Where the West Begins

Nebraskaland

October 1971 50 cents Antelope by Bow Canoe Capers Bluegull with Flies Nebraska's Navy A potpourri of photos Process you own big game

Speak Up

YOU DON'T SAY-'The subscription-canceling reader from Seattle, Washington (Speak Up, July 1971), quit too soon.

"For a 'fishing-hunting, western Nebraska-oriented magazine', you failed to live up to the billing this month. Only 2 of 11 major stories concerning Nebraska involved hunting or fishing—one on each. 'You offered 16 photos on hunting and fishing and 39 on other subjects. Six of the hunting photos involved bow and arrow use on targets —not on game. 'You had eight fishing photos, with only two showing fish which had been caught. (Oops! Make that three —cover photo.)

"NEBRASKAland is a tremendous publication and one we in Ohio wish we had.

"I'm just sorry the Seattle reader had to miss the boating, packing, prairie doctor, bees and wasps, planthood, canoeing, Ashland Hollow, boat rental, and goldenrod stories in the 'hunting and fishing' magazine."—Don Miller, Outdoor Editor, The Chronicle-Telegram, Elyria, Ohio.

SUPPORT-"After reading Mr. Klataske's article about effects the Mid-State Reclamation Project would have on the Platte River Valley (For The Record, June 1971), I felt I must write.

"My main question is: Why do people directly involved with such projects seem to be totally unaware or even unconcerned with effects such an endeavor would have on the Platte Valley? In almost every case I can think of where the ecology or the pollution of a lake, river, or whatever was being threatened, the people most directly involved with actual construction or planning were the people least concerned with the effects the completed project would have. "It almost always takes outside concern from public or private interests to re-evaluate the actions of such groups. I can only say I hope Mr. Klataske has many supporters in saving the Platte River Valley."-T. D. Hutcheson, Lincoln.

COOKING FOR CARP-"A number of years ago, there was a recipe for doughballs in one of NEBRASKAland's articles. I can't seem to find it now and we would like to go fishing for carp. Could you please help us out?" —Mrs. Johnnie McClain, McLean.

For Mrs. McClain and any other interested readers, here is the recipe as it appeared in the April 1963 issue. Mix one cup white flour, one cup yellow cornmeal, half a cup oatmeal, one-quarter cup grated Parmesan cheese, and one teaspoon sugar while dry. Then add enough cold water to form a stiff dough. Knead until well mixed, then pinch off pieces and form into balls about the size of a small grape. While you are doing all this, be boiling a quartered onion in a saucepan full of water. Remove the onion pieces when done, and discard them. Pour the doughballs into the boiling water, and cook until they rise to the surface—a minute or so. Remove the balls with a spoon and lay them out to cool and harden. These tough pellets will keep for days and may be freshened somewhat by placing a damp rag over them or storing in a tight container.— Editor.

IMMINENT PROBLEM-"I was greatly interested in Mr. Ron Klataske's article on the Platte in Danger (For the Record) in the June 1971 issue of NEBRASKAland. "We in Merrick, Nance, Platte, and Hall counties are faced with a much more imminent problem, however. The Mid-Platte Valley Watershed Board has instituted a clearing program on Prairie Creek which winds through all these counties. The program will remove all the trees from the banks of this stream. The great majority of these trees are large cottonwoods and willows which have stabilized the stream banks for more than 50 years.

"Prairie Creek carried some high water in 1967 and 1968, so the board has decided that clear-cutting the stream will alleviate this situation. This is but one of the many destructive acts carried out against fish, game, and habitat throughout (Continued on page 4)

SPEAK UP

(Continued from page 3)all sections of this country. As so often happens, the people who institute these programs are not even remotely wildlife or conservation oriented. They are administered by smooth-talking professionals who, in half an hour, can convince the average person to burn his house at the next sunrise since Uncle Sam will pay for it. Many landowners have voiced opposition to this project, and many others do not even know what a detrimental act it will be."—George W. Davis, Central City.

THANKS-"I would like to thank the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission for a most enjoyable hunt. The 1970 season was my first venture for deer in the state and it won't be my last. "I filled my permit with a five-point buck and my two companions took one

SELLING NEBRASKAland IS OUR BUSINESS

Cover: Adventurous quartet braves the rapids and falls of Dismal River

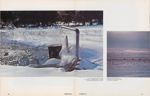

Right: Haigler pond is haven for trumpeter swans. Photo by Greg Beaumont

BULL ON THE LOOSE

FOR WEEKS we had driven our herd of Guernsey cattle from our farmstead near Albion down the dusty road to a vacant farm we rented for grazing. We had no thought of danger until a family friend was gored to death by an enraged bull, and something told me we were headed for trouble again this evening. The trouble came in the shape of a ton of beef roaring angrily over the hill toward the car.

I usually used the old 1928 Dodge while rounding up the cattle and my eight-year-old brother, Kenny, helped out riding his pony. That powerful, old car could crawl along easily in the soft stubble field without getting stuck.

It also made a roaring noise, which perhaps disturbed our Guernsey bull that day and made him mad. After I entered the field, he raised his head, bellowed, and came toward me like a giant avalanche. As he thundered down the hill toward the car, I turned off the auto's ignition switch, rammed the gears into reverse, pulled on the brakes, rolled up the windows, and crouched down flat on the floorboards. He anchored his ugly head in the bumper and rocked the car up and down until I felt as if I was in a roller coaster.

I shuddered as I thought not only of myself, but also of Kenny, who was riding his pony to round up cattle from the opposite end of the field. He was about a quarter of a mile away. All I could think was that if he came back over the hill, the bull might charge, attack, and possibly kill my brother just as he had killed our friend.

Foolishly trying to leave the car, I opened the door on the opposite side from where he was pawing the dirt. But he heard me and came running around. I jumped back into the car, slammed the door, and crouched out of his sight again. If I could just reach the thistle-covered fence, I 8 NEBRASKAland thought, I could roll through, crawl along the fence, reach the top of the hill, and warn Kenny. I tried to get out again, and this time I made it. I peered underneath the car and saw the bull down on his haunches, digging his ugly nose into the ground. I took my chances. I never ran so fast in my life. I crashed through the thistles under the fence and rolled to the other side. Bleeding from scratches, I crawled along the fence toward the top of the hill and out of the bull's sight. He had missed my exit.

I yelled to Kenny to come over. We tied his horse to a post and crouched down in a ravine because there were no buildings or trees to hide behind. We shivered there and prayed we would not be spotted if the monster should come over the hill and race toward the pony.

After what seemed an eternal wait, with grasshoppers jumping all over us, a small snake slithered past and scared away what little courage we had left.

Seeing no one driving down the road to whom we could wave for help, we decided to crawl slowly back up to the top of the hill to see if the herd had headed home. After seemingly endless crawling, we got up off our bleeding knees, peered through the fence, and saw the cattle going through the far gate, the bull now following the herd some distance behind. We went to the pony, turned him loose, and walked to the car, which looked as if a tornado had picked it up, then dropped it carelessly in the field. We started the engine and drove home, careful to stay far enough behind so that the angry animal would not attack us again.

Soon the cattle were in the corral, heading for the water tank. We reached the far side of the house, momentarily losing sight of the bull. Rounding the corner we saw him again. He had not wreaked his wrath yet, for his head was wedged between the branches of one of our fine, young evergreen trees, and he was shaking it furiously. He had already ruined two trees and had snapped off a third at the trunk.

Finally he backed off and galloped to the herd, slurped up some water from the tank, and joined the cattle in the shade.

We locked the gate just as Dad came running toward us. He couldn't believe our narrow escape at first, but finally decided that this should never happen again. The bull, consequently, went to market the next day. We all realized that Kenny and I were lucky to be alive. THE END

HOW TO: REPAIR RODS

Don't give up on that damaged old pole. Here's how to put it back into regular service

MANY DISTURBING noises fill our modern mechanized world, but to the fisherman, few sounds are more distressing than those of a car door or trunk lid closing on a fayorite fiberglass rod.

Even careful anglers seem to suffer such a loss sooner or later. Holding the ragged, pathetic-looking broken ends of a good rod stirs all sorts of sensations in the soul. But, not all is necessarily lost. In most instances, there is a relatively simple and quick way to put the old snap back into that rod. Often, there is not even any appreciable loss in action from such repairs, and for the few minutes of time required, it can mean sizable savings and give you a feeling of accomplishment to boot. We are not, of course, recommending that you break a rod just for the enjoyment, but here are a few ideas for the next time such a disaster strikes your tackle collection.

