WHERE THE WEST BEGINS

NEBRASKAland

July 1971 50 cents ARCHERS GEAR UP FOR BIG GAME EGG SACKS PUT TROUT IN THE PAN HEARTLAND OF THE NATION PLEASURE BOATS ON THE MISSOURI

For the Record... NOISE ABOUT NOISE

The first wheel, it has been said, probably squeaked, and that was the beginning of noise pollution. Unwanted sound can be a pollutant. Like other pollutants, it makes the world we live in not only unpleasant, but also unhealthy.

We don't know what the per capita noise production is. But we do know it's going up. A widely quoted "intelligent guess" says that in United States cities, noise has increased about one decibel (db) each year for the past 25 years. (A decibel is the unit used to measure loudness.) The lowest sound that the best human ear can hear is one db. Leaves rustling in the wind measure about 10 db.

Dishwashers, air conditioners, drills, blaring car horns, and screaming sirens fill our homes and streets with noise. There is no escape. Even the once-silent wilderness now echoes to the noise of mini-bikes and snowmobiles. And, these noises are likely to mushroom if the SST (Supersonic Transport) goes into wide use. The controversial plane will fly faster than sound, and so will drag behind it that trail of ear-splitting, glass-shattering noise we call the sonic boom.

Most of us know that a sudden, very loud noise can cause temporary or permanent deafness. But until recently, few people realized that repeated exposure to noise at lower levels has the same effect. Studies show that spending 8 hours daily at an 85-db rate leads to hearing damage. It has been shown that citizens of noisy, industrial nations have far poorer hearing than those living in less-advanced and quieter countries.

Tests show that many American teens have a great deal of hearing loss. In some cases their hearing is no better than that of a 65-year-old. One of the causes may be amplified rock music, which has been metered at a thundering 120 db.

Noise doesn't affect just ears. A sudden loud noise makes the heart beat faster, increases blood pressure, and causes the pupils in the eyes to dilate. It can lead to heart attacks in persons who already have heart ailments.

In short, there is no doubt that noise can cause deafness, and there is some concern that it may lead to other physical damage. It is also costly when it reduces worker efficiency, or in the case of sonic booms, cracks windows and walls.

It is possible, though sometimes expensive, to reduce noise. (Someone already has invented a quiet jackhammer.) Getting co-operation is another matter. Laws can help, but so far there are very few laws about noise. And where there are laws, they are often ignored. New York City has laws against sounding auto horns and rules limiting city noise to 88 db. But these are rarely enforced, as any noise-frazzled New Yorker knows.

It seems that people will have to make noise about noise if we are to lower the decibel rate. But many still think of noise (as they used to think of air pollution) as a part of progress.

If the decibel level keeps going up at today's rate, we are told, we'll all be deaf by the year 2000. That's something of a scare statement. But there is a need to educate people, and to let them know that noise may be dangerous. That's what this is all about.

But can you hear me?

Speak up

NEBRASKAland invites all readers to submit their comments, suggestions, and gripes to SPEAK UP. Each month the magazine will publish as many letters as space permits. Pictures are welcome. NEBRASKAland reserves the right to edit and condense letters. Editor.THANK YOU - "Please convey my thanks and my congratulations to Carol Nelson of Wahoo for her poem on the inside back cover of the May NEBRASKAland.

"I read it the day the magazine came, and have read it several times since. In fact, I have just finished copying it into my notebook of poems I want to keep.

"I am a great-grandmother and can visualize the things Carol mentioned because my mother was a small girl living in Indian country. She told of Indians around her Sidney home peering through windows and wanting something to eat.

"I could never put thoughts into words as Carol has done, so I want my grandchildren to read this poem. I think it is part of their heritage." —Mrs. Ruth L. Buettner, Grand Island.

FANTASTIC PHOTOGRAPHY - "Felicitations for your article Chronicle of Change in the February 1971 issue of NEBRASKAland.

"As a Frenchman who is a western writer, I appreciate articles about the Old West.

"I like the photos which illustrate the article. The old ones made by William H. Jackson and the new ones by Lou Ell are fantastic. I like the comparison and illustration of the change of nature." — George Fronval, Paris, France.

WRONG CITY-"The photo on pages 38 and 39 of the April issue of NEBRASKAland (Electric Elusion) is printed backward and is not a picture of the Omaha horizon, but is a shot of the combination bridge between Sioux City, Iowa, and South Sioux City. The picture was taken from the Iowa side of the Missouri River facing southeast." —William P. Hamann, Jr., Winnebago.

The photo was printed in reverse for technical and visual reasons. There are no excuses for the inaccurate caption save the slip of the typewriter, however. — Editor.

NOT FOR ME —"Please do not renew my subscription. I find that NEBRASKAland slants too much toward hunting and fishing and to the western end of Nebraska.

"Having lived in the eastern end of the state, I would have appreciated stories and pictures about Omaha, its business, history, parks, etc; the capitol and University of Nebraska; Arbor Lodge, of nation-wide fame; farms and towns of eastern Nebraska. Most all of your stories and pictures had a way of ending up in western Nebraska, not that I didn't enjoy them — but why not eastern Nebraska?

"A large percentage of your stories, pictures, etc., featured hunters and fishermen. I prefer to look at living animals and fish and birds that live in Nebraska. I very much dislike viewing the trophies of hunters and fishermen.

"As you can see, the magazine is not for me — not for the present time at least." —Emily J. Johnson, Seattle, Washington.

GUNNING FOR GUNS- I'm tired of reading and hearing some people complaining about United States' citizens' possession of guns. There are plenty of us with our normal quantity of horse sense who are well aware that there is a minority in our country that would like to see our nation disarmed for a very easily seen reason.

"Part of this faction may think the rest of the citizens are a bunch of idiots, but we are smart enough to know propaganda when we hear it. Of course, it is possible that some of these complainers are not conspirators, only uninformed do-gooders.

"As for the number of deaths caused by guns, Bruce B. Johnson of East Lansing, Michigan, whose letter appeared in the May Speak Up, mentioned 20,000 deaths and 200,000 injuries. He did not, however, mention how many of these deaths were of innocents and which were those of criminals or would-be criminals. He also ignored the fact that those who are criminally inclined use guns since they are available, but, lacking guns, would commit their deeds with other weapons

"The writer also failed to mention the fact that (Continued on page 12)

NEBRASKAland

DAREDEVIL HERO

by W. Rex AmockROARING POWER BOATS knifed the mirror-like surface of Crystal Lake while picnickers, Sunday strollers, and loafers flocked together on the shore. The myriad outdoor activities during this particular June Sunday in 1970 typified those of any warm, summer day at the lake four miles west of South Sioux City.

About 3 o'clock that afternoon, boat traffic was heavy on the 60-acre lake, and Wally Beerman of Dakota City pointed his rugged, inboard craft toward Lik-U-Wanta Beach. A celebrity of the water set, Wally is extremely aware of water safety. Whenever boat traffic is heavy, he beaches his craft in favor of shoreline activities until things quiet down. One of a rare and courageous breed, Wally is a daredevil. His specialty is soaring through the air, swinging from a flying kite. The scary looking rig, which takes him as high as 150 feet above the water, is 16 feet long and 12 feet wide, and made of paper-thin material.

Thousands have witnessed his extraordinary aerial feats. Each summer he thrills spectators at the Rivercade Celebration between South Sioux City and Sioux City, Iowa, on the bulling Missouri River.

This time, Wally was just boating and plunged into a vigorous volleyball game minutes after beaching his craft. Several water skiers were skimming across the lake when suddenly, out of the corner of his eye, Wally saw one of them hit the surf. There was, of course, nothing unusual about a skier taking a fall, but this one slammed the surface hard. Wally focused full attention on the mishap and, as the wake died, noticed the victim motionless in the water —floating face downward. He raced to the water's edge for a closer look.

By this time, the tow boat was bobbing about 80 yards from where the skier had fallen. The driver yelled to his friend, but, getting no response, dove into the chilly water and began swimming to the rescue.

Wally realized the fellow had panicked and would never make it to the downed skier in time. He hollered to Bill Haafke of South Sioux City, who had also been playing volleyball, and the two swung into action. Together, they pushed Wally's boat off the sand. A whir of the power-packed inboard sent the vessel lurching toward the immobilized skier.

