surfer on the Pacific. Approaching the end of the run, Mike reached for the corner of the wall. He, too, successfully grabbed it and soon reached dry dock to prepare for another jump.

"Super fantastic!" Mike shouted. "It's really fast, Frank."

Frank was the last Drifter to make his first jump. His eagerness to experience the wild, tumbling ride was evident.

"The degree of risk adds more romance to the jumping," Frank stated. "Only a highly experienced person should ever attempt an ordeal like this, though, and a person can't be friends with fear and still cut it. It's really no different than jumping out of airplanes or climbing mountains, but it's here and it's really

Lightest of the three divers, Frank popped up the quickest. He also zoomed along on the ripping current the fastest. With his arms out like a boy playing airplane, Frank skittered over the water laughing all the way. "Oh, no!" he shouted, as he approached the end of the retaining wall. He was too far out. His powerful arms, conditioned by years of swimming, thrashed the water, but the struggling diver missed the wall. The current tugged at his body, pulling him toward the lake. But, in a final burst of energy, Frank managed to escape the current's clutch and slipped into the backwater.

Still laughing, Frank gulped for air. "It was touch and go for a bit there," he gasped. "You two are both right. That's really something else!"

Each having completed one jump, the divers began comparing notes. It was 7:30 a.m. on a truly beautiful morning.

Some 25 members of the Omaha-headquartered Drifters Scuba Club would each undoubtedly get the intricate details of making the jump. And, although this type of adventure was a bit off base for the underwater explorers, the experience had to be weighed as an important tool of learning.

"I guess I've always been interested in diving," Mike began. The public relations assistant for an Omaha Hospital continued, "Way back when, I had only a snorkel, fins, and a mask. From there I've come a long way. Now I'm a certified scuba diver and instructor."

Skin diving involves only the snorkel, mask, and fins, while scuba diving means the individual is utilizing an air supply and, depending on climate and water, a wet suit. Mike graduated to scuba by way of Bill Pearce, proprietor of Bill's Scuba Shop and founder of the Drifters Scuba Club. Bill has outlets in Omaha and the capital city and teaches scuba techniques in both cities.

Riding something wild and free wasn't new to Arnold, a former rodeo performer. At home, Arnold is a computer programmer, but in the world of the great outdoors, the tousle-topped diver loves action - the faster the better.

The Drifters are much more than pleasure seekers. They play an important role in community safety. Mike, along with several other club members, is on the Sarpy and Douglas counties' Civil Defense underwater rescue team. Also, the divers lend helping hands to a host of "surface" sportsmen who lose everything from boats to watches in the watery depths. The club members go even further by making themselves available for commercial diving as well.

Although landlocked, skin and scuba diving are popular in Nebraska and enthusiast ranks are swelling each year. Two other sanctioned diving clubs exist in Omaha.

"Big Mac is the best lake in this region for diving," Frank noted. "Diving is best in the spring and then again in the fall, with visibility sometimes 35 or (Continued on page 56)

Reasons for Seasons

Compromise is the name of the game when commissioners hear all sides of an issue, then establish periods for legal hunting

HUNTING SEASONS occur each year, yet many sportsmen remain unfamiliar with the procedure involved in setting opening dates, lengths, and regulations. Hunting seasons are designed to provide beneficial outdoor recreation within the limits of available resources and to allow hunters to harvest surplus game birds and animals.

Hunting seasons and game regulations are established by a seven-member board of commissioners which governs the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. The commissioners are appointed by the governor for five-year terms with approval of a majority of all members of the Legislature.

Game commissioners appoint a director who, in turn, hires a staff to carry out responsibilities delegated by the Legislature to the Game and Parks Commission. His staff includes trained wildlife biologists and conservation officers, part of whose job it is to conduct surveys and maintain records on wildlife populations throughout the state.

Information on various game populations is gathered during the year. This data is critically reviewed and compared with previous findings to evaluate population status. It is not possible to obtain total counts, so population comparisons are based on trends.

The commissioners announce a public hearing when regulations or seasons are to be set. After hearing testimony from interested persons and consideration of all aspects, they pass judgment on the seasons to be set. Dates selected are compromises between what is biologically feasible and what landowners and sportsmen find acceptable.

The first step in determining season regulations takes place in February. At this meeting, the commissioners determine the opening date for all hunting except waterfowl and other migratory bird seasons which are set by the federal government. Opening dates are based on several factors: the maturity of young birds or animals to be harvested, crop harvest dates which have a bearing on whether land will be open or closed to hunting; trophy quality in the case of big game; success during past seasons; the reactions of sportsmen and landowners; and time for printing and posting of regulations.

Opening dates are decided in February so that hunters interested in taking vacations during the hunting season or wishing to arrange business schedules to take advantage of the seasons can do so. Maturity of birds to be hunted has a definite effect upon the opening date. Pheasant cocks at 13 weeks of age are easily distinguished from hens. In order to have a season on cock pheasants accepted, the opening date cannot be set too early before the cocks can be distinguished from the young hens. The progress of the grain harvest also affects vulnerability of cocks and affects private landowners' attitudes toward hunters. Since most of the crops are harvested and the young birds are distinguishable by sex late in October or early in November, this is the most acceptable period for opening the pheasant season.