As fractured rods are probably the most common ailment, let's take a look at that problem first. All but the cheapest glass rods are hollow. If the break is several inches from an end, whether top, bottom, or near either ferrule, the answer is easy. Merely fashion a plug to fit snugly inside the smaller half of the break. Ideally, this plug will be of some lightweight spring steel. This is especially important on the upper end where yirtually all the rod action is.

In the event that tempered steel is not readily available, other materials will suffice: wood, a good stout nail, or wire —even tubing. It is also possible to use a short section from another old fishing rod.

Next, trim away some of the stringy material hanging from the fracture. Nail trimmers work nicely for this. Now, join the two ends to see how tightly they come together. If the joint is not too noticeable, mix up a small batch of epoxy. This is available from any hardware, dime store, or lumberyard. Although quality varies with the brand name, most serve pretty well.

With a dab from each tube mixed well, apply liberally to the plug, regardless of what you have decided upon, and poke it into the smaller, broken end. Make sure the inside of the rod and the plug both have a good amount of epoxy to hold them together firmly. Repeat the applications to the larger broken half and the end of the plug, which should still be sticking out about halfway. Make sure the rod eyelets are aligned.

Join the two broken ends on the plug, smear a little more epoxy at the joint, then carefully prop the rod against a workbench corner or other

OCTOBER 1971 11 NEW... She's a

Any way you look at it—she's a

real Bair Cat—the reloader made

with the occasional shooter in

mind, yet the new Bair Cat will

do the job for the target shooter

as well.

It reloads a shell in 12 seconds.

MANUFACTURERS OF A

COMPLETE LINE OF

RELOADING TOOLS FOR

RIFLE, PISTOL AND

SHOTSHELLS.

BAIR COMPANY

4555 North 48th Street Lincoln, NE 68504

TAKE A

STATE PARK

VACATION

FORT ROBINSON

PONCA

CHADRON

NIOBRARA

Send for complete details

from NEBRASKAland,

State Capitol, Lincoln,

Nebraska 68509

NEW... She's a

Any way you look at it—she's a

real Bair Cat—the reloader made

with the occasional shooter in

mind, yet the new Bair Cat will

do the job for the target shooter

as well.

It reloads a shell in 12 seconds.

MANUFACTURERS OF A

COMPLETE LINE OF

RELOADING TOOLS FOR

RIFLE, PISTOL AND

SHOTSHELLS.

BAIR COMPANY

4555 North 48th Street Lincoln, NE 68504

TAKE A

STATE PARK

VACATION

FORT ROBINSON

PONCA

CHADRON

NIOBRARA

Send for complete details

from NEBRASKAland,

State Capitol, Lincoln,

Nebraska 68509

place so that it can harden without kinking the repaired joint. You want it to be as straight as it was before the break. Usually, by twirling the rod, you can detect any cant, and this can be corrected for some time after the glue is applied.

When completely hard-usually within 24 hours or so-the rod will be almost as good as new, and there should be hardly any change in feel or flexibility. The heavier the rod, the less noticeable the repair.

If just the very last inch or two of the rod is broken off, it will probably be best to just affix a new tip, as the slight shortening of the rod will not hurt anything. Ferrule cement, epoxy, or almost any good waterproof glue will do the job.

Broken eyelets are a little more tedious to fix, but not necessarily tough. Most are fastened with silk 12 windings, and if one breaks off or is badly grooved it can be replaced. Or, the entire set can be replaced by carefully cutting off the old windings, aligning the new eyelet, and rewinding the mountings to the rod. After winding on the new thread, it is best to apply epoxy over the threads to keep them from unraveling.

Even a handle which snaps off can be replaced in most cases. Some supply houses carry differently styled handles into which the base of your rod can be inserted and glued.

So, even though you have already replaced a broken rod, dig the old one out of the basement and take another look at it. You may decide a little work and spare parts can put that old friend right back into working status, and there is no friend like an old friend. THE END

A Dismal Trip

Our leisurely canoe voyage becomes a survival test when rushing stream leads to rapids, waterfalls, and maze of fallen, river-blocking trees

SOMEHOW, WE appeared to have let our enthusiasm get the upper hand over good sense, and this was the result: our 17-foot aluminum canoe teetered on the brink of a 7-foot waterfall, stopped from sliding over only because our load grounded us on the lip.

Bob Grier, the man in the bow, was sus- pended over the raging pool below the falls. Allowing a few seconds for the predicament to register in his mind, he turned around slowly and said, half seriously and half in jest, "Don't get out!"

What transpired during the next few minutes was too ridiculous for even an old Max Sennett comedy. The situation was funny, despite the almost certain cold dunking we were about to get. Several hundred yards behind us, 14 NEBRASKAland

No water was coming over the sides of our craft, so we began to think that maybe we could still get out without going over. Within a few minutes, the second canoe came around a bend in the river. Despite my laughter, Dennis Laudenklos and Rick Bernum could see that something was amiss.

Quickly paddling across the strong current, they beached their canoe and came running to the scene of our fiasco. While Rick held the back of our canoe, Bob extricated his wicker basket of camera gear and clambored back across our cargo to safety. Then, while I got out and started to pull the craft back, Rick sat his six-foot, four-inch frame on the brink of the falls, ready to leap down to see how deep it was. That was a mistake.

As soon as he diverted the water it came over the side, swamping our canoe and dropping the whole works over the edge.

I guess I stood there numbly while Rick, Dennis, and Bob ran around the falls and down to the pool to salvage our gear. Much of the duffle floated and some was still jammed under the seats and struts. But other gear went down.

Almost half an hour later we gave up probing the deep hole —at least 10 feet of roiling, cold water. Rick dived several times to look for our gas stove, my new ultra-light fishing rod and reel, and everything else we were missing and, 16 NEBRASKAland

Going over the waterfall and scooping up the trout were two of many unexpected experiences during our journey. It all started at the Weeping Water bridge on the north fork of the Dismal River in central Nebraska. Dennis and Rick, both in the communicable disease section of the state health department, had planned the trip for several months. When a mutual friend mentioned their intentions, NEBRASKAland Magazine thought it sounded like a colorful trip. As it turned out, it became more of a survival test.

I got the story assignment, with Bob named as photographer. A few phone calls resulted in an invitation to accompany them on their venture, and we headed out from Lincoln bright and early Monday, July 5.

My somewhat faulty memory conjured visions of the Dismal as a tranquil stream, flowing gently through grassy pastures. But, a river would never get a name like Dismal if that were the case! My memory will not fail me again.

Late Monday afternoon we unloaded the

canoes and set out. Lo and behold, the river

OCTOBER 1971 17

Bob and I had brought a tent, but Dennis and Rick were simply bagging it in the open. They had brought dried, packaged trail food while Bob and I struggled under about 50 pounds of cans and bags. Our larder included lots of cookies and peanuts.

A truly pastoral scene surrounded us. Bob and Rick splashed in the river while I floated a trout fly into fishy looking spots. We filled water bags from a cold spring just 50 yards from camp. Later, as the sky grew dark and our eyes heavy, we turned in, listening to the raucous barking of the strangest coyote we had ever heard.

It was about 9 a.m. the next day before we got the dishes washed after a breakfast of scrambled eggs and bacon chunks, instant orange drink, and other goodies. The day held in store our most grueling section of the river.

Within an hour, we traveled from pasture country into canyons that changed the entire nature of the trip. Evergreen trees grew in profusion everywhere on the walls of the canyon, and they were very pretty. But, they were also very troublesome, as we soon discovered. It seems that every dead tree had fallen smack across the river.

During the next 12 hours we hacked and sawed tree limbs and got cut, clawed, and scraped in return. Our clothes were torn, our skin was torn, and our own limbs ached. But we struggled along, inching our way down the twisting, cold course of the river.

Then a relatively clear stretch opened before us. A few hundred yards farther the trees started again. Just as we entered another canyon, we noticed a cow on the bank a few feet from the water s (Continued on page 55)

18 NEBRASKAland

The Select Few

Only fraction of prong horn bow permits issued last year were filled. Those scoring archers form an elite corps

TO TAKE UP a pair of sticks in pursuit of an animal with vision eight times more powerful than man's, and to challenge this animal in its own realm must require the purist of hunters or most foolish of fools. Last fall 14 bowmen proved they held a rightful position in that former group by downing one of Nebraska's fleet pronghorns. They also proved that bow hunting the skittery antelope is a contest of man against animal reduced to its most basic level. It is a pursuit requiring discipline and acceptance of disappointments.