Seconds later, Wally and Bill pulled 20-year-old Rena Barker of South Sioux City into the boat. Wally began mouth-to-mouth resuscitation while Bill headed the craft 8 NEBRASKAland back to the beach, showing no mercy on the throttle. Meanwhile, Wally's wife found a telephone and called for a rescue unit. Wally worked feverishly to revive Rena as she lay limp and unconscious in the boat.

An old-timer with the uncertain, Wally refused to abandon hope where another person might have called it quits. Before long, his dogged determination paid off. Rena began responding to his expert efforts, and recovery was incredibly rapid. The danger was past. Rena was safe!

In her own reconstruction of the mishap, the girl remembers losing balance and striking her head on a ski as she went down. The blow knocked her unconscious and out of breath.

By the time the rescue squad arrived, Rena was ready to ski again, but after a thorough examination, she was advised to rest the remainder of the day.

It was business as usual at Crystal Lake. The threat of tragedy was gone. A young woman's life was saved. And, the credit was given where due — to the fast and effective action of a brave man, a daredevil at heart, and, in this case, a quick-thinking hero.

THE END WILDLIFE NEEDS YOUR HELP Fire is but one of the many hazards faced by wildlife. The No. 1 hardship is the lack of necessary cover for nesting, for loafing, for escape from predators, and for winter survival. You can help! For information, write to: Habitat, Game Commission, State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebr. 68509. Provide Habitat... Places Where Wildlife Live Join the ACRES FOR WILDLIFE PROGRAM JULY 1971 9

THE HIKER'S MOTTO is "travel light". But say you are going to be out all day, trekking the Sand Hills or exploring the Pine Ridge. Rain gear, a lunch, and extra film, if you're a photographer, are necessities; not enough to bother with a knapsack but too much bulk for pockets. How do you carry these few, but essential items?

Many people have found the belt (or "fanny") pack an ideal solution. Originated for skiers, this small but versatile pack will quickly become a necessity for any outing. It carries the load —usually more bulk than weight — out of the way at the small of the back, does not hamper sitting or climbing, and its contents can be reached without removing the pack.

Materials include a yard of army duck or similar durable, water-resistant material (nylon is also excellent), a piece of soft cloth for lining if desired, a heavy, 12-inch zipper, belt webbing and buckle, and a spool of medium-weight thread.

Begin by drawing and cutting the pattern, then pin it to the fabric and cut out the pieces. If your waist is smaller than 24 inches, take out the difference from the pack itself, deducting equal amounts from the top, bottom, side, back, zipper, and optional lining.

Cut an opening in the side, fold back the edges, and stitch in the zipper (a No. 9 is used here) close to the folded edges. Reinforce the seam by restitching along the zipper's outer edges.

Next, center the belt along the back piece and sew them together.

Stitch the diagonals of the side and back together first, then the straight edges of the bottom and top pieces to the straight edges of the back.

If you wish to install a lining, it should be attached at this point. The material used is 10-ounce, single-filled duck, washed in hot water to make it soft and flexible. Place the lining with the right side against the wrong side of the top and stitch it into the straight seam of the top, leaving five-eighths of an inch free at each end.

Stretch the lining across the back, top, and side and stitch it into the straight seams between the bottom and back, again leaving five-eighths of an inch free at each end. Turn the lining right-side-out, then tuck in 10 NEBRASKAland the ends of the lining and stitch them to the back across the belt. Do this on both ends.

The pack is now turned right-side-out. Slip the belt out through the ends. Fold back a quarter of an inch at each end where the side and back join and stitch the folded ends to the belt.

The final step is to install the buckle by lapping the webbing over the buckle post and sewing them together. The tongue of the belt is then turned back upon itself an inch or so and sewn.

Check all seams and reinforce any that appear weak. Depending upon the fabric, you may wish to waterproof the pack. Commercial sprays are available for this purpose.

The finished pack can be worn several ways. The belt can be slipped through your trousers' belt loops or worn lower on the hips. Some people prefer to wear it on their stomachs, permitting even easier access. Wearing it bandolier-fashion over the back of the shoulder is also reasonably comfortable.

Use this handy little pack just once, then see if you ever go hiking without it again.

THE ENDHOW TO: by Greg Beaumont MAKE A "FANNY" PACK

SPEAK UP

(Continued from page 5)the population of the United States is about 3 72 times larger than Great Britain's and 25 times larger than Sweden's. Also, some acts committed here are not considered crimes when they occur elsewhere." --Grace Baldwin, Newport.

SMART BIRD-"My neighbor, Ray White, has a sparrow which, for three years, has nested in the tractor he uses every day. She has raised her brood successfully every year, despite the difficulties involved. There is a cranny behind the battery box, fairly close to the motor, which is warm, well concealed, and seemingly suitable for a nest. The sparrow sits on her eggs until Ray goes to the field, but she leaves when he starts the engine. When he comes in, she goes back to the nest until he leaves again. Evidently, the motor keeps the eggs warm while she is not on the nest. After the birds are hatched, she and the male feed them.

"Farming readers may wonder what happens when Ray changes work with a neighbor and doesn't come in at noon. That doesn't disturb the sparrow family one bit. Both birds are right there when the tractor stops in the neighbor's yard and the babies are fed on schedule. In fact, the mother seems to know where the tractor is all of the time, because once or twice Ray has left the tractor in the field and she is right there to attend to her young." - Harold Jeffery, Martinsburg.

In a later letter, Mr. Jeffery added a postscript to his bird tale. It seems a cat got the mother sparrow, leaving both families in desolation. — Editor.

TO SELL OR SAVE-"If this be treason... SOS? SOS! SELL our State? Unthinkable! Sell our State? The unsinkable Beautiful, spacious, Rolling plains? Forests and streams? Clear skies and clean air? For financial gains? Let SOS mean SAVE OUR STATE Don't let it die The choked death of Yellowstone and Yosemite SAVE OUR STATE!"I know Lorene Moranville of Bayard (SOS-SELL OUR STATE, Speak Up, April 1971) was speaking figuratively. I took it literally! Next to Nebraska itself, I love NEBRASKAland - the best magazine in the country." —Mrs. Vilma Toufar, Columbus.

NEBRASKAland RELIVE NEBRASKA'S PAST OLD 1880 TOWN INCLUDING HENRY FONDA BIRTHPLACE EXCITING ANTIQUE CAR COLLECTION EXTENSIVE RAILROAD DIS U.P. CENTENNIAL EDUCATIONAL NERY EXHIBITS HIBITS OPEN MEMORIAL DAY-THROUGH DAY FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION REGARDING SPECIAL TOURS WRITE STUHR MUSEUM, BOX 636, GRAND ISLAND, NEBRASKA 68801

prairie doctors

Night or day, fee or no fee, the dedicated healer on horseback came at a gallop when summonedHE WAS A healer, but often all he could do was look professional and watch people die. The bitter irony of death was a doctor's daily bread in early Nebraska when amputation and bleeding were among the most frequently used means for "saving" lives.

Any serious injury to a limb was a double hazard in the mid to late 1800's, for modern antibiotics were not available to halt the decay of flesh. Blood poisoning was a scourge, and amputation of the injured limb was most often the safest course of action.

The germ theory was still undeveloped, and sterilization was unknown. Doctors rinsed their instruments before using them —to remove the dust —and washed their hands only after the operation or examination. Instruments were stuffed in pockets, and catgut for sewing up surgical incisions hung from lapels where it was handy.

There were no vaccinations or inoculations, and epidemics spread unchecked. As wagon trains moved west across Nebraska, cholera stalked the trail. In June of 1849, as many as 200 emigrants had already died east of Fort Kearny.

Cholera made a mixed imprint on Dr. David Maynard. A fugitive from his sharp-tongued wife, and $30,000 in debt, he headed west with a mule, a buffalo robe, a gun, some books, and his instruments. He treated cholera until he came down with it himself, but he recovered because, as he said: "Nobody meddled with me."

Later he stopped to help a family struck by cholera. Before morning the husband, son, and mother of Mrs. Israel Brashears died. Dr. Maynard tossed his belongings in the back of the Brashear's wagon and they started down the trail together. When they reached the coast they were married.

Today's doctors would shudder at the everyday conditions under which wagon-train doctors functioned. There were no lights except candles which could blow out in the middle of a delicate nighttime operation, and wagon beds were the only "work tables".