Quail opening is usually set to coincide with pheasant opening because they are often hunted at the same time. Although there is no need to distinguish young males from females, late-hatched quail are not very sporting targets. Small quail fly only a short distance and are much easier to hunt than older birds. Grouse opening is based mainly on distribution and vulnerability of birds. A mid- to late-September opening results in higher hunter success. Grouse gather into flocks beginning in late October and on through the winter. These flocks are much more difficult to approach than small groups or singles late in September.

Fall antelope and deer opening dates are based on the breeding season and crop harvest. If corn is not harvested, the kill on white-tailed deer is very low. Also taken into consideration is the fact that both deer and antelope shed their antlers and horns each year. Males taken after shedding lose their trophy quality. Also, the deer rut has a direct relationship to the quality of the meat.

Turkey season opening date for the fall hunt is usually set just prior to the deer season and usually allows for an overlap of the two seasons. This is done so that hunters wishing to hunt both turkey and deer need make only one trip to the western part of the state, prime range for both species.

The spring torn turkey season is decided at the February meeting. The opening date, as well as the length of the season and the number of permits to be authorized, are all set then. The spring season is set to start immediately after breeding. At that time, hens are nesting but gobblers are still interested in breeding and respond to the imitated call of a hen. The gobbler-only season provides an opportunity for sportsmen to harvest males that are not needed for reproduction. Their removal has no effect upon the future population.

Antelope and deer seasons are set well in advance at the May commission meeting to allow for the issuance of special permits. Both antelope and deer rifle harvests are regulated on a management-unit basis. Nebraska's deer population is distributed statewide with the highest population occurring in the west. Seventeen deer management units allow for distribution of hunters according to the distribution of deer.

Deer seasons provide good recreational hunting, but still maintain population control. The deer population can have direct effect upon crops, so the deer season in Nebraska is designed to maintain the herd within the economic tolerance limits of landowners.

The desired objective determines the type of deer harvest regulations that will be adopted. An either-sex or any-deer regulation results in herd reduction. A bucks-only season allows for herd increase, and a combination of both can be used to stabilize or regulate slight increases or decreases.

A management-unit system is also used to manage antelope. Antelope are located in the western portion of the state, and in order to achieve the harvest desired, permits are limited by unit. Antelope harvest is regulated by the number of hunters allowed in a management unit. Hunting success remains fairly constant regardless of the number of hunters and if too many hunters were allowed to hunt, the antelope population could be drastically reduced.

Cottontail and squirrel seasons are also set at the May commission meeting, but the rest of the fall seasons are set in August. The other seasons are set then to allow for the collection of production data unavailable earlier in the year.

Turkey brood counts are made to predict peak production and are compared with previous annual production. Turkeys are also managed on a unit basis. Quail, pheasant, and grouse seasons are based on comparison production and population levels in previous years. The harvest of upland game by hunters is replacement mortality; not additive. Natural mortality normally claims 70 percent of each year's pheasant and grouse populations (Continued on page 56)

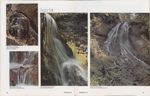

Like precious gems in a royal crown, trees unique to only one part of Nebraska rim jewel-like cascades hidden near Valentine

I HAD HEARD rumors that the waterfalls were there, hidden by heavy timber along the south wall of the Niobrara River Valley, and even more surprising were reports of clumps of paper birch trees common in northern states, but certainly not in Nebraska.

Having poked into most corners of Fort Niobrara National Wildlife Refuge on other assignments, the opportunity to begin my present search along a neglected section of the south wall was welcome. Less agreeable was the necessity of plowing through heavy brush, timber, windfalls, unbelievable masses of poison ivy, stinging nettles and chigger-infested grass, and wading up creek beds to find the falls and their birch trees.

Anyone can visit Fort Falls near the refuge headquarters, but I felt a sense of accomplishment when I finally located Taylor Falls a mile or more to the east. Clinging to the lip over which the water poured were several paper birch trees. Even some area natives are unaware that this fall exists. I sat down to rest, and stare, and contemplate.

The rolling, treeless Sand Hills south of the Niobrara are a giant sponge that holds Nebraska's biggest aquifer. The hills lie on a stratified layer of hard clay, and ground water makes its way along this impervious substratum, welling to the surface as springs from which rivulets meander toward the Niobrara.

As if cut by a giant knife, hills end abruptly at a

wooded wall that plunges downward to the rolling

NOVEMBER 1971

27

Potter Falls, just outside the refuge to the east, is privately owned and closed to the public. It dares to be different from the others by facing south, and so it is the only one that feels the warm sun on its cloak of water. Canoeists, running the Niobrara from the refuge headquarters, frequently terminate their journey at the small but noisy Sears Falls nine miles downstream without ever realizing that the first four exist.