Last year Nebraska hosted almost 50,000 resident and nonresident big-game hunters. Of 1,761 antelope permits issued, only 104 went to archers and only 13 percent of those scored. Since the pronghorn-archery season was first initiated in Nebraska in 1964 only 425 permits have been requested and issued. Demand for bow-pronghorn licenses has been so low to date that no measures are considered to limit harvest by that form. During those 7 years 71 antelope have been checked in to yield an overall success ratio of 17 percent. This average, though similar to deer-archery success, is much lower than that of rifle-antelope hunters, which runs in the neighborhood of 70 to 90 percent most years.

What would motivate a normal man to lay down his rifle, pick up the bow, and pit his wits against an animal nature (Continued on page 61)

Though her gangway once held wartime sailors, Hazard has borne peacetime transformation well

Berth of a Minesweeper

22 NEBRASKAlandNamed for missions past, Hazard now is flagship in Nebraska's navy, monument to passing of brave men

HE MISSOURI RIVER looks deserted north of the Mormon Bridge and it's quiet there. Muddy water silently pushes south with only an occasional, soft splash against miniature promontories that try, without success, to stop the flow. The river's banks are carpeted with vegetation drooping over the edges as if to syphon moisture from the passing current.

But, the scene is almost too tranquil. Driving north from the bridge along the tree-lined lane on the Nebraska side of the river, you know there is a memory of war in these parts because you've seen it advertised. You drive through Omaha's 455-acre Dodge Park and there she is, the USS Hazard, a retired U.S. Navy minesweeper.

She looks out of place. The Hazard was built for naval warfare on the high seas, not as a tourist attraction on a river deep inside a continent. But, incongruous as it may seem, there she is, as seaworthy as ever and armed to the hilt.

During the close of the Second World War she penetrated enemy waters to sweep them clean of hidden mines, thus clearing the way for invasion. Those were hazardous missions, and she lived up to her name.

Today she lies in her berth as Nebraska's latest tourist attraction. Old she may be, but spent she is not. Evidence of this lies in the fact that two Latin-American countries submitted bids to purchase her.

Some Omaha businessmen, however, outbid them. It started as a joke to put a real ship into Nebraska's mythical navy, and then it became serious. Knowing the City of Omaha planned to build a World War II memorial park, a group of clever men approached those in charge and offered to buy the Hazard if the city would find room for her. There was almost instant agreement, so they put in their bid. Lo and behold, they got her. Purchased at Orange, Texas last fall, she was brought up the Missouri early this year. Her decks were cleared for the public June 30. Tourists numbering in the thousands have streamed through since then, an indication that the venture will prove successful.

The Hazard was purchased by the following eight Omaha owners: President Rodney Briggs, (Continued on page 54)

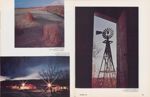

Photo Potpourri

From NEBRASKAland files come a few color pictures gathered over many years. Although of excellent quality, they served no purpose - until now

TIME WAS WHEN many Nebraskans, when quizzed about their state, fell back on the old saw: "There's just nothing to see or do." And for those who would rather not look for "something to see or do", that analysis may have been correct. But, in March of 1964, NEBRASKAland Magazine began making the state's assets harder to ignore. That year, the publication's center 10 pages were brought to life with generous use of full-color reproduction. Since then, multi-hued photographs have spread throughout the magazine, and in the process more pictures have been taken than we have had space or opportunity to use. These are relegated to what is undoubtedly the most extensive catalog of Nebraska photographs anywhere in the world.

While on assignment to illustrate a given story, NEBRASKAland photographers do not confine themselves strictly to the article at hand. Instead, they keep an eye out for photo subjects which, though they fit no particular format at the time, may be used in the future. Unfortunately, there are few spots where random photographs are applicable. Therefore, we thought it might be interesting to show our readers some of the photographs we have, but never used.

These photographs are just a small segment of those remaining in our files. They do, however, represent an excellence which cannot be ignored, and with publication we present a new aspect of Nebraska life and land that residents and visitors alike might otherwise overlook.

24 NEBRASKAland

They fasten red wool around a hook and fix to the wool two feathers that grow under a cock's wattles, and which in color are like wax. The rod they use is six feet long and the line of the same length. Then the angler lets fall his lure. The fish, attracted by its color and excited, draws close and... forthwith opens its mouth, but is caught by the hook, and bitter indeed is the feast it enjoys, inasmuch as it is captured. DE ANIMALIUM NATURA

Long Sticks and Big Blues

THOUGH FLY FISHING was first documented with that description more than 1,700 years ago, and while tackle and techniques have advanced significantly since then, the standards of excellence peculiar to the fly angler - purist in his field - have changed little. The ultimate end is irrelevant; only the method of running the course is of consequence. The fly angler shows a curiosity about and a respect for the delicate equilibrium of lake or stream. He is attuned to other performers that cross the natural stage of the same play in which he has but a minor role. He is aware of the lake's peripheral life, its inhabitants and their life styles, as well as the aesthetics of the moment —the fragile mosaic of rain on calm water (Continued on page 59)

38 NEBRASKAland

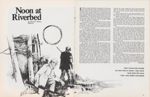

Noon at Riverbed

IT WAS A brisk November morning, the fourth day of the 1969 rifle-deer season. My father-in-law, Walt Weiss, and I were out early as we trekked to the run and the stands we had occupied with no success for the last three days. Earlier in the year, we had applied for and received buddy permits, which assured us we could hunt together. A large section of Walt's farm, just west of Plattsmouth, is covered by timber and all signs indicated it was a deer haven. By the fourth day, though, we doubted if there were deer, and we couldn't decide whether we should try elsewhere.

It was 6:30 a.m. as I climbed into the tree, telling myself that if I washed out I would try west of Louisville later on. As I cradled my .270, I twisted to keep my face out of the wind, a position which put my back to the run. At 6:45, the sun was still below the horizon, but shooting was legal.

I was scanning the area when I heard a noise behind me. I eased my head around. I could make out a dark object in the iridescent morning light as I slid into position with my face toward the form. By then, I could tell the shape was a deer, but, because it was still quite dark, I wasn't sure whether it was a buck or a doe. With head down, the deer ambled across the stubble of a bean field toward the timber and safety. The animal stopped short of the trees, however, standing in front of tall brome. Finally, the head came up and I could make out a rack. A buck!

My hands were sweating, despite the chill, as I crosshaired the vital area through my 4X scope. What happened next isn't clear. But, as I squeezed the trigger, the buck bolted and I remember his hind legs kicking straight out as the .270 roared. I scrambled out of the tree to confirm an uncertain hit, but as I approached the spot where the deer had stood, the only signs were hoofprints - no blood. Disappointed, I paralleled the woods from where my target broke into the timber, determined to check thoroughly for any sign of blood indicating a hit. Some sixth sense told me to cut into the timber. Somewhat grudgingly, I walked a thousand yards and there, right in front of me, was the sign of a wounded deer —fresh blood. The trail was easy to follow until I got to a dry creek bed, a mile into the woods. That's where I lost the trail completely. I hurried back to get my father-in-law and together we retraced my steps, losing the trail in the same spot again. It was about 9 o'clock and we decided to head for home, do the chores, return, and try to pick up the trail once again.

Arriving at the farm, we found my brother-in-law, Bill Weiss of Bellevue, waiting. By 9:45 all three of us were back in the creek bed.

Where the blood ended, we made a large sweep of the area, trying to find the trail. About 5,000 feet out and heading deeper into the timber. Bill sighted more blood. My deer had lain down twice, large pools of blood marking both spots. For the next two miles, the trail was fairly easy to follow, but the wily buck was trying to throw us off by crossing back and forth on his path.

Within another three miles, the trail became fainter, probably because of the animal's closing wound and a light drizzle which had begun. Breaking out of the timber, we traced his path along the railroad bed and, as we approached the Platte River, Bill spotted him, barely running, stumbling now and then from loss of blood. I snapped off a shot, but the bullet was too late. Would he try to swim the river? His tracks led off into a small timber stand between the railroad tracks and the river. He was in a small enough area now to insure our finding him. It would be a relief to complete our job.