While wagon-train doctors were fighting cholera, military surgeons were busy patching up troops wounded in various skirmishes, and fighting diet-related diseases. Scurvy, for example, rivaled cholera with its lethal attacks. Gradually, doctors came to realize that diet was the cause, and military surgeons began scouring the countryside in search of wild fruits and vegetables to ward off the disease. Dr. William S. Latta, surgeon of the 2nd Nebraska Cavalry, had his men gather wild gooseberries to make a lifesaving stew. Wild onions, too, provided dietary balance in the early years.

The doctor was many things in a fort besides physician and surgeon. Captain John Summers, a surgeon, was the commanding officer of Fort Kearny in 1861. Sometimes the doctor was a negotiator with the Indians. Dr. McGillycuddy successfully treated Crazy Horse's wife and the chief became his friend. Later, Crazy Horse came to Fort Robinson to make (Continued on page 54)

14 NEBRASKAland

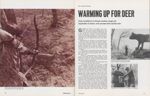

WARMING UP FOR DEER

by Lowell Johnson Field conditions at Omaha archery range are duplicates of nature, and success here carries overGARBED IN FULL camouflage suit, complete with mesh hood covering all but his eyes, the archer silently slipped from tree to tree, cautiously and carefully scrutinizing the woods ahead. Any second, a white-tailed buck could go bounding, startled by some sound or movement. Or, perhaps the deer would be calmly nibbling leaves or taking his ease in the afternoon sun.

Stalking deer or waiting in a tree blind for one to stroll by calls for quiet and caution. Movements must be slow and minimal. When stalking, a few steps are taken, then a long pause with careful examination of terrain ahead. A deer has keen senses — far greater than man's — and is always using them for his own well being and protection.

There! Just to the right of that tree ahead —a buck. Maybe 40, maybe 50 yards away. Can't get any closer without being spotted. Have to try a shot from here.

Being an experienced bow hunter, the last pause was made leaving ample clearance from brush for a full draw of the broadhead. But, a half step to the right is necessary to clear the line of fire from intervening branches.

"Now we'll see, Mr. Buck. Your time just may have come; if you'll just hold steady."

In seconds, the arrow is on its way. A solid "thunk" signals a hit. But, the deer does not dash away. It stands immobile and unfeeling, for the deer is actually a three-dimensional, foam target wrapped with painted burlap. It does, however, sport a real set of antlers, saved from a white-tailed buck taken the previous season and mounted for realistic appearance. The rack is that added touch which makes the unreal come alive.

A simulated deer hunt is not so unusual, at

least for some bow hunters of the Omaha Archery

Club. At their field range south of Papillion, OAC

members have installed two "legs" of 14 targets

each. As a shooter runs the course, he is faced

with animal targets at various, unmarked distances

which he must estimate. They range from

15 to 80 yards in 5-yard increments. Realism is

the keynote. Animal targets in natural woodland

settings with trees and downed logs, and even

elevated platforms from which hunters shoot,

JULY 1971

17

give the entire facility a scenic but practical

function.

give the entire facility a scenic but practical

function.

Much time, effort, and money have gone into developing the range. A line of conventional targets near the entrance is lighted for night shooting, and several times each summer it really draws a crowd. A fireplace, adjacent to a roofed shelterhouse, is under construction.

But, it is the remainder of the 22-acre plot that is most interesting to the club's serious hunters. A tractor and mower keep the green swaths between target and shooter tidy and attractive. These paths are laid out as scientifically as any golf course, utilizing the land area to the utmost advantage while also giving every combination of shot likely to be encountered in the field. Some go sharply uphill, others steeply down, and some are virtually narrow corridors through dense woods. All appear to have green carpets between shooter and target.

Perhaps only serious archery-deer hunters devote much time to extensive workouts before the season. At any rate, members of the Omaha club did very well during the 1970 season, chalking up about a 40-percent success. Comparing this to the statewide archery success of 19 percent hints that the field range paid off. In many cases, it is difficult for Omaha archers to get into the outdoors because of the distances involved. Some smaller towns have deer munching in fields just a few yards away from the city limits, or at least within a few miles. Such is not the case for metropolitan Omahans, who may spend nearly as much time commuting to and from their hunting sites as they do hunting.

Each year since the archery season opened in Nebraska, a greater number of sportsmen have taken up the challenge. Last year more than 4,800 permits were issued for deer alone, making big-game hunting with a bow very popular indeed.

Interest in hunting runs high among the more than 40 member families of the Omaha club. At one session prior to last year's deer season, over 60 archers, club members and friends, put in a "warming-up" session by running the 28 field positions. An estimated total of 125 different hunters made the rounds sometime before deer season.

Late in April, members of the Omaha Archery Club started to put in leisure hours fixing the area up for the busy months ahead. Backstops had to be erected again (after cattle worked them over), target faces put on, wind-blown branches cleared away, and grass mowed.

Eventually, many of the paper animal targets will be replaced with 3-D stryofoam types, making a round of shooting as near the real thing as could be desired.

"These new critters are great," agreed three shooters making the rounds one afternoon. Bob Dinslage, secretary of the club, Noel Miller, a member who downed the best deer during the 1970 season, and (Continued on page 55)

18 NEBRASKAland

A thing about BEES & WASPS

With life style that rivals man's in complexity, these insects are constant source of wondermentMEMBRANE-WINGED insects, or Hymenoptera as entomologists call them, represent the world's wasps, bees, and ants.

Watch a solitary wasp sometime. Never having known its parents and never having learned from others of its kind, it selects a nesting site and excavates or constructs a mud or paper nest identical to those its species have been building for countless millenia. This task completed, the wasp flies off in search of prey with which to stock its larder —not just any insect, but usually of the same spider or caterpillar species its ancestors sought. After inserting its stinger in the precise spot to paralyze but not kill its prey, the wasp carries its victim back to the nest and secures it inside. Laying a single egg on the immobilized insect, it seals the chamber.

The digger wasp goes a step further. After she has immobilized the live insect and dragged it to the hole, she lays a solitary egg and closes the mouth of the den with soil, tamping it firm with a pebble.

Some social wasps, like the paper wasp, build elaborate nests of papier-mache-like materials. Collecting fiber from rotten wood, plant stems, or even man-made paper or cardboard, the female wasp chews the materials, mixing them with a salivary secretion to produce a pulpy mass which dries firm and gray.

Perhaps the best known of the social insects and the real workhorses of pollination are the honeybees. Eons of genetic adaptation have Paper wasp mixes salivary secretion with chewed fibers to build its nest molded the bees and the flowers into symbiontic forms that benefit each other. Densely-haired bodies of the insects efficiently convey pollen from flower to flower while fragrant, colorful blossoms, sometimes imitating female insects, are attractive lures to the nectar-seeking bees.

JULY 1971 21

Foremost among all insect pollinators are the honeybees, since their whole economy is based solely upon collection of nectar and pollen. The importance of the honeybee as a pollinator has been somewhat exaggerated, though. It has been claimed that were it not for honeybees, no flowers would bloom, no fruits would produce, and numerous familiar plants wTould disappear. Such is not the case. When the first European settlers arrived in North America they found an abundance of fruits, flowers, and vegetables, but no honeybees. They were not brought to the New World until the 17th Century. Before that time, an abundance of native insects handled pollination tasks quite well.

It is a common fallacy concerning beehive

organization that each insect is a specialist —

worker, nurse, forager, or other —but this has

not been proven. Each bee passes through a

series of jobs within the hive; nurse —bringing

JULY 1971

23

honey and pollen from storage areas to feed

the queen; comb worker — molding wax into

the complex hexagonal units; comb cleaners

and guards; and finally, at about three weeks

of age, the bee enters old age, with the last duty

the most hazardous — foraging outside the hive.

honey and pollen from storage areas to feed

the queen; comb worker — molding wax into

the complex hexagonal units; comb cleaners

and guards; and finally, at about three weeks

of age, the bee enters old age, with the last duty

the most hazardous — foraging outside the hive.

Locating nectar sources and relaying the information to other workers in the comb is an interesting procedure as well as an indication of their behavior development. If a nectar source is within 100 yards of the hive, the returning scout enters the hive, runs through the combs, disgorges a drop of nectar, and begins its dance. The "round dance", as entomologists have labeled it, is performed in a circular pattern, telling other foraging bees that the source is close. The scent of pollen on the hind legs of the scout tells others what type of plant to seek out.