Sears, on the other hand, is out in the open for

all to see. It smashes directly into the river without

NOVEMBER 1971

33

Happily, Smith Falls a few miles downstream, again is birch-crowned. Nebraska's tallest waterfall, it is remote and difficult to find. Its few visitors generally cross the Niobrara on a county cable car and walk up its discharge creek to find it.

The tiny, ecological band that contains most of Nebraska's birches is scarcely a stone's throw in width. It appears to coincide with the outcropping clay layer that is responsible for the falls, wedding each to the other. Moisture and soil conditions combine in delicate balance to support the life of the paper birch. It is a wonder the tree exists within our borders at all, since its home range lies much farther north. One theory is that this scant population along these few miles of the Niobrara Valley was left after withdrawal of the last glacier during ages long gone, but no one really knows.

Whatever the reason, they seem strangely out

of place. Caught in the crush of elm, cedar, and Cottonwood; oak and hornbeam, the white birch trunks

glow ghost-like in the canyon's gloom. Few achieve

the stately splendor associated with their kind in

other areas where uncrowded conditions permit full

growth, but nonetheless, they diffuse their gentle

beauty into nondescript timber around them. They

acle folk

NOVEMBER 1971

37

In the primordial dampness surrounding a fallen tree, its strength is sapped by beetle and fungus, carpenter ant and rot. Its interior disintegrates rapidly under the stress, but the iron-willed bark, stubborn to the end, retains the shape of the mother log for a dozen years or more until the sharp hoof of a passing deer or another falling log smashes it into the duff.

Perhaps its very name —paper birch—tempts man to leave a message. The outer bark, when heavily scratched with a nail or knife, relays the inscription to the cambium layer, which repeats the original message year after year. Though the original injury has long since sloughed away, one particularly venerable birch at the base of Cork- screw Falls still mimeographs:

Paul Har__(the last letters too blurred to read)Norfolk, Nebraska

Dec. 30, 1930.

There are, without doubt, more falls in other hidden spots along the Niobrara. They, too, may boast their birch-tree guardians. The combination adds up to a display of rare beauty and a challenge to seek them out. THE END

50 years on the line

With over a half century trapping behind him, Jack Kraus is a book of outdoor knowledge

RUGGED TRAPPERS, wise in the ways of nature and wild creatures, and toughened by years of deprivation and danger, were among the first white men to move into Nebraska's expanses.

Pursuing oft-wary fur bearers was not for the weak in body or spirit. Obtaining prime hides meant trapping in the coldest time of the year, usually working in ice-crusted water, then having the animal freeze solid even before the skinning knife could be brought into play.

In many respects, things have changed little. Trapping is still a cold-weather proposition, although ruber waders help a bit when sloshing around in a frigid stream. It still takes a pretty rugged individual to take part in this sort of venture and enjoy it.

Such a man is W. E. (Jack) Kraus of Taylor, a small town in central Nebraska. He knows what is involved in the trapping business because he has been in it every winter for more than 50 years. At age 76 he can still make a younger man pant and sweat trying to keep up with him, and he ends up each season with an impressive collection of hides nailed to his wall.

Actually, Jack doesn't nail up hides. He either skins his carcasses neatly and puts the pelts on stretching frames, or sells whole "critters" to fur buyers. He carefully brushes the ones he stretches to a bright sheen, and normally sells only frozen animals "as is".

A resident of Loup County since his father homesteaded a few miles north of Taylor when he was barely in his teens, Jack has carried on his operations during the past half century. The North Loup and Calamus rivers are his stomping grounds, and he concentrates most of his efforts on an area where the streams cross two large ranches several miles north of Taylor.

Much of his trapping is done in February, long after the rivers are completely covered with ice.

"I've fallen into the river, even through the ice, but never had anything like a close call — at least not yet," he claims. "Of course, I don't work quite as hard at trapping now. There was a time, though, when I did it because I needed the money. Now it gives me something to do. I can't stand just sitting around the house. I have to be up and doing things."

Perhaps an understanding and tolerant wife has something to do with his long career. Last year, in fact, she accompanied him for the first time on his regular 6 a.m. trap-tending tour.

"It really helps having her along to drive the car. That way I can do everything in one trip, rather than having to walk back and forth between the car and the river."

Officially retired for the past 11 years, Jack is far from that. For more than 20 years he worked at Taylor Dam as superintendent. Earlier, he farmed and ranched in the area, and for several years was active in rodeo competition.

"I can still ride a horse as well as ever," he says with pride, and still works on a local ranch during summers when he can squeeze it in between fishing excursions.

"I used to hunt a lot, too, but gave it up several years ago when I lost the vision in my right eye because of a flying metal splinter from a post I was pounding into the ground."

Jack doesn't act his age, nor does he look it. Most people would guess him to be at least 10 or 15 years younger than he really is. When trying to keep up with him in heavy tangles of brush along the river, they would probably lop off another 20-odd years.