I took one step into the woods and suddenly, five feet away, the buck reared out of the tall grass and bolted into the trees. I was so startled I didn't even shoot. After that I lost him three times. Each time I angled back to the riverbed and started again. And each time, I was stymied. Disappointed at tracking the buck that far only to lose him, I had nearly given up when I saw him standing behind some brush. A quick snap shot put an end to the unfortunate episode as the sun nudged noon.

We were relieved that the buck was finally out of its misery. Perhaps it was unavoidable, but I'll never be sure. Now I double check all my equipment and must be certain I can make a clean kill before pulling the trigger. The incident did prove one thing though — never assume you missed until checking the area carefully and once you know the deer is hit, don't give up that trail until you find him. THE END

Had I known the trouble my shot was to cause, I may never have fired. But once I did, I was totally committed

Nicomi

John Gale was used to challenge. But when orders came to abandon Fort Atkinson, he was up against a formidable foe - the girl he loved

PETER SARPY GAVE warning: Til be damned if you think you are smart enough to get that child awav from Nicomi." He urged Surgeon John Gale to forget it, but Gale was determined to try. They sat and talked in the back room of Sarpy's trading post at Bellevue, less than 25 miles south of Fort Atkinson.

Nicomi, daughter of Iowa Chief Wachin Washa, had responded to Gale's overtures four years ago and had become his mistress. A year ago she had given birth to their daughter Mary. Now it was June 1827 and orders had just arrived that Fort Atkinson was to be abandoned.

Gale didn't know what to do. A colorful character, he was one of the adventurous doctors who had left behind prospects of a comfortable private practice for the rugged challenge of military medical work on the frontier. No bond of love tied Gale to any white person, and his only responsibilities were those associated with his position as the fort's doctor. He had been there 4 years now, one of approximately 500 people getting ready to leave. He cared nothing for convention and embraced no cause. He was not, however, entirely immune to Cupid's touch. Nicomi was good to him, carrying herself with regal-like dignity and possessing an inner OCTOBER 1971 strength he never quite understood but always admired.

And, he loved his little daughter. But now his affair with Nicomi would end. Torn between parental love for his child and military discipline demanding that he obey the abandonment order, he confided in Sarpy.

"It gives my heartstrings a bit of a wrench to leave Nicomi behind, but to take her is out of the question," he said. "Mary, however, I can educate. She is bright enough to profit from it. I believe I shall try to get her away quietly and take her with me."

Sarpy warned him again: "You have lived here long enough to know better. No white man can take what an Indian chooses to keep, and Nicomi wants the child."

"Well, I'll try it anyway," Gale said.

What he failed to take into consideration was Nicomi's inherent cunning. She knew the garrison would leave shortly, and suspected Gale's plan to take the child because of the way he avoided her eyes and looked at their offspring. She loved Gale, but the threatening loss roused her maternal instincts. That week Gale packed his belongings, assuring Nicomi he would return. But she knew better. When departure day came, (Continued on page 64)

Process your own Big Game

From field to freezer, do-it-yourself deer dressing is a gratifying money-saver

Field Dressing

BECAUSE OF regulations imposed on commercial meat processors, Nebraska packing plants can no longer process wild game alongside domestic meat. The nimrod who connects with his target may be faced with the chore of skinning and butchering it himself. Let us see if we can simplify the procedure enough to enable you to put high-grade meat on the table.

A good hunting knife is the only equipment you really need for the job, although a small pack saw (or hand axe) is useful to cut the heavier bones. Carry a ball of heavy cord, 25 feet of quarter-inch nylon rope, a jersey knit cover for the carcass, and a porous cloth bag for the heart and liver. These last three items are available as a kit in some sporting-goods stores.

Approach any newly shot big-game animal with caution. You can be severely mauled by a fallen target that suddenly lashes out with sharp hooves when you attempt to cut its throat. Stand well back and prod the body with a stick or your rifle barrel. If no reaction occurs, separate the tag from your permit and tie it to the carcass.

Tie one end of the nylon rope to the base of an antler, and throw a half-hitch around the victim's nose. Four or five feet out, tie a stick into the rope, and drag your quarry to a spot where you can field dress and skin it.

In case you have not already cut the animal's throat, do it now to drain as much blood as possible from the carcass. Spread the kill's rear legs wide by wedging a stick in the tendons above the knees. Run your knife through the hide between the tendon and the leg bone to help hold the stick in place.

Most hunters recommend cutting away the musk glands on the legs and tossing them a safe distance away. Some say you should include the scrotum, too. Clean the knife well after doing this, as any musk on the blade will contaminate a lot of meat.

Cut around the anal opening, pull out a portion of the gut, and tie it off with a piece of cord. Cut through the belly skin behind the breastbone, being careful to go no deeper than the membranes just under the skin. Insert two fingers into the opening, get your knuckles inside the body, and use them as guides for the knife while you rip the belly open toward the rear of the carcass. Intestines and paunch will roll out as the cut lengthens.

Split the breastbone open and cut through the dividing diaphragm between the front and rear body cavities.

Split the aitchbone, preferably with a small saw, and pull the large

Many hunters leave the hide on the venison until after the aging period as it helps keep the meat from drying out. However, it is somewhat easier to remove the skin while the meat still retains some body heat. Throw the drag rope tied around the antlers over a convenient limb and elevate the carcass to a good working height. With the same knife you used for the field dressing, cut through the knee joint of each foreleg, sever the lower section, and toss it away. Split the skin on the inside of the upper legs from the severed joint to the body cavity, then split the neck skin from the breastbone up to the throat, and girdle the skin all around the neck.

Grasp the skin at the back of the neck and work it downward. You will have to pull hard to get it to peel. Use the knife at points where it doesn't loosen.

When the skin is free of the body to the hips, cut off the lower section of the hind legs, and split the skin inside the ham so the hide can be pulled down over the buttocks and off the body.

Pull the protective jersey cloth over the skinned-out meat to keep flies and dirt away. Several layers of good cheesecloth or an old bedsheet are good substitutes for jersey cloth.

If you've been careful to cut no holes, you'll have a good pelt to be made into buckskin. Since you anticipated field skinning your deer, you naturally have several pounds of pickling salt available to spread over the raw side of the hide to prevent spoilage before you fold it into a bundle and tie it up.

Now take your venison to the nearest Game and Parks Commission checking station. Remember this must be done with the carcass intact and the head still attached.

At home, hang the meat to age, preferably in a locker with a controlled temperature of 34 to 36 degrees. Three to four days is right for young animals, five to seven days for older ones. At the end of the aging period, prepare to cut and package the meat. (Continued next page)

Do the butchery with either a large hunting knife or a heavy, sharp kitchen knife. There are several ways to divide the carcass, but the following deboning method provides smaller packages for the freezer.

Hang the animal by the head, just as you did to skin it, and remove the front quarters first. Grasp one of the forelegs and push it away from the body to expose the layer of muscle between the leg and the body. Slice through this, and the front quarter will fall back, exposing the leg joint. Slice through the joint, then with a circular cut through the shoulder muscles, remove the front quarter from the body.

Begin removing the hind quarter by making a cut through the belly meat at the top of the quarter, and continue the cut across to the backbone. Find the hip balljoint and disengage it, then continue to cut along the backbone toward the rump. This frees the quarter.

The tenderloins, generally regarded as the best part of the venison, are long, round muscles lying on either side of the backbone. Push your thumb through the membrane between the muscle and the backbone. If the meat has aged properly, you can insert your forefinger in the opening and simply rip the membrane all along the backbone. Work the tenderloin free from the backbone, using the knife sparingly in the stubborn places. Then, starting at the neck, peel the muscle out. It should come away in one long strip.

To remove the neck meat, cut along the top of the neck to the backbone. You'll need considerable knife-work here, working the blade under the meat toward the throat, and cutting downward. Properly done, only a few scraps of meat will adhere to the neckbones.

The quarters are covered with thin, tough membrane which must be removed. Resharpen your knife and skin the film from all four quarters with a cutting, pulling action.

After this step, the upper sections of the hind quarters reveal three distinct muscles which can be partially separated by pulling at them with your hands. Remove the one running along the inside of the leg first. A little cutting and pulling will free it. Slip the knife between the legbone and the second muscle, and work upward toward the balljoint, cutting around it to remove the slab of meat. Work the blade around the bone to free the third muscle. Any meat remaining on the bone can be sliced off for deerburger.

Trim excess membrane and fat off the meat of the rear quarters, then slice the meat into steaks of desired thickness.

Butcher out the front quarter by cutting along the bone near the top of the quarter, then simply cut around the bone, working downward until the big muscle can be cut off. Slice off the skinny muscles for the burger heap.