If the nectar source is more than 100 yards from the hive, more detailed instructions are given by the scout, indicating both direction and distance. This dance assumes a figure-eight form. The speed of the dance plus the rate of abdomen wagging suggest the distance. Positioning of the figure eight points in the direction of the flowers. The "tail-wagging dance", as it is called, is one of the insect world's most fascinating and elaborate displays.

Higher on the social scale are the bumblebees. Only the queen survives the winter months. Emerging in the spring, she seeks out an abandoned rodent burrow or similar underground structure, exuding a wax with which she constructs a honey pot. After filling the honey pot with nectar, the queen lays one egg on it and repeats the procedure with numerous other structures. Finally, she sits on the eggs and later on the larvae, protecting them from the cold. If an experimenter removes the eggs, the queen utilizes any nearby object to fulfill her genetically programmed need to brood, sitting on a pebble or other handy substitute. The first bumblebee brood develops into a handful of diminutive worker bees which assist the queen in future egg laying. Bumblebee colonies never attain the size of bustling honeybee cities, although a thriving colony may have from one to two thousand individuals by summer's end.

Solitary or social, parasites or pollinators, harmful or harmless, bees and wasps are a part of our past, our present, and our future. Stinging marauding youngsters who threaten their homes, pollinating our field and orchard crops, keeping other insect populations in check, or providing us with nature's own swTeetener, they are a necessary part of the overall scheme of things. With life patterns rivaling man's own in complexity, they serve as a constant source of wonderment and a necessary link in the complex chain of life.

THE END

PLANNED PLANTHOOD

Nebraska's landscape is being changed. By horticultural manipulation, new varieties of trees and shrubs are showing up in healthy numbers by Jon FarrarTREELESS NEBRASKA is coming of age. Woodland green is claiming the grasslands which sweeping prairie fires maintained for countless ages. Poplars, willows, and junipers lead the advance. An irregular legion supports their forays. Pecans, persimmons, chestnuts, baldcypresses, creeping and weeping junipers, and other strange forms bolster their conquering ranks.

Aiding and abetting this purge of grassland dominance, the Resource Services Division of the Game and Parks Commission has lent comfort to the invading force. Producing thousands of trees and distributing them throughout the state, their role in this conspiracy to green up Nebraska was initiated in the spring of 1969.

With the creation of the Interstate Chain of Lakes came the need for development of recreational areas near them. Designed to furnish Nebraska's pleasure seekers with shelter from the blistering summer sun and prevalent winds, as well as to please the eye, these plantings are enlarged seasonally. While many of the lake areas are the responsibility of the Resource Services Division of the Commission, others are handled by the Parks Division and the Department of Roads.

What sets Resource Services' programs apart from other contemporary tree-planting projects or those before it? For a starter, they have launched their own plant-propagation operation-complete with greenhouse, nursery, and an experienced horticulturist. If that were not enough, they have experimented with and used species usually not thought of as Nebraska plants - those which many doubted could survive the rigors of winter. Mutant forms of native plants have been selected for desired characteristics or ornamental value as well as hardiness in our climatic area. A program to use dense clumps of native wildflowers on appropriate sites rounds out the division's "new thinking" on landscaping of public areas.

And so, the State of Nebraska, in a small way, has entered the nursery business. Designed in the beginning to handle commercial nursery stock and to propagate plant materials not available through regular sources or available at a cost prohibitive to the state, the project has expanded in the last three years to new horizons in horticulture for Nebraska.

Designed to unveil the policy of the Game and Parks Commission, herbaceous and woody plantings on the Interstate - and later on other state areas -were initiated. Much of the Commission's philosophy has solidified around the ideas of Hans Burchardt. While still relatively (Continued on page 63)

JULY 1971 27

the girls went canoeing

Women's Lib strikes one blow for equality as four females take on a Platte River float trip 28 NEBRASKAland by Faye MusilWE WERE FLOATING quietly down the Platte River, feeling agile as Indians, when suddenly I saw a barbed-wire fence coming up fast. Almost instinctively, I stuck out a hand to grab it, hoping to keep us away from the barbs. But the stern of the canoe, caught in the current, swung around and slammed into the wire.

Rusty strands grated over the side of the boat and were about to either cut Nan and me in half or push us over, swamping the canoe. I bailed out, wondering what Nan said as I went over the side. When I came up, dripping and grabbing for the errant canoe, I found her doing the same. We discovered there was no danger of losing our transportation. The loss of our combined weight raised our canoe higher in the water and it was hung up on the fence. But a paddle was floating merrily downstream, seemingly elated at its early escape.

The whole episode began one busy afternoon in the Game and Parks Commission's Information and Tourism office. I was answering some correspondence when one of our artists, Michele Angle, came by and asked—half in jest and half seriously, if I would like to do a canoeing story for NEBRASKAland.

A male canoeing story had bombed for lack of subjects who could get away from their jobs long enough, so the assigned writer was looking for alternatives. He had suggested off-handedly an all-girl trip, and Michele, Nan Lee, and I had agreed it was a great idea.

Nan, NEBRASKAland Magazine's secretary, had some canoeing and camping experience and assured us there was nothing to canoeing. I had been camping time after time with my parents before my high school graduation, so I asserted there was nothing to it.

So, battle lines were drawn. We needed photo illustration as well as art, which Michele planned to do. But NEBRASKAland has no female photographers, and the men in the office began telling the photographers what a trip with four women would be like.

To be fair, the men weren't against women in the field. They were against inexperienced women in the field, and comments ran from, "I sure wouldn't want to babysit four girls on this trip," to "I can see the headlines now, Tour Women Drown While Photographer Looks On,'" to "I see a mini-fiasco in the making."

JULY 1971 29

The guys were ready with advice, too. "You're doing too much planning," and "You'd better get organized and prepare for any eventuality."

There was considerable kidding, but with the fellows' expert advice and chiding admonitions, we laid our plans. We had one experienced canoeist, Nan, and one girl with life-saving training, me. Michele was game to learn it all. We decided to take two canoes, so we needed another experienced canoeist to man (woman) the stern of the second canoe. Michele provided the help from among her acquaintances — Rose Chamberlain from Storm Lake, Iowa, who had spent a large portion of her life in and on the water.

Living in Lincoln with her husband of eight months, and working for the University of Nebraska, she was willing to break her routine. Her husband, Dave, didn't protest too loudly. I was to get a two-night break from the kids, the cooking, and the dishes, and Michele and Nan were going to get three days with nature instead of paper.

Bob Grier was assigned as our photographer, and he needed someone to paddle his canoe while he snapped pictures. With a little encouragement, my husband, Marv, agreed to help us out. We were to be out three days. Bob and Marv would go the first day, then leave after photos were taken in camp that night. Bob was then to pick us up at the Overton bridge on the third day and restage any excitement for illustration.

So we went our separate ways Saturday, April 24, gathering supplies and personal gear. Marv and I drove to Blue Hill to leave our two youngsters with my parents during the three-day excursion. We were to meet the two cars with the three canoes at Grand Island at 8 a.m. the next day.

At 9:30 a.m. they finally pulled in with some vague explanation about forgetting daylight savings time. Marv and I left our car at Mormon Island State Wayside Area, and climbed in with the troops. We proceeded to the Interstate 80 exit at Brady.

We stopped at Dale Fattig's place where we had arranged to get into the river. Off we went under overcast skies, thinking of some of the sunlit, springlike days we had seen the week before. Surely the haze would burn off. We unloaded the canoes, carried them dowm to the riverside, and stowed what seemed to be tons of gear. Finally, we were ready to shove off.

Nan, with bare feet and rolled-up blue jeans, was the official shover-off. She was the only one to get her feet wet —at the start. Nan and I took the lead canoe, with me in the bow. Michele, with Rose in the stern, followed, and Bob and Marv brought up the rear. But before we had traversed our first mile, we met up with that first fence.

After the impact and dive for safety, I made a futile reach for the retreating paddle, ran a few slow steps in the thigh-deep water, then gave up, hoping it would snag farther on. Anyway, we had extra paddles. Nan and I, already drenched, eased our canoe under the fence, then helped everyone else under —with no more near-drownings.

From there on, things went swimmingly. There was about one fence per mile for the remaining seven miles we covered along the south channel. We reached the diversion dam below Brady about 3 p.m. Most of our travel time was spent looking for and struggling under fences. Meanwhile, we had probably passed the wildest stretch. The river was almost completely screened by trees and the channel was relatively narrow. But the stream was slow-moving and comfortable for beginners. We needed that learning stretch to initiate Michele, Marv, Bob, and me.