Life for him has been a constant learning process. His knowledge of the ways of his quarry enables this trapper to place equipment in just the right spots to 42 NEBRASKAland catch the critters. This is true whether the water is open or frozen over.

When Jack is asked about the hardest part of trapping, he doesn't mention the rigors of winter or the setting of traps. "It's the skinning," he explains bluntly. "It takes me about an hour to skin out a beaver. Mink and muskrat are easy, but beaver make up for them."

He explains that beavers are large — usually weighing between 50 and 60 pounds and often up to 80. The hides are taken off after making only one incision down the middle of the belly. Then the legs are cased out— "sort of like taking a large dill pickle out of a jar."

When the beaver carcass is frozen, skinning is pretty uncomfortable work. The same is true of coyotes, which Jack traps occasionally, or shoots if he encounters them while running his traps. He often sells coyote carcasses unskinned.

Because beaver pelts are worth much more than others and because the animals are bigger and more difficult to trap, the challenge is greater.

"I remember the time I caught one without the use of a trap—that was a funny thing. There was this beaver house in the river and every time I went by I jumped on top of it just to see the beavers scoot out from underneath. Well, the weather turned real cold and the water must have frozen underneath the beaver house, although I didn't know it at the time. The next morning I jumped onto the house as usual, but didn't see anything come out.

"No sound came from the house, and I assumed it was empty. I stepped off, stopping to light a cigarette, and while I stood there, I heard this commotion inside.

"The top wasn't very thick—just a few sticks and not much mud. I went to the car for a small crow bar, came back, and poked around until I could see inside.

There, busily digging at the ice below them, were two beavers. As they scurried around, one of them stuck his tail up near the opening, so I grabbed it.

"I really didn't know what to do with him, but hung on. He wasn't very big, probably 40 pounds or so, but ne sure was a handful. I kept pressure on him, meanwhile enlarging the hole with the bar. I knew that if I pulled him out of the hole he might bite my leg. After several more minutes I worked nim all the way out and rapped him on the head with the bar.

"Things had worked out well, so I thought I might as well try for the other, but just as I peered into the house to see what he was doing, he broke through the ice and disappeared into the water below."

Not all Jack's experiences are so exciting. Most of the time it's a routine case of heading out into the country early each morning to check his 16 beaver traps and 50 smaller rigs, and resetting them if necessary. The beaver traps are No. 4's with double springs. His small traps are No. lVfe.

"I never bait any of my sets. Some fellows do, but they don't have very good luck. I have rigged traps around a carcass pn occasion to catch a coyote that might come to feed on it, but that's all. The best way is to set the trap where the animal will step into it.

"Once in a while you'll catch something you don't expect, but it doesn't happen often. One time I caught a mallard drake in a beaver trap. It was in shallow water, and the duck must have seen the trip plate and thought it was something to eat. He put his head right in, and the trap caught him by the neck. Other birds sometimes trigger the smaller traps, or, 'possums get into them. They are not worth much, though, so I don't like them."

Beaver are Jack's main concern. He has averaged more than 10 a year during the past 5 decades. Halfway through last season he sold 16 (Continued on page 57)

The Hunter is a Tourist

From across the nation they come to pump life into state's economy

THEY COME FROM Missouri, Oklahoma, Colorado New York, or Alaska. In fact, they hail from almost all 50 states, even a foreign country or two. "They" are a particular breed of tourists known as nonresident hunters.

Every year they stream to Nebraska in cars, buses, trains, and planes to participate in the great adventure of hunting the "Nation's Mixed-Bag Capital". While in pursuit of wily ringneck, tricky bobwhite, or crafty whitetail, they color the countryside green, dropping bonus dollars into the local economy. Usually sportsmen of the highest caliber, they often make lasting friendships with their resident hosts.

Their demands are fewer than those of the average tourist and they stay longer than ordinary out-of-state travelers. A survey, conducted by the Game and Parks Commission a few years ago, showed that visiting hunters averaged three to four days per trip, and many returned during the season. Still others prolonged their stays to a week or 10 days. Sometimes they brought Mom and the kids to enjoy a late vacation here "where the West begins". And, sometimes, the whole family trekked afield to enjoy a hunt in Nebraska's great outdoors.

While his opinion may or may not be typical of those across the state, Jack Vaughn, manager of the Holdrege Chamber of Commerce, has nothing but high praise for the nonresident gunners who flock to that area each year.

"They spend more money than the average tourist. They are not stingy in any way," Vaughn stresses.

"They seem to have no concern about money. They always order the biggest steaks...the best of everything. But, what's more important, they are gentlemen. Farmers like them, and they, in turn, praise our farmers to the skies."