Roll up the front quarter muscles, tie them securely with string, and you have excellent roasts. The tenderloins, being small in diameter, may be "butterflied" to produce bigger steaks. Trim one end of the strip square. If you want one-inch steaks, chop a two-inch chunk off the tenderloin, then slice down through the center of this, holding the cut just before the pieces separate. Let the two sections fall apart and you have a tenderloin steak twice the size you get from a straight cut.

You have now removed all the really useful meat from the skeleton. Depending upon how careful you were during the butchering, there will be bits of meat left on the skeleton. These can be carefully trimmed away and added to your other scraps, and packaged separately as stew makings or ground into deerburger. The addition of beef tallow or pork will give your burgers an excellent flavor.

Now divide all your venison into meal-size portions and pack them in plastic bags. Suck the air out of each bag and seal it. Wrap it in a double thickness of freezer paper and label the contents with a marking pen.

If your family was so lucky as to fill two or more licenses, you can identify the packages with a No. 1 or No. 2, meaning the packages contain meat from the first or second animal. By doing this it is possible to compare the .taste of one animal with another when the meat is cooked. Such information is useful if the two carcasses were handled differently at the time of the killing. You can select the one that produced the best meat and use the same method the next year.

Get rid of the skeleton and quarterbones at a garbage disposal area, and your butchering is complete. You will probably find that the skinning and butchering of your own deer was not as difficult as you may have imagined, and chances are you'll enjoy the venison more, knowing that you completed the job yourself. THE END

46 NEBRASKAland

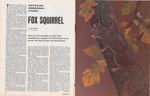

NOTES ON NEBRASKA FAUNA. . .

FOX SQUIRREL

THE MOST COMMON of Nebraska's nimble nut gnawers is the fox squirrel, Sciurus niger rufiventer. The generic name, Sciurus, is the Latin word for squirrel. The specific and subspecific names are also of Latin derivation, niger meaning black and rufiventer meaning reddish belly.

Primary color of the fox squirrel is reddish yellow or orange-yellow with a mixture of gray on the back, sides, and upper parts. Average length is about 25 inches, which includes a bushy tail about 12 inches long. Weights of males and females are similar, averaging about 27 ounces for adults with an exceptional individual occasionally reaching 2 1/2 to 3 pounds.

The only other similar species in Nebraska is the gray squirrel, which is easily distinguished by its gray coloration and smaller size.

With a few exceptions, distribution is limited to the United States, generally east of a line from the western boundary of the Dakotas, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas east of the Panhandle. Distribution in Nebraska includes most areas where suitable habitat is found, which eliminates much of the Sand Hills and Panhandle. Distribution and abundance in Nebraska are generally greater nowT than in the time prior to settlement because of increases in natural timber and in areas planted to trees. However, timber clearing for cropland and grazing has greatly reduced squirrel numbers in some areas.

Tall or mature hardwoods are a prime necessity for fox squirrel habitat. Consequently the best areas are along stream courses or in some of the associated breaks. Although acorns and other nuts are heavily used, the lack of dependability of this food source in many regions makes cornfields, in association with timber, of major importance for good habitat. Fox squirrels are also common in many cities and towns where large nut and shade trees afford food and denning sites.

Suitable den sites are found in old trees after a limb rots and breaks away. Often the rotting wood is removed by woodpeckers or squirrels and a cavity is formed. Entrance holes are usually about 3 inches in diameter, and a cavity with a depth of about 1% to 2 feet and cross section of 6 to 7 inches will provide a favorable area for reproduction, shelter, and escape.

Leaf nests are constructed in tall trees for use as escape cover and also for nurseries. These can be built in one to two days, and will last for six 48 Smart as a fox and agile as a deer, these speedsters are enough to test the prowess of any gunner. Yet, they are often only afterthoughts months or longer if well constructed. They consist of leaves and twigs piled in a tree fork, and will measure about 16 inches across and 12 inches deep. Leaf nests allow increased mobility where suitable den sites are scarce, and have the advantage of being generally freer of fleas and other parasites.

The breeding season, as with gray squirrels, occurs during two primary periods —in January or early February and in June to early July. Young are born after a gestation period of about 45 days in late February or March and in July or August. Litter size ranges from one to six, with an average of three. The young weigh about half an ounce at birth, and eyes open between four to five weeks. At eight weeks of age they are fully furred and capable of being weaned.

Normally, females from the spring litter breed during the following winter, while those from summer litters breed the following summer. Adult females are capable of producing two litters a year.

Plant foods are quite varied, with heavy usage of corn, oak, hickory, black walnut, elm, and mulberry where available. Other fruits and buds are also used. In some places, particularly where there is a shortage of primary foods, debarking of trees is generally common among squirrels. Animal food is eaten, including insects and larvae, bird eggs, and occasional young birds. Bones, antlers, and turtle shells may be gnawed to fill mineral requirements. However, animal matter is a relatively minor portion of the diet.

Since fox squirrels do not hibernate, getting through the winter in good shape necessitates putting on a good layer of fat in the fall and storing food. Nuts and acorns are commonly buried as a source of winter food, being placed in the ground about one to two inches deep, normally one nut in each hole. These caches are later located primarily by scent. Although highly efficient in finding their hidden food supplies, some of this food source stays unused and buried.

During recent years, hunting seasons in Nebraska have run from September 1 through January 31. This allows for major utilization but still provides protection during the primary periods of production. Although there are some avid squirrel hunters, much of the harvest is incidental to the pursuit of other species. In recent years, an average of about 32,000 hunters have taken an annual average harvest of about 192,000 squirrels. Compared to the potential for recreation, few Nebraskans participate in the sport of squirrel hunting. THE END

Where to go

War Bonnet Battle, Artesian Well

AS THE FIRST streaks of daylight began to appear, they took their L places on a conical mound at the foot of an undulation of prairie. At the rear rose a line of bluffs that hid seven veteran companies of the Fifth Cavalry.

Corporal Wilkinson was the first to sight Indians to the southeast at about 4:30 a.m. As he, Lt. Charles King, and "Buffalo Bill" Cody watched, the Indians advanced boldly to the west without suspecting the presence of the Fifth.

King notified Col. Merritt of the Indians' advance through a signalman, and the colonel, with several officers, joined Cody, King, and Wilkinson at the hidden overlook as the cavalry wagons appeared on the western horizon. This was the setting for the War Bonnet Battle, when William F. Cody (Buffalo Bill) is reputed to have taken the "first scalp for Custer".

The site of the battlefield remains almost unchanged since that day almost 100 years ago. Stone markers point out the little lookout point and the scene of the infamous scalping. The terrain is the same, with War Bonnet Creek running to the west of the battlefield, and the line of bluffs rising above it. The hillock overlooks a dry wash where the skirmish took place.

The War Bonnet Battle was part of the action surrounding the battles of the Little Big Horn and Rosebud. As Gen. George Crook marched toward Rosebud, OCTOBER 1971 Buffalo Bill was asked to join the Army at Cheyenne, Wyoming. There he joined the Fifth Cavalry under Lt.-Col. Carr. With Bill as chief scout, they marched out to keep Indian reinforcements from reaching Sitting Bull. When Carr began his march, he didn't know that Crook had already been driven back by the fighting Sioux.

As the Fifth tracked the escaping Indians, Carr was recalled and replaced by Col. Merritt who had orders to join Crook. But Carr's orders also stood. Then Merritt received word that 800 Cheyennes were leaving the Red Cloud agency to join Sitting Bull. Merritt planned an ambush, disregarding the conflict of orders.

Meanwhile word had reached them: "Custer and five troops, Seventh Cavalry, killed."

Merritt moved to intercept the enemy at War Bonnet Creek. There, with his men poised for the attack, Merritt awaited the Cheyennes. To the west, unknown to the colonel, his supply wagons had traveled all night to nearly catch up with him. When the Indians approached from the southeast, the wagons came up from the west. The Cheyennes were obviously watching the wagons, apparently oblivious to the presence of the Fifth.

As the two parties closed in on each other, seven braves advanced down the ravine, intent on cutting off two couriers who had broken off ahead of the wagon train. As the Indians rode in on the couriers, they passed under the lookout point.

Cody led a party against the braves. Some shots were exchanged; then King saw the main body of the Indians rush down the ravine and appear by scores all along the ridge. Merritt called up Company K, King's Company. King caught his mount to join his company, and onty a moment later charged with them past Buffalo Bill, who was standing over the body of an Indian, waving the war bonnet and shouting: "First scalp for Custer!"