As I learned to paddle, I thought about office discussions and warnings that the part of the Platte we planned to attack might be dry —as it is through large portions of the summer.

This slow channel was part of an early water diversion, similar to a Mid-State project now planned by the Bureau of Reclamation for an area farther downstream. The channel was narrow here, with most of the water six inches deep or less. It was an area where migratory birds are scarce — even during their most active season. The Platte, once a great corridor, a stopping place for migratory waterfowl, is gradually being civilized. Diversion of water in 1941 made the section we were floating very different from the rest of the river. The planned project would change the historic face of another great stretch of the river.

Once an almost insurmountable boundary across (Continued on page 58)

JULY 1971 31

VALLEY OF THE MISTS

by Alice Graham Ashland Ashland hollow is haunted, or so some people say, by the tortured spirits of those who paid for deedMAN HAS OCCUPIED the lower Platte River Valley for centuries. The region is one of rich soils, numerous pure-water springs, and many rivulets and creeks. This vast, rich valley was the domain of the Otoes before white men came to Nebraska Territory.

U.S. Highway 6 runs across the heart of this broad valley. As a motorist approaches the town of Ashland, driving from Lincoln to Omaha on U.S. 6, he sees a small and picturesque U-shaped valley to the right. Laced with young willows and rimmed by a winding country road, a small, spring-fed stream meanders gently through the peaceful vale to join Salt Creek farther on. This scenic spot has intriguing legends woven into its history. In 1967, it was the place where a UFO was reportedly sighted by Herb Schirmer, an Ashland policeman.

But this valley of the mists had special significance for both Indian tribesmen of centuries past and white men who traveled overland on the old Oxbow Trail about a hundred years ago. While Indians had one explanation for the rising mists in the small valley, overland freighters who came to the rocky ford on Salt Creek dubbed the vale "Ghost Hollow".

The Otoes were convinced that some supernatural power prevailed in the mists. On the crown of the hills surrounding the U-shaped valley, the Indians held ceremonial dances and rites to petition the Great Spirit.

Fog rises from the spring-fed rivulets that converge on the valley floor. On a cool evening, particularly in the fall, these wisps of mist drift across the valley through the willows and cottonwoods.

When the Indians held a ceremonial dance in preparation for a buffalo hunt, they believed the Great Spirit was pleased with their sacrifices if the mists of the valley rose into the sky. But if the mists scattered low over the valley floor or clung to the nearby knolls, the Indians believed the Great Spirit was unhappy with them. Then the red men often called off the hunt until a new ritual dance could be held at some: later, more promising date.

Other ritualistic dances were staged on the sacred ceremonial hills, too. Any unusual happening, planned tribal project, or change of season, called for an Indian powwow. If disaster or disease came to the villages, these, too, called for ritualistic dances to dispel the misfortune. Some early missionaries—those who came in 1834 and 1844—believed that under extreme provocation the Indians would make human sacrifices to have the curse of smallpox or hunger lifted from their people.

White travelers and overland freighters were indifferent to the superstitions of the Indians and used the springs to water horses and oxen before crossing Salt Creek on their many westward journeys along the Oxbow Trail.

A few years before the Civil War, during the days of massive overland freighting, a number of town sites were staked out near the rocky crossing of Salt Creek, which had come to be known as Salina Ford (now Ashland). Two of those old town companies put forth vigorous campaigns to have their sites become the main city at the rocky crossing. Salina promoters in the west part of Ashland, near 22nd and Birch streets, bragged about their beautiful location overlooking the wide Salt Valley. Parallel City, near the Rodeo Grounds, took its name from the land surveyors' correction line that is now the county line. It was advertised 110 years ago that it would be the metropolitan area of the lower Platte Valley. In advertising why their town should be chosen over other townsites, Parallel City promoters told a gruesome story about Salina. Freighters took the promoters' story and retold it with relish.

It seems that in earlier days, four white men rode into an Indian camp near Salt Creek. The Indian braves were away on a Hunt, so the white men assaulted the women in the village. When the Indian braves returned to their village and found the havoc wrought by the white men, they were outraged. The Indians tracked and soon caught the four horsemen. The white men were taken to the hill near the village overlooking the valley. There they were tortured and burned to death over a great bonfire, but not before their screams of agony filled the valley.

Promoters of the Parallel City site said the mists rising from the springs were the ghosts of the burned men haunting the valley because they had never been buried. The whine of the wind in the knolls and through the treetops were the ghosts' moans of agony. Around the evening campfire, the old bullwhackers and wagonmen told and retold the gruesome yarn, pointing out the natural phenomena of the countryside, especially for the benefit of tenderfeet who happened to be along. The freighters took advantage of every rising wisp of fog during quiet evenings to imagine they saw the ghosts.

The story died after a while because the freighters moved on, and the many settlers who came after the Civil War had no interest in haunted valleys or moaning trees. Even now, though, if a traveler looks to the rising moon on a still evening and sees ghost-like mist beckoning in the'pale light, he may ponder the campfire legend of yesteryear. The eerie moonlight reflects from glossy cottonwood leaves, and the chatter of the trees amplifies the sounds of night. A century later, the whine of tires on pavement and the glowing movement of headlights adds another dimension to the mists of Ghost Hollow.

THE END 32 NEBRASKAland

IN THE MIDDLE OF EVERYTHING

Westward America grew by leaps and bounds. From earliest days, Nebraska was destined to become a nation's heartland 34 NEBRASKAlandNOT SO LONG ago, Nebraska was labeled as being in the middle of nowhere. Quite to the contrary, NEBRASKAland is smack in the middle of everywhere. It has always been that way and will always remain.

"A desert!" That's what Captain John C. Fremont, American explorer, called Nebraska. Clearly, he was a man of little vision, for he could see neither the beauty of this land nor its tremendous potential. Here, in the heartland of America — in the middle of it all —man was destined to establish the beginning of the real West across the bulling Missouri River.

Skies drenched in blue and prairies alive with tall, dancing grasses greeted those who first ventured beyond the Missouri River. But, the white man was a Johnny-come-lately in discovering the magic of NEBRASKAland. Indians of many tribes, wild and free as the land itself, called Nebraska home long before. Millions of shaggy buffalo roamed the plains and fur-bearing critters filled the rivers and streams.

Trappers, strangers to fear, first

opened the land. It was big country,

JULY 1971

35

The westward incursion of America grew by leaps and bounds. By the thousands, settlers pushed up the twisting Platte River toward the fabled land of the setting sun. But many forgot the Pacific's siren call. These visionaries saw a future on the prairie, and planted their roots. This land, right in the heart of America, soon became their land and their children's heritage. Thus the settlement of the West began. The Wild Bill Hickoks, the Buffalo Bills, the George Armstrong Custers, and the Red Clouds stepped from reality into legend. The red man and the soldier, the trapper and the buffalo hunter, the sodbuster and the cattle baron all played important roles.

The smoke-belching iron horse of the Union Pacific rumbled across the frontier, linking the nation with the first transcontinental railroad. And, while the clickety-clack of wheels on rails echoed over the plains, the automobile was on the drawing boards. Roisterous river towns, lonesome frontier forts, and wild and woolly ends-o'-track came and went, each crucial to the total development of NEBRASKAland.

Today, huge herds of cattle bred to refinement roam the prairie beside superhighways that lace the lush, green countryside. Concrete ribbons have replaced the ruts of the Oregon Trail, and sleek convertibles now cruise the paths once hardened by Conestogas.

JULY1971 37

As mankind pioneered the heavens, supersonic jets were destined to blaze trails of peace across Nebraska skies. The mighty Strategic Air Command, nucleus of the nation's defense system, fulfilled that destiny when it was headquartered in the middle of America.

Fishing means year-round sport here. It means sun-tanned boys with willow poles and squirming worms. It means the most modern in casting equipment. And, for each angler it means fighting lunkers and generous limits. Wetting a line in NEBRASKAland means action for young and old alike.

NEBRASKAland hunting is among the best. Billed the nation's "Mixed-Bag Capital", there's action aplenty from the wily ringneck to the elusive, pronghorn antelope. Nebraska is truly a sportsman's delightful paradise.