As in many other communities throughout Nebraska, lodging facilities in the Holdrege area fill up during opening weekend and business stays brisk throughout the season. Folks there believe in catering to their special guests. At nearby Wilcox, the Lions Club sponsors its "Howdy, Hunters" program. The Lions have done some legwork and lined up more than 25,000 acres of land for each gunner who purchases a 44 NEBRASKAland

Another Lions Club in the same area operates in a similar fashion. Last year, the Huntley Lions included some 35,000 acres in their program. They, too, opened the ringneck season with a big hunters' breakfast. At Funk, still another Lions Club used the opportunity to throw an opening-day breakfast to raise funds for one of its charitable projects. All across the state, Nebraskans are becoming more and more aware of the economic impact of the free-spending, visiting hunter. They are going out of their way to make the gunner welcome. It makes good sense, for the sportsman who is treated right will come back again. And, next time, he may well bring some friends. The friends, in turn, will bring others. So it continues. For a small investment of hospitality, the entire community benefits quite richly.

When you consider that American hunters spend in excess of $1.1 billion each year, there's a rich mother lode to be tapped. Even more interesting: only 6.4 percent of that money is spent for permits. It costs the visitor five times as much to hunt upland and small game here ($26) as it costs the resident. Thus, these guests do much to support the conservation programs of the State of Nebraska. In 1970, 19,139 out-of-staters paid $478,475 for the privilege of hunting small game in Nebraska. Big-game hunters added another $43,800. When you consider that this money can be used to bring in federal funds on a 25-percent-state to 75-percent-federal basis, it means Nebraska's conservation projects benefited to the tune of $913,981, thanks to visiting sportsmen.

Even so, this is a small amount compared with the money spent on other things. The big item is equipment, not necessarily bought at home, accounting for 35.4 percent of hunters' expenditures. Last year, a Holdrege hardware store sold a $125 shotgun to a visiting hunter the day before pheasant season opened. That scene is repeated frequently across the country. While the gunner will not often wait to purchase a firearm, he seldom buys his shells ahead of time, and there is a considerable amount of other paraphernalia left to be purchased at the very last minute.

But, where does the rest of the hunter's dollar go? Well, he lays out 11.2 percent for auxiliary equipment like camping gear or clothing. Another 16.7 percent goes for guides, dogs, and the like. He spends 15 percent on transportation and 12.3 percent on food and lodging. The final three percent applies to "privilege" fees like those for the Wilcox "Howdy, Hunters."

The last "National Survey of Fishing and Hunting," compiled by the Census Bureau with co-operation from the U.S. Department of the Interior, indicates that some 18 million Americans over the age of 12 go hunting every year. Many of them travel great distances to pursue their sport, averaging 637V2 miles each per year. And, hunters spend not only money, but time, too. They average 14 days a year in pursuit of their quarry. Nationally, that's 185,819,000 recreation days a year.

What it all boils down to is that there is a ready-made market especially suited to agricultural areas where game is readily available. Farmers can supplement their income by providing meals, lodging, a place to hunt, and plain, old-fashioned hospitality. In addition, guide service is much in demand. To quote Jack Vaughn: "Good guides are worth their weight in gold."

Anyone with time to spare and good knowledge of his home area can pocket extra cash by hiring out. At the same time, all services —restaurants, lodging facilities, service stations, or one of many others — are used by the hunter. When this bonus income is injected into the community through any of these mediums, it benefits the entire locality. And, most hunters are easy to please, for they are used to "roughing it", often preferring it that way.

Whatever his point of origin, the out-of-state hunter brings a boon to his destination. Nebraska has much to offer him with its mixed-bag potential. But, the state's most important asset is hospitality, with the folks at Wilcox, Huntley, Funk, and hundreds of other spots around the state extending a welcome. That combination is hard to beat. It means happy hunters and a windfall for NEBRASKAland. THE END

LIGHT and LIVELY

Weighty problems fade as pair of chums revisits refuge to test tempers of the smail but feisty northern pike

THE HAMMERED, SILVER spoon clapped the mirror-like surface with enough authority to forewarn every northern in Crane Lake. Seemingly it had not. The ultra-light sung methodically, whipping four-pound monofilament line smoothly over the eyelets of the 1/2-ounce rod. The eight-ounce blade was nearly retrieved when the rod doubled and then sprang back, lifeless in Joe Hyland's hands, the line floating snake-like to the surface.

That was not the first, nor would it be the last time that a one- to two-pound northern bowed the rod and snapped the line on Joe's rig. The proverbial "dog days" of late July had set in when Joe and I penetrated the Nebraska Sand Hills.

The whole plan hatched two weeks earlier in Lincoln. I was looking high and low for an ultra-light advocate to use on a story when Joe, an old friend, stopped by to shoot the breeze.

You could call Joe and me old college chums. We were both plugging our way through the wildlife curriculum at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln when we struck up a friendship. Many a weekend in the field was behind us. After cap-and-gown time, both of us were tossed into the job market and have been bouncing around a bit since. Joe was involved in research with the Game and Parks Commission for a while, switched to land (Continued on page 62)

Some men hunt for meat. But several things have made me cherish a hefty rack even more

Obsession for Trophies

FOR CONVENIENCE, big-game hunters have long been separated into two categories — meat hunters and trophy hunters. Certainly, the two groups overlap, as opportunities and interests vary with circumstances. But, there are plenty of reasons for the groupings.