As Company K topped the ridge, the Indians fired a scattered volley. When they saw a troop under Robert H. Montgomery about 60 yards to the right rear,

GOOSE AND DUCK HUNTERS

SPECIAL-

$9.75 PER DAY

PER PERSON

ELECTRIC HEAT

3 MEALS AND LODGING

MODERN MOTEL TV

OPEN 4:30 A.M. FOR BREAKFAST

J'S OTTER CREEK MARINA

NORTH SIDE LAKE McCONAUGHY

PHONE KEYSTONE 308-355-2341

P.O. LEWELLEN, NEBR. 69147

FORT SIDNEY

MOTOR HOTELand RESTAURANT

Fine Food, Luxurious Lodging, Superior Service

COMPLETE HOTEL SERVICE-50 UNITS

Spacious Restaurant Large Heated Pool Banquet Facilities

Conference Room Paved Parking Lot Color TV

935-9thST. SIDNEY 254-5863

AUTHORS WANTED BY

NEW YORK PUBLISHER

Leading book publisher seeks manuscripts of all

types: fiction, non-fiction, poetry, scholarly and

juvenile works, etc. New authors welcomed. For

complete information, send for free booklet R-70.

Vantage Press, 516 W. 34 St., New York 10001

Kennels

VIZSLA-POINTERS

The Home of Champions

TRAINING PUPS STARTED DOGS

AKC FDSB REG BIRD DOGS

RT. #2, SCHUYLER, NEBR. 68661, PH. 402-352-3857

HUNTING AND FISHING

HEADQUARTERS

IN THE CENTER OF

NEBRASKA'S GREAT LAKES

Rods, Reels, Lures, Guns,

Decoys, Telescope Sights

Remington Model 788 $ 76.95

Remington Model 1100 $138.75

Ammunition & Hunting Supplies

Pacific & Bair Shot Gun Reloaders 4250

Hunting Permits-

Game and Duck Stamps

YOU SAVE MORE AT.....

BUD & NICKS

GUN & TACKLE SHOP

402 South St., McCook, Nebr.

Phone 345-3462

GOOSE AND DUCK HUNTERS

SPECIAL-

$9.75 PER DAY

PER PERSON

ELECTRIC HEAT

3 MEALS AND LODGING

MODERN MOTEL TV

OPEN 4:30 A.M. FOR BREAKFAST

J'S OTTER CREEK MARINA

NORTH SIDE LAKE McCONAUGHY

PHONE KEYSTONE 308-355-2341

P.O. LEWELLEN, NEBR. 69147

FORT SIDNEY

MOTOR HOTELand RESTAURANT

Fine Food, Luxurious Lodging, Superior Service

COMPLETE HOTEL SERVICE-50 UNITS

Spacious Restaurant Large Heated Pool Banquet Facilities

Conference Room Paved Parking Lot Color TV

935-9thST. SIDNEY 254-5863

AUTHORS WANTED BY

NEW YORK PUBLISHER

Leading book publisher seeks manuscripts of all

types: fiction, non-fiction, poetry, scholarly and

juvenile works, etc. New authors welcomed. For

complete information, send for free booklet R-70.

Vantage Press, 516 W. 34 St., New York 10001

Kennels

VIZSLA-POINTERS

The Home of Champions

TRAINING PUPS STARTED DOGS

AKC FDSB REG BIRD DOGS

RT. #2, SCHUYLER, NEBR. 68661, PH. 402-352-3857

HUNTING AND FISHING

HEADQUARTERS

IN THE CENTER OF

NEBRASKA'S GREAT LAKES

Rods, Reels, Lures, Guns,

Decoys, Telescope Sights

Remington Model 788 $ 76.95

Remington Model 1100 $138.75

Ammunition & Hunting Supplies

Pacific & Bair Shot Gun Reloaders 4250

Hunting Permits-

Game and Duck Stamps

YOU SAVE MORE AT.....

BUD & NICKS

GUN & TACKLE SHOP

402 South St., McCook, Nebr.

Phone 345-3462

and Lt.-Col. Sanford C. Kellogg's company galloping up from the left, the Indians wheeled and ran. The troops advanced cautiously in open order to the ridge, but after it was gained, they beheld the Cheyennes fleeing in all directions.

The incident was later exaggerated as a promotion of the Buffalo Bill image. There is some doubt that Cody actually killed and scalped the Indian. The wildest stories about the "scuffle" portray Bill and Yellow Hand (or Yellow Hair) grappling in the dust, one armed with a tomahawk, the other a Bowie knife. Other accounts are hazy about the details of the skirmish, but state that many bullets were fired.

At any rate, a young Cheyenne chief was killed. The death of that chief had little or no tactical importance except that it was a part of the action which headed off 800 reinforcements for Sitting Bull in the crucial days following the Rosebud and Little Big Horn defeats. The Yellow Hand incident does have importance in verifying the Cody legend. It is true that Buffalo Bill was a frontiersman. He was really a chief scout with the Fifth. He really did kill Indians during his career. And, he was apparently respected enough by the frontier cavalry to be in demand as a scout.

The battle site is quiet now, showing no trace of the blood shed that July day in 1876. Only the songs of prairie birds break the stillness. It is a quiet place, a remote place, a place to contemplate the order of the universe and man's place in it. The events of the past are wiped from the face of the land except for man's markers — insignificant in the largeness of the place.

Even visitors to the battlefield come at the convenience of nature, for the roads are gravel and occasionally are impassable during the wet days of spring. Contrary to the NEBRASKAland road map and travel guide, the battlefield is actually 23 miles northwest of Crawford, on the Oglala National Grassland division of the Nebraska National Forest, not straight west from the Gilbert-Baker State Special-Use Area.

On the other end of Nebraska a natural phenomenon claims the attention of travelers —an Artesian Well on the property of Harold Grotelueschen, about HVfe miles northeast of Columbus. To reach the Grotelueschen farm, drive 8 miles north from Columbus on 18th Avenue (which becomes Monastery Road as it leaves the city), turn east at the Christ Lutheran Church sign and drive 2 miles, then half a mile north.

The well was dug in 1912. The first well digger ran into stone at 77 feet and gave up. A second driller finally made it through the rock and came to water at 80 feet. According to the Geological Survey, the well is in the Shell Creek drainage area.

Water coming from the artesian well is probably part of a buried channel confined by a layer of clay with silt stacked on top. The pressure of confinement brings the water up under its own power to the tune of 250 gallons per minute, or 360,000 gallons a day. The flow varies with the amount of irrigating being done in the area, for the irrigation water comes out of the underground sources, too. Water from the well flows into a small creek on the Grotelueschen farm, still in its pure form, uncontaminated by surface pollution.

From the clear, cold stream of an artesian well to the quiet rustling of prairie grasses over an old battleground, NEBRASKAland past and present offers a wealth of interest. THE END

Outdoor Calendar

Squirrel - Cottontail - Grouse - Deer- Antelope- Turkey- Nongame Species- State special-use year-round unless HUNTING -September 1 -September 1 -September 18 -(Archery)-September 18 -(Firearm)-September 25 (Fail) —October 30 -Year-round, statewide, areas are open to hunting in season the otherwise posted or designated. Hook and Line FISHING All species, year-round, statewide. Bullfrogs, July 1 through October 31, state- wide. With appropriate permit may be taken by hand, hand net, gig, bow and arrow, or firearms. Archery-Nongame fish only, year-round. Game fish, April 1 through November 30. Sunrise to sun- set. Hand Spearing Underwater Powered Spearfishing -Nongame fish only, year-round, sunrise to sunset -No closed season on nongame fish. Game fish August 1 through December 31. STATE AREAS State Parks-The grounds of all state parks are open to visitors year-round. Park facilities are offi- cially closed September 15. Other areas include state recreation, wayside, and special- use areas. Most are open year-round, and are available for camping, picnicking, swimming, boating, and horseback riding. Consult the NEBRASKAland Camping Guide for particulars. FOR COMPLETE DETAILS Consult NEBRASKAland hunting and fishing guides, avail- able from conservation officers, NEBRASKAlanders, permit vendors, tourist welcome stations, county clerks, all Game and Parks Commission offices, or by writingiGame and Parks Commission, 2200 N. 33rd St., Lincoln, Nebraska 68503.