In the middle of nowhere? Not on your tintype! The facts bear witness. It was here where man arrived with faith and courage and built a state that became the envy of many. With strong hands and determined spirit, he carved a niche in the center of a continent, for few places in this mammoth nation outdo the all-around greatness of NEBRASKAland. From coast to coast and border to border, Nebraska sits astride America. This is our land... a proud and beautiful land...our NEBRASKAland... in the middle of everywhere.

THE END 42 NEBRASKAland

Egg-sack Trout

by Steve Olson When a migration run is on in Platte feeder streams, rainbows aren't something the angler can take lightlyAS I FLIPPED the bail of my new spinning reel, I thought to myself: "At least it's new line." A second later, the splash of my sack of trout eggs smacking the surface of Pumpkin Creek was barely audible over the murmur of water. An early morning sun turned steam to a golden mist as it rose from the stream. Silhouetted some 50 yards downstream, my informal fishing guide, Al Robertson of Bridgeport, worked a pool.

It was spring and good to be standing at the water's edge in the morning stillness. Early April had not yet brought green to the Sand Hills, but a certain softness in the breeze and the quacking of mallards in a lower pool testified to the season.

All seemed right, but I couldn't help remembering Al's comment: "Six-pound-test line may be alright, but I use heavier. When I latch on to one of those big ones I don't want to lose him."

All my previous trout-fishing experience had been in the high mountain streams of Utah and Idaho where two-pound fish were considered trophies. The thought of tying into a big spawner on light tackle had me a bit worried, but I was ready. Six-pound-test line was all I had and I figured it would have to suffice.

"I fish Pumpkin quite a lot because it's close," Al had explained on the drive from his home.

At the water's edge, I rigged quickly. A No. 5 hook baited with a sack of trout eggs and a heavy split shot about a foot up the line put me in business.

I could feel the split shot bumping bottom after I cast to the riffle at the head of the pool and let the bait drift down slowly. As I fished, I studied Al. He approached each small pool carefully, not allowing his shadow to fall on the water. Standing well back from the stream's edge, he dropped the egg sack near the top of the pool and followed it down. He worked carefully but quickly, allowing about a dozen casts per pool before moving on to the next. Within minutes, he was out of sight around a bend. Rather than fish the same water, I headed upstream. An hour later Al reappeared.

"They're just not in here this morning," he said. "Let's drive over and try Nine Mile."

As we headed north, Al explained it is usually possible to spot big spawning trout if they are sunning in a stream. When the (Continued on page 50)

JULY 1971 45

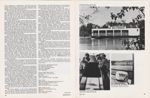

BOATS FOR HIRE

by Norm Hellmers Pleasure craft of all sizes and varieties ply Nebraska's waterways for summer fun afloatBOATS, BOATS, and more boats. Nebraska, often mistakenly stereotyped as a landlubber's paradise, has boats and water on which to use them to spare. Boatmen can enjoy their particular brand of fun and excitement on much of the state's 11,000 miles of streams and rivers and 3,300 lakes.

But you don't have to own a boat to enjoy Nebraska's watery bounty. Exciting excursion trips are available on several unusual vessels which ply the Missouri River. Those with a yen to captain a boat themselves can choose from a number of craft of all shapes and sizes that may be rented throughout the state.

From rowboats to houseboats, the amateur skipper can rent a vessel to match his dreams. At many city parks, the would-be boatman can latch onto canoes, rowboats, small sailboats, and paddleboats. Larger, more-powerful boats are available for hire at many of the state's lakes and impoundments.

But not everybody likes the responsibility of piloting a boat, no matter what the size. For these people, there are other options. An assortment of pleasure boats ply Nebraska's waterways, offering a unique variety of aquatic adventure.

One boat which doesn't travel far in terms of distance, but transports passengers to the inaccessible, submerged world, is the glass-bottom boat at the Fort Kearney Museum. This unusual 24-foot, battery-operated vessel takes regular voyages across the 3 1/2-acre, spring-fed lake located behind the museum at the Kearney interchange on Interstate 80. Sparkling, clear water permits easy viewing of the lake's diversity of underwater life.

Animals which inhabit the lake's depths carry on their lives without interruption. Trout laze in the cool shadows, catfish follow along beneath the quietly cruising craft, and bluegill seek morsels from the slender reeds of aquatic vegetation. Myriad plants and animals open their homes for inspection. Turtles, crayfish, and even snails carry on their normal activities, all unaware of man's silent intrusion into their domain.

A half-hour ride in this, the only glass-bottom boat in the Midwest, is like a flight through space. Passengers can look down on the varied terrain and see miniature mountains and valleys loom beneath the glass. Only rising air bubbles betray the watery environment. Travelers take a trip to nowhere, except to the natural world of a lake, a world often overlooked.

A boat which does go somewhere, but in a style little seen in this modern day, is one of the last ferries on the Missouri River, the side-wheeled Sally Ann. This storied vestige of yesteryear makes numerous daily crossings of the river from just east of Niobrara to South Dakota Highway 37 on the other side, a distance of IV2 miles.

Even if visitors don't have a reason for crossing the river, many go along just for the experience of riding with their cars on the perky little barge. The Sally Ann operates on demand, not by a schedule. If you want to cross, you hoist a small red flag alongside the dock. Out comes the operator, who supervises the loading, climbs the stairs to the small pilothouse, and heads the 70-foot ferry toward the opposite dock.

Operating from 8 a.m. till 8 p.m. between April 1 and November 1, the Sally Ann provides a needed service for people in the area, as well as serving as a tourist attraction for visitors to Lewis and Clark land. Since the nearest bridge is almost 40 miles away atop Gavins Point Dam, the ferry has proven its worth many

46 NEBRASkAland

times, especially in emergencies. The Sally Ann has carried ambulances, buses, and a great assortment of trucks. It has helped rush expectant mothers to the hospital and has carried hearses, too.

For area natives, the neat little boat is an accepted part of everyday life, but for visitors it becomes much more. Despite its small size and the brevity of its journey, the Sally Ann serves as a reminder that at one time this was the only way to cross the Big Muddy. A ticket to ride on her small deck is a chance to relive some of the excitement that always accompanied any trip on this mighty river.

Farther down the river at Ponca State Park, other boats head out into the Missouri's strong current. Stardust River Cruises, Inc., operating out of Ponca and South Sioux City, offer several different types of Missouri River excursions. Now in its third season of operation, the Ponca Chief, a 19-foot, 9-passenger speed hull, gives its riders a 30-minute zip on one of the finest stretches of the Missouri. Stardust's other boat is an all-new excursion vessel, the Sioux Chief. This luxurious 49-passenger boat makes runs from both Ponca State Park and South Sioux City.

Trips from the state park at Ponca are sight-seeing cruises and all are fully narrated. Factual commentary includes notes about the surrounding country, the area's history, and information about the fascinating Missouri. Occasionally, wildlife along the mainstream gives lucky passengers a special thrill, a reminder of the time when all of the Missouri was wild and free.

Excursions from South Sioux City are also mostly the sight-seeing variety, but, of course, they feature more of man's creations along the river. The facilities of the 50-foot Sioux Chief include stereo music, three observation decks, restrooms, and plenty of room to roam. There are also special 22-mile Sunday cruises which originate at South Sioux City and end at Ponca; a similar trip, billed a "dinner cruise", goes in the other direction. Either of the Stardust boats may be hired for private charters. The deck of the spacious Sioux Chief has been the unique setting for floating occasions of all sorts —family parties, club outings, and business meetings.

All Stardust cruises emphasize the natural beauty of the Missouri River and offer a chance for escape from the everyday world. The river isn't quite the way Lewis and Clark knew it, but the chance for individuals to discover themselves remains.

Decorated to resemble a 19th-century steamboat, the River Belle calls Omaha its home port. Operated by Missouri River Passenger Excursions, Inc., the River Belle offers complete excursion and entertainment facilities. The little stern-wheeler is available for charter service, but there are also regularly scheduled trips open to the public. If desired, dance music, bar facilities, tables, and catered dinners can be included.

A cruise on the River Belle gives passengers a close look at sights that were unknown in the days of the original steamboats. Massive bridges which now span the wide Missouri, Omaha's soaring skyline, and the towboats pushing strings of barges can be viewed close up in a way possible only from a boat on the river.

Highlighting the River Belle's season is a special excursion from Sioux City to Omaha. It is an all-day trip, and covers 116 miles of Nebraska's scenic river country.