There are those who envision a game animal simply as so many steaks and roasts, and the quicker the animal is on its way to the deep freeze, the higher they rate their hunting skill. An experienced trophy hunter, on the other hand, often tends to pass up many animals in his quest for something better. However, the trophy hunter doesn't condemn the meat hunter, because it means less competition for the really grand bucks which may be just over the hill.

Trophy hunting usually requires considerable time and patience. And, it calls for an intimate knowledge of the game and its habits. When mule deer are the subjects at hand, and Nebraska's northwest reaches are the setting, I am really in my glory. I guess since downing my first deer as a teenager, I have slowly developed into a confirmed trophy hunter and like to talk about it whenever I get the chance.

Although not a native Nebraskan, I have become pretty familiar with the Panhandle since moving here many years ago. And, as the chief inspector of the Nebraska Brand Committee, I have ample opportunity to see the land close up.

Since 1960, I have taken some nice mule bucks, the best to date being a non-typical mule rack in 1960 which measured 25678 points and still holds top spot in the state record book for that category.

Most years since then, I have downed massively racked mulies — all within an area of less than 10 miles. Part of the reason for my success is that the most remote area is avoided by "meat hunters" who claim there is nothing in that area or, at best, only a few does.

So-called meat hunting is natural in the sport of hunting because that has always been a primary reason for pursuing game. And, there is a need for it to maintain stable game populations. If everyone suddenly converted to trophy hunting, the business of game management would become chaotic, and the outlook for the individual trophy hunter would be extremely grim.

Certainly, most big-game hunters have neither the time nor ambition to seek only trophy animals —big-racked bucks which make up only about five percent of the total deer population. Luckily for all concerned, most hunters are happy to have a crack at any antlered critter. Still, it appears Nebraska could support at least a few more prize seekers.

Nebraska hunters do not appreciate the fact that they have a better chance at a trophy than is afforded many residents of other states. I have had experiences and adventures that I feel cannot be equalled anywhere in the Midwest.

I suppose I started on the road to becoming a trophy hunter with the first deer I shot on my father's ranch in South Dakota when I was about 15. It was only a forkhorn, but I was as thrilled with that mule buck as I would have been if I had shot a world record. That started a hunting fire within me which I hope keeps burning at least another 40 years.

I have been deer hunting almost 25 years now, but that hasn't dulled my sense of anticipation nor the thrill of success when afield.

I don't suppose you ever lose that feeling—when your throat kind of tightens and your heart starts pounding. At least I haven't lost it. Perhaps it is partly because trophy hunting is almost an obsession with me, but I don't think you can beat deer as adversaries. They have keen senses, can run up a steep hill faster than you can fall down it, and bucks that have lived through the first season or two get so cagey you wouldn't believe it. Friends of mine have told me they don't hunt deer anymore because it is too easy. That may be true if you are going to shoot the first legal deer you happen across, but it just isn't so when you go after trophies.

Usually, old bucks have seen deer shot—often they have witnessed deer taken right out of their bevy of does. This tends to make them wary, so that they absolutely shun the companionship of other deer as a means of self-preservation. Often, in fact, the real trophy buck seems to have given up the chasing or herding of does and prefers to lead a solitary life. Maybe this is just true during the hunting seasons — after he hears that first firearm go off in the fall.

Just to show you how sneaky those mulies get, I remember one season, I think it was 1957, when I was hunting an area south of Chadron. I had just left the service, so it was my first hunt in several years. I suppose I was a little overanxious, for I shot one of the first legal deer I located. Not paying particular attention to my surroundings, I completed dressing that deer, then memorized the location so I could find it when I came back with help to haul him out. I started to leave, but hadn't gone 50 yards when a huge old mule buck exploded from a small brush pocket. That old buck had obviously remained hidden the entire time involved in my shooting and dressing the other deer, and only appeared when I walked directly toward his hiding place.

It often happens that hunters simply overlook big-racked bucks during even a cautious stalk, because the deer are more devious than anticipated. Hunters moving stealthily through (Continued on page 52)

48 NEBRASKAlandMy office reflects the sport I enjoy most

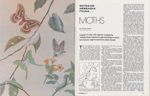

NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA. . . Moths

Largest of order with species numbering 140,000, these insects are ugly ducklings in youth, but become regal monarchs in adult raiment

THE COLLISION was inevitable. The high-speed, ever-narrowing circles of a swirling miller closed in relentlessly on the vulnerable mantles. Suspended from a hook in the center of the livingroom ceiling, the faithful old gaslight was a favorite target of those pesky critters of the fields. All members of the family stared until the suicidal moment occurred. The moth collided with the white-hot mantle

Memories of battles between moths and gaslight mantles are still vivid in areas of Nebraska where rural electrification is a relatively recent blessing.