BERTH OF A MINESWEEPER

(Continued from page 23)Ray Dehart, Phil Cain, Lester Leaver, Dan Petersen, Jim Rybin, Ray Rybin, and Ralph Vierregger. Forming a corporation known as USS Hazard, Incorporated, they hired Rudolph Olsan to command the ship.

But no one calls him Mister Olsan. They call him Sinbad after the fictitious sailor in Arabian Nights. Sinbad, like his storybook counterpart, has sailed the seven seas. He retired from the U.S. Navy six years ago as a boatswain, then joined the merchant marine, working on commercial vessels that sailed to every major port in the world until an offer came from the newly formed Hazard corporation.

This was a chance he could not let pass. What more could anyone want, especially if the ship is within the limits of your home city? At 44, he is single and retired, yet busier than ever performing all duties from captain to tour guide and living on board a ship he is proud to run, even though she never breaks her mooring.

Although she carries no live ammunition, the Hazard is armed with 9 guns — 6 twin 20 mm automatics capable of firing 420 rounds a minute, 2 twin 40 mm automatics capable of firing 180 rounds a minute, and a 3-inch semi-automatic capable of firing 12 rounds a minute to a distance of 8 or 9 miles. She carried these guns during the war for protection from enemy fire during her minesweeping missions. She was also equipped to explode moored, influence, and magnetic mines. Moored mines are anchored to float just beneath the water's surface in hopes that a ship's hull will strike them. Influence mines are designed to detonate in response to the pounding of a big ship's engines. Magnetic types are designed to go off when the magnetic field created by a ship's electrical system crosses them. She had sonar to seek them out and sweeping, 1,600-foot trailers to explode the submerged types, or cutters to bring them up for surface destruction.

Displayed on board is the diary of an enlisted man who, with the flavor of a landlubber forced to sea during war, kept count on the minesweeper's accomplishments. His account is a colorful complement to the ship's official log. It tells the story of day-to-day danger in the South Pacific and China Seas from the day she was commissioned — October 31, 1944 —until the end of the war.

Human as all sailors are, the Hazard's crew must have really whooped it up during New Year's Eve in 1944, knowing they would sail for Pearl Habor in less than a week. The diary states that during a liberty in Oakland off San Francisco Bay, where the Hazard lay in her berth, three crew members stole the name plate from the Central Bank in Oakland and were slapped in jail for the night. It was a good liberty, the author wrote.

But their fun was short-lived. On April 6, 1945, the Hazard was at Okinawa, 54 NEBRASKAland having been there almost a week right in the thick of things. Wilbur Anderson, author of the diary wrote: "Bad day today. Attacked by 4 planes, 2 shot down. One flew over our bow and crashed. No. 4 gun and crew wiped out."

From the war near Japan the Hazard moved on, cutting a path through enemy mine fields for larger, sister ships to follow. On June 29, just when things were easing, a new message arrived: "We got word today we are going to sweep the China Seas, the biggest operation of its kind. We leave the Fourth of July."

Still in the China Seas July 27, Anderson had some time for hindsight: "Reports of operation at Okinawa. Airfields jammed with planes. Over 2,000 miles of road built already. A million troops on island. This anchorage we're in was swept by us April 5, and if we had known then what we know now, we really would have been praying. Big guns were captured on all sides of us. Suicide boats by the hundreds, and we were right under their noses."

Japan surrendered August 14, and Anderson wrote: "The news says the war is over, but these mines don't know it. We're in the middle of a field in the North China Sea. The sweepers are as active as ever and mines are being cut all morning. We cut two. One exploded in our gear and we lost it."

October 1: "At anchor in Sasebo Bay. The skipper was awarded the Bronze Star for the good work of the crew, but did he thank the crew? I'll let you guess." And, October 2: "We went ashore today. I can't say it was good liberty, but it was something new and different. We were in Sasebo. Most of the buildings were flat to the ground. Our bombs did a good job on that place. We didn't have time to buy any souvenirs. Most of the women were clean and nice looking. One lady at the bank liked the picture of my wife very much. Going back to the ship, the bay was very rough and the wind was blowing hard. Water came over the bow of our boat (a 28-foot Higgins landing craft) by the bucket. We should be old salts by now, but who in the hell wants to be an old salt?"

November 4: "Started check sweeping today and really hit a nest of them. We got 10, making 137 total."

On November 8 the crew didn't have the will to work: "Something came up that looked like a mine, so we reported it as 'a horned sea turtle' because if we cut any mines in this area we would have to sweep another day. An officer investigated and later reported that our 'horned sea turtle' had blown up under gunfire." All in all,.the Hazard destroyed 144 mines during the war. She carried an 85-man crew, 9 officers, and 5 chief petty officers. Powered by 2 900-horsepower, 2 500-horsepower, and 2 300-horsepower diesels, she went through the thickest part of the war without major damage, opening the way for bigger battleships behind.

Now she is anchored in the Missouri River, a memento of days gone by when war casualties were a way of life, content to let old salts reminisce on her decks and youngsters climb and swing on her guns. THE END

A DISMAL TRIP

(Continued from page 18)edge. We almost passed by before I noticed that she was not just lying there, but that she was actually imprisoned in loose sand from a spring flowing into the river.

"Hey, that cow is stuck in there!" I yelled to Bob. We promptly pulled over to the side, tied up, and surveyed the situation. Soon Rick and Dennis paddled up and we got to work digging the critter out. That turned into a two-hour chore. The loose sand on top was more like concrete down deep. We dug and pulled and got one leg free. We figured the poor cow had been in there for at least three days. She barely had strength to hold up her head.

Finally, the second front leg came free, but that wasn't enough, so we started digging out the heavy end. Those legs seemed to be yards long. Using a heavy rope around the body, we all leaned hard and finally pulled her free. A little stumbling around and the cow got up, but her legs must have been completely numb. She walked only a few yards before lying down.

After washing off most of the sand and mud, we climbed aboard our craft and continued our journey, hoping the cow was happy and well, proud of our mission of mercy.

Back to the trees. We switched lead several times so that a fresh sawer could climb inside the tangle of branches and limbs. Sometime around the thirtieth tree, Dennis casually mentioned that he had almost decided to leave at home the little brush saw we were using. This pronouncement was cause for much speculation as to how long we would have been in that canyon whittling away on these limbs with only knives and hatchets. It would have been an insurmountable task. It was bad enough with a good saw.

Several short stretches of fast water added excitement to the day, and then came the waterfall. Our midday meeting with that surprise proved not to be the last. It did make us a little more cautious, though.

Farther down the twisting course of the north fork we heard rough water again. Several stretches of white water were welcome diversions for us, and then a louder rumble greeted us. Sure enough, we rounded a bend to see Dennis and Rick standing in the river hanging onto the canoe rope. More falls. A short conference followed as we viewed the situation from every angle. Rick went below to scout the river ahead for a ways and reported back that it looked clear, so we decided to unload the canoes then walk them through empty.

Everything went fairly well and we felt we had accomplished something. We voted to spend our second night on the hill above the falls since our gear was all unloaded anyway, so we started the wood-gathering ritual. Canned chicken with noodles went over the fire and soon disappeared into our hungry crew. Somehow, Bob and I got the lead again next (Continued on page 58)

Roundup and What to do

OCTOBER IS THE time to stalk the hills and plains of NEBRASKAland for a variety of game species. Cottontail and squirrel are both on the hunter's list with bag limits of 7 and possession limits of 21 each. Both seasons are open until after the first of the year.

Grouse season continues into October. These elusive birds offer plenty of thrills for the hunter who goes after them. Both prairie chicken and sharptail are fast fliers. They get up quickly and are gone. The pursuit of grouse takes hunters into the quiet loneliness of remote regions of NEBRASKAland.

Rail and snipe seasons open in October. Both Virginia and Sora rail are limited to a daily bag of 25 with 25 in possession. Snipe limits are 8 and 16. Antelope, too, are under the gun from October 1 to October 3. Bow-and-arrow hunters take over October 4 until the end of the month. Archery deer season is open throughout the month into December, excluding the days of the firearm season.

Turkey season opens with a bang at the end of the month as gobblers become targets for a 16-day season. No matter what the species, Jeanine Giller is ready with a Vizsla puppy. An active miss, Jeanine lists UNO Wrestling Princess, Panhellenic Girl of the Year, and Theta Chi Dream Girl among her titles. She was also runner-up for the Miss UNO crown, and second runner-up in the Tomahawk Beauty Contest. A journalism major, Jeanine plans to teach after graduation. Meanwhile, she is active in college activities. She was a member of the student senate and belongs to Chi Omega sorority. She has been on the Dean's List two semesters, and is vice-president of Waokiya-UNO's Mortar Board.