The latest addition to the river's pleasure-boat fleet is also the largest excursion boat on the Missouri. The Belle of Brownville, now in its second year of operation, boasts a length of 65 feet. Capable of carrying 300 passengers, the Belle brings back to the Missouri a style of travel that has been unknown since Brownville's heyday more than half a century ago.

The third boat to bear the name, the Belle of Brownville was originally an excursion boat at Greenville, Mississippi and Houston, Texas. Last year, her purchasers, Brownville Development, Inc., brought her up the Mississippi and Missouri rivers from Texas and immediately began a schedule of pleasure excursions.

This spring, the Belle was completely refurbished. Now looking like a specter from the pages of a 19th-century photo album, the broad craft works her way up and down the river, pushed not by a traditional paddle wheel, but by powerful diesel engines.

With the bottom deck completely enclosed, the Belle provides comfort despite inclement weather. Other facilities include restrooms, a refreshment bar, and, if desired, a dance band. The Belle has already been chartered this season for fraternity and sorority parties, high school proms, and dinners and dances for civic and social clubs.

Regularly scheduled excursions are open to the public every Sunday afternoon, and romantic moonlight cruises are run on Saturday nights during July and August. Special dinner cruises are planned during the July and August theater season. Theatergoers will enjoy a pleasant meal aboard the Belle and then conclude the evening's excitement with the theater performance.

Sunday afternoon cruises are narrated, and river sightseers are treated to views of river landmarks, including the new Cooper Nuclear Station. River history is also given. Both young and old with imagination can easily feature themselves as river pilots or belles of the ball.

The Belle of Brownville is a link with the past, but all of Nebraska's pleasure boats are here to enjoy today. From skiffs to scows, the variety of boats available to the state's natives and tourists is unlimited. From city-park dinghies to the majesty of the Belle of Brownville plowing upriver, NEBRASKAland has much to offer afloat.

Editor's Note: Further information about Nebraska's major pleasure boats, including printed schedules of runs and rates, can be obtained from, operators listed below:

Fort Kearney glass-bottom boat Fort Kearney Museum 311 South Central Avenue Kearney, NE 68847 308-236-8951 Ponca Chief, Sioux Chief Stardust River Cruises, Inc. Box 224 Ponca, NE 68770 402-755-2511 or 402-755-2266 River Belle Missouri River Passenger Excursions, Inc. Box 14181 West Omaha Station Omaha, NE 68114 402-345-6103 or 402-345-2433 Belle of Brownville Brownville Development, Inc. Box 96 Brownville, NE 68321 402 - 825-6441 THE END 48 NEBRASKAland

EGG-SACK TROUT

(Continued from page 45)water is clear, you'll find them lying in their spawning beds or in deep pools. If the water is murky, you have to watch shallow riffles where you can see them running between pools.

"That's half the fun of this kind of fishing," he said. "You never know whether you'll find an empty stream or one chockfull of big trout. But, I'm afraid the run is about over."

I knew what Al was talking about, having checked with Game Commission fisheries biologists before leaving Lincoln. The number of trout in the streams which feed into the North Platte River depends on the spawning migration from Lake McConaughy. Trout instinctively return to spawn in the stream where they were hatched. After spawning, the fish return to Lake Mac. Young fish remain in the stream for about a year, then they also move down to the lake. Heavy migrations run in three-year cycles according to the age classes of the fish.

"Next year should be good," biologists had reported, "but the best you can hope for now is to catch the tail end of a mediocre run."

I couldn't say I hadn't been warned, but the fishing bug bit hard and the lakes around Lincoln were still too cold to produce. So, I was optimistic as we approached Nine Mile.

Our first fish came about an hour later. Several pools near the mouth of the stream were unproductive and we were working a deep hole below a constriction where a culvert crossed the water. Al's line suddenly went taut as a 12-inch rainbow broke water, thrashed momentarily, then dove deep. Seconds later, Al wet his hand and released the fish, admonishing it to grow up and put on a little weight.

"Maybe that's what we needed to get started," Al said as he rebaited with a fresh egg sack.

In the next five minutes, he hooked and released a sucker and one more small trout.

"I guess they don't like my new outfit," I commented as Al rebaited.

"These little ones aren't worth messing with," Al kidded. "Save it for a good one.

Moss choked the fast water between pilings at the head of the pool. Fully expecting a snag, I dropped the eggs into the current and waited. Suddenly, I felt a strike and set the hook. Nothing happened and I mentally confirmed my concern about a snag. Then the "snag" shot downstream and a big rainbow catapulted from the water directly in front of me.

"I've got a good one!" I whooped.

"Don't try to horse him," Al warned as he scrambled down the bank with the landing net.

For a few seconds I felt a complete loss of control. The fish apparently didn't know there was a drag on my reel. Ripping off line, he went deep, then jumped again at the far edge of the pool.

"Let him run," Al cautioned. "Wear him out."

"I don't have much choice," I answered, "He's going pretty much where he wants." After several passes the fish tired "And what, may I ask, was wrong with the old sign?" quickly, and soon Al was slipping the net under it.

"A nice big female," he said. "Should go about four pounds."

Figuring I would never find out without asking, I inquired how he could immediately tell it was a female. He explained that the females have a smooth rounded nose. Males, or "jacks" as he called them, develop a protruding, hooked, lower jaw during the spawning run.

Al, who seemed just as happy about the fish as I was, beamed, "I guess that six-pound test is good enough."

"I don't know," I replied. "If that's what a four pounder can do, I'm not so sure I want to tie into one of those six or seven pounders you've been talking about."

"But I'll bet you'd give it a try, wouldn't you?" he quipped with a quick smile.

In the next hour we worked on up Nine Mile with no luck, and finally decided to take a break for lunch. As we devoured our sandwiches I asked about the sacks of trout eggs.

"I put my own together," Al replied. "Some fellows use material from a nylon stocking, but I prefer a good grade of cheesecloth. I cut it into 21/2-inch squares, drop in about a teaspoonful of eggs, tie it off with heavy thread, and then trim the excess material. The secret is to get the sacks smooth and circular, about an inch in diameter."

He went on to explain that he made up a number of sacks at one time and froze them in small, glass jars. When he plans to fish, he simply takes out a jar of eggs the night before and lets them thaw.

"I've tried worms, minnows, and lures," Al added, "but, during the spawning run I've always had my best luck with eggs. Years back, before anyone thought of sacking, some fishermen used tiny wire hooks and tried to thread on two or three eggs. Sacks sure have simplified things."

We spent the afternoon fishing both Stuckenhole and Red Willow creeks but couldn't raise a fish.

"They just weren't running today," Al said as we drove back to Bridgeport, "but maybe tomorrow...."

The next day dawned sunny and warm, and as we headed back to Pumpkin Creek I asked Al about access to streams in the area.

"Most of them are on private land, but the landowners are pretty good about letting fishermen in if they ask permission. I've been fishing these streams for about 20 years, so I don't have any problem."

Minutes after we arrived at the creek we knew the trout were there. Al pointed out several new spawning beds — gravel-bottomed depressions about four feet long and two feet wide — in the fast-water portions of the stream.

In the next two hours we spotted more beds and saw several fish, but none seemed interested in biting. Finally, Al located three fish lying in slow water 50 NEBRASKAland about three feet from the bank. Time after time, he worked the egg sack past the fish.

"Sometimes you just have to keep running it by them until they get mad enough to bite," he prompted as I watched in anticipation.

The water was murky and we finally began to suspect the fish were carp. Then a 3Vi-pound rainbow changed our minds. Al's rod came alive as the fish danced across the surface and then dove. Working the fish expertly, Al eased the trout toward shore and I slid the net under it.

"A pretty fair jack," he commented as I studied the fish's hooked jaw.

Trout normally die quickly after being caught, but as an experiment I had brought along a styrofoam ice chest and a small, battery-operated air pump to see if I could keep a fish alive. After placing Al's trout in the cooler and turning on the pump, we went back to fishing.

About an hour later, while working my egg sack along an undercut bank, I felt a strike. Hoping for the best, I set the hook firmly and unceremoniously dumped a Impounder out onto the bank. I was considering returning it to the water when I noticed its aluminum jaw tag, so I decided to add it to the cooler. A later check revealed that the fish had been tagged at the Game Commission's Lewellen fish trap on November 12 the previous year.