The colloquial name miller applies to many species of night-flying moths, most of them probably adult forms of well-known and destructive cutworms.

Along with butterflies and skippers, moths are part of the second-largest order of insects in the world. The order Lepidoptera is comprised of 140,000 species.

The name Lepidoptera means "scaly winged" and refers to the fact that the hairs covering the wings are flattened or scale-like. These scales give the wings their color.

While butterflies have club-shaped antennae, moths have feathered or thread-like antennae. A few rare, tropical species of moths —like butterflies—have clubs at the ends of their antennae, but for the most part any knobs, if there are any at all, are below the tips, thus distinguishing the moths from butterflies.

No other insect order claims as many variations in size and color. Moth species range in size from less than a quarter of an inch to the giant 12-inch owlet moth of South America. There is probably no color known to man that cannot be found to some degree on one or more of the moth species. Hues range from the very drab gray of the cutworm moth to the transparent, pastel green of the luna moth.

Moths are experts in the art of mimicry. One species resembles the face of an owl while others take on the appearances of leaves, tree bark, or sticks. The moth most often identified incorrectly is the sphinx. This speedy, darting insect is sometimes called the hummingbird moth. Its habit of darting from one flower to the next in quest of nectar, long snout, and rapid wingbeat make it closely resemble the little hummingbird. Gardeners, fascinated by the evening antics of the sphinx, would not be so tolerant if they realized that this same insect, while in the larval stage, may have been responsible for the loss of a tomato plant or a favorite flower a few weeks earlier.

Before any moth can display the vivid colors of adulthood, it must pass through four distinct, seemingly unrelated, stages. The adult female moth deposits her eggs on a favorite host plant. Those eggs that are not devoured by some hungry, egg-seeking insect, hatch and become larvae. The larvae immediately begin feeding on the host plant. Most larval forms feed voraciously until maturity. Next is the pupal stage. This stage, depending on the species, may take place in the soil, enclosed in a protective cocoon or concealed in a rolled-up dried leaf. The pupal form is a relatively inactive stage. Except for a twitching of the abdominal section when disturbed, the pupa is dormant. Most moth species overwinter in this stage and complete the transition to winged adulthood only when warming spring temperatures trigger the hormonal change, causing the adult to emerge.

The hobby of collecting and studying insects is fascinating. Some very interesting species can be found in 4-H collections displayed at county fairs.

Collecting, however, can entail more than just gathering adult moths. The process of locating, feeding, and studying moth forms through the entire cycle from egg to larva to pupa to adult can be a rewarding experience for the nature student.

The four-inch larval form of the cecropia moth can best be described as beautifully ugly. But, just put one of these large worms in a jar with a few twigs and see what happens. The transitions which take place are miraculous. THE END

TROPHY OBSESSION

(Continued from page 49)good deer habitat always have the feeling they are going to spot a prize buck before it is aware of his presence.

It just doesn't happen that way very often. A shrewd buck hangs around good cover, moves out to feed after dark and returns to cover before light, and rests in places where he can slip into hiding from two directions. And, he stays alert, using his keen nose and ears to evaluate anything suspicious.

I guess the most important factor in hunting a mule deer trophy is not expecting him to react like the average buck. He will hide in very small weed or brush patches, sometimes at great distances from other trees or cover. Even when a hunter approaches, he will remain motionless as long as he feels he has not been spotted, and will allow the hunter to pass within a few yards of him. Many times the buck will even stretch his neck out and put his nose on the ground. He starts out life as a fawn hiding in this manner, and it continues as a protective measure as long as he lives.

When hunting, I never use after-shave lotion nor perfumed soap, and don't wear clothing that smells of mothballs or soap. I always air out my hunting clothes for several days prior to wearing them. Since I don't smoke, that doesn't concern me, but the scent of tobacco is definitely associated with humans, and is strictly taboo in deer woods.

Luck, of course, plays an important part, too. One year I was hunting a particularly rough area of the Pine Ridge, and after stalking at a snail's pace the first part of the morning, I rounded a canyon wall and entered a small clearing surrounded by pine trees. Directly in front of me was a fine buck feeding on brouse. Both of us were surprised, and all I got was a snap shot, which I missed as he tore up 100 yards of terrain, thus making his escape.

I did manage to make a mental note of his unusual antlers, so at least I could relate the story of the big one that got away to the rest of my hunting party. Several hours later, after lunch and more fruitless walking, I returned to the same canyon on my way out. This time I walked on top where the going was easier. After reaching the area hunted earlier, I spotted the same large buck. He was lying in plain sight under a big tree right next to a canyon dropoff. I found a handy limb, propped my rifle on it, and soon had a fine specimen for my den wall. I never would have expected that rascal to be anywhere near that area, and only luck and some measure of laziness on my part put him in my freezer.