Jeanine lists photography, swimming, diving, and sewing among her hobbies. Many Nebraskans have made a hobby of Big Red football, and last year that interest paid off with fantastic results as the Huskers ran away with the nation's top honors. This year, again, the Big Red machine faces tough competition. October includes three home shows, the first against Texas A & M October 2, another against Kansas October 16, and a third contest against Colorado October 30. All the color and pageantry of college football will be there for Nebraska fans. Other college and high-school teams hit gridirons across the state. From the ranks of high-school teams will come some of the future material for Big Red. At Hastings, the college combines music with football for the fall Melody Roundup when high-school bands entertain at half time.

Some 30 to 40 runners will take the scenic route October 17 when they compete in the Tri-State Marathon, winding up in Falls City. The race starts in White OCTOBER 1971 Cloud, Kansas, proceeds to Rulo, into Missouri about three miles, back to Rulo and into Falls City. This is the sixth annual event, and runners have come from nine states to participate. Best time to date is 2 hours, 30 minutes, 35 seconds clocked by Jay Dirksen of Brookings, South Dakota.

Fishing is still very much in the picture during October with the beginning of fall trout, walleye biting along the shorelines, and hungry largemouth bass. One of the state's top social events takes place in Omaha in the form of the Ak-Sar-Ben Coronation and Ball. Here all of Nebraska puts its best foot forward with the regal color and pageantry of the crowning of its king and queen.

Another kind of queen is crowned in McCook the next evening as the Junior Miss Pageant reaches its exciting climax there. The winner of that contest will compete in the National Junior Miss Pageant later in the year.

Nebraska heritage hits the scene in October with the Prairie Schooners Square Dance Festival in Sidney October 2 and 3. The Annual Fall Festival and Tour of Homes at Brownville brings back the Gay Nineties, and a Country and Fiddle Music Jamboree at Long Pine October 31 through November 1 revives the kind of music that entertained our ancestors.

For rock collectors, there is a state Rock Show at Ogallala October 8 to 10 in conjunction with the state show of the Nebraska Association of Earth Science Clubs.

Other events include the Lord's Acre Festival at Endicott, and the thousands of impromptu events that fill the fall months from wiener roasts to hay-rack rides. October is young and vibrant in NEBRASKAland.

What to do 1-3 —Firearm Antelope Season continues 1-November 9 —Rail Season continues 1-November 18 —Snipe Season continues 1-December 31 —Archery Deer Season continues 1-January 31 —Squirrel Season continues 1-February 29 — Cottontail Season continues 1 — Grouse Season continues 2 —Farmer's Day Celebration,Kimball 2 —Lord's Acre Festival, Endicott 2-Texas A & M vs. Nebraska, Football, Lincoln 2-3 —Prairie Schooners Square Dance Festival, Sidney 3 — Registered Trap Shoot, Cozad 4-31 —Archery Antelope Season continues 8-10 —Nebraska Association of Earth Science Clubs State Show, Ogallala 8-10 —Nebraska State Rock Show, Ogallala 9 —Hastings College Melody Roundup, Hastings 10 —Fall Festival and Tour of Homes, Brownville 10 —Sod House Society Annual Meeting, Dunning 16 —Kansas vs. Nebraska, Football, Lincoln 17-Tri-state Marathon, Falls City 22-23-Ak-Sar-Ben Coronation and Ball 23-24 —Nebraska Barbed Wire Collectors Association Fall Show, Norfolk 24 —Junior Miss Pageant, McCook 25 - Veterans Day Parade, Central City 26 — Smorgasbord, Wausa 29-30-Fall Festival Days, Cambridge 30 —Colorado vs. Nebraska, Football, Lincoln 30-31—Turkey Season opens 31-November 1 —Country and Fiddle Music Jamboree, Long Pine THE END

A DISMAL TRIP

(Continued from page 55)morning — probably because it was then our turn to saw trees — and it was only a few hours before we heard telltale rumblings ahead. Easing our pace, we grabbed grass and bushes along the side. A 20-foot stretch of white water lay ahead, but beyond that just a few yards was a real falls, probably the grandaddy on the Dismal. A small one dropped only 4 feet, but the second was a real dandy —at least a 12-foot cataract. Big rocks protruded like huge teeth from the edges of both. Here was a real problem.

As usual, we scouted the river below for additional falls before deciding what to do. It looked clear. We knew we had to unload the canoes —it was just where and how to reload them that puzzled us. Finally, with all that experience behind us, we decided to tote the gear up the hill, around the bend, and down the hill back to the water. We would shoot the canoes over by themselves. There was plenty of water to protect the- empty hulls, and the pools were big and deep enough to prevent damage.

Rick was the "pool shark" by this time, so he went below to catch the canoes as they dropped. We didn't "want them to get away. So we attached a 50-foot rope to one, steered it into the center of rocks as best we could, then let it go. With a swoosh and a smack the first canoe went down. Loosening the rope, we prepared the second craft for its descent. Again all went well, but this time we had no fish in the hull.

"If we keep this up, your gear may even dry out," Rick shouted triumphantly, towing the two canoes around to the loading area. Dennis, between taking his own pictures, tried to lure a trout with his fishing rod, but we had, without doubts alerted them all to our presence. Still in the lead, Bob and I found the going easier. Trees were virtually absent, or didn't block the entire width of the stream.

"This is much better along here," Bob tossed back over his shoulder as we slipped around the end of a tree. "Maybe we are out of the woods and can relax the rest of the way."

Two river bends later all that sort of optimistic talk ended. A small canyon suddenly loomed ahead —not deep, but very narrow. The river cut through an opening no more than eight feet wide, and a rocky ledge on the right put all the water into a skinny, deep band that raced along the left wall. A heavy bush stuck out from the side. That probably gave us the only reason for entering. We just couldn't resist a bush that we could go under without cutting.

The water was moving at least 25 miles per hour through there. We got the canoe in, but then it dropped into a crevice. The boat was just a bit wider than the opening between the rocks. I jumped out onto the ledge but water poured in, filling every open cranny. Rick and Dennis were right behind us, and as Bob's paddle and life preserver floated merrily down the current, we began pulling the other gear out. The canoe filled with half a ton of water in seconds.

"Well, I guess our stuff will never dry out," I lamented as we dragged the boat onto the ledge and tried to dump out the water.

With three of us dumping the canoe while Rick squeezed water from some of our duffle bags, we became seaworthy again in about 10 minutes.

"Guess we'll walk our canoe through," said Dennis, who periodically mumbled about the number of bruises his new canoe was rapidly acquiring. "This is a pretty tricky little chute through here, isn't it?" he observed.

"Didn't you ever wonder how the river got that name?" I asked, stashing a sodden bundle back on the wet, gritty, bottom of our scarred canoe. "Can you imagine an Indian in a birchbark canoe calling this anything but dismal?"

"Let's forge ahead and see what other goodies await us," Rick suggested as Dennis readied to ease their canoe down the chute. "We could stop for lunch, but I guess this isn't quite the place."

Another 20 yards or so put us back into calmer water, and a comparatively quiet session of paddling for several miles. We even raced a short stretch when Rick and Dennis came creeping up from behind.

"We can't be far from the Mullen bridge," Dennis said. He referred to his

They'll tickle your taste, bud. Weavers Potato Chips 58 NEBRASKAlanddetailed maps periodically and was the expedition scout because of all the preliminary work he had done, charting the course. "I figure we'll reach it within the next hour."

When we did hit it — ahead of Dennis' prediction — there was another surprise for us. Rather than a nice, spacious bridge, we passed under the highway through a large, long, dark culvert. Again, the river was constricted into a five-foot-wide stream which virtually shot through. Not knowing how much of a drop awaited us at the other end, we tried to slow our peed, but it merely wore the paddles down pushing them against the ribs of the tube, and it turned us sideways.

"Let's hope for the best and give it hell!" Bob yelled.

"I guess we have to," I agreed, putting the spurs to our craft.

A splashdown of less than two feet awaited us, and we gaily pushed over to the far side of the little lagoon to watch the expressions on the other two guys' faces when they came plopping out. We really didn't have much chance to warn them anyway. We could hear their echoing voices in the tube and tried to shout that it was O.K., but they were zooming out by then.

We were on the full Dismal now, as the south fork entered just yards from where we were.