Al had been fishing the same water where he caught the jack. Deciding to take a breather, I sat on the bank and watched as he repeatedly flipped the egg sack upstream, then let it drift down. The sun was warm and I lay back to watch the clouds roll by. A sudden shout startled me. Sitting upright I saw a huge trout jump in midstream, and then saw Al's line go limp.

"Now that was a good trout," Al smiled as he rebaited. Later in the afternoon we found out just how good it probably was. Another fisherman, working the same water, landed a six-pound female; very likely the same fish.

For the remainder of the day, action was slow. Late in the afternoon I hooked a large fish only to see it jump twice and then disappear for good. Reluctantly, I decided it was time to head back to Lincoln. As we neared the pickup, I noticed that the lid was off the cooler. I had placed the chest at the stream's edge and when we arrived we discovered it onty contained one fish —the small, tagged female I had caught.

"Now I've really got a story about the one that got away," Al said with a chuckle. Further inspection showed that the batteries in the air pump had run down and we speculated that the bigger trout had made one last-ditch lunge and flopped out. A couple of wiggles and he was back in the stream.

"You'll have to come back in October," Al said as I prepared to leave. "The fishing is really good then."

He didn't have to worry. He had given me a taste of the action.

THE END See what made America Made ...More than a Century of Authentic History 12 Miles South of I80 at MINDEN, NEBR. One of top 20 U.S. attractions... more than 30,000 items in 22 buildings, arranged in order of development since 1830. Antique autos; farm implements; locomotives; airplanes; fine china; art; hobby collections; much, much more. Buildings include Indian Stockade; Pony Express Station; Sod House; People's Store; Pioneer Railroad Dept. Adults $1.50; minors 6 to 16, 50 cents; tots free. Open 8 a.m. to sundown every day. Motel, restaurant, campgrounds. Here You Can See America's Progress in The Making SEND COUPON TODAY PIONEER VILLAGE, Minden, Nebr. 68959 Please send free picture folder full color picture folder Name. Address. City State. Zip. COLLINS on Beautiful Johnson Lake . . . Lakefronf cabins - Fishing tackle - Boats & motors - Free boat ramp • Fishing • Modern trailer court - Swimming • Cate and ice - Boating & skiing - Gas and oil - 9 hole golf course just around the corner - Live and frozen bait. WRITE FOR FREE BROCHURE or phone reservations 785-2298 Elwood, Nebraska Fishermen and Hunters Enjoy the Harlan County Reservoir Stay at HARROW LODGED Box 606 ALMA, NEBRASKA 68920 Telephone 928-2167 HIGHWAYS 183-383 and 136 Air-Conditioned, TV, Telephones One and Two-Room Units Cafe V2 Block Away Laundromat Nearby Kin's Idi rive-inn At Kip's the quality food and low prices you paid in 1968 are still the same today. We continue to serve the finest in seafoods, chicken, sandwichesand soft drinks. One minute from Interstate 80 Highway 47 to Gothenburg DON'T MISS IT! • Family Stage Show-all new cast • Steaks, Dinners, Luncheons, and Buffaloburgers • Redeye, Sarsapariila, and Better Beer on Tap Hwy. 30 to 0GALLALA, 1 mile from 1-80 Interchange JULY 1971 51

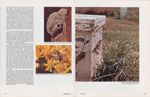

NOTES ON NEBRASKA FLORA. . . LATE GOLDENROD

by Frank Deatrich District Resource Services Supervisor Indians called Nebraska's state flower Zha-sage-zi. Early pioneers used the dried leaves as a tea, salt substitute, and for relief from rheumatismAS THE CROCUS is the sign of , coming spring, so the goldenrod predicts autumn's arrival. With bright, generous blossom, its dense golden flowers take on many forms: cascading fountains, long, wavy plumes, or sword-like spikes. Like sparkling gems, they adorn late summer's fading greens.

More than 120 species of goldenrod are indigenous to the continental United States. Nebraska alone hosts a dozen or more. Even novice botanists can tell a goldenrod from other wildflowers, but to distinguish the various species is quite another matter. Their numerous similarities and the perplexing array of hybrids bewilder even trained taxonomists.

The botanical name of the late goldenrod, Nebraska's state flower, is Solidago gigantea serotina. A literal interpretation of this Latin version is "I make whole", meaning to heal, an allusion to the plant's reputed healing qualities. Each of Nebraska's 15 species has its own characteristic form, each varying from our state flower in different ways. The tall, erect plumes of the late, Canada, and gray goldenrods, the spreading sweep of the elm-leaf goldenrod; the erect stand of the flat-topped goldenrod; and a host of other forms set the autumn landscape aflame with color.

Late goldenrod, like most, is a deep-rooted perennial forb. Thick, woody rootstocks are the nucleus of a tangled maze of twisting roots. Creeping rhizomes spread in every direction from solitary plants, creating dense, ever-widening clumps.

Goldenrods are found across the entire state as they are throughout most of eastern and central United States. Our state flower has a more restricted range, occurring naturally in the eastern third of the state and fingering westward along the various river systems.

Almost no soil is too dry or hard to reject them; moist lowlands encourage dense rank growths. Seek out the late goldenrod in extensive colonies along the border of damp woods and thickets. Moist, rich soil supports healthy growths. Railroad rights-of-way, roadsides, and abandoned pastures are natural sites for this native Nebraskan. Communally or singly, they adorn unmolested areas, struggling to survive and reproduce on pasture or prairie.

Hay-fever victims find the goldenrod's eruption of blossoms less than a joyous occasion. Its reputation may be well justified, but goldenrod also bears the brunt ofthe blame for many other unnamed pollen producers.

Mowing machines and 2-4-D spray have been used in attempts to eradicate it, but both have failed. Control of goldenrod, wherever it has become overabundant, can usually be resolved with the initiation of good management practices, such as the prevention of overgrazing by livestock.

Wildlife and livestock feed on goldenrods to some extent. Basal leaves are commonly eaten during early spring or late fall. Songbirds and some upland game birds feed on the seed when it ripens in fall. Dense clumps provide excellent escape and protective cover for fowl and small mammals since they remain standing during most of the harsh winter months.

History tells us that the goldenrod served as a sign for the Omaha Indians that their corn was beginning to ripen. They called the plant Zhasage-zi, or hard, yellow weed. When away from their encampments on summer buffalo hunts along the Platte or Republican rivers, the sight of goldenrod in bloom beckoned them homeward to harvest their ripening maize.

Goldenrod was once highly regarded for its medicinal uses. The American Indians employed this common herb as a cure for sore throat and for pain in general, but today it is equally recommended by herbalists as a diaphoretic for colds or coughs, and as a means of relief from rheumatism.

Leaves, dried and powdered, may be prepared to yield a salt substitute with which to season warm or cooked food. The herb is cut and powdered with a coffee mill or similar grinder and sifted through a sieve or layers of cheese cloth, thus removing the coarse stems and stubborn leaf portions.

At least one species of goldenrod was known to make a suitable tea substitute. Dr. Johann D. Schoepf in 1788 said of the brew: "Here we were introduced to still another domestic tea plant, a variety of Solidago. The leaves were gathered and dried over a slow fire. It was said that in the eastern United States, many 100-pound packages of this Bohea-tea, as they called it, had been made for as long as the Chinese tea was scarce." His praise for the mixture was not ofthe highest order, though. He continued, "Our hostess praised its good taste, but this was not conspicuous in what she brewed."

Neither threatened or threatening, goldenrod's pleasing rays of gold should continue to fire Nebraska with beauty despite repeated mowing and application of deadly sprays. Many autumns yet will be greeted by these nodding heads of gold adorning the muted browns of late summer.

THE END 52 NEBRASKAland

PRAIRIE DOCTOR

(Continued from page 14)peace. There he was set upon and mortally wounded by vengeful soldiers. The doctor administered morphine to ease the pain, then watched over him until his death. That night, the chief's old uncle slept before the door of Dr. McGillycuddy, guarding the man who had been Crazy Horse's friend. Soon the Indian Wars ended, and the military doctor, who remembered humanity even in war, was replaced by civilian doctors.

Soddies weren't much better than forts. Drafty and unsanitary, the old earthen houses made mockery of the word cleanliness. But, as Dr. Francis A. Long remarked, "Where boiled water can be obtained it is possible to do an operation with reasonable probability of successful result."