Whenever an avid deer hunter starts relating details ofhis hunts, it is natural for him to include details about his favorite rifle, scope, cartridges, and sundry other items. In my case, however, this is rather difficult. I may have one pet rifle, a .264 magnum, but I use many. That is because I am also a gun collector. Not just any guns, but pre-1964 Model 70 Winchesters. To date, I have 61 of these in calibers ranging from .22 hornet to .458 magnum. I have hunted with many of them, fired all but a few which are still factory-fresh, know them all intimately, and have brief histories to tell about them.

Primarily, however, I like to hunt mule deer. My collection of racks adorns much wall space in my office and workshop at home. Each of these, even more than the rifles, represents a special time in my life. I can look at one of the multitined antlers and recall many special hours or days in the field.

One of these I got a few years ago. I had hunted several days without spotting anything impressive, and then the weather turned. In the morning the ground was covered with four inches of fresh snow. A new snow is the most ideal time to hunt mule bucks —they are easier to locate, track, and recover if you only cripple one. Anyway, I was walking along the north edge of a deep, narrow canyon bordered on both sides by pine trees and brush. It was only about an hour after sunrise when I noticed seven does bedded down across the canyon about 100 yards away. As usual when seeing any does, I sat down and glassed the area. After five minutes without

Come for Lunch... FOOTBALL GAME DAYS SATURDAYS: Sept. 11 Sept. 18 Sept. 25 Nov. 6 Oct. 2 Oct. 16 Oct. 30 TEAROOMS, FIFTH FLOOR DOWNTOWN Come for lunch 10:30 to 1:30, when Miller's fine foods will be served buffet style for your convenience... you will eat quickly (and well) and get to the stadium in time for the kick-off! P.S. Stop at the Bake Case on Fifth Floor, take home something good for dinner! 52 NEBRASKAlandseeing anything else, I was deciding to give up and continue on my way when I saw a slight movement farther up the ridge. Careful checking showed I had located one very large mule buck. I wriggled into a prone position and rested my rifle on top of a dirt mound. The buck was bedded down under a small pine tree, apparently watching his potential harem from what he felt was a safe and secure place. That strange feeling of elation, excitement, anticipation, or whatever, had come over me with the first glimpse of the big rack. There comes that moment when you could fire off the shot, but unless the buck acts nervous, you look him over once more. You even try to determine something of his personality from watching him, trying to guess his age and what he is thinking about right then.

But, there comes that time when you can wait no longer —you remember what you came for and know you have found it. I was using a .30/06 with a 4X scope that year. I put the crosshairs on him again and touched off a shot. When the echo died and the stillness of the early morning settled in again, I had one very massive trophy buck, possibly the largest deer I will ever have the opportunity to shoot. And, that opportunity came about as the result of no special skill. Normally, I suppose, memories of a hunt vary according to how difficult or involved the quest was. And, I guess if some amount of skill was required, it means more than if you just happen onto a trophy. But, every hunt is different, and every one brings pleasure as no other kind of hunting can. I almost always get two deer licenses a year and can hardly wait from one season until the next. I guess I am just an incurable deer hunter.

So it is with a lot of people. Their techniques or goals may be different, but the same enthusiasm is there. Perhaps it is difficult for a non-hunter to appreciate, but it is even more difficult for good hunters to understand how other people can miss out on such enjoyment. Having a deer season every year is the only compensation for growing another year older. THE END

Where to go

Bertrand, Rainwater Basin

A WATERY TIME capsule, the Bertrand lay undisturbed for more than a century under layers of silt, sand, and water, storing riches beyond all expectations. Today the steamboat has been unearthed to yield its wealth to those who want to know the river and its past.

The Bertrand embarked from St. Louis on March 18, 1865, bound for Fort Benton on the spring flood waters of the Missouri. On April 1, she ran into a snag and sank without loss of life, but with almost total loss of cargo. Much of that cargo was preserved for decades under a layer of tightly packed blue clay. More than two million artifacts have now been removed from her hull.

The Bertrand rests in the Desoto National Wildlife Refuge, and her cargo is stored in a National Park Service laboratory on the refuge, but selections from that cargo are on display in the laboratory building.

Among the two million items stored at the refuge are luxuries ranging from brandied peaches to French champagne and frontier necessities including broad-brimmed hats and hobnail boots. Perhaps the most intriguing discovery of all is the 780 gallons of Dr. J. Hostetter's Celebrated Stomach Bitters, a potent 32-percent alcohol with some strychnine and belladonna added for effect. A chronicle of frontier life could be written using the many items found in 54 NEBRASKAland the stores of the Bertrand as a basis. A life style was buried in the hold of the vessel for more than a century, waiting to be unearthed as evidence of hardship, and then the sudden luxury of instant wealth at the gold diggings.

The Bertrand's cargo, under the supervision of Capt. James Yores, was scheduled to arrive at Fort Benton in Montana Territory about two months after the sternwheeler's departure from St. Louis in March. Much of the cargo, including quicksilver and general supplies, was to continue overland in wagons to the frontier mining communities of Virginia City, Deer Lodge, and Hellgate. Hence the varied cargo — supplies for pioneers and luxuries for those who had struck it rich and could afford them.